Abstract

Two vertices u and v in a graph are in the same orbit if there exists an automorphism of G such that . The orbit number of a graph G, denoted by , is the number of orbits that partition . All vertex-transitive graphs G satisfy . Since the n-dimensional hypercube, denoted by , is vertex-transitive, it follows that for . The twisted crossed cube, denoted by , is a variant of the hypercube. In this paper, we prove that if , , and if .

MSC:

05C51; 05C60; 68R10

1. Introduction

Interconnection networks are usually modeled as undirected simple graphs , where the vertex set V represents processing elements and the edge set E represents communication channels. The graph parameters of an interconnection network can serve as metrics to evaluate the reliability of a multiprocessor system. A key aspect of interconnection networks is their symmetry, which plays a pivotal role in their design and functionality. An automorphism of a graph is a mapping : such that there is an edge if and only if is also an edge in . A graph is vertex-transitive if, for any two vertices u and v of G, there exists an automorphism such that . Intuitively, a vertex-transitive graph appears identical from the perspective of any vertex. This property is particularly advantageous for designing and simulating algorithms on graphs, as it ensures uniformity and symmetry across all vertices. Clearly, every vertex-transitive graph is regular, for example, hypercubes. However, not all regular graphs are vertex-transitive, such as crossed cubes and locally twisted cubes [1,2,3,4].

Definition 1

([5]). Two vertices u and v in a graph are in the same orbit if there exists an automorphism ϕ of G such that . The orbit number of a graph G, denoted by , is the number of orbits, which form a partition of , in G.

The automorphism group of an interconnection network is significant in many aspects. Within the network, every processor in the same orbit is identical in relation to its position, ensuring uniformity. This property facilitates straightforward implementation and simplifies routing using consistent rules, particularly in distributed environments. The Frucht graph, introduced by Robert Frucht in [6], is a cubic graph consisting of 12 vertices and 18 edges. It is a 3-regular graph, but its automorphism group consists of only the trivial automorphism. Liu, Lan, Chou, and Chen [3] discovered that although locally twisted cubes are not vertex-transitive for , these cubes exhibit the property of even–odd vertex-transitivity, meaning that they have exactly two orbits, with each orbit containing all vertices of the same parity. Kulasinghe and Bettayeb [4] proved that the n-dimensional crossed cube, denoted by (also referred to as the multiply-twisted hypercube in their paper), is not vertex-transitive for . Shiau, Wang, and Pai [5] further demonstrated that for . The folded crossed cube, a variation of the crossed cube, was studied by Liu [7], who showed that when is odd, and when is even.

The twisted crossed cube, a variant of the twisted cube [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16] and the crossed cube, was introduced by Wang, Liang, Qi and Lin in [17]. They investigated its basic network properties in terms of regularity, connectivity, fault tolerance, recursiveness, and so on. In this paper, we prove that if , , and if . The main results are presented in Section 2. Section 3 contains our concluding remarks.

2. Twisted Crossed Cubes

An n-dimensional twisted crossed cube can be modeled as a graph with a vertex set and an edge set such that every node v is distinctly labeled by an n-bit binary string . The negate of for is denoted by . Define , where j is the largest even number such that , and ⊕ is the exclusive operation. For simplicity, we also use to represent when the context is clear.

Two 2-bit binary strings, and , are called pair-related, denoted by , if and only if . For notational convenience, we also represent string b as if . In addition, we say a and b are crossed pair-related, denoted by , if and only if , and represent string b as if .

Definition 2

([17]). The n-dimensional can be defined recursively as follows: is , with the complete graph of two vertices having the labels 0 and 1; for , consists of two -dimensional twisted crossed cubes, and , where = , where and . The vertex v = in and the vertex u = in are adjacent in if and only if

- 1.

- if n is even, and

- 2.

- For , , and

- 3.

- If , ; otherwise, .

We say that vertex u is the kth-neighbor of vertex v, denoted by , if u and v are adjacent along dimension k for . According to Definition 2, vertex u satisfies the following conditions:

- ;

- ;

- ;

- If , ;

- If , ;

- If even and , ;

- If even and , ;

- If odd and , ;

- If odd and , .

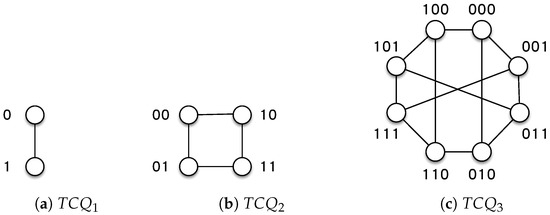

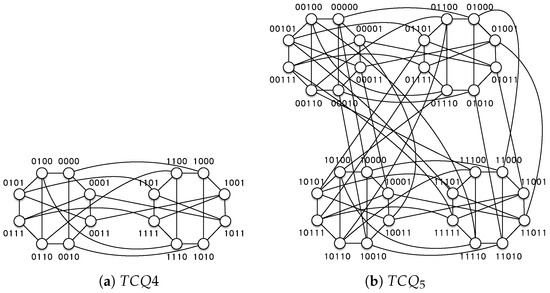

For example, let . Then, , , , , and . Figure 1 and Figure 2 demonstrate the twisted crossed cubes , , , , and .

