Abstract

This paper describes an approach for developing decision support systems (DSS) for strategic and tactical operating room (OR) planning and scheduling problems. These problems involve assigning amounts of time and specific time blocks in the ORs to surgical specialties and/or surgeons. A four-phase iterative software development lifecycle (SDLC) approach is used to develop a DSS that has a graphical user interface, a data management system, and optimization and simulation systems that incorporate mathematical programming models, solution methods, and discrete event simulation models. Results from the computational experience show that the plans generated by the DSS utilize at least 78% of the available OR time on average and use the downstream recovery ward (RW) beds in a balanced way that never exceeds the number of available beds.

Keywords:

operating room planning; decision support system; software development lifecycle; mathematical programming; hyperheuristics; discrete event simulation MSC:

90-10

1. Introduction

Because healthcare represents both a way to improve the wellbeing of people and a large portion of government spending in many countries, hospitals must utilize their physical resources, including operating rooms (ORs) and recovery ward (RW) beds, and human resources, such as surgeons, to provide surgeries to patients in a timely manner. Therefore, there is a need to develop better operations management and scheduling techniques to optimize the performance of surgical systems.

A three-phase hierarchy is commonly used to plan and schedule the ORs: strategic planning, tactical planning, and operational scheduling [1]. In the strategic phase, a planning horizon of one or more years is used (e.g., [2,3]). The case mix is determined by assigning amounts of time to surgical specialties and/or surgeons. In addition, long term decisions regarding physical resources, such as beds, are made. In the tactical phase, a planning horizon of one week to several weeks is used (e.g., [4,5]). Surgeons and/or surgical specialties are assigned to specific time blocks in the ORs. The utilization of downstream resources over the planning horizon can be balanced. Finally, in the operational phase, a planning horizon of one day to several days is used (e.g., [6,7]). Patients and all necessary resources are scheduled and sequenced. If a cancellation were to occur, then rescheduling could be performed.

Several different methods exist for the planning and scheduling of ORs. Mathematical programming is one of the most popular techniques for generating OR plans and schedules. Uncertainties associated with demand, surgical durations, patient lengths of stay (LOS) in the RW beds, and other factors can be accounted for using stochastic programming, robust optimization, analytical methods, or discrete event simulation (DES). In some cases, it is possible to apply exact solution methods to the mathematical programs to produce OR plans and schedules. However, it sometimes is necessary to use heuristics. In addition to mathematical programming, methods such as Markov chains, queuing theory, and simulation are used to create OR plans and schedules. Simulation, including DES, can also be used for creating visualizations and exploring the impact of changing parameter values. All of these methods can be difficult to use, and a healthcare worker might not have a background that is required to utilize them. A decision support system (DSS) can help workers generate and visualize OR plans and schedules.

In this paper, an approach for developing DSS is presented. After explaining the underlying mathematical modelling, an iterative software development lifecycle (SDLC) model is utilized. Although an iterative model has disadvantages, such as longer development cycles and less feedback from the customer, compared to other agile and hybrid models, it is flexible enough to handle changes to requirements, does not require constant communication with stakeholders or team members, and is able to manage risks. At the beginning of development in the iterative SDLC model, there is a system initiation phase. In this phase, the baseline problem and its scope are defined. In each subsequent iteration, the requirements, design, and construction of the system are analyzed. In the system requirements phase, a cause–effect analysis for the problem is performed. The system requirements are identified and prioritized. Use cases and actors are modelled. In addition, logical data flows are modelled and designed. In the system design phase, the logical data flows are used to design the physical data flows. Data structures and memory management are considered. In the system construction phase, the necessary components are designed. Applying these four phases of the SDLC model results in a DSS for OR planning and scheduling problems. The DSS focuses on the first two (strategic and tactical) phases of OR planning. The operational phase of OR scheduling could easily be added. In addition to a graphical user interface (GUI) system that the user interacts with and a data management system, there are two other systems in the DSS: an optimization system and a simulation system. These two systems incorporate mathematical programming models, exact and heuristic solution methods, and DES models developed in earlier papers [8,9,10]. These enable the generation and visualization of efficient OR plans.

1.1. Literature Review

Because this literature review specifically covers DSS for OR planning and scheduling problems, it is somewhat narrow in scope. Broader reviews of research related to these problems are available [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. After presenting a synthesis matrix of the relevant literature, the current state of the art is covered in more detail. A gaps and overlaps analysis is then performed.

1.1.1. Synthesis Matrix

Table 1 is a synthesis matrix for research related to DSS for OR planning and scheduling problems. A check mark (i.e., ✓) indicates that a factor is fully considered. For each paper, information about the modelling technique(s) (mathematical programming, simulation, and/or other), the phase(s) (strategic planning (SP), tactical planning (TP), and/or operational scheduling (OS)) and the type(s) of interface(s) (spreadsheet, desktop, web, and/or other) is provided.

Table 1.

Synthesis Matrix.

1.1.2. DSS for OR Planning and Scheduling

The underlying modelling in each DSS is classified as mathematical programming, simulation, or other. Mathematical programming is the most commonly used modelling method. Smid et al. [45] present an approach that is somewhat limited because it focuses more on statistics than optimization. Blake and Donald [29], Blake, Dexter, and Donald [30], Belien et al. [31], and Carter and Ketabi [36] present mathematical programming models that aim to create tactical plans that are nearly the same each week. This maximizes the preferences of surgical specialties and/or surgeons, because they typically prefer to work with surgeons belonging to the same specialty. In addition, it allows hospital managers to generate plans in a fair and unbiased manner, which can reduce conflicts with surgeons. However, a limitation is that there is a trade-off between making identical schedules and meeting strategic targets. In addition, because these models typically make assignments to surgical specialties, individual surgeons do not necessarily get assigned to the same ORs on the same days. Cardoen and Demeulemeester [33] use previous models [46,47] to sequence patients. Although this approach schedules outpatients, it ignores inpatients. van Essen et al. [35] propose a model for rescheduling cancelled surgeries. Dios et al. [39] propose a mixed-integer linear program that maximizes an indicator that considers both priorities of patients and waiting time targets set by the local authorities. Britt et al. [9] develop a stochastic weighted goal programming model. Although the model considers uncertainties associated with surgical durations and patient LOS, other uncertainties, such as demand, are ignored. Meliana et al. [43] develop a mixed-integer linear program that minimizes slot allocations during certain periods, such as morning and overtime. Anesthesiologists and anesthetic machines are considered in the model. This model is somewhat inflexible because it assumes that ORs are reserved for certain surgical specialties. Simulation is not as widely used as mathematical programming, but it still has several uses, including exploring the impact of uncertainties [9,10,41] and benchmarking [42]. Other modelling techniques, including predictive modelling [28], Markov chains [32,37], digital twins [44], and explainable artificial intelligence [48] are also used.

Each proposed DSS has some sort of interface that is categorized as either spreadsheet, desktop, web, or other. Blake and Donald [29], Blake, Dexter, and Donald [30], Carter and Ketabi [36], Penn et al. [40], Visintin et al. [41], Meliana et al. [43], and Britt et al. [9] develop spreadsheet-based DSS. Due to the ubiquity of Microsoft Excel, these DSS can be developed, deployed, and used fairly easily. However, there are limitations to spreadsheet-based DSS. Microsoft Excel spreadsheets and Visual Basic for Applications code do not work well with version control systems. This complicates development and makes it difficult to roll out updates. More importantly, interoperability with other healthcare applications might not be possible because packages supporting Health Level 7 (HL7) standards, which are used to transfer data between healthcare applications, are not necessarily compatible with spreadsheets. Belien et al. [31], Cardoen and Demeulemeester [33], Dios et al. [39], Clavel et al. [42], and Britt [10], use desktop programming languages, such as Visual C++ .NET, Java, or C#, to develop DSS. Because HL7 packages are available for most of these languages, these DSS can have the ability to interoperate with other information systems in the hospital. However, desktop interfaces still can have interoperability issues. Kusters and Groot [28] present a DSS that is standalone and does not interoperate with other information systems. Gomes et al. [34] and Sperandio et al. [38] propose web-based DSS that integrate with other hospital information systems using web services. Although these DSS do not have to be installed on a desktop computer, can be updated easier than desktop-based and especially spreadsheet-based DSS, and are portable, they have limitations and risks. Because they are not running locally, network access is required to use them, and there could be performance issues. In addition, because personally identifiable data are being sent over a network, there could be issues with privacy. Some interfaces fall under the other category. Because Tancrez et al. [32] and Tancrez et al. [37] do not provide full implementation details for their tool, it is difficult to evaluate advantages and disadvantages. Smid et al. [45] propose a MATLAB-based DSS that has interoperability issues and would have to be modified to handle data used in hospitals.

