Abstract

Drug–target interaction (DTI) predictions, which aim to predict whether a drug will be bounded to a target, have received wide attention recently. The goal is to automate and accelerate the costly process of drug design. Most of the recently proposed methods use single drug–drug similarity and target–target similarity information for DTI predictions; thus, they are unable to take advantage of the abundant information regarding the various types of similarities between these two types of information. Very recently, some methods have been proposed to leverage multi-similarity information; however, they still lack the ability to take into consideration the rich topological information of all sorts of knowledge bases in which the drugs and targets reside. Furthermore, the high computational cost of these approaches limits their scalability to large-scale networks. To address these challenges, we propose a novel approach named summated meta-path-based probabilistic soft logic (SMPSL). Unlike the original PSL framework, which often overlooks the quantitative path frequency, SMPSL explicitly captures crucial meta-path count information. By integrating summated meta-path counts into the PSL framework, our method not only significantly reduces the computational overhead, but also effectively models the heterogeneity of the network for robust DTI predictions. We evaluated SMPSL against five robust baselines on three public datasets. The experimental results demonstrate that our approach outperformed all of the baselines in terms of the AUPR and AUC scores.

Keywords:

drug–target interaction predictions; data mining; meta-path; probabilistic soft logic; convex optimization MSC:

37M10

1. Introduction

New drug development is usually a very time-consuming and expensive procedure. Recently, computer-aided drug design has received wide attention, with the goal of accelerating drug design. Among this attention, the study of predicting unknown drug–target interactions based on existing domain-specific knowledge using mathematical models has become an area of growing interest [1]. By quantitatively expressing the similarity between drug–drug and target–target information, one can find a mathematical relationship between drugs and targets, which could help to predict potential interactions between existing drugs and unknown targets, or vice versa [2].

There are several existing methods used to model the drug–target interaction prediction [3] task, most of which apply a network-based representation [4]. Fakhraei et al. [5] constructed a bipartite interaction network with two types of nodes: drug nodes and target nodes. There can be edges between two drug nodes or two target nodes, denoting similarity information. The edges between the drug nodes and target nodes represent interaction information. However, such a bipartite interaction network constrains the type of nodes within the two, and additional measures are unable to be added.

In addition to a bipartite interaction network, ref. [1] constructed a heterogeneous internet that can directly integrate richer domain-specific knowledge into the network, such as drug–drug/target–target interaction information, drug–cure–disease and disease-caused-by-target information, etc. Instead of transferring this information into similarities using standard measures (such as the Jaccard and Spearman indices), the DTI prediction task can be solved using the information directly extracted out of the heterogeneous network.

Link prediction methods can predict potential interactions within a network, and their use has been proposed by both Getoor and Diehl [6] and Lü and Zhou [7]. However, some link prediction methods ignore the inner relationship among different semantic similarity information [8] and other domain-specific knowledge, while some methods tend to take all the details into consideration to achieve good results. However, the time consumption becomes very heavy [5,9,10].

In this paper, we present a drug–target interaction prediction method based on probabilistic soft logic (PSL) [11]. We predicted unknown drug–target interactions using multi-relational information and the existing interactions of the network. In order to avoid grounding out all the rule instances that could significantly slow down the inference process, like with the original PSL model, we applied a summated meta-path [8], which defined several semantic meta-paths and used matrix multiplications to calculate the path counts, storing this information as commuting matrices. We applied a Bayesian probabilistic approach that transferred the path counts into probabilities, indicating probabilities for the body parts of PSL rules [12], and then applied the PSL model for the DTI prediction. Our summated meta-path PSL model outperformed all five baselines [5,8,9,10] in terms of both the AUPR score and the AUC score on three open-source datasets, together with significant time-consumption reductions.

We defined several semantic meta-paths and used matrix multiplications to generate commuting matrices corresponding to each semantic meta-path, which is similar to the method used by Fu et al. [8]. Afterwards, we applied a Bayesian probabilistic approach that transferred the path counts of the commuting matrices into probabilities. Then, we defined several PSL rules. The first PSL rule is “Each semantic meta-path metric may imply potential interactions”; the second PSL rule is “By default, the drug and target do not interact with each other”. The first rule corresponds with the pre-defined semantic meta-paths, and the second rule is a negative prior. Differently from the original PSL model, for each drug–target pair, we only had one rule instance within each PSL rule, since we applied summation using the meta-path counts on all the existing rule instances. For each drug–target pair, we treated the probabilities based on different semantic meta-paths as the body part of the PSL rule instances. For more details about the probabilistic soft logic (PSL), please refer to [12,13].

Our primary contribution lies in identifying and bridging the specific limitations inherent in both meta-path-based methods and standard probabilistic soft logic (PSL). While meta-path approaches generate robust topological features (path counts), they typically treat these counts merely as feature vectors, lacking a rigorous probabilistic interpretation. Conversely, while PSL provides a strong probabilistic reasoning framework, it suffers from high computational overhead because it grounds every single rule instance individually, often overlooking the collective information embedded in the summation of these instances.

Our proposed solution creates a synergy between these two approaches: by integrating PSL, we provide a probabilistic semantic meaning to the meta-path topological features. Simultaneously, by adopting a path count summation strategy, we allow PSL to focus on aggregated rule instances (meta-path counts) rather than individual instances. This significantly reduces the total number of ground rules, enabling the application of PSL to much larger datasets without sacrificing accuracy.

Based on the new settings, we implemented a new DTI prediction framework, i.e., summated meta-path-based probabilistic soft logic (SMPSL), and compared our model to five other multi-similarity or internet-based approaches [5,8,9,10] on three open-source datasets used in [5,8,10] (Fu et al. [8] proposed two methods). The experimental results indicate that our model significantly reduced the running time and outperformed all five baseline models on all three datasets in terms of the AUC score and AUPR score.

2. Related Work

There are a number of network-structure-based methods for drug–target interaction predictions. Cockell et al. [14] constructed a network structure metagraph to organize drugs, targets, proteins, and genes, showing their relationships. They pointed out that drugs with similar structures can behave similarly in their interactions. Based on a network structure, Cheng et al. [15] treated the DTI prediction problem as an inference problem on a drug–target bipartite network that integrated chemical drug–drug similarities, sequential target–target similarities, and known drug–target interactions.

