A Two-Stage Stochastic Optimization Model for Cruise Ship Food Provisioning with Substitution

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We propose a two-stage stochastic optimization model for cruise ship food provisioning. It captures both demand uncertainty and food substitution. The model combines first-stage procurement decisions with second-stage recourse actions. This allows optimal substitution after demand is realized. Our approach minimizes expected costs and offers a practical decision-support tool.

- We solve the stochastic program using the SAA method. Our solution includes a full statistical evaluation of its quality. We establish a statistical lower bound by solving multiple independent SAA problems. We also compute an upper bound by evaluating candidate solutions on a large reference sample. The optimality gap is then estimated from these bounds. This ensures computational tractability and reliability for real-world, large-scale planning.

- We perform extensive sensitivity analyses to derive managerial insights. The results reveal that a higher shortage penalty coefficient leads to a significant reduction in stockouts, while accounting for food salvage value contributes to a reduction in the total cost. Based on these findings, we recommend that cruise operators implement two key strategies: first, adopt a substitution cost structure that permits two-way substitution, as this enhances system flexibility and rationalizes procurement; second, implement a service level constraint of approximately , as this setting optimally balances substitution flexibility with cost control, enhancing both operational resilience and economic efficiency.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Operation Management Related to Food Provisioning on Cruise Ships

2.2. Stochastic Inventory Models with Substitution

2.3. Research Gap

3. Problem Formulation

3.1. Problem Description

3.2. Model Formulation

3.2.1. Two-Stage Stochastic Programming Formulation

3.2.2. SAA Model

3.2.3. Linearized SAA Model

- -

- If then , , ,

- -

- If then , , , thus exactly replicating the behavior of the original max operators.

