Abstract

In this research, for a given time interval, which is the general period of melanoma treatment, a bilinear control model is considered, given by a system of differential equations, which describes the interaction between drug-sensitive and drug-resistant cancer cells both during drug therapy and in the absence of it. This model also contains a control function responsible for the transition from the stage of such therapy to the stage of its absence and vice versa. To find the optimal moments of switching between these stages, the problem of minimizing the cancer cells load both during the entire period of melanoma treatment and at its final moment is stated. Such a minimization problem has a nonconvex control set, which can lead to the absence of an optimal solution to the stated minimization problem in the classes of admissible modes traditional for applications. To avoid this problem, the control set is imposed to be convex. As a result, a relaxed minimization problem arises, in which the optimal solution exists. An analytical study of this minimization problem is carried out using the Pontryagin maximum principle. The corresponding optimal solution is found in the form of synthesis and may contain a singular arc. It shows that there are values of the parameters of the bilinear control model, its initial conditions, and the time interval for which the original minimization problem does not have an optimal solution, because it has a sliding mode. Then for such values it is possible to find an approximate optimal solution to the original minimization problem in the class of piecewise constant controls with a predetermined number of switchings. This research presents the results of the analysis of the connection between such an approximate solution of the original minimization problem and the optimal solution of the relaxed minimization problem based on numerical calculations performed in the Maple environment for the specific values of the parameters of the bilinear control model, its initial conditions, and the time interval.

Keywords:

melanoma; bilinear control system; relaxed minimization problem; optimal control; Pontryagin maximum principle; singular arc; sliding mode MSC:

49J15; 49J30; 49N90; 92C50; 93C95

1. Introduction

Melanoma is one of the most aggressive types of cancer. The increase in the number of patients with melanoma has been growing over the past 30 years, regardless of their geography, wealth, or age. With all localizations of melanoma (which can also grow in the retina, intestines, and throat), after the first detection by a doctor, about 30% die within 5 years. Mortality in the first year of treatment reaches 15% of those who seek help [1,2].

Melanoma is a malignant disease of the upper layer of the skin, the epidermis. The constant renewal of epidermal cells occurs due to keratinocytes formed in the lower layer of the epidermis. Along with keratinocytes, melanocytes are also formed in the lower layer of the epidermis, giving color to the skin. Melanocytes can accumulate in the epidermis in the form of small spots. In some melanocytes, under the influence of internal and external factors, signal transduction mechanisms that affect cell apoptosis can be disrupted [2]. This is the main reason for the unrestricted growth of melanoma. As a result, the process of endless division of melanocytes can begin and a small spot of melanocytes can turn into a malignant tumor of constantly dividing cells, spreading superficially in the form of a flat mass [2]. The linear growth of a tumor can reach 0.25 mm per day and, depending on the organ on which it grows, it can reach a length of more than 10 cm. According to various estimates, the specific growth rate of a population of dividing cells ranges from 0.003 to 0.100 per day [2,3,4].

Modern methods of treating patients with melanoma include the use of surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, immune and targeted methods, or their combination [5]. However, the practical results of treatment remain unsatisfactory due to the high recurrence rate and short survival after treatment. One reason that the diagnosis of melanoma is not associated with a favorable prognosis is that the expected outcomes of treatment often remain unsatisfactory due to late treatment seeking. About 25% of patients seek help in stage IV disease with multiple metastases.

There are other reasons for a negative prognosis for melanoma patients that relate to the methods of treatment for melanoma. Usually, chemotherapy is the first choice after surgery [2,6]. However, chemotherapy is also not always effective, as tumor cells gradually become resistant to drugs during their exposure [7,8,9,10]. At this stage of cancer, two types of cancer cells are distinguished—susceptible, which respond to treatment and die, and resistant cancer cells, which begin to quickly divide [11]. For this class of cancer cells, chemotherapy often plays the role of food—resistant cells begin to divide even faster with chemotherapy and do not die at all. Resistant cells quickly begin to dominate in the tumor [12]. Several studies have shown that phenotypic switching between susceptible and resistant types provides another pathway for acquired resistance during therapy. Once resistant cells begin to predominate, the treatment is ineffective because it no longer prevents tumor growth.

There is a dilemma—how to conduct the right treatment? If a patient rejects chemotherapy, then all cancer cells will continue to grow, and the patient will die. If chemotherapy is given, resistant cells start increasing in size, and the patient also dies.

The goal of successful cancer therapy is to control tumor growth in each patient by allowing a significant number of susceptible cells to survive, either by imposing treatment interruptions or by modulating the dose of the active drug. There is a hope that mathematical models of the dynamics and treatment of melanoma will help to choose the optimal treatment protocol. Mathematical models of cancer are commonly developed on the basis of ordinary differential equations or partial differential equations [9,10,13,14,15,16,17]. There are several articles that use optimal control theory to control drug dosage in various models of melanoma [18,19,20]. The most popular model is natural competition between susceptible and resistant cancer cells [7]. The developed probabilistic approach for estimating the time to reach a certain tumor size can be used in adaptive therapy [12] to determine the optimal time for treatment switching points, taking into account the specific characteristics of the patient.

In general, mathematical models of various cancers (not just melanoma) are presented in books [21,22,23,24] and related references within them. Finding the most effective protocols for the treatment of these cancers based on such models and using the optimal control theory is also given in books [25,26] and the relevant references within them.

The problems of optimal control of chemotherapy and drug resistance of cancer cells are presented in [25]. The same authors also discuss the uncertainty of model parameters and the effectiveness of some anticancer drugs. In all the above books and references in them, the control is the rate of drug delivery, so the search for optimal cancer treatments is reduced to finding the optimal concentrations of the anti-cancer drug as a function of time.

In clinical practices, chemotherapy involves the alternate administration of one or several drugs. The course of treatment can last from several days to several weeks and even months and be repeated several times during the total treatment time [7,8]. It has been noticed that if, for example, the drug is administered for 3–7 days, and then the patient rests for 3–7 days, and then the entire protocol is repeated, then such a plan does not lead to recovery or a sharp improvement in the patient’s condition. In our study, we consider differences in the responses of drug-sensitive and drug-resistant cancer cells to chemotherapy. Since drug-resistant cancer cells perceive the drug as food during chemotherapy, it is believed that there may be such a treatment schedule in which the intervals of taking the medication and the intervals of the break are not equal but can be optimized.

The novelty of our study lies in the fact that instead of searching for the optimal concentration of a chemotherapeutic drug, we use the optimal control theory and determine the optimal treatment protocol based on the frequent alternation of “drug in” and “no drug” intervals, minimizing the overall oncological burden on the patient. The corresponding optimal control problem is stated and solved in this paper.

