Abstract

Reflectarray antenna design traditionally depends on computationally intensive full-wave simulations and experimental measurements, which significantly increase design time and cost. To address these limitations, we propose PhaseNet, an end-to-end deep learning framework that leverages phase maps and radiation angles as inputs to predict reflectarray antenna gain values. PhaseNet integrates spatial features extracted by a convolutional neural network (CNN) backbone with an angle-embedding module, and employs a regression head to enable efficient forward prediction. After training, the model achieves near-real-time inference with a single forward pass, facilitating rapid exploration of high-dimensional design spaces and providing immediate design feedback. In addition, we introduce two novel evaluation metrics, Half-Power Beamwidth (HPBW) and Main-Lobe Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), which allow for a multidimensional evaluation of prediction performance across the full radiation pattern and within the critical main-lobe region. These metrics provide refined criteria for reflectarray antenna design optimization beyond conventional error measures. In particular, PhaseNet achieved the best performance compared to existing models on these newly proposed evaluation metrics, recording up to 0.45 lower HPBW RMSE than existing methods, thereby validating both the relevance of the metrics and the effectiveness of the model. To further enhance practicality, we present a rapid generation of diverse bit-encoded datasets, substantially reducing the time and cost associated with data acquisition. Overall, the proposed framework effectively reduces prediction errors in reflectarray antenna design.

Keywords:

antenna; reflectarray antenna; antenna design optimization; convolutional neural network (CNN); deep learning; evaluation metrics; reflectarray antenna data generation MSC:

78A50; 62M45; 82C32; 68M20; 68T05

1. Introduction

The advancement of next-generation technologies, such as 5G/6G wireless communications and space exploration systems, has exponentially increased the demand for high-gain, high-efficiency antennas. While parabolic reflectors are too bulky and phased arrays require complex, lossy feeding networks [1,2], the reflectarray antenna has emerged as a compelling alternative. It merges the spatial feeding of a reflector with the planar architecture of a phased array, offering a low-profile, lightweight, and easily fabricated solution ideal for modern applications like Low-Earth-Orbit Satellites. The reflectarray thus resolves the long-standing trade-off between performance and complexity.

Despite its conceptual simplicity, practical reflectarray design is a multi-objective optimization problem fraught with challenges, including achieving a full 360° phase range, overcoming a narrow bandwidth, and accounting for mutual coupling between elements [1,3,4]. The relationship between the geometry of thousands of unit cells and the far-field radiation pattern is highly non-linear, making an exhaustive search for an optimal solution computationally infeasible [5]. This complexity creates a severe computational bottleneck, as traditional design relies on time-consuming computational electromagnetic (CEM) solvers like HFSS or CST [6,7,8]. The need for thousands of iterative simulations stifles innovation, trapping designers in incremental improvements rather than allowing for the exploration of novel, high-performance designs.

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) offer a transformative paradigm to overcome this bottleneck. Data-driven surrogate models, trained on high-fidelity simulation data, can learn complex physics and provide near-real-time predictions, dramatically accelerating the design process. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are particularly well-suited for this task, as they can effectively learn the spatial correlations within the 2D phase map of a reflectarray that determine the radiation pattern. This approach represents a fundamental shift from “physics-based simulation” to “physics-informed inference,” enabling not only rapid forward prediction but also opening pathways to solve the challenging inverse design problem. Although the application of ML in antenna design has been increasing [9,10,11,12,13], a dedicated end-to-end framework for reflectarrays is still lacking [14,15]. In particular, existing approaches fail to efficiently capture the highly non-linear relationship between thousands of phase cells and complex radiation patterns, resulting in significant computational cost and long exploration time during the design process. To address these issues, this paper proposes PhaseNet, a deep learning framework that directly predicts antenna gain from 2D phase maps and radiation angles, enabling fast and efficient exploration of high-dimensional design spaces. This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a detailed description of the proposed data-generation process, evaluation metrics, and the PhaseNet framework. Section 3 presents the experimental results on reflectarray antenna optimization based on the proposed model. Section 4 offers an in-depth analysis of the experimental results, and finally, Section 5 summarizes and concludes the work. The key contributions of this work are:

- To address the limitations of conventional regression metrics such as MSE, RMSE, and in capturing the local characteristics of antenna radiation patterns, we introduce two novel domain-specific evaluation measures—Half-Power Beamwidth (HPBW) RMSE and Main-Lobe RMSE.

- Through the design and validation of the PhaseNet architecture, we achieved state-of-the-art prediction accuracy, recording an HPBW RMSE up to 0.45 lower than that of existing methods.

2. Method

2.1. Data Generation

Separate input text (.txt) files were prepared for each bit depth. From the second line to the N-th line of each file, the element position and the phase angle (degrees) are recorded, where the phase angles are uniformly sampled in the −180° to +180° range and sorted in descending order from positive to negative. The number of possible angle combinations is determined by ; for example, the 1-bit dataset contains two unique combinations, and the 2-bit dataset contains four unique combinations. All combinations are constructed without duplication, providing a systematic and consistent dataset for phase map generation across different bit data. The pseudocode for this process is presented in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 Random Generation of Phase-Combination Sets |

