Abstract

New AI technologies have empowered e-commerce personalized recommendation systems, many of which now leverage time-series forecasting to capture dynamic user preferences. However, buyers’ algorithm aversion hinders these systems from realizing their full potential in enabling data-driven decisions. Current research focuses heavily on artifact design and algorithm optimization to reduce aversion, with insufficient attention to the temporal dimensions of human–AI interaction (HAII). To address this gap, this study explores how recommendation accuracy, novelty, and diversity—key attributes in time-series recommendation contexts—influence buyers’ algorithm aversion from a temporal HAII perspective. Data from 205 online survey responses were analyzed using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Results reveal that accuracy (encompassing sequential prediction consistency), novelty (balanced with temporal relevance), and diversity (covering long-term preferences) negatively impact algorithm aversion, with perceived usefulness as a mediator. Reduced aversion further facilitates data-driven purchasing decisions. This study enriches the algorithm aversion literature by emphasizing temporal HAII in time-series recommendation scenarios, bridging human factors research with data-driven decision-making in e-commerce.

Keywords:

time-series recommendation; temporal human–AI interaction; algorithm aversion; data-driven decision-making; perceived usefulness MSC:

91C99

1. Introduction

The advent of AI has catalyzed a paradigm shift in personalized recommendation systems, with many e-commerce platforms now integrating time-series forecasting techniques to capture dynamic user preferences—from short-term interest fluctuations to long-term seasonal patterns (e.g., holiday shopping habits). These time-series recommendation systems leverage sequential behavioral data to predict future needs, aiming to bridge temporal gaps between user intent and algorithmic output [1]. By combining LLM-powered semantic processing with long-sequence preference modeling, they strive to deliver recommendations that are not only personalized but also temporally coherent, enhancing the potential for data-driven decision-making in online shopping. Such systems have become ubiquitous across platforms like Amazon and TaoBao, where timely and contextually relevant suggestions directly influence purchase outcomes.

Time-series recommendation systems reduce information search costs by aligning recommendations with evolving user preferences over time, theoretically boosting decision confidence and purchase conversions [2]. However, this promise is undermined by a critical paradox: while users depend on these systems to navigate dynamic markets, they often exhibit algorithm aversion—a psychological resistance to relying on algorithmic recommendations [3]. This aversion is particularly pronounced in time-series contexts, where users may struggle to interpret the algorithm’s handling of temporal dynamics (e.g., sudden shifts in recommendations due to detected long-term trend changes) or inconsistencies in sequential suggestions (e.g., conflicting short-term and long-term preferences). In such scenarios, human–AI interaction (HAII) transcends mere utility to involve judgments of the algorithm’s ability to “understand” temporal patterns, making temporal HAII a key determinant of aversion.

Prior studies on algorithmic recommendations have identified algorithm attributes like predictability [4] and error patterns [5], as well as fairness, explainability, and transparency [6], as key drivers of algorithm aversion. While these studies acknowledge human perceptions [7], they overlook the unique dynamics of time-series recommendation quality—such as how (1) “accuracy” demands sequential consistency (e.g., a system that recommends winter coats in October and follows up with scarf suggestions in November, aligning with a user’s evolving seasonal needs), (2) “diversity” requires balancing short- and long-term coverage (e.g., a user who frequently buys running shoes also receives occasional recommendations for hiking gear over months, avoiding over-narrowing their choices), and (3) “novelty” depends on temporal relevance (e.g., seasonally appropriate suggestions like gifting guides in December or sunscreen in April, rather than random unexpected items). While temporal decision logic (e.g., “why this recommendation now?”) boosts confidence [6], opaque handling of non-stationary preferences may exacerbate resistance [8].

These temporal dimensions of recommendation quality shape user experiences during temporal HAIIs, yet their influence on algorithm aversion remains underexplored. Additionally, while privacy beliefs may moderate user responses [9], the core question—how time-series recommendation quality affects algorithm aversion through temporal HAII—lacks empirical attention.

