Abstract

Environmental concerns and the increasing scarcity of resources force decision makers in the supply chain to consider reuse and re-production. Closed loop supply chain is a fundamental concept that has attracted the attention of many researchers due to its profitability for businesses as well as its positive environmental and social effects. Closed-loop supply chains and sustainability dimensions are complementary because of their mutual effects. This paper develops a mathematical model to design a sustainable closed-loop supply chain network in the wood–plastic composite industry. Due to the nature of the problem considered, a mixed-integer linear programming method is utilized. The proposed model is a multi-objective model, and the Lp-metric method is used to solve it. The proposed model is applied in a real case in Iran. The proposed model identified 17 optimal provinces for manufacturing centers, 15 for reuse centers, and 9 for reproduction centers. Verification and validation of the proposed model illustrate its capability in real world implications.

Keywords:

closed-loop supply chain; sustainability; circular economy; optimization; wooden-plastic composite MSC:

90C29; 90C11; 90C05; 80M50; 83C15

1. Introduction

In recent years, the concept of the circular economy (CE) has gained significant attention as a transformative approach to sustainable development. The primary objective of CE is to achieve a more harmonious equilibrium between the economy, environment, and society by promoting the efficient utilization of resources [1]. The central goal of CE is to “close” or “reduce or narrow” the loops of resource use. “Closing” these loops involves recycling materials by reusing post-consumer waste, while “reducing or narrowing” loops focuses on extending the use and reuse of materials over time by designing products to be durable and long-lasting [2]. In light of evident social and environmental challenges, ensuring sustainable development within supply chains (SC) has emerged as a crucial concern [3]. Sustainable development typically entails environmental preservation, economic prosperity, and social accountability [4]. Originally, SC networks were configured with a sole focus on economic factors. However, as awareness of environmental and social impacts has grown, traditional networks have gradually transitioned toward sustainable SCs [5].

To reduce waste and improve resource efficiency, many developing nations have adopted strategies for recovering and repurposing materials. The processes of material recovery and reuse have created an additional channel for material transfer within SCs, leading to the emergence of closed-loop supply chains (CLSCs) [6]. CLSCs integrate forward and reverse logistics, combining production and distribution with processes such as collection, recycling, and reproduction, thereby achieving sustainability goals [7,8]. In a sustainable CLSC, consumer needs are met while reverse logistics is responsible for managing end-of-use and end-of-life goods, minimizing environmental damage [9]. Traditional SCs, often referred to as forward SCs, were primarily designed to minimize total costs across suppliers, manufacturers, transporters, warehouses, retailers, and customers. However, over time, their scope expanded to include environmental and social aspects as well. In reverse logistics, additional activities such as recycling, repair, and reconstruction were introduced to handle end-of-life products, which further supported the development of CLSCs [10,11,12].

Beyond the general importance of CLSCs, specific industries highlight the urgent need for sustainable solutions. Excessive deforestation has accelerated the extinction of species and reduced oxygen reserves worldwide. One effective way to address this issue is through the creation of composite wood, a material derived from broad-leaved debris and polymeric components. This innovative material, known as wood–plastic composite (WPC), is eco-friendly and replicates the appearance and strength of rare wood species while offering corrosion resistance, fire resistance, and durability. By using recycled plastics and wood residues, WPCs help mitigate the deforestation pressures associated with traditional wood-based products and drastically reduce the demand for virgin timber. Furthermore, WPC products are fully recyclable and can be used as raw materials for new WPC production, making them highly compatible with CLSC networks [13]. The design of CLSC networks in this industry therefore simultaneously improves commercial viability and lowers overall costs while supporting sustainability goals.

Global population growth and the extensive use of fossil fuels have pushed ecosystems beyond their natural capacity, triggering climate, economic, and social problems. As a response, governments have supported green energy initiatives, organic products, and sustainable wood alternatives in line with international agreements such as the Paris–Kyoto accords. Consequently, global demand for wood and wood by-products has rapidly increased, intensifying competition and driving research into sustainable alternatives [14,15]. In this regard, WPC has emerged as an innovative solution. The forest industry now faces the challenge of producing and recycling wood resources in ways that are both efficient and cost-effective, while also satisfying consumer demands [16]. Researchers worldwide are exploring alternatives to natural wood, and WPC has been recognized as one of the most promising options, given its recyclability and environmental benefits [13].

The critical role of CLSCs in promoting sustainability and resource efficiency across various industries—including the WPC sector—has attracted extensive scholarly attention.

A substantial body of research has focused on modeling CLSCs under uncertainty in parameters such as demand, recovery rates, and returns. For example, Elfarouk et al. [17] developed a mathematical model addressing uncertainty in both demand and recovery processes to minimize costs and environmental impacts while maximizing employment opportunities. Similarly, Zhen et al. [9] proposed a stochastic dual-objective CLSC model balancing costs and emissions, whereas Talaei et al. [18] explored uncertainty in electronic supply chains to design more resilient and sustainable systems. These studies collectively emphasize the importance of robust modeling frameworks capable of handling real-world variability in CLSC operations.

Another major line of research in CLSC design emphasizes multi-objective sustainability integration and industry-specific applications, recognizing that real-world systems must balance economic, environmental, and social goals under diverse industrial contexts. Scholars have increasingly developed models that extend beyond cost minimization to capture the broader sustainability performance of supply chains.

For instance, Sarkar and Bhuniya [19] proposed a production–reproduction system incorporating flexible demand and environmentally responsible processes. Abdolazimi et al. [20] introduced a three-objective CLSC model for the tire industry that minimized costs and environmental damage while optimizing delivery time. Similarly, Salehi-Amiri et al. [21,22] examined agricultural supply chains (avocado and walnut), demonstrating how CLSC configurations can enhance social outcomes such as employment alongside economic efficiency. Expanding the methodological frontier, Rouhani et al. [23] utilized hexagonal fuzzy numbers to construct a tri-objective model (cost, environmental impact, and social benefit) under demand and return uncertainties in the apparel sector, revealing the greater sustainability leverage of end-of-life and commercial returns compared to end-of-use returns.

Further enriching this stream, Rahmani et al. [24] incorporated market competition and governmental incentives into a bilevel CLSC framework, showing how policy mechanisms can promote cleaner technologies and influence facility placement decisions. Similarly, Ramyar et al. [25] and Rezaei and Kheirkhah [26] developed multi-objective models integrating production planning and efficiency–sustainability trade-offs, while Özkır and Baslıgil [27] and Chaabane et al. [28] optimized facility location and incorporated life cycle assessment to assess environmental performance across supply chain stages.

Context-specific investigations have also emerged, revealing the diversity of challenges faced by different industries. For example, Doustmohammadi and Babazadeh [14] examined direct and reverse flows in the WPC sector, but their model addressed only economic factors, leaving environmental and social dimensions unexplored. Likewise, Nayeri et al. [8] proposed a sustainable CLSC for water tanker logistics, broadening the industrial applicability of such frameworks.

All of these studies show that there is a growing trend toward multi-objective, integrated CLSC designs that can be tailored to the unique requirements of particular industrial contexts [29]. Even so, there are still very few comprehensive models that concurrently address the economic, environmental, and social pillars of sustainability within industry-specific frameworks like WPC, despite significant advancements. Despite these developments, the majority of earlier studies have mostly concentrated on environmental or cost optimization, frequently ignoring the social aspect and useful spatial integration. Furthermore, not many studies have taken into account multi-product and multi-period planning within a single sustainability framework. In order to improve CLSC design, this research gap emphasizes the necessity of context-aware, multi-objective optimization techniques that integrate spatial realism, circular economic principles, and thorough sustainability integration.

This study focuses on the WPC industry and develops a deterministic multi-objective mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) model to design a sustainable CLSC network. The model simultaneously minimizes total cost and maximizes employment opportunities and environmental performance, addressing all three pillars of sustainability—economic, social, and environmental. Using Iran as a case study—where arid and semi-arid climatic conditions make deforestation a critical issue—WPC production is actively supported by governmental and industrial stakeholders. The proposed model integrates facility location, reuse, and reproduction decisions across 31 provinces, ensuring practical applicability to real-world contexts. In contrast to studies such as [30], which emphasize stochastic demand and logistics optimization through fourth-party logistics (4PL) in the electronics sector, this research provides a holistic framework for sustainability integration within the WPC industry—a sector rarely explored in CLSC studies. Indeed, most prior models in the literature focus predominantly on economic factors, with limited consideration of environmental and social aspects. Moreover, despite the high recycling and sustainability potential of WPC products, only one previous study has examined CLSC design in this industry, and it focused solely on economic objectives [14]. Hence, the present study fills this gap by offering a comprehensive, multi-objective framework that aligns with real-world sustainability goals.

