High-Dimensional Numerical Methods for Nonlocal Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Spatial long-range coupling: Nonlocal operators explicitly account for interactions beyond an infinitesimal neighborhood, enabling the modeling of particle transport or stress transmission across finite distances.

- Temporal memory: They provide a systematic framework to capture delayed responses of a system to its past states, which is particularly relevant for viscoelastic relaxation and anomalous diffusion processes with retardation behavior.

- Enhanced physical consistency: Nonlocal models naturally avoid stress singularities at crack tips, allow for spontaneous crack initiation and propagation, and better accommodate multiscale mechanical behavior across heterogeneous materials.

- Densification of system matrices: Spatial coupling leads to fully populated or high-bandwidth matrices, dramatically increasing memory and storage demands.

- Memory accumulation in time-fractional models: Historical convolution terms scale poorly with time steps, with per-step costs growing linearly or quadratically.

- Degraded convergence of iterative solvers: High condition numbers hinder the efficiency of Krylov subspace methods in nonlocal settings.

2. Several Typical Types of Nonlocal Problems

2.1. Anomalous Diffusion

2.2. Viscoelastic Waves

2.3. Fracture and Damage Evolution of Materials

2.4. Electromagnetic Scattering and Radiation

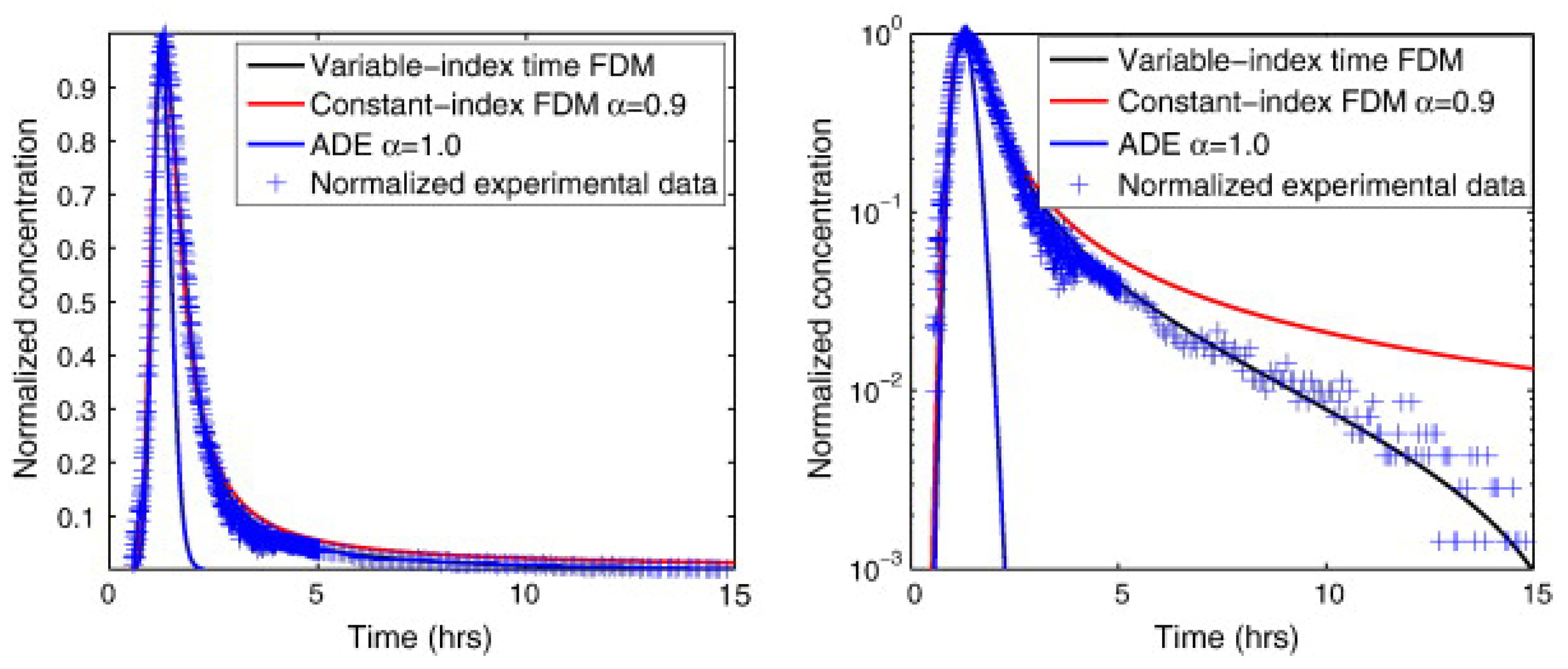

- A representative variable-order diffusion model can be expressed aswhich enables the simulation of local diffusion mechanisms in heterogeneous media that adapt to variations in position and time [68,69]. The choice of fractional orders is governed by the characteristics of the medium and the diffusion state. In general, the time-fractional order is influenced by the evolution of retention behavior across multiple scales, whereas the space-fractional order is associated with the structural non-stationarity of the medium.

