Abstract

This article investigates the problem of univariate and bivariate density estimation using wavelet decomposition techniques. Special attention is given to the estimation of copula functions, which capture the dependence structure between random variables independent of their marginals. We consider two distinct frameworks: the case of independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) variables and the case where variables are dependent, allowing us to highlight the impact of the dependence structure on the performance of wavelet-based estimators. Building on this framework, we propose a novel iterative thresholding method applied to the detail coefficients of the wavelet transform. This iterative scheme aims to enhance noise reduction while preserving significant structural features of the underlying density or copula function. Numerical experiments illustrate the effectiveness of the proposed method in both univariate and bivariate settings, particularly in capturing localized features and discontinuities in the presence of varying dependence patterns.

MSC:

60; 62

1. Introduction

The theoretical foundation of wavelets was laid in the early works of Grossman and Morlet since 1984 [1], who introduced the concept of wavelet transforms as a tool for time-frequency analysis to approximate potentially highly irregular functions or surfaces. This pioneering work was later formalized by Meyer [2] and Daubechies [3], who constructed orthogonal and compact wavelet bases, enabling efficient multiresolution analysis (MRA), which is a functional framework allowing one to represent a function as a limit of its approximations at different levels of resolution. Mallat [4] further revolutionized the field by developing the fast wavelet transform, providing a practical algorithmic framework for wavelet decomposition and reconstruction. For the theory on developing wavelet systems, we refer to the works of Härdle et al. [5], Tsybakov [6], and Vidakovic [7]. These breakthroughs enabled the application of wavelets in a wide range of fields, including signal processing, image analysis, and numerical solutions of differential equations.

Linear wavelet estimators have been studied by several authors, including Kerkyacharian and Picard [8,9], Antoniadis and Carmona [10], Walter [11,12] who established mean squared error convergence results of wavelet estimators in the case of continuous densities. A nonlinear estimation method based on thresholding techniques was proposed by Donoho and Johnstone [13,14]. This leads to defining a threshold value to identify the coefficients with a high contribution (the choice of this threshold is very important and guarantees the asymptotic properties of the estimator). Several approaches are used to determine the optimal threshold. Donoho [14] presented a universal threshold by analyzing a normal Gaussian noise model; a threshold chooser based on Stein’s unbiased risk estimation was proposed by Donoho and Johnstone [15], and methods based on cross-validation were developed with Naeson [16]. Vidakovic [17] adopts a Bayesian approach. An iterative thresholding approach proposed by and applied to physical sound analysis by Hadjileontiadis et al. [18] is an evaluation of this approach through a fixed-point formulation presented by Ranta et al. [19]. An adaptation of this method in the context of density estimation is one of the objectives of this article. On the other hand, for bivariate data, copula functions have become increasingly popular tools in data analysis. They allow modeling the dependency structure between random variables, regardless of their marginal distribution, based on Sklar’s theorem in 1959 [20]. This disengagement between margins and dependence makes copulas particularly effective in capturing complex relationships between assets, considering phenomena such as asymmetric dependencies or extreme events, which are often overlooked by traditional measures. The books by Joe [21] and Nelsen [22] describe the mathematical and statistical foundations of copulas.

Nonparametric estimators of copula densities based on wavelet decomposition have been suggested by Genest, Masiello, and Tribouley [23] who proposed a wavelet-based estimator for a copula function, and they established the convergence results for the linear estimator. Autin et al. [24] generalized these results in the multivariate framework for the nonlinear estimator. Recent studies have advanced wavelet-based copula estimation. Chatrabgoun et al. [25] proposed a Legendre multiwavelet approach. More recently, Provost [26] reviewed nonparametric copula density methods (see also Falhi and Hmood [27]), while Pensky and De Canditiis [28] refined minimax thresholding theory for wavelet applications.

In the context of -mixing dependence, various nonparametric problems have been examined. Recent developments can be found in, for example, Bouezmarni et al. [29] and Chesneau [30].

Our contributions in this article are as follows: firstly, we present the fixed-point iterative thresholding algorithm and its convergence conditions to estimate the univariate density function. Secondly, we establish the wavelet copula density estimator in the case where the variables are independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) and the case where the variables are weakly dependent, forming a sequence of stationary mixtures, we provide a detailed mathematical analysis of the estimator’s statistical properties, including its bias, variance, and mean integrated squared error, thereby establishing theoretical guarantees for its performance under each dependence structure.

The rest of the paper is as follows: Section 2 presents the fixed-point iterative thresholding approach. Section 3 gives an overview of the wavelet copula estimators in two cases. Section 4 shows the results of the simulation experiments and empirical application. Some conclusions are provided in Section 5. Section 6 provides a discussion on the limitations of our study and outlines potential directions for future research.

