Abstract

In order to characterize topological insulators it is customary to use representations of the electronic structure, such as the band structure, where the energy of electrons is represented as a function of their momenta. Topological insulators are then represented as those systems whose surface states have an odd number of crossings at the Fermi level, or, equivalently, as those systems where the spin and momentum is locked at the surface. The density of states, however, cannot in principle be used to distinguish if a material is a topological insulator because it integrates the momentum information for a given energy. In this article, we show that, despite that fact, the density of states of topological insulators show some distinctive characteristics that may even be used to predict if a certain material is of that type or not by using such quantity. We use a series of machine learning algorithms to classify first the density of states and predict then systems with similar densities of states that can lead to new topological materials. We find that, contrary to what would be expected, the densities of states of topological insulators have distinct features that allow to classify and identify these materials according to them. In particular, the DOS of topological insulators tends to exhibit sharper and more concentrated spectral features near the band edges, indicating a narrower distribution of bulk electronic states (spectral localization) rather than spatial localization of surface modes.

MSC:

68T20; 68T09

1. Introduction

Topological insulators (TIs) represent a novel class of quantum materials [1,2] that hold significant promise for next-generation electronic and spintronic devices [3,4]. These materials are characterized by conducting surface states that are spin-polarized and locked to the momentum of the charge carriers, resulting in robust spin-polarized currents that propagate along the surface with minimal dissipation and absence of back-scattering. The identification and characterization of topological insulators typically rely on the analysis of the band structure, which provides explicit information on the momentum and symmetry properties of electronic states.

In contrast, the density of states (DOS) offers no momentum-resolved information, as it corresponds to an energy-dependent quantity obtained by integrating over all -points in the Brillouin zone. As such, the DOS alone does not directly capture the topological nature of materials and is generally considered unsuitable for determining whether a given compound is a topological insulator [5]. Consequently, conventional analysis based solely on the DOS has been limited in this context.

Nevertheless, the DOS has been widely studied using machine learning (ML) techniques in recent years. Various efforts have focused on extracting physical properties from the DOS [6], as well as on the classification and prediction of DOS profiles across diverse material classes [7,8]. Early studies explored the prediction of the DOS at the Fermi level [9], while subsequent work extended this to reconstruct the entire DOS curve [10]. These investigations demonstrated that ML algorithms can predict the shape and features of the DOS with a relatively high degree of accuracy—particularly for restricted families of elements or compounds with specific compositions [11]. However, generalization to broader material spaces remains a challenge, and further progress depends on the availability of larger, high-quality datasets and the development of more powerful learning models.

In this work, we explore how machine learning algorithms can be applied to data extracted from material databases to classify and predict whether a given compound behaves as a topological insulator, based on patterns in its DOS. Our results show that, despite the lack of explicit momentum information in the DOS, certain patterns and characteristics allow for distinguishing topological from non-topological materials with reasonable accuracy. This approach allows us then to uncover hidden relationships in complex materials data and support the discovery of new functional materials for future technologies.

Although these results are promising, it is essential to clarify the scope and limitations of using DOS-based descriptors, while the DOS does not encode momentum-resolved quantities—such as Berry curvature, parity eigenvalues, or other symmetry indicators—it may still display indirect statistical signatures of topological behavior. The machine-learning models do not infer topological invariants from the DOS itself; rather, they learn correlations between DOS patterns and material families in which strong spin–orbit coupling, band inversion, or narrow spectral features near the Fermi level are common.

The structure of the article is as follows: In Section 2, we describe the dataset used and the machine learning methods employed for classification and prediction. Section 3 presents the results, beginning with the classification performance and followed by DOS predictions for selected materials. In Section 4, we discuss the implications of our findings and assess the viability of using DOS-based representations for identifying topological insulators. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the conclusions and outlines directions for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Acquisition, Simulation and Preprocessing

To obtain information on the density of states (DOS) of materials, we used the AFLOWLIB materials database [12], one of the largest repositories of computationally investigated materials. Based on data from the ICSD (Inorganic Crystal Structure Database) [13], AFLOW employs the VASP code [14]—based on Density Functional Theory (DFT) [15,16]—to simulate various properties, including DOS, mechanical and electronic characteristics, for 60,392 materials in separate files. All simulations are performed using consistent parameters, allowing reliable comparisons between different compounds.

Due to the impracticality of downloading thousands of files manually, we implemented a Python-3-based routine to automatically access the HTML content of AFLOW’s web interface and retrieve the relevant DOS files. This process enables the classification and storage of materials ranging from metals to insulators, and from magnetic to non-magnetic systems.

Before performing dimensionality reduction, all DOS curves were interpolated onto a fixed grid of 1333 points in the window and normalized by their integrated spectral weight. This procedure removes trivial scale factors arising from different DOS magnitudes and ensures that the subsequent analysis focuses solely on the spectral shape. The PCA projection then compresses the normalized DOS curves into a reduced representation: PC1 captures overall intensity/width variations, PC2–PC3 encode curvature and asymmetry near the gap, and higher PCs describe finer spectral modulations. PCA reconstruction effectively smooths high-frequency numerical noise while preserving physically meaningful structure.

Each downloaded DOS file contains 5000 values uniformly distributed across the energy range . For our analysis, we selected only the values lying within . In magnetic materials, which present spin-resolved DOS for two channels, both spin components were summed to obtain the total DOS. Magnetic and non-magnetic systems were treated separately throughout the analysis.

To ensure reproducibility, the preprocessing pipeline consisted of the following: (i) interpolation onto the uniform grid; (ii) global normalization of each DOS curve by its integrated spectral weight; (iii) projection onto the PCA basis (retaining the first 25 components in the main experiments); and (iv) concatenation of PCA scores with the Fisher LDA projection and the Bravais lattice encoding to form the supervised feature vector. No derivative-based or hand-crafted DOS descriptors were included.

