Abstract

Hierarchical Bayesian models based on Gaussian processes are considered useful for describing complex nonlinear statistical dependencies among variables in real-world data. However, effective Monte Carlo algorithms for inference with these models have not yet been established, except for several simple cases. In this study, we show that, compared with the slow inference achieved with existing program libraries, the performance of Riemannian manifold Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (RMHMC) can be drastically improved by applying the chain rule for the differentiation of the Hamiltonian in the optimal order determined by the model structure, and by dynamically programming the eigendecomposition of the Riemannian metric with the recursive update of the eigenvectors at the previous move. This improvement cannot be achieved when using a naive automatic differentiator included in commonly used libraries. We numerically demonstrate that RMHMC effectively samples from the posterior, allowing the calculation of model evidence, in a Bayesian logistic regression on simulated data and in the estimation of propensity functions for the American national medical expenditure data using several Bayesian multiple-kernel models. These results lay a foundation for implementing effective Monte Carlo algorithms for analysing real-world data with Gaussian processes, and highlight the need to develop a customisable library set that allows users to incorporate dynamically programmed objects and to finely optimise the mode of automatic differentiation depending on the model structure.

Keywords:

hierarchical Gaussian process model; Riemannian manifold Hamiltonian Monte Carlo; Bayesian statistics; automatic differentiation; high-performance computing MSC:

65C05

1. Introduction

In machine learning, Bayesian analysis based on Gaussian processes (GPs) associated with positive semidefinite kernels has been studied extensively from modelling, algorithmic, and theoretical points of view [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. A GP serves as a prior process for generating nonlinear functions that describe relationships between variables. The goal of Bayesian analysis with GPs is to infer the posterior process for such nonlinear functions conditioned on given data or to estimate the average of quantities of interest over such a posterior process. Although the posterior process can be represented as a closed-form solution for the simplest problems (e.g., Chapter 6 of Ref. [13]), such a solution cannot be expected when GPs are used as building blocks for hierarchical models that capture complex statistical dependencies among variables in real-world data (e.g., GPLVM, GPDM, iWMM, and DGP [1,2,7,8]). Algorithms for inference with hierarchical GP models can be broadly divided into variational algorithms and Monte Carlo (MC) algorithms. Variational algorithms (e.g., Refs. [9,11]) are usually much faster than MC algorithms but introduce unavoidable bias due to discrepancies between the original and variational models. In contrast, MC algorithms (e.g., Refs. [10,14,15]) allow for precise computation of averages over the posterior, provided the algorithm is run until convergence, namely, asymptotically exact computation. The preferred algorithm type depends on the purpose of the computation. At the moment, however, all algorithms included in the commonly used program libraries designed for the inference with GP-based hierarchical Bayesian models (GPyTorch and GPFlow [16,17]) are variational or a hybrid of variational and MC approaches.

Apart from the developments in machine learning, closely related frameworks for modelling with GPs have been proposed in the other branches of statistics as well. With the early recognition of the correspondences between smoothing by splines and Bayesian estimation with Gaussian processes [18], researchers have proposed estimation methods for the latter framework. Since a stricter guarantee on the quality of estimation results tends to be required outside the machine learning community, MC algorithms are preferred to variational algorithms. For example, in biometric and econometric applications, biased results can be misleading and may adversely affect public health or the economy; therefore, the use of variational algorithms is not appropriate. Therefore, MC algorithms or a deterministic method termed “iterative nested Laplace approximation (INLA)” [19] are used for the estimation. Different types of Markov-chain MC (MCMC) algorithms, INLAs, and softwares for their easy implementation are available (for MCMC, different derivatives of BUGS [20] and Stan [21]; for INLA, R-INLA [22]). Depending on the model class, INLA has been shown to perform inference very fast (see Ref. [23] for the comparison between INLA and MCMC).

However, it is important to note that these GPs used in statistics are different from those employed in machine learning. A strong condition is imposed on these GPs in order to keep the correlation of the prior Gaussian process short-range [24]. The combination of such short-range GPs and independent observations results in a short-range posterior which is much easier to sample from with the currently available MC algorithms than the posteriors of the GPs in machine learning that are strongly correlated over data points. INLA also exploits this short-range correlation. INLA assumes that the posterior conditioned on a small number of hyperparameters is approximated well with a Gaussian distribution (i.e., the Laplace approximation), which is justified by the central limit theorem. INLA takes advantage of the sparseness of the precision matrix of this approximating Gaussian distribution due to the short-range correlation. These assumptions made in the statistical analysis with MCMC and INLA reveal their limitations. First, as we discuss further below, the posterior of the hierarchical GP models with long-range correlation can be neither efficiently sampled with commonly used MCMC nor efficiently approximated with the integral of Gaussian conditional distributions. Second, with regard to INLA, the Laplace approximation is not valid if the conditional posterior is singular or nearly singular. Singular models are known to be ubiquitous, ranging from simple Gaussian models where both the mean and variance are parameterised, to large complex hierarchical models [25]. Although INLA was extended to near-Gaussian cases [26], the use of INLA is not appropriate for the analysis of such potentially singular hierarchical Bayesian models and is severely limited to simple models such as the latent Gaussian model discussed in Ref. [24].

As we have discussed above, the literature on the application of MC algorithms to hierarchical GP-based models is limited in both machine learning and statistics. In this study, we seek an efficient MC algorithm for hierarchical GP models used in machine learning, in order to enhance the applicability of the models in the other statistical fields, especially in biometrics and econometrics. To our knowledge, a standard MC algorithm for this purpose has not yet been established. Svensson et al. [10] sampled a function from the posterior process using a closed-form solution for the GP component of their model conditioned on other parameters. Their formula can be applied only when the likelihood term is Gaussian and is thus not applicable to, for example, binary classification. Hensman et al. [27] introduced a non-Gaussian variational approximation of the posterior with the aid of inducing points sampled using Hamiltonian MC (HMC). Their method, however, is variational and not guaranteed to describe the posterior precisely, and its scalability with increasing numbers or dimensions of GPs remains unclear. Pandita et al. [15] introduced an adaptive sequential MC for GPs to solve problems in mechanical engineering. However, the authors used hundreds of CPU cores for inference, and the efficiency of their sampling scheme itself was not clearly demonstrated.

One fundamental issue in MC sampling from the posterior in a GP-based model is that the posterior is highly stretched or compressed along unknown directions in the parameter space used for sampling, namely, an unknown complex long-range correlation. To address this problem, Paquet and Fraccaro [14] implemented Riemannian manifold HMC (RMHMC) for GP models. With the Hessian metric they employed, RMHMC adjusts the direction of MC moves according to the curvature of the log posterior density surface. They demonstrated that RMHMC is much more efficient than the ordinary HMC method based on the Euclidean metric. However, their method is applicable only to cases with log-concave posterior densities, whereas hierarchical models that describe complex dependencies among variables typically have non-log-concave posterior densities.