For such an optimal control problem, the interaction between drug-sensitive and drug-resistant cancer cells during the “drug in” and “no drug” periods is described by systems of linear differential equations. When two models are combined, a bilinear control system arises with a scalar control that takes only two values—0 and 1 (the value 0 corresponds to the “no drug” intake, and the value 1 implies the “drug in” period.) Adding the objective function to be minimized, which has the meaning of the weighted sum of the cancer load over the total treatment period of the disease and the cancer load at the end of this time period, we obtain the desired optimal control problem. Due to the features of the control set, the minimization problem under consideration may not have an optimal solution in classes of admissible modes traditional for applications (which we will see later). The way out in such a situation is to consider the so-called relaxed minimization problem. Due to the fact that we are considering a control bilinear system, using the Pontryagin maximum principle allows us to analytically obtain a complete solution to such a minimization problem. Analysis of this solution shows that for some initial conditions and given total treatment period of the disease, the so-called singular control is possible, when the optimal control takes some intermediate value from the interval . This means that the original minimization problem does not have an optimal solution. However, the optimal solution can be approximated arbitrarily accurately on the interval where the singular arc is realized by strongly oscillating piecewise constant controls taking values 0 and 1. In turn, this fact means that in the original minimization problem, the set, where the control system is located under the action of a singular control in the relaxed minimization problem, acts as a sliding mode. All this is analytically demonstrated in this paper. It is understood that piecewise constant controls with a very large number of switchings would be difficult to apply to the treatment protocols. Therefore, within the framework of the considered control system, at the moment of hitting the set, where the sliding mode is implemented, we propose to replace the optimal control portion with strong oscillation of values between 0 and 1 by the portion of this control with a fixed (predetermined) number of switchings between the same values. Such switchings and their lengths are found numerically. In the paper, we discuss some aspects of such a replacement. Additionally, we present the results of numerical calculations for the values of parameters of the bilinear control system, its initial conditions and the total treatment period of the disease, which are taken from sources where similar systems for the “drug in” and “no drug” periods of cancer treatment diseases are considered. Finally, we discuss our results in detail.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 and Section 3 detail a bilinear control system that describes the behavior of drug-susceptible and drug-resistant cancer cells over a given period of time in the treatment of melanoma. For this system, Section 3 states the problem of minimizing the cancer load, both during the entire time period of the treatment of the disease, and at its final moment. After that, the section discusses the possibility of the absence of an optimal solution in this minimization problem, as well as a way to overcome this difficulty. As a result, a relaxed minimization problem arises. A detailed analysis of the new optimal control problem based on the Pontryagin maximum principle (its various aspects) is presented in Section 4, Section 5, Section 6 and Section 7. Section 8 gives a complete description of the optimal solution in the relaxed minimization problem. In turn, Section 9 discusses the optimal solution of the already original minimization problem. The results of numerical calculations and their detailed analysis are presented in Section 10. Finally, Section 11 contains our conclusions.

2. Mathematical Model of Melanoma Treatment

Let us consider a setting where cells are assumed to mix well and dynamics are deterministic, which can be described by ordinary differential equations. The preliminary modeling uses systems of ordinary differential equations to describe the evolutionary co-dynamics of susceptible and resistant melanoma cells:

In equations of systems (1) and (2), susceptible cells divide at rates and in the absence and in the presence of treatment, respectively. They produce resistant mutants with probability p per cell division. In treatment, susceptible cells die at a higher rate compared to their death rate in the absence of treatment; their net growth rate in treatment is negative. Resistant cells grow faster in the presence of treatment (), and they die at rates and in the two regimes.

Let us denote the net growth rate of each cell type with the superscript ‘on’ for the treatment phase, or the superscript ‘off’ for the off-treatment phase. Given that in practical applications p is very small, we can neglect it and write:

We will assume the following inequalities:

Indeed, in [27,28] the value is used, and in [29] this value is equal .

3. Statement of the Minimization Problem and Its Discussion

Let us have a process of melanoma treatment, which consists in alternating between the period of treatment:

and the period of no treatment:

where , and , are given constants that satisfy the inequalities:

System (4) has a unique equilibrium in the region . Writing this system in a vector form:

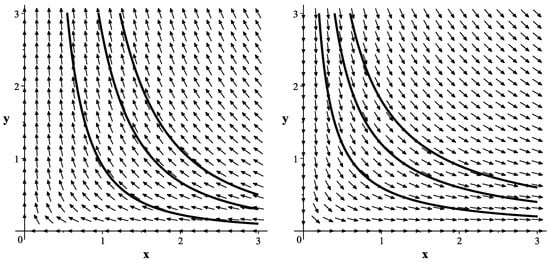

we see that its matrix has two real eigenvalues and corresponding to the respective eigenvectors and . Therefore, the equilibrium is a saddle. Trajectories of system (4) are schematically shown in Figure 1 (left).

System (5) also has a single equilibrium in the same region. Representing this system in a vector form again:

we conclude that its matrix has two real eigenvalues and corresponding to the same eigenvectors. Then, the equilibrium is also a saddle. Trajectories of system (5) are schematically presented in Figure 1 (right).

Let us introduce a value and use it to connect the constants , and , by the following formulas:

It is easy to see that there is no treatment for and in equalities (7) we have constants , . For , treatment, on the contrary, is carried out, and from equalities (7) we obtain constants , . To simplify the subsequent arguments in (7), we define the following constants:

Due to the inequalities (6), it can be seen that

Using Formula (7) and involving in them the constants a, b, c and d satisfying inequalities (8) and (9), we combine systems (4) and (5) into the following bilinear control system:

Here , are initial conditions, and is a control function subject to the inclusion:

where V is a control set.

We will consider system (10) on a given time interval , which is the total period of treatment of the disease. By the set of admissible controls we mean all possible Lebesgue measurable functions that satisfy the inclusion (11) for almost all .

The validity of the following lemma is easily established.

Lemma 1.

For any admissible control , the components of the solution of system (10) are absolutely continuous functions that are defined on the interval and are subject to inequalities:

Proof of Lemma 1.

The equations of the system (10) are linear differential equations, and therefore [30] the solution of this system is defined on the entire interval . Integrating each equation of the system (10) with the corresponding initial condition, we find the formulas:

from which the positivity of the solution components and on the entire interval immediately follows (the left constraints in (12)). Using in Formula (13) the necessary inequalities from (8) and inclusion (11), we obtain the required right constraints in (12). The statement is proven. □

Remark 1.

Lemma 1 implies the positive invariance of the control system (10) in the region

Let us establish other properties of system (10). To do this, we rewrite it in vector form:

For and we have the corresponding vectors:

Let us study the linear dependence or independence of these vectors in the region . To do this, we calculate the determinant , composed of vectors and . As a result, we have the formula:

If , then the vectors and are linearly independent in the region . If , then they are linearly dependent in and system (10) will be rewritten in the form:

where . System (14) is easily integrated. As a result, we obtain the formula:

This means that the dynamics of system (10) is determined by the first differential equation in (14) and carried out on the curve (15). Control system (10) degenerates. Therefore, we will not consider such a case further.