Figure 1.

The twisted crossed cubes , , and .

Figure 2.

The twisted crossed cubes and .

Lemma 1.

.

Proof.

According to Figure 1, it is easy to see that . □

2.1. The Upper Bound of

Let denote for some for all . We use ★ to represent any possible character, i.e., 0 or 1. A function is bijective if and only if it is invertible; that is, a function is bijective if and only if there is a function , the inverse of f, such that each of the two ways for composing the two functions produces the identity function for each x in X and for each y in Y.

According to the definition of automorphisms, to prove that for some i, is an automorphism of , we need to show that for every edge, if and only if there exists an edge . Since (=) is bijective, it suffices to focus on one direction of the proof.

Lemma 2.

For any n, the function for all vertices is an automorphism of .

Proof.

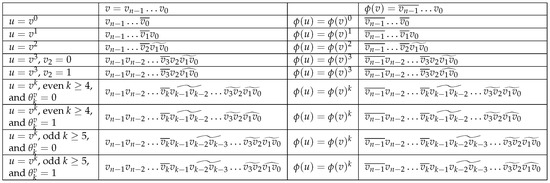

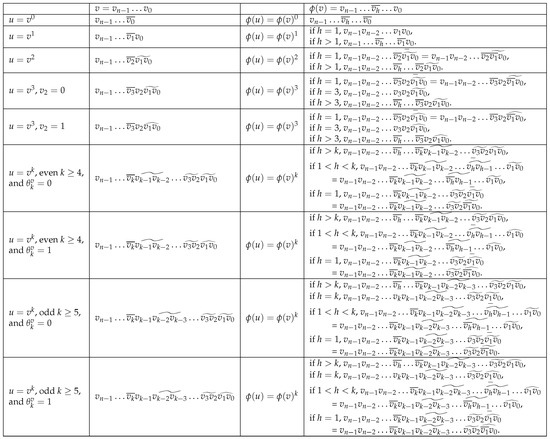

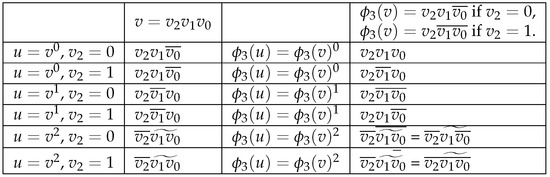

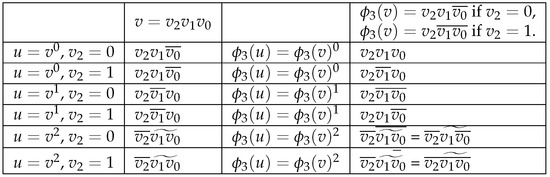

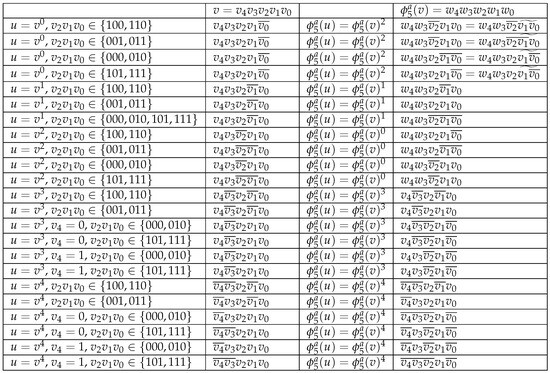

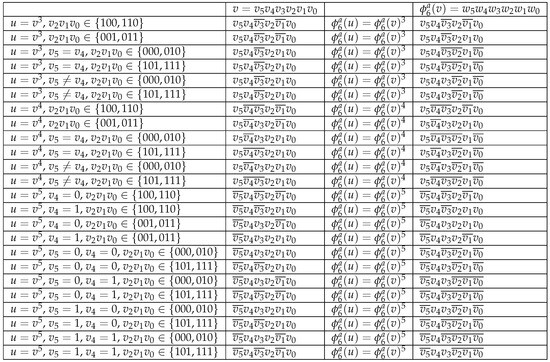

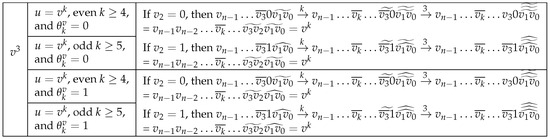

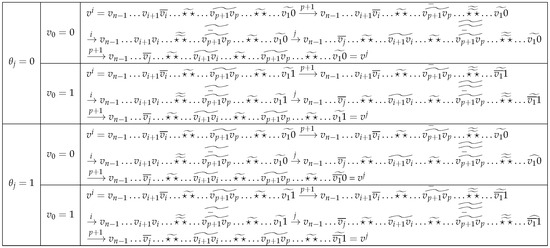

Let . All possible vertices u and , corresponding to v and , are depicted in Figure 3. It is straightforward to verify that forms an edge in , thereby confirming the validity of this lemma. □

Figure 3.