Yamanishi et al. [16] integrated compound structure similarities, protein sequence similarities, and several open-source drug–target interaction datasets in a network, generating gold-standard datasets that characterize the drug–target interaction network into four classes: enzymes, ion channels, GPCRs, and nuclear receptors. A number of more recent matrix factorization drug–target interaction prediction methods [17,18] have given promising results on the gold-standard dataset generated by Yamanishi et al. [16].

In order to take multiple similarities and additional domain-specific measures into consideration, Luo et al. [10] used a dimensionality reduction scheme and a diffusion component analysis (DCA) to obtain informative feature representations based on relational properties, association information, and the topological context of each drug and target within a heterogeneous network. After generating the feature representations, they used a learned projection matrix that best projects the drug features into the protein space so that the distance between the projected feature vectors from the drug space to the target space and the interacting proteins is minimized.

Chen et al. [19] used advanced topological features, such as the distance and number of shortest paths between node pairs, for drug–target predictions. Furthermore, Fu et al. [8] used semantic meta-path topological features and applied an SVM and a random forest algorithm as a classifier on a network integrated with multiple objects, including compounds, proteins, diseases, genes, etc.

Cichonska et al. [9] used a kernel-based approach that first learns a corresponding weight for each similarity measure, and then calculates a corresponding weight for each pairwise kernel. By detecting high-ranking values within the weighted summed kernel matrix for the unknown drug–target pairs, they could be considered new interactions. The dataset provided by this paper is a dataset on drug bioactivity predictions for cancer cells; the labels are numerical bioactivity measures. As a result, it is not suitable for use as a comparison dataset for DTI predictions.

Instead of using topological features, Perlman et al. [20] combined multiple sources of drug–drug similarity and target–target similarity data together into features, using logistic regression as the classifier. Fakhraei et al. [5] extracted a subset of drugs and targets from the dataset created by Perlman et al. [20], formulating the DTI prediction as an inference problem on a network and using a probabilistic soft logic (PSL) framework for inference.

There are also non-similarity-based approaches that take pre-calculated drug and target features out of raw descriptors as the input of their models [21,22]. Furthermore, Wen et al. [23] used deep learning-based approaches for DTI predictions; their model takes the raw drug and target descriptors as the input and trains using the interactions of all FDA-approved drugs and targets. Since the input of the datasets provided by these approaches comprises descriptors, the datasets were not suitable for comparison experiments using our multi-similarity and internet-based approaches.

It is worth noting that the landscape of DTI predictions has been significantly impacted by deep learning techniques, which leverage neural architectures to approximate complex interaction functions [24,25,26]. While effective in performance, these methods often obscure the underlying biological rationale, offering prediction without explanation. In contrast, probabilistic graphical models and meta-path-based approaches operate within the paradigm of interpretable reasoning, where transparency and logical grounding are paramount. As the primary objective of this study was to resolve the specific algorithmic and semantic bottlenecks existing within the interpretable reasoning framework—specifically bridging probabilistic soft logic (PSL) with meta-path-based information—we restricted our comparative analysis to methods within this topological and probabilistic domain.

3. Preliminaries

3.1. Meta-Path Count Topological Feature

A semantic meta-path defines a certain type of paths linking the starting and ending objects. The total number of path instances of one semantic meta-path can be treated as a topological feature that evaluates the strength of associations between the starting and ending objects, also called the path count [8]. In the DTI prediction task, a meta-path starts from a drug and ends with a target, meaning that there is one valid meta-path instance between the drug and target. For instance, we can define two types of semantic meta-paths:

Meta-path (A) indicates that, if a drug interacts with a target and has a similarity to another drug, then the other drug is also likely to interact with this target. Meta-path (B) has a similar interpretation.

For each drug–target interaction pair, we first calculated the corresponding path counts within the dataset under each semantic meta-path, and then concatenated the numbers into a topological feature vector, with each dimension denoting the corresponding path count value.

3.2. Hinge-Loss Markov Random Fields and Probabilistic Soft Logic

Probabilistic soft logic (PSL) uses first-order logic syntax to form a hinge-loss Markov random field (HL-MRF) model. A hinge-loss Markov random field model is defined over continuous variables and can naturally assemble probabilities and other real-valued attributes. By applying a maximum a posteriori (MAP) inference on a hinge-loss Markov random field, we can efficiently obtain an exact inference result for all the variables, as the MAP inference on an HL-MRF model is a convex optimization problem [13]. A hinge-loss Markov random field can be formulated as a log-concave joint probability density function:

Y is the set of unknown variables and X is the set of observed values. represents the set of weight parameters and Z is a normalization constant. The potential function for HL-MRFs is defined as follows:

is a linear function of Y and X and . The MPE inference is also equivalent to minimizing the convex energy. In the PSL setting, all the grounded-out rule instances that are associated with both known values, such as similarity information, and unknown variables, such as potential drug–target interactions, are treated as terms in the potential function of an HL-MRF model. In more detail, we considered a general form of the following PSL rule:

R (A, C) represents a continuous target variable, such as the probability of interactions between drug A and target C; P (A, B) and Q (B, C) represent observed values, such as the similarity between drug A and drug B or the probability of interaction between drug B and target C. The soft logic defines a relaxed convex representation of this logical implication:

This continuous value can be treated as the distance to satisfaction of the logical implication. The MAP inference algorithm aims to minimize the energy of a hinge-loss Markov random field, which is equivalent to minimizing the total weighted distance to satisfaction for all the grounded-out rule instances. A full description of PSL is provided by [12].

4. Problem Definition

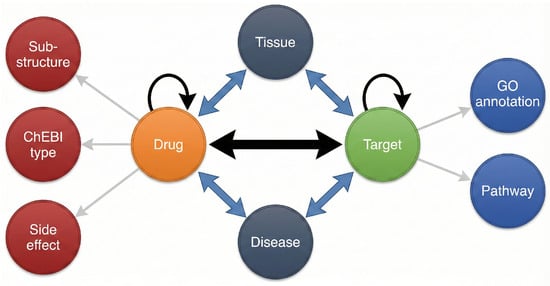

We considered the problem of drug–target interactions by inferring new edges between drug nodes and target nodes on a heterogeneous network. Given a set of drugs D = {} and a set of targets T = {}, the total potential interactions between the drugs and targets can be denoted as an interaction matrix , where represents a positive interaction between drug and target . In addition, a set of domain-specific measures are represented as edges between nodes in the network. For example, multiple drug–drug similarities {} can be treated as edges between drug nodes. Figure 1 shows a heterogeneous network based on the dataset provided by Fu et al. [8].