To overcome this limitation, in this study, we aim to obtain an efficient implementation of RMHMC for hierarchical GP models using a soft-absolute Hessian metric introduced by Betancourt [28]. This metric transforms an indefinite Hessian into a positive semidefinite matrix that shares eigenvectors with the Hessian but has associated eigenvalues set close to the absolute values of the original Hessian eigenvalues. Although a general-purpose implementation of this algorithm [29] based on PyTorch [30] is available, its performance is too poor to be used for sampling from the posterior of hierarchical Bayesian models with multiple GPs. We study the cause of this poor performance and identify two sources of redundancy. First, we find that the computation order of the differentiation of the Hamiltonian according to the chain rule crucially affects the performance. This implies that the performance of an implementation of the algorithm cannot be optimised as long as it relies on the automatic differentiator provided by high-level programming languages designed for performing machine learning with graphical processing units (GPUs), such as PyTorch and TensorFlow [30,31]. This limitation is serious when we take into account the current standard practice for developers of libraries and their users to apply these automatic differentiators to manually coded functions, in order to avoid manually coding the (higher-order) derivatives, a major source of program bugs. Second, we find that redundancy can be removed by dynamically programming eigendecomposition required at each step of RMHMC. Dynamic eigendecomposition has recently been shown to improve performance in matrix optimisation [32], and we find RMHMC with the modified Hessian metric to be as suitable for its application as this case. With these findings, we implemented the RMHMC based on the soft-absolute Hessian metric by coding programs with low-level languages, C++ and OpenACC [33,34], and we confirmed that this implementation performs the algorithm more than ten times faster than the existing library based on the high-level languages [29].

The article is organised as follows. In Section 2.1, we provide preliminaries. In the Section 2.1.1, we introduce our problem setting in which multiple GPs are used as building blocks for a hierarchical Bayesian model, employing the representation of GPs introduced by Solin et al. [35]. In Section 2.1.2, we provide a brief introduction to RMHMC with a soft-absolute Hessian metric. In Section 2.2, we identify two sources of redundancy described above. We show how performance deteriorates when reverse-mode automatic differentiation and a divide-and-conquer algorithm for the eigendecomposition of symmetric matrices in PyTorch are naively applied. In Section 3, we numerically demonstrate that our implementation considerably outperforms an implementation based on a general-purpose library. The details of the experimental methods are provided in Section 2.3. Specifically, in Section 3.1, we compare the performance of different implementations using toy examples of varying sizes and show that both sources of redundancy contribute to the improvement. In Section 3.2, we compare the performance of our implementation with that of no-U-turn (NUT)-HMC based on the Euclidean metric. We show that NUT-HMC becomes trapped within a very narrow region and fails to converge to the posterior, suggesting that the use of a data-adaptive metric is essential for efficient sampling. In Section 3.3, we show, using a toy example and a real-world dataset, that our implementation successfully calculates the marginal likelihood, (that is, the Bayesian model evidence) within a reasonable computation time. Although INLA performs this calculation faster on the toy examples, it is too slow to analyse real-world data using nonlinear GP models with non-log-concave posteriors. Finally, in Section 4, we discuss, based on these results, the advantages and limitations of the proposed method compared with existing approaches and suggest directions for future work. The mathematical notations used in this article are summarised in Table A1.

2. Methods and Algorithms

2.1. Preliminaries

2.1.1. Hierarchical GP Models and Their Approximate Representations

As we have stated in the Introduction, we aim to obtain an implementation of RMHMC that is applicable to hierarchical GP models with non-log-concave (conditional) posteriors. Although numerous such models have been proposed, the following simplest class of models that slightly extend basic GP models with log-concave (conditional) posteriors [6,36] would be most suitable for testing the performance of samplers.

Let us consider hierarchical GP models for which the samplewise likelihood of i.i.d. data (with sample index ) is parameterised by J nonlinear functions generated from GPs through function U as

For instance, the simplest examples describing the relationship between a target variable and covariates are as follows.

Example 1.

Covariate-dependent target mean and variance ():

with fixed .

Example 2.

Nonlinear Gaussian mixture model ():

In the above modelling, we assume that each of is the sum of nonlinear functions generated by GP priors :

Each GP is associated with a positive semidefinite kernel that describes the prior covariance of the generated functions and is parameterised by scalar hyperparameters . Thus, each of is a Bayesian multiple-kernel model, the statistical properties of which were investigated in a previous study [6]. The prior density of the hyperparameters is assumed to be given.

As we jointly sample functions and hyperparameters , the complicated dependence of the prior density of on hinders efficient sampling. To alleviate this problem, one previous study [35] introduced a useful approximation scheme that took the following form:

where the generated function was represented as the sum of sinusoidal feature functions weighted by the normally distributed coefficients . For the Gaussian kernels that we mainly use in this study, hyperparameters tune the amplitude and bandwidth, respectively, of the GP through the above equation. Concrete representations of and are given in Appendix A. In this study, for simplicity, we restrict ourselves to the use of one-dimensional Gaussian kernels and linear kernels, as well as the use of a single set of hyperparameters for all the GPs associated with Gaussian kernels, and a single hyperparameter for all the GPs associated with linear kernels (equivalently Gaussian random variables). Note that can be set to one for linear kernels. We assign inverse Gamma priors to the hyperparameters as follows:

In the limit (see Appendix A for the definition of L), the above approximation tends to be exact (Theorem 4 of Ref. [35]). The advantage of this approximation is the use of features () that are independent of the bandwidth parameter , and the use of a tractably computed prior density for . However, the prefixed sinusoidal features are less flexible than are data-adaptive features (obtained, e.g., by the incomplete Cholesky decomposition [37]) and are not suitable for approximating high-dimensional functions. In biometric and econometric applications (e.g., epidaemiology), modelling a target variable as the sum of the effects of several factors is preferred for the sake of interpretability and robustness. Thus, modelling with the sum of several low-dimensional functions in Equation (4) is justifiable.

The above modelling motivates our investigation of efficient MC algorithms. The variance varies with over a few orders of magnitude. Combined with the structure of the data likelihood, the posterior distribution is often extremely stretched or compressed along unknown directions. Thus, a data-adaptive sampling scheme, such as RMHMC, is required.

2.1.2. RMHMC with a Soft-Absolute Hessian Metric

An HMC algorithm [38,39,40] obtains samples of parameters from a target density by regarding q as the position of particles and simulating its time evolution together with that of the associated momentum vector according to the Hamilton equation of motion with a suitably designed Hamiltonian . The time evolution over discretised timesteps is determined as follows:

This time evolution for a time period of duration is called a leapfrog. The mapping from to preserves the volume and approximately preserves the value of . As we show in Algorithm 1, HMC repeats the combination of C leapfrogs and the sampling of a new value for p from a suitable q-dependent Gaussian distribution. At the end of every C leapfrogs, the change in due to discretisation is adjusted via the Metropolis–Hastings procedure. Samples obtained from a long-time simulation after a burn-in period approximate the target distribution, and the statistics calculated with the samples converge to the average over the target at the infinite time limit. Girolami and Calderhead [41] introduced the use of a nontrivial Riemannian metric for the parameter space and showed that, in this case, the Hamiltonian should be defined as follows:

For this version of Hamiltonian, their derivatives with respect to q and p read as

The choice of recovers the ordinary HMC based on the Euclidean metric.

| Algorithm 1 (RM)HMC |

|

The Hessian of is a natural choice for , as we explained in the previous section. However, the Hessian of the negative log posterior density for a hierarchical probabilistic model is often not positive definite and therefore cannot be used as a metric. For this problem, Betancourt [28] proposed transforming the Hessian into a positive definite matrix as follows:

where the differentiable function g approximates the absolute value, i.e., . In the above, and are the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the Hessian H. Employing this transformed metric is equivalent to rescaling the motion of particles according to the absolute value of the curvature of the log density graph. Betancourt [28] further showed how to compute the right-hand sides of Equation (9) for the soft-absolute Hessian, as follows, for :

where ⊙ denotes the Hadamard product. Given that eigenvectors and eigenvalues were already obtained, Betancourt [28] showed that the formula in Equation (11) allows one to compute the right-hand side of the second equivalence in Equation (9) for with an computational cost by first caching

for and , and then calculating

Here, and are obtained by matrix multiplications, the full gradient is obtained by an computation, and the trace operations are carried out by taking the sum of the elementwise products times; hence, the overall complexity of the computation is .

