Abstract

In this paper, we construct two new families of distributions generated by the discrete Lindley distribution. Some mathematical properties of the new families are derived. Some special distributions from these families can be constructed by choosing some baseline distributions, such as exponential, Pareto and standard logistic distributions. We study in detail the properties of the two models resulting from the exponential baseline, among others. These two models have different shape characteristics. The model parameters are estimated by maximum likelihood, and related algorithms are proposed for the computation of the estimates. The existence of the maximum-likelihood estimators is discussed. Two applications prove its usefulness in real data fitting.

Keywords:

discrete lindley distribution; EM algorithm; existence of the maximum likelihood estimate; moments MSC:

62E15; 62F10; 60E05

1. Introduction

Compound discrete distributions serve as probabilistic models in various areas of applications, for instance, in ecology, genetics and physics. See, for example, [1]. Distributions obtained by compounding a parent distribution with a discrete distribution are very common in statistics and in many applied areas. Suppose we have a system consisting of N components, the lifetime of each of which is a random variable. Let X be the maximum lifetime of the components. Clearly, X has a compound distribution arising out of a random number N of components; i.e., . On the other hand, in case of a system consisting of N components whose energy consumption is a random variable, and assuming that Z is the component whose energy consumption is minimal, we obtain the compound distribution of The compounding principle is applied in the many different areas: insurance [2], ruin problems [3], compound risk models and their actuarial applications [4,5]. The development of the theory of compounding distribution is skipped here, because it has been covered in detail in [6].

The random variable N is often determined by economy, customer demand, etc. There is a practical reason why N might be considered as a random variable. A failure can occur due to initial defects being present in the system. A discrete version of this distribution has been studied in [7], having its applications in count data related to insurance.

We will say that random variable X possesses the discrete Lindley distribution introduced by [7] if its probability mass function is given by

where and The probability generating function (PGF) (see Equation (4) in [7]) is given by the typo error. The corrected version is defined by

In this manuscript, we consider the previously discrete Lindley distribution for the random variable Why do we assume a discrete Lindley distribution? For example, using a Poisson distribution has an important assumption: equidispersion of data. The assumption of equidispersion is not valid in real cases. Some alternative distributions to the model of overdispersed data are available—binomial negative, generalized Poisson or zero inflated Poisson. However, judging by the number of parameters used, these alternatives are more complex than the Poisson distribution. That is why we are introducing a continuous Lindley distribution with one parameter, which is similar to the Poisson distribution. The application of the Lindley distribution in modeling the number of claim data is less suitable because the number of claims data is a discrete number, as opposed to the Lindley distribution’s continuous nature. That is why we are introducing a new discrete Lindley distribution, created through discretisation of a continuous Lindley distribution with one parameter.

Assuming that M is the zero truncated version of N with PGF (1), we will construct two new families of distributions: the discrete Lindley-generated families of distributions of the first and second kinds.

The paper is organized as follows. In Section 1, we construct two discrete Lindley generated families. Section 2 is devoted to shape characteristics. In Section 3 we derive some mathematical properties of the families. Estimation issues are investigated in Section 4 and Section 5. The simulation study is presented in Section 6. Two applications to real data are addressed in Section 7. The paper is finalized with concluding remarks.

2. Construction of the Families of Distributions

There are various methods for getting the discrete Lindley distribution. For example, in [8], the authors considered a method of infinite series for constructing the discrete Lindley distribution. On the other hand, in [9], the discrete Lindley distribution was built using the survival function method. In this manuscript, we employ the so-called max-min procedure. This construction is widely used in practice. For a comprehensive literature review, we refer the reader to [10] and references therein.

In this section, we introduce two new families of distributions as follows. Let be a sequence of independent and identically distributed (iid) random variables with baseline cumulative distribution function (CDF) , where and is the parameter vector. Suppose that N is a discrete random variable with the PGF and let M have the zero-truncated distribution of the random variable N obtained by removing zero from N. Then, the probability mass function (pmf) of M is given by

In order to prove that , let us recall that . After some algebra, we find

Using serial representations and , one can calculate

Equation (3) coincides with This completes the proof that

First, we introduce the family of distributions based on the maximum of random variables. We define the random variable . Then, the CDF and probability density function (PDF) of X are given by

and

respectively.