To complement AFLOW, we queried the Topological Materials Database [5] to obtain the topological classification of each material. This database contains information for 38,184 materials, including 6109 topological insulators.

The Topological Materials Database provides symmetry-based labels for time-reversal symmetric (AII) systems, reporting indicators. Accordingly, in this work, the term topological insulator refers specifically to -nontrivial AII insulators. The classification task is therefore binary (trivial vs. topological), and does not include Chern, crystalline or higher-order topological phases.

Finally, we applied the following filtering criteria:

- Only insulating materials were selected, identifiable by the absence of DOS values in a narrow region around the Fermi level.

- Materials with unknown topological classification were removed, since AFLOW contains more structures than the Topological Materials Database.

At the end of this process, we obtained a curated dataset containing both the DOS and the topological label of each material, ready for the machine-learning analyses described below.

2.2. Machine Learning Algorithms

The used algorithms can be divided into unsupervised and supervised learning methods. We used both unsupervised (k-means++) and supervised (kNN, Bayesian classifiers, Decision Trees, and SVMs) methods. Unsupervised clustering served as an exploratory tool for DOS structure, whereas supervised models leveraged the labeled dataset for topological classification.

2.2.1. k-Means++

The clusterization algorithm that we used is known as k-means++ [17], which is an enhanced initialization algorithm for the classic K-means clustering method. It improves the way the initial centroids are chosen, which helps avoid poor clustering results due to unlucky random initialization in standard K-means.

The goal of k-means++ is to spread out the initial centroids, reducing the likelihood of suboptimal solutions and improving convergence. Given a dataset , and a desired number of clusters , the algorithm k-means++ proceeds as follows:

- Choose the first centroid uniformly at random from the data points.

- For each remaining data point compute its distance to the nearest already chosen centroid.

- Choose the next centroid from the data points, where each point is chosen with probability proportional to .

- Iterate the previous steps until k centroids have been chosen.

- Proceed with standard K-means, using these k initial centroids.

This algorithm yields an optimal partitioning for a given k and will be employed to perform unsupervised clustering of the DOS curves from various insulating materials, both topological and non-topological.

2.2.2. PCA Model Reduction

Let us suppose that we have a disposal set of m DOS curves corresponding to m different materials, where , where s represents the number of points of each DOS curve.

The PCA model reduction [18], consists of finding an orthogonal basis set of the experimental covariance matrix

where

The matrix C is symmetric and therefore admits an orthogonal diagonalization of the following form:

The total variance in the DOS space is given by

Model reduction consists of finding the index q such as the cumulative energy function

where is a given percentage of the total variance. In summary, PCA seeks to obtain the q-dimensional subspace onto which the data (DOS curves) are projected while preserving of the observed variability.

The projection, of the curve onto the q-dimensional PCA subespace is given by

where are the q eigenvectors associated with the largest eigenvalues of the matrix C.

The reconstruction formula is

where is a smooth version of , i.e., PCA projection and reconstruction can be viewed as a high frequency filter of the data.

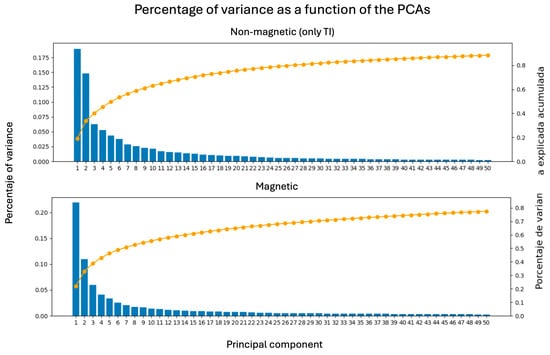

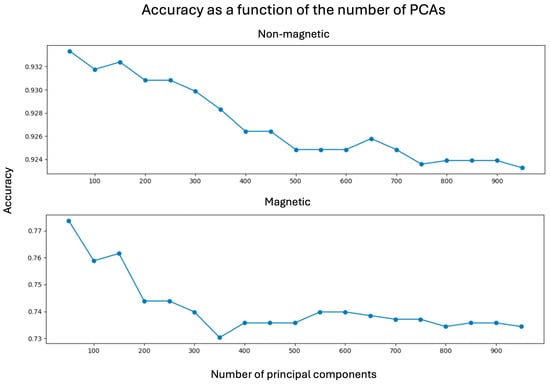

To justify the selection of the number of principal components, we evaluated both the cumulative explained variance and the resulting classification performance. As shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2, the first 20–30 PCs account for approximately 70–80% of the total DOS variance, and the model accuracy reaches a stable plateau beyond this range. Accordingly, we restrict the analysis to this stable region to avoid under-compression (loss of relevant DOS structure) and over-compression (inclusion of noise-dominated higher components). This choice yields a compact yet physically meaningful representation of the DOS near the Fermi level. Furthermore, we confirm that the retained PCs preserve class-relevant spectral information by reconstructing median DOS curves (Figure 2), which serves as our criterion for assessing the interpretability of the reduced space.

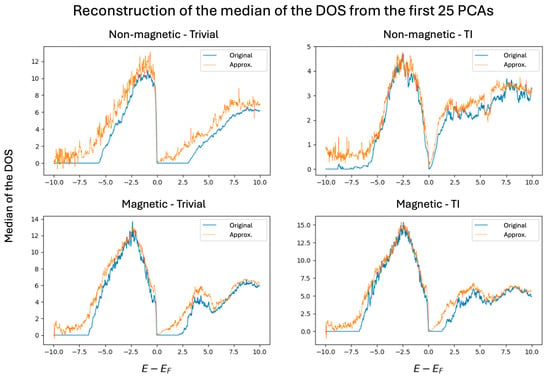

It is important to note that PCA components encode interpretable spectral patterns. The leading PCs reflect broad DOS intensity variations and the relative sharpness of features near the Fermi energy, while higher PCs describe finer spectral modulations. As shown in Figure 3, reconstructions using the retained PCs accurately reproduce the median DOS curves of both trivial and topological materials, confirming that the reduced space preserves class-relevant information.