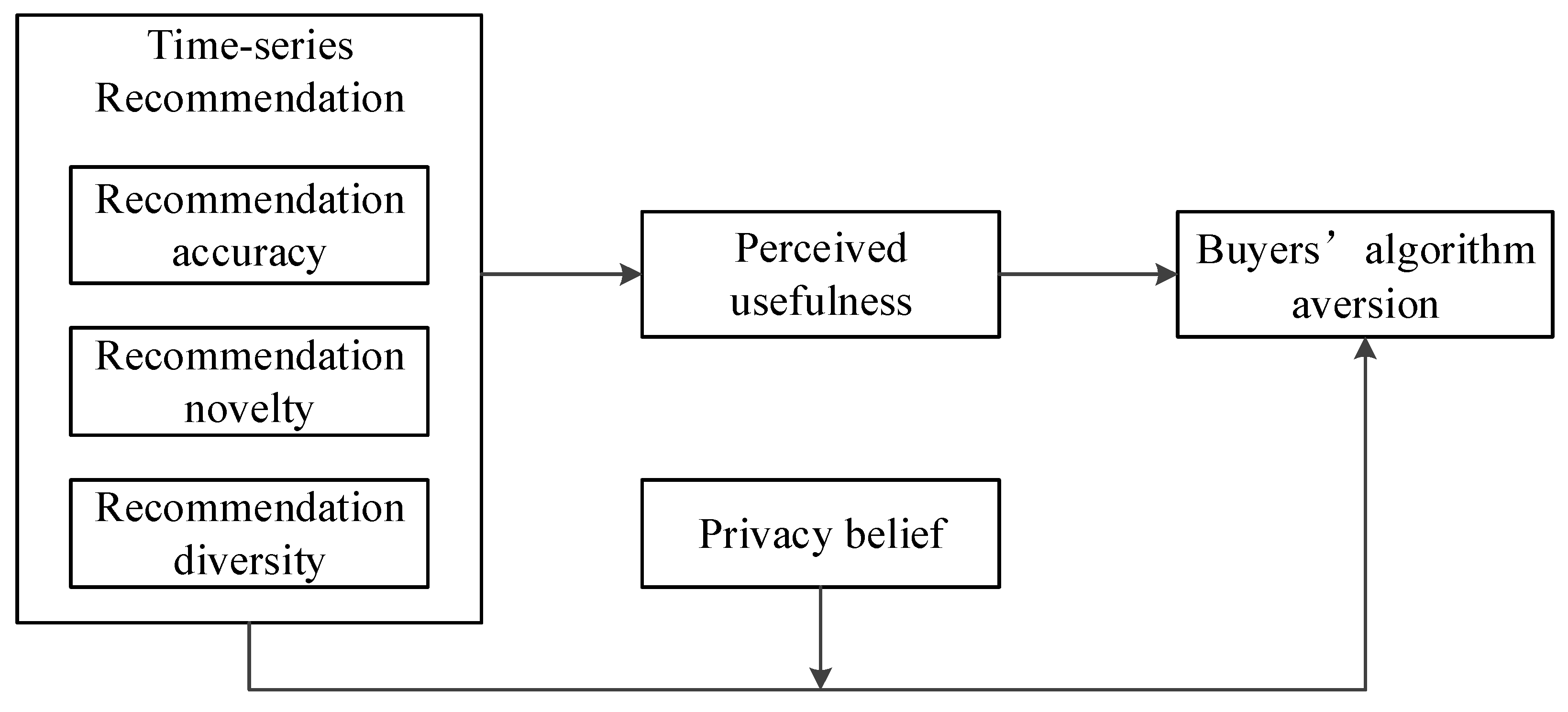

Drawing from the augmented Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), which emphasizes usefulness and contextual beliefs [10], this study investigates how three dimensions of time-series recommendation quality—accuracy (sequential consistency), novelty (temporal relevance), and diversity (long-term coverage)—influence algorithm aversion via perceived usefulness, with privacy beliefs as a potential moderator. Buyers’ algorithm aversion, which is the opposite of technology adoption, can be explained using widely used theories of technology adoption, including the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), and the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). TAM suggests that whether platform users trust and continue to adopt a recommendation system depends on the perceived usefulness of the system, which in turn is influenced by various factors [11]. By focusing on temporal HAII, we aim to unpack how users’ ongoing interactions with time-series recommendations shape their resistance to algorithmic guidance, and ultimately, their willingness to make data-driven decisions.

To test these hypotheses, we conducted an online survey via www.wjx.cn (a platform comparable to Amazon Mechanical Turk) from May to June 2024, collecting 205 valid responses. Data were analyzed using the method of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Results indicate that accuracy, novelty, and diversity negatively affect algorithm aversion, with perceived usefulness as a mediator; privacy beliefs did not moderate these relationships. Reduced algorithm aversion, in turn, facilitates data-driven purchasing decisions.

This study makes two theoretical contributions. First, it enriches research on time-series recommendation systems by examining negative user responses, shifting focus from adoption drivers (e.g., trust and acceptance) to barriers like algorithm aversion. By grounding the analysis in TAM, we clarify how temporal quality dimensions (novelty with temporal relevance, accuracy with sequential consistency, and diversity with long-term coverage) shape aversion through perceived usefulness. Second, it advances algorithm aversion research by emphasizing temporal human–AI interaction, shifting focus from algorithm attributes to interactive processes. It explores how the temporal quality dimension of recommendation influences algorithm aversion via perceived usefulness, addressing the need for research on human–AI interaction in long-sequence analysis.

Managerially, these findings help e-commerce platforms prioritize time-series recommendation features—such as sequential accuracy and temporally balanced diversity—that most effectively reduce aversion, thereby enhancing user reliance on data-driven suggestions. For researchers, this study underscores the need to integrate temporal dynamics into human–AI interaction frameworks, particularly in the context of long-sequence recommendation systems.

2. Related Literature

In e-commerce or social media platforms, recommendation algorithms and systems are widely adopted to predict potential and dynamic user preferences across historical data, which exerts positive effects. Previous research has largely focused on how to enhance the positive usage of recommendation systems [12], such as trust building [11], algorithm acceptance [13,14], algorithm usage [15], recommendation preference [16], and recommended service adoption [17]. Among these studies, most studies acknowledge that the quality of recommendation information (simply called recommendation quality in the following text) significantly shapes positive consumer psychology (e.g., satisfaction and trust) and behaviors (e.g., adoption willingness and purchase decisions) [18,19,20].

For the positive relationship between recommendation quality and user adoption/usage, scholars have further identified multiple dimensions for assessing recommendation quality, including novelty, accuracy, and diversity. Kaminskas and Bridge [21] noted that accuracy receives lower priority in product recommendations, proposing a framework emphasizing novelty, diversity, and serendipity. Chen et al. [22] similarly highlighted timeliness (a key temporal attribute), novelty, and relevance as drivers of e-commerce satisfaction. Nilashi et al. [11] consolidated core quality determinants into a triad: (1) congruence between user preferences and recommendation outputs, (2) diversity of suggested items, and (3) interpretability of recommendation rationales. Xiao and Benbasat [23] further emphasized adaptive personalization fidelity, which is relevant for optimizing interfaces in temporal human–AI interaction.

Most recently, besides focusing on user adoption/usage, recent scholars have turned to the phenomenon of user resistance, trying to explore hindrances to system application [24]. Especially in the era of AI, user resistance is further displayed as algorithm aversion, with evolving conceptualizations. Dietvorst et al. [3] defined it as the preference for human judgment over superior algorithmic predictions, framing the human–algorithm accuracy paradox. However, this narrow view struggles to capture challenges in time-series contexts, such as distrust stemming from inconsistent long-horizon recommendations. Addressing this, Luo et al. [25] reformulated the concept to encompass generalized aversion toward algorithmic entities, including negative affect and avoidance behaviors—critical for understanding resistance to sequence-aware recommendation systems. As a form of negative usage, algorithm aversion significantly constrains the effectiveness of recommendation systems. Thus, how to reduce algorithm aversion is a critical topic.

Existing research identifies three key influential factors on algorithm aversion: algorithm attributes, task types, and individual differences, with unique implications for temporal human–AI interaction.

First, algorithm attributes like predictability and error patterns shape aversion in time-series scenarios. For example, sequential inconsistency in recommendations (a hallmark of long-sequence forecasting challenges) undermines trust more than isolated errors [26]. Fairness, explainability, and transparency—especially around temporal decision logic (e.g., “why this recommendation now?”)—boost user confidence [6], while opaque handling of non-stationary preferences exacerbates aversion [8]. Chen and Zheng [4] highlight that users demand interpretability of sequential reasoning, not just individual recommendations.

Secondly, in terms of task types, algorithm credibility diminishes in subjective tasks requiring emotional intelligence compared to objective, quantifiable activities [27]—aligning with the machine stereotype paradigm, which posits perceived computational superiority paired with affective deficits [28]. This credibility gap extends to creative domains (high vs. low creativity recommendations) and symbolic consumption contexts, particularly in time-series scenarios where temporal nuance amplifies perceived subjectivity [29].

