Abstract

This study addresses a critical gap in Energy-Efficient Permutation Flow Shop Scheduling (EPFSP) by integrating the often-overlooked time-accumulative equipment degradation inherent in practical manufacturing. This research formalizes and solves the EPFSP with machine deterioration (EPFSP-DEM), aiming to simultaneously minimize the makespan and total energy consumption. To achieve this objective, this study proposes a Diversity-Constrained Imperialist Competitive Algorithm (DCICA) featuring several novel mechanisms. In DCICA, a differentiated assimilation is developed to improve diversity of the population; a knowledge-guided revolution is designed to allocate computing resources efficiently; the convergence and diversity metrics are defined to evaluate the search quality on assimilation and revolution; a novel imperialist competition is also given to enhance information exchanges among empires and strengthen the search for some worse solutions. Finally, extensive experiments are conducted, and the results demonstrate that DCICA outperforms the existing algorithms in solving the investigated problem.

Keywords:

permutation flow shop scheduling problem; makespan; total energy consumption; deterioration effect; imperialist competitive algorithm MSC:

90C29

1. Introduction

Computational intelligence (CI) has revolutionized the solution paradigms for complex combinatorial optimization problems, particularly in cyber-physical production systems where classical operations research methods reach their limits. The permutation flow shop scheduling problem (PFSP) is a prototypical NP-hard challenge [1,2]. At present, meta-heuristics have become a major method in solving PFSP [3,4]. Energy-efficient shop scheduling is an important part of green manufacturing, which is more difficult to solve than traditional scheduling problems and has greater academic research significance and engineering application value. Energy-efficient shop scheduling achieves efficiency, energy conservation, emission reduction, and consumption reduction through rational optimization of resource allocation, operation sorting, and operation modes [5,6].

In recent years, the Energy-Efficient PFSP (EPFSP) has been studied extensively. Due to the NP-hard nature of the problem, meta-heuristics have become the dominant solution approach, which can generally be categorized into local search-based and population-based algorithms. Regarding local search-based methods, Iterated Greedy (IG) algorithms are widely adopted due to their simple structure and strong exploitation ability. For example, a multi-objective IG was developed in [7] to solve EPFSP with sequence-dependent setup times (SDST). Similarly, Ding et al. [8] designed a modified multi-objective IG (MMOIG) for carbon-efficient scheduling. Variable Neighborhood Search (VNS) is another effective approach; for instance, Wu et al. [9] applied VNS to the no-wait EPFSP. In terms of population-based methods, evolutionary algorithms are frequently employed to maintain population diversity. Jiang et al. [10] designed an improved MOEA/D, which decomposes the multi-objective problem into scalar sub-problems. Other swarm intelligence algorithms, such as the Discrete Whale Swarm Optimization (IDWSO) [11] and Hybrid Multi-Objective Backtracking Search Algorithm (HMOBSA) [12], have proven effective in handling complex constraints.

With respect to relevant research on PFSP with a deterioration effect, in [13,14,15], a multi-objective discrete fireworks algorithm (MO-DFWA) was proposed, an artificial-molecule-based chemical reaction algorithm was presented, and an h-MOEA/D was introduced to solve PFSP with deterioration of jobs. In [16], a multi-verse optimizer was employed for the PFSP with the deterioration of jobs. A pseudo-polynomial time algorithm was utilized by Shabtay et al. [17] for proportionate PFSP with step-deteriorating processing times. In [18], a branch-and-bound algorithm was designed to address the problem that is also about deteriorating jobs. A discrete ABC was proposed to solve flexible FSP with assembly and deterioration effects of machines in [19]. In [20], a memetic algorithm was developed by Liu for a distributed hybrid FSP to minimize . A hybrid genetic algorithm was designed for the PFSP with a deterioration effect to minimize in [21].

The relevant works on EPFSP and deterioration are summarized in Table 1. As shown in the table, the vast majority of existing research focuses solely on the deterioration of jobs [13,14,15,16,17,18]. In these studies, the processing time of a job is defined as a function of its starting time (e.g., an ingot cooling down requires more time to roll as it waits longer). This perspective assumes that the machine’s capability remains constant.

Table 1.

Summary of the most relevant literature on EFJSP.

In contrast, this study addresses the deterioration effect of machines (EPFSP-DEM), a critical yet rarely investigated area. The distinction lies in the source of degradation: machine deterioration implies that the equipment’s processing efficiency declines due to cumulative wear, fatigue, or chemical corrosion during operation [19]. Consequently, the processing time of a job depends on the machine’s historical workload rather than the job’s starting time. This aspect has been largely neglected in the literature primarily due to the modeling complexity. Incorporating machine state-dependency introduces non-linear constraints that make the NP-hard scheduling problem significantly more difficult to solve. However, ignoring machine deterioration in energy-efficient scheduling can lead to substantial errors, as worn machines not only work more slowly but often consume more energy per unit of output.

The imperialist competitive algorithm (ICA) has some advantages, such as fast convergence speed, strong global search capability, and high accuracy, etc. At present, it has been applied to solve many multi-objective production scheduling problems [30] and has obtained better results. Therefore, ICA is a potential algorithm to handle EPFSP-DEM.

The primary objective of this research is to formalize and solve the EPFSP with machine deterioration (EPFSP-DEM), aiming to simultaneously minimize the makespan and total energy consumption. The contributions of this paper are described as follows. (1) EPFSP-DEM with the objectives of minimizing makespan and total energy consumption is investigated. (2) A differentiated assimilation is developed to improve the diversity of the population. (3) A knowledge-guided revolution is designed to reasonably allocate computing resources. (4) The convergence and diversity metrics are defined to evaluate the search quality of assimilation and revolution.

The remainder of the paper is organized below. EPFSP-DEM is described in Section 2, followed by the introduction to ICA in Section 3. An imperialist competitive algorithm considering diversity and convergence (DCICA) for EPFSP-DEM is reported in Section 4. Experiments are shown in Section 5, and conclusions are summarized in the final section.

2. Problem Description

EPFSP-DEM is described below. There are n jobs and m machines . Each job is processed in terms of the same production flow: . There is a set V with d different processing speeds for all machines, . When job is processed on at speed , the processing time is . The deterioration rate of is defined as . Not all machines turn off completely before the processing of all jobs is finished.

Some assumptions are listed below.

- (1)

- Job preemption is not allowed.

- (2)

- Each job can only be processed on one machine at a time.

- (3)

- All jobs and machines are available at time zero.

- (4)

- Each machine cannot process more than one job at a time.

- (5)

- Transportation and setup times are negligible, etc.

This study adopts the step-deterioration effect model, as shown in Equation (1).

where is the lower (upper) bound of the threshold; represents the actual processing time of on . To accurately describe the scheduling process, let denote the permutation of jobs to be processed. The completion time of the i-th job on machine is calculated recursively using Equation (2). This recursion embodies the two fundamental constraints of flow shop scheduling: (1) Operation Precedence Constraint, meaning a job cannot start on machine until it finishes on ; and (2) Machine Availability Constraint, meaning machine cannot process job until it finishes the previous job .

Based on the recursive calculation, the two objectives, Makespan () and Total Energy Consumption (), are formulated as follows:

where is a binary variable equal to 1 if job is processed on machine at speed , and 0 otherwise. Equation (3) defines the makespan as the completion time of the last job on the last machine. Equation (5) calculates the total processing energy consumption based on the selected speed. Equation (6) calculates the total idle energy consumption , where the total idle time is derived by subtracting the total processing time from the makespan. and represent the processing power and stand-by power in kW, respectively.

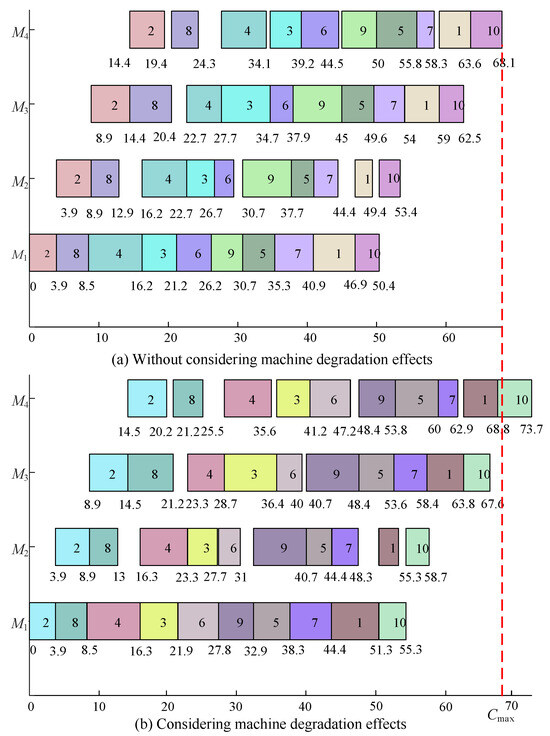

To verify the model and illustrate the impact of the deterioration effect, a numerical example of EPFSP-DEM is presented. This instance consists of ten jobs () and four machines (). Table 2 details the standard processing times () for each job on each machine under the base speed (), along with the specific deterioration rate () for each machine. For example, machine has a deterioration rate of , implying that its processing efficiency declines faster than () as the cumulative processing time increases. And Table 3 lists the energy consumption per unit time () corresponding to five distinct speed levels. It reflects the trade-off considered in this study: higher processing speeds () significantly reduce operation time but result in higher power intensity () compared to lower speeds ().

Table 2.

An example of EPFSP-DEM.

Table 3.

Energy consumption per unit time (kW).

