Abstract

Memristor is widely used to construct various memristive neural networks with complex dynamical behaviors. However, hidden multiple attractors have never been realized in memristive neural networks. This paper proposes a novel chaotic system based on a memristive Hopfield neural network (HNN) capable of generating hidden multiple attractors. A multi-segment memristor model with multistability is designed and serves as the core component in constructing the memristive Hopfield neural network. Dynamical analysis reveals that the proposed network exhibits various complex behaviors, including hidden multiple attractors and a super multi-stable phenomenon characterized by the coexistence of infinitely many double-chaotic attractors—these dynamical features are reported for the first time in the literature. This encryption process consists of three key steps. Firstly, the original chaotic sequence undergoes transformation to generate a pseudo-random keystream immediately. Subsequently, based on this keystream, a global permutation operation is performed on the image pixels. Then, their positions are disrupted through a permutation process. Finally, bit-level diffusion is applied using an Exclusive OR(XOR) operation. Relevant research shows that these phenomena indicate a high sensitivity to key changes and a high entropy level in the information system. The strong resistance to various attacks further proves the effectiveness of this design.

Keywords:

memristor; memristive neural network; chaos; multi-scroll attractor; hidden attractor; chaotic image encryption MSC:

94-10

1. Introduction

Discovered in the 1960s [1], the Lorenz system initiated the study of chaos theory across disciplines including nonlinear circuits, nonlinear dynamics, information security, and neuroscience [2,3,4]. Furthermore, through dynamical analyses—such as bifurcation mechanisms and the 0–1 test—applied to both continuous and discrete chaotic systems, researchers have contributed significant insights to the advancement of chaos theory [5]. A core concept in chaotic dynamics is the chaotic attractor [6,7]. Among these, multi-scroll attractors (MSAs) represent a complex type composed of numerous interconnected scroll structures [8,9]. In contrast to conventional one-, two-, or four-scroll attractors, MSAs demonstrate richer dynamic behavior, increased sensitivity, and more sophisticated structural features.

As early as 1997, Suykens and Chua first reported the emergence of multiple double attractors in cellular neural networks [10]. However, the trajectories and quantities of these attractors remained ambiguous and difficult to control. In contrast, the Hopfield neural network (HNN), a system renowned for its rich nonlinear dynamical properties [11,12], has garnered considerable attention in recent years. A variety of chaotic attractors, including hyperchaotic [13,14] and coexisting attractors [15,16], have been successively identified in different HNN configurations. Notably, in 2020, Lin et al. successfully generated four- and six-scroll chaotic attractors using a three-neuron HNN [17]. Shortly thereafter, Zhang et al. enhanced the network by incorporating memristive synapses, enabling the generation of even-numbered multi-scroll attractors [18]. Further advancing this trajectory, Lai et al. proposed in 2022 a tunable conductance memristive HNN model that achieved multiple dual-scroll attractors [19,20]. Similar multi-scroll behaviors have also been documented across various other memristive neural networks [21,22,23]. Despite these advances, the occurrence of hidden multiple attractors, a class of dynamical behavior more complex than self-excited attractors, has yet to be observed in HNNs. This gap motivates further exploration into more sophisticated brain-like dynamics. The brain, as an immensely complex dynamical system, exhibits higher behavioral complexity that correlates strongly with the randomness of chaotic signals it may produce. Harnessing such brain-like dynamics could substantially enhance information encryption systems by improving security and unpredictability. Therefore, the investigation and discovery of novel brain-like dynamic phenomena in neural networks not only holds theoretical significance but also paves the way for innovative practical applications.

Based on the aforementioned research background, this chapter introduces a novel chaotic system derived from a memristive Hopfield neural network (HNN), capable of generating hidden multiple attractors. First, a multi-segment memristor model with multistability is designed, which serves as the core component for constructing the memristive HNN. Dynamical analyses demonstrate that the proposed network exhibits a range of complex behaviors, including hidden multiple attractors and a super multi-stable phenomenon characterized by the coexistence of infinitely many double-chaotic attractors. These dynamical features are reported for the first time in the existing literature. Leveraging the rich chaotic properties of the hidden attractors in this memristive HNN, we further develop an encryption scheme for color images. Experimental evaluations confirm that the proposed system not only demonstrates outstanding performance in terms of key sensitivity, information entropy, NPCR and UACI but also possesses strong resistance against various attacks, indicating a high level of security. This work establishes a fundamental divergence from conventional image encryption paradigms by innovating at the chaotic source itself. Our approach was to build a completely new chaotic system from scratch, which is different from previous studies that merely made superficial improvements to existing encryption methods. Precursors absent, this manuscript elucidates revelations of concealed attractors alongside instances of super multistability phenomena residing within the memristive HNN architecture. Unprecedented too is its deployment for encrypting imagery therein.

2. Design of Multi-Stable Memristors

2.1. Memristor Model Description

Based on the memristor theory, a new voltage-controlled multi-stable memristor model is proposed, and its mathematical expression is as follows:

Among them, v and i represent the voltage across the memristor and the current through the memristor, respectively. The variable z denotes the internal state of the memristor, conceptually linked to the magnetic flux, which governs the memductance W(z).

The function f(z) is explicitly defined as a piecewise function (Equations (3) and (4)), comprising f1(z) and f2(z). This formulation exists not from foundational derivation but is an architectonic imposition intended for crafting a potential topography abundant with wells within the state domain. Within f1(z), noticeable are hyperbolic tangent expressions such as tanh(p(z + (2i − 1))) or tanh(p(z − (2i − 1))), which initiate conjoint unstable stasis proximate to z = (2i − 1) or −(2i − 1). From this aggregation of terms arises the deliberate schematic of multiple equilibria.

Integral to this design, the parameter p acts; its magnitude fixed large (specifically at p = 100), compelling each individual tanh articulation to approximate closely a signum configuration, hence manifesting equilibrium loci that are distinctly articulated and widely dispersed. Observed herein is the requirement that such separation facilitates the emergence of distinct scrolls inherent in chaotic attractant phenomena.

Contemplate for instances wherein f2(z) presents with variable M settled at unity. Herein, additional elements −[tanh(p(z + 2)) + tanh(p(z − 2))] supplement appendageal to the primary expression −tanh(pz). Hence dual-augmented pairs of tenuous equilibria surrounding z valued at 2 or −2 emerge, thus generating conditions suitable for a four-scroll attractor’s origin. Seen from this, integer variables N and M permit direct regulation over both complexity levels and numerosity intrinsic to ensuing multifarious-scroll assemblies (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Parameters of the multi-stable memristor model.

2.2. Memristor Characteristic Analysis

- (1)

- The tight hysteresis loop

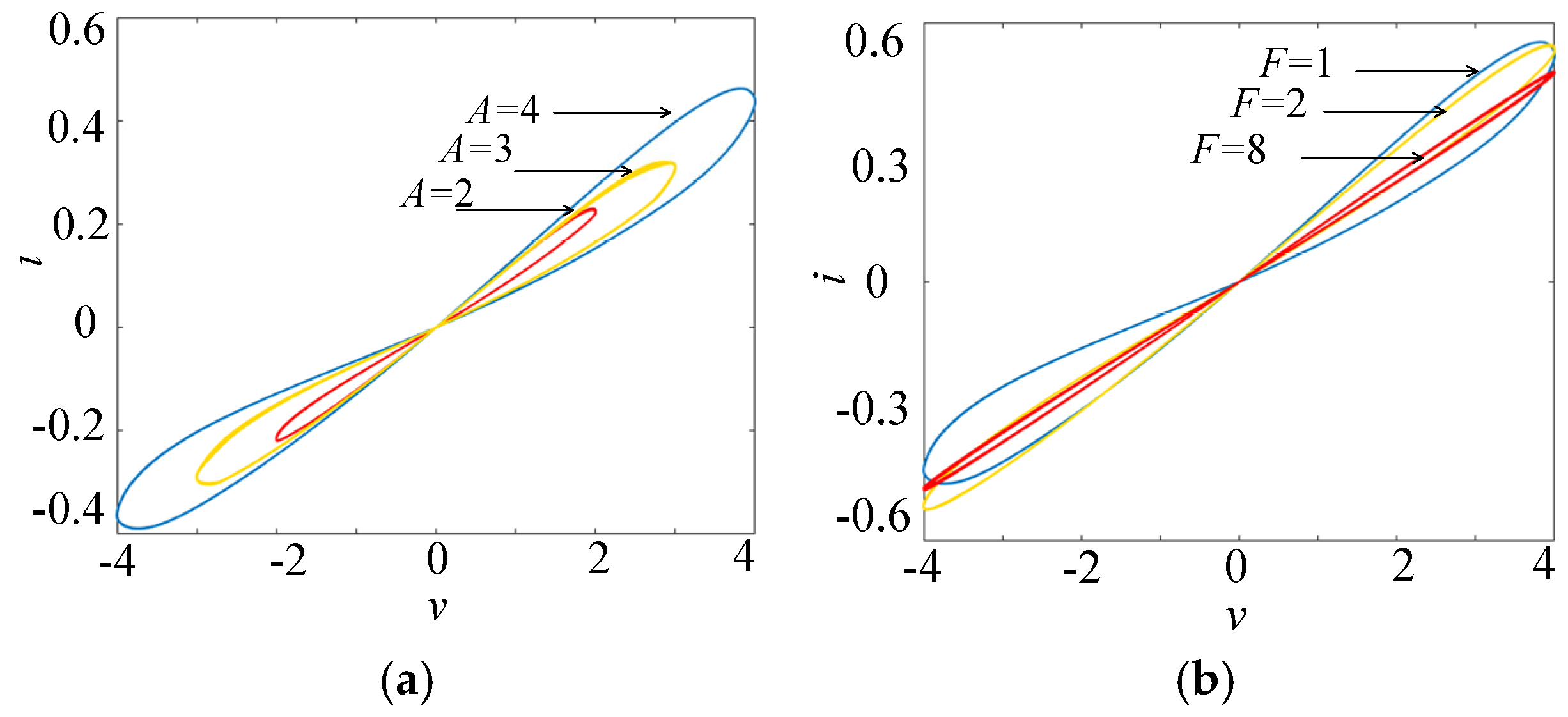

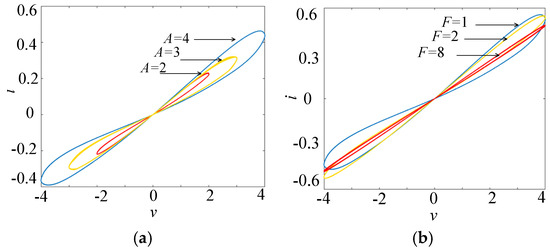

Set α = 0.1, β = 0.01, c = d = 1, N = 1. When v = Asin(Ft), the volt–ampere characteristics of the multi-stable memristor under different voltage amplitudes and frequencies are analyzed. Let x0 = 0, F = 1, and take the voltage amplitudes as 2, 3, and 4, respectively; the volt–ampere characteristic curves of the multi-stable memristor are shown in Figure 1a. Let x0 = 0, A = 4, and take the voltage frequencies as 1, 2, and 8, respectively, the volt–ampere characteristic curves of the multi-stable memristor are shown in Figure 1b.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the tight hysteresis loop of the multi-stable memristor. (a) x0 = 0, F = 1. (b) x0 = 0, A = 4.

As shown in Figure 1, when a bipolar sinusoidal signal is applied across the memristor, the memristor will generate a tight hysteresis loop passing through the origin of the voltage–current plane. Figure 1a indicates that when the excitation signal frequency and the initial state remain unchanged, the area of the tight hysteresis loop increases with the increase in the excitation signal amplitude. Figure 1b shows that when the excitation signal amplitude and the initial state are constant, the area of the tight hysteresis loop gradually decreases with the increase in the excitation signal frequency. A large number of simulation results show that when the excitation signal frequency increases to infinity, the tight hysteresis loop of the memristor tends to a linear single-valued function. Therefore, the proposed mathematical model has the three characteristics of the memristor. That is to say, it is a memristor.

