Abstract

In this paper, the authors investigate a partial inverse spectral problem for Sturm–Liouville operators with frozen arguments on star-shaped graphs. The problem is to reconstruct the potential on one edge from the known potentials on the other edges together with two sequences of eigenvalues from a prescribed spectral set. The proposed approach is constructive. First, the characteristic function associated with the given spectral data is constructed, allowing the unknown potential contribution to be isolated. The potential is then recovered by expanding the resulting expressions in an appropriate Riesz basis and solving a corresponding system of linear equations. Based on established uniqueness results, this procedure yields a constructive numerical algorithm. Numerical examples demonstrate reliable reconstruction for both smooth and piecewise continuous potentials, providing a practical scheme for frozen-argument problems on star graphs.

Keywords:

partial inverse problem; nonlocal Sturm–Liouville operator; frozen argument; Riesz basis; eigenvalues MSC:

34A55; 34K29; 34B45; 65L03

1. Introduction

Inverse spectral problems concern the recovery of differential operators from spectral data such as eigenvalues or eigenfunctions. Since the classical work of Ambarzumyan, Borg, Levinson, Gelfand, and Levitan [1,2,3,4], this area has grown into an important branch of analysis and mathematical physics.

In recent decades, this research field has remained highly active. Numerous researchers, including V.A. Yurko, V. Pivovarchik, S.A. Buterin, N.P. Bondarenko, S. Avdonin, C.F. Yang, and many others, continue to expand its boundaries and contribute to both the classical and generalized Sturm–Liouville problems, particularly with regard to uniqueness theorems, reconstruction algorithms, and stability of solutions. Over the past two decades, the theory has been extended to more general structures known as quantum (metric) graphs. A quantum graph consists of multiple edges, each treated as an interval and connected at vertices, with differential operators such as the Sturm–Liouville operator defined on the edges and appropriate coupling conditions imposed at the vertices. Quantum graphs provide a mathematical model for wave propagation on networks and have found applications in physics, chemistry, engineering, and spectral geometry (see [5] for a survey and [6,7,8,9,10,11] for further references).

Among these developments, inverse spectral problems on star-shaped graphs have received particular attention. Bondarenko [12] obtained uniqueness theorems for partial inverse problems of Sturm–Liouville operators on star-shaped graphs, where one seeks to reconstruct unknown data on a selected edge from spectral information and known data on the remaining edges; Avdonin and Kravchenko [13] proposed numerical algorithms for the self-adjoint case on a star-shaped graph; more recently, Shieh, Tsai, and Wu [14] studied nonlocal Sturm–Liouville operators with frozen arguments on star-shaped graphs and proved uniqueness theorems for the corresponding partial inverse problems. However, despite these advances, a constructive numerical reconstruction algorithm for the frozen-argument case has not been available.

The aim of this paper is to fill this gap. We develop and implement a numerical algorithm for reconstructing an unknown potential on one edge of a star-shaped graph with frozen arguments, using known potentials on the other edges together with the partial spectral data. Several numerical experiments are provided, covering both smooth and piecewise continuous potentials.

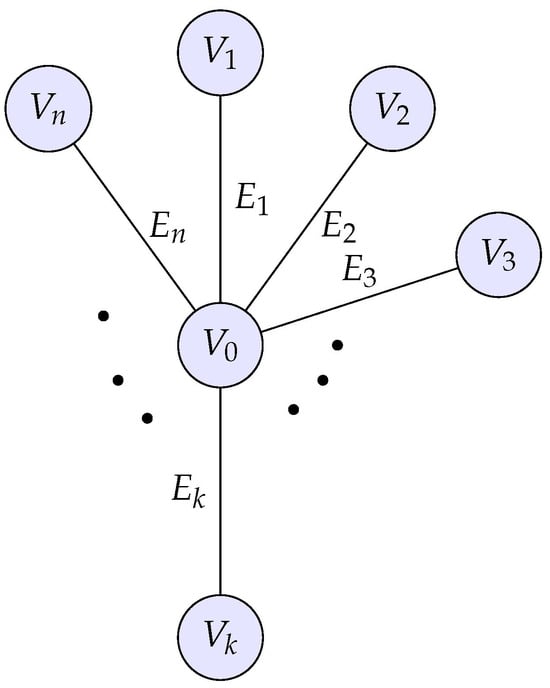

To precisely formulate the problem under consideration, let (see Figure 1) be a star-shaped graph with equal edges of length ; consists of edges and vertices where is the inner vertex and is an outer vertex which is connected to by Each edge is parameterized by the variable the vertex corresponds to the point , and the vertex corresponds to .

