Control Crisis in Financial Systems with Dynamic Complex Network Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework for Nonlinear Financial Networks

2.1. Complex Networks and Financial Interconnectedness

2.2. Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos in Economic Systems

2.3. Synchronization and Controllability in Complex Systems

2.4. Transition from Chaotic Behavior to Stabilization

- Network structure—coupling topology and connection weights;

- Pinned node selection—identification of nodes receiving control;

- Feedback design—continuous, impulsive, or adaptive schemes.

2.5. Gao–Ma Nonlinear Financial System

2.6. Extension to Financial Networks

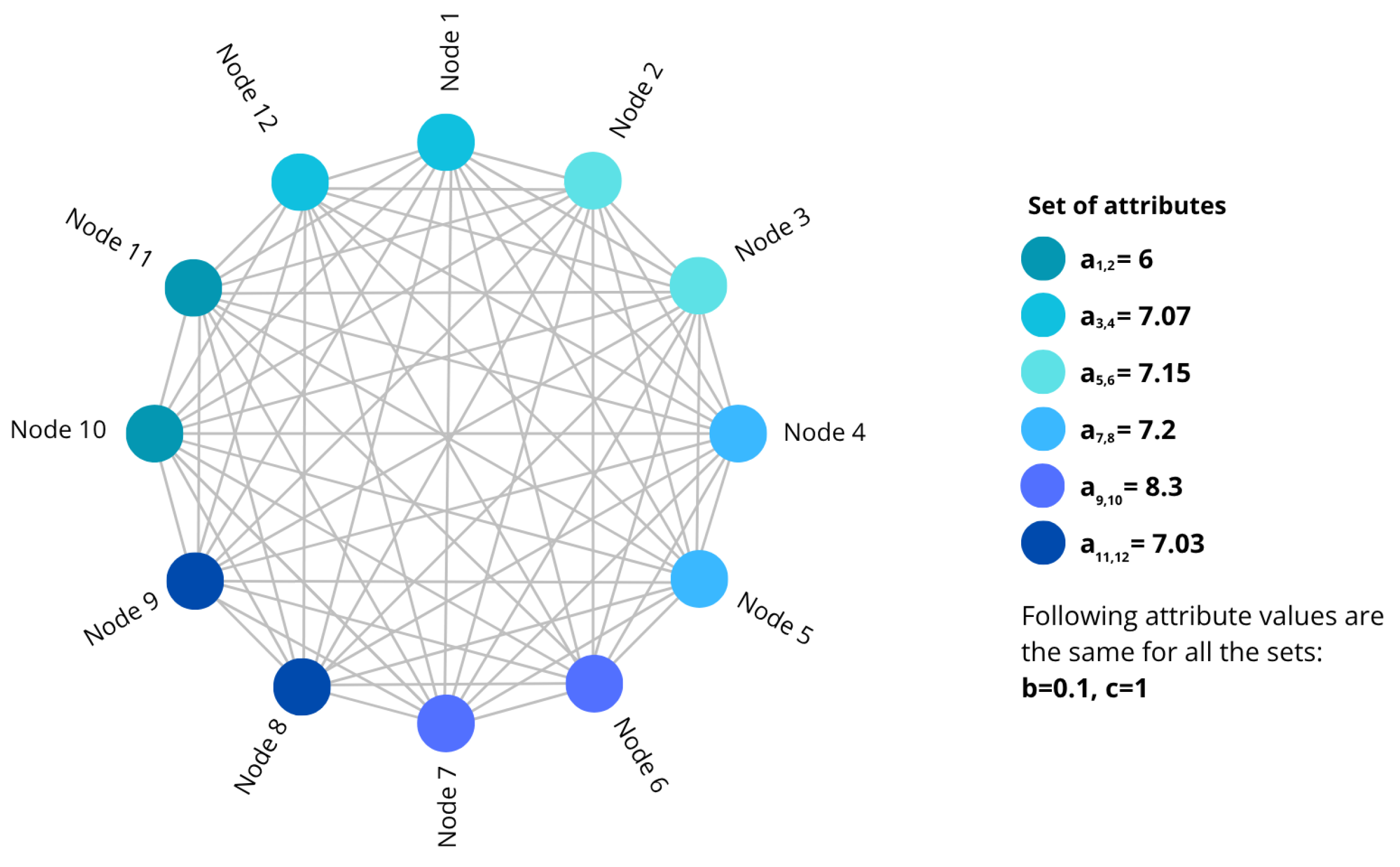

2.7. Simulation of Heterogeneous Macroeconomic Conditions

- Nodes 1–8: → stable or periodic economies.

- Nodes 9–10: → vulnerable economies.

- Nodes 11–12: → chaotic or crisis economies.

