Abstract

In several publications, the dynamical system of HIV and HTLV mono-infections taking into account diffusion, as well as latently infected cells in cellular transmission has been mathematically analyzed. However, no work has been conducted on HTLV/HIV co-infection dynamics taking both factors into consideration. In this paper, a partial differential equations (PDEs) model of HTLV/HIV dual infection was developed and analyzed, considering the cells’ and viruses’ spatial mobility. CDT cells are the primary target of both HTLV and HIV. For HIV, there are three routes of transmission: free-to-cell (FTC), latent infected-to-cell (ITC), and active ITC. In contrast, HTLV transmits horizontally through ITC contact and vertically through the mitosis of active HTLV-infected cells. In the beginning, the well-posedness of the model was investigated by proving the existence of global solutions and the boundedness. Eight threshold parameters that determine the existence and stability of the eight equilibria of the model were obtained. Lyapunov functions together with the Lyapunov–LaSalle asymptotic stability theorem were used to investigate the global stability of all equilibria. Finally, the theoretical results were verified utilizing numerical simulations.

Keywords:

HTLV/HIV co-infection; virus infection; cell-to-cell infection; mitotic transmission; CTL immune response; diffusion; global stability; latency MSC:

35B35; 37N25; 92B05

1. Introduction

Mathematical models and their analysis are efficient and important means of comprehending the dynamics of within-host viral infections. This contributes to a deeper understanding of viral disease structures caused by many viruses such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and human T-lymphotropic virus (HTLV), as well as other viruses such as dengue virus (DENV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), and, most recently, coronavirus (COVID-19). In fact, this may lead to an improvement in therapeutic interferences and control infectious diseases. HTLV and HIV are transmitted in similar ways from one infected person to another. Both viruses share in common the ability to infect specific immune cells, which are the CDT cells. HTLV does not cause acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) as in the case of HIV; however, it causes fatal diseases such as HTLV-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP) and adult T-cell leukemia (ATL).

In a groundbreaking study, Nowak and Bangham developed a fundamental model of HIV dynamics [1]. Since then, many works have been published that involved expanded models of this model. Lai and Zou [2] have proposed a mathematical model that describes the dynamics of HIV-1 infection, where direct cell-to-cell transmission and virus-to-cell transmission are considered, as two forms of viral infection. Mojaver and Kheiri [3] developed a model of HIV infection that takes into account cell-to-cell transmission and antiretroviral therapies (HAART) that can be used to treat and control HIV infection. They reported that HAART uses the inhibitors of reverse transcriptase and protease to prevent HIV infection from becoming a fatal disease (AIDS) [3]. A multi-pathway and multi-delay HIV-1 infection model was studied by Adak and Bairagi [4]. It was found that the system exhibited different switching phenomena even without delays. A mathematical model of HIV dynamics was developed by Guo and Qiu [5] to analyze the effect of cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) immune response on the infection dynamics. In this study, the potent therapy, latently infected cells, and cell-to-cell viral transmission were taken into account. Liu and Zhang [6] investigated the dynamics of a two-times delay differential equation model that investigates the dynamics of HIV infection with latency and considering a nonlinear type of HIV infection rate. Chen et al. [7] presented a complete study on the global dynamics of an HIV viral infection model with a saturated incidence rate of infection, as well as a wild-type and a drug-resistant strain of influenza virus.

In the above-mentioned works, all the mathematical models were based on ordinary or delay differential equations without considering the cells’ and viruses’ spatial mobility. In 2007, Wang and Wang [8] incorporated a spatial dependence into the model presented in [1]. Several considerations have been incorporated into the model presented by [8], and these include time delay, different forms of the incidence rate, and immune responses (see [9,10,11]).

It is important to note that the model introduced by [8] has neglected two crucial aspects:

- Viral latent reservoirs: A major impediment to eliminating HIV infection by antiretroviral therapy is the presence of latent HIV-infected cells. Cells that are latently infected carry the virions, but do not generate them until they are activated. There are many studies that have dealt with the development of HIV infection models with active and latent infected cells without taking spatial dependence into account, e.g., [12,13,14,15].

- Cellular transmission: Wang and Wang [8] considered only one mode of transmission of the infection occurring when the HIV particles infect the healthy CDT cells (FTC), but several studies have indicated that infected-to-cell (ITC) is another method of transmission, carried out through virological synapses between HIV-infected and healthy CDT cells [16]. Wang et al. [17] extended the work of [8] by including ITC transmission. Following that, Sun and Wang [18] incorporated time delay into the model presented in [17] and considered the incidence rate in a general form.

Based on the work presented in [8], Xu et al. [19] included the ITC infection in their model. In this study, ITC infection arises from the contact between active infected cells and healthy cells. Recently, according to [20], latent and active HIV-infected cells are capable of infecting healthy CDT cells through the HIV ITC mechanism. Elaiw and AlShamrani [21] assumed nonlinear general forms of ITC and FTC transmissions in the HIV infection model. It was assumed that virus particles can move according to Fickian diffusion, whereas cells cannot in all of the above-mentioned models.