- (2)

- Multistability

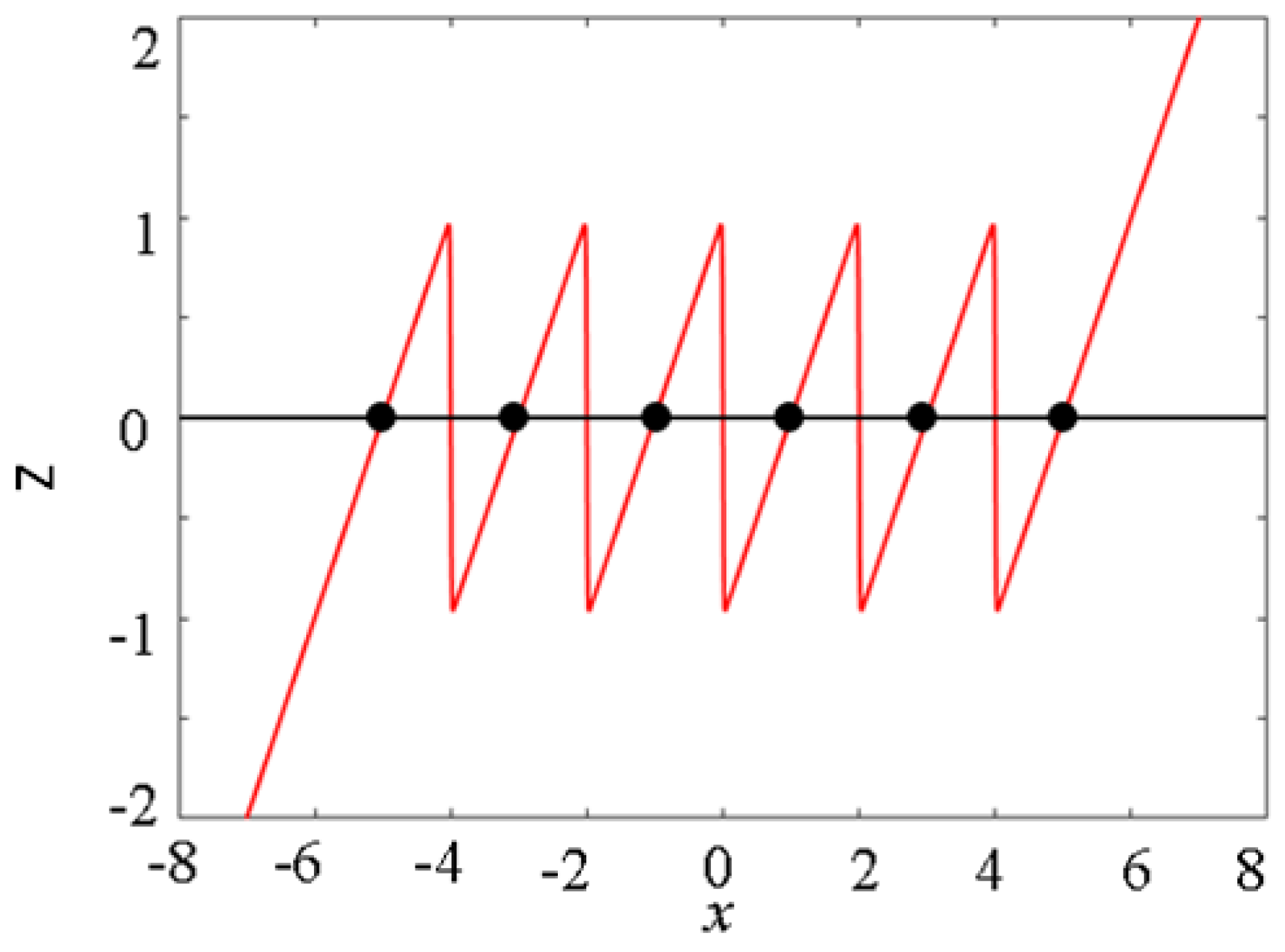

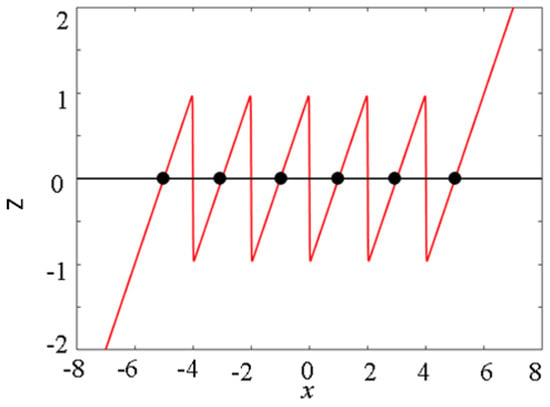

The multistability of the multi-stable memristor can be analyzed using the POP diagram. Let v in Equation (2) be 0 and M = 2. The state equation of the multi-stable memristor can be expressed as

The dynamic equation of the memristor (6) is shown in Figure 2, which is the POP diagram. Clearly, in the POP diagram of the multi-stable memristor, there are six unstable equilibrium points with negative slopes. According to the stability judgment method, the equilibrium points marked with circles are unstable. Obviously, at this time, the memristor has multiple unstable equilibrium points and exhibits multi-stable non-volatile characteristics. Moreover, when the control parameters N and M take different values, the dynamic trajectory of the multi-stable memristor tends to different stable equilibrium points under different initial conditions, that is, it has multiple state values.

Figure 2.

Pop plot of the multi-stable memristor.

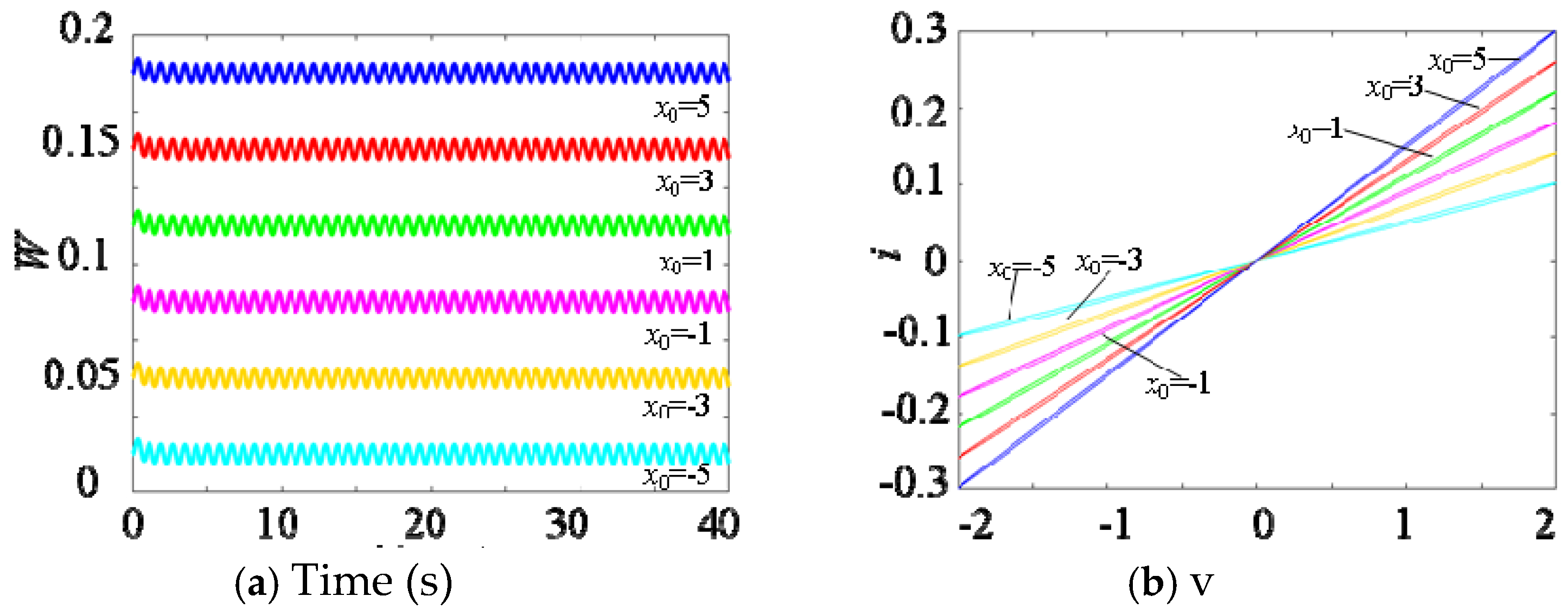

When A = 2 and F = 8, for different initial states −5, −3, −1, 1, 3, 5, the different tight hysteresis loops of the multi-stable memristor are shown in Figure 3. Figure 3a shows the transconductance values of the memristor under different initial states. Clearly, the memristor has multiple different transconductance values. Obviously, it is also non-volatile because multiple transconductances can represent multiple memory states.

Figure 3.

Numerical simulation results of multi-stable memristor. (a) Memristance. (b) Tight hysteresis loop.

3. Chaotic Dynamics Analysis

3.1. Construction of Mathematical Model

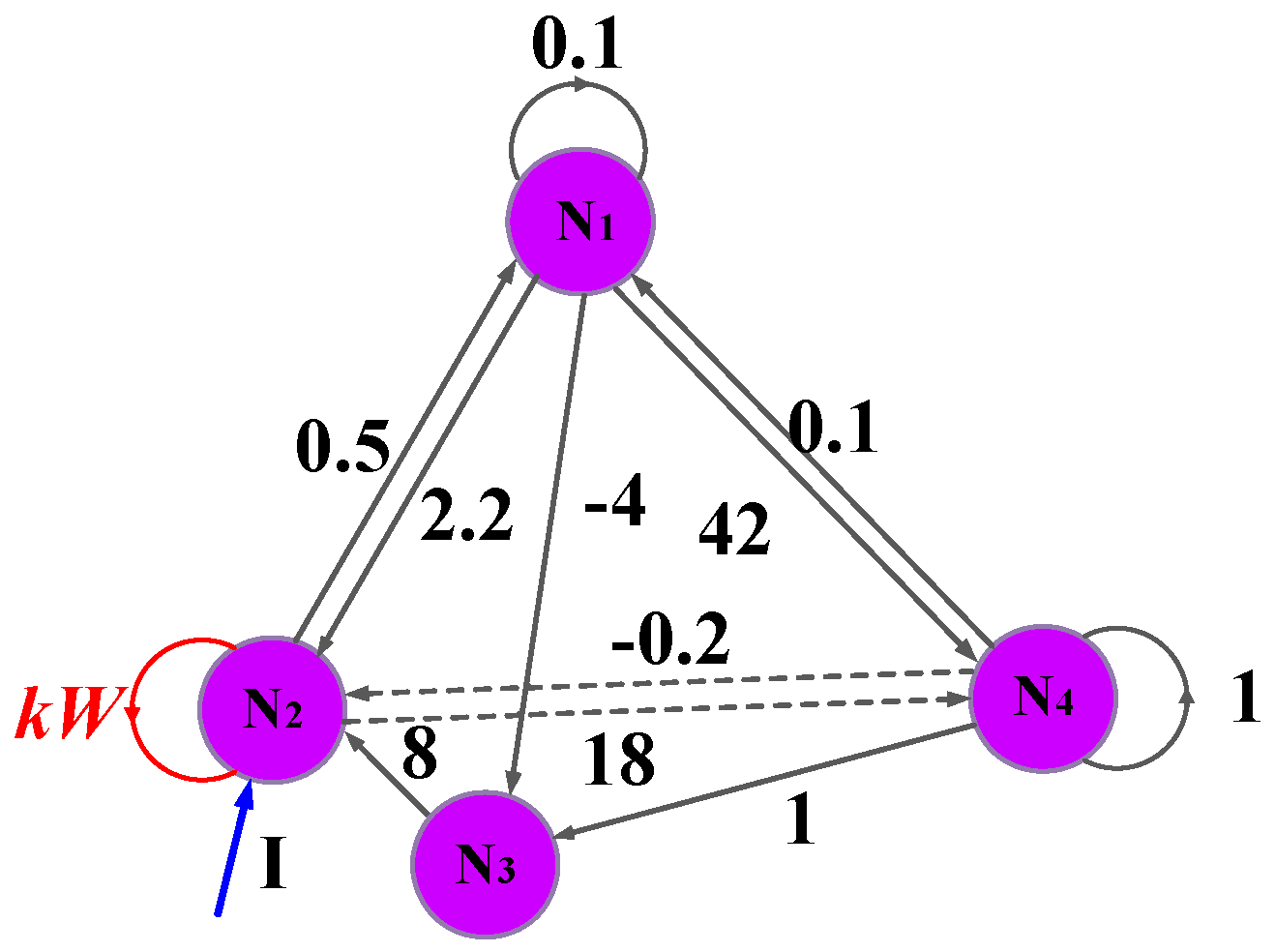

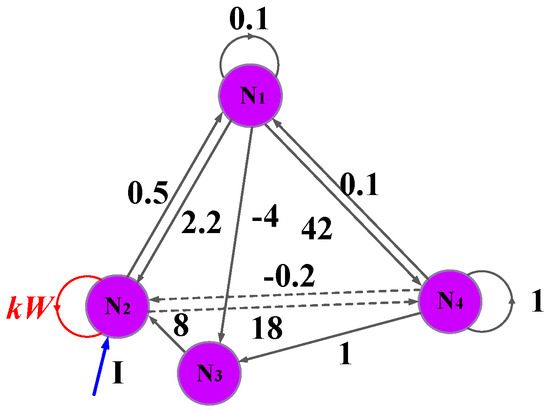

The Hopfield neural network possesses rich nonlinear dynamic characteristics and can be used to simulate the electrical activity behavior of the brain. From the mathematical model (2.33) of the Hopfield neural network, wij represents the conductance quantity, and in the neural network circuit, it is usually realized by the conductance of a resistor. However, according to the memristor theory, the rememorization conductance of the memristor is also of the conductance dimension. Therefore, the conductance of the resistor can be replaced by the conductance of the memristor to implement the synaptic weight coefficient wij. Based on this theory, in this section, a multi-stable memristor is used to simulate neural synapses, and a memristor Hopfield neural network is proposed. Its topological structure is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Topology diagram of memristive neural network.

This memristive neural network contains four neurons. Among them, the self-synaptic of neuron 2 is equivalent to a memristor, with the synaptic weight being w22. Combining the multi-stable memristor model in Equations (1) and (2) and the Hopfield neural network model in Equation (6), setting Ci = 1 and Ri = 1, the dynamic equation of the multi-stable memristor Hopfield neural network can be expressed as

Among them, “W = z” represents the self-synaptic weight w22 of neuron 4, and the system parameter k represents the coupling strength between the memristor and the neuron. By setting the right side of Equation (6) to 0, the equilibrium equation of the multi-stable memristive neural network is obtained as

We solved the equilibrium Equation (7) using numerical methods. Specifically, we employed the fsolve algorithm in MATLAB R2021a, starting the search from a set of initial guess values distributed along the z-axis within the interval [−8, 8]. Subsequently, the stability of each obtained equilibrium point E* was determined by checking the eigenvalues of the corresponding Jacobian matrix J(E*).

A discernment, attainable from the deductions of Equation (7), yields that when the external stimulus denoted by I assumes a positive value, within this systemic framework does not reside any point of equilibrium. The absence herein generates an attractor of concealed nature—an entity divergent from self-excited chaotic phenomena emanating proximally to states lacking stability and equilibria. This unpredictable behavior emerges as a product derived from the extensive reconfiguration of phase space—a consequence effected by its basin—and presents substantial complexity in both predictability and analyzation processes.

