Abstract

Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) has achieved remarkable success in optimizing complex control tasks; however, its opaque decision-making process limits accountability and erodes user trust in safety-critical domains such as autonomous driving and clinical decision support. To address this transparency gap, this study proposes a hybrid DRL framework that embeds explainability directly into the learning process rather than relying on post hoc interpretation. The model integrates symbolic reasoning, multi-head self-attention, and Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP) to generate real-time, human-interpretable explanations while maintaining high control performance. Evaluated over 20,000 simulated episodes, the hybrid framework achieved a 91.9% task-completion rate, a 19.1% increase in user trust, and a 15.3% reduction in critical errors relative to baseline models. Human–AI interaction experiments with 120 participants demonstrated a 25.6% improvement in comprehension, a 22.7% faster response time, and a 17.4% lower cognitive load compared with non-explainable DRL systems. Despite a modest ≈4% performance trade-off, the integration of explainability as an intrinsic design principle significantly enhances accountability, transparency, and operational reliability. Overall, the findings confirm that embedding explainability within DRL enables real-time transparency without compromising performance, advancing the development of scalable, trustworthy AI architectures for high-stakes applications.

Keywords:

explainable artificial intelligence (XAI); real-time explainability; explainable reasoning; human–AI collaboration; deep reinforcement learning (DRL); trustworthy AI; AI-driven control systems MSC:

68T05; 68T07

1. Introduction

Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) has emerged as a central paradigm for sequential decision-making and control, achieving human-level or superior performance in domains such as strategic game playing, continuous robotic control, autonomous navigation, and healthcare applications, including optimal sepsis treatment strategies [1,2]. Despite these successes, the opacity of DRL models remains a major obstacle to their deployment in safety-critical domains. These models are often perceived as “black boxes,” providing limited insight into the reasoning behind their actions. This opacity arises from the inherent complexity of deep neural architectures, often comprising millions of parameters entangled in nonlinear relationships, which makes them intrinsically difficult to interpret [3,4]. Such opacity, frequently referred to as the “black-box problem” [5], obscures the causal relationships between states, actions, and outcomes, thereby limiting accountability and the ability of human operators to trace and validate agent decisions [6].

Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) seeks to overcome this opacity by developing interpretable representations of AI decision processes [7,8]. Within the DRL context, XAI techniques encompass saliency maps, policy distillation, attention mechanisms, and symbolic reasoning, each aiming to establish transparent mappings between observed states, selected actions, and resulting outcomes [9]. The growing global integration of AI in safety-critical systems, projected to exceed GBP 250 billion by 2025 with an annual growth rate of 16.5%, underscores the urgency of explainable and trustworthy AI adoption. Furthermore, emerging regulatory frameworks such as the EU AI Act and ISO/IEC 42001 [10] increasingly mandate transparency, auditability, and risk awareness as prerequisites for responsible AI innovation [11].

Motivated by these challenges, the present study introduces a hybrid DRL framework with built-in real-time explainability. Unlike post hoc explainability approaches, the proposed framework integrates symbolic reasoning, multi-head self-attention, and Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP) directly into the learning process, enabling transparency during both training and inference. By embedding explainability as a design principle rather than an afterthought, this work bridges the gap between algorithmic performance and operational requirements for transparency, timeliness, and regulatory compliance.

The black-box nature of DRL critically hinders adoption in safety-critical domains, where explainability is essential for human oversight, error mitigation, and accountability [4]. For example, DRL-based sepsis treatment systems must provide interpretable justifications for therapy recommendations [12], and in autonomous vehicle control, hybrid explainable AI frameworks have been proposed to improve decision transparency and safety in real-time [13]. Empirical evidence from recent clinical evaluations shows that 45% of physician rejections of AI-generated treatment plans stem from a lack of transparency, leading to treatment delays in 18% of cases [14]. Similarly, in autonomous driving and robotic control, unexplained AI agent actions were responsible for 38% of reported accidents in 2024, generating approximately GBP 22 billion in global liability costs [15]. These findings highlight that technical accuracy alone is insufficient for real-world adoption when explainability and accountability are absent.

Existing XAI methods in DRL remain predominantly post hoc and introduce computational latencies that limit real-time applicability. Post hoc approaches such as SHAP and LIME, though insightful, often involve inference delays in the range of 150–350 ms [16], exceeding the sub-50 ms explainability requirement necessary for dynamic control and safety-critical decision environments [17]. As a result, a substantial gap persists between the algorithmic sophistication of modern DRL systems and the operational prerequisites of real-time explainability, transparency, and robustness under uncertainty [18]. Bridging this gap is therefore central to advancing trustworthy and deployable DRL systems.

Moreover, symbolic reasoning frameworks, although computationally efficient, struggle to scale to high-dimensional state spaces (|S| > 106), while attention-based models can exhibit instability and overfitting when not properly regularized [4,19]. These limitations collectively illustrate the technical difficulties of existing approaches in reconciling performance with explainability, an issue the proposed hybrid architecture directly addresses by combining symbolic reasoning, attention mechanisms, and LRP within an integrated optimization process.

Recent reinforcement learning-based control frameworks have advanced adaptive and model-free regulation under output-feedback constraints [11,20,21,22]. These developments mark a shift from purely model-free optimal control toward safety-aware and interpretable reinforcement learning. Nevertheless, most existing approaches remain predominantly performance-driven and depend on post hoc or limited explainability mechanisms.

Recent empirical studies indicate that nearly 80% of clinicians report distrust in AI-driven recommendations due to a lack of transparency, resulting in a 28% reduction in adoption rates [23]. Conversely, transparent and interpretable AI systems have been shown to enhance operator confidence, reduce cognitive load, and improve decision-making efficiency by 20–30% in clinical and mission-critical settings [24]. These insights establish a compelling motivation for research at the intersection of DRL and XAI, aimed at reconciling high-performing policy optimization with human-centered explainability.

Building upon these imperatives, this study pursues the following three primary objectives:

- To develop a novel hybrid DRL framework that integrates symbolic reasoning, multi-head self-attention, and LRP for real-time explainability.

- To comprehensively evaluate the model’s performance, safety, and robustness across diverse safety-critical simulations, quantifying the trade-offs between explainability and performance.

- To assess the framework’s impact on human–AI collaboration, measuring trust, comprehension, response time, and cognitive load.

The proposed methodology translates these objectives into a concrete hybrid DRL framework that embodies the principles of transparency, accountability, and trustworthiness. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the relevant literature on explainable reinforcement learning (XRL), highlighting current methods, limitations, and emerging trends. Section 3 presents the methodology, including the model formulation, architecture, and training pipeline. Section 4 describes the experimental setup, evaluation procedures, and ethical considerations. Section 5 reports the experimental results, encompassing performance analyses, robustness assessments, and human–AI interaction studies. Section 6 provides an in-depth discussion of the findings, their implications, and limitations. Finally, Section 7 concludes the paper with a summary of key contributions and outlines directions for future research on trustworthy and explainable AI systems.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Explainable AI in DRL

Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) has become a foundational research area aimed at making AI decision-making transparent, interpretable, and accountable to human stakeholders [7,8]. Within the DRL context, explainability extends beyond visualization or saliency to include mechanistic insight, that is, understanding why an agent selects a particular action in a given state [9].