2. Wavelet Thresholding Estimator in the Univariate Case

This section aims to present the theoretical and methodological foundations of the proposed approach. We first introduce the construction and properties of the wavelet basis used for the estimation procedure. Then, we describe the nonparametric estimation of the density function in the wavelet domain. Finally, we detail the iterative fixed-point thresholding method developed for adaptive noise reduction and optimal estimation.

2.1. Threshold Determination Based on Iterative Fixed-Point Approach

From a mother wavelet and a father wavelet bases of , the wavelet collection is obtained by translations and dilations as follows:

Any can be represented as follows:

where , .

A wavelet estimator of f can be written simply by

Remark 1.

In the case of an i.i.d. sample , empirical estimates of the coefficients and are given by: and

The estimated detail coefficients are considerable and must be limited by a thresholding method, which consists of conserving only the important coefficients estimated and eliminating the small, estimated coefficients that do not provide any information. This method can be applied locally to each coefficient or globally to a set of coefficients of every level.

There are two well known thresholding functions named the hard thresholding function and the soft thresholding function. The first, hard thresholding, suggests the annulment of all coefficients under the threshold value and keeps the other coefficients unchanged. More precisely, the coefficients will be substituted as follows:

The second type is soft thresholding, which, additionally, shrinks the larger coefficients towards zero:

The universal value of is given by Donoho and Johnstone [13,15], under the assumption of white Gaussian noise, by

where N is the number of data points, and is an estimate of the noise level (typically a scaled median absolute deviation of the empirical wavelet coefficient). The iterative wavelet denoising method was initially proposed by Coifman and Wickerhauser [31] and applied to physiological sound analysis by Hadjileontiadis et al. [18]. The goal of this method is to separate the stationary part from the non-stationary part of a signal. An improvement of this iterative algorithm was processed by Ranta et al. [19] based on a fixed-point-type interpretation. Given wavelet coefficients estimated from the data, under the additive model and orthonormal basis, we can write:

where are the informative coefficients and are the noisy coefficients.

The principle of iterative thresholding consists of repeating the threshold operation (hard or soft) several times; after two iterations, we can write the model as

The threshold value is calculated at each iteration t according to the standard deviation of the coefficient , as follows:

where is a user defined constant, a classical choice is . Consider the function g defined as follows:

and taking values in a finite set of real numbers in ( when ), g is continuous, monotonic (increasing) and positive.

The update threshold value at each iteration is expressed as follows:

The iterations are interrupted by the validation of a certain stop criterion , exactly when no element from the set of is considered a significant coefficient ,

which is equivalent to saying that between two successive iterations, the threshold value stays constant . Therefore, Equation (7) can be written in another way as

In conclusion, the stopping criterion is validated by a fixed point of the function g defined previously in (5) and that this point is the final threshold value. At the end of this algorithm, the reconstruction phase is applied by Inverse Discrete Wavelet Transform, and we obtain the thresholded density estimate.

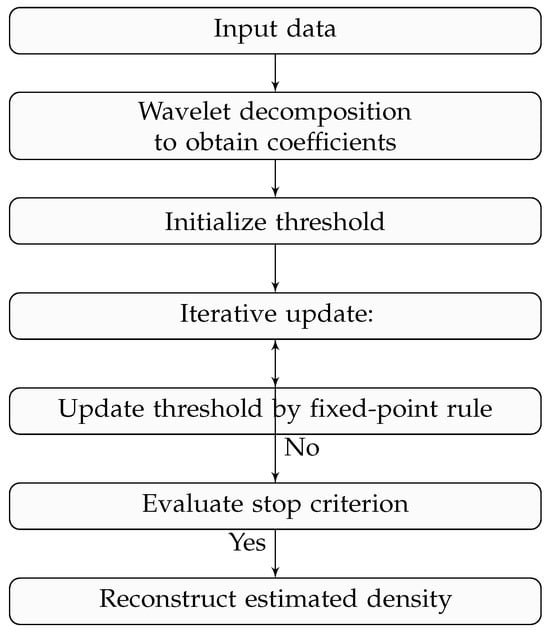

To illustrate the main steps of the proposed method, Figure 1 presents the algorithmic flow of the fixed-point iterative wavelet thresholding procedure for density estimation. The process begins with the wavelet decomposition of the empirical density, followed by iterative threshold updates until convergence is achieved, resulting in a smooth and adaptive estimate of the density function.

Figure 1.

Algorithmic flowchart of the fixed-point iterative wavelet thresholding method.

Algorithm 1 below includes the steps of the fixed-point wavelet thresholding.

| Algorithm 1 Iterative Wavelet Thresholding algorithm with fixed point(FPWT) |

|

Proposition 1.

If the density probability of the wavelets coefficients with zero mean, finite variance, and a mode of 0. A sufficient condition under which the function g defined in (5) admits at least one non-null fixed point with is that

Proof.

