Abstract

The remote authentication scheme is a cryptographic protocol incorporated by user–server applications to prevent unauthorized access and security attacks. Recently, a two-factor authentication scheme using hard problems in elliptic curve cryptography (ECC)—the elliptic curve discrete logarithm problem (ECDLP), elliptic curve computational Diffie–Hellman problem (ECCDHP), and elliptic curve factorization problem (ECFP)—was developed, but was unable to address several infeasibility issues while incurring high communication costs. Moreover, previous schemes were shown to be vulnerable to privileged insider attacks. Therefore, this research proposes an improved ECC-based authentication scheme with a session key agreement to rectify the infeasible computations and provide a mechanism for the password change/update phase. The formal security analysis proves that the scheme is provably secure under the random oracle model (ROM) and achieves mutual authentication using BAN logic. Based on the performance analysis, the proposed scheme resists the privileged insider attack and attains all of the security goals while keeping the computational costs lower than other schemes based on the three hard problems. Therefore, the findings suggest the potential applicability of the three hard problems in designing identification and authentication schemes in distributed computer networks.

Keywords:

elliptic curve cryptography; key agreement; provable security; password authentication; smart card MSC:

94A60

1. Introduction

Currently, more Internet users depend on user–server-based applications for e-commerce, banking services, and operational networks because of their convenience and efficiency. These applications allow users to obtain numerous services remotely at any time, anywhere. This type of communication between the user and server usually involves data transmission and financial transactions over a public channel, such as the Internet. Unfortunately, sharing sensitive information over the public channel is insecure, exposing both parties to greater security risks and attacks. Therefore, a remote authentication scheme is imperative for verifying legal users and defending against unauthorized usage.

The first password authentication scheme by Lamport [1] is called a single-factor-based scheme because the user only needs to present a password to be verified by the server. However, studies have shown that single-factor-based schemes are subjected to security pitfalls. Since then, remote authentication schemes were designed based on two or more factors to increase the systems’ security. For example, in addition to a password, the user is required to possess a registered smart card or a mobile device. For a multi-factor scheme, the user may also need to present a biometric trait such as a fingerprint.

Many two-factor smart-card-based remote authentication schemes have been proposed. Figure 1 depicts the general architecture of the two-factor authentication scheme, which consists of multiple users and a single server. In this system, the remote user must register with a valid identity and secret password with the server. Next, the server issues a legal smart card to the first-time registered user to access the required services. The smart card is employed to store the registered user’s secret credentials for future login requests and perform cryptographic computations during the authentication process.

Figure 1.

Architecture of two-factor remote authentication with multiple users and a single server.

Like other cryptographic schemes and protocols, the two-factor-based authentication schemes rely on the security primitives of one-way hash functions (e.g., SHA-2 [2]) and number-theoretic computational hard problems in public-key cryptography. For instance, the works by [3,4,5] were developed based on only one-way hash functions. Other schemes were built based on the intractability of hard problems, including the integer factorization problem in RSA [6], discrete logarithm problem [7], and elliptic curve discrete logarithm problem [8,9] in elliptic curve cryptography (ECC). ECC-based schemes are more prevalent than RSA-based schemes due to the smaller key size requirement [10].

In 2008, Juang et al. [11] first proposed an ECC-based remote password authentication scheme with a session key agreement for the client–server environment. The security of their scheme depended on two hard problems in ECC: the elliptic curve discrete logarithm problem (ECDLP) and elliptic curve computational Diffie–Hellman problem (ECCDHP). They claimed that their scheme preserved all of the security merits of the scheme by Fan et al. [12] and reduced the computational cost. Subsequently, Sun et al. [13] and Li et al. [14] found weaknesses in the design of the scheme by Juang et al. [11] in terms of the password-change phase and session key distribution, the inefficiency of using two secret keys, and user anonymity. Hence, both suggested enhancements to fix the design flaws.

Several improvements by [15,16,17] were presented to overcome the problems in the Sun et al. [13] scheme to resist offline password-guessing attacks, denial-of-service attacks, smart card loss attacks, and key compromise impersonation attacks. Later, Liu and Ma [18] found that the scheme by Sun et al. [13] still lacked user untraceability and resolved the issue with an improved efficiency. Then, the scheme by Li et al. [14] was found to suffer from desynchronization attacks [17,19]. Hence, Tsai et al. [19] and Byun [20] proposed new schemes with formal security model proofs to strengthen the scheme’s security. Both schemes maintained the security of their schemes based on the hard problems of ECDLP and ECCDHP.

Wang et al. [21] proposed a two-factor authentication scheme for a ubiquitous computing environment based on ECDLP. Their scheme was shown to provide better security features and a lower computational cost. Subsequently, Wu et al. [22] showed that the scheme by Wang et al. [21] could not resist offline dictionary attacks, known session key attacks, denial-of-service attacks, and impersonation attacks using a compromised smart card. Meanwhile, Chang et al. [23] pointed out that the scheme by Wang et al. [21] did not satisfy mutual authentication and could not be incorporated using a multipurpose smart card. Hence, both [22,23] proposed new improved schemes to overcome these weaknesses.

In another study, Wang [24] found some security flaws in the design of the single-factor scheme by Islam and Biswas [25]. They developed a new scheme using smart cards with the security foundation of ECDLP, ECCDHP, and a one-way hash function. They claimed that their scheme offered resistance to impersonation attacks and improved the computational efficiency by removing the expensive bilinear pairing operation. Later, Odelu et al. [26] presented further improvements to resist the offline password attack and provide user anonymity. They proved that their scheme could withstand various security attacks and showed that it was provably secure under the random oracle model (ROM).

Other recent works have also proposed ECC-based two-factor schemes with added security features. Madhusudhan et al. [27] suggested a new scheme based on ECC and a fuzzy verifier for quick password verification. They showed that their scheme could resist replay attacks and provide security of the secret key, user untraceability, and perfect forward secrecy. Finally, Kumari et al. [28] designed a novel scheme that provides resistance against offline password-guessing attacks, lost smart card attacks, replay attacks, impersonation attacks, desynchronization attacks, and insider attacks.

