Abstract

This study focuses on a multi-objective heterogeneous parallel machine planning problem for industrial silicon smelting. Specifically, under the conflicting objectives of minimizing carbon emissions, rollover penalty costs, and load imbalance, the total production demand of industrial silicon is allocated monthly across multiple machines. We first establish the mathematical model of the problem accounting for real-life management requirements. To solve the model, a Gaussian learning-based Pareto evolutionary algorithm (GLPEA) is proposed. The algorithm is developed based on a nondominated sorting framework and incorporates two key innovations: (1) a generation-wise dynamic Gaussian mixture component selection strategy that adaptively fits the multimodal distribution of elite solutions, and (2) a hybrid offspring generation mechanism that integrates traditional evolutionary operators with a Gaussian sampling strategy trained on perturbed solution sets, thereby enhancing exploration capability while maintaining convergence. The effectiveness of GLPEA is validated on 40 problem instances of varying scales. Compared with NSGA-II and MOEA/D, GLPEA achieves average improvements of 5.78% and 89.23% in IGD, and 1.03% and 264.43% in HV, respectively. We make the source codes of GLPEA publicly available to facilitate future research on practical applications.

MSC:

90-10

1. Introduction

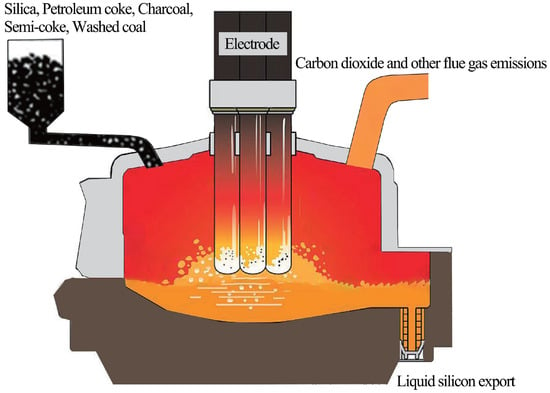

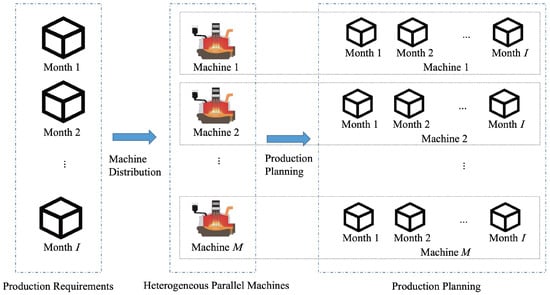

Industrial silicon plays an irreplaceable role in strategic emerging industries, such as photovoltaics, semiconductors, and aluminum [1]. Over the past two years, the authors conducted a practical project for a cooperative industrial silicon factory in Yunnan, China. Our task was to make production planning for heterogeneous parallel furnaces. As illustrated in Figure 1, the smelting process involves raw materials including silica, cleaned coal, charcoal, semi-coke, and petroleum coke, yielding molten industrial silicon while substantial . Figure 2 provides an overview of the production planning framework in the factory. The factory has a fixed monthly delivery demand, and the planning task consists of allocating the output of each furnace to meet this demand. Each furnace follows a maintenance planning, and its monthly output must not exceed its rated capacity minus downtime. Furnace load is quantified as the total assigned production during the planning period, and the combined output of all furnaces must equal the total demand. Unfinished tasks are rolled over to subsequent months, incurring a penalty cost, while excess production is treated as early output for the following month. The carbon emission factor, which varies by furnace and month, reflects the emissions per ton of silicon produced. The rollover penalty factor is the cost per ton of delayed delivery. Reducing rollover penalties requires assigning more tasks to higher-capacity furnaces. This may worsen load imbalance and increase emissions. Conversely, minimizing emissions or balancing loads could raise penalties. Therefore, the three objective functions in nature conflict with each other.

Figure 1.

Illustration of industrial silicon smelting process.

Figure 2.

Overview of planning for industrial silicon production.

Given the above real-life applications, we propose introducing a specific heterogeneous parallel machine planning problem (HPMPP). However, no single algorithm can optimize the three conflicting objective functions simultaneously. Therefore, multi-objective evolutionary algorithm (MOEA) can be a suitable solution method. MOEAs use a parallel search framework to find approximate Pareto front (APF) within an acceptable CPU time frame [2].

However, as will be analyzed in detail in Section 2, classical multi-objective evolutionary algorithms (MOEAs) such as NSGA-II, although widely applied, rely heavily on “blind” stochastic search operators. Often, the nondominated sorting model is short for finding promising solutions in certain search regions when there are more than two objective functions. It may also suffer from reduced convergence precision [3,4,5]. To overcome these limitations, machine learning has shown potential to improve MOEAs. Gaussian learning has attracted increasing attention due to its strong capability in distribution fitting. A single-component GMM only offers a unimodal approximation of the primary elite cluster, whereas a multi-component GMM can better represent multimodal distributions of multiple high-quality solution clusters [6]. Therefore, employing different GMM components at different search stages of MOEAs can help yield improved results. In addition, the performance of GMM highly depends on the quality of its training data. If the GMM is trained solely on the current Pareto elite solutions, it tends to perform “local exploitation” around the discovered elites. This leads to a rapid loss of global exploration ability, causing the population to prematurely converge to a local Pareto front. This paper proposes GLPEA for solving HPMPP in industrial silicon smelting. GLPEA employs a Gaussian distribution to discover high-quality offspring solutions and a dedicated GMM training strategy to enhance global exploration. We additionally design a problem-specific repair operator to handle infeasible solutions encountered during the search process. The contributions of this work are summarized as follows.

First, from the modeling perspective, HPMPP aims to optimize rollover penalty costs, carbon emissions, and load imbalance. To our knowledge, this is the first work to model the industrial silicon production planning problem within such a framework. This work provides valuable guidance for managers who desire to balance these objectives. We use 40 problem instances of varying sizes and make the source code of the algorithm publicly available. These resources would be useful to facilitate future research on algorithm benchmarking and applications.

Second, from the algorithm perspective, we introduce a generational dynamic GMM component selection strategy into the nondominated sorting framework. This differs from most studies that use fixed-component GMMs. Our strategy adapts the number of components at each generation, leading to improved model flexibility and sampling effectiveness across different search stages. The perturbed solution set GMM training strategy further enhances exploration during the search. The proposed GLPEA provides useful insights for researchers and practitioners working on complex heterogeneous parallel machine planning problems.

Third, our GMM strategy is of general interest. It can guide the design of new operators within any nondominated sorting framework. Integrating this strategy into other MOEAs could improve their convergence and exploration. Therefore, our findings offer a valuable reference for advancing MOEAs.