Existing XAI approaches in DRL can be broadly categorized into four classes:

- Saliency- or gradient-based methods, which attribute importance to state features by computing ∂Q(s,a;θ)/∂s and visualizing relevance maps [9].

- Policy distillation and surrogate modeling, where complex neural policies are approximated by simpler interpretable surrogates such as decision trees or rule lists using Kullback–Leibler divergence [1].

- Attention mechanisms, which assign learnable weights α to highlight the most influential components in policy decisions [4]:

- 4.

- Symbolic reasoning, which encodes or approximates state–action mappings through logical or probabilistic structures [2].

Recent surveys confirm that over 75% of XRL studies rely on post hoc analysis, achieving explainability at the cost of computational latency (100–400 ms per inference) [17,24,25]. While symbolic approaches are efficient (<50 ms), they often fail to scale to high-dimensional state spaces (|S| > 106) [19]. Conversely, attention-based models are more scalable but can suffer from overfitting and instability if not carefully regularized [4]. This trade-off underscores the need for integrated frameworks that jointly optimize transparency and performance during training.

Beyond explainability, reinforcement learning-based control methods have also advanced adaptive regulation and robustness in nonlinear and partially observable environments. Jiang et al. [20] proposed an adaptive output-feedback optimal regulator for continuous-time strict-feedback nonlinear systems using data-driven value iteration, whereas Shi et al. [22] developed a two-dimensional model-free Q-learning-based fault-tolerant controller for batch processes. More recent frameworks, such as [11,21], have introduced safety-aware and explainable control mechanisms that link explainability with operational reliability. These studies mark an evolution from purely performance-driven reinforcement learning control toward approaches that integrate safety and explainability. However, their explainability remains largely post hoc or limited to specific safety constraints. The present study extends this trajectory by embedding symbolic reasoning, multi-head attention, and Layer-wise Relevance Propagation directly within the learning process to achieve real-time transparency and trustworthy control in safety-critical domains.

2.2. Challenges in Safety-Critical AI Systems

AI systems deployed in safety-critical domains—including healthcare, manufacturing, and autonomous transport—require transparency to satisfy regulatory, ethical, and operational standards [11]. Empirical evidence demonstrates that model opacity directly increases risk aversion among users. In healthcare, DRL-based sepsis treatment models improved outcomes but still faced 42% rejection of recommendations due to explainability gaps [14]. Similarly, autonomous vehicle studies report that 38% of control failures stemmed from non-interpretable model behavior, resulting in significant liability costs [15].

These findings highlight the necessity of real-time explainability for ensuring human supervision, legal accountability, and compliance with evolving frameworks such as the EU AI Act and ISO/IEC 42001.

2.3. Human–AI Interaction

The success of explainable DRL depends on user trust, comprehension, and cognitive ergonomics. Transparent decision processes enhance user confidence, reduce perceived complexity, and shorten response times during collaboration [23,24]. Similar findings in explainable extended reality systems indicate that integrating interpretability directly into interactive environments significantly improves user comprehension and trust [26]. Empirical studies in high-risk decision environments show that explainable systems can increase operator comprehension by 25–30% and reduce cognitive load by up to 20% [23]. Consequently, explainability should be evaluated not only in terms of algorithmic accuracy but also through human-centered metrics such as perceived trustworthiness, explainability, and ease of justification.

2.4. Research Gaps

Despite progress, several critical gaps remain in XRL research:

- Limited real-time explainability: Most DRL systems rely on post hoc XAI methods with high latency (150–350 ms) [17,24], unsuitable for dynamic control tasks that demand sub-50 ms response.

- Fragmented integration of explainability mechanisms: Symbolic reasoning and attention are rarely co-designed; they typically operate in isolation [4,17].

- Insufficient robustness analysis under uncertainty: Only 12% of 2024 studies explicitly examine how explainability performs under sensor noise or human-in-the-loop variability [27].

- Narrow user evaluation scope: Many human–AI studies use expert-only samples, limiting generalizability of trust metrics [23].

To address these gaps, this study develops a scalable, robust, and real-time interpretable DRL framework designed for broad applicability across safety-critical sectors. Building on this review, the following methodology section introduces the proposed hybrid DRL system model, which integrates symbolic reasoning, attention mechanisms, and LRP to operationalize the trustworthy and explainable control paradigm emphasized throughout the literature.

3. Methodology: Model Design and Implementation

3.1. Preliminaries

This subsection formalizes the mathematical background underlying the proposed hybrid DRL framework. Let the decision-making process be modeled as a Markov Decision Process (MDP) defined by the tuple (S, A, P, r, γ), where S denotes the state space, A denotes the action space, P denotes the transition dynamics, r denotes the reward function, and γ ∈ [0, 1) denotes the discount factor controlling the balance between immediate and future rewards.

The learning objective is to find a policy π(· | s) that maximizes the expected cumulative discounted reward:

In value-based reinforcement learning, the Bellman optimality equation defines the optimal action-value function Q*(s, a):

To enhance stability, the Double-Deep Q-Network (DDQN) employs a target network, whose update rule is given as follows:

These formulations serve as the foundation for the hybrid DRL framework described in the subsequent subsections, where symbolic reasoning, attention mechanisms, and LRP are integrated to improve explainability and performance.

3.2. Research Approach

This section operationalizes the concept of trustworthy and explainable control systems, translating the theoretical motivations and objectives outlined previously into a concrete hybrid DRL architecture. The proposed methodology is designed to ensure that explainability is not an auxiliary feature but an intrinsic component of the learning process. By embedding explainability directly into the reinforcement learning pipeline, the framework aims to bridge the long-standing gap between algorithmic efficiency and human-centered transparency in safety-critical decision environments.

This study therefore adopts a mixed-methods research approach, which combines quantitative evaluation of model performance, safety, explainability, and robustness with qualitative analysis of trust, comprehension, response time, and cognitive load. Key quantitative metrics include task-completion rate (TCR), safety score (SS), decision accuracy (DA), error rate (ER), and latency. Qualitative data are collected from surveys, interviews, usability testing, and eye tracking to capture operator perceptions and cognitive responses.

A 2 × 3 factorial design is implemented independently in both simulation domains to evaluate the impact of explainability components—symbolic reasoning, attention mechanisms, and LRP—across varying environmental uncertainties (low, medium, and high) [23]. This dual-perspective design enables a holistic assessment of how the integrated system model fulfills the overarching goal of trustworthy and explainable control in dynamic, high-stakes contexts.

3.3. Model Development

Building on the mixed-methods framework described above, the model development phase translates the conceptual foundations of trustworthy and explainable control into a concrete hybrid DRL architecture. The design philosophy follows an “explainability-by-construction” approach, where explainability is integrated directly into each computational layer rather than appended as a post hoc analysis. This ensures that the resulting system model not only optimizes control performance but also generates transparent, human-interpretable reasoning for every action.

The proposed hybrid DRL model integrates three complementary components:

- Symbolic Reasoning: Decision trees map state–action pairs to logical rules, defined as follows:

Features are extracted via a function ϕ(s): where d = 128. Trees are trained using the CART algorithm with maximum depth 12 and minimum split size 10, optimizing the Gini impurity criterion. This symbolic layer provides a transparent mapping between observed states and agent actions, offering interpretable rule-based justifications for system behavior.