| Require: bit depth b, target count N, maximum attempts |

| Ensure: set of N unique signed phase combinations or Failure |

| Notation: , , |

| while do |

| if then |

| end if |

| end while |

| if then |

| return |

| else |

| return Failure |

| end if |

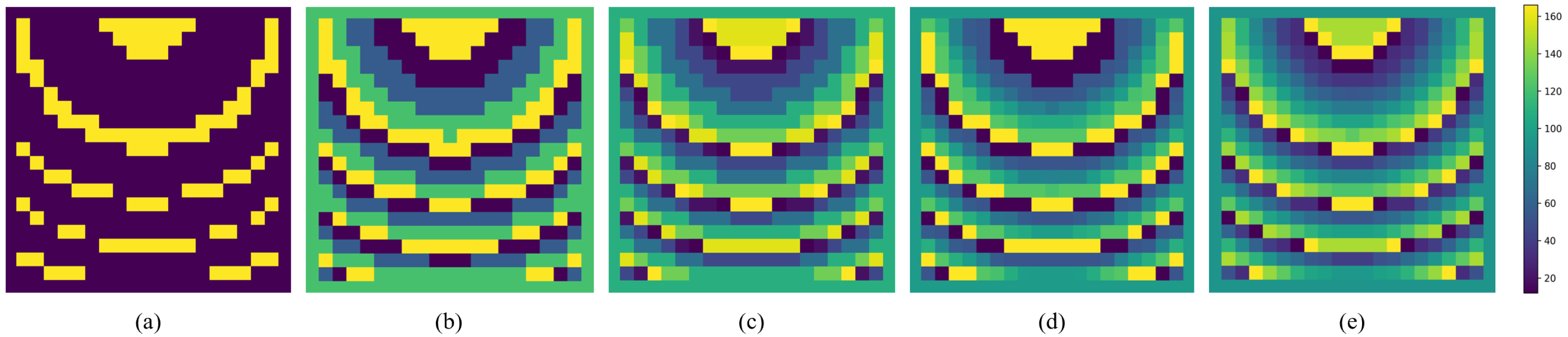

The following physical parameters were fixed for all experiments during data generation. A square-patch reflectarray antenna was assumed, with a cell size of 18.5 mm, an operating frequency of 8 GHz, and a Q-factor of 3. The antenna dimensions were set to 370 mm × 370 mm, and the feed-point coordinates were defined as (X, Y, Z) = (−185, 0, 370) mm. Based on the phase angles (degrees) recorded in the input text files and the specified bit depth, a 20 × 20 grid was constructed and each grid point was assigned a discretized phase value snapped to the bit-data lookup table. The resulting phase map is shown as an example in Figure 1, and the gain was computed by processing this phase map together with the radiation angle information. Finally, 91 gain values were extracted by sampling the −45° to +45° range in 1° increments. The outcome of the data-generation process consists of the gain values corresponding to each phase map, along with the associated radiation angle (phi) values. Algorithm 2 was used for phase map generation, and Algorithm 3 was used to calculate gain values from the generated phase map over the −45° to +45° range. A dataset of 10,000 samples was assembled—2000 samples for each bit data from 1 to 5—and used for subsequent model training and evaluation.

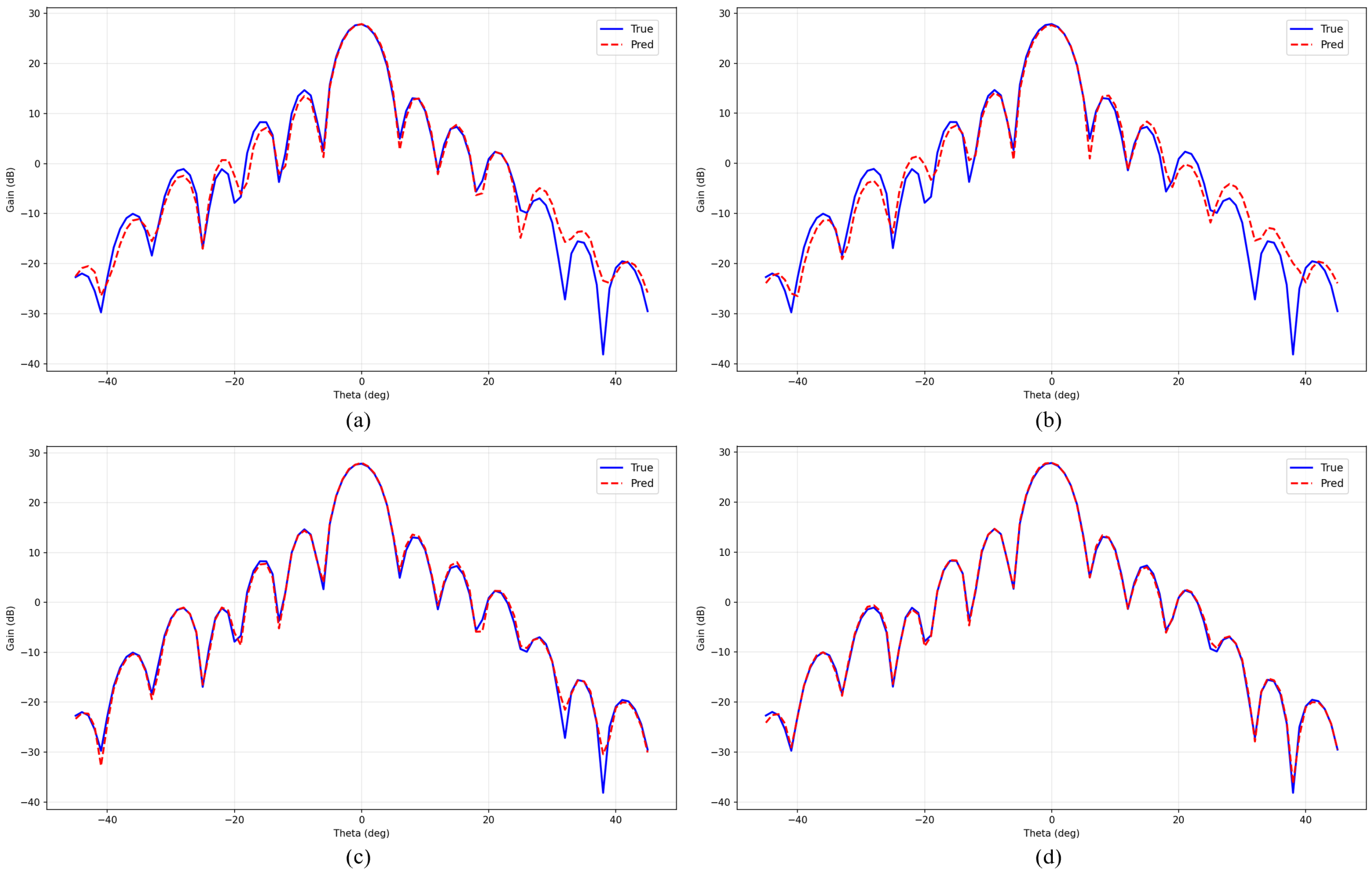

Figure 1.