Lastly, individual differences constitute a critical moderating dimension in algorithm aversion dynamics. Self-relevance and domain-specific expertise moderate aversion through dual cognitive pathways: (1) comparative judgment contexts where buyers evaluate algorithmic outputs against personal expertise, and (2) expertise-driven overconfidence extrapolating beyond one’s competency boundaries [30]. This paradoxical mechanism—where specialized knowledge enhances domain confidence while distorting metacognitive calibration—aligns with the Dunning-Kruger effect in temporal HAII. Additionally, factors like familiarity with, experience of, control over, and identity strength associated with algorithms further influence aversion, especially in long-sequence recommendation contexts [31,32].

In conclusion, we can see that the research about recommendation systems and user behaviors can be divided into two streams: user acceptance and user resistance (i.e., algorithm aversion). For user acceptance, recommendation quality is an important influential factor. For user resistance, algorithm attributes, task types, and individual differences are identified as three key influential factors. Here is the research gap: while recommendation quality is acknowledged to promote user acceptance, it is not clear whether it exerts the same influence in decreasing user algorithm aversion, nor is it clear what the underlying mechanism is. For this reason, this study tries to investigate how recommendation quality influences algorithm aversion in a time-series recommendation context.

3. Research Model and Hypotheses

3.1. Research Constructs

3.1.1. Time-Series Recommendation Quality: Accuracy, Novelty, and Diversity

Product recommendations on e-commerce platforms, as reference suggestions generated by recommendation systems based on buyers’ information needs and behavioral data, serve as a medium for personalized online information services [33]. In long-term usage, buyers’ trust and continued reliance on recommendation systems—especially time-series ones that process sequential behavioral data—depend heavily on the usefulness and quality of recommendation information [11].

Building upon Herlocker et al. [34]’s foundational work, recommendation accuracy is operationalized as the system’s capacity to align suggested items with latent user preference vectors (which may evolve over time) through predictive modeling. In time-series contexts, this includes maintaining consistency across sequential recommendations to reflect stable or gradually changing preferences. Enhanced accuracy helps users distinguish relevant from irrelevant items across different time windows.

Novelty in recommendation systems encompasses absolute and relative dimensions. According to Vargas and Castells [35] and Ge et al. [36], it is quantified through (1) absolute novelty (inverse correlation with item popularity indices); (2) relative surprise (cosine dissimilarity from historically preferred items, with temporal boundaries such as recent vs. long-past preferences); and (3) serendipitous value (when unexpected recommendations align with emerging or seasonal needs).

Diversity, defined as the degree of dissimilarity among recommended items and measured via pairwise metrics [37,38], gains additional nuance in time-series scenarios. It involves balancing short-term variety (within a single recommendation list) with long-term coverage of diverse preferences (across sequential recommendations), helping platforms avoid filter bubbles and ensure comprehensive inventory representation [11,39].

3.1.2. Perceived Usefulness

Rooted in the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) examines technology adoption through two individual cognitive antecedents, rather than system technical features [40]. In other words, TAM does not consider the technical details of a system, but focuses on users’ overall perceptions of this system, which includes perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. For this generality, TAM has been used to explain adoption of various technologies, even dynamic and real-time systems [41]. In this model, perceived usefulness is a belief that a system enhances task effectiveness and productivity, while perceived ease of use is the expected effort and time reduction in interactions [42].

In e-commerce, Vijayasarathy [10] expands perceived usefulness to consumers’ anticipated value from digital marketplace affordances: informational utility, comparative efficiency, and procedural acceleration. For time-series recommendation systems specifically, we operationalize it through three efficacy dimensions: (1) relevance Optimization: precision matching to dynamic, time-varying preference structures; (2) decision scaffolding: cognitive load reduction via sequential predictive analytics; and (3) temporal economy: minimizing opportunity costs in product discovery across extended time horizons.

3.1.3. Privacy Belief

Within time-series recommendation systems—particularly those that rely on cumulative behavioral data (browsing patterns and purchase histories over time)—privacy beliefs represent buyers’ risk–benefit assessments of personal data disclosure. It shapes willingness to share the sequential behavioral footprints essential for generating time-aware recommendations [43]. Formed through evaluating online information-sharing risks and benefits [10], this belief is pivotal for user acceptance of, and engagement with, recommendation systems that process long-term behavioral sequences.

3.2. Research Hypotheses

This study explores how multidimensional recommendation quality—operationalized as accuracy, novelty, and diversity—influences buyers’ algorithm aversion through perceived usefulness, and how this relationship is moderated by privacy beliefs. Figure 1 presents the conceptual model. The quality of recommendation information is a key factor shaping buyers’ attitudes, intentions, and behavioral responses toward time-series recommendation systems. The synergy between high-quality information and effective sequential prediction algorithms is essential to reduce buyers’ algorithm aversion in e-commerce platforms [44].

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

3.2.1. Time-Series Recommendation Quality and Buyers’ Algorithm Aversion

Algorithmic determinants—including decision architecture, interface design, and output characteristics—are critical predictors of algorithm aversion [45]. In time-series recommendation systems, decision accuracy (here, recommendation accuracy) reflects not only the veracity of single recommendations but also the consistency of sequential outputs, serving as a foundational driver of user adherence. Empirical evidence shows asymmetrical error tolerance: inaccuracies in algorithmic decisions (especially inconsistent errors across sequential recommendations) incur harsher penalties than equivalent human errors, eroding confidence disproportionately in tasks relying on long-term prediction [3,46]. Such failures undermine trust, leading users to doubt the system’s ability to handle dynamic preference changes over time [47].

High accuracy in time-series recommendations helps users distinguish relevant items across different time windows, but sole focus on accuracy is insufficient [48]. User valuation in long-term interaction extends to serendipitous discovery [35,36]—particularly novelty aligned with temporal contexts (e.g., seasonal needs), making novelty an additional factor in algorithm aversion. Moreover, overly similar sequential recommendations diminish value: uniform suggestions may fail to support long-term exploration of options or feel monotonous, highlighting diversity (balancing short-term variety and long-term coverage) as another critical factor.

This study posits that the tripartite quality framework of time-series recommendations—accuracy (sequential consistency), novelty (temporal relevance), and diversity (long-term coverage)—reduces algorithm aversion. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1.

Recommendation accuracy (H1a), recommendation novelty (H1b), and recommendation diversity (H1c) have a negative impact on buyers’ algorithm aversion.

3.2.2. The Mediation of Perceived Usefulness

Perceived usefulness, a cornerstone of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), is critical for understanding users’ perceptions of time-series recommendation systems. Lin and Lu [49] identified information system quality variables (e.g., information quality and response time) as exogenous TAM variables, showing their impact on perceived usefulness. This study argues that time-series recommendation quality (accuracy, novelty, and diversity) directly shapes perceived usefulness.