3. Numerical Computation for High-Dimensional Nonlocal Models

3.1. Computational Challenges

3.2. Efficient Implementation of High-Dimensional Numerical Computation

4. Discussion

- Efficient algorithms for complex boundaries and irregular domains: Existing structured and spectral methods largely rely on regular geometry, while achieving high-order accuracy and stability under complex boundary conditions remains a bottleneck. Developing hybrid algorithms based on sparse grids, local spectral bases, and fast integration could provide a breakthrough.

- Integration mechanisms between deep learning and nonlocal operators: Future research should further explore the potential of emerging architectures like Fourier Neural Operators (FNO), Graph Neural Networks (GNN), and Transformers in approximating nonlocal kernels. FNO captures long-range correlations in the frequency domain, the GNNs are well-suited for modeling pointwise nonlocal dependencies, while the Transformer frameworks with attention mechanisms show promise for improved generalization in spatio-temporal memory operators. Complementary training strategies such as importance sampling, physics-guided regularization, hierarchical loss balancing, and multiscale Fourier embedding are also critical for enhancing network scalability and physical consistency.

- High-performance computing and heterogeneous parallelization frameworks: Given the global coupling nature of nonlocal integrals, further development of GPU/CPU co-computing, distributed storage, and communication compression strategies is needed to overcome memory constraints in high-dimensional integral computation and gradient backpropagation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CG | Conjugate Gradient |

| FADE | Fractional advection-diffusion equations |

| FDE | Fractional diffusion equations |

| FFT | Fast Fourier transform |

| GFDM | Generalized finite difference method |

| GMC-PINNs | Generalized Monte Carlo PINNs |

| GMRES | Generalized Minimal Residual |

| HDE | Hydrodynamic equation |

| KVFD | Kelvin–Voigt fractional derivative |

| nPINNs | Nonlocal physics-informed neural networks |

| PD | Peridynamics |

| PDEs | Partial differential equations |

| PVBF | Pulse vector basis functions |

| SFDE | Spatial fractional diffusion equation |

| VIE | Volume integral equation |

References

- Meerschaert, M.M.; Tadjeran, C. Finite difference approximations for fractional advection–dispersion flow equations. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2004, 172, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Chen, W.; Chen, Y. Variable-order fractional differential operators in anomalous diffusion modeling. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2009, 388, 4586–4592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Sun, H.; Zhang, X.; Korošak, D. Anomalous diffusion modeling by fractal and fractional derivatives. Comput. Math. Appl. 2010, 59, 1754–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Chang, A.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Y. Anomalous diffusion: Fractional derivative equation models and applications in environmental flows. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 2015, 45, 8–22. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Sun, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, C.; Yu, Z. Simulating multi-dimensional anomalous diffusion in nonstationary media using variable-order vector fractional-derivative models with Kansa solver. Adv. Water Resour. 2019, 133, 103423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, C.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Qian, J.; Wu, Y.; Sun, H. Fractional derivative modeling on solute non-Fickian transport in a single vertical fracture. Front. Phys. 2020, 8, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Sun, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Song, J.; Salsky, K. Hausdorff fractal derivative model to characterize transport of inorganic arsenic in porous media. Water 2020, 12, 2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.G.; Wang, Z.; Nie, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, R. Generalized finite difference method for a class of multidimensional space-fractional diffusion equations. Comput. Mech. 2021, 67, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Fu, Z.; Sun, H.; Liu, X. An efficient localized collocation solver for anomalous diffusion on surfaces. Fract. Calc. Appl. Anal. 2021, 24, 865–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, H. Generalized finite difference method with irregular mesh for a class of three-dimensional variable-order time-fractional advection-diffusion equations. Eng. Anal. Bound. Elem. 2021, 132, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, D.; Sun, H.; Zhang, Y.; Blaszczyk, T.; Yu, Z. Upscaling solute transport in rough single-fractured media with matrix diffusion using a time fractional advection-dispersion equation. J. Hydrol. 2023, 627, 130280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galucio, A.C.; Deü, J.F.; Ohayon, R. Finite element formulation of viscoelastic sandwich beams using fractional derivative operators. Comput. Mech. 2004, 33, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, O. Nonlocal effects on the dynamic analysis of a viscoelastic nanobeam using a fractional Zener model. Appl. Math. Model. 2019, 73, 637–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Lin, R.; Ng, T.Y. A fractional nonlocal time-space viscoelasticity theory and its applications in structural dynamics. Appl. Math. Model. 2020, 84, 116–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, A.; Rus, G.; Saffari, N. Wave propagation in a fractional viscoelastic tissue model: Application to transluminal procedures. Sensors 2021, 21, 2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadi, M.; Rahmanian, M. Nonlinear vibration of fractional Kelvin–Voigt viscoelastic beam on nonlinear elastic foundation. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2021, 98, 105784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

