Abstract

Mitomycin-C (MMC) is the leading chemotherapeutic agent for the treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC), but recurrence rates remain high due to poorly understood interactions between the tumor, immune system, and drugs. We present a five-equation mathematical model that explicitly tracks MMC, tumor cells, dendritic cells (DCs), effector T cells, and regulatory T cells (Tregs). The model incorporates clinically realistic treatment regimens (6-week induction followed by maintenance therapy), including DC activation by tumor debris, dual DC activation of effector and Treg cells, and reversal of MMC-induced immunosuppression. The resulting nonlinear system exhibits hidden multiscale dynamics. We apply the singular perturbed vector field (SPVF) method to identify fast–slow hierarchies, decompose the system, and conduct stability analysis. Our results reveal stable equilibria corresponding to either tumor eradication or persistence, with a critical dependence on the initial tumor size and growth rate. Modeling shows that increased DC production paradoxically contributes to treatment failure by enhancing Treg activity—a non-monotonic immune response that challenges conventional wisdom. These results shed light on the mechanisms of NMIBC evolution and highlight the importance of balanced immunomodulation in the development of therapeutic strategies.

Keywords:

bladder cancer; MMC chemotherapy; SPVF method; multiscale dynamics; stability analysis; Heaviside function; immune response; Tregs MSC:

92B05

1. Introduction

Mitomycin-C (MMC) is the most widely used chemotherapeutic drug for the treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC, referred to here as BC) [1]. As an alkylating agent, MMC works by cross-linking complementary strands of DNA, inhibiting DNA synthesis and eventually leading to cell death [2,3,4]. This medication has been proven effective for decreasing recurrence rates in the short term; yet, within a few years, there remains a substantial risk of relapse and progression to muscle-invasive disease [5,6]. Given the limited efficacy of MMC, investigating its mechanism of action within the tumor microenvironment is essential for identifying patterns of NMIBC evolution and relapse.

In previous work, we established the first quantitative temporal framework for studying the effects of MMC chemotherapy on tumor–immune dynamics in BC [7]. This model converted the values of ‘tumor size’, a prognostic factor for recurrence, into tumor cell counts and identified a theoretical threshold beyond which treatment outcomes transition from success to failure. That is, the dynamics of the tumor cells exhibited a critical dependence on the interplay between the tumor growth rate and the intensity of tumor killing by the immune system. Furthermore, the model allows one to calculate an upper bound to the drug dose of MMC, for which the tumor is eliminated.

Whilst providing new insights into the tumor–immune relationship, the previous model [7] assumes immune-cell homogeneity under the umbrella term ‘effector cells’, thereby limiting its explanatory power. Within the present framework, we extended the model from a three- to a five-equation system, accounting for three immune subpopulations: dendritic cells (DCs), effector T cells, and regulatory T cells (Tregs). This transition is driven by several distinct biological processes absent from the original model. First, DCs and effector T cells exhibit different kinetics. While DCs are activated by tumor debris, effector cells require priming by DCs in a process that requires explicit DC–effector coupling, which cannot be captured by a homogeneous immune representation [8,9,10]. Second, Treg-mediated immunosuppression demands independent Treg dynamics, as they actively inhibit effector cells [10,11]. Third, differential patterns of abundance and functional activities among these cell types have been observed in clinical and experimental settings [11,12,13]. Taken together, each additional term and equation embodies a rate-limiting step in the immune cascade that cannot be approximated by the original three-equation system.

The mathematical challenge of model reformulation lies in the resulting complex system of ODEs. In other words, the addition of terms and variables to the previous simple model creates a large, nonlinear system, posing a considerable challenge for stability analysis beyond classic numerical methods. This type of complexity introduces a significant computational burden and is further complicated by hidden hierarchies of time scales. That is, fast and slow processes are not explicitly represented, despite the presence of elements at different levels of organization, such as drug molecules and cell subpopulations. Several asymptotic and numerical reduction methods—such as the iteration method of Fraser and Roussel [14,15,16], the method of integral invariant manifolds (MIM) [17,18], and the intrinsic low-dimensional manifold (ILDM) method [19,20,21,22]—have been developed to simplify multiscale models without losing information of the original system. In contrast to these approaches, which generally assume that the hierarchy is already known and that the model is formulated as a singularly perturbed system (SPS), we focus on exposing the hidden hierarchy.

To address the challenges posed by the stability analysis of the complex model, we chose to apply the Singularly Perturbed Vector Field (SPVF) method, which uniquely simplifies multiscale systems without losing information from the original model [23]. This new version of the ILDM method reveals the hidden hierarchy of the system and reformulates it as an SPS, where the dynamical variables are organized according to an explicit hierarchy. The first step involves identifying new coordinates and representing the governing equations in SPS form, allowing for the decomposition of the original system into fast and slow subsystems. One of the main outcomes of this decomposition is a reduction in the number of equations. This, in turn, enables the application of asymptotic and analytical methods, thereby facilitating stability analysis of the reduced system and providing deeper insight into the temporal dynamics of its core elements.

In this paper, we extend the previous model of MMC chemotherapy treatment for BC by introducing heterogeneity in immune subpopulations and implementing periodic drug administration using the Heaviside step function. The resulting five-ODE model presents high nonlinearity and a hidden hierarchy that challenge stability analysis beyond the classical numerical methods. To this end, we apply the SPVF method, which exposes the hidden hierarchy and decomposes the system into fast and slow subsystems, allowing detailed analysis of temporal dynamics. The aims of this study are therefore twofold: first, to extend the previous model to provide a more precise characterization of tumor–immune interactions, and second, to uncover fast and slow dynamics of the model and perform stability analysis. Overall, this approach enables the systematic exploration of the processes underlying BC evolution in response to MMC treatment, and paves the way to generate new hypotheses regarding their temporal order.

2. The Mathematical Model

In this section, we present the complete system of governing ODEs, including the model formulation, the underlying assumptions, the derivation of each equation, and the estimated parameters. In this study, the tumor growth rate r and the DC-production rate are treated as the control parameters of the model. Their numerical values are provided in Section 2.3.

2.1. Model Assumptions

The formulation of the model relies on the following assumptions, with supporting evidence from the literature presented in the model derivation (see Section 2.2):

- Tumor cells follow the logistic growth law and undergo growth arrest during MMC administrations.

- The activation of DCs is proportional to the fraction of tumor cells killed by MMC, in a saturated Michaelis–Menten relation.

- There is no activation of DCs by tumor cells outside of treatment.

- There is no intrinsic growth of effector cells since they require the priming and cross presentation of DCs, therefore assumed to be generated only in the presence of DCs.

- The suppression of effector cells by Tregs involves not only a reduction in count but also the diminished functional activity of effector cells, which depends on both Tregs and tumor cell counts.

- MMC treatment has no direct effects on effector cells.

- Both Tregs activation and Tregs-mediated suppression of effector cells are arrested during MMC administrations.

- MMC interactions have identical half-saturation constants.

2.2. Model Derivation

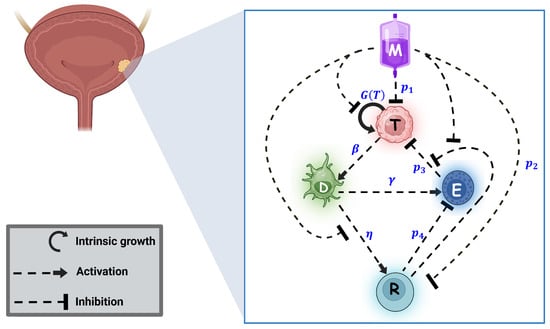

Our mathematical model consists of a system of ODEs that describes interactions between tumor cells and the immune system in response to MMC chemotherapy treatment. Specifically, we track the temporal dynamics of five populations presented in Table 1. The model was formulated by considering specific forms of cell growth and death, cell–cell interactions, and drug–cell interactions (see Figure 1). Our model is defined by the following ODEs:

where

and

represent the induction and maintenance, respectively.

Table 1.

List of model variables and their descriptions. Drug concentrations are expressed in molar units as reported in experimental studies. Immune-cell populations () refer to absolute cell counts, consistent with the experimental measurements. However, for bladder tumors, the reported tumor-size is converted into an estimated tumor-cell count using the formula described in [7].

Table 1.

List of model variables and their descriptions. Drug concentrations are expressed in molar units as reported in experimental studies. Immune-cell populations () refer to absolute cell counts, consistent with the experimental measurements. However, for bladder tumors, the reported tumor-size is converted into an estimated tumor-cell count using the formula described in [7].

| Variable | Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| MMC chemotherapy drug amount at time t | M | |

| Tumor cancer cells population at time t | cells | |

| DCs population at time t | cells | |

| Effector cells population at time t | cells | |

| Tregs population at time t | cells |

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the model. Tumor cells follow logistic growth given by . MMC administration results in a multifaceted response. MMC arrests tumor growth and causes tumor cell death at rate . Dying tumor cells then activate DCs at rate . DCs activate both types of immune cells—effector T-cells and Tregs —at rates and , respectively. While effector cells kill tumor cells at rate , this process of killing is inhibited by Tregs , and also the count of effector cells is reduced by Tregs at rate . MMC reverses the immunosuppression of Tregs by inhibiting its activation by DCs , reducing its count at rate and inhibiting its suppression of the effector killing. Note that interactions defined solely by detailed mathematical terms are exclusively present in system (1). This image was created with BioRender.com.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the model. Tumor cells follow logistic growth given by . MMC administration results in a multifaceted response. MMC arrests tumor growth and causes tumor cell death at rate . Dying tumor cells then activate DCs at rate . DCs activate both types of immune cells—effector T-cells and Tregs —at rates and , respectively. While effector cells kill tumor cells at rate , this process of killing is inhibited by Tregs , and also the count of effector cells is reduced by Tregs at rate . MMC reverses the immunosuppression of Tregs by inhibiting its activation by DCs , reducing its count at rate and inhibiting its suppression of the effector killing. Note that interactions defined solely by detailed mathematical terms are exclusively present in system (1). This image was created with BioRender.com.

The following outlines the biological reasoning behind each equation in the system (a brief summary of the equation terms is provided in Appendix A).

2.2.1. The Chemotherapeutic Agent MMC

The most commonly used MMC treatment consists of an induction phase with weekly intravesical instillations for 6–8 weeks, followed by a maintenance phase of monthly instillations for up to 1 year [24,25,26,27]. Accordingly, the model accounts for periodic drug administration. Assuming that an instillation of quantity m is introduced into the bladder every 7 days during the induction phase and every month (4 weeks) during the maintenance phase, the dosing schedule can be formulated using the Heaviside step function (similar to the approach of Rodrigues et al. [28]):

where:

and

correspond to the induction and maintenance pulses, given at intervals of 7 and 28 days, respectively. Here, denotes the instants of induction administration, which for a 6-week induction phase corresponds to . The course of the maintenance phase, beginning at week 11, comprises six instillations, with the final administration occurring at week 31. The duration of a single instillation, h days, is the same for both induction and maintenance phases [25,29,30]. The MMC dynamics is therefore modeled by

The term corresponds to the washout of MMC at rate [31,32].

