Abstract

Current private comparison schemes primarily focus on comparing single secret integers using quantum technologies, while the area of private array content comparison remains relatively unexplored. To bridge this gap, we introduce a quantum private array content comparison (QPACC) scheme based on multi-qubit swap test. This scheme integrates rotation operation, quantum homomorphic encryption (QHE), and multi-qubit swap test to facilitate the equality comparison of array contents while ensuring their confidentiality. In our approach, participants encode their array elements into the phases of quantum states using rotation operations, which are then encrypted via QHE. These encrypted quantum states are sent to a semi-honest third party (TP) who decrypts the encoded quantum states and computes the modulus squared sum of the inner products of these decoded quantum states using the multi-qubit swap test, thereby determining the equality relationship of the array contents. To verify the feasibility of the proposed scheme, we conduct a case simulation using IBM Qiskit. Security analysis indicates that the proposed scheme is resistant to quantum attacks (including intercept-resend, entangle-measure, and quantum Trojan horse attacks) from outsider eavesdroppers and attempts by curious participants.

Keywords:

quantum private array content comparison; rotation operation; quantum homomorphic encryption; multi-qubit swap test; quantum cryptography MSC:

81P94; 81P65

1. Introduction

Quantum cryptography has emerged as a cornerstone of secure communication in the post-quantum era, leveraging fundamental principles of quantum mechanics such as superposition and entanglement to achieve security levels that are potentially unattainable by classical cryptographic protocols reliant on computational complexity []. Since the pioneering work of the BB84 quantum key distribution (QKD) protocol [], the field has expanded rapidly, giving rise to a diverse suite of quantum cryptographic primitives including quantum key agreement [,,,], quantum secret sharing [,,], quantum summation [,], and quantum private set intersection [,,].

A pivotal subfield within cryptography is secure multiparty computation (MPC) [], which enables multiple parties to jointly compute a function over their private inputs while preserving the confidentiality of those inputs. The classic “millionaires’ problem” [] is a quintessential example, allowing two parties to compare their wealth without disclosure. Subsequent work extended this to equality checks [], a fundamental building block for more complex protocols. However, traditional solutions based on computational hardness assumptions are critically threatened by the advent of quantum algorithms, notably Shor algorithm [] and Grover algorithm []. This vulnerability has catalyzed the development of quantum private comparison (QPC) protocols, which integrate classical comparison tasks with the inherent security of quantum mechanics.

The original QPC framework, proposed by Yang and Wen [], leverages the quantum correlations of EPR pairs and the security of a one-way hash function to verify that two classical integers held by different parties are equal. This seminal work catalyzed extensive research, leading to a diverse ecosystem of QPC protocols designed to enhance both functionality and security. Subsequent developments have explored a wide range of quantum state encodings, including single photons [,,], various entangled states [,,,,,,], cluster states [,], and d-level quantum systems [,,], each offering distinct advantages. Moving beyond simple equality comparison, the scope of QPC has been expanded to include more complex comparisons. Wu and Zhao [] extended the paradigm to d-level systems for comparing input sizes, a capability formalized as quantum private magnitude comparison (QPMC) by Lang [] to identify the maximum of two private inputs. Addressing scalability, Huang et al. [] later demonstrated that the swap test could be employed for the direct comparison of single-qubit states. Concurrently, to address the current limitations of quantum technology, the paradigm of semi-quantum private comparison (SQPC) [,,,,] has emerged. SQPC protocols achieve the desired comparison functionality while relaxing the quantum requirements for participants, thereby alleviating resource constraints and reducing the high costs associated with full quantum capabilities.

Despite the considerable progress, a notable gap persists in the literature. The majority of existing QPC protocols are fundamentally designed for comparing individual integers, focusing primarily on determining equality or magnitude relationships. The more complex task of privately comparing the content of entire arrays remains relatively unexplored. The design of a secure quantum private array content comparison (QPACC) protocol poses a distinct challenge, as it requires the coordinated, confidential comparison of multiple elements without leaking information about the individual array contents.

To address this gap, we propose a QPACC scheme based on the multi-qubit swap test. Our work makes several key contributions:

- (1)

- We introduce a QPACC scheme capable of securely determining the equality of two arrays, moving beyond the limitation of single-integer comparisons that characterizes existing schemes.

- (2)

- The scheme is constructed using near-term feasible quantum technologies, including single-qubit states as quantum resources, rotation operations for encoding, quantum homomorphic encryption (QHE) for encrypting the encoded quantum states, and the multi-qubit swap test for comparison, avoiding the need for complex operations like entanglement swapping or high-dimensional quantum state preparation.