The remaining part of the paper is arranged as follows. A MILP model is created in Section 2 to define and formulate the problem and describe the multi-objective solution approach. The results of the case study and application are explained in Section 3. Section 4 provides a comprehensive interpretation of the outcomes to be used by stakeholders and Section 5 summarizes the study with key implications and future research directions.

2. Materials and Methods

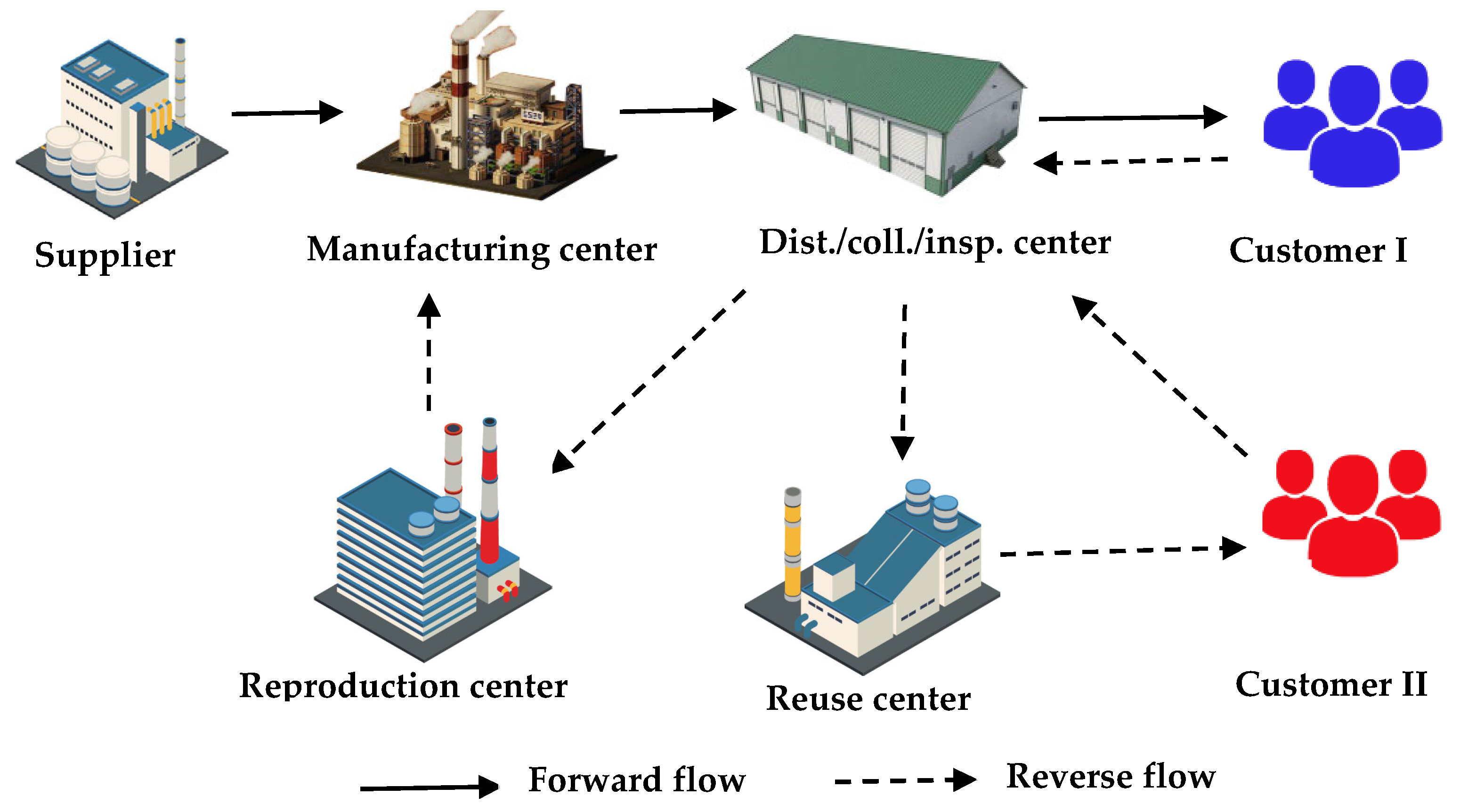

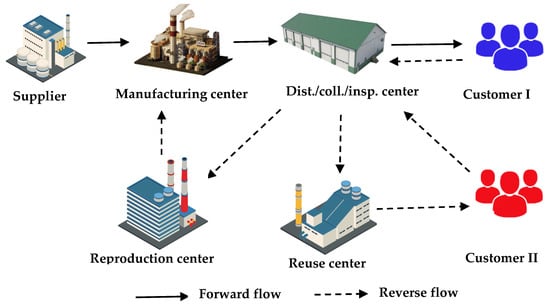

The proposed model for designing CLSC network in the WPC industry is presented as multi-product, multi-period, and multi-objective as presented in Figure 1. The solid lines depicted in the diagram signify the movement of materials and products in a forward direction, while the dashed lines represent the reverse flow of materials. This reverse flow is primarily for collection, inspection, and eventually recycling or reusing in the production process. A case study has been implemented in the WPC door and window production industry to demonstrate the application of the proposed model. This research presents a MILP model for a CLSC network. It consists of the supplier, manufacturer, distribution-collection, and inspection center, re-production center and re-use center, and first and second groups of customers.

Figure 1.

The layout of the investigated CLSC network.

The analyzed CLSC in the WPC industry involves the procurement of raw materials from suppliers and their transformation into final products at manufacturing centers. It is common to encounter waste during the conversion process from raw materials to final products, which is not an exception in this context. However, the advantage of this production approach, specifically for WPC products, lies in the ability to reintroduce all the waste generated during production back into the production cycle as raw material. Products manufactured in the factories are transported to distribution–collection–inspection centers and then delivered to various regions according to customer demand.

It is important to note that this particular customer segment seeks brand-new products (referred to as the first group of customers). Additionally, used products are acquired and collected from customers and then transported to the distribution–collection–inspection centers. It is also possible that other WPC products may be received from customers. After undergoing inspection, the collected products are categorized into two groups: those suitable for reuse and those suitable for reproduction. Each group is then sent to the respective centers. In the reuse center, the used products are transformed into usable items through minor modifications and alterations, catering to customers who are interested in this type of product (the second group of customers). The products deemed suitable for re-production, following inspection, are converted into raw materials and dispatched to manufacturing centers.

The crucial strategic choices covered by the suggested model are the positioning of facilities at various CLSC network levels. Additionally, it covers tactical decisions such as optimizing purchase quantities, production, transportation, and raw material collection. The strategic and tactical aspects of facility placement decisions are categorized in this study. Since it takes a lot of money and time to set up manufacturing and re-production centers, these facilities are represented as time-independent decisions and are presumed to stay the same throughout the planning horizon. On the other hand, distribution–collection–inspection centers might be modified over time in reaction to shifts in logistics or demand. Their opening choices are therefore regarded as time-dependent, enabling the model to decide whether these facilities should stay open, move, or close during each period. The decision-making process in the CLSC network is more adaptable and realistically represented by this mixed temporal structure.

The following are the primary presumptions taken into account when constructing the mathematical model:

- Assuming full knowledge and consistent operational conditions over the course of the planning horizon, all model parameters are regarded as deterministic.

- For simplicity and cost uniformity, a single mode of transportation is used across the SC.

- Every facility at every level of hierarchy functions within capacity restrictions, which mirror actual production and storage limitations.

- Four seasonal periods, each of which represents a different pattern of supply and demand, make up the planning horizon.

- The many raw materials needed for the creation of WPC, particularly wood flour and polymer compounds, can be supplied by each provider.

- WPC doors and WPC windows are the two product kinds that manufacturing facilities are presumed to produce.

- Customers who buy first-hand (new) and second-hand (reused) products are the two client segments taken into account by the model.

- Based on provincial population statistics, which represent the potential of the regional market, customer demand is estimated.

- All client demands for new products must be met within each period; shortages are not allowed. However, the reused products are sent to customers in a push system and shortage is possible.

- Delivering new products to first-hand customers, collecting returned goods from all customers, and examining these goods to decide whether to send them to reuse or re-production facilities are the responsibilities of distribution–collection and inspection centers.

- In order to recover raw materials for manufacturing centers, remanufacturing units, also known as re-production centers, are responsible for the shredding and processing of collected items.

- To make it possible for things to be sold again on the second-hand market, reuse centers make small repairs or adjustments.

- Quality testing is carried out at inspection centers, and the related inspection costs are part of the centers’ operating costs.