Further, if we suppose that the random variable N has the PGF given by (1), the CDF and PDF of X for are given by

and

respectively. We say that the family of distributions defined by (4) and (5) is the discrete Lindley generated family of the first kind (“LiG1” for short). A random variable X having PDF (5) is denoted by LiF1.

The hazard rate function (HRF) of X can be expressed as

Let us study the identifiable property of the distribution given by (4) under the exponential baseline distribution . We will get the discrete Lindley exponential distribution of the first kind. We will designate this distribution LiE1.

Theorem 1.

The LiE1 distribution is identifiable with respect to the parameters λ and

Proof.

Let us suppose that

for all and when is the CDF of exponential distribution. If we let into both sides of (7) and after some algebra, it can be concluded that . Now it is not hard to verify that Hence the proof of the theorem. □

Second, in [6], it was demonstrated that the random variable has CDF and PDF given by

and

respectively.

Now, inserting (1) in Equation (8), the CDF of the random variable Y becomes

where is the survival function of the random variable .

In a similar manner, by replacing (1) in the Equation (9), the PDF of Y reduces to

The random variable Y having the PDF (11) is called the discrete Lindley generated family of the second kind, LiF2.

There are at least four motivations for having two families of distributions: Reliability: From the stochastic representations X and Y, we note that the two families can arise in parallel and series systems with identical components, which appear in many industrial applications and biological organisms. The first-activation scheme: If we assume that an individual is susceptible to a cancer type, then we can call the number of carcinogenic cells that survived the initial treatment M, and is the time needed for the th carcinogenic cell to metastasise into a detectable tumour, for . If we assume that is a sequence of a total of iid random variables, all independent of M, where M is given by (2), we can conclude that the time to relapse of cancer of a susceptible individual is defined by the random variable Y. Last-activation scheme: Let us assume that M equals the number of latent factors that have to be active by failure, and is the time of disease resistance due to the latent factor i. According to the last-activation scheme, the failure occurs once all N factors are active. If the s are iid random variables that are independent of N having the baseline distribution F, where N follows (2), the random variable X can model time to the failure according to the last-activation scheme. The times to the last and first failures: Let us assume that the device failure happens due to initial defects numbering M, and that these can be identified only after causing the failure, and that they are being repaired perfectly. We will define as the time to the device failure due to the defect number i, where . Under the assumptions that the s are iid random variables independent of M given by (2), the random variables X and Y are appropriate for modeling the times to the last and first failures.

3. Shape Characteristics of the Proposed Models under the Exponential Baseline Distribution

Let us examine the shapes of the PDF and HRF for the case of the exponential baseline distribution. Let the random variables have the exponential distribution with scale parameter . If we set and replace it in (5), we will get the LiE1 distribution. Its PDF is for

The exponential distribution is widely used due to its simplicity and applicability. For its usage in the theory of the compounding distribution, we recommend [10], where it is possible to find a long list of the corresponding references.

In order to study the shape of the last PDF, firstly we will give the following example. The next example will serve us to prove Theorem 2. It will play a crucial role in the study of the inequality that is important for drawing the conclusion about the PDF’s shape.

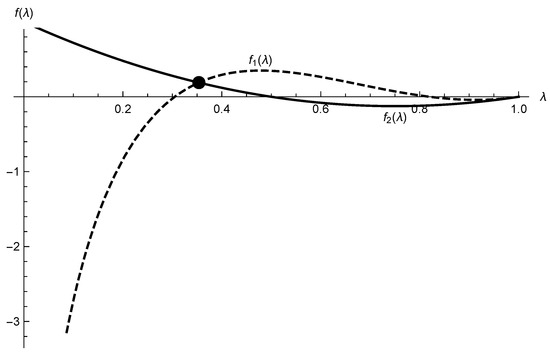

Example 1.

Suppose Find λ such that

Solution: An analytical solution of the above inequality is not possible, so we will use numerical algorithms. Let us consider the corresponding equation Using function Solve in Mathematica software ([11]), we get that Furthermore, using the function Reduce we see that for the inequality holds. The graphical solution is given in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Graphical solution of the inequality where and .

Theorem 2.

The PDF of LiE1 with parameters and is unimodal if Otherwise, it is decreasing.

Proof.