2.2. Two Sources of Redundancy in the Previous Implementations

2.2.1. Order of Computations in the Calculation of Gradient Flow

As we show below, a straightforward application of the above algorithm to the model described by Equations (1), (4)–(6) is time consuming. We show that the computational cost can be reduced to for , , and fixed J. Here, the exponent describes the computational complexity of multiplying matrices of sizes and (equivalently matrices of sizes and ) (see Table 2 and Footnote 1 of Ref. [42]). This can be verified by substituting a concrete representation of the third derivatives of the negative log posterior density for in Equation (13) as follows: for , , , , , , and .

where we omit writing down the terms that involve the derivatives with respect to the bias term and the hyperparameters whose contribution can be computed in the same manner as those of the derivatives with respect to . For each combination of , the suitably ordered computation in the second line requires , , , , and computations for calculating , calculating the Hadamard product, calculating the matrix vector product with vector (a vector all of whose entries are 1), multiplying the diagonal matrix from the left, and calculating the matrix vector product with , respectively.

The important point that should be noted here is that the standard library based on the automatic differentiation of the Hamiltonian does not follow the above order of computations. First, the direct derivatives of the Hamiltonian cannot be automatically computed when the soft-absolute metric is used. If the formula in Equation (9) is naively implemented by computing the third-order derivatives of the log likelihood with the aid of an automatic differentiator in the reverse mode (the default mode in PyTorch 2.8.0), at least an computation is required. This differs greatly from the efficient computation described above. Even if the joint likelihood is log concave and the formula in Equation (9) can be avoided, a naive application of a reverse-mode automatic differentiator to the Hamiltonian results in the same computational cost. In order to obtain an efficient implementation using an automatic differentiator, one must first implement a differentiator that recognises the formula in Equation (9) and then suitably assign the forward or reverse mode to the differentiations of the components of the Hamiltonian according to the chain rule in a model-structure-dependent manner.

2.2.2. Dynamically Programmed Eigendecomposition

The formula given by Betancourt [28] relies on the availability of the complete set of eigenvectors . The fact that and are close to each other motivates us to reduce computational costs by dynamically computing to take advantage of . The boundedness of the gradient of and p in the region where the joint probability for is concentrated implies that

holds with a high probability in terms of the Frobenius norm and can be efficiently eigendecomposed as

using the Jacobi method. Note that cyclic versions of the Jacobi method quadratically converge [43] and are suitable for parallelisation [44], and thus are expected to carry out the above decomposition very quickly with a small error tolerance . With this decomposition, we update the eigenvectors as

In practice, we perform the Gram–Schmidt orthogonalisation of every ten steps before applying it to to remove accumulated numerical errors.

2.3. Methods of Numerical Experiments

2.3.1. Examination of Computational Complexity

We investigate the efficiency of the proposed algorithm by performing Bayesian logistic regression with artificially generated data and measuring its computation time. For comparison, we also perform posterior sampling using Hamiltorch [29], a publicly available library for different types of HMCs based on PyTorch that works on CUDA devices.

First, we generate standardised explanatory variables for each sample i (). Then, we calculate the true log odds ratio according to

with , for and otherwise. For any k, the feature function is given by Equation (A2) in Appendix A with and . Here, the value of constant is determined so that the empirical standard deviation is 1.5.

We then generate the sample label according to

For this dataset, we perform posterior sampling, where the model is determined by Equation (1) with and

where function is further decomposed into functions associated with one-dimensional Gaussian kernels:

Here, we abuse a notation for brevity by identifying index k with a Gaussian kernel function , for which, again, the feature function is given by Equation (A2) in Appendix A with , and . The associated GPs and their hyperparameters are described by Equations (4)–(6). For the transformation into the soft-absolute Hessian in the proposed method, we used , which takes values close to employed in Hamiltorch. We did not implement the latter because of the singularity of at zero and the lack of a straightforward implementation in the library that we used (NVIDIA Inc. (Santa Clara, CA, USA), NVHPC23.1 [34]).

In addition to the values specified above, we used the following values: (for the comparison of sampling speed) , , , , , , , ; (for the calculation of BME (see Appendix B)) , , , , , , , , (), (), (), and (). The initial parameter values for MC we used were , and for any hyperparameter .

We confirm the convergence of the proposed algorithm by performing Wilcoxon’s rank sum test for the values of the log posterior density in the first and second halves of the trajectory after an initial burn-in period. The proposed method was implemented by writing codes in C++ and OpenACC that offload most of the calculation to a CUDA device retaining all necessary data in its own memory, and by invoking cuBLAS and cuSolver for linear algebra routines as much as possible. For comparison, we wrote a code in PyTorch for the same model that invokes Hamiltorch for carrying out RMHMC or NUT-HMC with a manually coded likelihood. To conduct a comparison of different implementations, we measure the wall time spent on MC moves run on a single CPU core (a recent version of Intel Xeon processor) connected to a single NVIDIA Tesla A100 PCIe 80 GB GPU card, for each of the five datasets generated with different seeds for the random number generator.

All of the source codes used for the analysis described above are provided as Supplementary Materials.

2.3.2. Analysis of 1987 National Medical Expenditure Survey (NMES)

To demonstrate that our implementation is acceptably efficient in a real-world application, we perform Bayesian estimation with excerpted data from the 1987 national medical expenditure survey (NMES) of the United States. A few groups of authors performed causal inference with this dataset about the effects of smoking on medical expenditures [45,46,47]. In the present analysis, we attempt to increase the precision of the propensity function used for causal inference. As shown by Imai and van Dyk [46], the identification of a set of parameters f that characterise the conditional distribution of the actual treatment variable for the given values of covariates reduces the dimensionality of subsequent causal analysis.

In this dataset, denotes the packyear of smoking (i.e., the product of the number of packs of cigarette consumed by the subject and the duration of smoking measured in years). The covariates include the age at the time of the survey, the age at the initiation of smoking, gender, race, marital status, education level, census region, poverty status, and seat belt usage. The previous study focused mainly on the estimation of the mean of the conditional distribution as f and not its variance. We compare the performance of linear and nonlinear models that describe only the conditional mean, and the performance of linear and nonlinear models that describe both the conditional mean and variance (Equation (2)). In particular, as the model that best describes the given data is determined by the value of the Bayesian model evidence (BME) [13], we investigate whether the proposed method (and INLA) computes this value within a reasonable computation time (see Appendix B and Appendix C for the technical details of the calculation of BME). Carrying out causal inference with the estimated propensity functions requires further theoretical development and is not within the scope of the present study. Thus, we restrict our analysis to the estimation of propensity functions and discuss the further development that is needed in Section 4.

