Abstract

The reform of the teaching plan for the core course “big data technology and applications” in the digital economy major has become a globally recognized challenge. Qualitative data, fuzzy and uncertain information, a complex decision-making environment, and various impact factors create significant difficulties in formulating effective responses to teaching reform plans. Therefore, the objective of this paper is to develop a precision evaluation technology for teaching reform plans in the core course “big data technology and applications”, to address the challenges of uncertainty and fuzziness in complex decision-making environments. In this study, an extended VlseKriterijuska Optimizacija I Komoromisno Resenje (VIKOR) method based on a probabilistic uncertain linguistic term set (PULTS), which is presented for teaching reform plan evaluation. The extended probabilistic uncertain linguistic VIKOR method can effectively and accurately capture the fuzziness and uncertainty of complex decision-making processes. In addition, PULTS is integrated into the VIKOR method to express decision-makers’ fuzzy language preference information in terms of probability. A case study is conducted to verify and test the extended method, and the research results demonstrate that it is highly effective for decision-making regarding teaching reform plans to foster the high-quality development of education, especially in uncertain and fuzzy environments. Furthermore, parameter and comparative analyses verify the effectiveness of the extended method. Finally, the paper outlines directions for future research.

Keywords:

teaching reform plan evaluation; probabilistic uncertain linguistic term set; VIKOR; course; digital economy MSC:

90B50; 91B06; 28E10

1. Introduction

In recent years, with the rapid development of the global digital economy, there has been an increasing demand for high-end talents with interdisciplinary and data analysis abilities in society. In response to this trend, the higher education sector has proposed the concept of “New Humanities Construction”, aiming to cultivate composite talents with technical abilities, critical thinking, and social responsibility by integrating traditional humanities and modern technology disciplines [1]. As a core course in the field of digital economy, “big data technology and applications” has been given an important position in teaching reform. This course not only requires students to master the theory and technology of big data but also to possess interdisciplinary integration skills to cope with increasingly complex social and economic challenges [2].

Recently, scholars have conducted some discussions on the teaching mode and content of the course “big data technology and applications”. Zarouk et al. (2020) [3] proposed a teaching model based on the combination of flipped classroom and project-based learning, which they believed could enhance students’ self-learning and practical abilities. Chen et al. (2024) [4] studied the application of virtual laboratories in big data teaching and found that virtual experiments can provide students with more practical opportunities but also face the problem of insufficient interactivity. Li (2022) [5] further explored the integration of curriculum design with industry demands, pointing out that by introducing practical projects and industry cases, students can better understand the application of big data technology. Although these studies provide valuable experience and ideas for the reform of big data curriculum teaching, there are still some shortcomings in current research. Firstly, many studies lack systematic evaluation mechanisms, making it difficult to accurately track students’ learning processes and outcomes. Secondly, personalized teaching support in large-scale classrooms is relatively weak, making it difficult to meet the needs of different students. Thirdly, there is a certain lag between the course content and the rapidly developing industry demands, and the flexibility and foresight of course updates are insufficient [6].

In addition, teaching reform plan evaluation has the characteristic of incomplete information with issues that include conflict, fuzziness, uncertainty, etc. Especially in practice teaching management, the decision process becomes increasingly complex because it is usually made within the time range of human perception, with a lack of data and knowledge to deal with an uncertain environment [6,7]. Therefore, how to deal with teaching reform plan evaluation with fuzzy and uncertain information in a complex environment is a challenging issue of worldwide concern.

Teaching reform plan evaluation usually involves multiple criteria, various impact factors, semantic benefits, and limited alternatives, which can be modeled as a complex multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) problem. Fuzzy and uncertain decision-making methods have the advantages of handling fuzziness, uncertainty, and multidimensional evaluation and can provide a multi-criteria, refined evaluation tool for teaching reform plans to accurately depict how much semantic information is “good” or “bad”. The objective of this paper is to develop a precision evaluation technology for teaching reform plans in the core course “big data technology and applications” to address the challenges of uncertainty and fuzziness in decision-making in order to foster the high-quality development of education. The main goal is to enhance the accuracy and effectiveness of multi-criteria evaluations in a complex decision-making environment characterized by fuzziness and uncertainty by using an extended VlseKriterijuska Optimizacija I Komoromisno Resenje (VIKOR) method integrated with probabilistic uncertain linguistic term sets (PULTSs). To assist DMs in addressing the problems of teaching reform plan evaluation with fuzzy and uncertain information during a complex environment, the motivation for this study stems from the urgent need to support decision-makers in effectively addressing the challenges of evaluating teaching reform plans under fuzzy and uncertain conditions in a highly complex decision-making environment. This research aims to advance the field by developing an extended VIKOR method, enhanced with PULTSs, to establish a scientifically grounded technology that ensures precision, effectiveness, and adaptability in evaluating teaching reform plans for the core course “big data technology and applications” in the digital economy major. The contributions are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- An extended probabilistic uncertain linguistic VIKOR method is presented to evaluate the teaching reform plan for the core course “big data technology and applications” in the digital economy major. This method can reflect the fuzziness and uncertainty of complex decision processes more effectively and accurately.

- (2)

- The PULTS is imported into the VIKOR method to accurately depict the fuzziness and uncertainty of the research object, which can accurately express DMs’ fuzzy language preference information in terms of probability.

- (3)

- A case study of teaching reform plan evaluation under the background of the construction of new liberal arts is designed to verify the extended method.

- (4)

- The parameter analysis and comparative analysis further verify the effectiveness of the extended method.