By applying the intermediate value theorem, and since the function defined in (5) continuous on an interval , g has a fixed point if ∀, . Since g is monotone increasing, we must prove that there exists an interval with and .

Since is finite, let , , .

Let us consider , partial integration .

Under the initial hypothesis, has a mode in 0. One can find a such as is decreasing on . Then, the derivative , so and when , i.e., when . □

Although this condition is sufficient but not necessary, smaller values of may still suffice ensure convergence. The function g can admit multiple fixed points; the iterative procedure produces decreasing threshold values and converges to the largest fixed point, which satisfies the stopping criterion and defines the final threshold.

Proposition 2.

The largest fixed point of the function g defined in (5) is not missed by the iterative algorithm.

Proof.

Us suppose that the largest fixed point of the function g is missed by the iterative algorithm. That means that there exists and ∀ iteration t. This can be further rewritten as there exists t such that t such as .

But, so the first inequality rewrites as . On the other hand, g is monotonically increasing, so the second inequality implies which implies , which contradicts the first inequality. So, the hypothesis made at the beginning is false: the largest fixed point is not missed by the iterative algorithm. □

2.2. Case of Gaussian Generalized Distribution

This paragraph aims to determine the convergence conditions of the iterative fixed-point algorithm under the assumption that the coefficients obey a generalized Gaussian distribution.

Definition 1.

The Generalized Gaussian Distribution (GGD) is defined as follows:

with , and , where σ is the standard deviation and is the shape parameter of the probability law ( for a Gaussian and for the Laplace positive density function (pdf)).

The conditions of the preceding Proposition 1 (which are close to real conditions) ensure that the function g is monotonically increasing, and there exists an interval with and (i.e., ). This implies that the coefficient must be bounded by a minimum value, . Indeed, if is chosen to be less than , the algorithm converges to 0, which means that the estimated noise is zero at the scale considered. This minimum value depends on the probability distribution of the wavelet coefficients, ), and its expression is proposed by Ranta et al. [19] in the case of a generalized Gaussian distribution in the next proposition.

Proposition 3.

Using a generalized Gaussian model for the pdf of the wavelet coefficients , the lower bound is independent of σ and depends only on the shape parameter u. is given as follows:

Proof.

The inequality (9) can be written

that is

The objective is to determine the lowest value of (denoted such that there exists one verifying (12).

Let the function is differentiable and strictly convex due to the regularity of the exponential term (), it can have 0, 1, or 2 intersection points with the identity line . Thus, is obtained when is tangent (at a point of abscissa ) to the line . The bound value corresponds to the tangency point where and meet with identical slope, i.e.,

Solving this system yields the explicit lower bound:

A simple calculation gives us the bound :

The lower bound is independent of and depends only on the shape parameter u. □

The following proposition gives the value in the cases of Gaussian and Laplace distributions.

Proposition 4.

Cases of Gaussian and Laplace distribution, we have

- Gaussian distribution (u = 2): .

- Laplace distribution (u = 1): .

Theorem 1.

Assume that is the Besov ball of radius on with smoothness and integrability indices . Using the GGD model for the wavelet coefficients, the fixed-point iteration converges to a unique fixed value at each scale j. The resulting estimator satisfies

where s is the smoothness of f and C is a Constant depends on

Proof.

We see that this error is divided into two terms: the stochastic error due to the random nature of the observations and the bias error due to the estimation approach used.

On the one hand, thresholding preserves coefficients with . For smooth densities f in Besov space , wavelet coefficient decay as .

The bias is dominated by discarded coefficients below as where is the coarsest scale with .

On the other hand, the variance arises from retained noisy coefficients satisfying ; thresholding retained coefficients, so . Balancing bias and variance yields: , which implies the constant C depend on via (thresholds control the bias-variance trade-off). □

This completes the proof for finite sample guarantees; see Donoho and Jhonoston [13] on wavelet shrinkage minimax rates.

The next section addresses the estimation of copula densities using wavelet-based methods under both independent and dependent settings. We analyze the estimator’s statistical properties: bias, variance, and mean integrated squared error for (i.i.d) and mixing dependent cases, providing theoretical performance guarantees. Finally, the copula density is estimated using the fixed-point thresholding approach introduced in Section 2.

3. Wavelet Estimator of Copula Density

In many applied fields, such as finance, insurance, and environmental science, understanding nonlinear and extreme dependence between variables is essential. Since classical parametric copulas often fail to capture complex local dependence, this motivates the use of wavelet-based methods.

In this paper, we propose a wavelet-based copula density estimator and study its performance under independent and weakly dependent -mixing settings. We analyze its bias and variance and introduce a fixed-point wavelet thresholding procedure that adapts to the unknown dependence structure, making it particularly suitable for financial risk management and extreme event modeling.

We begin this section by introducing the basic concept of copula, which provides a powerful framework for modeling dependence between random variables.

