Perception–Production of Second-Language Mandarin Tones Based on Interpretable Computational Methods: A Review

Abstract

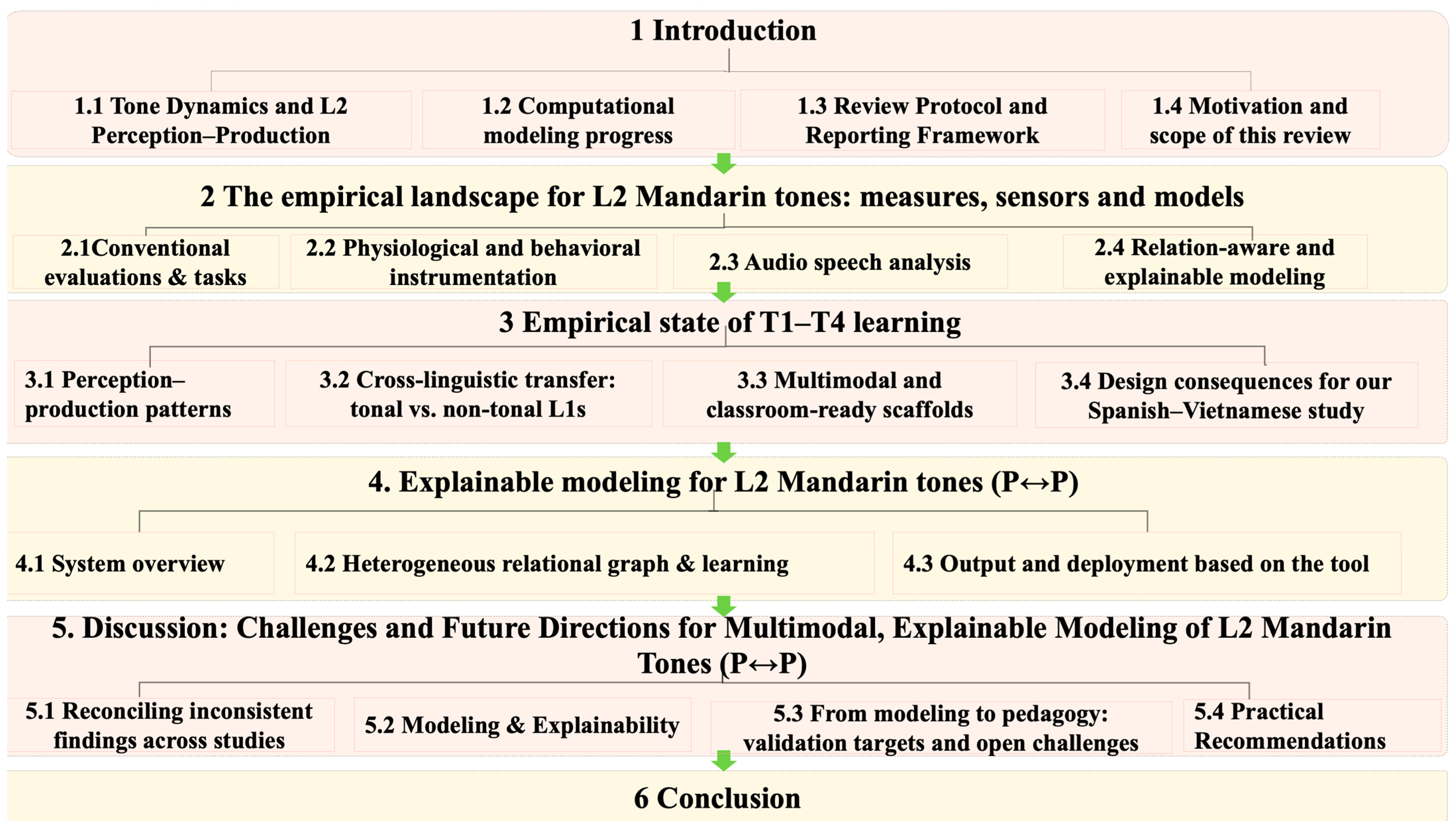

1. Introduction

1.1. Tone Dynamics and L2 Perception–Production

1.2. Computational Modeling Progress

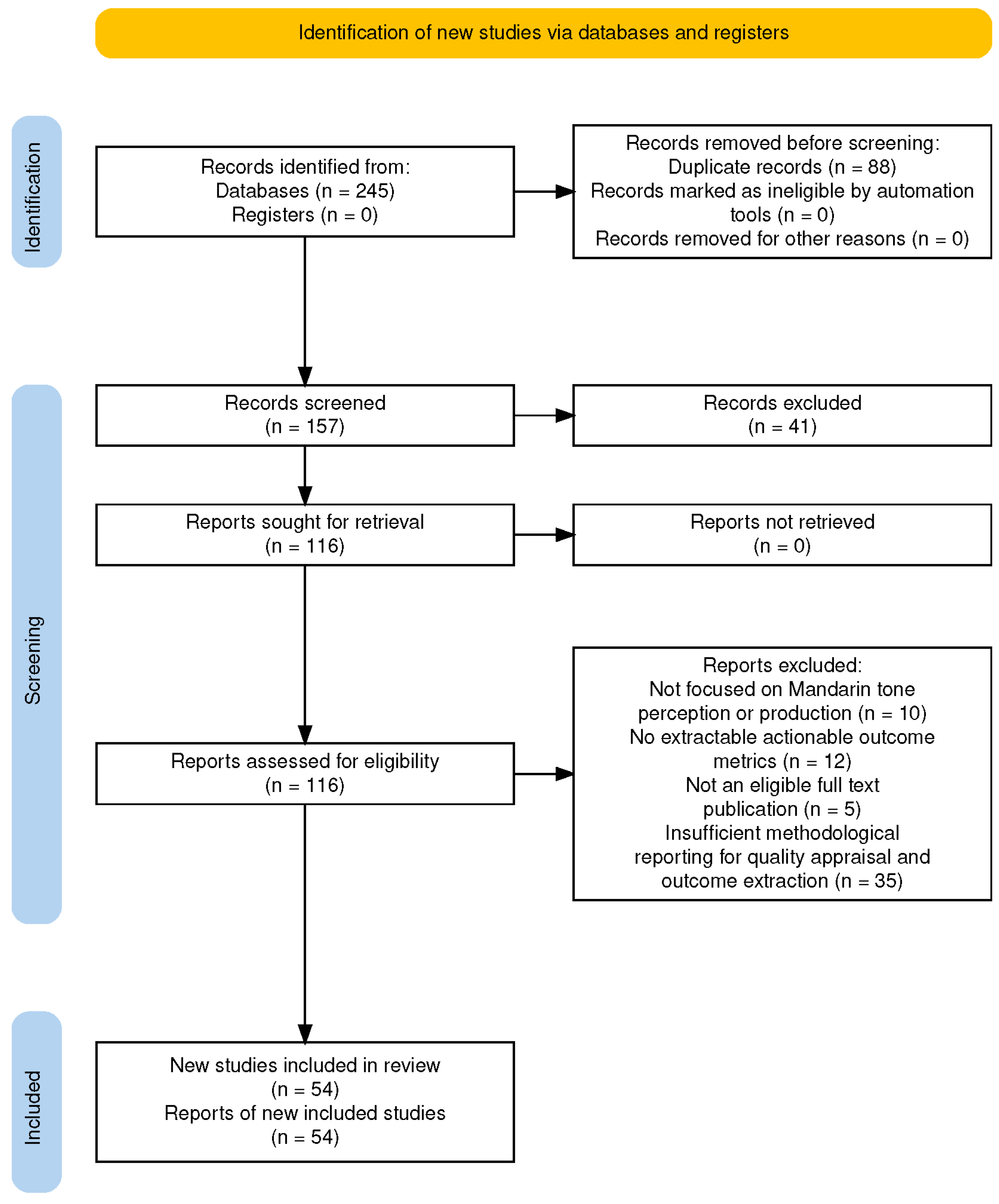