1.1. Motivations and Contributions

In 2014, Qu and Tan [29] proposed a two-factor scheme based on the security of a collision-resistant one-way hash function, ECDLP, ECCDHP, and the elliptic curve factorization problem (ECFP). Later, Huang et al. [30] suggested security enhancements to overcome the offline password-guessing attack and user impersonation attack. However, in 2016, Maitra et al. [31] showed that the scheme by Huang et al. [30] was vulnerable to a new forgery attack. They also pointed out that the scheme by [30] could not be implemented in real-world problems because of some computational infeasibility issues. Later, both Chaudhry et al. [32] and Mehmood et al. [33] also suggested improvements to repel the user impersonation attack.

Although Maitra et al. [31] suggested security enhancements to the scheme by Huang et al. [30], their scheme exacted a higher computational cost compared to schemes by [29,30,32,33]. Even though the schemes designed by Chaudhry et al. [32] and Mehmood et al. [33] improved the efficiency of the scheme by Huang et al. [30], their schemes overlooked the computational infeasibility issues. In addition, their schemes did not provide a mechanism for the password change phase and were unable to withstand the privileged insider attack. Moreover, previously improved schemes by Maitra et al. [31] and Mehmood et al. [33] did not maintain all three hard problems in ECC: ECDLP, ECCDHP, and ECFP.

Therefore, this study proposes a new ECC-based two-factor remote authentication scheme based on Chaudhry et al. [32] to resolve these shortcomings. The scheme retains all of the security attributes of the scheme by Maitra et al. [31], including user traceability and efficient local password changeability. In addition, the proposed scheme is proven to withstand offline password-guessing attacks, replay attacks, privileged insider attacks, stolen-verifier attacks, and key-compromise impersonation attacks. Based on the formal security analysis, the proposed scheme is provably secure under ROM against adversary threats. Furthermore, the analysis showed that the proposed scheme is more efficient than the scheme by Maitra et al. [31].

1.2. Structure of the Article

Section 2 briefly describes the security fundamentals, adversary model, a review of Chaudhry et al. [32], and the drawbacks that are considered when developing the proposed scheme. Next, Section 3 explains the new proposed scheme. The formal security proof, informal security analysis, and formal verification using BAN logic are presented in Section 4. The proposed scheme is compared with other chosen schemes in the performance analysis according to the security and efficiency aspects given in Section 5. Then, Section 6 discusses the potential applications of the proposed scheme and future research considerations. Finally, Section 7 presents the conclusion.

2. Preliminaries

This section provides a brief overview of the mathematical concepts, formal definitions, adversary model, security goals, and BAN logic that served as the foundation in the design of the proposed scheme. Table 1 shows the notations and descriptions used in this paper.

Table 1.

Notations and descriptions.

2.1. Hash Function

A cryptographic one-way function has the following properties:

- The function h takes an arbitrary length input and returns a fixed l-bit length message digest .

- The function h is one-way; it is trivial to compute , but computationally infeasible to find the inverse .

- The function h is collision-resistant; it is computationally infeasible to find two inputs such that .

Examples of secure hash algorithms, such as the SHA-2 family of hash functions [2], can be adopted in the proposed scheme.

Definition 1.

An adversary ’s advantage in finding a collision is the probability of selecting the pair at random within polynomial time so that and , defined formally as

If , for any sufficiently small negligible function , the one-way hash function is collision-resistant.

2.2. Elliptic Curve over Finite Fields

The elliptic curve over a finite field is defined as (mod p), where p is prime and satisfies the condition (mod p). If point and , then the elliptic point multiplication operation is the repeated point addition k times on point P.

The security of the elliptic curve cryptosystem is based on the following computational hard problems.

Definition 2.

Given two points P, , the elliptic curve discrete logarithm problem (ECDLP) is to find the integer . The advantage of an adversary in solving the ECDLP within execution time is defined as

For any probabilistic polynomial time-bounded algorithm and for any sufficiently small negligible function , if , then the ECDLP is intractable.

Definition 3.

Given three points P, , , the elliptic curve computational Diffie–Hellman problem (ECCDHP) is to find the point where s, . The advantage of an adversary in solving the ECCDHP within execution time is defined as

For any probabilistic polynomial time-bounded algorithm and for any sufficiently small negligible function , if , then the ECCDHP is intractable.

Definition 4.

Given two points P, , the elliptic curve factorization problem (ECFP) is to find two points , where s, . The advantage of an adversary in solving the ECFP within execution time is defined as

For any probabilistic polynomial time-bounded algorithm and for any sufficiently small negligible function , if , then the ECFP is intractable.

2.3. Adversary Model

The adversary model by Dolev and Yao [34] was considered for communications over an insecure public channel, and the following assumptions were made.

- A1: An adversary can trap, delete, or alter the messages transmitted over the public channel.

- A2: An adversary can retrieve the information stored in the smart card using power monitoring techniques as explained in [35,36].

- A3: An adversary can guess the identity or password using a dictionary attack. However, A cannot guess both the identity and password simultaneously within polynomial time [37].

- A4: An adversary can be a non-registered user who tries to attack the authentication system [31].

- A5: The server is considered a trusted authority, and the adversary , as a privileged insider, cannot extract the server’s secret key s.

2.4. Security Goals

The following goals are defined for an ideal authentication scheme, as listed in [31,38].

- Mutual authentication: Both the server and the user can authenticate each other. No adversary can impersonate a legal user or server.

- Session key agreement: A session key should be created as the final step in the mutual authentication phase. Afterward, the communication between both parties can be encrypted using the shared session key.

- Forward secrecy: Even if the long-term private keys are compromised, the previous session keys cannot be used by any adversary to forge other session keys.

- User anonymity: A user’s identity should not be transmitted explicitly over an insecure channel. This ensures that the user’s sensitive information is protected from an adversary , even with the knowledge of login information or access to the server.