All possible vertices u and with respect to v and , where .

Proposition 1.

and .

Lemma 3.

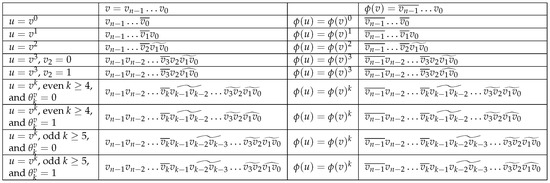

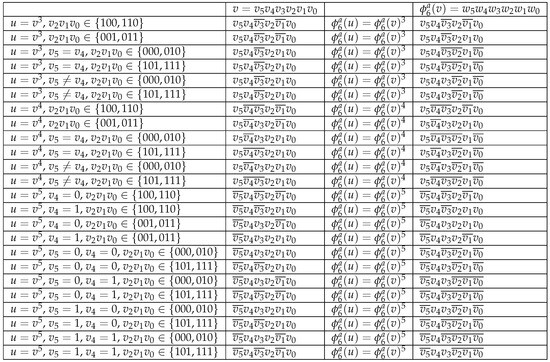

The function , where is odd, defines an automorphism of for all vertices .

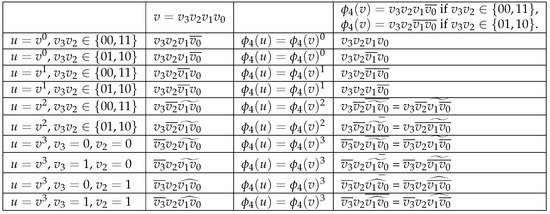

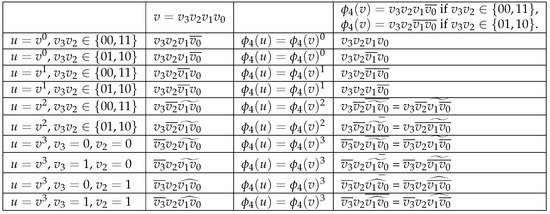

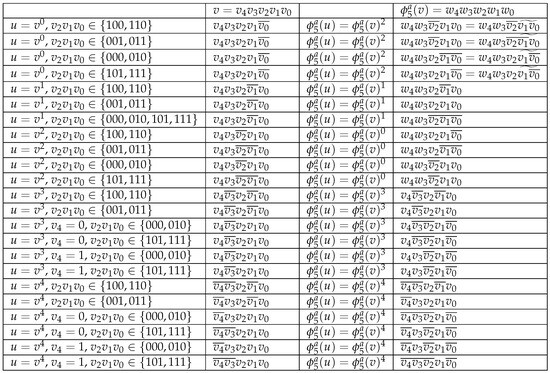

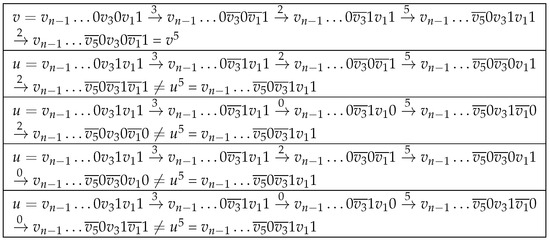

Proof.

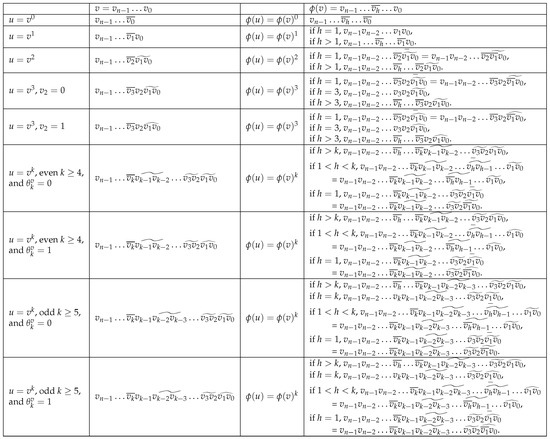

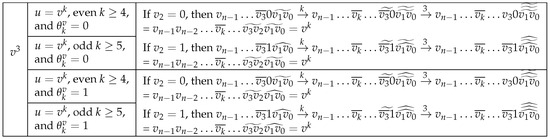

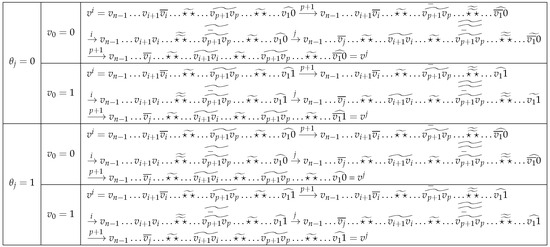

Let . All possible vertices u and , corresponding to v and , are depicted in Figure 4. It is straightforward to verify that forms an edge in , thereby confirming the validity of this lemma. □

Figure 4.