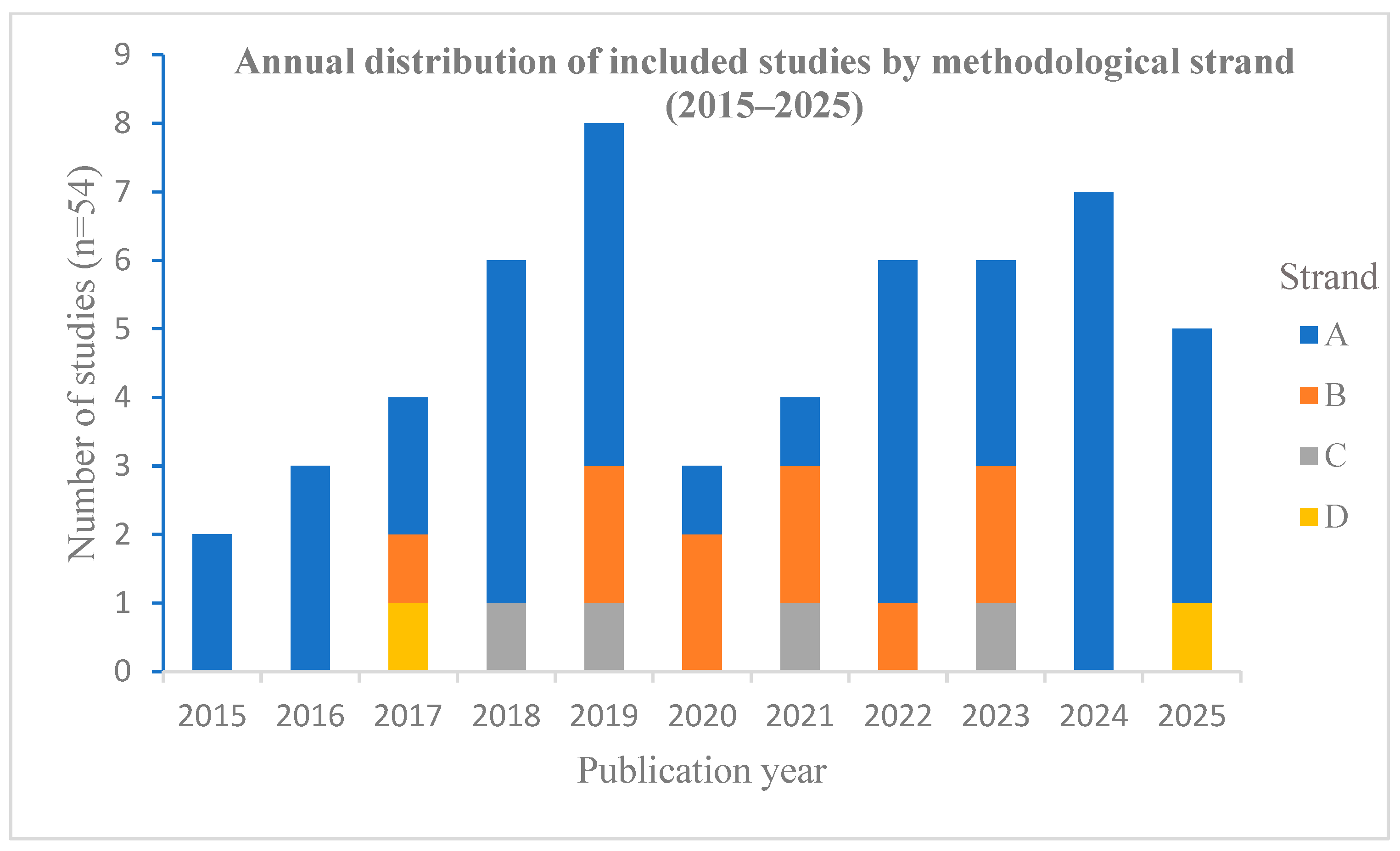

1.3. Review Protocol and Reporting Framework

1.4. Motivation and Scope of This Review

- Explainable AI (XAI): give direct indication of attributions (e.g., reliance on a late peak timing), and of counterfactuals (minimal slope increase to flip T3 → T2) corresponding to some teachable parameter.