The proposed MILP model:

The objective function (1) aims to minimize the overall cost of the SC, encompassing: fixed cost of opening manufacturing, distribution–collection–inspection, reuse and re-production centers, cost of purchasing raw materials from the supplier, cost of production, cost of separating collected products in distribution–collection–inspection centers, cost of purchasing used products from first and second group of customers, inspection cost of collected products from customers in distribution–collection and inspection centers, re-production and reuse cost of returned products and transfer cost of raw materials from remanufacturing centers to manufacturing centers and transfer products in forward and backward flow.

The objective function (2) aims to maximize the employment rate. Specifically, this objective function seeks to maximize the ratio of employment resulting from the establishment of a center to the total unemployment rate in those areas. This objective function consists of two components: the ratio of employed individuals to the total unemployed in the region, and the ratio of products manufactured in a center to the total demand, indicating the center’s contribution to meeting the demand rate. Opening centers with higher involvement in meeting the demand will lead to increased employment opportunities in that location [19,20].

The objective function (3) is maximizing the green impact of this SC, which depend on the green level of constructing manufacturing, distribution–collection and inspection, reuse and re-production center, purchasing raw materials from the supplier, producing goods, separating collected products in distribution–collection and inspection centers, purchasing used products from the first and second group of customers, inspecting products collected from customers in the distribution–collection and inspection centers, reuse and re-production of returned products and transfer of raw materials from re-production centers to the manufacturing centers and the transfer of products in forward and backward flow. This objective function is framed as maximization since it reflects the SC’s green performance rather than environmental harm. The CLSC network’s ecological performance is improved when this goal is maximized since it rewards eco-friendly choices including increased recycling rates, less waste, and increased usage of green materials. Based on metrics like energy consumption, emission reduction, and waste recovery, the green impact index evaluates how well each of the following activities performed environmentally: production, reuse, reproduction, and transportation. The Department of Environment of Iran (2023), life-cycle assessment studies, and industrial environmental reports were the sources of the coefficients. Higher scores denote greater environmental benefits, and all green impact values were linearly normalized to the [0, 1] range.

Constraint (4) specifies that the quantity of products with a specific level of greenness, transported from manufacturing centers to distribution–collection–inspection centers, must be equal to the quantity of products transported from the distribution center to the first group of customers, within each time period.

Constraint (5) shows that the amount of goods with a certain level of greenness carried from distribution-collection-inspection centers to the first group customers must be equal to the demand of the first group of customers in each period. Notably, the SC goal is to meet the demand of first customers fully in a pull system and responds to second market as possible as in a push system. Therefore, the balance equation of demand for the second customer is not necessary in the SC.

Constraint (6) indicates that the quantity of returned products from the first group of customers to the collection center is a proportion of the total demand.

Constraint (7) makes sure that the amount of products transported from manufacturing centers to distribution, collection, and inspection centers during each time period is balanced with the amount of raw materials available at these centers with a specific green level.

Constraint (8) illustrates the equilibrium between the returned raw materials with a specific green level from re-production centers to manufacturing centers, within each time period, and the quantity of products transported from distribution, collection, and inspection centers to the re-production centers.

In order to guarantee that both returned goods and newly manufactured products are kept within their respective capacity bounds, constraints (9) and (10) specify the distribution, collection, and inspection centers’ storage capacity limitations. These limitations preserve operational viability and stop the network’s storage resources from being overused.

Constraint (11) ensures that output does not surpass available capacity by defining the production capacity limits of manufacturing centers for newly produced items. The flow of returned goods through recovery procedures is controlled by constraints (12) and (13) that specify the operational capabilities of reuse and re-production centers, respectively. Additionally, a facility’s associated binary decision variable takes on a value of zero if it is not established, deactivating its capacity and stopping the flow of any materials or products through it.

Constraints (14) states that the quantity of goods with a specific green level transported from re-use centers to customer areas must be equal to the quantity of goods with the same green level transported from distribution centers to the reuse centers.

Constraints (15) and (16) indicate that the quantity of goods transported from distribution-collection-inspection centers to reuse centers (or re-production centers) with a specific green level is equal to the product of the ratio of goods transferred from distribution-collection-inspection centers to reuse centers (or re-production centers) and the total quantity of goods returned from customers to collection centers in each time period.

Constraints (17) and (18) account for the non-negativity and binary conditions imposed on the decision variables.

Multi-Objective Solution Approach

The suggested model in this research study is presented as a multi-objective model, so we used the Lp-Metric method to solve the model, which is one of the techniques for solving multi-objective models. Because the Lp-metric approach offers a flexible and balanced mechanism for integrating multiple conflicting objectives without requiring pre-defined trade-off priorities, it was chosen. The ε-constraint method necessitates iterative optimization and separate runs for every objective, whereas the Lp-metric approach provides computational efficiency and simplicity of use in a single optimization run. For large-scale MILP models, like the sustainable closed-loop supply chain this study looks at, it is especially appropriate. In this method, the sum of the relative deviations of the goals from their optimal values tends to be minimized, so:

In the above expression, p is the metric parameter which indicates the degree of emphasis on deviations (typically 1, 2, or ∞), the value of which is considered as 1. is the weight considered for each of the objectives, which in this problem, the objectives are assumed to have the same weight. Zi stands for each objective function.

The algorithmic procedure of the solution method is as follows.

- Input data for all deterministic parameters, costs, capacities, and demand values.

- Solve each objective function individually and obtain the optimal values for each objective function (determine ideal values , , )

- To guarantee comparability, normalize each objective by its ideal value.

- To create a single composite function, integrate objective functions using the Lp-Metric formulation.

- To find the compromise solution that minimizes overall deviation, perform optimization in GAMS 25.1/CPLEX 22.1.

- To evaluate the stability of the model, conduct a sensitivity analysis of important parameters (such as demand).

- Provide the ideal facility locations, flow rates, and objective values.

3. Results

The computational results of the proposed multi-objective MILP model, solved using the Lp-Metric approach, are presented in this section. The CPLEX 22.1 solver was used to implement the suggested multi-objective MILP model in GAMS 42.2. The network’s multi-product, multi-period, and multi-facility structure was reflected in the full-scale case study’s roughly 18,700 continuous variables, 1240 binary decision variables, and 9600 constraints. All other parameters were set to the default CPLEX settings, and the optimality tolerance (MIP gap) of the solver was set to zero. On a system with an Intel Core i7 processor and 16 GB of RAM (Intel, Santa Clara, CA, USA), the model reached convergence in an average runtime of 2460 s (approximately 41 min). These findings validate the model’s computational tractability and scalability for practical closed-loop supply chain applications with a variety of sustainability goals.

The solution procedure began with determining the optimal values of each objective function individually. These values were then integrated using the Lp-Metric aggregation method to obtain a compromise solution. The model’s computational feasibility was confirmed by the reasonable average computation time, recorded on a system equipped with an Intel Core i7 processor and 16 GB of RAM.

The results presented in this section illustrate the optimal facility locations, material and product flows, and the trade-offs achieved among the economic, social, and environmental objectives.

3.1. Case Study Results

This study evaluates all 31 provinces of Iran to identify the optimal locations for manufacturing centers, distribution–collection–inspection centers, reuse centers, and reproduction centers within a CLSC network. The proposed model integrates three key dimensions of sustainable development—production requirements, raw material availability, and transportation logistics—with the objective of minimizing total supply chain costs, maximizing employment opportunities, and enhancing the green performance of the network.

The data utilized in this study were obtained from statistical yearbooks, feasibility studies, and industrial reports related to Iran’s WPC industry. Major data sources included the Statistical Center of Iran, the Ministry of Industry, Mine, and Trade, and provincial development reports covering the 2020–2023 period. These sources provided essential information such as transportation distances, facility establishment costs, capacity levels, and regional labor statistics. Additionally, per capita housing data and provincial population figures were used to estimate the regional demand for WPC products. Due to space limitations, all data are provided in Supplementary Materials.

