Abstract

This paper considers the question of local dynamics of the simplest non-periodic chains of nonlinear first-order equations with two-sided couplings. The main attention is paid to the study of chains with a large number N of elements. The critical cases in the problem of stability of the zero equilibrium state are identified. Questions about bifurcations of regular and irregular solutions are considered. Analogues of normal forms are constructed, the so-called quasinormal forms, which are special nonlinear equations of parabolic type. Their nonlocal dynamics determine the local structure of solutions to the original problem. Bifurcation problems for quasinormal forms are considered, and interestingly, the boundary conditions for them are not classical. The asymptotics of both regular and irregular solutions are constructed. The latter have the most complex structure. In particular, for negative values of the coupling parameter between elements, continual families of equilibrium states, cycles, and more complex structures can arise in the chain.

MSC:

34K25

1. Introduction

We consider a set of identical elements that are described by the simplest first order nonlinear ordinary differential equation

where , and the function is sufficiently smooth. It has an order of smallness higher than first at zero, i.e., in a neighborhood of the zero equilibrium state, and it is represented as follows:

We consider two different chains of coupled identical elements, each of which is described by Equation (1), and their difference consists only of the couplings between the elements.

The first type of chains is characterized by one-sided couplings, i.e., we consider a system of N equations

where and, at the right end of the chain for , the following boundary condition is satisfied:

The second type of chains of elements is due to two-sided couplings:

where , and, for the boundary elements and , the following boundary conditions hold:

Chains of the form (2) and (4) are important objects for research. They are given special attention. Such chains arise in modelling of many applied problems in radio-physics [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9], laser physics [10,11,12,13], mathematical ecology [14,15], the theory of neural networks [16,17,18,19,20,21], optics [3,8,22,23], biophysics [24] and others.

Although most of the works are devoted to the study of relatively small chains, i.e., chains consisting of a small number of elements [25,26,27,28,29], a number of works [25,26,27,28,29,30,31] particularly emphasized the need to study chains with a large number of elements. We also note that chains with an infinite number of elements have also been considered [32].

The main assumption in this work is that the number of elements in the chains is sufficiently large, i.e., Therefore, the small parameter is the quantity

Let us consider the question of the behavior for sufficiently small and of all solutions of the boundary value problems (2), (3) and (4), (5) with initial conditions from some sufficiently small neighborhood of the zero equilibrium state.

Let us introduce the boundary value problems linearized at zero for (2), (3) and (4), (5):

The characteristic equation for the boundary value problem (6) has the form

and the characteristic equation of the boundary value problem (7) is written in the form of two equations

Proposition 1.

In the case when all roots of the characteristic equation have negative real parts that are separated from zero as , all solutions tend to zero as If the characteristic equation has a root with a positive real part separated from zero as , then the zero solution is unstable.

It is convenient to relabel the elements using a function of two variables where are uniformly distributed points on the segment

Passing to the continuous variable the systems (2), (3) and (4), (5) can be written in the form of the equation

with boundary conditions

and the equation

with boundary conditions

respectively.

The boundary value problems linearized at zero for have the respective forms

Obviously, for the boundary value problems (12), (13), an analogue of Proposition 1 holds.

Let us formulate a simple statement.

Theorem 1.

The paper is devoted to the study of local dynamics of the boundary value problems (10), (11) and (12), (13) in critical cases when the values of the parameter are asymptotically close to the value of the parameter a as .

It consists of two sections. The first section investigates equations with one-sided couplings, whereas the second investigates equations with two-sided couplings.

The standard methodology for studying the behavior of solutions in critical cases is the application of methods of local invariant manifolds and the method of normal forms (see, for example, [33,34]). Using the first of these methods, the original system is reduced to a simpler one whose dimension coincides with that of the critical case, and, using the method of normal forms, the latter is transformed into the most convenient form for research. In some of the problems considered in this work, this approach is not directly applicable. The point is that the critical case can have an infinite dimension (asymptotically large as ). In this connection, the method of quasinormal forms developed in [14,35] is applied, i.e., the method of constructing distributed (infinite-dimensional) nonlinear boundary value problems, whose nonlocal dynamics describe the local behavior of solutions to the original problem for small values of the parameter The main result constitutes the construction of the so-called quasinormal forms, which are analogues of normal forms for the infinite-dimensional case.

It should be especially noted that we do not study exact solutions to boundary value problems, but asymptotic solutions or families of solutions that satisfy the original boundary value problem with a high degree of accuracy.

2. Chains with One-Sided Couplings

We will consider the critical case in the stability problem when the characteristic Equation (8) has no roots with positive real parts, but there exists a root with a zero real part.

Since the parameter a is positive, for sufficiently small values of the parameter b, all roots of the characteristic Equation (8) have negative real parts. With , we denote the smallest positive value of the parameter b for which the characteristic Equation (8) has a root with a zero real part. If such a value does not exist, we set Correspondingly, with , we denote the largest negative value of b (if it does not exist, we set ). Thus, for , all roots have negative real parts.