Firstly, accuracy ensures that the system precisely matches buyers’ dynamic needs and preferences over time, helping them quickly locate products of interest amid vast amounts of merchandise. Previous studies have found that high recommendation accuracy reduces consumers’ search costs, thereby enhancing the convenience of their shopping experience [50]—a key driver of perceived usefulness in sequential interactions.

Second, recommendation novelty—encompassing popularity differentials and serendipitous discovery—aligns with buyers’ exploratory motivations in time-series contexts. E-commerce buyers inherently seek novel consumption experiences, with unexpected yet relevant recommendations satisfying exploratory motivations. Scholarly consensus identifies novelty thresholds as critical enhancers of perceived recommendation quality [37,38,51].

Lastly, diversity avoids the monotony of overly similar recommendations, ensuring coverage of long-term preference breadth. Highly similar recommendations may fail to illustrate available options or be perceived as biased, whereas diverse recommendations enhance perceived usefulness by facilitating comprehensive product exploration [37,38,52].

Regarding the link between perceived usefulness and algorithm aversion, TAM’s foundational premise suggests perceived usefulness mediates resistance to technology. Since algorithm aversion reflects resistance to time-series recommendation systems, it is likely mitigated when users perceive systems as useful. This aligns with frameworks where perceived usefulness mediates the relationship between system attributes and adoption behaviors. For example, Tao et al. [53] perceived usefulness as a mediator between online reviews and new product diffusion.

This study contends that the three dimensions of recommendation quality in time-series systems—accuracy, novelty, and diversity—elevate perceived usefulness, thereby reducing algorithm aversion. Thus, we propose the following:

H2.

Perceived usefulness mediates the relationship between recommendation accuracy (H2a), recommendation novelty (H2b), or recommendation diversity (H2c) and buyers’ algorithm aversion.

3.2.3. The Moderating Effect of Privacy Beliefs

This study hypothesizes that privacy beliefs moderate the relationship between time-series recommendation quality and algorithm aversion. Previous research delineates a trust formation mechanism whereby recommendation quality reduces algorithm aversion: accurate prediction of dynamic preferences enhances personalization efficacy and user satisfaction—key drivers of trust in time-series recommendation systems [18,54,55]. This trust, once established, promotes long-term confidence in sequential recommendations [11]. Conversely, perceptions of inappropriate or biased sequential recommendations may trigger distrust, degrading platform performance [56]. Beyond accuracy, novelty (timely introduction of new items) and diversity (long-term preference coverage) also foster trust in such systems [11].

However, the efficacy of this trust formation pathway is contingent on buyers’ privacy beliefs [57]—particularly in time-series systems that rely on cumulative behavioral data (e.g., long-term browsing histories, seasonal purchase patterns, etc.) to refine recommendations. Buyers with strong privacy beliefs are more confident that their sequential data will be securely handled and appropriately used to inform time-aware recommendations. Given the inherent risks of sharing long-term behavioral footprints, these buyers are more willing to tolerate vulnerability in exchange for personalized recommendations, reflecting higher baseline trust compared to those with weaker privacy beliefs.

Thus, strong privacy beliefs amplify the extent to which time-series recommendation quality (accuracy, novelty, and diversity) mitigates algorithm aversion: when users trust that their long-term data is protected, they are more likely to attribute high-quality sequential recommendations to the system’s effectiveness (rather than dismiss them due to privacy concerns). We therefore propose the following:

H3.

Privacy beliefs strengthen the negative influence of the recommendation accuracy (H3a), recommendation novelty (H3b), or recommendation diversity (H3c) of time-series recommendation information on buyers’ algorithm aversion.

4. Methodology

4.1. Data Collection

This study focuses on Chinese e-commerce platforms, examining how time-series recommendation quality within these platforms influences buyers’ algorithm aversion. The target respondents were users with experience interacting with sequential recommendation systems on such platforms. Data were collected via an online survey using www.wjx.cn (a platform with functions comparable to Amazon Mechanical Turk). In other words, we designed and published an online questionnaire on the platform www.wjx.cn. Then, a link for the questionnaire was generated on this platform and distributed through other social media channels, including WeChat, QQ, and Weibo. Participants volunteered to answer the questionnaire. In order to reduce potential common method bias, we adopted separation techniques, specifically, temporal separation, to collect data at different points in time [58]. This technique can help to erase measurement-related clues and to improve the accuracy of responses [59]. In detail, the data collection period spanned from 1 May 2024 to 30 May 2024, which helped to capture variations in user experiences with recommendations across different temporal points.

After deleting incomplete and invalid responses with the same score for all options, 205 valid responses were collected in the end. In the structural equation model, the ratio of the sample size to the number of observed variables should have been controlled in the range of 10:1 (10 observations per one estimated parameter) or even 20:1. A total of 205 valid responses were obtained in this survey, which met the requirements [60].

Table 1 presents a descriptive statistical analysis of the survey participants. Regarding gender distribution, the survey respondents were 54.63% male and 45.37% female, showing a slightly higher number of male users in the sample. Age analysis revealed that users aged 18 to 30 years constituted the largest group (31.22%), followed by those aged 31 to 43 (24.39%) and 44 to 56 years (15.61%). In terms of education, individuals with a bachelor’s degree were the largest group (45.37%), followed by those with a high school education or lower (34.15%). Regarding monthly income, users with incomes between 6000 and 8000 RMB made up the highest proportion (29.76%).

Table 1.

Sample descriptions.

Among the most commonly used e-commerce platforms, Taobao.com led (42.44%), followed by JD.com (26.34%) and Pinduoduo.com (22.44%). Most users engaged in online shopping either occasionally (71.71%) or frequently (25.85%), with 43.9% spending less than 500 RMB monthly and 9.27% spending over 1500 RMB. These patterns reflect the shopping habits and consumer spending power of the participants.

4.2. Questionnaire

The questionnaire comprised 24 items related to the 6 constructs of our research model. The question items are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Questionnaire items.

The time-series recommendation information studied in this study refers to the highly matched product information launched by time-series recommendation systems on e-commerce platforms, which combine user personal attributes and past browsing habits. Additionally, three dimensions for the quality of time-series recommendation information were considered, including novelty, accuracy, and diversity. For the scale settings, previous scales from various researchers were referred to, with the measurement of accuracy based on scales by Knijnenburg et al. [61] and Bollen et al. [62]; the measurement of diversity based on a scale by Nilashi et al. [11]; and the measurement of novelty based on scales by Lin et al. [63] and Moon and Kim [64]. Moreover, perceived usefulness was measured using a scale by Lin and Lu [49], privacy beliefs were measured using a scale by Vijayasarathy [10] and Rosenthal et al. [65], and buyers’ algorithm aversion was measured using a scale by Xie et al. [66].