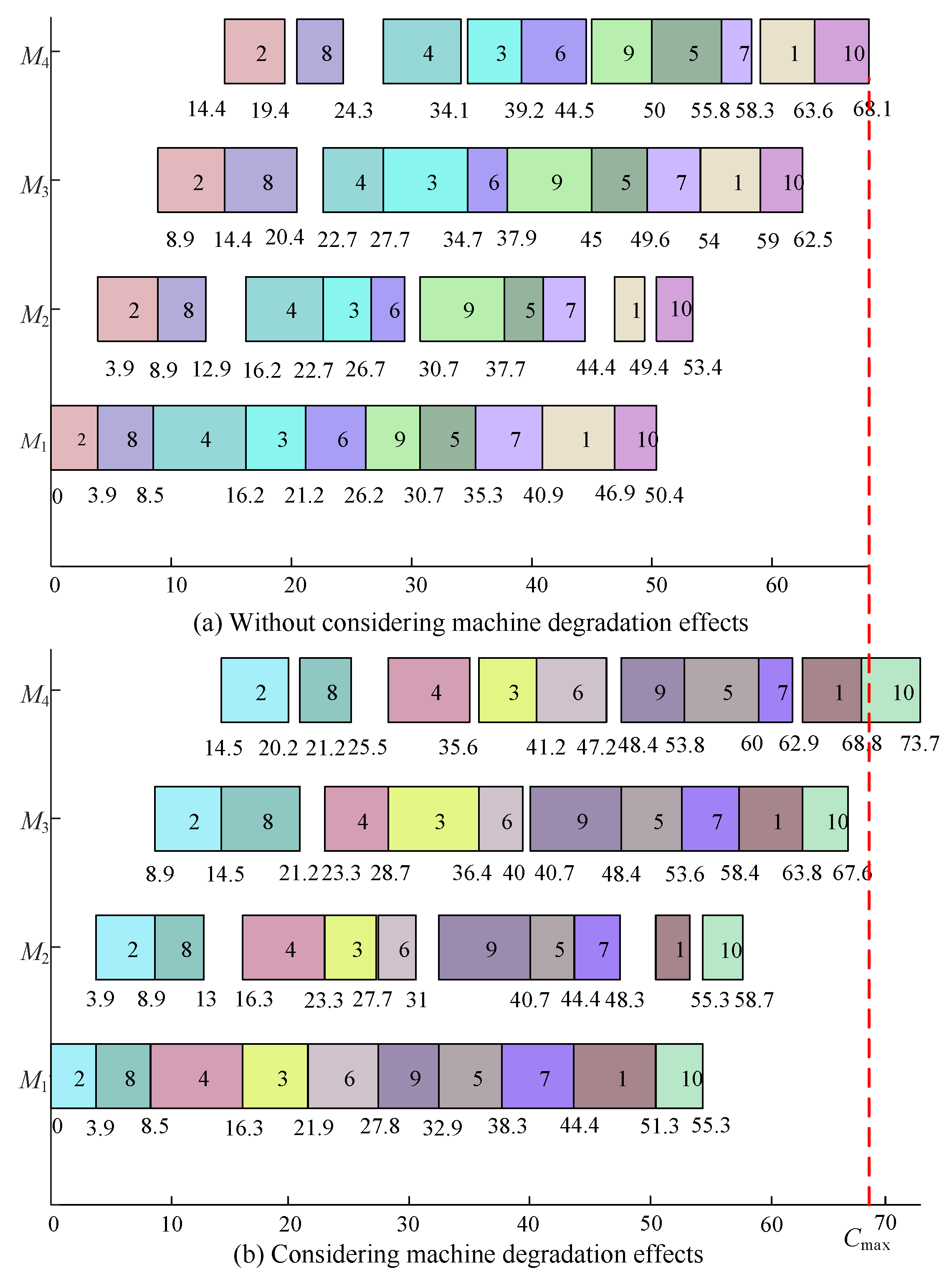

Figure 1 visualizes the scheduling results of this instance using Gantt charts to compare two scenarios: Figure 1a depicts the schedule without considering the deterioration effect (i.e., treating machines as ideal with constant efficiency). Figure 1b shows the schedule for the same job sequence and speed selection but with the deterioration effect derived from Equation (1). By comparing Figure 1b with Figure 1a, the influence of machine aging is evident. As machines operate continuously, the actual processing time for later jobs becomes longer than the standard processing time . For instance, consider the last few jobs on Machine 1 (). In Figure 1a, the operations are compact. However, in Figure 1b, due to the deterioration rate of , the processing times for the subsequent jobs are prolonged. Consequently, the entire schedule is stretched, pushing the completion time of the final job from 68.1 to 73.7. This comparison visually confirms that neglecting the deterioration effect in practical manufacturing can lead to significant underestimations of both completion time and energy costs.

Figure 1.

The Gantt charts of the instance.

3. Introduction to ICA

ICA was first proposed by Atashpaz-Gagari and Lucas [31], which consists of initial empires, assimilation, revolution, and imperialist competition. In ICA, one country represents a feasible solution, whose quality is determined by a cost value. Generally, the better the quality of a solution is, the smaller the cost value is. The procedures of ICA are shown in Algorithm 1, where and represent normalized cost values and the power of the imperialist , respectively. indicates the number of colonies possessed by the imperialist , is the number of imperialists, and denotes the total number of colonies.

| Algorithm 1 ICA |

|

where H denotes the set of all imperialists and is the cost value of the imperialist .

In assimilation, each colony in the empire q moves along the e direction toward the imperialist , where and e is the distance between the colony and the imperialist . To expand the search scope, a deviation is added on above movement, where is a parameter.

When there is a sudden change in the social and political characteristics of a colony, including culture, language, and religion, a revolution will be carried out in which colonies are first chosen by revolution probability, and then the related search operators are executed on the chosen colony. It is similar to the mutation operator of the genetic algorithm, which can improve the search ability of ICA and prevent premature convergence. After assimilation and revolution, the cost value of each colony is compared with that of the imperialist, one by one. If the cost value of the colony is better than that of the imperialist, they are exchanged.

In imperialist competition, stronger empires continually plunder the colonies of weaker ones to elevate their political standing, whereas weaker empires progressively decline or even perish. Imperialist competition is performed in the following way. Calculate total cost , the normalized total cost and the power for each empire q, construct a vector Q, decide an empire g with the greatest and allocate the weakest colony of the weakest empire into empire g.

where is a positive number, .

4. DCICA for EPFSP-DEM

In previous ICAs [30], there is only one learning object, which is the imperialist for all colonies. Under these circumstances, the diversity of the population will rapidly decrease. In revolution, the allocation of computing resources is rarely investigated. In addition, only one colony is transferred into the winning empire in imperialist competition. Information communication among empires should be strengthened to improve the search performance of the algorithm. In this paper, a DCICA is proposed to tackle EPFSP-DEM.

4.1. Encoding and Decoding

In EPFSP-DEM, two sub-problems must be solved: scheduling and speed selection. Therefore, this study adopts a two-string encoding method. and a speed selection string , where , indicates a speed utilized to process jobs.

The procedure of decoding is described as follows: determine the speeds for all machines according to the speed-assignment string; start from the first job in the scheduling string ; and process the jobs on machines as early as possible until all jobs are completed.

The procedure of decoding determines the speeds for all machines according to the speed assignment string and processes jobs on machines as early as possible. To avoid disrupting the flow of the text, a detailed numerical example illustrating the decoding procedure and specific objective calculations (based on the instance in Table 2) is provided in Appendix A.

4.2. Initialization and Initial Empires

To ensure the diversity of the population, the initial with N colonies is randomly produced. Initial empires are constructed after is obtained. For a colony , its normalized cost is calculated. Then, the colonies with the greatest values are selected as imperialists, and the remaining ones are assigned as colonies. Next, and are calculated for imperialist , and colonies are randomly allocated to imperialist . is determined as in Equation (14).

where indicates the rank value of by non-dominated sorting on [32], is the set of solutions with rank value of , and is defined by Lei et al [30]. is a function that gives the nearest integer of x.

After empires are constructed, each empire q is composed of the imperialist and colonies. For empire q, its normalized total cost is defined by Equation (15).

where is a set of colonies possessed by the imperialist and .

All empires are sorted in descending order of . Suppose that , empire 1() is the strongest (weakest) one.