2.2.3. Fisher Linear Discriminant Analysis (FLDA)

FLDA is a technique for projecting high-dimensional data onto a one-dimensional subspace in such a way that the separation between two classes is maximized [19].

Suppose we have a dataset consisting of two classes, and , each characterized by its mean vector and , and corresponding scatter matrices, and . The goal is to find the optimal projection vector that maximizes the ratio of between-class variance to within-class variance:

Here, the within-class scatter matrix is defined as follows:

and the between-class scatter matrix is given by

The vector that maximizes the criterion is obtained analytically as follows:

Each sample is then projected onto the subspace spanned by :

where is the coordinate of in . In the binary classification case, the projection yields a scalar value, enabling classification by applying a threshold in the one-dimensional space. In our approach, this scalar feature will be incorporated into the PCA coordinates of each sample in the dataset.

The PCA scores resulting from the PCA model reduction were concatenated with LDA and Bravais lattice to form the supervised feature matrix.

2.2.4. K-Nearest Neighbors (K-NN)

The k-nearest neighbors (K-NN) algorithm is a non-parametric, instance-based method used for classification and regression [20]. The input consists of a dataset of the type: with . Given a query point , the algorithm identifies the set of the k closest training points in the feature space:

where p is the norm used, typically the Euclidean.

In classification, the predicted label is the majority class among the k neighbors:

where is the set of possible classes, and is the indicator function.

In regression, the predicted value is given by the average of the target values of the neighbors:

K-NN is sensitive to the local structure of the data and does not assume any underlying distribution. However, it is computationally intensive at inference time and may suffer from the curse of dimensionality. In our case, it is used in combination with dimensionality reduction via PCA.

2.2.5. Bayesian Classifier

A Bayesian classifier is a probabilistic model used in supervised learning that applies Bayes’ theorem to assign a data point characterized by its feature vector to the most probable class . The classification is based on computing the posterior probability of each class given the input data:

where is the posterior probability of class given the input , is the likelihood of observing given class , is the prior probability of class , is the marginal probability of the input.

Since is constant across all classes, the classification rule becomes:

The Naive Bayes classifier, which assumes conditional independence between the features of the input vector , given the class:

This simplification makes the model computationally efficient, even in high-dimensional spaces [21].

2.2.6. Decision Tree Classifier

A Decision Tree is a supervised learning algorithm used for both classification and regression tasks. It represents decisions and their possible consequences in a tree-like structure, where internal nodes correspond to feature-based tests, branches to outcomes of those tests, and leaf nodes to predicted class labels. At each node, the algorithm selects the feature that best splits the data according to a purity criterion. Common impurity measures include entropy and Gini impurity , defined as

and

where is the proportion of instances belonging to class i, and n is the total number of classes [22].

Once the tree is constructed, a new instance is classified by traversing the tree from the root to a leaf node, following the decision rules at each node based on the instance’s feature values.

2.2.7. Support Vector Machines (SVMs)

SVMs are supervised learning models used for classification and regression tasks. The main idea behind SVMs is to find the hyperplane that best separates the data into different classes while maximizing the margin between them.

Given a training dataset of pairs , where is a feature vector and is the class label, the goal is to find a weight vector and a bias b such that the following condition holds for all data points:

The model is trained by solving the following optimization problem:

subject to the constraint above. This finds the hyperplane with the largest margin separating both classes in .

In real-world applications, some misclassifications may be allowed using slack variables and a regularization parameter . This leads to the soft-margin SVM formulation:

subject to

To handle nonlinear classification, SVMs can be extended using the kernel trick, where the dot product is replaced by a kernel function , such as the radial basis function (RBF) or polynomial kernel [23].

Figure 1.

Percentage of variance and accumulated variance for the first 50 PCAs. Explained variance (bars) and cumulative explained variance (orange curve) for the first 50 principal components, shown separately for non-magnetic (top) and magnetic (bottom) TI materials. The plots highlight the rapid decay of individual component contributions and the number of components required to capture most of the dataset variance.

Figure 2.

Reconstruction of the plots of the median of the DOS. Accuracy of the classifier as a function of the number of principal components retained in the PCA projection, shown separately for non-magnetic (top) and magnetic (bottom) materials. In both cases, accuracy tends to decrease as more components are included, indicating that the most relevant information is concentrated in the leading components. PCA projection onto a suitably reduced space preserves the class-relevant structure of the DOS data.

Figure 3.

Accuracy for a kNN model as a function of the number of PCAs used to train it. Median DOS curves reconstructed from the first 25 principal components for non-magnetic and magnetic materials, separated into trivial and topological classes. The close agreement between the original and reconstructed curves demonstrates that a limited number of PCA components retain most of the DOS structure relevant for distinguishing the two classes.

3. Preliminary Analysis

3.1. Distribution of Materials by Topology

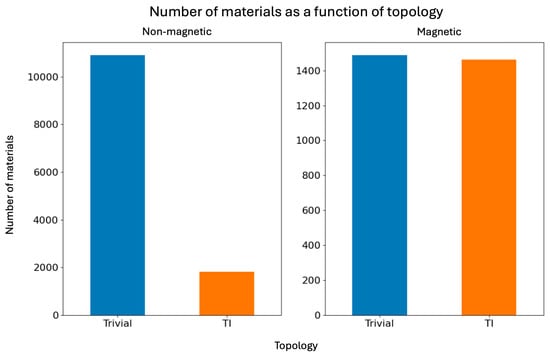

Figure 4 shows the distribution of materials in the dataset according to their topological classification—trivial or topological insulator—and their magnetic character. Most topological insulators are non-magnetic, consistent with the role of time-reversal symmetry in stabilizing topological phases. However, a significant number of magnetic topological insulators are also included, reflecting increased interest in these systems.

