Abstract

A stochastic SEIR epidemic model with standard incidence and vertical transmission was developed in this work. The primary goal of this study was to determine whether stochastic environmental disturbances affect dynamic features of the epidemic model. The existence, uniqueness, and boundedness of global positive solutions are stated. A threshold was determined for the extinction of the infectious disease. After that, the existence and uniqueness of an ergodic stationary distribution were verified by determining the correct Lyapunov function. Ultimately, theoretical outcomes of numerical simulations are shown.

Keywords:

stochastic SEIR model; vertical transmission; standard incidence; extinction; stationary distribution MSC:

37H10; 60H10; 92B05

1. Introduction

As a huge challenge throughout human history, infectious diseases have always been evolving and endangering human life. Since ancient times, scientists have been committed to studying the transmission mechanisms and effective response strategies of infectious diseases. With the continuous development of science and technology, our understanding of different fields has greatly deepened [1,2]. Among these developments, biological mathematical models play an important role in infectious disease research [1,3,4]. Since the proposal of the basic SIR (susceptible–infected–recovered) epidemic model by Kermack and McKendrick [1], various biological mathematical models have been established and analyzed, such as SIS, SIR, and SIRS [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. Different infectious diseases have different characteristics, for example, infected individuals in a latent period before infection, so scholars introduced an exposed (E) class to study hepatitis B, AIDS, and so on. The SEIR epidemic model has been established and extensively studied [12,13,14].

In addition, the above mentioned diseases have a vertical transmission characteristic; with infected mothers infecting their unborn or newborn babies, and their descendants may be infected or susceptible [15,16]. Therefore, many scholars have studied infectious diseases with vertical transmission by establishing corresponding biological models [15,17,18]. Based on the SEIR epidemic model with vertical transmission proposed by Li et al. [15], we constructed a subsequent deterministic model:

in which the numbers of susceptible, exposed (in the latent period), infectious, and recovered individuals are indicated by , , , and , respectively. = + + + denotes the overall number of population individuals. The definitions in the following Table 1 apply to the parameters in model (1). All parameter values are non-negative.

Table 1.

Biological significance of each parameter.

Meanwhile, in the real world, the transmission of infectious illnesses is often influenced by numerous random factors, such as climate change, social dynamics, and population mobility. These random factors can have a significant impact on the transmission of infectious illnesses, sometimes even leading to disease outbreaks and large-scale transmission. Therefore, studying the effect of random disturbances on the transmission of infectious illnesses has become an important research direction. Like Jiang et al. [10] and Qi et al. [19], many authors have studied how random factors affect the dynamics of infectious diseases [20,21,22,23,24,25]. However, the dynamic research on SEIR epidemic models with vertical transmission and random disturbances seems to be limited. The research motivation of this study is to reveal how environmental disturbances affect the dynamic behavior of systems (1).

In this paper, we presume a positive proportional relationship between stochastic white noise and different populations (S-E-I-R). Hence, we derive the subsequent stochastic model:

in which the normal Brownian motion is independent and , expresses the white noise intensity for different populations (S-E-I-R). The above i equals 1, 2, 3, and 4.

Remark 1.

We presume that the vertical infection rates of E (exposed) and I (infected) are the same in this study, 0 < p < 1, 0 < q < 1, and when they are different, further discussion is given.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2 and Section 3, we examine the existence, uniqueness, and boundedness of global positive solutions. In Section 4, the threshold criterion for the extinction of a disease can be found. In Section 5, it is determined that an ergodic stationary distribution exists and is unique. Ultimately, Section 6 presents numerical simulations and conclusions.

2. Existence of the Unique Global Positive Solution

In this section, the unique global positive solution of system (2) is proven to exist. First, we briefly introduce the subsequent lemma.

Lemma 1

([26]). (Itô formula) For a detailed explanation about Itô formula, please refer to [26]. These are the primary formulas that are applied.

then by the diffusion operator :

another expression for the Itô formula is

Next, we demonstrate that there is a unique global solution for the stochastic system (2).

Theorem 1.

For any initial condition , there is a unique global positive solution for system (2) which will be maintained in with probability one.