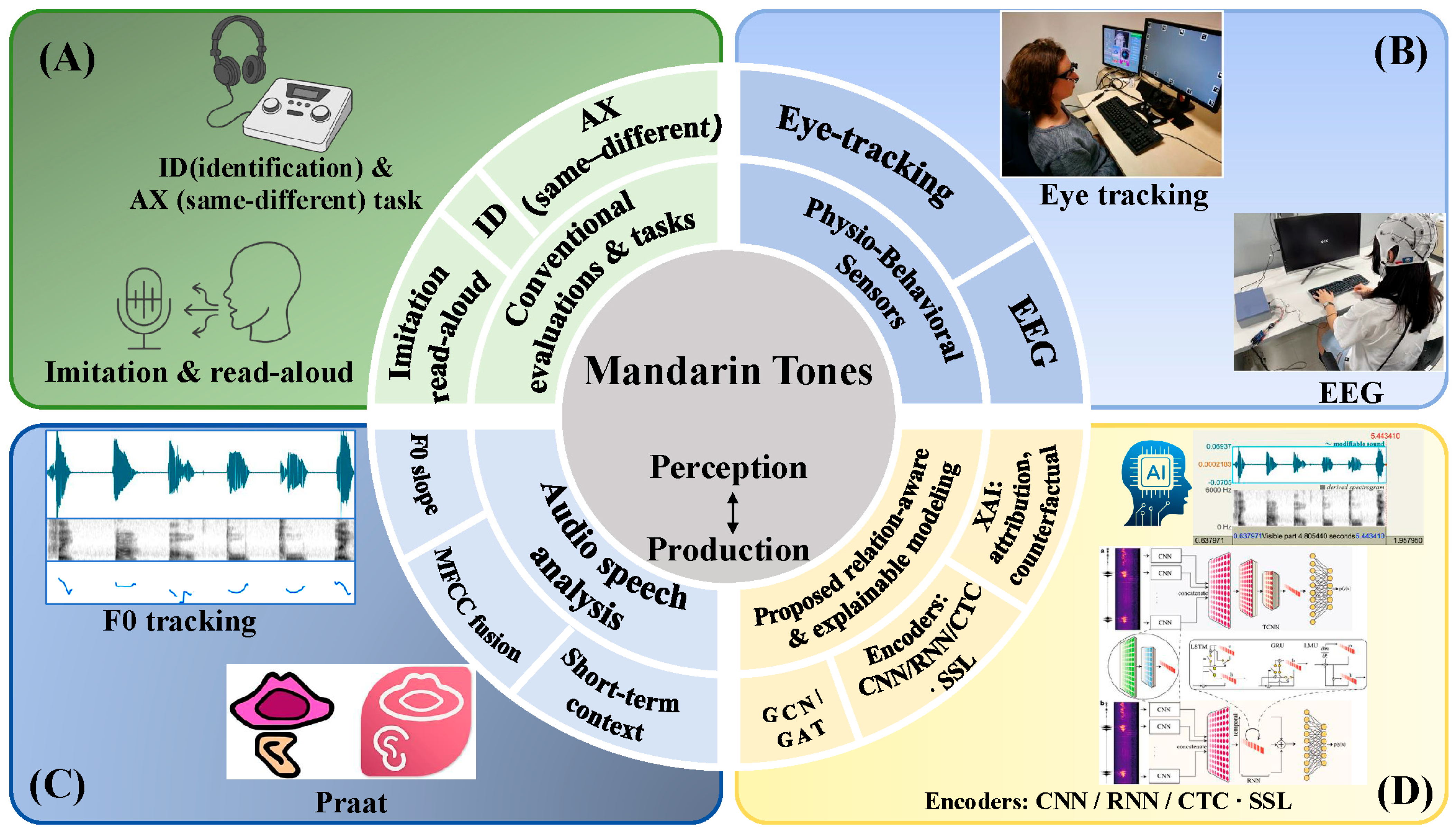

2. The Empirical Landscape for L2 Mandarin Tones: Measures, Sensors, and Models

2.1. Conventional Evaluations and Tasks

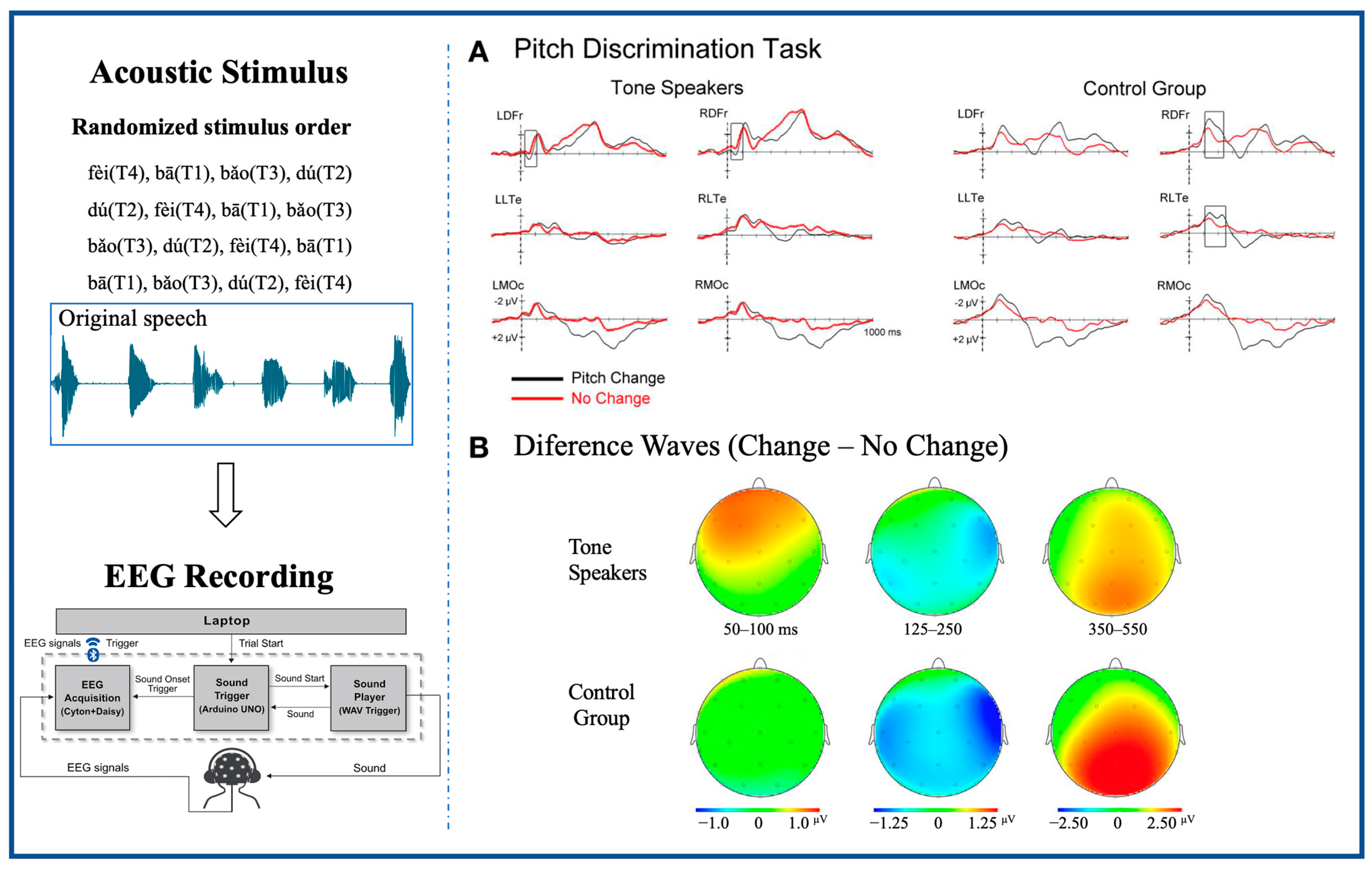

2.2. Physiological and Behavioral Instrumentation (Contact-Based/Contactless)

2.3. Audio Speech Analysis

2.4. Relation-Aware and Explainable Modeling

3. Empirical States of T1–T4 Learning

3.1. Perception–Production Patterns

3.2. Cross-Linguistic Transfer: Tonal vs. Non-Tonal L1s

3.3. Multimodal and Classroom-Ready Scaffolds

3.4. Design Consequences for Our Spanish-L1 and Vietnamese-L1 Study

4. Explainable Modeling for L2 Mandarin Tones (P ↔ P)

4.1. System Overview

4.2. Heterogeneous Relational Graph and Learning

4.2.1. Message Passing

4.2.2. Node and Edge Features

4.2.3. Joint Objectives: Tone Classification and Parameter Regression

4.2.4. Explaining the Model: Feature Attribution and Counterfactuals

4.2.5. Evaluation Protocol for P ↔ P and Pedagogy

4.3. Output and Deployment Based on the Tool

5. Discussion: Challenge and Future Directions for Multimodal Explainable Model of L2 Mandarin Tones (P ↔ P)

5.1. Reconciling Inconsistent Findings Across Studies

5.1.1. Data and Task Collection of the Current Corpora Fall Short

5.1.2. Bias, Confounds, and Cross-Strand Validity

5.2. Modeling and Explainability

5.3. From Modeling to Pedagogy: Validation Targets and Open Challenges

5.3.1. Mapping Model Outputs to Teaching Actions

5.3.2. Scope of This Review and Recommended Validation Plan

5.3.3. Open Challenges and Next Steps

5.4. Practical Recommendations

5.4.1. Minimum Reporting Set for Learner-Facing Evaluation

5.4.2. Fairness, Ethics, and Governance for Classroom Deployment

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Search Strategy and Database-Specific Search Strings (2015–2025)

Appendix A.1. Google Scholar

Appendix A.2. China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI)

Appendix A.3. Handling of Indexed Sources and the Figure 4 Subset

Appendix B. Risk-of-Bias Appraisal Checklist

Appendix B.1. Participant Characterization and Proficiency Control

Appendix B.2. Task and Stimulus Specification

Appendix B.3. Measurement Reliability

Appendix B.4. Evaluation Validity for Computational Modeling

Appendix B.5. Metric Definition and Reporting Transparency

Appendix B.6. Replicability-Critical Transparency