Each developed DSS ideally should be implemented in a hospital and then evaluated. Britt et al. [9] and Britt [10] use data to evaluate the performance of their DSS. Because these DSS are not actually implemented in a hospital, the presented experiments do not necessarily reflect how the system performs in real-world conditions. In general, a case study is a stronger way to evaluate a DSS. Case studies are conducted at hospitals in various countries, including Belgium [5,37], Canada [29,30], Egypt [48], France [44], Iran [43], the Netherlands [33], Portugal [34], and Spain [39,42]. A limitation of some real-world case studies is that they do not consider all surgical specialties at the hospital and instead focus on one or two specialties, such as orthopedics [28,42] or gynecology [28]. Visintin et al. [41] go beyond doing a case study. They use action research to study the implementation of a DSS for tactical planning. After considering and modifying three models, one is accepted. Results for a wide variety of key performance indicators from before and after the implementation of the DSS in Meyer University Children’s Hospital in Florence, Italy, are provided. The results show that their DSS improves the performance of both the ORs and the RW beds. However, limitations are that they do not consider the intensive care unit, electromedical devices, or anaesthetists.

1.1.3. Gaps and Overlaps Analysis and Contributions

The synthesis matrix presented in Table 1 and the review of the current state of the art show that many DSS for OR planning and scheduling problems already exist. There are three factors in the synthesis matrix: modelling, phases, and interfaces. By summarizing limitations of existing DSS, explaining the contributions of this paper, and analyzing each of the three factors in the synthesis matrix, context for these contributions are provided. Limitations of existing DSS include only using one modelling technique, only considering one phase, interoperability issues due to a lack of support of HL7 standards in spreadsheet-based DSS, and lacking the flexibility to be modified to overcome these limitations. This paper contributes a unified DSS framework for strategic and tactical OR planning that integrates mathematical programming models, exact and heuristic solution methods, discrete event simulation models, and an iterative SDLC model. For the modelling factor, there are large overlaps for mathematical programming and smaller gaps for the simulation and other methods. Aside for a few exceptions [32,37,44,48], all of the relevant papers use mathematical programming. In addition, approximately one quarter utilize simulation. For the phases factor, individual phases and combinations of two or more phases have to be considered when analyzing gaps and overlaps. When looking at individual phases, the strategic phase is only included in about one quarter of the relevant papers, and the tactical and operational phases are considered in approximately half of the papers. Aside for a few exceptions, all of the relevant papers only consider one phase. None of the papers include models for all three phases. For the interfaces factor, approximately half use a spreadsheet interface. About a third use a desktop interface. Only two have web interfaces. A few use other interfaces. None use two or more interfaces.

1.2. Paper Structure

This paper has the following structure. Section 2 provides an overview of the underlying mathematical modelling used in the DSS. In addition, the phases of the SDLC, including system initiation, system requirements, system design, and system construction are covered. Section 3 applies the DSS to some data in order to obtain computational results. Finally, Section 4 contains conclusions and future work.

2. Materials and Methods

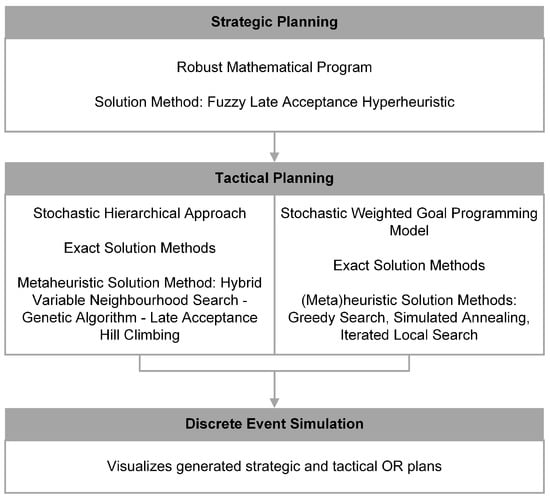

The DSS proposed in this paper utilizes mathematical programs, solution methods, and DES models presented in three earlier publications [8,9,10]. Figure 1 is an overview of these methods. This section provides the details of the underlying mathematical modelling used in the DSS. In addition, the SDLC approach used to design the DSS is explained.

Figure 1.

Overview of Methodology.

2.1. Underlying Mathematical Modelling

After listing the notation in a series of tables, the objective functions and constraints for the strategic planning (SP) model, hierarchical models (HM), and weighted goal programming model (WGPM) are given [8,9,10].

2.1.1. Notation

Index sets for all three models are presented in Table 2. Parameters and variables are presented in Table 3 and Table 4, respectively.

Table 2.

Index Sets.

Table 3.

Parameters.

Table 4.

Variables.

2.1.2. Strategic Programming (SP) Model

Britt et al. [10] considers both strategic and tactical OR planning. Equations (1)–(9) are a mathematical representation of the model used in the strategic phase. For this phase, a mathematical program that maximizes the total benefit of performing surgeries is proposed. Physical resources, such as RW beds, are considered. Robust optimization is used to account for uncertainties in surgical durations. In particular, constraints (5) were derived using an approach that allows for the efficient use of lognormally distributed surgical durations. For tactical planning, two existing mathematical programs from the other two articles are used [8,9]. A fuzzy late acceptance hyperheuristic is used to produce both strategic and tactical OR plans [49,50,51].

Subject to:

Objective function (1) optimizes total benefit. Constraints (2) and (3) assign RW beds and manage the RW census, respectively. Constraints (4) and (5) assign time blocks and manage time in the ORs, respectively. Constraints (6) ensure that patient admissions fall between bounds. Constraints (7)–(9) define variables.

2.1.3. Hierarchical Models (HM)

Britt et al. [8] present a hierarchical approach for tactical planning that consists of a series of seven mathematical programs, which are represented by Equations (10)–(78). They satisfy waiting time targets, minimize deviations between the actual and target number of patients, maximize OR utilization, minimize variations in surgeon assignments for both weekdays and ORs, minimize the total number of expected patients in the RW, and minimize variations in the RW utilization. Stochastic programming is used to consider uncertainties in surgical durations and patient LOS.

Some of the mathematical programs are solved with exact solution methods. For the final mathematical program, a hybrid variable neighbourhood search-genetic algorithm that utilizes a late acceptance hill climbing heuristic is used to generate tactical OR plans [52,53].

Hierarchical Models Problem 1A—Choosing the OR Service Level

Subject to:

Objective function (10) optimizes the OR service level. Constraint (11) and (12) limit the number of service levels that can be chosen and the number of time blocks that can be assigned, respectively. Constraints (13) define variables.

Hierarchical Models Problem 1B—Assigning Time Blocks to Surgeons

Subject to:

Objective functions (14)–(16) are three different alternatives for minimizing deviations with respect to strategic targets. Constraints (17) align the decisions in problem 1B with the ones made in problem 1A. Constraint (18) assign all available time blocks. Constraints (19) involve strategic targets. Constraints (20)–(22) define variables.

Hierarchical Models Problem 2—Assigning Time in the ORs to Surgeons

Subject to:

Objective function (23) optimizes OR utilization. Constraints (24) define OR underutilizations. Constraints (25)–(27) define variables.

Hierarchical Models Problem 3A—Assigning Resources to ORs

Subject to:

Objective functions (28)–(30) are three different alternatives for minimizing variations in assignments of resources. In the encoding scheme , a digit equals one if the corresponding variable (, , ) is used in the objective function and otherwise equals zero. Constraints (31) satisfy machine requirements. Constraints (17) align the decisions in problem 3A with the ones made in problem 1B. Constraints (33) assign available time blocks. Constraints (34) define whether ORs are open (i.e., on weekdays) or closed (i.e., on weekends and holidays). Constraints (35) align variables. Constraints (36)–(40) define variables.

Hierarchical Models Problem 3B—Assigning Resources to Weekdays

Subject to: Constraints (31) to (35)

For encodings 100, 101, 110, and 111:

For encodings 010, 011, 110, and 111:

For encodings 001, 011, 101, and 111:

Objective function (41) minimizes variations in assignments of weekdays. Constraints (31)–(35) align the decisions in problem 3B with the ones made in problem 3A. Constraints (42)–(44) align variables. Constraints (45) and (46) assign surgeons. Constraints (47)–(54) define variables.

Hierarchical Models Problem 4—Distributing Time Blocks Evenly to Surgeons

Subject to:

Objective function (55) optimizes the RW census. Constraints (56)–(59) align the decisions in problem 4 with the ones made in problem 3B. Constraints (60) evenly distribute time blocks to surgeons. Constraints (61) determine the RW census. Constraints (62)–(64) define variables.