2.2.2. The Tumor Cells

Tumor cells are assumed to constitute a homogeneous population for simplicity. We first present the tumor dynamics without treatment, as nontrivial interaction terms appear in the presence of MMC:

Here, tumor cells follow the logistic growth law, represented by the function :

where r and k are the growth rate and the carrying capacity of the tumor, respectively. The second term represents the effect of immune cells on tumor cells. It can be presented as a product of two expressions of interest. The mass-action expression stands for the killing of tumor cells by effector cells at a rate of [10,11,33]. However, the effectiveness of this killing is reduced in the presence of Tregs that suppress effector cell activity, with the factor of the form (biological justification can be found in [34]). This term is borrowed from [35], where killing occurs at the maximal rate in the absence of Tregs and decreases proportionally to an increasing Tregs count. We additionally assume a decline in killing efficiency with increasing the tumor cell count (clinical evidence related to tumor size is provided in [36]). This gradual reduction in tumor-killing effectiveness is incorporated by scaling the exponent with the carrying capacity of tumor k.

Next, we introduce the MMC-induced effects on tumor cells. These effects are expressed through a mediating Michaelis–Menten term that was used before by Yosef et al. [7], which accounts for the limited nature of drug pharmacodynamics, . Since M spans from 0 to approximately in simulations and the parameter a has a value of 75, this term saturates from 0 to nearly 1. Thus, in the presence of MMC, the Michaelis–Menten term represents a gradual “switch-on” of the drug effect. Its complementary form, , represents a “switch-off” or an activation-arrest term.

We apply these terms to represent the effects of MMC. First, MMC induces a cell-cycle arrest of tumor cells [33]; thus, an “switch-off” factor is included in the growth term during the exposure time. Second, the tumor cells are killed by MMC at an intensity proportional to their interaction with the drug, modeled with the “switch-on” term. The final term is formulated based on the information from Hori et al. [11], who suggested that MMC reverses immune suppression by reducing the expression of Tregs. Therefore, we make the reasonable assumption that during the 2 h treatment, this reduction is associated with an arrest of Tregs-mediated inhibitory activities on effector cells. Hence, the argument of the exponential is scaled by the “switch-off” term. This attenuation term is particularly important in our setting, as its smooth, exponential structure preserves the continuity of the vector field across the MMC treatment pulses and thereby avoids artificial discontinuities. Collectively, in the presence of MMC, the tumor cells evolve according to

2.2.3. DCs

Bladder-resident DCs are maintained through homeostatic production at a constant rate , and die due to natural mortality at rate [37]. Dying tumor cells, , activate DCs and increase their number at a constant rate [9,10,11]. Since tumor cell counts may span several orders of magnitude, the activation term is scaled by the saturation factor , where b denotes the carrying capacity of DCs . This ensures the DC counts remain within a biologically feasible range (see Appendix A for details). Considering these effects, the temporal evolution of DCs is governed by

2.2.4. Effector Cells

Cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) are represented here as effector cells . DCs recruit effector cells at a constant rate , in a process assumed to be proportional to the count of DCs [10,11,33]. The second term stands for the natural cell death at rate . The mass-action term, , represents the destruction of effector cells by Tregs [10,11]. Hence, effector cells dynamics follow:

It is noteworthy that even in the presence of the drug, the activation of effector cells is mediated exclusively by DCs in a process known as cross-priming [38].

2.2.5. Tregs

Under homeostatic conditions, Tregs are absent in the bladder tissue [37]. Instead, these cells are recruited solely from the circulation in response to factors secreted by cancer cells or surrounding immune cells [37,39]. Here, we assume that these factors correspond to signals released from dying cancer cells, which activate DCs . Consequently, it is possible to express the activation of Tregs collectively through DCs , by the term . It is indeed well-established that DCs induce Tregs activation [40]. Upon MMC administration, the immune suppression by Tregs is postulated to be reversed [10,11]. First, MMC effects reduce Tregs count at a constant rate , with a Michaelis–Menten functional term [11]. Second, the activation of Tregs is assumed to be “switched-off” during the 2 h MMC treatment. Biological support for this assumption can be found in [11], where MMC exposure has been shown to increase IL-17A and G-CSF and reduce the expression of FoxP3, collectively suggesting a shift toward a pro-inflammatory environment. Under such conditions, Treg activation is expected to be limited, and we therefore represent this process in the model as an activation arrest. The equation for Tregs dynamics is taken to be

Here, stands for the natural mortality rate of Tregs.

2.3. Parameter Estimation Values and Initial Conditions

The model parameters are listed in Table 2. Some were adopted from previous studies, while the estimation for the remaining parameters is detailed in Appendix A. The initial conditions of all model simulations are listed in Table 3 and were chosen such that the baseline value of immune cells corresponds to the steady-state solution of the model in the absence of treatment, assuming no change in immune cell count without treatment. For the remaining cases, the initial tumor size is varied to assess its effect, while the drug concentration is set to zero, as administration is governed exclusively by the Heaviside pulsing term. All simulations were performed in MATLAB 2023a using the stiff solver ode23s, a low-order method for solving stiff differential equations, chosen to be well-suited for our system, whose variables and parameters span widely varying magnitudes. A comparison with the stiff solver ode15s produced numerically indistinguishable trajectories from ode23s, confirming that both solvers are suitable. Moreover, a Sobol global sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the influence of parameters from diverse sources (see Appendix B), revealing that only a restricted subset strongly affects tumor-control outcomes.

Table 2.

Parameter descriptions and values (all parameters are of positive values).

Table 2.

Parameter descriptions and values (all parameters are of positive values).

| Parameter | Description | Estimated Value | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decay rate of MMC | [7] | ||

| m | Dose of MMC | 28,740 [M/day] | based on [41] |

| r | Proliferation rate of tumor cells | (0.01–0.045) | [42] |

| k | Carrying capacity of tumor cells | (0.09–1) [cells] | [7] |

| Killing rate of tumor cells by MMC | based on [33] | ||

| a | Half-saturation constant | 75 [M] | based on [33] |

| Production rate of DCs | based on [7] | ||

| Death rate of DCs | [43] | ||

| Activation rate of DCs by tumor cells | [44] | ||

| b | Carrying capacity of DCs | based on [13,45] | |

| Effector cells activation rate by DCs | [46] | ||

| Death rate of effector cells | (0.168–9.12) | [46,47] | |

| Tumor cells inhibition rate by effector cells | [48] | ||

| Inactivation rate of effector cells by Tregs | [46] | ||

| Inhibition rate of Tregs cells by MMC | based on [11] | ||

| Tregs recruitment by | [46] | ||

| Death rate of Tregs | [46] |

Table 3.

List of initial conditions for model simulations.

3. Well-Posedness Analysis

We consider the non-autonomous system

where the right-hand side is given by Equations (1a)–(1e), all parameters are strictly positive, and the pulse functions are finite sums of time-dependent Heaviside pulses of the form

Since the Heaviside functions depend only on time and have finitely many jumps, the right-hand side is piecewise smooth in Z and piecewise continuous in t. The existence and uniqueness will be shown in the sense of Carathéodory.

The biologically feasible state space is the non-negative orthant

Our aim is to establish the existence, uniqueness, positivity, boundedness, and global continuation of solutions of (2). All results below are stated in the sense of Carathéodory for non-autonomous ODEs with piecewise continuous right-hand side.

Lemma 1

(Regularity of the right-hand side). Let

Then, we have the following:

- For every l, the pulse functions are constant on . Consequently, for each fixed , the map is on .

- For every compact , there exists such that

- For each fixed , the map is piecewise continuous and locally bounded on ; in particular, it is measurable.

Proof.

On each interval , the pulse functions are constant with values in . The expressions (1a)–(1e) consist of polynomials, exponentials, and rational functions of the form with denominator for all . Compositions of such functions are and locally Lipschitz on ; this yields claims 1 and 2. For each fixed , the dependence is continuous on each and has only finitely many jump discontinuities at the times in , so is piecewise continuous and therefore locally bounded and measurable on . □

Lemma 2

(Positivity and forward invariance). The non-negative orthant : is positively invariant under (2): if , then for all .

Proof.

We examine the dynamics on each boundary hyperplane of :

- At : the pulses and do not overlap in time, and their sum satisfies , therefore:Thus, the vector field does not point outside the domain along the boundary .

- At : every term in contains a factor T, and hence, Equation (1b(b)) can be written in the factorized formwhere is continuous in the state variables on . If , then is a solution and is clearly non-negative for all . If , then for all :Thus, in both cases for all , and the T-component cannot become negative.

- At :

- At :

- At : since ,

Thus, whenever a component reaches zero, its derivative is non-negative. Therefore trajectories cannot exit through any boundary face, and is forward invariant. □

Lemma 3

(Boundedness of M). For all ,

Proof.

The pulses do not overlap in time, and hence

Thus

Comparison with the linear ODE yields the stated bound. Hence M is uniformly bounded on . □

Lemma 4

(Boundedness of T). For all ,

Proof.

Since and the last two terms in are nonpositive, we have

Comparison with the logistic equation gives

Thus T is uniformly bounded on . □

Lemma 5

(Boundedness of ). There exist constants such that, for all ,

Proof.

Boundedness of D. We rewrite

From Lemmas 3 and 4, the quantity is bounded:

for some constant . Hence

Comparison with yields

Boundedness of E. From

and , we obtain

Here the term can be dropped in an upper bound. Comparison with gives

Boundedness of R. We have

Since and ,

Comparison with implies

This completes the proof. □

Considering Lemmas 3–5, we conclude that all components are uniformly bounded on .

Definition 1 (Carathéodory solution).

Let be measurable in t and locally Lipschitz in Z. A function is called a Carathéodory solution of

if

- Z is absolutely continuous on , and

- for all ,Equivalently, holds for almost every .

Remark 1.

[Carathéodory’s existence–uniqueness theorem] We recall (see [49,50]) the following:

- is measurable in t;

- Locally bounded;

- Locally Lipschitz in Z.

If true, then for every , there exists a (possibly local) Carathéodory solution Z of with , and this solution is unique among Carathéodory solutions. Moreover, a solution can be extended as long as it remains in a compact subset of (i.e., no finite-time blow-up occurs).

Theorem 1.

Global well-posedness in the sense of Carathéodory.

For every initial condition , system (2) admits a unique global Carathéodory solution

The solution is continuous and piecewise , remains in for all , is uniformly bounded on , and depends continuously on the initial conditions and on all parameters.

Proof.

By Lemma 1, the vector field is measurable in t, locally Lipschitz in Z, and locally bounded on each interval between switching times.

By Lemma 2, is forward invariant.

By Lemmas 3–5, all components of are uniformly bounded on ; in particular, no finite-time blow-up can occur.

Therefore, Carathéodory’s existence–uniqueness theorem yields a unique local Carathéodory solution for each initial condition in , and the absence of finite-time blow-up implies that this solution extends uniquely to a global solution on . □

4. The SPVF Method

In this section, we provide a brief overview of the SPVF method which we use to decompose the system into its fast and slow subsystems and analyze the stability of the proposed model.