The participants had to express their opinions using five-point Likert scales (Strongly Agree = 5, Agree = 4, Neither Agree nor Disagree = 3, Disagree = 2, and Strongly Disagree = 1).

4.3. Methods

To analyze the questionnaire data collected in this study, we employed SPSS 26.0 and SmartPLS 3.0 software, with the partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) method as the core analytical tool.

Distinct from covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM), PLS-SEM adopts a predictive rather than confirmatory analytical framework [67]. And, compared to other SEM techniques, PLS-SEM imposes fewer strict requirements on sample size [68]. Additionally, PLS-SEM is well-suited for validating models that involve mediating effects, making it an appropriate choice for the analytical needs of this study [69].

Given our study’s focus on identifying variables with significant impacts on the outcomes, the relatively limited dataset, the exploratory/predictive nature of the research, and the presence of a mediator in the model, the choice of PLS-SEM was justified for our analysis.

5. Empirical Results

5.1. Assessment of the Measurement Model

We start with an assessment of the reliability and validity of the questionnaire. The reliability of each specified research construct was checked before we performed the validity analysis. And it was conducted by examining the Cronbach’s alpha scores for each. In Table 3, we report Cronbach’s alpha with values between 0.837 and 0.911. All values are higher than the suggested minimum threshold of 0.7, thus representing an adequate level of internal consistency [70].

Table 3.

Internal consistency of the reflective constructs.

The validity of the questionnaire can be tested using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) index and Bartlett’s test of sphericity [10]. During Bartlett’s test of sphericity, it was found that all variables had p-values below 0.05, demonstrating that the questionnaire data are statistically significant and suitable for information extraction. Subsequently, the KMO values were assessed, and the results showed that the KMO values for all variables were above 0.7, indicating good validity (Table 4).

Table 4.

KMO and Bartlett.

5.2. Correlation Analysis

To further analyze the correlations among the variables, Pearson correlation analysis was conducted. Table 5 presents the results of the Pearson correlation analysis.

Table 5.

Pearson correlation analysis.

From Table 5, it is evident that there were significant positive correlations between the accuracy, novelty, diversity, and perceived usefulness (p < 0.01), and a significant negative correlation between algorithm aversion and the other variables (p < 0.01), which gives statistical support for our main hypotheses and mediation hypothesis. However, the correlation coefficients between privacy beliefs and other variables were low and not significant (p > 0.05), indicating a weak linear relationship among them.

5.3. Regression Analysis

Before conducting regression analysis, a collinearity diagnosis should be conducted to examine which variables should be deleted in the regression analysis. The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) is adopted as an indicator of the problem of multicollinearity. If the VIF is less than 10, it is generally assumed that there is no multicollinearity. From Table 6, it is seen that the VIF values for novelty, accuracy, and diversity are 5.402, 6.042, and 4.612, respectively, indicating that these three variables did not have collinearity issues and could be included in the regression analysis.

Table 6.

Regression analysis.

Then, accuracy, novelty, and diversity were treated as independent variables and algorithm aversion as the dependent variable in a linear regression analysis, with specific results presented in Table 6. The regression coefficient for accuracy is −0.371 (p < 0.01), indicating that accuracy has a significantly negative influence on algorithm aversion. The regression coefficient for novelty is −0.373 (p < 0.01), indicating that novelty has a significantly negative influence on algorithm aversion. The regression coefficient for diversity is −0.202 (p < 0.01), indicating that diversity has a significantly negative influence on algorithm aversion.

5.4. Mediation Analysis

Mediating effects indicate the intermediary role of perceived usefulness in the influence of accuracy, novelty, and diversity on algorithm aversion. In this study, a bootstrap method was used to examine the mediating effects, the detailed results of which are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Mediation analysis.

Results show that the coefficients of the mediating effect are −0.073, −0.076 and −0.072, respectively, with the bootstrap method’s 95% confidence intervals (95% BootCI) at [−0.152, −0.037], [−0.140, −0.027], and [−0.095, −0.020]. Since these three intervals do not include 0, they indicate that the three mediating effects are all significant. In other words, perceived usefulness has a significant mediating effect on the effects of recommendation accuracy, novelty, and diversity on buyers’ algorithm aversion.

5.5. Moderation Analysis

The moderating role of privacy beliefs on the relationships between accuracy, novelty, and diversity and buyers’ algorithm aversion were tested, respectively.

In Table 8, model 1 shows the results of the moderation regression model analyzing the effect of privacy beliefs on the relationship between accuracy and algorithm aversion. The coefficient for privacy beliefs is 0.072, and the p-value is below 0.05, demonstrating that privacy beliefs significantly positively influence algorithm aversion. However, the coefficient for the interaction term between accuracy and privacy beliefs (RA × PB) is −0.001, with a p-value of 0.879, indicating that the interaction term is not significant in the model. This suggests that privacy beliefs do not significantly moderate the relationship between accuracy and algorithm aversion.

Table 8.

Moderation analysis.

In Table 8, model 2 shows the results of the moderation regression model examining the effect of privacy beliefs on the relationship between novelty and algorithm aversion. The coefficient for privacy beliefs is 0.022, with a p-value greater than 0.05, indicating that privacy beliefs do not significantly affect algorithm aversion. The coefficient for the interaction term between novelty and privacy beliefs (RN × PB) is 0.001, with a p-value of 0.882, indicating that the interaction term is not significant in the model. This suggests that privacy beliefs do not significantly moderate the relationship between novelty and algorithm aversion.

In Table 8, model 3 shows the results of the moderation regression model analyzing the effect of user attitudes on the relationship between diversity and algorithm aversion. In the moderation regression model, the coefficient for privacy beliefs is −0.015, with a p-value above 0.05, suggesting that privacy beliefs do not have a significant impact on algorithm aversion. The coefficient for the interaction term between diversity and privacy belief (RD × PB) is 0.003, with a p-value of 0.802, indicating that the interaction term is not significant in the model. This implies that privacy beliefs do not significantly moderate the relationship between diversity and algorithm aversion.

These results, which show a non-significant moderating effect of privacy beliefs, align with the results of the Pearson correlation analysis (Table 5), where the correlation coefficients between privacy beliefs and the other variables are low and not significant (p > 0.05), indicating a very weak linear relationship.