4.3. Differentiated Assimilation

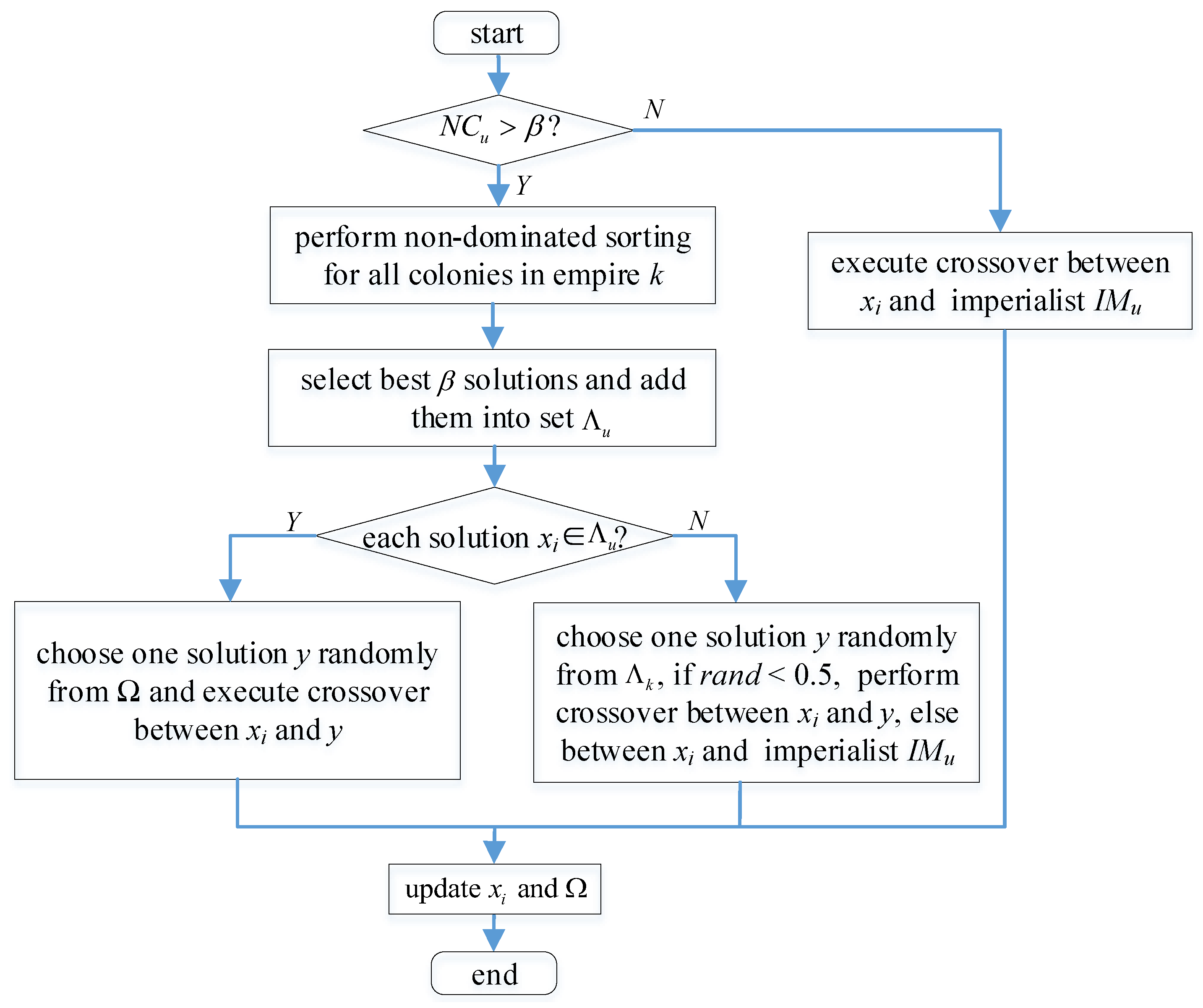

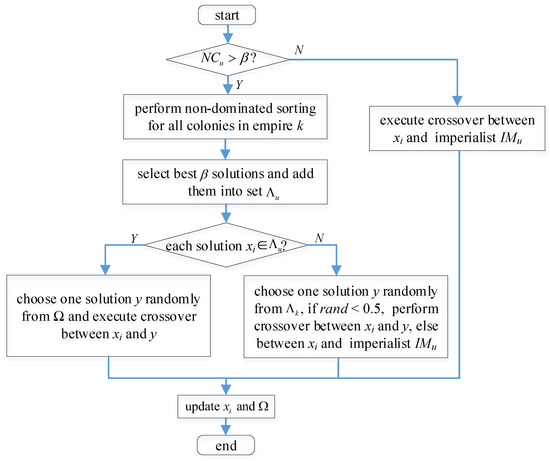

Generally, the crossover is utilized to perform assimilation between imperialists and colonies, and imperialists remain invariant [30]. When colonies only move toward their imperialist—that is, there is only one learning object—this leads to more similarities among them. The diversity of will decrease quickly. Therefore, many learning objects should be retained. On the other hand, it is necessary to distinguish some of the best solutions and others, since these best solutions are closer to the Pareto front and make it easier to produce better ones. Based on the above analyses, a differentiated assimilation is designed. Its specific procedure is described in Algorithm 2 and visually illustrated in Figure 2, where is an integer.

| Algorithm 2 Differentiated assimilation |

|

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the differentiated assimilation process.

Initial is empty. After assimilation finishes, all solutions in are deleted. Initial is composed of non-dominated solutions of the initial . When a new solution is added to , all dominated ones are deleted. Crossover is described below. Scheduling string and speed string of solutions and are executed sequentially. In this study, order-based crossover (OBX) and two-point crossover are adopted because of their effectiveness for solving scheduling problems, which are described as follows.

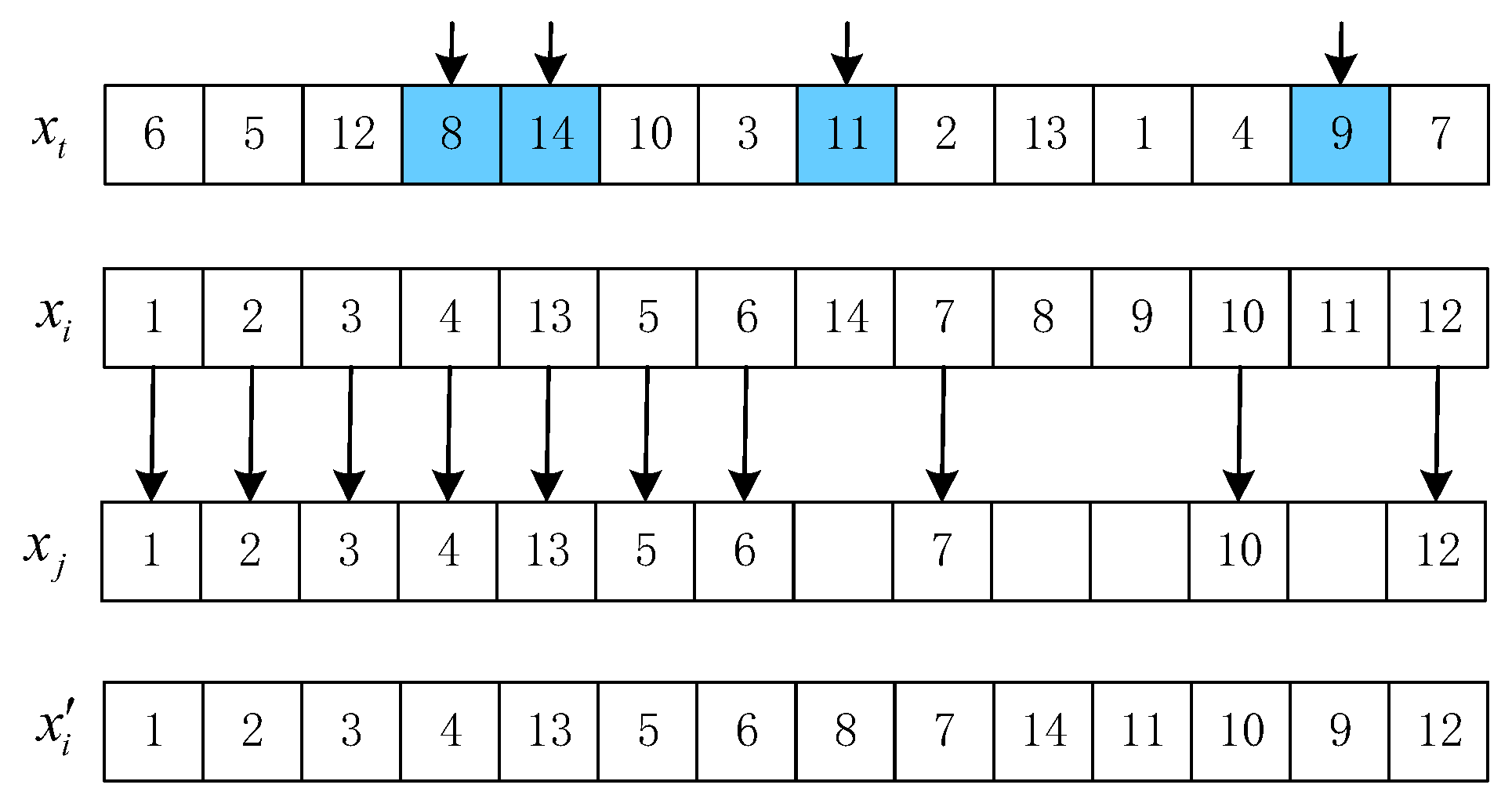

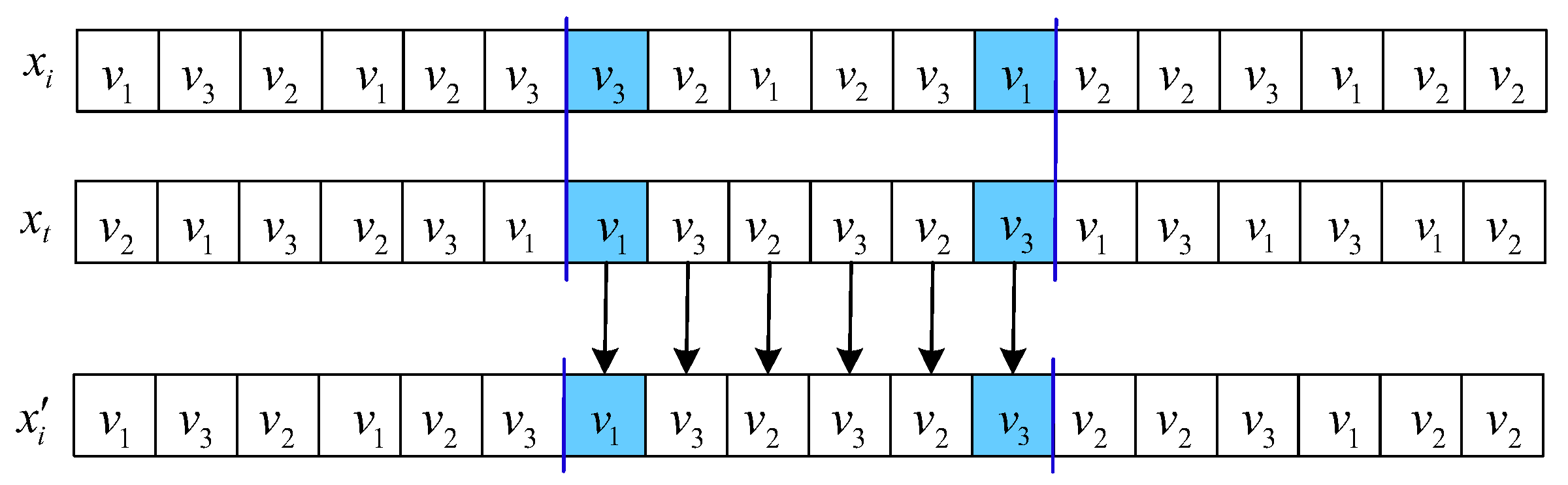

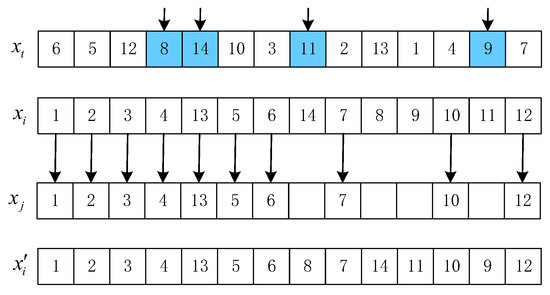

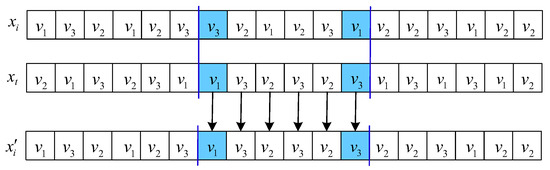

OBX acts on the scheduling string. For solutions and , randomly select G genes from , delete them from , and produce a partial solution . Finally, is generated by adding the chosen genes into as a sequence in , where G is set to by experiments. Figure 3 describes the process of OBX. Two-point crossover is applied to the speed string. For , stochastically select two positions l and h, . The speeds between l and h are replaced by the same positions of , as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

An example of OBX. The colors represent randomly selected jobs, and the arrows indicate that the positions of the jobs remain unchanged.

Figure 4.

An example of a two-point crossover. The colors represent randomly selected processing speeds, and the arrows illustrate the crossover operation performed at corresponding positions of and to generate .