The SPVF method is designed to extract a coordinate transformation that separates an n-dimensional system

into fast and slow components. The approach relies on evaluating the vector field at a large set of points in the domain and constructing candidate bases capable of revealing directional differences in the magnitudes of the system’s directional derivatives. These bases are then filtered according to the geometric and dynamical criteria to select those that best capture the local anisotropy of the vector field.

In brief, the algorithm proceeds by (i) sampling a large number of linearly independent vectors, (ii) computing the mean behavior of the vector field across these points, (iii) identifying a subset (“control set”) where the vector field norm exceeds the average level, (iv) constructing basis matrices from this subset, (v) selecting the “reference” bases whose determinant magnitude exceeds the global average, and (vi) analyzing the eigenstructure of the corresponding directional derivative matrices. The eigenvectors associated with the largest spectral gap provide the decomposition of the system into its fast and slow directions. The original system can then be rewritten in this new coordinate frame, yielding the desired fast–slow representation.

This summary outlines only the conceptual workflow. A complete description of all algorithmic steps and mathematical derivations, including the theoretical justification and computational considerations that underlie this method, appears in [23], where the method was first introduced.

Comment: Given that the original formulation includes explicit time-dependent pulses, the system is non-autonomous and cannot be processed directly by the SPVF algorithm. To enable the use of SPVF, we first convert the model into an autonomous surrogate using the procedure detailed in Appendix C. This process preserves the cumulative therapeutic effect.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Effects of the Immune Cascade on Tumor Dynamics

