Abstract

With the growing prevalence of drone technology across various sectors, efficient and safe path planning has emerged as a critical research priority. Traditional Aquila Optimizers, while effective, face limitations such as uneven population initialization, a tendency to get trapped in local optima, and slow convergence rates. This study presents a multi-strategy fusion of the improved Aquila Optimizer, aiming to enhance its performance by integrating diverse optimization techniques, particularly in the context of path planning. Key enhancements include the integration of Bernoulli chaotic mapping to improve initial population diversity, a spiral stepping strategy to boost search precision and diversity, and a “stealing” mechanism from the Dung Beetle Optimization algorithm to enhance global search capabilities and convergence. Additionally, a nonlinear balance factor is employed to dynamically manage the exploration–exploitation trade-off, thereby increasing the optimization of speed and accuracy. The effectiveness of the mixed multi-strategy improved Aquila Optimizer is validated through simulations on benchmark test functions, CEC2017 complex functions, and path planning scenarios. Comparative analysis with seven other optimization algorithms reveals that the proposed method significantly improves both convergence speed and optimization accuracy. These findings highlight the potential of mixed multi-strategy improved Aquila Optimizer in advancing drone path planning performance, offering enhanced safety and efficiency.

Keywords:

multi-strategy integration; Aquila Optimizer; unmanned aerial vehicles path planning; optimization algorithm MSC:

90-05; 90-08; 90-10; 90-11

1. Introduction

In recent decades, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) have acquired a great potential to complete an autonomous or semi-autonomous mission. A growing number of applications have appeared in real-world environments [1,2]. Current research in UAV path planning has employed a variety of algorithms, including the artificial potential field method, heuristic search algorithms, neural network approaches, and various swarm intelligence algorithms such as ant colony optimization (ACO) [3], particle swarm optimization (PSO) [4], and bee colony optimization (BCO) [5]. However, traditional optimization techniques struggle to cope with the inherent computational demands of such problems. Their reliance on direct evaluations of the objective function, which can be prohibitively expensive, renders them impractical when dealing with high-dimensional spaces [6].

A popular field of study that has made great strides in resolving intractable optimization issues is metaheuristics. Major advances have been made since the first metaheuristic was proposed, and numerous new algorithms are still being proposed every day. There is no doubt that the studies in this field will continue to develop in the near future [7]. Among these, the Aquila Optimizer (AO) [8], a recently developed metaheuristic optimization algorithm, has attracted interest due to its unique search mechanism and strong optimization performance. Despite these advantages, the original AO struggles with common pitfalls in complex optimization tasks, including susceptibility to local optima and slow convergence rates. To address these shortcomings, several researchers have proposed modifications to improve AO performance. Gao et al. [9] propose an improved Aquila Optimizer (IAO) algorithm which improves the original AO algorithm via three strategies. First, in order to improve the optimization process, we introduce a search control factor (SCF) in which the absolute value decreases as the iteration progresses, improving the hunting strategies of AO. Secondly, the random opposition-based learning (ROBL) strategy is added to enhance the algorithm’s exploitation ability. Finally, the Gaussian mutation (GM) strategy is applied to improve the exploration phase. Huang et al. [10] improved a hybrid Aquila Optimizer (HAO) technique that uses crossover operators and Gaussian mapping. Using Gaussian mapping to establish the population, the initial population’s quality is enhanced. The crossover operator is then used to encourage information sharing within the population while maintaining population diversity in each iteration. This improves the algorithm’s ability to jump out of the local optimal and accelerates its global convergence. Wang et al. [11] enhanced an improved hybrid AO and Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO) combined with a nonlinear escaping energy parameter, and random opposition-based learning strategy is proposed, namely IHAOHHO, to improve the searching performance. Zhao et al. [12] simplified the Aquila Optimizer by discarding the position update strategy during exploitation and focusing exclusively on the search phase, streamlining the algorithm for better performance.

This paper suggests a mixed multi-strategy fusion-enhanced Aquila Optimizer (MMSIAO) that improves the optimization approach faults to produce an Aquila Optimizer with increased global optimization performance and resilience. The enhancements include a spiral stepping strategy to increase search accuracy and preserve population diversity, the use of Bernoulli chaotic mapping to increase the initial population diversity, and the addition of a stealing mechanism from the Dung Beetle Optimization algorithm to improve global search and convergence performance. Lastly, a nonlinear balancing factor method is used to govern the dynamic balance between exploration and exploitation, which further enhances the algorithm’s accuracy and speed of optimization. Optimization tests with CEC2017 complicated functions and benchmark test functions show the superiority of the improved MMSIAO. Its performance in UAV path planning situations demonstrates its efficacy in practical engineering optimization.