All possible vertices u and with respect to v and , where for is odd.

Lemma 4.

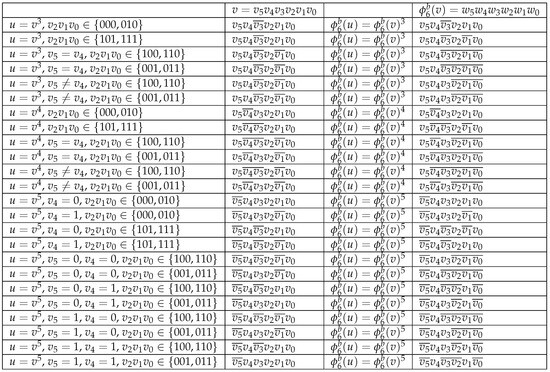

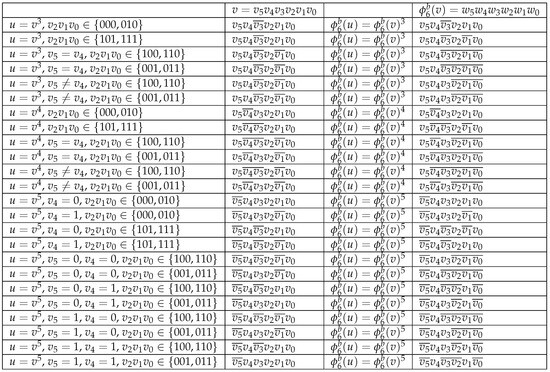

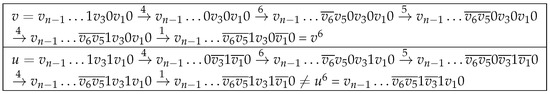

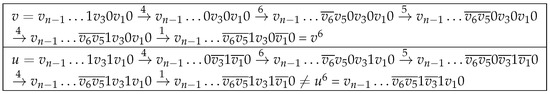

The function , where is even, defines an automorphism of for all vertices .

Proof.

Figure 5.

All possible vertices u and with respect to v and , where for is even.

Proposition 2.

, , , and .

Proof.

If , then , , , and . If , then , , , and . □

Lemma 5.

For all vertices , let

The function defines an automorphism of .

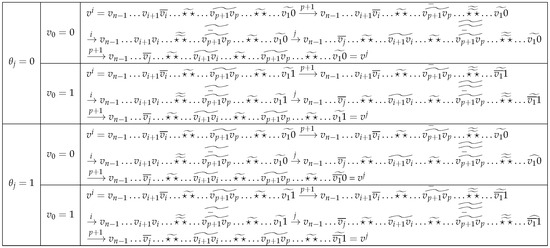

Proof.

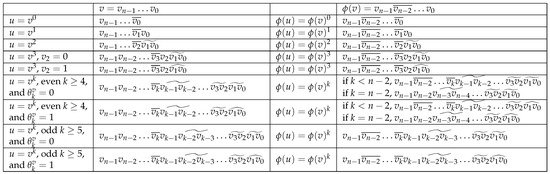

To prove that is an automorphism of , we need to show that for each edge, if and only if there exists an edge . Since (=) is bijective, it suffices to focus on one direction of the proof. Let . All possible vertices u and , corresponding to v and , are depicted in Figure 6. □

Figure 6.

All possible vertices u and with respect to v and .

Lemma 6.

For all vertices , let

The function defines an automorphism of .

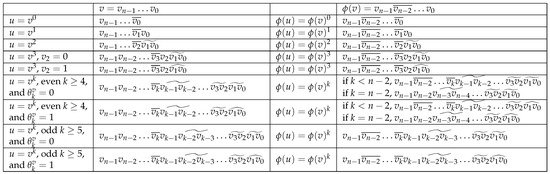

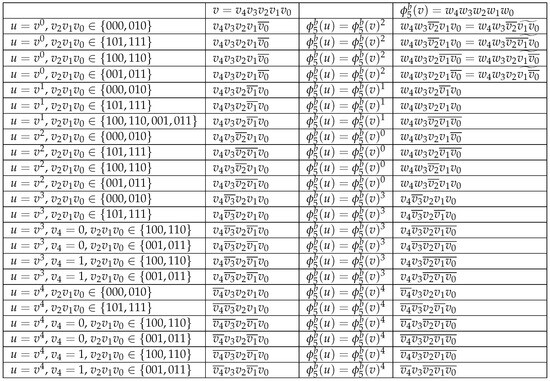

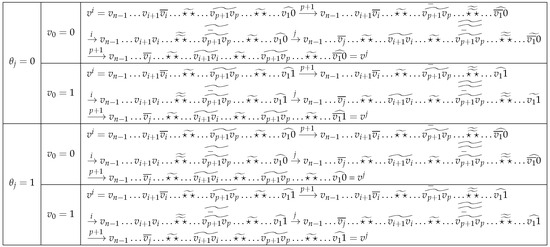

Proof.