Hierarchical Models Problem 5—Swapping to Balance Utilization of RW Beds

Subject to:

2.1.4. Weighted Goal Programming Model (WGPM)

Britt et al. [9] develop a stochastic WGPM, which is represented by Equations (79)–(89). In addition to exact solution methods, a greedy search heuristic and simulated annealing and iterated local search metaheuristics are used to produce tactical OR plans [54,55,56]. A DES model is used to visualize the generated plans.

Subject to:

Objective function (79) minimizes the sum of four goals: the deviations between the targeted and actual number of surgeries performed, the deviations between the targeted and actual number of hours for surgeries, the maximum expected number of patients in the RW, and the difference between the maximum and minimum expected number of patients in the RW. Constraints (80) and (81) respect surgeons’ preferences to not be assigned to certain ORs or days, respectively. Constraints (82) and (83) limit assignments of surgeons to time blocks. Constraints (84), (85), and (88) involve strategic targets. Constraints (86) define OR utilization. Constraints (87) and (89) define variables. Furthermore, objective function (79) and constraints (85)–(87) use a scenario-based stochastic programming approach to account for uncertainties in surgical durations and patient LOS.

2.2. System Development Lifecycle Approach for Designing the Decision Support System

A four-phase iterative system development lifecycle (SDLC) model is used to design the DSS. The phases are system initiation, system requirements, system design, and system construction.

2.2.1. System Initiation

The first of the four phases in the SDLC is system initiation. In this phase, the baseline problem and its scope are defined. Next, if the DSS is determined to have a higher urgency than other projects, then the schedule and budget are determined. This section focuses on the baseline problem and scope.

Baseline Problem

Table 5 is a problem statement matrix that outlines the baseline problem being considered. It has three sections. The first section shows the names of the project and the project manager. The second section shows when the problem statement matrix was created, the person who last updated it, and the date on which the last update was made. The third section shows details, including urgency, visibility, rank, and proposed solution, for each problem. In this case, the key problem is that ORs and RW beds in the hospital currently are not being used efficiently. Uncertainties associated with surgical durations and patient LOS are believed to be related to this problem. Because this is the only problem, it has the highest possible urgency, visibility, and rank. The proposed solution is to develop a new DSS.

Table 5.

Problem Statement Matrix.

Baseline Scope

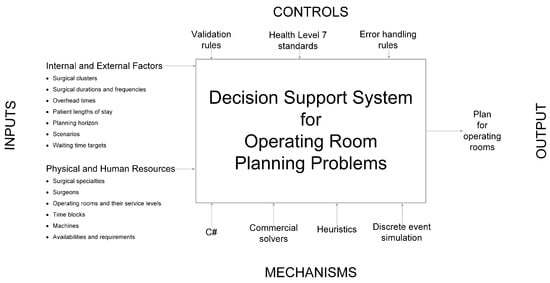

Figure 2 is an Integrated DEFinition 0 (IDEF0) diagram for the DSS. It represents the baseline scope by showing the inputs, controls, and mechanisms used to generate the output.

Figure 2.

IDEF0 Diagram.

The inputs consist of the data that are required to generate and visualize strategic and tactical OR plans. The data include information about human resources, including surgeons and surgical specialties, and physical resources, including ORs, RW beds, and machines. The data also include information about which clusters of surgeries are performed by surgeons, the durations, frequencies, and overhead times of those surgeries, and patient LOS in the RW beds after they are operated on. In addition, the data include information about other factors, including the planning horizon, service levels, scenarios, time blocks, resource availabilities and requirements, and waiting time targets.

The system contains several controls. It has rules for validating data and handling errors. More importantly, other controls exist in order to allow for interoperability with other hospital information systems. In particular, input and output data follow the Health Level 7 (HL7) Fast Health Interoperability Resources (FHIR) specification. Data within the system also follow the HL7 FHIR specification as much as possible. Following this specification allows for interoperability with other hospital information systems. Because HL7 FHIR has mappings to earlier HL7 standards, such as HL7 v2 and especially HL7 v3, interoperability with older hospital information systems is possible. However, interoperability with information systems not following the HL7 standards might be problematic.

The system also has several mechanisms. The C# programming language is used to code the DSS. The system uses commercial solvers and heuristics to generate OR plans. These can then be visualized using DES.

The primary outputs from the system are the generated strategic and tactical OR plans. Performance measures are used to evaluate the generated OR plans. For both strategic and tactical OR plans, the number of patients is a key performance measure. For strategic OR plans, performance measures include the total benefit and RW bed assignments. For tactical OR plans, performance measures include OR underutilization (ORUU) and RW censuses. Key objectives are reducing the amount of ORUU and improving the utilization of RW beds.

2.2.2. System Requirements

The second phase involves considering the requirements of the system. After analyzing the cause and effects associated with the problem, the system requirements are identified and prioritized. Use case models that take relevant actors into account are then developed. Finally, the logical data flows and designs are explained.

Problem Analysis

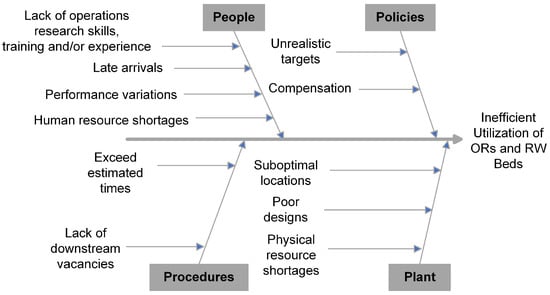

Cause and effect analysis is applied to the system of ORs and RW beds. Figure 3 is the corresponding Ishikawa diagram.

Figure 3.

Ishikawa Diagram.

Potential causes are classified into four categories that all start with the letter P: people, policies, procedures, and plant.

In the people category, several different groups could be responsible: hospital managers, OR planners, patients, surgeons, and other workers at the hospital. Hospital managers and OR planners may not have training and/or experience in operations research. This could prevent them from properly utilizing mathematical programming, solution methods, and DES models to generate and visualize OR plans and schedules. Patients could arrive late, which could delay surgery start times. There could be performance variations between surgeons. This could be problematic if OR plans and schedules were generated with the assumption that all surgeons perform equally well. Shortages of human resources, including hospital managers, OR planners, surgeons, and other workers at the hospital, could also cause performance issues in the hospital.

In the policies category, there are two potential causes. Firstly, targets for waiting times, number of patients, and number of hours for surgeries might be unrealistic. This would result in the creation of plans and schedules that do not use the ORs and RW beds efficiently. Secondly, surgeons in some jurisdictions get extra compensation if they perform surgeries after certain times on weekdays and at any times on weekends. These compensation policies could prevent the ORs from being used at night and on weekends.

In the procedures category, there also are two potential causes. Firstly, each procedure has an estimated time, but actual procedure times could exceed these estimated times. This could delay subsequent surgeries. Secondly, there could be a lack of vacancies in downstream units, including RW beds. This could cause surgeries to be cancelled or delayed.

Finally, in the plant category, there are three potential causes. Firstly, machines required for surgeries could be assigned to suboptimal locations. Secondly, ORs could be designed poorly. This could cause surgeries to have longer durations. Finally, there could be shortages of physical resources, including ORs and RW beds. This could prevent surgeries from happening.

The effect of these potential causes is that resources in the hospital, including ORs and RW beds, are not used efficiently.

Prioritization of System Requirements

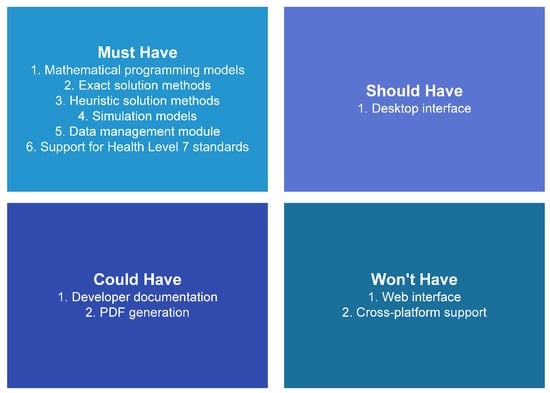

As shown in Figure 4, MoSCoW analysis (must have, should have, could have, and will not have) is used to prioritize the requirements of the system.

Figure 4.

MoSCoW Analysis.

In the must have category, there are several requirements. Firstly, the system must have mathematical programs that generate strategic and tactical OR plans. Secondly, the system must have exact and heuristic solution methods in order to obtain solutions to these mathematical programs. Thirdly, it must have simulation models that visualize the generated plans. Next, the system must have a data management module that allows the user to create, read, update, and delete information. Finally, the system must have support for HL7 standards in order to allow for interoperability with other information systems in the hospital.