2. Related Work

The two main stages of the AO algorithm-structured architecture are scaling-up and scaling-down exploration and exploitation. The number of iterations dynamically controls the change between these stages. In particular, the algorithm gives priority to exploration when (where t is the current iteration and T is the total number of iterations). This is achieved by performing extensive searches throughout the solution space to find promising locations. Once the number of iterations exceeds , the algorithm moves into the exploitation phase, where it concentrates on locally improving solutions to speed up convergence toward the global optimum. This phased shift enhances convergence robustness and lowers the risk of getting stuck in local optima by striking a reasonable balance between exploration and exploitation.

2.1. Population Initialization

As part of building its mathematical model, the AO algorithm starts by initializing the placements of individuals within the population randomly. This initialization improves the algorithm’s capacity for exploration by guaranteeing that the search begins from a variety of locations within the solution space. The following mathematical expression governs the process:

In Equation (1), represents a randomly generated value within the range [0, 1]. The upper and lower bounds of the -th Aquila in the -th dimension are indicated by and , respectively. is the dimensionality of the search space, and is the population size. By guaranteeing that the starting points are evenly dispersed over the possible solution space, this formulation encourages diversity and strengthens the algorithm’s exploratory potential. The expression for its matrix X is as follows:

In Equation (2), indicates the search space’s dimension, while indicates the population size.

2.2. Expanding Exploratory Phase

During the first stage, the flock of Aquilas improves its search skills by flying to great altitudes and vigorously hunting in the air. The mathematical expression for this component is as follows:

In Equation (3), individual positions at the -th and -th iterations of the AO method are denoted by and , respectively. The finest individual discovered up to the -th iteration is indicated by the symbol , whereas controls the scope of the exploratory search. Furthermore, denotes the population average location at the -th iteration, where is the maximum number of iterations and t is the current iteration count. Throughout the optimization process, this formulation makes it easier to maintain a dynamic balance between exploration and exploitation. During the first stage, the flock of Aquilas improves its search skills by flying to great altitudes and vigorously hunting in the air.

2.3. Narrowing Exploration Phase

During the second stage, the Aquila flock forms a tight spiral above the prey when they detect it at a higher altitude. The Aquila can prepare and gain velocity before descending thanks to this habit, which also improves the accuracy of prey location. They take up positions for the attack as the spiral becomes tighter. The following is the relevant mathematical expression for this behavior:

In Equation (4), a randomly chosen member of the population is denoted by , whose value falls between . is a vector spanning from 1 to , with , , and . This formulation encapsulates the dynamics of the Aquila’s spiral flight behavior during its pursuit of prey. The expression for its is as follows:

In Equation (5), , , and are normally distributed.

2.4. Extended Development Phase

In the third stage, once the Aquila has completed its circling maneuver in preparation for an attack, it executes a vertical descent strategy. The corresponding mathematical formulation for this descent is expressed as follows:

In Equation (6), and represent the development adjustment parameters, both set to a value of 0.1.

2.5. Reduced Development Phase

In the last phase, the Aquila moves toward its victim and launches somewhat haphazard strikes. The following is the mathematical expression that governs the process of approaching and seizing the prey:

In Equation (7), the value of the mass function used to balance the search strategy is indicated by . The Aquila’s different movement patterns when tracking its prey are represented by , and the value of the linearly decreasing flight slope, which is limited within the range , is represented by .