Let us introduce two more quantities: and which are “similar” to and , respectively. For small values of , all roots of the characteristic Equation (8) have negative real parts. With , we denote the smallest positive value of the parameter for which the characteristic Equation (8) has a root with a zero real part. If such a value does not exist, we set Correspondingly, with , we denote the largest negative value of (if it does not exists, we set ). Thus, for , all roots of the characteristic Equation (8) have negative real parts.

In Section 2.1 and Section 2.2, we study the cases when and In particular, for these cases, the values of and will be determined. In Section 2.3, we present results for arbitrary In Section 2.4, which is central to this work, it is assumed that the number of equations N is sufficiently large, i.e.,

In terms of one of the important generalizations of the chain model (10), (11), we note that the obtained results also extend to chains of equations with other one-sided couplings

in which, as for the chain (10),

We note that chains for which the “periodicity” condition is satisfied

were studied in [36]. Let us immediately emphasize that the boundary condition (3) (11) for fundamentally complicates the dynamic properties of the system (2) (10).

2.1. The Case

This case is the simplest. We consider a system of two equations

For , we have Thus, for all b, the roots of the characteristic equation for (15) have negative real parts.

We arbitrarily fix the value of and introduce a small parameter Let us set in (17)

Then, in the characteristic Equation (8) corresponding to (14), there is one negative root (separated from zero, as ) and one root close to zero:

For small , in the phase space of system (17), there exists a local invariant one-dimensional stable integral manifold (see, for example, [33]), on which system (17) (under a certain non-degeneracy condition) takes the form of a scalar ordinary differential equation up to terms of order

where is a “slow” time, and the function is related to the solutions of (17) by the asymptotic equality

For , Equation (19) has a non-zero equilibrium state It is stable for and unstable for Therefore, system (17) for , under condition (18), and for sufficiently small , has an equilibrium state

which is stable (unstable) for In the considered case close to critical, Equation (19) is called the normal form. The above-mentioned non-degeneracy condition is For and , the changes are inessential. In the normal form, the quadratic term is replaced by a cubic one, and the asymptotic expansion, i.e., an analogue of (20), goes in powers of

Thus, the study of local dynamics of system (17) is complete.

For system (17), we give the values of and

2.2. The Case

System (2), (3) for takes the form

For the linearized system

the roots , and of the characteristic equation are determined by the relations

where is the arithmetic root ( for and for ).

For the values of , we have

We give the values of the quantity

Under the conditions , the roots (23) have negative real parts, and, for and and , among the roots (23) there is a root with a positive real part. Under the conditions , critical cases of the zero root or critical cases of a pair of purely imaginary roots arise in the stability problem for solutions of (21). Let us consider them.

2.2.1. The Critical Case of Zero Root

This case arises under the condition when and , or when and We limit ourselves to considering only the first of the given conditions, i.e., below we assume that

The linear system (22) for has constant solutions where

We fix arbitrarily the value of and set

in (21). Then, the roots and have negative real parts for small : and for the root , we have the asymptotic equality:

This implies that in a sufficiently small neighborhood of the zero equilibrium state of system (21), independent of , there exists a stable local invariant one-dimensional integral manifold, on which this system can be represented up to in the form of a normal form (under the fulfillment of a certain non-degeneracy condition)

To determine the coefficients and , we substitute into (21) the solution in the form of an asymptotic series

Collecting coefficients at the first power of in the resulting formal identity, we obtain a correct equality, and taking into account the coefficients at we arrive at a system for determining the function

Here and below, multiplication of vectors is calculated coordinatewise.

System (25) is solvable if and only if its right-hand side is orthogonal to the vector —a non-zero solution of the homogeneous adjoint equation Taking this into account, we obtain that in (24)

The above-mentioned non-degeneracy condition consists in satisfying the inequality Using (26) in (24), we obtain a complete picture of the behavior of solutions of (24), and hence of solutions of (21) in a small neighborhood of the zero equilibrium state.

2.2.2. The Critical Case of a Pair of Purely Imaginary Roots

This case arises under the conditions

Let the first of these conditions be satisfied

Then and The linear system (22) in this case has periodic solutions

We fix arbitrarily the value of and set

in (21) and (22). For all sufficiently small , in a sufficiently small neighborhood of the zero equilibrium state of (21), independent of , there exists (see, for example, [33]) a two-dimensional stable locally invariant integral manifold, on which system (21) can be represented up to terms of order in the form of a normal form—complex scalar ordinary differential equation of the first order of the form

To determine the coefficients and , we substitute into (21) the solution in the form of a formal series

where the dependence on t is -periodic. In the resulting formal identity, we collect coefficients at the same powers of At the first step, collecting coefficients at we arrive at a correct equality. At the next step, we obtain a system of equations for determining the function

From here we find that

At the third step, we collect coefficients at As a result, we arrive at a system of equations with respect to the vector function which we will seek in the form

Here and below, denotes the term complex conjugate to the previous one.

The expression for is easily found. We will not need it below, so we will not give it. For , we obtain a system of equations

where

A necessary and sufficient condition for the solvability of this system is that the right-hand side of (28) is orthogonal to the vector h—a non-zero solution of the homogeneous adjoint equation We find that

As a result, for determining , we obtain Equation (27), in which

As an example, we formulate one result.