| Domain | What We Check (Signaling Questions) | Adequate (2) | Partial (1) | Unclear/Not Reported (0) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 Participant characterization and proficiency control | Are L1 background and L2 proficiency/experience reported? Are inclusion criteria and key confound addressed? | L1 + N + proficiency (or placement) reported; inclusion criteria and key confound addressed. | N reported but proficiency/experience or confounds incomplete. | Learner profile insufficiently described; key confounds not addressed. |

| B2 Task and stimulus specification | Are perception/production tasks, tone targets, contexts, stimuli, and scoring criteria specified for replication? | Tasks, stimuli/contexts, and scoring clearly specified. | Task described but stimulus/context/scoring incomplete. | Task/stimuli insufficiently described. |

| B3 Measurement reliability | Is the acoustic/physiological pipeline specified (e.g., Praat settings; EEG/eye-tracking preprocessing)? Is reliability/QA reported where human labeling is involved? | Pipeline specified and reliability/QA reported (e.g., rater agreement, error handling, outlier rules). | Pipeline specified but reliability/QA partial or absent. | Pipeline unclear; reliability/QA not reported. |

| B4 Evaluation validity for computational modelling | If modelling is used: are training/validation protocols and leakage control specified (splits, CV, speaker/item independence, baselines)? | Clear evaluation protocol with leakage control and meaningful baselines. | Some evaluation details provided but safeguards unclear. | No clear evaluation protocol/validation. |

| B5 Metric definition and reporting transparency | Are performance outcomes clearly defined and reported with sufficient granularity (e.g., per-tone, confusion; MAE/RMSE for parameters; CIs)? | Reports recognition metric(s) and either parameter errors or uncertainty/effect sizes. | Reports only coarse metrics without uncertainty/parameter errors. | Outcomes not quantitatively reported or not extractable. |

| B6 Replicability-critical transparency | Are replicability-critical details available (preprocessing, features, model settings; data/code/materials access)? | Data/code/materials or full settings available (repo or detailed supplement). | Partial availability. | No availability statement or insufficient detail. |