The structure of this work is as follows. Section 2 introduces the related research. Section 3 describes some preliminaries of linguistic term sets (LTSs), PLTS, PULTS, and the VIKOR method. In Section 4, an extended probabilistic uncertain linguistic VIKOR method is proposed; additionally, the detailed calculation process is given. In Section 5, a case study of teaching reform plan evaluation under the background of the construction of new liberal arts is designed to verify the extended method. Finally, Section 6 concludes this study.

2. Related Work

With the rapid development of the digital economy, the concept of new liberal arts construction has gradually entered the field of higher education, promoting the deep integration of traditional disciplines and modern technology. In this context, the core course of “big data technology and applications” in the digital economy major has become an important object of teaching reform. Researchers have explored the teaching methods, content settings, and technological innovations of this course [8]. In terms of teaching methods, flipped classrooms and project-based learning have become the core directions of teaching reform in the course of “big data technology and applications”. Saltz and Heckman (2015) [9] explored the application of project-based learning in big data courses, using practical projects to help students master big data technology and cultivate their practical abilities. In terms of teaching objectives, He (2022) [10], based on big data technology, developed a learning analytic model for Japanese blended online and offline teaching, aiming to improve teaching objectives quality through data collection, analysis, and visualization. However, the model faces challenges such as insufficient interactivity, the complexity of non-linear learning characteristics, and reliance on data quality; therefore, the teaching objectives need to be further optimized and validated. In terms of learning experience, Wu et al. (2022) [11] proposed a big data-based precision teaching mode to enhance teaching quality and drive educational reform and demonstrated its effectiveness in improving student satisfaction and learning efficiency. However, the mode relied on frequent online and offline interactions, which could pose challenges for implementation in courses with limited resources or large student groups. In terms of improving the ability of teachers, Cai (2023) [12] indicated that the era of big data teaching has put forward higher requirements for teachers’ technical level. Especially with the increasing complexity of course content, teachers must constantly learn new technologies to meet teaching needs. However, there is still a lack of systematic empirical research support on how to balance the allocation of basic content and cutting-edge technology in teaching.

Although research on the teaching and reform of big data courses has made some progress, especially in terms of teaching methods, learning experience, and teacher training, the teaching reform plan evaluation usually involves multiple criteria or attributes, limited solutions, and semantic benefits [13]. It can be modeled as an MCDM problem with the goal of optimizing resource allocation. The existing research usually does not consider the factors of fuzzy information and uncertain complex environments. Real decision processes are usually very complex, as decisions are often made under pressure with a lack of necessary information, under subjective understandings of the evaluation object, and in the context of complex and intricate systems [7]. Fuzzy decision-making methods can evaluate changes in the demand of the education industry in real time by constructing a fuzzy reasoning system and making reasonable adjustments to course content to maintain the forward-looking and practical nature of the course. In addition, some of the attributes are difficult to quantify with precise numbers [14]. Therefore, the concept of fuzzy sets was proposed by Zadeh (1965) [15]; subsequently, it has witnessed continued development. Atanassov (1986) [16] proposed the intuitionistic fuzzy sets and expanded their applications. Yang et al. (2017) [17] proposed hesitant multiplicative sets for clustering analysis. Wang et al. (2019) [18] expanded intuitionistic fuzzy sets application for clustering algorithms. Mahmood et al. (2019) [19] presented an approach by using the concept of spherical fuzzy sets for decision-making and medical diagnosis problems. Song et al. (2020) [20] presented a dynamic hesitant fuzzy Bayesian network for the decision-making problem of optimal investment in ports. Mahmood et al. (2021) [21], based on the concept of a t-spherical fuzzy set, proposed the technique of generalized MULTIMOORA method and Dombi prioritized weighted aggregation operators. When people are evaluating several complex problems, such as the investment risk of an opportunity, they tend to use language terms such as “low”, “medium”, and “high” to express their opinions and attitudes [22]. In practical problems, a linguistic variable is a good assistant tool for DMs to express qualitative views [23]. However, in some cases, it is very difficult to express qualitative opinions only through LTSs. For example, when experts are evaluating the “good” or “bad” degree of teaching reform plans, one expert might consider it “good,” but the expert may not be sure how good it is. For this scenario, Pang et al. (2016) [24] proposed the PLTS, which can precisely express this type of qualitative opinions or preference information with probability degrees in the LTSs.

Since the PLTS was proposed in 2016 to handle qualitative information to realize calculation with expressions, it has received significant attention. In a short period of seven years, fruitful results have been achieved through its applications. Gou and Xu (2016) [25] proposed some basic operational laws for the PLTS. Chen et al. (2016) [26] presented a proportional hesitant fuzzy LTS for group decision-making problems. Kobina et al. (2017) [27] developed probabilistic linguistic power aggregation operators. Liu and You (2017) [28] proposed a probabilistic linguistic TODIM method. Farhadinia and Xu (2018) [29], based on the PLTS, proposed an ordered weighted hesitant fuzzy information fusion-based method. Cheng et al. (2018) [30] proposed a venture capital method for group decision-making under a probabilistic linguistic environment. Lin et al. (2019) [31] developed an extended ELECTRE II approach for PLTSs. Feng et al. (2019) [32], based on possibility degree comparison, developed a probabilistic linguistic QUALIFLEX method. Wu and Xu (2020) [33], based on a PLTS, proposed a hybrid TODIM method for urban epidemic situation evaluation. Liao et al. (2020) [34] presented a survey of probabilistic linguistic information decision-making methods. Saha et al. (2021) [35] proposed the hybridizations of generalized Dombi operators and Bonferroni mean operators under a dual probabilistic linguistic environment for group decision-making. Wang and Xu (2023) [36] applied the probabilistic linguistic terms with weakened hedges to express players’ strategies for risk allocation in a PPP project. Niu et al. (2024) [37] proposed a large-scale group decision-making method based on multi-granular probabilistic linguistic preference relations. Therefore, PLTSs can be considered a research hotspot, which is worthy of further study and exploration.