Equilibrium Point Analysis and the Origin of Hidden Attractors

This study conducted a numerical equilibrium point analysis to rigorously investigate the dynamic properties of the memristive HNN. The equilibrium point equation F(X) = 0 was solved using the fsolve algorithm in MATLAB. When the external stimulus was zero, the system exhibited several main equilibrium points distributed along the z-axis, including E1 = [0, 0, 0, 0, 1], E2 = [0, 0, 0, 0, −1], E3 = [0, 0, 0, 0, 3], and E4 = [0, 0, 0, 0, −3]. These points were concentrated near z = ±1, ±3, which fully met the original design intention of the memristor’s multistability. Each equilibrium point corresponded to a vortex structure of a chaotic attractor.

The key finding was that the equilibrium points of the system underwent a drastic migration after the application of external stimuli. They moved to new positions such as E1 = [−0.003354, −0.007268, 0.006149, −1.055714, 1.006149], E2 = [−0.003348, −0.007254, 0.006138, −1.054884, −0.993862], E3 = [−0.003361, −0.007281, 0.006161, −1.056547, 3.006161], and E4 = [−0.003342, −0.007241, 0.006126, −1.054057, −2.993874]. This displacement was fundamental. Because the positions and stability of the equilibrium points underwent very essential changes.

Then we evaluated the stability by calculating the eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix. For the E1 point when I = 0.2, the eigenvalues are λ1 = 1.0863 + 1.2913i, λ2 = 1.0863 − 1.2913i, λ3 = −0.7170, λ4 = −4.2014, and λ5 = −4.1590. There are two positive real part eigenvalues, which clearly confirm that all equilibrium points are unstable saddle points. The other equilibrium points also exhibit exactly the same unstable characteristics.

Therefore, this leads to the most fundamental conclusion: although equilibrium points exist, they are all unstable. More importantly, the complex multi-turbulent chaotic attractors presented in this paper are not derived from the stable manifolds of these unstable equilibrium points. They arise in the attractor domains that are topologically completely separated from the stable manifolds of the equilibrium points. This phenomenon of chaotic attractors coexisting with unstable equilibrium points without any connection fully satisfies the formal definition of hidden attractors [14]. The significant displacement of equilibrium points caused by external stimuli, together with their instability, has created the complex dynamical picture required for the hidden multi-turbulent chaos that we have observed.

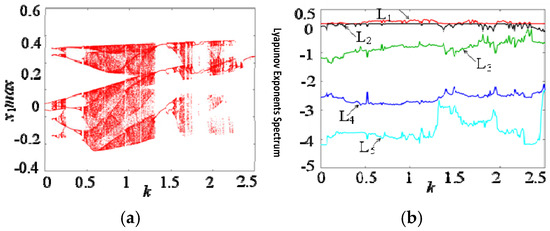

3.2. Hidden Multiple Attractor Control

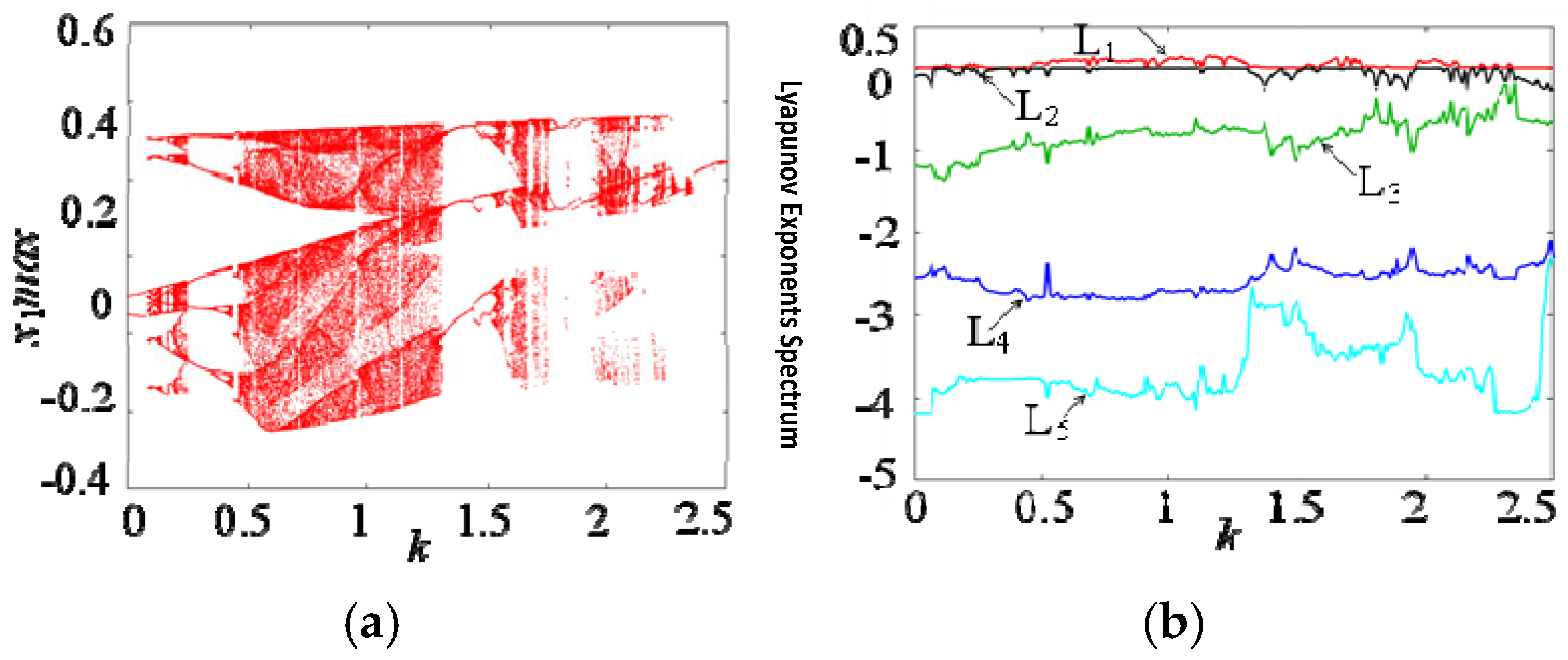

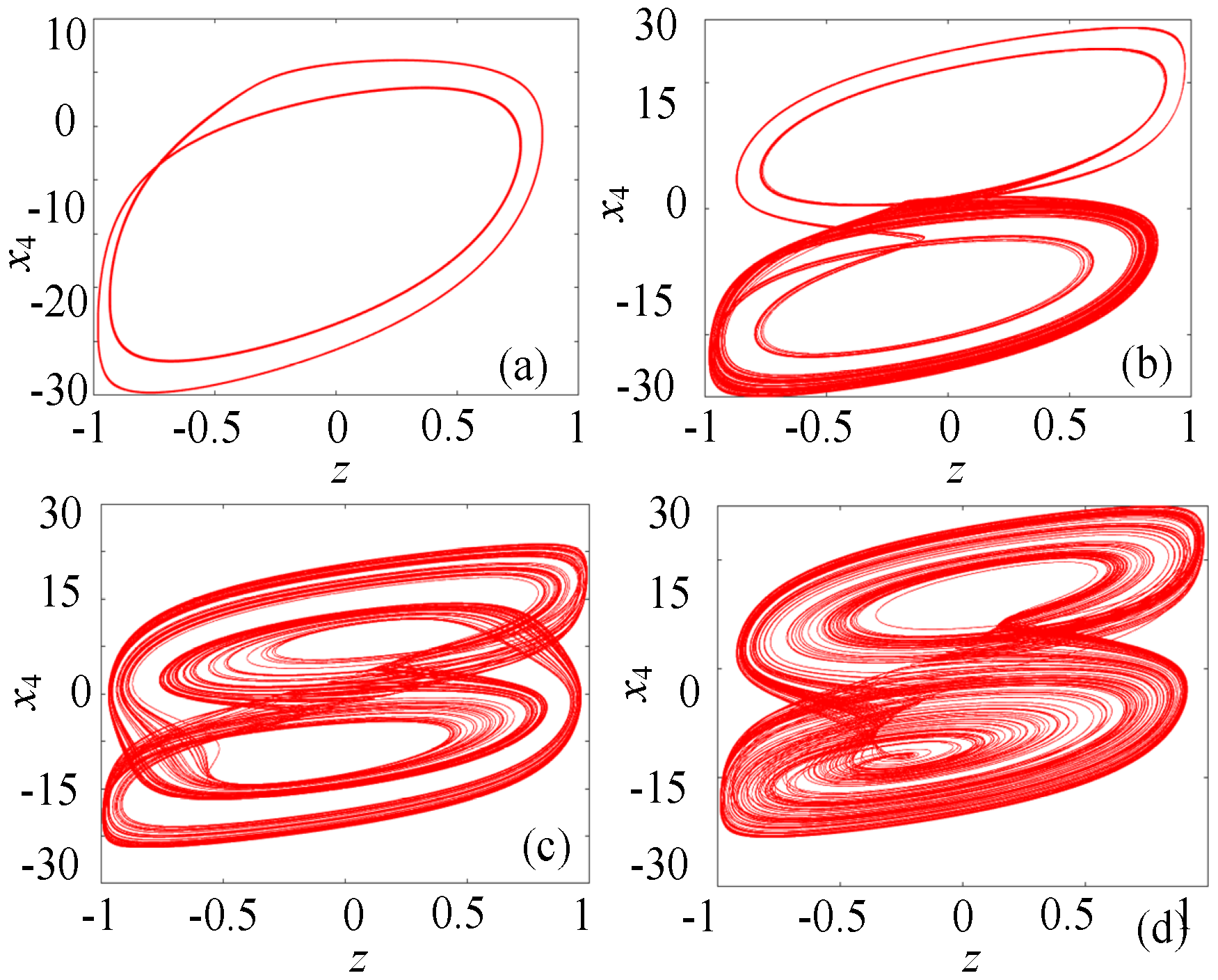

In order to deeply study the dynamical behavior of the proposed hidden multiple attractor memristive Hopfield neural network, the parameters α = 0.8, β = 0.01, c = 4.2, d = 4.2, I = 0.2, and N = 0 were set. When the initial state was (0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1), and the parameter k varied within the range of [0, 5], the bifurcation diagram and Lyapunov exponent spectrum of the memristive neural network were plotted, as shown in Figure 5a,b, respectively. From Figure 5a, it can be seen that as parameter k increases, the memristive neural network undergoes multiple multiplicative period bifurcations from the periodic state to chaotic behavior. For example, when k increases to 0.4, the hidden multiple attractor memristive neural network completely enters a relatively stable chaotic state. Then, at k = 1.4, it again passes through chaotic crisis and reverts to a periodic state. Subsequently, it undergoes multiple multiplicative period bifurcations and reenters the chaotic state, finally decaying to a periodic state at k = 2.4. Figure 5b further proves the dynamical state shown in Figure 5a from the perspective of the Lyapunov exponent spectrum. Through numerical simulation, the hidden chaotic attractors under different memristor coupling strengths can be obtained, as shown in Figure 6. When k = 0.01, the system generates a single attractor periodic attractor, as shown in Figure 6a. When k = 0.1, the system generates a double attractor periodic attractor, as shown in Figure 6b. When k = 0.45, the system generates a double attractor quasi-periodic attractor, as shown in Figure 6c. When k = 0.6, the system generates a double attractor chaotic attractor, as shown in Figure 6d. Figure 6 indicates that the dynamical trajectory of this memristive neural network develops from periodic to chaotic gradually, which is consistent with the analysis results of the bifurcation diagram. The presence of chaos is verified using multiple numerical criteria. First, a positive Largest Lyapunov Exponent (LE) at parameters like k = 0.6 provides direct quantitative evidence of sensitive dependence on initial conditions. Second, the Fourier transform of the chaotic time series yields a continuous broadband spectrum, a hallmark of deterministic chaos distinct from periodic signals. Third, the phase portraits (Figure 6d, Figure 7b and Figure 8) exhibit the complex, bounded, and non-periodic trajectories—specifically, double-scroll and multi-scroll formations—that are emblematic of chaotic attractors. The consistent agreement among the bifurcation diagram (Figure 5a), the Lyapunov exponent spectrum (Figure 5b), and the phase portraits collectively and robustly substantiates the existence of chaos in the proposed memristive HNN.

Figure 5.

Bifurcation diagram and Lyapunov exponent spectrum varying with parameter k. (The author created the diagram based on Matlab). (a) Bifurcation diagram. (b) Lyapunov exponent spectrum.

Figure 6.

Phase diagram of the memristive neural network under different parameters k. (a) Periodic single-scroll. (b) Periodic double-scroll. (c) Quasi-periodic double-scroll. (d) Chaotic double-scroll.