3. Methodology

3.1. Bernoulli Chaotic Mapping Strategies

Traditional random initialization methods can result in uneven solution distributions, adversely impacting convergence speed and accuracy. In contrast, Bernoulli chaotic mapping [13], characterized by its simplicity and high uniformity, serves as an effective alternative to conventional random initialization. This approach enhances population diversity and, consequently, improves the algorithm’s overall performance. The corresponding mathematical model is as follows:

In Equation (8), the beginning value is set at , the control coefficient is assumed to be 0.4, and the chaotic value . The range is where the global solution is defined. Following Bernoulli chaotic mapping, the -th random number is mapped to the -th Aquila starting position. The first Aquila produced by mapping Formula (8) to Formula (1) starts at this location:

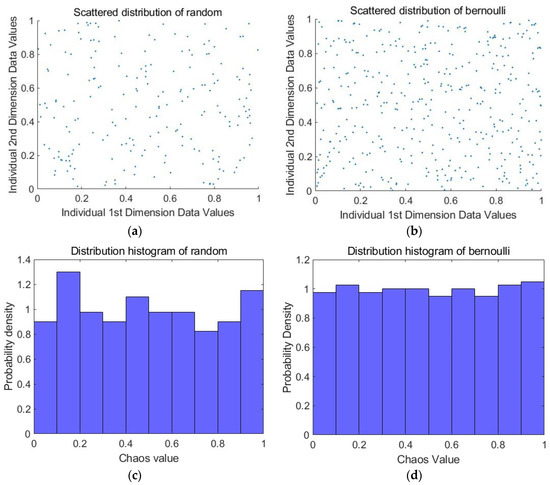

The scatterplot and histogram of the distribution of a two-dimensional initialized population of size 200 generated using Bernoulli chaotic mapping and random mapping, respectively, are shown in Figure 1. It is clear that the population of Aquila generated via Bernoulli chaotic mapping has a wider coverage of the solution space and a more uniform distribution, which increases population diversity.

Figure 1.

Distribution of population initialization: (a) scattered distribution of random; (b) scattered distribution of Bernoulli; (c) distribution histogram of random; (d) distribution histogram of Bernoulli.

3.2. Spiral Stepping Strategy

The approach combines population averaging, random population placement, and global optimization; however, iterations may lead to population assimilation, making it vulnerable to local optima. This study uses predation, spiral roaming, and contraction encirclement—three phenomena from the Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) [14]. With these improvements, the search space will be expanded to improve coverage and remove blind spots, while the search range will be reduced, and accuracy will be increased. This method improves the model and eventually promotes more population variety. The following is the presentation of the related mathematical formulation:

In Equation (10), the logarithmic spiral shape constant is denoted by , the random vectors and are restricted to the interval , and is a random number uniformly distributed throughout the interval . Whether the whale travels in a spiral path toward its prey or contracts its encirclement depends on the probability , which lies within the interval during this procedure.

3.3. Theft Strategies Incorporating Dung Beetle Optimization Algorithms

To overcome the difficulties of fully investigating local optima and the propensity to ignore global optima, this study incorporates the stealing method from the Dung Beetle Optimizer (DBO) [15]. The extreme randomness of the Levy flight step in the approach and several stochastic elements make these problems worse. The algorithm’s global search capabilities and convergence time are improved by incorporating aspects of randomness along with impacts from both local and global optimal positions. Additionally, the AO global optimal bootstrap is kept in place to make it easier for solution sets to share non-direct information. This method increases the accuracy and speed of late-stage convergence while reducing the effect of unpredictability on robustness. The following is the relevant mathematical formulation:

In Equation (11), is a constant set to 0.5, is the population optimal location for the current iteration, is the global optimal position, and is a random vector with a normal distribution.

3.4. Nonlinear Equilibrium Factor Strategy

Efficient metaheuristic algorithms must effectively balance exploration and exploitation to avoid local optima. The AO transitions between phases are based on a fixed number of iterations, which limits information exchange between phases and increases susceptibility to local optimality. A hybrid variational strategy that combines Laplace [16] and cosine transforms is introduced and dynamically adjusted with iterations. This approach aims to balance exploration and exploitation, enhance precocity, facilitate escape from local extremes, and ultimately improve the algorithm’s performance. The corresponding mathematical formulation is presented as follows:

In Equation (12), in the Laplace distribution , the parameters and are defined as , while the parameters η and μ are set to 3 and 0.08, respectively. The adaptive equalization algorithms’ global search and local development stages are made easier by substituting for the original switching constraint . This modification improves the algorithm’s adaptability and reactivity to different optimization environments. In order to promote information sharing and exchange, the value of drops nonlinearly with each iteration, promoting global search and effective exploration in the early phase while keeping the chance of local development low. The latter stage, on the other hand, places more emphasis on deep development and occasionally uses global searches to offset local optima. By successfully balancing exploration and exploitation, this nonlinear balancing technique improves the accuracy of the algorithm and the speed of optimization.