6. Conclusions and Discussion

6.1. Findings

The current literature on time-series recommendation systems in e-commerce platforms primarily focuses on two aspects: optimizing sequential recommendation algorithms and refining the presentation of time-aware suggestions. While these systems satisfy modern buyers’ dynamically evolving preferences, their implementation raises ethical concerns such as privacy risks associated with cumulative data usage and information narrowing in long-term recommendation sequences. Although existing studies have identified the filter bubble effect in personalized sequential recommendations, most research concentrates on algorithm optimization for long-sequence forecasting and buyers’ rights regarding sequential data disclosure. However, they neglect two critical factors: current consumers’ understanding of time-series recommendation technologies and the specific impact of such systems on buyers’ algorithm aversion.

This study specifically examines Chinese e-commerce platforms, investigating how three characteristics of time-series recommendations (novelty with temporal relevance, diversity with long-term coverage, and accuracy with sequential consistency) along with perceived usefulness and privacy beliefs influence buyers’ algorithm aversion. The key findings are as follows:

Firstly, time-series recommendation quality significantly affects algorithm aversion. That is, the higher the accuracy of the recommendation—meaning the more the sequential recommendations align with users’ dynamically changing needs—the lower the user’s aversion to time-series recommendation systems. The higher the novelty of the recommendation—meaning the more the time-aware suggestions surprise buyers in contextually appropriate moments—the weaker their aversion to such systems. The higher the diversity of the recommendation—meaning the more balanced the coverage of long-term preference types that buyers receive—the weaker their aversion to time-series recommendation systems.

Secondly, perceived usefulness mediates the relationship between time-series recommendation quality and buyers’ algorithm aversion. When buyers find sequential recommendations accurate, temporally novel, and diversely comprehensive, they perceive the time-series system as more useful, which in turn reduces algorithm aversion. This mediating effect may be particularly pronounced in a Chinese context, where users often prioritize convenience in high-frequency e-commerce interactions.

Moreover, privacy beliefs do not show a significant moderating effect on the relationship between time-series recommendation quality and buyers’ algorithm aversion, which may be due to several reasons. For example, the relationship between privacy belief and algorithm aversion may be inherently complex rather than straightforwardly linear, especially in China, where users may balance privacy concerns with the practical benefits of personalized recommendations (e.g., tailored discounts and time savings). In addition, the measurement of user privacy beliefs may require further refinement to more precisely capture buyers’ actual psychological states and orientations toward sharing sequential behavioral data, which is critical for time-series recommendation systems.

6.2. Theoretical Contribution

Unlike traditional studies that focus on optimizing recommendation algorithms or refining presentation formats, this study centers on time-series recommendation information itself, examining three key dimensions—novelty, accuracy, and diversity—and their influence on buyers’ algorithm aversion, along with the underlying mechanisms. This enhances understanding of how time-series recommendation systems operate in e-commerce contexts.

This study makes two theoretical contributions. First, it enriches research on time-series recommendation systems by shifting focus from positive usage (e.g., trust building [11] and adoption encouragement [17]) to negative responses (algorithm aversion). As a critical barrier to the effectiveness of time-series recommendation systems, algorithm aversion demands attention, and this study addresses this gap by constructing and validating a TAM-based model that explores how multidimensional recommendation quality affects algorithm aversion and its boundary conditions.

Second, it extends the literature on buyers’ algorithm aversion by shifting the focus from algorithm attributes to temporal human–machine interaction processes and users’ subjective beliefs, thereby deepening understanding of their interplay. Specifically, recommendation information serves as a core interaction element between time-series recommendation systems and buyers. This study examines how three key quality indicators—novelty, accuracy, and diversity—influence algorithm aversion, integrates users’ subjective beliefs, and explores the mediating role of perceived usefulness and the moderating role of privacy beliefs. It thus provides a comprehensive analysis of the mechanisms behind buyers’ algorithm aversion from both temporal interaction and user perspectives.

6.3. Practical Implication

This study explores how the three dimensions of time-series recommendation quality (accuracy, novelty, and diversity) distinctively influence buyers’ algorithm aversion, offering actionable insights for optimizing time-series recommendation services—not only to enhance user experience and platform retention but also to facilitate data-driven decision-making across user and business contexts.

For e-commerce platform operators and designers, these findings provide a dual-path optimization framework. On one hand, refining recommendation systems to prioritize time-series-specific quality metrics—sequential accuracy, temporal relevance-aligned novelty, and diversity balancing short-term variety with long-term coverage—can reduce algorithm aversion. To achieve this, a recommendation interface could be designed to add a “temporal context tooltip” briefly explaining how it aligns with their long-term preferences (e.g., “Recommended based on your past 3 months of outdoor gear searches”) or seasonal relevance (e.g., “Timed for your usual winter coat purchases”). This transparency bridges the gap between users’ understanding of “why this recommendation now” and the system’s time-series logic, further mitigating aversion by demystifying sequential algorithms.

On the other hand, reduced algorithm aversion drives more authentic, sustained user interaction with time-series recommendations, making derived behavioral data (e.g., seasonal preference shifts and long-term interest evolution) more valuable for business decisions. Platform operators can leverage these patterns to optimize supply chain management (e.g., quarterly inventory adjustments via long-term preference forecasts) and refine marketing strategies (e.g., timed promotions for predicted interest peaks), connecting algorithmic time-series analysis to tangible business outcomes.

For e-commerce buyers, the research empowers more informed and dynamic decision-making. High sequential accuracy ensures recommendations “grow with user preferences” over time, supporting long-term shopping planning such as seasonal purchases, while timely novelty aligns with short-term emergent needs to enhance impulsive but satisfying purchases. Long-term diversity broadens exploration horizons, enabling users to discover products that match evolving lifestyles. As algorithm aversion decreases, users are more likely to integrate time-series recommendations into their regular shopping behavior, turning passive reception into active utilization of algorithmic insights for personalized, data-backed purchasing decisions.

6.4. Limitations

While this study provides empirical analysis of how time-series recommendation information influences buyers’ algorithm aversion, it has several limitations.

First, the sample was collected via voluntary online surveys of Chinese e-commerce platform users, introducing two layers of selection bias: (1) common self-selection in online surveys, and (2) context-specific bias from Chinese users’ familiarity with domestic platform ecosystems and algorithm norms. These limit result generalizability beyond Chinese e-commerce—for example, findings may not apply to regions with stronger privacy regulations (e.g., EU’s GDPR) or different platform logics (e.g., Amazon’s search-driven vs. Chinese social-commerce recommendations). Future research could expand samples to non-Chinese platforms (e.g., Amazon and Shopify) and compare cross-cultural differences.