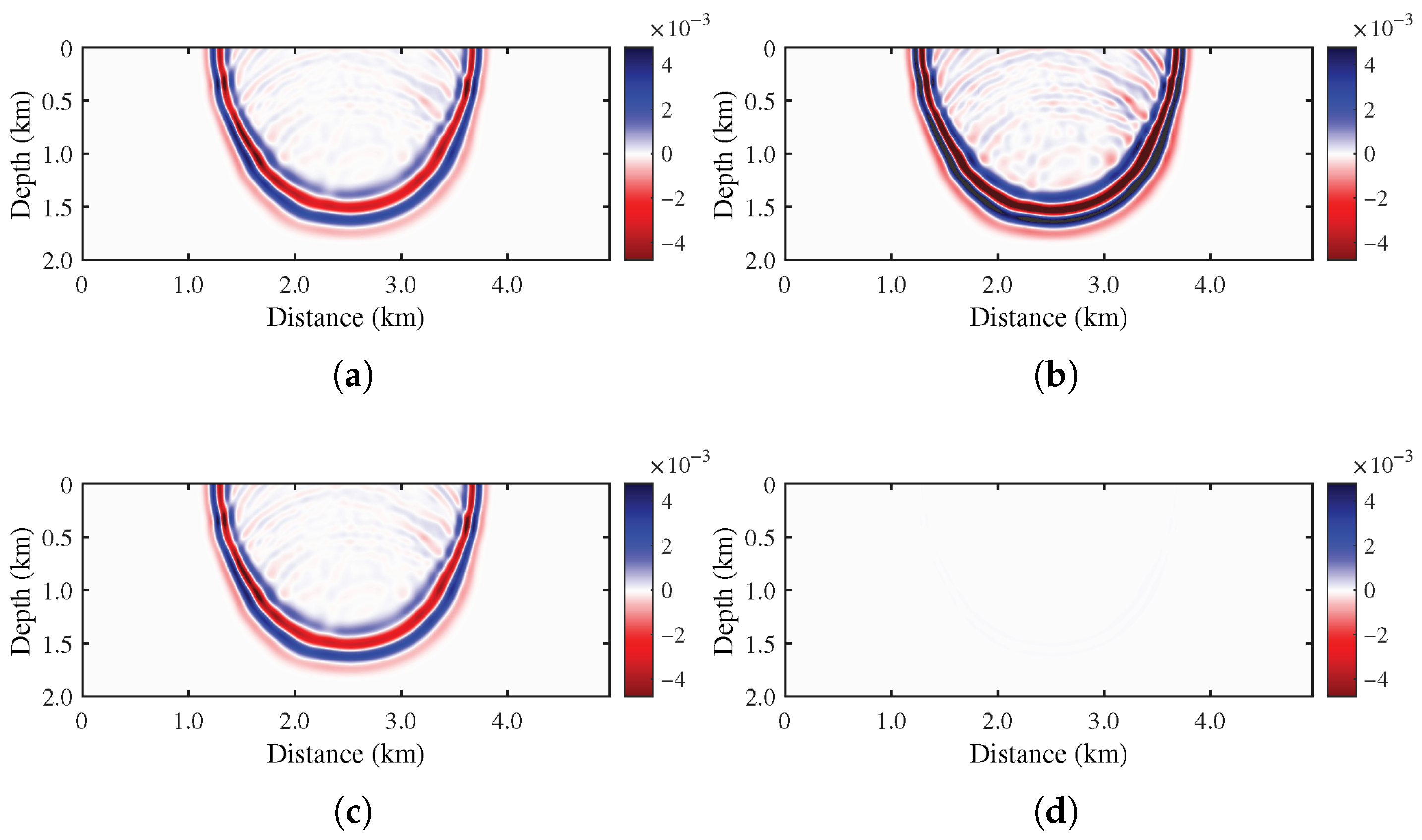

- Wang, N.; Xing, G.; Zhu, T.; Zhou, H.; Shi, Y. Propagating seismic waves in VTI attenuating media using fractional viscoelastic wave equation. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2022, 127, e2021JB023280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazhlekova, E.; Bazhlekov, I. Subordination principle for generalized fractional Zener models. Fractal Fract. 2023, 7, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, R.; Cao, L.; Zhang, Q. Study on the performance of variable-order fractional viscoelastic models to the order function parameters. Appl. Math. Model. 2023, 121, 430–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Gu, X.; Dong, Q.; Liang, J. Modified fractional-Zener model—Numerical application in modeling the behavior of asphalt mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 388, 131690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Q. Development and validation of fractional constitutive models for viscoelastic-plastic creep in time-dependent materials: Rapid experimental data fitting. Appl. Math. Model. 2024, 132, 645–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Zhou, J.; Song, D.; Cui, J.; Yuan, M.; Miao, C. The viscoelastic stress wave propagation model based on fractional derivative constitutive. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2025, 202, 105330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobasher, M.E.; Berger-Vergiat, L.; Waisman, H. Non-local formulation for transport and damage in porous media. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2017, 324, 654–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, L.; Hu, Y. A physically-based nonlocal strain gradient theory for crosslinked polymers. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2023, 245, 108094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.T.; Bui, T.Q.; Chijiwa, N.; Hirose, S. A new implicit gradient damage model based on energy limiter for brittle fracture: Theory and numerical investigation. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2023, 413, 116123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.T.; Bui, T.Q. A nonlocal gradient damage model with energy limiter for dynamic brittle fracture. Comput. Mech. 2024, 73, 831–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Feng, Y.; Ren, X. An extended gradient damage model for anisotropic fracture. Int. J. Plast. 2024, 179, 104042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Poh, L.H.; Yu, H.; Wang, Q.; Wu, H. A rigorously convergent and irreversible gradient damage model. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2025, 203, 106262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silling, S.A. Reformulation of elasticity theory for discontinuities and long-range forces. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2000, 48, 175–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silling, S.A.; Epton, M.; Weckner, O.; Xu, J.; Askari, E. Peridynamic states and constitutive modeling. J. Elast. 2007, 88, 151–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.T.; Zhou, X.P.; Kou, M.M. Three-dimensional numerical study on the failure characteristics of intermittent fissures under compressive-shear loads. Acta Geotech. 2019, 14, 1161–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.P.; Zhang, T.; Qian, Q.H. A two-dimensional ordinary state-based peridynamic model for plastic deformation based on Drucker-Prager criteria with non-associated flow rule. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2021, 146, 104857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Li, S.; Wang, X.; Yuan, C.; Li, J.; Zhang, F. Numerical simulation of crack propagation and coalescence in rock materials by the peridynamic method based on strain energy density theory. Comput. Geosci. 2022, 26, 1379–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdoh, D.A. Exploring damage and penetration in soft armors under ballistic impact through a novel and efficient 3D peridynamic model. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2025, 48, 1697–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limkatanyu, S.; Sae-Long, W.; Rungamornrat, J.; Damrongwiriyanupap, N.; Keawsawasvong, S.; Sukontasukkul, P.; Hansapinyo, C. Static Bending Analysis of Nanobeam-Substrate Medium Systems Incorporating Mixture Stress-Driven Nonlocality, Surface Energy, and Substrate-Structure Interactions. J. Appl. Comput. Mech. 2025, 11, 327–343. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Monticone, F.; Miller, O.D. All electromagnetic scattering bodies are matrix-valued oscillators. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Li, Y.; Lei, L.; Hu, J. A review on fast direct methods of surface integral equations for analysis of electromagnetic scattering from 3-D PEC objects. Electronics 2022, 11, 3753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uulu, D.A.; Chen, R.; Chen, L.; Li, P.; Bagci, H. Coupled solution of volume integral and hydrodynamic equations to analyze electromagnetic scattering from composite nanostructures. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2023, 71, 3418–3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, A.L.; Ren, B.Z.; Zhang, L.M. Solution of the volume integral equation using the revised pulse vector basis functions for electromagnetic scattering from thin homogeneous dielectric objects. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2025, 42, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, G.h.; Sun, Z.z. The finite difference approximation for a class of fractional sub-diffusion equations on a space unbounded domain. J. Comput. Phys. 2013, 236, 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Zhou, H.; Deng, W. A class of second order difference approximations for solving space fractional diffusion equations. Math. Comput. 