In several recent studies, the assumption was made that viruses, healthy cells, infected cells, and immune cells were capable of diffusing [22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Gao and Wang [22] investigated a reaction–diffusion HIV-1 dynamics model with time delay and cell-to-cell dissemination. It was assumed in [23] that viruses, uninfected cells, infected cells, and humoral immune cells can diffuse. In [24], the authors examined the global asymptotic stability of a reaction–diffusion virus infection model with homogeneous environments, nonlinear incidence in heterogeneous environments, and humoral immunity. AlAgha and Elaiw [25] presented a study of the global stability of an HIV-1 model with humoral immune response and heterogeneous diffusion. In [26], Elaiw and AlAgha analyzed the dynamics of a system with discrete time delays and three types of infected cells: latently, short-lived productively, and long-lived productively infected cells. The models in [25,26] contain some parameters that measure the efficiency of highly active antiretroviral therapies (HAARTs). Wang et al. [27] proposed a diffusive viral infection model incorporating cell-to-cell infection mode, nonlinear incidences, incubation period, and spatial heterogeneity. Ren et al. [28] discussed the impact of cell-to-cell transmission and the mobility of viruses and cells on HIV-1 dynamics. The following model that considers the mobility of HIV particles and cells was presented by Wang et al. [27]:

In this model, at position and time t, the densities of healthy CDT cells, latent infected cells, active infected cells, and free virus particles are represented by , and respectively. , , , and are the diffusion coefficients of the corresponding compartments, and is the Laplacian operator. Cells that are healthy are created at a rate Healthy cells are infected by the viral particles through FTC transmission at a rate . The terms and represent the ITC incidence rates that occur when healthy CDT cells come into contact with latent or active infected cells, respectively. Cells that have been latently infected become active at a rate Viruses are produced by active infected cells at a rate of The rates of death for healthy cells, latent infected cells, active infected cells, and viral particles are , , and , respectively.

Additionally, in several studies, the dynamics of HTLV mono-infections have been modeled and analyzed [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. Vargas-De-Leon [29] provided a complete classification of the global dynamics for an HTLV mono-infection model taking the latently infected cells into consideration. Lim and Maini [30] formulated a model for HTLV-I dynamics under the consideration of CTL immunity and mitotic division of active HTLV-infected cells. Pan et al. [31] proposed a model to describe the dynamics of HTLV infection with CTL immunity and time delays. Wang et al. [32] developed an HTLV-I infection model with nonlinear lytic and nonlytic CTL immunity, nonlinear incidence rate, distributed delay, and immune impairment. Wang et al. [33] studied a model of HTLV-I infection with two time delays: an intracellular delay and a CTL immune response delay. Refs. [34,35] discussed HTLV infection with the presence of CTL immunity, as well as the mitotic division of the active infected cells. Except for Wang and Ma [36], all of these HTLV dynamics models neglected the diffusion of viruses and cells. In [36], CTL immunity and the mitotic division of active infected cells were included in a diffusive HTLV infection model.

In the past decade, there has been considerable reporting on HTLV and HIV co-infections. Infection by both viruses concurrently affects pathogenic development and associated chronic disease outcomes [37]. There has been documentation of HTLV/HIV co-infection in certain areas where both retroviruses appear endemic [38] and in individuals who are of a certain ethnicity as well. In highly endemic regions such as South America and Sub-Saharan Africa, co-infections with HIV and HTLV are common. Further, the rate of concurrent HTLV and HIV infections is high in areas where people swap needles and participate in unprotected sexual relationships. According to statistics from some parts of Brazil, 16% of HIV patients in some areas have co-infection [39].

According to a recent study, the results showed that HIV-infected individuals are more likely to be co-infected with HTLV 100- to 500-times more often than people who are not infected [40]. Additionally, several studies have shown that HTLV-infected individuals have a higher likelihood of concomitant HIV infection, and vice versa, as compared to the general population who is infection-free [38]. HTLV and HIV affect primarily CDT cells and cause immune dysfunction, but their etiologies and clinical outcomes are also in conflict [41]. According to many researchers, HIV-infected patients who possibly have concurrent HTLV infection are at risk of developing AIDS. While the progression of HTLV in co-infected individuals is modified by HIV, resulting in diseases such as HAM∖TSP and ATL [38,40].

Although many mathematical models and analyses have been developed for HTLV and HIV mono-infections, very few works have considered the dynamics of co-infection with HTLV and HIV. There are a few exceptions, namely the very recent papers in [42,43,44,45].

As a consequence of the above, co-infection of HTLV/HIV; involving both latent and active infected cells sharing ITC infection, as well as the diffusion of viruses and cells; has never been mathematically studied. Therefore, in light of the works of [44,45], this study aims to develop and analyze an HTLV/HIV co-infection model taking into account the following considerations:

- (C1)

- The hosts of both HIV and HTLV are healthy CDT cells;

- (C2)

- The presence of latently infected HIV and HTLV cells;

- (C3)

- Both HTLV and HIV have a specific bilinear CTL immune response;

- (C4)

- Several factors can lead to CDT cells becoming infected with HIV, including free HIV particles, latent HIV-infected cells, and active HIV-infected cells;

- (C5)

- HTLV has two routes of transmission: (i) horizontally through the straight ITC contact over the virological synapse and (ii) vertically where the active HTLV-infected cells can transmit HTLV via mitotic division;

- (C6)

- All types of cells and viruses diffuse spatially.

The novelty and advantages of the developed model are generalization and improvement of many mathematical models existing in the literature describing HTLV/HIV co-infection by considering three routes of transmission and other biological factors.

The well-posedness of the model has been verified by proving the non-negativity and the boundedness of the model’s solutions. Our analysis yielded a number of threshold parameters that set the presence of the equilibria and their stability. We formulated Lyapunov functions and used the Lyapunov–LaSalle asymptotic stability theorem (L-LAST) to demonstrate the global stability of all equilibria. To assert our analytical results, we supply numerical simulations of the model. Due to the possibility of an individual having two or more infections at the same time, our model may be useful for studying co-infections such as COVID-19 with influenza and HIV with HCV or HBV. Our proposed model and its mathematical analysis will assist clinicians in estimating when to initiate treatment in patients who have co-infections with more than one virus.