References

- Ethnologue. Chinese, Mandarin (cmn). Available online: https://www.ethnologue.com/language/cmn (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Xu, Y.; Wang, Q.E. Pitch targets and their realization: Evidence from Mandarin Chinese. Speech Commun. 2001, 33, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Adda-Decker, M.; Lamel, L. Mandarin lexical tone duration: Impact of speech style, word length, syllable position and prosodic position. Speech Commun. 2023, 146, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, M.J.W. Tone; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P.; Schwartz, R.G.; Jenkins, J.J. Perception and production of lexical tones by 3-year-old, Mandarin-speaking children. Perception 2005, 48, 1065–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehinger, B.V.; Groß, K.; Ibs, I.; König, P. A new comprehensive eye-tracking test battery concurrently evaluating the Pupil Labs glasses and the EyeLink 1000. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.; Baek, S.-C.; Lim, Y.; Chung, J.H. Validation of cost-efficient EEG experimental setup for neural tracking in an auditory attention task. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, G.; Kshirsagar, M.; Zhong, M.; Gholami, S.; Ferres, J.L. Comparing recurrent convolutional neural networks for large scale bird species classification. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelzl, E.; Lau, E.F.; Guo, T.; DeKeyser, R. Advanced Second Language Learners’ perception of Lexical Tone Contrasts. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 2019, 41, 59–86. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Spence, M.M.; Jongman, A.; Sereno, J.A. Training American listeners to perceive Mandarin tones. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1999, 106, 3649–3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; DeKeyser, R. Perception practice, production practice, and musical ability in L2 Mandarin tone-word learning. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 2017, 39, 593–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, K.K.; Lu, Y.-A.; Wang, Y. Examining Speech Perception–Production Relationships Through Tone Perception and Production Learning Among Indonesian Learners of Mandarin. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prom-On, S.; Xu, Y.; Thipakorn, B. Modeling tone and intonation in Mandarin and English as a process of target approximation. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2009, 125, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y. Fundamental frequency peak delay in Mandarin. Phonetica 2001, 58, 26–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, I.-H.; Yeh, W.-T. The interaction between timescale and pitch contour at pre-attentive processing of frequency-modulated sweeps. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 637289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y. Effects of tone and focus on the formation and alignment of f0contours. J. Phon. 1999, 27, 55–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, W.; Liu, J.; Wang, T.; Cho, S.; Lee, Y.-C. Comparisons of Mandarin on-focus expansion and post-focus compression between native speakers and L2 learners: Production and machine learning classification. Speech Commun. 2025, 173, 103280. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y. Prosody, tone, and intonation. In The Routledge Handbook of Phonetics; Routledge: Oxfordshire, England, 2019; pp. 314–356. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, A.; Hirata, Y.; Kelly, S.D. Exploring the effects of imitating hand gestures and head nods on L1 and L2 Mandarin tone production. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2018, 61, 2179–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Jia, L.; Gao, F.; Wang, J. Visual–auditory integration and high-variability speech can facilitate Mandarin Chinese tone identification. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2022, 65, 4096–4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfroid, A.; Lin, C.H.; Ryu, C. Hearing and seeing tone through color: An efficacy study of web-based, multimodal Chinese tone perception training. Lang. Learn. 2017, 67, 819–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Perception of Mandarin tones: The effect of L1 background and training. Mod. Lang. J. 2013, 97, 144–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-C.; Wang, T.; Liberman, M. Production and perception of tone 3 focus in Mandarin Chinese. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blicher, D.L.; Diehl, R.L.; Cohen, L.B. Effects of syllable duration on the perception of the Mandarin Tone 2/Tone 3 distinction: Evidence of auditory enhancement. J. Phon. 1990, 18, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, T.; Zhang, J.; Cao, W. A comparative study of perception of tone 2 and tone 3 in Mandarin by native speakers and Japanese learners. In Proceedings of the 2012 8th International Symposium on Chinese Spoken Language Processing, Hong Kong, 5–8 December 2012; pp. 431–435. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, G.; Froud, K. Categorical perception of lexical tones by English learners of Mandarin Chinese. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2016, 140, 4396–4403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, G.; Xu, Z.; Bai, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Zhao, R.; Wu, Y.; Ming, D. EEG-based assessment of temporal fine structure and envelope effect in mandarin syllable and tone perception. Cereb. Cortex 2023, 33, 11287–11299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y. Cross-Language Studies of Tonal Perception: Hemodynamic, Electrophysiological and Behavioral Evidence. Ph.D. Thesis, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Q. Influence of L1 Background on Categorical Perception of Mandarin Tones by Russian and Vietnamese Listeners. Int. J. Engl. Linguist. 2019, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Is Cantonese lexical tone information important for sentence recognition accuracy in quiet and in noise? PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Guo, Q.; Deng, Y.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, H. Development of Mandarin lexical tone identification in noise and its relation with working memory. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2023, 66, 4100–4116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Hu, Y.; Yang, X.; Peng, G. Acoustic Features of Mandarin Tone Production in Noise: A Comparison Between Chinese Native Speakers and Korean L2 Learners. In Proceedings of the Interspeech 2025, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 17–21 August 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Silpachai, A. The role of talker variability in the perceptual learning of Mandarin tones by American English listeners. J. Second Lang. Pronunciation 2020, 6, 209–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H. A Method of Teaching English Speaking Learners to Produce Mandarin-Chinese Tones. Ph.D. Thesis, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Baills, F.; Suarez-Gonzalez, N.; Gonzalez-Fuente, S.; Prieto, P. Observing and producing pitch gestures facilitates the learning of Mandarin Chinese tones and words. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 2019, 41, 33–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Gonzalez-Fuente, S.; Baills, F.; Prieto, P. Observing pitch gestures favors the learning of Spanish intonation by Mandarin speakers. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 2019, 41, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Ryant, N.; Cai, X.; Church, K.; Liberman, M. Automatic recognition of suprasegmentals in speech. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2108.01122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, G.; Watkins, M.; Alishahi, A.; Bisazza, A. Encoding of lexical tone in self-supervised models of spoken language. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.16865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chen, N.F.; Siniscalchi, S.M.; Lee, C.-H. Improving mandarin tone mispronunciation detection for non-native learners with soft-target tone labels and blstm-based deep models. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Calgary, AB, Canada, 15–20 April 2018; pp. 6249–6253. [Google Scholar]

- de la Fuente, A.; Jurafsky, D. A layer-wise analysis of Mandarin and English suprasegmentals in SSL speech models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.13678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Tian, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Li, M. A mandarin tone recognition algorithm based on random forest and features fusion. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Control Engineering and Artificial Intelligence, Sanya, China, 28–30 January 2023; pp. 168–172. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Chen, F. EEG-based classification of imaginary Mandarin tones. In Proceedings of the 2020 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Montréal, QC, Canada, 20–24 July 2020; pp. 3889–3892. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, D.; Zhu, X.; Xue, L.; Li, T.; Lv, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Xie, L. HIGNN-TTS: Hierarchical Prosody Modeling With Graph Neural Networks for Expressive Long-Form TTS. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Automatic Speech Recognition and Understanding Workshop (ASRU), Taipei, Taiwan, 16–20 December 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, A.; Wang, J.; Cheng, N.; Peng, H.; Zeng, Z.; Kong, L.; Xiao, J. Graphpb: Graphical representations of prosody boundary in speech synthesis. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Spoken Language Technology Workshop (SLT), virtual, 19–22 January 2021; pp. 438–445. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarivate. EndNote 2025; Build 21347; Clarivate: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem. Medica 2012, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viera, A.J.; Garrett, J.M. Understanding interobserver agreement: The kappa statistic. Fam. Med. 2005, 37, 360–363. [Google Scholar]