- (3)

- The protocol incorporates decoy photons for eavesdropping detection and rotation operations to obscure the encoded data, thereby providing robustness against external attacks and the curiosity of internal participants.

- (4)

- We construct a quantum circuit for a concrete case of the proposed scheme and perform simulations on the IBM Qiskit, providing empirical validation of its feasibility and correctness.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the necessary preliminaries, including the rotation operation, QHE, and the multi-qubit swap test. Section 3 details the step-by-step design of our proposed scheme. Section 4 presents the simulation experiments and results. A comprehensive analysis of the protocol’s correctness, security and fairness is provided in Section 5. Discussion is given in Section 6, and finally, Section 7 concludes the paper.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Rotation Operation

The rotation operation [] is a unitary operator around the Y-axis of the Bloch sphere, denoted as . This operator is defined by the following matrix:

As a unitary operation, satisfies the critical property , where I is the identity matrix and . This operation can be used to map classical integers to the rotation angles of a single qubit. For example, the number 6 can be converted into the angle , which serves as a rotation angle that can be encoded into the quantum basis states . The transformation of this process is given by

This rotation operation rotates the states on the Bloch sphere, transforming it from a definite basis state into a superposition state.

2.2. Quantum Homomorphic Encryption (QHE)

The QHE scheme [] on single qubits is built upon the following fundamental single-qubit operators:

The set of permitted quantum operations for this QHE scheme is defined as .

Let denote the quantum plaintext and denote the quantum ciphertext. The QHE scheme is as follows:

- Key Generation (KeyGen): Randomly select two classical bits to form the secret key.

- Encryption (Enc): Compute the quantum ciphertext by applying single-qubit operators to the quantum plaintext based on the secret key: . This encryption method is proven theoretically secure in Ref. [].

- Decryption (Dec): Recover the quantum plaintext by applying again single-qubit operators to the quantum ciphertext based on the secret key: .

- Evaluation (Eval): To apply a permitted operation homomorphically to the quantum ciphertext , the evaluator performs a transformed rotation , where the angle is adjusted based on the secret key: . This transformation satisfies the homomorphic property: . Consequently, the evaluation on the ciphertext is equivalent to performing the desired operation on the plaintext, followed by encryption. The output state is given by: . Crucially, this evaluation is performed directly on the ciphertext without any decryption.

In summary, this QHE scheme allows any unitary transformation in the set to be executed on encrypted data, with the evaluator requiring only a simple, key-dependent adjustment of the rotation angle.

2.3. Multi-Qubit Swap Test

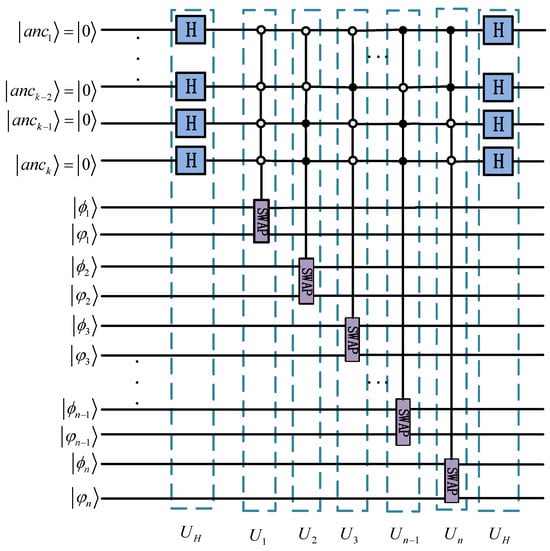

The multi-qubit swap test [] is a quantum algorithmic primitive that generalizes the standard two-state swap test. Its purpose is to evaluate the collective similarity between n pairs of quantum states. Specifically, for n pairs of qubits , this provides an estimate of the modulus squared sum of their inner products, . The quantum circuit of the multi-qubit swap test, illustrated in Figure 1, requires k ancillary qubits, where .

Figure 1.

The quantum circuit of multi-qubit swap test.

The operation of the quantum circuit is governed by a sequence of unitary transformations:

The overall unitary operation for the circuit is defined as .

After applying the unitary operation U to the initial states, the system evolves into a complex superposition. The probability that the highest-order ancilla qubit, , is measured in the state is given by

This relationship can be rearranged to solve for the target metric, yielding:

Therefore, by preparing the quantum circuit, executing it multiple times to estimate the probability , and applying the formula above, one can directly compute the sum of the squared modulus overlaps for all n qubit pairs.