2. Model Formulation

We propose the following partial differential equations model based on the statements (C1)–(C6) mentioned in Section 1:

where and , with boundary conditions:

and initial conditions:

The following is a description of Model (1) with Conditions (2) and (3): At position and time the compartments and represent the density of latent and active HTLV-infected cells. and are the CTLs specific for HIV and for HTLV, respectively. Through ITC contact, healthy CDT cells become infected with HTLV at a rate . The ratio identifies the possibility that HTLV infections will be latent. denotes the rate at which active HTLV-infected cells are passed to become latently infected and escape the immune system [35]. The mortality rates of latent and active HTLV-infected cells are and , respectively. is the rate at which latent HTLV-infected cells are activated. HIV-infected cells and HTLV-infected cells die, respectively, at rates as a result of their specific immunity. CTLs particular to HIV and HTLV expand at distinct rates , , and they decay at rates , respectively. The diffusion coefficients of the compartments P, , are , , and . As illustrated in Section 1, all remaining parameters have the same name and explanation.

The boundary conditions (2) are the homogeneous Neumann boundary conditions, which can provide a natural spreading limit and ensure that viruses and cells are unable to escape through the isolated boundaries [46]. The open domain is connected and bounded with a smooth boundary , and the unit vector is the outward normal vector on . The functions , are non-negative and continuous.

We will assume that [30]. It follows that and then

Let and . Therefore, Model (1) can be written as

3. Properties of Solutions

Proposition 1.

Proof.

Define the norm where the set comprises all uniformly bounded and continuous functions from to . Consider a positive cone that leads to partial order on . As a result, the space is a Banach lattice [47,48].

Let with any initial data , given by

Clearly, is locally Lipschitz on . It is possible to rewrite System (4) with the boundary conditions (2) and initial conditions (3) as the following abstract functional differential equation:

where and In this case,

According to [47,48,49], System (4) with (2)–(3) has a unique non-negative mild solution defined on for any , where the maximum time interval during which exists is . Additionally, is a classical solution.

In order to establish that solutions are bounded, let

Since , then using System (4), we obtain

We have . Hence,

where . Therefore, satisfies the following system:

Assume is a solution of the ordinary differential equation system given below:

Accordingly, this gives . In accordance with the comparison principle (see [50]), we obtain . Thus,

and this implies that and are bounded on . Using the standard theory for semi-linear parabolic systems, we concluded that [51]. As a result, the solution is defined for all , unique, non-negative, and bounded. □

4. Equilibrium Analysis

This section is devoted to the study of computing the model’s threshold parameters and equilibria. Model (4) satisfies the following equations:

The results of the calculations show that there are eight equilibrium points for Model (4):

- Infection-free equilibrium, and . Both HIV and HTLV are not present in this case.

- Persistent HIV mono-infection equilibrium accompanied by an inefficient immune response, with components given byThe parameter defines the basic HIV mono-infection reproductive number for Model (4), which is given asis responsible for determining whether or not a persistent HIV mono-infection is possible. In the meantime, the immune system is unable to respond effectively. In addition, exists if .

- Persistent HTLV mono-infection equilibrium accompanied by an inefficient immune response, , with components given byThe parameter specifies the basic HTLV mono-infection reproductive number for Model (4) and is given asis responsible for determining whether or not a persistent HTLV mono-infection is possible. In the meantime, the immune system is unable to work effectively. Further, exists if .

- Persistent HIV mono-infection equilibrium accompanied only by efficient HIV-specific CTL, , with components given byandrepresents the HIV-specific CTL immunity reproductive number for HIV mono-infection. In the case of HIV mono-infection, indicates whether or not HIV-specific CTL immunity is efficient in the case of HIV mono-infection where the HTLV infection is not present. The component satisfies the quadratic equation:whereSince and , then and the positive real root of Equation (5) is calculated as follows:exists if .

- Persistent HTLV mono-infection equilibrium accompanied only by efficient HTLV-specific CTL, , with components given byThe term is introduced as the HTLV-specific CTL immunity reproductive number for HTLV mono-infection and is defined asIn fact, indicates whether or not HTLV-specific CTL immunity is efficient in the case HTLV mono-infection where the HIV infection is not present. On the other hand, exists if .

- Persistent HTLV/HIV co-infection equilibrium accompanied only by efficient HIV-specific CTL, , with components given byHere, is the HTLV infection reproductive number when the HIV infection exists, andwhereIn fact, determines whether or not HIV-infected individuals can further be dually infected with HTLV.

- Persistent HTLV/HIV co-infection equilibrium accompanied only by efficient HTLV-specific CTL, , with components given byrepresents the HIV infection reproductive number when HTLV infection exists, andThe parameter indicates whether or not an HTLV-infected individual can further be dually infected with HIV.

- Persistent HTLV/HIV co-infection equilibrium accompanied by efficient HIV-specific CTL and HTLV-specific CTL, , with components given byandThe parameters and represent, respectively, the competingHIV-specific CTL and HTLV-specific CTL reproductive numbers in the case of HTLV/HIV co-infection. Here, satisfies the equation:whereSince and , then and the positive real root of Equation (7) is calculated as follows:It is obvious that if and then exists.

5. Global Properties

This section is devoted to the implementation of a Lyapunov method to check the global stability of the equilibria of Model (4). To do so, we constructed Lyapunov functions as described in the works [52,53]. We further considered the following concepts:

- -

- According to the arithmetic–geometric mean inequality:we have

- -

- Consider a function in which

- -

- Denoteand let represent the largest invariant subset of

- -

- Define a function . We have that for all and if and only if .

- -

In order to simplify the notation, we denote by . Based on the above concepts, the following subsections will deal with proving the global stability analysis of each equilibrium point.

5.1. Stability of Equilibrium

Theorem 1.

The equilibrium of Model (4) is globally asymptotically stable (GAS) when and

Proof.