The first derivative of the logarithm of the PDF can be represented in the form

where , and . We transform the function to a quadratic function , . Let and represent the roots of the equation . Some calculations indicate that , , and Thus,

so we have and After some calculations, it can be shown that discriminant is positive and that is concave. We need to find when solution If we set , one gets

If , then

It is not difficult to verify that the right-hand side of the last inequality is positive and we can quadrate (13). Then, the inequality (13) reduces to

Now, the assertion of the first part of Theorem follows from Example 1.

In case , is always positive on the interval , and hence the PDF is decreasing. □

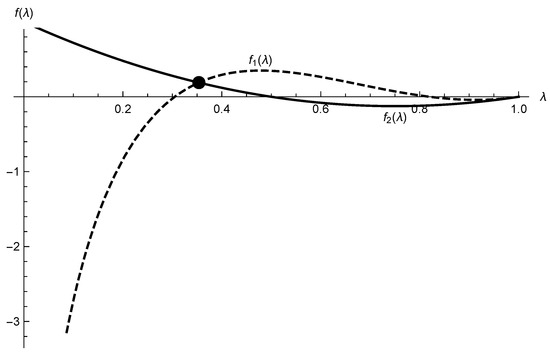

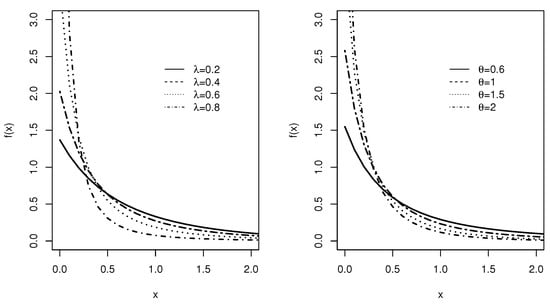

Different shapes of the PDF in cases of LiE1 model are given in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The plots of the density function of the LiE1 distribution for various choices of parameters with (left) and (right).

The HRF of the LiE1 distribution is

Determining the shape of a HRF of a distribution is an important issue in statistical reliability and survival analysis. We give it for the LiE1 model in the following theorem.

Theorem 3.

The HRF of the LiE1 with parameters and is an increasing function.

Proof.

The first derivative of the can be represented as

where a and b were defined in Theorem 2, and . After extensive calculations, it can be shown that

Again, using the transformation where , we get quadratic equation with

Thus, we have The function is concave, and it holds that for all Finally, the HRF is increasing. Hence, we proved Theorem. □

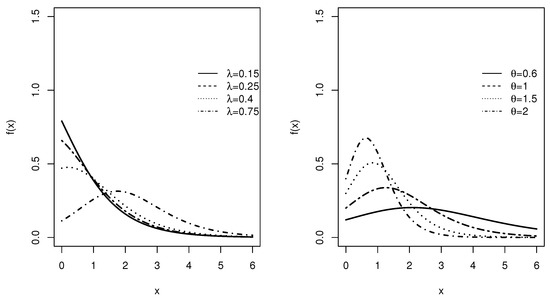

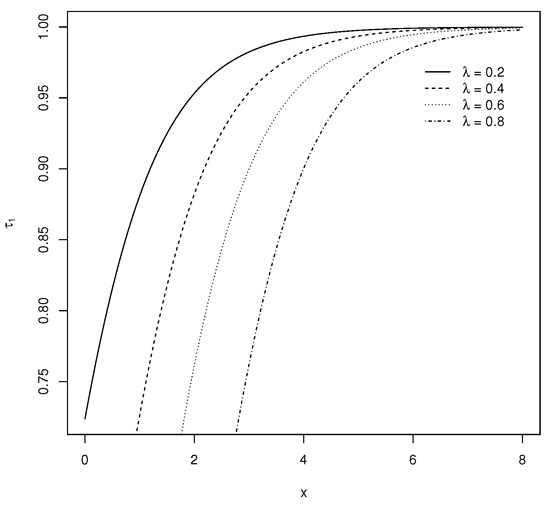

Different shapes of the HRF in the case of the LiE1 model are outlined in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The plots of the HRF of the LiE1 distribution for various choices of parameter with .

Now, we will study the shapes of the discrete Lindley exponential distribution of the second kind (LiE2) of distribution. By replacing in Equation (11), we obtain the PDF of the LiE2 distribution as

The shapes of the LiE2 distribution are given by the following theorem.

Theorem 4.

The PDF of the LiE2 with parameters and is a decreasing function with and .

Proof.