Proof.

Considering the subsequent non-negative -function P:

Applying Itô’s formula results in

in which

where the constant K is positive. The approach of proof is the same as in [27], and the remainder proof is omitted. □

3. Boundedness

The solutions to system (2) are shown to be bounded in this section.

Theorem 2.

For any initial condition , the solution satisfies

4. Extinction

The primary focus of this section is to discuss the threshold of (2) for the extinction of disease.

Lemma 2.

Proof.

According to Theorem 2, we can obtain

Hence, we can easily obtain

Let

From the quadratic variations such that

With the large number theorem for the martingale (see Lemma 3.1 in [29]) and (5), one has

Similarly, other equations can also be obtained. In summary, the proof has been completed. □

A parameter is defined

where .

Theorem 3.

The solution of system (2) with initial condition is denoted by . If holds, then ,a.s. which suggests that the illness becomes extinct.

Proof.

A -function V is constructed:

By dividing both sides by t after integrating (6) from 0 to t, we derive

By taking the superior limit on either side of (7), we may obtain that by combining Lemma 2 with ,

which means , .a.s. This shows that the illness will eventually disappear. . a.s. can also be easily obtained from system (2). Thus, the proof is completed. □

5. Stationary Distribution and Ergodicity

We verify in this section that system (2) exists as an ergodic stationary distribution by applying Theorem 4 and Assumption (B) [30], which indirectly reflects the persistence of the disease.

A parameter is defined

Theorem 4.

There exists a unique ergodic stationary distribution for system (2) if .

Proof.

Let .

The following is the diffusion matrix of System (2)

, given any , then

where , with being a sufficiently large constant.

Thus, the condition (B.1) of Assumption (B) [30] is proved. Next, we define a -function

where

the constant is small enough to ensure

In addition to being a sufficiently large positive constant, M also meets the following requirement

where

and

It is worth noting that , , , Y, and C are derived from the subsequent proof process.

Clearly,

in which . There exists a minimum at since is continuous on .

The -function is defined:

According to Itô’s formula,

where

With Itô’s formula, we can furthermore obtain

let

where

and

Similarly,

and

Therefore,

After, we define the bounded closed set that follows

where is a sufficiently small number. Within , we can select small enough so that

where A, C, D, F, H, and J are positive constants which can be determined from the later Equations (16), (18), (20), (21), (22), and (23), respectively. For ease of proof, eight domains are created by dividing ,

Next, we demonstrate that in the eight mentioned domains, that is, in the .

Case 1. In conjunction with (8) and , we have

where

Case 2. Considering (9), if , one attains

Case 3. Combining (10) with , one has

where

Case 4. When , together with (11), this results in

Case 5. Applying (12) if has

where

Case 6. Given that , (13) implies that

where

Case 7. Combining (14) with , one obtains

where

Case 8. When , (15) implies that

where

Obviously, one can conclude that for a small enough , through Equations (16)–(23),

Hence, the requirement (B.2) of Assumption (B) from [30] holds. Theorem 4 is fully proved. □

6. Numerical Simulations and Conclusions

Next, we conducted numerical simulations.

- (1)

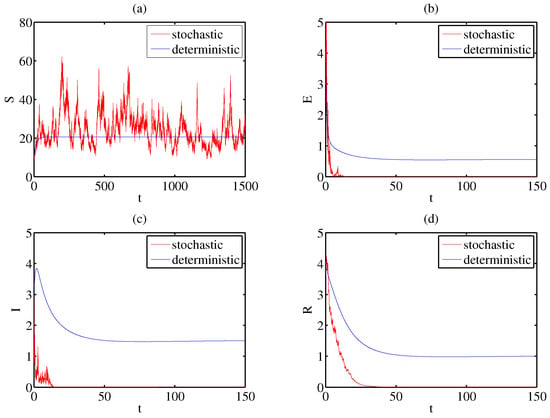

- Let = 0.1, = 1.2, = 1.2, and = 0.1. The other parameter values are as described above, calculated as , which fulfills the requirement of Theorem 3 and verifies the conclusion of Theorem 3. Figure 1 provides a better explanation.