3.1. Basic Concept of Copula

Given a bivariate random vector , denote its joint cumulative distribution function (cdf) by H and corresponding marginal distributions by F and G. According to Sklar (1959) [20], we can rewrite the joint distribution:

where C is the bivariate copula function. If F and G are continuous, C is unique. The copula approach facilitates multivariate analyses by allowing separate modeling of the marginal distributions and copula, which completely characterizes the dependence between X and Y. We may write

where and denote the generalized left continuous inverses of F and G.

An important property of a copula is that it can capture the tail dependence: the upper tail dependence exists when there is a positive probability of positive outliers occurring jointly, while the lower tail dependence is a negative probability of negative outliers occurring jointly. Formally, and are defined, respectively, as follows:

The copula is differentiable on , its density exists and is as follows:

In the rest of this section, we consider the problem of copula density estimation in the case where the variables are i.i.d and the case of weak dependence: forming a sequence of stationary mixtures.

3.2. Case of Independent Variables

Let be a given scaling function, and let be the associated wavelet. It is assumed henceforth that both functions are real-valued and have compact support [0, L] for some . For every , , let: and be an orthonormal basis of .

Where and .

The wavelet representation of the density c is as follows:

where

is a trend (or approximation) and

is a sum of details of three types: vertical , horizontal , and oblique . In this representation, the coefficients are as follows:

and for

Then, the wavelet-based estimator of c is then given by :

where

where

and

where

When F and G are unknown, they are replaced by their empirical counterparts and . The pseudo-observations , based on the ranks of and , serve as empirical approximations of the unobservable pairs , forming a sample from the true copula C. The copula density estimator is then constructed from these pseudo-observations and it is given by

where

where

and

for we obtain the following:

Definition 2.

Consider Besov spaces as functional spaces because they are characterized in terms of wavelet coefficients as follows. Besov spaces depend on three parameters , , and , and are denoted by . Let . Define the sequence norm of the wavelet coefficients of a function as follows:

where

Proposition 5.

The difference between empirical and theoretical coefficients

Proof of Proposition 5.

Starting now with A:

We have , so we can apply Taylor to and there exist and such that

So

So using

Without losing the generality, starting now with , using the same methods than A, we have

the same calculation in (31) we have □

Theorem 2.

The bias of the estimators satisfies:

Proof.

Using Proposition 5 we have

and

□

Theorem 3.

The estimator variance of satisfies:

Proposition 6.

(a) There exists a constant such that, for any and .

- (b)

- There exists a constant such that, for any and

- (c)

- Let there exists a constant such that, for any κ large enough, and we have

Proof of Proposition 6.

(a)

- (b)

- Without losing the generality for

- (c)

- Lemma 1 (Bernstein’s inequality).Let be i.i.d bounded random variables, such that .

- Then,

Applying Lemma 1 to and noting that , let so we can conclude that, if is large enough

The same for

□

Proof.

Using Proposition 5 we have

Starting now with

Starting now with A: We apply the inequality of Holder we find the following:

and

using Jenson ’s inequality and using Proposition 5

using (37) and (39) we have we obtain the following:

Starting now with

Using Holder’s inequality from points (b) and (c) of Proposition 6.

Now starting with

we apply Holder’s inequality twice in succession:

□

Lemma 2.

Using point a of Proposition 6 and we have

Proof of Lemma 10 using Jenson’s inequality, and a of Proposition 6.

so using (65) and (66) and we have

□

Lemma 3.

Using the point (b) and (c) of Proposition 6 and (65) we have

Proof of Lemma 11.

Using Holders’ inequality and using points (b) and (c) of proposition (6).

using (65), (67) and using we obtain:

□

3.3. Under Depend Variables

Definition 3.

We aim to estimate an unknown function f via n random variables , , … , from defined on a probability space a strictly stationary stochastic process defined on a probability space . We suppose that has a α mixing dependence structure with exponential decay rate; , and such that:

where

is σ-algebra generated by the random variables: … , , and is σ-algebra generated by the random variables: , , ….

We make the following assumptions on the model in Definition 3. Assume that the copula belong to the Besov space defined in Definition 2 and consider the following hypothesis

We suppose the following:

Hypothesis 1.

The mother wavelet Ψ is bounded and compactly supported.

Hypothesis 2.

Φ is rapidly decreasing i.e, for every integer there exists a constant such that

Hypothesis 3.

It is supposed that there exists a function q: such that , any integer and

where denotes the expectation.

Hypothesis 4.

There exist two constants, and , satisfying, for any integer and

for any integer and .

then,

where is the integer satisfying

where denotes the integer part of a, satisfies

and

These boundedness assumptions are standard for the model under -mixing dependence; these assumptions concern the wavelet basis and the -mixing process. They are inspired by Chesneau [30] and are useful for our adaptive wavelet estimator and its properties.

Theorem 4.

Proof.

Using (30) we have

So using

Without losing the generality starting now with so using the same methods then A we have

Lemma 4.