Visualization of 20 × 20 phase maps for different bit data: (a) 1-bit data, (b) 2-bit data, (c) 3-bit data, (d) 4-bit data, and (e) 5-bit data.

| Algorithm 2 Phase Map Generation |

| Require: input_dir, output_dir |

| Ensure: (in memory) |

| Check that input_dir exists; create output_dir if needed. |

| Initialize fixed parameters |

| ▹ feed coords |

| Compute derived constants |

| Generate coordinate grid |

| for all do |

| Clamp to |

| Append to |

| end for |

| return |

| Algorithm 3 Selective E/H-Plane Gain Data Generation |

| Require: input_dir, output_dir, target_pairs |

| Ensure: (in memory) |

| Notation: |

| ; ; |

| Check I/O: Verify input_dir exists; create output_dir if needed. |

| if target_pairs not provided then |

| target_pairs |

| end if |

| Initialize fixed parameters |

| ; |

| ; |

| ; ; ; ; |

| Compute derived constants |

| ; ; |

| Collect files |

| sorted list of *.txt in |

| ; |

| for all do |

| if then |

| return |

| end if |

| Read LUT from . |

| if duplicate phase values detected then |

| continue ▹ skip file |

| end if |

| Compute phase map |

| Clamp and snap to nearest LUT levels. |

| Compute element and feed patterns |

| ; |

| Synthesize total field and normalize. |

| Extract E-/H-plane cuts at and compute ,. |

| if then |

| continue ▹ skip file |

| end if |

| Append current result to |

| end for |

| return |

2.2. Metrics

Traditional regression metrics such as Mean Squared Error (MSE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and the coefficient of determination () are commonly employed in prior studies [16,17] for performance comparison and analysis. MSE computes the average of the squared differences between predicted and actual values, making it sensitive to large errors and indicative of overall predictive performance. RMSE, the square root of MSE, expresses the average error magnitude in the original units, showing how far predictions deviate from actual values on average. represents the proportion of variance in the actual values explained by the predictions, measuring how well the model accounts for the observed data.

However, these metrics alone may fail to capture the local shape of an reflectarray antennas radiation pattern or the prediction performance within the main-beam or main-lobe region. Since MSE and RMSE average errors across all samples, they treat low-gain regions and the main lobe with equal importance. Similarly, , based on overall variance, may underrepresent small but critical errors in high-importance regions.

In antenna radiation analysis, the Half-Power Beamwidth (HPBW)—defined as the angular span from the maximum gain down to the −3 dB point—measures the main-beam region, which directly affects communication quality and coverage. Examining up to the −10 dB point further includes secondary radiation regions beyond the main-beam region, providing a more comprehensive assessment of pattern reliability in practical environments. Focusing on the −3 dB and −10 dB intervals is crucial because the detailed shapes of the main-beam and main-lobe often determine antenna gain performance in real applications. Inspired by these radiation characteristics, this study introduces HPBW RMSE and Main-Lobe RMSE to separately quantify prediction performance within the main-beam and main-lobe regions and utilize these measures as refined optimization criteria.

2.2.1. Half-Power Beamwidth RMSE

Half-Power Beamwidth RMSE (HPBW RMSE) is a metric designed to quantify the precision of prediction models within the main-beam region of an reflectarray antenna. First, for each radiation pattern sample, the angular range from the maximum gain down to the −3 dB point is identified, and the errors between the actual gain values and the predicted values within this range are computed. These errors are then squared, summed, averaged over the number of samples N, and the square root of this average is taken to calculate

By focusing exclusively on the localized and high-importance main-beam region rather than the entire pattern, this metric enables more accurate evaluation of prediction performance in the critical radiation zone that directly impacts communication quality. It also provides a consistent basis for comparing main-beam prediction errors across different designs, clearly highlighting performance differences during optimization, and, when used in conjunction with Main-Lobe RMSE, serves as a multifaceted evaluation criterion encompassing both main-beam and main-lobe variations.

2.2.2. Main-Lobe RMSE

Main-Lobe RMSE is similar to HPBW RMSE but extends the measurement range from the maximum gain down to −10 dB, encompassing not only the primary radiating region within the main lobe but also the secondary radiating region at the lobe’s periphery. For each radiation pattern sample, the angular range from the maximum gain to −10 dB is identified, and the errors between all actual gain values and predicted values within this range are computed. These errors are then squared, summed, averaged over the number of samples N, and the square root of this average is taken to calculate

By covering both the core of the main lobe and its surrounding radiation shape, this metric evaluates pattern reliability in practical environments. Extending the range to −10 dB allows for the validation of model performance in real-world conditions, including receiver sensitivity and secondary radiation regions. Additionally, by providing a consistent measure of prediction error across various designs and frequency conditions, Main-Lobe RMSE enables a clearer assessment of model generalization performance and practical applicability.