Thus, in what follows, we assume that the following inequality holds:

For control system (10) on the set of admissible controls , we introduce an objective function:

where is a positive weight coefficient. The medical meaning of the objective function (17) is the cancer load both during the total treatment period and in its final moment T. We consider the problem of minimizing the objective function (17):

The control set V is not convex. In turn, this leads to non-convexity of the set of admissible velocities:

for each point . This fact may lead to the absence of an optimal solution in the minimization problem (18). We will verify its correctness later. To overcome this problem, we will further apply the traditional approach, which consists in considering a relaxed minimization problem [31]). Such a problem is constructed as follows. First, the convex hull of the set of admissible velocities is taken. Due to the linearity of the components and in variables x, y and v, this action is equivalent to taking the convex hull of the control set V. As a result, the two-point set V turns into the segment . Then, instead of the set of admissible controls , we consider the set of admissible controls . It consists of all possible Lebesgue measurable functions that satisfy the inclusion for almost all . Here, U is a new control set.

Remark 2.

Lemma 1 remains valid for the control system (10), which is now considered on the set of admissible controls .

Then, for the original minimization problem (18), the relaxed minimization problem consists in minimizing the objective function (17) for the control system (10) on the set of admissible controls :

System (10) is linear in control , which takes values in the convex set U, and constraints (12) are valid for it. Therefore, due to Theorem 4 from Chapter 4 [32]), in the relaxed minimization problem (19) there exists an optimal solution consisting of an optimal control and the corresponding optimal solution for system (10).

4. Pontryagin Maximum Principle for the Relaxed Minimization Problem

To analyze the optimal solution of the relaxed minimization problem (19), we apply the Pontryagin maximum principle [33]). First, we write down the corresponding Hamiltonian:

where and are adjoint variables. Then we calculate the required partial derivatives of this Hamiltonian:

Then, according to the Pontryagin maximum principle, for the optimal control and the corresponding optimal solution for system (10) there exists an adjoint function , such that

- it is an absolutely continuous solution of the adjoint system:

- control maximizes the Hamiltonian in the variable for almost all , and therefore it satisfies the following relationship:

where a function

is the switching function. Its behavior determines the type of control in accordance with the Formula (21).

Let us analyze relationships (20)–(22). Their analysis will show what the function can be, and hence the optimal control corresponding to it. Since the switching function is an absolutely continuous function, it can vanish either in separate points or on intervals. Thus, the control can have a bang-bang form and switch between the values 0 and 1. This will happen if, when passing through the value of , in which the function decreases to zero, the sign of this function changes. This value is the switching of the optimal control . In addition to sections of bang-bang form, control may also contain singular sections in which a singular regimen takes place [26,34]. This happens when the corresponding switching function vanishes identically on some subintervals of the interval . The following arguments are devoted to a detailed study of the possible existence of a singular regimen for the optimal control .

5. Useful Transformations and Formulas

Let us first simplify the adjoint system (20) and the switching function given by Formula (22). To do this, we introduce new adjoint variables of the form:

Then, using the equations of systems (10) and (20), as well as the initial conditions from (20), we obtain a new adjoint system:

At the same time, due to Formula (23), the switching function is rewritten as

Now using the equations of systems (10) and (24), as well as Formula (25), we find expressions for the first derivative and the second derivative of the switching function . As a result, we have formulas:

Let us determine the sign of the second derivative of the function on the intervals where the control takes the value 0 or 1. The following lemma is true.

Lemma 2.

If on the interval the optimal control has the value 0 (which means that ), then . If on this interval the control takes the value 1 (this implies that ), then .

Proof of Lemma 2.

The proof immediately follows from Formula (27), inequalities (8) and (9), and Lemma 1. Indeed, for we have:

and for we obtain:

The statement is proven. □

The following lemma also holds.

Lemma 3.

There is no situation when moments and , are defined on the interval , which are zeros of the switching function , that on the interval this function takes either positive or negative values.

Proof of Lemma 3.

For the sake of definiteness, we consider the situation when the interval on which the function is positive is defined and the equalities and hold. Then, by the Weierstrass theorem, there is a value at which this function reaches its maximum. This means that relationships and are valid, and the second of them contradicts Lemma 2. Therefore, the considered situation does not hold. The statement is proven. □

Lemma 3 can be weakened. Namely, the following lemma is true.

Lemma 4.

There is no situation when moments and , are defined on the interval , where the moment is the zero of the switching function , but the moment is not. At the same time, the value of the function in this moment, as well as on the entire interval , can be either positive or negative and the inequality holds.

Proof of Lemma 4.

As in the proof of Lemma 3, for the sake of definiteness, we consider the situation when the interval on which the function is positive is defined and the equality and the inequalities , hold. Let us define on the interval the auxiliary function . Then, the following relationships:

are valid for it. The last two relationships imply that there is an interval adjacent to on which . Since , the interval is defined on which and . Using Lemma 3 for the function we see that the considered situation does not hold as well. The statement is proven. □

The Formulas (26) and (27) imply that the first derivative and the second derivative of the switching function depend on the components and of the optimal solution . Therefore, by integrating the equations of the system (24) with the appropriate initial conditions and substituting the resulting expressions for the functions and into the Formula (25), we find the relationship for the function also through the components and :

6. Singular Regimen

Let there be an interval on which the switching function is identically equal to zero. Then the first derivative and the second derivative of this function vanish everywhere on this interval:

It defines a special ray

on which the optimal trajectory is located when the control has a singular regimen. Substituting equality (30) into the second formula in (29) leads to the relationship:

from which, by Lemma 1, we find the formula for the optimal control on a singular regimen:

It is easy to verify that . Additionally, from (31) we conclude that the relationship:

is valid for all . It implies that the necessary condition for the optimality of the singular regimen (the Kelly condition) is satisfied [34]), and, moreover, in a strengthened form. This means that the optimal control can have a singular regimen, which is concatenated with non-singular (bang-bang) sections on which this control takes values [26]).

7. Behavior of the Optimal Trajectory

Let us study the behavior of the optimal trajectory . It is easy to see that

- (a)

- for , the equations of system (10) are written in the form:It follows that with increasing time t, the coordinate x increases, and the coordinate y, on the contrary, decreases. Schematically, the behavior of the optimal trajectory is shown in Figure 1 (right);

- (b)

- for , the equations of system (10) are reduced to the form:This implies that with increasing time t, the coordinate x decreases, and the coordinate y, on the contrary, increases. The behavior of the optimal trajectory is schematically presented in Figure 1 (left);

- (c)

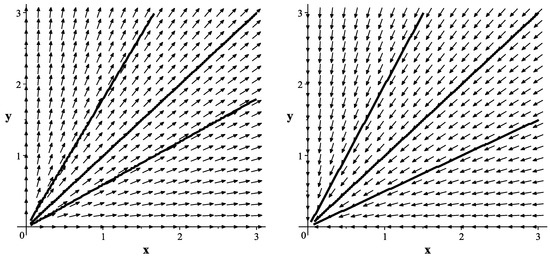

- for , the equations of system (10) are written as followsThe expression can take both positive and negative values. Therefore, the coordinates x and y either increase or decrease simultaneously with increasing time t. Due to the inequality (16), system (34) has a unique equilibrium in the region . Giving this system in a vector form:it is easy to see that its matrix has two coinciding real eigenvaluesTherefore, the equilibrium is a dicritical node. For it is stable, but for it is unstable. Schematically, trajectories of the system (34) are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Phase portrait of system (34) when (left) and (right).