Define a Lyapunov function as

Clearly, for all and at . Calculating along the solutions of Model (4) as follows:

Using , we obtain

Therefore, we calculate as follows:

Hence, for any and when . The solutions of Model (4) are limited to . It can be seen that the elements of the set satisfy . Then, , and the fifth equation of Model (4) becomes

Thus, . The third and sixth equations of Model (4) yield

We can define a Lyapunov function as follows

Then, can be computed along the solutions of Model (14) as follows

Clearly, when . Let

Thus

As a result of applying L-LAST, we concluded that is GAS [54,55,56]. □

5.2. Stability of Equilibrium

To prove the global stability of , we need the following lemma:

Lemma 1.

If , then .

Theorem 2.

The equilibrium of Model (4) is GAS when , and

Proof.

Construct a Lyapunov function as follows:

Calculating as

Applying the equilibrium conditions for :

we have

Further, we obtain

Therefore, Equation (15) becomes

Calculating and using Equality (12) to obtain

Using Lemma 1, we obtain that whenever . Moreover, since , then utilizing Inequalities (9)–(10), we obtain for any . Moreover, at The trajectories of Model (4) tend to , which consists of the element where Hence, , and the fifth equation of Model (4) reduces to

and gives . Hence, and is GAS by using L-LAST. □

5.3. Stability of Equilibrium

Theorem 3.

The equilibrium of Model (4) is GAS when , , and

Proof.

Assume is defined as follows:

We calculate as

Using the equilibrium conditions for :

We obtain

Thus, if and , then from Inequality (11), we obtain for any . In addition, at Similar to the proof of Theorem 1, one can demonstrate that , and L-LAST implies that is GAS. □

5.4. Stability of Equilibrium

Theorem 4.

The equilibrium of Model (4) is GAS when and

Proof.

Define a function as

We calculate as

Equation (19) can be simplified as

Applying the equilibrium conditions for :

we have

Moreover, we obtain

Computing the time derivative of and applying Equality (12), Equation (20) will take the following form:

Obviously, if , then does not exist since and . Accordingly, in this case, we have

The next step is to find the value with such that and . Let us consider

5.5. Stability of Equilibrium

Theorem 5.

The equilibrium of Model (4) is GAS when and

Proof.

Define as follows:

Calculating as given below:

Using the equilibrium conditions for :

Then, we find

Hence, if , then from Inequality (11), we obtain , for any , . In addition, at The solutions of Model (4) are limited to . Therefore, in the same way that Theorem 1 was proven, one can demonstrate that . Applying L-LAST, we obtain that is GAS. □

5.6. Stability of Equilibrium

Theorem 6.

The equilibrium of Model (4) is GAS when , , and

Proof.

Define as follows:

Calculating as stated below:

Equation (21) can be simplified as

Using the equilibrium conditions for :

We obtain

Further, we have

Then, Equation (22) will be simplified as follows:

Now, along the solution trajectories of Model (4), we calculate and utilize Equality (12) to obtain the following result:

Hence, if , then does not exists since . Since the existence of the equilibria does not depend on the diffusion terms, therefore, in the absence of diffusion, we can say for all . Thus, . Hence, from Inequalities (9)–(11), we obtain for all . We also have at . The trajectories of Model (4) are limited to , and hence, . Applying L-LAST, we obtain is GAS. □

5.7. Stability of Equilibrium

To prove the global stability of , we need the following lemma:

Lemma 2.

If , then .

Theorem 7.

The equilibrium of Model (4) is GAS when , , and

Proof.

Define as follows:

Calculating as follows:

Simplifying Equation (23), we derive

Using the equilibrium conditions for :

It follows that

As a result, we obtain

Then, Equation (24) will be simplified to

5.8. Stability of Equilibrium

Theorem 8.

The equilibrium of Model (4) is GAS when and

Proof.

Define as follows:

Calculating as follows:

Simplifying Equation (25), we derive

The equilibrium conditions for give

This implies that

In addition, we obtain

Calculating and using Equality (12), we find

Let with the norm . By a simple computation, we have as . Hence, the Lyapunov functions , i = 0, 1, …, 7 considered in the proofs of Theorems 1–8 are unbounded. In addition, Table 1 summarizes the results obtained in these theorems.

Table 1.

Global stability conditions for the equilibria of Model (4).

6. Numerical Simulations

This part illustrates the global stability of equilibria using numerical simulations based on the parameters listed in Table 2; some values of these parameters for HIV were obtained from [57]. To numerically solve the system of PDEs, we used the solver PDEPE in MATLAB (see the code given in the link given in [58]: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/math10224390/s1 (accessed on 15 January 2023)). Additionally, a comparison study between mono-infection and co-infection dynamics will be demonstrated. We selected a step size of for time and a domain as with a step size of . In addition, we considered Model (1) under the initial conditions:

and the homogeneous Neumann boundary conditions:

Table 2.

List of parameters of Model (1).

6.1. Stability of the Equilibria

Under the above initial and boundary conditions, we chose various values of the parameters , , , , and , which yielded the following cases:

- (1)

- (2)

