Polarities of Exceptional Geometries of Type

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

1.2. Structure of the Paper

2. Main Results

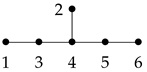

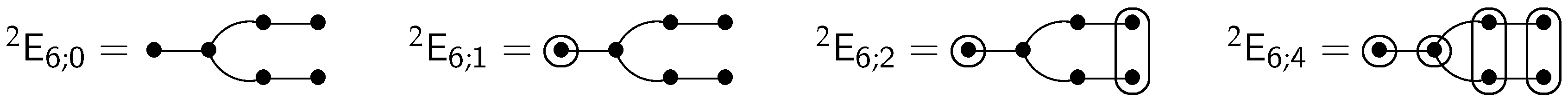

2.1. Fix Diagrams

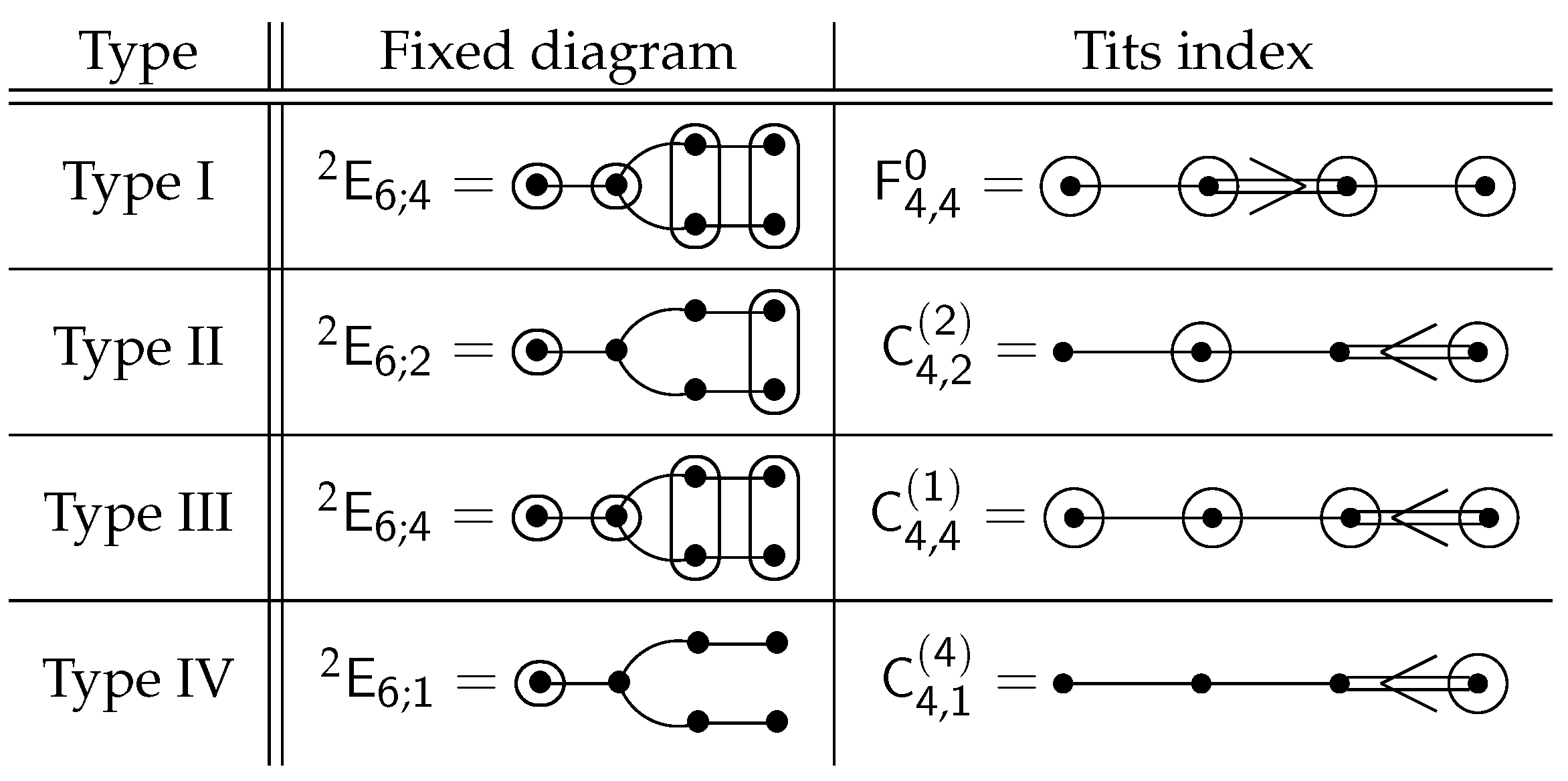

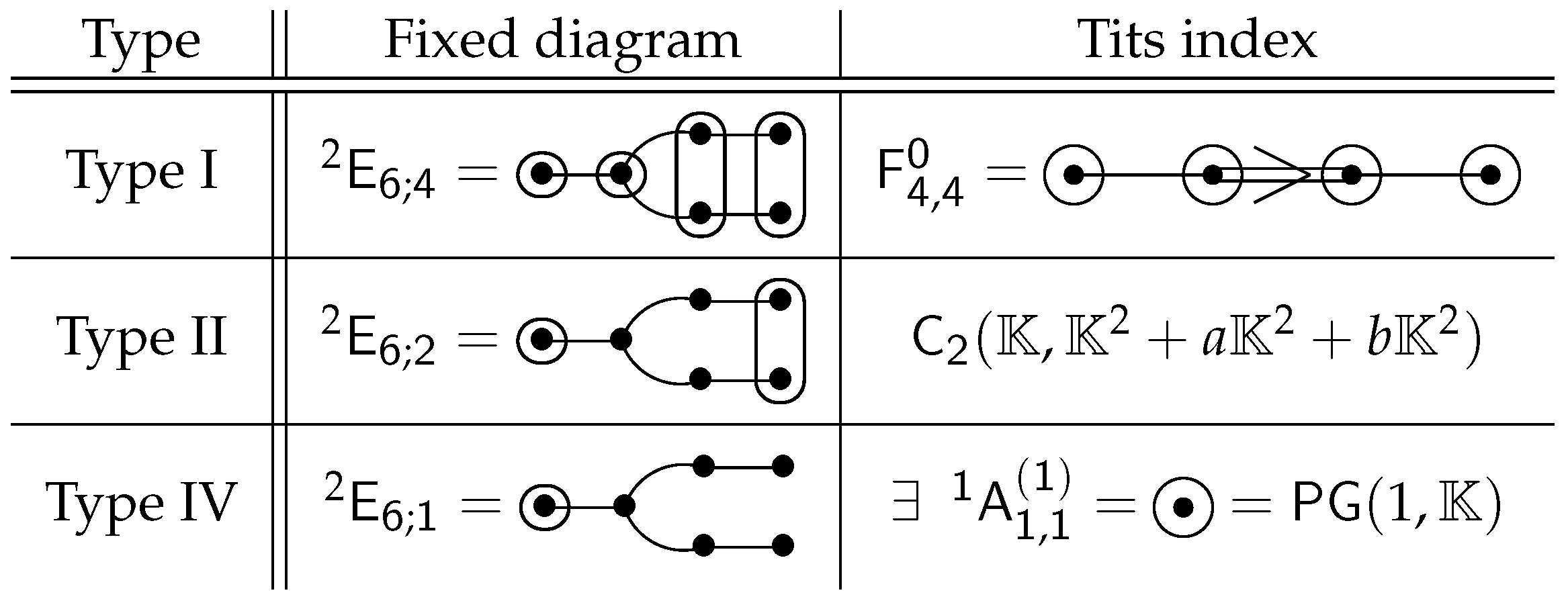

2.2. Tits Indices

2.3. Moufang Buildings

2.4. Preview of the Main Results

2.5. Main Results

2.6. Some More Discussion

3. Preliminaries

3.1. Buildings and Point-Line Geometries

3.2. Projective Spaces

- (i)

- , the set of fixed points is a subspace , the set of hyperplanes is the set of hyperplanes containing a given subspace , and .

- (ii)

- and the set of fixed points is the union of two disjoint subspaces U and , with .

3.3. Hyperbolic Quadrics

3.4. Geometries of Type

- (i)

- Either , or there is a unique line containing both x and y, or x and y are not collinear and there is a unique symp containing both x and y;

- (ii)

- Either , or is a 4-space, or is a point;

- (iii)

- Either , or x is contained in a unique 5-space that intersects ξ in a maximal singular subspace distinct from a 4-space, or x is not collinear to any point of ξ.

- (i)

- and ;

- (ii)

- and .

3.5. Summary of Notation

- *

- Collinear points x and y are denoted as , and the set of points collinear to x is denoted as . A point is always collinear to itself.

- *

- A building of simply laced type , defined over the field , is denoted as . The corresponding Lie incidence geometry using the vertices of type i as points is denoted as .

- *

- The projective space of dimension n over the field is denoted by and is isomorphic to the Lie incidence geometry .

- *

- The subspace generated by a set S of points in a projective space is denoted by ; it is the intersection of all subspaces containing S.