We obtained the dataset included in a library for causal inference [47]. The categorical covariates in this dataset were transformed to a set of binary covariates that retained the original information. The continuous covariates were standardised to have a zero mean and unit variance.

For this dataset, we considered the data likelihood described by Equation (2). The function () was described as

For the linear models, we used a linear kernel indexed by k for each variable , and thus we had with . For the nonlinear models, we used a one-dimensional Gaussian kernel for each continuous variable with and , and a linear kernel for each binary variable. The models that describe the conditional mean and variance were determined in this manner. The models that describe only the conditional mean determined in the manner described above, whereas their variance was described by . The priors for GPs and hyperparameters were described by Equations (4)–(6) in the same manner as for the simulated data.

In addition to the values specified above, we used the following values: , , , , ( for the nonlinear model describing both of the conditional mean and variance), , , , , (), (), (), and (). The initial parameter values for MC we used were , , and for any hyperparameter .

All of the source codes used for the analysis described above are provided as Supplementary Materials.

3. Results

3.1. Comparison Among Different Implementations of RMHMC with a Soft-Absolute Hessian Metric

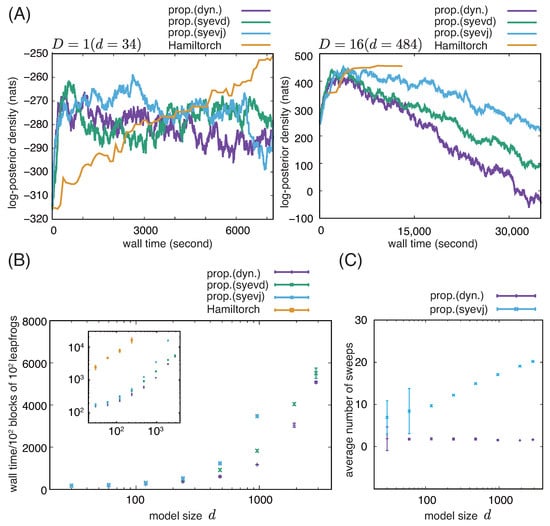

The proposed implementation is fast enough to converge to equilibrium in both small and moderately large models, as seen from the trajectories in Figure 1A and confirmed by a Wilcoxon rank sum test for ~14,000- and ~60,000-s simulations (), respectively. As shown in Figure 1A,B, our implementation is roughly ten times faster than the RMHMC based on Hamiltorch.

Figure 1.

RMHMC for Bayesian logistic regression on simulated data. Comparison between our implementations based on the dynamic and static eigendecomposition of the Hessian and the implementation based on Hamiltorch. (A) Representative trajectories of log posterior density for () and (). (B) Mean and standard deviation of the wall time spent on computing 100 blocks of 100 leapfrogs are shown on the linear (main panel) and logarithmic (inset) scales for different model sizes. (C) Mean and standard deviation of the number of sweeps in the cyclic Jacobi method for a single dynamic and static eigendecomposition of the metric are shown on the logarithmic scale for different model sizes. In (B,C), model sizes are shown on the logarithmic scales. (Abbreviations) prop.(dyn.): the proposed method based on dynamic eigendecomposition, prop.(syevd): the proposed method based on static eigendecomposition with the divide-and-conquer algorithm, and prop.(syevj): the proposed method based on static eigendecomposition with the Jacobi method.

To investigate the relative impact of the order of computations compared with that of the dynamically programmed eigendecomposition, we also measured the wall time for implementations in which the eigendecomposition was replaced by static ones based on either the Jacobi method or the divide-and-conquer algorithm. The inset in Figure 1B suggests that the difference in computation time between our implementation and the implementation based on Hamiltorch is mainly attributed to the computation of the gradient flow rather than eigendecomposition.

However, a close examination of Figure 1B also shows differences among the algorithms for eigendecomposition. Although little difference is observed in computation time among the examined algorithms for small D, the dynamic eigendecomposition saves substantial computation time for large D. However, we also observe that the faster increase in the computational cost of the Jacobi method compared to that of the divide-and-conquer algorithm reduces this saving for () and (). Examining the number of sweeps in the cyclic Jacobi method in static and dynamic implementations (Figure 1C), we confirm the advantage of the dynamic implementation, which requires only one to two sweeps at each step regardless of the model dimensionality, whereas the static implementation requires an increasing number of sweeps for greater model dimensionality on average. In the current model setting, the performance with () could not be examined because of numerical instability.

3.2. Comparison with NUT-HMC Sampler

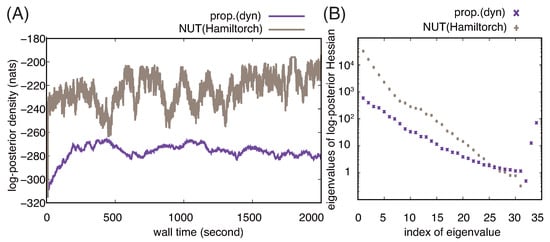

We also confirm the advantage of using RMHMC by comparing its performance with that of NUT-HMC. As shown in Figure 2A, NUT-HMC reaches samples of parameter values that have large values of log posterior density very quickly and continues generating similar samples (Figure 2A). This contrasts with the slow convergence of RMHMC to generate samples with lower log posterior density. To obtain a clue as to which samplers generate representative samples from the posterior, we examine the eigenvalues of the Hessian of the log posterior density with representative samples from the two samplers (Figure 2B). We see that the eigenvalues for the sample from NUT-HMC are ten times larger than those for the sample from RMHMC, except for several small positive or negative eigenvalues. This suggests that the samples from NUT-HMC have been taken from a much narrower region having a larger density. We therefore doubt that the total posterior probability for this narrow region is smaller than that for the region explored by RMHMC. We will see that this is the case below.

Figure 2.

Comparison of proposed implementation of RMHMC and NUT-HMC in Hamiltorch. (A) Representative trajectories of the log posterior density for () obtained using the proposed implementation of RMHMC based on dynamic eigendecomposition (prop.(dyn)) and NUT-HMC in Hamiltorch. (B) Eigenvalues of the Hessians of the negative log posterior density for the samples of parameter values obtained after running the proposed implementation of RMHMC and NUT-HMC in Hamiltorch for 2000 s. The eigenvalues are plotted in descending order on the logarithmic scale. For negative eigenvalues, their absolute values are plotted. The absolute values of the 32nd to 34th eigenvalues for the sample from NUT-HMC were extremely small and are therefore out of the range in the plot.