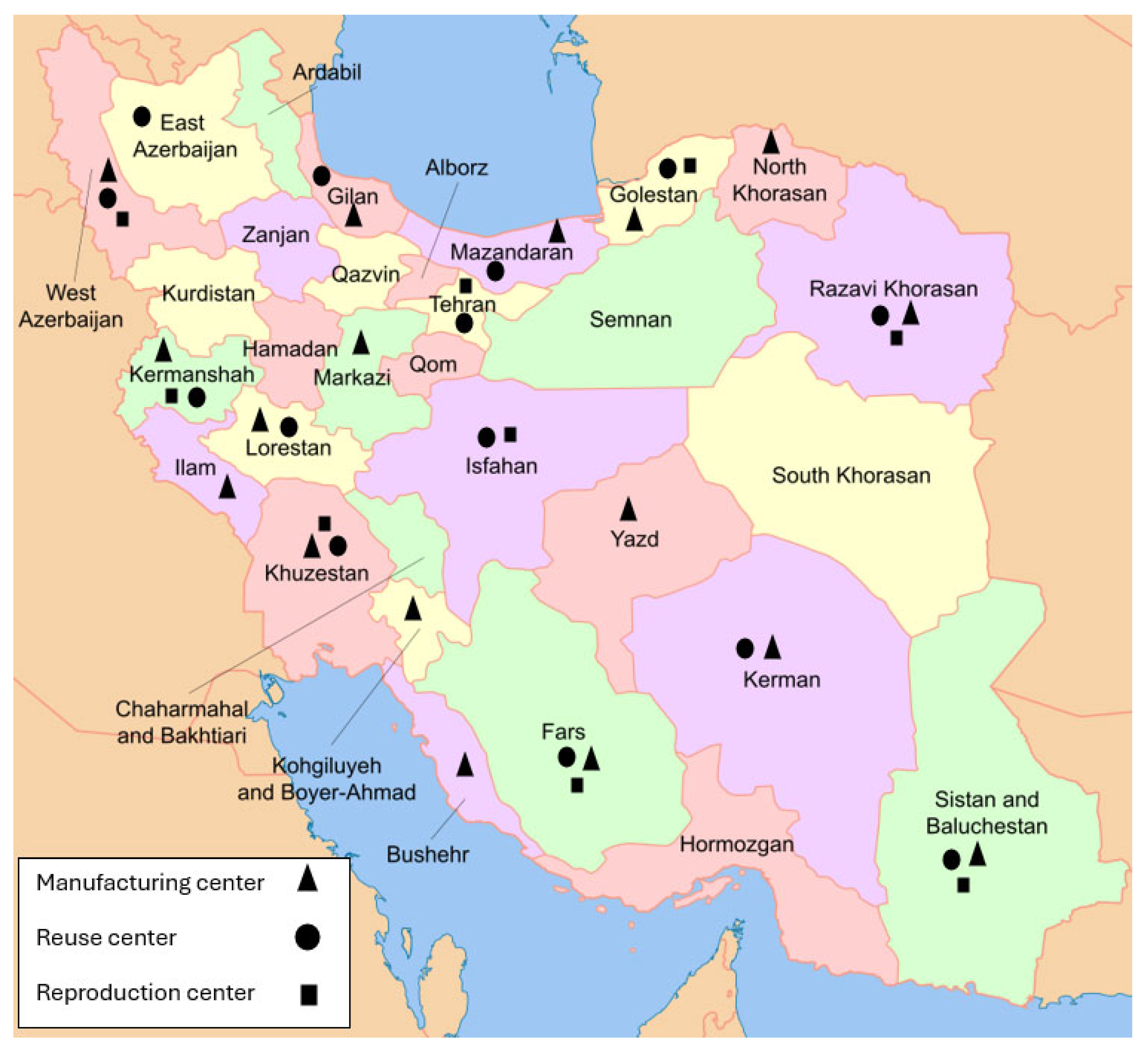

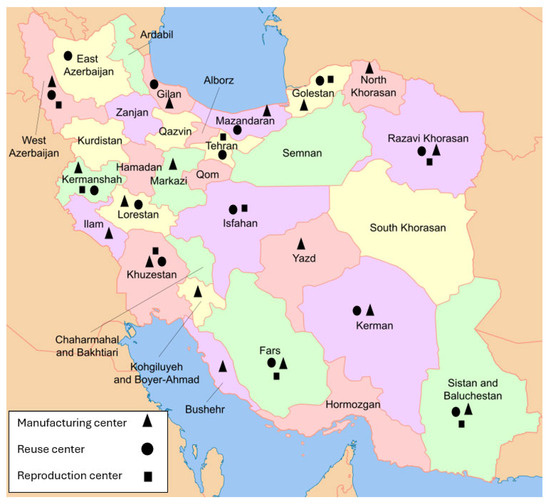

The model results reveal that 17 provinces are optimal for establishing manufacturing centers, 15 provinces for reuse centers, and 9 provinces for reproduction centers. These findings—summarized in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3—offer a practical framework for strategic facility location decisions in the WPC sector. Table 4 presents the optimal values of the objective functions, illustrating the trade-offs among cost efficiency, employment generation, and environmental performance.

Table 1.

The Best Locations for Manufacturing, Reuse, Reproduction centers.

Table 2.

Optimal values of objective functions.

Table 3.

Production Rate at the manufacturing center of West Azerbaijan (Product/period).

Table 4.

The Amount of Raw Material send to manufacturing center of West Azerbaijan from suppliers (Tons).

Table 1 illustrates the best locations selected for establishing manufacturing, reuse and reproduction centers. Total of 17 provinces have been identified as ideal for manufacturing activities. These locations likely offer the necessary infrastructure, access to raw materials, skilled labor, and logistical advantages crucial for manufacturing operations.

The optimum values for the objective functions are presented in Table 2. The computational viability of the model was confirmed by the average computation time of 2460 s (approximately 41 min) for the entire model. As mentioned in previous section, we aimed to solve a multi-objective problem with three objective functions. The first objective function (Z1) minimized the costs of the entire SC, with an optimum value of 3.27025 × 1013 (IRR). The second objective function (Z2) maximized the employment rate, yielding a maximum value of 37.433. The third objective function (Z3) maximized the greenness of the SC, considering green impacts, with an obtained value of 5.13215 × 107. The weights assigned for objective functions economic, green performance and job creation are the same.

Figure 2 shows the established manufacturing center (y1) and reuse center (x1) and re-production center (x2) in different provinces. All 31 candidate locations were selected for opening the distribution-collection and inspection center (y2), For this reason, it was omitted to display in Figure 2. As it shown in Figure 2, based on the considerable demand in West Azerbaijan, Kermanshah, Razavi Khorasan, Khuzestan, Sistan and Baluchistan, Fars and the provinces around them, it is optimal to build all 3 centers in these locations.

Figure 2.

Locations for opening manufacturing center (y1) & reuse center (x1) & re-production center (x2).

Considering that the central and western regions of Iran are industrial, it is more possible to establish production centers in these provinces, which is consistent with the results of this research.

The production rates at the manufacturing center in West Azerbaijan were analyzed, focusing on the relationship between different products, their green levels, the manufacturing centers, and the distribution–collection–inspection centers. The results are summarized in Table 3.

The data, as presented in Table 3, demonstrate significant variability depending on the specific distribution-collection-inspection center involved. For instance, when analyzing the combination of p = 1, n = 1, and i = 2, the production rates at center j = 2 were particularly high, with periods t1 and t2 recorded at 43,668 and 18,396 units, respectively. However, the absence of recorded production for t3 and t4 in this context suggests that this center may either specialize in certain production stages or encounter bottlenecks that limit its output in other areas. Moreover, the data indicates a degree of consistency in production at specific green levels. For example, with p = 1, n = 1, i = 2, and j = 7, the production rates for t1 and t2 were both 18,252 units, pointing to an efficient process at this green level within this particular center. Yet, similar to the previous example, there was no recorded data for periods t3 and t4, which could imply that these processes are either unnecessary or not operational for this product configuration.

The manufacturing center indexed by i = 2 emerges as a significant hub within the production network, consistently showing substantial production rates across various product and green level combinations. This consistency underscores the importance of this center in the overall production strategy in West Azerbaijan and suggests that it plays a pivotal role in meeting production targets.

Table 4 represents the amount of raw material, measured in tons, that was sent from various suppliers to the manufacturing center in West Azerbaijan. The data is categorized by different factors: the type of raw material (f), the green level of the raw material (n), the supplier (s), and the specific manufacturing center (i). The columns under t1, t2, t3, and t4 represent the quantities of raw materials sent to the manufacturing center across four different time periods or stages.

The table shows that raw material f = 1 with a green level of n = 1, supplied by supplier s = 2, was sent to manufacturing center i = 2 in substantial quantities. Specifically, 114,307 tons were sent during the first time period (t1), followed by similar amounts of 114,124 tons in t2, 46,213 tons in t3, and 81,662 tons in t4. This indicates a consistent and significant flow of this material from this supplier to the manufacturing center. For the same raw material f = 1 but with a green level of n = 2, the amounts sent by supplier s = 2 to the same manufacturing center were lower, with 42,611 tons sent during t1 and 33,722 tons during t2. No raw material was recorded in t3 and t4, which could suggest that either the supply was limited to the earlier stages or there was a shift in the SC strategy. For raw material f = 2, with a green level of n = 1, and supplied by s = 14, the manufacturing center received substantial quantities as well: 113,995 tons each in t1 and t2, 53,936 tons in t3, and 76,967 tons in t4. Similarly, for the same material but with a green level of n = 2, the quantities were 55,989 tons in t1, 46,071 tons in t2, 28,408 tons in t3, and 28,896 tons in t4. These figures suggest that supplier s = 14 consistently provided significant amounts of raw material, particularly in the earlier stages, with a noticeable decrease as the stages progressed.