2.3. The Case of Arbitrary Number N

First of all, let us determine the values of

Recall that for , the zero solution of system (6) is asymptotically stable, and for or , it is unstable. Critical cases in the stability problem for the zero equilibrium state arise for or for In this section, we consider the local dynamics of system (6) in cases close to critical.

Let us give several formulas that will be needed later. Let be the arithmetic root of N-th degree from We set

and let

Note that System (2), (3) can be written in the form

where

Here and below, multiplication of vectors is coordinatewise,

Matrix A has eigenvalues

and corresponding eigenvectors

Note that for the matrix adjoint to A, the corresponding eigenvectors are

Here we assume that and matrix A has a zero eigenvalue, i.e.,

or

We briefly consider only case (30). The eigenvalues have negative real parts. The eigenvalue corresponds to the eigenvector We arbitrarily fix and set in (3)

To find the coefficients and of the normal form, i.e., the scalar equation

we will seek solutions of system (29) in the form of a formal series

Then, for , we obtain a system of equations

For the solvability of this system, it is necessary and sufficient that its right-hand side be orthogonal to the vector From here we come to the conclusion that in Equation (32)

Thus, it is shown that for sufficiently small , the dynamic properties of solutions of (29) with initial conditions from a certain, sufficiently small neighborhood of the zero equilibrium state, independent of , are described by Equation (32) with coefficients (33).

The Critical Case of a Pair of Purely Imaginary Roots

Here we assume that matrix A has a pair of purely imaginary eigenvalues and all its other eigenvalues have negative real parts, i.e., the conditions are satisfied

or

or

We consider only case (34). Then matrix A has eigenvalues where They correspond to eigenvectors and , respectively, and

Let (31) be satisfied for . The normal form describing the dynamic properties of system (29) under conditions (31) and (34) is the scalar complex Equation (27). To find the coefficients of this equation, we consider the formal series

We substitute (35) into (29) and collect coefficients at the same powers of For we obtain a correct equality. At the next step, we find that

Collecting coefficients at we obtain equations for and The expression for is determined simply. We omit it, since it will not needed below. For determining , we arrive at the system

where

For the solvability of system (36), it is necessary and sufficient that vector B be orthogonal to vector —a solution of the homogeneous adjoint equation As a result, for the coefficients of Equation (27), we obtain the equalities

Under the non-degeneracy conditions and , Equation (27) with coefficients (37), (38) completely determines the local dynamics of (29). Using (35), we obtain an asymptotic representation of solutions of (29) through solutions of (27).

2.4. The Case of Sufficiently Large Values of N

The constructions for this case are significantly more complex than the previous ones. Here we assume that the value of N is sufficiently large, i.e., the quantity is sufficiently small

We study the local dynamics of system (29) in this case.

First, let us formulate one simple statement.

Lemma 1.

Let the inequality be satisfied

Then for all sufficiently small ε, all eigenvalues of matrix A in (29) have negative real parts that are separated from zero as If

then for sufficiently small values of ε, there exists an eigenvalue of matrix A whose real part is positive and separated from zero as

In case (39), for small , solutions of (29) with initial conditions from a small neighborhood of the zero equilibrium state, independent of as , tend to zero as In case (40), the zero solution of (29) is unstable, and the problem of dynamics of (29) becomes nonlocal. Therefore, below we assume that

In particular, Under condition (41), matrix A in (29) has no roots with positive real parts separated from zero as , but there is an asymptotically large number of roots whose real parts tend to zero as Thus, in the stability problem for the zero equilibrium state of (29), a critical case of infinite dimension is realized. Below, we separately consider the case when and when

We note the author’s works [9,14,17], in which the dynamic properties of systems in infinite-dimensional critical cases were studied in other cases.

We relabel the elements using a function of two variables where are uniformly distributed points on the segment :

Recall that the boundary value problem (2), (3) for can be written in the form of an equation

with boundary conditions

and for the Equation (42) linearized at zero, we obtain the expression

Equations (42) and (44) cannot be considered for a continuous argument since the expressions and are undefined for An exception is the case when It was considered in [36]. Then, assuming that the functions were considered as periodic in x with period For the roots of the characteristic equation for (44) with , the formula holds

and for the corresponding eigenfunctions , we obtain the expression

Note that under condition (41), infinitely many roots tend to zero as It is important to emphasize that for , the functions depend smoothly on and, which is the same, the regularity condition is satisfied

If then for those integers k for which tend to zero as we obtain that

where depends regularly on

Let us return to the case of arbitrary For the roots of Equation (44), the formula holds

in which the number k takes values

We arbitrarily fix the value of and let either

or

In case (47), we apply in (44) the regularity condition

Then up to , we arrive at the equation

In the irregular case, when condition (48) is satisfied, we obtain that

and

We introduce in (46) The real part of each has the asymptotics

Hence follows a qualitative conclusion on the stability of the equilibrium state: for , the equilibrium is unstable, and for , it is stable.