- Syriani, E.; David, I.; Kumar, G. Screening articles for systematic reviews with ChatGPT. J. Comput. Lang. 2024, 80, 101287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bei, X.; Xiang, N. Fundamental Principles of Experimental Phonetics and Practical Use of Praat; Hunan Normal University Press: Changsha, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bei, X. A Study on Mandarin Speech Acquisition in Guangzhou, Hong Kong, and Macao; China Social Sciences Press: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bei, X. The tone pattern in dialect contact. J. Chin. Linguist. 2015, 43, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Lin, L.; Zhao, L.; Ding, S.; Huang, H. Time Series Focused Neural Network for Accurate Wireless Human Gesture Recognition. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shen, J.; Han, T.; Chen, T.; Gall, H. Adversarial robustness of deep code comment generation. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 2022, 31, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Yi, L.; Wei, Z. A survey of dynamic graph neural networks. Front. Comput. Sci. 2025, 19, 196323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrahatis, A.G.; Lazaros, K.; Kotsiantis, S. Graph attention networks: A comprehensive review of methods and applications. Future Internet 2024, 16, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Cui, G.; Hu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, C.; Sun, M. Graph neural networks: A review of methods and applications. AI Open 2020, 1, 57–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Huang, H.; Zhao, L.; Wang, P.; Jiang, S.; Su, C. Reentrancy vulnerability detection based on graph convolutional networks and expert patterns under subspace mapping. Comput. Secur. 2024, 142, 103894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R. Audiovisual Perception of Mandarin Lexical Tones. Ph.D. Thesis, Bournemouth University, Poole, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wayland, R.P.; Guion, S.G. Training English and Chinese listeners to perceive Thai tones: A preliminary report. Lang. Learn. 2004, 54, 681–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Pun, S.H.; Chen, F. Mandarin tone classification in spoken speech with EEG signals. In Proceedings of the 2021 29th European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO), Dublin, Ireland, 23–27 August 2021; pp. 1163–1166. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Hu, Y.; Xu, H. Mandarin tone modeling using recurrent neural networks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.01946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugosch, L.; Tomar, V.S. Tone recognition using lifters and CTC. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.02465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Li, M. End-to-end mandarin tone classification with short term context information. In Proceedings of the 2021 Asia-Pacific Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference (APSIPA ASC), Tokyo, Japan, 14–17 December 2021; pp. 878–883. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, J.; Cai, X.; Church, K. Improved contextualized speech representations for tonal analysis. In Proceedings of the Interspeech, Dublin, Ireland, 20–24 August 2023; pp. 4513–4517. [Google Scholar]

- Schenck, K.; Beguš, G. Unsupervised Learning and Representation of Mandarin Tonal Categories by a Generative CNN. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.17859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipf, T. Semi-Supervised Classification with Graph Convolutional Networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.02907. [Google Scholar]

- Veličković, P.; Cucurull, G.; Casanova, A.; Romero, A.; Lio, P.; Bengio, Y. Graph attention networks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1710.10903. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 4768–4777. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. “Why should I trust you?” Explaining the predictions of any classifier. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 1135–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Wachter, S.; Mittelstadt, B.; Russell, C. Counterfactual explanations without opening the black box: Automated decisions and the GDPR. Harv. J. Law Tech. 2017, 31, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, L.; Malins, J.G. Encoding lexical tones in jTRACE: A simulation of monosyllabic spoken word recognition in Mandarin Chinese. Behav. Res. Methods 2017, 49, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, C. Computational Modeling of Tonal Encoding in Disyllabic Mandarin Word Production. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 24–27 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, J.; Zhang, L.; Shu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, P. Categorical perception of lexical tones in Chinese revealed by mismatch negativity. Neuroscience 2010, 170, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, G.; Froud, K. Electrophysiological correlates of categorical perception of lexical tones by English learners of Mandarin Chinese: An ERP study. Bilingualism 2019, 22, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, C.K.; Best, C.T. Cross-language perception of non-native tonal contrasts: Effects of native phonological and phonetic influences. Lang. Speech 2010, 53, 273–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.-C. Second language acquisition of Mandarin Chinese tones by tonal and non-tonal language speakers. J. Phon. 2012, 40, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Hyönä, J.; Wang, Y.; Hou, M.; Zhao, J. The role of tonal information during spoken-word recognition in Chinese: Evidence from a printed-word eye-tracking study. Mem. Cogn. 2021, 49, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhong, H. The roles of consonant, rime, and tone in mandarin spoken word recognition: An eye-tracking study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 740444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, D.M.; Jiang, Y.; Natalia, A. Visualization of tone for learning Mandarin Chinese. In Proceedings of the 4th Pronunciation in Second Language Learning and Teaching Conference, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–25 August 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, A.; Olson, D. The use of visual feedback to train L2 lexical tone: Evidence from Mandarin phonetic acquisition. In Proceedings of the 13th Pronunciation in Second Language Learning and Teaching Conference, St. Catharines, ON, Canada, 16–18 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano, R.J.; Pfordresher, P.Q.; Stanley, E.M.; Narayana, S.; Wicha, N.Y. Native experience with a tone language enhances pitch discrimination and the timing of neural responses to pitch change. Front. Psychol. 2011, 2, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Y.; Politzer-Ahles, S.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, J. Encoding category-level and context-specific phonological information at different stages: An EEG study of Mandarin third-tone sandhi word production. Neuropsychologia 2022, 175, 108367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Farris-Trimble, A.; Yeung, H.H. Contextual effects on spoken word processing: An eye-tracking study of the time course of tone and vowel activation in Mandarin. J. Exp. Psychol. 2023, 49, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Deng, W.; Meng, Z.; Chen, D. Hybrid-attention mechanism based heterogeneous graph representation learning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 250, 123963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.F.; Wee, D.; Tong, R.; Ma, B.; Li, H. Large-scale characterization of non-native Mandarin Chinese spoken by speakers of European origin: Analysis on iCALL. Speech Commun. 2016, 84, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Sun, S.; Yang, Y. ToneNet: A CNN Model of Tone Classification of Mandarin Chinese. In Proceedings of the Interspeech, Graz, Austria, 15–19 September 2019; pp. 3367–3371. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, Y.; Chen, N.; Zhu, H.; Zhu, Z.; Li, G.; Chen, Y. Auditory Spatial Attention Detection Based on Feature Disentanglement and Brain Connectivity-Informed Graph Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Interspeech 2024, Kos Island, Greece, 1–5 September 2024; pp. 887–891. [Google Scholar]