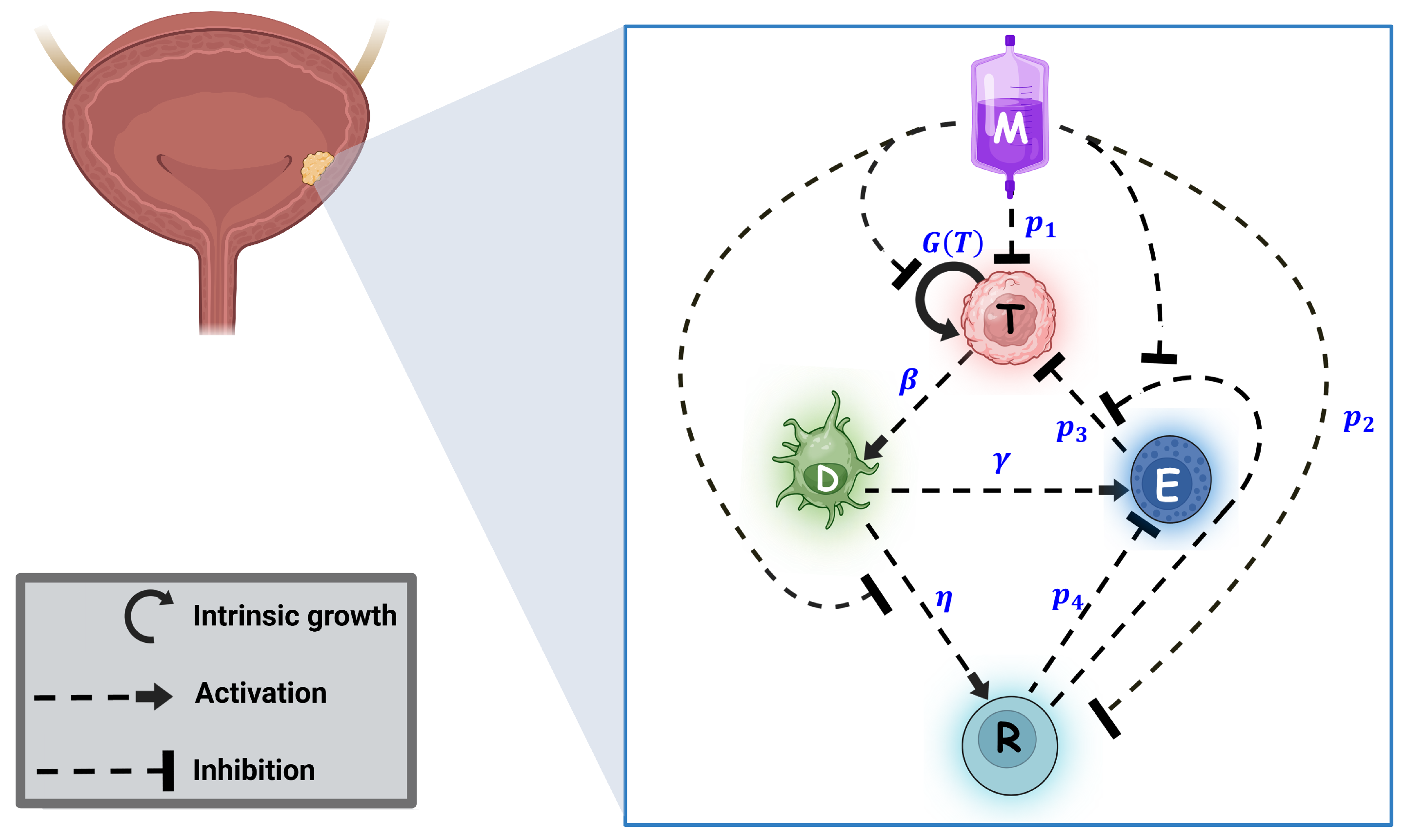

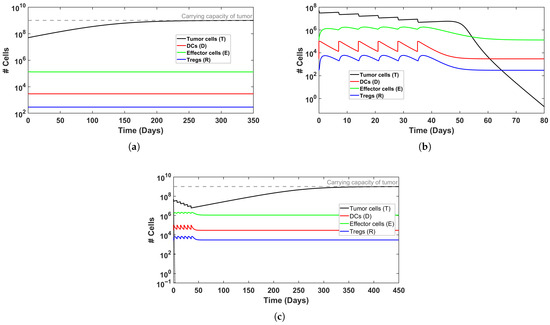

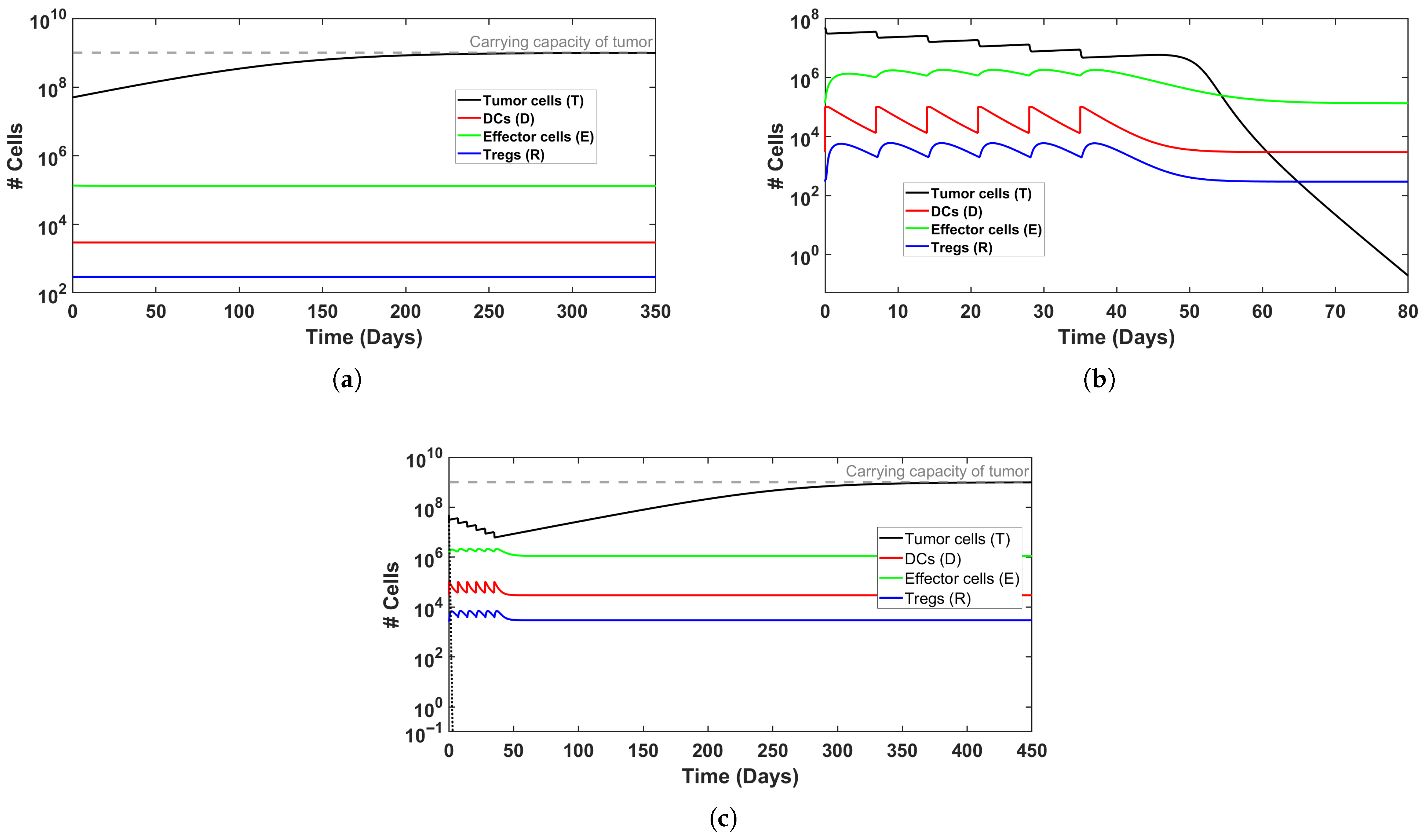

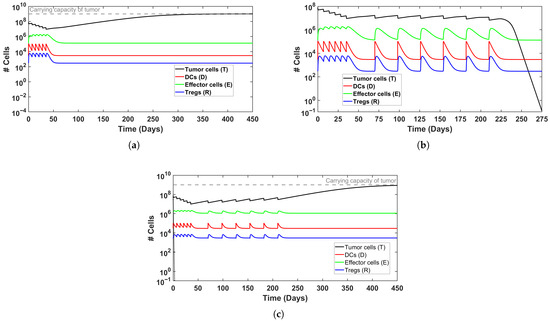

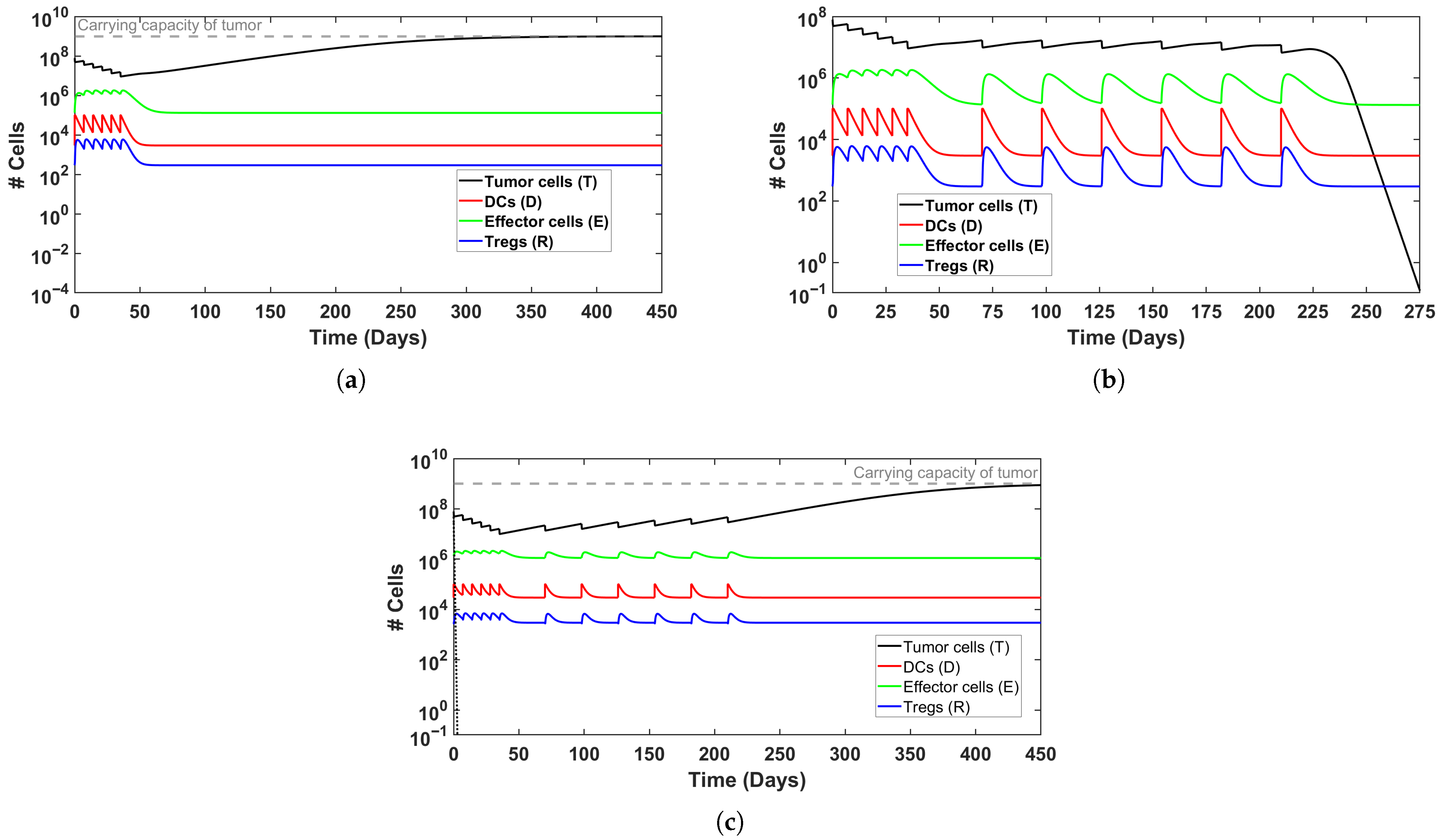

To explore the system’s behavior under different scenarios of immune activation, we examined representative cases of treatment outcomes, illustrated in Figure 1 and Figure 2. In Figure 2, induction therapy reduces the tumor burden from to <1 within 80 days (see Figure 2b), whereas in the baseline condition in which no treatment is applied (Figure 2a), the tumor continues to grow until it attains the carrying capacity, k. In Figure 3, induction therapy alone is insufficient (Figure 3a), but the addition of maintenance therapy leads to tumor elimination (Figure 3b). Taken jointly, these results demonstrate that treatment intensity is a significant determinant of therapeutic success. Notably, when the baseline level of DCs is elevated, though still within the physiological range, the outcome of applying induction and maintenance reverses for the above cases (Figure 2c and Figure 3c), resulting in tumor persistence. This behavior likely reflects the enhanced influence of Tregs cells at higher DC levels. The support for this claim can be found in the dashed black lines in Figure 2c and Figure 3c, where the exclusion of Tregs cells from the regulation term, , results in tumor cell clearance within the first week of treatment. Collectively, these findings suggest that the efficacy of both therapy and immune activation is inherently limited by the system’s composition and parameter balance. From a biological perspective, these results might be explained as an excessive activation that does not necessarily enhance immune efficacy. In other words, this may be viewed as tumor immune escape. Strong activation of DCs, therefore, may induce the expansion of Tregs to modulate the immune response in a negative feedback loop (see, for example, [51]). This might be interpreted as a possible mechanism by which cancer evades immune killing.

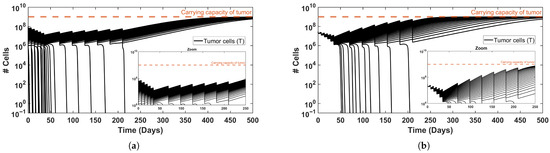

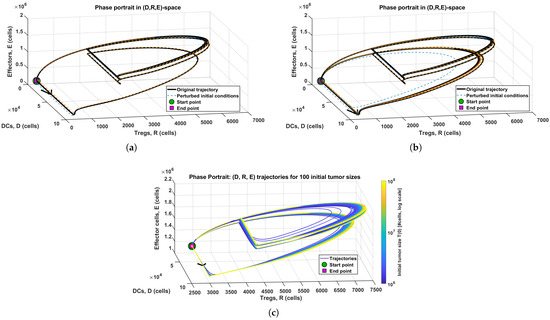

To further characterize the oscillatory regimes observed in panel (b) of Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4, we visualize this behavior in Figure 5 by plotting the corresponding numerical trajectories in the -phase space. For each parameter set, the solution is shown in the -space, with the beginning and end of the simulation interval explicitly marked and a small arrow indicating the direction of motion. Because the model is non-autonomous, driven by the time-dependent treatment pulses, the resulting curves must be interpreted as time-parametrized trajectories of a periodically forced system. They do not constitute classical limit cycles of an autonomous flow since the vector field explicitly depends on time. Nevertheless, the phase–space plots exhibit a recurrent, closed pattern in the -projection, demonstrating robust immune oscillations generated by the pulsing protocol. Additional simulations with perturbed initial conditions show that all trajectories initiated across a wide range of tumor sizes rapidly collapse onto the same oscillatory manifold and remain confined to it for long times. This behavior indicates that the recurrent pattern behaves as a strongly attracting, pulse-driven periodic orbit.

Of note, for alternative parameter combinations within the biologically feasible range, such as slower tumor growth rates or lower initial tumor counts, complete tumor elimination can still occur (see the interplay of each factor in Figure 4). These results are consistent with our previous work [7], where the growth rate and initial tumor size gradually shape tumor burden, reflecting the heterogeneity of patients reported in the literature [4,36]. Unlike our previous approach, where gradual increases in immune intensity led to tumor elimination, the current analysis reveals a non-trivial mechanism whereby increased DC levels can reverse the anti-tumor effect. Furthermore, while drug administration was previously modeled as continuous, here we simulate pulsed treatments, allowing us to assess the number of doses required to reduce tumor burden below the theoretical threshold of a single tumor cell. Treatment schedules and durations follow standard protocols, enabling us to first examine existing dynamics and gain mechanistic insight at this level.

Figure 2.

Simulated time evolution of BC growth, without and with MMC treatment, for a ‘model patient’. Tumor cells are represented by a black line and are referenced on the left y-axis. (a) Untreated BC. (b) Induction therapy (6 weeks) successfully eliminates tumor burden. (c) Elevated DC production () prevents tumor clearance despite treatment. See Table 3 for initial conditions.

Figure 2.

Simulated time evolution of BC growth, without and with MMC treatment, for a ‘model patient’. Tumor cells are represented by a black line and are referenced on the left y-axis. (a) Untreated BC. (b) Induction therapy (6 weeks) successfully eliminates tumor burden. (c) Elevated DC production () prevents tumor clearance despite treatment. See Table 3 for initial conditions.

Figure 3.

Simulated time evolution of BC growth with MMC treatment, for a ‘model patient’. (a) Non-successful induction therapy (6 weeks); (b) induction and maintenance treatment therapy successfully eliminates tumor burden; (c) elevated DC production () prevents tumor clearance despite induction and maintenance treatment. Initial conditions can be found in Table 3.

Figure 3.

Simulated time evolution of BC growth with MMC treatment, for a ‘model patient’. (a) Non-successful induction therapy (6 weeks); (b) induction and maintenance treatment therapy successfully eliminates tumor burden; (c) elevated DC production () prevents tumor clearance despite induction and maintenance treatment. Initial conditions can be found in Table 3.

Figure 4.

Effect of variations in (a) tumor growth rate, r, and (b) initial tumor size, , on tumor dynamics. Increased values of each one shift the dynamics from tumor elimination to tumor persistence. A zoom-in view is included to enhance visualization. Parameters and initial conditions are specified in Table 3.

Figure 4.

Effect of variations in (a) tumor growth rate, r, and (b) initial tumor size, , on tumor dynamics. Increased values of each one shift the dynamics from tumor elimination to tumor persistence. A zoom-in view is included to enhance visualization. Parameters and initial conditions are specified in Table 3.

Figure 5.

Three-dimensional trajectories corresponding to the reference simulations (solid black curves), together with trajectories initiated from moderately perturbed initial states (dashed curves). (a) Induction treatment only, corresponding to the baseline initial condition from Figure 2b. (b) Full treatment protocol, corresponding to the baseline initial condition from Figure 3b. (c) Variation in initial tumor size, generated from the simulation set underlying Figure 4b. Across all panels, the trajectories trace a recurrent, pulse-driven oscillatory path in the ()-space that remains robust to perturbations of the initial state and to changes in the treatment protocol.

Figure 5.

Three-dimensional trajectories corresponding to the reference simulations (solid black curves), together with trajectories initiated from moderately perturbed initial states (dashed curves). (a) Induction treatment only, corresponding to the baseline initial condition from Figure 2b. (b) Full treatment protocol, corresponding to the baseline initial condition from Figure 3b. (c) Variation in initial tumor size, generated from the simulation set underlying Figure 4b. Across all panels, the trajectories trace a recurrent, pulse-driven oscillatory path in the ()-space that remains robust to perturbations of the initial state and to changes in the treatment protocol.