3.5. Time Complexity Analysiss

Time complexity analysis often depends on three processes: population initialization, fitness function computation, and population position update. The population size, the search space’s dimension Dim, and the maximum number of iterations T all play a role in it.

The overall computational complexity of the AO is or . The Spiral Stepping Strategy and Theft Strategies Incorporating Dung Beetle Optimization were used in the algorithm’s development phase, and the Bernoulli Chaotic Mapping Strategy was used to initialize the population in place of the original pseudo-random number technique in the improved MMSIAO. The position-updating method stays the same during the search phase, while algorithms in the development phase can replace the initial position-updating formula without making the algorithm more difficult. Consequently, the enhanced AO overall computational complexity remains at .

According to the analysis, the improvement technique does not provide additional time complexity, and the computational complexity of AO and MMSIAO is equal.

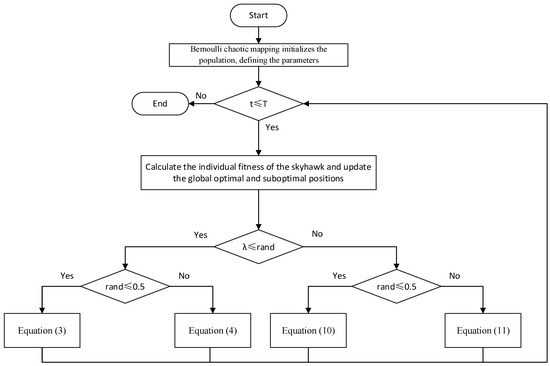

3.6. Overall Process of the Algorithm

Step 1: Establish the necessary parameters, such as the population size , the maximum number of iterations , the search dimension , and the search range, which is delineated by the upper and lower bounds and .

Step 2: Apply the Bernoulli chaotic mapping approach to initialize the population.

Step 3: Determine each individual’s level of fitness and choose the fittest individual.

Step 4: In the population update phase, the formulas are chosen for iterative optimization in compliance with the defined algorithmic procedure.

Step 5: Stop the algorithm and output the optimization results if the termination requirements are met; if not, move back to Step 3 to carry on with the execution (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flowchart of MMSIAO.

4. Experimental Results and Discussion

4.1. Benchmarking Function

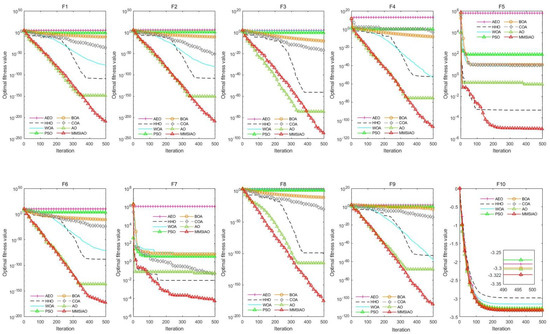

The Artificial Ecosystem Optimization Algorithm (AEO) [17], Harris Hawk Optimization Algorithm (HHO) [18], Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA), PSO, Butterfly Optimization Algorithm (BOA) [19], Chaos Optimization Algorithm (COA) [20], and the AO are among the seven optimization algorithms that were compared to verify the viability of the recently proposed MMSIAO. Each algorithm population size and iteration count were fixed at 30 and 500, respectively, after the initial parameter values. Ten benchmark functions were used: functions F1 through F5 are unimodal (UN) functions for testing the accuracy and speed of convergence, while functions F6 through F9 are multi-modal (MM), and F10 is a constant dimension (CD) function for testing the ability to search globally and avoid local optima. One hundred separate runs were performed in total (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Benchmarking functions.

According to the optimization findings shown in Table 2, the MMSIAO performed exceptionally well across the 10 benchmark test functions, showing notable benefits in both the UN and MM cases. In contrast to previous methods, MMSIAO approached the theoretical optimum with the best convergence accuracy and strong stability in UN functions. Additionally, in complex MM functions like F7, it maintained a low standard deviation and great convergence accuracy. MMSIAO on F9 not only searched the global optimum but also consistently had the fastest convergence rate. The standard deviation and average performance measures of MMSIAO significantly outperformed those of rival algorithms, suggesting that the suggested improvements successfully increased resilience and convergence accuracy, providing a viable solution for challenging optimization problems.