The fuzziness and uncertainty of real decision-making problems and various complex factors make it more and more difficult for DMs to indicate their preferences with crisp values. To effectively deal with the MCDM problem in different fuzzy situations, some extensions of the VIKOR method have been proposed, such as the triangular fuzzy VIKOR method [38,39], the intuitionistic fuzzy VIKOR method [40], the hesitant fuzzy VIKOR method [41], the probabilistic linguistic VIKOR method [42], and the extended VIKOR based on interval-valued intuitionistic fuzzy sets [43]. In this article, based on the hot issue of research on PLTSs, the uncertain linguistic variables, proposed by Xu (2006) [44], are applied to extend the PLTS and VIKOR approach, which is one of the classical MCDM methods. So, this study presents an extended probabilistic uncertain linguistic VIKOR method to evaluate the teaching reform plan for the core course “big data technology and applications” in the digital economy major, which can reflect the fuzziness and uncertainty more efficiently and accurately.

3. Preliminaries

Here, some concepts and methods of LTS, PLTS, PULTS, and the VIKOR method are introduced.

3.1. Linguistic Term Set

An LTS, based on linguistic decision-making, can be used to express opinions and views on the considered objects [45]. Let be a set of language terms, where is a positive integer, and and indicate the lower limit and upper limit of the LTS, respectively. The LTS has the following characteristics [31]:

- (1)

- If , then .

- (2)

- If , then .

3.2. Probabilistic Linguistic Term Set

Based on the LTS, the PLTS is defined and given by Pang et al. (2016) [24]:

where represents the linguistic term associated with probability , and is the number of different linguistic terms in .

Note that

- (1)

- If , then the PLTS has the complete probabilistic information of all possible linguistic terms;

- (2)

- If , then the PLTS has partial probabilistic information;

- (3)

- If , then the PLTS has completely unknown probabilistic information.

In addition, the detailed process for the normalization of the PLTS and the comparison between PLTSs can be obtained based on Pang et al. (2016) [24].

The PLTS is a key tool for evaluating teaching reform plans, especially under conditions of uncertainty and fuzziness. By integrating probabilistic information into linguistic term sets, the PLTS enables decision-makers to more accurately express subtle preferences and capture the inherent fuzziness and uncertainty in evaluating multidimensional educational reform plans. Its application integrates complex qualitative and quantitative data into a coherent framework by accommodating different expert opinions to enhance the rigorism of MCDM methods.

3.3. Probabilistic Uncertain Linguistic Term Set

Some preliminary explorations have been reported about the concepts, such as normalization and application under a probabilistic uncertain linguistic environment for group decision-making [46,47,48]. In this study, based on the PLTS, the definition, normalization process, and comparison method of PULTS are presented below.

Due to the uncertainty of the decision environment and the fuzziness of human preferences, it is very difficult for DMs to express an accurate assessment using only one linguistic term. Therefore, the uncertain linguistic variables are introduced by Xu (2004) [49] as follows:

Definition 1

([49]). Let , where . If and and indicate the lower and upper limits, respectively, then is called an uncertain linguistic variable.

3.3.1. Definition of PULTS

Definition 2.

Based on the LTS, and the uncertain linguistic variables proposed by Xu (2004) [49]; let be a PULTS, which can be defined as

where represents the uncertain linguistic term associated with probability ; is the k-th uncertain linguistic term in ; is the number of different uncertain linguistic terms in ; and and indicate the lower and upper limits, respectively, and .

Note that

- (1)

- If , then the PULTS has the complete probabilistic information of all possible uncertain linguistic terms;

- (2)

- If , then the PULTS has partial probabilistic information;

- (3)

- If , then the PULTS has completely unknown probabilistic information.

The PULTS plays a critical role in addressing the complexities of teaching reform plan evaluation by enabling a precise representation of fuzzy and uncertain information in decision-making. Unlike traditional linguistic term sets, the PULTS incorporates probability distributions to express decision-makers’ varying degrees of confidence in their assessments, allowing for a more nuanced and accurate evaluation of multidimensional criteria. Its integration with advanced methods like the VIKOR framework further enhances its capability to synthesize qualitative and quantitative factors to ensure robust and scientifically validated outcomes. This makes the PULTS an indispensable tool for navigating complex educational reforms, which can offer adaptability, precision, and methodological depth in optimizing teaching strategies within fuzziness and uncertain environments.

3.3.2. Comparison Between PULTSs

The score and deviation degree of PULTSs and the distance between PULTSs are defined as follows:

Definition 3.

Let be a PULTS and and are the lower and upper limits of , respectively. Then, the score of can be defined as follows:

where . If all the elements in are arranged according to the values of in descending order, then is called an ordered PULTS.

For any two PULTSs, and

- (1)

- If , denoted by ;

- (2)

- If , denoted by ;

- (3)

- If , then these two PULTSs cannot be distinguished. In this situation, the deviation degree of a PULTS can be further defined.

Definition 4.