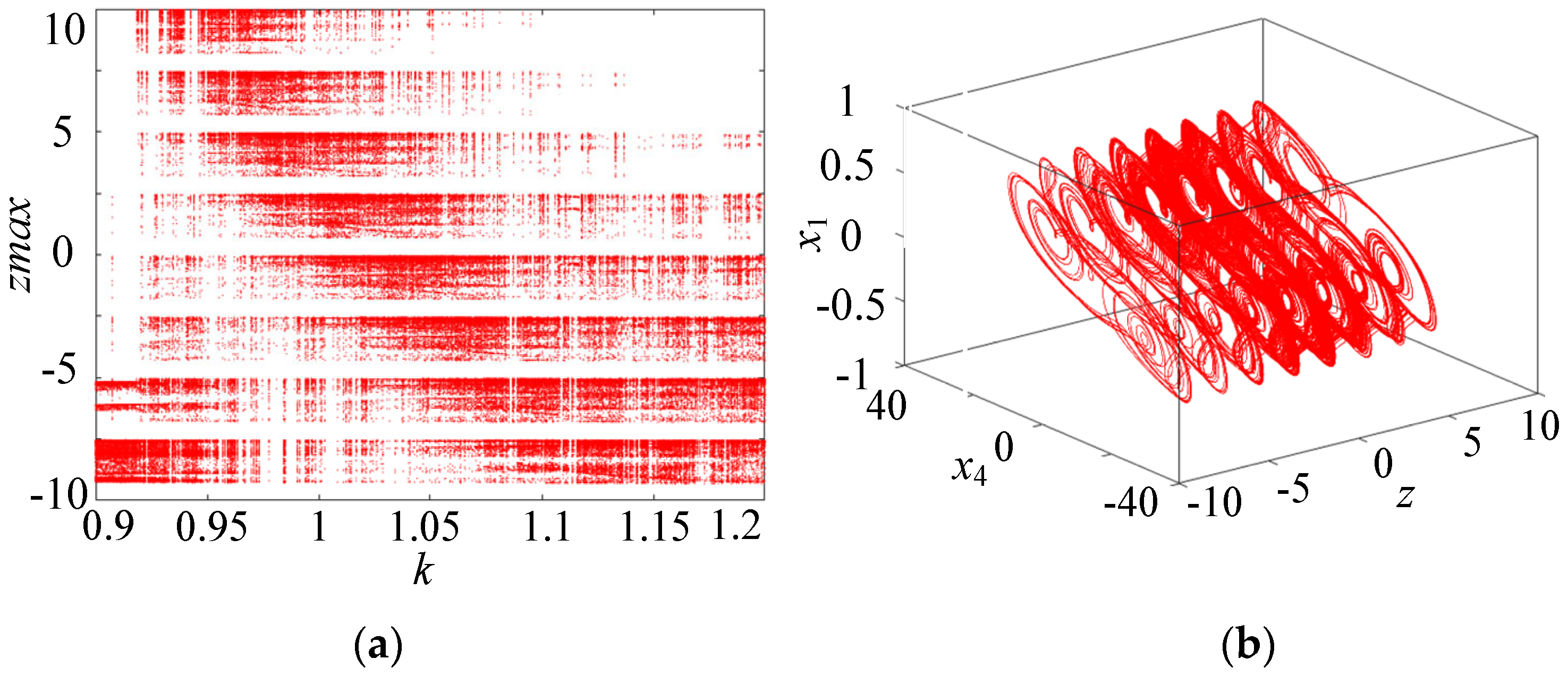

Figure 7.

Bifurcation diagram and three-dimensional phase diagram. (a) Bifurcation diagram. (b) Hidden eight-shaped double-scroll attractor.

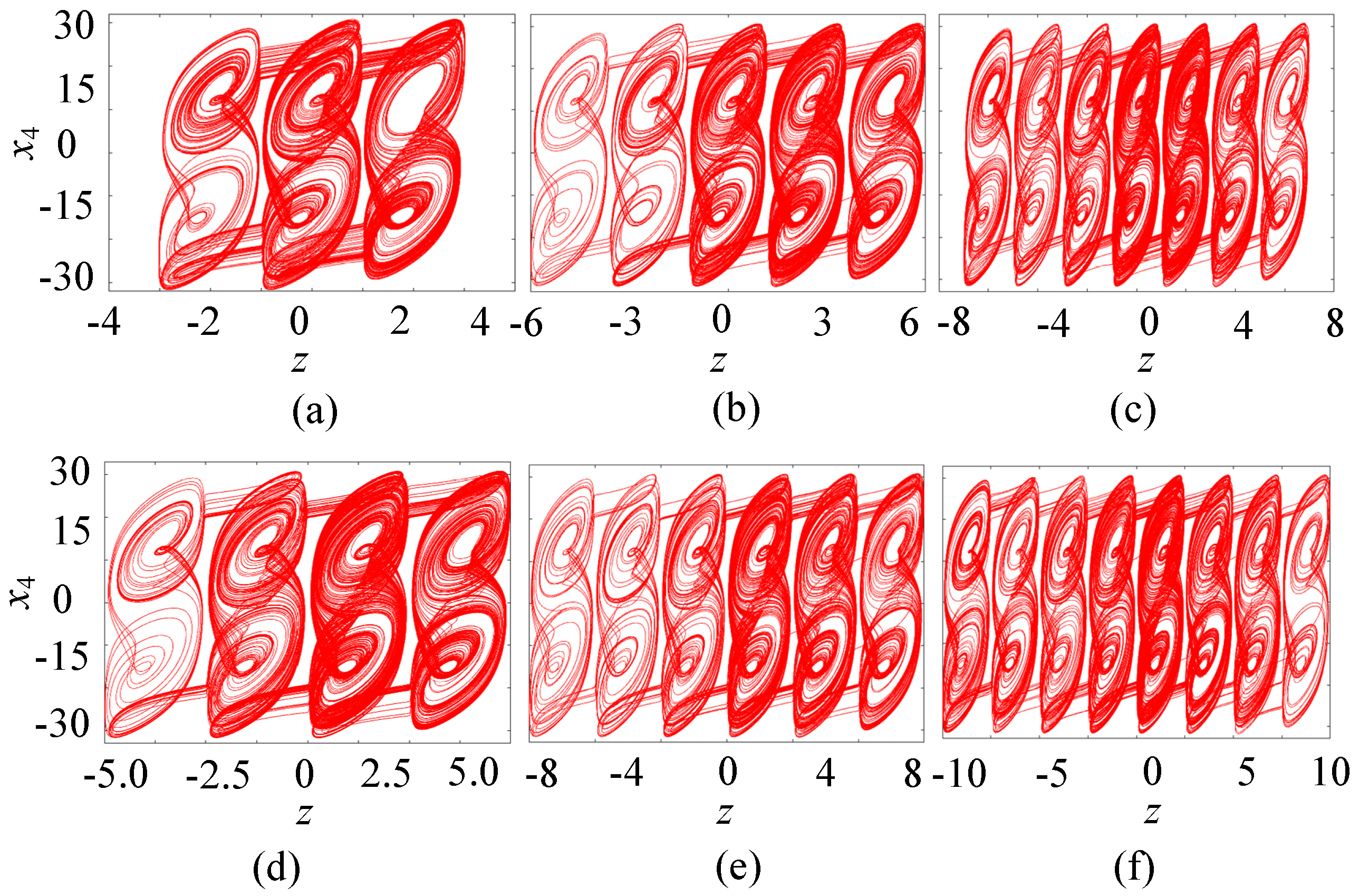

Figure 8.

Different numbers of hidden multiple chaotic attractors. (a) Three-double-scroll chaos. (b) Five-double-scroll chaos. (c) Seven-double-scroll chaos. (d) Four-double-scroll chaos. (e) Six-double-scroll chaos. (f) Eight-double-scroll chaos.

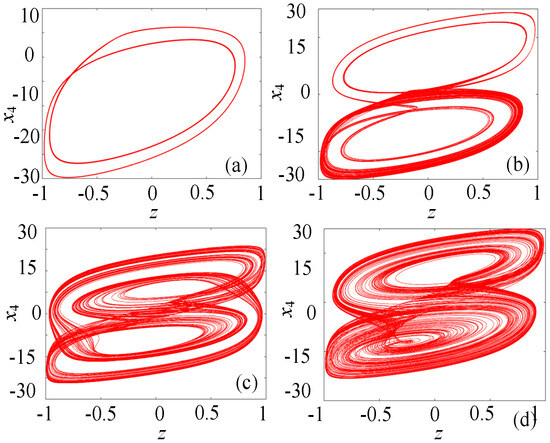

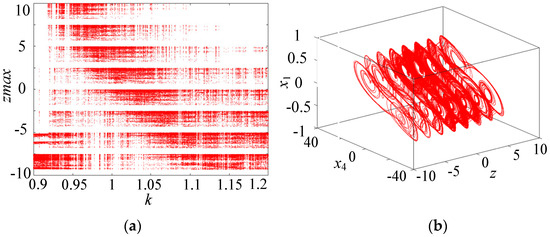

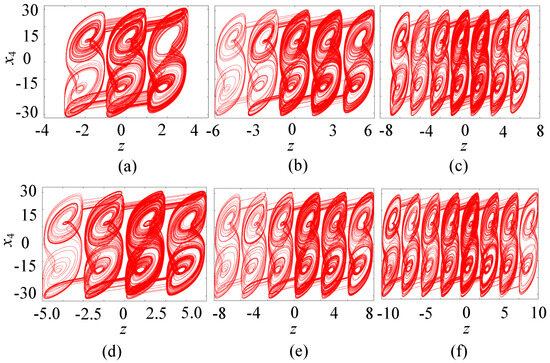

Numerical simulations show that this resistive Hopfield neural network can generate any number of hidden multiple attractor chaotic attractors. Keeping the above system parameters unchanged, setting M = 3, and varying the parameter k within the range of [0.9, 1.2], the bifurcation diagram of the resistive neural network with the resistive component zmax is plotted as shown in Figure 7a. The bifurcation diagram consists of a series of band-shaped points of amplitude diagrams, thus generating multiple attractor phases in the z direction of the system. Letting k = 1, the system can produce a hidden eight-double-scroll chaotic attractor, as shown in Figure 7b. Moreover, by choosing different control parameters N or M values, any number of hidden multiple attractor chaotic attractors can be generated, as shown in Figure 8. When N is, respectively, set to 1, 2, and 3, the resistive neural network can produce three-, five-, and seven-double-scroll attractors, respectively, as shown in Figure 8a–c. When M is, respectively, set to 1, 2, and 3, the resistive neural network can produce four-, six-, and eight-double-scroll attractors, respectively, as shown in Figure 8d–f. Clearly, the number of double-scrolls produced by the resistive neural network can be controlled by 2N + 1 and 2M + 2. Therefore, this resistive neural network can generate any number of hidden double-scroll chaotic attractors, with complex hidden multiple attractor dynamical behaviors.