5.2. Using the SPVF Method to Derive Equilibrium Points

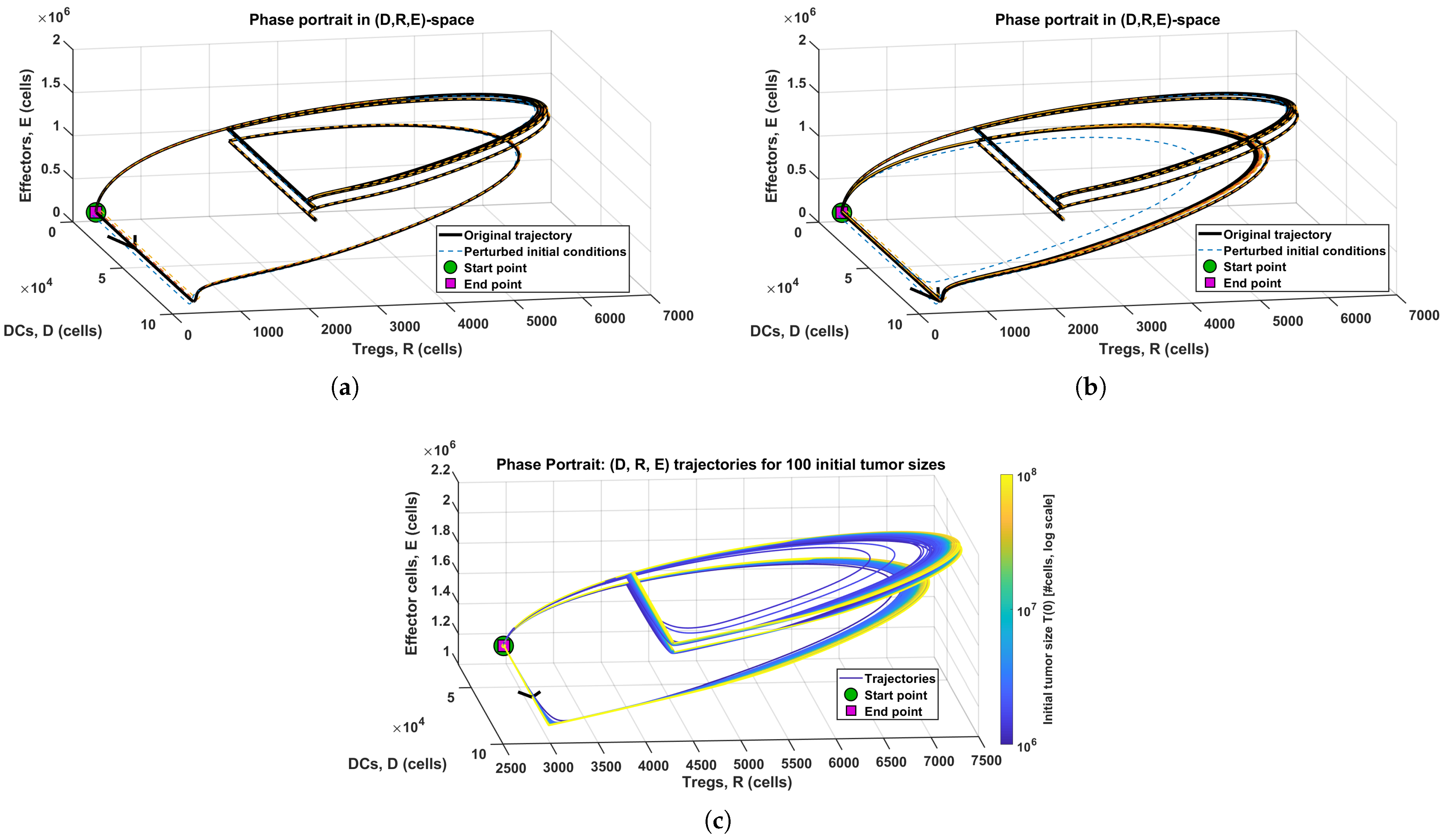

Nonlinear biological systems often lack analytical solutions, making it difficult to rigorously assess their inherent dynamics. In our model of tumor growth and immune cell interactions in response to MMC chemotherapy, simulations provide qualitative insights into treatment success or failure. Nevertheless, this does not guarantee that observed behaviors reflect the fundamental properties of the system. To address this issue, we apply the SPVF method, which enables us to find equilibria and perform stability analysis by the examination of eigenvalues to identify locally stable equilibria. The overall workflow is outlined schematically in Figure 6, illustrating the transition from the dynamical system to its equilibria. By combining stability analysis with this conceptual framework, the method provides a mathematically grounded basis for interpreting the dynamical behavior and supporting conclusions drawn from simulations.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation to describe the application of the SPVF method to the current model. The purpose is to identify equilibrium points that capture the dynamic biological processes in a manner analogous to a fixed-slide snapshot. This image was created with BioRender.com. The chemical structure of MMC was retrieved from PubChem [52].

Figure 6.

Schematic representation to describe the application of the SPVF method to the current model. The purpose is to identify equilibrium points that capture the dynamic biological processes in a manner analogous to a fixed-slide snapshot. This image was created with BioRender.com. The chemical structure of MMC was retrieved from PubChem [52].

5.2.1. The Application of the SPVF Method

Using the SPVF method, we obtain the following eigenvalues:

Following the algorithm, the maximum gap is . This implies that the original system can be decomposed into fast and slow subsystems, where the fast directions of the system are in the directions of the eigenvectors and that correspond to the eigenvalues and . The corresponding eigenvectors are

The computed eigenvalues and eigenvectors demonstrate the hierarchical organization of the system in the new coordinate presentation. The fast direction of the system is in a parallel direction to the eigenvector . Then, the slower direction is parallel with the eigenvector , and so on, following the ascending order of the eigenvalues . The slow directions of the system are parallel to the eigenvectors in ascending order, where is the slowest direction of the system.

The next step is to transform system using the above eigenvectors. Thus, by expressing these eigenvectors in matrix form, the new system variable can be represented as

Here, t denotes the transpose operation, i.e., each eigenvector is arranged as a row in the above matrix.

For clarity, we rewrite the above system in matrix form and denote this matrix as , the vectors of the variables of the original system as , and the vector of the new variables as . Accordingly, we can rewrite system (6) in the following form:

The subsequent step involves representing the old variables as functions of the new variables. To achieve this, we multiply the system of Equation (7) by the inverse matrix of

In order to represent the system in the new coordinates, we differentiate it with respect to time, i.e.,

and substitute the right-hand side expressions from the original system (1) instead of in (9):

where

is the RHS of system (1). Substituting Equation (8) into Equation (10) yields the model in the new coordinates, with the initial conditions given by

The decomposition of the model into fast and slow subsystems can be found in Appendix D. It is important to emphasize that this approach does not yield an explicit temporal hierarchy among the original model variables but only among the transformed variables of the new system. In this sense, the hidden hierarchy emerges only in the new coordinates and not in the original variables. The decomposition is therefore employed solely as a means of determining the equilibrium points of the original model.

5.2.2. Stability Analysis of the Model

Here, we examine the stability of the model after it has been decomposed into fast and slow subsystems. The procedure below is used to find the fixed points in the new coordinates and determine their stability.

- Substitute the slow variables as constants into the fast subsystem (one can take the initial condition of the slow variables as the constants).

- Set the derivatives of all fast variables to zero, i.e., solve the fast subsystem (with slow variables as constants) and find the equilibrium points of the fast variables :Here, fast equilibrium points are indicated with a star superscript. In this case, there are two equations for the two unknowns and .

- Substitute the equilibrium points from step 2 into the slow subsystem, then solve it to obtain the equilibrium points of the slow variables .This formulation results in three equations that determine the values of the three slow variables .

- Use the equilibrium values from steps 2 and 3 to evaluate the Jacobian matrix of the full system (i.e., the model expressed in the new coordinates).

- Compute the eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix of the model at the new coordinates for each set of equilibrium points (the stable points are those with a negative real part of the eigenvalues).

- Transform only the equilibrium points that are stable from steps 2 and 3 to the original coordinates using the inverse matrix of the eigenvectors, i.e., computewhere i indicates for different stable equilibrium points.

It should be highlighted here that the equilibrium points obtained in the new coordinate system are functions of both the parameters of the original model and the initial conditions of the transformed system, i.e.,

Comment 1: the initial condition as well as the equilibrium points are biologically meaningless as there is no biological significance to the variables in the new coordinates. Therefore, in order to understand the biological meaning of the above results, we should transform these points to the original coordinates using the inverse matrix of the eigenvectors .

Comment 2: Since the eigenvalues are invariant under change of coordinates, the stability equilibrium points will be remain stable equilibrium points at the original coordinates.

By applying steps 1–6, it is possible to find a stable equilibrium point expressed in the original coordinates as a function of the parameters of the original model and the initial conditions at the new coordinates (Further details are provided in Appendix D, and the full computation was performed in MATLAB).

As we have mentioned before, this equilibrium point is stable since the eigenvalues are invariant under change of coordinates.

In order to complete writing the stable equilibrium points in the original system, we write the initial conditions as a function of the original initial conditions using the matrix as or in an explicit form

To demonstrate the clinical relevance of this analysis and to validate the theoretical predictions, we examine two virtual patients representing different risk categories.

5.2.3. Clinical Validation Through Virtual Patient Analysis

To validate the theoretical predictions of the SPVF stability analysis and demonstrate their clinical relevance, we examine two virtual patients representing distinct risk categories based on initial tumor burden. These patients serve as concrete test cases for evaluating whether the mathematically derived equilibrium points correspond to clinically meaningful outcomes observed in simulations.

Patient definitions: Virtual Patient I has a low-risk disease with an initial tumor burden of cells (corresponding to approximately 2.8 cm tumor diameter), while Virtual Patient II has high-risk disease with cells (approximately 5.9 cm diameter). These tumor sizes were calculated using the diameter-to-cell-count conversion formula established in our previous work [7], and the risk stratification follows clinical criteria from [53], where tumors larger than 3 cm are associated with significantly higher recurrence rates and poorer prognosis. Although initial tumor burdens share the same order of magnitude ( cells), this small difference places the patients on opposite sides of a critical clinical threshold, making them ideal candidates for testing the model’s sensitivity to initial conditions.

Table 4 presents the stable equilibrium points for both patients under two treatment regimens: (i) induction therapy alone (6 weekly intravesical instillations), and (ii) combined induction and maintenance therapy (6 weekly instillations followed by 6 monthly instillations).

The eigenvalues for the equilibrium points in Table 4, as they appear in the new coordinates, are listed in Table 5. All four equilibrium points exhibit eigenvalues with negative real parts, indicating that they are locally stable.

Table 4.

Stable equilibrium points for virtual patients under different treatment regimens.

Table 4.

Stable equilibrium points for virtual patients under different treatment regimens.

| Virtual Patient | Ind. | Maint. | * | * | * | * | * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | ✓ | x | 27.296 | 3.393 × 104 | 1.184×103 | 5.0 × 104 | 768.011 |

| ✓ | ✓ | 54.612 | 0.292 | 2.951 × 103 | 1.344 × 105 | 16.961 | |

| II | ✓ | x | 27.280 | 8.488 × 104 | 1.52 × 103 | 6.433 × 104 | 1.11 × 103 |

| ✓ | ✓ | 54.608 | 4.157 × 103 | 5.26 × 103 | 1.969 × 105 | 3.021 × 103 |

Ind. = Induction phase of treatment (6-weekly treatments), Maint. = Maintenace phase of treatment (6-weekly treatments).

Table 5.

Summary of eigenvalues corresponding to the stable equilibrium points of the system.

Table 5.