- User traceability: The server should be able to trace the sender of the login request message to avoid the denial-of-service attack. A database of registered users should be maintained by the server.

- Local password verification: A smart card can verify the user identity and password in the login phase before generating the login request message. This way, the smart card can reduce computational overhead by avoiding unnecessary calculations.

- Local password changeability: Users can update/change their passwords independently without the server’s assistance. The smart card must be able to detect unauthorized password update requests through the wrong input of the user identity and old password.

2.5. BAN Logic

Burrows–Abadi–Needham (BAN) logic [39] is a set of rules based on belief modal logic for analyzing authentication protocols. The notations used in BAN logic and their descriptions are provided in Table 2. Table 3 lists the BAN logic rules, descriptions, and symbolic forms that are used in proving the mutual authentication property of the proposed scheme.

Table 2.

BAN logic notations and descriptions.

Table 3.

BAN logic rules, descriptions, and symbolic forms.

2.6. Review of the Scheme by Chaudhry et al.

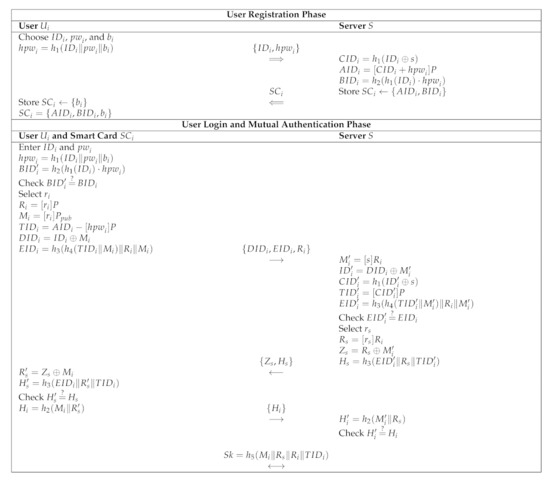

In this section, a brief description of the scheme by Chaudhry et al. [32] is presented. The authentication scheme by Chaudhry et al. [32] is an improvement of the scheme proposed by Huang et al. [30]. Their scheme consists of four phases: (1) system initialization, (2) user registration, (3) user login, and (4) mutual authentication. Figure 2 summarizes the authentication scheme by Chaudhry et al. [32]. Each of the phases is reviewed as follows.

Figure 2.

Scheme by Chaudhry et al. [32] based on ECC.

- (1)

- System initialization phase

The Server S selects an elliptic curve over , where p is k-bit prime, and a base point P of order n from of , where n is a large number for security purposes. Then, S computes the secret key and public key pair such that , where s is a random integer . The Server S also chooses five distinct one-way hash functions , where . Finally, the Server S publishes and keeps s secret.

- (2)

- User registration phase

In this phase, the user chooses an identity , a password , and a random integer . Then, the user computes and sends to S through a secure channel. Next, the Server S computes , , and . The Server S stores into the smart card and issues the card securely to . Once the user receives the smart card , the user will update the value into . Hence, the smart card .

- (3)

- User login phase

In the login phase, the registered user inserts the smart card into a remote terminal and enters the identity and password, . Next, the smart card computes and , and checks if the equation holds. Otherwise, the login phase is aborted. Then, the smart card selects a random integer and computes , , , , and . The smart card submits the login request message to S through a public channel.

- (4)

- Mutual authentication phase

Once the Server S receives the login request message, it computes , , , , and , and checks if the equation holds. If the equation does not hold, the login request is rejected. Otherwise, the Server S generates a random integer and computes , , and , and sends the response message to through the public channel.

After receiving the response message, the user computes , and , and checks if holds. If the equation does not hold, the user disconnects from S. Otherwise, the user computes and sends the message to S. Next, the Server S computes and checks if . If the equation holds, the user and the Server S achieve mutual authentication and agree on the session key . Otherwise, the session is terminated.

2.7. Drawbacks of Scheme by Chaudhry et al.

This section highlights the security drawbacks of the scheme by Chaudhry et al. [32].

- (1)

- Computational infeasibility

During the mutual authentication phase, once the Server S has verified the equation , it then computes the value . Then, the user retrieves the value of as . However, the XOR operation is undefined on the elliptic curve since it is not a closed operation under the elliptic curve group. The undefined XOR operation on two elliptic curve points was highlighted by Maitra et al. [31] as a drawback of the scheme by Huang et al. [30]. However, Chaudhry et al. [32] did not address the issue in the modification of their scheme. Hence, their scheme maintained the infeasible computations of the scheme by Huang et al. [30].

- (2)

- Weakness to privileged insider attack

Consider an adversary being a privileged insider who can monitor data transmission over a secure channel. In the registration phase of the scheme by Chaudhry et al. [32], the user submits to the Server through a secure channel. Hence, has access to and . If possesses a lost/stolen smart card , then it is possible for to launch an offline password-guessing attack. For example, assume that has the values , , and retrieved from by Assumption A2. Then, can obtain the correct password by checking the equation , where is the guessed password. Therefore, the scheme by Chaudhry et al. [32] cannot resist the privileged insider attack.

- (3)

- Unable to trace user

After receiving the login request message , the Server computes all of the values , , , and straight away before verifying the value . Based on discussions in [31], the Server was shown to be vulnerable to forgery attacks because it is unable to check if the login request comes from a registered user. Maitra et al. [31] also highlighted that the user untraceability feature is undesirable since the Server cannot provide user-specific services. In the scheme by Chaudhry et al. [32], the Server did not save any information about the registered users; therefore, it cannot trace the sender of the login request message.

- (4)

- No mechanism for password change/update

In the scheme by Chaudhry et al. [32], they rectified the computation of during the user registration phase to overcome the user impersonation attack. Specifically, the value was computed as . Note that the value of is stored in the memory of the smart card and its value depends on the password and random integer . Consequently, the corresponding computation for the new value of should also be rectified when a user changes/updates a new password and new random integer . However, the password change/update phase was not discussed. Therefore, their scheme did not provide a mechanism for the password change/update.