Similarly to in Theorem 2, we have

where , and . We can prove that is positive for all . Letting , we transform the function to a quadratic function ; . Let represent the roots of the equation . Since we have , and ,

which implies . Since and the discriminant is positive, it follows that is concave and positive on , which means that is positive for . Finally, is positive for all and . □

The HRF of the LiE2 distribution for is given by

The shape of the HRF of the LiE2 distribution is given in the following theorem.

Theorem 5.

The HRF of the LiE2 distribution with parameters and is an increasing function with and .

Proof.

We consider the logarithm of the HRF . Its first derivative can be expressed as

where a and b are defined as in the proof of the previous theorem, and . By letting , we transform the function to the quadratic function ; . As before, let be the roots of the equation . Some calculations indicate that , , and , which implies that

Thus, two cases can be considered, and . The first case is not possible, since

which follows from the fact that . Thus, . Since and the discriminant is positive, it follows that is a convex function and positive on . This implies that is positive for all . Finally, , which means that the HRF is an increasing function. □

Using similar calculations, we can derive the shapes of the PDF and HRF of X and Y given by (5), (6), (11) and (12), respectively, under various baseline distributions.

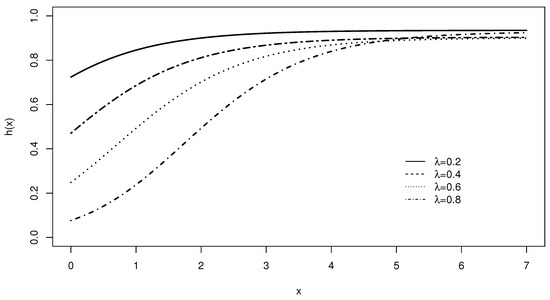

Figure 4 represents plots of the LiE2 density function, while on Figure 5 we have plots of the LiE2 hazard rate functions for various parameter values.

Figure 4.

The plots of the density function of the LiE2 distribution for various choices of parameters with (left) and (right).

Figure 5.

The hazard plots of the LiE2 distribution for various choices of parameter with .

Theorem 6.

The LiE2 distribution function is identifiable with respect to the parameters θ and λ.

Proof.

As was the case in the proof of Theorem 1, we will assume that for all and is the CDF of an exponential distribution. As a consequence, we have Then, from Theorem 5, we have that when Now, since after some algebra, it can be shown that from follows □

4. Some Mathematical Properties

4.1. Mixture Representations

In this section, we obtain a very useful representation for the LiG1 density function. For and , we can write

where and is the gamma function. For , we can apply (14) in Equation (5) to obtain

where , and

Henceforth, as a random variable will be said to have the exponentiated-F (“exp-F”) distribution, its power parameter being , say, , if its PDF and CDF are given by

respectively.

Then, using the exp-F distribution, we can write Equation (15) as

where , , (for ) and .

Equation (16) is this section’s main result. It shows that the LiF1 family density function is a mixture of ditributions. Therefore, there are structural properties (for instance incomplete and ordinary moments, generating functions, mean deviations) of the LiF1 family that can be obtained from the corresponding properties of the exp-G distribution. The exp-F mathematical properties have been studied by many authors in recent years, such as Nadarajah and Kotz (2006). In the following sections, we provide some mathematical properties of the LiG1 family distribution.

4.2. Moments

Henceforth, let have the the exp-F density with power parameter , say, exp-F. A first formula for the nth moment of the LiF1 family can be obtained from (16) as

Nadarajah and Kotz [12] provide explicit expressions for moments of some exponentiated distributions. They can be used to produce .

A second formula for can be obtained from (17) in terms of the baseline quantile function (qf) . We obtain

where the integral can be expressed as a function of the F quantile function (qf), say, , as .

Even though there is an infinite sum in the moments’ equation, it is not difficult to calculate its values. For example, if we set an error to , then four iterations would be enough for moments’ calculation.

Equations (17) and (18) can be used to directly determine the ordinary moments of some LiF1 distributions. Three examples will be provided here. Here, we consider three examples. LiE1 distribution moments (with scale parameter from the exponential baseline distribution) are given by

Particularly, we have

where is the digamma function defined by .

For the discrete Lindley Pareto of the first kind (LiPa1) of distribution, the baseline distribution is , and we have

where is the standard beta function.

