Abstract

The Feynman–Kac formula establishes a link between parabolic partial differential equations and stochastic processes in the context of the Schrödinger equation in quantum mechanics. Specifically, the formula provides a solution to the partial differential equation, expressed as an expectation value for Brownian motion. This paper demonstrates that the Feynman–Kac formula does not produce a unique solution but instead carries infinitely many solutions to the corresponding partial differential equation.

Keywords:

Feynman–Kac formula; Schrödinger equation; partial differential equation; Brownian motion; uniqueness MSC:

35G10; 35D99; 35Q40; 35Q79

1. Introduction

In the 1940s, Feynman [1] disclosed that the Schrödinger equation, which governs the time evolution of quantum states in quantum mechanics, could be solved by averaging over sample paths, an observation which led him to a far-reaching reformulation of the quantum theory in terms of path integrals [2,3]. Based on this idea, Kac recognized that a similar representation could be given for solutions of the heat transfer equation [4,5]. Accordingly, this representation is now referred to as the Feynman–Kac formula, which verifies and extends Feynman’s path integrals [6]. The Feynman–Kac formula has numerous applications in various fields including mathematics, statistics, physics, chemistry, and finance [7,8], providing an intriguing connection between solutions of elliptic and parabolic differential equations and stochastic processes. Specifically, it provides a method for solving a variety of partial differential equations (PDEs) through random path simulations of a stochastic process. For instance, in quantitative finance, the relationship between geometric Brownian motion and the Black–Scholes PDE is a special case of the Feynman–Kac theorem [9]. Conversely, some stochastic differential equations describing random processes can be examined by deterministic methods [10].

To present the Feynman–Kac formula, we consider the continuous functions , , and , where is fixed. Suppose that v is a continuous, real-valued function of class on and satisfies

with the terminal condition

Then, the function v is said to be a solution of the Cauchy problem for the backward heat Equation (1) with potential k and Lagrangian g, subject to the terminal condition in Equation (2). Note also that Equation (1) with corresponds precisely to the Schrödinger equation (in the imaginary time) for a particle in potential k. Suppose that

where K is a positive constant and . The Feynman–Kac formula consists of the existence part and the uniqueness part as follows: The former states that v admits the stochastic representation

for any and , where is a d-dimensional Brownian motion and is the expectation operator with . Then, the latter asserts that such a solution is unique, as remarked in Refs. [11] (p. 268) and [12] (p. 120). Readers may also refer to Refs. [6] (Chapter 3), [13] (Section 11.4), and [14] (Section 8.2), for further details on the Feynman–Kac formula.

In this paper, we present a counterexample that violates the uniqueness of the Feynman–Kac formula. Specifically, it is disclosed that the Feynman–Kac formula carries infinitely many solutions rather than a unique solution. The possibility of nonuniqueness alerts us that the solution method based on the Feynman–Kac formula may lead to extraneous and irrelevant results. These implications are discussed in relation to the initial conditions.

2. A Boundary-Value Problem and Its Feynman–Kac Solution

We consider a simple example for with

and let with . General cases with nonvanishing k and g are considered later in Section 3. Then, Equations (1) and (2) become, respectively,

It is well known (see, e.g., [15]) that is the fundamental solution of the PDE (6), where is the probability density function of the standard Gaussian random variable.

We now define the function

for , which, according to the Feynman–Kac formula, satisfies the heat transfer PDE (6) and the initial condition in Equation (7). Equation (8) is divided into two parts:

with

where is the indicator function of a subset A and is the cumulative distribution function of the standard Gaussian random variable. It is then easy to show that and satisfy the heat transfer PDE:

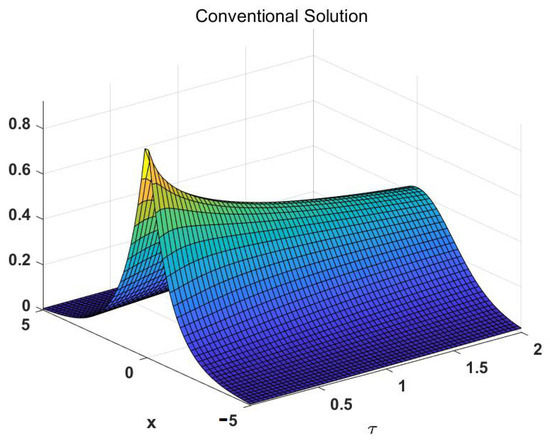

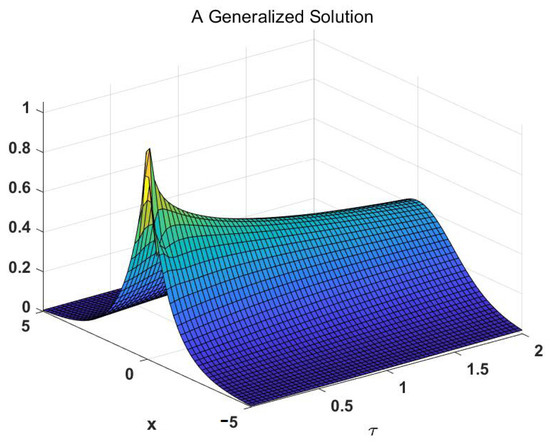

For comparison, we plot the conventional (fundamental) solution in Figure 1 and the generalized solution given by Equation (9) in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Conventional solution , called the fundamental solution. The darker the color, the lower the value of the solution.