Figure 1.

A visual demonstration of the DTI heterogeneous information network.

The drug–target interaction prediction problem involves making use of all the information within the heterogeneous network to predict the unobserved interaction edges between drug nodes and target nodes.

5. Summated Meta-Path-Based Probabilistic Soft Logic (SMPSL)

In this section, we introduce our summated meta-path-based probabilistic soft logic (SMPSL) model.

5.1. Overview

The primary objective of our proposed method was to address the inherent computational bottleneck of traditional probabilistic soft logic (PSL) when applied to large-scale heterogeneous networks. While PSL provides a robust reasoning framework, its standard grounding process—instantiating a rule for every possible path instance—suffers from severe scalability issues. Consider a drug–target interaction (DTI) network comprising a set of drugs (where ) and a set of targets (where ). In comprehensive analyses, we often utilize complex meta-paths to infer relationships, such as the symmetric path . The number of potential rule instances (groundings) generated for such a path is the product of the cardinalities of the entities involved. For a fully connected scenario, the total number of groundings can be expressed as follows:

In a large-scale biological network where m and n are in the thousands, easily reaches the billions, rendering standard PSL inference computationally intractable.

The existing methods to mitigate this explosion, such as the blocking strategy proposed by Fakhraei et al. [5], rely on filtering the network to retain only the top-k nearest neighbors for similarity measures. While this reduces the effective size of the neighbor sets, the resulting number of groundings often remains prohibitively large. Furthermore, blocking techniques operate on the assumption of continuous similarity metrics (e.g., cosine or Jaccard similarity). They are fundamentally unachievable or ill-defined for binary association measures (e.g., “Drug A has Side Effect B” is a 0/1 relationship), where no granular distance metrics exist to facilitate top-k pruning.

To resolve these challenges, we proposed the summated meta-path-based probabilistic soft logic (SMPSL) approach. Instead of grounding rules for individual path instances, SMPSL aggregates these instances into a single, comprehensive feature: the meta-path count. Crucially, this summation strategy serves a dual purpose. First, it drastically reduces the computational overhead by compressing the rule space from combinatorial complexity to linear complexity regarding the node pairs. Second, and perhaps more importantly, the summation captures the cumulative signal of a specific semantic meta-path. Rather than treating each path as isolated, weak probabilistic evidence, SMPSL interprets the total count as a robust measure of topological strength, allowing the model to weigh the significance of the entire meta-path pattern (e.g., “shared mechanism of action”) rather than becoming lost in the noise of individual connections.

5.2. Summation of Logical Rule Instances

To overcome the computational bottleneck of standard grounding, we drew inspiration from topological feature extraction in heterogeneous information networks. Fu et al. [8] demonstrated that the semantic strength of a relation between two entities can be quantified by the meta-path count, which represents the number of path instances connecting them following a specific schema.

Mathematically, for a meta-path P consisting of a sequence of relations , the number of path instances between all entity pairs can be efficiently computed via matrix multiplication. Let denote the adjacency matrix for relation . The commuting matrix , which encodes the path counts, is defined as follows:

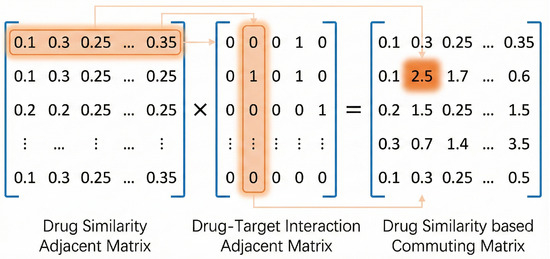

For example, consider the drug–drug similarity rule illustrated in Figure 2: . The corresponding commuting matrix is calculated as . An entry in this resulting matrix signifies the total number of distinct paths connecting Drug i to Target j via chemically similar intermediate drugs.

Figure 2.

Matrix multiplications were used to generate a commuting matrix. Instead of using a binary value for the similarity measure, we used exact similarities and generated a relaxed rule instance count.

Standard PSL implementations treat each of these path instances as a separate logical rule instance. For a single pair , standard PSL would generate distinct ground rules, each requiring an independent calculation of the distance to satisfaction (convex energy). Our novel contribution lies in transforming this granular grounding process into an aggregate formulation. Instead of grounding k separate rules for a drug–target pair, we treated the summated meta-path count as a single, aggregate evidential feature. We redefined the PSL potential function to accept this scalar count directly. Consequently, for any given pair , the set of all path instances w.r.t. the same semantic meta-path was compressed into a single ground rule. This reduced the number of potentials in the graphical model from the total number of paths to the total number of pairs, effectively leveraging the efficiency of matrix operations to accelerate the probabilistic reasoning process.

5.3. Generalized Relaxed Counts and Semantic Expansion

While traditional meta-path counts are often discrete integers derived from binary connections, the “soft” nature of probabilistic soft logic allows us to utilize richer, continuous information. Binary thresholding inevitably leads to information loss, losing the distinction between strong (0.95) and weak (0.55) similarities.

To preserve this nuance, we introduced the concept of relaxed rule instance counts. Instead of using binary adjacency matrices, we employed continuous similarity matrices, where entries represent exact similarity scores (e.g., Jaccard coefficients). The resulting commuting matrix entries are no longer simple integer counts, but weighted “evidence scores” that reflect the cumulative strength of the path connections.

Mathematically, the relaxed commuting matrix for a chemical-similarity-based rule can be formalized as follows:

where is the continuous adjacency matrix representing the chemical similarity between drugs and is the binary drug–target interaction matrix. The entry thus represents the sum of the interaction probabilities, weighted by the chemical similarities of intermediate drugs.

The power of our SMPSL framework extends beyond simple similarity-based propagation. The matrix multiplication formulation allows us to seamlessly integrate complex semantic meta-paths that traverse diverse entity types within the heterogeneous information network (HIN). Consider a path that incorporates disease etiology information: . This path captures a logical deduction: if a drug treats a disease, and a specific target causes that disease, there is a latent probability of interaction between the drug and the target. We formalized this semantic inference by computing the corresponding commuting matrix as follows:

Here, represents the drug–disease association matrix and represents the disease–target association matrix.