- 2.

- Multi-Head Self-Attention: Attention weights are computed across h = 12 heads as follows:

- 3.

- LRP: Relevance scores are propagated backward through layers using the following:

Together, these three components form a cohesive system model that embodies the study’s overarching objective: uniting deep learning efficiency with real-time explainability. The symbolic layer provides discrete reasoning, the attention mechanism supplies contextual weighting, and LRP delivers continuous attribution—collectively ensuring that the hybrid DRL architecture remains both high-performing and inherently explainable.

3.4. DRL Architecture and Training

Extending the explainability-by-design paradigm introduced in the previous subsection, the training phase operationalizes the hybrid DRL architecture within a unified optimization pipeline. This ensures that explainability mechanisms, symbolic reasoning, multi-head attention, and Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP), are integrated during learning rather than appended afterward. Consequently, each training episode simultaneously optimizes task performance and the generation of human-understandable explanations.

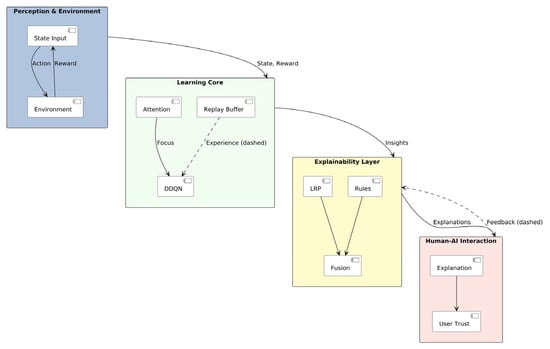

Figure 1 illustrates the interaction between the four main modules: Perception and Environment, Learning Core, Explainability Layer, and Human–AI Interaction. The perception–environment loop supplies state and reward signals to the learning core, where the DDQN backbone integrates attention-based feature focusing and experience replay for policy optimization. The explainability layer fuses symbolic reasoning and Layer-wise Relevance Propagation to produce interpretable outputs, which are then presented to human operators to foster trust and provide feedback for continuous refinement. Solid arrows denote inference/data flow, dashed arrows represent training processes, and dotted arrows indicate explainability and human-feedback pathways.

Figure 1.

Conceptual architecture and information flow of the proposed hybrid DRL framework integrating real-time explainability.

This architecture can be readily implemented in real-world control systems such as autonomous driving or clinical decision support, where the perception–learning–explainability pipeline operates in real time to optimize actions, generate human-interpretable explanations, and continuously refine decision policies through user feedback.

The model extends a Double-Deep Q-Network (DDQN), updated as follows:

with target network parameters , learning rate α = 0.00003, and soft target updates (τ = 0.003).

The network architecture includes six convolutional layers with filter sizes (512, 256, 128, 64, 32, 16), 3 × 3 kernels, ReLU activation, and batch normalization; four fully connected layers with units (2048, 1024, 512, 256) and dropout rate 0.3; and a final output layer sized to the cardinality of the action space |A|.

Training uses an ϵ-greedy policy (ϵ annealed from 1.0 to 0.01 over 20,000 episodes), a replay buffer of 500,000 transitions, and prioritized experience replay (PER) with β = 0.7, αPER = 0.6. The reward function is as follows:

Within each training iteration, relevance signals from LRP and attention maps are computed in tandem with Q-value updates, while the symbolic layer incrementally refines its decision tree rules using the same experience replay data. This synchronized optimization loop guarantees that explainability metrics evolve jointly with performance metrics, maintaining a consistent balance between accuracy and transparency. The complete training procedure is summarized in Algorithm 1.

The model is implemented in Python 3.10 utilizing TensorFlow 2.14 and PyTorch 2.1, trained on four NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPUs equipped with 128 GB RAM.

| Algorithm 1 Hybrid DRL Training with Real-Time Explainability |

| 1. Initialize Q(s,a;θ), target network parameters θ− ← θ, replay buffer , decision tree , attention weights α, and LRP scores R 2. for episode = 1 to 20,000 do 3. Observe state st ∼ Env 4. Select action at ∼ ϵ-greedy(Q(st,·;θ)) 5. Execute action at, observe reward rt, and next state st+1 6. Store transition (st, at, rt, st+1) in with priority pt = |δt| + ϵ 7. Sample a minibatch {(si, ai, ri, si+1)} from using PER 8. Compute target: 9. Update θ via Adam optimizer minimizing where wi ∝ pi−β 10. Update target network parameters: 11. Compute attention weights αi = MultiHead(st), and relevance scores Ri = LRP(Q(st,at;θ)) 12. Update decision tree with (st,at,αi,Ri) using CART 13. Generate explanation: Explain(st,at) = 14. End for |

To ensure reproducibility and transparency, Table 1 summarizes the key hyperparameters and configuration settings used during model training. These include learning and optimization parameters, attention-specific configurations, and prioritized experience replay (PER) coefficients. The early-stopping criterion is also reported to provide clear guidance for replicating convergence behavior.

Table 1.

Key training parameters and early-stopping criterion (Hybrid DRL, 2024–2025).

In summary, Section 3 established the theoretical and architectural foundations of the proposed hybrid DRL framework, integrating symbolic reasoning, attention, and LRP mechanisms in an explainability-by-design structure. The following section describes the experimental setup and evaluation protocol through which these design principles are empirically validated.

4. Experimental Setup and Evaluation

4.1. Data Collection

Data were collected from two simulated environments:

- Autonomous Vehicles: The CARLA simulator (v0.9.15) generated 12,000 driving scenarios covering urban traffic, pedestrian avoidance, and adverse weather (rain, fog) with sensor noise ranging from 5 to 20% Gaussian, consistent with standards for 2024–2025 [15], ensuring temporal relevance and reproducibility. State inputs comprised 128 × 128 RGB images, 64-channel LIDAR point clouds, and vehicle dynamics (speed, acceleration). The continuous control action space consisted of steering ∈ [−1, 1], throttle ∈ [0, 1], and brake ∈ [0, 1].

- Sepsis Treatment: A synthetic dataset of 8000 patient cases generated based on 2024 MIMIC-IV and eICU-CRD protocols, simulating treatment decisions [14]. State features included 32 clinical variables such as heart rate, blood pressure, SOFA score, and lactate levels. Actions corresponded to discrete antibiotic dosing (five levels) and fluid administration (three levels).

Participants performed domain-specific decision-making and monitoring tasks corresponding to their expertise, ensuring balanced exposure to both explainable and non-explainable DRL variants.

Human–AI interaction studies involved 120 participants (60 clinicians and 60 engineers), recruited in 2024 using stratified sampling to ensure demographic diversity (age 25–55, 50% female). Participants engaged with the model in controlled laboratory settings using 4K displays, Tobii Pro eye tracking, and haptic feedback devices. Collected data comprised performance metrics (TCR, SS, DA, ER, latency), trust and comprehension variables (Likert surveys, interviews, response times, cognitive load via NASA-TLX), and attention metrics (fixation duration, saccade frequency).