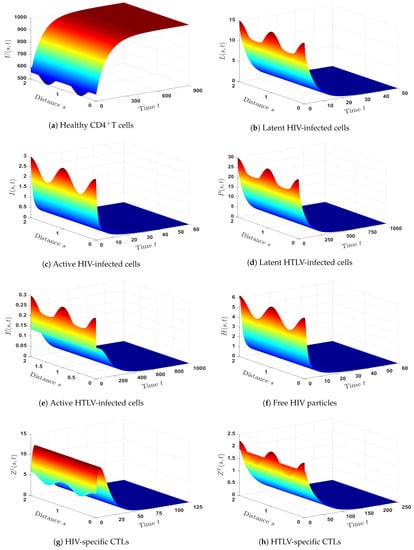

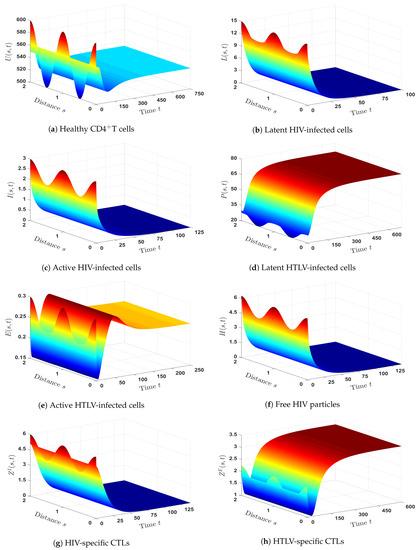

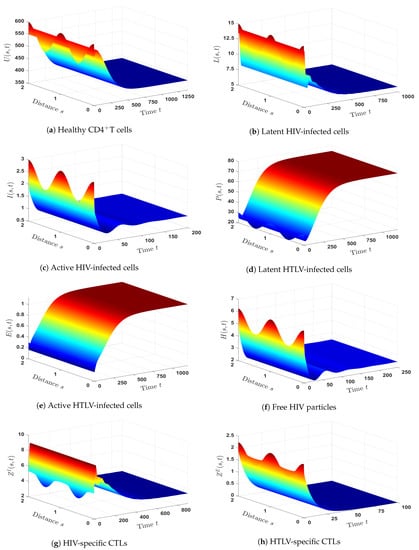

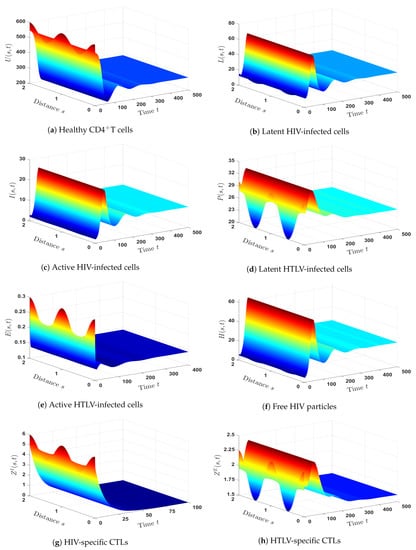

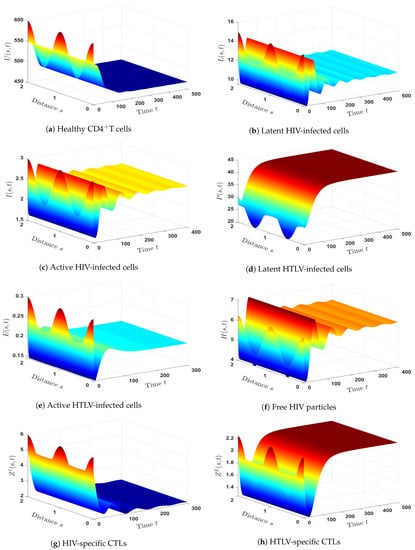

- We selected and. With such a choice, we obtained , , and hence, . Theorem 2 implies that is GAS, which is displayed in Figure 2. As a result, HIV mono-infection will persist, but with an inefficient CTL immune response.

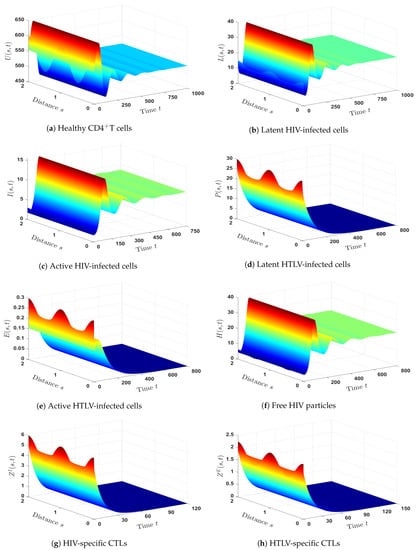

- (3)

- We set and . Then, we calculated , and then, . The numerical results showed that exists. Figure 3 illustrates that is GAS. It is evident from this that the numerical outcomes and the theoretical finding of Theorem 3 are consistent. Therefore, a persistent HTLV mono-infection with an inefficient CTL immunity is present.

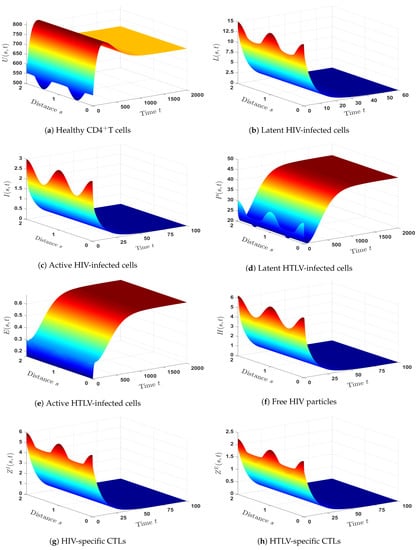

- (4)

- We took and to yield and . Figure 4 shows that is GAS based on Theorem 4. Therefore, a persistent HIV mono-infection with an efficient HIV-specific CTL immune response is reached.

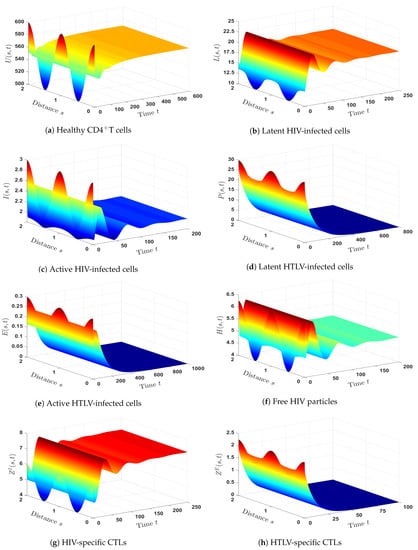

- (5)

- We set and . Then, we calculated and . According to these data, exists and is given by . In Figure 5, we show that is GAS, which is consistent with Theorem 5. There is a persistent HTLV mono-infection in this case, with efficient HTLV-specific CTL immunity.