For the discrete Lindley standard logistic of the first kind (LiSL1) of distribution, the baseline distribution is and . Using an integral result from [13], we have

where

Further, central moments, that is, moments around the mean, can also be computed. The relation between the central moments () and the moments about the origin are given by

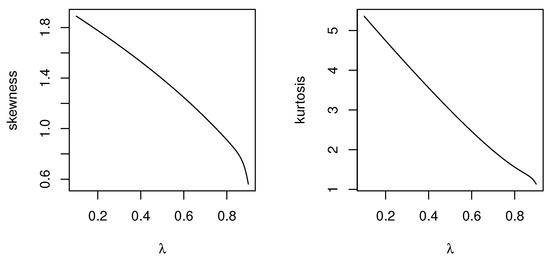

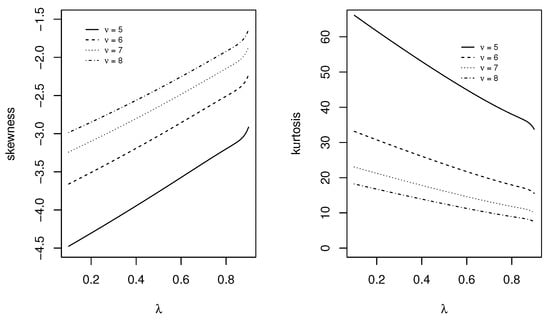

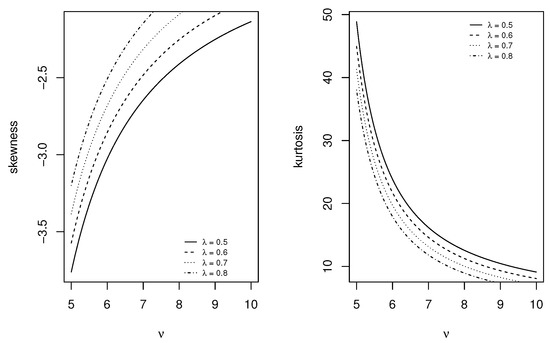

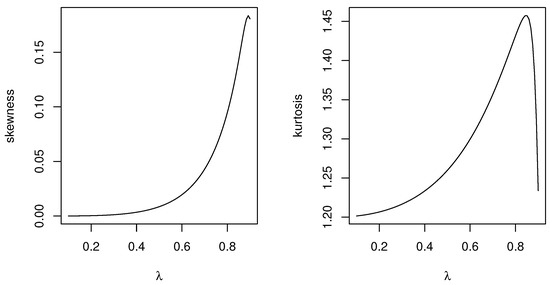

The cumulants of the distribution can also be computed together with the skewness and kurtosis measures. For this approach, we refer the reader to [14]. The skewness and kurtosis plots for these distributions are sketched in Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9. We observe that various skewness and kurtosis values can be obtained from these models.

Figure 6.

Skewness and kurtosis plots of the LiE1 distribution as a function of parameter .

Figure 7.

Skewness and kurtosis plots of the LiPa1 distribution as a function of parameter .

Figure 8.

Skewness and kurtosis plots of the LiPa1 distribution as a function of parameter .

Figure 9.

Skewness and kurtosis plots of the LiSL1 distribution as a function of parameter .

4.3. Generating Function

As far as the moment generating function (mgf) of X is concerned, we will provide two formulae. The first formula comes from (16) as

where is the mgf of . Therefore, is determined by the generating function of the distribution. The second M(t) formula is derived from (16)

where can be calculated from as

4.4. Incomplete Moments and Mean Deviations

The shapes of many of the distributions can, for empirical reasons, be conveniently described as incomplete moments. Such moments are important in measuring inequality, such as income quantiles and Lorenz and Bonferroni curves, which depend on the distribution incomplete moments. The th incomplete moment of the random variable X is defined as

The integral in (22) can be computed in the closed-form for several baseline F distributions.

The mean deviations about the mean () and about the median () of X can be expressed as and , respectively, where , is the median of X computed from

is easily calculated from (4) and is the first exp-F incomplete moment.

We will provide two ways to compute and . In the first instance, we can derive a general equation for from (16) by setting as

where

Equation (24) provides the basic quantity for computing the mean deviations of the exp-F distributions. Hence, the mean deviations and depend only on the exp-F mean deviations. Thus, alternative representations for and are given by and .

In a similar way, the mean deviations of any LiF1 distribution can be computed from Equations (23) and (24). For example, the mean deviations of the LiE1 (with parameter ), LiPa1 (with parameter ) and LiSL1 are determined immediately (by using the generalized binomial expansion) from the functions

and

and

respectively.