This formulation provides a universal interface for heterogeneous data integration. By standardizing diverse biological relationships (similarities, associations, and causal links) into matrix representations, our approach can aggregate any information source that can be abstracted as a semantic meta-path. Whether adding side-effect profiles, gene ontology annotations, or pathway data, each new information source simply becomes an additional commuting matrix that is fed into the SMPSL framework as a new aggregate potential, significantly enhancing the model’s predictive coverage without altering its fundamental architecture.

5.4. Bayesian Probabilistic Mapping

While the raw values within a commuting matrix effectively quantify the topological strength of connections, they are unbounded scalars (e.g., ) that do not natively fit within the soft truth domain required by probabilistic soft logic (PSL). To bridge this gap, we employed a data-driven Bayesian framework to map these raw topological scores into calibrated posterior probabilities.

Formally, let denote the raw value in the commuting matrix for a specific drug–target pair , and let be the binary variable representing the true interaction status. We sought to compute the posterior probability , which represents the confidence that an interaction exists given a specific meta-path count v.

By applying Bayes’ Theorem, this posterior is defined as follows:

By expanding the denominator using the law of total probability, we obtain the following:

Here, the terms are estimated empirically from the training data as follows:

Class Prior : This represents the baseline probability of any random pair being positive () or negative () within the network. It is calculated as the ratio of known interactions to the total number of labeled pairs in the training set :

Likelihood : This term represents the conditional probability of observing a specific meta-path count v given the class label k. We estimated this utilizing discrete frequency distributions (histograms) over the training data:

where is the number of training pairs with the label k that possess the specific commuting value v, and is the total count of training pairs with the label k. By applying Equation (12), we transformed the potentially unbounded commuting matrix into a probabilistic matrix , where every entry serves as a grounded soft-truth predicate for the PSL inference engine.

5.5. Global Objective and Inference

Negative Prior and Sparse Regularization: In biological networks, valid interactions are sparse; the vast majority of random drug–target pairs do not interact. To encode this domain knowledge, we introduced a negative prior rule:

Hinge-Loss Objective Function: We formulated the joint probability distribution over the unknown interactions as a hinge-loss Markov random field (HL-MRF). Our goal was to find the optimal assignment of soft-truth values that minimizes the total energy (or “distance to satisfaction”) of the system. Let be the set of all unobserved drug–target pairs. For each pair , let be the predicted interaction probability. Let K be the number of semantic meta-path rules, where denotes the probabilistic evidence derived from the k-th meta-path for pair r (as calculated in Equation (12)). Formally,

Here, the first term represents the cost of violating the negative prior (sparsity), and the second term represents the cost of violating the meta-path evidence (consistency). The parameter controls the loss function (linear or squared); in our experiments, we set for a strictly convex optimization landscape.

Computational Complexity Analysis: The structural advantage of SMPSL is evident in this formulation. In the original PSL framework, the summation would be over all path instances, resulting in groundings. In contrast, our objective function sums only over target pairs (), where, for each pair, the billions of path instances are pre-compressed into K evidence scores. This collapses the grounding complexity from combinatorial to linear with respect to the number of edges, enabling inference on large-scale networks that were previously intractable.

Weight Learning: Since not all semantic meta-paths contribute equally to the prediction (e.g., the chemical similarity might be more predictive than the side-effect overlap), we must learn the optimal weights . We employed a maximum-likelihood estimation approach using stochastic gradient descent (SGD) on a validation set of observed links. The gradient of the log-likelihood with respect to a specific weight is given by the difference between the observed truth and the model’s expectation:

where is the distance to satisfaction for the k-th rule.

6. Experimental Results

6.1. Datasets

We used three datasets for our experiments. One was the dataset constructed and used by Fakhraei et al. [5] and Perlman et al. [20], and was a multi-similarity-based dataset; another was used by Fu et al. [8]; and the third was used by Luo et al. [10]. Both of the latter incorporated additional domain-specific knowledge and formed a heterogeneous network.

6.1.1. Dataset I

This dataset contains 315 drugs, 250 targets, and 1306 known interactions. In addition, there are five drug–drug similarities and three target–target similarities within the dataset, obtained from Perlman et al. [20]. The five drug–drug similarity measures are chemical-based, ligand-based, expression-based, side-effect-based, and annotation-based. The three target–target similarity measures are sequence-based, protein–protein-interaction-network-based, and Gene Ontology-based. The drug–target interactions of this dataset were obtained from several open-source online databases organized by Fakhraei et al. [5], including the DrugBank [27], KEGG Drug [28], the Drug Combination database [29], and Matador [30]. A brief description of each similarity extraction is provided below:

- Chemical-based drug similarity: Perlman et al. [20] used a chemical development kit [31] to compute a hashed fingerprint for each drug based on the specification information obtained from the Drugbank. They computed the Jaccard similarity of the fingerprints. A Jaccard similarity score between two sets X and Y is defined as follows:

- Ligand-based drug similarity: Perlman et al. [20] compared the specification information from the Drugbank against a collection of ligand sets using the similarity ensemble approach (SEA) search tool [32]. The ligand sets denote the Jaccard similarity between the corresponding sets of protein–receptor families for each drug pair.

- Expression-based drug similarity: Perlman et al. [20] used the Spearman rank correlation coefficient to compute the similarity of gene expression responses to drugs, which was obtained from the Connectivity Map Project [33,34]. The Spearman rank correlation coefficient between two sets X and Y is calculated as follows:

- Side-effect-based drug similarity: The Jaccard similarity of side-effect sets for each drug pairs was calculated. The side-effect sets were obtained from Günther et al. [30].

- Annotation-based drug similarity: Perlman et al. [20] used the semantic similarity algorithm of Resnik [35] to calculate the similarity of the ATC code, which was obtained from the DrugBank and matched against the World Health Organization’s ATC classification system [36] for each drug pair.

- Sequence-based target similarity: Perlman et al. [20] used the sequence-based similarity score as a target similarity measure, which was suggested by Bleakley and Yamanishi [37].