4.4. Knowledge-Guided Revolution

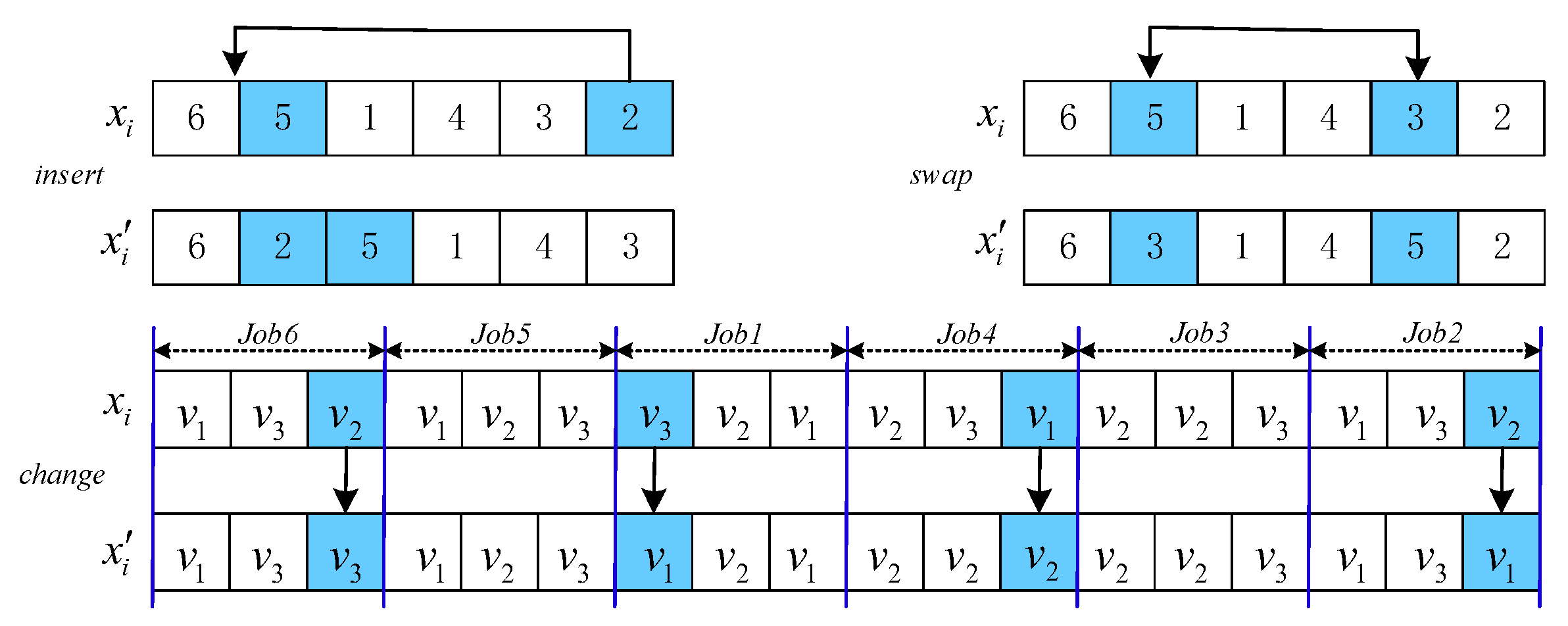

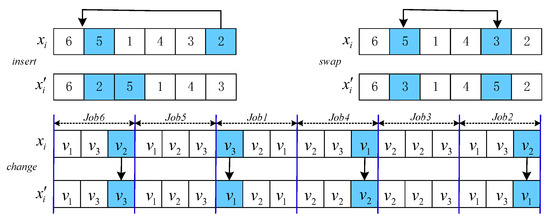

Revolution is another way to produce new solutions. In general, there is a probability that is employed to select colonies as revolutionaries. It is beneficial to exploit current information and enhance search efficiency. In this paper, three neighborhood structures—, , and —are adopted to perform revolution, which are represented as . Figure 5 shows the changes in them.

Figure 5.

Neighborhood structures . The colors represent randomly selected jobs or processing speeds. The arrows in the insert, swap, and change operators indicate job insertion, position swapping, and replacement operations, respectively.

To employ effectively, a knowledge-guided revolution is developed, where two kinds of knowledge are defined below.

Knowledge 1: The number of updating colonies by , denoted .

Knowledge 2: The number of updating by , denoted . The probability of selecting is calculated by

where is a weight coefficient.

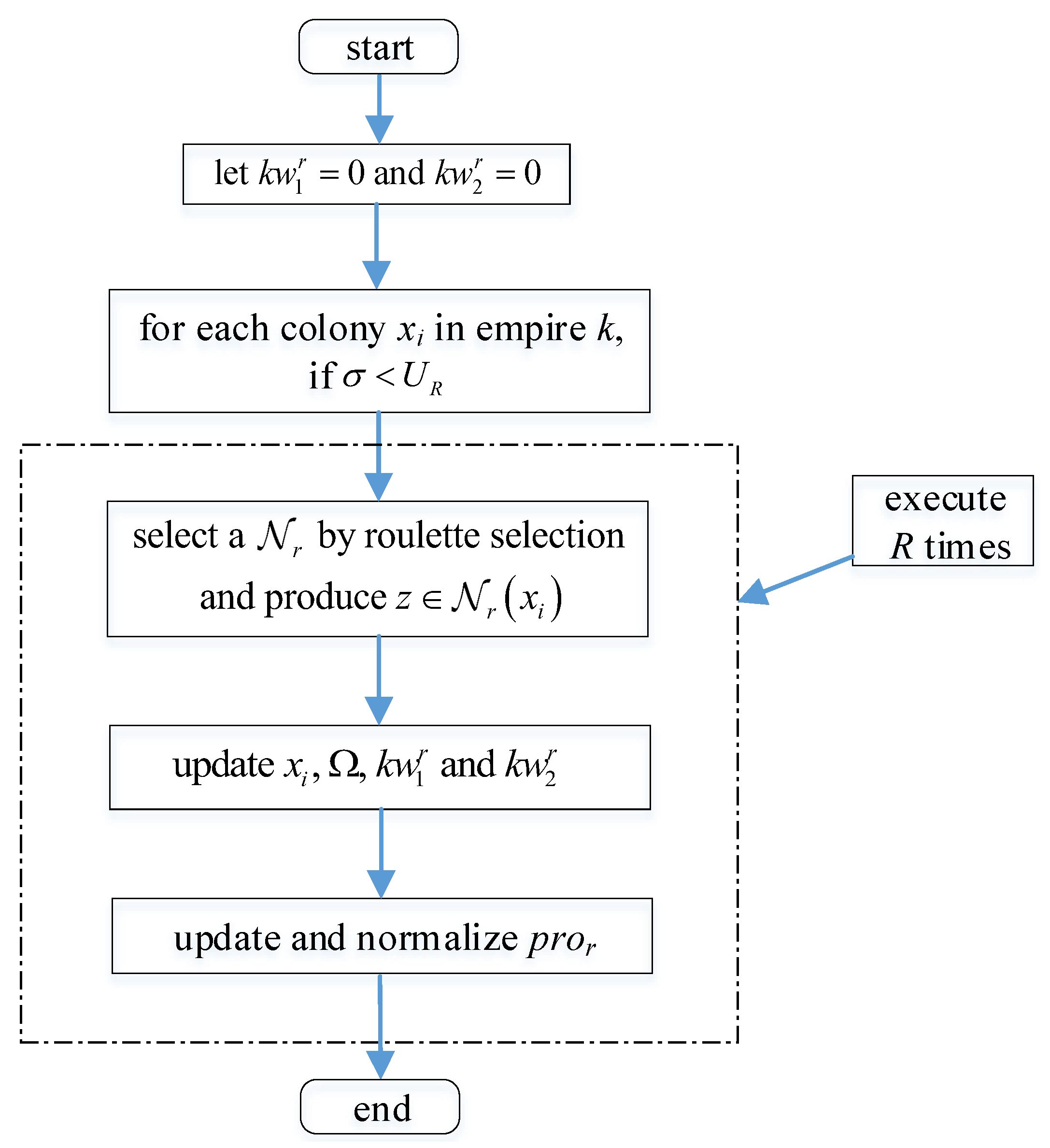

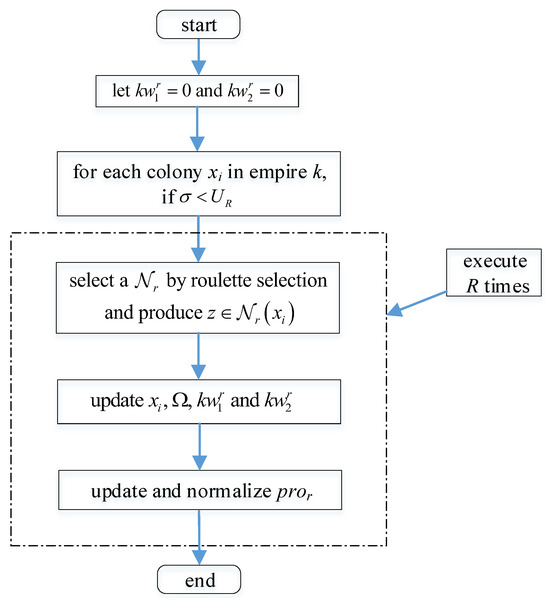

The proposed knowledge-guided revolution is thoroughly described in Algorithm 3, and its flowchart is presented in Figure 6.

| Algorithm 3 Knowledge-guided revolution |

|

Figure 6.

Flowchart of the knowledge-guided revolution strategy.

After assimilation and revolution are finished, each colony is compared with its imperialist in the empire q. If the colony is not dominated by its imperialist , the colony becomes the new imperialist, and the old one turns into the colony.