Let be a PULTS, and are the lower and upper limits of , respectively, and . Then, the deviation degree of can be defined as follows:

For any two PULTSs, and with

- (1)

- If , then ;

- (2)

- If , then ;

- (3)

- If , then and are the same, denoted by.

Example 1.

Assuming there are two PULTSs, they are, respectively, and . Then, according to the formula for the score of PULTS, it can be easily obtained as . Furthermore, the values of their deviation degree are easily calculated for and as and , respectively. Obviously, ; therefore,

3.3.3. Normalization of PULTS

The normalization of the PULTS is as follows.

Definition 5.

Let be a PULTS, and . Then, the normalized PULTS can be defined as follows:

where , for all .

Let where be any two PULTSs, then the normalization process can be calculated as follows:

- (1)

- If , then based on Formula (6), where can be calculated easily, respectively.

- (2)

- If , then some elements should be added to the smaller number of elements. In other words, If , then uncertain linguistic terms need to be added to , which would make their cardinalities equal. The added uncertain linguistic terms should be the smallest subscript in , and their probabilities should be zero.

Example 2.

Given two PULTSs, and

- (1)

- According to the definition, the result can be obtained after the initial normalization: and .

- (2)

- Since , an element associated with probability 0 should be added to and finally, it can be easily obtained: .

3.4. The VIKOR Method

MCDM is the research of some approaches and procedures applied in management processes, which usually involve multiple criteria, limited alternatives, and multiple expert opinions [50]. The VIKOR method, proposed by Opricovic in 1998 [51], is one of the MCDM methods, focusing on the multiple criteria scheduling problem based on the “closeness” measure of the ideal solution [52]. Opricovic and Tzeng (2007) [53] presented an extended VIKOR method in comparison with outranking methods for promoting more applications. The details of the VIKOR method are as follows:

For an MCDM problem, let be a finite number of alternatives and be a set of evaluation criteria. indicates the crisp values of the evaluation alternative with respect to criterion , and indicates the weight with respect to criterion . The detailed calculation steps of the traditional VIKOR method are summarized below [54].

Step 1: Identify the decision-matrix .

Step 2: Generate the normalized decision matrix . The normalized decision matrix can be generated, based on the normalization formula as follows:

Step 3: Calculate the criteria weights. Here, the criteria weights can be obtained according to the analytic hierarchy process [55] proposed by Saaty (1980) [56].

Step 4: Determine the positive ideal solution (PIS) :

and the negative ideal solution (NIS) :

where the sets of are the benefit criteria, and the sets of are the cost criteria.

Step 5: Calculate metric distance measure over alternatives as

where indicates the weight with respect to criterion . If , the distance is the Hamming distance. If , it is the Euclidean distance. The value of can be determined based on the decision-makers’ professional expertise and knowledge background related to the decision-making problem in order to ensure a scientifically grounded approach to distance measurement in the evaluation process.

Step 6: Calculate the value of group utility :

and calculate the value of individual regret :

Step 7: Determine the value of the compromise solution :

where is the compromise coefficient. When approaches 1, it indicates that the decision outcome tends toward maximizing the group’s utility value. When approaches 0, it indicates that the decision outcome tends toward minimizing individual regret values. Typically, is set to 0.5, which represents a decision-making mechanism that balances the importance of achieving maximum group utility and minimizing individual regret equally through negotiation.

Step 8: Ranking of alternatives.

The value measures the distance between the evaluation values of each alternative and the positive ideal solution. The smaller the value of is, the better the candidate alternative is.

Step 9: Identify the compromise solution.

Through Equations (10)–(12), the ranking of alternatives can be calculated according to the decreasing order of , and , respectively. The best ranking can be identified if the following two conditions are satisfied:

Condition 1.

Acceptable conditions:

Condition 2.

Acceptable stability in decision-making: The alternative should also be the best alternative with the first position of the ranking produced by and/or

If Condition 1 is not satisfied, then the alternatives are the set of compromise solutions where the maximum value of can be obtained by the following relation: . If Condition 2 is not satisfied, then both alternatives and are the compromise solutions.

4. Probabilistic Uncertain Linguistic VIKOR Method

For an MCDM problem with PULTSs, let be a finite number of alternatives and be a set of the evaluation criteria. indicates the values of the evaluation alternative with respect to criterion , and indicates the weight with respect to criterion . The detailed calculation steps of the probabilistic uncertain linguistic VIKOR method are summarized below.

Step 1: Establish the probabilistic uncertain linguistic decision matrix . The decision matrix can be constructed according to the PULTS .

Step 2: Generate the normalized probabilistic uncertain linguistic decision matrix . The normalized decision matrix consists of two steps:

- (1)

- The normalization of criteria.

- (2)

- The normalization of PULTS. The normalization of PULTS is presented in Section 3.3.3.

Step 3: Calculate the criteria weights. Here, the criteria weights can be obtained according to the analytic hierarchy process proposed [55] by Saaty (1980) [56].

Step 4: Obtain the PIS :

and the NIS :

where the sets of are the benefit criteria, and the sets of are the cost criteria.

Step 5: Calculate metric distance measure over alternatives as

where indicates the weight with respect to criterion . If , the distance is the Hamming distance. If , it is the Euclidean distance. The value of can be determined based on the decision-makers’ professional expertise and knowledge background related to the decision-making problem in order to ensure a scientifically grounded approach to distance measurement in the evaluation process.

