Chaos in Control Systems: A Review of Suppression and Induction Strategies with Industrial Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Contemporary Challenges and Opportunities

1.2. Research Motivation and Key Challenges

1.3. Scope and Research Framework

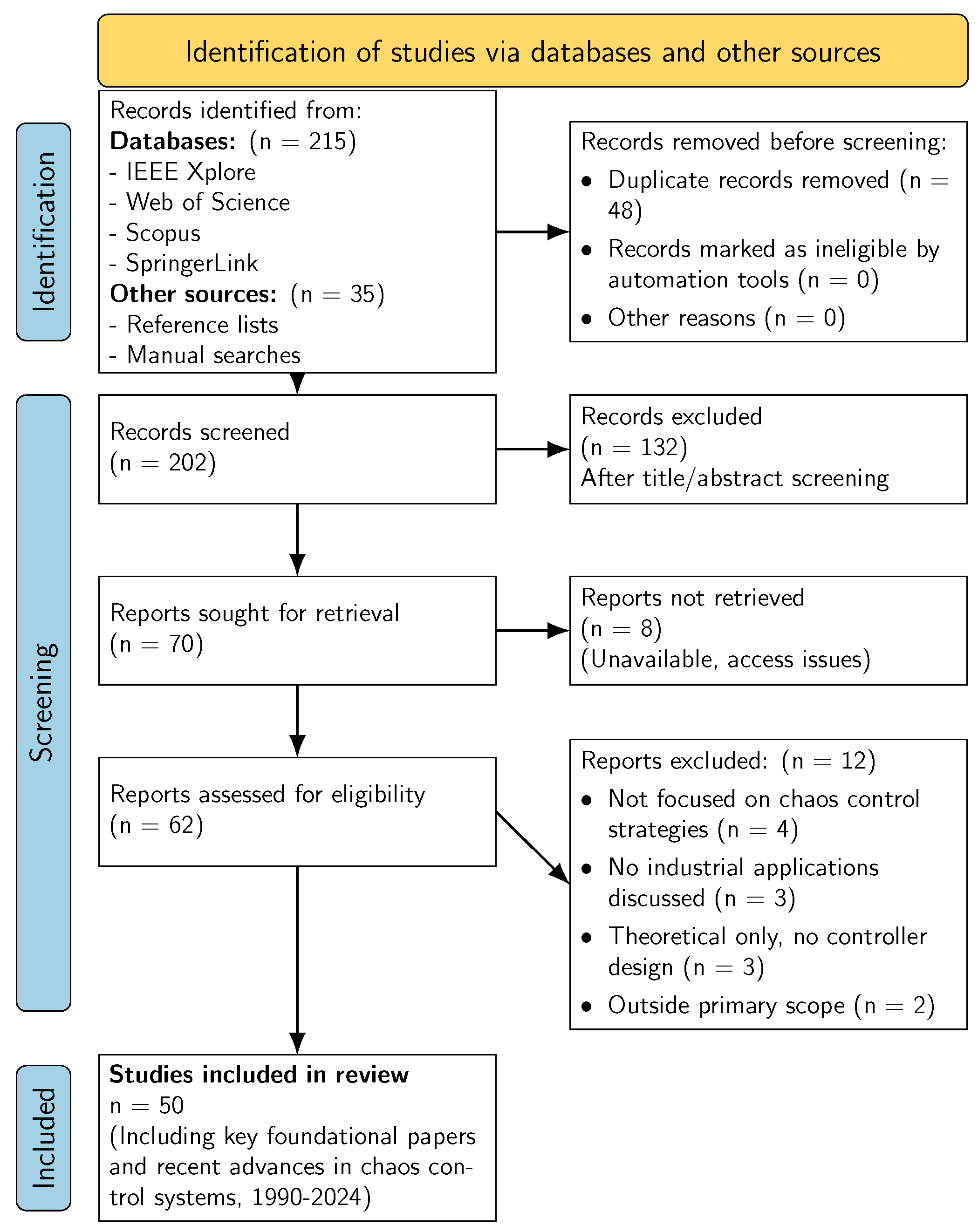

1.4. Literature Search and Selection Process

2. Theoretical Foundations

2.1. Mathematical Characterization of Chaotic Systems

2.2. Dynamical Systems Theory and Chaos Control

2.3. Control Theoretic Foundations

2.3.1. Controllability and Observability in Chaotic Systems

2.3.2. Stability Analysis Framework

2.3.3. Entropy and Complexity Measures

3. Chaos Suppression Methodologies

3.1. Advanced Feedback Control Techniques

3.2. Machine Learning-Enhanced Suppression

3.3. Critical Assessment and Comparative Limitations

4. Beneficial Chaos Exploitation

4.1. Vibration Systems and Oscillatory Devices

4.2. Signal Processing and Communication

4.3. Energy Harvesting Applications

Industrial Case Study: Chaotic Mixing in Chemical Microreactor

5. Specialized Controllers for Chaos

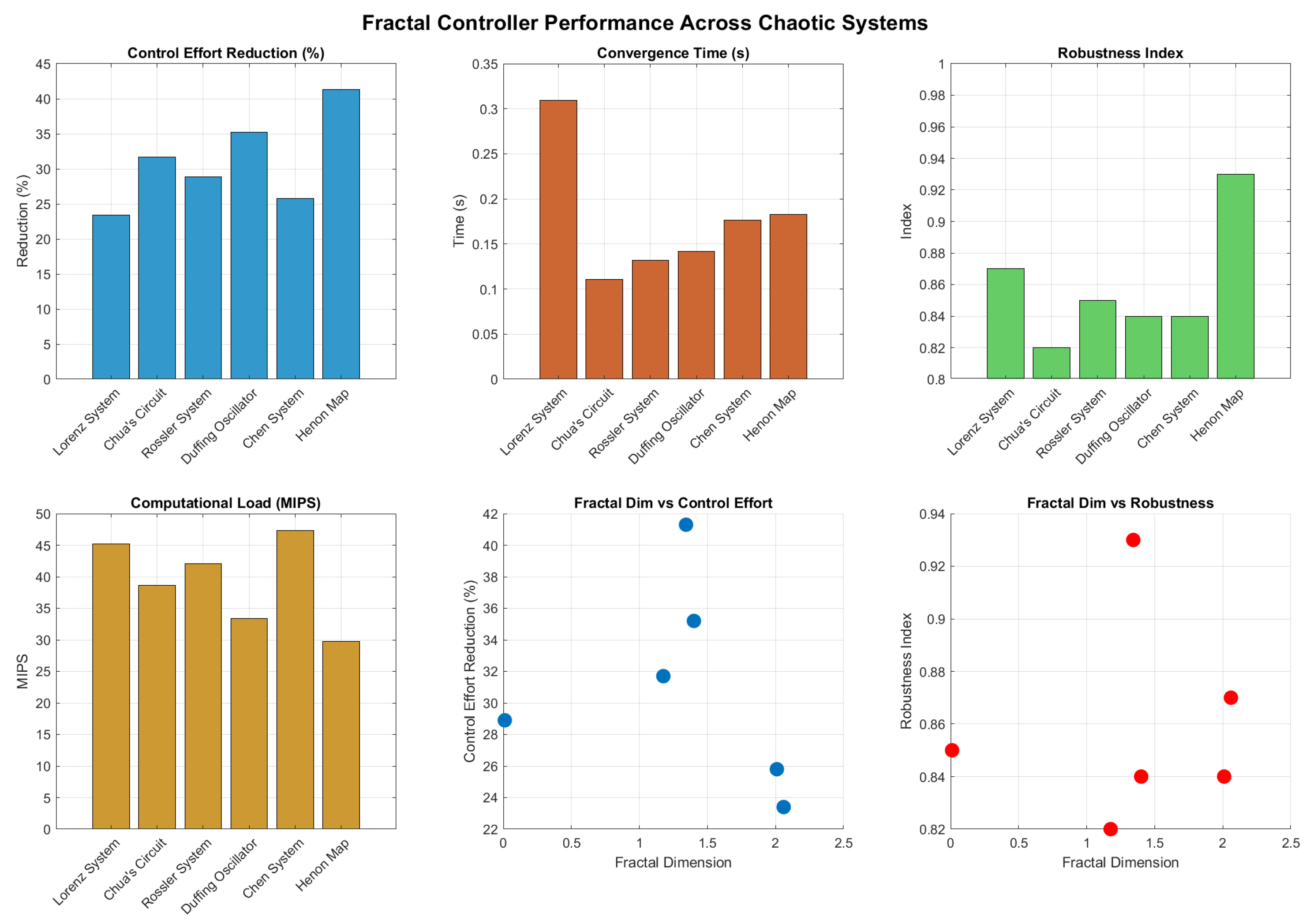

5.1. Fractal-Based Controller Architectures

5.1.1. Mathematical Foundations and Design Principles

5.1.2. Implementation and Performance Analysis

5.2. Adaptive Chaos Control Systems

5.2.1. Self-Tuning Parameter Adaptation Mechanisms

5.2.2. Machine Learning Integration and Neural Network Architectures

5.3. Hybrid Control Strategies and Multi-Mode Systems

5.3.1. Switching Control Architectures

5.3.2. Multi-Objective Optimization in Hybrid Systems

5.4. Bio-Inspired and Nature-Based Control Architectures

5.4.1. Biological System Analogies and Neuromorphic Approaches

5.4.2. Swarm Intelligence and Distributed Control

5.5. Implementation Challenges and Solutions

Real-Time Computational Requirements

6. Future Research Directions

6.1. Theoretical Developments

6.1.1. Advanced Mathematical Frameworks

6.1.2. Multi-Scale Analysis

6.2. Technological Innovations

6.2.1. Quantum-Enhanced Control

6.2.2. Bio-Inspired Control Systems

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OGY | Ott–Grebogi–Yorke |

| SMC | Sliding Mode Control |

| MPC | Model Predictive Control |

| DRL | Deep Reinforcement Learning |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| NN | Neural Network |