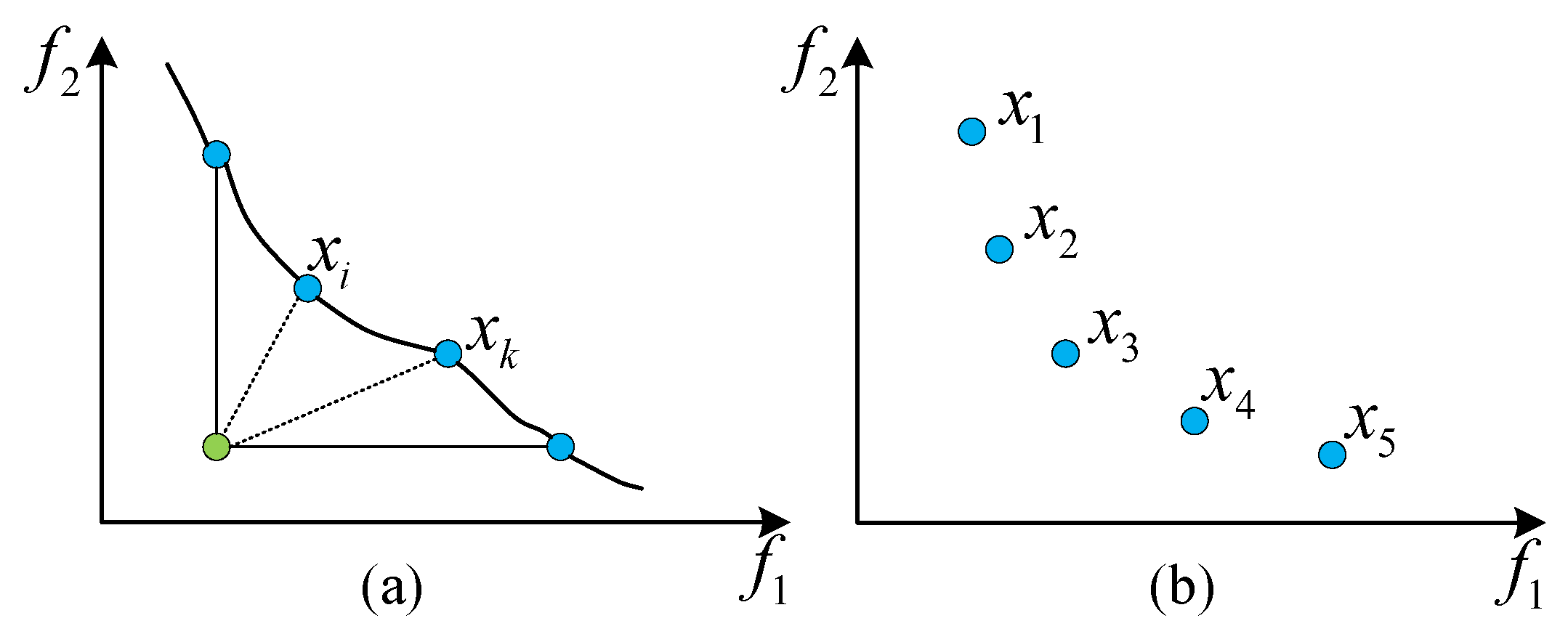

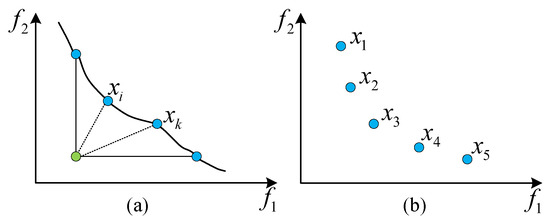

4.5. Definitions on Diversity and Convergence

The non-dominated solutions obtained by DCICA should be distributed uniformly in the search space and provide a better convergence performance. For solutions and in , the convergence is diverse although they are non-dominated with respect to each other, as shown in Figure 7a, where is less than . Here, . Obviously, is easier to reach the ideal point, marked by the green circle in Figure 7a, than in terms of the moving distance. Moreover, solutions in should maintain a uniform distribution, which means that they have better diversity, as shown in Figure 7b.

Figure 7.

The convergence and diversity of solutions. (a) Schematic of the convergence metric, where the green dot represents the ideal point, blue dots denote the non-dominated solutions, and the dashed and solid lines indicate the distances to the ideal point. (b) Schematic of the diversity metric, illustrating the distribution of solutions.

Based on the above analyses, this study designs two indicators, and , to evaluate the convergence and diversity of solutions at generation . The convergence of solutions in at generation is defined by

where is the j-th objective value of solution , and indicates the minimum (maximum) value of the j-th objective. After and are sorted in ascending order, the diversity of solutions in at generation is calculated by

According to the above evaluation, this study adopts four strategies to perform assimilation and revolution for improving search efficiency, where and represent convergence and diversity of solutions in at generation after performing assimilation and revolution.

- (1)

- and .

When this case occurs, it indicates that the search in assimilation does not change the quality of . More computing resources should be allocated to other areas.

- (2)

- and .

This case is similar to case 1. It means that revolution does not obtain promising results in the current search process; thus, a penalty is imposed, preventing the execution of the revolution.

- (3)

- and .

The non-dominated solutions in are selected to perform local search as in Section 4.4, since they are closer to Pareto-optimal solutions and easier to generate better solutions, which can guide the search further.

- (4)

- For other cases, DCICA performs a search as the original steps in the next iteration.

For the above case, it indicates that assimilation and revolution improve at least one of the diversity and convergence of the solutions in .

4.6. Imperialist Competition

In the original imperialist competition, when the power of an empire greatly exceeds that of other empires, there are enough opportunities to win and quickly occupy more colonies, which can lead to falling into local optima. In addition, competition only changes the structures of the winning empire and the weakest one. In fact, more colonies should be exchanged among empires, which is beneficial for changing the structures of empires and improving search efficiency. In this study, a novel imperialist competition is proposed and described in Algorithm 4, where W is set to 2.

| Algorithm 4 Novel imperialist competition |

|

Unlike the original ICA [30], when , the strongest empire does not participate in imperialist competition, which can prevent premature convergence of algorithms. Strengthening the search for the worst solutions in is beneficial for avoiding the wastage of computing resources. Meanwhile, it enhances information exchange among empires and improves the search efficiency of DCICA.

5. Computational Experiments

All experiments are coded by using MATLAB 2018b and run on an Intel Core i7-1260 16.0 G RAM 2.10 GHz win11 640S CPU PC.

5.1. Instances, Metrics, and Comparative Algorithms

To verify the performance of DCICA, 32 test instances are generated. The problem scales (defined by the number of jobs n and machines m) and the standard processing times () are constructed based on the structure of the classical Taillard benchmark set, which is also utilized in the literature [2]. Since the original benchmark does not consider energy consumption and machine deterioration, the specific parameters for EPFSP-DEM are extended as follows. Specifically, the instances cover combinations of and . The standard processing time () is generated from a uniform distribution . Regarding the energy parameters, the set of discrete speeds is , while the power consumption () is calculated by , where is randomly generated from , and the standby power is set to . Finally, to analyze the impact of machine aging, three levels of deterioration rates () are generated: Low (), Medium (), and High (). The and are determined by

The hypervolume () [33] and inverted generational distance () [33] are two widely used performance evaluation metrics to evaluate the performance of the DCICA.

Suppose that is a reference point in the objective space that is dominated by any Pareto optimal objective vector in a Pareto front approximation S. The value of S (with regard to ) measures the volume of the region in the objective space dominated by S and bounded by [33].

where indicates the Lebesgue measure. can measure the approximation in terms of both convergence and diversity. Obviously, the higher the value, the better the approximation is. In this paper, the value of S is calculated based on Equation (20) with reference point after normalizing S.

Let be a set of points uniformly sampled over the true Pareto front, and S be the set of solutions obtained by DCICA. The value of S is computed as:

where is the Euclidean distance between a point and its nearest neighbor , and is the cardinality of . calculates an average minimum distance from each point in to those in S, which measures both convergence and diversity of a solution set S. The lower the value is, the better the quality of S is.

In this study, six algorithms are selected for comparison to comprehensively evaluate the performance of DCICA. These algorithms were chosen based on three criteria: providing a baseline, relevance to energy-efficient scheduling, and handling of deterioration constraints. Specifically, the standard ICA is selected to verify whether the proposed strategies effectively improve upon the original algorithm. Regarding the state-of-the-art methods, MODBH [25], IDWSO [11], HMOBSA [12], and MMOIG [8] are chosen because they are representative metaheuristics specifically designed for EPFSP. They optimize the same objectives (Makespan and TEC) or can be directly adapted to the problem structure of this study. For instance, MMOIG reported superior performance in solving carbon-efficient flow shop problems. Furthermore, since this study considers the deterioration effect, MO-DFWA [13] is selected. Although it originally addressed job deterioration, it serves as a robust benchmark for evaluating algorithm performance under deterioration constraints. For fairness, all comparative algorithms were adapted to the EPFSP-DEM model by incorporating the machine deterioration constraints defined in Equation (1) while retaining their original search mechanisms.

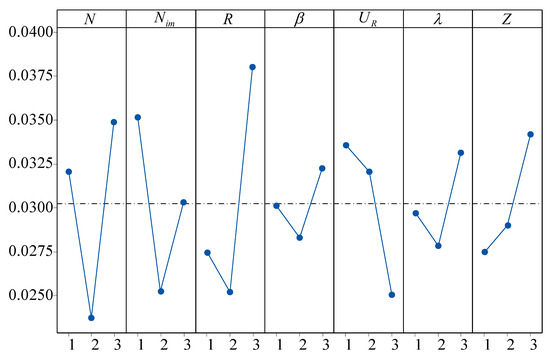

5.2. Parameter Settings

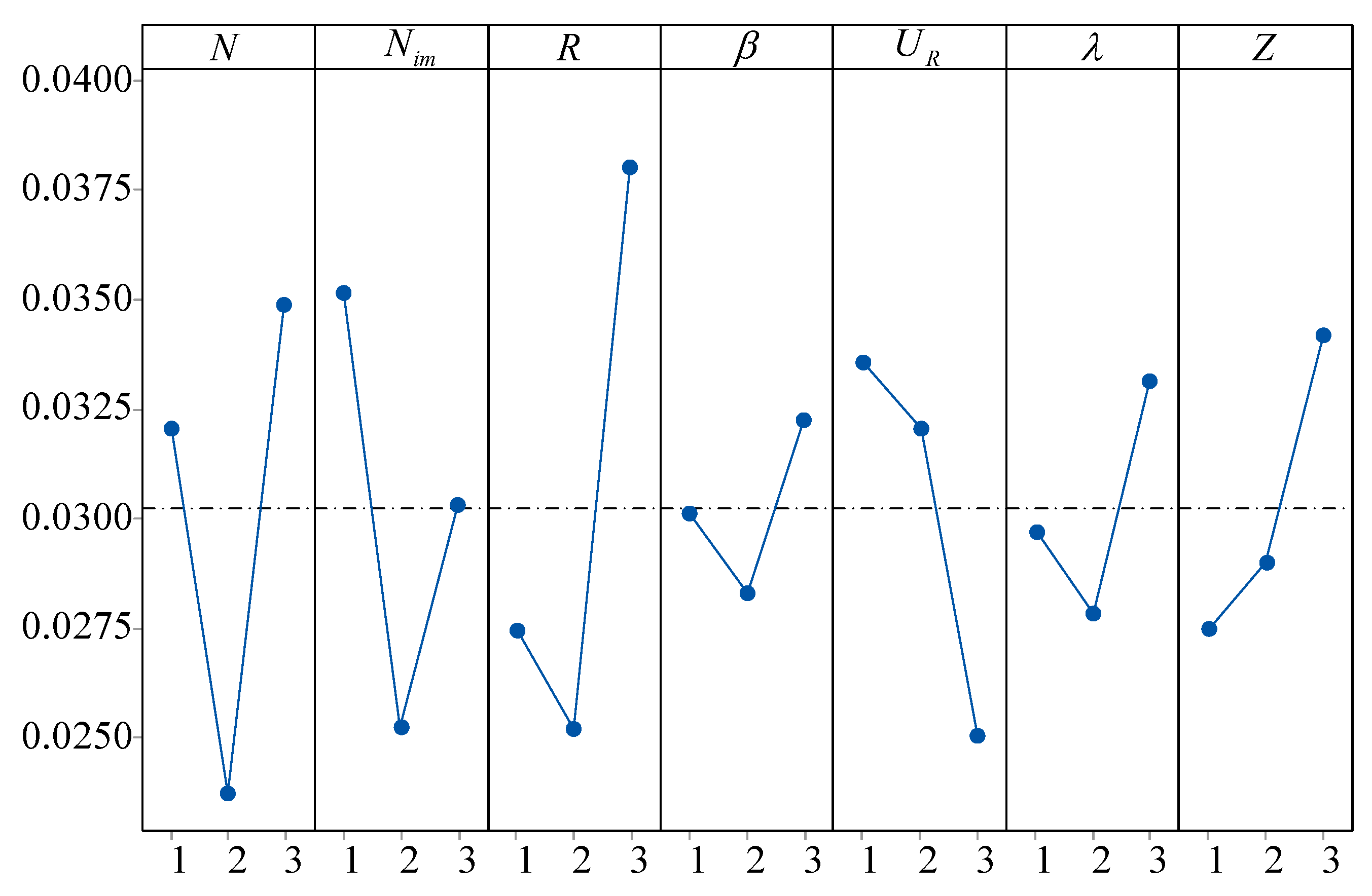

The key parameters of DCICA are listed below: N, , R, , , , Z. The Taguchi method is utilized to set parameters. The levels of parameters are shown in Table 4. Table 5 provides the orthogonal array , where represents the average value obtained by DCICA under three cases of , and each combination runs 10 times independently; for instance, .