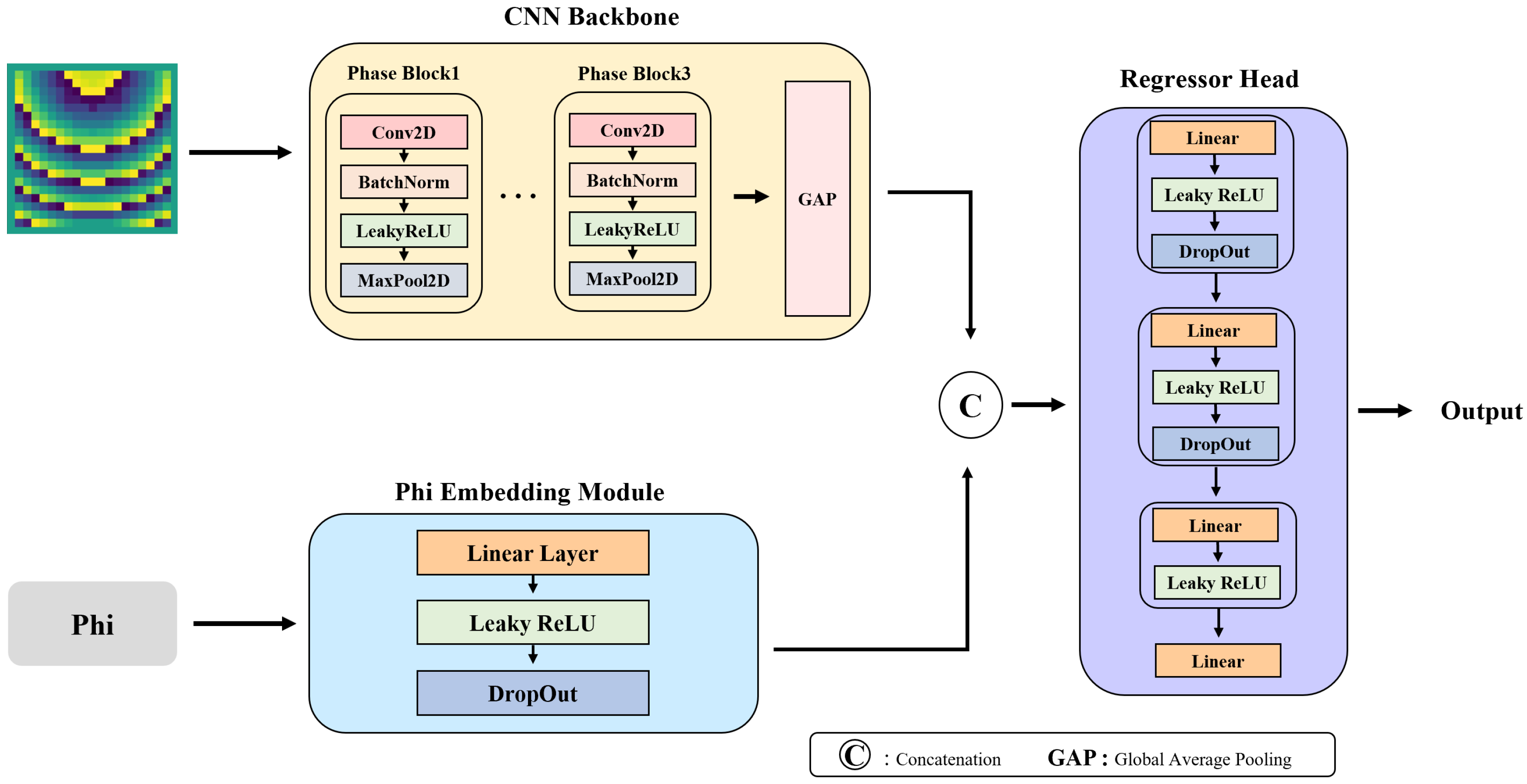

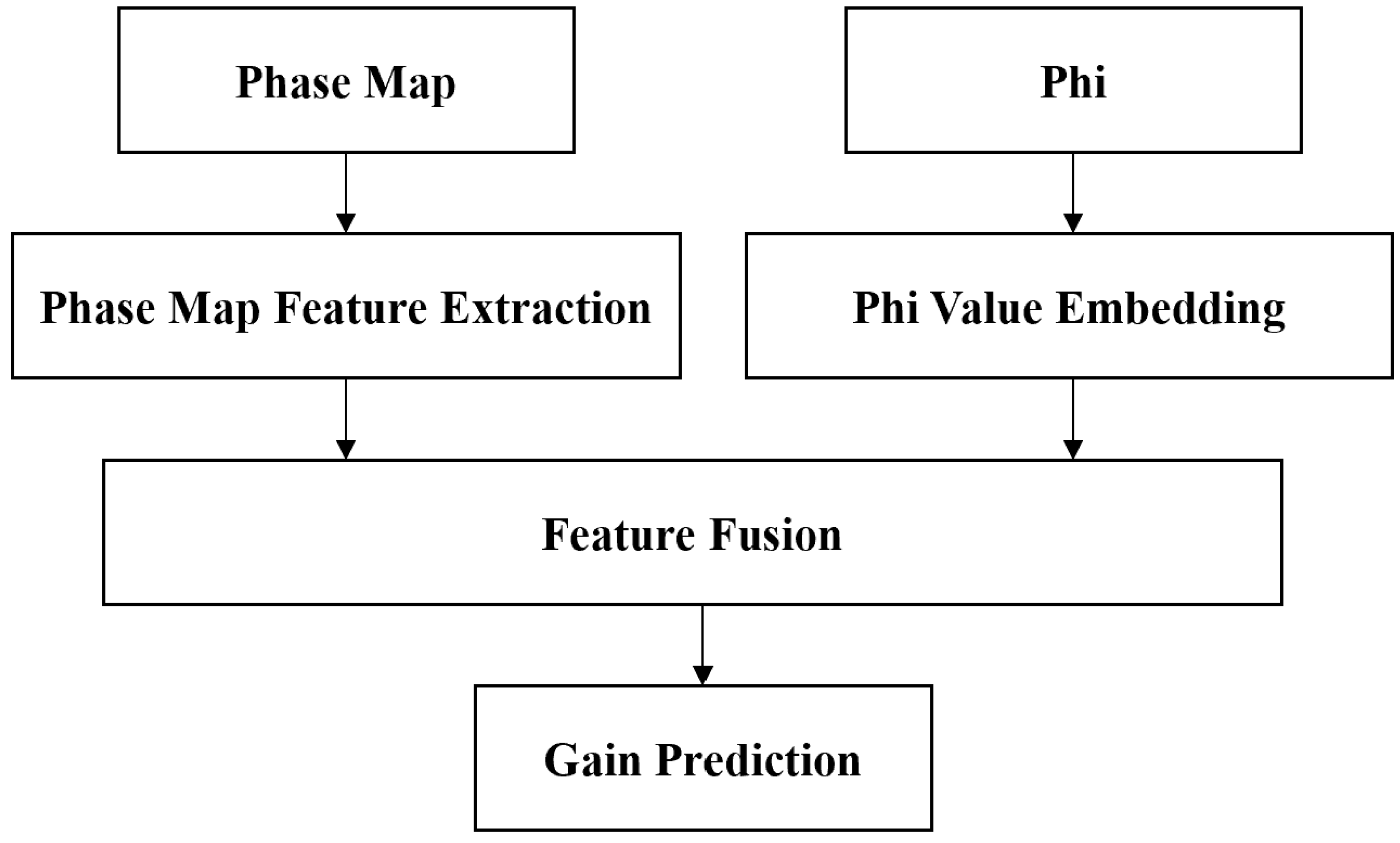

2.3. Model Architecture

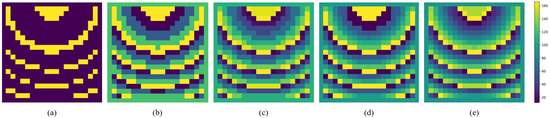

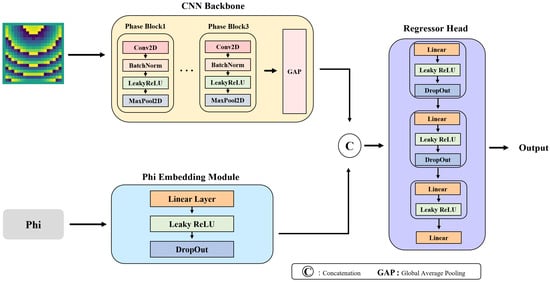

PhaseNet consists of two independent modules that process the phase map and the phi angle, respectively. An overview of this dual-module design is shown in Figure 2, and it enables the optimized handling of inputs with different characteristics. In addition, a block diagram representation of PhaseNet is provided in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Overview of our PhaseNet framework. A three-block CNN backbone with GAP extracts features from the 20 × 20 phase map, while a Linear → LeakyReLU → Dropout embedding encodes the scalar phi angle. The resulting 128- and 16-dimensional vectors are concatenated and passed through a lightweight regressor head to predict reflectarray antenna gain in a single forward pass.