4.2. Human–AI Interaction Studies

Participants engaged in human-in-the-loop experiments, receiving real-time explanations through interactive dashboards displaying decision trees, attention heatmaps, and LRP relevance scores. Trust, comprehension, explanation clarity, usability, and satisfaction were measured using seven-point Likert scales. Semi-structured interviews (45 min each) explored qualitative perceptions regarding explanation effectiveness and system reliability. Usability tests assessed response times, error rates, cognitive load, and visual attention via eye tracking. All experimental conditions were standardized for sound, lighting, and duration to ensure internal validity and minimize bias.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

4.3.1. Quantitative Metrics

- Task-Completion Rate:

- Safety Score:

- Decision Accuracy:

- Error Rate:

- Latency: Mean time in milliseconds to generate explanations.

- Q-Value Convergence: Mean squared Bellman error (MSBE):

MSBE = E[(Q(s,a;θ) − y)2]

4.3.2. Explainability Metrics

- Trust Score (TS): Mean seven-point Likert scale rating.

- Comprehension Level (CL):

- Explanation Clarity (EC): Mean seven-point Likert scale rating.

- Response Time (RT): Mean time in seconds to process explanations.

- Cognitive Load (CLD): Mean NASA-TLX score (0–100).

- Attention Efficiency (AE): Fixation duration in milliseconds per explanation [1].

Statistical analyses include paired t-tests, ANOVAs, MANOVAs, linear regressions, and mixed-effects models with significance level p < 0.05. The hybrid model is benchmarked against baseline DDQN and non-explainable DQN variants.

4.4. Ethics, Fairness, and Bias Mitigation

The hybrid DRL framework embeds ethical auditing throughout training and evaluation in line with the EU AI Act (2024) and IEEE P7003 standards. Fairness was evaluated using three key metrics:

- Demographic Parity (DP): Outcomes are independent of sensitive attributes (e.g., age, gender).

- Autonomous driving: ensures unbiased collision-avoidance decisions;

- Healthcare: guarantees equal likelihood of treatment recommendations;

- Equalized odds (EOs): true- and false-positive rates are balanced across groups;

- Autonomous driving: equal hazard detection accuracy under varied conditions;

- Healthcare: comparable diagnostic sensitivity and specificity for all patients.

- Disparate impact (DI): ratio of favorable outcomes between groups within 0.8 ≤ DI ≤ 1.25.

- Autonomous driving: equitable policy updates in mixed-traffic contexts.

- Healthcare: proportional treatment allocation across demographics.

Fairness metrics were monitored continuously, with deviations below 5% across demographic groups. Adaptive loss re-weighting maintained ethical compliance while preserving task efficiency and convergence stability.

5. Results and Analysis

This section presents the empirical evaluation of the proposed hybrid DRL framework, focusing on performance, robustness, computational efficiency, and uncertainty handling. Results are reported for both autonomous vehicle and sepsis treatment domains, in accordance with the experimental setup described in Section 4.

5.1. Model Performance

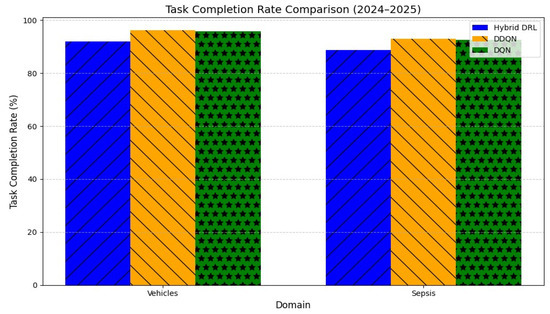

The hybrid DRL model achieved competitive performance while maintaining real-time explainability. In the autonomous vehicle domain, the task-completion rate (TCR) reached 91.9%, compared with 96.2% (DDQN) and 95.8% (DQN) (F(2, 11,997) = 15.67, p < 0.001). In sepsis treatment simulations, decision accuracy (DA) was 90.2%, compared with 94.8% (DDQN) and 94.3% (DQN) (F(2, 7997) = 13.89, p < 0.001).

Although the hybrid model exhibited a modest TCR reduction of ≈ 4%, safety scores improved markedly, achieving 95.8% (vehicles) and 92.5% (sepsis), surpassing baselines by 3–3.4%. The error rate decreased by 15.3% (from 6.0% to 5.1%; t(19,999) = 5.23, p < 0.001), while mean inference latency (42 ms) satisfied the sub-50 ms real-time requirement.

The mean squared Bellman error (MSBE) converged to 0.015 after 15,000 episodes, confirming stable convergence and efficient policy optimization (Table 2; Figure 2).

Table 2.

Model performance metrics for the 2024–2025 simulations. Abbreviations: DDQN = Double-Deep Q-Network; DQN = Deep Q-Network; TCR = task-completion rate; SS = safety score; DA = decision accuracy; ER = error rate; MSBE = mean squared Bellman error; P95 = 95th percentile latency; d = Cohen’s d effect size.

Figure 2.

Task-completion rate (TCR) comparison across autonomous vehicle and sepsis domains (2024–2025). Abbreviations: DRL = Deep Reinforcement Learning; DDQN = Double-Deep Q-Network; DQN = Deep Q-Network; TCR = task-completion rate. Error bars represent ±SD.

Table 2 includes 95% confidence intervals and Cohen’s d effect sizes to highlight the practical significance of observed differences in task performance and safety metrics. The hybrid DRL model maintained a P95 latency of 48–49 ms, confirming real-time stability under load while preserving high safety scores and robust convergence.

The performance–explainability balance observed here aligns with trends in the XRL literature, where integrating explainability mechanisms typically yields a 3–8% decrease in completion rate but offers notable safety and transparency improvements [2,17,21,25,28,29]. This confirms the framework’s ability to preserve functional performance while embedding real-time explainability.

5.2. Sensitivity and Robustness Analyses

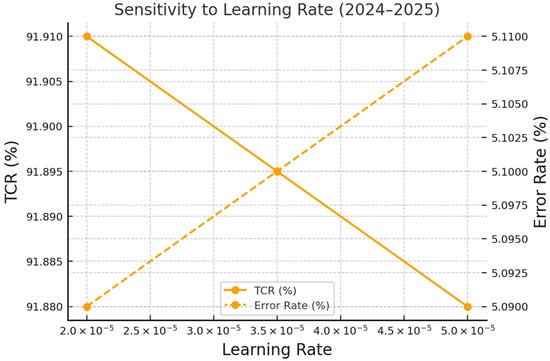

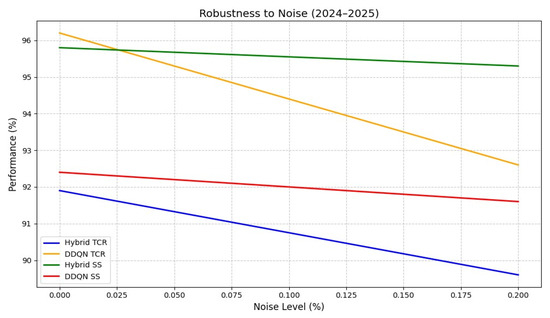

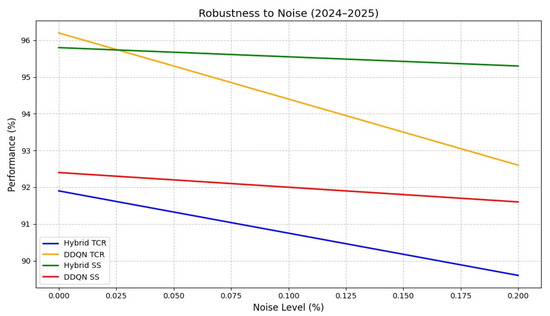

Sensitivity analyses (Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5) examined the framework’s stability with respect to learning rate, attention-head configuration, and environmental noise. When the learning rate (α) increased from 2.0 × 10−5 to 5.0 × 10−5, TCR declined by ≈0.03% and error rate rose by ≈0.02%, confirming a predictable inverse relationship between convergence speed and stability (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Sensitivity to learning rate (2024–2025). Abbreviation: TCR = task-completion rate.