Figure 1. (a–d): Extinction trend of System (2).

Figure 1. (a–d): Extinction trend of System (2). - (2)

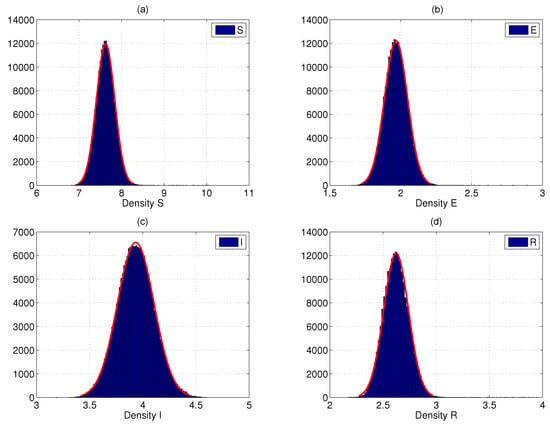

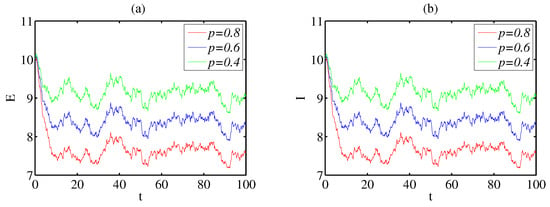

- Let , where . Computing that satisfies the requirement of Theorem 4, and the system (2) supports an ergodic stationary distribution. The numerical simulation results are shown in Figure 2. This also indicates that the disease is prevalent in a stable state.

Figure 2. (a–d): The density function of the solution. (e–h): The persistence of the system (2).

Figure 2. (a–d): The density function of the solution. (e–h): The persistence of the system (2). - (3)

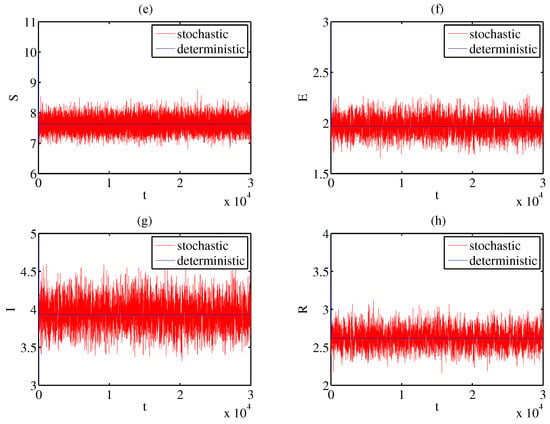

- Due to the consideration of vertical transmission in this paper, the impact of parameter p on the system (2) is discussed. Figure 3 shows an inverse trend, where the larger the value of p, the smaller the value when it tends to stabilize. Therefore, by controlling the value of p, further exploration of the dynamic properties of disease transmission can be carried out in future work.

Figure 3. (a,b): The impact of parameter p on the system (2).

Figure 3. (a,b): The impact of parameter p on the system (2).