3.3. Calculation of BME Beyond the Laplace Approximation with Simulated Data and NMES Data

The existence of negative eigenvalues in Figure 2B suggests that the posterior cannot be regarded as being approximately normal. This is not surprising, since hierarchical models are known to be often singular [25]. Thus, the BME of the proposed model cannot be calculated by simply applying the Laplace approximation to the posterior density. Even in this case, we successfully carried out the calculation of BME through MC integration with reasonably high precision, as confirmed by the standard error of the estimate determined with multiple sequences of RMHMC (Table 1). The obtained value was in good agreement with the BME value obtained by performing INLA, namely, numerically integrating the Laplace approximation of the likelihood conditioned on each combination of hyperparameter values (see Appendix B for technical details). As expected from the nature of the two computation methods, INLA carried out the calculation within a shorter time. The latter calculation based on the Laplace approximation is justified by the fact that the model has log-concave posterior density and is regular when conditioned on hyperparameters.

Table 1.

Calculation of BME using the proposed implementation of RMHMC and INLA. The mean (and standard error) of the estimated model evidence and the mean (and standard deviation) of the wall time for its computation in a single RMHMC (among Z RMHMCs) or in INLA are shown. For NMES data, linear (L) and nonlinear (NL) models that describe only the conditional mean (mean) or both of the conditional mean and variance (mean/var) were used.

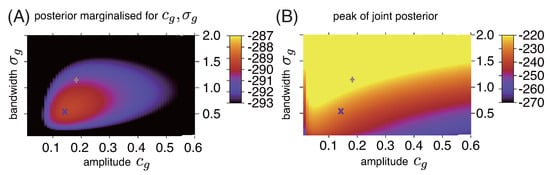

In the calculation with INLA, it is also confirmed that the samples obtained with RMHMC and NUT-HMC in Figure 2 are positioned near the center and periphery of the posterior probability mass, respectively (Figure 3A), while they are positioned near the lower/broader and higher/narrower peaks of the posterior density, respectively (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Colour plot of (A) marginal posterior density and (B) peak value of joint posterior ( used in RMHMC) for different values of amplitude and bandwidth . Representative samples obtained after ~2000-s simulations with RMHMC and NUT-HMC are also plotted with the same symbols as those used in Figure 2.

To demonstrate the usefulness of the proposed method for analysing real-world data, we also calculate the BME for the NMES dataset using linear or nonlinear models that estimate the mean (and variance) of the distribution of the treatment variable conditioned on the covariates, namely, the propensity functions. We successfully calculated the BME values for this estimation problem within an acceptable computation time (Table 1). The computed BME values showed improved estimation of the propensity function with the nonlinear model for both the mean and variance of the conditional treatment density.

The computation of BME with these models was also carried out using INLA. The repeated alternate application of the l-BFGS algorithm to the non-log-concave likelihood term of the model required more computation time than was required for INLA on simulated data. For the linear model of the conditional mean or the conditional mean and variance, INLA requires the integration with respect to only one hyperparameter, which was carried out within a very short time. For the nonlinear models, however, INLA requires the integration with respect to three hyperparameters and hence the evaluation of approximate Gaussian conditional distributions on much more points in the hyperparameter space. Furthermore, in these models, the evaluation of each combination of hyperparameter values took several tens of seconds. As a result, INLA took far more time to compute the BME values for nonlinear models than RMHMC.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we have investigated MC methods for the posterior sampling of functions and hyperparameters in hierarchical GP models, and we have shown that a straightforward implementation of RMHMC based on currently available general-purpose libraries is highly redundant and its performance can be greatly improved. The main source of redundancy was the order of computation in the calculation of the gradient flow on the Riemannian manifold, whereas the eigendecomposition of the metrics was also a major source of redundancy for larger models. These findings have non-trivial implications for future modelling based on GP and its implementations, because our results indicate that in the current standard practice of coding only the likelihood of the model and allowing libraries to carry out inference with the aid of automatic differentiation results in poor performance, unless an intelligent library that optimises overall computational complexity is developed.

This problem was not recognised in the previous study of RMHMC for GP [14], because they sampled in the space for dual variables ( with in our notation) for which the entries of the third-order derivative tensor were sparse. In a hierarchical model with multiple GPs, the use of dual variables incurs a large computational cost. In this case, sampling in the space for multiple sets of dual variables () is very high-dimensional. In this case, the eigendecomposition of the metric required for the Betancourt’s formula (Equation (9)) is essentially impossible to compute. Furthermore, the derivatives of posterior density with respect to both of the dual variables and the hyperparameters ( and in our notations) are also difficult to compute. The previous study avoided these difficulties by using only a single GP and fixing the hyperparameter values. In contrast, we use a representation [35] with a reduced number of primal variables, which makes the dependence on hyperparameters easier to compute.

In our numerical study, the dependence of computation time on model size does not precisely agree with theoretical expectations (Section 2.2.1), presumably because the GPU accelerator carries out many arithmetic operations in parallel, and the effect of the size of multiplied matrices in the examined range is masked by this parallelism. As we have discussed in Section 2.2.1, with an optimised computation order, the gradient flow for RMHMC can be calculated with costs of the same complexity as the multiplication of two matrices. Although this is a power of model size with exponent between two and three, the growth of the measured computation time was approximately linear. The effect of parallelism is well known for the multiplication of matrices [48] and observed for the multiplication of much larger matrices than those in our computation. Because the simulations with model sizes greater than 3844 suffered numerical instability, we could not attempt to extend the range of dimension of our experiment to see how the computational cost grows in very large models.

In numerical simulations, by dynamically programming eigendecomposition, in comparison with static one based on the divide-and-conquer algorithm, 25 to 30 percent of the computation time was saved for large models (–1924), whereas this proportion reduced for . A similar phenomenon was observed in the previous study of dynamically programmed eigendecomposition for matrix optimisation [32]. Although the efforts to speed up the eigendecomposition resulted in this relatively small improvement, the eigendecomposition is expected to eventually outweigh the computation of the gradient flow at sufficiently large d. Again, we could not directly observe this phenomenon because of the numerical instability for . Theoretically, less than 1.5 sweeps of the Jacobi method are faster than the divide-and-conquer algorithm in the large d limit (number of sweeps vs number of iterations [49]). Since the average number of sweeps in the dynamically programmed eigendecomposition was around 1.5 regardless of the model size, we could not conclude which method for eigendecomposition is preferred for a very large model. Since the Jacobi method is more suitable for parallel computing, we speculate its advantage.

For the theoretical estimation of the computational costs, the tradeoff between the increased number of sweeps in the Jacobi method due to a large stepsize and the increased leapfrogs due to a small stepsize also needs to be considered. Since the computational cost of one sweep in the Jacobi method is high, taking the largest stepsize that does not increase the average number of sweeps in a step would be the best choice. However, we could not validate this point with increasing stepsizes in our numerical simulations, because the acceptance rate was decreased by the deviation from the conservation of the Hamiltonian before the optimal point of the tradeoff was observed.

In the numerical study, we showed that RMHMC outperforms NUT-HMC. The latter apparently reaches a parameter region with higher log posterior density more quickly, but this region has turned out to be a narrow spurious region to which a small posterior probability is assigned. Such entrapment is a well-known phenomenon and was the main motivation for the development of RMHMC [41]. Thus, the rescaling of MC moves according to the curvature of log posterior density has been suggested to play a crucial part in reaching the centre of the posterior, and the MC methods commonly used in statistics (e.g., metropolis-adjusted Langevin MC used in Ref. [23]) are not expected to allow for effective sampling in hierarchical GP models used in machine learning. However, various elaborations have been introduced to Euclidean HMC and related Langevin algorithms but not yet to RMHMC. For example, avoiding random walk behavior with a no-U-turn mechanism was proposed for Euclidean HMC [50] and RMHMC [51], but it has not yet been properly implemented for the latter. The friction mechanism introduced to Euclidean Langevin MC [52,53] suppresses inefficient oscillatory behaviour and could also be beneficial if applied to RMHMC. One factor that might have hindered elaboration of RMHMC in this regard is the previously poor performance of the plain RMHMC. Now that we have demonstrated improved RMHMC performance, further development in this direction should be encouraged.