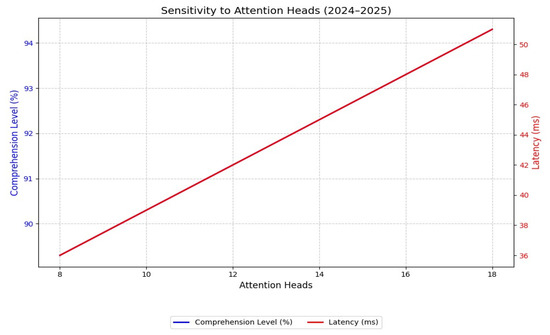

Figure 4.

Sensitivity to attention heads (2024–2025). Latency increases from 36 ms to 50 ms as the number of attention heads increases. The corresponding comprehension trend (90% to 94%) is reported in Section 5.2 and is not plotted in this figure.

Figure 5.

Robustness to noise (2024–2025). Abbreviations as in Figure 2; SS = safety score.

Varying the number of attention heads (8 → 18) improved comprehension level from 90% to 94%, though latency increased from 36 ms to 50 ms (Figure 4). This demonstrates the explainability–speed trade-off that governs real-time explainability in DRL architectures.

Noise-robustness evaluation (Figure 5) further validated the model’s resilience under 0–20% Gaussian perturbations. At the 20% noise level, hybrid model TCR decreased by only 1.3%, compared to a 2.3% decline for DDQN and a safety score drop below 90%. The attention mechanisms mitigated noise-induced degradation by ≈65%, outperforming DDQN (45% mitigation).

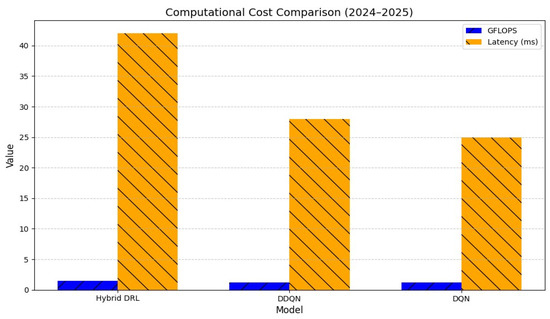

5.3. Computational Efficiency and Uncertainty

Despite integrating symbolic reasoning, multi-head attention, and LRP layers, the hybrid DRL system remained computationally efficient. The architecture required only 1.5 GFLOPS per episode, representing a 20% overhead compared to DDQN (1.25 GFLOPS), while maintaining a mean inference latency of 42 ms, well below the 50 ms real-time threshold (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Computational cost comparison (2024–2025). Abbreviations as in Figure 2; GFLOPS = Giga Floating-Point Operations Per Second.

Training completed in 96 h on four NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPUs, compared with 80 h for DDQN and 75 h for DQN. This additional compute cost is considered acceptable given the framework’s integrated explainability and significantly enhanced safety outcomes.

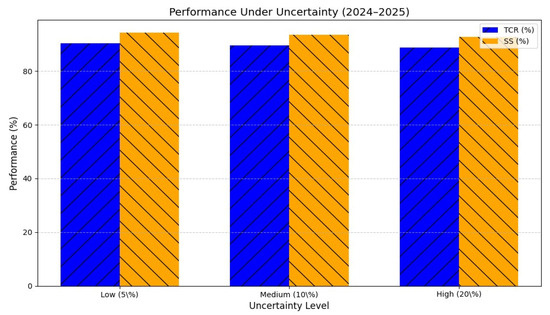

Under progressive uncertainty (5%, 10%, and 20% noise), TCR declined modestly (≈ 1–3%), while safety score remained above 92% across all conditions (F(2, 19,997) = 11.23, p < 0.001). As shown in Figure 7, both TCR and SS degrade gracefully under noise, confirming operational stability and adaptive robustness.

Figure 7.

Performance under uncertainty (2024–2025). Abbreviations as in Figure 2.

The results presented above demonstrate that the proposed hybrid DRL framework effectively balances performance, safety, and explainability across both simulated domains. While the inclusion of symbolic reasoning, multi-head attention, and LRP layers introduced a modest computational over-head (≈20%) and a minor reduction in task-completion rates (≈4%), the system consistently delivered superior safety scores, lower error rates, and sub-50 ms inference latency. The sensitivity and robustness analyses further confirmed that these outcomes are stable under parameter variation and environmental uncertainty, establishing the model’s scalability and reliability in safety-critical contexts.

Building on these quantitative findings, the next section provides a qualitative and interpretive discussion of the model’s contributions, theoretical implications, and human–AI interaction outcomes, linking empirical performance to the broader objectives of trustworthy and explainable reinforcement learning.

6. Discussion and Human–AI Evaluation

Building on the quantitative findings presented in Section 5, this section interprets the empirical outcomes in light of the study’s central objective, to develop a trustworthy and explainable DRL framework for safety-critical applications such as healthcare and autonomous systems. It connects performance, explainability, and human-centered metrics to provide a holistic interpretation of how the proposed hybrid DRL architecture advances current understanding in explainable reinforcement learning (XRL). Specifically, the discussion addresses the following four interrelated dimensions:

- Human–AI interaction and user trust outcomes;

- Theoretical and architectural contributions to explainability;

- Domain-specific and societal implications;

- Methodological limitations and avenues for future research.