Bonferroni and Lorenz curves defined can be given to obtain for a given probability by and , respectively, where and is the LiG1-F qf at

5. On the Maximum-Likelihood Estimation of Parameters

We propose to use the maximum likelihood (ML) estimation method for the parameter estimation of the introduced distributions. The log-likelihood function for the general case (5) is given by

In this special case, we consider the exponential baseline distribution. Thus, for the LiE1 model, the estimating equations are given by

Now, we will study the existence of the ML estimators when the other parameter is known in advance (or given).

Theorem 7.

If the parameter λ is known, then the Equation (25) has at least one root in the interval

Proof.

One can readily verify that and Thus, there exists at least one root of the Equation (25). □

Theorem 8.

Assuming that

and if the parameter θ is known, then (26) has at least one root on the interval

Proof.

Applying L’Hôpital’s rule, we get and

In order to have at least one solution, it is necessary to have . Hence the theorem. □

On the other hand, the estimating equations for the LiE2 model are given by

The next two theorems examine the existence problem of the ML estimates via (27) and (28). Their proofs are very similar to those cases of Theorems 7 and 8, so we here omit them.

Theorem 9.

If the parameter λ is known, then the Equation (27) has at least one root on the interval

Theorem 10.

If the parameter θ is known and if it is assumed that

then the Equation (28) has at least one root on the interval

Clearly, the log-likelihood estimating equations for the parameters are nonlinear in the sense that the estimators cannot be obtained in closed forms. Thus, a numerical iterative method such as the Newton–Raphson one should be used in the estimation.

6. Estimation of Parameters via the EM Algorithm

We propose to use the method of maximum likelihood in estimating the parameters of the introduced models. The construction method of the models suggests using an EM (expectation maximization) algorithm. In this section, we provide EM algorithms for the estimation of the unknown parameters and for both exponential-discrete Lindley distributions.

6.1. EM Algorithm for the LiE1 Model

The missing data random variable will be the random variable M with the zero-truncated discrete Lindley distribution. Let us derive its probability mass function as

where N is a random variable with the discrete Lindley distribution with the parameter . Next, the random variable for a given has the CDF . Then, the PDF of the complete-data distribution is given by

The marginal PDF of X is given by

Then, the conditional PDF of M for given is given by

where .

The E-step of the EM algorithm requires the computation of the conditional expectation of the random variable M for a given . Now, we have

where .

In the M-step, we consider the complete data log-likelihood function, which is given by

Maximizing the log-likelihood function , the obtained estimates in the iteration are given by

where is the sample mean and

The solutions for these equations can be found using an iterative numerical process. For example, one can use the uniroot function in R (R Core Team, 2020).

6.2. EM Algorithm for the LiE2 Model

In this case, the random variable for a given has the exponential distribution with the scale parameter . Thus, the PDF of the hypothetical complete-data distribution is

Following some calculations, we can deduce that the marginal PDF of the random variable Y is given by

which implies that the conditional PDF of M for given has the form

The E-step of the EM algorithm requires the computation of the conditional expectation of the random variable M for a given . We have that

In the M-step, we need the complete data log-likelihood function, which is given by

By maximizing the log-likelihood function , we obtain the estimates in the iteration as follows:

where

7. Simulation Study

In this section, we consider LiE1 and LiE2 models and present a simulation study testing the performances of the estimators using the EM algorithm. We generated 10,000 random samples in batches of 50, 100 and 200 from both models.

We can generate random numbers from the distribution by using the inverse transform method. Let u be a random number from the uniform distribution on . Employing some algebra, we have , a number from the distribution. Here,

where , , and .

Similarly, we can generate random numbers from the distribution by using the inverse transform method. Let u be a random number from the uniform distribution on . Following some calculations, we have , a number from the distribution. Here,

where and .

We used R (R Core Team, 2020) with uniroot to run the EM algorithms. We took the parameter values as the starting points for the iterations in the algorithms. The algorithms stopped when . The simulation results of the empirical means and mean square errors (MSEs) are reported in Table 1 and Table 2. We observe that the estimates are close to the parameter values and the MSEs decrease with increasing sample size. This makes the use of the EM algorithm plausible for estimation.

Table 1.

Empirical means and MSEs of the maximum-likelihood estimates of the LiE1 for different values of the parameters.