Table 5 provides detailed data on the amount of raw material, measured in tons, sent to the manufacturing center in West Azerbaijan from various re-production centers. The table categorizes the data based on the type of raw material (f), the green level of the material (n), the re-production center (c), and the specific manufacturing center (i). The columns under t1, t2, t3, and t4 represent the quantities of raw materials sent during different time periods or stages.

Table 5.

The Amount of Raw Material send to manufacturing center of West Azerbaijan from Re-production center (Tons).

The data shows that for raw material f = 1 with a green level of n = 1, re-production center c = 2 sent 1878 tons during t1, 1970 tons during t2, 226 tons during t3, and 427 tons during t4 to the manufacturing center i = 2. This indicates a decreasing trend in the supply of raw material over time from this particular re-production center. Similarly, re-production center c = 11 sent 4213 tons in t1 and 4305 tons in t2, but no raw material was sent during t3 and t4, suggesting that supply was limited to earlier stages. For green level n = 2, the data shows more variability across different re-production centers. For instance, re-production center c = 8 sent no raw material during t1 and t2, but a significant amount of 24,665 tons was sent in both t3 and t4, indicating a delayed but substantial supply in later stages. In contrast, center c = 11 sent material consistently across all stages, with 4864 tons in t1, 6803 tons in t2, 4814 tons in t3, and a much smaller amount of 102 tons in t4.

For raw material f = 2 with a green level of n = 1, the amounts sent were relatively small, with only 67 tons sent by center c = 8 during t1 and t2, and no material sent in the later stages. Interestingly, center c = 11 sent no material during the first three stages but delivered 802 tons during t4, which is a notable shift in supply timing. For green level n = 2, the supply from center c = 4 included 9707 tons in t3 and 7321 tons in t4, while center c = 13 showed a similar delayed supply pattern, delivering 872 tons in t3 and 2468 tons in t4.