Figure 4.

Histogram of materials according to their topology. Histogram shows the number of trivial and topological insulator (TI) materials in the non-magnetic (left) and magnetic (right) subsets. Non-magnetic materials are overwhelmingly trivial, whereas magnetic materials display a more balanced distribution between trivial and topological phases.

The dataset is notably imbalanced in the non-magnetic group, where trivial insulators vastly outnumber topological ones. In contrast, magnetic materials are more evenly split between the two classes, indicating that magnetic ordering alone does not determine a material’s topological character. This highlights the need to analyze finer electronic structure features for reliable classification.

These class imbalances—particularly the large excess of trivial non-magnetic insulators—must be taken into account when training machine-learning models, as they can bias decision boundaries and inflate accuracy metrics if not treated carefully.

According to structural databases, the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) contains over 210,000 experimentally determined inorganic crystal structures [13]. Based on estimates from comprehensive materials surveys, approximately 5000 of these are magnetic compounds.

3.2. Distribution by Bravais Lattice

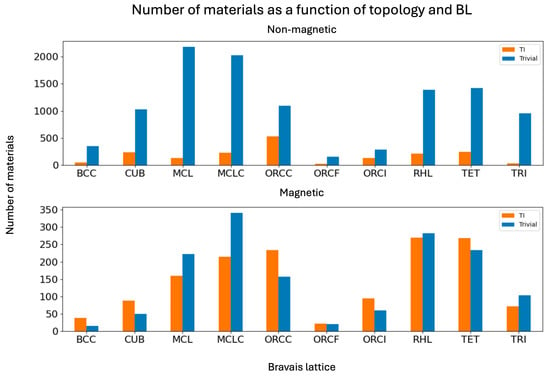

Figure 5 provides a detailed breakdown of the number of materials classified as trivial or topological insulators for each Bravais lattice type, separated by a magnetic character.

Figure 5.

Histogram of materials according to their topology and Bravais lattice. Histogram of materials classified as trivial or topological insulators (TIs) as a function of Bravais lattice type. Results are presented for non-magnetic materials (top panel) and magnetic materials (bottom panel), highlighting substantial differences in the prevalence of topological phases across lattice symmetries.

The distributions vary significantly across lattice types. Among non-magnetic materials, trivial insulators dominate in all lattices, although the relative proportions differ. Topological insulators are most frequently found in orthorhombic C-centered (ORCC), cubic (CUB), monoclinic C-centered (MCLC), tetragonal (TET), and rhombohedral (RHL) lattices. For instance, in the ORCC lattice, the number of topological insulators is roughly half that of trivial ones, while in the trigonal (TRI) lattice, they are nearly absent.

In magnetic materials, the influence of lattice symmetry is even more pronounced. Topological phases are prevalent in TET, RHL, ORCC, MCLC, and monoclinic primitive (MCL) lattices. Some lattices, such as CUB, ORCC, ORCI, and TET, exhibit the majority of topological insulators, whereas others, like MCL and MCLC, are dominated by trivial ones.

These patterns reveal a clear link between Bravais lattice type, magnetism, and topological behavior. Therefore, lattice symmetry is considered a relevant descriptor and is included among the input features for the machine learning models.

To assess whether the classifiers merely memorize chemical or structural families, we performed two complementary checks. First, we inspected the distribution of known chemical families (elemental composition clusters) in PCA space and found no one-to-one mapping between a single family and the topological label: topological materials populate a compact region but overlap partially with several chemical groups. Second, misclassified samples do not aggregate by chemical family; instead, they concentrate near the PCA-based decision boundaries and correspond to DOS profiles with intermediate or noisy spectral features. These observations indicate that the models rely primarily on DOS spectral patterns rather than simple memorization of composition or lattice type. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that using composition as an explicit feature could improve performance and should be explored in future work.

3.3. Median DOS

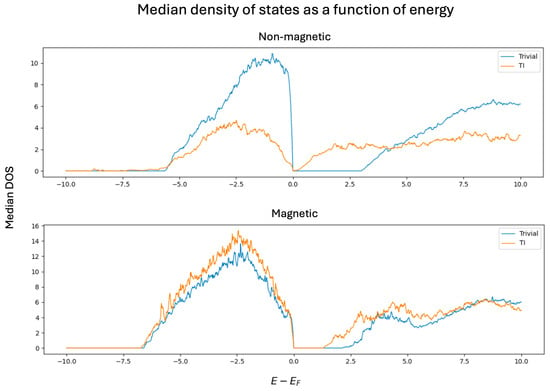

The first step involves classifying the density of states (DOS) as corresponding to either topological or trivial insulators.

Figure 6 presents the median density of states (DOS) for topological and trivial insulators, classified according to their magnetic status. For non-magnetic materials, trivial insulators exhibit a significantly higher DOS—approximately 2.5 times greater—just below the Fermi level, indicating a higher concentration of occupied electronic states near the valence band edge. Above the Fermi level, trivial insulators display a well-defined band gap of approximately 2.6 energy units (), while topological insulators exhibit a smoother transition characterized by a pronounced valley rather than a sharp gap, suggesting the presence of extended states or band inversion near the conduction band edge. Overall, the average DOS remains consistently higher for trivial insulators, possibly reflecting broader band dispersion or the lack of symmetry-protected states in the gap region.

Figure 6.

Graphical representation of the median DOS for non-topological and topological insulators. Median density of states (DOS) versus energy for trivial and topological insulator (TI) samples in the non-magnetic (top) and magnetic (bottom) subsets. The curves reveal characteristic differences near the Fermi level, reflecting the distinct electronic structure signatures associated with topological phases.