- Protein–protein-interaction-network-based target similarity: The distance between target pairs was computed as a similarity measure using an all-pairs shortest-path algorithm on the human protein–protein interaction network.

- Gene Ontology-based target similarity: The semantic similarity was computed between Gene Ontology annotations from the source of Jain et al. [38] using Resnik’s method [35].

We followed the same procedure as Fakhraei et al. [5], who used ten-folder validation for the experiments. Each folder had positive links and negative links for training, and another comprising links used for testing. The pre-defined rules for this multi-similarity dataset are shown in Table 1:

Table 1.

Summary of meta-paths for drug–target interactions.

6.1.2. Dataset II

This dataset, adopted from Fu et al. [8], represents a complex heterogeneous information network (HIN) specifically designed to capture diverse biological semantics. Unlike Dataset I, which focuses on multi-view similarity, Dataset II emphasizes the topological structure of bio-entity associations. The network explicitly models 9 node types and 12 edge types (including similarity relations), as shown in Figure 1.

- Node Types: Drugs (compounds), targets (proteins), adverse side effects, Gene Ontology (GO) annotations, ChEBI types, substructures, tissues, biological pathways, and diseases.

- Edge Types: The network includes canonical interactions, such as drug–target and target–target interactions, as well as semantic associations like drug–disease, tissue–target, and pathway–protein links. Additionally, it incorporates the 2D structural drug–drug similarities and sequence-based target–target similarities derived from PubChem [39,40].

The scale of this network is substantial, comprising a total of 295,897 nodes (including 258,030 drugs and 22,056 targets) and 7,191,240 edges. Notably, the complexity of the topology results in a massive combinatorial space, generating approximately 6.5 billion () meta-path instances.

Following the protocol established by Fu et al. [8], we adopted a time-split validation strategy to simulate a realistic discovery scenario.

- Training Set: The training set consisted of 145,622 positive DTI links and 600,000 negative links that were explicitly observed within the network construction period.

- Testing Set: The testing set consisted of 43,159 positive links and 195,000 negative links that were historically subsequent or previously unobserved, ensuring that the model was evaluated on its ability to generalize to novel interactions.

We utilized the 51 semantic meta-paths defined by Fu et al. [8] to capture the rich topology of this network. These paths ranged from simple connectivity (e.g., length-2 paths) to complex biological inferences (e.g., shared pathway mechanisms). The complete definition of all 51 meta-paths is provided in Table A1.

6.1.3. Dataset III

To evaluate our model on a dense network with a high connectivity, we utilized the dataset constructed by Luo et al. [10] (commonly referred to as the DTINet dataset). This network integrates diverse drug-related information into a unified heterogeneous graph structure. The network is composed of four distinct node types and six interaction types, comprising a total of 12,015 nodes and 1,895,445 edges, as described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Statistics of the heterogeneous information network dataset.

Data Provenance: The network data were aggregated from high-confidence public repositories: drug–target and drug–drug interactions were sourced from the DrugBank [27]; protein–protein interactions were derived from the Human Protein Reference Database (HPRD) [41]; drug–disease and protein–disease associations were extracted from the Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD) [42]; and drug–side effect associations were obtained from SIDER [43].

Experimental Protocol: Consistent with the validation strategy in Luo et al. [10], we employed a 10-fold cross-validation scheme. We randomly partitioned the known drug–target interactions into a training set () and a testing set (), sampling an equal number of non-interacting pairs for each set to maintain class balance.

Meta-Path Mapping: While Dataset II and Dataset III share similar entity types, Dataset III represents a specific topological subspace. To adapt our SMPSL framework to this structure, we performed a schema mapping procedure. We projected the 51 universal meta-paths defined for the HIN of Dataset II onto the specific entity-relation schema of Dataset III. This resulted in a set of 21 valid semantic meta-paths that are topologically consistent with the available edge types (e.g., paths involving “tissue” or “ChEBI” were excluded, as those nodes were absent). The selected meta-path IDs, as defined in Table A1, were C1, C2, C3, C4, C5, C6, C7, C11, C15, C16, C17, C18, C19, C24, C25, C26, C27, C44, C45, C46, and C47.

6.2. Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively assess the performance of our model, we utilized two standard metrics: the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC-ROC) and the area under the precision–recall curve (AUPR).

The ROC curve visualizes the trade-off between the true positive rate (TPR) and the false positive rate (FPR) at various threshold settings. These metrics are defined as follows:

where , , , and denote the number of true positives, false negatives, false positives, and true negatives, respectively. The AUC score represents the probability that a classifier will rank a randomly chosen positive instance higher than a randomly chosen negative one.

While the AUC is widely used for comparison with the existing literature, it can be overly optimistic when applied to highly imbalanced datasets (where the negatives vastly outnumber the positives). This is because the FPR calculation involves true negatives () in its denominator; a large number of negatives suppresses the FPR, inflating the AUC score even if the model yields many false positives.

Therefore, we adopted the AUPR as a more robust primary metric. The PR curve plots the precision against the recall (which is equivalent to the TPR):

Unlike the AUC, the precision does not rely on true negatives. Consequently, the AUPR penalizes false positives more heavily, making it a more informative metric for identifying sparse positive interactions in imbalanced biological networks.

6.3. Baselines

We compared our model with five approaches: the original PSL method [5], the meta-path count feature + random forests and support vector machine methods [8], the pairwise MKL method [9], and the DTINet method [10]. All five baselines can predict drug–target interactions on a heterogeneous network.

Baseline Approaches

Fakhraei et al. [5] introduced the probabilistic soft logic model, which pre-defines a series of association rules, treated as “rules”, and solves the DTI prediction problem as inference on a bipartite graph. More specifically, it introduces eight different similarity-based association rules for the DTI prediction task (shown in Section 6.1.1) After defining the rules, Fakhraei et al. [5] incorporated all the rule instances within a bipartite graph, and minimized the total distance to satisfaction based on all the rule instances to make predictions.

Fu et al. [8] introduced the meta-path topological feature, which also defines a series of association rules, but on a heterogeneous network, denoted as a “meta-path”, and then uses matrix multiplications to calculate a meta-path count. For the DTI prediction task, they defined 51 different meta-paths (introduced in Section 6.1.2) and for each drug–target pair, they formed a 51-dimensional vector based on the meta-path-count topological features, and then used machine learning classifiers, a support vector machine, and random forests to solve the DTI prediction problem as a supervised learning task.