Table 2.

Comparison of optimization results of different swarm intelligence algorithms.

Figure 3 shows how well the MMSIAO performed when dealing with UN functions F1 through F4, avoiding the premature convergence problems that algorithms like the AEO face. MMSIAO continuously approached the theoretical optimum and showed fast and steady convergence characteristics. Even though it started off lagging behind the HHO for F5, it eventually overtook HHO and reached the best accuracy. MMSIAO and the original AO operated similarly at the beginning of F6 in the context of MM functions. But in the latter phases, MMSIAO kept moving forward without stalling, achieving the best accuracy on F7. MMSIAO exhibited the highest accuracy and the fastest rate of convergence in functions F8 and F9. With several inflection points out of local optimality and rapid convergence, MMSIAO exhibited strong robustness on F10. All things considered, these findings show that MMSIAO successfully strikes a compromise between exploration and exploitation in global optimization, avoiding local optima while producing better results.

Figure 3.

Adaptation graph for different swarm intelligence algorithms.

4.2. Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test

A nonparametric statistical technique that can identify more intricate data distributions is the Wilcoxon rank sum test. A p-value of less than 5% is a strong validation for rejecting the null hypothesis and showing that the two algorithms differ significantly. The significance level was set at 5%. NaN denotes no appreciable differences between the algorithms and the sample data. To show the substantial difference between the algorithms, the Wilcoxon rank sum test was applied to the best outcomes of the 30 separate runs of the MMSIAO and seven comparative algorithms in this study. The symbols “+/−/=” are used to show that MMSIAO performs better than, inferior to, or comparable to the comparison algorithms, respectively, based on the size of the p-value.

The p-value of the Wilcoxon rank sum test results of MMSIA0 was less than 5%, which indicates that the superiority of the MMSIAO algorithm is statistically significant. The results shown in Table 3 further confirm that MMSIAO has better optimization performance than the other algorithms.

Table 3.

Results of the Wilcoxon rank sum test for each algorithm.

4.3. CEC2017

This study used the 10 CEC2017 benchmark functions in Table 4 to better validate MMSIAO performance. These 10 functions are of UN, MM, hybrid (H), and composite (C) forms.

Table 4.

CEC2017 functions.

The findings show that MMSIAO performed exceptionally well on the hybrid function, exhibiting exceptional convergence accuracy and robustness, and achieving the ideal average solution accuracy on eight of the functions. MMSIAO maintained the second-highest accuracy despite being suboptimal on two functions. MMSIAO efficacy is demonstrated by its ability to successfully avoid local optimization in the example of the MM function CEC11. It performed better in accuracy than the COA on UN functions, although having somewhat less stability. All things considered, MMSIAO successfully overcomes the shortcomings of the original Aquila Optimizer and improves search efficacy and efficiency by combining high accuracy and stability across the majority of functions (see Table 5).

Table 5.

CEC2017 function optimization results.

To evaluate the competitiveness of the MMSIAO against other algorithms in a comprehensive and concise manner, the algorithms were ranked based on the mean absolute error MAE [21]. Table 6 presents the MAE values and rankings of all algorithms across the ten CEC2017 benchmark functions, accompanied by the mathematical formulation:

Table 6.

Ranking of MAE algorithms.

In Equation (13), denotes the number of functions, represents the average of the solution results for the -th function, and indicates the theoretical optimum of the -th function.

Table 6 shows that, when compared to all other algorithms, the MMISAO algorithm MAE ranks highest and has superior values. This outcome amply illustrates the stability and efficacy of the suggested algorithm.

4.4. UAV Path Planning Problem

There are several uses for UAV path planning in business, agriculture, and other domains. This subsection highlights the usefulness of the suggested MMSIAO algorithm by showing how it may be applied to path planning. The path planning problem is first mathematically represented, and then the UAV path is dynamically searched and resolved by utilizing MMSIAO optimality-seeking features.