- *

- The unique symp in containing two given non-collinear points x and y is denoted as .

- *

- The unique symp in incident with two given 5-spaces intersecting in a unique point is denoted as .

4. Linear Polarities of the Triality Quadric

- (i)

- ρ is a parabolic polarity;

- (ii)

- The fix structure of ρ is a subquadric of Witt index 1 which is the intersection with of a 4-dimensional subspace of , and no maximal singular subspace is adjacent to its image under ρ;

- (iii)

- The set of fixed points is the union of a conic and its perp. The latter is a subspace isomorphic to .

- (0)

- . If , then and every singular 3-space of Q through U is preserved, implying that is type-preserving, a contradiction. Hence and U does not belong to Q. Then we have situation .

- (1)

- . As in , leads to a contradiction. Hence again. Since , we find that . Suppose first that U intersects Q in two points . Then every singular 3-space of Q through x intersects in a plane and hence is stabilized by . This again implies that is type-preserving, a contradiction. Suppose now that U and Q are disjoint. Set . Since , is non-degenerate. Since , the Witt index of is at least 2. Suppose contains a plane . Then . The latter is a 4-space containing the two singular 3-spaces of Q through . Hence U intersects each of these singular 3-spaces, a contradiction. Consequently has Witt index 2. Now let W be a maximal singular subspace of Q containing a line L of . Since L is fixed pointwise and is a polarity, we deduce that is a plane, stabilized by . Since and pointwise fixes the line L of , it fixes an additional point of , which necessarily has to lie in . But this is impossible as . This shows that this case does not arise.

- (2)

- . As in , leads to a contradiction. Hence, and so is a non-degenerate conic. If that conic is non-empty, then we have situation . So, we may assume that is empty. Similarly as in , one shows that is a non-degenerate quadric of Witt index 1. Each maximal singular subspace W of Q intersects in a point. Reference Lemma 3 implies that is either a point or a line. If is a line, is type-preserving, a contradiction. Hence is always a point, leading to .

- (3)

- . As in , is non-degenerate. Using similar arguments as above, one shows that the Witt indices of and coincide. If this Witt index is 0, then there are no fixed points, contradicting Lemma 4. If the Witt index is 1, then consider a line L intersecting U and non-trivially, say in the respective points u and . Since L is stabilized by , similarly to above, we find a fixed plane, which only contains two fixed points (u and ), contradicting Lemma 2. Finally, assume that the Witt index of both and is equal to 2. Then each maximal singular subspace spanned by a line of and one of is fixed. This implies that would be type-preserving, a contradiction.

- (i)

- ρ is a parabolic polarity, that is, ρ is the unique non-trivial collineation pointwise fixing a given non-degenerate hyperplane of ;

- (ii)

- The fixed structure of ρ is a subquadric P of Witt index 1, which is the intersection with of a 4-dimensional subspace of ; it has a plane nucleus, and no maximal singular subspace is adjacent to its image under ρ;

- (iii)

- The set of fixed points is the intersection of with a 4-dimensional subspace U and has the structure of a cone with vertex some point x and base a quadric of Witt index 1 in a hyperplane of U. No maximal singular subspace not through x is mapped onto an adjacent one, whereas each maximal singular subspace through x is mapped onto an adjacent one.

- (iv)

- The set of fixed points is the intersection of with a 4-dimensional subspace U and has the structure of a cone with vertex some line K and base a non-degenerate conic in some plane of U. A maximal singular subspace is mapped onto an adjacent one if, and only if, it is not disjoint from the line K.

- (0)

- . Here, is a point off Q, and this leads to situation .

- (1)

- . Here, is a line. Then is 5-dimensional and hence intersects every maximal singular subspace in at least a line, which is consequently fixed by . Hence, since is type-interchanging, corresponding maximal singular subspaces intersect in a plane. Reference Lemma 10 leads to .

- (2)

- . Suppose first . Since , at least one point per maximal singular subspace is fixed. If a singular line L were pointwise fixed, then, since , we would find . The latter is a 5-space intersecting Q in a quadric with radical L. This implies that , and hence also , is not disjoint from Q, a contradiction. Using Lemma 2, this leads to . Now suppose . Similarly as in the previous case, one shows that no line disjoint from is pointwise fixed by . Hence, also similarly, each maximal singular subspace W not containing x contains exactly one fixed point . So, using Lemma 2 again, we deduce that is not a plane. We conclude . Now let W be a maximal singular subspace containing x. Then , with M a line in not through x. This implies that some line of W through x is pointwise fixed, and so, is a plane . That plane cannot be pointwsie fixed, as otherwise , which is the union of two hyperplanes, contains , contradicting . This is situation . Similarly, leads to situation .

