Abstract

Let be a real number and . This paper is concerned with the quantitative recurrence properties of the system in some (refined) irregular sets. Specifically, let and be a positive function; we define the set and calculate the Hausdorff dimension of the set where stands for infinitely many. Consequently, the Hausdorff dimension of the set is also determined.

MSC:

11K55; 28A80

1. Introduction

The quantitative recurrence property has been a hot research topic in recent years in ergodic theory and dynamical systems; it focuses on the size of the set of points in a dynamical system with a given recurrence rates from the perspective of fractal geometry. Previous research mainly focused on the quantitative recurrence property in the entire phase space, with less attention given to the study of quantitative recurrence in subsets of the phase space. This motivated us to investigate the quantitative recurrence of beta dynamical systems on certain irregular subsets.

Quantitative recurrence originates from the classical Poincaré recurrence theorem. Let be a finite measure-preserving dynamical system with being a separate metric space. The Poincaré recurrence theorem tells us that for -almost, every is recurrent in the sense that

That is to say, for -almost every , the orbit returns to shrinking neighborhoods of the initial point x infinitely often.

However, the result (1) is qualitative in nature and says nothing about the rate at which a generic orbit returns back to the initial point or in what manner the neighborhoods of the start point can shrink. This has motivated many authors to investigate the so-called quantitative recurrence properties. Boshernitzan [1] first established a relationship between the rate at which the orbit of a generic point returns to its neighborhood and the Hausdorff measure of the phase space X (see [2] for further results), providing a new perspective for understanding the recurrence properties of dynamical systems in a quantitative manner. Later, Barreira and Saussol [3] found that the orbit recurrence rate is related to the local dimension. Fernández, Melián, and Pestana [4] related the quantitative recurrence properties of inner functions to their mixing property. Tan and Wang [5] studied the quantitative recurrence properties of general beta dynamical systems from the perspective of fractal geometry. Related work for homogeneous self-similar sets and self-conformal sets can be found in [6,7] and references therein.

Let be a real number and the -transformation be given by

where denotes the integral part of x. In this paper, we study the quantitative recurrence properties of some irregular sets associated with the beta dynamical system for general . To begin with, we recall that every can be uniquely expanded into a finite or infinite series

where for all . The series (2) is called the -expansion of x, which was introduced by Rényi [8], and denotes the sequence of digits of x (see Section 2 for more details).

Let be the sum of the first n digits in the -expansion of x, which is an ergodic sum with , the first digit in the -expansion of x. It is well known that is invariant and ergodic with respect to the Parry measure [9], which is equivalent to the Lebesgue measure. The Birkhoff ergodic theorem implies that exists and is equal to for -almost every .

Furthermore, for , define

Again, by the Birkhoff ergodic theorem, for every , there exists such that (see [10,11]). Multifractal analysis related to was first performed by Besicovitch [12] for and Eggleston [13] for general integer bases. From the perspective of multifractal analysis, it is also interesting to study the following irregular set

or the refined irregular set

where . It was proved that has full Hausdorff dimension [14]. The Hausdorff dimension of depends on the dimensional quantity defined in [11] (see Section 2.3 or [15] for more details). Specifically, for , and , define the set as:

and let , where denotes the set of -admissible sequences of length n (see Definition 2.1). Define the function as:

Using this quantity, Li and Li [15] determined the Hausdorff dimension of .

Theorem 1

(see [15]). Let be a real number and , we have

In particular, for any , we have

The main purpose of this paper is to investigate the quantitative recurrence properties of the beta dynamical system in the refined irregular set . Define the recurrence set by

for general beta dynamical systems, where is a positive function. Set in the sequel of this paper. We remark that the recurrence set shares a similar flavor with the shrinking target set, which was first studied by Hill and Velani [16] (see [17] and references therein for some recent developments). Compared with the extensive developments of the shrinking target problems, the study of recurrence sets lagged behind for several years. Motivated by the work of Boshernitzan [1], Tan and Wang [5], we calculate the Hausdorff dimension of .

Theorem 2

(see [5]). For any , we have

Theorem 2 determines the Hausdorff dimension of the recurrence set for beta dynamical systems. However, it does not tell us anything about the recurrence properties in any subsets of the unit interval. In this paper, we remedy this by studying the intersection of the refined irregular set and the recurrence set . Specifically, let

One of our motivations is to investigate in what manner two types of dynamical behaviors intersect with each other. In particular, we aim to see whether the asymptotic behavior of the first n digit in the -expansion of x and the rate of recurrence of the orbit are independent or not. Our main result reveals that the two types of dynamical properties of are independent in the sense that the Hausdorff dimension of the intersection is equal to the product of the Hausdorff dimensions of and .