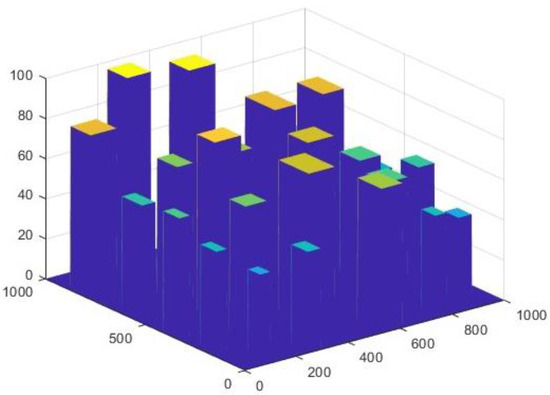

Building a mathematical model for obstacles is necessary in the UAV path planning system to accurately describe the motion state of the UAV and achieve efficient obstacle avoidance. In order to pinpoint the precise locations of obstacles in a 3D environment, spatial coordinates are generated at random. These coordinates are then given particular dimensional properties to provide a full 3D data representation of every barrier.

A 3D model of the surroundings is then created using a 3D matrix. According to this concept, an obstacle spatial extent is given a value of 1, designating it as a non-flyable area, while the other flyable areas are given values of 0. The evaluation of spatial relationships is made easier by this binary representation, which also makes processing subsequent algorithms easier. Finally, a landscape model with a noticeable 3D quality is produced by employing graphic drawing techniques to transform the interpolated terrain data into 3D space. Figure 4 displays the 3D model.

Figure 4.

Three-dimensional model.

Following the establishment of the mathematical model of the UAV trajectory, the main goal of UAV path planning is to determine the shortest route between the starting and end points. The trajectory of the UAV is represented by the series of points, , which connect the start point and the end point. The ideal points that satisfy the requirements for making decisions are included in this point sequence. The following formula is used to determine the cost of the UAV path length:

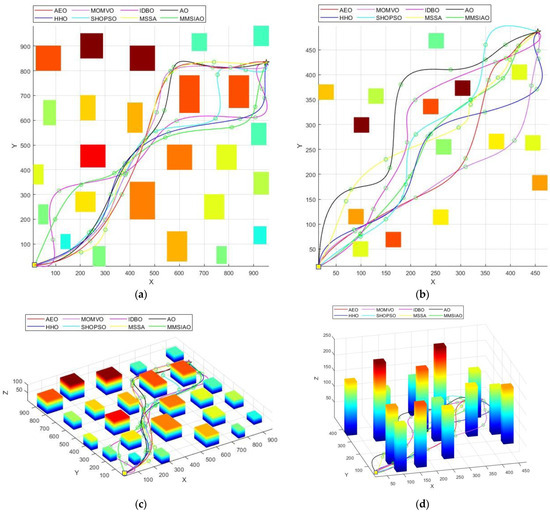

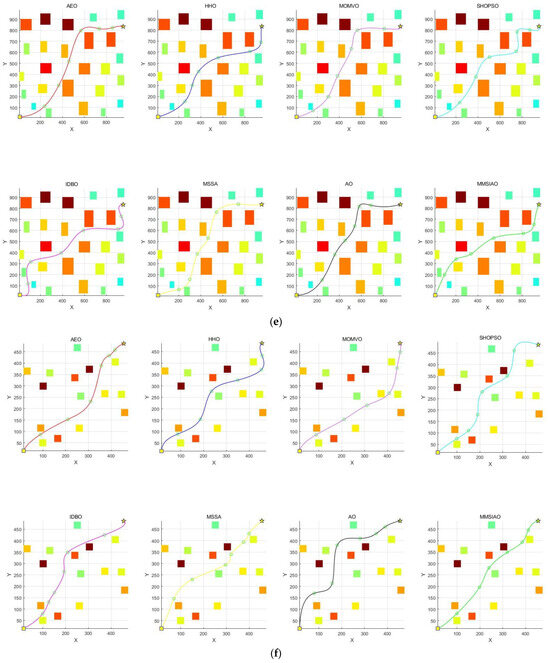

AEO, HHO, Multi-Objective Multi-Verse Optimizer (MOMVO) [22], combined with the selfish herd optimizer and particle swarm optimizer (SHOPSO) [23], multi-strategy Improved Dung Beetle Optimization (IDBO) algorithm [24], multi-strategy sparrow search algorithm (MSSA) [25], and AO, are chosen as comparison algorithms to execute path planning experiments with MMSIAO in two raster map environments to validate the effectiveness of the enhanced algorithm MMSIAO in UAV route planning in this study. The experiment parameters are standardized: Environment 1’s area is 1000 × 1000 × 120, and its start and end points are set as S = [15, 15, 15] and G = [951, 833, 15], respectively. Environment 2’s area is 500 × 500 × 250, and its start and end points are set as S = [480, 490, 20] and G = [10, 12, 20], respectively. The population size is N = 50, and the iteration number is T = 30. Figure 5 displays each algorithm’s path planning simulation within the relevant map context. The start point is represented by the square in the lower left corner, and the finish point is defined by the pentagram in the upper right corner.