Let be the density of and let be the density of for any . We suppose that there exists a constant such that

there exist two constants and , satisfying for ;

for any

where denotes the covariance that is

Proof of (50).

Using Sklar and and

□

Proof of (56).

□

□

Proposition 7.

Suppose that the assumptions H1, H2, H3, and H4 hold, then

- (a)

- (b)

- there exists a constant such that, and .

- (c)

- There exists a constant such that, for any and

- (d)

- Let be defined as in there exists a constant such that, for any κ large enough, and we have

Proof of Proposition 7.

Therefore,

owing to Lemma 6 applied with ,

taking large enough, the last term is bounded by . □

- (a)

- whereIt follows that , whereLemma 5(Davydov’s inequality [32]). Let be strictly stationary process α mixing process with mixing coefficient and let h and k be two measurable functions. Let and satisfying such that and exist. Then, there exists a constant such thatThe Davydov’s inequality described in Lemma 5 with , and

- (b)

- (c)

- It follows from the triangular inequality and thatThe inequality and the point (a) of proposition:

- (d)

- Lemma 6(Liebscher’s inequality [33]). Let be a strictly stationary process with the mth strongly mixing coefficient , , let n be a positive integer, let be a measurable function, and for any , .We assume that: and there exists a constant satisfying . Then, for any and , we havewhere

We will use the Liebscher’s inequality in Lemma 6 let us set

we have and by ,

(so .

- for any integer , since , we show that

, , .

- We obtain

Proof.

□

Lemma 7.

Proof.

Starting with Proof of Lemma 7, with out losing the generality

□

Lemma 8.

Using Proposition (7), (a), (b) and (c), we have

Proof.

so we have A. □

Using Proposition 7a

Starting now with

using Holder ’s inequality: using points (b) and (c) of Proposition 7:

using Holder’s inequality, (37), (64) and

Lemma 9.

we applyHolder’s inequality twice in succession:

Lemma 10.

Using point (a) of Proposition 7 and , we have

Proof of Lemma 10.

Using Jenson’s inequality, and point (a) of Proposition 7

so using (65), (66) and using we have

□

Lemma 11.

Using points (b) and (c) of Proposition 7 and and (65) we have

Proof of Lemma 11.

Using Holder s’ inequality and using points (b) and (c) of Proposition 7.

using (65), (67) and using we obtain the following:

□

3.4. Copula Estimation with Iterative Fixed Point Thresholding

In this paragraph, we extend the iterative wavelet thresholding framework to the estimation of copula densities. Unlike classical wavelet-based copula estimators, the proposed fixed-point iterative procedure adaptively updates the threshold to balance noise suppression and structural preservation in the joint dependence function. This adaptive behavior is particularly advantageous in financial contexts, where copulas often exhibit localized tail dependencies and nonlinear patterns that require scale-sensitive denoising.

Let be a bivariate sample representing two financial assets. We are interested in estimating the copula density , which describes the dependence structure between X and Y, regardless of marginals. We define the pseudo-observations:

The wavelet estimator is given by

We wish to apply the fixed-point iterative thresholding method described in Section 2 to obtain an estimate of copula density. Three cases can be considered:

- Raw copula estimation: estimate from the original data using the original pseudo-observations .

- Both denoised data: After denoising both marginal by FPWT-iterative thresholding, yielding , then estimate .

- Partial denoising: Apply the method of denoising only to one of the marginal, to ; for example, to obtain , then estimate of .

In the next section, we consider an application of this approach for the estimation of univariate density and bivariate copula density in real financial data.

4. Empirical Results

This section applies the fixed-point iterative thresholding (FPWT) algorithm to univariate density estimation and compares it with classical thresholding methods. We then estimate the copula density between Bitcoin and the S&P 500, compare it with the empirical copula, and analyze its performance in both noisy and noise-free settings.

- Application 1: Density estimation with fixed point iterative thresholding

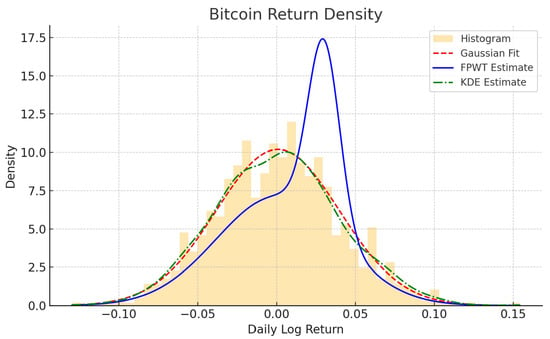

Considering the estimation of the density function under iterative thresholding (FPWT) compared to the kernel density estimation (KDE) method for Bitcoin’s closing prices covering the period from 4 January 2017 to 15 December 2023.

Figure 2 compares several density estimation methods for daily log returns of Bitcoin.

