1. Introduction

With the rapid development of hyperspectral imaging technology, hyperspectral remote sensing images have been widely applied in environmental monitoring [

1], target detection [

2], mineral exploration [

3], and other fields. However, due to the insufficient spatial resolution and the spatial complexity of the distribution of materials, there are numerous mixed pixels in hyperspectral images (HSIs) [

4]. The existence of mixed pixels hinders the refined application of HSIs [

5]. To address the spectral mixing problem and effectively identify the spectral components and their proportions in each mixed pixel, hyperspectral unmixing (HU) technology has emerged and become an important step in the preprocessing of hyperspectral images. Its task is to estimate the spectral reflectance of pure materials (i.e., endmembers) and their proportion (i.e., fractional abundances) from the mixed pixels [

6].

Up to now, based on different spectral mixing mechanisms, researchers have proposed the Linear Mixing Model (LMM) [

7] and the Nonlinear Mixing Model (NLMM) [

8]. The LMM assumes that the mixing of materials occurs at the macroscopic scale, and the incident solar photons interact with only one substance. Attributed to its computational efficiency, analytical tractability, and intuitive physical interpretability, the LMM has been extensively utilized in HU. Therefore, this paper carries out the unmixing research based on the LMM.

In the past few decades, researchers have proposed lots of unmixing methods based on the LMM, which can generally be classified into geometrical, statistical, sparse regression, and emerging methods (such as methods based on Non-negative Tensor Factorization (NTF) and methods based on Deep Learning (DL)). Specifically, geometrical methods are rooted in convex geometry principles and are bifurcated into two primary categories: pure pixel assumption frameworks and non-pure pixel assumption frameworks. Pure pixel methods demand the presence of at least one pure spectral pixel for each endmember within the HSI, where endmembers are identified as the vertices of the convex hull (simplex) in the HSI feature space. The representative algorithms include subspace projection [

9] and maximum simplex volume maximization [

10]. In contrast, non-pure pixel methods are anchored in the minimum simplex theory [

11,

12], where endmembers are theoretically estimated by solving for the optimal simplex vertices. This attribute enables the minimum simplex approach to effectively address scenarios with highly mixed spectral data, where conventional pure pixel methods often encounter limitations.

Statistical methods are based on probability and mathematical statistics theory and do not require the pure pixel assumption. The NMF method is the most representative method among them. NMF decomposes the non-negative hyperspectral data matrix into the product of a basis matrix and its coefficient matrix, corresponding to endmembers and abundances, respectively [

13,

14,

15,

16]. However, since the NMF model is based on mathematical statistics and optimization, it may obtain virtual endmembers without physical meaning. Moreover, due to the non-convexity of the NMF model, it cannot obtain the global optimal solution. The Non-negative Tensor Factorization (NTF) originates from the tensor decomposition theory and can be divided into four types according to different decomposition methods: Canonical Polyadic Decomposition (CPD) [

17], Tucker Decomposition (TD) [

18], Block Term Decomposition (BTD) [

19,

20,

21], and Matrix–Vector NTF (MV-NTF). MV-NTF decomposes a tensor into the outer product form of a matrix and a vector [

22]. Due to its clear physical meaning, it is widely used in unmixing. DL methods have strong nonlinear feature learning capabilities, can mine deep information in HSI, and can overcome the limitations of single-layer information [

23,

24]. However, DL methods require an amount of training and computational cost so there are shortcomings in timeliness.

In recent years, sparse unmixing (SU) has attracted widespread attention as a new semi-supervised method, which is mainly inspired by sparse representation theory. Iordache et al. [

25] applied the sparse regression model to HSI unmixing and used

regularization to enhance the sparsity of the representation coefficients (i.e., abundances), achieving effective abundance estimation (SUnSAL). Subsequently, the Total Variation (TV) regularizer was introduced into SU to improve the piecewise smoothness of the estimated abundance maps [

26]. Inspired by this, many SU models using TV regularization have emerged [

27,

28,

29]. Although TV-based methods can effectively enhance the piecewise smoothness of abundance maps, they increase computational costs. To address this issue, researchers proposed multi-scale methods to replace TV regularization. For example, Ricardo Augusto Borsoi et al. [

30] proposed a new multi-scale spatial regularization SU method based on segmentation algorithms, decomposing the unmixing problem into two simple processes in the approximate image domain and the original image domain. Building on this, Taner Ince et al. combined the advantages of coupled spectral–spatial double-weighted SU [

31] and designed the coarse abundances obtained from unmixing in the approximate image domain as a spatial–spectral weight matrix and used this weight matrix to design a new multi-scale regularization, achieving effective unmixing results with less time consumption [

32]. However, multi-scale unmixing methods are prone to over-smoothing and local image blurring, and they are not as effective as TV regularization in preserving HSI detail features and edge information.