- (3)

- . Since every maximal singular subspace of Q is also singular with respect to , the intersection is a singular subspace of Q. Hence there exists a maximal singular subspace W of Q disjoint from . This implies that no point of , which is globally stabilized, is fixed. Hence is not a point, and, by Lemma 2, it is not a plane either. This contradicts the fact that is not type-preserving.

5. Proofs of Theorems 1 and 2

5.1. Fix Diagrams

- (i)

- is a plane π.Select . Then , since preserves the incidence relation. Hence x is absolute, and fixes a 5-space by Lemma 11, a contradiction to our assumptions.

- (ii)

- is a point x. Then clearly x is mapped onto the unique symp incident with both W and , which contains x. Again, Lemma 11 leads to a contradiction.

- (iii)

- and W is not opposite .Then there is a unique 5-space that intersects both W and in some plane. Clearly, fixes , again a contradiction.

- Let W be a 5-space, fixed by ρ. Then ρ induces a polarity in W, and we denote that polarity as . Every absolute point for ρ in W is an absolute point for , and, conversely, every absolute point for is an absolute point for ρ. Note that planes of W fixed under ρ correspond to planes of Δ fixed under .

- Let x be an absolute point for ρ. Then ρ induces a polarity in the residue at and we denote that polarity as . A fixed point for corresponds to a stabilized 5-space for ρ through x and incident with . Also, a line of the residue at fixed by corresponds to a plane of Δ fixed by ρ. Remember also that the two oriflamme classes of maximal singular subspaces of the residue at correspond to the set of lines of through x and the set of 4-spaces in through x, respectively.

- (a)

- is a symplectic polarity;

- (b)

- and is an orthogonal polarity with absolute geometry ;

- (c)

- and is an orthogonal polarity of Witt index 1, hence with absolute geometry a non-ruled non-degenerate non-empty quadric;

- (d)

- and is a pseudo polarity with absolute point set an absolute hyperplane;

- (e)

- and is a pseudo polarity with absolute point set an absolute 3-space;

- (f)

- and is a pseudo polarity with absolute point set a plane fixed by ;

- (g)

- and is a pseudo polarity with absolute point set a non-absolute line;

- (h)

- and is a pseudo polarity with a unique absolute point;

- (j)

- is an anisotropic polarity.

5.2. Fixing Metasymplectic Spaces in Characteristic Different from 2

| Type of | Type of |

| Type I | Type A or D |

| Type II | Type C, G or H |

| Type III | Type A, B, D, E or F |

| Type IV | Type A, D, E |

5.3. Fixing a Generalized Quadrangle in Characteristic Different from 2

. Also, the fixed points of in the residue at form a quadric of Witt index 1 in a 4-dimensional space. Hence, over a suitable splitting field, this turns into a parabolic quadric of Witt index 2. Hence the Tits index of the fixed quadric is

. Also, the fixed points of in the residue at form a quadric of Witt index 1 in a 4-dimensional space. Hence, over a suitable splitting field, this turns into a parabolic quadric of Witt index 2. Hence the Tits index of the fixed quadric is  , which coincides with

, which coincides with  . Note that there is, in fact, also a component of rank 1, type , which is determined by the orthogonal complement of the previously mentioned 4-space. This now implies that, over a common splitting field, becomes of type III and hence is a form of . The above Tits indices paste together as the index :

. Note that there is, in fact, also a component of rank 1, type , which is determined by the orthogonal complement of the previously mentioned 4-space. This now implies that, over a common splitting field, becomes of type III and hence is a form of . The above Tits indices paste together as the index :

5.4. Fixing a Rank 1 Building in a Characteristic Different from 2

5.5. Regular Polarities in Characteristic 2

- (Type I)

- The type of is I, for all absolute points x, and the type of is A, for all fixed 5-spaces W;

- (Type II)

- The type of is II, for all absolute points x, and the type of is G, for all fixed 5-spaces W.

- (Type IV)

- There are no absolute points, but there are fixed 5-spaces W; all corresponding polarities are anisotropic.