Table 4.

Parameters of DCICA and their levels.

Table 5.

The orthogonal array .

The main effect plot of is presented in Figure 8. As presented in Figure 8, the parameter R has the greatest impact on the performance of DCICA because R determines the depth of local exploration of the algorithm. For population size N, under the premise of fixed total computation time, if N is too large, the total number of evolutionary generations of DCICA will decrease, resulting in insufficient evolution. Otherwise, it will weaken the evolutionary ability of the population at each generation. When a large is determined, DCICA will overly focus on local search, leading to premature convergence. For a small parameter , the diversity of DCICA will rapidly decrease. Conversely, it leads to insufficient global search capability. For , if the value of is relatively large, DCICA will fall into a blind search. A large parameter Z is detrimental to information exchange among empires, which will lead to premature convergence of DCICA.

Figure 8.

Main effects plot of all parameters on . The dashed line represents the total mean value of the IGD metric across all experiments.

Based on the above analysis, the best parameter settings of DCICA are , , , , , , and .

In addition, when seconds of research, DCICA, ICA, MODBH, IDWSO, HMOBSA, MMOIG, and MO-DFWA can converge fully; thus, the stopping condition is set to seconds. To ensure a fair comparison and optimal performance, the parameters for all comparative algorithms were also calibrated using the Taguchi method, identical to the procedure used for DCICA. Extensive preliminary experiments were conducted based on orthogonal arrays to identify the best configuration for each algorithm on the current test instances. Consequently, the resulting optimal parameter settings are listed below: MODBH: , . IDWSO: , , , . HMOBSA: , , , . MMOIG: , , . MO-DFWA: , , , , .

5.3. Results and Analyses

To reduce the impact of randomness, DCICA, ICA, MODBH, IDWSO, HMOBSA, MMOIG, and MO-DFWA run 10 times independently for all test instances. Since the true Pareto front of the investigated problem is unknown, this study adopts the non-dominated solutions of as of EPFSP-DEM, where , , , , , and are the set of non-dominated solutions obtained by DCICA, ICA, MODBH, IDWSO, HMOBSA, MMOIG, and MO-DFWA. Table 6, Table 7, Table 8, Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11 report the results obtained by all algorithms on metrics and under three cases of .

Table 6.

Performance comparison of all algorithms via metric under .

Table 7.

Performance comparison of all algorithms via -metric under .

Table 8.

Performance comparison of all algorithms via -metric under .

Table 9.

Performance comparison of all algorithms via -metric under .

Table 10.

Performance comparison of all algorithms via -metric under .

Table 11.

Performance comparison of all algorithms via -metric under .

As presented in Table 6, Table 7, Table 8, Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11, the values of the metrics and achieved by DCICA are better than those of ICA, MODBH, IDWSO, HMOBSA, MMOIG, and MO-DFWA on most test instances under the three cases of , distributed in , , , which is analyzed systematically as follows.

Under the first case , the metric of DCICA performs better than those of ICA, MODBH, IDWSO, HMOBSA, MMOIG, and MO-DFWA on 31, 29, 25, 27, 27, and 32 test instances. The metric of DCICA is superior to ICA, MODBH, IDWSO, HMOBSA, MMOIG, and MO-DFWA on 28, 24, 22, 27, 27, and 32 test instances. Therefore, DCICA is superior to ICA, MODBH, IDWSO, HMOBSA, MMOIG, and MO-DFWA on metrics and under .

Under the second case , the metric of DCICA is less than that of ICA, MODBH, IDWSO, HMOBSA, MMOIG, and MO-DFWA on 32, 30, 27, 31, 30, and 32 test instances. In other words, DCICA obtains better results than comparative algorithms over test instances. For metric , DCICA outperforms ICA, MODBH, IDWSO, HMOBSA, MMOIG, and MO-DFWA on 31, 21, 24, 29, 29, and 32 instances.

Under the third case , metric produced by DCICA is better than ICA, MODBH, IDWSO, HMOBSA, MMOIG, and MO-DFWA on 29, 27, 26, 29, 30, 32 test instances. For metrics , DCICA performs better than the compared algorithms on most instances. Moreover, the metric of DCICA performs better than those of ICA over test instances under , which also implies that the new strategies of DCICA are effective in solving EPFSP-DEM.

Table 12 shows the success rates of DCICA on metrics and under three cases of , namely , , and .

Table 12.

The success rates of DCICA on metrics and under three cases of .