TV regularization excels in uncovering the spatial information within HSI and enhancing the piecewise smoothness of abundances by calculating differences along horizontal and vertical orientations. However, by analyzing the neighborhood structure of HSI, it can be seen that calculating differences only in the horizontal and vertical directions does not fully utilize the neighborhood information of pixels. For example, in addition to horizontal and vertical neighbors, the diagonal and back-diagonal directions are also important spatial structural information for a pixel. Traditional TV ignores this spatial structural prior, resulting in its inability to fully capture the local neighborhood structure of pixels. To address this deficiency, we propose a dual total variation (DTV) regularization method that incorporates differences in the horizontal, vertical, diagonal, and back-diagonal directions of pixels into the model to further encourage the piecewise smoothness of abundances. Similar ideas have also been studied and applied in LF image watermarking [

33] and human parsing [

34] to enhance structural preservation and spatial consistency.

In addition, methods based on graph Laplacian regularization [

35] and joint sparse blocks and low-rank representations [

36] have also shown excellent performance in preserving spatial correlations, resulting in highly effective unmixing outcomes. However, in the above methods, constraints are applied to the abundance matrix during SU. In fact, the structure of the abundance matrix is different from the original spatial structure of HSI, while all abundance maps (i.e., each row of the abundance matrix) are consistent with the spatial structure of HSI. Therefore, constraining each abundance map directly is more efficient than applying regularizations to the abundance matrix. However, the abundance matrix is overloaded with an excessive number of abundance maps, and the vast majority of these maps fail to make meaningful contributions to unmixing. In addition, the spectral library has a large scale and high coherence, which hinders the effective estimation of each abundance map. To address this issue, researchers have proposed some methods [

37,

38,

39] to fine-tune the library atoms before unmixing to reduce the size of the spectral library. However, these methods all depend on the quality of the original hyperspectral data because they all learn active atoms from the given HSI. Therefore, these methods often fail to learn the correct active atoms when HSI is severely contaminated by noise. To solve this problem, Shen et al. proposed a layered sparse regression method [

40] called LSU. This method decomposes SU into a multi-layer process in which each layer fine-tunes the library atoms. Although LSU can effectively overcome the noise influence of HSI, the design of multi-layer also brings considerable computational load to the model. In view of this, Qu et al. [

41] proposed the NeSU-LP method, which divided the SU into two independent and continuous sub-processes, and completed the spectral library pruning at one time to obtain the ideal unmixing effect. However, this method cannot avoid the risk of incorrectly pruned active library atoms. Unlike LSU and NeSU-LP, the FaSUn method [

42] considers a contribution matrix of the spectral library to adaptively update the activity of atoms in the library, rather than directly adjusting the spectral library. The combination of the spectral library and the contribution matrix is used to achieve semi-supervised unmixing. Although this approach avoids the noise influence of HSI and the cumbersome process of library atom adjustment, neither the contribution matrix nor its combination with the spectral library or abundance matrix has a clear physical meaning. Moreover, solving the contribution matrix and abundance matrix together brings a non-convex problem.

Different from the above methods, we propose a sub-abundance map regularization SU method that evaluates the activity of all abundance maps and constrains only the most active sub-abundance maps. This approach differs from other methods that directly apply regularization based on SUnSAL and also from semi-supervised methods with unclear physical meanings. Instead, it precisely imposes constraints on the active abundance maps and achieves precise regularization at the abundance map level while reducing the impact of the large scale and high coherence of the spectral library on SU and avoiding the potential risk of losing important library atoms due to spectral library pruning, thereby improving unmixing quality and efficiency. In the proposed model, we use a new singular value threshold-based discrimination method to determine the number of active sub-abundance maps in HSI. At the same time, we introduce weighted nuclear norm regularization and the designed DTV regularization to constrain the low rank and piecewise smoothness of the sub-abundance maps.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

We propose a novel sub-abundance map regularized sparse unmixing (SARSU) framework based on dynamic abundance subspace awareness. This method introduces an intelligent spectral atom selection strategy that employs a dynamically designed activity evaluation mechanism to quantify the participation contribution of spectral library atoms during the unmixing process. By adaptively selecting key subsets, it constructs active subspace abundance maps to effectively mitigate spectral redundancy interference.