- Pastor, E.; Koudounas, A.; Attanasio, G.; Hovy, D.; Baralis, E. Explaining speech classification models via word-level audio segments and paralinguistic features. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.07733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Rad, P. Opportunities and challenges in explainable artificial intelligence (xai): A survey. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.11371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fucci, D.; Savoldi, B.; Gaido, M.; Negri, M.; Cettolo, M.; Bentivogli, L. Explainability for Speech Models: On the Challenges of Acoustic Feature Selection. In Proceedings of the 10th Italian Conference on Computational Linguistics (CLiC-it 2024), Pisa, Italy, 4–6 December 2024; pp. 373–381. [Google Scholar]

- Morett, L.M.; Chang, L.-Y. Emphasising sound and meaning: Pitch gestures enhance Mandarin lexical tone acquisition. Lang. Cogn. Neurosci. 2015, 30, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Potter, C.E.; Saffran, J.R. Plasticity in second language learning: The case of Mandarin tones. Lang. Learn. Dev. 2020, 16, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.-C. Second language perception of Mandarin vowels and tones. Lang. Speech 2018, 61, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.-C. Contextual effect in second language perception and production of Mandarin tones. Speech Commun. 2018, 97, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonessen, J.; Zellou, G. Perception of Mandarin tones across different phonological contexts by native and tone-naive listeners. In Proceedings of the Frontiers in Education, Washington, DC, USA, 13–16 October 2024; p. 1392022. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y.; Leung, K.K.; Jongman, A.; Sereno, J.A.; Wang, Y. Multi-modal cross-linguistic perception of Mandarin tones in clear speech. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1247811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, K.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Cai, H.; Li, L.; Wang, R. Production rather than observation: Comparison between the roles of embodiment and conceptual metaphor in L2 lexical tone learning. Learn. Instr. 2024, 92, 101905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farran, B.M.; Morett, L.M. Multimodal cues in L2 lexical tone acquisition: Current research and future directions. In Proceedings of the Frontiers in Education, Washington, DC, USA, 13–16 October 2024; p. 1410795. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, X. Processing Tone and Vowel Information in Mandarin: An Eye-Tracking Study of Contextual Effects on Speech Processing. Master’s Thesis, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Wagner, M. Effects of F0 feedback on the learning of Chinese tones by native speakers of English. In Proceedings of the Interspeech 2005, Lisbon, Portugal, 4–8 September 2005; pp. 181–184. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B. The gap between the perception and production of tones by American learners of Mandarin–An intralingual perspective. Chin. A Second Lang. Res. 2012, 1, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.A.; Toscano, J.C.; Shih, C.; Tanner, D. Reassessing the electrophysiological evidence for categorical perception of Mandarin lexical tone: ERP evidence from native and naïve non-native Mandarin listeners. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 2019, 81, 543–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Wang, W. Fusion Feature Based Automatic Mandarin Chinese Short Tone Classification. Technol. Acoust 2018, 37, 167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.-R.; Jung, T.-P.; Lin, C.-T.; Huang, K.-C.; Wei, C.-S.; Chiueh, H.; Hsin, Y.-L.; Liou, G.-T.; Wang, L.-C. Recognizing tonal and nontonal mandarin sentences for EEG-based brain–computer interface. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Dev. Syst. 2021, 14, 1666–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundararajan, M.; Taly, A.; Yan, Q. Axiomatic attribution for deep networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Sydney, Australia, 6–11 August 2017; pp. 3319–3328. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, K.K.; Wang, Y. Modelling Mandarin tone perception-production link through critical perceptual cues. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2024, 155, 1451–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Han, J.; Liu, Y.-L.; Feng, R.; Liang, X.; Ling, Z.-H.; Yuan, J. Decoding Speaker-Normalized Pitch from EEG for Mandarin Perception. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.19626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, S.; Lee, C.Y.; Tao, L. Statistical regularities affect the perception of second language speech: Evidence from adult classroom learners of Mandarin Chinese. Lang. Learn. 2019, 69, 527–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. English and Thai Speakers’ Perception of Mandarin Tones. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2016, 9, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Button, K.S.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Mokrysz, C.; Nosek, B.A.; Flint, J.; Robinson, E.S.; Munafò, M.R. Power failure: Why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013, 14, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakens, D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: A practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szucs, D.; Ioannidis, J.P. Empirical assessment of published effect sizes and power in the recent cognitive neuroscience and psychology literature. PLoS Biol. 2017, 15, e2000797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Guo, W.; Yang, H.; Lu, X.; He, Y.; Xu, H.; Kong, W. Evaluating Mandarin tone pronunciation accuracy for second language learners using a ResNet-based Siamese network. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wana, Z.; Hansen, J.H.; Xie, Y. A multi-view approach for Mandarin non-native mispronunciation verification. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2020—2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Virtual, 4–8 May 2020; pp. 8079–8083. [Google Scholar]

| Pass 1 Decision | Pass 2 Include | Pass 2 Exclude |

|---|---|---|

| Include | a (both include) | b (Pass 1 include; Pass 2 exclude) |

| Exclude | c (Pass 1 exclude; Pass 2 include) | d (both exclude) |

| Reference | Learners/Data | Modality/Method | Key Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [10] | L1 Eng. | ID training | Perception ↑, generalizes | Establishes perceptual plasticity |

| [61] | L1 Eng./Chi → Thai | ID/AX | T2–T3-like confusions | Pair-specific asymmetries |

| [27] | L1 Chi | EEG | TFS vs. ENV separation | Neural cue weighting |

| [62] | L1 Chi | EEG decoding | 4-tone decoding | Physiological validity |

| [63] | Corpus | RNN | Seq. tone dynamics | Strong non-sensor baseline |

| [64] | Corpus | CTC | End-to-end tones | No explicit F0 needed |

| [65] | Corpus | Short-term context | Coarticulation captured | Better sequences |

| [66] [67] | Corpus Tone Perfect corpus (isolated syllables) | SSL + CTC Unsupervised generative CNN (InfoGAN) | Suprasegmental SOTA Class variable ↔ tone (male-only best); Conv4/Conv3 encode F0; partial human-like order (T1/T4 > … > T2/T3) | Label-efficient Label-efficient + production-capable; bridge P ↔ P; add layer-probing to XAI |