2015, 84, 1703–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liu, F.; Jiang, X.; Turner, I.; Anh, V. A fast semi-implicit difference method for a nonlinear two-sided space-fractional diffusion equation with variable diffusivity coefficients. Appl. Math. Comput. 2015, 257, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Li, C.; Yi, Q.; Chen, A. Finite difference methods with non-uniform meshes for nonlinear fractional differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 2016, 316, 614–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Sun, Z.Z.; Zhang, J. Fast evaluation of the Caputo fractional derivative and its applications to fractional diffusion equations: A second-order scheme. Commun. Comput. Phys. 2017, 22, 1028–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Li, Y.; Zeng, T. A finite difference scheme for Caputo-Fabrizio fractional differential equations. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Model. 2020, 17, 195–211. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, F.; Li, C.; Liu, F.; Turner, I. Numerical algorithms for time-fractional subdiffusion equation with second-order accuracy. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 2015, 37, A55–A78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Bu, W.; Huang, J.; Liu, D.Y.; Tang, Y. Finite element method for two-dimensional space-fractional advection–dispersion equations. Appl. Math. Comput. 2015, 257, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Nie, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, J. Finite element methods for fractional PDEs in three dimensions. Appl. Math. Lett. 2020, 100, 106041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Li, X.; Xu, C. Finite difference/spectral approximations for the fractional cable equation. Math. Comput. 2011, 80, 1369–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Shen, J.; Wang, L.L. Generalized Jacobi functions and their applications to fractional differential equations. Math. Comput. 2016, 85, 1603–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Shen, J.; Wang, L.L. Laguerre functions and their applications to tempered fractional differential equations on infinite intervals. J. Sci. Comput. 2018, 74, 1286–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Deng, W. Fourth order accurate scheme for the space fractional diffusion equations. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 2014, 52, 1418–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Xu, C. A high order schema for the numerical solution of the fractional ordinary differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 2013, 238, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayernouri, M.; Ainsworth, M.; Karniadakis, G.E. Tempered fractional Sturm–Liouville eigenproblems. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 2015, 37, A1777–A1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Karniadakis, G.E. A spectral method (of exponential convergence) for singular solutions of the diffusion equation with general two-sided fractional derivative. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 2018, 56, 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q. Nonlocal Modeling, Analysis, and Computation: Nonlocal Modeling, Analysis, and Computation; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- D’Elia, M.; Du, Q.; Glusa, C.; Gunzburger, M.; Tian, X.; Zhou, Z. Numerical methods for nonlocal and fractional models. Acta Numer. 2020, 29, 1–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Gunzburger, M.; Lehoucq, R.B.; Zhou, K. A nonlocal vector calculus, nonlocal volume-constrained problems, and nonlocal balance laws. Math. Model. Methods Appl. Sci. 2013, 23, 493–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Reeves, D.M.; Zheng, C. Fractional-derivative models for non-Fickian transport in a single fracture and its extension. J. Hydrol. 2020, 590, 125396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Fu, C.; Guo, X. An efficient short memory algorithm for the propagation of viscoacoustic waves in heterogeneous media. Geophysics 2025, 90, F27–F41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariati, A.; Jung, D.W.; Mohammad-Sedighi, H.; Żur, K.K.; Habibi, M.; Safa, M. On the vibrations and stability of moving viscoelastic axially functionally graded nanobeams. Materials 2020, 13, 1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Shou, Y. Numerical simulation of failure of rock-like material subjected to compressive loads using improved peridynamic method. Int. J. Geomech. 2017, 17, 04016086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.; Toscano, G.; Jauho, A.P.; Wubs, M.; Mortensen, N.A. Unusual resonances in nanoplasmonic structures due to nonlocal response. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2011, 84, 121412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciracì, C.; Hill, R.; Mock, J.; Urzhumov, Y.; Fernández-Domínguez, A.; Maier, S.; Pendry, J.; Chilkoti, A.; Smith, D. Probing the ultimate limits of plasmonic enhancement. Science 2012, 337, 1072–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, T.; Yan, W.; Jauho, A.P.; Soljačić, M.; Mortensen, N.A. Quantum corrections in nanoplasmonics: Shape, scale, and material. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 118, 157402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patnaik, S.; Hollkamp, J.P.; Semperlotti, F. Applications of variable-order fractional operators: A review. Proc. R. Soc. A 2020, 476, 20190498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Chen, W.; Li, C.; Chen, Y. Fractional differential models for anomalous diffusion. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2010, 389, 2719–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.G.; Chang, A.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, W. A review on variable-order fractional differential equations: Mathematical foundations, physical models, numerical methods and applications. Fract. Calc. Appl. Anal. 2019, 22, 27–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, P.; Liu, F.; Anh, V.; Turner, I. Numerical methods for the variable-order fractional advection-diffusion equation with a nonlinear source term. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 2009, 47, 1760–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, W.; Reeves, D.M. Use of a variable-index fractional-derivative model to capture transient dispersion in heterogeneous media. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2014, 157, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atangana, A. On the stability and convergence of the time-fractional variable order telegraph equation. J. Comput. Phys. 2015, 293, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, H.; Xiao, R.; Yang, S. A variable-order fractional differential equation model of shape memory polymers. Chaos Solit. Fractals 2017, 102, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.; Lee, W.; Fung, S.W.; Nurbekyan, L. Random features for high-dimensional nonlocal mean-field games. J. Comput. Phys. 2022, 459, 111136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, G.; Del-Castillo-Negrete, D.; Cao, Y. A probabilistic scheme for semilinear nonlocal diffusion equations with volume constraints. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 2023, 61, 2718–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Shao, S.; Xiong, Y. An efficient stochastic particle method for moderately high-dimensional nonlinear PDEs. J. Comput. Phys. 2025, 527, 113818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gunzburger, M.; Ju, L. Nodal-type collocation methods for hypersingular integral equations and nonlocal diffusion problems. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2016, 299, 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, H.; Zhou, Z. A priori error analysis for time-stepping discontinuous Galerkin finite element approximation of time fractional optimal control problem. J. Sci. Comput. 2019, 80, 993–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, X. The fast scalar auxiliary variable approach with unconditional energy stability for nonlocal Cahn–Hilliard equation. Numer. Methods Partial. Differ. Equ. 2021, 37, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Lin, X.L.; Ng, M.K.; Sun, H.W. Spectral analysis for preconditioning of multi-dimensional Riesz fractional diffusion equations. Numer. Math. Theory Methods Appl. 2022, 15, 565–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Sun, H.W. A dimensional splitting exponential time differencing scheme for multidimensional fractional Allen-Cahn equations. J. Sci. Comput. 2021, 87, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Wang, H.; Zheng, X. A preconditioned fast finite element approximation to variable-order time-fractional diffusion equations in multiple space dimensions. Appl. Numer. Math. 2021, 163, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Du, N. A fast finite difference method for three-dimensional time-dependent space-fractional diffusion equations and its efficient implementation. J. Comput. Phys. 2013, 253, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Wang, H.; Cheng, A. A fast finite difference method for three-dimensional time-dependent space-fractional diffusion equations with fractional derivative boundary conditions. J. Sci. Comput. 2018, 74, 1009–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollmann, C.; Schulz, V. Exploiting multilevel Toeplitz structures in high dimensional nonlocal diffusion. Comput. Vis. Sci. 2019, 20, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Q.; Gunzburger, M.; Webster, C.G.; Zhang, G. Reduced basis methods for nonlocal diffusion problems with random input data. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2017, 317, 746–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Yuan, H.; Zhou, T. Hermite spectral collocation methods for fractional PDEs in unbounded domains. Commun. Comput. Phys. 2018, 24, 1143–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Hon, Y.c.; Stoll, M. Localized radial basis functions-based pseudo-spectral method (LRBF-PSM) for nonlocal diffusion problems. Comput. Math. Appl. 2018, 75, 1685–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, C.; Cao, D.; Shen, J. Efficient spectral methods for PDEs with spectral fractional Laplacian. J. Sci. Comput. 2021, 88, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Yan, W.; Li, C.; Mei, L. Dissipation-preserving rational spectral-Galerkin method for strongly damped nonlinear wave system involving mixed fractional Laplacians in unbounded domains. J. Sci. Comput. 2022, 93, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Fu, Y.; Cai, W.; Wang, Y. Unconditional convergence of conservative spectral Galerkin methods for the coupled fractional nonlinear Klein–Gordon–Schrödinger equations. J. Sci. Comput. 2023, 94, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, L.; Nie, Y. An Efficient Jacobi Spectral Collocation Method with Nonlocal Quadrature Rules for Multi-Dimensional Volume-Constrained Nonlocal Models. Int. J. Comput. Methods 2023, 20, 2350004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Shen, J. An efficient and accurate numerical method for the spectral fractional Laplacian equation. J. Sci. Comput. 2020, 82, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, C.; Shen, J.; Tang, T.; Wang, L.L.; Yuan, H. Fast Fourier-like mapped Chebyshev spectral-Galerkin methods for PDEs with integral fractional Laplacian in unbounded domains. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 2020, 58, 2435–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Wang, L.L.; Yuan, H.; Zhou, T. Rational spectral methods for PDEs involving fractional Laplacian in unbounded domains. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 2020, 42, A585–A611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkawy, M.A.; Soluma, E.; Al-Dayel, I.; Baleanu, D. Spectral solutions for a class of nonlinear wave equations with Riesz fractional based on Legendre collocation technique. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2023, 423, 114970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, H.; Saker, M.; Zaky, M.; Babatin, M.; Ezz-Eldien, S. Mapped Legendre-spectral method for high-dimensional multi-term time-fractional diffusion-wave equation with non-smooth solution. Comput. Appl. Math. 2025, 44, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Ni, Y.Q.; Deng, X.Y.; Hao, S. A-PINN: Auxiliary physics informed neural networks for forward and inverse problems of nonlinear integro-differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 2022, 462, 111260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Wu, H.; Yu, X.; Zhou, T. Monte Carlo fPINNs: Deep learning method for forward and inverse problems involving high dimensional fractional partial differential equations. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2022, 400, 115523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussange, V.; Becker, S.; Jentzen, A.; Kuckuck, B.; Pellissier, L. Deep learning approximations for non-local nonlinear PDEs with Neumann boundary conditions. Partial. Differ. Equ. Appl. 2023, 4, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eghbalpoor, R.; Sheidaei, A. A peridynamic-informed deep learning model for brittle damage prediction. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2024, 131, 104457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhou, X. A minimum potential energy-based nonlocal physics-informed deep learning method for solid mechanics. J. Appl. Mech. 2025, 92, 031008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, G.; D’Elia, M.; Parks, M.; Karniadakis, G.E. nPINNs: Nonlocal physics-informed neural networks for a parametrized nonlocal universal Laplacian operator. Algorithms and applications. J. Comput. Phys. 2020, 422, 109760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Qian, Y.; Shen, W. MC-nonlocal-PINNS: Handling nonlocal operators in PINNS via Monte Carlo sampling. Numer. Math. Theory Methods Appl. 2023, 16, 769–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Karniadakis, G.E. GMC-PINNs: A new general Monte Carlo PINNs method for solving fractional partial differential equations on irregular domains. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2024, 429, 117189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Du, Q. Asymptotically compatible schemes for robust discretization of parametrized problems with applications to nonlocal models. SIAM Rev. 2020, 62, 199–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Du, Q. Asymptotically compatible schemes and applications to robust discretization of nonlocal models. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 2014, 52, 1641–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Tao, Y.; Tian, X.; Yang, J. Asymptotically compatible discretization of multidimensional nonlocal diffusion models and approximation of nonlocal Green’s functions. IMA J. Numer. Anal. 2019, 39, 607–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Scott, J.; Tian, X. Asymptotically compatible schemes for nonlinear variational models via Gamma-convergence and applications to nonlocal problems. Math. Comput. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Teso, F.; Endal, J.; Jakobsen, E.R. Robust numerical methods for nonlocal (and local) equations of porous medium type. Part I: Theory. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 2019, 57, 2266–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Teso, F.; Endal, J.; Jakobsen, E.R. Robust numerical methods for nonlocal (and local) equations of porous medium type. Part II: Schemes and experiments. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 2018, 56, 3611–3647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Ni, W. The Fisher-KPP nonlocal diffusion equation with free boundary and radial symmetry in R3. Math. Eng. 2023, 5, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbar, C.; Perthame, B.; Poiatti, A.; Skrzeczkowski, J. Nonlocal Cahn–Hilliard equation with degenerate mobility: Incompressible limit and convergence to stationary states. Arch. Ration. Mech. Anazlysis 2024, 248, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Karami, B.; Shahsavari, D. On the vibration dynamics of heterogeneous panels under arbitrary boundary conditions. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 2022, 178, 103727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Ni, W. The high dimensional Fisher-KPP nonlocal diffusion equation with free boundary and radial symmetry, part 1. SIAM J. Math. Anal. 2022, 54, 3930–3973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Ni, W. The high dimensional Fisher-KPP nonlocal diffusion equation with free boundary and radial symmetry, part 2: Sharp estimates. J. Funct. Anal. 2024, 287, 110649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Applicable Scenarios | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Convolutional Dielectric Kernel | Metal nanostructures, plasmonic media | Captures longitudinal plasmon modes; explains resonance blueshift, spectral broadening, and hot-spot saturation | Requires specification of nonlocal kernels; parameterization may be model dependent and complex |