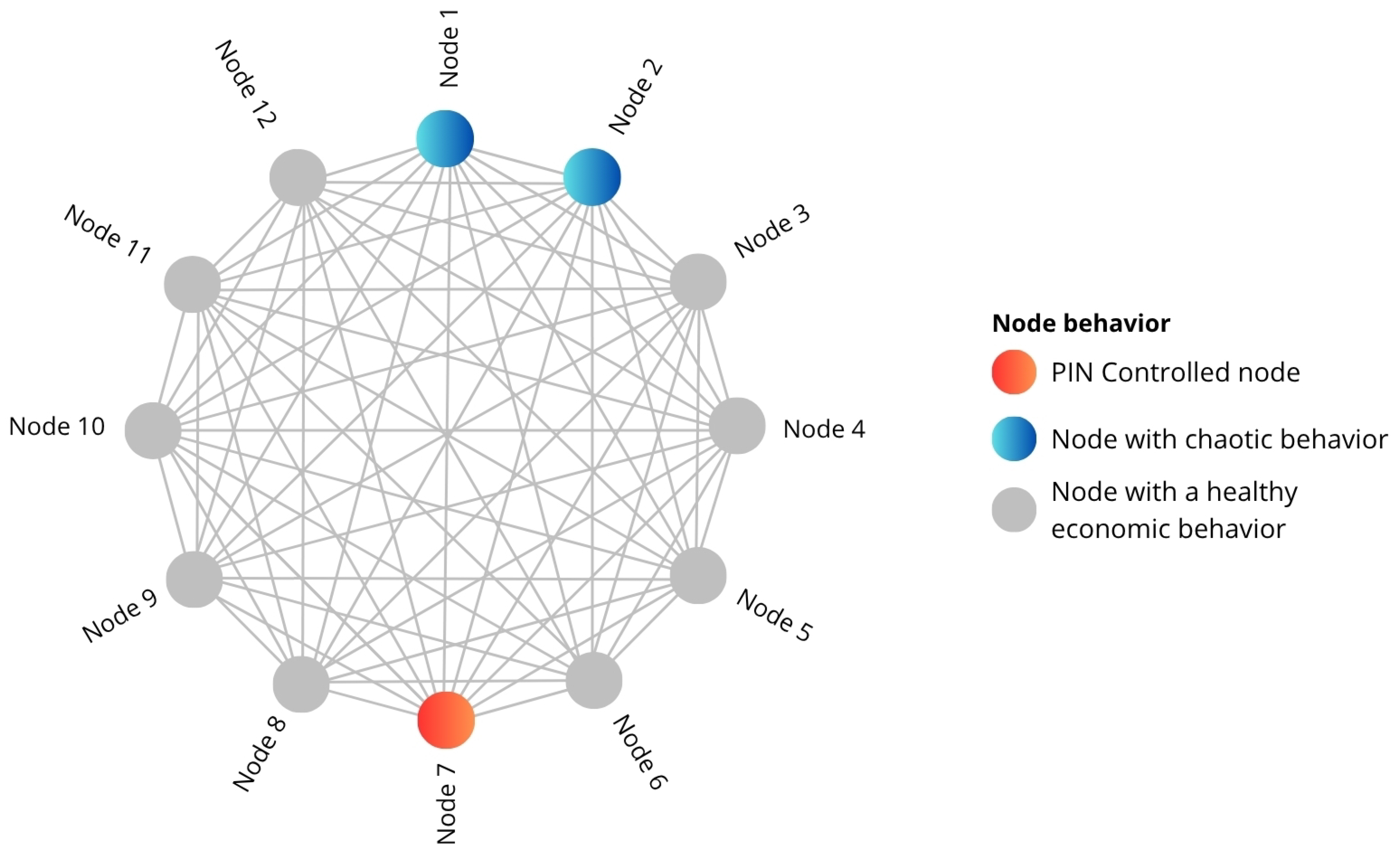

3. Pinning Control for Financial Systems Under Crisis

3.1. Fundamentals of Pinning Control

3.2. Optimal Selection of Pinning Nodes

- Initialization: generation of a random population of candidate control configurations.

- Evaluation: network dynamics are simulated to compute J and estimate Lyapunov exponents.

- Selection and crossover: individuals exhibiting lower error are recombined to explore improved control strategies.

- Convergence: the algorithm terminates once J stabilizes at a minimum or the largest Lyapunov exponent becomes negative (), indicating a synchronized regime.

3.3. Stability and Controllability Analysis

3.4. Methodology

3.4.1. Use of Synthetic Data

3.4.2. Choice of Network Topology

- Chaotic propagation under crisis conditions;

- Stabilization after applying pinning control;

- Reduction of global oscillations and Lyapunov exponents.

3.4.3. Dynamic Modeling of Financial System

Model Nomenclature

3.4.4. Extension to Dynamic Financial Networks

- denotes coupling intensity, expressing degree of financial correlation or mutual economic influence among nodes;

- the term quantifies differences in interest rates across connected nodes;

- weighted sum defined by matrix A determines how local fluctuations propagate across network.