Theorem 3.

Let , and , we have

In particular, for any , we have

where stands for infinitely many.

Although the explicit formula of is lacking for general , we have the explicit values for some specific (see Examples 3 and 4). Therefore, Theorem 3 gives the following examples.

Example 1.

Let , and . Then,

Example 2.

Let , and and . Then,

Recently, Shi et al. [18] have determined the Hausdorff dimension of the intersection of the so-called Besicovitch–Eggleston set (see [12,13]) and the recurrence set under the map on the unit interval, where is an integer. Their result is in the flavor of (8). We remark that our result is slightly more general. On one hand, the -transformation might not be Markov for some , which is quite different from the map; on the other hand, different from the set considered in [18], the limsup and liminf of the quantity are not equal for with , which causes additional difficulty.

As a consequence of Theorem 3, we also determine the Hausdorff dimension of the intersection of the irregular set and the recurrence set . Write

Theorem 4.

Let be a real number, we have

For a topological mixing subshift of finite type over a finite alphabet, Zhao [19] established a similar result as in Theorem 4, corresponding to the case where is a Parry number. However, their methods cannot be applied to general beta dynamical systems.

The novelty of our proof lies in constructing an appropriate Cantor subset. When constructing the Cantor set, we need to balance the upper and lower limits and construct a set in which the points satisfy the given recurrence rate through alternating selection of words step-by-step. For general , the corresponding -dynamical system is non-Markov. Therefore, in constructing Cantor subsets, free concatenation of selected words is not allowed. We first proved the results for Parry number and then completed the proof using approximation techniques.

It is plausible that our method could be applied to study the dynamical systems with a certain form of weak specification property (see [14] for more details) or some piecewise monotonic maps on the unit intervals . However, to tackle higher-dimensional dynamical systems, for instance, the automorphisms on the d-dimensional torus, new methods are needed.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. -Expansion

Let and define the -transformation on by . The system is called the beta dynamical system. Taking recursively for all , every can be uniquely expressed as a finite or infinite series

which is called the -expansion of x and is called the sequence of digits of x. We also write as the -expansion of x. Clearly, for any , where if , and if .

Definition 1.

A finite sequence is called β-admissible if there exists such that for all . An infinite sequence is called β-admissible if is β-admissible for all . Denote by the set of all β-admissible sequences with length n and the set of all infinite β-admissible sequences.

We endow with the product topology and the shift operator

The closure of under the product topology in is called the -shift . The lexicographical order on is defined as follows: for , if, and only if, there exists such that for all and . And means or . This lexicographical order can be extended to finite sequences by identifying with the infinite sequence .

The -expansion of 1 is crucial in characterizing and ; this is called Parry’s criterion [9]. If is finite, that is, , then is called a Parry number. In such a case, we put

where denotes the periodic sequence . If is not a Parry number, we also denote the -expansion of 1 by .

Theorem 5

(Parry [9]). Let and , then

(1) if, and only if, ;

(2) the sequence of the β-expansion of 1 is monotone with respect to β. Therefore, for any , we have and .

Rényi [8] showed that

where # denotes the cardinality of a finite set. Thus, the topological entropy of is equal to . Moreover, there exists a unique -invariant measure equivalent to the Lebesgue measure, that is, the Parry measure [9], whose density function is given by .

For any -admissible sequence , the set

is called a n-th basic interval with respect to base . We use to denote the n-th basic interval containing x (with respect to base ).

By the algorithm of -expansion, any n-th basic interval is an interval whose length is less than . We call a full interval if the image of it under the iteration is the unit interval . Clearly, the length of a n-th full interval with respect to base is . When , not every basic interval is full. Indeed, the existence of a non-full interval is the main obstacle to determining the metric properties of general -expansions (see [20,21]).

For and , let

that is, the maximal length of the string of 0’s following . The following criterion of full intervals is useful.

Proposition 1

(see [20,21]). For , let , then

(1) the basic interval is full;

(2) if is full, then is full for any ;

(3) if , then for any , we have

Remark 1

(see [21]). Let be a Parry number; then, there exists such that is full for any .

2.2. Approximation from Below

To obtain the dimensional results in general -expansions, it is useful to apply an approximation method from below for -shifts (see [5,15] and references therein for more details). We first define the projection from to by

It is well known that is Lipschitz, i.e., for any , where d is the metric on defined by .

Let , since , we know that is a Cantor subset of . Define the function by .

Proposition 2

(see [22]). (1) For any , we have .

(2) The function g is bijective, strictly increasing and continuous on .