Table 2.

Empirical means and the MSEs of the maximum-likelihood estimates of the LiE2 for different values of the parameters.

8. Real Data Fitting

In this section, we investigate the performance of the introduced distributions in data fitting. We also compare them with their natural competitor, that is, the generalized exponential (GE) distribution studied in [15]. The GE distribution was proposed as an alternative to exponential, gamma and Weibull distributions. A lot of work in the literature has shown that it is a flexible model with reverse J-shaped and positively skewed unimodal data fitting. The PDF of the GE distribution is given by

We consider the maximum likelihood method in the estimation. Since we compare the models, we used the direct maximization of the respective log-likelihood functions.

8.1. Carbon Data Set

Let us consider a data set (uncensored) from [16], which includes 100 observations regarding breaking stress of carbon fibers in Gba. The data are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Data on the breaking stress of carbon fibers.

The data were also used in [17].

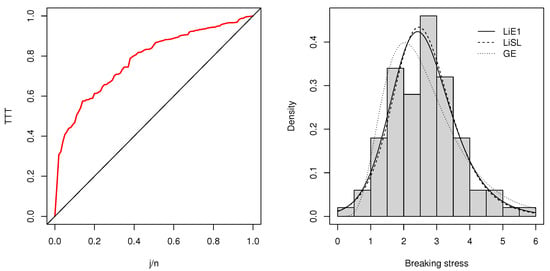

We used the LiE1 distribution in fitting instead of LiE2, since the data exhibits a unimodal shape (see Figure 10). One can also use the total time test (TTT) plot procedure to determine an appropriate model shape.

Figure 10.

TTT plot of the data set (on the left) and several fits for the Carbon data (on the right).

The TTT plots were introduced by [18] for model identification purposes, that is, for choosing a suitable lifetime distribution. These plots were studied in detail by [19]. Let denote the ordered observations from the random sample of size n. The TTT plot is obtained in the following way:

- Let .

- Calculate the TTT values for .

- Obtain the normalized TTT values by for .

- Plot the points for , and then join them by line segments.

A TTT plot is a diagnostic tool in the sense that it gives an insight about the aging properties of the underlying distribution. Then, one can choose an appropriate lifetime distribution for modeling the data. For example, when the plot is concave, a life distribution with an increasing failure rate should be used. The TTT plot for the Carbon data set is sketched in the lhs of Figure 10. It can be seen that it is concave. Thus, a model with increasing failure rate like LiE1 should be used.

Further, the HRF can not only be increasing, but also be constant, decreasing or even a U-shaped. These futures may also be inferred from the TTT plot. The HRF is constant when the TTT plot is straight diagonal, decreases when the TTT plot is convex and is U-shaped if the TTT plot is S-shaped—that is, first convex and then changed to a concave shape. When the ordering is reversed in the S-shaped case, a HRF with a unimodal characteristic is obtained.

Alternatively, we also fit LiSL1 and GE distributions to this data set and computed the parameter estimates using the optim function in R [20]. The results are reported in Table 4. We observe that the Lie1 distribution is better than the others according to the Akaike information criterion (AIC). The Kolmogorov–Simirnov test statistic was 0.074605 with p-value 0.6338. Figure 10 also supports this good fit. On the other hand, the EM algorithm gave and , which are similar values to those obtained from direct maximization.

Table 4.

Maximum-likelihood estimates with standard errors in parentheses, log-likelihood and AIC values for Carbon data.

8.2. Failure Data Set

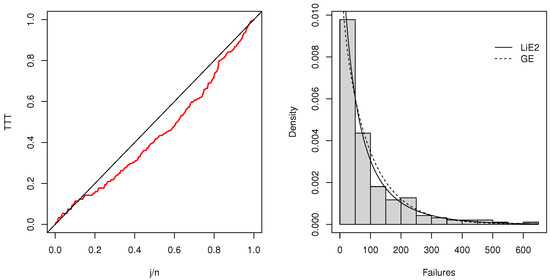

The data set is based on the number of successive failures of air conditioning systems on 13 Boeing 720 air planes. The data set is from [21] and was recently analyzed in [22]. Since the data exhibit a reversed J-shape (see Figure 11), we used the LiE2 distribution in fitting. TTT plot sketched in the lhs of Figure 11 also supports this conjecture, since it produces a convex shape.

Figure 11.

TTT plot of the data set (on the left) and two competing fits for the Failure data (on the right).