Figure 5.

The path planning model is shown in the following views: (a) in two dimensions of Environment 1; (b) in two dimensions of Environment 2; (c) in three dimensions of Environment 1; (d) in three dimensions of Environment 2; (e) in a separate comparison of eight algorithms of Environment 1; (f) in a separate comparison of eight algorithms of Environment 2.

Figure 5 displays the outcomes of the path simulation for the two task contexts. It is evident from the figure that all eight algorithms can avoid environmental impediments on their way. AEO, HHO, MOMVO, SHOPSO, IDBO, MSSA, and AO have large fluctuations. It is important to note that MMSIAO designs a more stable route with mild variations and a reasonably stable route that keeps a safe distance from dangerous and hilly regions.

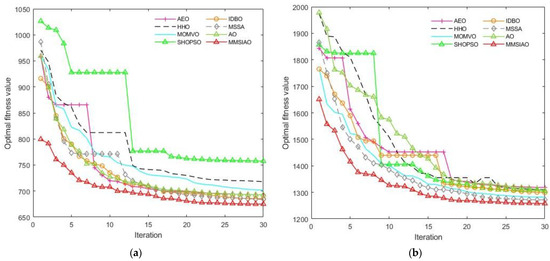

Figure 6 and Table 7 and Table 8 display the trajectory cost functions’ convergence charts. The four compared algorithms’ low solution quality and insufficiency in complex trajectory planning are confirmed by the significant variability of the trajectories they planned in Task Environment 1. The SHOPSO method reaches a local optimum during the iteration phase, as evidenced by the fact that it converges from the fourth iteration to the twelfth. Near the start of the iteration, AEO, HHO, MOMVO, IDBO, MSSA, and AO all drop quickly; but near the end of the iteration, they all settle into a local optimum. MMSIAO, on the other hand, finds the ideal value and achieves a desirable cost function value, suggesting that it is better able to avoid local optimality and identify the best course of action. It is evident in Task Environment 2 that practically every algorithm is rapidly reaching the ideal value. At the end of the iteration, MMSIAO continues to remove the local optimum, but its ultimate optimal fitness value is less than the fitness value of the comparison algorithms. This suggests that MMSIAO produces superior overall performance metrics and a reduced trajectory cost function.

Figure 6.

The model for path planning diagram of convergence. (a) Convergence diagram of the cost function in Environment 1; (b) convergence diagram of the cost function in Environment 2.

Table 7.

Experimental data of Environment 1.

Table 8.

Experimental data of Environment 2.

In order to more impartially assess how well MMSIAO performs in trajectory planning when compared to the other seven algorithms, the best, worst, and average values of the trajectory cost function values produced were calculated to allow one to assess each algorithm’s performance.

Table 9 shows that MMSIAO performs significantly better in both scenarios when it comes to the UAV trajectory planning challenge. The algorithm’s superior trajectory planning quality and improved solving stability are indicated by the fact that its mean value is lower than that of the other seven algorithms. In conclusion, this paper’s suggested enhancement mechanism can successfully raise the algorithm’s stability, accuracy, speed, and global search capabilities in trajectory planning. The approach performs exceptionally well when tackling intricate multi-constraint combinatorial optimization problems, such as three-dimensional trajectory planning for unmanned aerial vehicles, and accounts for both global search and local expansion capabilities.

Table 9.

Statistical data of experimental results.