| SIE | PECs, smooth boundaries | Reduces dimensionality; efficient for large-scale scattering; satisfies radiation condition naturally | Limited to simple boundary conditions and non-dispersive media |

| VIE | Inhomogeneous dielectrics, subwavelength composites | Suitable for dielectric-metal hybrids and multilayers | High computational cost due to volumetric discretization; challenging to handle sharp resonances |

| VIE–HDE | Metal–dielectric–metal systems | Enables joint treatment of electromagnetic fields and nonlocal electron dynamics; accurately reproduces nonlocal resonances and charge spill-out effects | Computationally demanding |

| d | N | Matrix Memory | MatVec Cost per Step | Feasibility Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.51 MB | Feasible | ||

| 2 | GB | Feasible | ||

| 3 | TB | Intractable | ||

| 4 | TB | Intractable |

| Method Category | Core Strategy | Computational Complexity | Convergence/Accuracy Rates | Main Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probabilistic Methods [73,74,75] | Sampling-based estimation of nonlocal integrals | – for Monte Carlo/particle schemes; for random-feature approximations | Typical MC rate ; with variance-reduction up to ;Random feature approximation | Mesh-free, dimension-robust, naturally parallelizable; effective for integral operators and mean-field interactions | Statistical variance; slow convergence without variance reduction; requires large samples for singular kernels or strong nonlinearity |