Note that in case , for Equation (42) with initial conditions from a sufficiently small, independent of , neighborhood of the equilibrium state, solutions tend to zero as and in case , the question of dynamics of (42), (43) is not elementary. Therefore, we consider the critical case when the parameter is chosen so that

We consider two separate cases when the parameter b is close to the parameter a and when it is close to the parameter In the first case, the transition will be with a regular expansion, and in the second case—with an irregular one.

2.4.1. The Case When Parameter b Is Close to Parameter a and Parameter Is Positive

In this section, let us assume that equality (47) holds and

Then, for each number k, the following asymptotic equality holds

and the eigenfunction corresponding to eigenvalue is represented in the form

We use the regularity condition for the boundary value problem (42), (43), i.e., we assume

Let denote the “slow” time and make the substitution Then, dropping terms of order we arrive at the model problem

In (51), in addition to the trivial equilibrium state , there are, generally, solutions

if the following conditions are met: for

Model problem (51) is an approximate problem for boundary value problem (42), (43). This means that if for the function tends to the function which satisfies (42), (43) up to

The question of stability of equilibrium states of model problem (51) (and hence of (42), (43)) with respect to infinitely small perturbations is settled by the linearized problem.

The following lemma is formulated.

Lemma 2.

We consider the critical case when where

and equilibria become degenerate. We introduce the constant and set

For expanding the function , we retain in (42) terms of order As a result, we obtain that

The problem linearized at zero for takes the form

Its characteristic equation

under condition (52) has purely imaginary roots

To eigenvalue , it corresponds the eigenfunction We set and Then,

We construct an approximate particular solution

which will be a solution of (55).

Based on the general method of quasinormal forms [9,14,17], we will seek a solution to problem (54) in the form of a formal series

where and in variable y the function is 1-periodic.

We substitute (57) into (54) and collect coefficients at the same powers of At the first step, collecting coefficients at the first power of we obtain a correct equality. At the next step, we collect coefficients at As a result, we arrive at the equation

where

We formulate an auxiliary lemma.

Lemma 3.

Let function be continuous. Then for solvability of the problem

it is necessary and sufficient that the equality hold

Substituting into (59) expression (58), we arrive at the model problem for the unknown function

The following approximation theorem holds.

Theorem 3.

2.4.2. The Case When Parameter b Is Close to a and Parameter Is Negative

Now let us assume that

We repeat the previous reasoning, i.e., formulas (49)–(50), the transition to the model problem (51) remain valid. Under condition (62), in (51) there is still only one equilibrium solution. We formulate it.

Lemma 4.

We consider the critical case when

Then we use equality (53). For expanding the function , we retain in (42) terms of order This again leads us to the model problem (54). For the linearized model problem (55), we consider the characteristic Equation (56). Here, unlike the previous case, it has purely imaginary roots As in the previous case, Then

We seek the approximate solution to boundary value problem (54) in case (62) in the form

where and the function has the form

We substitute the formal series (64) into (54) and collect coefficients at the same powers of At the first step, collecting coefficients at we obtain a correct equality. At the next step, we collect coefficients at the first power of As a result, we arrive at the model problem for finding

Hence it follows that

where

At the third step, we obtain an equation for finding Without solving it (applying Lemma 3), we obtain the model problem for the unknown function

where

The following theorem is formulated.

Theorem 4.

2.4.3. The Case When Parameter b Is Close to Parameter

Now, for an arbitrarily fixed constant , we use condition (48). We study the linearized boundary value problem (44), (45). From the characteristic Equation (46) under condition (48), infinitely many roots tend to zero as Thus, here the critical case of infinite dimension is realized. To eigenvalue corresponds the eigenfunction which, generally speaking, does not depend regularly on the spatial variable This means that the approximate solutions have an irregular structure.

Note that and for the boundary condition

Then for , we arrive at the equation

Using equality (48), we find that function is regular, i.e.,

We substitute this expression into (42), (43). Then from representation (67), we arrive at the equation

with boundary condition (68). Let For this model problem, we formulate a lemma similar to Lemma 2.

Lemma 5.

We focus on the most interesting critical case when equality (63) holds. In this case, the linearized boundary value problem (69), (68) has purely imaginary, periodic in y, solutions where where if and if

We set

The dynamic picture in the vicinity under conditions (63) and (71) of the equilibrium state of Equations (42) and (43) with respect to infinitely small perturbations is determined by the linearized problem.

We seek in the notation already introduced the formal expansion

where and in variable y all functions from (72) are periodic.

We consider two separate cases. In the first of them, we assume that

and in the second case—the inequality holds

Constructing the critical boundary value problem for condition (73). Let equality (73) hold. We substitute (72) into (42), (43) and collect coefficients at the same powers of As a result, we obtain the equalities

From the boundary conditions, we obtain the equalities

Equations (75) and (79) determine the form of unknown function From (76) and (77), we find that

and from (78) it follows that

The question of determining the coefficient reduces to Equation (77) and boundary condition (80). Applying Lemma 3 to the solvability condition, we obtain the model problem having the form of a complex equation

where

The following approximation theorem, similar to the previous ones, holds.