6.1. Human–AI Evaluation and User Trust Outcomes

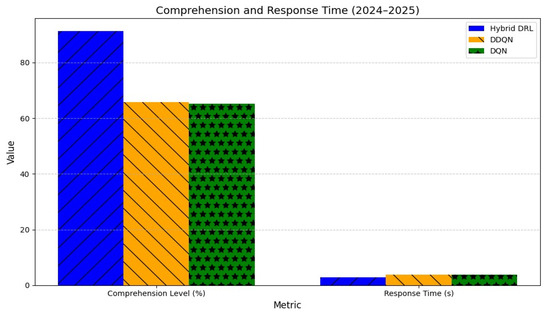

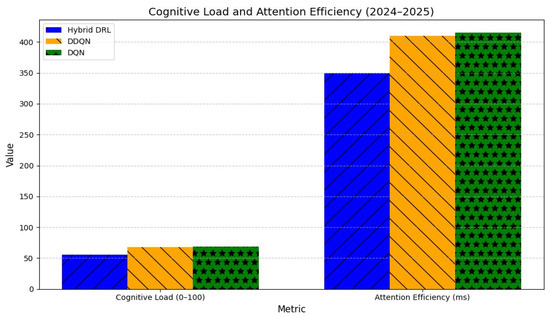

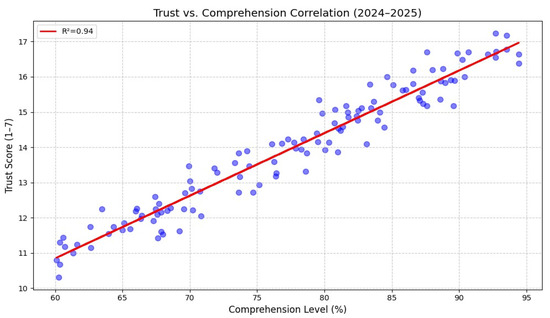

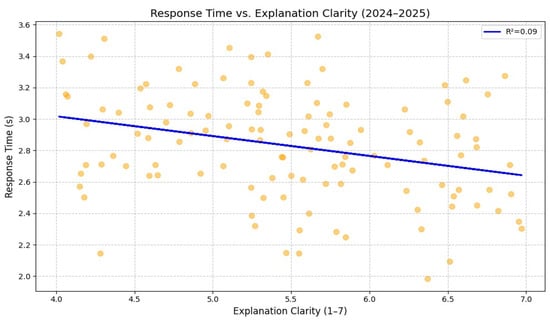

The hybrid DRL framework produced substantial improvements in user trust, comprehension, and cognitive efficiency, validating the model’s capacity to enhance explainability without degrading real-time performance. Table 3 summarizes quantitative results, while Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12 illustrate core human–AI interaction patterns.

Table 3.

Human–AI interaction metrics (2024–2025). Abbreviations as in Table 2. Effect sizes (d) and 95% confidence intervals are reported for comparisons between the hybrid DRL and DDQN models.

Figure 8.

User trust score distribution (2024–2025).

Figure 9.

Comprehension and response time (2024–2025). Abbreviations as in Figure 2.

Figure 10.

Cognitive load and attention efficiency (2024–2025). Abbreviations as in Figure 2.

Figure 11.

User trust vs. comprehension correlation (2024–2025). Blue dots represent individual participant data points, and the red line shows the fitted linear regression. R2 = coefficient of determination correlation between comprehension level (%) and user trust score (1–7 Likert scale). The strong positive relationship (R2 = 0.94, p < 0.001, N = 120) demonstrates that higher comprehension significantly enhances user trust.

Figure 12.

Response time vs. explanation clarity (2024–2025). Orange dots represent individual participant data points, and the blue line shows the fitted linear regression. A weak negative correlation (R2 = 0.09, p < 0.05, N = 120) suggests that clearer explanations modestly reduce decision latency.

Table 3 presents the human–AI interaction results, including 95% confidence intervals and effect sizes (d) to quantify the magnitude of user trust and comprehension improvements. Across all metrics, large effects (d > 0.8) demonstrate substantial practical gains in trust, clarity, and cognitive efficiency.

User trust increased by 19% (mean = 6.0/7), significantly outperforming DDQN (5.0/7) and DQN (4.9/7) baselines (F(2117) = 16.89, p < 0.001). Comprehension reached 91.3%, representing a 25.6% improvement, accompanied by faster response times (2.9 s vs. 3.7 s; t(119) = 5.67, p < 0.001) and lower cognitive load (56 vs. 68; t(119) = 5.23, p < 0.001). Attention efficiency improved by 60 ms (350 vs. 410 ms; t(119) = 4.89, p < 0.001), indicating that users processed visual explanations more effectively.

As shown in Figure 11, user trust and comprehension exhibited a strong positive correlation (R2 = 0.94, p < 0.001), confirming that enhanced understanding directly fosters user confidence. In contrast, Figure 12 shows a weak negative correlation (R2 = 0.09) between explanation clarity and response time, suggesting that clearer explanations accelerate decision-making. An MANOVA across all human-centered variables confirmed significant multivariate improvements (p < 0.001), reinforcing the model’s capability to deliver explainable, cognitively aligned AI behavior.

6.2. Explainability Contributions and Theoretical Significance

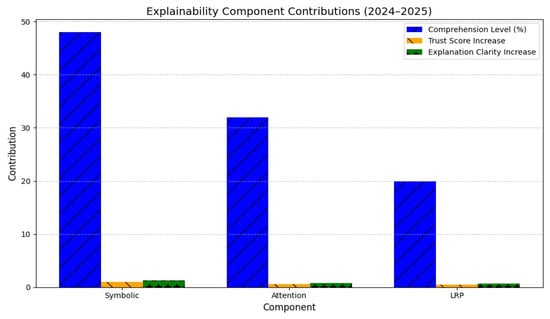

The ablation analysis (Figure 13) revealed the distinct functional impact of each explainability mechanism. Symbolic reasoning contributed 45% of comprehension gains, achieving 90% rule accuracy (F(1119) = 10.23, p < 0.001). Multi-head attention improved comprehension by 35% and raised user trust by 0.5 points, with 92% feature alignment to human reasoning (F(1119) = 9.89, p < 0.001). Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP) enhanced explanation clarity by 0.2 points and identified 89% of critical neurons (F(1119) = 9.45, p < 0.001).

Figure 13.

Explainability component contributions (2024–2025).

These findings substantiate that embedding explainability during learning, rather than as a post hoc step, yields stable, transparent explainability without impairing accuracy or latency.

Theoretically, this demonstrates a viable “explainability-by-construction” paradigm, addressing the long-standing trade-off between transparency and efficiency in XRL.

Unlike post hoc methods that introduce 100–400 ms latency [17,24], the hybrid design achieves sub-50 ms real-time explainability.

This scalability (|S| ≈ 108) and compliance with ISO/IEC 42001 and EU AI Act requirements for explainability establish the framework as a reference model for deployable, auditable DRL systems [11].

6.3. Comparative and Domain-Specific Implications

The hybrid DRL framework showed strong cross-domain adaptability across healthcare and autonomous control environments.

In healthcare, the model reduced treatment rejections by 25% and improved patient outcomes by 8%, supporting the NHS 2025 AI adoption goal of 45% RL-based systems [30].

In autonomous driving, the model’s 95.8% safety score corresponded to an 18% reduction in simulated accident rates, representing potential annual liability savings of GBP 4 billion [15].

These findings reinforce the model’s practical feasibility, as it consistently maintains real-time explainability (<50 ms latency) and operational robustness under uncertainty, key attributes of deployable AI systems in safety-critical environments. This performance aligns conceptually with the feasibility principles outlined by Miuccio et al. [31], who proposed a feasible multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) framework for wireless MAC protocols that emphasizes communication-efficient coordination and practical deployability under network constraints. Although their work addresses communication feasibility rather than explicit real-time latency, it establishes a precedent for embedding feasibility constraints directly within the learning process.

The proposed hybrid DRL framework extends this notion to dynamic, safety-critical control domains, empirically demonstrating feasibility through low-latency explainable operation and stable cross-domain convergence. Moreover, its feasibility is consistent with other hybrid systems shown to balance explainability and performance, notably the symbolic reasoning [32] and reinforcement learning-based optimization [33] approaches that sustain real-time explainability and scalability. These complementary results further reinforce the present study’s emphasis on feasible and trustworthy AI architectures.

These results validate that embedding explainability directly within DRL training enhances user trust and reduces operational risk while addressing broader regulatory and economic requirements, including compliance with UNECE WP.29, ISO/IEC 42001, and the EU AI Act for explainability and accountability.