3.2.4. Lower Bound

3.2.5. Upper Bound

3.2.6. Optimality Gap

3.2.7. Common Random Numbers for Variance Reduction

4. Numerical Experiments

4.1. Parameter Settings

4.2. Convergence Analysis

4.3. Sensitivity Analysis

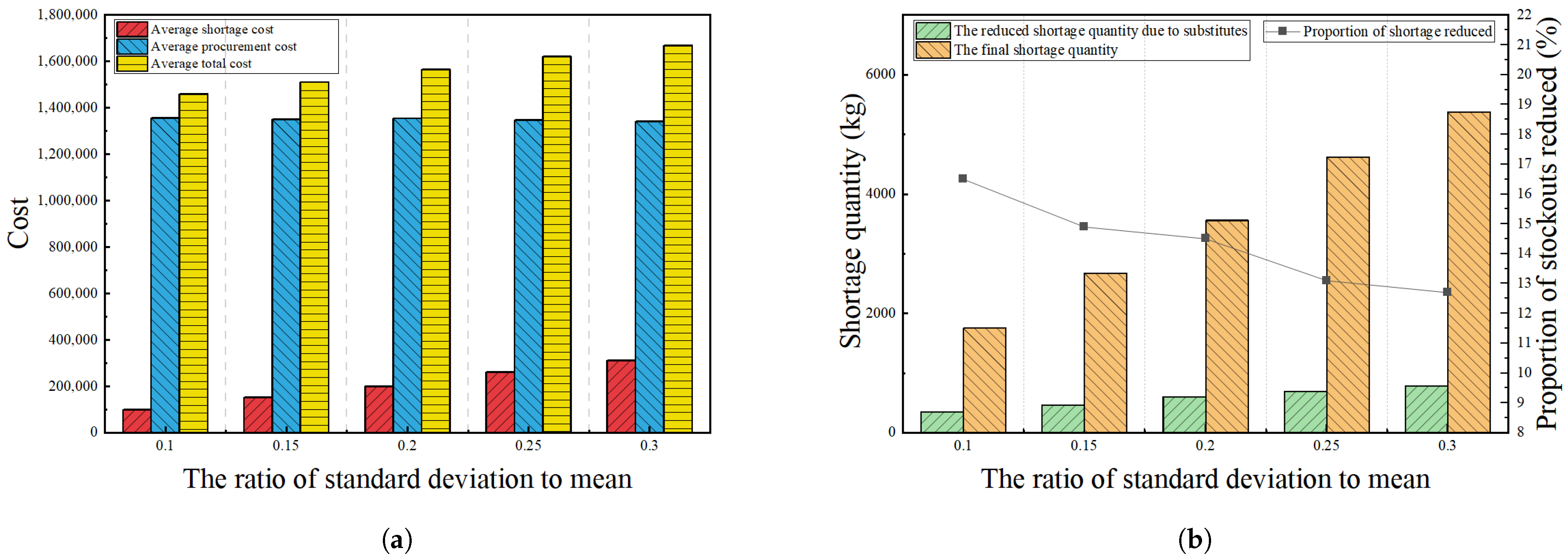

4.3.1. Sensitivity Analysis of Demand Variance

4.3.2. Sensitivity Analysis of Purchase Cost

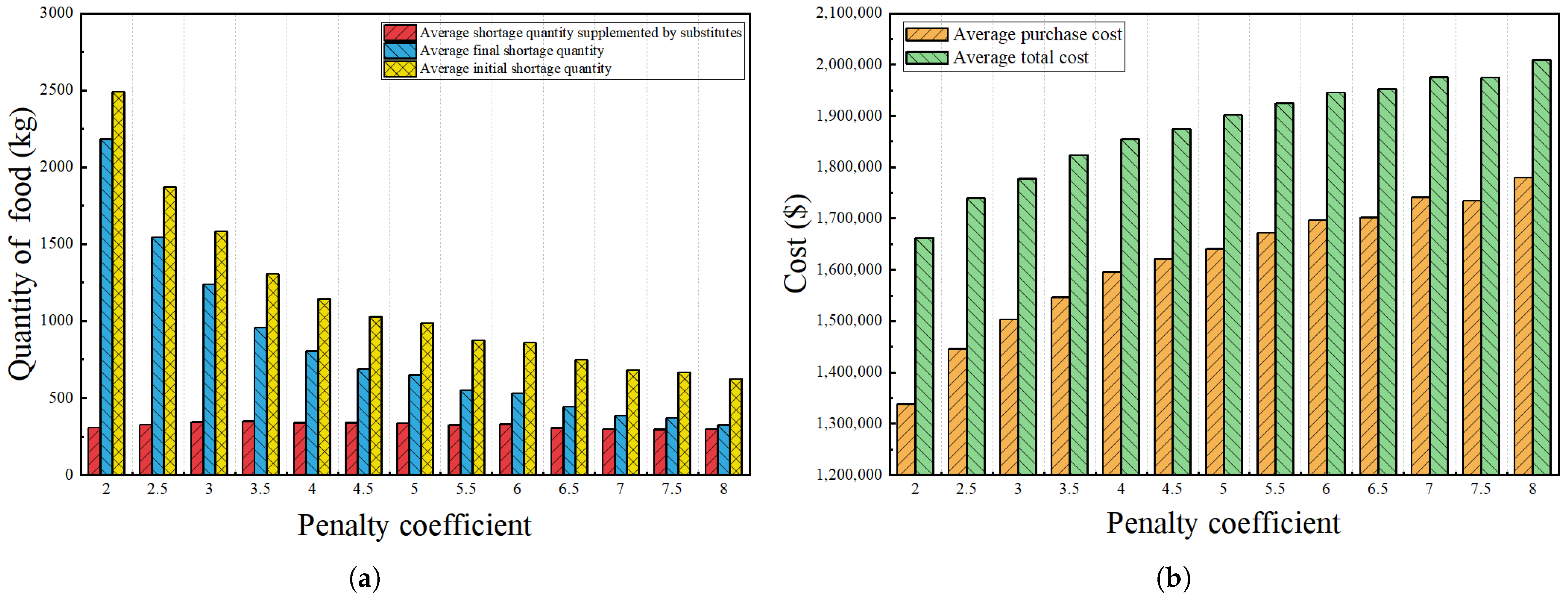

4.3.3. Sensitivity Analysis of Shortage Penalty Coefficient