Step 6: Calculate the value of group utility :

and calculate the value of individual regret :

Step 7: Determine the value of the compromise solution :

where is the compromise coefficient. When approaches 1, it indicates that the decision outcome tends toward maximizing the group’s utility value. When approaches 0, it indicates that the decision outcome tends toward minimizing individual regret values. Typically, is set to 0.5, which represents a decision-making mechanism that balances the importance of achieving maximum group utility and minimizing individual regret equally through negotiation.

Step 8: Ranking of alternatives.

The value measures the distance between the evaluation values of each alternative and the positive ideal solution. The smaller the value of is, the better the candidate alternative is.

Step 9: Identify the compromise solution.

Let value be ranked from small to large, where . corresponds to the evaluation value of the alternative . The corresponding group utility value and individual regret value are and , respectively. The best solution or a set of compromise solutions can be obtained by the following criteria:

Criterion 1.

If the following four conditions hold simultaneously, where

then is the most stable optimal scheme. If the four conditions do not hold simultaneously, then is not the most stable optimal scheme. The best compromise solution can be identified according to the following criterion 2.

Criterion 2.

The best compromise solution can be identified as follows:

- (a)

- If the following conditions hold simultaneously, wherethen both alternatives where is the set of compromise solutions.

- (b)

- If the following conditions hold simultaneously, wherethen the alternatives is the compromise solution where the maximum value can be obtained by the following relation: .

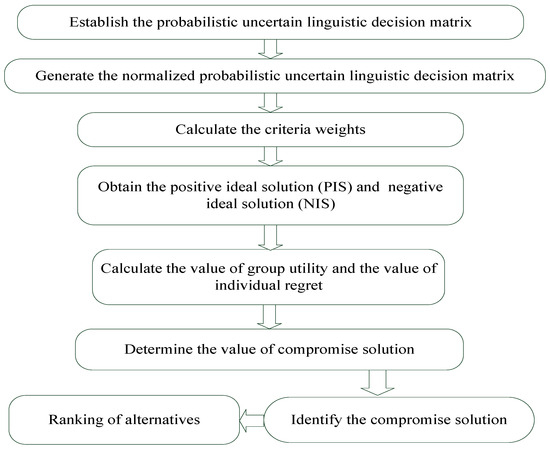

The flowchart of the probabilistic uncertain linguistic VIKOR method is presented in Figure 1. The PULTS exhibits exceptional adaptability and integration potential with advanced decision-making methodologies, such as VIKOR, which can enable a scientifically rigorous and systematic framework for optimizing teaching strategies. Its application is particularly impactful in addressing uncertainty, fuzziness, and the inherent complexity of decision-making processes within the multifaceted context of educational reform.

Figure 1.

The flowchart of the probabilistic uncertain linguistic VIKOR method.

5. Case Study of Teaching Reform Plan Evaluation

5.1. Case Analysis

In the context of the construction of new liberal arts, the teaching reform of the core course “big data technology and applications” in the digital economy major is particularly crucial. However, the process of evaluating the effectiveness of teaching reform usually involves the handling of complex information such as uncertainty, ambiguity, and semantic variables. This not only requires a scientific and reasonable evaluation of the achievements of the reform but also the introduction of diversified evaluation methods to cope with the complexity of information and diverse teaching needs, thereby ensuring the effectiveness and continuous optimization of teaching reform. To address these issues, fuzzy decision-making and probabilistic linguistic terms can provide an effective solution. Fuzzy decision-making methods have the advantages of handling uncertainty and multidimensional evaluation and can provide dynamic and refined evaluation techniques for teaching reform. The probabilistic linguistic terms can more accurately describe students’ learning status and needs through fuzzy evaluation models, providing strong support for teachers’ teaching adjustments. Decision-making processes have become increasingly complex due to the uncertain and fuzzy information environment, adding more difficulties and challenges. In this study, based on the PULTS, an extended VIKOR method is presented to evaluate the teaching reform plan under the background of the construction of new liberal arts. Compared with traditional evaluation methods, the method proposed in this article can provide more accurate personalized support to students in complex teaching environments, and provide a scientific basis for the dynamic adjustment of course content by optimizing teaching effectiveness to meet the needs of personalized education for students in order to foster the high-quality development of education. The detailed assessment process is described below.

An example is given to illustrate and verify the effectiveness of the extended method. Four teaching reform plans are selected, and the problems of the teaching reform plan evaluation of the core course “big data technology and applications” in the digital economy major are assessed based on the PULTS according to the following five criteria: (1) : achievement of teaching objectives; (2) : effectiveness of teaching methods; (3) : teaching competency of faculty; (4) : learning experience of students; and (5) : sustainability of teaching reform. Obviously, , , , , and are all benefit types for the evaluation of the teaching reform plan for the core course “big data technology and applications” in the digital economy major.

The detailed processes are described below.

Step 1: Establish the probabilistic uncertain linguistic decision matrix. To evaluate the four teaching reform plans of the core course “big data technology and applications” in the digital economy major, the evaluation information can be obtained according to the PUTLS based on the following LTS: . Table 1 presents the original evaluation information. Here, to further demonstrate how uncertainty and fuzziness are integrated into the complex decision-making process of teaching reform plan evaluation, a PULTS example is provided for illustration. For instance, indicates that one expert evaluates this teaching reform plan with a probability of 0.6 falling between “general” and “good”, and a probability of 0.4 falling between “good” and “very good”.

Table 1.

The probabilistic uncertain linguistic decision matrix.

Step 2: Generate the normalized decision matrix. The normalization process is relatively simple, and the criteria values can be obtained, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The normalized decision matrix.