In the should have category, there is one requirement. The system should have a desktop interface that allows the user to easily utilize the mathematical programs, solution methods, and DES models.

In the could have category, there are two requirements. Firstly, there could be development documentation that explains how the underlying code works. This is low priority because the development team is small. Secondly, the system could have the ability to generate PDF versions of the generated OR plans. Because open source PDF generation packages only seem to work with older versions of .NET, this feature is low priority.

In the will not have category, there are two requirements. Firstly, a web interface would allow the system to be used from any networked location, but the system will only have a desktop interface. Because the DSS handles healthcare-related data, a web interface would introduce too many privacy risks. Secondly, there could be cross-platform (Windows, Linux, MacOS) support, but the system will only work on Windows. Although .NET has some cross-platform support, most of the available desktop interfaces are designed for Windows.

Actors

The system is used by and interacts with different actors. The four key actors are hospital management, an OR planner, surgical specialties, and surgeons. The entire hospital, including the ORs and downstream RW beds, is managed by a team. The OR planner uses the DSS to generate OR plans. A surgical specialty is a collection of surgeons who perform the same types of surgeries. Each surgeon belongs to a surgical specialty and uses the ORs to perform surgeries on patients.

Use Case Modelling

The system has four use cases:

- Manage data: As shown in Figure 2, input data are required to generate OR plans. In this use case, the data are created, read, updated, and/or deleted.

- Exact solution: This use case involves using an exact solution method to generate an OR plan.

- Heuristic solution: This instead generates an OR plan using a heuristic solution method.

- Simulation: In this use case, a generated OR plan is visualized using DES.

In addition, there are four roles: primary system actor, primary business actor, external receiver actor, and external server actor. Primary system actors directly interact with and provide inputs to the system. Primary business actors directly benefit from outputs of the system. External receiver actors do not directly interact with the system but receive some benefit from outputs of the system. External server actors provide information to the system.

Table 6 provides relationships between the use cases, actors, and roles. In all four use cases, the OR Planner actor interacts with the system directly and is the primary system actor.

Table 6.

Use Cases.

For the manage data use case, the OR Planner actor uses the system to create, read, update, and/or delete data. Because the Hospital Management actor may be required to submit data to government or other external entities, they are the primary business actor in this use case.

For the exact and heuristic solution use cases, the OR planner uses the system to generate an OR plan. The details of that plan are then sent to the external receiver actors. These are the surgeons and the surgical specialties to which they belong.

For the simulation use case, the OR plan is visualized for the OR Planning Actor.

Logical Data Flow Diagrams and Design

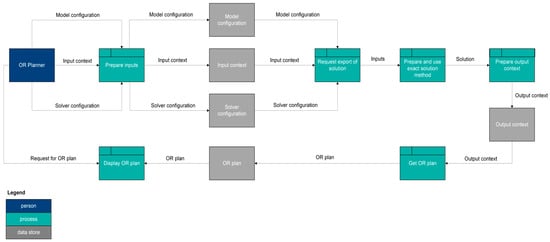

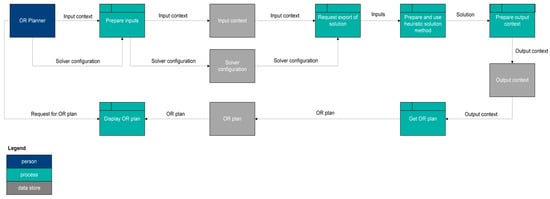

Figure 5 and Figure 6 are logical data flow diagrams for using exact and heuristic solution methods, respectively, to generate OR plans.

Figure 5.

Logical Data Flow Diagram—Exact Solution Method.

Figure 6.

Logical Data Flow Diagram—Heuristic Solution Method.

For an exact solution method, the OR Planner actor provides the input preparation process an input context that contains the required input data and configurations for the model and commercial solver. The input context and two configurations are placed in their associated data stores. These three things then enter a process that requests a solution to be exported. Next, these inputs go to a process that prepares and uses an exact solution method. An output context preparation process then takes this solution and converts it into an output context, which is placed in its associated data store. A subsequent process then gets the OR plan and places it in its associated data store. The OR Planner actor then interacts with a process that displays the OR plan. This process obtains the generated OR plan from the relevant data store.

For a heuristic solution method, the logical data flows are almost exactly the same as the ones for an exact solution method. The difference is that a heuristic solution method does not need a model configuration.

2.2.3. System Design

The third phase of the SDLC approach is related to the design of the system. This design is documented by diagramming and explaining the physical data flows. In addition, data structures and memory management are discussed.

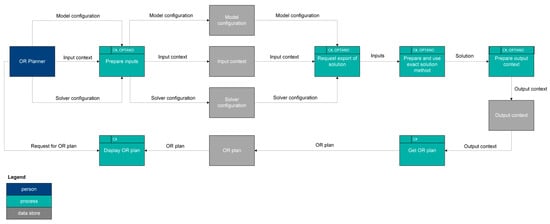

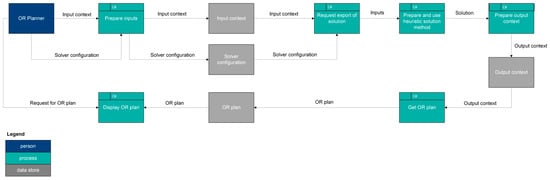

Physical Data Flow Diagrams and Design

Figure 7 and Figure 8 are physical data flow diagrams for using exact and heuristic solution methods, respectively, to create OR plans. The physical data flows are similar to the logical data flows presented in Figure 5 and Figure 6.

Figure 7.

Physical Data Flow Diagram—Exact Solution Method.

Figure 8.

Physical Data Flow Diagram—Heuristic Solution Method.

For exact and heuristic solution methods, all of the processes use C#. In order to allow for interoperability with other information systems in the hospital, the HL7 FHIR specification is used in the input and output contexts and as much as possible in the other processes and data stores. In addition, for an exact solution method, the prepare inputs, request export of solution, prepare and use exact solution method, and prepare output context use the OPTANO mathematical programming application programming interface (API).

Data Structures and Memory Management

The IDEF0 diagram (Figure 2) shows the inputs, controls, and mechanisms that are used when generating the output. The data inputted to the DSS, used internally within the DSS, and outputted from the DSS can be quite large. Therefore, it is important to use data structures and memory management techniques that account for the time and space complexities.

In the initial development iteration, managed linear lists were used to store nearly all of the data. These worked well for small instances but performed poorly for larger instances. In subsequent iterations, the managed linear lists were largely replaced by spans and red-black trees.

A span is a continuous region of memory. The memory is allocated on the stack, not the managed heap. Because the memory is not managed, it has to be manually allocated and freed. Unlike managed linear lists, bounds checks and similar operations have to be performed manually. Using spans instead of managed linear lists resulted in performance improvements.

Because some of the necessary data cannot be stored in spans, some of the managed linear lists were replaced with managed red-black trees. A red-black tree has a space complexity of and a worst case time complexity of for search, insertion, and deletion. This allows managed red-black trees to scale better than managed linear lists. Therefore, replacing managed linear lists with managed red-black trees resulted in performance improvements, especially for larger instances.

2.2.4. System Construction

The fourth and final phase involves the construction of the system. In this section, the hierarchical diagramming model is first explained. Next, relevant diagrams from each level are provided. Finally, the core code components of the simulation system are explained.

Hierarchical Diagramming Model

A C4-like model, which has diagrams that are organized in a four-level hierarchy (context, container, component, and code) is used to document the construction of the DSS. The C4-like diagrams are from the perspective of the OR Planner actor.

In the code level of the hierarchy, the diagrams include unified modeling language (UML) class and sequence diagrams. The DSS includes a tool that automatically generates these diagrams from the source code. When the C# code is compiled, the Roslyn compiler generates an abstract syntax tree (AST). The diagram generation tool walks through the AST and identifies classes, methods, properties, calls to methods, and similar features. These are used to generate PlantUML code, which is then converted into UML diagrams.

C4-Like Diagrams and Construction of System

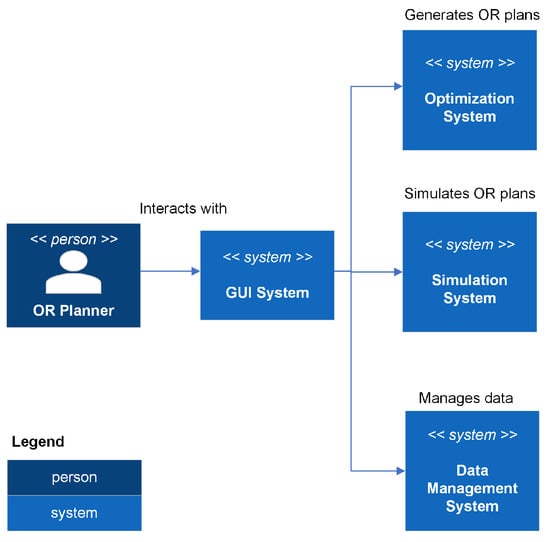

Figure 9 is a context diagram for the DSS. In addition to the GUI system that the OR Planner interacts with and a data management system, there are two other systems in the DSS: an optimization system and a simulation system. The optimization system contains exact and heuristic solution methods that solve mathematical programming models in order to generate OR plans. The simulation system enables the visualization of the generated OR plans.