Theorem 5.

Constructing the critical boundary value problem for condition (74). Let inequality (74) hold. In this case, the calculations are significantly simpler. Preserving the introduced formal series (72), we note that in it the function is represented in the form of a sum of two terms

The first of them is 1-antiperiodic in y, same as function i.e., it expands into a Fourier series containing exponents The second term, , is 1-periodic in i.e., it expands into a series containing only exponents Substituting (72) with decomposition (85) into (42), (43) and collecting the same coefficients. As a result, we obtain equalities (75), (76), (78), (79). Equations (75), (79) determine function and from (76) and (78), functions and are determined by expressions (81), (82). The equation for is obtained by replacing in Equation (77) of by and the equation for has the form

Based on the general boundary condition (80), we obtain two boundary conditions for functions and

From the boundary value problem (86), (88), we find that

For the solvability of the boundary value problem (77) (where is replaced by ), (87), as follows from Lemma 3, it is necessary and sufficient that the following condition

holds, with a 1-antiperiodic boundary condition

The following approximation theorem holds.

Theorem 6.

- Commentary on Section 2

Chains with one-sided or unidirectional couplings between identical equilibrium states N of an autonomous system were considered. The question of local dynamics in the stability problem for equilibrium states is studied. Recall that, for , only the critical case of a simple root occurs, and for only the critical case of a pair of purely imaginary roots or a simple zero root can be realized. In this section, only finite-dimensional critical cases were studied. The situation changes significantly for sufficiently large In Section 2.4, which has no analogues, the critical case, when the parameter N is sufficiently large, is studied, i.e., the parameter is sufficiently small. In this case, as the number N increases, the critical case is transformed into an infinite-dimensional one.

The main defining feature that reflects the type of realizable critical case is the following. The critical case has infinite dimension, i.e., infinitely many roots of the characteristic equation of the linearized problem tend to zero as

By applying the infinite-dimensional normalization method—specifically, the method of quasinormal forms—developed in the author’s works [9,14,17], special nonlinear partial differential equations of parabolic type with boundary conditions have been constructed. These boundary value problems contain no small parameter and their non-local dynamics govern the behavior of all solutions of the original system originating from a sufficiently small neighborhood of the equilibrium state.

The asymptotics of the leading terms in the asymptotic representation of solutions has been constructed.

3. Chains with Two-Sided Couplings

Let us now consider the case when the coupling coefficients of the boundary conditions are both nonzero.

3.1. Critical Cases for Positive Parameter b

Let parameter be fixed. We set

In this case, infinitely many roots of the characteristic Equation (9) tend to zero as i.e., the critical case of infinite dimension is realized. Here, the solution of (15), describing solutions of the linearized problem, possesses regularity condition, i.e., for the regularity condition we have

We substitute (89) and (90) into (12), (13). Then, we introduce new time and then divide by and drop terms of order we arrive at the model problem

For this model problem, a number of approximation theorems hold (see, for example, [9,14,35]). They reduce the analysis of local dynamics of solutions to the boundary value problem (12), (13) to the study of dynamics of solutions to the equilibrium state. The following approximation theorem is formulated.

Theorem 7.

3.1.1. Linear Analysis

To determine stability or instability—about dynamics of solutions to the equilibrium state—of solutions to the boundary value problem (91), (92), one must investigate the linearized boundary value problem

We introduce for it the characteristic equation. For this, we consider the boundary value problem

From the first boundary condition, it follows that the solution is and from the second boundary condition we arrive at the equation

To solve the stability question for the linearized problem (91), (92) and (93), we need to investigate the roots in more detail.

Let us introduce the case when This case is the simplest. Let be determined by the condition that and and

Lemma 6.

In the following two lemmas, we introduce the notation

Lemma 7.

Lemma 8.

Collecting the results of Lemmas 6–8, we introduce a function

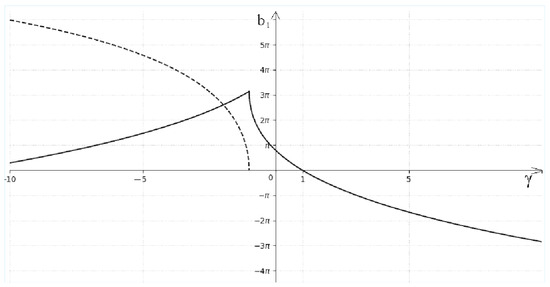

The graph of is shown in Figure 1. For , the zero solution of the boundary value problem (93) is unstable, and for —solution (93) is stable. For in the stability problem for (93), a critical case is realized.

Figure 1.

The graph of function is represented by continuous line, whereas the graph of function is drawn using dashed line for , and for .