Moreover, Luo et al. [10] introduced a method that can generate a low-dimensional representation for both the drug and target, based on a series of association matrices. For each drug, they had four association matrices, and for each target, they had three association matrices. They applied a diffusion component analysis (DCA) to obtain informative low-dimensional feature representations, and then used a learned projection matrix that can project the drug feature into the protein space so that the distance between the projected vectors and the interacted targets is minimized.

We also compared our model to a kernel-based approach [9] that learns a set of weights for each single kernel as well as for each combination of kernel pairs.

6.4. Results

In this section, we present a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed summated meta-path PSL (SMPSL) model. We compared SMPSL against the aforementioned baselines in terms of their prediction effectiveness and computational efficiency across the three datasets introduced in Section 6.1. Furthermore, we conducted an ablation study to analyze the impact of the weight-learning module and provide a detailed case study on meta-path selection.

6.4.1. Effectiveness Comparison

Table 3 summarizes the experimental results comparing our proposed SMPSL model against the aforementioned baselines across all three datasets. We evaluated the performance using the area under the ROC curve (AUC) and the area under the precision–recall curve (AUPR).

Table 3.

Effectiveness comparison (AUC and AUPR) between SMPSL and baseline approaches. Note: Entries marked with ‘*’ indicate results obtained from a downsampled subset (1%) due to computational constraints.

Analysis of Dataset I: On the smaller-scale Dataset I, the original PSL approach demonstrated a strong performance, outperforming the meta-path + SVM/RFs, DTINet, and PairwiseMKL methods. Our SMPSL model successfully preserved this predictive power. By applying the summation strategy, we not only retained the structural integrity of the PSL rules, but also achieved a slightly improved AUC score (0.929), confirming that our efficiency optimizations do not compromise the accuracy.

Analysis of Dataset II: Dataset II presents a massive scalability challenge, with a meta-path count exceeding —over 100,000 times larger than Dataset I. Consequently, computational baselines such as standard PSL, DTINet, and PairwiseMKL failed to converge within the 168 h time limit. For the meta-path + SVM method, execution was only possible by sampling 1% of the training data. Despite these challenges, SMPSL achieved the highest performance (AUC: 0.917, AUPR: 0.815) without requiring downsampling, demonstrating its capability of handling large-scale heterogeneous networks.

Analysis of Dataset III: The results on Dataset III revealed a critical insight regarding sampling-based methods. While SMPSL and DTINet achieved a strong performance (AUC > 0.91), the meta-path + SVM method notably underperformed, yielding an AUC of 0.509 and an AUPR of 0.505. This near-random performance can be attributed to two compounding factors:

- Aggressive Downsampling: Due to the cubic complexity of kernel SVMs, we were forced to train on a sparse 1% sample of the data. In a network as complex as Dataset III, this tiny subset fails to capture the global topological structure required for accurate predictions.

- Balanced Class Distribution: Unlike the other datasets, Dataset III utilized a balanced 1:1 ratio of positive to negative links. In highly imbalanced scenarios, a model might achieve deceptively high AUC scores by exploiting majority class bias. However, in a strictly balanced setting, a model that cannot learn the true decision boundary will converge to a random guess (AUC ≈ 0.5).

Therefore, the failure of SVM on Dataset III highlights the risk of sampling large-scale network data. In contrast, SMPSL utilizes a summation strategy to process the full dataset efficiently, allowing it to learn robust features and achieve promising results (AUC of 0.928) without information loss.

6.4.2. Running Time and Efficiency Analysis

A key contribution of SMPSL is its summation strategy, which significantly reduces the number of rule instances required for inference. To demonstrate this efficiency, we compared the wall-clock running time of all the approaches. Experiments were conducted on a workstation equipped with a dual 3.3 GHz Intel Xeon CPU (16 cores) and 128 GB of RAM.

As shown in Table 4, pairwiseMKL is the most computationally expensive method for Dataset I (386 min), which aligns with the findings of Cichonska et al. [9], where it required 1.45 h for a smaller network.

Table 4.

Running time comparison (in min). Entries marked with ‘*’ indicate results obtained from a downsampled subset (1%) due to computational constraints. SMPSL achieved an orders-of-magnitude speedup on large datasets.

Most notably, SMPSL reduced the running time by over 99% compared to the original PSL model while maintaining or improving the accuracy. On the large-scale Dataset II, where standard PSL and DTINet timed out, SMPSL finished in just 2.03 min. This confirms that SMPSL transforms the complexity of the problem, making it feasible for real-world, large-scale drug discovery applications.

6.4.3. Ablation Study: Impact of Weight Learning

We performed an ablation study to verify the contribution of the weight-learning module. Table 5 compares the performance of SMPSL with and without the weight-learning component.

Table 5.

Ablation study: Effectiveness and running time with and without weight learning.

The results indicate that weight learning is positively correlated with the model performance, particularly for the AUPR metric. This was most evident for datasets with a high level of class imbalance. For example, in Dataset I (positive/negative ratio ≈ 1:45), the inclusion of weight learning improved the AUPR from 0.552 to 0.617. Although weight learning introduces a slight computational overhead, the cost is negligible compared to the performance gains in precision and recall.

6.4.4. Case Study: Meta-Path Selection

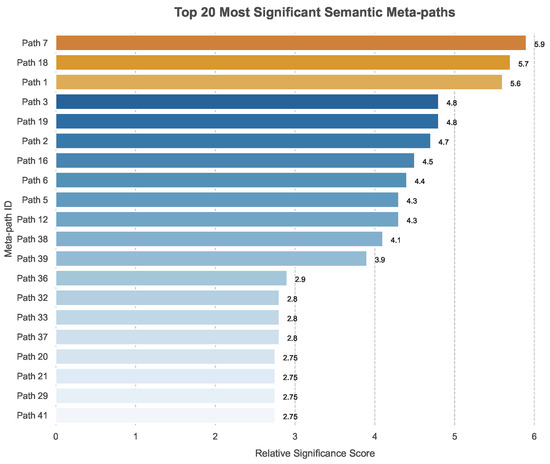

To understand the biological interpretability of our model, we analyzed the learned weights (w) of the meta-paths in Dataset II. Figure 3 illustrates the relative importance of different meta-paths on a log scale.