3.4.5. Heterogeneous Financial Network Configuration

3.5. Pinning Control with Impulsive Actions

3.5.1. Mathematical Formulation

3.5.2. Economic Interpretation

3.5.3. Impulsive Control Energy

3.5.4. Advantages of Impulsive Approach

3.5.5. Control Performance Evaluation

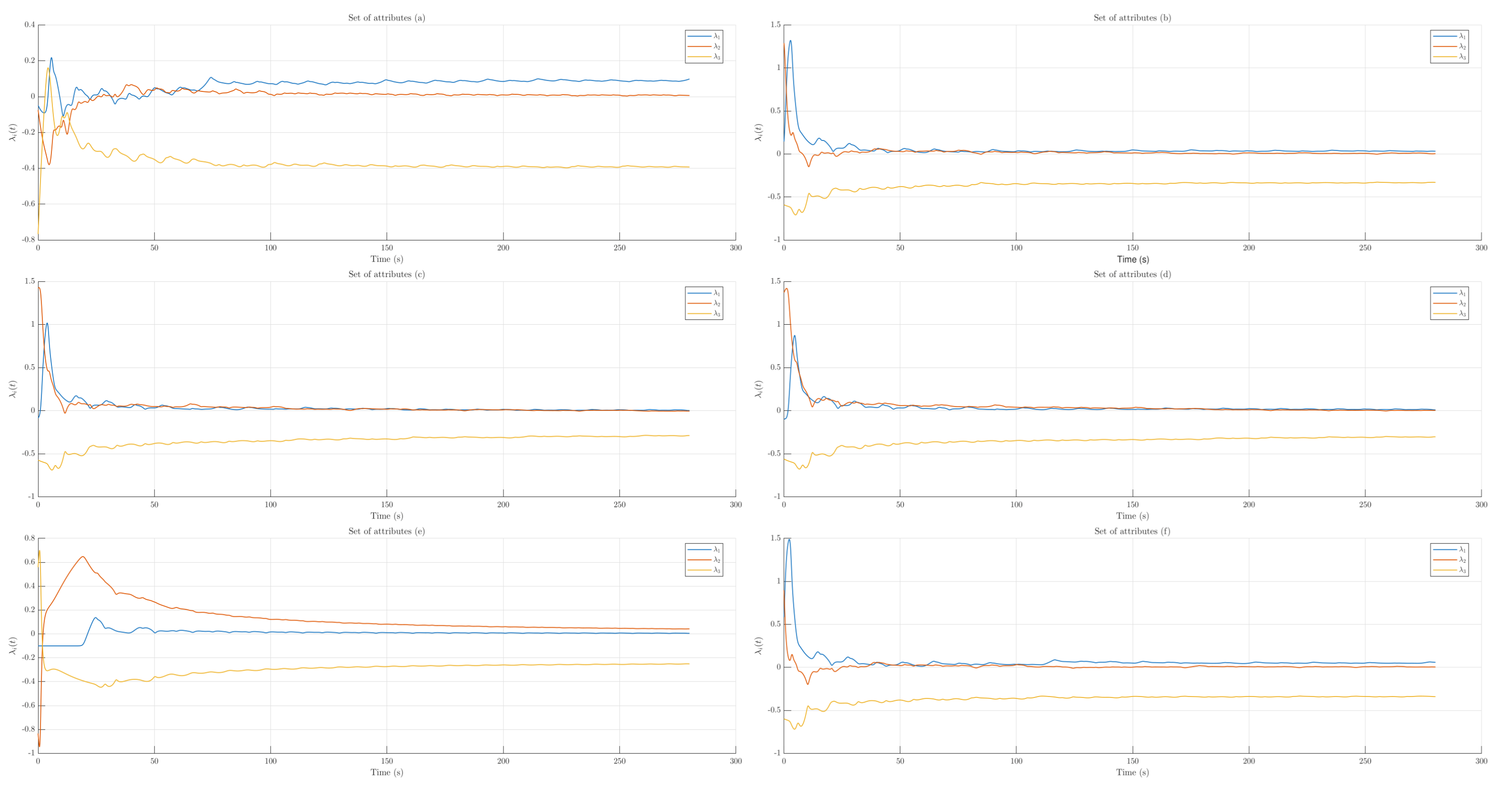

4. Results

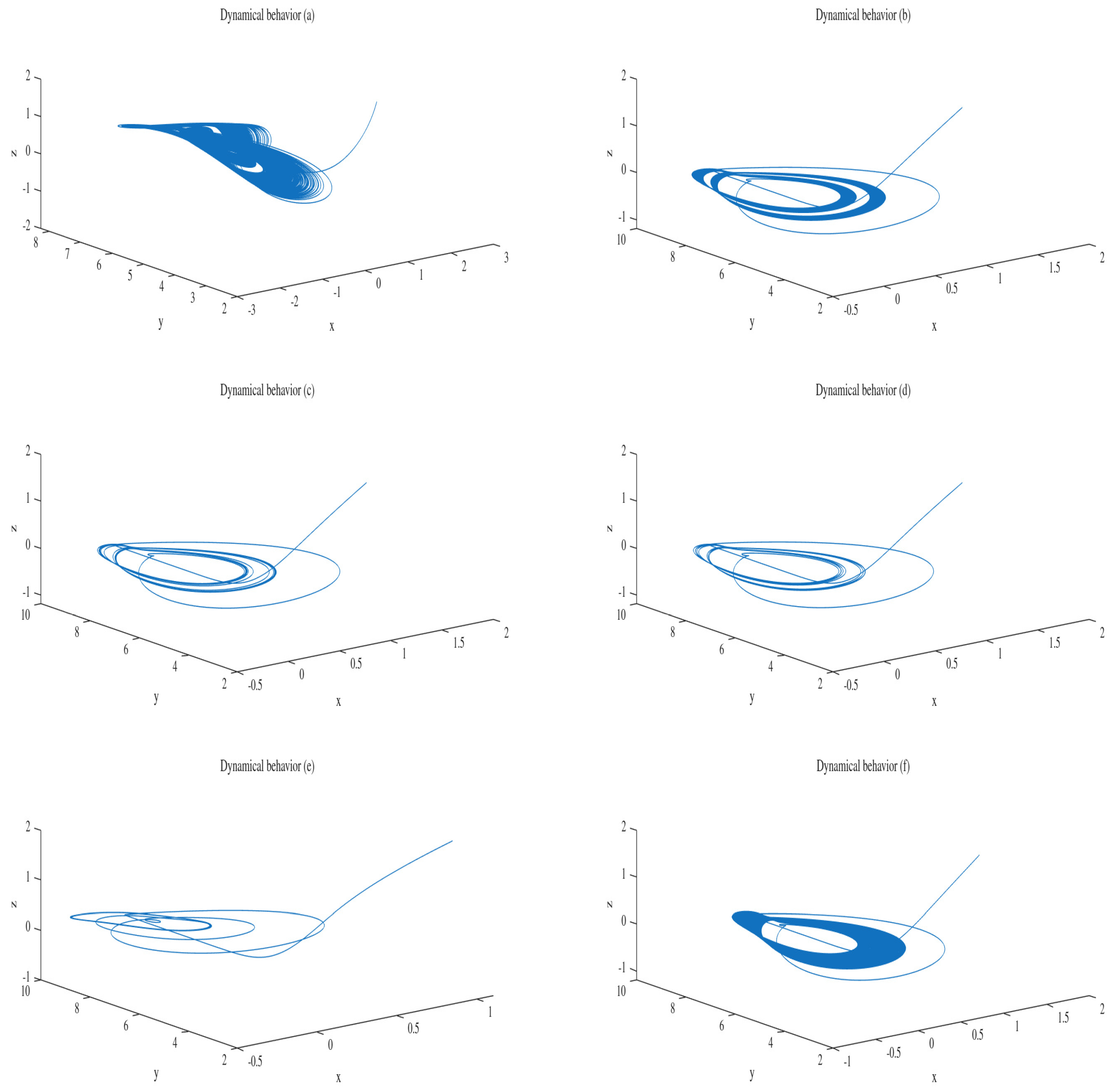

4.1. Dynamic Behavior of the Isolated System

4.2. Dynamic Behavior of the Controlled Financial Network

4.3. Scalability and Network Connectivity Analysis

4.4. Lyapunov Spectrum Analysis

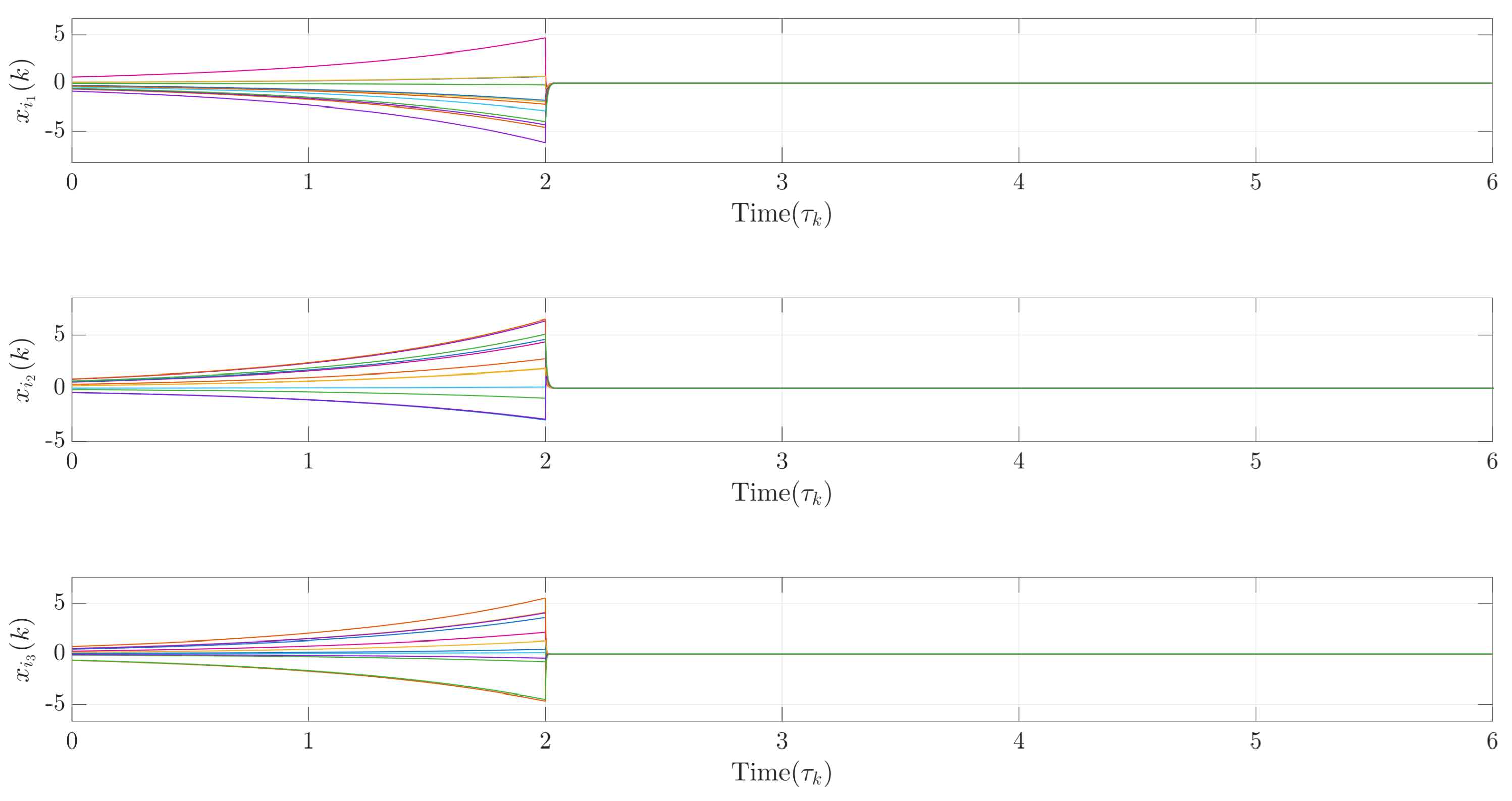

4.5. Results of Impulsive Pinning Control

4.6. Economic Interpretation

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Forum, W.E. The Global Risks Report 2025, 20th ed.; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ergüzel, O. Chaos Theory and Financial Markets: A Systematic Review of Crisis and Bubbles. Chaos Theory Appl. 2025, 7, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Miao, H.; Yang, X.; Cao, J.; Yang, H. Cascading failure, financial network and systemic risk. N. Am. J. Econ. Financ. 2025, 80, 102505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Ma, J. Chaos and Hopf Bifurcation of a Finance System. Nonlinear Dyn. 2009, 58, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battiston, S.; Farmer, J.; Flache, A.; Garlaschelli, D.; Haldane, A.; Heesterbeek, H.; Scheffer, M. Complexity Theory and Financial Regulation. Science 2016, 351, 818–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G. Pinning Control of Complex Dynamical Networks. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2022, 68, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, G. Pinning Control of Complex Networked Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Rossa, F.; Liuzza, D.; Lo Iudice, F.; De Lellis, P. Nonlinear Pinning Control of Stochastic Network Systems. Automatica 2023, 149, 110826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Yang, L.; Guan, C.; Leng, S. Reinforcement learning-based pinning control for synchronization suppression in complex networks. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orouskhani, Y.; Jalili, M.; Yu, X. Optimizing Dynamical Network Structure for Pinning Control. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, A.; Swift, J.; Swinney, H.; Vastano, J. Determining Lyapunov Exponents from a Time Series. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 1985, 16, 285–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Xin, Y.; Cao, J.; Li, P.; Liu, J. Selecting pinning nodes to control complex networked systems. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2018, 61, 1537–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fan, H.; Wang, X. Pinning Control of Cluster Synchronization in Regular Networks. Phys. Rev. Res. 2020, 2, 023084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tait, J. Synthetic Data in Investment Management; Technical report; CFA Institute: Singapore, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bharali, A.; Doley, A. On Small-World and Scale-Free Properties of Complex Network. Int. J. Math. Stat. Invent. (IJMSI) 2017, 5, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Li, L.; Ho, D.W.C. Synchronization Control of Complex Dynamical Networks: Invariant Pinning Impulsive Controller With Asynchronous Actuation. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2022, 9, 4255–4265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Lü, J.; Chen, S.; Yu, X. Pinning impulsive control algorithms for complex network. Chaos Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 2014, 24, 013141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Range of | Dynamic Regime | Financial Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| and | Chaotic | Deep crisis and financial instability |