3. The Proposed QPACC Scheme

This section details the design of our proposed QPACC scheme. This protocol allows two parties, Alice and Bob, to verify the equality of their private arrays, and , without disclosing any element. The arrays are of equal length n, with each element constrained to the set . This process is facilitated by a semi-honest TP, who assists in the computation without colluding with either participant and without learning the arrays’ contents.

The scheme is designed to satisfy the following fundamental properties:

- Correctness: If all participants adhere to the protocol, TP will always output the correct comparison result.

- Security: The proposed scheme protects the secrecy of the input arrays X and Y from two primary threat models: external attacks on the quantum channel and internal curiosity from all other parties, even the TP.

- Fairness: Both Alice and Bob receive the final result simultaneously, preventing either from gaining an advantage.

Additionally, the scheme operates under the following standard assumptions:

- All quantum channels are assumed to be lossless and noiseless. In a practical implementation, the effects of noise and loss can be mitigated through quantum error-correcting codes [].

- All classical channels are authenticated to ensure integrity and prevent man-in-the-middle attacks.

- Prior to the protocol’s execution, Alice and Bob have securely established a shared secret key, , using an unconditionally secure QKD protocol (e.g., the BB84 protocol []).

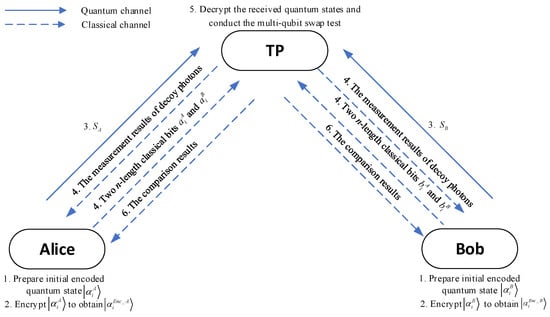

The scheme proceeds according to the following steps and its diagram is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The diagram of the proposed scheme.

Step 1. Prepare initial encoded quantum states

Alice and Bob convert each i-th element in arrays X and Y into angles and . Specially, if or , they set the angles to or , respectively. They perform the rotation operations and on the states to encode the array elements into quantum states, respectively. These encoded quantum states are denoted as and , respectively.

Step 2. Encrypt the encoded quantum states

Alice (Bob) randomly selects two n-length classical bits and ( and ) to form two secret keys. They compute the encrypted quantum states () by applying single-qubit operators to the encoded quantum states and based on the chosen secret keys. This can be expressed as:

Step 3. Insert decoy photons into encrypted quantum states

To prevent eavesdropping, Alice (Bob) random selects decoy photons chosen from four nonorthogonal states: and inserts them into at random positions. The resulting quantum states composed a quantum sequence, denoted as . Then, Alice (Bob) records the chosen nonorthogonal states and positions of these decoy photons. Finally, Alice (Bob) sends to the TP via the quantum channel for the next eavesdropping detection.

Step 4. Eavesdropping detection between Alice (Bob) and the TP

Upon receiving and , the TP sends a confirmation to Alice and Bob, who then publicly announce the corresponding positions and measurement bases of the inserted decoy photons. Specifically, if the chosen decoy photons are in the states or , the measurement base is the Z basis. Otherwise, the measurement base is the X basis. Next, the TP measures these decoy photons in and using the announced measurement bases to obtain the measurement results. These results are sent back to Alice and Bob to check whether the quantum sequences have been transmitted securely. Alice and Bob calculate the error rate by comparing the measurement results with the initially prepared decoy photons. If the error rate is higher than a threshold, approximately between 2% and 8.9% depending on the channel conditions (e.g., distance and noise) [], the quantum channel is deemed insecure, and they will restart the protocol. Otherwise, the transmission of the quantum sequence is considered secure, and Alice and Bob will announce the secret keys to the TP for decrypting the encrypted quantum states.

Step 5. Decrypt the quantum states and conduct the multi-qubit swap test

The TP removes the decoy photons in and to recover the encrypted quantum states and . Using the secret keys, it then recovers the encoded quantum states and by applying again single-qubit operators to (). This is expressed as:

Next, the TP conducts the multi-qubit swap test on all qubit pairs and , measuring the highest-order ancilla qubit to obtain a measurement result.

Step 6. Perform multiple iterations and announce the comparison result

By conducting Steps 1 to 5 times (where depends on the desired accuracy of the multi-qubit swap test), the TP records the measurement results of each highest-order ancilla qubit . The occurrence of the state in any single iteration conclusively demonstrates a difference between arrays X and Y. Conversely, the consistent observation of across all iterations certifies their equivalence. The TP is responsible for announcing the conclusive result to both parties.