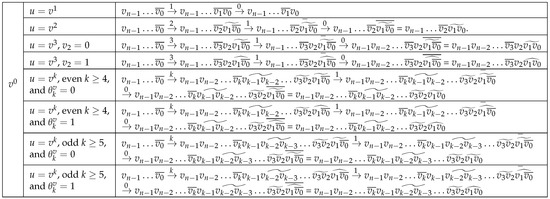

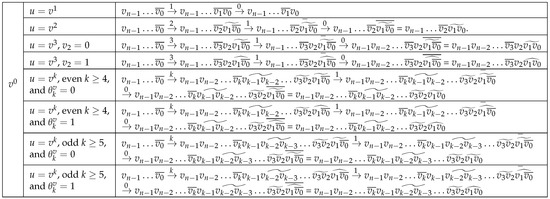

To prove that is an automorphism of , we need to show that for each edge, if and only if there exists an edge . Since (=) is bijective, it suffices to focus on one direction of the proof. Let . All possible vertices u and , corresponding to v and , are depicted in Figure 7. □

Figure 7.

All possible vertices u and with respect to v and .

In the following lemmas, we define four automorphism functions of and : , , , and . These functions are used to map a string ending in 000 to a string ending in 101, and a string ending in 001 to a string ending in 100.

Lemma 7.

For all vertices , let , where

The function defines an automorphism of .

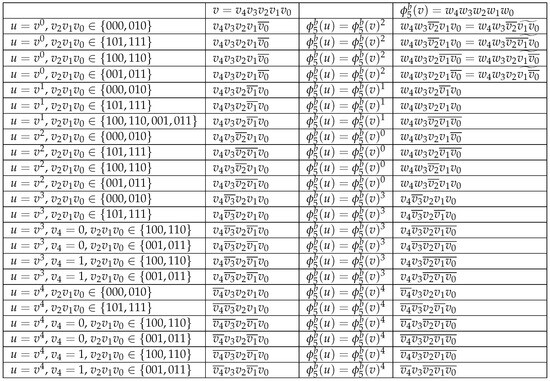

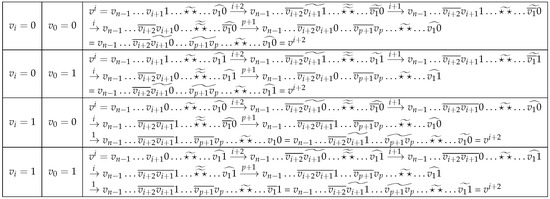

Proof.

To prove that is an automorphism of , we need to show that for each edge, if and only if there exists an edge . Since (=) is bijective, it suffices to focus on one direction of the proof. Let . All possible vertices u and , corresponding to v and , are depicted in Figure 8. □

Figure 8.

All possible vertices u and with respect to v and .

Lemma 8.

For all vertices , let , where

The function defines an automorphism of .

Proof.

To prove that is an automorphism of , we need to show that for each edge, if and only if there exists an edge . Since (=) is bijective, it suffices to focus on one direction of the proof. Let . All possible vertices u and , corresponding to v and , are depicted in Figure 9. □

Figure 9.

All possible vertices u and with respect to v and .

Lemma 9.

For all vertices , let , where

The function defines an automorphism of .

Proof.

To prove that is an automorphism of , we need to show that for each edge, if and only if there exists an edge . Since (=) is bijective, it suffices to focus on one direction of the proof. Let . All possible vertices u and , corresponding to v and , are depicted in Figure 10. Note that we omit the parts of , , and that are analogous to those depicted in Figure 8. □

Figure 10.

All possible vertices u and with respect to v and .

Lemma 10.

For all vertices , let , where

The function defines an automorphism of .

Proof.

To prove that is an automorphism of , we need to show that for each edge, if and only if there exists an edge . Since (=) is bijective, it suffices to focus on one direction of the proof. Let . All possible vertices u and , corresponding to v and , are depicted in Figure 11. Similarly, we omit the parts of , , and that are analogous to those depicted in Figure 9. □

Figure 11.

All possible vertices u and with respect to v and .