5. Conclusions

By combining several methods, such as spiral stepping, Bernoulli chaotic mapping, the stealing strategy derived from the DBO, and a nonlinear equilibrium factor, MMSIAO improves upon the conventional AO. According to the experimental data, MMSIAO achieves faster convergence rates and improved optimization accuracy while drastically lowering the probability that the algorithm would converge to local optima. When compared to traditional methods, MMSIAO consistently finds the shortest path when solving the UAV path planning problem. In addition to providing a fresh method for planning UAV routes, this study presents creative approaches to solving challenging optimization problems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z. and T.B.; methodology, J.Z. and Y.L.; software, J.Z.; validation, J.Z., X.G. and T.C.; data curation, X.G.; writing—original draft, J.Z.; writing—review and editing, J.Z., Y.L. and T.B.; visualization, X.G. and T.C.; supervision, Y.L.; project administration, Y.L. and T.B.; funding acquisition, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Science Foundation of Hebei Natural Science Foundation (D2024107009).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request via the email of the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pitre, R.R.; Li, X.R.; Delbalzo, R. UAV route planning for joint search and track missions: An information-value approach. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2012, 48, 2551–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, X.M.; Li, Y. A survey of autonomous control for UAV. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computational Intelligence, Shanghai, China, 7–8 November 2009; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2009; Volume 2, pp. 267–271. [Google Scholar]

- Dorigo, M.; Birattari, M.; Stutzle, T. Ant colony optimization. IEEE Comput. Intell. Mag. 2006, 1, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle swarm optimization. In Proceedings of the ICNN’95-International Conference on Neural Networks, Perth, WA, Australia, 27 November–1 December 1995; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1995; Volume 4, pp. 1942–1948. [Google Scholar]

- Karaboga, D.; Basturk, B. A powerful and efficient algorithm for numerical function optimization: Artificial bee colony (ABC) algorithm. J. Glob. Optim. 2007, 39, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouhi, A.; Pira, E. A surrogate model-based Aquila optimizer for solving high-dimensional computationally expensive problems. J. Comput. Secur. 2024, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dokeroglu, T.; Sevinc, E.; Kucukyilmaz, T.; Cosar, A. A survey on new generation metaheuristic algorithms. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 137, 106040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abualigah, L.; Yousri, D.; Abd Elaziz, M.; Ewees, A.A.; Al-Qaness, M.A.; Gandomi, A.H. Aquila optimizer: A novel meta-heuristic optimization algorithm. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 157, 107250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Shi, Y.; Xu, F.; Xu, X. An improved Aquila optimizer based on search control factor and mutations. Processes 2022, 10, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Huang, J.; Jia, Y.; Xu, J. A hybrid Aquila optimizer and its K-means clustering optimization. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control 2023, 45, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Jia, H.; Abualigah, L.; Liu, Q.; Zheng, R. An improved hybrid Aquila optimizer and Harris Hawks algorithm for solving industrial engineering optimization problems. Processes 2021, 9, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Gao, Z.M.; Chen, H.F. The simplified Aquila optimization algorithm. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 22487–22515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuneda, A. Orthogonal chaotic binary sequences based on Bernoulli map and Walsh functions. Entropy 2019, 21, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Lewis, A. The whale optimization algorithm. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2016, 95, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Shen, B. Dung beetle optimizer: A new meta-heuristic algorithm for global optimization. J. Supercomput. 2023, 79, 7305–7336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, M.R. Laplace Transforms; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1965; p. 249. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z. Artificial ecosystem-based optimization: A novel nature-inspired meta-heuristic algorithm. Neural Comput. Appl. 2020, 32, 9383–9425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Zhao, K.; Wang, Y. A salp swarm algorithm based on Harris Eagle foraging strategy. Math. Comput. Simul. 2023, 203, 858–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Singh, S. Butterfly optimization algorithm: A novel approach for global optimization. Soft Comput. 2019, 23, 715–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, X.; Lian, W. A novel chaos optimization algorithm. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2017, 76, 17405–17436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmott, C.J.; Matsuura, K. Advantages of the mean absolute error (MAE) over the root mean square error (RMSE) in assessing average model performance. Clim. Res. 2005, 30, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarray, R.; Bouallègue, S. Multi-Verse Algorithm based Approach for Multi-criteria Path Planning of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2020, 11, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, G.; Liu, C.; Hu, P.; Li, H. A method of path planning for unmanned aerial vehicle based on the hybrid of selfish herd optimizer and particle swarm optimizer. Appl. Intell. 2022, 52, 16775–16798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, L.; Jiang, H.; Yang, F. Improved Dung Beetle Optimizer Algorithm with Multi-Strategy for global optimization and UAV 3D path planning. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 69240–69257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; He, Q.; Yang, L. UAV trajectory planning based on an improved sparrow optimization algorithm with multi-strategy integration. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1055807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).