- (6)

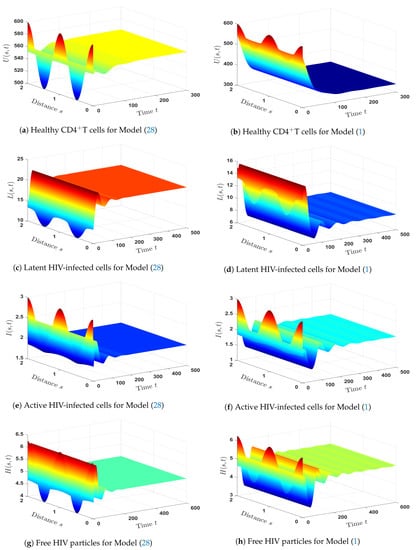

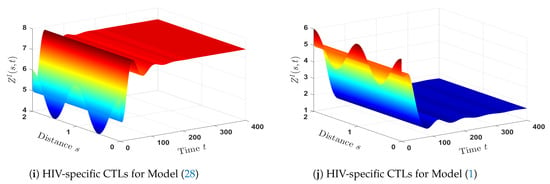

- We chose and . Hence, we have , , and . The numerical outcomes displayed in Figure 6 confirmed the existence and global stability of . Theorem 6 is, therefore, affirmed by this result. In this case, there is a persistent co-infection with HTLV and HIV together with an efficient HIV-specific CTL immunity, whereas the HTLV-specific CTL immunity is an inefficient.

- (7)

- We picked and . This gives , and . As can be seen from Figure 7, the equilibrium is GAS, and this is a confirmation of Theorem 7. In such a case, a persistent co-infection with HTLV and HIV occurs together with the effective HTLV-specific CTL immunity; however, the HIV-specific CTL immunity is not working.

- (8)

- We chose and . These data give and . Figure 8 illustrates that is GAS. Theorem 8 is, therefore, confirmed. Consequently, a persistent co-infection with HTLV and HIV occurs where the immune system is functioning well.

6.2. Comparison Study

We compare mono- and co-infection dynamics in this part, through studying the effect of one of the infections (HIV infection or HTLV infection) on the dynamical behavior of the other mono-infection as in the following points:

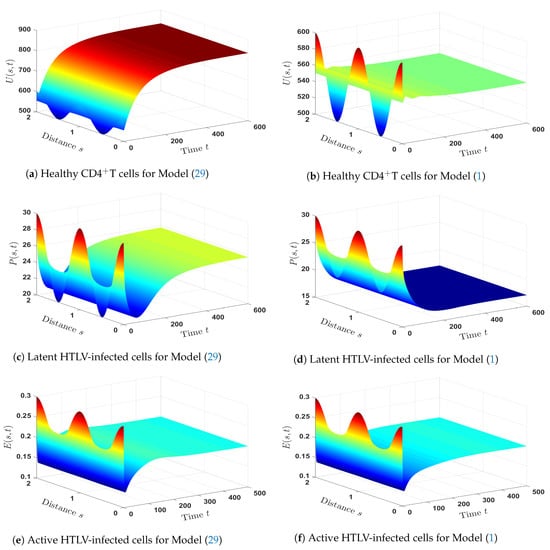

- (i)

- The impact of HTLV infection on the dynamical behavior of HIV mono-infection:The following HIV mono-infection model was compared with Model (1) in order to determine the impact of HTLV infections on HIV mono-infection dynamics:The comparison was made through the following considerations:

- The parameters , , , , and are fixed.

- We chose (in the case of HTLV/HIV co-infection dynamics).

As shown in Figure 9, patients with only HIV who are co-infected with HTLV have lower levels of CDT cells (both latent and healthy), as well as HIV-specific CTLs. On the other hand, the concentration of free HIV particles reaches the same level in both HIV mono-infection and HTLV/HIV co-infection. Actually, this finding is compatible with the results of a recently published paper [59], where the study indicated that there are no discernible contrasts between HIV mono-infected and HTLV/HIV co-infected in terms of the number of HIV particles. - (ii)

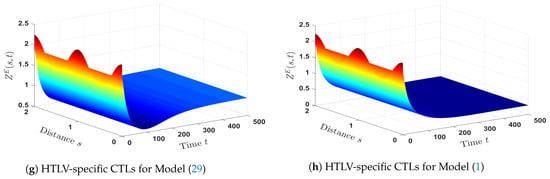

- The impact of HIV infection on the dynamical behavior of HTLV mono-infection:In order to know how HIV infection influences the HTLV mono-infection dynamics, we compared Model (1) with an HTLV mono-infection model as given below:To make the comparison, we took into account the following factors:

- The parameters , , and are fixed.

- We picked and (in the case of HTLV/HIV co-infection dynamics).

The solutions of Models (1) and (29) are shown by Figure 10. We noticed that, in the case of co-infection, the densities of CDT cells (both latent and healthy) and HTLV-specific CTLs are less than those in the case of HTLV mono-infection. However, both HTLV mono-infection and HTLV/HIV co-infection have the same level of density of active HTLV-infected cells.

7. Conclusions

In this work, we developed and analyzed the spatiotemporal dynamics of a mathematical PDE model for HTLV/HIV co-infection in the presence of three routes of transmission, which are FTC, latent ITC, and active ITC. The developed PDE model also incorporated latent infected cells, which represent reservoirs for both HTLV and HIV, as well as the cellular immunity mediated by CTL cells in order to control the HTLV/HIV co-infection. We first studied the properties of the solutions including the existence, uniqueness, non-negativity, and boundedness to guarantee that our developed model is biologically and mathematically well-posed. Furthermore, we proved that the dynamics of the model is fully determined by eight threshold parameters: , i = 1, 2,…, 8. More precisely, the infection-free equilibrium is globally asymptotically stable when and , which biologically means that both HIV and HTLV are cleared and the co-infection dies out. However, when or , one or both viruses persist in the host and seven steady states appear; their global stability conditions are summarized in Table 1.