Figure 1.

A star-shaped graph .

In the graph, each edge is equipped with an ordinary Sturm–Liouville equation

or a nonlocal Sturm–Liouville equation

where is a real-valued -function on . Let denote the set of frozen arguments on edge Briefly, we denote We agree that if then the differential equation on is an ordinary Sturm–Liouville equation. Denote the boundary problem on which consists of the differential system

associated with boundary conditions

and Kirchhoff conditions

2. Preliminaries

In this section, we introduce the basic notation used throughout the paper along with preliminary results. We also briefly discuss a characteristic feature of nonlocal Sturm–Liouville problems, namely, the possible lack of uniqueness of solutions. As an illustration, consider the boundary value problem

For this problem admits more than one linearly independent solution, which highlights the non-uniqueness phenomenon in nonlocal settings.

As such, the analysis of inverse spectral problems relies heavily upon the construction of the characteristic function associated with the operator. In the case of star-shaped graphs, the characteristic function can be constructed from the differential operators defined on individual edges. For this purpose, we recall the following lemma.

Lemma 1

([14]). Denote as the solution of

associated with the initial condition Denote ; then, satisfies the integral equation

for . Otherwise,

where is an undetermined constant which can be chosen as either 0 or 1 depending on the specific form of and the value λ.

For consistency, we denote the characteristic function of

associated with Dirichlet boundary conditions and denote the characteristic function of

associated with Dirichlet–Neumann boundary conditions According to [15],

and

Then, the characteristic function of (3)–(5) is stated in the following theorem.

Theorem 1

(Theorem 2.4, [14]). The characteristic function of is

At the end of this section, several preliminary results that will be used in the subsequent analysis are presented. In fact, the characteristic functions allow the following integral forms (refer to [12,14]):

for and

for The functions and are derived from suitable substitutions into Equations (8) and (9), and play essential roles in reconstructing the characteristic function. Readers can refer to [12,14,16] for details.

3. Reconstruction Algorithm and Numerical Experiments

The uniqueness theorems for both ordinary and nonlocal Sturm–Liouville problems on star-shaped graphs have been established in [12,14]. Moreover, a numerical method for the ordinary Sturm–Liouville problem on star-shaped graphs was implemented in [13]. In this work, we focus on the nonlocal problem on star-shaped graphs. The characteristic function and behavior of eigenvalues shall be used to solve our inverse problem.

Theorem 2

([14]). Suppose that the problem consists of l ordinary Sturm–Liouville equations at edges and nonlocal Sturm–Liouville equations, where Then, the characteristic function of is

where Moreover, the spectral set consists of sequences where

and

Proof.

Set . Using standard asymptotic analysis (as ) on (13), we have

Applying Rouché’s theorem near integers and half-integers together with the local Taylor expansions of and yields

which are (15) and (14), respectively. □

The asymptotic forms (14) and (15) ensure that and form Riesz bases in , since they are quadratically closed to and separately.

In this section, we shall solve the following inverse problem.

(IP 1). Given , , reconstruct an approximated potential on the edge

Next, we briefly describe how one can determine the potential for the setting of the problem. Given two sequences of eigenvalues which satisfy (14) and (15), and (10) then leads to

To solve the inverse problem (IP 1), we assume the following conditions:

- (i)

- for all .

- (ii)

- has no solution in

There are two cases we want to deal with.

Case (1): Under condition (ii), determines uniquely (refer [15] for details). Equations (12) and (17) yield

Let

Then, by (14) and (15), in (17) has the following estimates:

For the two cases of Equation (18), and , multiplying them by and , respectively, we can obtain the following two estimates:

and

The last two estimates allow for subsequent approximation procedures.

We define the inner product

on Because and are real-valued functions and

is a Riesz base for (refer to [14,17]), and can be uniquely determined by Equation (18). In particular, if consists of one single point, then the potential can be reconstructed analytically according the following theorem.

Theorem 3.

; then, can be uniquely determined by and two sequences which satisfy the asymptotic behavior in (14) and (15).

Proof.

We shall write

and

According to [14] and Equation (18), and can be determined uniquely. As indicated in [14,16,18],

and

where we assume ; otherwise, the forms of and will be a little different, though the arguments following are the same. Equations (22) and (23) yield

and

Hence,

Because the functions and are fully known, we can directly determine on the intervals and . By iteratively applying the third case in (26), we can subsequently recover on , then on and so on, moving backwards. This iterative procedure ultimately reconstructs on the entire interval . This completes the proof. □

On the other hand, if contains more than one argument point, then (22) and (23) fail to hold; hence, the potential has no the simple representation. However, can be reconstructed theoretically by using (18) and the Riesz basis property of a system of vector functions (refer to [14] for details).