A weighted nuclear norm regularization based on sub-abundance maps was developed to deeply mine potential low-rank structures within spatial distribution patterns, significantly improving the spatial accuracy of unmixing results. Furthermore, a multi-directional neighborhood-aware dual total variation (DTV) regularizer was introduced into the model. Through a four-directional (horizontal, vertical, diagonal, and back-diagonal) differential penalty mechanism, it ensures spatial consistency between adjacent pixels, enabling abundance distributions comply with the physical diffusion laws of ground objects.

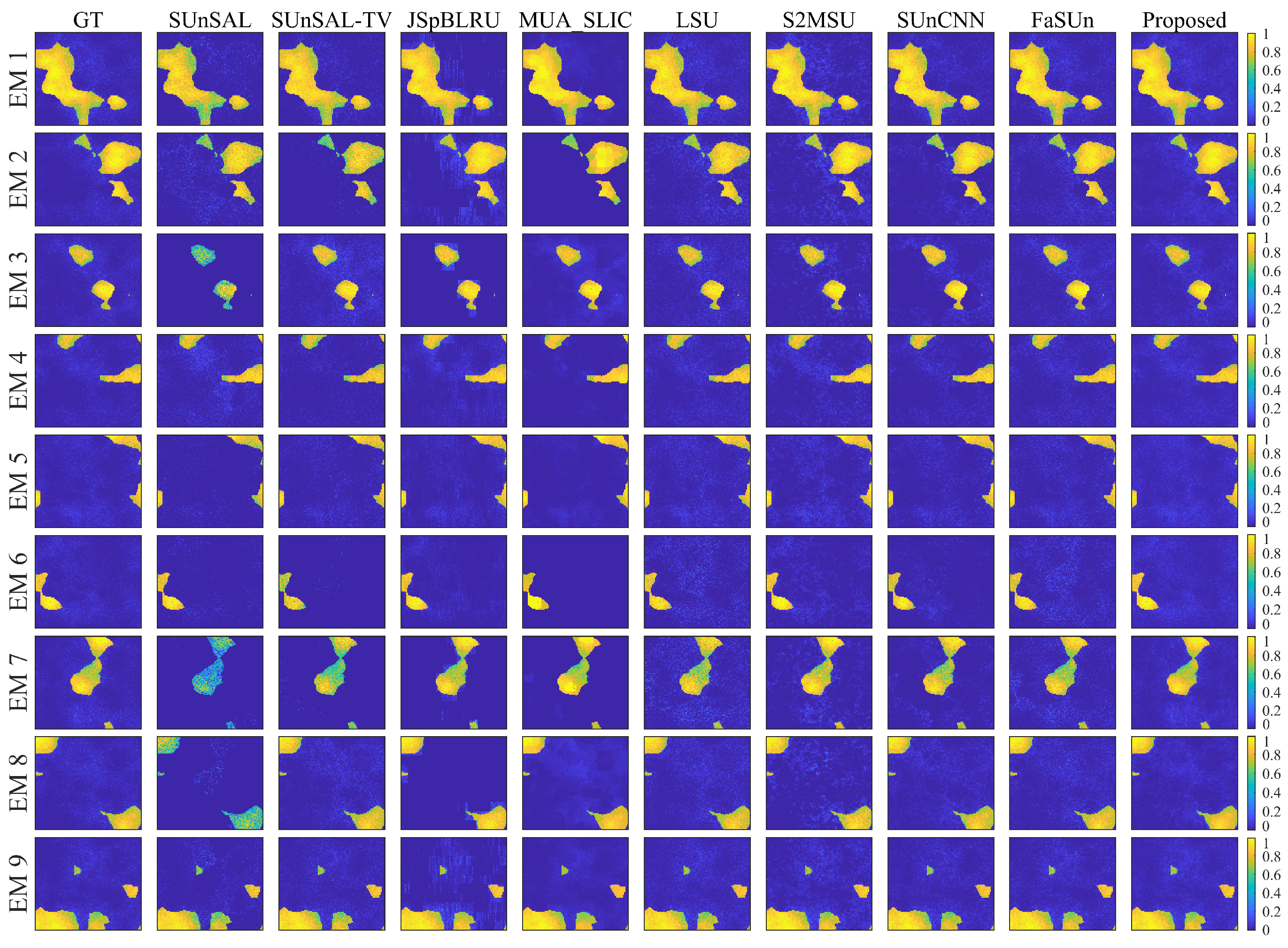

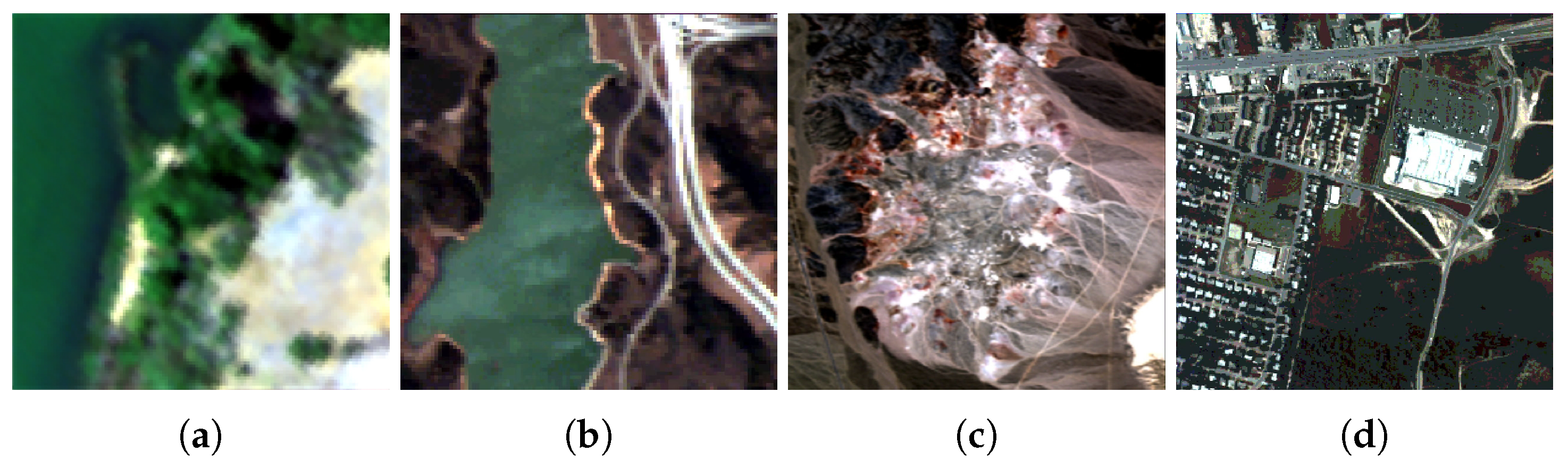

An efficient optimization algorithm based on the Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers (ADMM) was developed. Comprehensive experiments were conducted on two simulated datasets and four real hyperspectral benchmark datasets. The experimental results underwent rigorous analysis, and critical algorithm issues were thoroughly discussed. Through comparative performance analysis with state-of-the-art methods, the effectiveness and superiority of the proposed approach were validated.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The proposed method is presented in

Section 2.

Section 3 describes our experimental results with simulated hyperspectral datasets.

Section 4 describes our experiments with real hyperspectral datasets. Finally, some problem concerning our method is discussed in

Section 5, and

Section 6 provides some conclusions and some future research directions.