4. Simulation Experiment

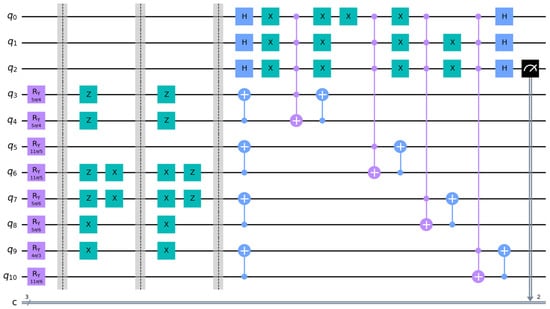

We assume that Alice has her array and Bob has his array . Alice and Bob intend to determine whether the two arrays are equal. Additionally, it is given that Alice and Bob have securely established a shared secret key via a QKD protocol. For simplification, the eavesdropping detection is treated as an independent procedure, not considered in the simulation experiment.

To prepare the initial encoded quantum states, Alice performs the rotation operations , , and on the states . The chosen secret keys for Alice are and .

Similarly, to prepare the initial encoded quantum states, Bob applies the rotation operations , , and to the states . The chosen secret keys for Bob are and .

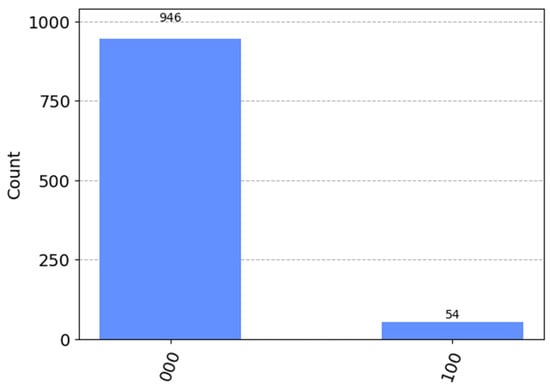

We evaluated the practical viability of our protocol by implementing it as a quantum circuit and conducting simulations via IBM Qiskit (version 0.44.1) on Python (version 3.11.4) running on Windows. It is important to note that the following simulation is conducted 1000 times. The corresponding quantum circuit to evaluate the equality of the arrays and is shown in Figure 3, and its measurement results are presented in Figure 4. In Figure 3, quantum registers q[0] to q[2] serve as ancilla qubits, while registers q[3] to q[10] are used to encode the array elements and subsequently encrypt the resulting quantum states. A multi-qubit swap test is performed, which includes a Hadamard gate (H) on the control ancilla qubits, q[0]–q[2]. The outcome of the protocol is obtained by measuring the ancilla qubit q[2]. In Figure 4, the measurement outcome is a bitstring representing the computational basis state of the ancilla qubits q[2], q[1], and q[0]. A result of ‘000’ indicates the state , meaning all three ancilla qubits are in the state. Conversely, a result of ‘100’ corresponds to the state , signifying that q[2] is in state while q[1] and q[0] remain in state .

Figure 3.

The quantum circuit for determining the equality of the arrays X and Y.

Figure 4.

The measurement results.

Based on the measurement results presented in Figure 4, where the ancilla qubit q[2] is measured in the |1⟩ state, we conclude that the scheme’s output is correct and that the two input arrays are not identical.

5. Analysis

5.1. Correctness

Let denote the probability that the ancilla qubit is measured in the state when conducting the multi-qubit swap test on all qubit pairs and . The probability that can be expressed as follows:

Based on Equation (14), we conclude that if and only if all . Thus, array equivalence is confirmed only if all ancilla qubits are measured in the state; the detection of a state in any one of them immediately establishes a mismatch.

5.2. Security Analysis

The proposed QPACC protocol is designed to withstand security threats originating from two primary sources: external eavesdroppers and honest-but-curious participants. External adversaries, such as Eve, may attempt to intercept quantum transmissions or deploy quantum Trojan horse attacks, while participants might seek to deduce private inputs from intermediate information. To counter these threats, the protocol integrates decoy photon technology for eavesdropping detection and employs cryptographic keys to encrypt quantum states. The following analysis will demonstrate that these measures effectively preserve the confidentiality of the private arrays X and Y against all considered attacks.

5.2.1. External Attacks

A malicious adversary, Eve, may employ various strategies, such as intercept-resend [,], entangle-measure [], and quantum Trojan horse attacks [,], in an attempt to compromise the confidentiality of the participants’ private inputs. To counter these threats, the scheme incorporates a robust security framework. The sensitive information is encoded into single-photon states, which are further protected by pre-shared secret keys. The following analysis details the protocol’s robustness against these specific attack strategies.