3. Proposed Scheme

This section presents the proposed ECC-based two-factor remote authentication scheme. Following the scheme by [32], the Server acts as a trusted authority that is responsible for preparing the global parameters and public and secret keys, as well as issuing smart cards to newly registered users. The proposed scheme also incorporates timestamps to verify the freshness of transmitted messages, similar to the design by [31]. Generally, the scheme consists of five phases: (1) system initialization, (2) user registration, (3) user login, (4) mutual authentication, and (5) password change/update. Figure 3 presents an overview of the proposed scheme.

Figure 3.

The proposed ECC-based remote user password authentication scheme.

3.1. System Initialization Phase

- The Server S selects an elliptic curve over , where p is k-bit prime and a base point P of order n from of , where n is a large number for security purposes.

- The Server S computes the secret key and public key pair such that , where s is a random integer .

- The Server S chooses a cryptographic one-way hash function .

- The Server S publishes and keeps s secret.

3.2. User Registration Phase

A new user must register with the Server S before requesting access to the services. The registration phase is detailed as follows:

- The user chooses an identity and password , and generates a random integer . Then, the user computes and sends to S through a secure channel.

- The Server S computes and checks the availability of . If the value is in the database of registered users, the user will be asked to input a new . Otherwise, the Server stores into the database. Following the approach taken by [31], this step is added to allow S to trace the user during the login phase.

- The Server S computes , , stores into the smart card , and issues the card securely to .

- Once the user receives the smart card , the user computes and stores the value into . Hence, the smart card .

3.3. User Login Phase

In the login phase, a user submits a login request message to the Server S for access to the system. First, the user inserts the smart card into a remote terminal and enters the identity and password, . The executes the following steps.

- The smart card computes , , and , and checks if holds. If the equation holds, then has entered the correct identity and password, and , respectively. Otherwise, the login phase is aborted.

- The smart card selects a random integer and computes , where and are the x-component and y-component of the point , respectively.

- The smart card computes , , , and , where is the timestamp of ’s login request submission.

- The smart card submits the login request message to S through a public channel.

3.4. Mutual Authentication Phase

Once the Server S receives the login request message at time , it proceeds with the following steps.

- The Server S checks if , where is the allowed time transmission delay. If the time difference does not hold, the login request is rejected.

- The Server S computes in order to retrieve the identity and . Then, the Server S checks the validity of by searching the value of in the registered users’ database. If is not in the database, the login request is rejected.

- The Server S computes and , and checks if holds. If the equation does not hold, the login request is rejected.

- The Server S generates a random integer , computes , , and , and sends the response message to through the public channel.

- Once the user receives the response message at time , the user checks if . If the time difference does not hold, the user disconnects from the Server S.

- The user computes , and , and checks if holds. If the equation does not hold, the user disconnects from S.

- The user computes and sends the message to S.

- The Server S checks if . If the time difference does not hold, the session is terminated.

- The Server S computes and checks if . If it holds, the user and the Server S achieve mutual authentication and agree on the session key . Otherwise, the session is terminated.

3.5. Password Change/Update Phase

The user can change or update the password during this phase by initially inserting the smart card into a remote terminal with the identity and password . Then, the smart card performs the following steps.

- The smart card computes , , and , and checks if . If the equation is true, the smart card asks the user to submit a new password . Otherwise, the request is rejected.

- Once the user enters the new password , the smart card generates a new random integer and computes the new values , , , and .

- Finally, the smart card updates the values as .

3.6. Proof of Correctness

The propositions and proof of correctness are presented below for the sake of completeness.

Proposition 1.

If the user enters the identity and password correctly, and the user login phase and Steps 1-2 of the mutual authentication phase run smoothly, then the Server S will obtain the correct , which is shown as follows.

Proposition 2.

Assume that the user receives the response message from the Server S and passes the timestamp check in Step 5 of the mutual authentication phase. The equation in Step 6 will retrieve the correct value as follows.

Proposition 3.

If the user enters the correct identity and password , and the equation holds, the smart card can compute the new value without the knowledge of , which is shown as follows.

4. Security Analysis of the Proposed Scheme

This section analyzes the security aspect of the proposed scheme. First, the formal security proof is presented based on the ROM using the proof by contradiction technique, which is similar to [26,32,33]. Next, the attainment of security goals is discussed. Then, the proposed scheme is shown to withstand several identified security attacks. Finally, the formal verification of the scheme using BAN logic is provided to prove the mutual authentication property.

4.1. Formal Security Analysis

The formal proof demonstrates that the proposed scheme is provably secure against an adversary from obtaining the identity , secret key s, and shared session key . In this approach, a mathematical proof is presented to show that the security of the proposed scheme is reduced to the ability of the adversary to break four computationally intractable problems: the collision-resistant one-way hash function, ECDLP, ECCDHP, and ECFP.

The formal proof begins by assuming the adversary knows the values for the parameters stored in the smart card, and the messages , , and transmitted in the public channel, as described in the adversary model in Section 2.3. In addition, the adversary is assumed to have access to the following oracles.

- : Given the input , the oracle yields the output x.

- : Given the input P and , the oracle yields the output a.

- : Given the input P, , and , the oracle yields the output .

- : Given the input P and , the oracle yields the output and .

Theorem 1.

Assuming that the cryptographic one-way hash function acts like a true random oracle, and ECDLP, ECCDHP, and ECFP are computationally intractable problems, then the proposed ECC-based authentication scheme is provably secure against an adversary for deriving the identity , secret key s, and session key .

Proof.