6. Concrete Constructions; Existence

6.1. Representation of Polarities

6.2. The 9-Space Associated with a Dual Point

6.3. Explicit Form of Some Polarities of

6.3.1. Polarities of Type I—Symplectic Polarities

6.3.2. Polarities of Type III in Characteristic Unequal to 2

6.3.3. Polarities of Type II in All Characteristics

6.3.4. Polarities of Type IV

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tits, J. Les “formes réelles” des groupes de type E6. In Séminaire Bourbaki; 1957/1958, exp. no 162 (février 1958), 15 p., 2e éd. corrigée, Secrétariat mathématique, Paris 1958; reprinted in Séminaire Bourbaki 4; Société Mathématique de France: Paris, France, 1995; pp. 351–365. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, J.A.; Gray, A. Homogeneous spaces defined by Lie groups automorphisms I. J. Differ. Geom. 1968, 2, 77–114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Antón-Sancho, Á. Involutions of the moduli space of principal E6-bundles over a compact Riemann surface. Axioms 2025, 14, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antón-Sancho, Á. Fixed points of principal E6-bundles over a compact algebraic curve. Quaest. Math. 2024, 47, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antón-Sancho, Á. Higgs pairs with structure group E6 over a smooth projective connected curve. Results Math. 2025, 80, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, K.S.; Bajc, B.; Susič, V. A realistic theory of E6 unification through novel intermediate symmetries. J. High Energy Phys. 2024, 2024, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramenko, P.; Brown, K. Buildings: Theory and Applications; Graduate Texts in Mathematics 248; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tits, J. Buildings of Spherical Type and Finite BN-Pairs; Springer Lecture Notes Series; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1974; Volume 396. [Google Scholar]

- Bourbaki, N. Lie Groups and Lie Algebras, Chapters 4–6. Elements of Mathematics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tits, J. Classification of simple algebraic groups. In Algebraic Groups and Discontinuous Subgroups, Proceedings of the Summer Mathematical Institute, Boulder, Colorado, 5 July–6 August 1965; Proceedings of Symposia in Pure Mathematics, Volume 9; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 1966; pp. 33–62. [Google Scholar]

- Tits, J. Groupes de rang 1 et ensembles de Moufang. Annu. Coll. Fr. 2000, 100, 93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Tits, J.; Weiss, R. Moufang Polygons; Springer Monographs in Mathematics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mühlherr, B.; Petersson, H.P.; Weiss, R.M. Descent in Buildings; Annals of Mathematics Studies; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA; Oxford, UK, 2015; Volume 190. [Google Scholar]

- Mühlherr, B.; Van Maldeghem, H. Exceptional Moufang quadrangles of type . Canad. J. Math. 1999, 51, 347–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschbacher, M. The 27-dimensional module for , I. Invent. Math. 1987, 89, 159–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.M. Point-line spaces related to buildings. In Handbook of Incidence Geometry: Buildings and Foundations; Buekenhout, F., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995; Chapter 12; pp. 647–737. [Google Scholar]

- Devillers, A.; Parkinson, J.; Van Maldeghem, H. Automorphisms and opposition in twin buildings. J. Aust. Math. Soc. 2013, 94, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hughes, D.R.; Piper, F.C. Projective Planes; Springer: New York, NY, USA; Heidelberg/Berlin, Germany, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson, J.; Van Maldeghem, H. Automorphisms and opposition in spherical buildings of classical type. Adv. Geom. 2024, 24, 287–321. [Google Scholar]

- Tits, J. Sur la géometrie des R-espaces. J. Math. Pure Appl. 1957, 36, 17–38. [Google Scholar]

- Springer, T.A.; Veldkamp, F. On Hjelmslev-Moufang planes. Math. Z. 1968, 107, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shult, E.E. Points and Lines: Characterizing the Classical Geometries; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer, A.E.; Cohen, A.M.; Neumaier, A. Distance-Regular Graphs; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Van Maldeghem, H. Symplectic polarities in buildings of type . Des. Codes Cryptogr. 2012, 65, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienst, K.J. Verallgemeinerte Vierecke in Pappusschen projektiven Räumen. Geom. Dedicata 1980, 9, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinali, I.; Giuzzi, L.; Pasini, A. Nearly all subspaces of a classical polar space arise from its universal embedding. Lin. Alg. Appl. 2021, 627, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Maldeghem, H.; Victoor, M. On Severi varieties as intersections of a minimum number of quadrics. Cubo 2022, 24, 307–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooperstein, B.N.; Shult, E.E. Frames and bases of Lie incidence geometries. J. Geom. 1997, 60, 17–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasikova, A.; Shult, E.E. Absolute embeddings of point-line geometries. J. Algebra 2001, 238, 265–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Batens, V.; Van Maldeghem, H.

Polarities of Exceptional Geometries of Type

Batens V, Van Maldeghem H.

Polarities of Exceptional Geometries of Type

Batens, Vincent, and Hendrik Van Maldeghem.

2025. "Polarities of Exceptional Geometries of Type

Batens, V., & Van Maldeghem, H.

(2025). Polarities of Exceptional Geometries of Type