Summary of eigenvalues corresponding to the stable equilibrium points of the system.

| Virtual Patient | |

|---|---|

| I-Ind. only | |

| I-Ind.+ Maint. | |

| II-Ind. only | |

| II-Ind. + Maint. |

Validation of simulation results: These equilibrium predictions provide rigorous mathematical validation for the qualitative behaviors observed in the full system simulations (Section 5.1). For Patient I, the predicted equilibria match the long-term asymptotic behavior in Figure 3a,b: induction alone leaves residual disease, while maintenance achieves elimination. For Patient II, the equilibrium analysis confirms that even aggressive treatment cannot overcome the imbalance created by the higher initial tumor burden as observed in Figure 4b. Another possible explanation is that the elevated Treg count leads to immunosuppression and treatment failure, even though effector cell count is higher in the maintenance case (similar to Figure 3c).

6. Conclusions

We developed a five-equation mathematical model that captures the multiscale dynamics of MMC chemotherapy in BC, explicitly resolving DCs, effector T cells, and Tregs. This framework extends our previous work [7] by incorporating immune cell heterogeneity and implementing clinically realistic treatment schedules through periodic drug administration via Heaviside step functions. The resulting nonlinear system exhibits hidden multiscale complexity, which we analyzed using the Singularly Perturbed Vector Field (SPVF) method to decompose the dynamics into fast and slow subsystems, thereby facilitating stability analysis.

Our simulations reproduce several established clinical observations. First, treatment outcome depends critically on the initial tumor burden and intrinsic growth rate-findings consistent with the prognostic factors reported in the literature [36,53]. Second, the intensity of treatment shapes tumor control, but immune dynamics also plays a significant role [37,54]. Third, the model demonstrates that MMC can reverse Treg-mediated immunosuppression, thereby enhancing the activity of effector cells. Most notably, our analysis reveals a counterintuitive phenomenon: elevated DC production within the physiological range can precipitate treatment failure rather than enhance tumor clearance. This paradoxical outcome arises because increased DC activation amplifies Treg recruitment and activity, which in turn suppresses effector cell function through both direct inhibition (reducing effector cell counts) and indirect mechanisms (attenuating their tumor-killing capacity). We term this the “Janus-faced” behavior of DCs—the same cells that prime anti-tumor immunity also drive regulatory feedback loops that enable immune escape. This non-monotonic relationship between DC levels and therapeutic efficacy challenges the assumption that immune activation universally improves outcomes, suggesting that balanced immunomodulation, rather than maximal activation, may be critical for successful therapy. To date, this Janus-faced DC-behavior has not been validated in clinical bladder-cancer settings, and thus offers a concrete direction for future investigation.

The model recapitulates several recognized hallmarks of cancer [55], including sustained proliferation, resistance to cell death, and immune evasion. Logistic growth combined with MMC-induced growth arrest captures the cytostatic effects of the drug through a saturating Michaelis–Menten term. Immune escape emerges naturally from nonlinear regulatory feedback: when DC levels rise, Treg-mediated suppression overwhelms effector responses, even in the presence of MMC-induced immunomodulation. These dynamics align with experimental observations showing variable patient responses to MMC therapy [1,54]. Importantly, our simulations align with experimental findings suggesting that MMC may reverse immune suppression [11]. Yet, here we show that this mechanism might be disrupted by increased DC counts, which later accentuate Tregs activation, underscoring the variability of patient-specific responses. Related mathematical-oncology studies likewise highlight the analytical complexity of modeling tumor–immune interactions, which in turn has been leveraged to illuminate unresolved biological aspects of these dynamics [56,57,58,59].

While the current framework simplifies the broader process of tumor development and response to MMC chemotherapy, it provides a mechanistic foundation that reproduces key experimental observations. Since model parameters were derived from a combination of cell line experiments, animal models, and clinical data, caution should be exercised when interpreting the quantitative predictions. Therefore, the present work remains within the theoretical domain and serves as a conceptual foundation rather than a direct clinical tool. Future extensions of the model will focus on integrating biological pathways to better represent tumor evolution and resistance, ultimately guiding the development of simulation-based, adaptive treatment planning tools.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B.-M. and M.Y.; methodology, M.Y., S.B.-M. and O.N.; software, M.Y. and O.N.; validation, M.Y. and S.B.-M.; formal analysis, M.Y.; investigation, M.Y.; data curation, M.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Y. and S.B.-M.; writing—review and editing, M.Y. and S.B.-M.; visualization, M.Y.; supervision, S.B.-M.; project administration, S.B.-M.; funding acquisition, M.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Sarel Halachmi of the Bnai Zion Medical Center in Haifa for the helpful information and fruitful discussions. Graphical figures (Figure 1 and Figure 5) were created using BioRender.com.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MMC | Mitomycin-C |

| NMIBC | Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer |

| SPVF | Singularly Perturbed Vector Field |

| DCs | Dendritic cells |

| CTLs | Cytotoxic T-cells |

| Tregs | Regulatory T-cells |

Appendix A. Model Details

Appendix A.1. Reference Table

This subsection presents a quick reference table describing each term used in the model equations.

Table A1.

Equation descriptions.

Table A1.

Equation descriptions.

| ODE | Term | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Washout of MMC | ||

| MMC instillations | ||

| Tumor growth in response to MMC | ||

| MMC-induced tumor cell death | ||

| Effector cell-mediated tumor death with reversal of Treg inhibition by MMC | ||

| Homeostatic production of DCs | ||

| Death of DCs | ||

| Activation of DCs by MMC-induced dying tumor cells | ||

| Activation of CTLs by DCs | ||

| Death of effector T-cells | ||

| Inhibition of effector T-cells by Tregs | ||

| Tregs activation by DCs and its inhibition by MMC | ||

| Death of Tregs | ||

| MMC-induced Tregs death |

Appendix A.2. Estimation of Parameters

- MMC dosage

In our previous model [7], we derived the standard single MMC instillation dose of 40 mg in 50 mL sterile water, given by the value of 2395 [M]. Here, rather than assuming a hypothetical long-term administration, we calculate the drug instillation rate by implementing the actual 2 h ( day) intravesical infusion:

- Killing rate of tumor cells by MMC

Oresta et al. [33] reported that treatment with 75 M resulted in MMC-induced death (specifically apoptosis) in approximately 50% of tumor cells in all the examined BC cell lines at 48 h, measured after an initial treatment of 1 h. These data provide the closest available schedule to the clinical chemotherapy regimen, which typically involves a 2 h instillation for the NMIBC treatment. We then assume that the maximum rate of MMC-induced death in the Michaelis–Menten killing term is 99% of cells per time unit. The time unit is set to 2 days to be adequate for the experiment and the corresponding half-saturation constant. The maximum fractional kill rate per unit time was estimated assuming exponential decay, yielding a rate constant of

This approach is supported by [60], which provides evidence that a population of 1–7% of resistant cancer stem cells exhibits resistance to MMC treatment in cell line experiments.

- Half saturation constant of MMC

We updated the previous parameter value of [7] by incorporating estimates of reported by Oresta et al. [33], in accordance with the derivation of :

- Production rate of DCs

Separating the variables representing the DCs and effector cell types, which were previously combined in our earlier model [7], demands the derivation of a specific death rate for each cell type. The replenishment rate of DCs must remain consistent with their expected order of magnitude and below the postulated carrying capacities of DCs and effector cells, estimated to be and , respectively (see Supplementary Information of Yosef et al. [7] for the corresponding value ranges). Under these circumstances, we replace the previous value of by

- Death rate DCs

Chen et al. pointed out that the DCs half-life is about two days [43]. Assuming exponential decay kinetics, this yields a mortality rate of

- Death rate of effector cells

de Pillis et al. [47] accounted the reported human data, using values of and . A similar value of was used in the work of Kronik et al. [46]. Therefore, we use the range of (0.168–9.12) .

- Carrying capacity of DCs

In the supplementary information of our previous work [7], we discussed studies on murine and orthotopic models of bladder tissue in both healthy and cancerous states, with magnitudes ranging from to [13,45]. Based on these findings, the carrying capacity of the DCs is taken to be

- Tregs inhibition by MMC

Data from mouse experiments by Hori et al. (see S5 Table in [11]) showed a significant reduction in Tregs within BC tissues after a 2 h weekly treatment of MMC (200 ) for 4 weeks. Specifically, the Tregs counts decreased from to . Assuming an exponential decay with days, the corresponding rate is

Appendix B. Sensitivity Analysis

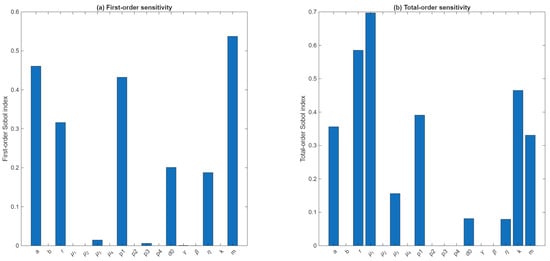

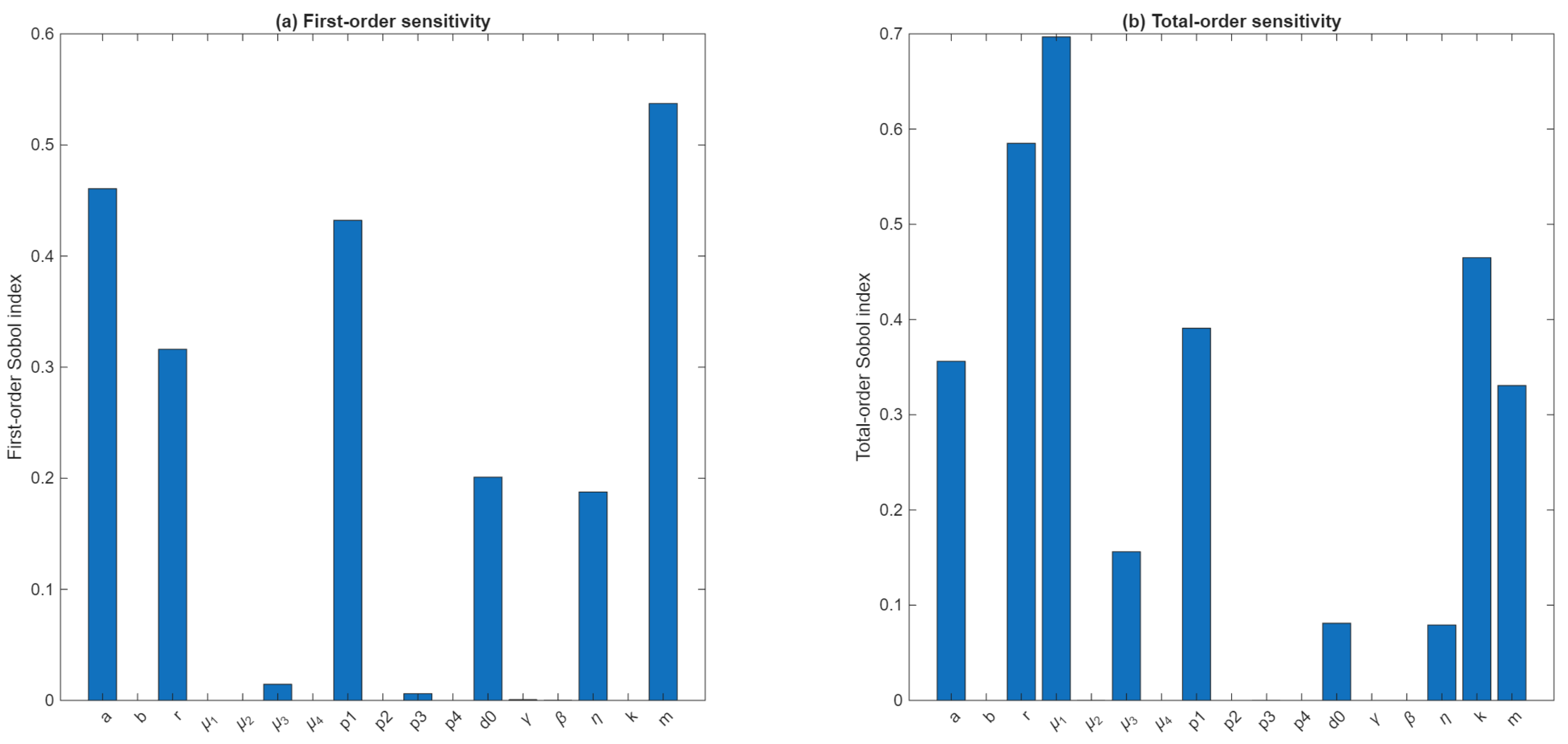

To quantify the relative influence of all biological and treatment-related parameters on tumor burden under the full non-autonomous pulsed protocol, we performed a variance-based Sobol global sensitivity analysis. Sobol indices decompose the output variance into contributions attributable to each input parameter alone (first-order indices) and to all higher-order interactions between parameters (total-order indices), providing a global measure of influence over the entire parameter domain rather than only in a neighborhood of a nominal value. This approach is widely used for nonlinear biological models and is consistent with the established sensitivity-analysis methodology [61,62,63].