2. Related Work

2.1. Classical MOEAs

With the growing consensus on sustainable manufacturing, scheduling objectives have substantially evolved. Optimization now extends beyond the traditional two-dimensional “efficiency–cost” trade-off to higher-dimensional objectives encompassing “efficiency–cost–environment.” MOEAs have become mainstream tools for addressing such complexity. Generally, MOEAs can be categorized into: (a) dominance-based MOEAs, such as NSGA-II [7] and SPEA-II [8], which rank and select solutions based on Pareto dominance levels and crowding distance (or similar diversity indicators); (b) decomposition-based MOEAs, such as MOEA/D [9] and MOGLS [10], which decompose a multi-objective problem into a set of single-objective subproblems and exploit neighborhood relationships among subproblems for cooperative optimization, and (c) indicator-based MOEAs, such as SMS-EMO [11,12], which directly employ performance indicators (e.g., hypervolume) as selection criteria to drive the population toward a better Pareto front. In particular, the NSGA-II model has shown powerful search performance for solving the parallel machine planning problem [13,14]. Its search process relies on nondominated sorting and crowding distance mechanisms to discover promising search regions. Motivated by these studies, we adopt the nondominated sorting search model of NSGA-II in this work.

Despite their remarkable success, classical MOEAs still face inherent limitations. Their evolutionary operators are often inherently “blind,” relying purely on stochastic perturbations and heuristic selection. This traditional approach lacks the capability to perceive the topological structure of the search space or discern the distribution characteristics of high-quality solutions [15,16]. Such “blind” exploration often leads to limited search efficiency and consequently slow convergence. To overcome these limitations, researchers have introduced machine learning techniques to enhance the performance of MOEAs.

2.2. Surrogate-Assisted MOEAs

The core idea of Surrogate-Assisted MOEAs (SA-MOEAs) is to employ a computationally inexpensive machine learning model (surrogate) to approximate the true objective function, primarily targeting scenarios where evaluations are computationally expensive. Studies by Balekelayi N [17], Rossmann J [18], and Hebbal A [19] have successfully demonstrated that optimization based on Gaussian processes (GP) can achieve faster convergence to the optimal Pareto front than NSGA-II. Wu H [20] and Ravi K [21] further explored sparse and multi-fidelity GPs to improve efficiency on medium-scale problems. Gaussian processes are particularly valuable as they not only provide predictive means but also quantify predictive uncertainty, making them ideal models for Bayesian Optimization (BO) [22], which intelligently balances exploration and exploitation through acquisition functions. Other Surrogate-Assisted MOEAs have also been widely used. For instance, research by Zhang H [23] demonstrated that the Inverse Gaussian Process (IGP)-based MOEA significantly improves performance in dynamic optimization. Research by Yang Z [24] and Niu Y [25] introduced surrogate models based on Radial Basis Functions (RBF), effectively enhancing prediction accuracy. Studies by Sonoda T [26] and Xu D [27] developed surrogate-assisted MOEAs using Support Vector Machines (SVMs), achieving high computational efficiency. Moreover, works by Zhu E [28] and De Moraes M. B [29] demonstrated that surrogate-assisted MOEAs using Random Forests (RF) exhibit outstanding optimization performance.

However, the primary challenge for the HPMPP considered in this study differs significantly from the expensive-evaluation scenario. In this industrial context, production plans are typically established at the beginning of each planning cycle and executed strictly thereafter. The objective function evaluation frequency is thus relatively low. Consequently, the main challenge lies not in computationally expensive evaluations but in the inherently low search efficiency, reflected by slow convergence and limited solution quality improvement. Under such circumstances, the advantages of SA-MOEAs become less pronounced, as their designs are tailored for expensive-evaluation problems and may introduce additional computational overhead, making them less suitable for improving search efficiency in our HPMPP context.

2.3. Estimation of Distribution Algorithms (EDAs)

A distinct paradigm for enhancing MOEAs is the Estimation of Distribution Algorithms (EDAs), which replace traditional genetic operators (crossover and mutation) with a statistical learning or probabilistic generative model. The core principle involves learning the probability distribution of high-quality solutions in the decision space and subsequently sampling new offspring based on this learned model to generate potentially superior solutions [30].

Empirical studies by Wang F [31], Li G [32], and Zou J [33] have demonstrated that GMM-based MOEAs exhibit excellent performance across a wide range of benchmark and real-world problems. Lu C [34] and Aggarwal S [35] proposed MOEAs based on the Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy (CMA-ES), which feature lightweight design and faster execution. Zhang W [36] improved the Regularity Model-based Estimation of Distribution Algorithms (RM-MEDA), enhancing convergence performance. Kalita K [37] introduced the Multi-objective exponential distribution optimizer (MOEDO), which achieves robust performance in balancing diversity and convergence efficiency.

2.4. Analysis and Proposed Approach

For the HPMPP addressed in this study, we aim to solve planning problems that are computationally challenging yet required to be completed within an acceptable CPU time frame. Among existing methods, GMM-based MOEAs are well suited for this purpose. Compared with other probabilistic models, the GMM has been widely validated as effective—particularly in industrial applications—by researchers such as Alghamdi A. S [38], Guerrero-Peña E [39] and Yazdi F [40]. Moreover, GMMs are data-efficient, capable of robustly fitting multimodal distributions even with small to medium sample sizes. Considering practical industrial applicability and algorithmic stability, we adopt the GMM as the probabilistic generative model in this work. In recent years, many studies have sought to enhance the performance of GMM-based sampling strategies. Zhang J [41] decomposed the overall problem into several subproblems and employed multi-component GMMs to capture diverse solution patterns, thereby improving population diversity. Abdulghani A. M [42] proposed the NA-GMM, which integrates adaptive weighting of features and node importance weighting to further enhance diversity.

Most existing studies employ a fixed number of Gaussian components throughout the evolutionary process, which is theoretically suboptimal. During the early evolution stage, the population distribution is broad and dispersed; a simple GMM can adequately capture the global trend, while using an excessive number of components may lead to overfitting. In later stages, when the population converges to a refined and complex Pareto front with multiple distinct elite clusters, a low-component GMM fails to distinguish these clusters, resulting in underfitting. Therefore, we introduce a generation-wise dynamic Gaussian mixture component selection strategy. Furthermore, the training dataset of the GMM has a significant impact on its sampling performance. A training set with greater diversity enables more diverse sampling results. To this end, we propose a GMM training strategy based on perturbed solution sets to enhance the diversity of the solution space and improve global exploration capability.

3. Mathematical Model of HPMPP

HPMPP involves allocating predetermined monthly production targets to a set of heterogeneous parallel machines (furnaces). Given the monthly rollover penalty factors, machine maintenance schedules, capacity limits, and deep learning-predicted carbon emission factors, the objective is to determine the monthly capacity allocation across machines that optimizes the three objective functions detailed below.

3.1. Assumptions

The proposed HPMPP model is based on the following assumptions.

(a) The maximum monthly production capacity of each machine is fixed and time-invariant.

(b) No unexpected interruptions occur during the production process, allowing the analysis to focus on the inherent trade-offs among the optimization objectives.