Suppose an adversary is constructed to derive the identity , secret key s, and session key by running the algorithm , as shown in Algorithm 1 for the proposed ECC-based scheme. Based on Assumptions A1 and A2 in Section 2.3, the adversary can obtain the transmitted messages , , and , and the parameters stored in the smart card. Then, the success probability of is given as . The advantage for the is the maximum of the success probability taken over all with execution time t, , where , , , and denote the number of queries made to oracles , , , and , respectively.

| Algorithm 1 for deriving identity , secret key s, and session key . |

| 1: Eavesdrop the login message |

| 2: Call on input to obtain |

| 3: Call on input , , and P to obtain as |

| 4: if then |

| 5: Call on input and P to obtain and as |

| 6: if then |

| Compute |

| 8: Compute |

| 9: if then |

| 10: Accept as the correct user’s identity |

| 11: Call on input and P to obtain as |

| 12: Call on input to obtain as |

| 13: Compute |

| Eavesdrop the message |

| 15: Compute |

| 16: Compute |

| 17: if then |

| 18: Accept as the correct secret key |

| 19: Eavesdrop the message |

| 20: Compute |

| 21: if then |

| 22: Compute as the correct shared session key |

| 23: return 1 (Success) |

| 24: else |

| 25: return 0 (Fail) |

| 26: end if |

| 27: else |

| 28: return 0 (Fail) |

| 29: end if |

| 30: else |

| 31: return 0 (Fail) |

| 32: end if |

| 33: else |

| 34: return 0 (Fail) |

| 35: end if |

| 36:else |

| 37: return 0 (Fail) |

| 38: end if |

Based on algorithm , suppose the adversary can compute the inverse of a cryptographic one-way hash functions, and solve ECDLP, ECCDHP, and ECFP by using the oracles , , , and . Then, the adversary wins the game and successfully obtains , s, and . However, according to Definitions 1–4, the advantages , , , and , for any sufficiently small negligible functions . Hence, it must be that for any sufficiently small . Therefore, the theorem is proven. □

4.2. Attainment of Security Goals

This section analyzes the proposed scheme’s attainment of security goals as explained in Section 2.4.

- (1)

- Mutual authentication

The proposed scheme includes mutual authentication steps for verifying the legality of the user and the Server. The Server authenticates the user by checking the value in the registered users’ database. Next, the user authenticates the Server by checking the value of . Although an adversary may obtain the value of , and by Assumptions A1 and A2, the adversary needs to compute the values of and , which are not transmitted in the public channel. Furthermore, and are secured by the ECDLP and ECFP. Therefore, the proposed scheme provides mutual authentication.

- (2)

- Session key agreement

After completing the mutual authentication steps, both the user and Server compute a shared session key . Since the adversary does not know , , and , the session key cannot be computed directly due to the cryptographic one-way hash function. Hence, the shared session key is protected in the proposed scheme.

- (3)

- Forward secrecy

In the proposed scheme, the session keys are computed using the values and , which are calculated based on random numbers and . Even if an adversary obtains the secret key s, the adversary still cannot obtain any information from the previous session keys. Thus, the proposed scheme provides forward secrecy.

- (4)

- User anonymity

According to Assumption A2, an adversary may extract all of the values in the smart card. The is contained in the parameters and . However, the adversary needs to invert a one-way hash output, which is impossible in polynomial time, as shown in Theorem 1. As a result, the proposed scheme provides user anonymity.

- (5)

- User traceability

Following Maitra et al. [31], the server should be able to trace the sender of the login request message by confirming that the sender is indeed a user registered in the database. The proposed scheme still maintains user anonymity because the user’s is hidden and secured by the secret key s in the parameter . Therefore, the proposed scheme allows the Server to trace the user.

- (6)

- Local password verification

The proposed scheme provides wrong password input detection by the smart card during the login phase by checking the value . The incorrect combination of and will be detected before preparing the login request message. Hence, the proposed scheme provides local password verification.

- (7)

- Local password changeability

The password change/update phase permits the user to modify the password without contacting the Server. Since the smart card can verify the password and identity locally through a remote terminal, it can compute and update the parameters . Therefore, the proposed scheme provides efficient local password changeability.

4.3. Resistance to Security Attacks

This section presents the proposed scheme’s ability to withstand several security attacks.

- (1)

- Offline password-guessing attack

Suppose that an adversary obtains a lost/stolen smart card and retrieves . The adversary must guess the user ’s identity and password to compute , , and . However, according to Assumption A3, it is impossible to guess both and within polynomial time. Hence, the proposed scheme can withstand the offline password-guessing attack.

- (2)

- Replay attack

By Assumption A1, an adversary can intercept all of the messages transmitted through the public channel. Since the messages are generated using the random numbers (, ) and timestamps (, , ), the Server S will notice the repeated message submissions. Hence, it is impossible for to replay intercepted messages. Therefore, the proposed scheme can resist replay attacks.

- (3)

- Privileged insider attack

In this attack, suppose a privileged insider as an active adversary who obtains the identity by monitoring data transmitted over a secure channel during the registration phase. In addition, assume that extracts the values , , and from a lost/stolen smart card , as in Assumption A2. In the proposed scheme, cannot launch the password-guessing attack because the password is secured by . The adversary can try to retrieve the random number from . However, has to guess both and simultaneously within polynomial time, which contradicts Assumption A3. Thus, the proposed scheme can withstand the privileged insider attack.

- (4)

- Stolen-verifier attack

If an adversary gains access to the database of registered users, the adversary can try to extract the of a legal user . However, the Server’s database stores the value in secured by the collision-resistant one-way hash function. In addition, also cannot obtain the secret key s since it is protected by ECDLP. It is impossible for to retrieve . Therefore, the proposed scheme can resist stolen-verifier attacks.

- (5)

- Key-compromised impersonation attack

Assume an adversary obtains a compromised or stolen secret key s. Then, the adversary can try to impersonate a legal user to cheat the Server S. Still, the must first pass the verification check . Furthermore, the cannot create the login message because it is not possible to compute . Thus, the proposed scheme can withstand the key-compromised impersonation attack.

4.4. Formal Verification Using BAN Logic

This section provides the verification of the mutual authentication property for the proposed scheme using BAN logic [39]. The BAN logic analysis consists of four main steps: (1) defining the verification goals, (2) transforming the proposed scheme to its idealized form, (3) expressing the initial state assumptions, and (4) proving the security goals by using the BAN logic rules as in Table 3.