Case I. Intercept-resend attack

In this attack scenario, an external eavesdropper, Eve, intercepts the encoded quantum sequences and during their transmission from Alice and Bob to the TP. She measures the intercepted qubits using a randomly chosen basis (Z or X) and, based on the results, prepares and forwards two counterfeit sequences to the TP. The security against this attack stems from the indistinguishable nature of the decoy photons, which are randomly inserted within the sequences from the set . Since Eve has no knowledge of their positions or bases, her random measurements inevitably disturb the decoy states. This disturbance introduces detectable errors during the subsequent eavesdropping check conducted by the legitimate parties.

The detection probability can be quantified as follows. Consider a decoy photon in the state. If Eve measures it in the correct X-basis, she causes no disturbance. However, if she chooses the incorrect Z-basis, she has a 50% probability of obtaining an incorrect result, thus introducing a detectable error. Given that Eve selects either basis with a probability of 1/2, the overall probability that she measures a single decoy photon without introducing an error is . Consequently, for decoy photons, the probability that Eve evades detection diminishes to . Therefore, the probability of her attack being discovered is , which converges to 1 as increases. This guarantees that any intercept-resend attempt will be detected with near certainty, preventing Eve from extracting any meaningful information about the private arrays and .

Case II. Entangle-measure attack

In this attack scenario, an external eavesdropper, Eve, intercepts the encoded quantum sequences and during their transmission from Alice and Bob to the TP. She then applies a unitary operation to entangle each intercepted qubit with an ancillary qubit in her possession, aiming to extract information by subsequently measuring this ancillary state.

The unitary interaction on the basis states and the ancillary state is described by:

The coefficients satisfy the normalization conditions and .

For the attack to remain undetected, the interaction must not introduce errors when the decoy photons are measured by the legitimate parties. This imperfection detection imposes strict constraints on the unitary operation. Specifically, to pass the eavesdropping check without inducing a measurable disturbance, the coefficients must satisfy and . Under these constraints, the evolution of the decoy states simplifies to the following form:

This result demonstrates that no meaningful entanglement is created between the decoy qubits and Eve’s ancillary qubit. Consequently, her measurements on the ancilla yield no information about the qubit’s state, rendering the attack futile.

Furthermore, even if Eve were to direct this attack at the encoded information qubits (), her success is precluded. The final state after the interaction depends on the secret parameters , and , , and . Since Eve has no knowledge of these parameters, she cannot deduce the participants’ private inputs from her ancillary measurements. The protocol’s security is thus assured, as any attempt to glean information via an entangle-measure attack will either be detected through decoy state analysis or will fail due to a lack of essential secret parameters.

Case III. Quantum Trojan horse attacks

Quantum Trojan horse attacks, which include the delay-photon and invisible-photon attacks, represent a class of threats that typically exploit bidirectional quantum communication channels. The security of the proposed protocol against such attacks is inherent in its fundamental architecture. The protocol is inherently resilient to these attacks, as the quantum communication is exclusively one-way (from Alice and Bob to the TP), a design that eliminates the possibility of the two-way interaction these threats require. This structural characteristic inherently negates the primary vector for quantum Trojan horse attacks.

In summary, by employing decoy photon technology to counter external eavesdropping strategies, the protocol effectively safeguards the private arrays and .

5.2.2. Participant Attacks

Insider threats from participants pose a more significant security challenge than external attacks, as honest-but-curious participants possess legitimate access to intermediate computational data and can leverage this knowledge to infer private inputs. The following analysis demonstrates the protocol’s resilience against such attacks, considering potential curious behaviour from any of the parties involved: TP, Alice, or Bob.

Case I. Security against the semi-honest TP

Within the security model, the TP is assumed to be semi-honest; it faithfully executes the protocol’s procedures but may attempt to infer the private arrays A and B from the information it legitimately acquires. The TP’s vantage point includes access to the encoded quantum states and , which are prepared by applying the rotation operations and to the states . The angles and are encoded from the array elements and , respectively. The critical security mechanism lies in the pre-shared secret angle , known exclusively to Alice and Bob. From the TP’s perspective, the processed qubits, denoted as and , are equivalent to states rotated by a single, composite angle. Without knowledge of the component , the TP faces the fundamental principle of quantum indeterminacy; it cannot resolve the individual contributions of and from the superposition. Consequently, the unknown quantum states remain indistinguishable, and the private arrays X and are provably concealed from the TP, ensuring security against this semi-honest adversary.