3.2. Parameters

To clearly construct the model and algorithm, this section classifies all relevant parameters into two categories: Table 1 defines the model parameters of the industrial silicon scheduling problem, while Table 2 defines the algorithm parameters of the proposed GLPEA.

Table 1.

The model parameters of the industrial silicon scheduling problem.

Table 2.

The algorithm parameters of the proposed GLPEA.

3.3. Decision Variables

| Production volume of month on machine ; | |

| Cumulative amount of unfulfilled demand in month i; | |

| Unfulfilled demand in month i; | |

| Load of machine j. |

3.4. Objective Functions

The objective of HPMPP is to minimize carbon emissions (f1), minimize rollover penalty costs (f2), and minimize load imbalance (f3). The carbon emissions (f1) are obtained by multiplying the production of each machine in each month by the corresponding unit carbon emission coefficient and summing over all machines and months. The monthly rollover penalty (f2) is calculated based on unfinished demand: for each month i, the actual total production is compared with the demand for that month, including any rollover from the previous month. If production is insufficient, an unfinished amount is generated; if production exceeds demand, the surplus offsets the following month’s demand. The unfinished amount for each month is multiplied by the monthly rollover penalty coefficient , and the sum over all months gives the total penalty. Load imbalance (f3) is calculated by first computing the total production load of each machine over the entire scheduling period. The squared deviations of each machine’s total load from the average load are then summed to represent the load imbalance.

Subject to:

3.5. Carbon Emission Factor Prediction

In the proposed mathematical model, the carbon emission factor denotes the carbon emissions per ton of silicon product. Although emissions generally scale with output, the factor is also influenced by operational efficiency, energy consumption, and climatic conditions (e.g., temperature, humidity, rainfall), leading to monthly variations. Therefore, it can vary from month to month. Accurate prediction of this factor is important for emission management. Hochreiter et al. [43] showed that long short-term memory (LSTM) networks perform well on nonlinear time-series prediction.

3.5.1. Datasets and Preprocessing

We collected five years (2020–2024) of production data from an industrial silicon smelting plant (The data set is available at https://gitee.com/zhangjinsi_p/glpea/blob/master/dataset.xlsx, accessed on 30 September 2024). It covers seven furnaces (#1 to #7), with monthly records for each furnace. In total, there are 60 months, comprising 420 entries of monthly production, carbon dioxide emissions, and carbon emission factors. The monthly production is measured in tons and represents the output of each furnace for the corresponding month. The carbon dioxide emissions are also measured in tons, indicating the output of each furnace per month. The carbon emission factor represents the ratio of emissions to production for each furnace in the corresponding month, i.e., the amount of emitted per ton of industrial silicon produced.

As the dataset is relatively small but of high quality, we performed a thorough inspection and found no missing values or obvious outliers. For data preprocessing, we applied the RobustScaler method for standardization. Bachechi et al. [44] showed that this method reduces the impact of outliers and noise.

The dataset was split into training and test sets at an 80:20 ratio. It is worth noting that when the dataset is limited in size, setting aside a separate validation set can significantly reduce the valuable data available for model training. Therefore, we adopted cross validation for time series [45]. Specifically, we set a validation window corresponding to a complete seasonal cycle (window size = 12) and rolled it forward within the training set, ensuring that each validation set only contains data that the model has not seen during training and occurs later in chronological order.

3.5.2. Feature Engineering

Inspired by Box [46], Ma [47], and Dong [48], we construct multidimensional features to capture periodicity, lag effects, and local statistical properties in time series.

(a) Periodic features. We map the month index to a periodic variable. We encode the 12-month cycle using sine and cosine functions as follows:

where represents the month index in the cycle. The cycle length months. This encoding captures seasonal variation and the periodic effects of temperature, humidity, and rainfall.

(b) Lag features and padding. To reflect the influence of past values, we use the observations from the three most recent time steps as lag features. We denote them , , and .

(c) Sliding-window statistical features. To capture local trends and volatility, we compute statistics over a fixed window of size w = 12 (including the current time t). We have

We additionally calculate the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean to capture local volatility as follows:

Toward that end, at each time step t, we construct a feature vector as follows:

3.5.3. Model Structure and Loss Function

We employed a single-layer LSTM encoder, followed by a fully connected (FC) layer, to predict the estimated carbon emission factor for the next time step, , which approximates the true value . The Mean Squared Error (MSE) [49] was utilized as the loss function:

where N represents the number of samples, denotes the true (or actual) value, and is the predicted value from the model.

3.5.4. Model Parameters

The number of LSTM hidden units (lstm_unit) and the Dropout rate (dropout_rate) significantly influence the model’s generalization ability and fitting performance. We conducted an experimental grid search involving nine different combinations of these parameters. The results are presented in Table 3. As shown in the table, the combination of lstm_unit = 48 and dropout_rate = 0.3 yielded the lowest MSE score. Consequently, this optimal hyperparameter set was selected for the training of the final model.

Table 3.

Experimental results of model parameters.

3.5.5. Evaluation and Prediction Results

The model’s performance was evaluated using the Mean Squared Error (MSE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) [50], and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) [51]. The resulting metrics were , , and . Overall, the model achieved low prediction errors, demonstrating its excellent predictive performance.

The trained model is used to forecast monthly carbon emission factors for each furnace over a 12-month horizon. The results are reported in Table 4.

Table 4.

Predicted carbon emission factors for furnaces #1–#7 over the next 12 months.

4. Proposed GLPEA for HPMPP

In GLPEA, we encode a solution with a two-dimensional matrix X. The matrix has I rows and M columns. Each element . represents the production assigned to machine j in month i. Based on this solution representation method, we detail the search components of GLPEA below.

4.1. Proposed Problem-Specific Repair Operator

To ensure all solutions satisfy the problem constraints during the search process of GLPEA, a dedicated repair operator is proposed in Algorithm 1. The repair operator first constructs a capacity upper-bound matrix to represent the available capacity of machine j in month i accounting for maintenance (lines 3–8). Next, the infeasible solution matrix and the capacity matrix are vectorized (lines 9–10). Thereafter, a bisection search determines the shift parameter such that the projection results a solution satisfying the total production demand with a tolerance (lines 13–23), thereby enforcing both bound constraints and demand satisfaction. The repaired vector is then reshaped into the final feasible matrix (Line 24). Note that in determining , we set . Based on our preliminary observations, such an is sufficient to find a suitable value.

| Algorithm 1 Proposed problem-specific repair operator |

|

4.2. Gaussian Mixture Model

4.2.1. Univariate Gaussian Distribution

The univariate Gaussian distribution (normal distribution) is one of the most common continuous probability distributions. Its probability density function is defined as:

where is the random variable, is the mean, and is the variance. Given a set of independent and identically distributed samples , the parameters and are calculated as follows:

4.2.2. Multivariate Gaussian Distribution

The multivariate Gaussian distribution generalizes the univariate case. It describes the joint distribution of a D-dimensional continuous random vector x. Its probability density function is:

where is the mean vector. is the covariance matrix, which describes the correlations among the dimensions. denotes the determinant of the covariance matrix.