Figure 2.

FPWT vs. Gaussien vs. KDE for Bitcoin density estimation.

The histogram provides the empirical distribution, while the red dashed curve represents a Gaussian fit, assuming normality. The green dashed line (KDE) offers a smoothed non-parametric estimate, which better captures the distribution’s asymmetry and heavier tails. Notably, the blue line (FPWT) highlights finer structures and a sharper peak, indicating that the wavelet-based estimator detects local features and possibly multimodality missed by classical approaches. This suggests that FPWT provides a more adaptive and detailed estimation of Bitcoin return dynamics. To assess the performance of the proposed fixed-point iterative wavelet thresholding method, we compare it with several existing estimators commonly used in the literature. Quantitative performance measures such as the Mean Integrated Squared Error (MISE), bias, and variance are computed to highlight the advantages of the proposed approach in terms of adaptivity, accuracy, and robustness to dependence structures. The results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of univariate density estimation methods.

Comparing (FPWT) to other standard wavelet thresholding methods is a solid way to validate its performance. The results of the comparison are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparing denoising methods.

Iterative thresholding achieves the best MISE and SNR by adapting to the distribution of wavelet coefficients. Universal thresholding is fastest but tends to over smooth due to high sparsity. SureShrink and BayesShrink offer a compromise, balancing adaptivity and computational efficiency.

- Application 2: Empirical vs. FPWT iterative copula estimation

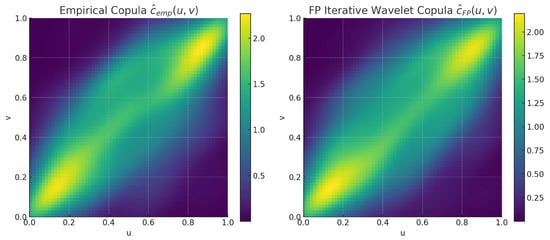

We consider daily log-returns of Bitcoin and the S&P 500 index over the period January 2020–December 2021 . Both series are standardized into pseudo-observations , which serve as inputs for nonparametric copula estimation. To assess the effect of wavelet-based denoising, we apply the fixed-point iterative thresholding procedure to the raw data before computing copula densities.

Figure 3 compares the empirical copula density with the FPWT iterative copula . The empirical estimate shows oscillations and irregularities, particularly in the tail regions, while the FPWT-iterative copula displays smoother contours and a clearer separation between regions of high and low dependence.

Figure 3.

Empirical vs. FPWT iterative copula estimation.

Table 3 reports global metrics comparing the two surfaces. The FPWT iterative method achieves an MISE of relative to the empirical copula and a high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of dB, confirming that thresholding removes spurious oscillations while preserving the variance of the dependence structure.

Table 3.

Metrics comparing of thersholding methods.

To further examine the impact on extremes, we compute the lower- and upper-tail dependence coefficients, and , at quantile levels and . The results are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Tail of dependence.

The results reveal that lower-tail dependence remains stable at moderate levels (), but increases slightly in the extreme case (), indicating that denoising clarifies joint negative extremes. Conversely, upper-tail dependence decreases after denoising, suggesting that part of the strong positive tail dependence in the raw estimate was noise-driven.

Overall, the FPWT iterative approach improves the interpretability of copula estimation for financial data. The method reduces noise, stabilizes the copula surface, and refines the measurement of tail co-movements. Importantly, it reveals stronger downside dependence while tempering spurious positive co-movements, which is consistent with the heavy-tailed and asymmetric nature of financial return distributions.

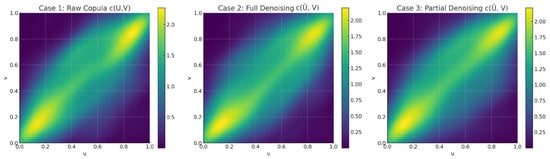

- Application 3: Estimation of the bivariate copula density with denoising by FPWT algorithm

The empirical dataset covers the period from 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2021, comprising daily log-return observations for Bitcoin (BTC) and the S&P 500 index. Bitcoin returns are modeled using a Student-t distribution with 5 degrees of freedom to capture the heavy-tailed nature and volatility patterns observed in cryptocurrency markets. The S&P 500 returns are generated as a linear combination of the Bitcoin returns and an independent heavy-tailed noise component, thereby introducing realistic positive dependence while retaining idiosyncratic variations.

Both series are transformed into pseudo-observations on the unit interval , enabling the nonparametric estimation of the copula density before and after wavelet-based fixed-point iterative denoising. This framework captures the interplay between marginal distributional features and the dependence structure under different noise-reduction scenarios.