| [68,69] | — | GCN/GAT | Relation learning | Basis for our D |

| [70,71,72] | — | XAI | Attribution/Counterfactual | Teachable diagnostics |

| Strand | Typical Inputs | Typical Outputs | Strengths | Limitations | Classroom Feasibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Perception and production tasks, controlled stimuli, learner responses | Tone labels, accuracy, reaction time, ratings, basic acoustic measures | Direct behavioral evidence and low cost; easy to replicate | Often label-focused; perception and production are not item-matched | High: adaptable to classroom and online settings |

| B | EEG or ERP and eye-tracking with audio stimuli; synchronized recordings | Time course indices, cue weighting, decoding or classification measures | Mechanistic insight into attention and timing; useful anchors for validation | Equipment and analysis burden; samples are often small | Low in classroom; mainly laboratory validation |

| C | Speech recordings; features such as F0, MFCC; self-supervised embeddings | Tone labels, confusion patterns, embeddings; sometimes parameter estimates | Scalable and sensor-free; strong baselines for automatic assessment | Often opaque; token-wise decisions can limit pedagogy and P ↔ P inference | Medium to high if packaged into teacher-facing tools |

| D | Speech features plus links across learner, item, and session; optional sensor anchors | Tone labels plus parameter-aligned targets; explanations and counterfactual edits | Uses corpus structure to support P ↔ P; delivers teachable, parameter-level feedback | Requires curated links, privacy safeguards, and robust evaluation; limited direct evidence in the current L2 Mandarin tone corpus | Emerging: feasible with tool engineering and fairness checks |

| Symbol | Meaning | Notes/Examples/Units | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nodes | L | Learner node | L1 background (tonal/non-tonal), proficiency, musicality |

| I | Item node | Syllable/word info, canonical tone, phonological/prosodic context | |

| R | Trial (response) node | One observation: a perception trial or a production recording | |

| Rperc | Perception trial | e.g., identification or same–different response for an item | |

| Rprod | Production trial | e.g., imitation or read-aloud recording | |

| S | Session node | Session index; task type (ID/AX/imitation/read-aloud); modality | |

| Relations (edges) | L ↔ R | Learner–trial link | Connects a learner to their trials |

| R ↔ I | Trial–item link | Connects a trial to its linguistic item | |

| Ri ↔ Rj|I | Within-item link | Repeated attempts on the same item across tasks/sessions | |

| Ri ↔ Rj|L | Within-learner link | Multiple trials from the same learner across tasks | |

| Rperc ↔ Rprod | Perception–production pair | Same learner and same item (P ↔ P coupling) | |

| kNN(R, R) | Acoustic/SSL neighbors | Links trials nearest in SSL embedding or prosodic feature space | |

| Outputs (predictions) | (R) | Predicted tone label | (1, 2, 3, 4); 1 = T1 (high level), 2 = T2 (rising), 3 = T3 (dipping/low), 4 = T4 (falling) |

| (R) | Slope | Rise/fall slope; semitones/s | |

| _TP(R) | Turning-point time | ms from rhyme onset (or stated anchor) | |

| _F0(R) | Local F0 range | semitones or Hz over a defined window | |

| Attribution window | TP ± 50 ms | Saliency window | Time window around the turning point used for attribution |

| Evaluation metrics | F1 (per-tone) | Classification metric | Report per-tone and macro F1 |

| RMSE_slope | Parameter error | RMSE for slope (semitones/s) | |

| Parameter error | Mean absolute error for TP timing (ms) |

| Metric | Target Output | Definition | Unit | Reporting | Pedagogical Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Tone label classification for perception and production | Proportion of items with correct predicted tone label | Unitless | Report overall for perception and production, include 95 percent confidence intervals | Overall correctness, useful for monitoring progress but not diagnostic of specific confusions |

| Per-tone F1 (F1_k) | Tone label classification for perception and production | Harmonic mean of precision and recall for each tone k | Unitless | Report F1 for each tone, highlight Tone 2 versus Tone 3 and Tone 1 versus Tone 4 | Identifies which tones are reliably produced or perceived and which are most often confused |

| Confusion matrix | Tone label classification for perception and production | Cross tabulation of predicted labels against gold labels | Counts | Report separately for perception and production, provide contrast focused summaries | Directly reveals error directions and supports targeted practice design |

| RMSE for slope | Continuous parameter estimation for production dynamics | Root mean squared error between predicted and reference slope | Semitones per second | Report per tone and per contrast, also report item level distributions | Quantifies mismatch in tonal movement strength, helpful for coaching contour shaping |

| MAE for turning point timing | Continuous parameter estimation for production dynamics | Mean absolute error between predicted and reference turning point timing relative to rhyme onset | Milliseconds | Report per tone and per contrast, also report item level distributions | Quantifies timing misalignment, maps directly to actionable feedback on earlier or later turning points |

| RMSE for local F0 range | Continuous parameter estimation for production dynamics | Root mean squared error between predicted and reference local fundamental frequency range | Hertz or semitones | Report per tone and per contrast, also report item level distributions | Quantifies pitch range compression or expansion, useful for diagnosing under articulation |

| Domain | Adequate n (%) | Partial n (%) | Unclear n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| B1 Participants/data | 23 (42.6) | 6 (11.1) | 25 (46.3) |

| B2 Task/stimuli | 24 (44.4) | 27 (50.0) | 3 (5.6) |

| B3 Measurement reliability/QA | 0 (0.0) | 18 (33.3) | 36 (66.7) |

| B4 Modelling/evaluation validity | 11 (20.4) | 22 (40.7) | 21 (38.9) |

| B5 Outcomes/metrics | 4 (7.4) | 27 (50.0) | 23 (42.6) |

| B6 Transparency/reproducibility | 8 (14.8) | 0 (0.0) | 46 (85.2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Huang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Bei, X.; Huang, H. Perception–Production of Second-Language Mandarin Tones Based on Interpretable Computational Methods: A Review. Mathematics 2026, 14, 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010145

Huang Y, Xu Z, Bei X, Huang H. Perception–Production of Second-Language Mandarin Tones Based on Interpretable Computational Methods: A Review. Mathematics. 2026; 14(1):145. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010145

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Yujiao, Zhaohong Xu, Xianming Bei, and Huakun Huang. 2026. "Perception–Production of Second-Language Mandarin Tones Based on Interpretable Computational Methods: A Review" Mathematics 14, no. 1: 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010145

APA StyleHuang, Y., Xu, Z., Bei, X., & Huang, H. (2026). Perception–Production of Second-Language Mandarin Tones Based on Interpretable Computational Methods: A Review. Mathematics, 14(1), 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010145