3.2. Sensitivity Analysis

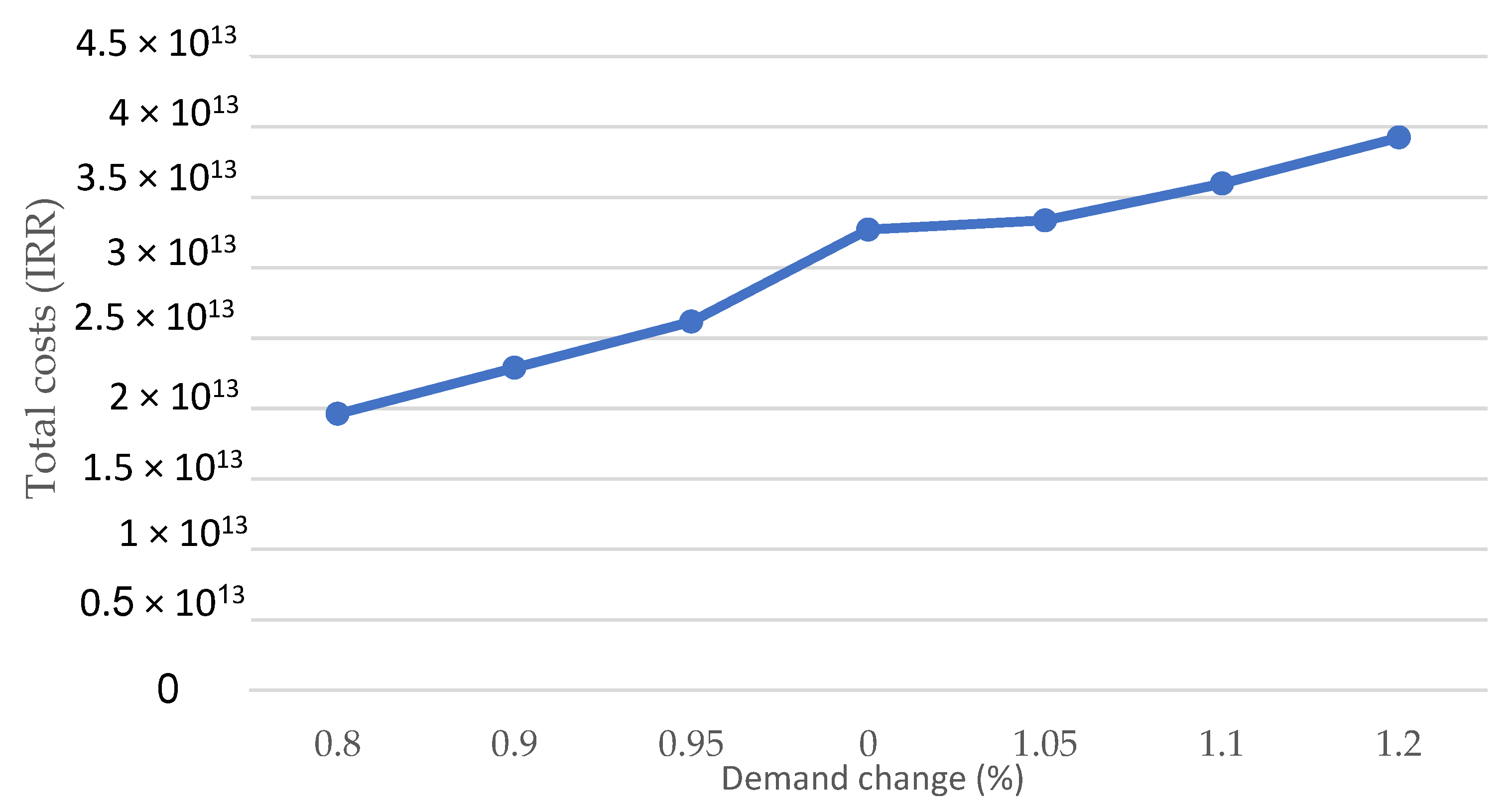

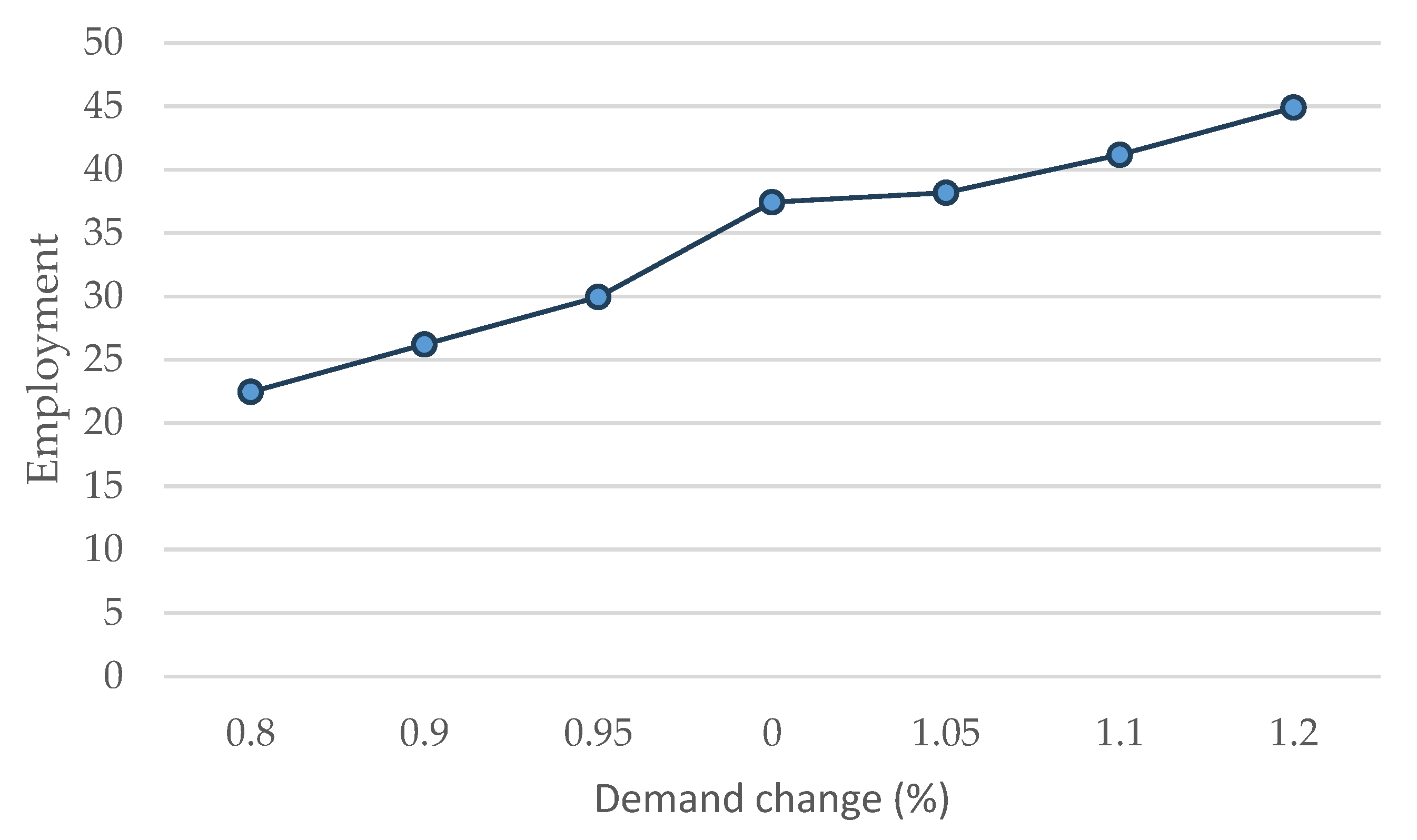

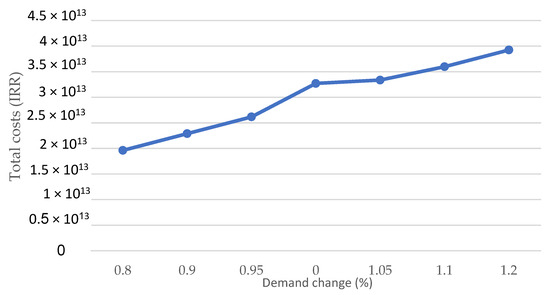

The following stage involved conducting a sensitivity analysis of the model’s most important parameters to evaluate the model’s behavior when these parameters are changed. During this stage, we varied the key parameters by 20% below and above their nominal values and observed the impact on the model’s behavior. We can check the behavior of the model from its result on the values of the objective functions. These changes have been implemented in parameters related to demand. The results of the demand effect on the objective functions can be seen in the graphs below.

Figure 3 illustrates the effect of demand changes on costs. The Demand ranges from 0.8 to 1.2, while the costs range from approximately 2.00 × 1013 to 4.00× 1013. The graph displays a straight relationship between different demand levels and the associated costs. The graph suggests a linear relationship between demand and costs. This indicates that costs are sensitive to changes in demand, resulting in varying cost outcomes across the demand spectrum.

Figure 3.

The effect of demand changes on the costs.

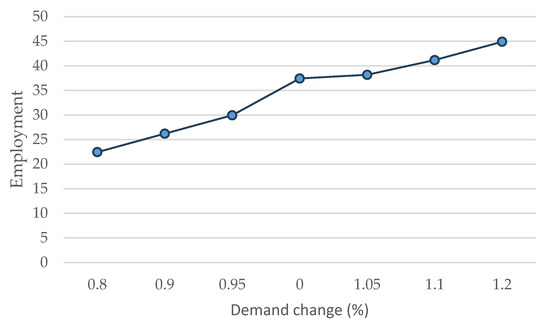

Figure 4 depicts the effect of demand changes on employment. Demand ranges from 0.8 to 1.2, while Employment has values ranging from approximately 22 to 44. The results of the sensitivity analysis show that the parameters employment and demand have a positive correlation; that is, when the parameter of demand rises, the parameter of employment rises as well, demonstrating the two variables’ direct relationship to the system’s performance. The graph indicates a linear relationship between demand and employment. This suggests that employment is sensitive to changes in demand, resulting in varying employment outcomes across the demand spectrum.

Figure 4.

The effect of demand changes on Employment.

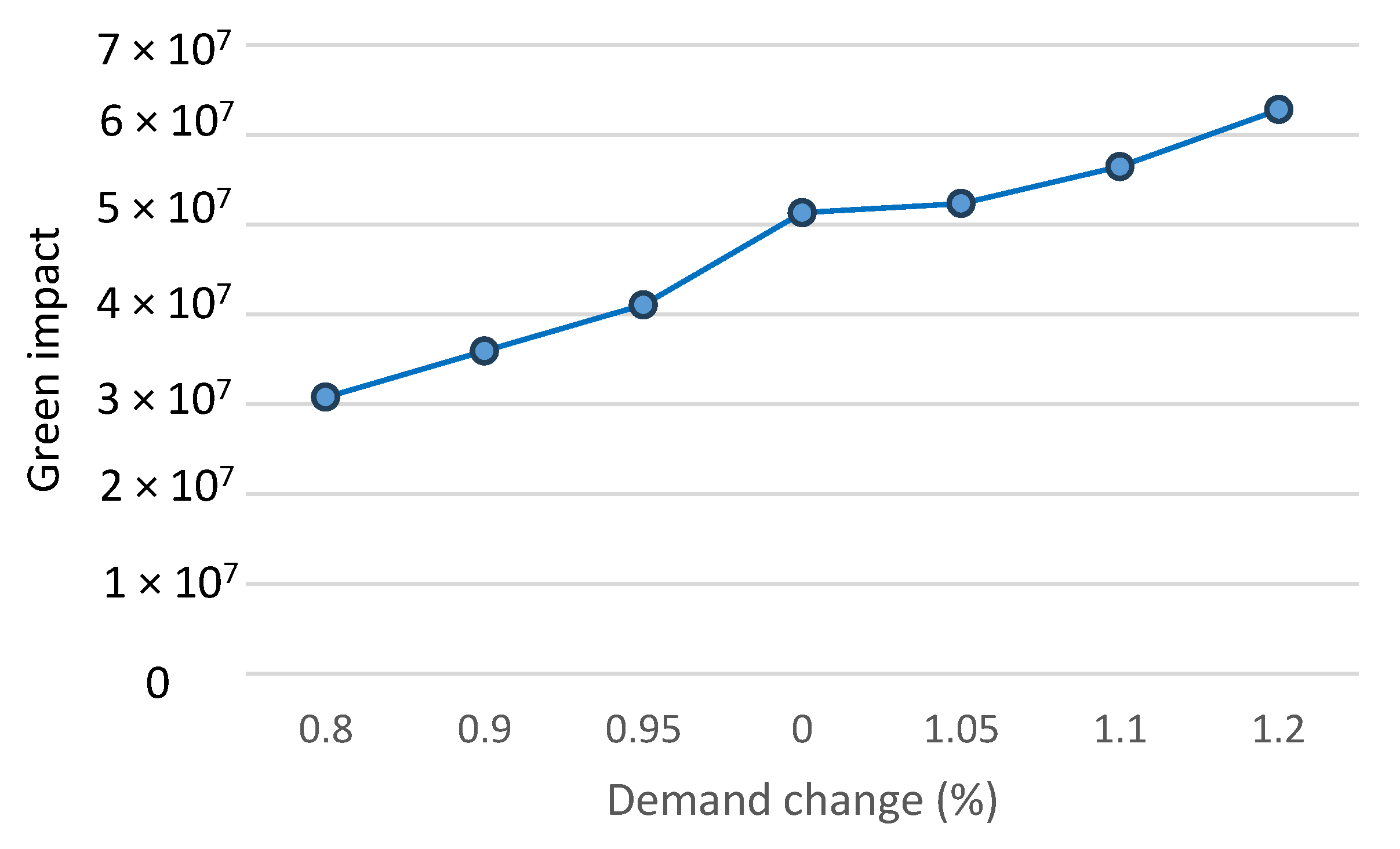

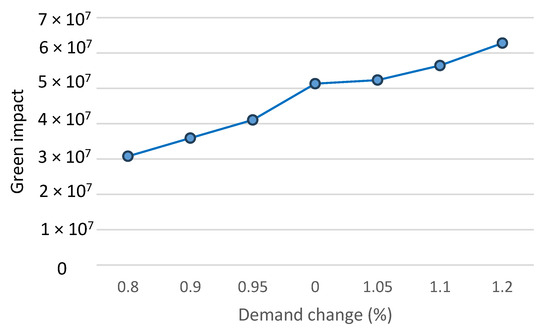

Figure 5 illustrates the effect of demand changes on greenness of the SC. Demand ranges from 0.8 to 1.2, while green performance has values ranging from approximately 3.00 × 107 to 6.40 × 107. According to the results of the sensitivity analysis, demand and green performance show a positive correlation; as one rises, the other rises as well, demonstrating the two variables’ direct relationship to the system’s performance.

Figure 5.

The effect of demand changes on Environment.