| PID | Proportional–Integral–Derivative |

| LQR | Linear Quadratic Regulator |

References

- Strogatz, S.H. Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos: With Applications to Physics, Biology, Chemistry, and Engineering; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Qian, F.; Gao, H.; Kurths, J. Synchronization in Complex Networks and Its Application—A Survey of Recent Advances and Challenges. Annu. Rev. Control 2014, 38, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Tan, F. A Chaotic Secure Communication Scheme Based on Synchronization of Double-Layered and Multiple Complex Networks. Nonlinear Dyn. 2019, 96, 869–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alligood, K.T.; Sauer, T.D.; Yorke, J.A. Chaos: An Introduction to Dynamical Systems; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ott, E.; Grebogi, C.; Yorke, J.A. Controlling Chaos. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1990, 64, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, B.; Zhong, W. Multi-Objective Optimization Using Chaos Based PSO. Inf. Technol. J. 2011, 10, 1908–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Sun, J. Controllability and Observability for Impulsive Systems in Complex Fields. Nonlinear Anal. Real World Appl. 2010, 11, 1513–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, J.C.; Bryant, P.H.; Creveling, D.R.; Klein, S.R.; Abarbanel, H.D. Parameter and State Estimation of Experimental Chaotic Systems Using Synchronization. Phys. Rev. E 2009, 80, 016201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidouche, B.; Guesmi, K.; Essounbouli, N. Control and Stabilization of Chaotic Systems Using Lyapunov Stability Theory. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Advanced Technology (ICEEAT), Fesdis, Algeria, 5–7 November 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Scarciglia, A.; Catrambone, V.; Bonanno, C.; Valenza, G. A Multiscale Partition-Based Kolmogorov–Sinai Entropy for the Complexity Assessment of Heartbeat Dynamics. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, L.; Lin, F.; Bin, Q. Adaptive Neural Network Control of Chaotic Fractional-Order Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors Using Backstepping Technique. Front. Phys. 2020, 8, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahloul, W.; Chtourou, M.; Ammar, M.B.; Hadjabdallah, H. Robust Neural Controllers for Power System Based on New Reduced Models. Adv. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2023, 21, 107. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Q. Dynamic Surface Sliding Mode Control of Chaos in the Fourth-Order Power System. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2023, 170, 113420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loudahi, L.; Yuan, J.; Dehbi, L.; Osman, M. Stabilization and Synchronization of a New 3D Complex Chaotic System via Adaptive and Active Control Methods. Axioms 2025, 14, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rega, G.; Lenci, S.; Thompson, J.M.T. Controlling Chaos: The OGY Method, Its Use in Mechanics, and an Alternative Unified Framework for Control of Non-Regular Dynamics. In Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos: Advances and Perspectives; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Maximilian, D.; Raffaele, S. Adaptive Economic Model Predictive Control for Linear Systems with Performance Guarantees. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.18398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Sha, H.; Guo, R. Disturbance Estimator-Based Reinforcement Learning Robust Stabilization Control for a Class of Chaotic Systems. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2025, 198, 116547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Xu, J.; Sun, H.; Wang, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Yin, W. Enhancement of Chaotic Mixing Performance in Laminar Flow with Reciprocating and Rotating Coupled Agitator. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2023, 280, 118988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.C.; Wei, S.X.; Xie, T.L.; Liu, Q.; Au, C.T.; Yin, S.F. High-Throughput Synthesis of High-Purity and Ultra-Small Iron Phosphate Nanoparticles by Controlled Mixing in a Chaotic Microreactor. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2023, 280, 119084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejazian, M.; Balaur, E.; Abbey, B. Recent Advances and Future Perspectives on Microfluidic Mix-and-Jet Sample Delivery Devices. Micromachines 2021, 12, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Li, X.; Liu, X. Chaotic Vibration Prediction of a Laminated Composite Cantilever Beam Subject to Random Parametric Error. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strunk, G.; Lichtwarck-Aschoff, A. Therapeutic Chaos. J. Pers.-Oriented Res. 2019, 5, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhobale, S.M.; Chatterjee, S. Synthesis of a Hybrid Control Algorithm for Chaotifying Mechanical Systems. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2024, 189, 115670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, T.; Ye, S.; Zhang, X.; Ju, J.; Zhao, H.; Long, Z. An Improved PDM Modulation Algorithm for Power Ultrasonic Cleaning System. Appl. Acoust. 2025, 238, 110722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Cui, Z.; Yan, W.; Huang, H.; Ding, W. Accelerated Fatigue Test for Electric Vehicle Reducer Based on the SVR–FDS Method. Sensors 2024, 24, 5359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Z.R.; Chang, Y.Z.; Zhang, H.W.; Lin, C.T. Relax the Chaos-Model-Based Human Behavior by Electrical Stimulation Therapy Design. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 67, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sun, L.; Liu, X.; Duo, Y. Chaotic Vibration Prediction of a Laminated Composite Cantilever Beam. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.; Joshi, M.; Upadhyay, K.K.; Khare, V.; Shastri, H.; Goyal, S. Realization of Chaotic Oscillator and Use in Secure Communication. e-Prime-Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2023, 6, 100321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Liu, L.; Liang, Y.; Han, Z.; Wang, X. Chaotic Mapping-Based Anti-Sorting Radio Frequency Stealth Signals and Compressed Sensing-Based Echo Signal Processing Technology. Entropy 2022, 24, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Li, L.; Yuan, Z. A Multi-Image Encryption Scheme Based on a New Dimensional Chaotic Model and Eight-Base DNA. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2024, 186, 115332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucio-Gutiérrez, A.; Tututi-Hernández, E.S.; Uriostegui-Legorreta, U. Analysis of the Dynamics of a ϕ6 Duffing Type Jerk System. Chaos Theory Appl. 2024, 6, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, L.G.; Reis, E.V.M.; Savi, M.A. Energy Harvesting from Chaotic Vibration. In Proceedings of the 26th International Congress of Mechanical Engineering (COBEM 2021), Florianópolis, Brazil, 22–26 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Ali, S.F.; Arockiarajan, A. Enhanced Energy Harvesting from Nonlinear Oscillators via Chaos Control. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2016, 49, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adıgüzel, F. An Adaptive Nonlinear Controller Design for a Class of Uncertain Chaotic Systems with Single Input Using Linear Model Reference. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2025, 199, 116683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfi, A.; Kalat, A.A.; Farrokhnejad, F. Hybrid Control Strategy Applied to Chaos Synchronization: New Control Design and Stability Analysis. Int. J. Dyn. Control 2018, 6, 809–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souhail, W.; Khammari, H. A Three-Stage Neural Network-Based Control Design for Chaos Synchronization in A Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors (PMSM). Adv. Control Appl. Eng. Ind. Syst. 2025, 7, e70023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merah, L.; Adnane, A.; Ali-Pacha, A.; Ramdani, S.; Hadj-Said, N. Real-Time Implementation of a Chaos Based Cryptosystem on Low-Cost Hardware. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Electr. Eng. 2021, 45, 1127–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejcar, O.; Namazi, H. Multiscale Brain Modeling: Bridging Microscopic and Macroscopic Brain Dynamics for Clinical and Technological Applications. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1537462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takatsuka, K. Quantum Chaos in the Dynamics of Molecules. Entropy 2022, 25, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Method | Convergence Time (s) | Robustness | Energy Efficiency | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OGY Control | 5–8 | Medium | High | Simple |