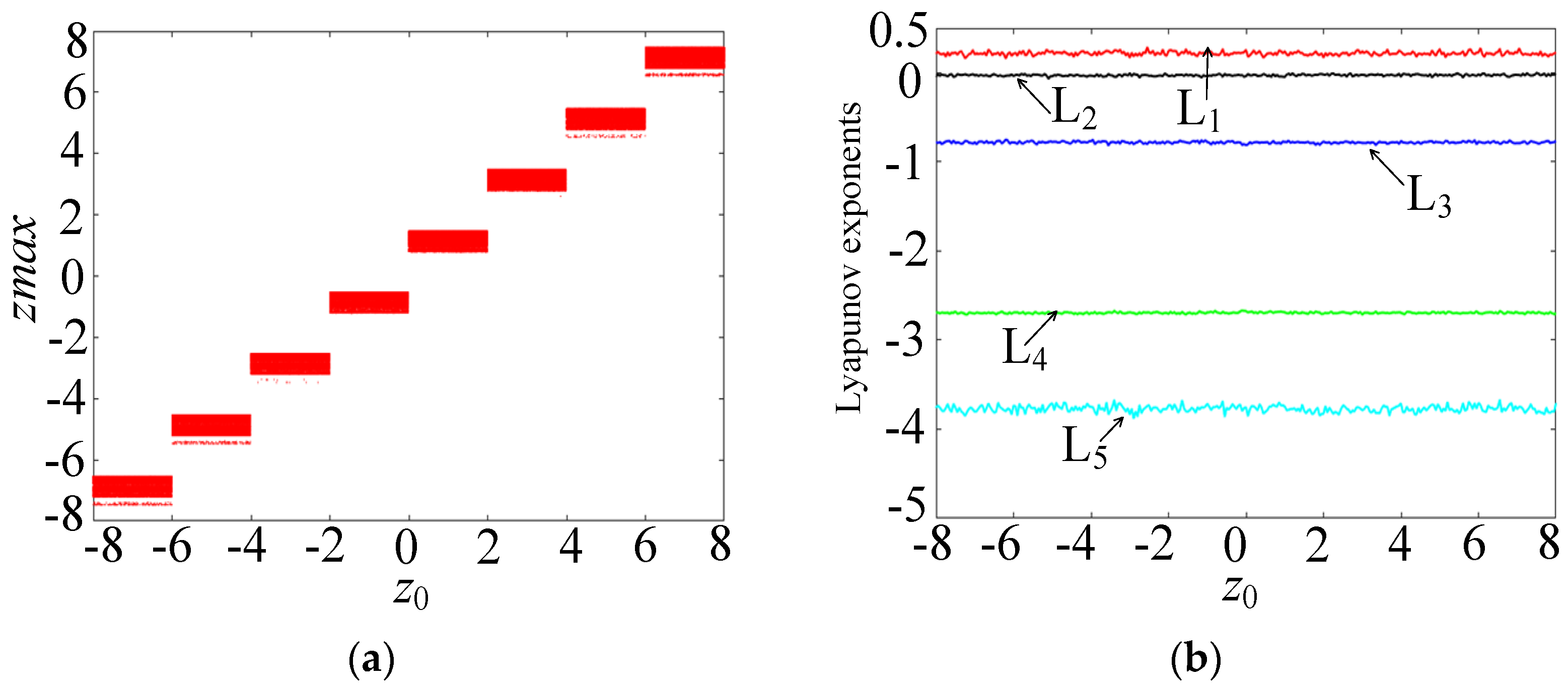

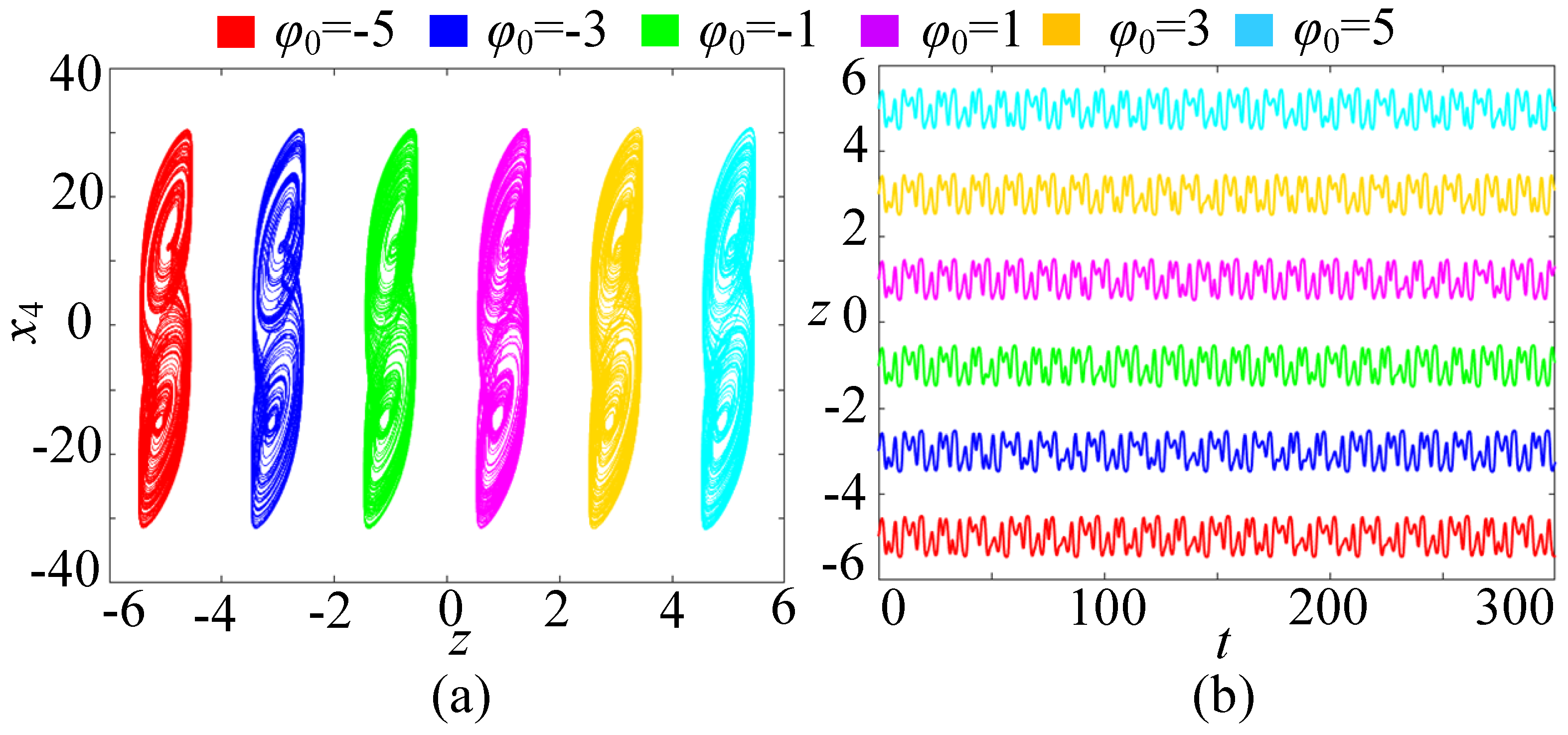

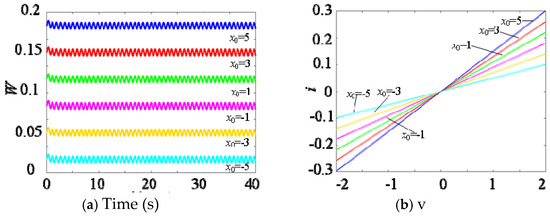

3.3. Super-Steady-State Behavior

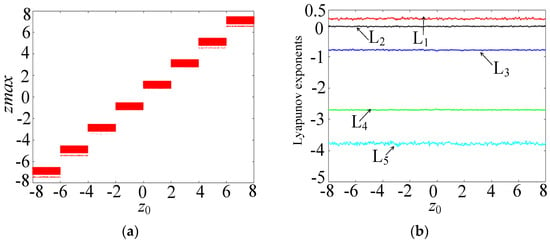

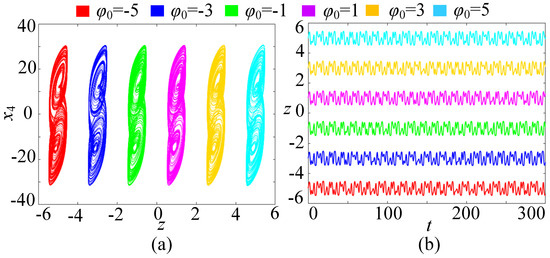

In order to further study the dynamical behavior of the memristive Hopfield neural network, when the parameters c = 2, k = 1, M = 3, and the initial state (x10, x20, x30, x40) is (0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1), and the initial value z0 varies within the range of [−8, 8], the bifurcation diagram and Lyapunov exponent spectrum of the memristive neural network are plotted, as shown in Figure 9a,b, respectively. From Figure 9a, it can be seen that there are multiple rectangular regions in the bifurcation diagram, with the same amplitude but different positions. Each rectangular region can evolve into a separate attractor. Moreover, from Figure 9b, it can be seen that the memristive Hopfield neural network has a Lyapunov exponent that is always greater than 0, which means it can generate continuous robust chaos. Therefore, this system can produce the dynamics of initial value offset regulation, that is, it has an extremely high number of stable states. When z0 = ±1, ±3, and ±5, the phase diagrams of the six coexisting double-scroll attractors and the corresponding time series of the state z are shown in Figure 10. In Figure 10a, the six coexisting attractors are distributed along the z-axis, with the same structure but different positions. In fact, when N→∞ and M→∞, an infinite number of coexisting double-scroll attractors can be generated. Moreover, in Figure 10b, the chaotic sequence has robustness and can maintain chaos, and its oscillation amplitude can be controlled without loss by adjusting the initial value of the memristor. This characteristic is of great significance in practical applications, as it can provide a large number of lossless and robust chaotic sequences for secure communication based on chaos.

Figure 9.

Bifurcation diagram and Lyapunov exponent spectrum as a function of z0. (a) Bifurcation diagram. (b) Lyapunov exponent spectrum.

Figure 10.

Initial deviation amplification phenomenon. (a) Six coexisting double-scroll attractors. (b) Time series.

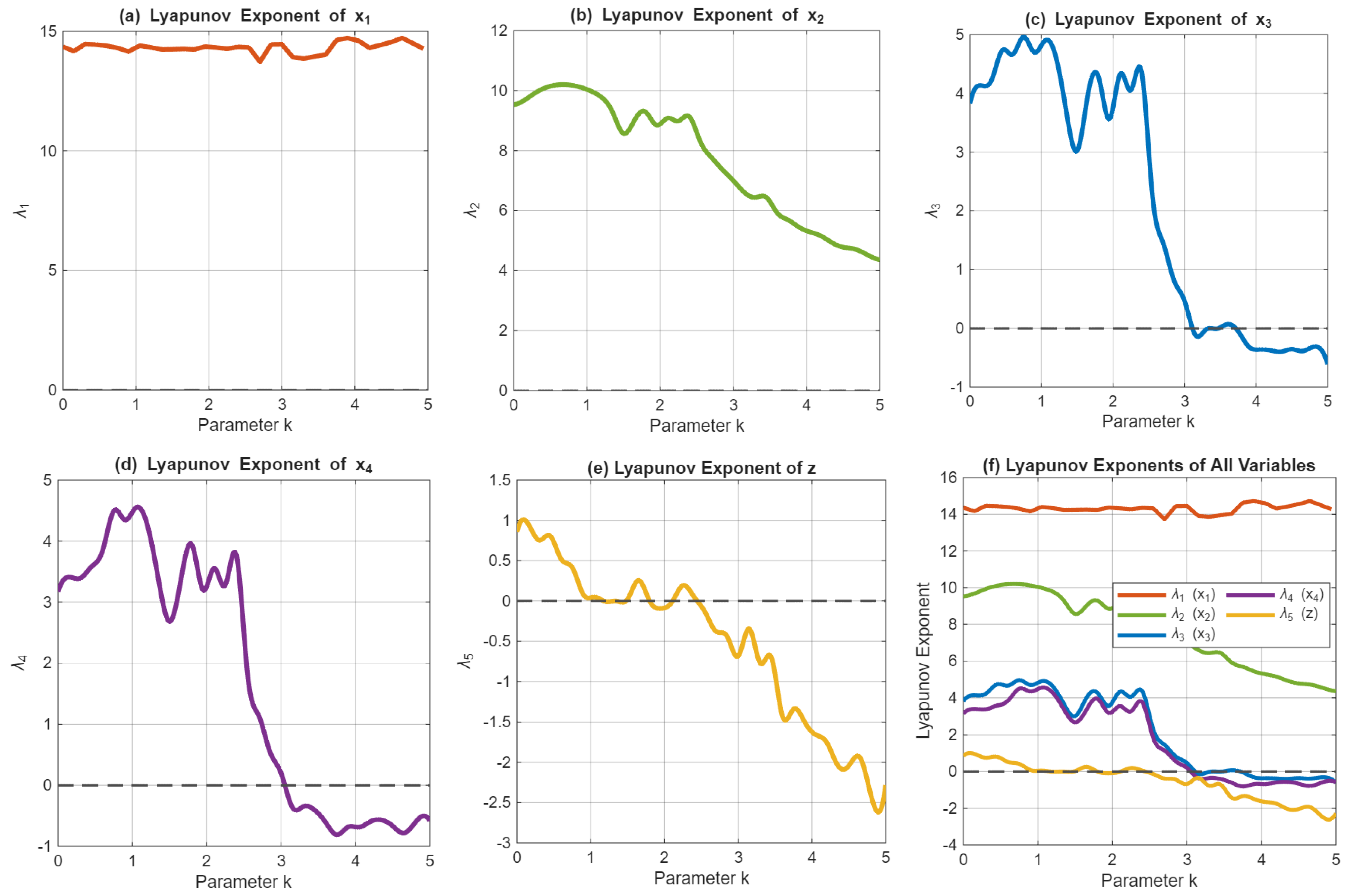

3.4. Lyapunov Exponents Analysis of Memristive HNN Hyperchaotic System

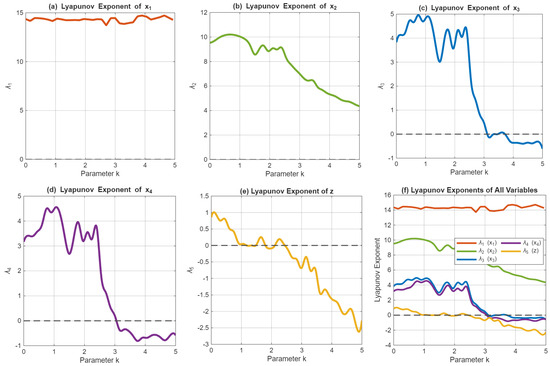

A spectrum of Lyapunov exponents reveals a complex dynamic landscape within the memristive HNN system as the parameter (k) is altered from 0 extending up to 5, as shown in Figure 11. A transition occurs in the system’s trajectory—from periodic states evolving into chaos with the interval defined where (1.0 < k < 2.0)—and further delving into an identified hyperchaotic phase existing between (2.0 < k < 3.5), notable for two positive exponent values, before reverting to a more periodic nature. Stability is imparted by the memristor state z, which steadfastly maintains a negative exponent. Manifested here and especially evident in its robust hyperchaos is an indication not only of intricate system dynamics but also the underscoring of potential superior utility of the system in secure communications.

Figure 11.

Lyapunov exponents spectrum of the memristive HNN chaotic system. (a) Lyapunov exponent of the first state variable. (b) Lyapunov exponent of the second state variable. (c) Lyapunov exponent of the third state variable. (d) Lyapunov exponent of the fourth state variable. (e) Lyapunov exponent of the memristor state. (f) Complete Lyapunov exponent spectrum (the figure was generated using MATLAB).

Parameters: α = 0.8, β = 0.01, c = 4.2, d = 4.2, I = 0.2, M = 3, p = 100; initial conditions: X(0) = [0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1]T.

3.5. Comparative Analysis: The Role of the Multi-Stable Memristor

Seeking clarity in elucidating the singular contributions rendered by this scholarly endeavor, herein is established a systematic juxtaposition of dynamical proficiencies inherent between the proposed multi-stable memristor-endowed Hopfield neural network (HNN), and peer contemporary architectures cataloged within academic treatises. As reflected in Table 2, the output of said comparative analysis stands encapsulated.

Table 2.

Comparative analysis of dynamical capabilities in neural network architectures.

Within the realm of memristive quantum networks, substantial progress has surfaced, indicating complexities such as hyperchaos discernible through memristive-coupled neural congregations [12], in tandem with multiple double-scroll attractors showcasing extremities of multistability within a memristive HNN context [18]. Scrutinized from Table 2, it becomes evident that occurrences of hidden multiple attractors, articulated under this present scope, remain unparalleled in antecedent discourses. Furthermore, whilst observations abound regarding extreme multistability [18], the system at hand ushers forth an unprecedented superlative state—termed ‘super multistability’—wrought from infinite coexistence among discrete double-scroll chaotic attractors delineated along the axis of varying state variables; a construct hitherto undocumented.