4. Discussion

The results of this investigation offer compelling empirical and analytical proof that the WPC sector can successfully accomplish social, environmental, and economic goals by implementing a sustainable CLSC network. Effective network design and operational planning can support sustainability and profitability as mutually reinforcing goals. The proposed multi-objective MILP model illustrates how cost effectiveness, employment creation, and environmental performance can all be optimized simultaneously.

By using the triple-bottom-line (TBL) approach, this study contributes to the CLSC literature in contrast to conventional supply chain optimization models that primarily concentrate on cost reduction and profit maximization. Decision-makers can assess the trade-offs and synergies between economic, social, and environmental outcomes thanks to this thorough framework. This integrated approach represents a new methodological and managerial contribution in the context of the WPC industry, a sector that is inherently linked to sustainability through the reuse of wood and polymer waste.

Strategic facility placement can significantly reduce overall system costs while maintaining balanced regional coverage, as demonstrated by the selection of 17 ideal manufacturing centers, 15 reuse centers, and 9 re-production centers spread across 31 Iranian provinces. The model shows how spatial distribution planning improves supply reliability, streamlines inventory flows, and shortens transportation distances.

These findings highlight for managers the value of data-driven network design in reducing capital and operating costs while preserving adaptability to changes in demand. Additionally, by determining the best places at the provincial level, public and private stakeholders can give high-potential areas priority for infrastructure investment, resulting in a more robust and economical national supply chain.

The social aspect of CLSC design is emphasized by the inclusion of employment as an explicit objective function. The findings demonstrate that regional unemployment rates can be significantly decreased by establishing reuse and re-production facilities in less industrialized provinces. By redistributing industrial activity, socioeconomic gaps between urban and rural areas are lessened and regional development is balanced.

This is an important realization for policymakers: planning for a sustainable supply chain can be a tool for inclusive growth, creating jobs locally and enhancing environmental results at the same time. From a managerial perspective, incorporating social performance metrics into strategic supply chain planning can strengthen community ties, boost corporate reputation, and support corporate social responsibility commitments—elements that investors and customers are beginning to value more and more.

In terms of the environment, the model confirms that WPC production is compatible with resource efficiency and the circular economy. The CLSC network reduces landfill disposal and the extraction of virgin raw materials by methodically reintegrating waste materials through reuse and re-production loops. This directly contributes to the mitigation of deforestation and the reduction of carbon footprints.

Both employment and environmental performance improve proportionately as demand for WPC products rises, according to the sensitivity analysis, indicating that sustainable industrial growth is possible without sacrificing ecological integrity. This is in line with international sustainability goals, like the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the UN, particularly SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production).

Practically speaking, the findings provide policymakers and business executives with useful information. Designing and overseeing sustainable manufacturing networks is made easier with the help of the suggested model.

The model provides industry managers with recommendations on how to invest in reuse and re-production infrastructure that optimizes material recovery and reduces waste in order to strike a balance between economic performance and environmental compliance. Choosing the best locations for facilities to achieve cost effectiveness and greater social impact is another way it helps with strategic resource allocation.

The results offer a geospatial blueprint for regional industrial planning to policymakers. To make sure that industrial growth is in line with national sustainability plans, incentives, infrastructure investments, or workforce training can be directed towards the best provinces. Additionally, the model can assist governments in creating tax or subsidy plans.

The WPC industry is especially well-suited for circular practices because it sits at the nexus of the forestry, plastics, and construction industries. According to the study, WPC products can be used as a sustainable substitute for traditional wood, using post-consumer polymer waste and lessening the strain on natural forests. By promoting material circularity and prolonging product lifecycles, the optimized CLSC structure lessens the environmental impact of each functional unit produced.

Furthermore, integrating reuse and re-production facilities enhances product recovery efficiency and material traceability, two important factors that practically support industrial sustainability. According to these results, the WPC industry may undergo systemic change as a result of the adoption of such network designs, allowing businesses to compete in international markets in an economical and sustainable manner.

The current study uses a mathematical optimization framework that offers prescriptive decisions on facility location and material flow, in contrast to Laubscher et al. [31], who created simulation-based base models to analyze operational dynamics in the South African forestry supply chain. Their research focuses on how systems behave and perform under different operational policies, but our model stresses strategic design that integrates social, environmental, and economic goals for circularity in the wood–plastic composite (WPC) industry. Likewise, a sustainable forest supply chain model that takes into account supplier selection under uncertainty and transportation discounts was presented by Baghizadeh et al. [32]. Our deterministic multi-objective MILP framework, on the other hand, concentrates on closed-loop and multi-product network design, balancing cost, employment, and environmental performance using the Lp-metric method. These differences collectively show how the current study extends sustainability integration into circular production and reuse systems, thereby advancing supply chain modeling related to forests.

5. Conclusions

This paper developed a multi-objective mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) model for the WPC industry’s sustainable CLSC. At the same time, the strategy maximizes employment and environmental sustainability while minimizing overall expenses. A complete framework for balancing economic, social, and environmental goals is provided by combining decisions about facility site, production, reuse, and re-production.

An overall cost of 3.27 × 1013 IRR, an employment index of 37.43, and a green performance score of 5.13 × 107 were the quantitative outcomes of the model’s identification of 17 ideal manufacturing sites, 15 reuse facilities, and 9 re-production centers throughout Iran. Sensitivity analysis demonstrated that demand is the primary driver of system behavior, confirming that fluctuations in demand (±20%) have a major impact on overall cost and environmental performance. Qualitatively, the findings show that reusing and re-producing loops improve sustainability performance while keeping costs low. According to the study, regional integration of recovery and manufacturing facilities promotes balanced economic growth and lessens environmental impacts by making better use of available resources.

The suggested framework, taken as a whole, offers a sector-specific, triple-bottom-line approach to CLSC design that can help industry practitioners and policymakers create SC networks that are more inclusive, sustainable, and profitable. This model may be expanded in future studies to include multi-modal transportation and dynamic demand predictions in order to increase its usefulness and realism. Also, developing efficient heuristic and metaheuristic solution methods will improve the applicability of the model for real life implications. While SCs in reality deal with uncertainty in demand, product returns, and transportation, the model makes the assumption that parameters are deterministic. Future research should use fuzzy or stochastic programming techniques to overcome these constraints. Furthermore, adding digital traceability, different means of transportation, and cutting-edge technology could improve the model’s robustness and applicability in real-world situations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/math13213478/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.J., R.B., S.F., M.A.K. and A.R.G.; Methodology, S.J.; Software, S.J.; Validation, S.J., R.B., S.F., M.A.K. and A.R.G.; Formal analysis, S.J., R.B., M.A.K. and A.R.G.; Investigation, R.B., S.F. and M.A.K.; Resources, S.J. and R.B.; Data curation, S.J., R.B., M.A.K. and A.R.G.; Writing—original draft, S.J.; Writing—review & editing, R.B., S.F., M.A.K. and A.R.G.; Visualization, S.J. and A.R.G.; Supervision, R.B., S.F. and M.A.K.; Project administration, R.B.; Funding acquisition, S.J. and R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is based upon research funded by Iran National Science Foundation (INSF) under project No. 4041595.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Nomenclatures

The following nomenclatures are used in developing the proposed model.

| Indices | |

| P | Set of WPC products (p = 1, …, P) |

| S | Set of supply centers (s = 1, …, S) |

| F | Set of raw material (f = 1, …, F) |

| I | Set of manufacturing centers (i = 1, …, I) |

| J | Set of distribution-collection-inspection centers (j = 1, …, J) |

| K | Set of first customer zones (k = 1, …, K) |

| K’ | Set of second customer zones (k′=1,...,K’) |

| N | Set of green level of products (n = 1,…, n) |

| R | Set of reuse centers (r = 1, …, R) |

| C | Set of re-production centers (c = 1, …, C) |

| T | Set of time period (t = 1, …, T) |

| Parameters | |

| Fixed cost of opening manufacturing center at location i | |

| Fixed cost of opening distribution-collection and inspection center at location j in period t | |

| Fixed cost of opening reuse center at location r in period t | |

| Fixed cost of opening re-production center at location c | |

| The cost of transportation from location a to location d in period t | |

| Sorting cost of product p with green level n in distribution-collection and inspection center j in period t | |

| Inspection cost of product p with green level n in distribution-collection and inspection center j in period t | |

| Reuse cost of product p with green level n in reuse center r in period t | |

| Re-producing cost of product p with green level n in re-production center c in period t | |

| Demand of product p with green level n for first consumer zone k in period t | |

| Cost of purchasing raw material f with green level n from supplier s in period t | |

| Cost of producing product p with green level n in manufacturing center i in period t | |

| Cost of purchasing product p with green level n from customer zone k in period t | |