Figure 9.

Context Diagram.

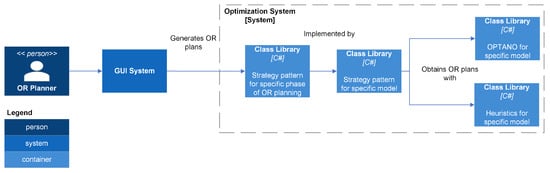

Figure 10 is a container diagram for the optimization system. For each specific phase of OR planning, there is an associated strategy pattern. For a given phase (e.g., strategic planning or tactical planning), one or more different mathematical models can be used to generate OR plans. For each model, there is a corresponding strategy pattern. A solution for a specific model can be obtained using either an exact (using the OPTANO mathematical programming API) or a heuristic solution method.

Figure 10.

Optimization Container Diagram.

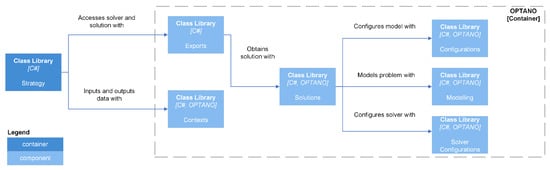

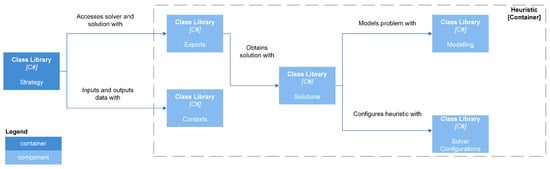

Figure 11 and Figure 12 are component diagrams for exact and heuristic, respectively, solution methods. Each exact and heuristic solution method has an export class that accepts an input context containing data related to the OR planning problem and a solver configuration containing parameters used by the solver. In addition, the export class for an exact solution method requires a configuration for the OPTANO model. The export class creates a solution class, which generates a model and solves it, and then returns an output context that contains the OR plan.

Figure 11.

OPTANO Component Diagram.

Figure 12.

Heuristic Component Diagram.

Several different heuristic solution methods, including simulated annealing and iterated local search, are used [54,55,56]. In addition, two of the newer heuristics implemented are a hybrid variable neighbourhood search-genetic algorithm heuristic and a fuzzy late acceptance hyperheuristic; both utilize late acceptance [49,50,51,52,53].

BeVelS is a framework that allows the DSS to have a fully integrated simulation package. The name of the framework is derived from the names of the physics (BepuPhysics2), graphics (Veldrid), and simulation (Sage) packages.

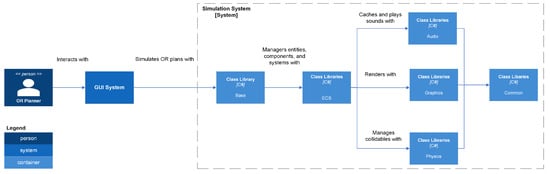

Figure 13 represents the container diagram for the simulation system. This container allows for the visualization of generated OR plans. An entity-component system (ECS) architecture is used to manage common components as well as the audio, graphics, and physics components.

Figure 13.

Simulation Container Diagram.

Common

The Common namespace contains code that is used in one or more of the other BeVelS namespaces. It has the following namespaces: Comparers, Matrices, Meshes, OrthonormalBasisBuilders, Parallelism, Stopwatches, Threading, Threading.Windows, Triangles, Utilities, and Vectors.

Comparers has classes that enable comparing pairs of instances.

Vectors and matrices are used throughout BeVelS. Relevant supporting code can be found in the Matrices and Vectors namespaces. The Matrices namespace has an extension method that can be used to find the inverse of a Matrix4x4. In the Vectors namespace, there is an extension method that converts a Vector2 to a BepuUtilities.Int2. The Vectors namespace also has factories that create Vector2, Vector3, and Vector4 instances.

The Triangles namespace uses the struct TriangleContent to define a triangle in terms of three Vector3 instances. The Meshes namespace has a class named MeshContent that defines a mesh in terms of an array of TriangleContent instances.

The OrthonormalBasisBuilders namespace is related to the building of orthonormal bases. In particular, Duff2017OrthonormalBasisBuilder implements the approach developed by Duff et al. [57].

The Parallelism namespace has a ParallelLooper class that implements a parallel for loop.

The Stopwatches namespace involves high precision profiling. Stopwatch is an implementation of a stopwatch that is similar to System.Diagnostics.Stopwatch. It obtains timestamp and frequency values by using P/Invoke to call the QueryPerformanceCounter and QueryPerformanceFrequency, respectively, functions in profileapi.h. In addition, there is a related StopWatchState class that keeps track of the state of a stopwatch.

The Threading and Threading.Windows namespaces contain code related to managing threads and tasks. The Threading namespace has a heuristic that uses Environment.ProcessorCount to estimate a thread count. Threading also has utility classes and factories related to Task Parallel Library tasks and the thread dispatcher in BepuUtilities. For example, CancellableTask is a wrapper that has two properties (a Task and a CancellationTokenSource) and a method for cancelling the task. The Threading.Windows namespace has an extension method that allows a task to be invoked asynchronously using a System.Windows.Threading.Dispatcher instance.

The Utilities namespace contains several helper classes. DisposeUtilities has code related to the IDisposable interface. IndexUtilities has methods that generate box and quad indices. QuaternionUtilities can pack a Quaternion into a Vector3 or ulong. SpanUtilities can convert a buffer into a span.

Audio

The Audio namespace uses NAudio, which is a C# audio library, and code based on the NAudio.Extras package to provide audio functionality to BeVelS. Audio has the following namespaces: Caching, Channels, Devices.Windows, Mixers, PlaybackEngines, Players, Readers, and Resamplers.

The Channels, Mixers, and Resamplers namespaces have factories that create ISampleProvider instances, including MonoToStereoSampleProvider, MixingSampleProvider, and WdlResamplingSampleProvider. The Players namespace has a factory for creating WaveOutEvent instances.

The Devices.Windows namespace has a class that uses WaveInterop in NAudio to get the number of available wave out devices.

The Readers namespace uses AutoDisposeAudioFileReader to read audio files. After reading an audio file, classes in the Caching namespace are used to store audio data as arrays of floats. The PlaybackEngine namespace uses AudioPlaybackEngine16 to manage the playback of cached audio files.

Graphics

Veldrid is a C# graphics library that is available under the MIT license. Veldrid is a common frontend for several different backends, including DirectX, Metal, OpenGL, OpenGLES and Vulkan. In BeVelS, Veldrid is used to provide graphics functionality. Code related to this is under the Graphics namespace. Some namespaces under Graphics only have wrapper classes, extension methods, and/or factories for Veldrid objects: BlendStates, CommandLists, Debugging, DepthStencilStates, Framebuffers, GraphicsDevices, GraphicsPipelines, RasterizerStates, ResourceLayouts, ResourceSets, Samplers, ShaderSets, Shaders, Swapchains, VertexLayouts, and Viewports.

In addition, the following namespaces are under Graphics: BackgroundRenderers, BufferConstants, Buffers, Cameras, Fonts, Glyphs, HTML, Images, KTX, LineRenderers, Meshes, PostProcessors, Recorders, ShapeRenderers, Shapes, Text, Textures, UILines, UIRenderers, and Utilities.

Code related to managing images falls under the Images namespace. There are classes for loading an image from a file into a renderable format, storing a collection of renderable images, and batching images.

The Meshes namespace has code for working with meshes. The MeshBuilder class uses dependencies, including AssimpNet, to load a mesh from a file. The MeshCache class is used for caching meshes during rendering.

Text-related code falls under the Fonts and Text namespaces. The Fonts namespace has structs that define character data, character pairs, and glyph sources. In addition, there are classes for batching glyphs, building a font, packing a font, storing the content of a font, and loading a font as a Veldrid Texture. The Text namespace has a class that uses the builder pattern for text.