Second, while we focused on three time-series recommendation quality dimensions (accuracy, novelty, and diversity), our measurements have inherent limitations: static questionnaires captured users’ retrospective ratings without verifying if they interacted with time-series systems. Since users reflected on long-term recommendation use, data may conflate time-series and general recommendation perceptions, weakening measurement specificity. Future studies could use scenario-based surveys (e.g., guiding recall of “past month purchase-based suggestions”) or platform interaction logs to improve accuracy.

Third, algorithm aversion formation is dynamic (e.g., evolving user preferences in time-series scenarios). We study temporal phenomena yet only capture a snapshot of users’ subjective beliefs via one survey. This static data fails to reflect how time-series recommendation quality shapes aversion over repeated interactions. Future research could adopt longitudinal designs (tracking attitudes over time) or experimental approaches (simulating long-term recommendation sequences) to uncover temporal mechanisms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.J.; methodology, Y.T.; software, Y.T.; validation, S.J.; formal analysis, Y.T.; investigation, L.L.; resources, T.C.; data curation, S.G.; writing—original draft preparation, S.J.; writing—review and editing, S.J.; visualization, L.L.; supervision, T.C.; project administration, T.C.; funding acquisition, T.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the State Grid Corporation of China under the project “Multi-Source Data Perception and Fusion Analysis Methods for Power Systems” (SGZJYF00DFJS2500023), the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province of China [Grant 2025AFB192].

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nguyen, K.M.; Nguyen, N.T.; Ngo, N.T.Q.; Tran, N.T.H.; Nguyen, H.T.T. Investigating Consumers’ Purchase Resistance Behavior to AI-Based Content Recommendations on Short-Video Platforms: A Study of Greedy And Biased Recommendations. J. Internet Commer. 2024, 23, 284–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yu, H.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, X. Impact of artificial intelligence recommendation on consumers’ willingness to adopt. J. Manag. Sci. 2020, 3, 121–125. [Google Scholar]

- Dietvorst, B.J.; Simmons, J.P.; Massey, C. Algorithm aversion: People erroneously avoid algorithms after seeing them err. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2015, 144, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Zheng, Y. When consumers need more interpretability of artificial intelligence (AI) recommendations? The effect of decision-making domains. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2023, 43, 3481–3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacon, A.; Reyes, T.; Kausel, E.E. Are engineers more likely to avoid algorithms after they see them err? A longitudinal study. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2024, 44, 789–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.; Kee, K.F.; Shin, E.Y. Algorithm awareness: Why user awareness is critical for personal privacy in the adoption of algorithmic platforms? Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 65, 102494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, T.-Y.; Tseng, Y.-C.; Yuan, C.W.T. Is this AI sexist? The effects of a biased AI’s anthropomorphic appearance and explainability on users’ bias perceptions and trust. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2024, 76, 102775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Kumar, V. Robotics for customer service: A useful complement or an ultimate substitute? J. Serv. Res. 2021, 24, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaminathan, V.; Lepkowska-White, E.; Rao, B.P. Browsers or buyers in cyberspace? An investigation of factors influencing electronic exchange. J. Comput.-Mediated Commun. 1999, 5, JCMC523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayasarathy, L.R. Predicting consumer intentions to use on-line shopping: The case for an augmented technology acceptance model. Inf. Manag. 2004, 41, 747–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilashi, M.; Jannach, D.; bin Ibrahim, O.; Esfahani, M.D.; Ahmadi, H. Recommendation quality, transparency, and website quality for trust-building in recommendation agents. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2016, 19, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidlauskiene, J. What Drives Consumers’ Decisions to Use Intelligent Agent Technologies? A Systematic Review. J. Internet Commer. 2021, 21, 438–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; van Doorn, J.; Eggers, F.; Wieringa, J.E. The effect of required warmth on consumer acceptance of artificial intelligence in service: The moderating role of AI-human collaboration. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 66, 102533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.; Zhong, B.; Biocca, F.A. Beyond user experience: What constitutes algorithmic experiences? Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 52, 102061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Amos, C. Dignity and use of algorithm in performance evaluation. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2024, 43, 401–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, F.; Zhang, X. Artificial intelligence or human: When and why consumers prefer AI recommendations. Inf. Technol. People 2023, 38, 279–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Yang, F.; Men, J. Recommendation content matters! Exploring the impact of the recommendation content on consumer decisions from the means-end chain perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2023, 68, 102589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.-P.; Lai, H.-J.; Ku, Y.-C. Personalized content recommendation and user satisfaction: Theoretical synthesis and empirical findings. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2006, 23, 45–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whang, C.; Im, H. Does recommendation matter for trusting beliefs and trusting intentions? Focused on different types of recommender system and sponsored recommendation. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2018, 46, 944–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roudposhti, V.M.; Nilashi, M.; Mardani, A.; Streimikiene, D.; Samad, S.; Ibrahim, O. A new model for customer purchase intention in e-commerce recommendation agents. J. Int. Stud. 2018, 11, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminskas, M.; Bridge, D. Diversity, serendipity, novelty, and coverage: A survey and empirical analysis of beyond-accuracy objectives in recommender systems. ACM Trans. Interact. Intell. Syst. 2016, 7, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yang, Y.; Wang, N.; Yang, K.; Yuan, Q. How serendipity improves user satisfaction with recommendations? a large-scale user evaluation. In Proceedings of the World Wide Web Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 May 2019; pp. 240–250. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, B.; Benbasat, I. E-commerce product recommendation agents: Use, characteristics, and impact. MIS Q. 2007, 31, 137–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Zhou, L.; Miller, L.; Ieromonachou, P. User resistance in IT: A literature review. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhu, G.; Qian, W.; Wu, Y.; Huang, J.; Yang, Z. Algorithm Aversion in the Era of Artificial Intelligence: Research Framework and Future Agenda. J. Manag. World 2023, 39, 205–233. [Google Scholar]