Step 3: Calculate the criteria weights. The criteria weights can be obtained according to the analytic hierarchy process [55] proposed by Saaty (1980) [56], which is presented in Table 3. The pair-wise comparison matrix, induced by DMs based on their expertise and experiences, is given in Table 4.

Table 3.

The criteria weights.

Table 4.

The pair-wise comparison matrix.

Step 4: Obtain the PIS and the NIS .

According to Equations (14) and (15), the PIS and the NIS can be easily obtained as follows:

Step 5: Calculate the value of group utility , the value of individual regret , and the value of the compromise solution .

According to Equations (16)–(19), based on the score of the PULTS and the normalization process, the value of group utility , the value of individual regret , and the value of the compromise solution with a different can be obtained, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

The values of , , and with different .

Step 6: Rank the alternatives.

The identification of the optimal scheme is grounded in the fundamental principles of the VIKOR method. As previously discussed, the evaluation process demonstrates that a smaller value of the compromise solution corresponds to a superior candidate alternative, highlighting the method’s precision and effectiveness in resolving complex decision-making challenges under uncertainty and fuzziness. Furthermore, according to Criterion 1 and Criterion 2, the optimal solution can be easily identified. So, the best alternative is .

5.2. Parameter Analysis and Comparative Analysis

5.2.1. Parameter Analysis

The best solution can be easily obtained according to research results by the extended method. As a general rule, the compromise coefficient is set to 0.5, which signifies a decision-making mechanism that equally balances the importance of maximizing group utility and minimizing individual regret through negotiation. In this paper, a parameter analysis of is reported in Table 5. The most representative values are selected to conduct the analysis in order to further verify the effectiveness of the extended method for teaching reform plan evaluation. In Table 5, it is quite obvious that the values of the evaluation results with are both . The values of with are . The best alternative is .

Most importantly, the four conditions of Criterion 1 hold simultaneously, when the parameter is equal to 0.25, 0.50, and 0.75.

When ,

When ,

That is to say corresponds to the alternative , which is the most stable optimal scheme. This further verifies the effectiveness of the extended VIKOR method for the teaching reform plan evaluation.

5.2.2. Comparative Analysis

In order to minimize the potential impact of the compromise coefficient on the results, this paper further develops a TOPSIS with the PULTS method for comparative analysis to validate the extended method. The TOPSIS method, one of the classic MCDM methods, can rank alternatives over multi-criteria by minimizing the distance to the PIS and maximizing the distance to the NIS [57]. The specific evaluation processes of the TOPSIS with the PULTS method are given below.

Step 1: Establish the probabilistic uncertain linguistic decision matrix based on the PULTS.

Step 2: Generate the normalized probabilistic uncertain linguistic decision matrix .

Step 3: Obtain the weighted normalized probabilistic uncertain linguistic decision matrix. The criteria weights are obtained according to the analytic hierarchy process [55] proposed by Saaty (1980) [56].

Step 4: Determine the PIS and the NIS based on the PULTS.

Step 5: Compute the distance of each alternative from the PIS and the NIS based on the score of PULTS.

Step 6: Obtain the relative closeness to the ideal solution.

Step 7: Rank the alternatives. A larger relative closeness indicates a better alternative.

According to the above steps, the relative closeness of each alternative can be obtained easily, as presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

The relative closeness of each alternative.

From Table 6, it is obvious that the ranking results of , , , are 1, 3, 4, 2, which is the same as the evaluation results using the probabilistic uncertain linguistic VIKOR method with parameter analysis . The comparative analysis further verifies the effectiveness of the extended VIKOR method for teaching reform plan evaluation.

The teaching reform plan evaluation is an extremely complex process because of the intricacy of systems, the complexity of decision processes, the uncertainty, and the fuzzy information environment. Based on the above considerations, this paper proposes an extended probabilistic uncertain linguistic VIKOR method to evaluate teaching reform plans for the core course “big data technology and applications” in the digital economy major. The research results show that this extended method for the teaching reform plan evaluation is highly effective for scientific decision-making to foster the high-quality development of education, especially in a fuzzy and uncertain environment.

6. Conclusions

Recently, the theory and methods of PULTSs have attracted much attention. PULTSs not only capture decision-makers’ fuzzy linguistic preferences or evaluation information but also convey the probabilistic nature of linguistic terms. By incorporating probability distributions, PULTSs represent varying degrees of confidence in decision-makers’ assessments, which can enable a more precise and nuanced evaluation of multidimensional criteria. The teaching reform plan evaluation is an extremely complex process due to qualitative data, vague information, unforeseen circumstances, and various impact factors, which bring great difficulties in effectively responding to teaching reform plans, especially in the context of the construction of new liberal arts disciplines.

This study proposes an extended VIKOR method with PULTSs, expressing DMs’ fuzzy language preference information in terms of probability to evaluate teaching reform plans for the core course “big data technology and applications” in the digital economy major. The extended method can reflect the fuzziness and uncertainty of complex decision processes more effectively and accurately. A case study of teaching reform plan evaluation is presented to illustrate the effectiveness. Most importantly, the parameter analysis further verifies the effectiveness of the extended VIKOR method. The research results indicate the extended method is a very effective approach to improve decision-making level, especially in a fuzzy and uncertain environment. In addition, this paper establishes a scientifically grounded technology that can ensure precision, effectiveness, and adaptability in evaluating teaching reform plans for the core course “big data technology and applications” in the digital economy major. Moreover, the proposed approach can effectively tackle uncertainty, fuzziness, and the inherent complexity of decision-making processes to address the multifaceted challenges of educational reform in order to foster the high-quality development of education.