In comparison with INLA, we observed that INLA is faster in the computation of BME for the nonlinear Bayesian logistic regression with simulated data. This calculation might be made even faster, if the joint posterior for hyperparameters is successfully approximated with the CCD strategy [19]. However, this approach must first identify the peak of the joint posterior for hyperparameters, which is not trivial in our example, unlike in the latent Gaussian model studied by INLA. With the simple grid-based integration, the computation time is much longer than expected from the performance of INLA for the hierarchical GP model with short-range correlation [23]. While the number of hyperparameters is two in our simplest example, the computation time grows exponentially with this number.

Indeed, the computation time was intolerably large for INLA of NMES dataset with the nonlinear model of the conditional mean (and variance), as we used the simple grid-based numerical integration. This difficulty was also due to the non-log concavity of the likelihood term. For the non-log concave, highly stretched/compressed posterior density, only repeated alternate applications of l-BFGS effectively worked. Straightforward applications of l-BFGS and ordinary gradient descent algorithms failed to identify the solution within a reasonable computation time, presumably because of the non-log concavity and the highly stretched/compressed landscape of the density, respectively. The scalable performance of RMHMC shown in Table 1 was in stark contrast with INLA in these respects. Here, note that the issue concerning the non-log concavity may be alleviated by the use of a trust region method [54]. Since the trust region method needs fine tuning and a choice of suitable subroutines and is still a theoretical subject for active research, we did not attempt to improve this point.

Although we have successfully shown that RMHMC can be greatly accelerated, it is fair to note that we restricted our investigation to simple model settings. Bayesian multiple-kernel models have been shown to have favorable statistical properties when irrelevant GP is plugged out with sparsifying mechanisms such as a prior that imposes a penalty according to the number of included GPs [6]. For this purpose, reversible jump mechanisms [55,56] must be introduced to RMHMC. Roughly speaking, this amounts to performing a shorter version of the MC integration in the calculation of BME multiple times in the simulation. For real-world applications, more elaborate structured models, such as GPDM for time-series data [2], must sometimes be used. In this case, RMHMC for GP must be combined with other MC methods, such as sequential MC [57,58]. Whether the proposed method works within a reasonable computation time when it is tailored to the models described above needs to be investigated.

Although the present work was intended to solve a biometrical and econometrical problem, unbiased effect estimation with Bayesian models requires further theoretical development, not just an accelerated implementation. The posterior we inferred with NMES data was asymptotically biased, as are essentially all machine learning estimators. Therefore, in order to complete the causal inference with the biased propensity function, one needs to construct a corrected estimator for the treatment effect. This may be carried out by using the framework of doubly-robust debiased machine learning (DML) [59] (see our previous work [60] for the application of DML to a model based on multiple reproducing kernel Hilbert spaces). However, its application is not straightforward, because the hierarchical Bayesian model is apparently singular, whereas DML relies on the asymptotic normality of the estimators. Since the model can be made regular by fixing parts of the model, the framework of DML may be applied to a regular submodel conditioned on suitable hyperparameter values. As the focus of the present study is on the efficiency of RMHMC, we leave this development to a future works.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/math14010146/s1, The source codes used for generating the presented data are included in SupplementaryFiles.zip together with a document describing how to use the program codes. References [61,62,63] are cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.H.; methodology, T.H.; software, T.H.; validation, T.H. and S.A.; investigation, T.H. and S.A.; writing—original draft preparation, T.H.; writing—review and editing, T.H. and S.A.; project administration, T.H.; funding acquisition, S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Sciences and Technology (MEXT) of the Japanese government and the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under grant numbers JP18km0605001 and JP223fa627011.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to two medical IT companies, 4DIN Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan) and Phenogen Medical Corporation (Tokyo, Japan) for financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that this study received funding from two medical IT companies, 4DIN Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan) and Phenogen Medical Corporation (Tokyo, Japan). The funders were not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article, or the decision to submit it for publication.

Appendix A. Reduced-Rank Representation of GPs (Svensson et al. and Solin and Särkkä)

For a -dimensional translation-invariant isotropic kernel function describing the covariance of a GP, Solin and Särkkä introduced the following approximation in a rectangular domain :

with the eigenfunctions and eigenvalues

and

In the above, is the spectral density of the GP related to the kernel function via the Wiener–Khinchin theorem:

In the present study, we focus on the one-dimensional () case. Then, the GP is represented in the form of Equation (5). We also refer readers to Svensson et al. [10] for more details about its implementation. Unlike Svensson et al. [10], we used scalar-valued GPs, and thus, the matrix normal distributions and inverse-Wishart distributions they used simply reduces to normal distributions and inverse-Gamma distributions in our case. By applying the Fourier transform to , we obtain . Considering also Equation (A1), we have

and

In practice, we dropped from , which amounts to rescaling of .

Table A1.

Mathematical notations.

Table A1.

Mathematical notations.

| Symbols | Description |

|---|---|

| The sets of real numbers and d-dimensional Euclidean space | |

| The smallest integer that is greater than or equals a | |

| , | Transposition of vector v and matrix A |

| The i-th element of vector v | |

| The element of matrix A in the i-th row of the j-th column | |

| 1 | Vector whose i-th element is |

| 2 | Matrix whose i-th row of the j-th column is |

| Diagonal matrix whose i-th element is | |

| The trace of matrix A | |

| Element a of a set | |

| The Hadamard product of A and B | |

| The number of elements in a set | |

| () | Expectation of the argument random variable (for the specified distribution) |

| Variance of the argument random variable | |

| Empirical standard deviation of the argument variable | |

| Equation defining the object on the left-hand side | |

| Abbreviation of | |

| , () | Independently and identically distributed (objects drawn from the right-hand side) |

| Uniform probability distribution over the open interval | |

| Gaussian probability distribution with mean and (co)variance | |

| Inverse Gamma probability distribution with shape and scale parameters | |

| Bernoulli probability distribution (value 1 with probability p, or 0 otherwise) |

1 Sometimes a combinatorial index such as vec({vkm}(k,m)) is used. In this example, the index runs through all possible values for the combination (k,m). 2 The first and second subscripts of the bracket {·} specify the indices for the row and column, respectively.

Appendix B. MC Integration for the Calculation of BME (Calderhead and Girolami)

BME for the model with parameters for approximately describing and hyperparameter (with prior densities and ) is defined as the following marginal likelihood [13]:

In a hierarchical model, carrying out the above integration is usually intractable. If the joint density is approximately Gaussian, the following Laplace approximation can be used: for ,

where denotes the maximum a posteriori value of v, and and denotes the peak value and the negative Hessian of the logarithm of the joint density at .