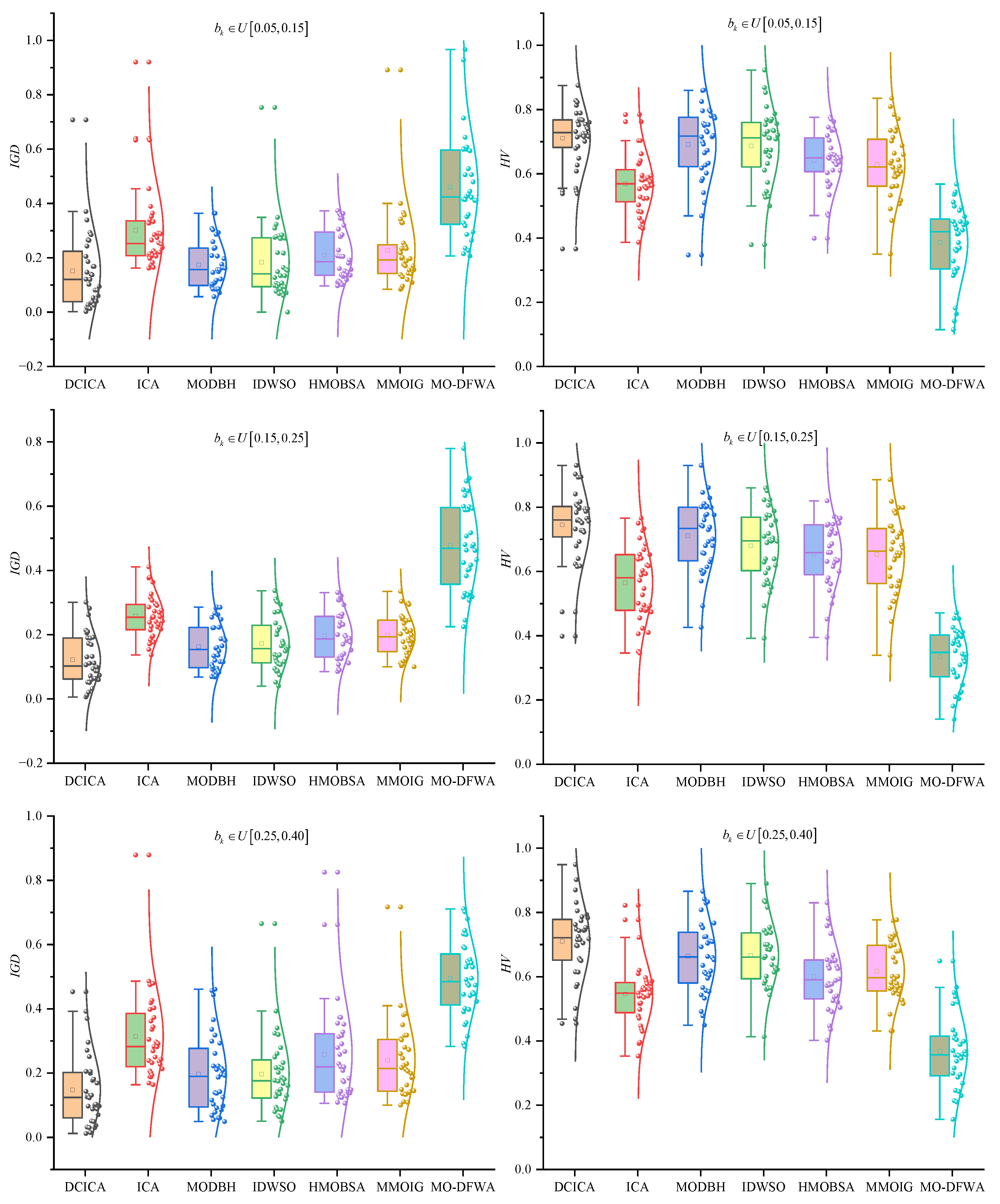

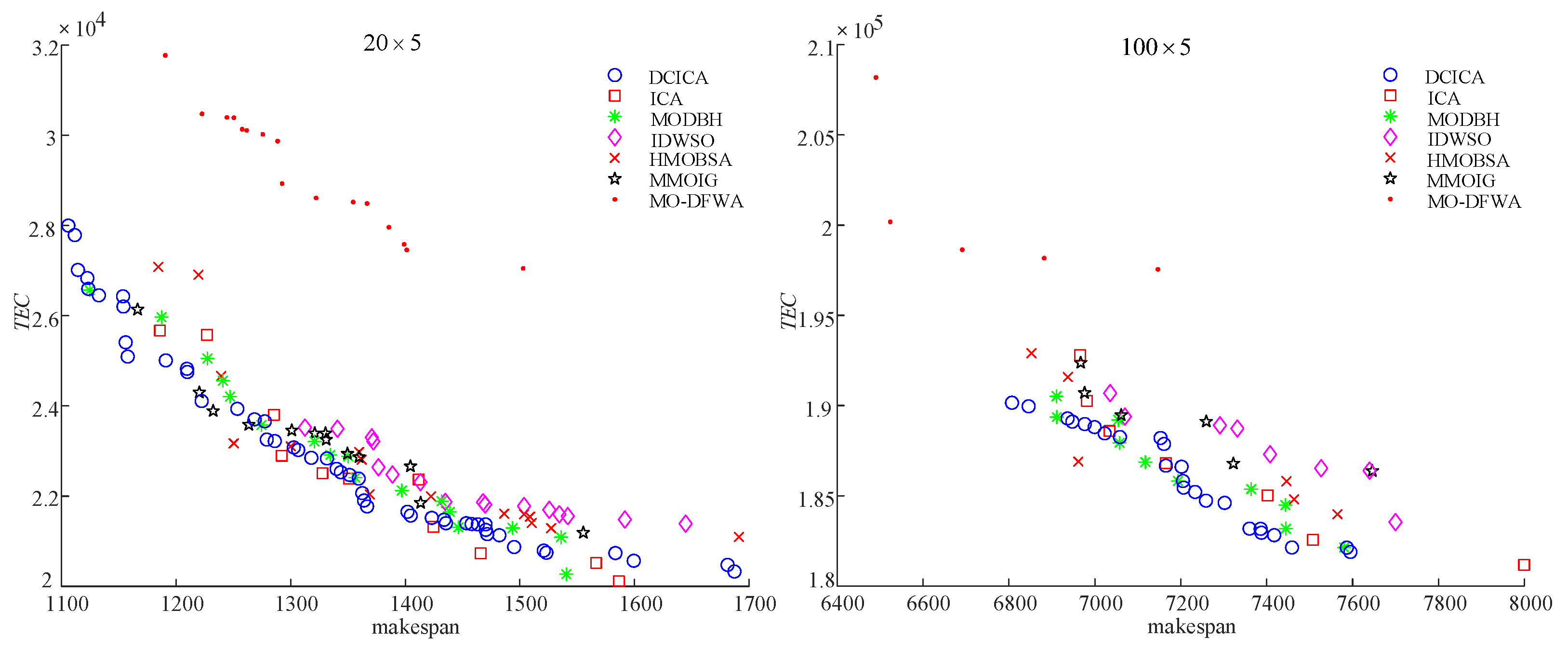

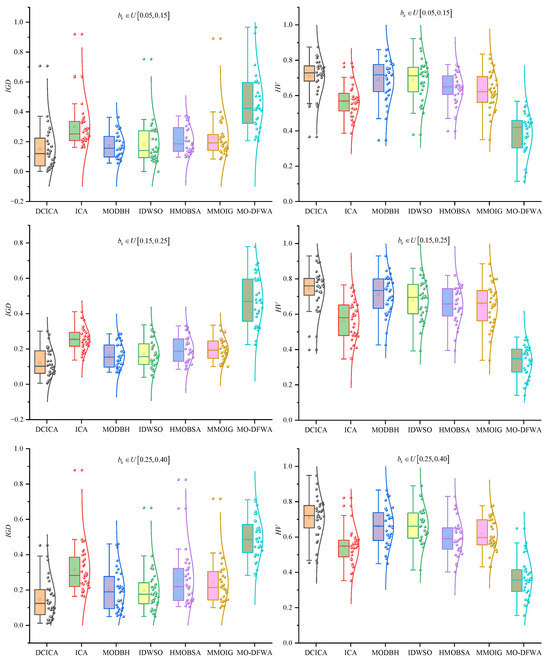

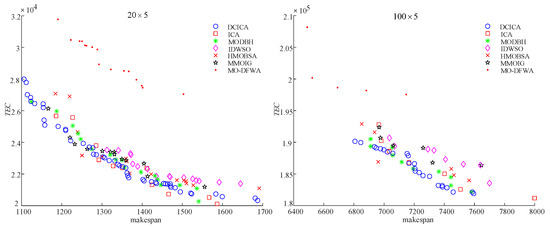

Figure 9 and Figure 10 are the box plots of metrics and non-dominated solutions produced by all algorithms. As shown in Figure 9, for the metric , the average values of DCICA are lower (higher) than those of ICA, MODBH, IDWSO, HMOBSA, MMOIG, and MO-DFWA. Hence, it indicates that DCICA is superior to ICA, MODBH, IDWSO, HMOBSA, MMOIG, and MO-DFWA. In Figure 10, it can be observed that the convergence of DCICA is better than that of other methods, and the solutions obtained by DCICA are also uniformly distributed in the search space. Therefore, the non-dominated solution distributions also illustrate that DCICA is superior to ICA, MODBH, IDWSO, HMOBSA, MMOIG, and MO-DFWA in solving EPFSP-DEM.

Figure 9.

Boxplot of all algorithms on metrics and .

Figure 10.

Non-dominated solutions for instances and under .

Statistics play a vital role in experiment result analyses, which can void influences from random factors. In this section, the Wilcoxon test, as a widely used test method, is adopted to determine the validity between DCICA and other compared algorithms. In principle, the Wilcoxon test utilizes the signed test of paired observation data to deduce the probability when the difference appears. represents that the results are outstanding compared with the other algorithms, and is the opposite. For each pair, the sum of and is equal to the total case numbers.

The statistical results through the Wilcoxon test at confidence interval are presented in Table 13, Table 14 and Table 15, where “Yes” represents that a significant difference exists between DCICA and the comparative algorithm. In this study, the confidence level is set to 0.05. If the p-value is less than through the Wilcoxon test, it indicates that there are significant differences between the pairwise algorithms. In Table 13, Table 14 and Table 15, it can be found that all p-values are less than on pairwise algorithms. That is, there are significant differences between DCICA and pairwise algorithms (ICA, MODBH, IDWSO, HMOBSA, MMOIG, and MO-DFWA) in solving EPFSP-DEM.

Table 13.

Results achieved by the Wilcoxon test under .

Table 14.

Results achieved by the Wilcoxon test under .

Table 15.

Results achieved by the Wilcoxon test under .

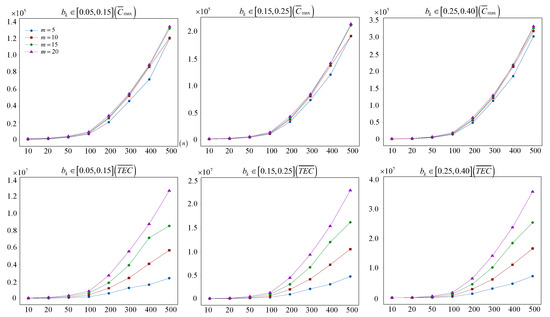

5.4. Analysis of the Deterioration Effect

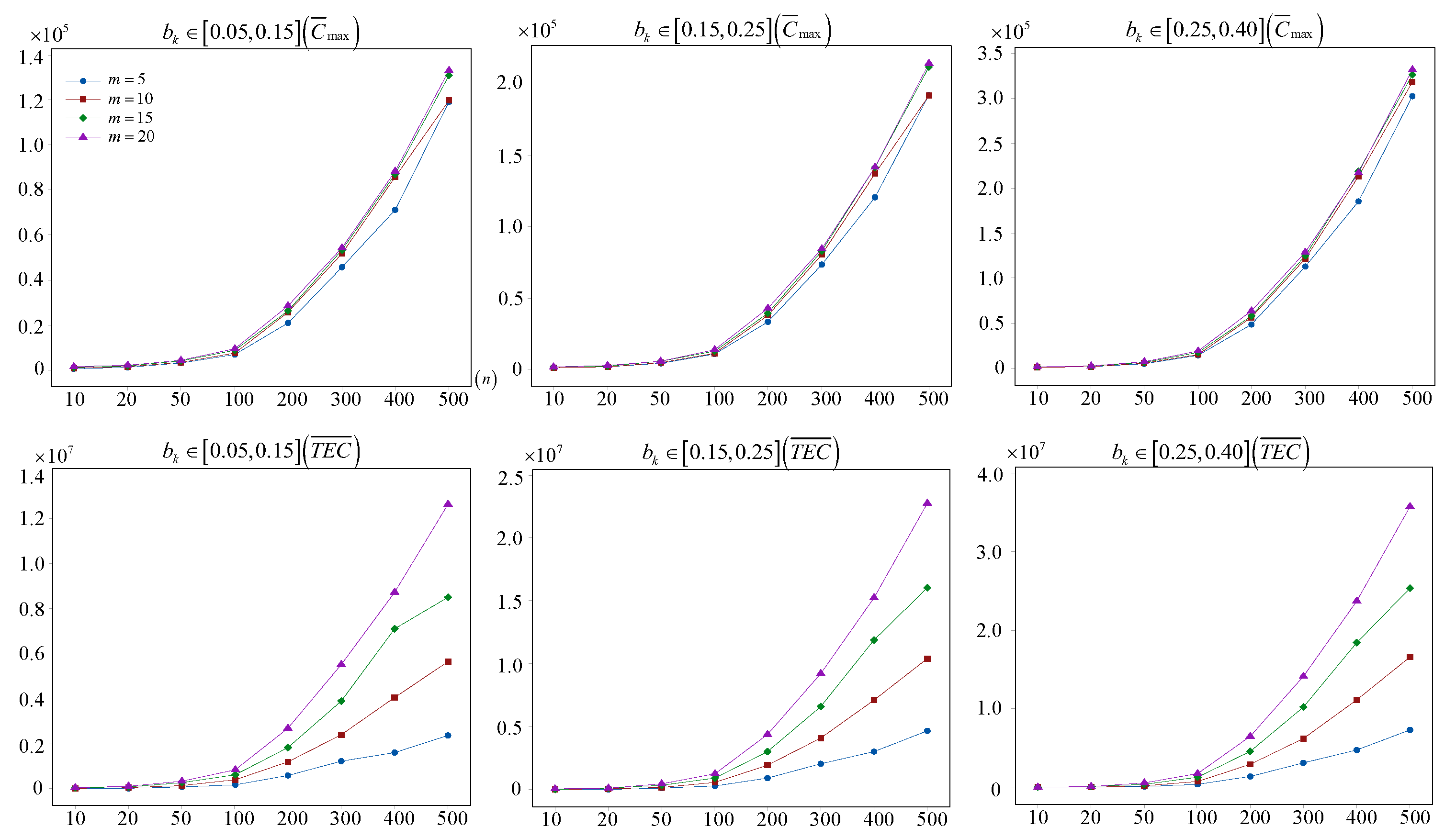

To observe the results more intuitively and analyze the influence of the deterioration effect for EPFSP-DEM, the results obtained by DCICA are listed in Table 16, Table 17 and Table 18 and presented in Figure 11, where and are the average value of and of non-dominated solutions produced by DCICA for each instance. Since EPFSP-DEM is a multi-objective optimization problem and many non-dominated solutions are commonly obtained, adopting and can better measure variations in and that are caused by the deterioration effect of machines.