4.2.3. Adopted Gaussian Mixture Model

GMM assumes that each data point x is generated from a weighted combination of K Gaussian distributions [52]. Its probability density function is expressed as follows:

where denotes the mixing weight of the k-th Gaussian component, satisfying . and represent the mean vector and covariance matrix of the k-th Gaussian distribution, respectively. The parameters of GMM are usually estimated using the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm [53]. The EM algorithm consists of two steps:

Expectation step (E-step): In this step, the posterior probability that each data point belongs to each Gaussian component, namely the responsibility, is calculated. represents the probability that the i-th data point is generated by the k-th Gaussian component, and t denotes the current iteration. The formula is given as follows:

Maximization step (M-step): In this step, the parameters are updated using the posterior probabilities obtained from the E-step. The new parameters are estimated by maximizing the log-likelihood function. The mixing weights are updated as follows:

where represents the total responsibility of all data points for the k-th Gaussian component. Note that N is the total number of data points.

Thereby, the mean vector and covariance matrix are updated as follows:

Toward that end, the EM algorithm can alternates between the E-step and the M-step. It increases the log-likelihood at each iteration until it converges to a local optimum.

4.3. Main Framework of GLPEA

As mentioned earlier, GLPEA employs a Gaussian mixture model-based non-dominated sorting framework. The general framework of the algorithm is given in Algorithm 2. Initially, a population of size is randomly generated. The objective function calculation module evaluates three objective values for each individual. At each generation, the population first undergoes non-dominated sorting. Subsequently, a perturbed solution set is constructed for Gaussian model training (Section 4.4). Offspring are then generated using a Gaussian mixture model-based evolutionary method (Section 4.5). The parent and offspring populations are merged to form a temporary population, which then undergoes non-dominated sorting and crowding distance calculation. Finally, an elitism preservation strategy selects the top optimal individuals to form the new-generation population. This process continues until the maximum generation number is reached, ultimately outputting an approximate Pareto-optimal solution set.

| Algorithm 2 Main framework of GLPEA |

|

4.4. Proposed Gaussian Model Training Strategy Based on Perturbed Solutions

The proposed training strategy is implemented by constructing a specific GMM training dataset, denoted as training_data. The procedure is presented in Algorithm 3. First, the indices of perturbed points are randomly selected from the current Pareto front solutions, denoted as pareto_solutions. The number of perturbed solutions is determined by the product of the number of current Pareto solutions (n) and the disturbance ratio of Pareto solutions () (Lines 1–3). Then, inspired by the mutation operator in differential evolution (DE), multiple diversity-enhanced new solutions are generated for each selected Pareto solution (Lines 4–7). After repairing infeasible solutions, the feasible ones are added to the new solution set (Lines 8–9). Finally, the GMM training dataset is constructed by merging the current Pareto front set with the new solution set (Line 11). The core mutation formula of DE [54] is given as follows:

In Equation (22), relevant parameters are defined as follows: X is the original Pareto solution; represent a randomly selected pair of Pareto solutions; and serves as the perturbation intensity factor.

| Algorithm 3 Gaussian model training strategy based on perturbed solutions |

|

4.5. Gaussian Mixture Model Combined Evolutionary Method

In GLPEA, a GMM strategy with dynamically selected component numbers per generation is employed to choose the optimal number of components for each generation. The procedure is presented in Algorithm 4. The hybrid reproduction strategy generates offspring using both GMM sampling and traditional genetic operations. Let denote the number of offspring generated per generation and the GMM sampling rate. denotes the GMM training dataset constructed in Section 4.4, and represents the population. If the sampling rate criterion is satisfied, GMM sampling is performed; otherwise, traditional genetic operations are applied. During GMM sampling, all candidate points are flattened and normalized to a standard normal distribution (Lines 3–4). The number of components is traversed from 1 to the maximum component number (), and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) [55] is used to evaluate the models. The model with the smallest BIC corresponds to the optimal number of components, and this GMM is then used for sampling (Lines 5–17). After repairing infeasible solutions, the sampled offspring are added to the offspring solution set (Lines 18–20). Note that = 5 is set when determining the optimal number of components. Based on our preliminary observations, this value is sufficient to find an appropriate component number. For the traditional genetic operation, parents are selected by binary tournament selection (Lines 23–24; see Section 4.6), followed by crossover and mutation to generate two offspring, which are then added to the offspring solution set (Lines 25–31).

4.6. Binary Tournament Parent Selection

In the traditional genetic algorithm, binary tournament selection is used to choose the parent individuals for crossover and mutation. We give the binary tournament selection is described in Algorithm 5. Let be the positions of individuals in each non-dominated front within the , and the front level to which each individual belongs.

As Algorithm 5 shows, a zero vector with a length equal to the population size is first initialized to store the crowding distance of each individual (Line 1). Then, each non-dominated front is traversed (Line 2), and the crowding distance of all individuals in the current front is calculated (Line 3). The calculated distances are assigned to the corresponding positions in the vector (Lines 4–5). Next, two distinct indices are randomly sampled from the set of population indices (Line 8). The selected candidate solutions are compared according to their non-dominated sorting ranks, and the solution with a lower rank (i.e., higher quality) is selected (Lines 9–12). If the two candidates have the same rank, the crowding distance is used as the criterion, and the one with a larger crowding distance is selected to maintain population diversity (Lines 14–19).

| Algorithm 4 Proposed GMM combined evolutionary method |

|

| Algorithm 5 Adopted binary tournament selection operator |

|

5. Experiment Results and Comparisons

5.1. Test Instances and Experimental Design

We consider the combinations yielding 40 instances. For each instance, GLPEA and the comparison algorithms are each run independently 20 times. Experimental results are reported as Best, Worst, and Mean, representing the best, worst, and average values of the performance metrics. All algorithms are implemented in Python 3.8 and executed on a PC running macOS with an Intel Core i7 2.7 GHz quad-core processor and 16 GB of RAM (The source code, test instances, and results are available at https://gitee.com/zhangjinsi_p/glpea.git, accessed on 30 September 2024).

5.2. Performance Metrics

To evaluate the solution quality achieved by GLPEA and compared algorithms, two well-known MOEA performance metrics are used in this work [56].

IGD quantifies the proximity between the solution sets generated by an algorithm and the reference Pareto front (or true Pareto front). It calculates the average Euclidean distance from each point in the reference Pareto front to its nearest neighbor in the algorithm’s solution set. The metric is formulated as follows:

where denotes the reference Pareto front (or true Pareto front), and A represents the solution set obtained by a given compared algorithm. Note that we combine the solutions obtained by all compared algorithm and then identify from these solutions. A smaller IGD value indicates closer proximity to the true Pareto front, reflecting superior convergence performance.