The above formula cannot be used when the deviation of the joint density from the Gaussian approximation is large. This is often the case when we use a singular (or nearly singular) hierarchical model [25]. If the model is parametric, asymptotic formula for the BME of singular models can be used [64,65]. However, these formula do not apply to the semiparametric models that we consider in this study.

Even in this case, the BME can be calculated by performing the following integration [66]:

with a set of probability densities parameterised by ():

This integration can be carried out by sampling from for each value of in discretised steps interpolating 0 and 1 and approximating the integrand with the statistics over the samples.

We carry out the above integration with multiple RMHMC indexed by each of which determines the parameter value used for the calculation of the integrand in Equation (A9) for (; and ) after performing A blocks of C leapfrogs from the initial parameter value . To determine for , we performed a single RMHMC until convergence and obtained a shared initial condition for Z RMHMCs that perform further 500 blocks of 400 leapfrogs to obtain from this initial condition.

For the above calculation, it should noted that if is small enough for all s and the number of MC moves A for each is large enough,

holds for each value of z. In this case, since A is large enough, can be considered independent. Assuming this independence, we have

and its right-hand side vanishes as the discretisation of the integration interval becomes infinitely finer.

The use of multiple RMHMCs (that is, ) is expected to accelerate the convergence. In practice, we used and and confirmed that the change in the values of A and Z ( and ) does not affect the decision about the best model.

Appendix C. Calculation of BME Values Using INLA

Since is log concave for fixed , in the numerical experiment with simulated data, we also perform the following integration:

where denotes the value of a that maximises for the given value of , and and denote the peak value and the negative Hessian of at . This is exactly the same as INLA [67,68], except for the non-sparseness of the Hessian. The three-dimensional integration in the second line was performed by discretising the rectangular region for with a mesh size (the region displayed in Figure 3A,B). For the discrete values of hyperparameters, we obtained by performing limited-memory BFGS (l-BFGS) [69] using PyTorch. For the model for the conditional mean and variance of the NMES dataset, l-BFGS was alternately applied to the models of the mean and variance, until convergence. Most of the computation was performed on a single GPU, namely, the same computing environment as for the MC integration. Since we did not use linear kernels for simulated data, we can simply ignore the hyperparameter for linear kernels. Similarly, for the linear models for the NMES dataset, the hyperparameters for Gaussian kernels can be ignored.

References

- Lawrence, N. Gaussian process latent variable models for visualisation of high dimensional data. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2003, 16, 329. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Hertzmann, A.; Fleet, D.J. Gaussian process dynamical models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2005, 18, 1441–1448. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C.K.; Rasmussen, C.E. Gaussian Processes for Machine Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- van der Vaart, A.W.; van Zanten, J.H. Rates of contraction of posterior distributions based on Gaussian process priors. Ann. Stat. 2008, 36, 1435–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Vaart, A.; van Zanten, H. Information Rates of Nonparametric Gaussian Process Methods. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2095–2119. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, T. PAC-Bayesian Bound for Gaussian Process Regression and Multiple Kernel Additive Model. In Proceedings of the 25th Annual Conference on Learning Theory, Edinburgh, UK, 25–27 June 2012; Mannor, S., Srebro, N., Williamson, R.C., Eds.; PMLR: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012; Volume 23, pp. 8.1–8.20. [Google Scholar]

- Iwata, T.; Duvenaud, D.; Ghahramani, Z. Warped mixtures for nonparametric cluster shapes. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Ninth Conference on Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence, Bellevue, WA, USA, 11–15 August 2013; pp. 311–320. [Google Scholar]

- Damianou, A.; Lawrence, N.D. Deep Gaussian Processes. In Proceedings of the Sixteenth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 29 April–1 May 2013; Carvalho, C.M., Ravikumar, P., Eds.; PMLR: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013; Volume 31, pp. 207–215. [Google Scholar]

- Frigola, R.; Lindsten, F.; Schön, T.B.; Rasmussen, C.E. Bayesian Inference and Learning in Gaussian Process State-Space Models with Particle MCMC. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Burges, C., Bottou, L., Welling, M., Ghahramani, Z., Weinberger, K., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Volume 26. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, A.; Solin, A.; Särkkä, S.; Schön, T. Computationally Efficient Bayesian Learning of Gaussian Process State Space Models. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, Cadiz, Spain, 9–11 May 2016; Gretton, A., Robert, C.C., Eds.; PMLR: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; Volume 51, pp. 213–221. [Google Scholar]

- Yerramilli, S.; Iyer, A.; Chen, W.; Apley, D.W. Fully Bayesian Inference for Latent Variable Gaussian Process Models. SIAM/ASA J. Uncertain. Quantif. 2023, 11, 1357–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finocchio, G.; Schmidt-Hieber, J. Posterior Contraction for Deep Gaussian Process Priors. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2023, 24, 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, C.M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Paquet, U.; Fraccaro, M. An Efficient Implementation of Riemannian Manifold Hamiltonian Monte Carlo for Gaussian Process Models. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.11893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandita, P.; Tsilifis, P.; Ghosh, S.; Wang, L. Scalable Fully Bayesian Gaussian Process Modeling and Calibration with Adaptive Sequential Monte Carlo for Industrial Applications. J. Mech. Des. 2021, 143, 074502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, A.G.d.G.; van der Wilk, M.; Nickson, T.; Fujii, K.; Boukouvalas, A.; León-Villagrá, P.; Ghahramani, Z.; Hensman, J. GPflow: A Gaussian process library using TensorFlow. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2017, 18, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, J.; Pleiss, G.; Weinberger, K.Q.; Bindel, D.; Wilson, A.G. GPyTorch: Blackbox Matrix-Matrix Gaussian Process Inference with GPU Acceleration. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Bengio, S., Wallach, H., Larochelle, H., Grauman, K., Cesa-Bianchi, N., Garnett, R., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 31. [Google Scholar]

- Kimeldorf, G.S.; Wahba, G. A correspondence between Bayesian estimation on stochastic processes and smoothing by splines. Ann. Math. Stat. 1970, 41, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rue, H.; Martino, S.; Chopin, N. Approximate Bayesian inference for latent Gaussian models by using integrated nested Laplace approximations. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Stat. Methodol.) 2009, 71, 319–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunn, D.; Spiegelhalter, D.; Thomas, A.; Best, N. The BUGS project: Evolution, critique and future directions. Stat. Med. 2009, 28, 3049–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, S.D. Stan Reference Manual, Version 2.37. 2025. Available online: https://mc-stan.org/docs/reference-manual/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Lindgren, F.; Rue, H. Bayesian Spatial Modelling with R-INLA. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 63, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B.M.; Diggle, P.J. INLA or MCMC? A tutorial and comparative evaluation for spatial prediction in log-Gaussian Cox processes. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 2014, 84, 2266–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rue, H.; Riebler, A.; Sorbye, S.H.; Illian, J.B.; Simpson, D.P.; Lindgren, F.K. Bayesian Computing with INLA: A Review. Annu. Rev. Stat. Its Appl. 2017, 4, 395–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S. Algebraic Geometry and Statistical Learning Theory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009; Volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, T.G.; Rue, H. Extending integrated nested Laplace approximation to a class of near-Gaussian latent models. Scand. J. Stat. 2014, 41, 893–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensman, J.; Matthews, A.G.d.G.; Filippone, M.; Ghahramani, Z. MCMC for variationally sparse Gaussian processes. In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Cambridge, MA, USA, 22–26 November 2015; NIPS’15. Volume 1, pp. 1648–1656. [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt, M.J. A general metric for Riemannian manifold Hamiltonian Monte Carlo. In International Conference on Geometric Science of Information; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 327–334. [Google Scholar]