In a shader, data can be uploaded to a graphics card using several different objects, including buffers, samplers, or textures. The Buffers, BufferConstants, Glyphs, HTML, Images, Shapes, and UILines namespaces and BeVelS.Physics.Constraints have code related to buffers and the data that can be uploaded to them. The Buffers namespace has four types of buffers: Constants, Index, Instances, and ShapeInstances. The BufferConstants namespace has structs that are used to upload data to constants buffers in vertex and fragment shaders. The data for index buffers are generated using relevant methods.

The Glyphs, HTML, Images, BeVelS.Physics.Constraints, and UILines namespaces have structs for uploading data to instances buffers. The Shapes namespace has structs associated with uploading data to shape instances buffers.

The Samplers namespace provides factories that can generate sampler instances. Code related to textures is under the KTX and Textures namespaces. The KTX namespace has code for loading a Khronos Texture as a Veldrid Texture. The Textures namespace has a TextureContent class that is used when loading other texture content, such as a font or an image, as a Veldrid Texture.

Renderers are divided into four categories: background, shapes and lines, screenspace, and post processors. A background renderer draws an image behind all other rendered items. Shapes and lines renderers draw shapes, such as boxes and cylinders, and lines, which are associated with constraints. Screenspace renderers draw UI elements, such as glyphs and images. The CompressToSwap post processor combines the outputs of the background, shapes and lines, and screenspace renderers and draws the combined image on the main swapchain.

The Cameras namespace contains code related to viewing renderings. It contains a class that defines a three-dimensional camera.

The Recorders namespace contains code associated with recording and saving renderings. The FrameRecorder class grabs the underlying texture of a rendering and copies it to a staging texture. The content of the staging texture is then copied to an image. The AnimatedGifRecorder class collects saved frames and uses them to form an animated image.

The Utilities namespace has a utility class for working with colours. It has PackColor methods that can pack a Vector3 or Vector4 colour into an uint. It has similar UnpackColor methods that can unpack an uint colour into a Vector3 or Vector4.

Physics

BepuPhysics2 is an open source C# physics library for rigid-body dynamics. BepuPhysics2 has several constrainable collidables, whose collisions can be detected.

Collidables are defined in the BepuPhysics.Collidables namespace. CollidableDescription and CollidableReference are used to describe and reference, respectively, collidables. A collidable generally implements either the IConvexShape or ICompoundShape interface, both of which implement the IShape interface. Most of the collidables, including Box, Capsule, ConvexHull, Cylinder, Sphere, and Triangle, are convex shapes that implement the IConvexShape interface. Mesh is a homogeneous compound of triangles. Heterogeneous compounds can be defined using BigCompound and Compound and associated helper classes.

The BepuPhysics.Constraints namespace contains code related to more than a dozen constraints. In addition, some classes related to constraints, including ConstraintBatch, ConstraintLocation, ConstraintReference, and ConstraintSet, are in the BepuPhysics namespace.

BepuPhysics2 is used to provide physics functionality to BeVelS. Code relevant to this falls under BeVelS.Physics. The base BeVelS.Physics namespace has factories for generating instances of various classes that fall under the base BepuPhysics namespace. In addition, BeVelS.Physics has the following namespaces: Callbacks, Collidables, Constraints, Meshes, and TimeSteps.

The Callbacks namespace has two callback structs. One struct is related to the narrow phase of collision detection. This struct has properties related to the contact springiness, maximum recovery velocity, and friction coefficient. It also has methods related to configuring contact manifolds and determining whether contact generation is allowed. The other is related to the pose integrator. It contains code related to gravity, linear and angular damping, and linear and angular velocities.

The Collidables namespace contains code related to collidables. There are factories that can generate Box, Capsule, ConvexHull, Cylinder, Mesh, Sphere, and Triangle instances. There also are factories for creating CollidableDescription and CollidableReference instances. In addition, there is an extension method that can add a collidable to a BepuPhysics2 simulation.

The Constraints namespace has classes and structs for extracting constraint lines and factories for creating instances of specific constraints

The Meshes namespace has utility classes and factories related to meshes. MeshHelper is used to load a mesh. The factories can generate different meshes, including deformed planes and fans.

The TimeSteps namespace has classes, which support fixed and variable timesteps, that can be used in conjunction with the Timestep method in a BepuPhysics2 simulation.

Entity Component System Architecture

DefaultEcs is used to allow BeVelS to have an Entity Component System (ECS) architecture. In this architecture, there are five primary types of objects:

- Entity: An object that has a unique identifier.

- Component: A wrapper struct that only contains data.

- System: A class that implements the ISystem<T> interface and has business logic that acts on entities.

- World: Each entity belongs to a world.

- Message: A struct that can transfer data in a world using a publish/subscribe pattern.

In Table 7, a ✓ is used to indicate the existence of a component, message, or system in BeVelS.

Table 7.

Key ECS Objects in BeVelS.

3. Results

The DSS developed using the proposed approach incorporates mathematical programming models, exact and heuristic solution methods, and DES models. All of these have already been evaluated in earlier papers [8,9,10]. Therefore, this computational experience aims to present results for a small case.

3.1. Data and Code Repository

An Open Science Foundation repository containing relevant data and code is available at https://osf.io/j4ehx/ (accessed on 30 October 2025).

3.2. Data

Published data are used to generate fictional data for this case. Assumed values are used when data are not available.

Scenario 1 in the case study conducted by Li et al. [58] is the main source of published data. There are 8 h in a time block [58,59]. The fictional hospital has 30 surgeons, 9 ORs, and 6 surgical specialties [58]. Table 8 shows how these surgeons are assigned to surgical specialties [58].

Table 8.

Assignments of Surgeons to Surgical Specialties [Adapted from Li et al. [58]].

It is assumed that there are 120 RW beds.

In the strategic phase, it is assumed that every surgical cluster, regardless of surgeon, has a benefit of 10.

A planning horizon that starts on 1 May 2023 is used. In the strategic phase, the planning horizon has a length of 365 days [60,61,62]. In the tactical phase, the length is 28 days [58]. The strategic and tactical phases have 261 and 20 active days, respectively.

Surgical durations, frequencies, and LOS are generated from published data [63,64]. Overhead times are assumed to follow the uniform distribution .

In the strategic phase, four values of are used: two published values (0.7 and 0.9) and two assumed values (0.5 and 1.0) [65]. As decreases, increases. Because is used in constraints (5), the value of may impact those constraints. In the tactical phase, 16 scenarios are used to account for uncertainties associated with surgical durations and patient LOS.

The following performance measures are used for evaluation:

- Total benefit (Strategic phase).

- Number of patients (Strategic and tactical phases).

- RW bed assignments (Strategic phase).

- ORUU (Tactical phase).

- RW censuses (Tactical phase).

3.3. Evaluation of Decision Support System

The OR planner actor using the DSS must choose a value for . The value of , the uncertainty budget parameter, depends on . More specifically, increases as decreases. The appropriate level depends on how conservative the OR planner actor is with respect to uncertainties associated with surgical durations. This generally depends on the costs incurred when surgical durations fluctuate, such as undertime or overtime costs. If these costs are low, then the OR planner actor can use a higher level, such as 1.0 or 0.9. However, if these costs are high, then the OR planner actor can use a lower level, such as 0.7 or 0.5. To assist the OR planner actor in choosing an level, the results for four levels (0.5, 0.7, 0.9, and 1.0) are presented and analyzed to examine trends that occur as changes.

Table 9 shows the total benefit of performing surgeries in the strategic phase. Because each surgery is assumed to have a benefit of 10, the total benefit for each level is the number of patients scheduled in the strategic phase multiplied by 10.

Table 9.

Benefit (Strategic Phase).

Table 10 and Table 11 show the number of patients scheduled in the strategic and tactical phases, respectively. In the strategic phase, is used in constraints (5). A smaller level and thus a larger value means that fewer patients can be scheduled. The results in Table 10 confirm that this trend holds in the strategic phase. The number of scheduled patients increases from 3512 () to 6330 (). However, the results for the tactical phase in Table 11 do not follow this trend. The expected values of the number of patients are 417.07 (), 426.13 (), 399.63 (), and 402.13 (). The trend does not hold because the surgical durations in constraints (5) in the strategic phase are for surgical clusters whereas the surgical durations in constraints (86) in the tactical phase are for surgeons.

Table 10.

Number of Patients (Strategic Phase).

Table 11.

Number of Patients (Tactical Phase).