Figure 3.

Block diagram of PhaseNet.

2.3.1. Phase Map CNN Backbone

The CNN backbone module for phase map processing comprises three Phase Blocks followed by Global Average Pooling (GAP). Each Phase Block consists of Conv2d, BatchNorm2d, LeakyReLU activation, and MaxPool2d. Given a 20 × 20 phase map , the backbone produces a feature tensor

which is then compressed into a 128-dimensional vector by

The key advantage of the CNN-based approach is its ability to preserve the spatial structure of the phase map while hierarchically extracting local patterns and global features. In particular, the translation invariance of convolution operations allows for the robust learning of spatial correlations and patterns within the phase map, and the multi-layer architecture captures features from low-level local details to high-level complex patterns.

2.3.2. Phi-Embedding Module

The phi-embedding module transforms the scalar phi value into a 16-dimensional vector via a sequence of a Linear layer, LeakyReLU activation, and Dropout:

Mapping the one-dimensional directional information into a higher-dimensional feature space enhances representational power when combined with the phase map, while Dropout regularization prevents the embedding from over-relying on specific patterns.

The independent design of the two modules allows for the optimized processing of phase map spatial information and phi directional information, and enables individual analysis and optimization of each component’s contribution.

2.3.3. Feature Fusion and Regression

The 128-dimensional phase feature and the 16-dimensional phi embedding are concatenated to form a 144-dimensional combined feature vector

which is passed through the regressor head to predict the final gain . The regressor head consists of two fully connected blocks and additional layers, defined by

Through this process, PhaseNet processes the input phase map and phi via optimized pathways and achieves near real-time reflectarray antenna gain prediction with a single forward pass.

3. Experimental Results

3.1. Implementation Details

All code was implemented using the PyTorch 2.9.0 framework, and experiments were conducted on an NVIDIA A6000 GPU. Mean squared error (MSE) was used as the loss function, and the AdamW optimizer was configured with a weight decay of 1 × 10−4. Training ran for 15,000 epochs with an initial learning rate of 1 × 10−3. A ReduceLROnPlateau scheduler was employed to halve the learning rate whenever validation loss failed to improve. During training, the model with the lowest validation HPBW RMSE was saved as the best model. Finally, both proposed RMSE metrics (HPBW RMSE and Main-Lobe RMSE) were computed on the test set for comprehensive performance evaluation.

3.2. Comparison with Other Deep Learning Models

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed PhaseNet, we selected a diverse set of representative deep learning models specialized for different data types and structures as baselines. TabNet [18] is a leading model for tabular data; Image CNN-LSTM [19] represents a hybrid approach combining spatial and sequential feature extraction; and Ski-Le-BNN [20] is a recent CNN-based model from the reflectarray antenna modeling field. This comparison aims to demonstrate the superior structural efficiency and prediction performance of PhaseNet.

Using the phase maps, phi angles, and gain data generated in this work, we compared the performance of existing deep learning models against our proposed PhaseNet. At this stage, both the existing deep learning models and PhaseNet were trained under the same conditions using the dataset proposed in this study, with the proposed RMSE metrics (HPBW RMSE and Main-Lobe RMSE) applied to all models, and the results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Performance comparison of different modeling methods for reflectarray antennas. The best performance for each Data(bit) is marked in bold.

The proposed PhaseNet consistently achieved the best performance across all bit datas. In particular, it recorded the lowest errors in both HPBW RMSE and Main-Lobe RMSE, which evaluate the antenna’s critical radiation regions.

For the 1-bit dataset, PhaseNet improved HPBW RMSE by 0.17 compared to TabNet, 0.13 compared to Image CNN-LSTM, and 0.11 compared to Ski-Le-BNN. In the 2-bit dataset, PhaseNet demonstrated especially pronounced gains, outperforming TabNet by 0.32 and Image CNN-LSTM by 0.38, with a 0.03 advantage over Ski-Le-BNN. Performance superiority persisted for the 3-bit and 4-bit datasets, and for the 5-bit dataset, PhaseNet achieved remarkable improvements of 0.1 over TabNet and Ski-Le-BNN. These results suggest that PhaseNet’s ability to learn spatial patterns becomes increasingly effective as bit data increases.

In addition, the model complexity of TabNet, Image CNN-LSTM, Ski-Le-BNN, and PhaseNet was compared in terms of the number of parameters and FLOPs. TabNet had approximately 2.31 million parameters and 126.65 million FLOPs, making it the heaviest structure with the highest computational cost. Image CNN-LSTM contained about 1.06 million parameters and 4.97 million FLOPs, exhibiting a relatively lightweight configuration. Ski-Le-BNN recorded around 0.35 million parameters and 0.59M FLOPs, achieving the lowest computational cost among the four models. In contrast, the proposed PhaseNet had 177 K parameters and 2.34 M FLOPs, showing the smallest number of parameters while recording the second-lowest FLOPs. This indicates that PhaseNet can effectively learn complex spatial correlations by performing more computations in the CNN-based phase map processing, even with a small number of parameters, as summarized in Table 2

Table 2.

Model complexity comparison in terms of parameters and FLOPs.

3.3. Ablation Study

To quantitatively analyze the crucial role of each component in PhaseNet for reflectarray antenna gain prediction, we conducted three systematic ablation studies: (1) analysis of the impact of converting phase maps to 1D vectorized inputs on performance; (2) verification of the effects of removing the phi-embedding module; and (3) evaluation of each block’s contribution by progressively removing PhaseBlock structures from the CNN backbone. The comprehensive results of these ablation studies are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Ablation study of PhaseNet across different configurations. ‘O’ indicates that Phi Embedding was used, and ‘X’ indicates it was not. The best performance for each Data(bit) is marked in bold.