Figure 3.

The log-scale importance of the relative weight parameter w in Dataset II.

The weight parameter indicates the predictive power of a specific topological structure. The top six most effective meta-paths identified by our model were . Two key conclusions can be drawn from this ranking:

- Path Length: Shorter meta-paths () tend to be assigned higher weights. This suggests that direct or low-order indirect associations are more reliable predictors of drug–target interactions than long, complex paths.

- Data Modality: The top-ranked meta-paths relied exclusively on interaction and similarity measures. This aligns with the domain knowledge that explicit interaction data and chemical/sequence similarity are the strongest indicators in DTI prediction tasks, compared to noisier auxiliary information.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, we present the summated meta-path probabilistic soft logic (SMPSL) model, a novel framework for drug–target interaction (DTI) predictions. We formulated the DTI prediction task as an inference problem on a heterogeneous information network, integrating multiple domain-specific measures such as similarities, associations, and interactions. The core contribution of our work is the development of an efficient summation strategy that bridges the gap between meta-path-based topological features and probabilistic logic. By generating probabilistic commuting matrices based on a Bayesian approach, we successfully transformed complex topological structures into concise probabilistic metrics. This strategy effectively serves as a “shortcut,” allowing us to use the values of commuting matrices as rule instances. Consequently, we addressed the scalability bottleneck inherent in traditional PSL models, achieving a reduction of over 99% in the computational time while maintaining—and in many cases, surpassing—the performance in terms of the AUC and AUPR scores. Our extensive experiments on three large-scale datasets demonstrate that SMPSL provides a robust and scalable solution where traditional methods often fail due to computational exhaustion.

Beyond the specific domain of DTI prediction, the proposed SMPSL framework holds significant potential for broader applications. Since both meta-path analyses and PSL are fundamental tools in network science, our summation strategy can be generalized to other complex network tasks, including spammer detection, schema mapping, and recommendation systems. This versatility motivates future work aimed at exploring the full potential of SMPSL in handling diverse, large-scale heterogeneous networks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S.; methodology, S.Z. and Y.S.; software, S.Z.; validation, S.Z.; formal analysis, S.Z.; resources, Y.S.; data curation, S.Z.; writing—original draft, S.Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.S.; visualization, S.Z.; supervision, Y.S.; project administration, Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Overseas Expertise Introduction Center for Discipline Innovation (“111 Center”) (Grant No. BP0820029).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from Luo DTI Prediction at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-00680-8 and Yizhou Sun DTI Prediction at https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-016-1005-x.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1 lists the complete set of 51 meta-paths defined for Dataset II.

Table A1.

Complete list of semantic meta-paths defined for Dataset II.

Table A1.

Complete list of semantic meta-paths defined for Dataset II.