Case II. Security against honest-but-curious Alice or Bob

The protocol ensures identical roles between participants Alice and Bob. To illustrate, consider a scenario where Alice, while adhering to the protocol, attempts to deduce Bob’s private array . Each element of Bob’s array is encoded into a rotation angle . The corresponding quantum state is prepared by applying the unitary operation to the state , where is a pre-shared secret key. Subsequently, this state is encrypted using single-qubit operators determined by Bob’s secret keys and , resulting in the state . Decoy photons are inserted into the final sequence before its transmission to the TP.

While Alice could intercept , her ability to gain information is nullified by multiple security layers. First, any attempt to intercept and resend the sequence would be detected during the eavesdropping detection process. Second, even if she accessed the sequence by conducting intercept-resend attacks, the encrypted states remain indistinguishable without knowledge of the encryption keys and , which are only revealed after a successful security verification, a condition Alice cannot satisfy without causing detectable disturbances. Consequently, Alice faces the fundamental barrier of quantum indeterminacy and cannot resolve to deduce array . An equivalent analysis applies to Bob’s attempts to ascertain array , confirming the protocol’s resilience against honest-but-curious Alice or Bob.

To conclude, the protocol guarantees the confidentiality of the private arrays against honest-but-curious adversaries, encompassing all participating entities: the TP, Alice, and Bob.

5.3. Fairness

The fairness is ensured through the involvement of a semi-honest TP. The TP performs measurements on the highest-order ancilla qubit of the multi-qubit swap test to determine the equality relationship between arrays X and Y, and subsequently announces the result simultaneously to both the parties. This process of simultaneous disclosure prevents either party from gaining precedence in learning the outcome, thereby upholding strict fairness throughout the protocol execution.

6. Discussion

A comparative analysis between the proposed protocol and existing QPC schemes is summarized in Table 1, evaluating aspects such as quantum resource, quantum operations, quantum communication method, quantum measurement for users, quantum measurement for TP, and the scope of comparison.

Table 1.

A comparative between our protocol and existing QPC schemes.

As illustrated, our scheme exhibits the following distinct advantages:

- (1)

- It extends comparison capability from single integer to full array, improving functional scalability for practical applications.

- (2)

- In contrast to protocols that rely on complex multi-qubit or high-dimensional states, our scheme utilizes only single-photon states, single-qubit rotations, and the multi-qubit swap test. All of these components are compatible with current quantum technology, which significantly enhances its experimental feasibility.

- (3)

- The substitution of Bell-basis measurements with single-particle measurements streamlines the measurement process, thereby lowering the experimental overhead.

The operational range of the proposed scheme is limited to array elements in {0, 1, 2, …, 9}, a constraint imposed to safeguard against accuracy degradation from large numerical values. Consequently, a salient application is in data integrity checks. By quantifying data block features into arrays within this bounded set, the scheme can be deployed to verify error-free data transmission or to audit the consistency of backup data against its original source.