To evaluate the impact of preserving the 2D spatial layout of the phase map, we compared the standard 2D input against a 1D vectorized input. For 1-bit data, the 1D input increased HPBW RMSE from 0.17 to 2.10 () and Main-Lobe RMSE from 0.21 to 2.67 (). Both HPBW RMSE and Main Lobe RMSE consistently increased from 2-bit to 5-bit, confirming performance degradation of 1D vectorized input compared to 2D input. In 5-bit setting, HPBW RMSE degraded by up to 1.08 and Main-Lobe RMSE by up to 1.05, underscoring the importance of preserving the phase map’s 2D spatial structure. These results support that the 2D layout is indispensable for learning spatial patterns in the phase map.

Removing the phi input led to a substantial degradation across all bit-data settings. For 1-bit data, HPBW RMSE from 0.17 to 2.35 ( = 2.18), and Main-Lobe RMSE from 0.21 to 2.89 ( = 2.68). Similarly, for 2–5-bit settings, the maximum observed difference in HPBW RMSE was 2.18 (5-bit setting), and the smallest observed difference in HPBW RMSE was 1.66 (2-bit setting). In every metric and for every bit data, the full model with the phi embedding significantly outperformed the variant without it, demonstrating that explicit encoding of phi angle information is critical for accurate prediction in the antenna’s key radiation regions.

We further evaluated the role of each Phase Block by conducting experiments using only Phase Blocks 1 and 2 (removing Phase Block 3) and using only Phase Block 1 (removing Phase Blocks 2 and 3). Both experiments led to severe performance drops relative to the full model. For 1-bit data, when using only Phase Blocks 1, HPBW RMSE increased from 0.17 to 2.08 () and Main-Lobe RMSE increased from 0.21 to 2.49 (). Similar performance degradation occurred when using only Phase Block 1 and 2: HPBW RMSE increased from 0.17 to 2.24 () and Main-Lobe RMSE increased from 0.21 to 2.70 (). The same trend held for 2-bit through to 5-bit data. In 4-bit data, using only Phase Block 1 further destabilized predictions with HPBW RMSE increasing from 0.04 to 1.94 (), and using only Phase Blocks 1 and 2 raised HPBW RMSE from 0.04 to 1.42 (). These findings confirm that a multi-layer convolutional block structure is essential for effectively learning both local and global patterns in the phase map.

We compared the data-generation time of algorithm-based methods with the prediction time of the proposed PhaseNet. The results, as summarized in Table 4, clearly show that PhaseNet enables the identification of optimal gain values much faster than conventional data-generation approaches.

Table 4.

Comparison of data-generation time across different methods.