| Neural Network | 1–3 | High | Medium | Complex |

| Sliding Mode | 2–4 | Very High | Low | Medium |

| Adaptive Fuzzy | 3–6 | High | Medium | Medium |

| Model Predictive | 1–2 | Very High | Medium | Complex |

| Application | Performance Improvement | Energy Reduction | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Material Compaction | +28% | −15% | [23] |

| Ultrasonic Cleaning | +31% | −22% | [24] |

| Fatigue Testing | +19% | −8% | [25] |

| Therapeutic Massage | +25% | −12% | [26] |

| Sieving Operations | +33% | −18% | [27] |

| Chaotic System | Fractal Dim. | Control Effort | Convergence | Robustness | Computational |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eduction (%) | Time (s) | Index | Load (MIPS) | ||

| Lorenz System | 2.06 | 23.4 | 0.30963 | 0.87 | 45.2 |

| Chua’s Circuit | 1.176 | 31.7 | 0.1106 | 0.82 | 38.6 |

| Rössler System | 0.111 | 28.9 | 0.13198 | 0.85 | 42.1 |

| Duffing Oscillator | 1.4005 | 35.2 | 0.1417 | 0.84 | 33.4 |

| Chen System | 2.01 | 25.8 | 0.17655 | 0.84 | 47.3 |

| Hénon Map | 1.3425 | 41.3 | 0.1827 | 0.93 | 29.7 |

| Average | 0.49 | 31.1 | 0.2 | 0.86 | 39.4 |

| Controller Type | Learning | Adaptation | Tracking | Disturbance | Computational |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Speed | Rate | Error | Rejection | Complexity | |

| (Epochs) | (s−1) | (RMSE) | (dB) | (Scale 1–10) | |

| Model Reference | 250 | 0.15 | 0.087 | −12.4 | 3 |

| Gradient Descent | 180 | 0.22 | 0.061 | −16.8 | 4 |

| Neural Network | 95 | 0.41 | 0.034 | −23.7 | 7 |

| Fuzzy Logic | 120 | 0.38 | 0.045 | −19.2 | 6 |

| Genetic Algorithm | 320 | 0.08 | 0.076 | −14.1 | 8 |

| Reinforcement Learning | 75 | 0.52 | 0.028 | −28.3 | 9 |

| Hybrid (NN+Fuzzy) | 85 | 0.47 | 0.031 | −26.1 | 8 |

| Best Performance | RL | RL | RL | RL | MR |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shafique, A.; Kolev, G.; Bayazitov, O.; Bobrova, Y.; Kopets, E. Chaos in Control Systems: A Review of Suppression and Induction Strategies with Industrial Applications. Mathematics 2025, 13, 4015. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13244015

Shafique A, Kolev G, Bayazitov O, Bobrova Y, Kopets E. Chaos in Control Systems: A Review of Suppression and Induction Strategies with Industrial Applications. Mathematics. 2025; 13(24):4015. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13244015

Chicago/Turabian StyleShafique, Asad, Georgii Kolev, Oleg Bayazitov, Yulia Bobrova, and Ekaterina Kopets. 2025. "Chaos in Control Systems: A Review of Suppression and Induction Strategies with Industrial Applications" Mathematics 13, no. 24: 4015. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13244015

APA StyleShafique, A., Kolev, G., Bayazitov, O., Bobrova, Y., & Kopets, E. (2025). Chaos in Control Systems: A Review of Suppression and Induction Strategies with Industrial Applications. Mathematics, 13(24), 4015. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13244015