We compare the estimation of the bivariate copula density in three distinct scenarios involving wavelet-based denoising of financial return data. In the first case, the copula is estimated directly from the raw pseudo-observations without any thresholding, resulting in a noisy and irregular surface, particularly in the tail and boundary regions. In the second case, both marginals are denoised using fixed-point iterative wavelet thresholding before computing the copula , yielding a significantly smoother and more interpretable structure. This version reveals clearer tail dependencies and more concentrated density contours. In the third case, only one marginal (e.g., X) is denoised, leading to the copula , which displays partial improvement, highlighting the asymmetric impact of noise on dependence estimation.

The results presented in Figure 4 confirm that applying wavelet thresholding, even partially, improves the accuracy and interpretability of copula estimates, especially when data are contaminated with noise or exhibit nonlinear dependencies.

Figure 4.

The estimation of the copula density in the three cases.

Comparison of metrics in three cases of denoising is given in Table 5.

Table 5.

Comparing thersholding methods.

Effects on tail dependence across the three cases of denoising are given in Table 6.

Table 6.

Tail of dependence in three cases of denoising.

The tail dependence analysis highlights the impact of wavelet-based fixed-point iterative denoising on the joint extreme behavior of Bitcoin and the S&P 500. In the lower tail, the dependence coefficient remains broadly stable at , but shows a slight increase for after denoising, indicating a clearer detection of joint negative extremes. In contrast, the upper tail coefficient decreases after denoising, most notably in the full denoising case, suggesting that part of the strong positive tail dependence observed in the raw data are attributable to noise. Partial denoising produces intermediate results, improving tail clarity without fully removing spurious dependence patterns. Overall, denoising appears to sharpen lower-tail dependence signals while tempering exaggerated upper-tail associations.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the effectiveness of the fixed-point iterative wavelet thresholding approach for nonparametric estimation in financial applications. At the univariate level, the method produces smoother and more accurate density estimates of return distributions compared to the raw empirical estimates. By suppressing spurious oscillations while retaining the heavy-tailed nature of financial data, it achieves a favorable trade-off between bias reduction and variance control.

At the bivariate level, when applied to copula density estimation, the FPWT iterative approach improves the readability of the dependence structure by eliminating high-frequency noise. This refinement leads to more stable metrics of joint dependence and sharper insights into extreme co-movements. In particular, the method enhances the detection of downside tail dependence, a crucial feature in risk management, while attenuating spurious upper-tail dependence often driven by noisy fluctuations.

Overall, the FPWT approach provides a robust and flexible tool for both marginal and dependence modeling in finance. Its ability to denoise, while preserving essential structural information, makes it especially valuable for studying heavy-tailed distributions, nonlinear dependencies, and tail risks in financial markets. Future work could extend this framework to higher-dimensional copulas and to real-time risk monitoring in dynamic market environments.

6. Discussion

Although wavelet-based density and copula estimators have been widely studied, many methods remain limited when handling noise, heavy tails, or dependence. Standard thresholding may cause over-smoothing or noise retention, and few approaches provide a unified adaptive framework for marginal and bivariate estimation. To address these issues, we propose a fixed-point iterative wavelet method for copula density estimation, tailored to weak dependence. Our approach fills a gap in the literature and is supported by rigorous theoretical results guaranteeing convergence, consistency, and statistical reliability.

The method has broad practical relevance. In finance, it models nonlinear and tail dependence between assets, improving stress testing and risk analysis. In insurance, it captures dependence among risk sources for solvency and capital allocation. In environmental and climate sciences, it is suitable for modeling complex dependence in non-stationary and extreme situations.

Future work will extend the method to higher-dimensional copulas, develop dynamic wavelet copula models for time-varying dependence, and integrate it into real-time risk monitoring and anomaly detection systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.B. (Heni Boubaker) and H.B. (Houcem Belgacem); methodology, H.B. (Heni Boubaker); software, H.B. (Houcem Belgacem); validation, H.B. (Houcem Belgacem); formal analysis, H.B. (Heni Boubaker); investigation, H.B. (Heni Boubaker) and H.B. (Houcem Belgacem). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to legal and ethical reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Probability Density Function | |