| Index | Semantics |

|---|---|

| C1 | |

| C2 | |

| C3 | |

| C4 | |

| C5 | |

| C6 | |

| C7 | |

| C8 | |

| C9 | |

| C10 | |

| C11 | |

| C12 | |

| C13 | |

| C14 | |

| C15 | |

| C16 | |

| C17 | |

| C18 | |

| C19 | |

| C20 | |

| C21 | |

| C22 | |

| C23 | |

| C24 | |

| C25 | |

| C26 | |

| C27 | |

| C28 | |

| C29 | |

| C30 | |

| C31 | |

| C32 | |

| C33 | |

| C34 | |

| C35 | |

| C36 | |

| C37 | |

| C38 | |

| C39 | |

| C40 | |

| C41 | |

| C42 | |

| C43 | |

| C44 | |

| C45 | |

| C46 | |

| C47 | |

| C48 | |

| C49 | |

| C50 | |

| C51 |

References

- Chen, X.; Yan, C.C.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Dai, F.; Yin, J.; Zhang, Y. Drug–target interaction prediction: Databases, web servers and computational models. Briefings Bioinform. 2016, 17, 696–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fourches, D.; Muratov, E.; Tropsha, A. Trust, But Verify: On the Importance of Chemical Structure Curation in Cheminformatics and QSAR Modeling Research. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2010, 50, 1189–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, H.; Takigawa, I.; Mamitsuka, H.; Zhu, S. Similarity-based machine learning methods for predicting drug–target interactions: A brief review. Briefings Bioinform. 2014, 15, 734–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildirim, M.A.; Goh, K.I.; Cusick, M.E.; Barabási, A.L.; Vidal, M. Drug-target network. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007, 25, 1119–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhraei, S.; Huang, B.; Raschid, L.; Getoor, L. Network-Based Drug-Target Interaction Prediction with Probabilistic Soft Logic. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2014, 11, 775–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getoor, L.; Diehl, C.P. Link Mining: A Survey. SIGKDD Explor. Newsl. 2005, 7, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, L.; Zhou, T. Link prediction in complex networks: A survey. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2011, 390, 1150–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, G.; Ding, Y.; Seal, A.; Chen, B.; Sun, Y.; Bolton, E. Predicting drug target interactions using meta-path-based semantic network analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2016, 17, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichonska, A.; Pahikkala, T.; Szedmak, S.; Julkunen, H.; Airola, A.; Heinonen, M.; Aittokallio, T.; Rousu, J. Learning with multiple pairwise kernels for drug bioactivity prediction. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i509–i518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, J.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Kuang, W.; Peng, J.; Chen, L.; Zeng, J. A network integration approach for drug-target interaction prediction and computational drug repositioning from heterogeneous information. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmig, A.; Bach, S.H.; Broecheler, M.; Huang, B.; Getoor, L. A Short Introduction to Probabilistic Soft Logic. In Proceedings of the NIPS Workshop on Probabilistic Programming: Foundations and Applications, Lake Tahoe, NV, USA, 7–8 December 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bach, S.H.; Broecheler, M.; Huang, B.; Getoor, L. Hinge-Loss Markov Random Fields and Probabilistic Soft Logic. J. Mach. Learn. Res. JMLR 2017, 18, 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Bach, S.H.; Huang, B.; London, B.; Getoor, L. Hinge-loss Markov Random Fields: Convex Inference for Structured Prediction. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1309.6813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockell, S.J.; Weile, J.; Lord, P.; Wipat, C.; Andriychenko, D.; Pocock, M.; Wilkinson, D.; Young, M.; Wipat, A. An integrated dataset for in silico drug discovery. J. Integr. Bioinform. 2010, 7, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Liu, C.; Jiang, J.; Lu, W.; Li, W.; Liu, G.; Zhou, W.; Huang, J.; Tang, Y. Prediction of drug-target interactions and drug repositioning via network-based inference. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2012, 8, e1002503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamanishi, Y.; Araki, M.; Gutteridge, A.; Honda, W.; Kanehisa, M. Prediction of drug–target interaction networks from the integration of chemical and genomic spaces. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, i232–i240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, M.; Miao, C.; Zhao, P.; Li, X.L. Neighborhood regularized logistic matrix factorization for drug-target interaction prediction. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2016, 12, e1004760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzat, A.; Zhao, P.; Wu, M.; Li, X.; Kwoh, C. Drug-Target Interaction Prediction with Graph Regularized Matrix Factorization. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2017, 14, 646–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Ding, Y.; Wild, D.J. Assessing drug target association using semantic linked data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2012, 8, e1002574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlman, L.; Gottlieb, A.; Atias, N.; Ruppin, E.; Sharan, R. Combining drug and gene similarity measures for drug-target elucidation. J. Comput. Biol. 2011, 18, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzat, A.; Wu, M.; Li, X.L.; Kwoh, C.K. Drug-target interaction prediction via class imbalance-aware ensemble learning. BMC Bioinform. 2016, 17, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzat, A.; Wu, M.; Li, X.L.; Kwoh, C.K. Drug-target interaction prediction using ensemble learning and dimensionality reduction. Methods 2017, 129, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, M.; Zhang, Z.; Niu, S.; Sha, H.; Yang, R.; Yun, Y.; Lu, H. Deep-learning-based drug–target interaction prediction. J. Proteome Res. 2017, 16, 1401–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, H.; Yin, W.; Wang, J.; Zhang, G.; Liang, W.; Luo, J.; Yan, C. Drug-drug interactions prediction based on deep learning and knowledge graph: A review. iScience 2024, 27, 109148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, K.T.; Ansari, M.I.; Zhang, W. DTI-LM: Language model powered drug–target interaction prediction. Bioinformatics 2024, 40, btae533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.; Feng, Z.; Song, X.; Wu, X.J.; Kittler, J. MMDG-DTI: Drug–target interaction prediction via multimodal feature fusion and domain generalization. Pattern Recognit. 2025, 157, 110887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishart, D.S.; Knox, C.; Guo, A.C.; Cheng, D.; Shrivastava, S.; Tzur, D.; Gautam, B.; Hassanali, M. DrugBank: A knowledgebase for drugs, drug actions and drug targets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 36, D901–D906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S.; Furumichi, M.; Tanabe, M.; Hirakawa, M. KEGG for representation and analysis of molecular networks involving diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 38, D355–D360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, B.; Fu, C.; Chen, X. DCDB: Drug combination database. Bioinformatics 2009, 26, 587–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, S.; Kuhn, M.; Dunkel, M.; Campillos, M.; Senger, C.; Petsalaki, E.; Ahmed, J.; Urdiales, E.G.; Gewiess, A.; Jensen, L.J.; et al. SuperTarget and Matador: Resources for exploring drug-target relationships. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 36, D919–D922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbeck, C.; Hoppe, C.; Kuhn, S.; Floris, M.; Guha, R.; Willighagen, E.L. Recent developments of the chemistry development kit (CDK)-an open-source java library for chemo-and bioinformatics. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2006, 12, 2111–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keiser, M.J.; Setola, V.; Irwin, J.J.; Laggner, C.; Abbas, A.I.; Hufeisen, S.J.; Jensen, N.H.; Kuijer, M.B.; Matos, R.C.; Tran, T.B.; et al. Predicting new molecular targets for known drugs. Nature 2009, 462, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamb, J. The Connectivity Map: A new tool for biomedical research. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2007, 7, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamb, J.; Crawford, E.D.; Peck, D.; Modell, J.W.; Blat, I.C.; Wrobel, M.J.; Lerner, J.; Brunet, J.P.; Subramanian, A.; Ross, K.N.; et al. The Connectivity Map: Using gene-expression signatures to connect small molecules, genes, and disease. Science 2006, 313, 1929–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resnik, P. Semantic similarity in a taxonomy: An information-based measure and its application to problems of ambiguity in natural language. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 1999, 11, 95–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrbo, A.; Begović, B.; Skrbo, S. Classification of drugs using the ATC system (Anatomic, Therapeutic, Chemical Classification) and the latest changes. Med. Arh. 2004, 58, 138–141. [Google Scholar]

- Bleakley, K.; Yamanishi, Y. Supervised prediction of drug–target interactions using bipartite local models. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2397–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, E.; Bairoch, A.; Duvaud, S.; Phan, I.; Redaschi, N.; Suzek, B.E.; Martin, M.J.; McGarvey, P.; Gasteiger, E. Infrastructure for the life sciences: Design and implementation of the UniProt website. BMC Bioinform. 2009, 10, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Thiessen, P.A.; Bolton, E.E.; Chen, J.; Fu, G.; Gindulyte, A.; Han, L.; He, J.; He, S.; Shoemaker, B.A.; et al. PubChem substance and compound databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 44, D1202–D1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiao, J.; Suzek, T.O.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Bryant, S.H. PubChem: A public information system for analyzing bioactivities of small molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, W623–W633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshava Prasad, T.; Goel, R.; Kandasamy, K.; Keerthikumar, S.; Kumar, S.; Mathivanan, S.; Telikicherla, D.; Raju, R.; Shafreen, B.; Venugopal, A.; et al. Human protein reference database—2009 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 37, D767–D772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.P.; Murphy, C.G.; Johnson, R.; Lay, J.M.; Lennon-Hopkins, K.; Saraceni-Richards, C.; Sciaky, D.; King, B.L.; Rosenstein, M.C.; Wiegers, T.C.; et al. The comparative toxicogenomics database: Update 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 41, D1104–D1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, M.; Campillos, M.; Letunic, I.; Jensen, L.J.; Bork, P. A side effect resource to capture phenotypic effects of drugs. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2010, 6, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).