- (1)

- Verification goals

First, the BAN logic goals for the proposed scheme are defined and listed as follows.

- Goal 1:

- Goal 2:

- Goal 3:

- Goal 4:

- (2)

- Idealization of the proposed scheme

Next, the proposed scheme is transformed into the idealized form as follows.

- Message 1:

- Message 2:

- Message 3:

- (3)

- Initial state assumptions

The assumptions made on the initial state of the proposed scheme are listed below.

- A1: ;

- A2: ;

- A3: ;

- A4: ;

- A5: .

- (4)

- Proof using BAN logic

The security proof analysis is presented based on the goals, initial state assumptions, and BAN logic rules.

- Step 1: From Message 1, .

- Step 2: According to Step 1, A3, and applying the message-meaning rule, the statement is deduced.

- Step 3: By the freshness-conjuncatenation rule and A5 yields, .

- Step 4: From Step 2, Step 3, and the nonce-verification rule, then .

- Step 5: From Message 3, .

- Step 6: Applying the message-meaning rule to Step 5 and A1, then .

- Step 7: By the freshness-conjuncatenation rule and A5 yields, .

- Step 8: From Steps 6 and 7 using the nonce-verification rule, then .

- Step 9: By the belief rule, Step 4, and Step 8, .

- Step 10: From Step 9, A5, and the session key rule, then (Goal 3).

- Step 11: From A5, Step 9, Step 10, and the session-key verification rule, then (Goal 4).

- Step 12: From Message 2, .

- Step 13: Applying the message-meaning rule, from Step 12 and A2, then the statement is obtained.

- Step 14: By the freshness conjuncatenation rule and A4 yields, .

- Step 15: According to Step 13, Step 14, and applying the nonce verification rule, then .

- Step 16: By the session-key rule, Step 14, and Step 15, then (Goal 1).

- Step 17: Finally, from A4, Step 15, Step 16, and the session-key verification rule, (Goal 2).

Based on BAN logic analysis, all of the defined goals are achieved. Therefore, the proposed scheme is demonstrated to provide mutual authentication using the shared session key between and S.

5. Performance Analysis

This section explains the performance of the proposed scheme compared to similar schemes and improvements by [29,30,31,32,33]. Since this study focuses on the schemes that have been improved based on Qu and Tan [29], the compared schemes are chosen based on the underlying security of three hard problems in ECC (i.e., ECDLP, ECCDHP, and ECFP) in the general user–server application. Based on the literature search, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, only the works by Huang et al. [30] and Chaudhry et al. [32] fit this scope. The schemes by Maitra et al. [31] and Mehmood et al. [33] are also included in the performance comparison since they proposed enhancements based on Huang et al. [30].

Table 4 summarizes the security goals attainment and resistance to security attacks of every scheme based on the discussions in Section 4. The proposed scheme has been shown to achieve all of the security goals as given in Maitra et al. [31], which are formal security proof, mutual authentication, session key agreement, forward secrecy, user anonymity, user traceability, local password verification, and local password changeability. The proposed scheme has also been shown to withstand replay attacks, offline password-guessing attacks, privileged insider attacks, stolen-verifier attacks, insider attacks, and key-compromised impersonation attacks. Overall, the proposed scheme and Maitra et al. [31] outperformed other considered schemes in terms of security goals attainment. The proposed scheme performs better than all considered schemes based on the resistance to security attacks.

Table 4.

Attainment of security goals and resistance to security attacks of the proposed scheme and other similar schemes.

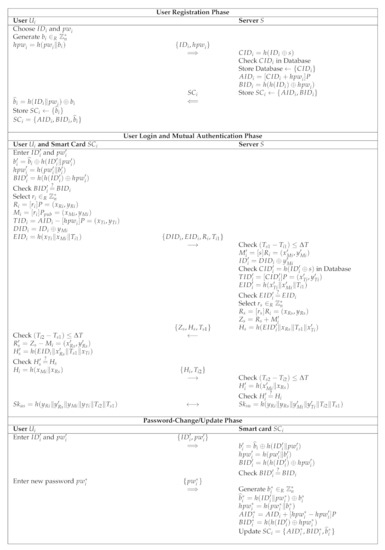

For the computational cost analysis, the approximate running time is based on the performance evaluation by Kilinc and Yanik [41] using the PBC Library [42]. The running times of arithmetic and cryptographic operations were measured using the experimental platform, which is the Ubuntu 12.04.1 LTS 32bit operating system with Intel Pentium Dual CPU E2200 2.20 GHz processor and 2048 MB of RAM. Based on their findings, the order of the time complexity for the elliptic curve point multiplication operation (), elliptic curve point addition operation (), symmetric encryption/decryption operation (), and hash operation () is stated as . The estimated running times for , , , and are 2.226 ms, 0.0288 ms, 0.0046 ms, and 0.00023 ms, respectively. The modular multiplication/division operation () and the bitwise XOR (⊕) operation recorded negligible running times and are hence ignored.

The computational cost is the total time complexity of operations executed in the user registration, user login, and mutual authentication phases. As shown in Table 5, the proposed scheme requires the computational cost of 7 + 3 + 18 and a running time of approximately 15.710 ms. In terms of the number of operations executed, the proposed scheme maintains 7 operations as in Huang et al. [30] and Chaudhry et al. [32], which is four operations less than Maitra et al. [31]. The running times for Qu and Tan [29], Huang et al. [30], Maitra et al. [31], Chaudhry et al. [32], and Mehmood et al. [33] are approximately 20.215 ms, 15.767 ms, 24.521 ms, 15.708 ms, and 9.003 ms, respectively. As seen in Figure 4a, the proposed scheme requires only a 0.02 ms higher running time than Chaudhry et al. [32]. This slight increase in running time is insignificant given that the proposed scheme is more secure than Chaudhry et al. [32] based on Table 4. Furthermore, the proposed scheme’s running time is 8.811 ms less than that of Maitra et al. [31], which is noteworthy considering that both schemes attain the same security goals.

Table 5.