Numerical exposition chronicled across Section 3.2 and Section 3.3 lays bare our system’s prowess not only mirroring hyperchaotic dynamics [12] akin to extant studies but also harnessing intricate multi-stable evolutions [18]; yet, more critically, meticulous programmable adjustments governing scroll quantity vis-à-vis parameters N and M are achieved. Paramount, however, is when observing our introduction, which is foundationally novel amidst memristive HNNs of concealed multiple attractors (detailed in Section 3.2 alongside Figure 7 and Figure 8); concomitantly, it offers distinctively programmable super multistability forms as evidenced throughout Section 3.3 coupled with Figure 9 and Figure 10.

From these collated observations emerges an assertion positing hidden multiple attractors as intrinsic phenomena attributed uniquely to the specially designed multi-stable memristor paradigm instantiated within this research, hence demarcating its essential pertinency beyond existing synaptic archetypes.

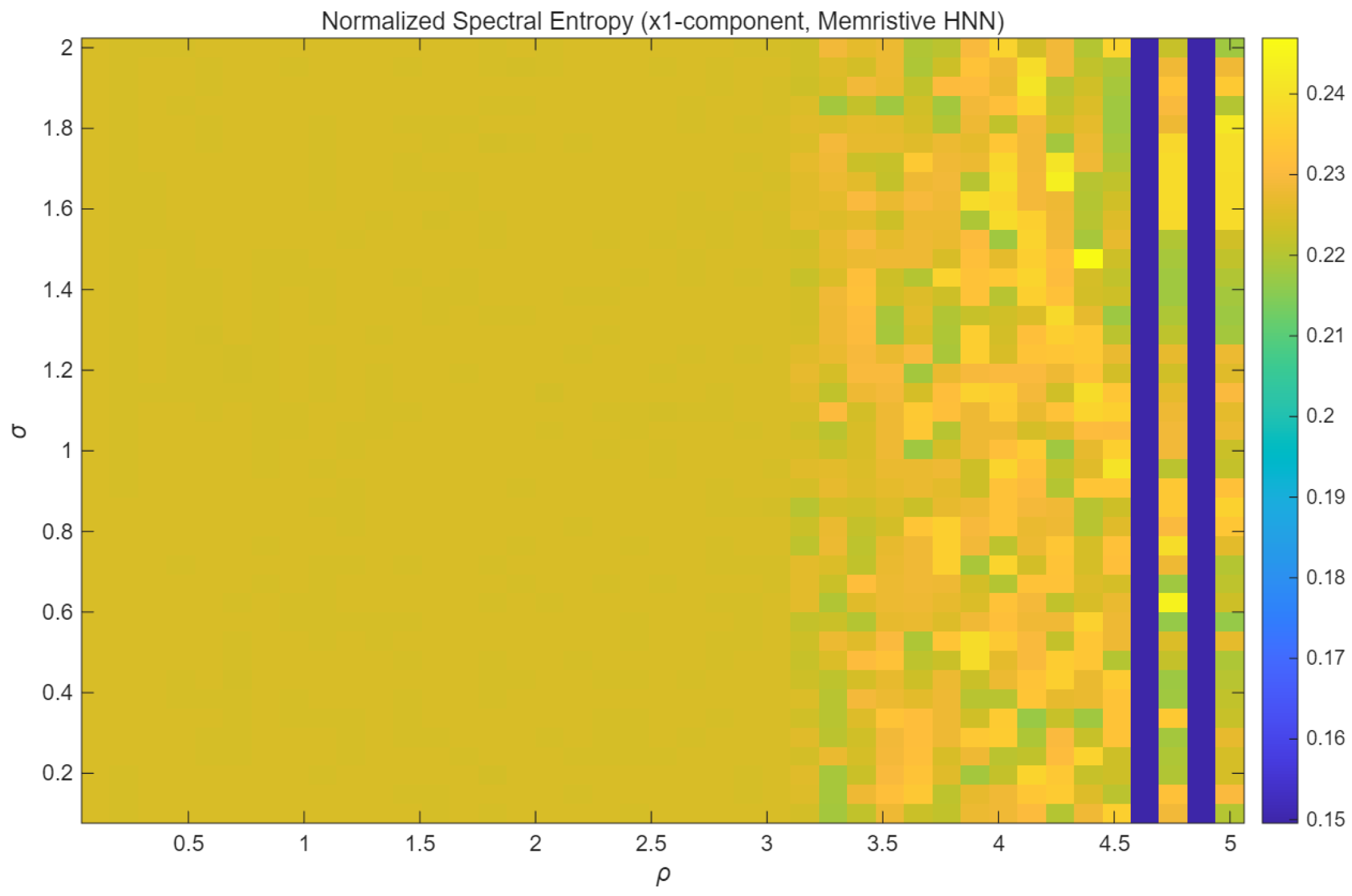

3.6. Complexity Analysis

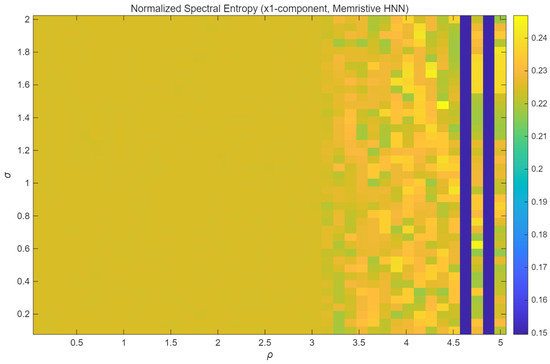

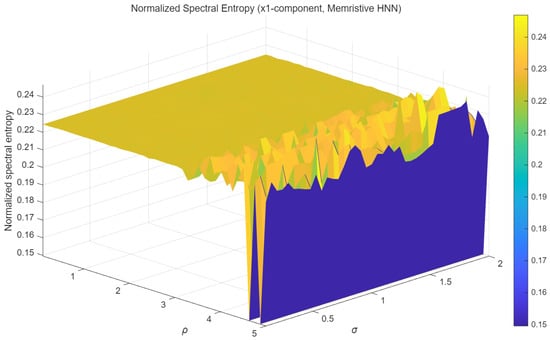

To evaluate the dynamical characteristics and complexity of the attractors of the memristive HNN in this chapter, the normalized spectral entropy of the x1-component is calculated. Spectral entropy is an effective metric for measuring the randomness of a time series in the frequency domain. The higher it is, the more complex the dynamic behavior of this system is. This means that the security of the encryption application is also higher.

As shown in Figure 12 (presented in a heatmap format), the numerical distribution characteristics of the normalized spectral entropy can be visually displayed. The horizontal and vertical axes correspond to the two-dimensional parameter space formed by the coupling strength σ and the memristor parameter p. The high-entropy region (with values exceeding 0.21) occupies a significant area in the parameter plane. For example, when the parameter p is within the range of 1.5 to 3.5 and σ is within the range of 1.6 to 2.0, this is the case. The stability of the chaotic state of this system is thus verified, manifested by its high tolerance to parameter changes.

Figure 12.

Heatmap.

Figure 13 shows the regular characteristics of the spectral entropy value as the memristor parameter p changes, when the coupling strength σ remains constant. When p is within the range [1.0, 2.0], it can be observed that the spectral entropy always remains at a relatively high level (>0.22). The example demonstrates that this phenomenon arises from the fully activated process of the nonlinear characteristics of the memristor device, and is particularly significant within this parameter range. Thus, it can be seen that the operation of the entire neural network is provided with a relatively stable chaotic source.

Figure 13.

Two-dimensional curve graph.

In conclusion, the spectral entropy analysis quantitatively confirms that the memristive HNN proposed in this paper can stably maintain a high-complexity chaotic state within a wide range defined by parameters p and σ. This high robustness to parameter changes lays a solid dynamical foundation for the construction of a highly reliable image encryption scheme in Section 4.

4. Color Image Encryption Application

Chaotic systems with hidden attractors and multiple attractor structures possess flexible adjustability and high complexity, and have broader application prospects in information encryption [24]. This paper uses the hidden multiple attractor generated by the memristive Hopfield neural network to design a new color image encryption scheme and analyzes the test results.

4.1. Encryption Structure Design

4.1.1. Protocol for Cryptographic Encoding

The proposed encryption scheme is based on a spatiotemporally chaotic system, In this framework, the state variables x1(t), x2(t), x3(t), x4(t), and z(t) are used to form one-dimensional vectors. The length of each vector equals the total number of pixels in the corresponding color channel of the plain text image, creating a direct mapping between the chaotic sequence and the image data. Initiation step: Generation of chaotic sequences exhibiting multi-scroll dynamics.

Step I: The process begins by initializing the memristive HNN with the initial state X(0) = [0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1]T and parameters α = 0.8, β = 0.01, c = 4.2, d = 4.2, I = 0.2, M = 3. To eliminate transient effects, the first 500 iterations (using an integration step of 0.001) are discarded. The system subsequently settles into an eight-scroll chaotic attractor. From such stabilization arise multi-dimensional trajectories of chaos [x1(t), x2(t), x3(t), x4(t), z(t)], ensuring they serve adequately as sources rich in entropy.

Step II: Construction of Pseudo-random Keystream.

The generated chaotic sequences are combined and then discretized, both essential steps culminating in the production of a uniformly distributed keystream. The pseudo-random keystream value k(t) at each discrete time step is generated by the following nonlinear transformation: k(t) = mod(floor((|x1(t)| + |x2(t)| + |x3(t)| + |x4(t)| + |z(t)|) × 1015, 256).

Notably, such processes facilitate the mapping of these high-precision chaotic values onto integers confined within the set [0, 255], thereafter generating a pseudo-random keystream whose properties align suitably for cryptographic applications.

This transformation projects the continuous chaotic dynamics onto a discrete integer domain while preserving ergodic properties, creating a pseudo-random keystream with uniform distribution.

Step III: Dual-layer Pixel Transformation.

The original color image P is decomposed into its red (PR), green (PG), and blue (PB) component matrices. Each component matrix is then flattened into a one-dimensional vector, denoted as pR(t), pG(t), and pB(t), respectively, where the index t corresponds to the pixel position in the vector.

This step consists of two consecutive operations: 1. Chaotic Permutation: A permutation sequence, index(k(t)), is generated by performing an argsort operation on the keystream k(t). This sequence defines a bijective mapping that globally shuffles the pixel positions. The permuted pixel vector for each channel is obtained by p1(t) = p(index(k(t))). This process destroys the strong spatial correlations inherent in natural images. 2. Bit-level Diffusion: The permuted pixel vectors p1(t) are then encrypted through a bitwise XOR operation with the pseudo-random keystream k(t):

This operation ensures that a minor change in the plain text leads to a significant, nonlinear change in the ciphertext, fulfilling the requirement for the avalanche effect.

Finally, the encrypted vectors CR(t), CG(t), and CB(t) are reshaped back into their respective two-dimensional matrices and merged to form the final encrypted color image C.

The extent of the training data carries relevance. Within this timeframe, one observes that permutation indices arising from the index function are generated after sorting the normalized keystream k(t), resulting in an execution of worldwide pixel shuffling. This permutation operation is subject to governance by the chaotic index sequence birthed from the keystream k(t); it enforces a bijective mapping—the deterministic rearrangement of pixel coordinates manifests. Properties of inherent reversibility characterize this process. Decryption requires associating with the application of the corresponding inverse permutation—exclusively determined by applying the inverse of the index function upon k(t)—leading ultimately to the restoration of original pixel coordinates into primitively spatial configurations.

The permutation operation globally shuffles the pixel positions of the image. The construct, delineated as index(k(t)), epitomizes a bijective mapping—a chaotic automorphism—crafted through the procedure of organizing the normalized keystream. From this, its reversibility can be perceived—the inverse mapping index−1(k(t)) exists unequivocally. This entity facilitates an accurate restoration of the initial spatial configuration during decryption by means of reversing the coordinate transformation engaged previously.

4.1.2. Decryption Protocol

Decryption is the symmetric inverse of the encryption process. It requires the same secret key to regenerate the identical chaotic sequences and keystream, which allows for the sequential reversal of the diffusion and permutation operations.

Stage I: Regeneration of Chaotic Sequence.

It can be observed herewith that recipients, wielding the very same secret key encompassing initial conditions alongside system-specific parameters, meticulously recreate the quintet-dimensional chaotic trajectories [x1(t), x2(t), x3(t), x4(t), z(t)], accompanied by the pseudo-randomly manifested keystream k(t). Herein, synchronization emerges paramount to this regenerative endeavor.

Stage II: Diffusion Inversion.

Disassembling commences with encrypted image C into its quintessential chromatic constituents—precisely CR, CG, and CB deciphered. Subsequently, each color’s component matrix transitions into one-dimensionality—flattened undeniably so. With intentions aimed at negating the diffusion effect, XOR operation similarly performed leveraging self-inversion inherent in keystream: p1(t) = C(t) ⊕ k(t). In designated p1(t), there is observed representation of the permuted pixel vector reflective upon every individual chromatic channel post-diffusion layer inversion.

Stage III: Permutation Reversal.

In the final stage, the inverse permutation is applied to reverse the pixel shuffling. The inverse index sequence, index−1(k(t)), is applied to the vector p1(t) to restore the original pixel order, producing the decrypted pixel vector p(t) for each channel.

Expression yields, henceforth, p(t) = p1(index−1(k(t))). Decrypted chromatic imagery P achieves reassembly via reshaping processes directing vectors pR(t), pG(t), and notably pB(t) relatively back into two-dimensional matrices subject to amalgamation intimately among them.

In conclusion, the decryption process is not merely a sequential reversal but constitutes a meticulous topological inversion of the encryption cascade. This symmetric reconstruction is predicated upon the possession of isomorphic initial conditions and system parameters, ensuring a precise unwinding of the cryptographic operations. The entire procedure can be conceptualized as a three-stage phenomenological restoration: initiating with Chaotic Resonance for keystream regeneration, progressing through Differential Deconstruction for bitwise reversion, and culminating in Topological Restoration for spatial realignment, thereby faithfully recovering the original information topology.