4. Discussion

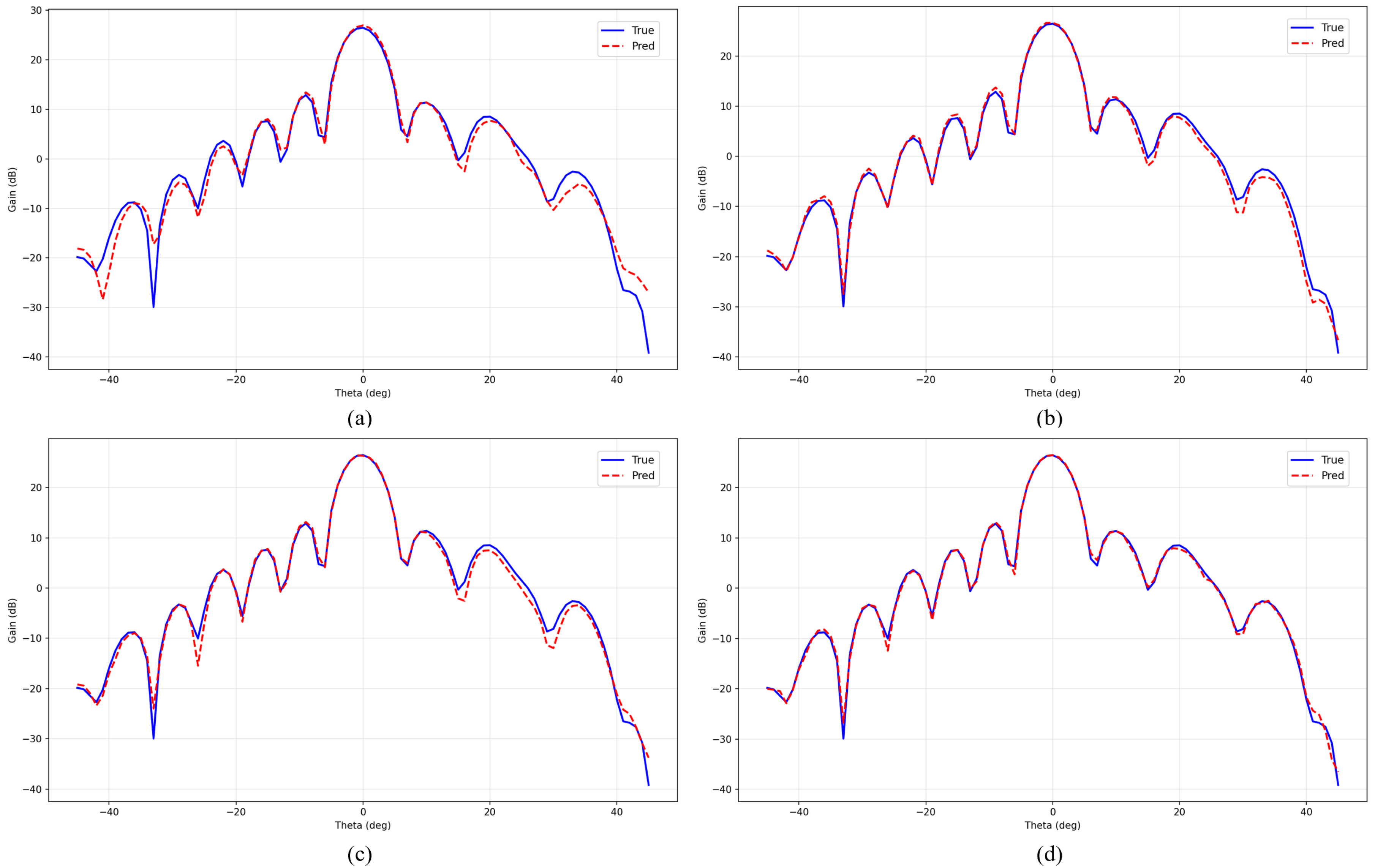

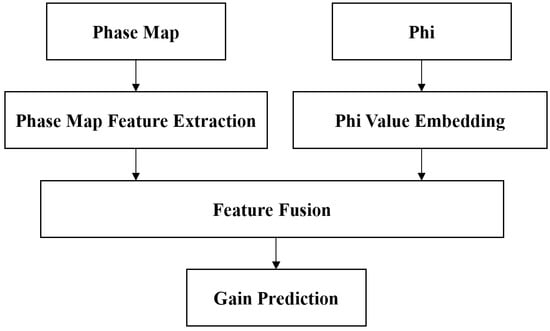

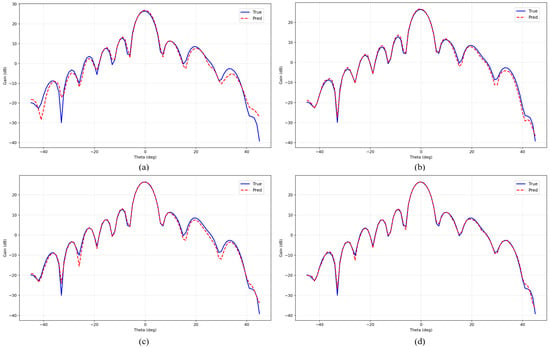

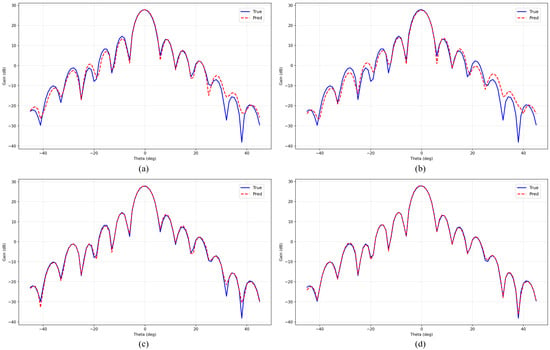

Figure 4 and Figure 5 provide detailed visual comparisons of prediction performance between PhaseNet and competing deep learning models on 1-bit and 2-bit data, respectively. Through qualitative analysis, several important insights into the models’ prediction capabilities can be derived.

Figure 4.

Comparison of predicted vs. true gain values for different models on 1-bit data: (a) TabNet; (b) Image CNN-LSTM; (c) Ski-Le-BNNl; (d) PhaseNet. The blue solid line represents the true gain values, and the red dashed line represents the predicted gain values.

Figure 5.

Comparison of predicted vs. true gain values for different models on 2-bit data: (a) TabNet; (b) Image CNN-LSTM; (c) Ski-Le-BNN; (d) PhaseNet. The blue solid line represents the true gain values, and the red dashed line represents the predicted gain values.

The prediction curve analysis confirms that PhaseNet achieves superior pattern fidelity compared to baseline models. In Figure 4, TabNet, Image CNN-LSTM, and Ski-Le-BNN show significant deviations from actual gain values, while PhaseNet’s predictions demonstrate high agreement with actual gain values across all angular positions. In Figure 5, the differences between other deep learning models’ predicted gain values and actual gain values become even more pronounced. In particular, substantial discrepancies are observed in the side-lobe regions excluding the main-lobe area.

The proposed PhaseNet in this study successfully captures both the main-lobe characteristics and complex side-lobe structures that are essential for accurate reflectarray antenna performance prediction. These results demonstrate that PhaseNet’s phi-embedding module and 2D spatial-processing approach are highly effective for antenna gain value prediction.

When the phi-embedding module was removed, all bit data exhibited an average increase of 2.00 in HPBW RMSE and over 2.07 in Main-Lobe RMSE. This finding underscores that the phi-embedding module is essential not only for encoding directional information of the radiation pattern but also for accurately capturing global pattern transitions through its interaction with the phase map. Without phi input, the model cannot learn pattern variations that are indistinguishable from the phase map alone, leading to large predictive errors across different angular regions. These results strongly suggest that phi information plays a decisive supporting role in predicting the main-lobe center angle and side-lobe distribution, and must be incorporated in antenna gain prediction models.

Next, we assessed the impact of losing spatial structure by converting the 2D phase map input into a 1D vector, and found that both HPBW RMSE and Main-Lobe RMSE increased across all bit data (1–5 bit), which indicates that losing the 2D spatial structure prevents the model from effectively learning both local and global patterns in key radiation regions, and the larger performance degradation observed in low-bit data suggests that even relatively simple phase distributions benefit critically from the spatial context provided by a 2D layout. Unlike 1D input, with 2D input, the CNN can build hierarchical feature representations through localized filtering and pooling, substantially enhancing representation capacity and generalization, and these findings strongly support that preserving the 2D layout of phase maps is indispensable when designing such models.

Finally, we evaluated the effect of removing Phase Blocks from the CNN backbone. Removing Phase Blocks 2 and 3 (leaving only Block 1) resulted in an increase of 1.73 in HPBW RMSE and 1.78 in Main-Lobe RMSE, on average across all bit data. Similarly, removing Phase Block 3 (leaving Blocks 1 and 2) led to increases of over 1.66 in HPBW RMSE and 1.76 in Main-Lobe RMSE on average. These results demonstrate that eliminating successive convolutional layers drastically impairs both low-level local feature extraction and high-level global pattern learning. Each block contributes by forming appropriate receptive fields that capture spatial patterns at multiple scales, playing a critical role in gain prediction performance. The consistent ablation outcomes across all bit settings confirm that PhaseNet’s modular architecture and multi-layer convolutional design act complementarily and are essential for learning complex patterns. This in-data analysis can serve as a practical guideline for prioritizing key components in future lightweight or variant model development.

The proposed PhaseNet adopts a proven CNN-based architecture to achieve efficient feature extraction. However, we acknowledge that more recent architectures could potentially offer higher performance. Specifically, Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) could explicitly model the mutual coupling effects between the discrete elements of the reflectarray, while Vision Transformers (ViTs) could capture long-range dependencies across the entire phase map. Future work should include a comparative analysis against these advanced models to benchmark PhaseNet’s performance in a broader context.