3.1.2. Bifurcations in the Critical Case of Zero Root

We focus on the lemma in the critical case of a zero root of the characteristic equation. Let the conditions of Lemma 6 be satisfied, and let the following conditions

hold for certain values and . Let be a small formal positive parameter We set and We seek in the notation introduced the formal expansion

where and are unknown smooth functions. We substitute (96) into (91), (92) and collect coefficients at the same powers of Then, collecting coefficients at we arrive at the equation

with boundary conditions

From (97) and the first boundary condition in (98), we obtain an expression for with undetermined constant c

where Substituting this expression into the second boundary condition (98), we obtain an equation for the unknown function

where In the case when and from (99), one can determine the type of asymptotically stable, independent of parameter , equilibrium states in (91), (92). For this, the following theorem holds.

Theorem 8.

The proof of Theorem 8 is omitted. We note that it essentially uses properties of asymptotic stability and nonresonance of asymptotically stable equilibrium states in parabolic equations (see, for example, [33,34]) Under conditions of Lemma 7, the situation is similar. Let and in (96) replace by Following the same steps, we arrive at Equation (99), where

3.1.3. On Bifurcations in the Case of a Pair of Purely Imaginary Roots

Under conditions of Lemma 8, the situation is similar. Let

As in the case of the Andronov—Hopf bifurcation, we consider the asymptotic expression

where and dependence on —is periodic.

We substitute (100) into (91), (92) and collect coefficients at the same powers of At the first step, we obtain a correct equality, and at the second—we arrive at the equation for finding

Function is sought in the form

Then we continue in a similar way. We collect coefficients at and obtain a boundary value problem for Without solving it (from the solvability condition—Lemma 3), we obtain a scalar complex equation for the unknown complex function of the form

For brevity, the expressions for coefficients, which differ little from those already given above, we omit. We also note that like in form (100) one can construct a formal solution. Note that the formulas for calculating these coefficients are cumbersome, but they are clear. We therefore do not give them.

Remark 1.

Remark 2.

In the case when the nonlinearity of Equation (12) is arbitrary, i.e., when function in (12) is arbitrary, the order of parameter corresponding to the selected decomposition, remains unchanged, but the Equations (99) and (101) depend on other more complex functions of Thus, instead of (99), we obtain

and in the situation of Section 3.1 instead of equation of form (101), we obtain

3.2. Critical Cases for Negative Parameter b

Let us now assume

And in this case, infinitely many roots of the characteristic Equation (9) tend to zero as but unlike the previous case, the eigenfunctions are rapidly oscillating and do not depend regularly on the spatial variable. Therefore, we again encounter irregular expansions. Substituting into (15)

As a result, we obtain that

Function is complex: where are real. Boundary conditions (13) via representation (103) turn into coupled boundary conditions for

Then we use equality (102) and the regularity property of functions Then from Equation (104), we pass to an equation with spatial differentiation

having discarded terms of order Introducing new time , Equation (107) takes the form

Equations (108) and boundary conditions (105), (106) for are identical to the equations considered in the previous section. The following subsections consider issues similar to those examined in Section 3.1. However, when , there are subtleties that we will not dwell on here.

3.2.1. Bifurcations in Case

Let us first focus on the case when The formulas needed for this case are given in Lemma 6. We set

where

We introduce the notation. We set Let and be unknown smooth complex functions that we will determine later. We seek in the notation introduced the formal expansion

We substitute this expansion into the boundary value problem (12), (13) (for the case and collect the corresponding coefficients at the same powers of From boundary conditions (13), we first obtain equalities (105), (106) with boundary conditions

Let us write the solution of Equation (114) for By substituting it into boundary conditions for , we find by simple calculation that the solution satisfies boundary conditions for i.e., Then we obtain that

Now let us study the solvability of Equation (113) for Using equalities (109), (110)–(112) and (114)–(116), we obtain that for the boundary conditions have the form

Function satisfying (113), complemented by (117), takes the form

Then, substituting into condition (118), we obtain the equation

From here, we arrive at the scalar real equation for

where

Before formulating an approximation theorem, let us introduce a definition.

Proposition 2.

Now let us formulate a theorem that follows from the preceding constructions.

Theorem 9.

Note that Equation (119) can have either one equilibrium state (), or none, or two equilibrium states. According to the statement of Theorem 9, we conclude that in each of these cases the family has an asymptotically invariant equilibrium state depending on the arbitrary parameter of asymptotically invariant equilibrium states.

Here is one remark. Instead of considering the constants values of , one can consider time-dependent, for example, periodic, function

It is important to emphasize the essential dependence of asymptotic expansions on the number N of chain elements. This is because in boundary condition (106) the factor appears. If for even (odd) N the critical case is realized, then for odd (even) N this does not happen, i.e., either under condition of closeness to zero of solutions tend to zero as or the zero solution becomes unstable and the problem of dynamics becomes nonlocal. A similar strong dependence on N was observed in Section 2.

For condition , the situation is similar. It is described by the formulas of Lemma 3. Functions and are represented in this case as and respectively.

3.2.2. Bifurcations in the Case

Let

and the conditions of the following lemma from Lemma 8 hold:

Then the linearized equation

has solutions and, respectively, complex conjugate to them. Then the solution of Equation (104) under condition (102) will up to be represented in the form

where and are independent complex constants. From the first boundary condition (105) and (106), we obtain the equalities

Eliminating the indices, replacing indices 1 and 2 in the notation by primes, we obtain that representation (122) can be written in the form

Here it is assumed that the unknown complex functions and depend on “slow” time

We seek approximate solutions of the boundary value problem (12), (13) in the form of a formal asymptotic expansion

Here the value contains the “first” harmonics, just like , i.e.