Figure 2. Phase portrait of system (34) when (left) and (right).

8. Solving the Relaxed Minimization Problem

Let us now find the possible types of optimal control .

From the initial conditions of the adjoint system (24) and Formula (25) we obtain equality

and from the Formula (26) the equality follows

Then the following cases take place.

Case A. Let , or (point is located above the special ray ). Then, by (35) and (36), and . Therefore, there is an interval adjacent to T, on which . It follows from Lemma 4 that the switching function takes negative values for all . Due to Formula (21), this means that the optimal control is a constant function that has the value 0 on the entire interval . In addition, from Lemma 2 it follows that the derivative is a decreasing function up to the positive value of , and therefore for all . Hence, on the entire interval . Therefore, the optimal trajectory is above the special ray for all .

Case B. Let , or (point is below the special ray ). Then, due to (35) and (36), and . Therefore, an interval is defined adjacent to T, on which . Lemma 4 implies that the switching function has positive values for all . By the Formula (21), this means that the optimal control is a constant function that takes the value 1 on the entire interval . Moreover, Lemma 2 implies that the derivative is an increasing function up to the negative value of , and therefore for all . Hence, on the entire interval . This means that the optimal trajectory lies below the special ray for all .

Case C. Let , or (point is located on the special ray ). Then, in according with (35) and (36), and . Subsequent arguments depend on the value . The following three subcases are possible.

Subcase C1. If , then there exists an interval adjacent to T, on which . Lemma 3 implies that the switching function is positive for all . Due to the Formula (21), this means that the optimal control is a constant function that has the value 1 on the entire interval . Moreover, Lemma 2 implies that the derivative is an increasing function up to zero value of , and therefore for all . Hence, for . This means that the optimal trajectory is below the special ray for these values of t.

Subcase C2. If , then an interval is defined adjacent to T, on which . It follows from Lemma 3 that the switching function is negative for all . According to the Formula (21), this means that the optimal control is a constant function that takes the value 0 on the entire interval . In addition, Lemma 2 implies that the derivative is a decreasing function up to zero value of , and therefore for all . Hence, for . This means that the optimal trajectory is above the special ray for these values of t.

Subcase C3. If , then there is an interval adjacent to T, on which the optimal control has a singular regimen. Everywhere on this interval and equalities (29) hold. It follows from the first equality in (29) and Formula (26) that the optimal trajectory moves along a special ray , being on the interval . In this case, the interval may coincide with the interval . Then the initial point is located on the ray , and on the entire interval the optimal control is a constant function that takes the value . In addition, the interval may be contained within the interval , when . In this case, there are equalities and . The optimal trajectory described either in Subcase C1 or in Subcase C2 will fall on the special ray at the moment . Thus, the trajectory moves on the interval either from the region above the ray with control , or from the region below this ray with control , to the ray , and ends up on it at the moment . Further, on the interval , the trajectory moves along the special ray with control . Therefore, the following formulas are valid for the optimal control :

Let us find formulas for the moment , when the optimal trajectory is on the special ray , depending on whether the initial point is located above or below this ray.

Firstly, we consider the situation, when point is above the ray :

and the trajectory moves under the action of the optimal control towards this ray. Let us integrate the equations of the system (10) with this control. As a result, we obtain the formulas:

Since we are looking for the moment when the trajectory is on the special ray , we will substitute the Formula (39) into the definition (30) of this ray. We have the expression:

Let us consider the function:

We show that it has the unique value , such that the equality holds. Indeed, inequality (38) implies , and Formula (40) with the inequalities (8) leads us to the relationship:

In addition, turning again to inequalities (8), it is easy to verify by calculating the derivative of the function :

that this function decreases for all . Let us find the formula for the moment from the expression:

As a result, we have the relationship:

It also follows from the arguments above that the inequality is satisfied for all . In addition, due to Formula (30) taken on the interval , the expression (28) is rewritten in the form:

This relationship immediately implies that for all .

Secondly, we study the situation, when point is below the ray :

and the trajectory moves under the action of the optimal control towards this ray. Let us integrate the equations of the system (10) with this control. As a result, we obtain the formulas:

Since we are looking for the moment when the trajectory is on the special ray , we will substitute the Formula (44) into the definition (30) of this ray. We have the expression:

Let us consider the function:

We show that it has the unique value , such that the equality holds. Indeed, inequality (43) implies , and Formula (45) with the inequalities (8) and (9) leads us to the relationship:

Moreover, turning again to inequalities (8) and (9), it is easy to verify by calculating the derivative of the function :

that this function increases for all . Let us find the formula for the moment from the expression:

As a result, we have the relationship:

These arguments lead to the inequality that is true for all . Moreover, by virtue of the Formula (30) taking place on the interval , the expression (28) is transformed into the Formula (42), from which it immediately follows that for all .

Finally, we have the final conclusion related to the optimal solution of the relaxed minimization problem (19).

Theorem 1.

The following statements are valid.

- (a)

- Let the initial point be located above the special ray Π. Then the optimal trajectory with the control moves towards the ray Π. If at the final moment T it turns out to be either above it or on it, then the optimal control has the value 0 on the entire interval . If the trajectory reaches the ray Π at the moment , then the control is switched and further on the interval this trajectory moves along the ray with control .

- (b)

- Let the initial point be below the special ray Π. Then the optimal trajectory with the control also moves towards the ray Π. If at the final moment T it is either below it or on it, then the optimal control has the value 1 on the entire interval . If the trajectory reaches the ray Π at the moment , then the control is switched and further on the interval this trajectory moves along the ray with control .

- (c)

- Let the initial point lie on a special ray Π. Then, on the entire interval , the optimal trajectory moves along the ray Π with the control .

Remark 3.

Previously, we justified the existence of the optimal solution in the relaxed minimization problem (19). To analyze this solution, we applied the Pontryagin maximum principle, which is only a necessary condition for optimality. As a result, we obtained the two-point boundary value problem of the maximum principle consisting of systems (10), (24) and Formulas (21) and (25), which we further studied in detail and presented the corresponding results in Theorem 1. Since the solution to such a boundary value problem turned out to be unique, it means that it is the optimal solution to the relaxed minimization problem (19). Thus, Theorem 1 gives the complete description of the optimal solution to the problem (19).