The future research directions include four aspects: (1) research on the expansion of PULTS with other methods, such as MCDM, deep learning, and artificial intelligence algorithms; (2) developing an effective implementation plan for teaching reform and formulating educational strategies. (3) decision-making for big data that involves expressing DMs’ fuzzy language preference information, such as t-spherical fuzzy sets, picture fuzzy sets, and q-rung orthopair fuzzy sets; (4) and simulations for result analysis.

Funding

This research was supported by the Fund for Industry–University Cooperative Education Program of the Ministry of Education (220806434314553).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no financial conflicts of interest related to this paper.

References

- Du, S.C.; Tan, H.Z. Exploration of the construction of ideological and political education connotations and the improvement path of sociology experimental courses in the context of the new humanities. Int. J. New Dev. Educ. 2024, 6, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, X.D.; Hu, L. The Innovation of Big Data Technology in the Ideological and Political Education of College Students in Resident Universities under the Background of Local Strategy. Int. Educ. Forum. 2024, 2, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarouk, M.Y.; Peres, P.; Khaldi, M. The Impact of Flipped Project-Based Learning on Self-Regulation in Higher Education. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2020, 15, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.F.; Hwang, G.J.; Chen, M.R.A. Effects of a concept mapping-guided virtual laboratory learning approach on students’ science process skills and behavioral patterns. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2024, 72, 1623–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.F. Teaching Mode Reform and Practice Exploration of Big Data Processing and Analysis under the Background of Industry and Education Integration. Int. J. New Dev. Educ. 2022, 4, 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.S. Probabilistic Linguistic TODIM Method with Probabilistic Linguistic Entropy Weight and Hamming Distance for Teaching Reform Plan Evaluation. Mathematics. 2024, 12, 3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.S.; Xu, Z.S.; Kou, G.; Shi, Y. Decision-making Support for the Evaluation of Clustering Algorithms Based on MCDM. Complexity 2020, 2020, 9602526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.M.; Zhang, F.L.; Li, J.Z.; Guo, T.; Aziz, A.; Jin, A.J.; Xia, F. Educational Big Data: Predictions, Applications and Challenges. Big Data Res. 2021, 26, 100270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltz, J.; Heckman, R. Big Data Science Education: A Case Study of a Project-Focused Introductory Course. Themes Sci. Technol. Educ. 2015, 8, 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.S. Japanese Online and Offline Hybrid Teaching-Learning Analysis Model Built on Big Data Technology. In Proceedings of the 2022 3rd International Conference on Modern Education and Information Management, Chengdu, China, 16–18 September 2022; pp. 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Chang, J.; Lian, F.; Jiang, L.; Liu, J.; Yasrab, R. Construction and Empirical Research of the Big Data-Based Precision Teaching Paradigm. Int. J. Inf. Commun. Technol. Educ. 2022, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CAI, W.Q. Innovation and path of teacher literacy in basic education in the era of artificial intelligence. Reg. Educ. Res. Rev. 2023, 5, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.M.; Shi, Y.; Dong, P.W. Public blockchain evaluation using entropy and TOPSIS. Expert Syst. Appl. 2019, 117, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Boudouh, T.; Grunder, O. A hybrid genetic algorithm for a home health care routing problem with time window and fuzzy demand. Expert Syst. Appl. 2017, 72, 160–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. Fuzzy Sets. Inf. Control. 1965, 8, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanassov, K.T. Intuitionistic fuzzy sets. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1986, 20, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Xu, Z.S.; Liao, H.C. Correlation coefficients of hesitant multiplicative sets and their applications in decision making and clustering analysis. Appl. Soft Comput. 2017, 61, 935–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F. Aggregation Similarity Measure Based on Hesitant Fuzzy Closeness Degree and Its Application to Clustering Analysis. J. Syst. Sci. Inf. 2019, 7, 70–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, T.; Ullah, K.; Khan, Q.; Jan, N. An approach toward decision-making and medical diagnosis problems using the concept of spherical fuzzy sets. Neural Comput. Appl. 2019, 31, 7041–7053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.Y.; Xu, Z.S.; Zhang, Y.X.; Wang, X.X. Dynamic hesitant fuzzy Bayesian network and its application in the optimal investment port decision making problem of “twenty-first century maritime silk road”. Appl. Intell. 2020, 50, 1846–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, T.; Warraich, M.S.; Ali, Z.; Pamucar, D. Generalized MULTIMOORA method and Dombi prioritized weighted aggregation operators based on T-spherical fuzzy sets and their applications. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2021, 36, 4659–4692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.X.; Xu, Z.S.; Wang, H.; Liao, H.C. Consistency-based risk assessment with probabilistic linguistic preference relation. Appl. Soft Comput. 2016, 49, 817–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.L. A Novel Probabilistic Linguistic Approach for Large-Scale Group Decision Making with Incomplete Weight Information. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 2018, 20, 2245–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Q.; Wang, H.; Xu, Z.S. Probabilistic linguistic term sets in multi-attribute group decision making. Inf. Sci. 2016, 369, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, X.J.; Xu, Z.S. Novel basic operational laws for linguistic terms, hesitant fuzzy linguistic term sets and probabilistic linguistic term sets. Inf. Sci. 2016, 372, 407–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.S.; Chin, K.S.; Li, Y.L.; Yang, Y. Proportional hesitant fuzzy linguistic term set for multiple criteria group decision making. Inf. Sci. 2016, 357, 61–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobina, A.; Liang, D.C.; He, X. Probabilistic linguistic power aggregation operators for multicriteria group decision making. Symmetry 2017, 9, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.D.; You, X.L. Probabilistic linguistic TODIM approach for multiple attribute decision-making. Granul. Comput. 