Appendix B.1. Model Output (QoI)

The quantity of interest (QOI) is defined as

where denotes the tumor cell count at the final simulated day of the treatment protocol. In our implementation, the model executes—an induction phase (6 weekly pulses; days 0–42), and—a maintenance (weeks 7–31). The last session ends at day 210 with an additional 2 h pulse, yielding a final simulation time of day . Accordingly, is the tumor load evaluated at this final timepoint. The log transformation avoids singularities as tumor burden approaches zero and reduces numerical skew.

Appendix B.2. Parameter Sampling and Bounds

All model parameters were included in the analysis:

To ensure biological plausibility and numerical stability, sampling ranges were chosen as follows. For parameters with experimentally grounded ranges, we used published biologically feasible intervals (Table 2). For parameters lacking such information, we used a symmetric scaling window of half to twice their baseline value.

Sobol matrices A and B of size were generated via uniform random sampling across these bounds, yielding a total of = 19,000 model evaluations.

Appendix B.3. Simulation Protocol and Numerical Considerations

Each sampled parameter vector was run through the full non-autonomous pulsed regimen, reproducing all pulse timings, off-intervals, and conditional maintenance-phase pulses. ODEs were solved with ode23s using moderate tolerances (AbsTol = 1 × 10−8, RelTol = 1 × 10−5). Time-outs and solver failures were captured via try/catch blocks to ensure robustness.

Appendix B.4. Computation of Sobol Indices

First-order () and total-order () indices were computed using the classical Jansen estimators [61,62,63]

Appendix B.5. Sensitivity Results

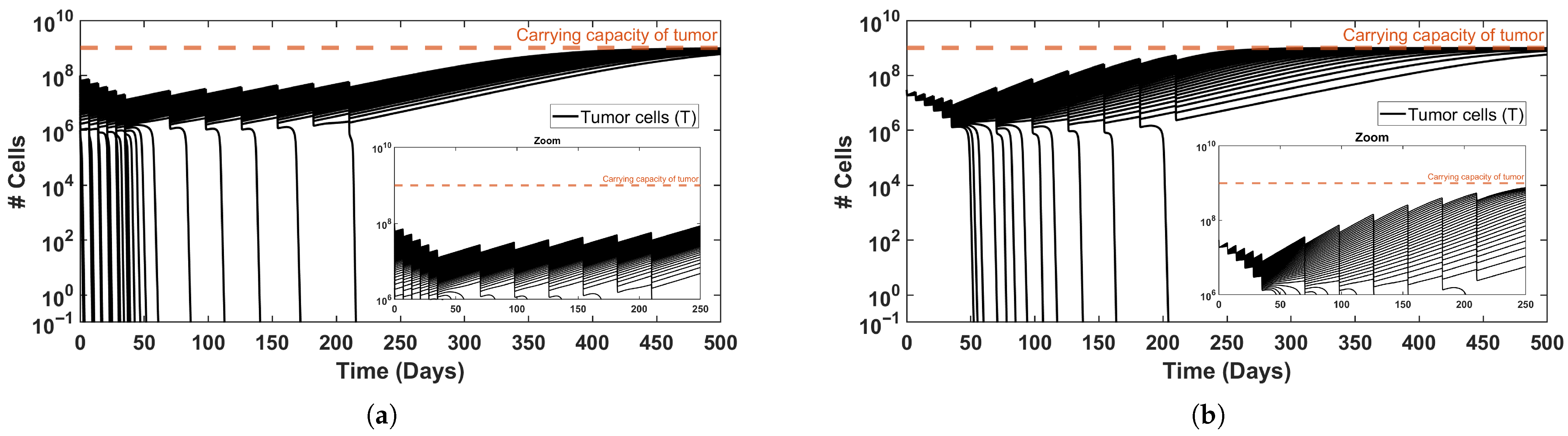

Figure A1 displays the resulting indices. The dominant parameters—those contributing most strongly to variance in tumor burden—were

- Total-order sensitivity:

- First-order sensitivity:

Several parameters (e.g., ) exhibited negligible first-order effects but nonzero total-order effects, indicating that they influence tumor burden primarily through nonlinear interactions rather than direct main effects-consistent with typical behavior in high-dimensional immunological ODE models.

Figure A1.

Sobol global sensitivity indices for the tumor-burden Qol. (a) First-order Sobol indices and (b) total-order indices computed for all 17 model parameters using 1000 Sobol sample pairs. The Qol is defined as , where is the tumor load at the end of treatment. Parameters , and show the largest first-order effects, while , and k display dominant total-order contributions, indicating strong interaction-driven sensitivity.

Figure A1.

Sobol global sensitivity indices for the tumor-burden Qol. (a) First-order Sobol indices and (b) total-order indices computed for all 17 model parameters using 1000 Sobol sample pairs. The Qol is defined as , where is the tumor load at the end of treatment. Parameters , and show the largest first-order effects, while , and k display dominant total-order contributions, indicating strong interaction-driven sensitivity.

In particular, the largest total-order sensitivities were associated with the drug-modulator decay rate , the intrinsic tumor growth rate r (), and the tumor carrying capacity . These effects arise predominantly through nonlinear interactions with other components of the system, as all three parameters have negligible first-order indices. In contrast, the drug dose amount m, the half-saturation parameter a of MMC effects, and the MMC-induced killing parameter exhibit substantial first-order effects (, respectively), indicating direct influence on tumor burden independent of interactions. Moderate contributions were also observed for , , and . Remaining parameters contributed little to overall variance.

Together, these results suggest that drug-related parameters () and tumor expansion parameters along with the drug washout rate , exert the strongest global control over tumor load at the end of treatment, while several immune-interaction rates account for only a small fraction of the variance. This highlights the importance of considering multi-parameter couplings when interpreting model behavior and calibrating treatment-related parameters.

Appendix C. Conversion of the Pulsed Non-Autonomous System into an Autonomous Form

The original model incorporates a clinically realistic sequence of drug infusions, each represented by a short Heaviside pulse of amplitude m and duration days. Because these pulses enter explicitly through a time-dependent source term , the system takes the general form

and is therefore non-autonomous. This implies that classical equilibrium analysis, Jacobian linearization, and bifurcation theory are not directly applicable because the vector field depends explicitly on time and the system has no time-independent fixed points. Furthermore, the SPVF framework also requires an autonomous formulation. To make the system analytically tractable while preserving the biological effect of the treatment protocol, we construct an autonomous surrogate system whose parameters encode the aggregate effect of the pulsed therapy.

The conversion proceeds in a sequence of mathematically well-defined steps.

- Step 1. Identifying the treatment windowLet the set of pulse start-times bewith each pulse having a duration of days. We define the total treatment window asand denote its length by

- Step 2. Replacing the pulsed drug input by an equivalent constant termEach pulse delivers total drug amount . Thus the total amount delivered during the therapy block (the cumulative amount) isWe then define the effective constant drug influxwhich yields the same cumulative drug exposure as the entire sequence of finite pulses. This corresponds to a Haber-type equivalence: a constant infusion that produces the same total area under the drug-input curve as the original pulsed schedule.

- Step 3. Measuring the treatment-induced immune activationThe pulses alter the long-term average levels of DCs, effector T cells, and Tregs. For each variable , we compute the mean value under treatment using the area under the pulsed trajectory:We also compute the corresponding baseline steady-state value (no treatment), denotedBecause pulse-induced peaks should not be inserted directly into a smooth autonomous system, we define an effective activation level that lies between the untreated level and the mean under treatment:This ensures that the surrogate dynamics remain biologically plausible, never exceeding the pulse-induced peaks and never falling below the natural baseline.

- Step 4. Constructing activation prefactorsFor each immune variable, we define a dimensionless prefactorwhich quantifies how much the treatment elevates the average level relative to the untreated baseline.These prefactors modify the biologically meaningful parameters describing immune activation:Here governs DC-driven tumor–immune interactions, determines effector activation by DCs, and controls Treg stimulation-each of which is strongly influenced by therapy-induced immune activity.

- Step 5. The resulting autonomous surrogate systemThe autonomous surrogate model replaces m (with and replaces the activation parameters by their effective values. All other mechanistic components of the biological model remain unchanged. The resulting ODE system iswhere is identical to the original right-hand side except for the substitutionsThis system is now autonomous.

By eliminating the explicit time dependence, the surrogate system satisfies all assumptions needed for standard analytical tools. Steady states are well-defined as solutions of

Their stability can be characterized by the eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix

The model also becomes suitable for the application of the SPVF framework, providing a rigorous description of global attractors and long-term outcomes.

This procedure converts a finite-pulse, piecewise non-autonomous immunotherapy model into a biologically consistent autonomous system by matching cumulative drug exposure and mean immune activation over the treatment course. The surrogate preserves the essential therapeutic impact of the pulses while restoring a time-independent vector field, thereby enabling full use of the SPVF analysis.

Appendix D. The Decomposition of the Model into Fast and Slow Subsystems

The original model (1), rewritten in the new coordinates as (12), exhibits the required hierarchy and can therefore be decomposed into fast and slow subsystems as follows:

where , and the initial conditions are presented for the maintenance cases in I and II of and in Table 4, respectively:

and

This decomposition allows us to focus on the fast subsystem while preserving the behavior of the full model and improving computational efficiency.

Below we provide the SPVF-transformed autonomous system employed to obtain the equilibria reported for Case I (maintenance).