Table 12 shows the number of RW beds assigned to each surgical specialty in the strategic phase. In each level, all available RW beds are assigned. The RW bed assignments are influenced by a complicated relationship between two factors: number of patients scheduled and mean patient LOS. Overall, more patients are scheduled as increases. However, there could be variations between specialties. The mean patient LOS for surgical specialties ordered from highest to lowest are urology (3.4 days), general (2.7 days), gynecology (2.3 days), orthopedic (2.2 days), plastic (1.6 days), and ear–nose–throat (1.2 days) [64]. For urology, the RW bed assignment increases from 16 () to 34 (. For general, the allocation decreases from 73 () to 21 () and then increases to 25 (). For gynecology, there is an increase from 9 () to 20 (). For orthopedic, the assignment increases from 12 () to 37 () before decreasing to 22 (). For plastic, the increase is from 5 () to 11 (). For ear–nose–throat, there is an increase from 5 () to 8 ().

Table 12.

Number of Assigned RW Beds (Strategic Phase).

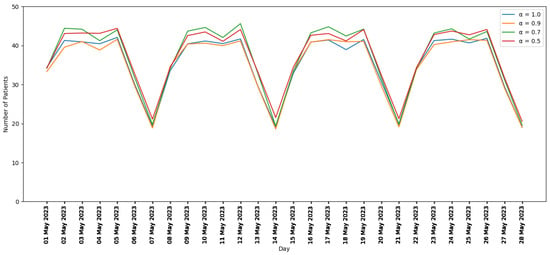

Figure 14 shows RW censuses for the tactical phase. In the tactical phase, goals 3 and 4 in the objective function (79) balance the utilization of RW beds. The RW censuses in Figure 14 show that the RW beds are balanced. There is a complicated relationship between the number of patients scheduled, the mean patient LOS, and the RW census. However, because the four curves almost overlap with each other, changing has a negligible impact on the RW census.

Figure 14.

RW Censuses (Tactical phase).

Table 13 shows the ORUU in the tactical phase. ORUU should be in the 10% to 30% range [58,63,66]. The results in Table 13 confirm that this holds in the tactical phase. Expected values of ORUU are 18.6% (), 18.2% (), 20.1% (), and 19.0% (. The expected values of number of patients scheduled in the tactical phase and ORUU have an inverse relationship. As the expected value of the number of patients increases from 417.07 () to 426.13 (), the expected value of ORUU decreases from 18.6% () to 18.2% (). As the expected value of the number of patients decreases from 426.13 () to 399.63 (), the expected value of ORUU increases from 18.2% () to 20.1% (). As the expected value of the number of patients increases from 399.63 () to 402.13 (), the expected value of ORUU decreases from 20.1% () to 19.0% ().

Table 13.

ORUU (Tactical Phase).

4. Conclusions

In this paper, an approach for developing DSS is presented. The DSS is based around existing mathematical models for strategic and tactical OR planning [8,9,10]. An iterative SDLC model with system initiation, system requirements, system requirements, and system design phases is applied to develop the DSS. The optimization and simulation systems in the DSS enable the generation and visualization of strategic and tactical OR plans.

A computational experiment is performed to evaluate the OR plans generated by the DSS. The results show that the plans perform well with respect to several performance measures: total benefit, number of patients scheduled, assignments of RW beds to surgical specialties, ORUU, and the balancing of RW beds in daily censuses. In particular, the expected value of ORUU never exceeds 21%, and the RW bed utilization is balanced and never higher than the number of available RW beds. In addition, the results are analyzed in order to examine trends.

The DSS is a valuable tool that enables OR planners and hospital managers to utilize the system of ORs and RW beds more efficiently. When these resources are used this way, patients are able to be operated on in a timely manner, which improves their welfare.

In future work, the approach for creating DSS could be generalized and applied to other problem domains in healthcare, such as nurse scheduling, outpatient scheduling, or the management of intensive care unit beds, and other industries. The developed DSS could easily be expanded to consider the operational phase of OR scheduling. In addition, some of the lower-priority items in the MoSCoW analysis diagram (Figure 4) could be implemented.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.B., A.A. and M.F.B.; methodology, J.B.; software, J.B.; validation, J.B.; formal analysis, J.B.; investigation, J.B.; resources, A.A. and M.F.B.; data curation, J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, J.B.; writing—review and editing, A.A. and M.F.B.; visualization, J.B.; supervision, A.A. and M.F.B.; project administration, A.A. and M.F.B.; funding acquisition, A.A. and M.F.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The second author’s research was partially funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant RGPIN/06897-2017. The third author’s research was partially funded by an NSERC Discovery Grant.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in OSF at https://osf.io/j4ehx/ (accessed on 30 October 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| AST | Abstract Syntax Tree |

| DES | Discrete Event Simulation |

| DSS | Decision Support System |

| ECS | Entity Component System |

| FHIR | Fast Health Interoperability Resources |

| GUI | Graphical User Interface |

| HL7 | Health Level 7 |

| HM | Hierarchical Models |

| IDEF0 | Integrated DEFinition 0 |

| LOS | Length of Stay |

| OR | Operating Room |

| ORUU | OR underutilization |

| RW | Recovery Ward |

| SDLC | System Development LifeCycle |

| SP | Strategic Planning |

| UML | Unified Modeling Language |

| WGPM | Weighted Goal Programming Model |

References

- Kennedy, M.H. Bin-Packing, Knapsack and Chance-Constrained Approaches to Operating Room Scheduling. Ph.D. Thesis, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Testi, A.; Tanfani, E.; Torre, G. A three-phase approach for operating theatre schedules. Health Care Manag. Sci. 2007, 10, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Demeulemeester, E. A multilevel integrative approach to hospital case mix and capacity planning. Comput. Oper. Res. 2013, 40, 2198–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaabane, S.; Meskens, N.; Guinet, A.; Laurent, M. Comparison of two methods of operating theatre planning: Application in Belgian hospital. In Proceedings of the 2006 International Conference on Service Systems and Service Management, Troyes, France, 25–27 October 2006; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2006; Volume 1, pp. 386–392. [Google Scholar]