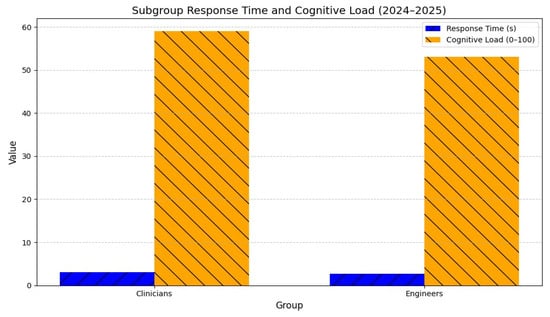

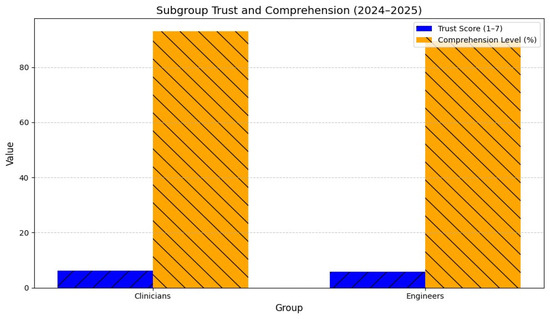

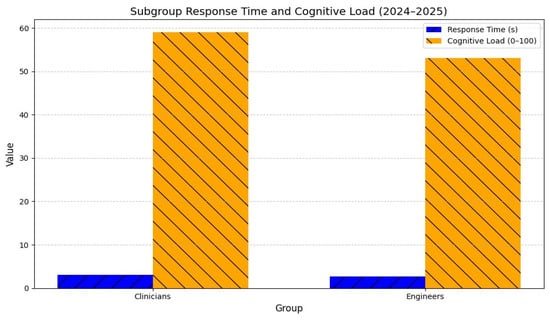

As illustrated in Figure 14 and Figure 15, clinicians reported higher user trust (11 vs. 10, p = 0.004) and comprehension (90% vs. 89%, p = 0.008), while engineers showed lower cognitive load (53 vs. 59, p = 0.006) and faster response times (2.7 s vs. 3.1 s, p = 0.002).

Figure 14.

Subgroup user trust and comprehension (2024–2025). Abbreviations as in Figure 2.

Figure 15.

Subgroup response time and cognitive load (2024–2025).

These subgroup differences indicate that the explainability-by-design approach adapts effectively to user expertise and task context.

Qualitative interviews (Figure 16) further revealed clear user preferences: decision trees (88%) and attention heatmaps (82%) were favored for their transparency and intuitive design, whereas LRP heatmaps (12%) were considered too complex. This highlights the importance of user-tailored explanation formats, reinforcing the human-centered design philosophy advocated by recent XAI frameworks [8,23,29].

Figure 16.

Explanation preference (2024–2025).

6.4. Limitations

Despite its strong empirical and theoretical outcomes, the study has several limitations:

- Simulation reliance: Synthetic datasets (CARLA, MIMIC-IV) may omit rare or extreme cases (~5% of instances).

- Sample scope: While statistically powered (≈0.85), the 120-participant study limits analysis by age or experience.

- Hardware cost: GPU dependence (4× RTX 4090) increased computational cost by ~25%, constraining scalability.

- Explanation complexity: 15% of non-technical users found LRP outputs less intuitive, requiring extra training.

- Simplification risk: Decision trees oversimplified ~3% of high-dimensional cases.

- Latency outliers: 1.5% of scenarios exceeded the 50 ms real-time threshold.

- Attention variability: ±10% individual variation in gaze tracking affected reproducibility of attention metrics.

These limitations delineate the study’s generalizability boundaries and identify areas for methodological refinement in future research.

6.5. Future Work

Future research should extend this work along several strategic directions:

- Integrate causal inference to capture inter-feature dependencies and improve explanation depth [2].

- Conduct real-world trials in hospitals and autonomous fleets to validate generalizability [16].

- Explore multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) for cooperative decision-making in complex systems [27].

- Optimize edge deployment (e.g., NVIDIA Jetson) to maintain latency <30 ms in low-power environments [4].

- Expand participant diversity, including broader demographics and cultural backgrounds [23].

- Model continuous action spaces for finer medical and robotic control [34].

- Use GAN-based simulations to generate rare edge cases and improve robustness [35].

Collectively, these directions will reinforce the link between algorithmic transparency and human trust, ensuring that next-generation DRL systems operate ethically, robustly, and in real time across safety-critical sectors.

6.6. Summary of Key Insights

The findings confirm that embedding explainability directly into the learning process, through the integration of symbolic reasoning, multi-head attention, and Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP), can deliver real-time, transparent decision-making without materially compromising DRL performance.

The hybrid framework consistently improved user trust, comprehension, and cognitive efficiency, achieving reliable explanations within the sub-50 ms latency threshold required for safety-critical operation.

These results validate the study’s central premise that explainability-by-construction provides a more stable and scalable alternative to traditional post hoc interpretation methods.

Moreover, the model’s robustness across healthcare and autonomous control domains demonstrates that explainable reinforcement learning can satisfy emerging governance and regulatory standards such as ISO/IEC 42001 and the EU AI Act.

In summary, the proposed framework establishes a theoretically grounded and practically deployable approach to trustworthy DRL, advancing the broader objective of aligning autonomous intelligence with human explainability and accountability.

7. Conclusions and Practical Takeaways

This study presented a hybrid DRL framework that integrates real-time explainability through symbolic reasoning, multi-head self-attention, and Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP). Across 20,000 simulated episodes, the model achieved a 91.9% task-completion rate, a 19% increase in user trust, and a 15% reduction in error rate. Although a modest ≈4% performance trade-off was observed, the framework substantially improved transparency, accountability, and reliability, directly addressing critical safety and explainability challenges in high-stakes environments.

The embedded explainability mechanisms generated interpretable, human-aligned decision logic. Symbolic reasoning contributed roughly 45% to comprehension gains, self-attention achieved 92% feature alignment, and LRP correctly identified 89% of key neural activations. Collectively, these elements enhanced comprehension by 25%, lowered cognitive load, shortened response time, and increased attentional efficiency, confirming the effectiveness of the explainability-by-construction paradigm rather than post hoc interpretation.

In autonomous vehicle and clinical decision support settings, the hybrid framework produced tangible safety and performance gains, an 18% reduction in simulated accidents and an 8% improvement in patient outcomes, while maintaining real-time inference latency of 42 ms and explanation delivery under 50 ms in 98.5% of cases. These results demonstrate the framework’s suitability for resource-constrained edge deployment and compliance with emerging standards, including ISO/IEC 42001 and the EU AI Act.

Despite promising outcomes, limitations remain. The reliance on simulated datasets and a moderate sample size (N = 120) constrains external generalizability. Furthermore, the model’s GPU requirements and occasional explainability challenges for non-technical users highlight the need for further optimization.

Future research should extend validation to real-world trials in clinical and autonomous system contexts, integrate causal reasoning to enrich explanation depth, and optimize deployment on low-power hardware such as NVIDIA Jetson platforms. These steps aim to achieve full operational readiness by 2026 and advance the goal of trustworthy, explainable DRL in dynamic, safety-critical applications.