| CDF | Cumulative Distribution Function |

| MSE | Mean Integrated Squared Error |

| SNR | Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| Var | Variance |

| Cov | Covariance |

| FPWT | Fixed Point Wavelet Thresholding |

| WT | Wavelet Transform |

| DWT | Discrete Wavelet Transform |

| IDWT | Inverse Discrete Wavelet Transform |

| MRA | Multiresolution Analysis |

| i.i.d. | Independent and Identically Distributed |

| -mixing | -mixing dependence condition |

| GGD | Generalized Gaussiaan Distribution |

| STC | Stop Criterion |

| BTC | Bitcoin |

| Nomenclature | |

| X, Y | Random variables |

| Probability density function | |

| , | Estimates density function |

| , | Wavelet functions at scale j and position k |

| , | Detail Wavelet coefficients of the function f |

| Threshold value at resolution level j | |

| Threshold value level j and iteration t | |

| Noise standard deviation | |

| User defined constant | |

| Minimal value of | |

| , | Estimates copula density |

| J | Maximum resolution level |

| Lower tail of dependence | |

| Upper tail of dependence | |

| Informative wavelet coefficients at iteration t | |

| Noisy wavelet coefficients at iteration t |

References

- Grossmann, A.; Morlet, J. Decomposition of Hardy functions into square integrable wavelets of constant shape. SIAM J. Math. Anal. 1984, 15, 723–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Y. Ondelettes et fonctions splines. In Séminaire Equations aux Dŕivés Partielles (Polytechnique) dit aussi "Séminaire Goulaouic-Schwartz"; Ecole Polytechnique: Palaiseau, France, 1986; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Daubechies, I. Orthonormal bases of compactly supported wavelets. Commun. Pure Appl. Math. 1988, 41, 909–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallat, S.G. A theory for multiresolution signal decomposition: The wavelet representation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1989, 11, 674–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Härdle, W.; Kerkyacharian, G.; Picard, D.; Tsybakov, A. Wavelets, Approximation and Statistical Application; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Tsybakov, A.B. Introduction à l’estimation non paramétrique. In Mathématiques et Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Vidakovic, B. Statistical Modeling by Wavelets; Institute of Statistics and Decision Science: Kolkata, India, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kerkyacharian, G.; Picard, D. Density estimation in Besov spaces. Stat. Probab. Lett. 1992, 13, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerkyacharian, G.; Picard, D. Density estimation by kernel and wavelet methods: Optimality of Besov spaces. Stat. Probab. Lett. 1993, 18, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadis, A.; Carmona, R. Multiresolution Analyses and Wavelets for Density Estimation; Technical Report; University of California at Irvine: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, G.G. Approximation of Delta function by wavelets. J. Approx. Theory 1992, 71, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, G.G. Wavelets and Others Orthogonal Systems with Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Donoho, D.L.; Johnstone, I.M. Ideal spatial adaptation by wavelet shrinkage. Biometrika 1994, 81, 425–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoho, D.L.; Johnstone, I.M.; Kerkyacharian, G.; Picard, D. Density estimation by wavelet thresholding. Ann. Stat. 1996, 24, 508–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoho, D.L.; Johnstone, I.M. Minimax risk over lp-balls for lp-error. Probab. Theory Relat. Fields 1994, 99, 277–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeson, G.P. Wavelet function estimation using cross-validation. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1996, 58, 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidakovic, B. Non linear wavelet shrinkage with Bayes rules and Bayes factors. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1994, 93, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjileontiadis, L.J.; Panas, S.M. Separation of discontinuous adventitious sounds from vesicular sounds using a wavelet-based filter. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 1997, 44, 1269–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranta, R.; Heinrich, C.; Louis-Dorr, V.; Wolf, D. Interpretation and improvement of an iterative wavelet-based denoising method. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2003, 10, 239–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklar, M. Fonctions de répartition à n dimensions et leurs marges. Annales de l’ISUP 1959, 8, 229–231. [Google Scholar]

- Joe, H. Multivariate Models and Multivariate Dependence Concepts; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Nelsen, R.B. An Introduction to Copulas; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Gemany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Genest, C.; Masiello, E.; Tribouley, K. Estimating copula densities through wavelets. Insur. Math. Econ. 2009, 44, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autin, F.; Pennec, F.L.; Tribouley, K. Thresholding methods to estimate copula density. J. Multivar. Anal. 2010, 101, 200–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatrabgoun, O.; Parham, G.; Chinipardaz, R. A Legendre multiwavelets approach to copula density estimation. Stat. Pap. 2017, 58, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provost, S.B. Nonparametric copula density estimation methodologies. Mathematics 2024, 12, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falhi, F.H.; Hmood, M.Y. Estimation of Copula Density Using the Wavelet Transform. Baghdad Sci. J. 2024, 21, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pensky, M.; Canditiis, D.D. Minimax estimation with thresholding and its application to wavelet analysis. Stat. Med. 2025, 44, 1234–1250. [Google Scholar]

- Bouezmarni, T.; Rombouts, J.V.; Taamouti, A. Asymptotic properties of the Bernstein density copula estimator for α-mixing data. J. Multivar. Anal. 2010, 101, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesneau, C. On the adaptive wavelet estimation of a multidimensional regression function under alpha-mixing dependence:beyond the standard assumptions on the noise. Comment. Math. Univ. Carol. 2013, 54, 527–556. [Google Scholar]

- Coifman, R.; Wickerhauser, M.V. Adapted waveform “de-noising” for medical signals and images. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Mag. 1995, 14, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydov, Y.A. The invariance principle for stationary processes. Theory Probab. Its Appl. 1970, 15, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebscher, E. Strong convergence of sums of α-mixing random variables with applications to density estimation. Stoch. Process. Their Appl. 1996, 65, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).