In contrast, for magnetic materials, the average DOS curves for topological and trivial insulators are qualitatively similar in shape. However, the DOS of topological insulators remains slightly higher both below and above the Fermi level. Furthermore, topological insulators in this class exhibit a smaller energy gap—approximately energy units compared to the energy units observed in their trivial counterparts. This reduction in the gap size may be attributed to the breaking of time-reversal symmetry induced by magnetic ordering, which modifies the band topology and can partially close or reshape the gap. Additionally, magnetic interactions can influence spin–orbit coupling effects, potentially reducing the effectiveness of the mechanisms that stabilize large band gaps in non-magnetic topological phases.

A preliminary conclusion is that distinguishing between magnetic topological and trivial insulators is considerably more challenging than in the non-magnetic case, due to the high similarity in their average density of state (DOS) profiles. However, the purpose of applying advanced machine learning techniques—beyond simple statistical comparisons—is to extract latent features and capture non-obvious patterns embedded in the DOS curves. These representations may reveal subtle but systematic differences that can improve the classification performance and provide physical insights into the underlying mechanisms distinguishing the two classes.

We stress that these observations do not imply that the DOS directly encodes topological invariants. Rather, band inversion, strong spin–orbit coupling and reduced dispersion—conditions that frequently coexist with non-trivial topology in real materials—produce reproducible spectral fingerprints in the energy domain (e.g., sharper edge features, reduced bandwidth, characteristic asymmetries). The machine-learning models exploit these indirect, statistical correlations as proxies for topology: they recognize DOS patterns that commonly appear in material families where topology occurs, without accessing momentum-resolved geometric quantities.

The DOS lacks momentum-resolved information and therefore cannot encode Berry curvature, parity eigenvalues, or other symmetry indicators, which are required to compute formal topological invariants. Our approach does not attempt to infer such invariants from DOS data; instead, it learns empirical surrogates that correlate with known topological phases.

The next step is to relate the classification to physical properties that may explain the trends identified by the average DOS curves. A key observation is that the narrower spread of states in topological insulators (TIs) suggests greater electronic localization.

This statement refers specifically to bulk electronic localization (i.e., narrower band widths and more concentrated spectral weight), not to the spatial extent of topological surface states. Topological surface states remain extended and conductive; our localization remark addresses bulk spectral localization tendencies that empirically correlate with families of materials exhibiting band inversion and strong SOC, which in turn favor non-trivial topology.

This points to bonding types that favor localized bulk states—often associated with insulating behavior—while allowing conductive surface states, which is a hallmark of topological insulators [1,2]. Such localization is typically linked to ionic bonding, where electrons are concentrated around atoms, in contrast to covalent bonds that promote delocalization. Materials with strong ionic character often behave as insulators or semiconductors in the bulk, but can host conductive surface states, especially when surface reconstructions or dangling bonds are present [24]. However, purely ionic materials may lack the necessary surface states if no dangling bonds are formed, meaning that a partial covalent character is also important [25].

Therefore, while ionic bonding plays a crucial role in enabling topological surface states, it is not sufficient on its own. This insight helps narrow down the types of materials likely to exhibit topological insulating behavior, even if a complete topological characterization still requires an analysis of band structure, such as the presence of an odd number of surface band crossings [26,27]. This analysis provides valuable information on the type of materials that have potential to behave as TI.

4. Discussion

Through the analysis of a comprehensive materials database, we identified topological insulators (TIs) based on criteria established by our classification models. This approach enabled not only the confirmation of known trivial insulators but also the prediction of new candidate TIs belonging to the same topological class as those in the training database, namely conventional three-dimensional topological insulators of the AII symmetry class (2D/3D TIs), which preserve time-reversal symmetry and exhibit a nontrivial invariant.

Accordingly, the present models perform a binary classification (trivial vs. nontrivial) and do not attempt to distinguish other topological categories such as Chern insulators, crystalline topological phases, or higher-order topological insulators.

Comparisons between the predicted and previously reported TIs revealed a strong agreement, confirming the reliability of the density of states (DOS) as a meaningful descriptor, despite its lack of explicit momentum dependence.

This agreement does not imply that the DOS intrinsically encodes topological invariants; instead, it reflects robust empirical correlations between DOS spectral patterns and material families in which non-trivial topology frequently arises.

To clarify the relationship between the model outputs and the materials represented in the dataset, we examined which chemical and structural families contribute most significantly to the separability observed in the DOS. Within the non-magnetic subset, the majority of topological insulators identified by the model correspond to heavy-element compounds with strong spin–orbit coupling (e.g., Bi-, Sb-, and Te-based systems), whereas the trivial class is dominated by lighter, wide-gap oxides and silicates. This distinction, which is not encoded directly in the input features, arises naturally from the DOS-based classification and reinforces the physical plausibility of the learned patterns.

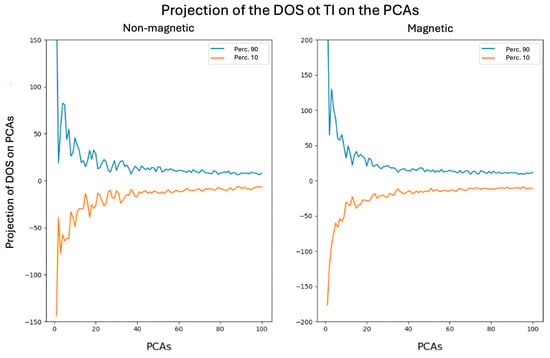

An analysis of the DOS-based classification results shows that the models consistently associate specific spectral patterns with topological insulating behavior. These patterns are clearly visible in Figure 1, Figure 6, and Figure 7, and they do not depend on assumptions about bonding or chemical composition. In particular, the median DOS curves (Figure 6) reveal that topological materials exhibit sharper and more concentrated features near the Fermi level, whereas trivial insulators display broader and more diffuse DOS profiles.

Figure 7.