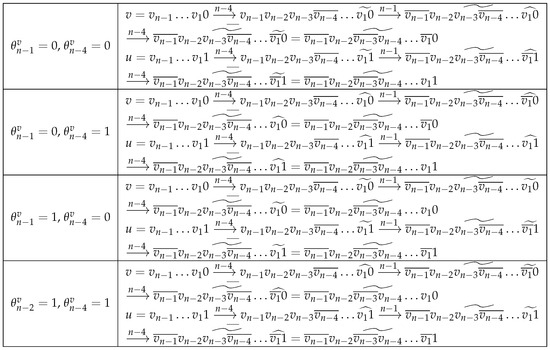

Lemma 11.

, , and ≤ for .

Proof.

According to Lemma 3, vertices and belong to the same orbit for odd integers . Applying a single automorphism halves the number of orbits while doubling the size of each orbit. Lemma 2 implies that vertices and are in the same orbit. According to Lemma 4, if n is even, vertices and are in the same orbit. Therefore, the total number of orbits in is at most .

Now, we can partition the vertex sets of as follows: (1) into two groups, and ; (2) into two groups, and ; (3) into four groups, , , , and ; and (4) into four groups, , , , and . According to Lemmas 5 and 6, vertices 000 and 001, 0000, and 0001 belong to the same orbit. Lemmas 7 and 8 imply that 00000 and 00101, as well as 00001 and 00100, are in the same orbit. Similarly, Lemmas 9 and 10 show that 000000 and 000101, and 000001 and 000100, are in the same orbit. Therefore, and . □

2.2. The Lower Bound of

For any vertex , we discuss the shortest path from to that does not pass through v, where . Let denote the shortest distance between and that does not pass through v.

Proposition 3.

and .

Proof.

If , then , , = , and . If , then , , =, and . □

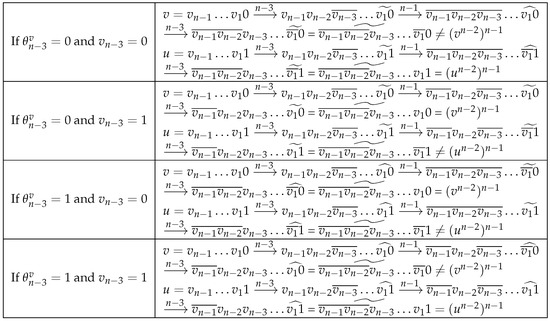

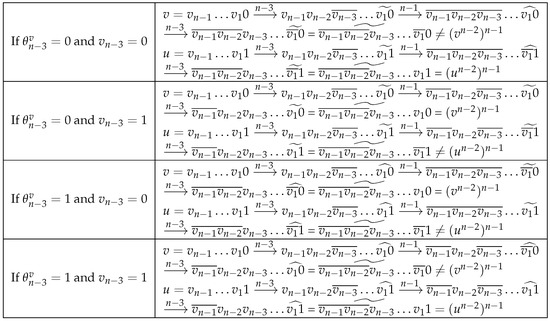

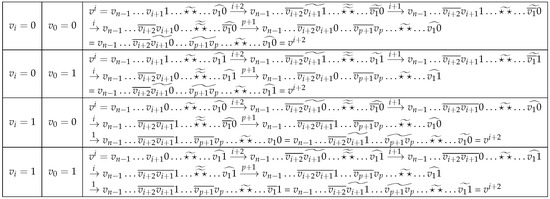

Lemma 12.

For any vertex with , and for .

Proof.

The shortest paths from to for are shown in Figure 12. □

Figure 12.

The shortest paths from to , where .

Proposition 4.

and .

Proof.

If , then and = . If , then and = . □

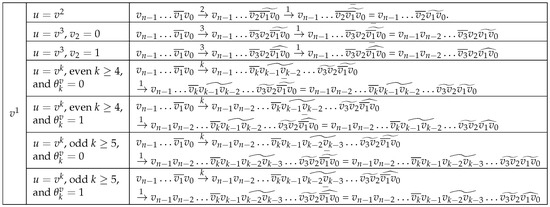

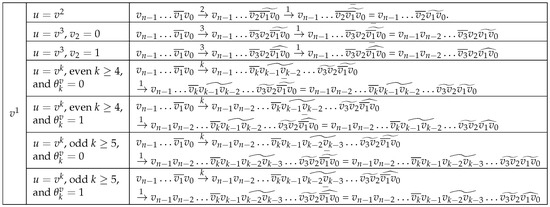

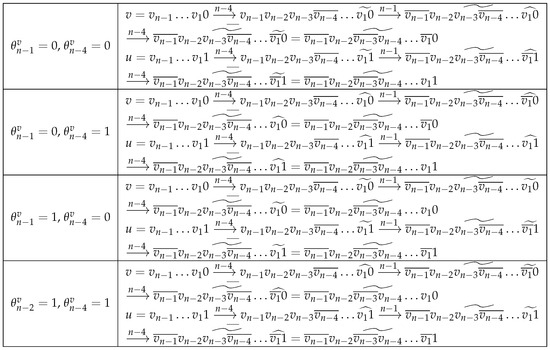

Lemma 13.

For any vertex with , for .

Proof.