While conventional research methodologies required complex equations and design processes utilizing phase for each antenna type, our model offers the advantage of enabling efficient design without the need for complex numerical analysis-based computational processes. The PhaseNet model proposed in this study is an approach inspired by reflectarrays and possesses extensibility that can be applied to all array antenna types utilizing phase information. Specifically, direct application to phased arrays and transmit arrays is expected to be feasible, which will be validated in future research.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we propose PhaseNet, an end-to-end model that leverages phase maps and radiation angles as inputs. PhaseNet integrates features extracted by a CNN backbone and a radiation angle-embedding module through concatenation, followed by a regression head to predict reflectarray antenna gain values.

Furthermore, we introduce two novel evaluation metrics—Half-Power Beamwidth (HPBW) RMSE and Main-Lobe RMSE—which have not been addressed in prior work. These metrics enable a multidimensional assessment of prediction performance across the entire radiation pattern and within the critical main-lobe region, offering refined criteria for antenna design optimization. Additionally, we present a MATLAB 24.2-based method for the rapid generation of diverse bit datasets, significantly reducing the time and cost associated with data acquisition.

In future work, we plan to validate and further analyze the generalization performance of PhaseNet across a variety of antenna geometries and frequency bands, as well as investigate its applicability in practical design scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.O., S.P. and H.J.; Methodology, S.O., S.P. and H.J.; Investigation, S.O. and H.J.; Software, S.O. and S.P.; Validation, S.O. and H.J.; Writing original draft preparation, S.O., S.P. and H.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Korea Research Institute for defense Technology planning and advancement (KRIT) grant funded by the Korea government (DAPA (Defense Acquisition Program Administration)) (KRIT-CT-22-047, Space-Layer Intelligent Communication Network Laboratory, 2022). This research was supported by the research fund of Hanbat National University in 2024. This research was supported by the 2025 Hanbat National University Academic and Cultural Research Foundation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Huang, J.; Encinar, J.A. Modern Reflectarray Antennas: A Review of the Design, State-of-the-Art, and Research Challenges; IEEE Press/Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-de-Rioja, E.; Encinar, J.A.; Arrebola, M. A Review of High Gain and High Efficiency Reflectarrays for 5G Communications. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 45678–45692. [Google Scholar]

- El Misilmani, H.M.; Naous, T.; Al Khatib, S.K. A Review on the Design and Optimization of Antennas Using Machine Learning Algorithms and Techniques. Int. J. Microw.-Comput.-Aided Eng. 2020, 30, e22356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghuvanshi, A.; Sharma, A.; Awasthi, A.K.; Sharma, A.; Singhal, R.; Chong, K.S.; Lim, W.H. MAOA: A Swift and Effective Optimization Algorithm for Linear Antenna Array Design. Telecom 2025, 6, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H. SNN-Based Surrogate Modeling of Electromagnetic Force and Its Application in Maglev Vehicle Dynamics Simulation. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. 2024, 66, 1234–1245. [Google Scholar]

- Most, T.; Krenz, P.; Lampert, R. A Global Optimization Approach for Antenna Design Using Analytical Derivatives from High-Frequency Simulations. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.03674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.A.; Rahman, M.M.; Islam, M.S. Performance Improvement of THz MIMO Antenna with Graphene and Prediction Bandwidth through Machine Learning Analysis for 6G Application. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghuvanshi, A.; Sharma, A.; Awasthi, A.K.; Singhal, R.; Sharma, A.; Tiang, S.S.; Lim, W.H. Linear Antenna Array Pattern Synthesis Using Multi-Verse Optimization Algorithm. Electronics 2024, 13, 3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, K.M.M.; Sazzad, H.; Mozumdar, P.; Akter, S.; Ashique, R.H. A Comprehensive Review of AI and Machine Learning Techniques in Antenna Design Optimization and Measurement. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09393. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.M.; Islam, M.T.; Samsuzzaman, M. Machine Learning Driven Design and Optimization of a Compact Dual Port CPW-Fed UWB MIMO Antenna for Wireless Communication. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 91, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, M.A.; Rahman, M.A.; Al-Bawri, S.S.; Yusoff, Z.; Sharker, A.H.; Abdulkawi, W.M.; Zakariya, M.A. Machine Learning-Based Technique for Gain and Resonance Prediction of Mid Band 5G Yagi Antenna. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahin, K.H.; Nirob, J.H.; Taki, A.A.; Haque, M.A.; Singh, N.S.S.; Paul, L.C.; El-Latif, A.A.A. Performance Prediction and Optimization of a High-Efficiency Tessellated Diamond Fractal MIMO Antenna for Terahertz 6G Communication Using Machine Learning Approaches. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4215. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alam, M.M.; Yusof, N.A.T.; Faudzi, A.A.M.; Tomal, M.R.I.; Haque, M.E.; Rahman, M.S. Machine Learning-Based Approach for Bandwidth and Frequency Prediction of Circular SIW Antenna. J. King Saud-Univ.-Eng. Sci. 2025, 37, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koziel, S.; Pietrenko-Dabrowska, A. Deep Neural Learning Based Optimization for Automated High Performance Antenna Designs. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 89432–89445. [Google Scholar]

- Koziel, S.; Pietrenko-Dabrowska, A.; Mahrokh, M. Antenna Optimization Using Machine Learning with Reduced-Dimensionality Surrogates. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Nahin, K.H. Meta Learner-Based Optimization for Antenna Efficiency Prediction and High-Performance THz MIMO Antenna Applications. SSRN Electron. J. 2025, 27, 105882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.A.; Rahman, M.M.; Islam, M.S. Regression Machine Learning-Based Highly Efficient Dual Band MIMO Antenna Design for mm-Wave 5G Application and Gain Prediction. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1319–1334. [Google Scholar]

- Arik, S.Ö.; Pfister, T. TabNet: Attentive Interpretable Tabular Learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtually, 2–9 February 2021; Volume 35, pp. 6679–6687. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Sun, J. Antenna Modelling Based on Image-Model-Oriented CNN Exploiting LSTM. IET Microwaves Antennas Propag. 2025, 19, 1319–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Sun, J. Skip-Connected CNN Exploiting BNN Surrogate for Antenna Modelling. Int. J. Antennas Propag. 2025, 2025, 4999463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).