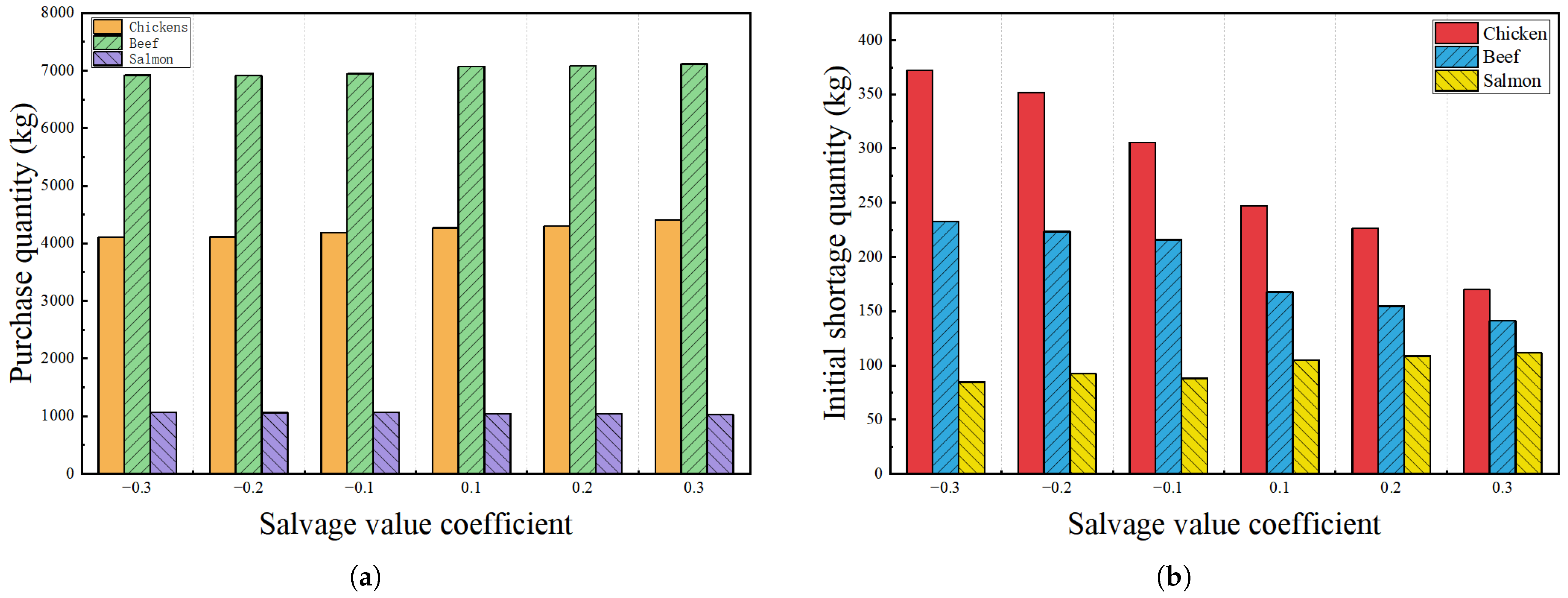

4.3.4. Sensitivity Analysis on Different Salvage Value Coefficient

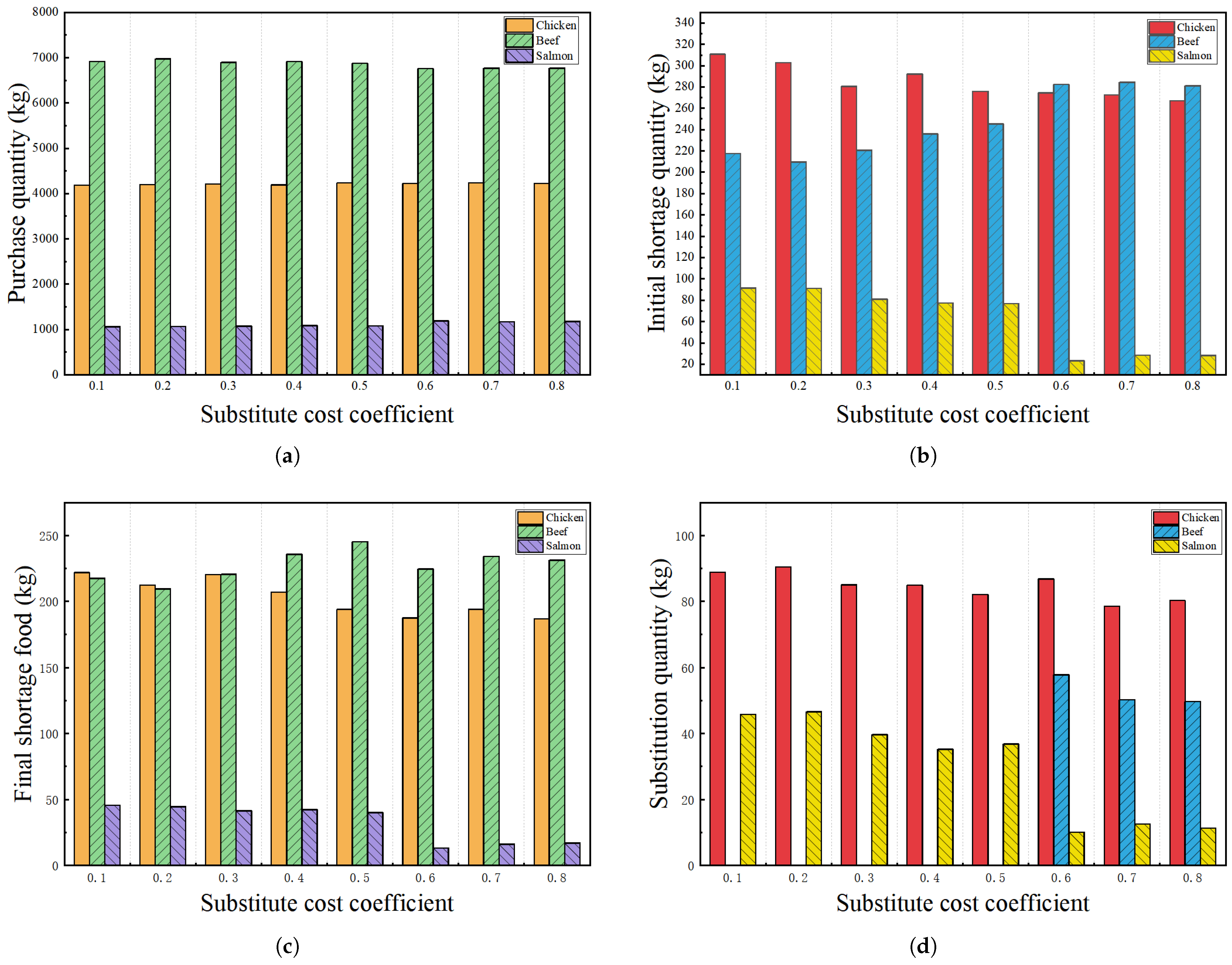

4.3.5. Sensitivity Analysis on Substitute Cost Coefficient

4.3.6. Sensitivity Analysis of Service Level Coefficient

5. Practical Implications

6. Conclusions

- Enhanced demand modeling: Detailed passenger information should be incorporated, including demographics and historical consumption patterns. Correlation analysis between different food items should be conducted to improve forecasting accuracy. Menu engineering principles could also be applied to refine demand projections.

- Algorithmic improvements: Advanced decomposition methods, such as Benders decomposition, should be developed to handle larger problem instances more efficiently. These methods would substantially improve computational performance.