7. Conclusions

This paper presents a quantum private array content comparison (QPACC) scheme based on a multi-qubit swap test framework. The protocol integrates rotation operations for encoding array elements into quantum states, QHE for state protection, and a multi-qubit swap test executed by the TP acting as a cloud processor. Through this architecture, the TP can compute the modulus squared sum of inner products between the decoded quantum states to determine array equality without learning the actual content of the arrays. Simulations conducted via IBM Qiskit confirm the scheme’s practical viability. The protocol ensures security through multiple layers: decoy photon technology safeguards against external eavesdropping, while the combined use of rotation operations and QHE protects against curious participants attempting to infer private inputs. Furthermore, fairness is guaranteed by the TP’s simultaneous announcement of the comparison result. Compared to existing quantum private comparison schemes limited to single integers, the proposed approach enables efficient array comparisons, offering enhanced scalability and practical applicability. By utilizing single photons and avoiding entanglement swapping, the protocol reduces operational complexity and aligns with near-term quantum technological capabilities. Future research will explore semi-quantum implementations to further minimize quantum resource requirements while preserving security guarantees.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H. and S.Z.; methodology, M.H. and S.Z.; Writing—original draft, M.H.; writing—review and editing, Y.W. and S.Z.; supervision, S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research Project of Key R&D Programs in Tibet Autonomous Region (No. XZ202501ZY0094), the General Program of Sichuan Science and Technology & Education Joint Fund (No.2025NSFSC2098), the Key Research and Development Project of Chengdu (No. 2023-XT00-00002-GX), the Key Research and Development Support Program Project of Chengdu (No. 2024-YF05-01227-SN), the Open Fund of Network and Data Security Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province (Grant No. NDS2024-1).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gisin, N.; Ribordy, G.; Tittel, W.; Zbinden, H. Quantum cryptography. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2002, 74, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, C.H.; Brassard, G. Quantum cryptography: Public key distribution and coin tossing. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2014, 560, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Bian, Y.; Li, Z.; Yu, S.; Guo, H. Continuous-variable quantum key distribution system: Past, present, and future. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2024, 11, 011318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; van Leent, T.; Redeker, K.; Garthoff, R.; Schwonnek, R.; Fertig, F.; Eppelt, S.; Rosenfeld, W.; Scarani, V.; Lim, C.C.; et al. A device-independent quantum key distribution system for distant users. Nature 2022, 607, 687–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, L.; Tan, H.; Lu, Y.; Liao, S.K.; Huang, J.; Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Mao, H.K.; Yan, B.; et al. High-rate quantum key distribution exceeding 110 Mb s–1. Nat. Photonics 2023, 17, 416–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadlinger, D.P.; Drmota, P.; Nichol, B.C.; Araneda, G.; Main, D.; Srinivas, R.; Lucas, D.M.; Ballance, C.J.; Ivanov, K.; Tan, E.Z.; et al. Experimental quantum key distribution certified by Bell’s theorem. Nature 2022, 607, 682–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, A.; Cao, X.Y.; Wang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Gu, J.; Liu, W.B.; Weng, C.X.; Yin, H.L.; Chen, Z.B. Experimental quantum secret sharing based on phase encoding of coherent states. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 2023, 66, 260311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhong, W.; Du, M.M.; Shen, S.T.; Li, X.Y.; Zhang, A.L.; Zhou, L.; Sheng, Y.B. Device-independent quantum secret sharing with noise preprocessing and postselection. Phys. Rev. A 2024, 110, 042403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Cheng, J.; Ma, J.; Zhao, D.; Yan, Z.; Jia, X.; Xie, C.; Peng, K. Efficient and secure quantum secret sharing for eight users. Phys. Rev. Res. 2024, 6, 033036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Long, Y.; Li, Q. Quantum summation using d-level entanglement swapping. Quantum Inf. Process. 2021, 20, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.H.; Liu, B.; Zhang, M. Measurement-device-independent quantum secure multiparty summation. Quantum Inf. Process. 2022, 21, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, S. Quantum Private Set Intersection Scheme Based on Bell States. Axioms 2025, 14, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, S. Quantum multi-party private set intersection using single photons. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2024, 649, 129974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.D.; Zheng, L.Q.; Yu, K.; Lin, S. Authenticated Multi-Party Quantum Private Set Intersection with Single Particles. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, Y. Secure multiparty computation. Commun. ACM 2020, 64, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, A.C. Protocols for secure computations. In Proceedings of 23rd IEEE Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (FOCS’ 82), Chicago, IL, USA, 3–5 November 1982; p. 160. [Google Scholar]