Percentiles 10 and 90 of the projections of the DOS of the TI on the PCA base. Projections of the DOS of topological insulators onto the PCA basis, represented by the 10th and 90th percentile curves for the non-magnetic (left) and magnetic (right) datasets. The rapid decay and subsequent stabilization of the coefficients illustrate that most DOS variability is concentrated in the leading PCA components. These percentile envelopes define a bounded TI region in PCA space that can be used to constrain the search for new candidates and to generate synthetic DOS exemplars for screening.

It is important to emphasize that this localization refers exclusively to bulk spectral localization—i.e., narrower effective bandwidths and concentrated DOS features near the gap. It does not concern the topological surface states, which remain metallic and extended. This distinction resolves the apparent contradiction between sharper bulk features and the delocalized nature of surface modes in topological insulators. This provides direct evidence that the classifiers recognize DOS signatures linked to localized electronic states, in full agreement with the PCA and LDA projections used as inputs.

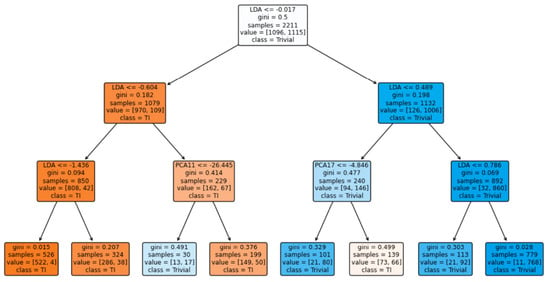

In this framework, PCA provides not only dimensionality reduction but also a clear interpretation of the spectral features driving classification. The leading components capture variations in DOS peak sharpness, band-edge curvature, and the distribution of spectral weight near the Fermi level. The plateau in accuracy observed as the number of retained PCs increases (Figure 2) indicates that the dominant signatures of topological behavior are concentrated in the first few modes, while higher PCs mostly encode noise or minor variations irrelevant to classification. This interpretation is independently supported by the decision-tree model (Figure 8), whose first branches rely primarily on LDA and PCA components associated with DOS sharpness and curvature. The compact, stable envelopes formed by the TI projections over the first 20 PCs (Figure 7) further confirm that the reduced DOS representation contains structured, class-relevant information.

Figure 8.

Decision tree built to predict the topology of the magnetic materials. Decision tree is used to classify magnetic materials into trivial and topological insulators. Each node displays the splitting criterion (LDA or PCA coordinate), Gini impurity, sample count, class distribution, and predicted class, illustrating the hierarchical decision process learned from the DOS-based descriptors.

The performance of the classification models reinforces the physical consistency of these findings. High accuracy and balanced precision–recall values indicate that the learned decision boundaries are not tied to specific chemical families but instead capture transferable DOS patterns. Misclassifications cluster near the PCA-defined decision boundaries, where materials exhibit intermediate properties. In magnetic systems, false negatives typically correspond to compounds with weak magnetization or nearly compensated spin channels, producing DOS profiles similar to non-magnetic insulators. Conversely, false positives tend to appear in narrow-gap compounds with pronounced orbital localization but lacking the band inversion required for non-trivial topology. These systematic trends confirm that errors arise from physically interpretable borderline cases rather than random noise.

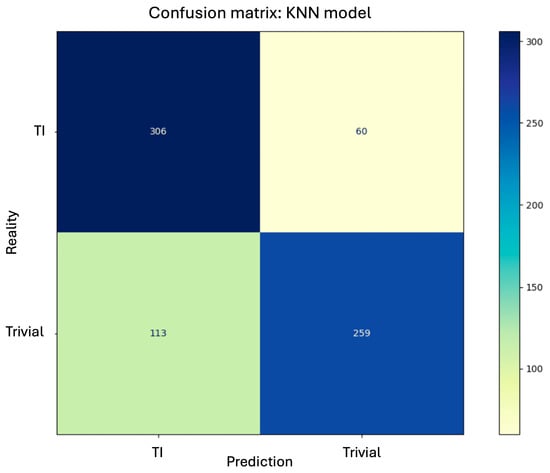

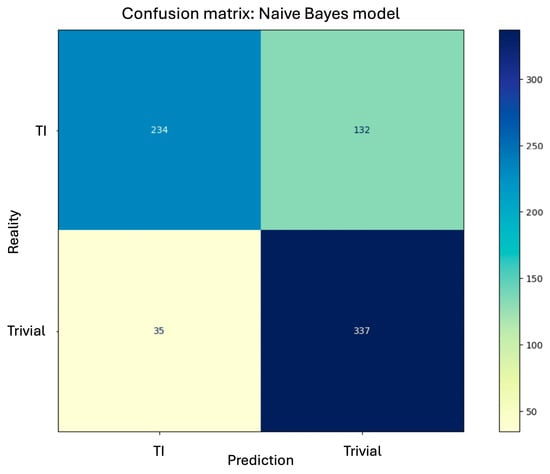

Figure 9 and Figure 10 illustrate that both classifiers correctly identify most topological and trivial materials, while still producing a moderate number of false positives and false negatives, reflecting the intrinsic difficulty of distinguishing borderline cases.

Figure 9.

Confusion matrix for the kNN model in the test. Confusion matrix for the kNN model evaluated on the test set. The classifier correctly identifies most TI and trivial materials, with 306 true positives and 259 true negatives, while 60 TIs are misclassified as trivial and 113 trivial materials are misclassified as TIs.

Figure 10.

Confusion matrix for the Bayesian classifierl in the test. Confusion matrix for the Naive Bayes model evaluated on the test data. The classifier correctly identifies 234 TI materials and 337 trivial materials, while misclassifying 132 TIs as trivial and 35 trivial materials as TIs.

Taken together, the successive stages of the methodology—median DOS inspection, PCA projection, LDA separation and supervised classification—provide complementary levels of physical interpretation. Median DOS curves reveal systematic differences in localization and gap width; PCA isolates the dominant spectral modes differentiating heavy-element, inversion-prone materials from conventional insulators; percentile envelopes delineate the admissible DOS shapes for TI candidates; and classifier outputs identify which material families are consistently or ambiguously classified. This layered structure produces a coherent mapping between DOS features and topological behavior.