- Machine learning integration: Predictive analytics should be employed to optimize scenario generation processes. These techniques can generate more accurate demand scenarios, thereby enhancing the stochastic optimization framework.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, S. Integrated cruise fleet deployment and itinerary scheduling problem: An enhanced Benders decomposition approach. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2025, 201, 103321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brida, J.G.; Chiappa, G.D.; Meleddu, M.; Pulina, M. A comparison of residents’ perceptions in two cruise ports in the Mediterranean Sea. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 16, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Tan, Y.; Yue, X. Optimizing route and speed under the sulfur emission control areas for a cruise liner: A new strategy considering route competitiveness and low carbon. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.; Wang, S.; Denizci, G.B.; Liu, Z. An overview of cruise tourism research through comparison of cruise studies published in English and Chinese. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Kwortnik, R.; Gauri, D.K. Exploring behavioral differences between new and repeat cruisers to a cruise brand. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 71, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Muñoz, A.; Arjona-Fuentes, J.M.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Han, H.; Law, R. In search of a research front in cruise tourism studies. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 85, 102353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papathanassis, A. Cruise tourism research: A horizon 2050 paper. Tour. Rev. 2025, 80, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Véronneau, S.; Roy, J. Global service supply chains: An empirical study of current practices and challenges of a cruise line corporation. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Wang, J. Food waste of Chinese cruise passengers. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1825–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compact Histories. The History of Passenger Cruises. Available online: https://compacthistories.com/history/the-history-of-passenger-cruises (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Rodrigue, J.P.; Wang, G.W.Y. Cruise ship supply chains and the impacts of disruptions: The case of the Caribbean. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2022, 45, 100551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- My Cruise Ship Info. Golden Harvest Shipping Service Co., Ltd. (Shanghai). Available online: https://www.mycruiseship.info/ship-suppliers/details/golden-harvest-shipping-service-co-ltd-shanghai (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Gu, B.; Liu, J.; Chen, J. Scenario-based strategies evaluation for maritime supply chain resilience. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2023, 124, 103948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wang, S.; Zhen, L.; Qu, X. Cruise ship operations planning and research opportunities. Marit. Bus. Rev. 2016, 1, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Peng, Z.; Xu, W. Robust bi-level optimization for maritime emergency materials distribution in uncertain decision-making environments. Mathematics 2023, 11, 4140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhaya, A.; Telle, J.S.; Schlüters, S.; Saber, M.; von Maydell, K. A robust approach to extend deterministic models for the quantification of uncertainty and comprehensive evaluation of probabilistic forecasting. Int. J. Energy Res. 2025, 2025, 4460462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, S. A data-driven semi-relaxed MIP model for decision-making in maritime transportation. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkoc, M.; Iakovou, E.T.; Spaulding, A.E. Multi-stage onboard inventory management policies for food and beverage items in cruise liner operations. J. Food Eng. 2005, 70, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Chen, S.L.; Shi, W. Identifying risks in the cruise supply chain: An empirical study in Shanghai, China. Transp. Res. Rec. 2023, 2677, 1706–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.; Wu, X. Risk analysis of cruise ship supply chain based on the set pair analysis-Markov chain model. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2023, 245, 106855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasternack, B.A.; Drezner, Z. Optimal inventory policies for substitutable commodities with stochastic demand. Nav. Res. Logist. 1991, 38, 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, M.; Rajagopalan, S. Inventory models for substitutable products: Optimal policies and heuristics. Manag. Sci. 2008, 54, 1453–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahiska, S.S.; Kurtul, E. Modeling and analysis of a product substitution strategy for a stochastic manufacturing/remanufacturing system. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2014, 72, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, U.S.; Swaminathan, J.M.; Zhang, J. Multi-product inventory planning with downward substitution, stochastic demand and setup costs. IIE Trans. 2004, 36, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W.; Bell, P.C. Stochastic optimization models with substitution as a result of price differences and stockouts. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2019, 26, 2129–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biehn, N. A cruise ship is not a floating hotel. J. Revenue Pricing Manag. 2006, 5, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Manzano, J.I.; Castro-Nuño, M.; Pozo-Barajas, R. Foodies on board! Exploring cruiser satisfaction with the culinary experience. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2025, 41, 101238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-de Vivero, J.L.; Rodríguez Mateos, J.C.; Florido del Corral, D.; Barragán, M.J.; Calado, H.; Kjellevold, M.; Miasik, E.J. Food security and maritime security: A new challenge for the European Union’s ocean policy. Mar. Policy 2019, 108, 103640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, A.; Wang, C.J.; Gou, Y.C. Seasonality and spatial patterns of cruise ports from a shipping perspective: A case study of the Mediterranean. J. Chin. Ecotour. 2024, 14, 816–833. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Morales, A.; Cisneros-Martínez, J.D.; McCabe, S. Seasonal concentration of tourism demand: Decomposition analysis and marketing implications. Tour. Manag. 2016, 56, 172–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diabat, A.; Govindan, K.; Panicker, V.V. Supply chain risk management and its mitigation in a food industry. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2012, 50, 3039–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ma, P.; Zhong, W.; Meng, C. Projection-based techniques for high-dimensional optimal transport problems. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 2023, 15, e1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Sridharan, M. A survey of knowledge-based sequential decision-making under uncertainty. AI Mag. 2022, 43, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Jiao, Y.; Tian, P. Marketing research and revenue optimization for the cruise industry: A concise review. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 746–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Stochastic Programming Approaches to Multi-Product Inventory Management Problems with Substitution. Ph.D. Thesis, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2019. Available online: https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/bitstream/handle/10919/95209/Zhang_J_D_2019.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Zhang, J.; Xie, W.; Sarin, S. Multiproduct newsvendor problem with customer-driven demand substitution: A stochastic integer program perspective. INFORMS J. Comput. 2021, 33, 1229–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, Y.-Y.; Yip, T.L. The procurement of food on board liner ships: The role of the International Labour Organization. J. Shipp. Trade 2017, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanova, M. Sustainable Logistics Services of Food Provisions on Merchant Ships; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2025; Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/books/monograph/11185-sustainable-logistics-services-of-food-provisions-on-merchant-ships (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Koren, M.; Perlman, Y.; Shnaiderman, M. Inventory management for stockout-based substitutable products under centralised and competitive settings. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 3176–3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorashi Khalilabadi, S.M.; Zegordi, S.H.; Nikbakhsh, E. A multi-stage stochastic programming approach for supply chain risk mitigation via product substitution. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 149, 106786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasserman, P.; Yao, D.D. Some guidelines and guarantees for common random numbers. Manag. Sci. 1992, 38, 884–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, R.D.; Ramsay, T.E. On the effectiveness of common random numbers. Manag. Sci. 1979, 25, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeding the Largest Cruise Ships in the World. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/travel/article/cruise-ships-food-supplies (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- What It Takes to Stock a Cruise Ship: 10,680 Hot Dogs and a Boatload of Wine. Available online: https://mashable.com/article/cruise-ship-food (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Available online: https://www.usda.gov/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (MARA). Available online: https://www.moa.gov.cn/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Baidu Health. Available online: https://jiankang.baidu.com/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Petruzzi, N.C.; Dada, M. Pricing and the newsvendor problem: A review with extensions. Oper. Res. 1999, 47, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patriarca, R.; Di Gravio, G.D.; Costantino, F.; Tronci, M. EOQ inventory model for perishable products under uncertainty. Prod. Eng. 2020, 14, 601–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, V.K. Optimal ordering quantities for substitutable deteriorating items under joint replenishment with cost of substitution. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2017, 34, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Deniz, B.; Chan, F.T.S.; Caplice, C.; Johnson, M.E. Managing perishables with substitution: Inventory issuance decisions for perishables. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2010, 12, 296–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- How Do Cruise Ships Stock Up on Food (Both in Summer and Winter)? Available online: https://www.cookist.com/how-do-cruise-ships-stock-up-on-food-both-in-summer-and-winter/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- How Is Food Stored on a Cruise Ship? Available online: https://luxurytraveldiva.com/how-is-food-stored-on-a-cruise-ship/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Strijbosch, L.W.G.; Moors, J.J.A. Modified normal demand distributions in (R, S) inventory models. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2003, 84, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Saxena, V.; Singh, J.; Kumari, N. An analytical approach to inventory management under truncated normal demand distribution. Libr. Prog. Int. 2024, 44, 14807–14818. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, F.G.; Rosenhead, J.V.; Siskind, V. The effect of the demand distribution in inventory models combining holding, stockout and re-order costs. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 1971, 33, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertsimas, D.; Gupta, V.; Kallus, N. Robust sample average approximation. Math. Program. 2018, 171, 217–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.; Philpott, A. Improving sample average approximation using distributional robustness. INFORMS J. Optim. 2022, 4, 90–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Methodology | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Erkoc et al. [18] | Multistage inventory replenishment model; Stochastic dynamic programming | Decision-making based on realized demand; No substitution mechanisms; No unified stochastic programming framework |