4.1.3. Cryptographic Topology in Memristive Neural Networks

The symmetric decryption mechanism functions as the inverse operation of encryption, necessitating the utilization of an identical cryptographic secret key for replicating the coherent sequences employed during the original encryption phase.

Decryption Mechanism Processes:

1. Chaotic Trajectories Regeneration: Through employment of identical initial parameters such as (x10, x20, x30, x40, z0) set at (0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1), alongside specific system parameters (α = 0.8, β = 0.01, c = 4.2, d = 4.2, I = 0.2, M = 3), the recipient can effectively reproduce precise five-dimensional chaotic trajectories accompanied by a consistent pseudo-random keystream denoted k(t). 2. Reversal of Diffusion Effect: The composite ciphertext image C undergoes channel segmentation into its constituent color dimensions. Employing XOR operations akin to those executed initially facilitates reversal of diffusion, expressed through p1(t) = C(t) ⊕ k(t). Herein, p1(t) embodies the permuted yet undiffused pixel sequence. 3. Corrective Permutation Application: Restoration of the intrinsic pixel order is realized via implementation of the index inversion regarding the chaotic permutation sequence upon p1(t), represented mathematically as p(t) = p1(index−1(k(t))). Fusion of the processed channels results in the final decrypted imagery.

Security Framework: This cryptosystem’s security draws substantively from vast possibilities within the key space coupled with intricate dynamics evident in memristive Hopfield Neural Networks (HNNs). Constituting the secret key are components such as initial condition vector (x10, x20, x30, x40, z0) and system-specific variables (α, β, c, d, I, k, M, N).

A principal feature observed includes satisfactorily high sensitivity towards baseline conditions like z0, typically numerically quantified around the magnitude of 10−16; this contributes heavily towards securing against brute-force assault methodologies—illustrated through programmable scrolling controlled by respective factors N and M seen significantly affecting said sensitivity. Hyperchaotic systems exhibiting positive Lyapunov exponents consequently validate randomness essential within secure cryptological implementations as evidenced throughout the aforementioned procedural elements considered.

4.2. Analysis of Encryption Performance

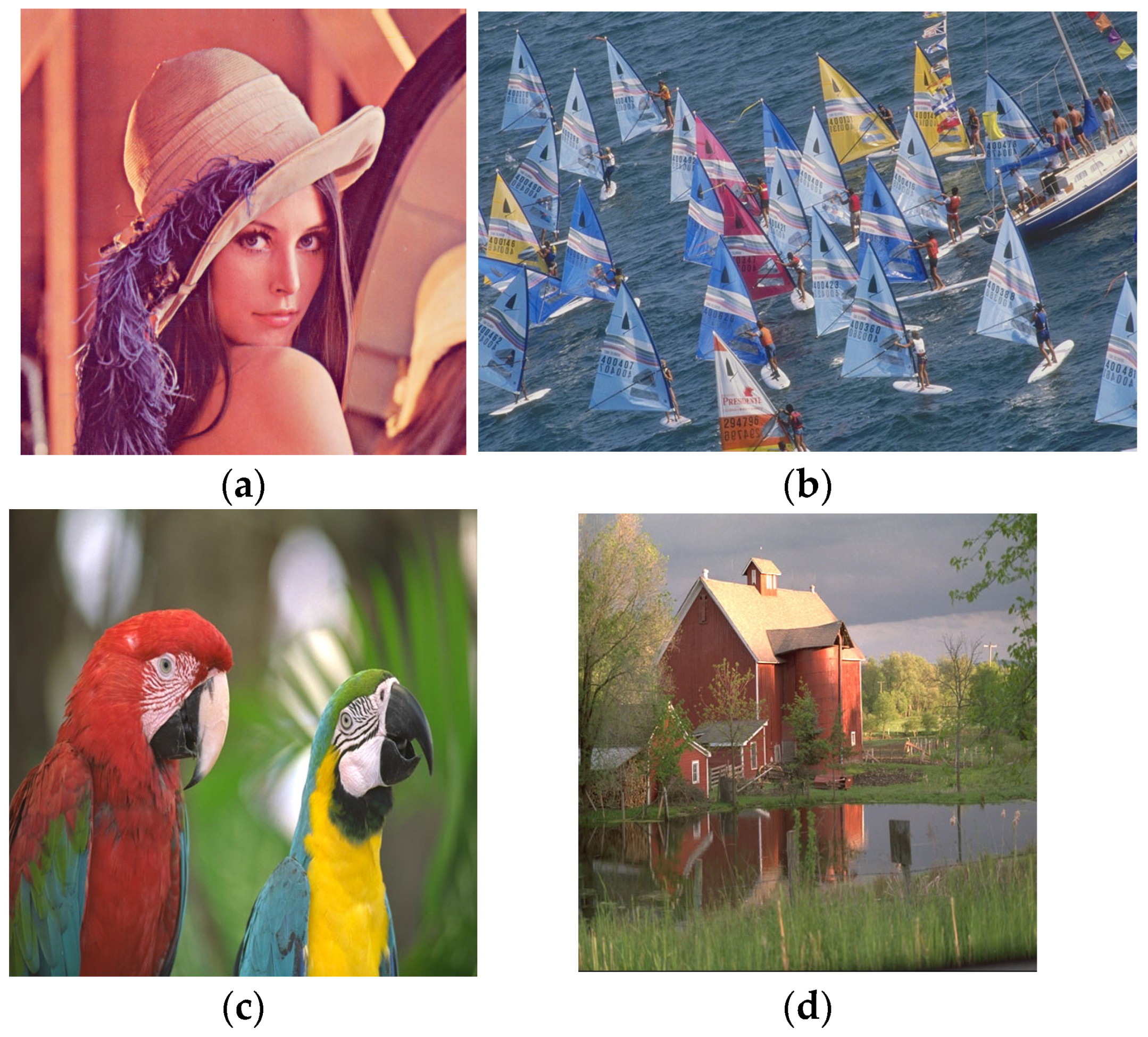

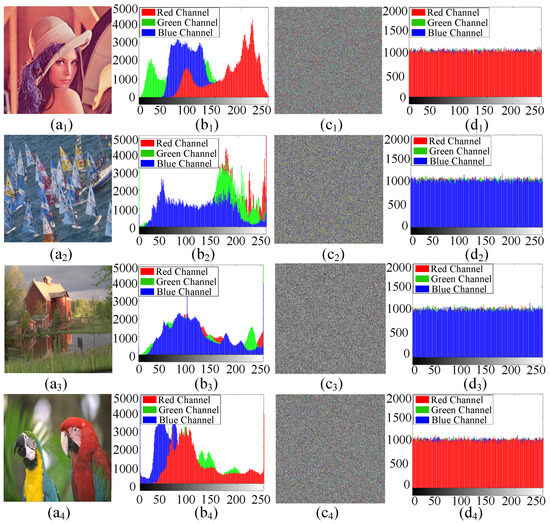

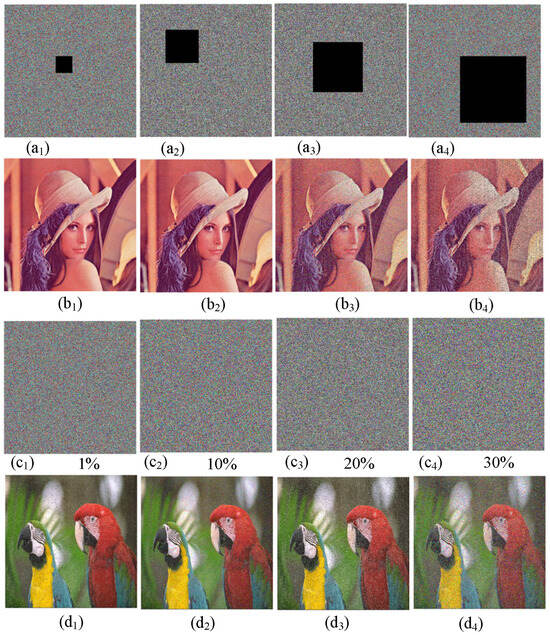

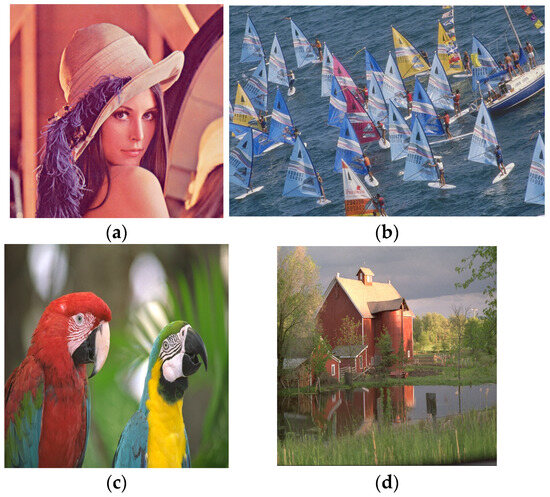

In order to verify the effectiveness of the designed color image encryption cryptosystem, four 512 × 512 color images(Lenna, Sailboat, Red Barn, Macaw) were selected as the encryption objects, namely Figure 14(a1–a4). The experimental results and security performance analysis include histograms, correlation coefficients, information entropy, key sensitivity, data loss and noise attacks.

Figure 14.

Original image, encrypted image and their histograms. (a1) Picture 1. (b1) Corresponding histogram. (c1) Encrypted image. (d1) Corresponding histogram. (a2) Picture 2. (b2) Corresponding histogram. (c2) Encrypted image. (d2) Corresponding histogram. (a3) Picture 3. (b3) Corresponding histogram. (c3) Encrypted image. (d3) Corresponding histogram. (a4) Picture 4. (b4) Corresponding histogram. (c4) Encrypted image. (d4) Corresponding histogram.

The permutation operation enacts a transformative restructuring of the image’s topological space. The construct, delineated as index(k(t)), epitomizes a bijective mapping—a chaotic automorphism—crafted through the procedure of organizing the normalized keystream. From this, its reversibility can be perceived—the inverse mapping index−1(k(t)) exists unequivocally. This entity facilitates an accurate restoration of the initial spatial configuration during decryption by means of reversing the coordinate transformation engaged previously.

4.2.1. Histogram Analysis

The histogram is used to describe the distribution of pixel intensity values in an image. To achieve the best results, a good image encryption system should generate a uniform histogram. Figure 14 shows the original image, the encrypted image, and their histograms. Clearly, the encrypted images in Figure 14(c1–c4) appear very chaotic and completely lose the information of the original images in Figure 14(a1–a4). Figure 14(b1–b4) show the histogram of the original image, which is very distinct in terms of height and position. However, the histogram of the encrypted image in Figure 14(d1–d4) is almost uniform, which means it is very difficult to obtain any useful statistical information from the encrypted image. Therefore, the proposed image encryption scheme is sufficient to resist statistical attacks.

4.2.2. Correlation Analysis

Correlation reflects the relationship between adjacent pixels in an image. Generally, in a regular image, adjacent pixels have strong correlation in all three directions. The correlation coefficient can be calculated using the following formula:

Here, x and y represent the intensity values of adjacent pixels. From the original image and the corresponding encrypted image, 10,000 pairs of pixels were randomly selected in the horizontal, vertical, and diagonal directions to evaluate the correlation coefficient. The correlation coefficients of the original image obtained were 0.9823, 0.98716, and 0.9650, while the average correlation coefficients of the encrypted image were 0.00094, −0.00082, and 0.00037. Undoubtedly, the proposed image encryption scheme can significantly reduce the correlation of the original image. Moreover, as shown in Table 3, the encrypted images processed using the encryption scheme proposed in this chapter have low correlations in the horizontal, vertical, and diagonal directions. Therefore, the designed cryptosystem has a strong ability to resist statistical attacks

Table 3.

Correlation coefficients of different images.

4.2.3. Information Entropy Analysis

Information entropy reflects the randomness of image information. Information entropy can be defined as

In the formula, P(xi) represents the probability of xi occurring, and 2N represents the number of information sources. The maximum theoretical information entropy is eight. Table 4 presents the calculation results of information entropy under different channels. From the results in Table 4, it can be seen that compared with other similar schemes, the information entropy of this scheme is closer to the theoretical value.

Table 4.

Comparison of information entropy of different images.

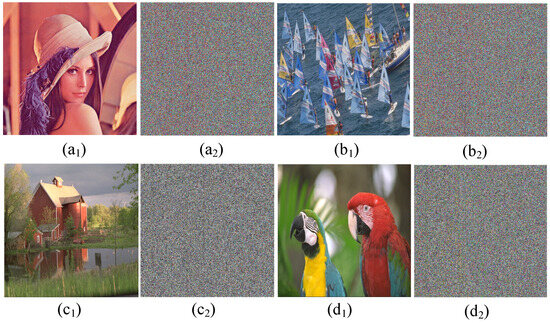

4.2.4. Key Sensitivity Analysis

Key sensitivity is an important indicator for evaluating the security of an encryption algorithm. A good image encryption scheme should be sensitive to the key. The initial value is used as the key in this encryption algorithm. The decrypted image after using the correct key is shown in Figure 15(a1–d1). Changing the key z0 = 0.1 + 10−16, Figure 15(a2–d2) show the incorrect decrypted image. Clearly, although the change in the key is as small as 10−16, the decrypted image is completely different from the original image. As shown in Table 5, compared with other similar image encryption schemes, the image encryption scheme proposed in this paper has a higher sensitivity to the key.

Figure 15.

Key sensitivity test results. (a1) Correct decryption image. (a2) Incorrect decryption image. (b1) Correct decryption image. (b2) Incorrect decryption image. (c1) Correct decryption image. (c2) Incorrect decryption image. (d1) Correct decryption image. (d2) Incorrect decryption image.

Table 5.