Below there are figures demonstrating the possible behaviors of the optimal trajectory and the corresponding optimal control .

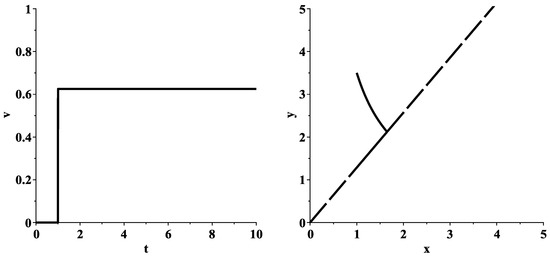

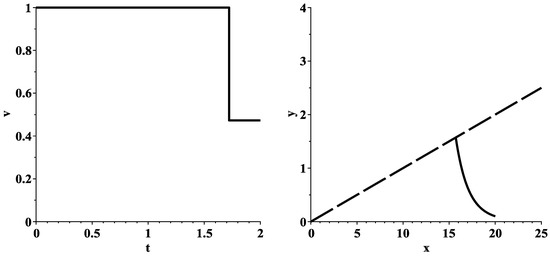

Figure 3 considers the situation when

Figure 3.

Graph of the optimal control (left), behavior of the corresponding optimal trajectory (right). In the left picture, the special ray is shown as a longdash line. The initial point is located above this ray.

It is easy to see that the inequalities (8), (9) and (38), as well as the inequality , are satisfied for the specified values of the parameters and initial conditions. In addition, according to Formula (41), the value . Therefore, the optimal control is determined by the left formula in (37), where . The behavior of the corresponding optimal trajectory is given in Figure 3 (right). The objective function (17) takes the smallest value .

Figure 4 demonstrates the situation when

Figure 4.

Graph of the optimal control (left), behavior of the corresponding optimal trajectory (right). In the left picture, the special ray is represented by a longdash line. The initial point is located below this ray.

It can be seen that the inequalities (8), (9) and (43), as well as the inequality , take place for the specified values of the parameters and initial conditions. Moreover, due to Formula (46), the value . Therefore, the optimal control is defined by the right formula in (37), where the value is the same. The behavior of the corresponding optimal trajectory is presented in Figure 4 (right). The objective function (17) reaches the smallest value .

9. Solving the Original Minimization Problem

Theorem 1 shows that the optimal solution of the relaxed minimization problem (19) can be one of the following three types and will be related to the optimal solution of the original minimization problem (18) as follows.

Case A. The initial point is located above or below the special ray (), and the time of movement along the trajectory from it to this ray . Such a movement is carried out with the help of the constant control , which takes the value 0 or 1. Since the values are admissible in the original minimization problem (18), the optimal solution of the relaxed minimization problem (19) simultaneously serves as the optimal solution of the original minimization problem (18).

Case B. The initial point is above or below the special ray (), and the time of movement along the trajectory from it to this ray . Such a movement is carried out due to the control , which takes the value 0 or 1 on the interval . In this case, as already noted, the values are admissible in the original minimization problem (18). Then, the control is switched, and then, on the interval , the movement along the trajectory occurs along a special ray with the help of the control that is no longer admissible in the original minimization problem (18). Thus, the original minimization problem (18) does not have the optimal solution.

Case C. The initial point lies on a special ray (). On the entire interval , the trajectory moves along the special ray under the action of the control , which, as already noted, is not admissible in the original minimization problem (18). Hence, the original minimization problem (18) again has no optimal solution.

Let us now show that in Cases B and C in the original minimization problem (18) the special ray acts as a sliding mode [35,36]). This means that there is such a family of strongly oscillating piecewise constant controls that take values such that the corresponding family of trajectories uniformly converges to (or “is pressed against”) this ray as . Here, is a scalar parameter. Moreover, the family of values of the objective function (17) corresponding to such a family of trajectories, as , will tend to the value that is its smallest value in the corresponding relaxed minimization problem (19).

For definiteness, we will study the situation in Case B, when the initial point is located above the special ray () and . Situations when the initial point is below the ray () at or is located on it () are considered similarly.

So, Theorem 1 shows that on the time interval the trajectory , due to the control , moves to the special ray , on which it turns out at . Hence, we have the point such that, by virtue of (30), the following equalities hold:

Now let us assume that on the interval the control that we are constructing takes the value 0, which ensures that the trajectory coincides with the trajectory corresponding to the control .

In what follows, we assume that the parameter is arbitrarily small and consider the tube around the trajectory :

It is easy to see that the tube has lower and upper boundaries, which are located on the corresponding straight lines:

Now, when , we take the value 0 for the control and then integrate the system (32) with the initial conditions:

As a result, we obtain the formulas:

that define the curve coming out of the point on the ray . Let us show that this curve intersects the lower boundary of the tube . To do this, when , we consider the function:

that is obtained as the substitution of the Formula (49) into the equation of the lower boundary of the tube in (48). It is easy to see that, due to the definition of the point in (47) and inequalities (8), the following relationships hold:

Moreover, by virtue of Lemma 1 and inequalities (8), the derivative of the function :

which implies that this function is decreasing. Therefore, there is the value for which , either given the definition of the function :

or due to the Formula (49):

This means that at time the trajectory intersects the lower boundary of the tube at the point , where

and everywhere on the interval such a trajectory is inside this tube.

Now, when , we choose the value 1 for the control (we make a switch for this control) and then integrate system (33) with the initial conditions (51). As a consequence of this, we obtain the formulas:

that define a curve starting from the point on the lower boundary of the tube . Let us make sure that this curve intersects the upper boundary of the tube . To do this, when , we introduce the function:

that is the result of substituting Formula (52) into the equation for the upper boundary of the tube in (48). It can be seen that, by virtue of the definition of the point in (50), (51) and inequalities (8), (9), the following relationships are true:

Moreover, due to Lemma 1 and inequalities (8), (9), the derivative of the function :

which means that this function is increasing. Therefore, the value is defined for which , either due to the definition of the function :

or due to the Formula (52):

This implies that at time the trajectory intersects the upper boundary of the tube at the point , where

and everywhere on the interval such a trajectory lies inside this tube.

Now let us take the last step of this kind. Namely, when , we again take the value 0 for the control (we perform switching for this control) and then we integrate system (32) with the initial conditions (54). As a result, we find the formulas:

that define the curve starting from the point on the upper boundary of the tube . Let us demonstrate that this curve intersects the lower boundary of the tube . To do this, when , we will study the function:

that is formed as a result of substituting Formula (55) into the equation of the lower boundary of the tube in (48). We see that due to the definition of the point in (53), (54) and inequalities (8), the following relationships are valid:

In addition, Lemma 1 and inequalities (8) show that the derivative of the function :

which leads to the conclusion that this function is decreasing. This means that there is the value for which equality is satisfied, either due to the definition of the function :

or due to the formulas (55):

Therefore, at time the trajectory intersects the lower boundary of the tube at the point , where

and everywhere on the interval such a trajectory is located inside this tube.