Figure 2.

Generalized solution , given by Equation (9). The darker the color, the lower the value of the solution.

Note that Equation (9) plotted in Figure 2 generalizes the fundamental solution in Figure 1 to a heavy-tailed skew distribution [16].

Here, we remark that is not defined for . Accordingly, as in Theorem 55.4 of Körner [17] (p. 277), the initial condition in Equation (7) should be replaced by

This means that the solution should be assumed right-continuous at ; otherwise, the heat transfer PDE may not be connected with the initial condition.

3. Kernel Solutions

As discussed in Körner [17] (pp. 338–346), the uniqueness of a heat transfer boundary problem is not as trivial a question as sometimes claimed. The simple uniqueness theorem presented there goes as follows: Let be twice differentiable satisfying the heat transfer PDE (6). If as uniformly for x in any chosen interval and if as uniformly for t in any chosen interval , then for all However, even the fundamental solution does not satisfy the former uniformity condition, making this uniqueness theorem not so practical. Recently, on the other hand, general solutions of the heat transfer boundary problem were reported [16,18]. Using those general solutions of the heat transfer boundary problem, we now present additional representations of the Feynman–Kac formula.

For any , we consider the probabilists’ Hermite polynomial of order m:

the first five of which are given by , , , , and . For each , we define

which can be written as

with

Here, we note that

and make use of the transform to write

where the identity

has been used for obtaining the third equality. We further note that

which gives

and

Putting Equation (23) into Equation (20) leads to

with

Applying a mathematical induction to Equation (25), one finds that can be expressed as a linear combination of the expectations in Equation (17).

Letting , we obtain

which in turn yields

and

These two Equations (28) and (29) imply

where the last equality holds by the recurrence relation

It is thus concluded that satisfies the heat transfer PDE:

for each . Since and for satisfy the heat transfer PDE (6), Equation (25) indicates that the expectation also satisfies the PDE.

Likewise, we can show

with

which, again via a mathematical induction applied to Equation (33), can be shown to obtain the form of a linear combination of the expectations in Equation (18). It is then straightforward to show, in the same manner as before, that satisfies the heat transfer PDE:

for each . Since as well as satisfy the heat transfer PDE (6), Equation (33) indicates that also satisfies the PDE.

Now Equations (16), (25), and (33) imply

which satisfies the heat transfer PDE in Equation (6). For any and , we define

with

Equations (32) and (35) show that satisfies the heat transfer PDE:

Henceforth, we find the coefficients subject to the initial condition

Applying L’Hospital’s rule to Equations (26) and (34), we obtain

for . Therefore, we have

for . Meanwhile, the symmetries of and imply

for , which, together with Equation (38), lead to

In consequence, we obtain

which result in

Let us consider the case where the coefficients and of vanish for each k. Labeling such a set of coefficients with as , we write

with

where is the largest integer less than or equal to x. It is then obvious from Equations (32) and (35) that satisfies the heat transfer PDE (6). Moreover, Equations (42) and (49) imply that vanishes as approaches zero from above:

To summarize, we have the “theorem” that the Feynman–Kac formula does not support the uniqueness property: is a kernel solution to the boundary-value problem consisting of the heat transfer PDE (6) and the initial condition in Equation (52), and accordingly, is a generalized solution to the boundary-value problem consisting of the heat transfer PDE (6) and the initial condition in Equation (52). Note that , expressed as a linear combination of the expectations in Equation (17) and in Equation (18), satisfies the heat transfer PDE (6) and the initial condition in Equation (7) for any and . It is thus concluded that the Feynman–Kac formula does not support the uniqueness property, which proves the “theorem”.

Finally, we consider the extension of the analysis, albeit one counterexample should suffice for falsification [19], to the general case of Equation (1) with nonvanishing k and g, again for . (Generalization to the case of higher dimensions, , is straightforward.) First, suppose that v is a solution of the equation for :

with vanishing boundary conditions. We know that there exist infinitely many solutions u of the equation with :

with appropriate boundary conditions. Adding the two Equations (53) and (54), we obtain that satisfies Equation (53) with the same boundary conditions as those in Equation (54). Since there are infinitely many u, we thus conclude that Equation (53) indeed carries infinitely many solutions. We next consider the case of constant k and :

Multiplying both sides by , we obtain Equation (54) for . This again implies that Equation (55) carries infinitely many solutions of the form . (This can also be generalized to the case of time-dependent , where takes the place of in the procedure. Namely, the solutions of Equation (55) assume the form . More generally, in the presence of both g and k, putting yields Equation (53) with g replaced by . As a result, the solution takes the form , where v is a solution of Equation (53) (with g replaced by ) and u represents the infinitely many solutions of Equation (54). The most general case of k depending on x is beyond the scope of this paper and left for future study.