The shortest paths from to for are shown in Figure 13. □

Figure 13.

The shortest paths from to , where .

Proposition 5.

and .

Proof.

If , then and = . If , then and = . □

Proposition 6.

, , , and .

Lemma 14.

For any vertex with , for .

Proof.

The shortest paths from to for are shown in Figure 14. □

Figure 14.

The shortest paths from to , where .

Proposition 7.

, , and .

Proof.

If , then , , and . If , then , , and . □

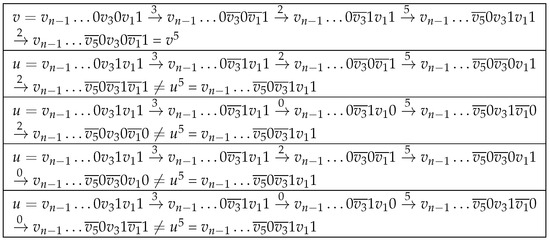

Lemma 15.

For any vertex with , for .

Proof.

The shortest paths from to for are shown in Figure 15. □

Figure 15.

The shortest paths from to , where .

Lemma 16.

For any vertex with , even , and . Let p be the largest position such that p is even, , and . Then,

Proof.

If , = ; otherwise, = . Assume that , . If no such p exists, then the shortest paths from to are shown in Figure 16; otherwise, please see Figure 17. Note that ★ could be an empty character in this lemma.

Figure 16.

The shortest paths from to when .

Figure 17.

The shortest paths from to when .

In the case that , p must exist and . The shortest paths from to are shown in Figure 18. □

Figure 18.

The shortest paths from to when .

Lemma 17.

For any vertex with , even and , .

Proof.

If and , then and . The shortest path from to is = = .

If and , then and . The shortest path from to is = = .

If and , then and . The shortest path from to is = = .

If and , then and . The shortest path from to is = = . □

Lemma 18.

For any vertex with , i is odd, and , .

Proof.

Assume that , . If , then = …. The shortest path from to is = . If , then = . The shortest path from to is … = ….

In the case that , . If , then = . The shortest path from to is = . If , then = . The shortest path from to is … = …. □

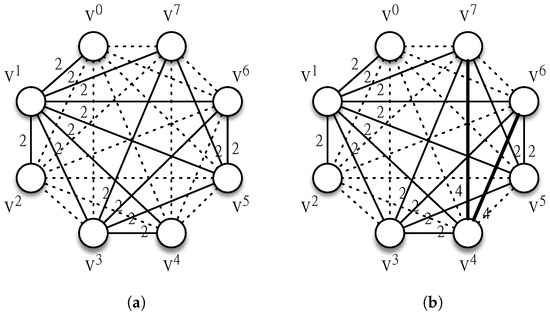

For example, for any vertex , Lemma 12 ensures that and for . Lemmas 13–15 imply that for , for , and for . Lemmas 17 and 18 establish that for even and , and for odd i and . Finally, Lemma 16 distinguishes the shortest paths for even and . As illustrated in Figure 19, we use solid lines, dashed lines, and thick lines to represent distances of 2, 3, and 4, respectively. Figure 19a,b show the shortest paths between the neighbors of vertices 00000000 and 00000100, excluding the vertices themselves.

Figure 19.

The shortest paths between the neighbors of vertices 00000000 and 00000100, excluding the vertices themselves. (a) The shortest paths between the neighbors of vertex 00000000. (b) The shortest paths between the neighbors of vertex 00000100.

Lemma 19.

Let ϕ be an automorphism of for . If for , then we have either and or and .

Proof.

For any vertex , consider the shortest paths between its neighbors. Lemmas 12–18 establish that vertices and are the only neighbors of v with a single 2-distance path and 3-distance paths to other neighbors. Thus, this lemma holds. □

Lemma 20.

Let ϕ be an automorphism of for odd . If for , then we have either and or and .

Proof.

Since n is odd, Lemmas 13, 15, and 18 imply that there are neighbors of v at a distance of 2 from both and , and these neighbors are distinct from the others. Therefore, if for , then either and , or and . □

Lemma 21.

Let ϕ be an automorphism of for . If for , then

- 1.

- for i is odd when n is even;

- 2.

- for is even when n is even;

- 3.

- for is odd when n is odd;

- 4.

- for is even when n is odd.

Proof.

For any vertex , consider the shortest paths between the neighbors of v. Lemmas 12 and 13 imply that neighbors of v have a distance of 2 from vertex . Lemmas 13 and 15 show that neighbors of v have a distance of 2 from vertex . Lemmas 13, 15, and 18 establish that neighbors of v have a distance of 2 from vertex for odd . Since all other distances are at least 3, these odd neighbors are distinct. Therefore, if for , then for all i is odd. Similarly, the numbers of 2-distance paths from , for even , to other neighbors are distinct. □

Proposition 8.

Proof.

If , then ; otherwise, . □

Lemma 22.