This process can be continued and using induction (the base of the induction has already been described above) we can obtain the trajectory whose points , are on the lower boundary of the tube , and whose points , lie on the upper boundary of this tube. Moreover, for all , such a trajectory is located in the tube . Here the sequence of moments , when the trajectory is on the boundaries of the tube is increasing:

The corresponding control has the form:

It remains for us to show that for the given value of the parameter there is a natural number such that . This means that the control we have constructed is defined on the entire interval . In turn, for this it suffices to establish the existence of such a value that for all .

Indeed, let us first consider the moments of switching and , and the function corresponding to them (in previous arguments, such switchings were and ). We write the Lagrange formula for this function:

where the derivative is written as

Let us estimate the modulus of this derivative from above. As a result, due to inequalities (8), (9) and (12), we obtain the relationship:

where

Then, passing in the expression (56) to the modulo estimate and using the equalities obtained earlier:

we have the inequality:

or

Now consider in a similar way the moments of switching and , , and the function corresponding to them (in previous arguments, such switchings were and ). Let us write again the Lagrange formula for this function:

where the derivative resembles

Let us estimate the modulus of this derivative from above. As a consequence of this, by virtue of inequalities (8) and (12), we find the relationship:

where

Then, passing in expression (58) to the modulo estimate and using the equalities established earlier:

we obtain an inequality:

or

Let us introduce the constant . Then, combining the inequalities (57) and (59), we arrive at the required inequality:

Using the inequality (60), we define the desired constraints for the value as

or

where is the integer part of the positive number .

Finally, let us estimate the difference between the values of the objective function (17) taken on the controls and . We have the equality:

Passing in this expression to the modulo estimate and using the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality, as well as the fact that the trajectory lies in the tube on the interval , we achieve the inequality:

By now specifying an arbitrarily small number and requiring that the following inequality hold

we complete the justification of the result discussed at the beginning of this section. Namely, by tending the value to zero, due to inequalities (61) and (62), we tend the parameter also to zero and simultaneously increase the number . Then the trajectory “is pressed against” the special ray , and the value of the objective function is arbitrarily close to the value . Thus, we come to the conclusion that the special ray in the considered situation is a sliding mode.

10. Results of Numerical Calculations and Their Discussion

In this section, we will discuss how the results of the previous section can be used to find effective treatment protocols for melanoma when a sliding mode occurs. It is clear that it makes no sense to use a very large number of switchings in treatment protocols. Therefore, we will consider a situation with a given small number of switchings , which will act as variables and whose values will be determined as a result of solving some minimization problem. Let us describe it.

First, on the interval , we define the piecewise constant control that takes values and has n switchings as follows. If , then it resembles

If , then it is determined by the formula:

Then we substitute this control into system (10) and integrate it. The resulting solution is substituted into the objective function (17). As a consequence of this, we obtain the function of a finite number of variables , which we will then minimize on the set:

The results of the corresponding numerical calculations in the Maple environment are presented below.

Remark 4.

Similar finite-dimensional minimization problems were previously considered in the study of control models of the spread of Ebola epidemics and HIV treatment [37,38,39,40,41,42].

Remark 5.

We note that system (10) is linear in phase variables. Additionally, the right-hand sides of its equations depend linearly on the parameters a, b, c and d. Therefore, due to the scaling of this system in terms of phase variables and time, we can consider phase variables, parameters a, b, c, d and time t in ranges convenient for numerical calculations.

Now we consider the following values of the parameters a, b, c, d and initial conditions , of system (10), as well as the final moment T of the interval :

These values of the quantities a, b, c and d satisfy the inequality (16) and were found by Formula (8), based on the following values of the parameters of systems (4) and (5):

It is easy to see that they satisfy restrictions (6).

In turn, to determine these quantities according to Formula (3), the following values were used:

which were taken based on similar values from [27].

After that, in system (10), due to Remark 5, the scale of parameters a, b, c, d, initial conditions , , and final moment T was changed. Namely, the time scale was changed first as

This made it possible to change the scale for the parameters a, b, c and d:

after which, the scales of the initial conditions and were also changed as

which is equivalent to changing the scales of the variables x and y. As a result of these actions, the values and from the Formula (12) took on values:

which led to the need to once again correct the initial conditions and to the values:

and the values and have become the values of the same order.

As a result, we have the following values of the quantities a, b, c, d, , and T:

which will be used in numerical calculations. Moreover, we will put the weight coefficient .

Figure 5 shows the graph of the optimal control and the behavior of the corresponding optimal trajectory in the relaxed minimization problem (19) for the values of the parameters, initial conditions and final moment T presented in (64). It is easy to see that the inequalities (8), (9) and (43), as well as the inequality , are satisfied. In addition, according to Formula (46), the value . Therefore, the optimal control is determined by the right formula in (37), where . The behavior of the corresponding optimal trajectory is given in Figure 5 (right). The objective function (17) takes the smallest value .

Figure 5.

Graph of the optimal control (left), behavior of the corresponding optimal trajectory (right) in the relaxed minimization problem (19). In the left picture, the special ray is represented by a longdash line. The initial point is located below this ray.

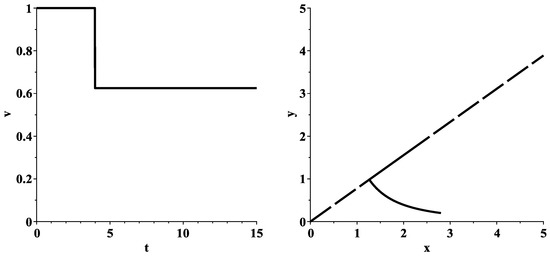

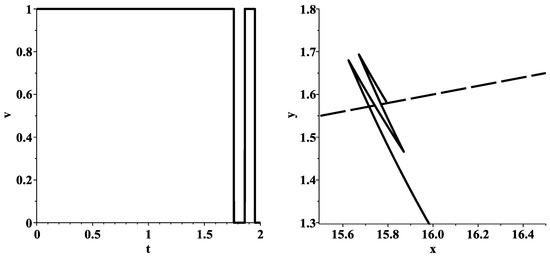

Figure 6 presents the graph of the optimal control and the behavior of the corresponding optimal trajectory in the problem of minimizing the function on the set , which for is given as

Figure 6.

Graph of the optimal control (left), behavior of the corresponding optimal trajectory (right) in the problem of minimizing the function . In the left picture, the special ray is represented by a longdash line. The initial point is located below this ray.

The switchings , , of the optimal control , which is determined by formula (63), take the following values:

The function has the smallest value .

As noted at the beginning of this section, the minimization problem for the function is some approximation of the original minimization problem (18). It follows from the numerical calculations that this approximation is quite acceptable. Indeed, the distinction between the smallest value of the objective function (17) in the relaxed minimization problem (19) and the smallest value of the function occurs only in the fourth decimal place of the fractional part of the difference .