| Structure-exploiting techniques [76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85] | Exploits block-Toeplitz/multilevel-Toeplitz matrices, FFT-based fast convolution, affine-decomposed operators for parametric reduction | per iteration for FFT-based FDM/FEM | Same numerical order as the underlying discretization | Memory-efficient, and scalable, preserves accuracy while reducing cost, interpretable | Requires regular grids and translation-invariant kernels to maintain Toeplitz structure, complex boundaries or irregular domains break efficiency |

| Spectral Methods [86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96] | Global high-order polynomial approximation | for rational or Laguerre spectral expansions; for time–space spectral schemes | Spectral (exponential) convergence for smooth or weakly singular solutions; optimal error bounds in fractional Sobolev spaces | Spectral accuracy with relatively few degrees of freedom; suitable for singular-weight or unbounded-domain problems | Dense global matrices require memory optimization; parameter tuning for mapped/rational bases |

| PINNs [97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104] | Neural approximation of solutions, trained via physics-based loss | Typically per iteration; total cost with E training epochs | for standard MC-PINNs; for MC-tfPINN with Quadrature; | Mesh-free; flexible for irregular domains; scalable to extremely high dimensions (up to 100,000 D); compatible with inverse problems and noisy data | Sensitive to neural network architecture and optimization; convergence sensitive to sampling variance; performance drops for strong singularities or complex boundary layers |

| Problem Type | Randomized Probabilistic Methods | Structure-Exploiting Methods | Spectral Methods | PINNs and Related Deep Learning Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anomalous diffusion | ***** Random trajectories (Lévy flights, subordinated Brownian motions) directly correspond to the physical process. Monte Carlo integration scales weakly with dimension and naturally captures long-range memory; efficiency is mainly limited by statistical variance. | ***** The fractional Laplacian forms translation-invariant convolution kernels. FFT-based Toeplitz solvers achieve near-linear scaling, making this class ideal for high-dimensional homogeneous media. | ***** Fractional Laplacian and variable-order operators are smooth and separable; spectral bases yield exponential convergence and efficient tensorization in moderate dimensions. | **** fPINNs and MC-tfPINNs efficiently encode fractional operators through residual losses; limited by variance in integral evaluation and spectral bias near boundaries. |

| Viscoelastic wave propagation | *** Stochastic time-marching handles hereditary effects but demands variance control and hybrid coupling to maintain temporal accuracy in oscillatory regimes. | **** If the memory kernel is spatially stationary or separable, FFT-accelerated convolution and structured Krylov methods are equally effective for handling long-memory integrals. | **** Legendre or mapped Chebyshev bases capture oscillatory yet continuous fields. Efficiency decreases for highly coupled or high-frequency regimes. | *** BO-fPINNs and MC-fPINNs approximate fractional damping accurately, but long-memory convolution causes unbalanced gradients and training stiffness. |

| Fracture and damage evolution (Peridynamics) | *** Particle-based schemes capture microcrack statistics but are costly for strong nonlinearity. | ** Crack initiation, propagation, and localization disrupt the global structural integrity of the matrix, leading to a significant decline in the efficiency of Toeplitz-type fast algorithms. | ** Fields exhibit discontinuities and topology changes; global spectral bases lose exponential convergence. | *** nPINNs can infer peridynamic parameters, and MC-Nonlocal-PINNs approximate singular kernels, but training suffers from non-smooth losses and poor convergence around crack tips. |

| Electromagnetic scattering and radiation | ** Useful for stochastic integral or kernel approximation; efficiency depends on kernel smoothness. | *** Periodic or layered structures preserve block-Toeplitz symmetry enabling FFT acceleration, whereas strongly coupled plasmonic systems break these structural advantages. | *** Fourier or rational spectral bases approximate spatial dispersion efficiently in smooth periodic media but yield dense systems in 3D complex geometries. | ** MC-Nonlocal-PINNs can approximate nonlocal dielectric kernels; oscillatory fields exacerbate training instability; hybrid PINN–BEM strategies recommended. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jia, Y.; Wang, D.; Guo, X. High-Dimensional Numerical Methods for Nonlocal Models. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3512. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13213512

Jia Y, Wang D, Guo X. High-Dimensional Numerical Methods for Nonlocal Models. Mathematics. 2025; 13(21):3512. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13213512

Chicago/Turabian StyleJia, Yujing, Dongbo Wang, and Xu Guo. 2025. "High-Dimensional Numerical Methods for Nonlocal Models" Mathematics 13, no. 21: 3512. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13213512

APA StyleJia, Y., Wang, D., & Guo, X. (2025). High-Dimensional Numerical Methods for Nonlocal Models. Mathematics, 13(21), 3512. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13213512