For , vertices and are in different orbits.

Proof.

Assume there exists an automorphism such that . Lemma 21 implies that and for even n, and either and or and for odd n.

For even n, we have = and = when , and = and = when . Figure 20 shows that = ≠ when and = = ≠ when .

Figure 20.

and .

For odd n, since ≠, we consider the case that = and = . We have = and = . Figure 21 represents = = ≠ when and = = ≠ when . These contradictions imply that no automorphism can map v to u, and therefore, vertices v and u are in different orbits. □

Figure 21.

and .

Lemma 23.

For , vertices and are in different orbits.

Proof.

Assume there exists an automorphism such that . Lemma 21 implies that and . Applying Lemma 19, we determine that is equal to , , , or . Figure 22 represents , , , , and . Thus, . Therefore, vertices and are in different orbits. □

Figure 22.

, , , , and .

Lemma 24.

For , vertices and are in different orbits.

Proof.

Assume there exists an automorphism such that . Lemma 21 implies that and . Figure 23 represents and . Thus, . Therefore, vertices and are in different orbits. □

Figure 23.

and .

Lemma 25.

For , vertices and are in different orbits.

Proof.

We consider the following four cases: (1) and , (2) and , (3) and , and (4) and . According to Lemma 16, and in case 1, and in case 2, and in case 3, and and in case 4. Since in cases 1 and 4, vertices v and u are in different orbits. According to Lemmas 23 and 24, vertices v and u are in different orbits in cases 2 and 3, respectively. □

Lemma 26.

For , vertices and are in different orbits, where is even.

Proof.

Let p be the largest even position such that and . If no such p exists, Lemma 16 implies that , and therefore, vertices v and u are in different orbits. Conversely, Lemma 21 implies that .

Figure 24 for (or Figure 25 for ) shows that for all possible and . Note that when , can be found in Figure 16. Consequently, . □

Figure 24.

The shortest paths from to when .

Figure 25.

The shortest paths from to when .

Lemma 27.

, , and for .

Proof.

As shown in Lemma 22, , and . Lemmas 22, 25, and 26 imply that for . □

Theorem 1.

Proof.

According to Lemmas 1, 11, and 27, this theorem holds. □

3. Conclusions

Liu, Lan, Chou, and Chen [3] demonstrated that for . Shiau, Wang, and Pai [5] proved that for . Liu [7] established that for odd and for even . In this paper, we show that if , and if . Future research could focus on determining the orbit numbers of other hypercube-like interconnection networks, such as extended crossed cubes, extended folded cubes, and mbius cubes.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No data were used for the research described in this article.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and the editor for their careful reviews and constructive suggestions to help us improve the quality of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Efe, K. A variation on the hypercube with lower diameter. IEEE Trans. Comput. 1991, 40, 1312–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efe, K. The crossed cube architecture for parallel computation. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 1992, 3, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-J.; Lan, J.K.; Chou, W.Y.; Chen, C. Constructing independent spanning trees for locally twisted cubes. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2011, 412, 2237–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulasinghe, P.; Bettayeb, S. Multiply-twisted hypercube with five or more dimensions is not vertex-transitive. Inf. Process. Lett. 1995, 53, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiau, T.-H.; Wang, Y.-L.; Pai, K.-J. The orbits of Crossed Cubes. Available online: https://scirate.com/arxiv/1707.06763 (accessed on 24 July 2017).

- Frucht, R. Herstellung von Graphen mit vorgegebener abstrakter Gruppe. Compos. Math. 1939, 6, 239–250. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.J. The Orbits of Folded Crossed Cubes. Comput. J. 2024, 67, 1719–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhao, L. The twisted-cube connected networks. J. Comput. Sci. Technol. 1999, 2, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Lin, X.; Pan, Y.; Jia, X. Optimal fault-tolerent embedding of paths in twisted cubes. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2007, 67, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Jia, X.; Lin, X. Embedding of cycles in twisted cubes with edge-pancyclic. Algorithmica 2008, 51, 264–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.-J.; Tsai, C.-H. Embedding a family of meshes into twisted cubes. Inf. Process. Lett. 2008, 108, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.-S.; Chang, M.-S.; Chen, D.-J. Efficient algorithms for reliability analysis of distributed computing systems. Inf. Sci. 1999, 117, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lu, L.; Zhou, S. Conditional diagnosability of twisted cube connected networks, In Proceedings of International Conference on Computer Science and Information Technology. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, Kunming, China, 27–28 December 2014; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Liu, Y. Almost Pancyclic Property of the Twisted-Cube Connected Network. Chin. J. Northeast. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 1999, 20, 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, J.F.G.; Jia, X. Independent spanning trees on twisted cubes. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2012, 72, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L. Reliability analysis of twisted cubes. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2018, 707, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liang, J.; Qi, D.; Lin, W. The twisted crossed cube. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2016, 28, 1507–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).