Computational cost for executed operations in the proposed scheme and other similar schemes.

Figure 4.

Comparisons of ECC-based schemes’ performance in terms of (a) running time; (b) smart card storage cost; (c) message transmission cost.

For the smart card storage and message transmission costs analysis, the following assumptions are made. The sizes for the identity , password , and random numbers are 160 bits each. The hash function outputs are 256 bits, assuming the use of the SHA-256 [2] algorithm. The elliptic curve points are 512 bits each, whereas the x/y-coordinate is 256 bits. The timestamps are 128 bits.

In the proposed scheme, the parameters are stored in the smart card . The storage cost required for the smart card is bits, which is the highest among other schemes as shown in Figure 4b. The proposed scheme’s storage cost incurs 96 more bits than schemes by [29,30,32,33] since the parameter is stored as a hash output to mask the random number . Furthermore, the proposed scheme requires a 296-bit higher storage cost than the scheme by Maitra et al. [31] because the parameter is stored as an elliptic curve point instead of a hash output. Nevertheless, the proposed scheme’s higher storage cost is justified given that the proposed scheme provides better security features than other schemes.

The message transmission cost is the total bit size of the messages , , and , which are exchanged during the user login phase and mutual authentication phase. For the proposed scheme, the transmission cost is bits, which is comparable to that of Maitra et al. [31] and 128 bits lower than [29,30]. However, the proposed scheme’s transmission cost is 384 bits and 512 bits higher than Chaudhry et al. [32] and Mehmood et al. [33], respectively. Note that the proposed scheme and Maitra et al. [31] require clock synchronization, unlike other schemes. Hence, the transmission of timestamps during the login and authentication phases explains the message transmission cost being higher than [32,33], as shown in Figure 4c. Even with timestamps, the proposed scheme and Maitra et al. [31] managed to keep their transmission cost lower than [29,30].

Overall, the computational cost and running time of the proposed scheme are lower than [29,30,31]. In terms of the message transmission cost, the proposed scheme performs the same as Maitra et al. [31]. As the proposed scheme maintains all of the hard problems (ECDLP, ECCDHP, and ECFP) of Qu and Tan [29] and attains all of the security goals of Maitra et al. [31] as shown in Table 5, the higher smart card storage cost is an acceptable trade-off. In conclusion, the proposed scheme is better than all considered schemes.

6. Applications

In the future, it is suggested to investigate the applicability of adopting the three hard problems, i.e., ECDLP, ECCDHP, and ECFP, in developing user/client identification and authentication cryptographic schemes in distributed computer networks [43,44,45]. The integration of distributed computer networks with physical and social systems has evolved tremendously to many applications in cyber–physical systems and cyber–physical social systems. These systems connect many low-powered devices, such as smart mobile applications and wireless sensor nodes, that are deployed in unsupervised environments. The communication and data sharing between the physical components and cyber components demand attention toward security requirements and privacy issues [46,47]. ECC is favored in many public-key-based cryptographic schemes due to its efficiency; hence, it is important to study the feasibility of implementing three hard problems (ECDLP, ECCDHP, and ECFP) in designing secure and efficient schemes.

7. Conclusions

This study highlighted several drawbacks of the scheme by Chaudry et al. The aim of this study was to propose an ECC-based two-factor remote authentication scheme with a session key agreement based on Chaudhry et al.’s scheme to solve these drawbacks. The proposed scheme is provably secure under the ROM using the formal definitions of ECDLP, ECCDHP, and ECFP. Based on the security and performance analyses with other previous schemes, the proposed scheme offers better security attributes and is more efficient in terms of the computational cost and running time. Future work is suggested to build better identification and authentication schemes based on the same hard problems (ECDLP, ECCDHP, and ECFP) for applications in cyber–physical systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.S.I.; methodology, F.S.; validation, E.S.I.; formal analysis, F.S.; writing—original draft preparation, F.S.; writing—review and editing, E.S.I.; visualization, F.S.; supervision, E.S.I.; funding acquisition, E.S.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by UKM grant number GUP-2020-029.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors deeply appreciate all of the comments and suggestions from the anonymous reviewers and the editor for improving the paper. The authors would like to thank Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Universiti Teknologi MARA Malaysia, and the Ministry of Higher Education, Malaysia, for providing the facilities and financial support to conduct this research. Sincere thanks to Alena Lee Sanusi and Aziana Ismail for taking the time to proofread our paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lamport, L. Password authentication with insecure communication. Commun. ACM 1981, 24, 770–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIST. FIPS 180-4 Secure Hash Standard (SHS); Technical Report; National Institute of Standard and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.M.; Zhang, W.F.; Zhang, J.S.; Khan, M.K. Cryptanalysis and improvement on two efficient remote user authentication scheme using smart cards. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 2007, 29, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, S.A.; Farash, M.S.; Naqvi, H.; Kumari, S.; Khan, M.K. An enhanced privacy preserving remote user authentication scheme with provable security. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2015, 8, 3782–3795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhusudhan, R.; Hegde, M. Cryptanalysis and improvement of remote user authentication scheme using smart card. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Computer and Communication Engineering (ICCCE), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 26–27 July 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 84–89. [Google Scholar]

- Rivest, R.L.; Shamir, A.; Adleman, L. A method for obtaining digital signatures and public-key cryptosystems. Commun. ACM 1978, 21, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diffie, W.; Hellman, M. New directions in cryptography. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1976, 22, 644–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, V.S. Use of elliptic curves in cryptography. In Proceedings of the Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptographic Techniques, Linz, Austria, 9–11 April 1985; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 417–426. [Google Scholar]

- Koblitz, N. Elliptic curve cryptosystems. Math. Comput. 1987, 48, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gura, N.; Patel, A.; Wander, A.; Eberle, H.; Shantz, S.C. Comparing elliptic curve cryptography and RSA on 8-bit CPUs. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems, Cambridge, MA, USA, 11–13 August 2004; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 119–132. [Google Scholar]