2017, 2, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhadinia, B.; Xu, Z.S. Ordered weighted hesitant fuzzy information fusion-based approach to multiple attribute decision making with probabilistic linguistic term sets. Fundam. Informaticae 2018, 159, 361–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Gu, J.; Xu, Z.S. Venture capital group decision-making with interaction under probabilistic linguistic environment. Knowl. Based Syst. 2018, 140, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.W.; Chen, Z.Y.; Liao, H.C.; Xu, Z.S. ELECTRE II method to deal with probabilistic linguistic term sets and its application to edge computing. Nonlinear Dyn. 2019, 96, 2125–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.Q.; Liu, Q.; Wei, C.P. Probabilistic linguistic QUALIFLEX approach with possibility degree comparison. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2019, 36, 710–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.S.; Xu, Z.S. Hybrid TODIM Method with Crisp Number and Probability Linguistic Term Set for Urban Epidemic Situation Evaluation. Complexity 2020, 4, 4857392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.C.; Mi, X.M.; Xu, Z.S. A survey of decision-making methods with probabilistic linguistic information: Bibliometrics, preliminaries, methodologies, applications and future directions. Fuzzy Optim. Decis. Mak. 2020, 19, 81–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Senapati, T.; Yager, R.R. Hybridizations of generalized Dombi operators and Bonferroni mean operators under dual probabilistic linguistic environment for group decision-making. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2021, 36, 6645–6679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.N.; Xu, Z.S. A coordination game model for risk allocation of a PPP project with the weakened hedged probabilistic linguistic term information. Econ. Res.-Ekonomska Istraživanja 2023, 36, 593–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.H.; Song, Y.M.; Xu, Z.W. Large-Scale Group Decision-Making Method with Public Participation and Its Application in Urban Management. Mathematics 2024, 12, 2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.H. Fuzzy VIKOR method: A case study of the hospital service evaluation in Taiwan. Inf. Sci. 2014, 271, 196–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifullah, S.A.; Almagrabi, A.O. An Integrated Group Decision-Making Framework for the Evaluation of Artificial Intelligence Cloud Platforms Based on Fractional Fuzzy Sets. Mathematics 2023, 11, 4428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Qin, X. An Extended VIKOR Method for Decision Making Problem with Interval-Valued Linguistic Intuitionistic Fuzzy Numbers Based on Entropy. Informatica 2017, 28, 665–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, G.; Lin, Z.F.; Lei, Z.; Chen, J.L. Failure modes and effects analysis for CO2 transmission pipelines using a hesitant fuzzy VIKOR method. Soft Comput. 2019, 23, 10321–10338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.P.; Chen, Q.S.; Li, X.F.; Gou, X.J. An Improved PL-VIKOR Model for Risk Evaluation of Technological Innovation Projects with Probabilistic Linguistic Term Sets. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 2020, 23, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delcea, C.; Nica, I.; Georgescu, I.; Chiriță, N.; Ciurea, C. Integrating Fuzzy MCDM Methods and ARDL Approach for Circular Economy Strategy Analysis in Romania. Mathematics 2024, 12, 2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.S. Goal programming models for multiple attribute decision making under linguistic setting. J. Manag. Sci. China 2006, 9, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, F.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Verdegay, J.L. A sequential selection process in group decision making with a linguistic assessment approach. Inf. Sci. 1995, 85, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.W.; Xu, Z.S.; Zhai, Y.L.; Yao, Z.Q. Multi-attribute group decision-making under probabilistic uncertain linguistic environment. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2018, 69, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Wang, H.; Xu, Z.S. Uncertain probabilistic linguistic term sets in group decision making. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 2019, 21, 1241–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.Y.; Ren, Z.L.; Xu, Z.S.; Wang, H. The consensus of probabilistic uncertain linguistic preference relations and the application on the virtual reality industry. Knowl. Based Syst. 2018, 162, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.S. Uncertain linguistic aggregation operators based approach to multiple attribute group decision making under uncertain linguistic environment. Inf. Sci. 2004, 168, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.B.; Xu, J.P. Possibility distribution-based approach for MAGDM with hesitant fuzzy linguistic information. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2016, 46, 694–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opricovic, S.; Tzeng, G.H. Compromise solution by MCDM methods: A comparative analysis of VIKOR and TOPSIS. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2014, 156, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.Y.; Yuan, F.F.; Wan, S.P. Extended VIKOR method for multiple criteria decision-making with linguistic hesitant fuzzy information. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2017, 112, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opricovic, S.; Tzeng, G.H. Extended VIKOR method in comparison with outranking methods. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2007, 178, 514–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.L.; Xing, X.M. Probabilistic Linguistic VIKOR Method to Evaluate Green Supply Chain Initiatives. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Barrios, M.; Hoz, C.M.L.; López-Meza, P.; Petrillo, A.; Felice, F.D. A case of food supply chain management with AHP, DEMATEL, and TOPSIS. J. Multi-Criteria Decis. Anal. 2020, 27, 104–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. The Analytic Hierarchy Process: Planning, Priority Setting, Resource Allocation; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Shan, N.; Chen, X. Effective link prediction in multiplex networks: A TOPSIS method. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 177, 114973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).