Now, let us comment on how to obtain the “unique” solution among the generalized solutions. When generating random numbers from a Brownian motion in Equation (4), we need initial conditions in the time interval (with ) in addition to those at the time . These initial conditions generate the random numbers of one particular generalized solution. This is related to the assumption that the solution is differentiable at . Note also that in physics, we usually deal with the case where the initial conditions are given in the steady state [20] (p. 11). This amounts to assuming the initial conditions in the time interval , not just at the time . Therefore, the PDE is uniquely determined by the conditions specified in the time interval .

4. Conclusions

We have shown that the Feynman–Kac formula does not yield a unique solution but carries infinitely many solutions, as demonstrated by the counterexample presented. This indicates that the Feynman–Kac formula, albeit a useful and elegant tool, should be used with caution. In quantum mechanics, as addressed in Section 1, this formula gives the path integral representation of the solution of the Schrödinger equation. The nonuniqueness then suggests an interesting possibility of additional solutions other than the conventional ones. Their implications are currently under investigation. Furthermore, in quantitative finance, the Feynman–Kac formula is used widely to compute efficiently solutions of the Black–Scholes PDE for European option prices [9]. There the nonuniqueness of the Feynman–Kac formula brings on infinitely many solutions to the Black–Scholes boundary-value problem [21]. This indicates that the Black-Scholes formula violates the fundamental law of one price in economics.

In general, the Feynman–Kac formula has been utilized to solve certain PDEs via random path simulations of stochastic processes and to compute some expectations for random processes by deterministic methods. However, one should be cautious since its nonuniqueness implies that such methods may produce unreliable results. It would be of interest and importance to clarify mathematical criteria, if any, for the validity of such an analysis with respect to the existence and uniqueness in PDEs. It is suggested that the nonuniqueness is related to the nature of the initial condition. Such an assumption of stationarity or differentiability amounts to the initial condition assumed in a time interval, which may determine the PDE uniquely. The investigation of this relationship is left to future studies, where the main point will be presented more succinctly, and the detailed argument will be more focused.

Author Contributions

B.S.C. conceived the study, investigated the system, and devised the model. M.Y.C. analyzed and validated the model. Both contributed to writing the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea through the Basic Science Research Program (grant no. 2022R1A2C1012532).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created in this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Feynman, R.P. Space-time approach to nonrelativistic quantum mechanics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1949, 20, 367–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.L.; Rao, K.M. Feynman-Kac functional and the Schrödinger equation. In Seminar on Stochastic Processes: Progress in Probability and Statistics; Çinlar, E., Chung, K.L., Getoor, R.K., Eds.; Birkhäuser: Boston, MA, USA, 1981; Volume 1, pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Feynman, R.P. QED: The Strange Theory of Light and Matter; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Kac, M. On distributions of certain Wiener functionals. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 1949, 65, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kac, M. On some connections between probability theory and differential and integral equations. In Proceedings of the Second Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability, Berkeley, CA, USA, 31 July–12 August 1950; Neyman, J., Ed.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1951; pp. 189–215. [Google Scholar]

- Glimm, J.; Jaffe, A. Quantum Physics: A Functional Integral Point of View, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Borodin, A.N. Versions of the Feynman-Kac formula. J. Math. Sci. 2000, 99, 1044–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caffarel, M.; Claverie, P. Development of a pure diffusion quantum Monte Carlo method using a full generalized Feynman–Kac formula I. Formalism. J. Chem. Phys. 1988, 88, 1088–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreve, S.E. Stochastic Calculus for Finance II: Continuous-Time Models; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Flesher, F. Stochastic Proesses and the Feynman-Kac Theorem. Available online: https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/forrestgflesher/files/final_paper_final.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Karatzas, I.; Shreve, S.E. Brownian Motion and Stochastic Calculus, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Schilling, R.L.; Partzsch, L. Brownian Motion: An Introduction to Stochastic Processes, 2nd ed.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, H.-H. Introduction to Stochastic Integration; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Oksendal, B. Stochastic Differential Equations: An Introduction with Applications, 6th ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, L.C. Partial Differential Equations, 2nd ed.; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, B.S.; Kang, H.; Choi, M.Y. Emergence of heavy-tailed skew distributions from the heat equation. Physica A 2017, 470, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körner, T. Fourier Analysis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, B.S.; Kim, C.; Kang, H.; Choi, M.Y. General solutions of the heat equation. Physica A 2020, 539, 122914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popper, K. The Logic of Scientific Discovery; Hutchinson: London, UK, 1959; Reprinted by Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Farlow, S.J. Partial Differential Equations for Scientists and Engineers; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, B.S.; Choi, M.Y. General solution of the Black-Scholes boundary-value problem. Physica A 2018, 509, 546–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).