HV measures the multidimensional space between a reference point r and the solution set, reflecting the breadth and diversity of the distribution. HV is defined as follows:

where represents a predefined reference point in the objective space. A larger HV value signifies stronger exploration capability, with solutions exhibiting a more comprehensive and balanced distribution in the objective space.

5.3. Parameter Settings

GLPEA has six parameters: population size (), crossover probability (), mutation probability (), Gaussian sampling rate (), disturbance scaling factor (), and disturbed ratio of the Pareto solutions (). To find a suitable parameter combination of these parameters, the Taguchi method is employed using the instance “m7i12”. In this approach, the search performance of GLPEA under different parameter settings is evaluated using the two performance metrics. A design-of-experiments (DOE) procedure is adopted to generate candidate parameter combinations. As shown in Table 5, four levels are assigned to each parameter, and an orthogonal array with 25 experimental runs is used. For each parameter combination, GLPEA is executed independently 20 times with . The corresponding performance metrics are given (see Table 6). A proper parameter combination should minimize IGD while maximizing HV. To facilitate comparison, both IGD and HV values are normalized, and the signal-to-noise ratio () is used as the response variable. Our goal is to identify the parameter combination that yields the highest ratio, which is calculated as follows:

where m is the number of GLPEA executions, and represents the composite performance score obtained from the normalized IGD and HV values in the k-th run.

Table 5.

Parameter levels.

Table 6.

Orthogonal array and response values.

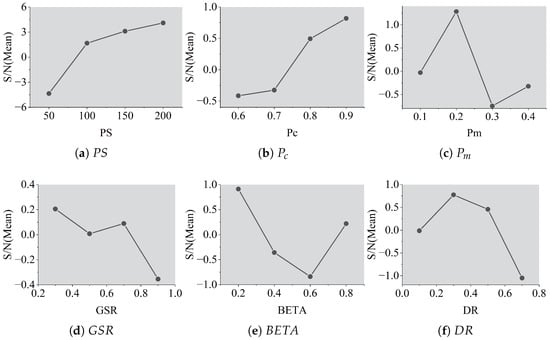

Based on the results in Table 6, the level trends of the parameters are illustrated in Figure 3. The six parameters are set as follows: , , , , , and . To validate these settings, additional parameter tuning experiments are conducted on the instances “m7i4" and “m11i4", which confirms the above parameter settings.

Figure 3.

Level trends of parameters ().

5.4. Effectiveness of GLPEA’s Search Components

We evaluate the effectiveness of the search components of GLPEA by comparing it with two variant algorithms: GLPEA_V1 and GLPEA_V2. GLPEA_V1 is a variant in which the generational dynamic component-selection strategy of GMM is replaced with a single-component Gaussian model. In GLPEA_V2, the Gaussian model training based on disturbed solutions is removed, and only the GMM sampling mechanism is retained for offspring generation. For fair comparisons, all algorithms are run with . The comparative results are given in Table 7 and Table 8.

Table 7.

Comparisons of GLPEA, GLPEA_V1, and GLPEA_V2 (IGD).

Table 8.

Comparisons of GLPEA, GLPEA_V1, and GLPEA_V2 (HV).

As Table 7 and Table 8 show, GLPEA outperforms the two variant algorithms in both IGD and HV, indicating its superior solution quality. To verify the statistical significance of these improvements, we performed the Wilcoxon signed-rank test [57]. Statistical analysis shows that the p-values (presented at the bottom of the table) for all two algorithm pairs are all less than 0.05, confirming the significant improvement in convergence and exploration capabilities achieved by GLPEA. These results validate the effectiveness of the generation-wise dynamic component-selection strategy and the disturbed-solution-based GMM training method, combined with conventional genetic operations for offspring generation, within the nondominated sorting framework. The proposed approach demonstrates considerable potential for applications in other multi-objective evolutionary algorithms.

5.5. Comparisons with State-of-the-Art MOEAs

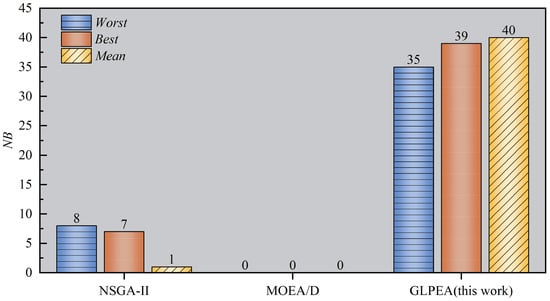

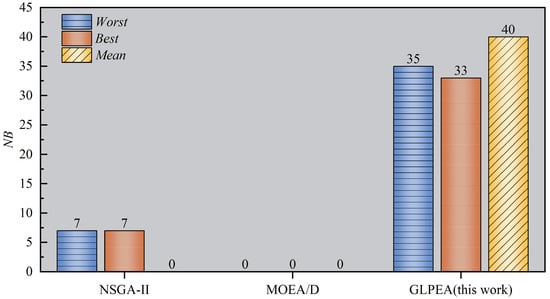

We evaluate the performance of GLPEA by comparing it with two state-of-the-art MOEAs: NSGA-II and MOEA/D. Both reference algorithms are configured using the parameter settings reported in their original studies, and the same stopping condition described in Section 5.4 is applied. To facilitate a quantitative comparison, we introduce the metric , which denotes the number of instances in which an algorithm achieves the best value for a given quality indicator. The comparative results are reoprted in Table 9 and Table 10, and the distributions of values are shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Table 9.

Comparisons of NSGA-II, MOEA/D, and GLPEA (IGD).

Table 10.

Comparisons of NSGA-II, MOEA/D, and GLPEA (HV).

Figure 4.

Distributions of NB values obtianed by NSGA-II, MOEA/D, and GLPEA (IGD).

Figure 5.

Distributions of NB values obtianed by NSGA-II, MOEA/D, and GLPEA (HV).