(3) If be a Parry number, write ; then, g is Hölder continuous on . Moreover,

Now, we shall construct a sequence of Parry numbers approximating from below. Recall that the -expansion of 1 is . For each with , define to be the unique positive solution of the equation

Clearly, is strictly increasing and . Thus, increases to .

By the criterion of full intervals (Proposition 1), we have

Proposition 3

(see [11]). For any , the basic interval is full. Thus,

2.3. Auxiliary Results

Let denote the sum of the first n digits in the -expansion of . We are concerned with the asymptotic properties of . Set

As a consequence of the Birkhoff ergodic theorem, for every , there exists such that . Moreover, by Parry’s criterion (Theorem 5), is determined by the -expansion of 1. In particular, when is a Parry number, that is, , then,

Let and , denote

and

The following dimensional quantity was introduced in [11] (see also [15]), and was used to estimate the Hausdorff dimension of level sets related to the Birkhoff average.

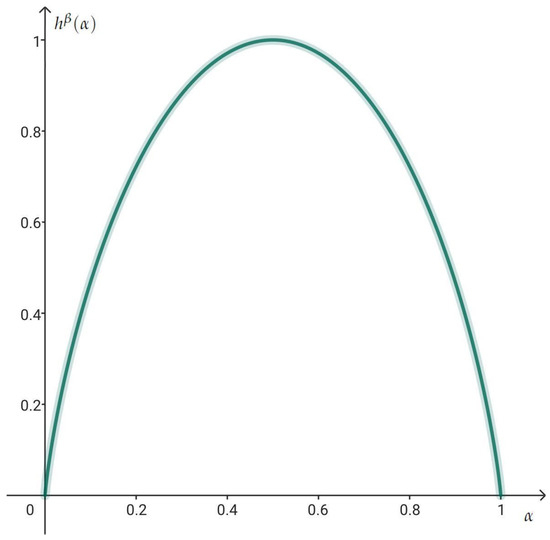

In general, we do not know the explicit formulas of except for some special . The next two examples are borrowed from [15]; we include them for the readers’ convenience.

Example 3.

When , it is easy to see that .

where denotes the binomial coefficient “n choose j”, by Stirling’s formula,

where . Hence,

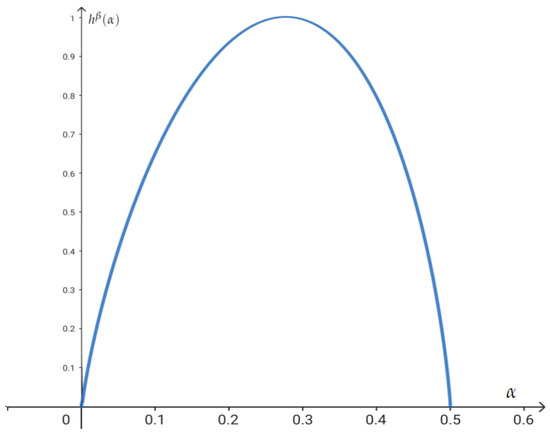

Example 4.

When is the root of the equation , we have ; hence, . In this case,

by Stirling’s formula,

where . Hence,

Figure 1.

The graph of for .

Figure 2.

The graph of for .

Lemma 1

(see [15]). Let β be a Parry number; then, the function is concave and continuous on the interval .

The following mass distribution principle is useful in obtaining the lower bound of the Hausdorff dimension.

Proposition 4

(see [23]). Let F be a Borel set in and μ be a Borel measure in with . If for any , we have

then .

3. Proofs of the Main Results

3.1. Proof of Theorem 3

It suffices to consider the case when ; otherwise it follows directly from Theorem 2. We first show Theorem 3 for Parry numbers; the desired result for general follows by applying the approximation methods described in Section 2.2.

- Upper bound.

The upper bound is obtained by considering the natural coverings. For , denote

and

For any and , let , and define the n-th order basic interval

It follows that

we can obtain

where “i.m.” stands for “infinitely many”. Similarly, we can obtain

For any , set

where is a positive real-valued function. Define

and

For any , set

Clearly, for any ,

Now, we bound the length of from above. For each , we have

and

Thus, for any , we have and

Therefore,

By the definition of and a, for arbitrarily small , there exists and such that for all ,

Put , by (11), we have

As a result,

Since is arbitrarily small, we have . Similarly, . Observe that ; we conclude that

- Lower bound.

We first suppose that is a Parry number. By Remark 1, there exists such that is full for any . In the sequel, we fix such a N. For and , define

and

Lemma 2.

For fixed , we have

Proof.