| Cost of purchasing product p with green level n from customer zone k’ in period t | |

| Production capacity of manufacturing center i for product p with green level n | |

| Storage capacity of distribution-collection and inspection center j for product p with green level n | |

| Capacity of re-production center c for product p with green level n | |

| Capacity of reuse center r for product p with green level n | |

| Storage capacity of distribution-collection and inspection center j for product p with green level n | |

| Conversion ratio of raw materials f to product p | |

| Conversion ratio of product p to raw materials f | |

| Percentage of product p collected from customers sent to reuse center | |

| The number of workers employed by setting up manufacturing center i | |

| The number of workers employed by setting up distribution-collection-inspection center j | |

| The number of workers employed by setting up reuse centers r | |

| The number of workers employed by setting up re-production center c | |

| Total workers unemployed in all potential location i | |

| Total workers unemployed in all potential location j | |

| Total workers unemployed in all potential location c | |

| Total workers unemployed in all potential location r | |

| Green impact of setting up manufacturing center i | |

| Green impact of setting up distribution-collection and inspection center j | |

| Green impact of setting up reuse center r | |

| Green impact of setting up re-production center c | |

| Green impact of purchasing from supplier s | |

| Green impact of producing product p | |

| Green impact of sorting and distributing product p | |

| Green impact of collecting products from first group customer k | |

| Green impact of collecting products from second group customer k′ | |

| Green impact of reused product p collected from customers | |

| Green impact of re-production product p collected from customers | |

| Green impact of distributing reused product r collected from customers | |

| Green impact of distributing raw materials from re-production center c to remanufacturing centers | |

| Decision variables | |

| 1, If the manufacturing center i is opened; 0, Otherwise | |

| 1, If the distribution-collection-inspection center j is opened in period t; 0 Otherwise | |

| 1, If the reuse center r is opened in period t; 0, Otherwise | |

| 1, If the re-production center c is opened; 0, Otherwise | |

| Transported amount of product p with green level n from manufacturing center i to distribution-collection-inspection center j in period t | |

| Transported amount of product p with green level n from distribution-collection-inspection center j to first group customer k in period t | |

| Transported amount of product p with green level n with from reuse center r to second group customer k′ in period t | |

| Transported amount of product p with green level n from first group customer k to collecting center j in period t | |

| Transported amount of product p with green level n from second group customer k′ to collecting center j in period t | |

| Transported amount of raw material f with green level n from supplier s to manufacturing center i in period t | |

| Transported amount of raw material f with green level n from re-production center c to manufacturing center i in period t | |

| Transported amount of product p with green level n from distribution-collection-inspection center j to reuse center r in period t | |

| Transported amount of product p with green level n from distribution-collection-inspection center j to re-production center c in period t | |

References

- Mahmoum-Gonbadi, A.; Genovese, A.; Sgalambro, A. Closed-loop supply chain design for the transition towards a circular economy: A systematic literature review of methods, applications and current gaps. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 323, 129101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; de Pauw, I.; Bakker, C.; van der Grinten, B. Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2016, 33, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.; Carvalho, A.; Barbosa-Póvoa, A.P.; Marques, A.; Amorim, P. Assessment and optimization of sustainable forest wood supply chains—A systematic literature review. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 105, 112–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerman, L.V.; Benitez, G.B.; Gerstlberger, W.; Rodrigues, V.P.; Frank, A.G. Sustainable conditions for the development of renewable energy systems: A triple bottom line perspective. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 75, 103362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pishvaee, M.; Razmi, J.; Torabi, S. An accelerated Benders decomposition algorithm for sustainable supply chain network design under uncertainty: A case study of medical needle and syringe supply chain. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2014, 67, 14–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poursoltan, L.; Seyedhosseini, S.M.; Jabbarzadeh, A. A two-level closed-loop supply chain under the constraint of vendor managed inventory with learning: A novel hybrid algorithm. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2021, 38, 254–270. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, H.; Shen, N.; Liao, H.; Xue, H.; Wang, Q. Uncertainty factors, methods, and solutions of closed-loop supply chain—A review for current situation and future prospects. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 120032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, L.; Huang, L.; Wang, W. Green and sustainable closed-loop supply chain network design under uncertainty. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 227, 1195–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayeri, S.; Paydar, M.M.; Asadi-Gangraj, E.; Emami, S. Multi-objective fuzzy robust optimization approach to sustainable closed-loop supply chain network design. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 148, 106716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, S.R.; Barbosa-Póvoa, A.P.F.; Relvas, S. Design and planning of supply chains with integration of reverse logistics activities under demand uncertainty. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2013, 226, 436–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischmann, M.; Bloemhof-Ruwaard, J.M.; Dekker, R.; van der Laan, E.; van Nunen, J.A.; van Wassenhove, L.N. Quantitative models for reverse logistics: A review. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1997, 103, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guide, J.V.; Van Wassenhove, L.N. The reverse supply chain. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2002, 80, 25–26. [Google Scholar]

- Chun, K.S.; Subramaniam, V.; Yeng, C.M.; Meng, P.M.; Ratnam, C.T.; Yeow, T.K.; How, C.K. Wood–plastic composites made from post-used polystyrene foam and agricultural waste. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2018, 32, 1455–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doustmohammadi, N.; Babazadeh, R. Design of closed-loop supply chain of wood–plastic composite (WPC) industry. J. Environ. Inform. 2020, 35, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mele, A.; Paglialunga, E.; Sforna, G. Climate cooperation from Kyoto to Paris: What can be learnt from the CDM experience? Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2021, 75, 100942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Meng, M.; Han, Y.; Hong, M.; Man, Y. Life cycle cost assessment of recycled paper manufacture in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252, 119868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfarouk, O.; Wong, K.Y.; Wong, W.P. Multi-objective optimization for multi-echelon, multi-product, stochastic sustainable closed-loop supply chain. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2021, 39, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaei, M.; Farhang Moghaddam, B.; Pishvaee, M.S.; Bozorgi-Amiri, A.; Gholamnejad, S. A robust fuzzy optimization model for carbon-efficient closed-loop supply chain network design: A numerical illustration in the electronics industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 113, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, B.; Bhuniya, S. A sustainable flexible manufacturing–remanufacturing model with improved service and green investment under variable demand. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 202, 117154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolazimi, O.; Salehi Esfandarani, M.; Salehi, M.; Shishebori, D. Robust design of a multi-objective closed-loop supply chain by integrating on-time delivery, cost, and environmental aspects: A case study of a tire factory. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 264, 121566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi-Amiri, A.; Zahedi, A.; Gholian-Jouybari, F.; Calvo, E.Z.R.; Hajiaghaei-Keshteli, M. Designing a closed-loop supply chain network considering social factors: A case study on the avocado industry. Appl. Math. Model. 2022, 101, 600–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi-Amiri, A.; Zahedi, A.; Akbapour, N.; Hajiaghaei-Keshteli, M. Designing a sustainable closed-loop supply chain network for the walnut industry. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 141, 110821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouhani, S.; Amin, S.H.; Wardley, L. A novel multi-objective robust possibilistic flexible programming to design a sustainable apparel closed-loop supply chain network. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 365, 121496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmani, A.; Hosseini, M.; Sahami, A. A competitive bilevel programming model for green closed-loop supply chains in light of government incentives. J. Math. 2024, 2024, 4866890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramyar, M.; Mehdizadeh, E.; Hadji Molana, S.M. A new bi-objective mathematical model to optimize reliability and cost of aggregate production planning system in a paper and wood company. J. Optim. Ind. Eng. 2020, 13, 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei, S.; Kheirkhah, A. A comprehensive approach in designing a sustainable closed-loop supply chain network using cross-docking operations. Comput. Math. Organ. Theory 2017, 24, 51–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkır, V.; Başlıgil, H. Multi-objective optimization of closed-loop supply chains in uncertain environment. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 41, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaabane, A.; Ramudhin, A.; Paquet, M. Design of sustainable supply chains under the emission trading scheme. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 135, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengin, M.; Amin, S.H.; Zhang, G. Closing the gap: A comprehensive review of the literature on closed-loop supply chains. Logistics 2024, 8, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, B.; Guchhait, R. A sustainable random paradigm of centralized multi-customized facility with fourth-party logistics (4PL) and cleaner production with remanufacturing. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 525, 146530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laubscher, J.M.; Bekker, J.; Ackerman, S. Base models for simulating the South African forestry supply chain. S. Afr. J. Ind. Eng. 2022, 33, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghizadeh, K.; Zimon, D.; Jum’a, L. Modeling and optimization sustainable forest supply chain considering discount in transportation system and supplier selection under uncertainty. Forests 2021, 12, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).