For Case I (maintenance), solving the SPVF-transformed system yields the equilibrium

This vector is then mapped back to the original biological variables via

References

- Deng, T.; Liu, B.; Duan, X.; Zhang, T.; Cai, C.; Zeng, G. Systematic Review and Cumulative Analysis of the Combination of Mitomycin C plus Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) for Non–Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W.; Lee, H.H.; Park, E.Y.; Park, W.S.; Kim, S.H.; Joung, J.Y.; Chung, J.; Seo, H.K. Clinical efficacy of neoadjuvant intravesical mitomycin-C therapy immediately before transurethral resection of bladder tumor in patients with nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer: Preliminary results of a prospective, randomized phase II study. J. Urol. 2023, 209, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; Sun, Y.; Chen, X.-Y.; Kong, Q.; Zhang, K.-L.; Li, H. Apoptosis of bladder cancer cells induced by short-term and low-dose Mitomycin-C: Potential molecular mechanism and clinical implication. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2003, 11, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariat, S.F.; Chade, D.C.; Karakiewicz, P.I.; Scherr, D.S.; Dalbagni, G. Update on Intravesical Agents for Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. Immunotherapy 2010, 2, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoph, F.; Schostak, M. Age does not matter: The relevance of immediate instillation therapy with Mitomycin C in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2018, 7, 289–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malmström, P.-U.; Sylvester, R.J.; Crawford, D.E.; Friedrich, M.; Krege, S.; Rintala, E.; Solsona, E.; Di Stasi, S.M.; Witjes, J.A. An Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis of the Long-Term Outcome of Randomised Studies Comparing Intravesical Mitomycin C versus Bacillus Calmette-Guérin for Non–Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2009, 56, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yosef, M.; Bunimovich-Mendrazitsky, S. Mathematical model of MMC chemotherapy for non-invasive bladder cancer treatment. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1352065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Lu, Z.; Chao, F.; Taylor, J.A.; Au, J.L.-S. Mitomycin C induces immunogenic cell death biomarkers in human bladder tumors. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oresta, B.; Pozzi, C.; Hurle, R.; Lazzeri, M.; Faccani, C.; Colombo, P.; Elefante, G.; Casale, P.; Guazzoni, G.; Rescigno, M. Mitomycin C triggers immunogenic cell death in bladder cancer cells. J. Urol. 2019, 201, e903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, S.; Miyake, M.; Tatsumi, Y.; Morizawa, Y.; Nakai, Y.; Onishi, S.; Onishi, K.; Iida, K.; Gotoh, D.; Itami, Y.; et al. Intravesical treatment of chemotherapeutic agents sensitizes bacillus Calmette-Guérin by the modulation of the tumor immune environment. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 41, 1863–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, S.; Miyake, M.; Tatsumi, Y.; Onishi, S.; Morizawa, Y.; Nakai, Y.; Tanaka, N.; Fujimoto, K. Topical and systemic immunoreaction triggered by intravesical chemotherapy in an N-butyl-N-(4-hydroxybutyl) nitrosamine-induced bladder cancer mouse model. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhu, K.; Liu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, L.; Cui, J.; Guo, H.; Zhou, N.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; et al. Profiles of immune infiltration in bladder cancer and its clinical significance: An integrative genomic analysis. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 17, 762–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowyer, G.S.; Loudon, K.W.; Suchanek, O.; Clatworthy, M.R. Tissue immunity in the bladder. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 40, 499–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roussel, M.R.; Fraser, S.J. Geometry of the steady-state approximation: Perturbation and accelerated convergence methods. J. Chem. Phys. 1990, 93, 1072–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussel, M.R.; Fraser, S.J. Accurate steady-state approximations: Implications for kinetics experiments and mechanism. J. Phys. Chem. 1991, 95, 8762–8770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussel, M.R.; Fraser, S.J. Invariant manifold methods for metabolic model reduction. Chaos 2001, 11, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gol’dshtein, V.M.; Sobolev, V.A. Singularity theory and some problems of functional analysis. Amer. Math. Soc. 1992, 1, 73–92. [Google Scholar]

- Babushok, V.I.; Gol’dshtein, V.M. Structure of the thermal explosion limit. Combust. Flame 1988, 72, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, U.; Pope, S.B. Implementation of simplified chemical kinetics based on intrinsic low-dimensional manifolds. Symp. (Int.) Combust. 1992, 24, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, U.; Pope, S.B. Simplifying chemical kinetics: Intrinsic low-dimensional manifolds in composition space. Combust. Flame 1992, 88, 239–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongers, H.; Van Oijen, J.A.; De Goey, L.P. Intrinsic low-dimensional manifold method extended with diffusion. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2002, 29, 1371–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlin, A.S.; Whitehouse, L.; Lowe, R. The estimation of intrinsic low dimensional manifold dimension in atmospheric chemical reaction systems. In Air Pollution Modelling and Simulation: Proceedings of the Second Conference on Air Pollution Modelling and Simulation, APMS’01, Champs-sur-Marne, France, 9–12 April 2001; Sportisse, B., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; pp. 245–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nave, O. Singularly perturbed vector field method (SPVF) applied to combustion of monodisperse fuel spray. Differ. Equ. Dyn. Syst. 2019, 27, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barocas, D.A.; Globe, D.R.; Colayco, D.C.; Onyenwenyi, A.; Bruno, A.S.; Bramley, T.J.; Spear, R.J. Surveillance and treatment of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer in the USA. Adv. Urol. 2012, 2012, 421709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, C.; Brown, M.; Hayne, D. Intravesical therapies for bladder cancer–indications and limitations. BJU Int. 2012, 110, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.J.; Soloway, M.S. Office evaluation and management of bladder neoplasms. Urol. Clin. N. Am. 1998, 25, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldu, S.L.; Bagrodia, A.; Lotan, Y. Guideline of guidelines: Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. BJU Int. 2017, 119, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, D.S.; Mancera, P.F.A.; Carvalho, T.; Gonçalves, L.F. A mathematical model for chemoimmunotherapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Appl. Math. Comput. 2019, 349, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; Kunath, F.; Coles, B.; Draeger, D.L.; Krabbe, L.M.; Dersch, R.; Kilian, S.; Jensen, K.; Dahm, P.; Meerpohl, J.J. Intravesical Bacillus Calmette-Guérin versus mitomycin C for Ta and T1 bladder cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 1, CD011935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, P.; Saint, F.; Audenet, F.; Roumiguié, M.; Allory, Y.; Loriot, Y.; Masson-Lecomte, A.; Pradère, B.; Seisen, T.; Traxer, O.; et al. Recommandations du Comité de cancérologie de l’Association Française d’Urologie (CC-AFU) pour la bonne pratique des instillations intravésicales de mitomycine C, d’épirubicine et de BCG pour le traitement des tumeurs de la vessie n’infiltrant pas le muscle (TVNIM). Prog. Urol. 2022, 32, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joice, G.A.; Bivalacqua, T.J.; Kates, M. Optimizing pharmacokinetics of intravesical chemotherapy for bladder cancer. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2019, 16, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalton, J.T.; Wientjes, M.G.; Badalament, R.A.; Drago, J.R.; Au, J.L. Pharmacokinetics of intravesical mitomycin C in superficial bladder cancer patients. Cancer Res. 1991, 51, 5144–5152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oresta, B.; Pozzi, C.; Braga, D.; Hurle, R.; Lazzeri, M.; Colombo, P.; Frego, N.; Erreni, M.; Faccani, C.; Elefante, G.; et al. Mitochondrial metabolic reprogramming controls the induction of immunogenic cell death and efficacy of chemotherapy in bladder cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eaba6110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignali, D.A.A.; Collison, L.W.; Workman, C.J. How regulatory T cells work. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dePillis, L.; Caldwell, T.; Sarapata, E.; Williams, H. Mathematical Modeling of Regulatory T Cell Effects on Renal Cell Carcinoma Treatment. Discret. Contin. Dyn. Syst. B 2013, 18, 915–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loloi, J.; Allen, J.L.; Schilling, A.; Hollenbeak, C.; Merrill, S.B.; Kaag, M.G.; Raman, J.D. World Bladder Tumors: Size Does Matter. Bladder Cancer 2020, 6, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, M.; Enting, D. Immune responses in bladder cancer-role of immune cell populations, prognostic factors and therapeutic implications. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Jiang, A. Dendritic cells and CD8 T cell immunity in tumor microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatogai, K.; Sweis, R.F. The tumor microenvironment of bladder cancer. In Tumor Microenvironments in Organs: From the Brain to the Skin—Part B; Birbrair, A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, R.A.; von Andrian, U.H. How tolerogenic dendritic cells induce regulatory T cells. In Advances in Immunology; Alt, F.W., Austen, K.F., Honjo, T., Melchers, F., Uhr, J.W., Unanue, E.R., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; Volume 108, pp. 111–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskovitz, B.; Meyer, G.; Kravtzov, A.; Gross, M.; Kastin, A.; Biton, K.; Nativ, O. Thermo-chemotherapy for intermediate or high-risk recurrent superficial bladder cancer patients. Ann. Oncol. 2005, 16, 585–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunimovich-Mendrazitsky, S.; Shochat, E.; Stone, L. Mathematical model of BCG immunotherapy in superficial bladder cancer. Bull. Math. Biol. 2007, 69, 1847–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Wang, J. Programmed cell death of dendritic cells in immune regulation. Immunol. Rev. 2010, 236, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, A.; Lai, X. Combination therapy for cancer with oncolytic virus and checkpoint inhibitor: A mathematical model. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senserrich, J.; Guallar-Garrido, S.; Gomez-Mora, E.; Urrea, V.; Clotet, B.; Julián, E.; Cabrera, C. Remodeling the bladder tumor immune microenvironment by mycobacterial species with changes in their cell envelope composition. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 993401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronik, N.; Kogan, Y.; Elishmereni, M.; Halevi-Tobias, K.; Vuk-Pavlović, S.; Agur, Z. Predicting outcomes of prostate cancer immunotherapy by personalized mathematical models. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e15482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Pillis, L.G.; Gu, W.; Radunskaya, A.E. Mixed immunotherapy and chemotherapy of tumors: Modeling, applications and biological interpretations. J. Theor. Biol. 2006, 238, 841–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kogan, Y.; Foryś, U.; Shukron, O.; Kronik, N.; Agur, Z. Cellular immunotherapy for high grade gliomas: Mathematical analysis deriving efficacious infusion rates based on patient requirements. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 2010, 70, 1953–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippov, A.F. Differential Equations with Discontinuous Righthand Sides; Springer Dordrecht: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coddington, E.A.; Levinson, N. Theory of Ordinary Differential Equations; McGraw–Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Cools, N.; Ponsaerts, P.; Van Tendeloo, V.F.I.; Berneman, Z.N. Regulatory T Cells and Human Disease. J. Immunol. Res. 2007, 2007, 89195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Compound Summary for CID 5746, Mitomycin C. PubChem 2025. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Mitomycin-C (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Suh, J.; Jung, J.H.; Kwak, C.; Kim, H.H.; Ku, J.H. Stratifying risk for multiple, recurrent, and large (≥3 cm) Ta, G1/G2 tumors in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Investig. Clin. Urol. 2021, 62, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]