The reaction in the present model was modeled by the classical temporal derivative, and the diffusion was described by the Laplacian operator. Further, the model considered only one arm of adaptive immunity. Therefore, the study of the impact of immunological memory on the dynamics of the PDEs model by means of the new generalized Hattaf fractional (GHF) derivative introduced in [60,61] and the modeling the role of the second arm of adaptive immunity exercised antibodies as in [62] will be the main aims of our future works.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.E.; Methodology, N.H.A. and A.A.R.; Formal analysis, A.E. and A.A.R.; Investigation, N.H.A.; Writing—original draft, N.H.A. and A.A.R.; Writing—review & editing, A.E. and K.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia, Project under Grant Number RGP.2/154/43.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia, for funding this work through the Research Group Project under Grant Number (RGP.2/154/43).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nowak, M.A.; Bangham, C.R.M. Population dynamics of immune responses to persistent viruses. Science 1996, 272, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Zou, X. Modelling HIV-1 virus dynamics with both virus-to-cell infection and cell-to-cell transmission. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 2014, 74, 898–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojaver, A.; Kheiri, H. Mathematical analysis of a class of HIV infection models of CD4+T-cells with combined antiretroviral therapy. Appl. Math. Comput. 2015, 259, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adak, D.; Bairagi, N. Analysis and computation of multi-pathways and multi-delays HIV-1 infection model. Appl. Math. Model 2018, 54, 517–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Qiu, Z. The effects of CTL immune response on HIV infection model with potent therapy, latently infected cells and cell-to-cell viral transmission. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2019, 16, 6822–6841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, J.F. Dynamics of two time delays differential equation model to HIV latent infection. Phys. A 2019, 514, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Tuerxun, N.; Teng, Z. The global dynamics in a wild-type and drug-resistant HIV infection model with saturated incidence. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2020, 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wang, W. Propagation of HBV with spatial dependence. Math. Biosci. 2007, 210, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.; Miao, H.; Chen, X.; Xu, J.; Huang, D. Global stability of a diffusive and delayed virus dynamics model with Crowley-Martin incidence function and CTL immune response. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2017, 2017, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCluskey, C.C.; Yang, Y. Global stability of a diffusive virus dynamics model with general incidence function and time delay. Nonlinear Anal. Real World Appl. 2015, 25, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, H.; Teng, Z.; Abdurahman, X.; Li, Z. Global stability of a diffusive and delayed virus infection model with general incidence function and adaptive immune response. Comput. Appl. Math. 2017, 37, 3780–3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perelson, A.S.; Essunger, P.; Cao, Y.; Vesanen, M.; Hurley, A.; Saksela, K.; Markowitz, M.; Ho, D.D. Decay characteristics of HIV-1-infected compartments during combination therapy. Nature 1997, 87, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perelson, A.S.; Nelson, P.W. Mathematical analysis of HIV-1 dynamics in vivo. SIAM Rev. 1999, 41, 3–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, L.; Perelson, A.S. Modeling latently infected cell activation: Viral and latent reservoir persistence, and viral blips in HIV-infected patients on potent therapy. J. Theor. Plos Comput. Biol. 2009, 5, e1000533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonomo, B.; Vargas-De-Leon, C. Global stability for an HIV-1 infection model including an eclipse stage of infected cells. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2012, 385, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigal, A.; Kim, J.T.; Balazs, A.B.; Dekel, E.; Mayo, A.; Baltimore, R.M.D. Cell-to-cell spread of HIV permits ongoing replication despite antiretroviral therapy. Nature 2011, 477, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, J.; Kuniya, T. Dynamics of a PDE viral infection model incorporating cell-to-cell transmission. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2016, 444, 1542–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Wang, J. Dynamics of a diffusive virus model with general incidence function, cell-to-cell transmission and time delay. Comput. Math. Appl. 2019, 77, 284–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Hou, J.; Geng, Y.; Zhang, S. Dynamic consistent NSFD scheme for a viral infection model with cellular infection and general nonlinear incidence. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2018, 2018, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agosto, L.; Herring, M.; Mothes, W.; Henderson, A. HIV-1-infected CD4+ T cells facilitate latent infection of resting CD4+ T cells through cell-cell contact. Cell 2018, 24, 2088–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaiw, A.M.; AlShamrani, N.H. Stability of a general CTL-mediated immunity HIV infection model with silent infected cell-to-cell spread. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2020, 2020, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, J. Threshold dynamics of a delayed nonlocal reaction–diffusion HIV infection model with both cell-free and cell-to-cell transmissions. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2020, 488, 124047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Teng, Z.; Miao, H. Global dynamics of a reaction–diffusion virus infection model with humoral immunity and nonlinear incidence. Comput. Math. Appl. 2019, 78, 786–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, T.; Teng, Z. Analysis of a diffusive virus infection model with humoral immunity, cell-to-cell transmission and nonlinear incidence. Phys. A 2019, 535, 122415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlAgha, A.D.; Elaiw, A.M. Stability of a general reaction–diffusion HIV-1 dynamics model with humoral immunity. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2019, 134, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaiw, A.M.; Agha, A.D.A. Stability of a general HIV-1 reaction–diffusion model with multiple delays and immune response. Phys. Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2019, 536, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, X.; Guo, K.; Ma, W. Global analysis of a diffusive viral model with cell-to-cell infection and incubation period. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2020, 43, 5963–5978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Tian, Y.; Liu, L.; Liu, X. A reaction–diffusion within-host HIV model with cell-to-cell transmission. J. Math. 2018, 2018, 1831–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-De-Leon, C. The complete classification for global dynamics of amodel for the persistence of HTLV-1 infection. Appl. Math. Comput. 2014, 237, 489–493. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, A.G.; Maini, P.K. HTLV-Iinfection: A dynamic struggle between viral persistence and host immunity. J. Theor. Biol. 2014, 352, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Chen, Y.; Shu, H. Rich dynamics in a delayed HTLV-I infection model: Stability switch, multiple stable cycles, and torus. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2019, 479, 2214–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Xu, D. Complete dynamical analysis for a nonlinear HTLV-I infection model with distributed delay, CTL response and immune impairment. Discret. Contin. Dyn. 2020, 25, 917–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Heffernan, J.M. Viral dynamics of an HTLV-I infection model with intracellular delay and CTL immune response delay. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2018, 459, 506–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Ma, W. Dynamics analysis of an HTLV-1 infection model with mitotic division of actively infected cells and delayed CTL immune response. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2018, 41, 3000–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhou, Y. Backward bifurcation of an HTLV-I model with immune response. Discret. Contin. Dyn. Syst. Ser. B 2016, 21, 863–881. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Ma, W. Global dynamics of a reaction and diffusion model for an HTLV-I infection with mitotic division of actively infected cells. J. Appl. Anal. Comput. 2017, 7, 899–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casoli, C.; Pilotti, E.; Bertazzoni, U. Molecular and cellular interactions of HIV-1/HTLV coinfection and impact on AIDS progression. AIDS Rev. 2007, 9, 140–149. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, M.T.; Espíndola, O.D.; Leite, A.C.; Araújo, A. Neurological aspects of HIV/human T lymphotropic virus coinfection. AIDS Rev. 2009, 11, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Brites, C.; Sampalo, J.; Oliveira, A. HIV/human T-cell lymphotropic virus coinfection revisited: Impact on AIDS progression. AIDS Rev. 2009, 11, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Isache, C.; Sands, M.; Guzman, N.; Figueroa, D. HTLV-1 and HIV-1 co-infection: A case report and review of the literature. IDCases 2016, 4, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beilke, M.A.; Theall, K.P.; O’Brien, M.; Clayton, J.L.; Benjamin, S.M.; Winsor, E.L.; Kissinger, P.J. Clinical outcomes and disease progression among patients coinfected with HIV and human T lymphotropic virus types 1 and 2. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004, 39, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaiw, A.M.; AlShamrani, N.H. Analysis of a within-host HIV/HTLV-I co-infection model with immunity. Virus Res. 2020, 295, 198204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaiw, A.M.; AlShamrani, N.H.; Hobiny, A.D. Mathematical modeling of HIV/HTLV co-infection with CTL-mediated immunity. AIMS Math. 2021, 6, 1634–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaiw, A.M.; AlShamrani, N.H. Stability of HTLV/HIV co-infection model with mitosis and latency. Math. Eng. 2021, 18, 1077–1120. [Google Scholar]