Evidently, . Hence,

Let be a Parry number, and let N be the fixed constant as above. By Lemma 2, for any , there exist and such that for all , we have

For each , let . We take a sufficiently sparse sequence such that

We shall construct a Cantor subset of , among which the point x will realize the event infinitely many times along the sequence .

To begin with, write where . Let be such that

Define to be the rational number satisfying . Now, we choose a sparse subsequence of recursively in the following way: for each , choose such that

where and . Define integer and rational number , which satisfy

Now, we have obtained a subsequence of , still denoted by , which satisfy

Now, we are ready to construct a Cantor subset .

- Step 1. Level 1 and 2 of the Cantor subset.

By the definition of , the choice of and , and Proposition 1, for any and , we can obtain a full interval

Then, we define the first level of the Cantor set as

where the union is taken over all finite sequences for each , and over all finite sequences .

By construction, for all basic intervals in , both and x are in . Thus, the first -digits in their -expansions are the same, which implies

For each basic interval in , we will construct a subset of , denoted by . Note that each has the form ; define

where the union is taken over all finite sequences for each , and over all finite sequences . Let

By construction, for all basic intervals in , both and x are in . Thus, the first -digits in their -expansions are the same, which implies

- Step 2. Inductions

Assume that the k-level has been constructed. Note that each element of is a -th basic interval, which has the form

where stands for the empty word; if k is odd, then for each , and ; otherwise, we take for each , and . For each , define

where the choice of the finite sequences in the union depends on k: if k is even, then for each , and ; otherwise, we take for each , and .

Notice that the common prefix corresponding to the set of basic intervals in is , which means that is a subset of . By construction, for any basic interval and any , and x share the first digits in their -expansions. As a result,

Repeating the above steps, we obtain a nested sequence , each of which is the union of some basic intervals. The Cantor subset is defined as

- Step 3. .

It is easy to see that . Now, we shall prove that, for any ,

From the choice of , and noting that

it is plausible that the desired result in (18) holds. Now, we check it in detail. By construction, each can be expressed as

We only discuss the case when k is even; the case when k is odd is similar. By the definition of , we have

On the other hand, by the selection of , we have . Thus,

Combining (19) and (20), we arrive at

Similarly, we can show

For a general integer n, if there exists k even such at , then

- Case 1. , we write .

(1) If , by the periodicity of the -expansion of x, we have

and

(2) If , then

and

where the last equality holds since . Hence,

- Case 2. , write , where , and . From the above calculations, we get

- Case 3. , write , where . We assume that ; otherwise, j would be very small and would not affect the limit. We can write , then,

To sum up, now we see that for any , (18) holds. Therefore, the Cantor set is a subset of .

- Step 4. Mass distribution on .

We construct a mass distribution on , and then estimte its local dimension in the next step. Let be a generic interval in and be its mother interval. When k is even, the measure of is defined as

That is, the mass on is distributed uniformly to its offspring. When k is odd, in the above equations, will be replaced by .

For any and a n-th basic interval with , let k be the integer such that ; here, by convention . We still consider the case when k is even; the odd case is similar. Define

where the summation is taken over all basic intervals contained in . Now, we estimate the measure .

(1) If , then

(2) If , let ,

• when and ,

• when and ,

• when and ,

(3) If , then

- Step 5. Local dimension of .

Firstly, we estimate the local dimension of . By the definitions of and a, combining (17), we have

Pick a sufficiently large such that for any ,

Write . For general , we have

(1) If , then we have

it follows that

(2) If , let ,

• when and , we have

Thus,

• when and , we have

Thus,

• When and , we have

Thus,

(3) If , then

Hence,

Now, we consider the ball for any and , we calculate the measure of the ball . Let be such that

Since can intersect at most n-th order basic intervals, it follows that

From the three cases (1)–(3), it follows that

Applying Proposition 4 and letting tend to zero, we have

Similarly, we have

- Step 6. Approximating by Parry numbers.

For a general which is not a Parry number. Let be a strictly increasing sequence of Parry numbers with . For any , we have . Let , define the function by

Lemma 3.

For the above , we have

where .

Proof.

For any , we have

and happens infinitely many times. From the definition of and g, we know that

For any , let , we will show that . Indeed, by (30), it is easy to see

Since happens infinitely many times, there exist two sequences and such that and . This means that and x are in the same -th basic interval, denoted by . Since , and y are also in the -th basic interval . Hence,

Combining (31) and (32), we have . Therefore, for any , there exists such that . That is,

The proof is complete. □

Applying the previous result (29) for Parry numbers and Lemma 3, and noting that , we have

Letting , we obtain

3.2. Proof of Theorem 4

Recall that there exists a unique -invariant and ergodic measure equivalent to the Lebesgue measure. By the Birkhoff ergodic theorem, for -almost every , we have:

for -a.e. , where .