- Beliën, J.; Demeulemeester, E. Building cyclic master surgery schedules with leveled resulting bed occupancy. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2007, 176, 1185–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekhici, L.; Belkadi, K. A Bi-Objective Paediatric Operating Theater Scheduling. Int. J. Healthc. Inf. Syst. Inform. 2023, 18, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielly, G.; Ouazene, Y.; Nguyen, N.Q. Enhanced mathematical formulation for operating room scheduling problem. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2025, 59, 2076–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britt, J.; Baki, M.F.; Azab, A.; Chaouch, A.; Li, X. A stochastic hierarchical approach for the master surgical scheduling problem. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 158, 107385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britt, J.; Li, X.; Azab, A.; Baki, M.F. Stochastic goal programming and metaheuristics for the master surgical scheduling problem. Int. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 43, 5–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britt, J. Mathematical Programming and Heuristic Design for Planning of Operating Rooms. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Windsor (Canada), Windsor, ON, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, J.T.; Carter, M.W. Surgical process scheduling: A structured review. J. Soc. Health Syst. 1997, 5, 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Pariente, J.M.M.; Torres, J.M.F.; Rodríguez, P.L.G.; Pineda, J.L.A. Planificación quirúrgica: Revisión de la literatura. In Proceedings of the XIII Congreso de Ingeniería de Organización, Barcelona-Terrassa, Spain, 2–4 September 2009; pp. 1346–1355. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoen, B.; Demeulemeester, E.; Beliën, J. Operating room planning and scheduling: A literature review. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2010, 201, 921–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerriero, F.; Guido, R. Operational research in the management of the operating theatre: A survey. Health Care Manag. Sci. 2011, 14, 89–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, J.H.; Spangler, W.E.; Strum, D.P.; Vargas, L.G. The surgical scheduling problem: Current research and future opportunities. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2011, 20, 392–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulshof, P.J.; Kortbeek, N.; Boucherie, R.J.; Hans, E.W.; Bakker, P.J. Taxonomic classification of planning decisions in health care: A structured review of the state of the art in OR/MS. Health Syst. 2012, 1, 129–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez-Restrepo, P.A.; Rodríguez-Quintero, A.K.; Jaén-Posada, J.S. Methodological approach to the planning and scheduling of operating rooms: A literature review. Rev. Gerenc. Y Políticas De Salud 2013, 12, 249–266. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrand, Y.B.; Magazine, M.J.; Rao, U.S. Managing operating room efficiency and responsiveness for emergency and elective surgeries—A literature survey. IIE Trans. Healthc. Syst. Eng. 2014, 4, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Riet, C.; Demeulemeester, E. Trade-offs in operating room planning for electives and emergencies: A review. Oper. Res. Health Care 2015, 7, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samudra, M.; Van Riet, C.; Demeulemeester, E.; Cardoen, B.; Vansteenkiste, N.; Rademakers, F.E. Scheduling operating rooms: Achievements, challenges and pitfalls. J. Sched. 2016, 19, 493–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hof, S.; Fügener, A.; Schoenfelder, J.; Brunner, J.O. Case mix planning in hospitals: A review and future agenda. Health Care Manag. Sci. 2017, 20, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gür, Ş.; Eren, T. Application of operational research techniques in operating room scheduling problems: Literature overview. J. Healthc. Eng. 2018, 2018, 5341394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Fan, W.; Yang, S.; Pei, J.; Pardalos, P.M. Operating room planning and surgical case scheduling: A review of literature. J. Comb. Optim. 2019, 37, 757–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razali, M.K.M.; Abd Rahman, A.H.; Ayob, M.; Jarmin, R.; Qamar, F.; Kendall, G. Research Trends in the Optimization of the Master Surgery Scheduling Problem. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 91466–91480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktas, E.; ATMACA, H.; Akbulut, H. Operating room and surgical team members scheduling: A comprehensive review. J. Proj. Manag. 2023, 9, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Amin, M.; Baldacci, R.; Kayvanfar, V. A comprehensive review on operating room scheduling and optimization. Oper. Res. 2025, 25, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.A.; Hadid, M.; Elomri, A.; Ismaen, R.; Dergaa, I.; Alashi, H.; Jobran Al-Hajaji, A.; Alkhalil, M.; Aboumarzouk, O.M.; Omri, A.E. Exploring the landscape of operating room scheduling: A bibliometric analysis of recent advancements and future prospects. Biomed. Eng. Comput. Biol. 2025, 16, 11795972241271549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusters, R.J.; Groot, P.M. Modelling resource availability in general hospitals design and implementation of a decision support model. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1996, 88, 428–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, J.T.; Donald, J. Mount Sinai hospital uses integer programming to allocate operating room time. Interfaces 2002, 32, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, J.T.; Dexter, F.; Donald, J. Operating room managers’ use of integer programming for assigning block time to surgical groups: A case study. Anesth. Analg. 2002, 94, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beliën, J.; Demeulemeester, E.; Cardoen, B. A decision support system for cyclic master surgery scheduling with multiple objectives. J. Sched. 2009, 12, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tancrez, J.S.; Roland, B.; Cordier, J.P.; Riane, F. How stochasticity and emergencies disrupt the surgical schedule. In Intelligent Patient Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoen, B.; Demeulemeester, E. A decision support system for surgery sequencing at UZ Leuven’s day-care department. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Decis. Mak. 2011, 10, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, C.; Sperandio, F.; Borges, J.; Almada-Lobo, B.; Brito, A. A Decision Support System for Surgery Theatre Scheduling Problems. In Proceedings of the International Conference on ENTERprise Information Systems, Beijing, China, 9–11 June 2011; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Essen, J.T.; Hurink, J.L.; Hartholt, W.; Van den Akker, B.J. Decision support system for the operating room rescheduling problem. Health Care Manag. Sci. 2012, 15, 355–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, M.W.; Ketabi, S. Bed balancing in surgical wards via block scheduling. J. Minim. Invasive Surg. Sci. 2013, 2, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tancrez, J.S.; Roland, B.; Cordier, J.P.; Riane, F. Assessing the impact of stochasticity for operating theater sizing. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 55, 616–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperandio, F.; Gomes, C.; Borges, J.; Brito, A.C.; Almada-Lobo, B. An intelligent decision support system for the operating theater: A case study. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2014, 11, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dios, M.; Molina-Pariente, J.M.; Fernandez-Viagas, V.; Andrade-Pineda, J.L.; Framinan, J.M. A decision support system for operating room scheduling. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2015, 88, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penn, M.; Potts, C.N.; Harper, P.R. Multiple criteria mixed-integer programming for incorporating multiple factors into the development of master operating theatre timetables. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 262, 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visintin, F.; Cappanera, P.; Banditori, C.; Danese, P. Development and implementation of an operating room scheduling tool: An action research study. Prod. Plan. Control 2017, 28, 758–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavel, D.; Mahulea, C.; Albareda, J.; Silva, M. A decision support system for elective surgery scheduling under uncertain durations. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meliana, I.R.; Purwoko, P.; Aisyati, A.; Piyandari, Y.; Rosyidi, C.N. An optimization model and decision support system of operating room scheduling in a teaching hospital. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. 2021, 25, 883–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifi, L. Digital Twin-Based Decision Support System for the Prospective and the Retrospective Analysis of an Operating Room Under Uncertainties. Ph.D. Thesis, Ecole des Mines d’Albi-Carmaux, Albi, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Smid, S. Development of a Decision Support System for Operating Room Schedule Management. Ph.D. Thesis, TUDelft, Delft, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoen, B.; Demeulemeester, E.; Beliën, J. Optimizing a multiple objective surgical case sequencing problem. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2009, 119, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoen, B.; Demeulemeester, E.; Beliën, J. Sequencing surgical cases in a day-care environment: An exact branch-and-price approach. Comput. Oper. Res. 2009, 36, 2660–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Balka, R.M.; Sakr, N.; Rabie, A.H.; Saleh, A.I. A dynamic operation room scheduling DORS strategy based on explainable AI and fuzzy interface engine. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, E.; Bykov, Y.; Birben, M.; Burke, E.K. Examination timetabling using late acceptance hyper-heuristics. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation, Trondheim, Norway, 18–21 May 2009; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 997–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, W.G.; Özcan, E.; Drake, J.H. Late acceptance-based selection hyper-heuristics for cross-domain heuristic search. In Proceedings of the 2013 13th UK Workshop on Computational Intelligence (UKCI), Guildford, UK, 9–11 September 2013; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, W.G.; Özcan, E.; John, R.I. Fuzzy adaptive parameter control of a late acceptance hyper-heuristic. In Proceedings of the 2014 14th UK workshop on computational intelligence (UKCI), Bradford, UK, 8–10 September 2014; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, E.K.; Eckersley, A.J.; McCollum, B.; Petrovic, S.; Qu, R. Hybrid variable neighbourhood approaches to university exam timetabling. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2010, 206, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, E.K.; Bykov, Y. The late acceptance hill-climbing heuristic. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 258, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, S.; Gelatt, C.D., Jr.; Vecchi, M.P. Optimization by simulated annealing. Science 1983, 220, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černỳ, V. Thermodynamical approach to the traveling salesman problem: An efficient simulation algorithm. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 1985, 45, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, H.R.; Martin, O.C.; Stützle, T. Iterated local search. In Handbook of Metaheuristics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 320–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duff, T.; Burgess, J.; Christensen, P.; Hery, C.; Kensler, A.; Liani, M.; Villemin, R. Building an orthonormal basis, revisited. J. Comput. Graph. Tech. 2017, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Rafaliya, N.; Baki, M.F.; Chaouch, B.A. Scheduling elective surgeries: The tradeoff among bed capacity, waiting patients and operating room utilization using goal programming. Health Care Manag. Sci. 2017, 20, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebali, A.; Alouane, A.B.H.; Ladet, P. Operating rooms scheduling. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2006, 99, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dexter, F.; Blake, J.T.; Penning, D.H.; Lubarsky, D.A. Calculating a potential increase in hospital margin for elective surgery by changing operating room time allocations or increasing nursing staffing to permit completion of more cases: A case study. Anesth. Analg. 2002, 94, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dexter, F.; Blake, J.T.; Penning, D.H.; Sloan, B.; Chung, P.; Lubarsky, D.A. Use of linear programming to estimate impact of changes in a hospital’s operating room time allocation on perioperative variable costs. Anesthesiology 2002, 96, 718–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dexter, F.; Ledolter, J.; Wachtel, R.E. Tactical decision making for selective expansion of operating room resources incorporating financial criteria and uncertainty in subspecialties’ future workloads. Anesth. Analg. 2005, 100, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Houdenhoven, M.; van Oostrum, J.M.; Hans, E.W.; Wullink, G.; Kazemier, G. Improving operating room efficiency by applying bin-packing and portfolio techniques to surgical case scheduling. Anesth. Analg. 2007, 105, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Oostrum, J.M.; Parlevliet, T.; Wagelmans, A.P.; Kazemier, G. A method for clustering surgical cases to allow master surgical scheduling. INFOR Inf. Syst. Oper. Res. 2011, 49, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagnol, G.; Barner, C.; Borndörfer, R.; Grima, M.; Seeling, M.; Spies, C.; Wernecke, K. Robust allocation of operating rooms: A cutting plane approach to handle lognormal case durations. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 271, 420–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Veen-Berkx, E.; Elkhuizen, S.G.; Van Logten, S.; Buhre, W.F.; Kalkman, C.J.; Gooszen, H.G.; Kazemier, G.; Collaborative, D.O.R.B. Enhancement opportunities in operating room utilization; with a statistical appendix. J. Surg. Res. 2015, 194, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).