- Elaiw, A.M.; AlShamrani, N.H. Analysis of an HTLV/HIV co-infection model with diffusion. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2021, 18, 9430–9473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Guo, Z.; Peng, H. Dynamical behavior of a new oncolytic virotherapy model based on gene variation. Discret. Contin. Dyn. Syst. Ser. S 2017, 10, 1079–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Xu, Y. Stability of a CD4+ T cell viral infection model with diffusion. Int. J. Biomath. 2018, 11, 1850071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, Z. Dynamics of a diffusive HBV model with delayed Beddington-DeAngelis response. Nonlinear Anal. Real World Appl. 2014, 15, 118–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.L. Monotone Dynamical Systems: An Introduction to the Theory of Competitive and Cooperative Systems; American Mathematical Society: Providence, TX, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Protter, M.H.; Weinberger, H.F. Maximum Principles in Differential Equations; Prentic Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, D. Geometric Theory of Semilinear Parabolic Equations; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Elaiw, A.M.; AlAgha, A.D. Global dynamics of reaction–diffusion oncolytic M1 virotherapy with immune response. Appl. Math. Comput. 2020, 367, 124758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaiw, A.M.; AlAgha, A.D. Analysis of a delayed and diffusive oncolytic M1 virotherapy model with immune response. Nonlinear Anal. Real World Appl. 2020, 55, 103116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbashin, E.A. Introduction to the Theory of Stability; Wolters-Noordhoff: Groningen, The Netherlands, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- LaSalle, J.P. The Stability of Dynamical Systems; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Lyapunov, A.M. The General Problem of the Stability of Motion; Taylor & Francis, Ltd.: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Maziane, M.; Lotfi, E.M.; Hattaf, K.; Yousfi, N. Dynamics of a class of HIV infection models with cure of infected cells in eclipse stage. Acta Biotheor. 2015, 63, 363–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elaiw, A.M.; Agha, A.D.A. Global Stability of a reaction–diffusion malaria/COVID-19 coinfection dynamics model. Mathematics 2022, 10, 4390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandormael, A.; Rego, F.; Danaviah, S.; Alcantara, L.C.; Boulware, D.R.; de Oliveira, T. CD4+ T-cell count may not be a useful strategy to monitor antiretroviral therapy response in HTLV-1/HIV co-infected patients. Curr. HIV Res. 2017, 15, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hattaf, K. On the stability and numerical scheme of fractional differential equations with application to biology. Computation 2022, 10, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattaf, K. A New generalized definition of fractional derivative with non-singular kernel. Computation 2020, 8, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattaf, K.; Karimi, M.I.E.; Mohsen, A.A.; Hajhouji, Z.; Younoussi, M.E.; Yousfi, N. Mathematical modeling and analysis of the dynamics of RNA viruses in presence of immunity and treatment: A case study of SARS-CoV-2. Vaccines 2023, 11, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).