Comparison of key sensitivity for different encryption schemes.

4.2.5. Key Space Analysis

The key of the proposed cryptographic system is the five-dimensional initial state vector (x10, x20, x30, x40, z0) defined in the encryption protocol. The size of the key space depends on the computational precision used for these initial values. The key sensitivity analysis presented in Section 4.2.4 has experimentally proven that this system can distinguish the change in z0 at the level of 10−16. The measured sensitivity sets a lower limit for the effective key space, confirming that it is large enough to make brute-force attack infeasible.

4.2.6. Data Loss and Noise Attacks

Image data is highly susceptible to data loss and noise during transmission. A good image encryption scheme should be able to resist data loss and noise attacks. To test the scheme’s ability to resist data loss, the 1/32, 1/16, 1/8, and 1/4 data of the encrypted image were, respectively, extracted, as shown in Figure 16(a1–a4). Then they were decrypted, and the decryption results are shown in Figure 16(b1–b4). Thus, although the encrypted image suffered varying degrees of data loss, the decryption scheme was still able to successfully recover most of the original image data. Additionally, to test the algorithm’s resistance to noise attacks, different concentrations of salt-and-pepper noise signals were added to the encrypted image, as shown in Figure 16(c1–c4). Then they were decrypted, and the decryption results are shown in Figure 16(d1–d4). Although some pixel values in the decrypted image changed, the approximate information of the original image could still be successfully recovered. Therefore, the encryption algorithm proposed in this chapter can resist data loss and noise attacks and has high security.

Figure 16.

Test results of data loss and noise attack. (a1) Image clipping 1/32. (a2) Image clipping 1/16. (a3) Image clipping 1/8. (a4) Image clipping 1/4. (b1) Decrypted image. (b2) Decrypted image. (b3) Decrypted image. (b4) Decrypted image. (c1) One percent salt-and-pepper noise. (c2) Ten percent salt-and-pepper noise. (c3) Twenty percent salt-and-pepper noise. (c4) Thirty percent salt-and-pepper noise. (d1) Decrypted image. (d2) Decrypted image. (d3) Decrypted image. (d4) Decrypted image.

4.2.7. SSIM Analysis

Structural Similarity (SSIM) can be used to evaluate the security of an encryption scheme. It represents the similarity between two different images. For images x and y, SSIM can be expressed as follows:

where ux and uy are the averages of x and y, respectively. σx2 and σy2 are the variances of x and y, respectively. σxy is the covariance of x and y. c1 = (k1L)2 and c2 = (k2L)2 are two constants, where k1 = 0.01 and k2 = 0.03, and L is the dynamic range of pixel values. Table 4 presents the SSIM comparison results of all encrypted images and decrypted images with the original image. As can be seen from Table 6, the SSIM value of the encrypted image in Figure 14(c1) is close to the ideal value of 0, and the ideal SSIM value of the decrypted image in Figure 14(a1) is 1. The test results show that this encryption scheme has a good encryption effect. At the same time, the SSIM value of the incorrect decrypted image in Figure 14(b1) is very low, indicating that this encryption scheme has high key sensitivity. On the contrary, in the cases of noise and data loss attacks, the decrypted images in Figure 16(b1,b2) and Figure 16(d3,d4) show high SSIM values, indicating that when the original image is subjected to data loss and noise attacks, the main information of the image can be well restored.

Table 6.

SSIM values of different images.

4.2.8. NPCR and UACI Assessment

To quantitatively assess the resistance of cryptosystems to differential attacks—in which attackers use slight changes in plain text to extrapolate key information—we used two key indicators: pixel rate of change (NPCR) and uniform mean change force (UACI). Together, these indicators demonstrate the system’s ability to spread and merge, reflecting its ability to propagate global and statistically undetectable local disturbances.

The mean NPCR and UACI values in Figure 17a–d are 0.996093 and 0.334587, respectively. (a) NPCR: 0.996079, UACI: 0.334612; (b) NPCR: 0.996089, UACI: 0.334632; (c) NPCR: 0.996096, UACI: 0.334559; (d) NPCR: 0.996108, UACI: 0.334546. And the base values set for contemporary fractional chaotic systems (e.g., about 99.625% in the literature [25]) and for the hyperchaotic 6D model (99.5956% in the literature [26]) are also exceeded. This near-perfect performance shows that even with minimal changes in the input, the encrypted text is completely restructured, preventing statistical inference attacks.

Figure 17.

Various images used for measuring NPCR and UACI. (a) Picture 1. (b) Picture 2. (c) Picture 3. (d) Picture 4.

UACI is also used to quantify the average strength difference between two passwords, which indicates the nonlinearity and randomness of the divergence. The UACI value obtained by our system is 33.4587%, close to the ideal benchmark of 33.4635%. This result is significantly better than some segmented implementations of HNN (for example, 30.78% in [25]), and also slightly better than the 6D hyperchaotic framework (33.4061% in [26]). The peak convergence enables enriched hnn to harmoniously perform deep and local transformations of pixel values, effectively masking the traces of differences.

The coexistence advantage (rarely recorded in the literature as dual efficiency) proved by NPCR and UACI is due to the inherent hidden multistability of the anti-memory synaptic structure. The essence of super multistability generates a large number of chaotic attractors, each of which can amplify the differences in initial conditions to a completely different set of passwords. This design advantage surpasses traditional methods that rely only on multi-dimensional or fractional infinitesimals, proving that dynamic complexity is a key factor for critical security, rather than a collection of simple parameters.

Essentially, the analysis of NPCR and UACI indicates that our password structure has excellent diffusion characteristics and high sensitivity to input interference. This provides a solid barrier for differential cryptanalysis to meet the requirements for secure video encryption in disaster environments.

4.2.9. Comprehensive Performance Comparison and Analysis

The proposed encryption scheme is thoroughly evaluated against several state-of-the-art methods, including a fractional-order memristive Hopfield neural network [25], a three-dimensional fuzzy-memory associative neural network [27], and a six-dimensional hyperchaotic system [26]. A systematic benchmark is conducted, and the results are summarized in Table 7, which compares the systems across key dimensions: structural design, security robustness, and statistical performance. The comparative analysis demonstrates the competitive performance and superior security of our scheme.

Table 7.

Performance comparison with advanced encryption schemes.

Specifically, our approach exhibits advantages in computational efficiency and key space size under identical operational constraints. As quantified in Table 7, the proposed paradigm shows measurable improvements over prior implementations. This empirical validation confirms its potential for deployment in high-security applications where conventional systems may be inadequate. The results collectively affirm that our scheme advances beyond prevailing standards, achieving a high level of security without sacrificing efficiency.

The experimental results show that the proposed encryption architecture not only possesses strong security but also does not result in excessively high computational complexity. It achieves an excellent balance.

From the 7.9998 information entropy of this system, it can be clearly seen that the statistical security is excellent. This value exceeds those of many similar solutions, indicating that the encrypted text of this system has a high degree of unpredictability. NPCR and UACI proximities to their theoretical ideals are reproduced; adjacent–pixel correlation coefficients, minimized below every rival ledger, can be seen from this to foreclose statistical trace-hunting that feeds on inter-pixel liaison.

Outstanding performance is not solely determined by a higher level. A 6D hyperchaotic cartography [26] is outperformed, along several indices, by the present 4D memristive HNN; the implication drawn is that qualitative dynamic fecundity outweighs the mere count of state variables. Hidden multistability—together with its rarer sibling, super multistability—is deliberately grafted into the vector field’s bones; the attractor soup thereby engendered seeds the keystream with unrepeatable itineracy while sidestepping the computational freight that accompanies loftier phase spaces.

Instances gathered across the benchmark suite converge on one judgment: moderate order, when laced with deliberately seeded dynamic polyvalence, achieves a level of security that would otherwise require systems with higher complexity.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents a novel multi-segment linear memristor model with multi-stable characteristics. The voltage–current properties and multistability of the proposed memristor are systematically investigated. By replacing conventional resistive synapses with this multi-stable memristor, a new variant of the Hopfield neural network (HNN) is constructed, leading to a significant enhancement in its chaotic dynamic complexity. Theoretical analysis and numerical simulations demonstrate that the resulting memristive HNN can exhibit hidden multiple chaotic attractors and super multistability—phenomena rarely observed in previous studies. Leveraging these complex dynamics, a color image encryption scheme is designed. Experimental results confirm that the encryption system exhibits high key sensitivity, strong resistance against exhaustive attacks, and superior information entropy, ensuring high security and robustness. Tests on color image encryption further indicate that the proposed scheme achieves outstanding performance and demonstrates promising potential for practical applications. The discovery of hidden multiple chaotic attractors not only underscores the capability of memristive HNNs in modeling multi-attractor dynamics, but also provides a theoretical foundation for further exploration of the chaotic behavior of multi-attractor networks. This study injects new vitality into interdisciplinary research bridging chaos theory, information security, and image encryption.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.H.; Methodology, Z.H.; Validation, Z.Z.; Investigation, Z.H.; Resources, Z.Z.; Data curation, Z.Z.; Writing—review and editing, Z.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Nomenclature

| Symbol | Description |

| x1, x2, x3, x4, z | State vector of the memristive HNN |

| W(z) | Memductance of the multi-stable memristor |

| f(z) | Nonlinear function governing state dynamics (Equation (3)) |

| N,M | Control parameters for generating multi-scroll attractors |

| k | Coupling strength of the memristive synapse |

| I | External stimulation current |

References

- Lorenz, E.N.E. Deterministic nonperiodic flow. J. Atmos. Sci. 1963, 20, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; Al-Baghdadi, A.F. A 3D-Chaotic Oscillator with Hidden Attractor: Dynamics and Analysis. Int. J. Electr. Eng. Inform. 2022, 14, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ahmadi, A.; Tian, H.; Jafari, S.; Chen, G. Lower-dimensional simple chaotic systems with spectacular features. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2023, 169, 113299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, P.; Huang, Z.; Huang, T. A simple chaotic model with complex chaotic behaviors and its hardware implementation. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2023, 70, 3676–3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Sun, K.; Wang, H.; He, S. A class of novel discrete memristive chaotic map. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2023, 174, 113791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Lin, H.; Deng, X.; Yao, W.; Jin, J. A hidden multiwing memristive neural network and its application in remote sensing data security. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 277, 127168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, H.; Ding, R.; Chen, B.; Xu, Q.; Bao, B. Two-dimensional non-autonomous neuron model with parameter-controlled multi-scroll chaotic attractors. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2023, 169, 113228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, Z.; Peng, Y. A hidden grid multi-scroll chaotic system coined with two multi-stable memristors. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2024, 185, 115109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suykens, J.A.K.; Chua, L.O. n-double scroll hypercubes in 1-D CNNs. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 1997, 7, 1873–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Ding, S.; Lin, H.; Jiang, L.; Sun, H.; Jin, J. Privacy-Preserving Online Medical Image Exchange via Hyperchaotic Memristive Neural Networks and DNA Encoding. Neurocomputing 2025, 653, 131132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Wang, C.; Cui, L.; Sun, Y.; Xu, C.; Yu, F. Brain-like initial-boosted hyperchaos and application in biomedical image encryption. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 8839–8850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Mou, J.; Qin, L.; Jahanshahi, H. A memristor-coupled heterogeneous discrete neural networks with infinite multi-structure hyperchaotic attractors. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2023, 138, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Jiang, L.; Hu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, Q. Hidden coexisting firings in fractional-order hyperchaotic memristor-coupled HR neural network with two heterogeneous neurons and its applications. Chaos Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 2021, 31, 083107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Q.; Yang, L. Discrete memristor applied to construct neural networks with homogeneous and heterogeneous coexisting attractors. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2023, 174, 113807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignesh, D.; Ma, J.; Banerjee, S. Multi-scroll and coexisting attractors in a Hopfield neural network under electromagnetic induction and external stimuli. Neurocomputing 2024, 564, 126961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Wang, C.; Yao, W.; Tan, Y. Chaotic dynamics in a neural network with different types of external stimuli. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2020, 90, 105390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zheng, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; He, S. Initial offset boosting coexisting attractors in memristive multi-double-scroll Hopfield neural network. Nonlinear Dyn. 2020, 102, 2821–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Q.; Wan, Z.; Kuate, P.D. Generating grid multi-scroll attractors in memristive neural networks. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2022, 70, 1324–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Q.; Wan, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, G. Design and analysis of multiscroll memristive Hopfield neural network with adjustable memductance and application to image encryption. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 34, 7824–7837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Shen, H.; Yu, Q.; Kong, X.; Sharma, P.K.; Cai, S. Privacy protection of medical data based on multi-scroll memristive Hopfield neural network. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 845–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Peng, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, C.; Zeng, Z. A novel memristive multiscroll multistable neural network with application to secure medical image communication. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 35, 1774–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Dong, E.; Tong, J.; Wang, Z. A novel multiscroll memristive Hopfield neural network. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2022, 32, 2250130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Wang, X.; Gao, H. Chaotic image encryption algorithm based on bit-level feedback adjustment. Inf. Sci. 2024, 679, 121088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, J.; Pchelintsev, A.N.; Karthikeyan, A.; Parastesh, F.; Jafari, S. A fractional-order memristive two-neuron-based Hopfield neuron network: Dynamical analysis and application for image encryption. Mathematics 2023, 11, 4470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Liu, L.; Jin, J.; Lin, H. A fractional-order memristive Hopfield neural network and its application in medical image encryption. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, N.V.; Leonov, G.A.; Vagaitsev, V.I. Analytical-numerical method for attractor localization of generalized Chua’s system. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2010, 43, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, A.; Biban, G.; Chugh, R.; Tassaddiq, A.; Alharbi, R. An efficient image encryption model based on 6D hyperchaotic system and symmetric matrix for color and gray images. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).