For approximation, we write

where

Plugging (27) into (18),

that is,

where and Then, can be solved from (29). Comparing (8) and (12), we obtain

Substituting in (30) with , we have

Equation (31) facilitates the derivation of an approximation of the sine series of i.e.,

Alternatively, an approximation of can be obtained through the following:

Hence,

For convenience, we call (34) the C-Series.

Case (2): For this case, (11) and (17) yield

According to (14),

Similar to Case (1), we can obtain . Then, we can solve

to obtain the Dirichlet–Neumann spectrum corresponding to potential On the other hand, we also solve

to obtain the Dirichlet spectrum corresponding to Then, and can uniquely determine Alternatively, the Weyl function for is

which can also help to reconstruct

Before presenting the numerical experiments, we briefly outline the algorithm for approximating and . The procedures for and are analogous, and are consequently omitted (see Algorithm 1).

| Algorithm 1 Algorithm for obtaining approximation of and |

| Step 1: Using (29), construct a coefficient matrix where |

In the following, we provide several numerical examples computed using Mathematica 14.1 with WorkingPrecision = 30. Next, we shall present some numerical experiments.

Example 1.

Let and We pick the following two sequences of approximated (computed) square root of eigenvalues from the spectral set of the nonlocal problem on a three-edged graph. Note that the computed eigenvalues are inexact due to the use of numerical solvers; therefore, we treat them as noisy measurements.

Case 1: Assuming , and are known a priori, for this case, we obtain the recovered potentials

or

The list of coefficients is presented below (Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1.

Approximated square roots of eigenvalues.

Table 2.

Coefficients of the approximated potential.

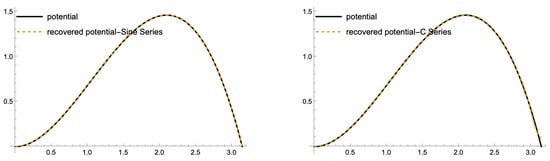

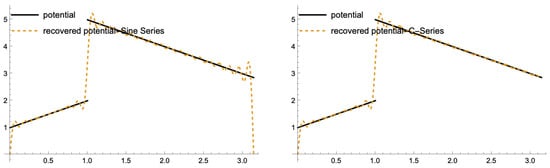

The comparison between the exact potential and the recovered potential is illustrated in Figure 2. It is evident that is smooth and vanishes at both endpoints. The approximation closely matches the exact potential, which can be attributed to the appropriateness of the chosen bases in (32) and (34).

Figure 2.

Approximated potential for .

Case 2: Assuming , , and are known a priori, for this case we obtain the recovered potentials

or

The list of coefficients is presented below (Table 3).

Table 3.

Coefficients of the approximated potential.

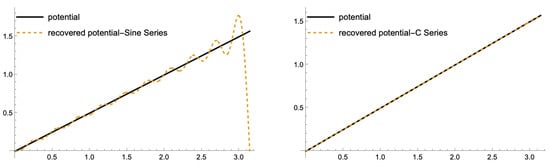

The comparison between the exact potential and the recovered potential is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Approximated potential for .

Notice that the sine series approximation is not as good as that of the C-Series for this case. The sine series approximation tends to be inaccurate near the endpoints, a phenomenon often attributed to the Gibbs effect.

Case 3: Assume that and are known a priori and that In this case, the Sturm–Liouville operator on edge reduces to an ordinary form. To recover both the Dirichlet eigenvalues and Dirichlet–Neumann eigenvalues are required. To this end, we must first compute the functions and which are then used to determine the Dirichlet and Dirichlet–Neumann spectral data. For this case, we take

We immediately obtain the coefficients by applying the linear system in (35) for Hence,

which leads to the conclusion that

Finally, we shall present a case in which the potential is not continuous at some point inside

Example 2.

In this example, we take , and

is a piecewise continuous function. Again, the picked computed eigenvalues are as below (Table 4).

Table 4.

Approximated square roots of eigenvalues for piecewise function .

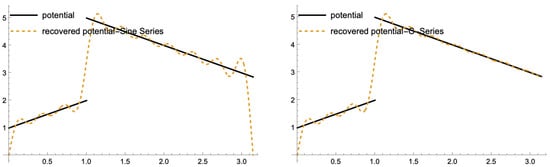

Using forty computed eigenvalues to recover the potential yields the approximation shown in Figure 4, which is clearly unsatisfactory. To enhance the reconstruction accuracy, we can increase the number of eigenvalues to The resulting approximation displayed in Figure 5 shows an improvement.