For convenience, the data are given Table 5.

Table 5.

Data on the successive failures for the air conditioning system of each member in a fleet of 13 Boeing 720 jet air planes.

The fitting results are given in Table 6. According to the AIC, the LiE2 fit is better than the GE fit. The Kolmogorov–Simirnov test statistic is with a p-value of . In addition, the EM algorithm gave and , which are close to those obtained from direct maximization.

Table 6.

Maximum-likelihood estimates with standard errors in parentheses, log-likelihood and AIC values for failure data.

9. Conclusions

In this manuscript, we constructed two general probability distribution families using the discrete Lindley distribution. The families contain a baseline distribution which can be manipulated by the user to obtain probability distributions of different shapes. The resulting distributions are not so complex in the sense that the number of parameters of the baseline distribution is increased by one only. As an alternative to the direct maximization of the log-likelihood, we constructed an EM algorithm to compute the ML estimates of the parameters. We mainly focused on the exponential baseline distribution and used the newly defined distributions in real data fitting.

As a part of further research, the introduced distributions may be studied in detail using other simple baseline distributions like Pareto. Also, the Marshall-Olkin approach of construction of bivariate distributions can be used to define the bivariate extensions of the models introduced.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K. and B.V.P.; methodology, S.K., B.V.P. and A.İ.G.; software, A.İ.G.; validation, S.K., B.V.P. and A.İ.G.; investigation, B.V.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sets are given in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Johnson, N.L.; Kemp, A.W.; Kotz, S. Univariate Discrete Distributions; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Zhang, L.; Sun, W. Risk model based on the first-order integer-valued moving average process with compound Poisson distributed innovations. Scand. Actuar. J. 2018, 5, 412–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmussen, S. Ruin Probabilities; World Scientific Publishing: Singapore, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Klugman, S.; Panjer, H.H.; Willmot, G.E. Loss Models: From Data to Decisions; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Panjer, H.H.; Willmot, G.E. Insurance Risk Models; Society of Actuaries: Schaumburg, IL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Nadarajah, S.; Popović, B.V.; Ristić, M.M. Compounding: An R package for computing continuous distributions obtained by compounding a continuous and a discrete distribution. Comput. Stat. 2013, 28, 977–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Déniz, E.; Calderín-Ojeda, E. The discrete Lindley distribution: Properties and applications. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 2011, 81, 1405–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, B.; Shanker, R.A. A discrete lindley distribution with applications in biological sciences. Biom. Biostat. Int. J. 2018, 7, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.P.; Mazucheli, J.; Achcar, J.A. A comparative study between two discrete Lindley distributions. Cienc. Nat. 2017, 39, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tahir, M.H.; Cordeiro, G.M. Compounding of distributions: A survey and new generalized classes. J. Stat. Distrib. Appl. 2016, 3, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfram Research, Inc. Mathematica, Version 9.0.; Wolfram Research, Inc.: Champaign, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nadarajah, S.; Kotz, S. The Exponentiated Type Distributions. Acta Appl. Math. 2006, 92, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazauskas, V. Information matrix for Pareto (IV), Burr, and related distributions. Commun. Stat.-Theory Methods 2003, 32, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, G.M.; Brito, R.S. The Beta Power distribution. Braz. J. Probab. Stat. 2012, 26, 88–112. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, R.D.; Kundu, D. Generalized exponential distributions. Aust. N. Z. J. Stat. 1999, 41, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, M.D.; Padgett, W.J. A Bootstrap control chart for Weibull percentiles. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2006, 22, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemonte, A.J.; Cordeiro, G.M. The exponentiated generalized inverse Gaussian distribution. Stat. Probab. Lett. 2011, 81, 506–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, R.E.; Campo, R. Total time on test processes and applications to failure data analysis. In Reliability and Fault Tree Analysis; Barlow, R.E., Fussell, J., Singpurwalla, N.D., Eds.; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1975; pp. 451–481. [Google Scholar]

- Klefsjö, B. TTT-plotting—A tool for both theoretical and practical problems. J. Stat. Plan. Inference 1991, 29, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2020; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- Proschan, F. Theoretical explanation of observed decreasing failure rate. Technometrics 1963, 5, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saiary, Z.A.; Bakoban, R.A. The Topp-Leone generalized inverted exponential distribution with real data applications. Entropy 2020, 22, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).