The function contains a set of “zero” and “second” harmonics

and contains a set of “third” harmonics.

In order for expansion (123) up to to satisfy the boundary value problem (12), (13), it is necessary that functions and be solutions of a certain boundary value problem. We will not dwell on the details of the derivation of Equations (123) in (12), (13) and we collect the corresponding coefficients at the same powers of and at the same exponents. At the first step, we collect coefficients at As a result, we arrive at the equalities

The following notations are used here

At the next step, collecting coefficients at we obtain a boundary value problem for and It should be noted that the corresponding equation for is uniquely solvable and its solution is determined in closed form. We will not need it below, so we will not give it.

Let us write the boundary value problem for First, we introduce the notation:

and also Then we arrive at a boundary value problem for the normalizing functions and (see Formula (124)):

where

Solutions of system (126) for the normalizing functions satisfying boundary conditions at the origin have the form

and the first boundary condition for is satisfied. The boundary condition for takes the form i.e.,

Using notation (125), for the equation obtained, we have

where

Now we formulate a theorem.

Theorem 10.

From the statement of the theorem, it follows, in particular, that in the case of choosing a constant function , equality (127) for solvability determines equilibrium states with a continuum of boundary conditions. In the case when function is periodic, in (128) there can arise bounded and unbounded solutions.

Here is one important remark. Functions for do not in general satisfy the boundary condition for But their values for do not appear in the formula of Equation (128). Therefore, functions are corrected using the formula

which, firstly, satisfies the boundary value problem up to and, secondly, does not change the values of the coefficients participating in Equation (128).

4. Conclusions

A number of problems related to the dynamical properties of equilibrium states of an autonomous boundary value problem for ordinary differential equations were studied. The main object of study was chains consisting of N elements. Questions of local dynamics in the stability problem for equilibrium states were studied. Recall that critical case of infinite dimension arises in the case when the characteristic equation of the linearized problem has infinitely many roots tending to zero as the corresponding small parameter of the boundary value problem.

The main attention was paid to the case when parameter corresponding to the connection coefficient between chain elements, is both positive and negative. In each of these cases, we considered stability questions depending on the boundary parameter For positive b and for the cases when and , the critical cases realized are with simple equilibrium states, and for —a case with an oscillatory regime. Corresponding approximation theorems for asymptotics were formulated. For example, it was shown that for , the question of dynamics is locally determined by parabolic equations with corresponding boundary conditions.

For negative values of b, the situation is significantly more complex. The eigenfunctions, generally speaking, do not depend regularly on the spatial variable. In the case , local dynamics from a sufficiently small neighborhood of the zero equilibrium state can be determined by a boundary value problem with Neumann boundary conditions. For , dynamics is described by a system of complex equations. The system of reduced boundary value problems contains two functions that freely determine the initial data for the system and boundary conditions.

The proofs of formulated theorems are omitted. All of them are based on the method of quasinormal forms with applications of contraction-type theorems.

It is important to emphasize that for in the boundary conditions for equations appearing, when eigenfunctions contain oscillating values with respect to 1 multipliers of spatial argument, from the corresponding asymptotic formulas, one can construct fast-oscillating solutions.

Funding

This work was carried out within the framework of a development programme for the Regional Scientific and Educational Mathematical Center of the Yaroslavl State University with financial support from the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (Agreement on provision of subsidy from the federal budget No. 075-02-2025-1636).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created and analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Kuznetsov, A.P.; Kuznetsov, S.P.; Sataev, I.R.; Turukina, L.V. About Landau—Hopf scenario in a system of coupled self-oscillators. Phys. Lett. A. 2013, 377, 3291–3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osipov, G.V.; Pikovsky, A.S.; Rosenblum, M.G.; Kurths, J. Phase synchronization effects in a lattice of nonidentical Rossler oscillators. Phys. Rev. E 1997, 55, 2353–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikovsky, A.S.; Rosenblum, M.G.; Kurths, J. Synchronization: A Universal Concept in Nonlinear Sciences; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001; ISBN 0-521-59285-2. [Google Scholar]