| Véronneau and Roy [8] | Empirical study; Qualitative analysis of supply chain practices | No mathematical models; No quantitative optimization under uncertainty |

| Zhou et al. [19] | Supply chain risk management; Risk typology classification | Lacks quantitative optimization; No specific decision support tools |

| Meng and Wu [20] | Risk analysis; Set pair analysis–Markov chain model | Focuses on risk assessment rather than operational optimization |

| Pasternack and Drezner [21] | Stochastic inventory models; Substitutable products | General inventory context; Not tailored to cruise operations |

| Nagarajan and Rajagopalan [22] | Inventory models; Substitutable products | No cruise-specific constraints; Limited to moderate substitution levels |

| Ahiska and Kurtul [23] | Hybrid manufacturing-remanufacturing; Markov decision processes | Manufacturing context; Not applicable to cruise provisioning |

| Rao et al. [24] | Multiproduct systems; Two-stage stochastic programming | Industrial-scale focus; No cruise-specific considerations |

| Kim and Bell [25] | Joint pricing and production; Inventory-driven substitution | General retail context; No storage constraints consideration |

| Symbol | Description |

|---|---|

| Sets | |

| N | Set of food types |

| K | Set of storage capacity types (e.g., frozen, refrigerated, ambient) |

| Set of storage types suitable for food item | |

| Set of food items that can substitute for food item | |

| Set of foods that can be stored in storage capacity types | |

| Parameters | |

| Unit procurement cost for food | |

| Unit volume of food | |

| Unit salvage value for surplus of food | |

| Unit penalty cost for shortage of food | |

| Unit penalty cost for substituting 1 kg of i with | |

| Quantity of food j required to substitute for 1 kg of food i | |

| Total volume capacity of storage type | |

| Random variable representing demand for food | |

| Initial shortage of food i before substitution | |

| Initial surplus of food i before substitution | |

| Service level parameter for food item | |

| Decision Variables | |

| First-Stage Variables | |

| Total quantity of food i purchased | |

| Quantity of food i to purchase and store in capacity type | |

| Second-Stage Variables | |

| Amount of shortage of food i fulfilled by substitute | |

| Final leftover quantity (surplus) of food item i after substitution | |

| Food Item | Unit Cost | Unit Volume (m3/kg) | Calories | Weekly Demand (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eggs | 8.10 | 0.0001 | 1310 | 1360.78 |