Compared to other papers, this paper establishes a new stochastic SEIR epidemic model and explores how environmental disturbances affect the dynamic behavior of the system. First, the existence, uniqueness, and boundedness of global positive solutions are shown. Second, we demonstrate the threshold requirements for disease extinction and stationary distribution. The illness will go extinct if , and the system (2) accords with a stationary distribution if . By comparing the parameter values, as well as Figure 1 and Figure 2, the disease becomes extinct when white noise intensity is high and becomes prevalent when it is low. From this perspective, white noise can suppress the occurrence of diseases, indicating that the dynamics of the epidemic system are significantly impacted by random environmental disruptions. In addition, the random noise considered in this article is linear; therefore, in future work, the impact of nonlinear random noise on infectious disease dynamics will also be considered.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, R.L.; writing—review and editing, R.L. and X.G.; visualization, R.L. and X.G.; supervision, X.G.; project administration, X.G.; funding acquisition, X.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 11801323).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kermack, W.O.; McKendrick, A.G. A contributions to the mathematical theory of epidemics (Part I). Proc. R. Soc. A 1927, 115, 700–721. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Meng, D. Quasi-Semilattices on Networks. Axioms 2023, 12, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, A.; Greenhalgh, D.; Hu, L.; Mao, X.; Pan, J. A stochastic differential equation SIS epidemic model. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 2011, 71, 876–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Onofrio, A. On pulse vaccination strategy in the SIR epidemic model with vertical transmission. Appl. Math. Lett. 2005, 18, 729–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Jiang, D. The threshold of a stochastic SIS epidemic model with vaccination. Appl. Math. Comput. 2014, 243, 718–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Zhao, S.; Feng, T.; Zhang, T. Dynamics of a novel nonlinear stochastic SIS epidemic model with double epidemic hypothesis. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2016, 433, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, G.; Chen, T.; Li, Z. Threshold Analysis of a Stochastic SIRS Epidemic Model with Logistic Birth and Nonlinear Incidence. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCluskey, C.C. Complete global stability for an SIR epidemic model with delay-distributed or discrete. Nonlinear Anal. Real. 2010, 11, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Chen, L. The dynamics of a new SIR epidemic model concerning pulse vaccination strategy. Appl. Math. Comput. 2008, 197, 582–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Jiang, D.; Shi, N.; Ji, C. The ergodicity and extinction of stochastically perturbed SIR and SEIR epidemic models with saturated incidence. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2012, 388, 248–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahrouza, A.; Omaria, L.; Kiouachb, D.; Belmaatic, A. Complete global stability for an SIRS epidemic model with generalized non-linear incidence and vaccination. Appl. Math. Comput. 2012, 218, 6519–6525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Muldowney, J. Global stability for the SEIR model in epidemiology. Math. Biosci. 1995, 125, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, S.; Chen, L.; Teng, Z. Pulse vaccination of an SEIR epidemic model with time delay. Nonlinear Anal. Real. 2008, 9, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, T. The dynamics and therapeutic strategies of a SEIS epidemic model. Int. J. Biomath. 2013, 6, 1350029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Smith, H.; Wang, L. Global dynamics of an SEIR epidemic model with vertical transmission. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 2001, 62, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busenberg, B.S.; Cooke, K. Vertically Transmitted Diseases; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.; Xie, D.; Chen, L. Pulse vaccination strategy in a delayed SIR epidemic model with vertical transmission. Discrete Cont. Dyn. B 2006, 7, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Cui, J. The stability of an SEIRS model with nonlinear incidence, vertical transmission and time delay. Appl. Math. Comput. 2013, 221, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Meng, X. Mathematical modeling, analysis and numerical simulation of HIV: The influenceof stochastic environmental fluctuations on dynamics. Math. Comput. Simul. 2021, 187, 700–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, X.; Khan, A.; Din, A. Probability Analysis of a Stochastic Non-Autonomous SIQRC Model with Inference. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Meng, X. Dynamics Analysis of a Predator–Prey Model with Hunting Cooperative and Nonlinear Stochastic Disturbance. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yuan, S.; Zhao, D. Threshold behavior of a stochastic SIS model with levy jumps. Appl. Math. Comput. 2016, 275, 255–267. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Z.; Zhou, Y. Existence of two periodic solutions for a non-autonomous SIR epidemic model. Appl. Math. Model. 2011, 35, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wang, K. Persistence and extinction in stochastic non-autonomous logistic systems. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2011, 375, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhang, S.; Meng, X. Dynamics analysis and numerical simulations of a delayed stochastic epidemic model subject to a general response function. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2019, 38, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X. Stochastic Differential Equations and Their Applications; Horwood: Chichester, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, X.; Marion, G.; Renshaw, E. Environmental brownian noise suppresses explosions in population dynamics. Stoch. Proc. Appl. 2002, 97, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D. Study on the threshold of a stochastic SIR epidemic model and its extensions. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. 2016, 38, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Jia, J. Qualitative study of a stochastic SIRS epidemic model with information intervention. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2020, 547, 123866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasminskii, R. Stochastic Stability of Differential Equations; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 66. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).