| and | 2D Torus | Unstable adjustments preceding chaos |

| Periodic | Regular economic cycles | |

| Stable | Economy in equilibrium |

| Symbol | Description |

|---|---|

| Interest rate associated with financial node i | |

| Investment demand of node i | |

| Price index linked to node i | |

| Time derivatives of macroeconomic variables | |

| Saving parameter or economic sensitivity of node i | |

| b | Damping coefficient in investment demand |

| c | Rigidity coefficient of price level |

| N | Total number of financial nodes in the network |

| State vector of node i | |

| Reference or desired equilibrium vector | |

| Adjacency matrix describing connectivity among nodes | |

| Coupling or financial correlation intensity among nodes | |

| Global coupling gain of the system | |

| Control gain applied to node i (in pinning control scheme) | |

| T | Sampling period or interval between control impulses |

| Positive-definite matrices used in LMI conditions for impulsive stability | |

| Maximum Lyapunov exponent used to assess system stability | |

| J | Global mean-squared synchronization error (objective function in genetic algorithm) |

| Node(s) | Dynamic Regime | Economic Interpretation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1–2 | 6.00 | Chaotic | Economies in crisis |

| 3–4 | 7.07 | Transition (near-chaotic) | Early recovery phase |

| 5–6 | 7.15 | Quasi-periodic | Vulnerable economies |

| 7–8 | 7.20 | Periodic/Stable | Healthy economies |

| 9–10 | 8.30 | Stable/Robust | Well-regulated economies |

| 11–12 | 7.03 | Chaotic/Unstable | Economies entering crisis |

| Connectivity (%) | J (Mean-Squared Error) | (Control Energy) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 25% | 0.0307 | 9.264 | 97117 |

| 50% | 0.0300 | 9.324 | 98248 |

| 75% | 0.0302 | 9.330 | 95674 |

| 100% | 0.0268 | 10.534 | 95461 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Venegas, H.G.; Ibarra, A.; Gomez, P.M.; Mendez-Palos, E.; Galvez, J.; Alvarez, J.G.; Alanis, A.Y. Control Crisis in Financial Systems with Dynamic Complex Network Approach. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3922. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13243922

Venegas HG, Ibarra A, Gomez PM, Mendez-Palos E, Galvez J, Alvarez JG, Alanis AY. Control Crisis in Financial Systems with Dynamic Complex Network Approach. Mathematics. 2025; 13(24):3922. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13243922

Chicago/Turabian StyleVenegas, Hugo G., Alejandra Ibarra, Pedro M. Gomez, Eduardo Mendez-Palos, Jorge Galvez, Jesus G. Alvarez, and Alma Y. Alanis. 2025. "Control Crisis in Financial Systems with Dynamic Complex Network Approach" Mathematics 13, no. 24: 3922. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13243922

APA StyleVenegas, H. G., Ibarra, A., Gomez, P. M., Mendez-Palos, E., Galvez, J., Alvarez, J. G., & Alanis, A. Y. (2025). Control Crisis in Financial Systems with Dynamic Complex Network Approach. Mathematics, 13(24), 3922. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13243922