| Chicken | 20.67 | 0.0010 | 1825 | 1971.63 |

| Beef | 61.13 | 0.0010 | 1250 | 3089.44 |

| Ice Cream | 20.00 | 0.0005 | 2520 | 143.79 |

| Potatoes | 3.50 | 0.0008 | 805 | 4114.26 |

| Flour | 5.50 | 0.0006 | 3600 | 2592.80 |

| Salmon | 75.00 | 0.0012 | 2080 | 514.59 |

| Lobster Tails | 200.00 | 0.0020 | 970 | 432.22 |

| French Fries | 20.00 | 0.0008 | 2000 | 1028.73 |

| Bacon | 55.00 | 0.0010 | 2500 | 1088.89 |

| Tortillas | 10.00 | 0.0005 | 2370 | 2465.62 |

| Chicken Wings | 35.00 | 0.0010 | 2100 | 411.43 |

| Coffee | 125.00 | 0.0002 | 3200 | 308.59 |

| Tea | 200.00 | 0.0002 | 3300 | 308.59 |

| Substituted Food | Substitute Food | Calorie Ratio | Substitution Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chicken | Beef | 1.460 | 2.07 |

| Salmon | 0.877 | 2.07 | |

| Salmon | Beef | 1.664 | 7.50 |

| Potatoes | French Fries | 0.403 | 0.35 |

| Chicken Wings | Bacon | 0.840 | 3.50 |

| Coffee | Tea | 1.000 | 12.50 |

| Number of Scenarios | Obj LB | Obj UB | Gap (%) | LB Std. Dev. (%) | UB Std. Dev. (%) | Time(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 1,443,787.71 | 1,475,263.39 | 2.13 | 1.18 | 0.25 | 0.12 |

| 20 | 1,449,177.39 | 1,477,495.90 | 1.92 | 0.82 | 0.21 | 0.30 |

| 30 | 1,453,118.39 | 1,471,652.35 | 1.26 | 0.81 | 0.20 | 1.06 |

| 40 | 1,456,864.13 | 1,474,720.78 | 1.21 | 0.54 | 0.13 | 1.59 |

| 60 | 1,456,997.59 | 1,474,842.91 | 1.21 | 0.55 | 0.10 | 4.15 |

| 80 | 1,459,413.71 | 1,470,951.34 | 0.78 | 0.64 | 0.07 | 9.39 |

| 100 | 1,459,431.67 | 1,471,970.30 | 0.85 | 0.39 | 0.07 | 17.62 |

| Purchase Cost Coefficient | Purchase Cost | Shortage Cost | Substitution Cost | Total Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.8 | 1,149,321.61 | 230,791.79 | 1519.69 | 1,399,396.28 |

| 0.9 | 1,265,398.26 | 258,653.29 | 1638.12 | 1,541,743.47 |

| 1.0 | 1,343,974.79 | 316,122.14 | 1759.14 | 1,674,964.78 |

| 1.1 | 1,427,816.21 | 365,622.20 | 1883.24 | 1,806,612.59 |

| 1.2 | 1,491,940.08 | 424,120.86 | 1859.91 | 1,927,393.49 |

| Purchase Cost Coefficient | Purchase Quantity (kg) | Initial Shortage Quantity (kg) | Substitution Quantity (kg) | Final Shortage (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.8 | 44,745.11 | 4894.04 | 843.22 | 4050.82 |

| 0.9 | 44,043.24 | 5333.39 | 786.82 | 4546.57 |

| 1.0 | 42,202.85 | 6220.74 | 755.34 | 5465.40 |

| 1.1 | 40,706.49 | 6997.43 | 727.10 | 6270.33 |

| 1.2 | 38,912.81 | 8006.57 | 653.52 | 7353.04 |

| Penalty Coefficient | Initial Shortage Quantity (kg) | Total Substitution Quantity (kg) | Final Shortage Quantity (kg) | Substitution Rate (%) | Total Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.0 | 2490.08 | 306.50 | 2183.58 | 12.3 | 1,662,081.76 |

| 2.5 | 1871.74 | 327.45 | 1544.29 | 17.5 | 1,739,641.40 |

| 3.0 | 1582.72 | 343.60 | 1239.12 | 21.7 | 1,777,561.01 |

| 3.5 | 1305.95 | 348.52 | 957.43 | 26.7 | 1,823,454.27 |

| 4.0 | 1144.42 | 339.27 | 805.14 | 29.6 | 1,854,539.68 |

| 4.5 | 1026.66 | 339.61 | 687.05 | 33.1 | 1,874,298.57 |

| 5.0 | 987.19 | 336.92 | 650.27 | 34.1 | 1,902,127.36 |

| 5.5 | 874.04 | 324.04 | 550.00 | 37.1 | 1,924,294.48 |

| 6.0 | 859.37 | 329.66 | 529.71 | 38.4 | 1,945,550.17 |

| 6.5 | 748.00 | 305.84 | 442.16 | 40.9 | 1,952,583.75 |

| 7.0 | 681.33 | 296.44 | 384.89 | 43.5 | 1,975,310.33 |

| 7.5 | 666.30 | 296.04 | 370.26 | 44.4 | 1,974,891.41 |

| 8.0 | 622.23 | 298.68 | 323.54 | 48.0 | 2,009,200.58 |

| Purchase Cost | Purchase Cost Proportion (%) | Shortage Cost | Shortage Cost Proportion (%) | Substitution Cost | Salvage Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,344,943.95 | 91.40 | 114,414.84 | 7.78 | 865.96 | ||