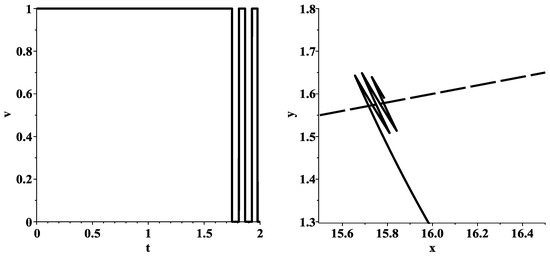

Figure 7 gives the graph of the optimal control and the behavior of the corresponding optimal trajectory in the problem of minimizing the function on the set , which for is defined as follows

Figure 7.

Graph of the optimal control (left), behavior of the corresponding optimal trajectory (right) in the problem of minimizing the function . In the left picture, the special ray is represented by a longdash line. The initial point is located below this ray.

The switchings , , , , of the optimal control , which is determined by Formula (63), take the following values:

The function has the smallest value .

It is easy to see that an increase in the number of switchings from three to five leads to an improvement in the result. Indeed, the value of the function is less than the value of the function , but greater than the value of the objective function .

It is also clear why the numerical calculations for and gave such good results. This is due to the fact that most of the time (interval with length ) we move along the trajectory that is simultaneously optimal in the relaxed minimization problem (19), and a smaller part of the time (interval with length ) is not.

We also use the full finite-dimensional optimization in the studied example. To do this, we first consider the situation . Let us introduce two piecewise constant controls and as follows

The difference between the controls , and the control is that the switchings , and , of these controls are on the entire interval , and not on its part .

Now we substitute these controls into system (10) and then integrate it. The resulting solution is substituted into the objective function (17). As a result, we obtain the functions and of a finite number of the respective variables , and , , which we then numerically minimize in a similar way on the corresponding sets:

As a result of numerical minimization of the function on the set , we have the following switchings of the corresponding optimal control :

and the smallest value of the function coincides with .

When minimizing the function numerically on the set , the following switchings of the corresponding optimal control are found:

and the smallest value of the function is also equal to .

We note that similar phenomena also occur for the situation .

These results for and demonstrate the optimality of the corresponding solutions discussed at the beginning of this section on a wider set of piecewise constant controls with a predetermined number of switchings.

11. Conclusions

The paper considers a bilinear control system that models the interaction between drug-sensitive and drug-resistant cancer cells over a given time interval, which is the general period of melanoma treatment. This system also contains a control function responsible for switching between the period of taking drugs in the treatment of illness and the period of rest, and vice versa. To determine an effective protocol for switching between these periods, the task was to minimize the cancer load both during the entire period of melanoma treatment and at the end of the time interval. A feature of such a problem is that it may not have an optimal solution due to the nonconvexity of the control set. This shortcoming was eliminated by taking the convex hull of this set and then considering a relaxed minimization problem for the original controlled bilinear system. Then, a detailed analytical analysis of such a minimization problem was carried out, and it turned out that only two situations are possible for the corresponding optimal solution: either the optimal solution of the relaxed minimization problem coincides with the optimal solution of the original minimization problem, or the optimal solution of the relaxed minimization problem contains a singular arc corresponding to the sliding mode in the original minimization problem. The last situation is the most interesting, since it is implemented with the help of optimal controls containing strongly oscillating piecewise constant sections, which, obviously, have no medical meaning.

From a medical point of view, if the optimal solution contains singular arc, this means that in certain cases (for some patients) the treatment must take a singular form, so the optimal solution will not just “jump” between off and on treatment, but could be in the state somewhere in between. Thus, it was found that the optimal control would take not only the values 0 and 1 but can take a singular form and take the values , or , or , etc., and that it may be optimal for the patient to “stay” on that special ray. What would that mean? Remember that the dosage of the drug for the stated problem is not modulated and is not a control function.

Naturally, such optimal control could not be associated with a reasonable treatment protocol within the framework of the proposed model. The doctor treating the patient relies in her decisions on the results of medical examinations and tests. So, she would like to have an optimal treatment schedule from which she could presumably be able to tell how many “treat-not treat” switches the patient can tolerate. Based on this, it was further proposed to replace optimal controls with strongly oscillating piecewise constant portions by piecewise constant controls with a given number of switchings, which are variable and whose optimal values are found as a result of solving some minimization problem. We have written a computer program in Maple that approximates the patient’s “movement” along special ray with a piecewise constant function (transition from 0 to 1 or vice versa) in the order depending on the patient’s health. The results obtained are quite stunning—if the cancer patient approaches this special ray at time , (T is the duration of treatment) and depending on which side (left or right) (it depends on whether the patient has more melanoma-resistant or more susceptible cells), the clinician can choose the optimal length of “on” and “off” periods and their alternation in accordance with our optimal treatment protocol that minimizes the overall cancer load.

Numerical calculations have shown that such a replacement is quite acceptable and its efficiency increases, but not too much, with an increase in the given number of switchings. These calculations were carried out for the specific values of the parameters of the bilinear control model, its initial conditions, and the time interval.