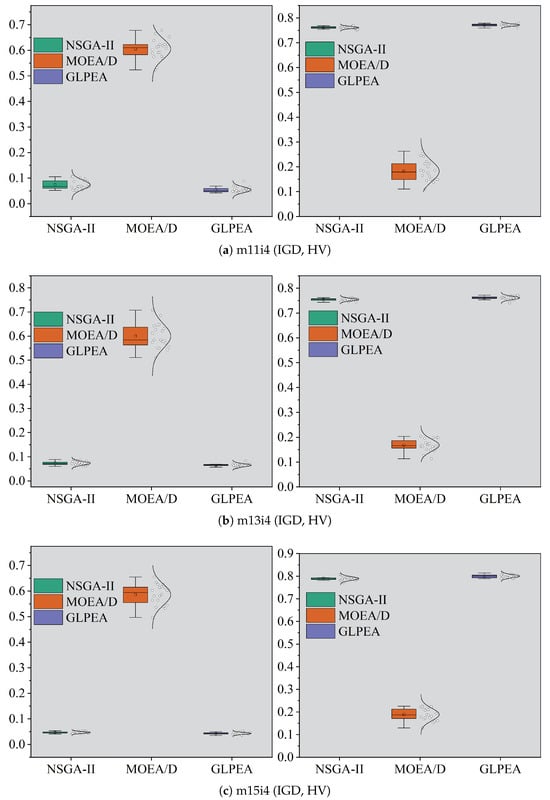

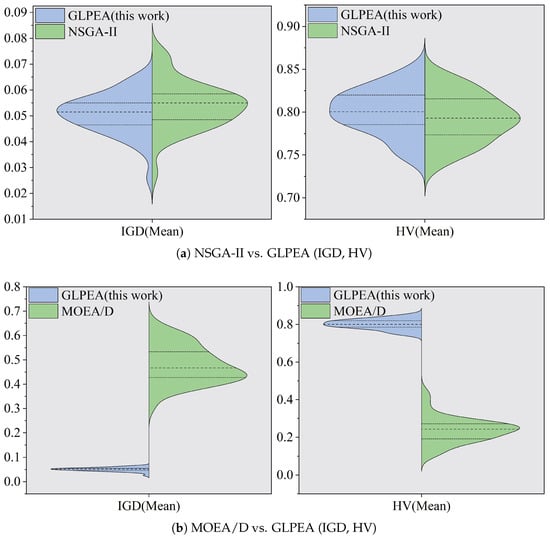

From Table 9 and Table 10, one observes that GLPEA outperforms the two reference algorithms in terms of worst, best, and average for almost all these problem instances. The p-values obtained from the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (presented at the bottom of the table) were all substantially less than . This indicates that the observed improvements of GLPEA in both convergence and diversity are statistically significant. Furthermore, as shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5, GLPEA achieves higher values than those of the reference algorithms, indicating its superior consistency in obtaining the best search performance. The statistical distributions of the results are further analyzed through the box plots for selected instances (“m11i4”, “m13i4”, and “m15i4”) in Figure 6, and violin plots summarizing the IGD and HV results are provided in Figure 7. These distributions collectively confirm the competitive search capability of GLPEA. Based on the comprehensive experimental analysis, GLPEA can be regarded as an effective solution approach for HPMPP. Given the practical relevance of HPMPP, the proposed algorithm holds promise for extension to other production planning problems in industrial silicon manufacturing.

Figure 6.

Box plots for NSGA-II, MOEA/D, and GLPEA.

Figure 7.

Violin plots for MOEA/D, NSGA-II, and GLPEA (Mean).

5.6. Computational Overhead and Limitations Analysis

5.6.1. Analysis of Computational Time

This section analyzes the computational time of the GLPEA. All experiments were executed on the hardware described in Section 5.1. Notably, the GLPEA does not require specialized hardware resources, such as GPUs, for execution. For each instance, GLPEA and the compared algorithms are executed independently 20 times with . To quantitatively compare the execution time, Table 11 presents the average execution time (in seconds) of the three algorithms across 40 instances.

Table 11.

The average execution time (in seconds) of the three algorithms.

As detailed in Table 9, we observed that the computational time generally increases with the size of the problem instance for most cases. The execution time of GLPEA is significantly higher than NSGA-II but lower than MOEA/D. This finding aligns with the higher computational complexity inherent in the Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) training integrated into GLPEA. This increase in computational overhead is anticipated; unlike the lightweight stochastic operators of NSGA-II, the primary computational burden of GLPEA stems from the GMM training.

5.6.2. Analysis of Computational Complexity

To theoretically analyze the computational overhead of GLPEA, we base our analysis on the HPMPP problem studied in this research, where is the population size and is the dimension of the problem’s decision variables. We analyze the main computational complexity per generation of the algorithm. (1) GLPEA adopts the non-dominated sorting framework of NSGA-II. Since the number of objective functions is a constant (three), the computational complexity of non-dominated sorting can be simplified to ; the complexity of calculating the crowding distance is . Thus, the complexity of the traditional evolutionary mechanism is . (2) Based on the analysis presented in Section 4.2.3, the computational complexity of the GMM training is primarily determined by the calculation of the covariance matrix, which is approximately , where t is the number of EM iterations and k is the number of components. Since t and k are constants, the complexity of GMM training is simplified to . In summary, the total computational complexity of GLPEA per generation is .

5.6.3. Method Limitations and Industrial Applicability

As discussed above, the complexity scales with due to the GMM training as the problem size increases, leading to a rapid increase in the algorithm’s computational time. This observation is consistent with the computational time trend of GLPEA shown in Table 11. Regarding parameter sensitivity, GLPEA introduces new parameters such as , , and . Although this study determined a suitable combination of parameters in Section 5.3, the algorithm’s performance might be sensitive to these parameters. Re-tuning the parameters may be required when applying the algorithm to new problems, which can be time-consuming.

Despite these limitations, in the context of HPMPP, planning is typically executed periodically and offline. Therefore, obtaining a superior Pareto front, as shown in Table 9 and Table 10, within the computational time demonstrated in Table 11 on modern computing hardware, is fully acceptable. Thus, GLPEA retains strong industrial applicability.

5.7. Discussions

We further evaluate the solution quality of GLPEA concerning the following issues: (a) the trends of IGD and HV values for GLPEA, NSGA-II, and MOEA/D; and (b) a comparison of APFs obtained by the three algorithms. These analyses help verify the search behavior of GLPEA and the distribution of its final solutions.

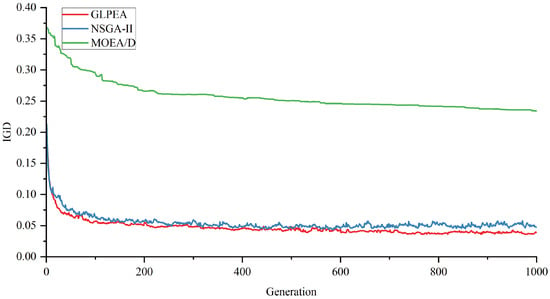

5.7.1. Trends of IGD and HV Achieved by GLPEA, NSGA-II, and MOEA/D

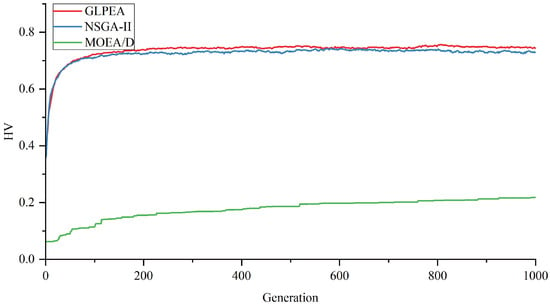

Using the instance “m7i4”, we execute GLPEA, NSGA-II, and MOEA/D with a stopping condition of . At each generation, the IGD and HV values are calculated and recorded based on the nondominated solutions identified from the populations of the three algorithms. The resulting trends of IGD and HV of GLPEA and the two reference approaches are given in Figure 8 and Figure 9.

Figure 8.