- Boudot, F.; Schoenmakers, B.; Traore, J. A fair and efficient solution to the socialist millionaires’ problem. Discret. Appl. Math. 2001, 111, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shor, P.W. Polynomial-time algorithms for prime factorization and discrete logarithms on a quantum computer. SIAM Rev. 1999, 41, 303–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, L.K. Quantum mechanics helps in searching for a needle in a haystack. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 79, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.G.; Wen, Q.Y. An efficient two-party quantum private comparison protocol with decoy photons and two-photon entanglement. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 2009, 42, 055305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.; Wu, Y. Single-photon-based quantum secure protocol for the socialist millionaires’ problem. Front. Phys. 2024, 12, 1364140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, T.Y.; Che, B.C.; Dou, Z.; Chen, X.B.; Lai, Y.P.; Li, J. Efficient quantum private comparison protocol utilizing single photons and rotational encryption. Chin. Phys. B 2022, 31, 060307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Xiao, D.; Huang, W.; Jia, H.Y.; Song, T.T. Quantum private comparison employing single-photon interference. Quantum Inf. Process. 2017, 16, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q. Quantum private comparison with six-particle maximally entangled states. Mod. Phys. Lett. A 2022, 37, 2250149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.X.; Zhang, H.G.; Fan, P.R. Two-party quantum private comparison protocol with maximally entangled seven-qubit state. Mod. Phys. Lett. A 2019, 34, 1950229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, P.; Rahman, A.U.; Ji, Z.; Ji, X.; Hao, Z.; Zhang, H. Two-party quantum private comparison based on eight-qubit entangled state. Mod. Phys. Lett. A 2022, 37, 2250026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H. Quantum private comparison protocols with a number of multi-particle entangled states. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 44613–44621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, T.Y.; Ji, Z.X. Two-party quantum private comparison with five-qubit entangled states. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 2017, 56, 1517–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, S.B.; Chang, Y.; Hou, M.; Cheng, W. Efficient quantum private comparison based on entanglement swapping of bell states. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 2021, 60, 3783–3796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianni, J.; Qu, Z. New quantum private comparison using hyperentangled ghz state. J. Quantum Comput. 2021, 3, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Chen, X.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Li, J. Efficient quantum private comparison protocol based on the entanglement swapping between four-qubit cluster state and extended Bell state. Quantum Inf. Process. 2019, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.; Wu, Y. Quantum Private Comparison Protocol with Cluster States. Axioms 2025, 14, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Sun, Y.; Liu, X.F.; Yao, Z.Q. Quantum private comparison protocol with d-dimensional Bell states. Quantum Inf Process 2013, 12, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.Z.; Gao, F.; Qin, S.J.; Zhang, J.; Wen, Q.Y. Quantum private comparison protocol based on entanglement swapping of d-level Bell states. Quantum Inf. Process. 2013, 12, 2793–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, T.Y.; Hu, J.L. Multi-party quantum private comparison based on entanglement swapping of Bell entangled states within d-level quantum system. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 2021, 60, 1471–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.Q.; Zhao, Y.X. Quantum private comparison of size using d-level Bell states with a semi-honest third party. Quantum Inf. Process. 2021, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, Y.F. Quantum private magnitude comparison. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 2022, 61, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Chang, Y.; Cheng, W.; Hou, M.; Zhang, S.B. Quantum private comparison of arbitrary single qubit states based on swap test. Chin. Phys. B 2022, 31, 040303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, X.B.; Ye, C.Q.; Li, C.Y.; Hou, Y.Y. An efficient semi-quantum private comparison without pre-shared keys. Quantum Inf. Process. 2021, 20, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.Z. Semi-quantum private comparison based on Bell states. Quantum Inf. Process. 2020, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.H.; Li, M.L.; Cao, H.; Wang, B. Novel semi-quantum private comparison protocol with Bell states. Laser Phys. Lett. 2024, 21, 055209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.R.; Chen, Z.Y.; Liu, Y.Y.; Gong, L.H. Multi-party semi-quantum private comparison protocol of size relation with d-level GHZ states. Adv. Quantum Technol. 2025, 8, 2400530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.H.; Ye, Z.J.; Liu, C.; Zhou, S. One-way semi-quantum private comparison protocol without pre-shared keys based on unitary operations. Laser Phys. Lett. 2024, 21, 035207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, S.; Khan, M.K. QF2PM: Quantum-Secure Fine-Grained Privacy-Preserving Profile Matching for Mobile Social Networks. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, S.; Chang, Y.; Yang, F.; Hou, M.; Cheng, W. Quantum secure direct communication based on quantum homomorphic encryption. Mod. Phys. Lett. A 2021, 36, 2150263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M. Symmetric quantum fully homomorphic encryption with perfect security. Quantum Inf. Process. 2013, 12, 3675–3687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wang, B. Quantum neural networks model based on swap test and phase estimation. Neural Netw. 2020, 130, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saiyed, A.I. Quantum Error Correction in Cryptographic Applications: Ensuring Robustness against Quantum Noise and Attacks. Acad. Nexus J. 2025, 4. Available online: http://academianexusjournal.com/index.php/anj/article/view/16 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Tsai, C.W.; Hwang, T. Deterministic quantum communication using the symmetric W state. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 2013, 56, 1903–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozubov, A.; Gaidash, A.; Miroshnichenko, G. Quantum control attack: Towards joint estimation of protocol and hardware loopholes. Phys. Rev. A 2021, 104, 022603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, S.B.; Chang, Y.; Qiu, C.; Liu, D.M.; Hou, M. Quantum key agreement protocol based on quantum search algorithm. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 2021, 60, 838–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Xin, X.; Li, C.; Li, F. Security analysis of the semi-quantum secret-sharing protocol of specific bits and its improvement. Quantum Inf. Process. 2024, 23, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zheng, B.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, H.B.; Wei, K. Improved security bounds against the Trojan-horse attack in decoy-state quantum key distribution. Quantum Inf. Process. 2024, 23, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.J.; Liu, J.Y.; Zhou, X.Y.; Zhang, C.H.; Li, J.; Wang, Q. Improved finite-key security analysis of measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution against a trojan-horse attack. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2023, 19, 044022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).