- Dodla, R.; Se, A.; Johnston, G.L. Phase-locked patterns and amplitude death in a ring of delay-coupled limit cycle oscillators. Phys. Rev. E 2004, 69, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, C.R.S.; Sorrentino, F.; Murphy, T.E.; Roy, R. Synchronization states and multistability in a ring of periodic oscillators: Experimentally variable coupling delays. Chaos Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 2013, 23, 43117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, R.; Lin, Z.; Ai, X.; Wu, J. Synchronization of Epidemic Systems with Neumann Boundary Value under Delayed Impulse. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Sande, G.; Soriano, M.C.; Fischer, I.; Mirasso, C.R. Dynamics, correlation scaling, and synchronization behavior in rings of delay-coupled oscillators. Phys. Rev. E 2008, 77, 55202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinshov, V.V.; Nekorkin, V.I. Synchronization of delay-coupled oscillator networks. Physics–Uspekhi 2013, 56, 1217–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinshov, V.V. Collective dynamics of networks of active units with pulse coupling: Review. Izvestiya VUZ Appl. Nonlinear Dyn. 2020, 28, 465–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, G.; Ludwig, M.; Qian, J.; Kubala, B.; Marquardt, F. Collective dynamics in optomechanical arrays. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 107, 043603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wiederhecker, G.S.; Manipatruni, S.; Barnard, A.; McEuen, P.; Lipson, M. Synchronization of micromechanical oscillators using light. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 109, 233906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.E.; Sadeghpour, H.R. Quantum synchronization of quantum van der Pol oscillators with trapped ions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 111, 234101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanchuk, S.; Wolfrum, M. Instabilities of stationary states in lasers with long-delay optical feedback. SIAM Appl. Dyn. Syst. 2010, 9, 519–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashchenko, S.A. Quasinormal Forms for Chains of Coupled Logistic Equations with Delay. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashchenko, S.A. Dynamics of a Chain of Logistic Equations with Delay and Antidiffusive Coupling. Dokl. Math. 2022, 105, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.M.T.; Stewart, H.B. Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002; 464p. [Google Scholar]

- Kashchenko, S.A. Dynamics of advectively coupled Van der Pol equations chain. Chaos Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 2021, 31, 033147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter, I.; Zigzag, M.; Englert, A.; Geissler, F.; Kinzel, W. Synchronization of unidirectional time delay chaotic networks and the greatest common divisor. Europhys. Lett. 2011, 93, 60003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosin, D.P.; Rontani, D.; Gauthier, D.J.; Schöll, E. Control of synchronization patterns in neural-like Boolean networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. Am. Phys. Soc. 2013, 110, 104102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanchuk, S.; Perlikowski, P.; Popovych, O.V.; Tass, P.A. Variability of spatiotemporal patterns in non-homogeneous rings of spiking neurons. Chaos Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 2011, 21, 47511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinshov, V.; Nekorkin, V. Synchronization in networks of pulse oscillators with time-delay coupling. Cybern. Phys. 2012, 1, 106–112. [Google Scholar]

- Stankovski, T.; Pereira, T.; McClintock, P.V.E.; Stefanovska, A. Coupling functions: Universal insights into dynamical interaction mechanisms. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2017, 89, 045001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinshov, V.; Shchapin, D.; Yanchuk, S.; Wolfrum, M.; D’Huys, O.; Nekorkin, V. Embedding the dynamics of a single delay system into a feed-forward ring. Phys. Rev. E 2017, 96, 042217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karavaev, A.S.; Ishbulatov, Y.M.; Kiselev, A.R.; Ponomarenko, V.I.; Gridnev, V.I.; Bezruchko, B.P.; Prokhorov, M.D.; Shvartz, V.A.; Mironov, S.A. A model of human cardiovascular system containing a loop for the autonomic control of mean blood pressure. Hum. Physiol. 2017, 43, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, M.; Ronen, E.; Friesem, A.A.; Davidson, N. Observing Geometric Frustration with Thousands of Coupled Lasers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 110, 184102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pando, A.; Gadasi, S.; Bernstein, E.; Stroev, N.; Friesem, A.; Davidson, N. Synchronization in Coupled Laser Arrays with Correlated and Uncorrelated Disorder. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 133, 113803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nixon, M.; Fridman, M.; Ronen, E.; Friesem, A.A.; Davidson, N.; Kanter, I. Controlling Synchronization in Large Laser Networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 214101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emelianova, A.A.; Maslennikov, O.V.; Nekorkin, V.I. Disordered quenching in arrays of coupled Bautin oscillators. Chaos 2022, 32, 063126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emelianova, A.A.; Kasatkin, D.V.; Nekorkin, V.I. Nonlinear phenomena in Kuramoto oscillatory networks with dynamic connections. Izv. Vyss. Uchebnykh Zaved. Prikl. Nelineynaya Din. 2021, 29, 635–675. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shena, J.; Kominis, Y.; Bountis, T.; Kovanis, V. Spatial control of localized oscillations in arrays of coupled laser dimmers. Phys. Rev. E 2020, 102, 012201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabbeik, M.; Jafari, S.; Meucci, R.; Perc, M. Synchronization and multistability in a network of diffusively coupled laser models. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simulat. 2023, 125, 107380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fermi, E.; Pasta, J.; Ulam, S. Studies of Nonlinear Problems; Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory: Los Alamos, NM, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman, P. Ordinary Differential Equations; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Dan, H. Geometric Theory of Semilinear Parabolic Equations; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1981; 352p. [Google Scholar]

- Kaschenko, S.A. Normalization in the systems with small diffusion. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos Appl. Sci. Eng. 1996, 6, 1093–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashchenko, S.A. Dynamics of Chains of Many Oscillators with Unidirectional and Bidirectional Delay Coupling. Comput. Math. Math. Phys. 2023, 63, 1817–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).