Trends of IGD obtained by GLPEA, NSGA-II, and MOEA/D.

Figure 9.

Trends of HV obtained by GLPEA, NSGA-II, and MOEA/D.

As shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9, GLPEA consistently achieves lower IGD values and higher HV values than NSGA-II and MOEA/D throughout the whole iterative process. This indicates a smaller distance to the reference Pareto front and a broader coverage of the objective space, collectively confirming GLPEA’s superior capability in exploring diverse regions of the Pareto front.

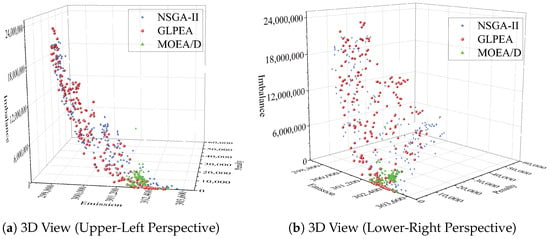

5.7.2. APFs Solved by GLPEA, NSGA-II, and MOEA/D

To analyze the distributions of APFs obtained by GLPEA and the two state-of-the-art solution methods, we draw the APFs of the three methods in Figure 10. We note that this analysis is again based on the instance “m7i4” and under the stopping condition of .

Figure 10.

APFs obtained by GLPEA, NSGA-II, MOEA/D.

Based on the distributions of obtained APFs shown in Figure 10, GLPEA achieves superior uniformity and coverage across all three objectives in the Pareto front, outperforming NSGA-II (which ranks second) and MOEA/D (which shows the weakest performance in both coverage and distribution uniformity). Moreover, these results reflect inherent conflicts among the three optimization objectives: emission control, rollover penalty costs, and load balancing. As a result, a significant improvement in one objective generally leads to deterioration in the others, resulting in a dispersed Pareto front rather than a single optimal solution.

6. Conclusions

We investigate a multi-objective heterogeneous parallel machine scheduling problem arising from industrial silicon smelting, with the aim of simultaneously minimizing carbon emissions, rollover penalty costs, and load imbalance. The model incorporates practical constraints including machine maintenance schedules and monthly production demands, while carbon emission factors are predicted using a machine learning approach for a 12-month horizon. From the algorithmic perspective, the proposed GLPEA introduces a generation-wise dynamic component-selection strategy within a GMM framework, enhanced by a disturbed-solution-set-based training scheme, and integrated with conventional genetic operators for offspring generation. Extensive computational experiments demonstrate that GLPEA achieves superior performance compared to state-of-the-art MOEAs in terms of both IGD and HV metrics.

For future research, carbon emission forecasting could be improved through advanced techniques such as multimodal fusion prediction. Further enhancement of the algorithm may also be achieved by developing more adaptive mechanisms for determining the number of Gaussian mixture components during evolution.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: R.L. and Z.L.; Methodology: J.Z., R.L. and Z.L.; Software: J.Z.; Validation: J.Z. and Z.L.; Investigation: J.Z., R.L. and Z.L.; Data Curation: J.Z.; Writing—Original Draft: J.Z.; Writing—Review & Editing: R.L. and Z.L.; Supervision: R.L. and Z.L.; Project Administration: R.L.; Funding Acquisition: Z.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Numbers: 72202202 and 72362026), the Yunnan Fundamental Research Project (Grant Numbers: 202301AU070086, 202301AT070458, and 202301BE070001-003), the Yunnan Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning Project (Grant Number: YB202589), the “AI +” Special Research Project of Humanities and Social Sciences at Kunming University of Science and Technology (Grant Number: RZZX202502), and the Academic Excellence Cultivation Project of Kunming University of Science and Technology (Grant Number: JPSC2025010).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in the source code, test instances, and results at https://gitee.com/zhangjinsi_p/glpea.git, accessed on 30 September 2024.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, Z.; Ma, W.; Wu, J.; Wei, K.; Lei, Y.; Lv, G. A study of the performance of submerged arc furnace smelting of industrial silicon. Silicon 2018, 10, 1121–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.C.; Qian, B.; Hu, R.; Chang, L.L.; Yang, J.B. An elitist nondominated sorting hybrid algorithm for multi-objective flexible job-shop scheduling problem with sequence-dependent setups. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2019, 173, 83–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallahi, A.; Shahidi-Zadeh, B.; Niaki, S.T.A. Unrelated parallel batch processing machine scheduling for production systems under carbon reduction policies: NSGA-II and MOGWO metaheuristics. Soft Comput. 2023, 27, 17063–17091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seada, H.; Deb, K. Effect of selection operator on NSGA-III in single, multi, and many-objective optimization. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), Sendai, Japan, 25–28 May 2015; pp. 2915–2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Cheng, R.; Zhang, X.; Su, Y.; Jin, Y. A Strengthened Dominance Relation Considering Convergence and Diversity for Evolutionary Many-Objective Optimization. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2018, 23, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Nehorai, A. Gaussian mixture learning via adaptive hierarchical clustering. Signal Process. 2018, 150, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Pratap, A.; Agarwal, S.; Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2002, 6, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitzler, E.; Laumanns, M.; Thiele, L. SPEA2: Improving the strength Pareto evolutionary algorithm. TIK Rep. 2001, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, H. MOEA/D: A multiobjective evolutionary algorithm based on decomposition. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2008, 11, 712–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaszkiewicz, A. On the performance of multiple-objective genetic local search on the 0/1 knapsack problem: A comparative experiment. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2002, 6, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitzler, E.; Künzli, S. Indicator-based selection in multi-objective search. In International Conference on Parallel Problem Solving from Nature; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 832–842. [Google Scholar]