Table 16.

The values of and obtained by DCICA under .

Table 17.

The values of and obtained by DCICA under .

Table 18.

The values of and obtained by DCICA under .

Figure 11.

The influence on and .

As shown in Figure 11, the horizontal comparisons indicate that as the number of jobs increases, the influence of the deterioration effect for variations of and generally shows an increasingly serious trend. Especially, the deterioration effect brings notable influences for large-scale test instances under the same number of machines. However, as the number of machines increases, the influence of the deterioration effect on is slightly less than that on under the same deterioration rate, as presented in Figure 11.

The search performances of DCICA mainly contribute to the following four aspects: (1) the proposed differentiated assimilation can improve the diversity of the population since many learning objects are kept, which can enlarge the search area and continuously update their status; (2) the knowledge-guided revolution is beneficial to efficiently allocate computing resources, and the blindness of randomly selecting neighborhood structures is avoided; (3) the newly defined convergence and diversity can effectively evaluate the search quality of differentiated assimilation and knowledge-guided revolution, which can guide the search of DCICA further and balance exploration and exploitation; (4) the novel imperialist competition can prevent premature convergence of algorithms, enhance information exchange among empires, and strengthen the search for worse solutions.

6. Conclusions

This paper investigated the Energy-Efficient Permutation Flow Shop Scheduling Problem with Machine Deterioration Effects (EPFSP-DEM) through the lens of computational intelligence theory, providing novel insights into the interplay between scheduling dynamics, energy consumption, and system degradation. Since the investigated problem is NP-hard, this study proposes a DCICA to optimize and simultaneously. Extensive experiments were conducted, and the results demonstrated that DCICA outperforms the existing algorithms in solving EPFSP-DEM. In addition, it was also observed that as the number of jobs increases, the impact of the deterioration effect on both makespan and total energy consumption generally exhibits an increasingly serious trend. Especially, the deterioration effect brings notable influences for large-scale test instances under the same number of machines. However, as the number of machines increases, the influence of the deterioration effect on makespan is slightly less than the total energy consumption under the same deterioration rate. However, potential limitations exist. The introduced mechanisms increase computational complexity compared to standard ICA, and the algorithm remains sensitive to parameter settings (e.g., ), necessitating careful calibration. In the future, this study will investigate Energy-Efficient Permutation Flow Shop Scheduling Problems with other constraints, such as machine preventive maintenance and transportation. Uncertainty dynamic factors, such as job delay and machine breakdowns, are also to be considered in our future work. Moreover, this study will explore other optimization algorithms, such as the particle swarm algorithm and the ant colony algorithm, to solve EPFSP-DEM.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.Y. and Y.C.; Methodology, K.Y., Z.L., M.L. and Y.C.; Software, K.Y.; Formal analysis, K.Y.; Resources, Y.X.; Writing—original draft, M.L.; Writing—review and editing, Z.L., Y.X. and Y.C.; Funding acquisition, M.L. and Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Project of the Science and Technology Department of Henan Province under Grant 252102221011, and the Research Project of Higher Education in Henan Province under Grant 23A413008.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Nomenclature

Notations and their descriptions:

| Symbol | Description |

| Indices and Sets | |

| n | Total number of jobs |

| m | Total number of machines |

| J | Set of jobs, |

| M | Set of machines, |

| V | Set of processing speed levels, |

| i | Index of jobs, |

| k | Index of machines, |

| l | Index of speed levels, |

| Parameters | |

| Standard processing time of job on machine at base speed | |

| Actual processing time of job on machine considering deterioration | |

| Deterioration rate of machine | |

| Lower and upper bound thresholds for the deterioration effect | |

| Power consumption per unit time of at speed (kW) | |

| Stand-by power consumption per unit time of (kW) | |

| Variables and Objectives | |

| Permutation of jobs, | |

| Completion time of job on machine | |

| Makespan (min) | |

| Total Energy Consumption (kJ) | |

| Total processing energy consumption (kJ) | |

| Total idle energy consumption (kJ) |

Appendix A. Numerical Example of Decoding

To illustrate the decoding process, we use the instance data from Table 2. A possible solution consists of a scheduling string and a speed string corresponding to the operations. Suppose that , , , , and for all machines. The calculation details are as follows:

For machine :

Similarly, for :

For :

For :

Based on the objective functions, the final results are calculated as and . This result corresponds to Figure 1b, demonstrating that considering the deterioration effect leads to increased makespan and energy consumption compared to the ideal case ().

References

- Wang, X.Y.; Ren, T.; Bai, D.Y.; Chu, F.; Yu, Y.D.; Meng, F.C.; Wu, C.C. Scheduling a multi-agent flow shop with two scenarios and release dates. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 421–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.X.; Wang, L.; Dong, C.X.; Chen, J.F. A knowledge-guided end-to-end optimization framework based on reinforcement learning for flow shop scheduling. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 20, 1853–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doush, I.A.; Al-Betar, M.A.; Awadallah, M.A.; Alyasser, Z.A.A.; Makhadmeh, S.N.; El-Abd, M. Island neighboring heuristics harmony search algorithm for flow shop scheduling with blocking. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2022, 74, 101127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, M.D.F.; Ribeiro, M.H.D.M.; Silva, R.G.D.; Mariani, V.C.; Coelho, L.D.S. Discrete differential evolution metaheuristics for permutation flow shop scheduling problems. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 166, 107956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Mishra, R.S.; Madan, A.K. Metaheuristic Solutions for Energy-Efficient Scheduling in Green Manufacturing. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayah, A.; Aqil, S.; Lahby, M. Green algorithms for energy-efficient distributed flow-shop manufacturing problem. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 236, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, X.; Jiang, Q.Q.; Li, C.; Li, S.H.; Chen, K. Permutation flow shop energy-efficient scheduling with a position-based learning effect. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 61, 382–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.Y.; Song, S.J.; Wu, C. Carbon-efficient scheduling of flow shops by multi-objective optimization. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016, 248, 758–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.Q.; Che, A.D. Energy-efficient no-wait permutation flow shop scheduling by adaptive multi-objective variable neighborhood search. Omega 2020, 94, 102117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, E.D.; Wang, L. An improved multi-objective evolutionary algorithm based on decomposition for energy efficient permutation flow shop scheduling problem with sequence-dependent setup time. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 1756–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, X.; Jiang, Q.Q.; Li, S.H.; Gong, S.Y.; Chen, K. Energy-efficient scheduling for a permutation flow shop with variable transportation time using an improved discrete whale swarm optimization. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 126121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Gao, L.; Li, X.Y.; Pan, Q.K.; Wang, Q. Energy-efficient permutation flow shop scheduling problem using a hybrid multi-objective backtracking search algorithm. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 144, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.P.; Ding, J.L.; Wang, H.F.; Wang, J.W. Two-objective stochastic flow-shop scheduling with deteriorating and learning effect in Industry 4.0-based manufacturing system. Appl. Soft Comput. 2018, 68, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.P.; Zhou, M.C.; Guo, X.W.; Qi, L. Artificial-molecule-based chemical reaction optimization for flow shop scheduling problem with deteriorating and learning effects. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 53429–53440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.P.; Wang, H.F.; Tian, G.D.; Li, Z.W.; Hu, H.S. Two-agent stochastic flow shop deteriorating scheduling via a hybrid multi-objective evolutionary algorithm. J. Intell. Manuf. 2019, 30, 2257–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.F.; Huang, M.; Wang, J.W. An effective metaheuristic algorithm for flowshop scheduling with deteriorating jobs. J. Intell. Manuf. 2019, 30, 2733–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabtay, D.; Mor, B. Exact algorithms and approximation schemes for proportionate flow shop scheduling with step-deteriorating processing times. J. Sched. 2024, 27, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Sun, L.Y.; Sun, L.H.; Wang, J.B. On three-machine flow shop scheduling with deteriorating jobs. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2010, 125, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Cahng, C.T.; Liu, Z. A discrete artificial bee colony algorithm and its application in flexible flow shop scheduling with assembly and machine deterioration effect. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 159, 111593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhao, F.Q.; Wang, L.; Xu, T.P.; Dong, C.X. Evolutionary multitasking memetic algorithm for distributed hybrid flow-shop scheduling problem with deterioration effect. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 1390–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, D.Y.; Wang, J.B. Considering the peak power consumption problem with learning and deterioration effect in flow shop scheduling. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 197, 110599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanzadeh, M.; Ranjbar, M. Energy-aware production scheduling in the flow shop environment under sequence-dependent setup times, group scheduling and renewable energy constraints. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 307, 519–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekkal, D.N.; Belkaid, F. A multi-objective optimization algorithm for flow shop group scheduling problem with sequence dependent setup time and worker learning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 233, 120878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, J.; Rieck, J. Mid-term energy cost-oriented flow shop scheduling: Integration of electricity price forecasts, modeling, and solution procedures. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 163, 107810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber, R.G.; Ranjbar, M. Minimizing the total tardiness and the total carbon emissions in the permutation flow shop scheduling problem. Comput. Oper. Res. 2022, 138, 105604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marichelvam, M.K.; Geetha, M. A memetic algorithm to solve uncertain energy-efficient flow shop scheduling problems. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 115, 515–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Wang, X.L. A multi-objective discrete differential evolution algorithm for energy-efficient two-stage flow shop scheduling under time-of-use electricity tariffs. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 133, 109946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M.H.; Hnaien, F.; Dugardin, F. Exact method to optimize the total electricity cost in two-machine permutation flow shop scheduling problem under time-of-use tariff. Comput. Oper. Res. 2022, 144, 105788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Zhou, S.C.; Xu, R.; Chen, H.P. Energy-efficient scheduling for multi-objective two-stage flow shop using a hybrid ant colony optimization algorithm. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 4103–4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, D.M.; Li, M.; Wang, L. A two-phase meta-heuristic for multiobjective flexible job shop scheduling problem with total energy consumption threshold. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2019, 49, 1097–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atashpaz-Gargari, E.; Lucas, C. Imperialist competitive algorithm: An algorithm for optimization inspired by imperialistic competition. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation, Singapore, 25–28 September 2007; pp. 4661–4667. [Google Scholar]

- Deb, K.; Pratap, A.; Agarwal, S.; Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2002, 6, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Li, J.Q.; Xu, Y.; Duan, P.Y. Multi-population cooperative multi-objective evolutionary algorithm for sequence-dependent group flow shop with consistent sublots. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 237, 121594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).