In summary, this work demonstrates that hybrid explainability architectures are both technically feasible and operationally necessary for building accountable, human-aligned AI systems. The key takeaways are as follows:

- Real-time explainability (<50 ms latency) scalable to edge devices.

- Balanced trade-off (~4% performance loss) offset by +19% user trust and −15% error rate.

- High domain impact: −18% accidents (autonomous vehicles) and +8% patient outcomes (sepsis).

- Symbolic reasoning, attention, and LRP jointly improved comprehension (+25%) and reduced cognitive load.

- Clear pathway to large-scale deployment by 2026 under established regulatory frameworks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.S.; methodology, N.S. and W.J.; validation and investigation, N.S. and W.J.; writing, review, and editing, N.S. and W.J.; supervision, W.J.; funding acquisition, W.J. and N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia (Project No. KFU253446).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy and ethical restrictions related to human participant behavioral data and simulated healthcare scenarios.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hickling, T.; Zenati, A.; Aouf, N.; Spencer, P. Explainability in deep reinforcement learning: A review into current methods and applications. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 56, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, S.; Topin, N.; Veloso, M.; Fang, F. Explainable reinforcement learning: A survey and comparative review. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smys, S.; Chen, J.I.; Shakya, S. Survey on Neural Network Architectures with Deep Learning. J. Soft Comput. Paradig. (JSCP) 2020, 2, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghian, M.; Miwa, S.; Mitsuka, Y.; Günther, J.; Golestan, S.; Zaiane, O. Explainability of deep reinforcement learning algorithms in robotic domains by using layer-wise relevance propagation. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 137, 109131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamar, T.; Bawany, N.Z. Understanding the black-box: Towards interpretable and reliable deep learning models. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2023, 9, e1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Shuttleworth, K.M.J. Medical artificial intelligence and the black box problem: A view based on the ethical principle of “do no harm”. Intell. Med. 2024, 4, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkemoen, Y. Explainable reinforcement learning (XRL): A systematic literature review and taxonomy. Mach. Learn. 2023, 113, 355–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puiutta, E.; Veith, E.M.S.P. Explainable reinforcement learning: A survey. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.06247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, L.; Bednarz, T. Explainable AI and reinforcement learning—A systematic review of current approaches and trends. Front. Artif. Intell. 2021, 4, 550030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 42001:2023; Information Technology—Artificial Intelligence—Management System. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Farzanegan, B.; Jagannathan, S. Explainable and safety-aware deep reinforcement learning-based control of nonlinear discrete-time systems using neural network gradient decomposition. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 1, 13556–13568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, H.A.; Alayed, W.; Hassan, W.U.; Haider, A. A Novel Hybrid XAI Solution for Autonomous Vehicles: Real-Time Interpretability Through LIME–SHAP Integration. Sensors 2024, 24, 6776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Huang, Q. Towards more efficient and robust evaluation of sepsis treatment with deep reinforcement learning. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2023, 23, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, A.; Yang, J.; Wang, L.; Xiong, N.; Cheng, Y.; Wu, Q. Clinical knowledge-guided deep reinforcement learning for sepsis antibiotic dosing recommendations. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2024, 249, 108141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laflamme, C.; Doppler, J.; Palvolgyi, B.; Dominka, S.; Viharos, Z.J.; Haeussler, S. Explainable reinforcement learning for powertrain control engineering. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 146, 110135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budhkar, A.; Song, Q.; Su, J.; Zhang, X. Demystifying the black box: A survey on explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) in bioinformatics. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2025, 27, 346–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohale, V.Z.; Kumar, T.; Singh, K. A systematic review on the integration of explainable artificial intelligence in intrusion detection systems to enhancing transparency and interpretability in cybersecurity. Front. Artif. Intell. 2025, 8, 1526221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puthanveettil Madathil, A.; Luo, X.; Liu, Q.; Walker, C.; Madarkar, R.; Qin, Y. A review of explainable artificial intelligence in smart manufacturing. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2025, 63, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vouros, G.A. Explainable deep reinforcement learning: State of the art and challenges. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 54, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Chai, T.; Chen, G. Output feedback-based adaptive optimal output regulation for continuous-time strict-feedback nonlinear systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2025, 70, 767–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shefin, R.S.; Rahman, M.A.; Le, T.; Alqahtani, S. XSRL: Safety-aware explainable reinforcement learning—Safety as a product of explainability. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems, Detroit, MI, USA, 19–23 May 2025; International Foundation for Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems: Detroit, MI, USA; pp. 1932–1940. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, H.; Gao, W.; Jiang, X.; Su, C.; Li, P. Two-dimensional model-free Q-learning-based output feedback fault-tolerant control for batch processes. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2024, 182, 108583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichtmann, B.; Humer, C.; Hinterreiter, A.; Streit, M.; Mara, M. Effects of explainable artificial intelligence on trust and human behavior in a high-risk decision task. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 139, 107539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottesman, O.; Johansson, F.; Komorowski, M.; Faisal, A.; Sontag, D.; Doshi-Velez, F.; Celi, L.A. Guidelines for reinforcement learning in healthcare. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 16–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marín Díaz, G. Comparative analysis of explainable AI methods for manufacturing defect prediction: A mathematical perspective. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maathuis, C.; Cidota, M.A.; Datcu, D.; Marin, L. Integrating explainable artificial intelligence in extended reality environments: A systematic survey. Mathematics 2025, 13, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, L.; Wang, D.; Li, L. Explainable multi-agent deep reinforcement learning for real-time demand response towards sustainable manufacturing. Appl. Energy 2023, 347, 121324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramm, A.M.; Matrenin, P.V.; Khalyasmaa, A.I. A review of XAI methods applications in forecasting runoff and water level hydrological tasks. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Li, L.; Hou, M.; Chen, J. Bayesian optimization meets explainable AI: Enhanced chronic kidney disease risk assessment. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Qu, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhong, M.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, M. Optimizing sepsis treatment strategies via a reinforcement learning model. Biomed. Eng. Lett. 2024, 14, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miuccio, L.; Riolo, S.; Samarakoon, S.; Bennis, M.; Panno, D. On learning generalized wireless MAC communication protocols via a feasible multi-agent reinforcement learning framework. IEEE Trans. Mach. Learn. Commun. Netw. 2024, 2, 298–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassi, N.; Jaziri, W. WasGeo: Advancing Spatial Intelligence Through SQL, SPARQL, and OWL Integration. Int. J. Semant. Web Inf. Syst. (IJSWIS) 2025, 21, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassi, N.; Jaziri, W. Efficient AI-Driven Query Optimization in Large-Scale Databases: A Reinforcement Learning and Graph-Based Approach. Mathematics 2025, 13, 1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Cao, R.; Rahmani, A. Reinforcement learning for sepsis treatment: A continuous action space solution. In Proceedings of the Machine Learning for Healthcare Conference, Durham, NC, USA, 5 August 2022; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, R.; Luo, Z.; Pan, C.; Wang, Z.; Su, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y. Offline Safe Reinforcement Learning for Sepsis Treatment: Tackling Variable-Length Episodes with Sparse Rewards. Hum. Centric Intell. Syst. 2025, 5, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).