Moreover, we note that the problem investigated in the paper can be used for educational purposes in an advanced/graduate course of optimal control theory and its applications. On the one hand, the problem is “simple” from the point of view of its complete analytical study, and on the other hand, since the singular arc in the relaxed optimal control problem acts as a sliding mode in the original optimal control problem. Note that all results are unique and substantiated analytically.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.K. and E.G.; methodology, E.K. and E.G.; software, E.K.; validation, E.K. and E.G.; formal analysis, E.K.; investigation, E.K. and E.G.; resources, E.K. and E.G.; data curation, not applicable; writing—original draft preparation, E.K. and E.G.; writing—review and editing, E.K. and E.G.; visualization, E.K. and E.G.; supervision, E.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dominique Wodarz and Natalia Komarova for helpful consultations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- White, R.R.; Stanley, W.E.; Johnson, J.L.; Tyler, D.S.; Seigler, H.F. Long-term survival in 2.505 patients with melanoma with regional lymph node metastasis. Ann. Surg. 2002, 235, 879–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cancer Institute. Melanoma Treatment (PDQ)—Health Professional Version. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/types/skin/hp/melanoma-treatment-pdq (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Kopnin, B.P. Genome instability and oncogenesis. Mol. Biol. 2007, 41, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatelain, C.; Ciarletta, P.; Ben Amar, M. Morphological changes in early melanoma development: Influence of nutrients, growth inhibitors and cell-adhesion mechanisms. J. Theor. Biol. 2011, 290, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Batus, M.; Waheed, S.; Ruby, C.; Petersen, L.; Bines, S.D.; Kaufman, H.L. Optimal management of metastatic melanoma: Current strategies and future directions. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2013, 14, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsur, N.; Kogan, Y.; Rehm, M.; Agur, Z. Response of patients with melanoma to immune checkpoint blockade—insights gleaned from analysis of a new mathematical mechanistic model. J. Theor. Biol. 2020, 485, 110033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wargo, A.R.; Huijben, S.; de Roode, J.C.; Shepherd, J.; Read, A.F. Competitive release and facilitation of drug-resistant parasites after therapeutic chemotherapy in a rodent malaria model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 19914–19919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyce, J.; Leonard, S.; Canupp, D.; Schulz, S.; Wong, S. Epigenetic mechanisms of drug resistance: Drug-induced DNA hypermethylation and drug resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 2960–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, S.M.; Dunagin, M.C.; Torborg, S.R.; Torre, E.A.; Emert, B.; Krepler, C.; Beqiri, M.; Sproesser, K.; Brafford, P.A.; Xiao, M.; et al. Rare cell variability and drug-induced reprogramming as a mode of cancer drug resistance. Nature 2017, 546, 431–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haridas, P.; Penington, C.J.; McGovern, J.A.; Sean McElwain, D.L.; Simpson, M.J. Quantifying rates of cell migration and cell proliferation in co-culture barrier assays reveals how skin and melanoma cells interact during melanoma spreading and invasion. J. Theor. Biol. 2017, 423, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.B.; Menzies, A.M.; Zimmer, L.; Eroglu, Z.; Ye, F.; Zhao, S.; Rizos, H.; Sucker, A.; Scolyer, R.A.; Gutzmer, R.; et al. Acquired BRAF inhibitor resistance: A multicenter meta-analysis of the spectrum and frequencies, clinical behaviour, and phenotypic associations of resistance mechanisms. Eur. J. Cancer. 2015, 51, 2792–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Brown, J.S.; Eroglu, Z.; Anderson, A.R.A. Adaptive therapy for metastatic melanoma: Predictions from patient calibrated mathematical models. Cancers 2021, 13, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albano, G.; Giorno, V.; Román-Román, P.; Román-Román, S.; Torres-Ruiz, F. Estimating and determining the effect of a therapy on tumor dynamics by means of a modified Gompertz diffusion process. J. Theor. Biol. 2015, 364, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhmetzhanov, A.R.; Kim, J.W.; Sullivan, R.; Beckman, R.A.; Tamayo, P.; Yeang, C.-H. Modelling bistable tumour population dynamics to design effective treatment strategies. J. Theor. Biol. 2019, 474, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rommelfanger, D.M.; Offord, C.P.; Dev, J.; Bajzer, Z.; Vile, R.G.; Dingli, D. Dynamics of melanoma tumor therapy with vesicular stomatitis virus: Explaining the variability in outcomes using mathematical modeling. Gene Ther. 2012, 19, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolpak, E.P.; Frantsuzova, I.S.; Evmenova, E.O. Oncological diseases in St. Petersburg, Russia. Drug Invent. Today 2019, 11, 510–516. [Google Scholar]

- Goncharova, A.B.; Zimina, E.I.; Kolpak, E.P. Mathematical model of melanoma. Int. Res. J. 2021, 7, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakode, C.M.; Padhi, R.; Kapoor, S.; Rallabandi, V.P.S.; Roy, P.K. Multimodal therapy for complete regression of malignant melanoma using constrained nonlinear optimal dynamic inversion. Biomed. Signal Process. 2014, 13, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, K.; Cheng, M.; Xin, X. Optimal switching control for drug therapy process in cancer chemotherapy. Eur. J. Control 2018, 42, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadi, A.; Keighobadi, F.; Nekoukar, V.; Ebrahimi, M. Finite-set model predictive control of melanoma cancer treatment using signaling pathway inhibitor of cancer stem cell. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2021, 18, 1504–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodarz, D.; Komarova, N.L. Computational Biology of Cancer; World Scientific: Singapore; Hackensack, NJ, USA; London, UK; Hong Kong, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, W.-Y.; Hanin, L. Handbook of Cancer Models with Applications; World Scientific: Singapore; Hackensack, NJ, USA; London, UK; Hong Kong, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kuang, Y.; Nagy, J.D.; Eikenberry, S.E. Introduction to Mathematical Oncology; CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA; London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Padmanabhan, R.; Meskin, N.; Al Moustafa, A.-E. Mathematical Models of Cancer and Different Therapies; Springer: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, R.; Teo, K.L. Optimal Control of Drug Administration in Cancer Chemotherapy; World Scientific: Singapore; Hackensack, NJ, USA; London, UK; Hong Kong, China, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Schättler, H.; Ledzewicz, U. Optimal Control for Mathematical Models of Cancer Therapies: An Application of Geometric Methods; Springer: New York, NY, USA; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; Dordrecht, The Netherlands; London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Michor, F.; Hughes, T.P.; Iwasa, Y.; Branford, S.; Shah, N.P.; Sawyers, C.L.; Nowak, M.A. Dynamics of chronic myeloid leukaemia. Nature 2005, 435, 1267–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasetti, C.; Levy, D. An elementary approach to modeling drug resistance in cancer. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2010, 7, 905–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, K. An elementary mathematical modeling of drug resistance in cancer. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2020, 18, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartman, P. Ordinary Differential Equations; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Bressan, A.; Piccoli, B. Introduction to the Mathematical Theory of Control; AIMS: Springfield, IL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.B.; Marcus, L. Foundations of Optimal Control Theory; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Pontryagin, L.S.; Boltyanskii, V.G.; Gamkrelidze, R.V.; Mishchenko, E.F. Mathematical Theory of Optimal Processes; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Afanasiev, V.N.; Kolmanovskii, V.B.; Nosov, V.R. Mathematical Theory of Control Systems Design; Springer Science: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Utkin, V.I. Sliding Modes in Control and Optimization: Theory and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, C.; Spurgeon, S.K. Sliding Mode Control: Theory and Applications; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Grigorieva, E.V.; Khailov, E.N. Optimal intervention strategies for a SEIR control model of Ebola epidemics. Mathematics 2015, 3, 961–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorieva, E.V.; Deignan, P.B.; Khailov, E.N. Optimal control problem for a SEIR type model of Ebola epidemics. Rev. Matemática Teoría Apl. 2017, 24, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Grigorieva, E.; Khailov, E. Optimal preventive strategies for SEIR type model of the 2014 Ebola epidemics. Dynam. Cont. Dis. Ser. B 2017, 24, 155–182. [Google Scholar]

- Grigorieva, E.; Khailov, E. Determination of the optimal controls for an Ebola epidemic model. Discret. Contin. Dyn. Syst. 2018, 11, 1071–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorieva, E.; Khailov, E.; Korobeinikov, A. An optimal control problem in HIV treatment. Discret. Contin. Dyn. Syst.-Ser. S 2013, 2013, 311–322. [Google Scholar]

- Grigorieva, E.V.; Khailov, E.N.; Bondarenko, N.V.; Korobeinikov, A. Modeling and optimal control for antiretroviral therapy. J. Biol. Syst. 2014, 22, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).