- Dhar, V. When to trust robots with decisions, and when not to. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2016, 17. Available online: https://hbr.org/2016/05/when-to-trust-robots-with-decisions-and-when-not-to (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Longoni, C.; Cian, L. Artificial intelligence in utilitarian vs. hedonic contexts: The “word-of-machine” effect. J. Mark. 2022, 86, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, K.; Wegner, D.M. Feeling robots and human zombies: Mind perception and the uncanny valley. Cognition 2012, 125, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granulo, A.; Fuchs, C.; Puntoni, S. Preference for human (vs. robotic) labor is stronger in symbolic consumption contexts. J. Consum. Psychol. 2021, 31, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logg, J.M.; Haran, U.; Moore, D.A. Is overconfidence a motivated bias? Experimental evidence. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2018, 147, 1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, V.A.; Probst, C.A.; Merkle, E.C.; Arkes, H.R.; Medow, M.A. Why do patients derogate physicians who use a computer-based diagnostic support system? Med. Decis. Mak. 2013, 33, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, E.; Paolacci, G.; Puntoni, S. Man versus machine: Resisting automation in identity-based consumer behavior. J. Mark. Res. 2018, 55, 818–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.S.; Karahanna, E. Online recommendation systems in a B2C E-commerce context: A review and future directions. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2015, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herlocker, J.L.; Konstan, J.A.; Terveen, L.G.; Riedl, J.T. Evaluating collaborative filtering recommender systems. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. 2004, 22, 5–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, S.; Castells, P. Rank and relevance in novelty and diversity metrics for recommender systems. In Proceedings of the Fifth ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, Chicago, IL, USA, 23–27 October 2011; pp. 109–116. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, M.; Delgado-Battenfeld, C.; Jannach, D. Beyond accuracy: Evaluating recommender systems by coverage and serendipity. In Proceedings of the Fourth ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, Barcelona, Spain, 26–30 September 2010; pp. 257–260. [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrand, M.D.; Harper, F.M.; Willemsen, M.C.; Konstan, J.A. User perception of differences in recommender algorithms. In Proceedings of the 8th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, Foster City, CA, USA, 6–10 October 2014; pp. 161–168. [Google Scholar]

- Said, A.; Fields, B.; Jain, B.J.; Albayrak, S. User-centric evaluation of a k-furthest neighbor collaborative filtering recommender algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2013 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, San Antonio, TX, USA, 23–27 February 2013; pp. 1399–1408. [Google Scholar]

- Bodoff, D.; Ho, S.Y. Effectiveness of website personalization: Does the presence of personalized recommendations cannibalize sampling of other items? Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2015, 20, 208–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Su, J.; Li, Z. An investigation into the acceptance of intelligent care systems: An extended technology acceptance model (TAM). Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.; Yu, Z. Investigating users’ acceptance of the metaverse with an extended technology acceptance model. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 5810–5826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarifis, A.; Kawalek, P.; Azadegan, A. Evaluating If Trust and Personal Information Privacy Concerns Are Barriers to Using Health Insurance That Explicitly Utilizes AI. J. Internet Commer. 2020, 20, 66–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Dong, X. Consumption information sharing behavior in virtual community. J. Intell. 2014, 33, 201–207. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud, H.; Islam, A.N.; Ahmed, S.I.; Smolander, K. What influences algorithmic decision-making? A systematic literature review on algorithm aversion. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 175, 121390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogert, E.; Schecter, A.; Watson, R.T. Humans rely more on algorithms than social influence as a task becomes more difficult. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhavan, P.; Wiegmann, D.A.; Lacson, F.C. Automation failures on tasks easily performed by operators undermine trust in automated aids. Hum. Factors 2006, 48, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNee, S.M.; Riedl, J.; Konstan, J.A. Being accurate is not enough: How accuracy metrics have hurt recommender systems. In Proceedings of the CHI’06 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montréal, QC, Canada, 22–27 April 2006; pp. 1097–1101. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.-C.; Lu, H. Towards an understanding of the behavioural intention to use a web site. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2000, 20, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vervoort, A.; Declercq, P.-Y. Upward surface movement above deep coal mines after closure and flooding of underground workings. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2018, 28, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremonesi, P.; Garzotto, F.; Negro, S.; Papadopoulos, A.; Turrin, R. Comparative evaluation of recommender system quality. In Proceedings of the CHI’11 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 7–12 May 2011; pp. 1927–1932. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, C.-N.; McNee, S.M.; Konstan, J.A.; Lausen, G. Improving recommendation lists through topic diversification. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on World Wide Web, Chiba, Japan, 10–14 May 2005; pp. 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, X.; Zhang, X.; Yang, J.; Shen, X.; Zhang, Z. Online Reviews, Perceived Usefulness and New Product Diffusion. Chin. Soft Sci. 2017, 1, 162–171. [Google Scholar]

- Aksoy, L.; Bloom, P.N.; Lurie, N.H.; Cooil, B. Should recommendation agents think like people? J. Serv. Res. 2006, 8, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komiak, S.Y.; Benbasat, I. The effects of personalization and familiarity on trust and adoption of recommendation agents. MIS Q. 2006, 30, 941–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, P.Y.; Ho, S.Y.; Ho, K.K.; Yao, Y. Examining the effects of malfunctioning personalized services on online users’ distrust and behaviors. Decis. Supp. Syst. 2013, 56, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, H.-T. Shaping path of trust: The role of information credibility, social support, information sharing and perceived privacy risk in social commerce. Inf. Technol. People 2023, 36, 683–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, F.; Berbekova, A.; Assaf, A.G. Understanding and managing the threat of common method bias: Detection, prevention and control. Tour. Manag. 2021, 86, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.L. Revisiting sample size and number of parameter estimates: Some support for the N: Q hypothesis. Struct. Equ. Model. 2003, 10, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knijnenburg, B.P.; Willemsen, M.C.; Gantner, Z.; Soncu, H.; Newell, C. Explaining the user experience of recommender systems. User Model. User-Adapt. Interact. 2012, 22, 441–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, D.; Knijnenburg, B.P.; Willemsen, M.C.; Graus, M. Understanding choice overload in recommender systems. In Proceedings of the Fourth ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, Barcelona, Spain, 26–30 September 2010; pp. 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.S.; Wu, S.; Tsai, R.J. Integrating perceived playfulness into expectation-confirmation model for web portal context. Inf. Manag. 2005, 42, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.-W.; Kim, Y.-G. Extending the TAM for a World-Wide-Web context. Inf. Manag. 2001, 38, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, S.; Wasenden, O.-C.; Gronnevet, G.-A.; Ling, R. A tripartite model of trust in Facebook: Acceptance of information personalization, privacy concern, and privacy literacy. Media Psychol. 2020, 23, 840–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Du, Y.; Bai, Q. Why do people resist algorithms? From the perspective of short video usage motivations. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 941640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusa, R.; Suder, M.; Duda, J. Role of entrepreneurial orientation, information management, and knowledge management in improving firm performance. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2024, 78, 102802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinartz, W.; Haenlein, M.; Henseler, J. An empirical comparison of the efficacy of covariance-based and variance-based SEM. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2009, 26, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusa, R. The mediating role of competitive and collaborative orientations in boosting entrepreneurial orientation’s impact on firm performance. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2023, 11, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaran, U. Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).