Figure 4.

Approximated potential for with 40 eigenvalues.

Figure 5.

Approximated potential for with 100 eigenvalues.

The reader might wonder whether our theory and algorithm can be extended to the case of star graphs with unequal edge lengths. The answer is affirmative. Although we omit the technical details here, interested readers are encouraged to explore this extension independently.

4. Conclusions

In this paper, we have studied the partial inverse spectral problem for nonlocal Sturm–Liouville operators with frozen arguments on a star-shaped graph. We have presented a constructive solution by recovering one unknown coefficient on a selected edge using a partial set of spectral data. We have formulated an algorithm for numerical reconstruction and validated its effectiveness through various examples, including both smooth and piecewise continuous potentials. Our experiments demonstrate that the proposed method provides accurate reconstructions with sufficiently many eigenvalues. The performance of sine-type and cosine-type series reconstructions has also been compared. Although the present study is primarily theoretical, the proposed method provides qualitative insight into the influence of graph and frozen arguments on system behavior.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.-T.S., T.-M.T. and J.-S.W.; Methodology, C.-T.S. and T.-M.T.; Validation, J.-S.W.; Formal analysis, C.-T.S. and T.-M.T.; Investigation, C.-T.S., T.-M.T. and J.-S.W.; Data curation, J.-S.W.; Writing—original draft, C.-T.S.; Writing—review & editing, T.-M.T.; Visualization, C.-T.S. and J.-S.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Authors Shieh and Tsai are partially supported by the National Science and Technology Council of Taiwan under grants 114-2115-M-032-002 and 114-2115-M-131-001, respectively.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ambarzumyan, V. Über eine Frage der Eigenwerttheorie. Z. Phys. 1929, 53, 690–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, G. Eine Umkehrung der Sturm–Liouvilleschen Eigenwertaufgabe. Acta Math. 1946, 78, 1–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, N. The inverse Sturm–Liouville problem. Math. Scand. 1949, 1, 29–45. [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand, I.M.; Levitan, B.M. On the determination of a differential equation from its spectral function. Izv. Akad. Nauk. Nauk SSSR, Ser. Mat. 1951, 15, 309–360. [Google Scholar]

- Kuchment, P. Quantum graphs: I. Some basic structures. Waves Random Media 2004, 14, S107–S128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belishev, M.I.; Vakulenko, A.L. Inverse problems on graphs: Recovering the tree of strings by the BC-method. J. Inverse-Ill-Posed Probl. 1995, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutkin, B.; Smilansky, U. Can one hear the shape of a graph? J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 2001, 34, 6061–6068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurko, V. Inverse spectral problems for Sturm–Liouville operators on graphs. Inverse Probl. 2005, 21, 1075–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-F. Inverse spectral problems for the Sturm–Liouville operator on a d-star graph. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2010, 365, 742–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avdonin, S.; Kurasov, P.; Levitin, M. Inverse problems for quantum trees. Inverse Probl. 2012, 28, 025003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondarenko, N.P.; Shieh, C.-T. Partial inverse problems for Sturm–Liouville operators on trees. Proc. R. Soc. Edinb. Sect. A Math. 2017, 147, 917–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondarenko, N.P. A partial inverse problem for the Sturm–Liouville operator on a star-shaped graph. Anal. Math. Phys. 2018, 8, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avdonin, S.A.; Kravchenko, V.V. Method for solving inverse spectral problems on quantum star graphs. J. Inverse-Ill-Posed Probl. 2023, 31, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shieh, C.-T.; Tsai, T.-M.; Wu, M.-N. Partial inverse spectral problems for Sturm–Liouville operators with frozen arguments on a star-shaped graph. Results Math. 2025, 80, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shieh, C.-T.; Tsai, T.-M. Inverse spectral problems for Sturm–Liouville operators with many frozen arguments. Appl. Math. Comput. 2025, 492, 129235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buterin, S.; Kuznetsova, M. On the inverse problem for Sturm–Liouville type operators with frozen argument: Rational case. Comput. Appl. Math. 2020, 39, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pöschel, J.; Trubowitz, E. Inverse Spectral Theory; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bondarenko, N.P.; Buterin, S.A.; Vasiliev, S.V. An inverse spectral problem for Sturm–Liouville operators with frozen argument. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2019, 472, 1028–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.