5. Discussion

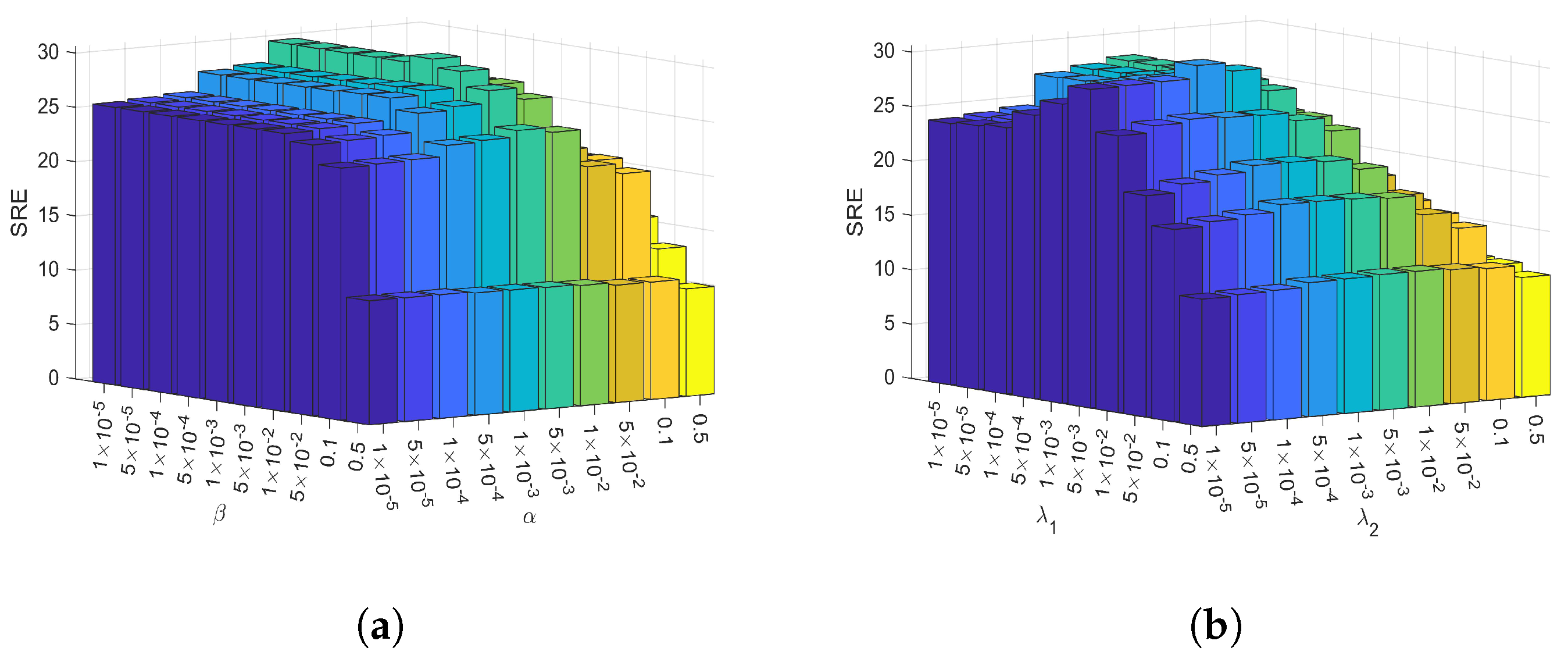

(1) The proposed active sub-abundance map number estimation strategy is based on the SVD of the denoised HSI. A clean HSI data matrix has a jump between large and small singular values (i.e., the large and small values in its singular value matrix are mutated). In order to prove the rationality of the threshold we selected, the two values of the singular value matrix of the denoised HSI data matrix of each dataset are statistically analyzed at the numerical jump.

Table 6 presents two values of the singular value matrix of the denoised HSI data matrix at the numerical jump and number of active sub-abundance maps of each dataset. It can be seen that our selection of the threshold value of 1

is reasonable and feasible and greatly reduces the number of sub-abundance maps that need to be regularized, saving computational overhead. To demonstrate the accuracy of this strategy, we included the results of the widely used VD [

48] and Hysime [

49] methods for determining the number of endmembers for comparison with our method. The experimental results proved the accuracy of this strategy.

(2) The sub-abundance map regularization strategy proposed in this paper can effectively reduce the regularization scale of the abundance matrix and save computational overhead. The inherent low-rank spatial prior of the abundance maps can be efficiently exploited by directly applying weighted nuclear norm regularization to the abundance maps. In addition, it can reduce the adverse effects of the large scale and high coherence of the spectral library on unmixing without pruning the spectral library, avoiding the risk of losing important library atoms in the pruning process. In SU, the proposed method can be applied in real scenarios as a practical fast method.

(3) Regarding the prediction of the number of active sub-abundance maps, besides the singular value thresholding method used in this paper, there are also many effective methods for estimating the number of endmembers that can be utilized. Firstly, the number of active sub-abundance maps is determined by estimating the number of endmembers, then they are specifically determined, and finally they are constrained. Such a series of operations can be used as a technical route of SU in future practice.