- Cobb, A.D.; Baydin, A.G.; Markham, A.; Roberts, S.J. Introducing an Explicit Symplectic Integration Scheme for Riemannian Manifold Hamiltonian Monte Carlo. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.06243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. PyTorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Abadi, M.; Agarwal, A.; Barham, P.; Brevdo, E.; Chen, Z.; Citro, C.; Corrado, G.S.; Davis, A.; Dean, J.; Devin, M.; et al. TensorFlow: Large-Scale Machine Learning on Heterogeneous Systems, 2015. Software. Available online: http://tensorflow.org/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Fawzi, H.; Goulbourne, H. Faster proximal algorithms for matrix optimization using Jacobi-based eigenvalue methods. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Ranzato, M., Beygelzimer, A., Dauphin, Y., Liang, P., Vaughan, J.W., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 34, pp. 11397–11408. [Google Scholar]

- Van Weert, P.; Gregoire, M. C++ 17 Standard Library Quick Reference: A Pocket Guide to Data Structures, Algorithms, and Functions; Apress: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- NVIDA Inc. NVIDA HPC SDK Version 23.1 Documentation. 2023. Available online: https://docs.nvidia.com/hpc-sdk/archive/23.1/index.html (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Solin, A.; Särkkä, S. Hilbert space methods for reduced-rank Gaussian process regression. Stat. Comput. 2020, 30, 419–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Choi, S. Hierarchical Gaussian process regression. In Proceedings of the 2nd Asian Conference on Machine Learning, JMLR Workshop and Conference Proceedings, Tokyo, Japan, 8–10 November 2010; pp. 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Bach, F.; Jordan, M. Kernel independent component analysis. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Duane, S.; Kennedy, A.; Pendleton, B.J.; Roweth, D. Hybrid Monte Carlo. Phys. Lett. B 1987, 195, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, R.M. Probabilistic Inference Using Markov Chain MONTE Carlo Methods. 1993. Available online: https://www.cs.princeton.edu/courses/archive/fall07/cos597C/readings/Neal1993.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Neal, R.M. Bayesian Learning for Neural Networks; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 118. [Google Scholar]

- Girolami, M.; Calderhead, B. Riemann manifold Langevin and Hamiltonian Monte Carlo methods. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Stat. Methodol.) 2011, 73, 123–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gall, F.L.; Urrutia, F. Improved rectangular matrix multiplication using powers of the coppersmith-winograd tensor. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Ninth Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms, New Orleans, LA, USA, 7–10 January 2018; pp. 1029–1046. [Google Scholar]

- van Kempen, H.P.M. On the quadratic convergence of the special cyclic Jacobi method. Numer. Math. 1966, 9, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golub, G.H.; Van Loan, C.F. Matrix Computations; JHU Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, E.; Dominici, F.; Griswold, M.; Zeger, S.L. Disease cases and their medical costs attributable to smoking: An analysis of the national medical expenditure survey. J. Econom. 2003, 112, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, K.; Van Dyk, D.A. Causal inference with general treatment regimes: Generalizing the propensity score. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2004, 99, 854–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galagate, D.; Schafer, J.L. Causal Inference with a Continuous Treatment and Outcome: Alternative Estimators for Parametric Dose-Response Functions with Applications. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NVIDIA Inc. NVIDIA Developer Forum: CUBLAS Dgemm Performance Query. 2012. Available online: https://forums.developer.nvidia.com/t/reasonable-timing-with-cublas-dgemm-and-sgemm/14261 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Lung-Sheng, C. Jacobi-Based Eigenvalue Solver on GPU. A Shared Slide Presented in GPU Technology Conference. 2017. Available online: https://on-demand.gputechconf.com/gtc/2017/presentation/s7121-lung-sheng-chien-jacobi-based-eigenvalue-solver.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Hoffman, M.D.; Gelman, A. The No-U-Turn Sampler: Adaptively Setting Path Lengths in Hamiltonian Monte Carlo. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2014, 15, 1593–1623. [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt, M.J. Generalizing the No-U-Turn Sampler to Riemannian Manifolds. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1304.1920. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X.; Chatterji, N.S.; Bartlett, P.L.; Jordan, M.I. Underdamped Langevin MCMC: A non-asymptotic analysis. In Proceedings of the 31st Conference On Learning Theory, Stockholm, Sweden, 6–9 July 2018; Bubeck, S., Perchet, V., Rigollet, P., Eds.; PMLR: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; Volume 75, pp. 300–323. [Google Scholar]

- Dalalyan, A.S.; Riou-Durand, L. On sampling from a log-concave density using kinetic Langevin diffusions. Bernoulli 2020, 26, 1956–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conn, A.R.; Gould, N.I.; Toint, P.L. Trust Region Methods; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Green, P.J. Reversible jump Markov chain Monte Carlo computation and Bayesian model determination. Biometrika 1995, 82, 711–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagiannis, G.; Andrieu, C. Annealed Importance Sampling Reversible Jump MCMC Algorithms. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 2013, 22, 623–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moral, P. Feynman-Kac Formulae: Genealogical and Interacting Particle Systems with Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chopin, N.; Papaspiliopoulos, O. An Introduction to Sequential Monte Carlo; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Chernozhukov, V.; Chetverikov, D.; Demirer, M.; Duflo, E.; Hansen, C.; Newey, W.; Robins, J. Double/debiased machine learning for treatment and structural parameters. Econom. J. 2018, 21, C1–C68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, T.; Asai, S. Debiased Maximum Likelihood Estimators of Hazard Ratios Under Kernel-Based Machine Learning Adjustment. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, S.; Juckeland, G. OpenACC for Programmers: Concepts and Strategies; Addison-Wesley Professional: Boston, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Farber, R. Parallel Programming with OpenACC; Newnes: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Reinders, J.; Ashbaugh, B.; Brodman, J.; Kinsner, M.; Pennycook, J.; Tian, X. Data Parallel C++: Mastering DPC++ for Programming of Heterogeneous Systems Using C++ and SYCL; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, S. A widely applicable Bayesian information criterion. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2013, 14, 867–897. [Google Scholar]

- Drton, M.; Plummer, M. A Bayesian Information Criterion for Singular Models. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 2017, 79, 323–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderhead, B.; Girolami, M. Estimating Bayes factors via thermodynamic integration and population MCMC. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2009, 53, 4028–4045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubin, A.; Storvik, G. Estimating the marginal likelihood with Integrated nested Laplace approximation (INLA). arXiv 2016, arXiv:1611.01450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Rubio, V.; Rue, H. Markov chain Monte Carlo with the Integrated Nested Laplace Approximation. Stat. Comput. 2018, 28, 1033–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.C.; Nocedal, J. On the limited memory BFGS method for large scale optimization. Math. Program. 1989, 45, 503–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.