- Juang, W.S.; Chen, S.T.; Liaw, H.T. Robust and efficient password-authenticated key agreement using smart cards. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2008, 55, 2551–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.I.; Chan, Y.C.; Zhang, Z.K. Robust remote authentication scheme with smart cards. Comput. Secur. 2005, 24, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.Z.; Huai, J.P.; Sun, J.Z.; Li, J.X.; Zhang, J.W.; Feng, Z.Y. Improvements of Juang et al.’s password-authenticated key agreement scheme using smart cards. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2009, 56, 2284–2291. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Qiu, W.; Zheng, D.; Chen, K.; Li, J. Anonymity enhancement on robust and efficient password-authenticated key agreement using smart cards. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2010, 57, 793–800. [Google Scholar]

- He, D.; Chen, J.; Hu, J. Further improvement of Juang et al.’s password-authenticated key agreement scheme using smart cards. Kuwait J. Sci. Eng. 2011, 38, 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Y. A simple and robust anonymous two-factor authenticated key exchange protocol. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2013, 6, 711–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Ma, J.; Li, G.; Yang, L. Robust two-factor authentication and key agreement preserving user privacy. Int. J. Netw. Secur. 2014, 16, 229–240. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Ma, C.G. An efficient and provable secure PAKE scheme with robust anonymity. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Computing and Applications, Chengde, China, 14–16 September 2012; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 722–729. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, J.L.; Lo, N.W.; Wu, T.C. Novel anonymous authentication scheme using smart cards. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2012, 9, 2004–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, J.W. On the secure design of hash-based authenticator in the smartcard authentication system. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2019, 109, 2329–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.C.; Juang, W.S.; Lei, C.L. Robust authentication and key agreement scheme preserving the privacy of secret key. Comput. Commun. 2011, 34, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhu, Y.; Pu, Q. Robust smart-cards-based user authentication scheme with user anonymity. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2012, 5, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.C.; Lin, I.C.; Wu, C.C. A multipurpose key agreement scheme in ubiquitous computing environments. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2015, 2015, 934716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wang, L. Analysis and enhancement of a password authentication and update scheme based on elliptic curve cryptography. J. Appl. Math. 2014, 2014, 247836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.H.; Biswas, G. Design of improved password authentication and update scheme based on elliptic curve cryptography. Math. Comput. Model. 2013, 57, 2703–2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odelu, V.; Das, A.K.; Goswami, A. An efficient ECC-based privacy-preserving client authentication protocol with key agreement using smart card. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2015, 21, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhusudhan, R.; Hegde, M.; Memon, I. A secure and enhanced elliptic curve cryptography-based dynamic authentication scheme using smart card. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 2018, 31, e3701. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari, A.; Jangirala, S.; Abbasi, M.Y.; Kumar, V.; Alam, M. ESEAP: ECC based secure and efficient mutual authentication protocol using smart card. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2020, 51, 102443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Tan, X.L. Two-factor user authentication with key agreement scheme based on elliptic curve cryptosystem. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2014, 2014, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Khan, M.K.; Wu, L.; Muhaya, F.T.B.; He, D. An efficient remote user authentication with key agreement scheme using elliptic curve cryptography. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2015, 85, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitra, T.; Obaidat, M.S.; Islam, S.H.; Giri, D.; Amin, R. Security analysis and design of an efficient ECC-based two-factor password authentication scheme. Secur. Commun. Networks 2016, 9, 4166–4181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, S.A.; Naqvi, H.; Mahmood, K.; Ahmad, H.F.; Khan, M.K. An improved remote user authentication scheme using elliptic curve cryptography. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2017, 96, 5355–5373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, Z.; Chen, G.; Li, J.; Albeshri, A. An untraceable ECC-based remote user authentication scheme. KSII Trans. Internet Inf. Syst. (TIIS) 2017, 11, 1742–1760. [Google Scholar]

- Dolev, D.; Yao, A. On the security of public key protocols. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1983, 29, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocher, P.; Jaffe, J.; Jun, B. Differential power analysis. In Proceedings of the Annual International Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 15–19 August 1999; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; pp. 388–397. [Google Scholar]

- Messerges, T.S.; Dabbish, E.A.; Sloan, R.H. Examining smart-card security under the threat of power analysis attacks. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2002, 51, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, S.K.; Sarje, A.K.; Singh, K. Cryptanalysis of password authentication schemes: Current status and key issues. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on Methods and Models in Computer Science (ICM2CS), New Delhi, India, 14–15 December 2009; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F.; Xu, L.; Kumari, S.; Li, X.; Alelaiwi, A. A new authenticated key agreement scheme based on smart cards providing user anonymity with formal proof. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2015, 8, 3847–3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, M.; Abadi, M.; Needham, R.M. A logic of authentication. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Math. Phys. Sci. 1989, 426, 233–271. [Google Scholar]

- Sowjanya, K.; Dasgupta, M.; Ray, S. An elliptic curve cryptography based enhanced anonymous authentication protocol for wearable health monitoring systems. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2020, 19, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilinc, H.H.; Yanik, T. A survey of SIP authentication and key agreement schemes. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2013, 16, 1005–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, B. The Pairing-Based Cryptography (PBC) Library. Available online: https://crypto.stanford.edu/pbc/ (accessed on 30 September 2022).

- Tsai, J.L. Weaknesses and improvement of Hsu-Chuang’s user identification scheme. Inf. Technol. Control 2010, 39, 48–50. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.C.; Lee, C.Y. A secure single sign-on mechanism for distributed computer networks. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2011, 59, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.C.; Liu, C.L.; Horng, G. Cryptanalysis of some user identification schemes for distributed computer networks. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 2014, 27, 2909–2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffar, Z.; Ahmed, S.; Mahmood, K.; Islam, S.H.; Hassan, M.M.; Fortino, G. An improved authentication scheme for remote data access and sharing over cloud storage in cyber-physical-social-systems. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 47144–47160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, D.; Obaidat, M.S.; Vijayakumar, P. Edge-assisted intelligent device authentication in cyber-physical systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).