Notably, a subset of ceramic compounds, typically characterized by insulating behavior dominated by ionic and partially covalent bonding, was also classified as topological. These materials, although chemically and structurally diverse, share macroscopic properties such as high hardness and electrical resistivity. This suggests that some bulk characteristics—independent of detailed composition—may correlate with non-trivial topological phases. Such findings highlight the capability of machine learning not only to reproduce established knowledge but also to uncover previously unrecognized physical correlations beyond the DOS itself, pointing toward new descriptors for future exploration. For instance, the observed localization tendencies in TIs could correlate with the band-gap magnitude or the material’s sensitivity to external perturbations.

The identification of several ceramic compounds as topological results directly from the same DOS patterns, while ceramics are often dominated by ionic or mixed ionic–covalent bonding, which produces flatter bands and narrower DOS peaks, the model does not explicitly include bonding information. Instead, these materials were classified as topological because their DOS curves fall within the compact TI envelopes in PCA space (Figure 7) and exhibit the spectral sharpness highlighted by the decision-tree analysis (Figure 8). It is important to clarify that no causal link is implied between bonding type and topology; rather, the observed correlation arises because some ceramics share DOS characteristics with known TIs.

Cross-referencing model predictions with chemical composition further reveals that ceramic compounds identified as topological generally contain elements of intermediate to high atomic number and exhibit mixed ionic–covalent bonding. This combination produces partially localized states, moderate orbital hybridization, and a characteristic narrowing of the DOS near the band edges, which leads to distinct clustering in PCA space compared to fully trivial ceramics. In contrast, compounds with broad and featureless DOS profiles—typical of strongly covalent systems with highly delocalized states—are consistently classified as trivial. This clear statistical separation, encoded through PCA and LDA projections sensitive to DOS peak sharpness, curvature, and asymmetry near the Fermi level, enables efficient discrimination without invoking explicit chemical assumptions. Projecting materials onto the first PCA coordinates further illustrates this trend: trivial covalent semiconductors (e.g., Si, Ge, and light binaries) cluster tightly in regions associated with broad, delocalized DOS profiles, whereas heavy-element chalcogenides and oxides occupy regions corresponding to sharper, localized DOS features. This geometrical separation explains the high accuracy achieved even by simple classifiers such as kNN or Decision Trees.

Overall, these results show that the machine-learning models identify topological materials through reproducible and quantifiable spectral signatures in the DOS and its reduced representations, rather than through implicit chemical knowledge or speculative assumptions. This strengthens the link between the statistical patterns observed in the dataset and the physical mechanisms underlying topological phases, and demonstrates that DOS-based representations—despite lacking momentum resolution—encode latent information that becomes predictive when processed through appropriate learning techniques.

The use of DOS-based machine-learning models therefore offers a powerful framework for rapid pre-screening of materials and shows that even descriptors lacking explicit momentum information can yield deep physical insights when analyzed statistically. This work also illustrates that complex quantum properties can be inferred from simpler fingerprints, broadening the scope of data-driven materials discovery.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that, contrary to conventional wisdom, the density of states (DOS) contains exploitable features that enable reliable classification of topological insulators (TIs) using machine learning (ML) techniques. Although the DOS integrates out momentum information, it exhibits latent patterns—such as sharper peaks and localized states—distinctive of TIs and systematically identifiable through data-driven methods.

By combining DOS profiles with structural descriptors such as the Bravais lattice, we developed a classification pipeline that reliably distinguishes trivial from topological insulators in both magnetic and non-magnetic materials. Dimensionality reduction using PCA and LDA efficiently captures the key variance and class separability in the DOS data, allowing classifiers—including SVMs, kNN, and Decision Trees—to achieve accuracies above 85–, even under class imbalance.

The present analysis clarifies how these descriptors relate to fundamental material properties: heavy-element compounds with strong spin–orbit coupling, mixed ionic–covalent ceramics, and narrow-gap chalcogenides systematically project into the same PCA region as known TIs, whereas wide-gap ionic insulators and covalent semiconductors occupy distinct spectral domains. This mapping provides a transparent connection between the statistical learning workflow, the actual electronic structure of materials, and their resulting topological behavior.

Localized electronic features, often linked to ionic or partially covalent bonding, correlate with topological behavior, particularly in ceramics and complex oxides, providing a basis for simplified screening strategies. Conversely, delocalized states with broad DOS features—characteristic of strong covalent bonding—are consistently excluded as TIs, confirming the utility of DOS-based descriptors for efficient filtering.

An additional contribution of this work is the construction of a constrained topological region in PCA space, obtained from the percentile envelopes of TI projections. This low-dimensional domain constitutes a practical tool for materials discovery: new DOS profiles can be projected into this region to rapidly identify promising candidates, and synthetic or interpolated DOS curves can be evaluated against it before undertaking computationally demanding band-structure calculations.

We further show that synthetic DOS profiles generated in reduced-dimensional spaces can be used to explore and propose new candidate materials, bridging data-driven prediction and exploratory discovery, and offering a scalable approach prior to computationally intensive ab initio validation.

This work also represents an initial step toward exploring additional topological phases within the ten Altland–Zirnbauer symmetry classes [27]. These include Quantum Hall systems, chiral (SSH-type) insulators, trivial spinless insulators, one-dimensional topological superconductors, spinless p-wave superconductors, time-reversal-invariant topological superconductors, higher-dimensional TIs, chiral systems with fermionic time-reversal symmetry, d-wave superconductors, and conventional time-reversal-invariant superconductors. Although it is unclear whether the DOS alone provides sufficient information for a unified classification—given that it integrates out symmetry-resolved and momentum-resolved quantities—the potential scientific payoff of attempting such an extension motivates future research in this direction.