Combining (5), we have

Clearly, . Now, we proceed to prove Theorem 4. Firstly, consider the case where is a Parry number. Let be a strictly increasing sequence that approaches ; then, we have

For the upper bound, we note that , by Theorem 2,

Hence,

The case for a general follows by applying the approximation argument as in the proof of Theorem 3.

4. Conclusions and Further Questions

We study the quantitative recurrence property of the -dynamical system on the set where does not exist, and obtain the dimension of the relevant set. The results indicate that the Hausdorff dimension of the intersection of the recurrence set and the irregular set equals to the product of their Hausdorff dimensions. A similar phenomenon is present in the classical Diophantine approximation (see [24]). This research deepens our understanding of -expansions and the orbit distributions of -dynamical systems from the fractal perspective.

The main result of this paper may be generalized in three directions:

- (1)

- For the -dynamical system , our methods can be extended to study the more general ergodic average , where is an integrable vector-valued function.

- (2)

- Let f and be continuous functions defined on . The local Birkhoff level set is defined as follows:We can estimate the Hausdorff dimension of the intersection of and the recurrence set .

- (3)

- The -dynamical system can be extended to the dynamical system with a certain form of weak specification property (see [14] for more details). We can also consider piecewise monotonic maps on the interval , such as the Manneville–Pomeau map or the Gauss map. Unlike beta dynamical systems, these maps either lack uniform hyperbolicity or have infinitely many branches, which may cause new difficulty.

Author Contributions

Y.C. and W.L.: Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, Grant No. 104972025KFYjc0116.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Boshernitzan, M. Quantitative recurrence results. Invent. Math. 1993, 113, 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saussol, B. An introduction to quantitative Poincaré recurrence in dynamical systems. Rev. Math. Phys. 2009, 21, 949–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreira, L.; Saussol, B. Hausdorff Dimension of Measures via Poincaré Recurrence. Commun. Math. Phys. 2001, 219, 443–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.L.; Melián, M.V.; Pestana, D. Quantitative mixing results and inner functions. Math. Ann. 2007, 337, 233–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.; Wang, B.W. Quantitative recurrence properties for beta-dynamical system. Adv. Math. 2011, 228, 2071–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Wu, M.; Wu, W. Quantitative recurrence properties and homogeneous self-similar sets. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 2019, 147, 1453–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.; Farmer, M. Quantitative recurrence properties for self-conformal sets. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 2021, 149, 1127–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rényi, A. Representations for real numbers and their ergodic properties. Acta Math. Acad. Sci. Hungar 1957, 8, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, W. On the β-expansions of real numbers. Acta Math. Hung. 1960, 11, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, A.H.; Feng, D.J.; Wu, J. Recurrence, dimension and entropy. J. Lond. Math. Soc. 2001, 64, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.; Wang, B.W.; Wu, J.; Xu, J. Localized Birkhoff average in beta dynamical systems. Discret. Contin. Dyn. Syst. 2013, 33, 2547–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besicovitch, A. On the sum of digits of real numbers represented in the dyadic system. Math. Ann. 1935, 110, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggleston, H. The fractional dimension of a set defined by decimal properties. Quart. J. Math. Oxf. Ser. 1949, 1, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D. Irregular sets, the β-transformation and the almost specification property. Trans. Amer. Math. Soc. 2012, 364, 5395–5414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, B. Hausdorff dimensions of some irregular sets associated with β-expansions. Sci. China Math. 2016, 59, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.; Velani, S.L. The ergodic theory of shrinking targets. Invent. Math. 1995, 119, 175–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.Y.; Zhong, K.G. Dichotomy Law for a Modified Shrinking Target Problem in Beta Dynamical System. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Wu, J.; Xu, J. Quantitative recurrence properties in Besicovitch-Eggleston sets. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2024, 540, 128654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C. Quantitative recurrence properties in the historic set for symbolic systems. Dyn. Syst. 2021, 36, 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, A.H.; Wang, B.W. On the lengths of basic intervals in beta expansions. Nonlinearity 2012, 25, 1329–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wu, J. Beta-expansion and continued fraction expansion. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2008, 339, 1322–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, J.C.; Li, B. The multifractal spectra for the recurrence rates of beta-transformations. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2014, 420, 1662–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falconer, K. Fractal Geometry: Mathematical Foundations and Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Levesley, J.; Salp, C.; Velani, S.L. On a problem of K. Mahler: Diophantine approximation and Cantor sets. Math. Ann. 2007, 338, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).