- Beume, N.; Naujoks, B.; Emmerich, M. SMS-EMOA: Multi-objective selection based on dominated hypervolume. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2007, 181, 1653–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, S.; Bhattacharya, R. Solving multi-objective parallel machine scheduling problem by a modified NSGA-II. Appl. Math. Model. 2013, 37, 6718–6729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, M.F.; Pinto, J.C.E.; Cota, L.P.; Souza, M.J. A mathematical formulation and an NSGA-II algorithm for minimizing the makespan and energy cost under time-of-use electricity price in an unrelated parallel machine scheduling. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2022, 8, e844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hong, H.; Ye, K.; Zhang, G.E.; Jiang, M.; Tan, K.C. Manifold interpolation for large-scale multiobjective optimization via generative adversarial networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 34, 4631–4645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, W.; Doerr, B. Runtime analysis for the NSGA-II: Proving, quantifying, and explaining the inefficiency for many objectives. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2023, 28, 1442–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balekelayi, N.; Woldesellasse, H.; Tesfamariam, S. Comparison of the performance of a surrogate based Gaussian process, NSGA2 and PSO multi-objective optimization of the operation and fuzzy structural reliability of water distribution system: Case study for the City of Asmara, Eritrea. Water Res. Manag. 2022, 36, 6169–6185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossmann, J.; Kamper, M.J.; Hackl, C.M. A Global Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization Framework for Generic Machine Design Using Gaussian Process Regression. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2025, 40, 2384–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebbal, A.; Balesdent, M.; Brevault, L.; Melab, N.; Talbi, E.G. Deep Gaussian process for multi-objective Bayesian optimization. Optim. Eng. 2023, 24, 1809–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Jin, Y.; Gao, K.; Ding, J.; Cheng, R. Surrogate-assisted evolutionary multi-objective optimization of medium-scale problems by random grouping and sparse Gaussian modeling. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 2024, 8, 3263–3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, K.; Fediukov, V.; Dietrich, F.; Neckel, T.; Buse, F.; Bergmann, M.; Bungartz, H.J. Multi-fidelity Gaussian process surrogate modeling for regression problems in physics. Mach. Learn. Sci. Technol. 2024, 5, 045015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Digel, C.; Doppelbauer, M. Uncertainty Quantification-Based Multi-Objective Optimization Design of Electrical Machines Using Probabilistic Metamodels. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2024, 40, 860–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ding, J.; Jiang, M.; Tan, K.C.; Chai, T. Inverse gaussian process modeling for evolutionary dynamic multiobjective optimization. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 52, 11240–11253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Qiu, H.; Gao, L.; Chen, L.; Liu, J. Surrogate-assisted MOEA/D for expensive constrained multi-objective optimization. Inf. Sci. 2023, 639, 119016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Shao, J.; Xiao, J.; Song, W.; Cao, Z. Multi-objective evolutionary algorithm based on RBF network for solving the stochastic vehicle routing problem. Inf. Sci. 2022, 609, 387–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonoda, T.; Nakata, M. Multiple classifiers-assisted evolutionary algorithm based on decomposition for high-dimensional multiobjective problems. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2022, 26, 1581–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Jiang, M.; Hu, W.; Li, S.; Pan, R.; Yen, G.G. An online prediction approach based on incremental support vector machine for dynamic multiobjective optimization. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2021, 26, 690–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, E.; Chen, Z.; Cui, J.; Zhong, H. MOE/RF: A novel phishing detection model based on revised multiobjective evolution optimization algorithm and random forest. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2022, 19, 4461–4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moraes, M.B.; Coelho, G.P. Effects of the random forests hyper-parameters in surrogate models for multi-objective combinatorial optimization: A case study using moea/d-rfts. IEEE Lat. Am. Trans. 2023, 21, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauschild, M.; Pelikan, M. An introduction and survey of estimation of distribution algorithms. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2011, 1, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Liao, F.; Li, Y.; Wang, H. A new prediction strategy for dynamic multi-objective optimization using Gaussian Mixture Model. Inf. Sci. 2021, 580, 331–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, J. Offline and online objective reduction via Gaussian mixture model clustering. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2022, 27, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Hou, Z.; Jiang, S.; Yang, S.; Ruan, G.; Xia, Y.; Liu, Y. Knowledge Transfer With Mixture Model in Dynamic Multi-Objective Optimization. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2025, 29, 1517–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q. MOEA/D-CMA Made Better with (l+l)-CMA-ES. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), Yokohama, Japan, 30 June–5 July 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, S.; Tripathi, S. MODE/CMA-ES: Integrated multi-operator differential evolution technique with CMA-ES. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 176, 113177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, S.; Zhou, A.; Zhang, H. A practical regularity model based evolutionary algorithm for multiobjective optimization. Appl. Soft Comput. 2022, 129, 109614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalita, K.; Ramesh, J.V.N.; Cepova, L.; Pandya, S.B.; Jangir, P.; Abualigah, L. Multi-objective exponential distribution optimizer (MOEDO): A novel math-inspired multi-objective algorithm for global optimization and real-world engineering design problems. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alghamdi, A.S.; Zohdy, M.A. Boosting cuckoo optimization algorithm via Gaussian mixture model for optimal power flow problem in a hybrid power system with solar and wind renewable energies. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero-Peña, E.; Araújo, A.F.R. A new dynamic multi-objective evolutionary algorithm without change detector. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics (SMC), Bari, Italy, 6–9 October 2019; pp. 635–640. [Google Scholar]

- Yazdi, F.; Asadi, S. Enhancing Cardiovascular Disease Diagnosis: The Power of Optimized Ensemble Learning. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 46747–46762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Shi, X. Many-objective evolutionary optimization algorithm based on the Gaussian mixture models. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Applied Mathematics, Modelling, and Intelligent Computing (CAMMIC 2025), Shanghai, China, 21–23 March 2025; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2025; Volume 13644, pp. 457–462. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulghani, A.M.; Abdullah, A.; Rahiman, A.R.; Abdul Hamid, N.A.W.; Akram, B.O. Network-Aware Gaussian Mixture Models for Multi-Objective SD-WAN Controller Placement. Electronics 2025, 14, 3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachechi, C.; Rollo, F.; Po, L. Detection and classification of sensor anomalies for simulating urban traffic scenarios. Clust. Comput. 2022, 25, 2793–2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmeir, C.; Benítez, J.M. On the use of cross-validation for time series predictor evaluation. Inf. Sci. 2012, 191, 192–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Box, G. Box and Jenkins: Time series analysis, forecasting and control. In A Very British Affair: Six Britons and the Development of Time Series Analysis During the 20th Century; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 2013; pp. 161–215. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Ding, Y.; Cheng, J.C.; Jiang, F.; Gan, V.J.; Xu, Z. A Lag-FLSTM deep learning network based on Bayesian Optimization for multi-sequential-variant PM2.5 prediction. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 60, 102237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Fang, D.; Wang, X.; Wei, W.; Damaševičius, R.; Scherer, R.; Woźniak, M. Prediction of streamflow based on dynamic sliding window LSTM. Water 2020, 12, 3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köksoy, O. Multiresponse robust design: Mean square error (MSE) criterion. Appl. Math. Comput. 2006, 175, 1716–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Applegate, R.A.; Ballentine, C.; Gross, H.; Sarver, E.J.; Sarver, C.A. Visual acuity as a function of Zernike mode and level of root mean square error. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2003, 80, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sammut, C.; Webb, G.I. Mean absolute error. Encycl. Mach. Learn. 2010, 652, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, L.P. Generalized Method of Moments Estimation. In The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempster, A.P.; Laird, N.M.; Rubin, D.B. Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1977, 39, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, B.V.; Jehan, M.M.L. Differential evolution for multi-objective optimization. In Proceedings of the 2003 Congress on Evolutionary Computation, Canberra, Australia, 8–12 December 2003; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2003; Volume 4, pp. 2696–2703. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann. Stat. 1978, 6, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riquelme, N.; Von Lücken, C.; Baran, B. Performance metrics in multi-objective optimization. In Proceedings of the 2015 Latin American Computing Conference (CLEI), Arequipa, Peru, 19–23 October 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Woolson, R.F. Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Wiley Encycl. Clin. Trials 2007, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).