We also acknowledge the limitations of our approach. The DOS does not encode symmetry eigenvalues or momentum-space information required for a full topological characterization. Furthermore, our models are trained exclusively on AII-class insulators, and generalization to other symmetry classes will require incorporating additional descriptors. Nonetheless, by demonstrating that coarse-grained spectral information already contains meaningful topological signals, this study lays a foundation for future extensions combining DOS with symmetry indicators, orbital-resolved fingerprints, or Wannier-based descriptors.

In summary, this work shows that machine learning applied to minimal input features—DOS and lattice symmetry—can reproduce known trends and uncover hidden patterns in topological materials. These results demonstrate that descriptors once considered insufficient, like the DOS, may hold untapped predictive power when paired with ML techniques. Future work may extend this framework through ensemble models, broader descriptor sets, or generative approaches for inverse design. Ultimately, this approach accelerates the discovery of quantum materials by enabling interpretable, lightweight, and physically grounded prediction models.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.F.-M., J.L.F.-M. and V.M.G.-S.; methodology, Z.F.-M., J.L.F.-M. and V.M.G.-S.; software, A.D.-N., J.L.F.-M. and V.M.G.-S.; validation, A.D.-N., Z.F.-M., J.L.F.-M. and V.M.G.-S.; formal analysis, A.D.-N., Z.F.-M., J.L.F.-M. and V.M.G.-S.; investigation, A.D.-N., Z.F.-M., J.L.F.-M. and V.M.G.-S.; resources, A.D.-N., J.L.F.-M. and V.M.G.-S.; data curation, A.D.-N., Z.F.-M., J.L.F.-M. and V.M.G.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D.-N., Z.F.-M., J.L.F.-M. and V.M.G.-S.; writing—review and editing, A.D.-N., Z.F.-M., J.L.F.-M. and V.M.G.-S.; supervision, A.D.-N., Z.F.-M., J.L.F.-M. and V.M.G.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. Public sharing is restricted due to the large size of the dataset and the absence of a suitable public repository for hosting it.

Acknowledgments

Part of this research has benefited from work carried out within the framework of the COST Action EuMINe-European Materials Informatics Network, CA22143, supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hasan, M.Z.; Kane, C.L. Colloquium: Topological insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010, 82, 3045–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.-L.; Zhang, S.C. Topological insulators and superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2011, 83, 1057–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.E. The birth of topological insulators. Nature 2010, 464, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesin, D.; MacDonald, A.H. Spintronics and pseudospintronics in graphene and topological insulators. Nat. Mater. 2012, 11, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergniory, M.G.; Elcoro, L.; Felser, C.; Regnault, N.; Bernevig, B.A.; Wang, Z. A complete catalogue of high-quality topological materials. Nature 2019, 566, 480–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jha, D.; Ward, L.; Paul, A.; King, W.E.; Wolverton, C.; Agrawal, A. ElemNet: Deep Learning the Chemistry of Materials From Only Elemental Composition. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodall, R.; Lee, A.A. Predicting materials properties without crystal structure: Deep representation learning from stoichiometry. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.; Marques, M.R.; Botti, S.; Marques, M.A. Recent advances and applications of machine learning in solid-state materials science. Npj Comput. Mater. 2019, 5, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, A.C.; Mishra, A.; Satsangi, S.; Vaishnav, S.; Pandey, A.A.; Sarkar, A.D.; Chakraborty, A.; Waghmare, U.V.; Joshi, A.S.; De, R. Machine-learning-assisted accurate band gap predictions of functionalized MXene. Chem. Mater. 2020, 32, 2954–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Grossman, J.C. Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Networks for an Accurate and Interpretable Prediction of Material Properties. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 120, 145301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez Pérez de Amézaga, C.; García-Suárez, V.M.; Fernández-Martínez, J.L. Classification and prediction of bulk densities of states and chemical attributes with machine learning techniques. Appl. Math. Comput. 2022, 412, 126587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtarolo, S.; Setyawan, W.; Hart, G.L.W.; Jahnatek, M.; Chepulskii, R.V.; Taylor, R.H.; Wang, S.; Xue, J.; Yang, K.; Levy, O.; et al. AFLOW: An automatic framework for high-throughput materials discovery. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2012, 58, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FIZ Karlsruhe. Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD). Available online: https://icsd.fiz-karlsruhe.de (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Kresse, G.; Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54, 11169–11186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohenberg, P.; Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous Electron Gas. Phys. Rev. 1964, 136, B864–B871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, W.; Sham, L.J. Self-Consistent Equations Including Exchange and Correlation Effects. Phys. Rev. 1965, 140, A1133–A1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, D.; Vassilvitskii, S. k-means++: The Advantages of Careful Seeding. In Proceedings of the Eighteenth Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms, New Orleans, LA, USA, 7–9 January 2007; Volume 1027. [Google Scholar]

- Hotelling, H. Analysis of a complex of statistical variables into principal components. J. Educ. Psychol. 1933, 24, 417–442. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, R.A. The use of multiple measurements in taxonomic problems. Ann. Eugen. 1936, 7, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, N.S. An Introduction to Kernel and Nearest-Neighbor Nonparametric Regression. Am. Stat. 1992, 46, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. The Optimality of Naive Bayes. AA 2004, 1, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan, J.R. Induction of decision trees. Mach. Learn. 1986, 1, 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-Vector Networks. Mach. Learn. 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Kane, C.L.; Mele, E.J. Surface states of topological insulators. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 86, 081303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrei Bernevig, B.; Hughes, T.L.; Zhang, S.C. Quantum Spin Hall Effect and Topological Phase Transition in HgTe Quantum Wells. Science 2006, 314, 1757–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Kane, C.L.; Mele, E.J. Topological insulators in three dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 98, 106803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnyder, A.P.; Ryu, S.; Furusaki, A.; Ludwig, A.W.W. Classification of Topological Insulators and Superconductors in Three Spatial Dimensions. Phys. Rev. B 2008, 78, 195125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).