| 1,349,126.11 | 92.09 | 106,685.48 | 7.28 | 928.78 | ||

| 1,356,786.32 | 92.80 | 99,875.77 | 6.83 | 949.55 | ||

| 0.1 | 1,373,900.92 | 94.43 | 85,280.72 | 5.86 | 1079.09 | 5353.01 |

| 0.2 | 1,378,209.37 | 95.36 | 77,725.26 | 5.38 | 1079.56 | 11,721.60 |

| 0.3 | 1,388,411.46 | 96.38 | 70,149.59 | 4.87 | 1088.94 | 19,060.90 |

| Salvage Value Coefficient | Chicken | Beef | Salmon |

|---|---|---|---|

| 268.11 | 232.45 | 46.60 | |

| 248.35 | 223.18 | 48.51 | |

| 209.04 | 215.67 | 43.23 | |

| 0.1 | 162.57 | 167.66 | 48.93 |

| 0.2 | 144.92 | 154.53 | 48.66 |

| 0.3 | 102.87 | 140.98 | 48.80 |

| Substitute Cost Coefficient | Purchase Cost | Shortage Cost | Substitution Cost | Salvage Value | Total Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 1,354,042.93 | 101,915.75 | 925.23 | 1,461,274.07 | |

| 0.2 | 1,357,367.44 | 100,668.91 | 1867.38 | 1,464,333.44 | |

| 0.3 | 1,353,940.29 | 99,636.84 | 2476.22 | 1,460,452.36 | |

| 0.4 | 1,355,762.07 | 102,173.49 | 3117.38 | 1,465,445.34 | |

| 0.5 | 1,354,269.72 | 103,916.41 | 4178.67 | 1,466,802.27 | |

| 0.6 | 1,356,744.51 | 94,305.09 | 5693.65 | 1,461,321.96 | |

| 0.7 | 1,353,703.05 | 97,497.01 | 6335.24 | 1,462,080.59 | |

| 0.8 | 1,352,952.26 | 95,324.02 | 8097.53 | 1,460,999.28 |

| Service Level Coefficient | Initial Shortage Quantity (kg) | Final Shortage Quantity (kg) | Substitution Quantity (kg) | Substitution Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.95 | 2003.73 | 1812.53 | 191.20 | 9.5 |

| 0.90 | 2103.52 | 1828.32 | 275.20 | 13.1 |

| 0.85 | 2090.99 | 1761.07 | 329.92 | 15.8 |

| 0.80 | 2132.21 | 1788.35 | 343.86 | 16.1 |

| 0.75 | 2165.67 | 1826.91 | 338.76 | 15.6 |

| Service Level Coefficient | Purchase Cost | Shortage Cost | Substitution Cost | Salvage Value | Total Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.95 | 1,358,386.85 | 105,953.05 | 414.06 | −4589.57 | 1,469,343.53 |

| 0.90 | 1,355,774.57 | 103,024.11 | 693.42 | −4357.47 | 1,463,849.57 |

| 0.85 | 1,358,232.36 | 100,862.85 | 917.17 | −4471.64 | 1,464,484.02 |

| 0.80 | 1,354,790.34 | 100,022.43 | 957.14 | −4402.20 | 1,460,172.11 |

| 0.75 | 1,352,452.37 | 102,306.58 | 988.63 | −4329.20 | 1,460,076.78 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, W.; Yang, Y.; Wang, S. A Two-Stage Stochastic Optimization Model for Cruise Ship Food Provisioning with Substitution. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3806. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233806

Sun W, Yang Y, Wang S. A Two-Stage Stochastic Optimization Model for Cruise Ship Food Provisioning with Substitution. Mathematics. 2025; 13(23):3806. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233806

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Weilin, Ying Yang, and Shuaian Wang. 2025. "A Two-Stage Stochastic Optimization Model for Cruise Ship Food Provisioning with Substitution" Mathematics 13, no. 23: 3806. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233806

APA StyleSun, W., Yang, Y., & Wang, S. (2025). A Two-Stage Stochastic Optimization Model for Cruise Ship Food Provisioning with Substitution. Mathematics, 13(23), 3806. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233806