Abstract

AES is the most widely used secret-key cryptosystem in industry, and determining the security of AES is a central problem in cryptanalysis. The mixture differential property proposed in Eurocrypt 2017 is an essential property to setup state-of-the-art key recovery attacks on some round-reduced versions of AES. In this paper, we exploit mixture differential properties that are automatically deduced from a mixed integer linear programming (MILP)-based model to extend key recovery attacks on AES. Specifically, we modify the MILP model toolkit to produce all mixture trails explicitly and test a 5-round secret-key mixture differential distinguisher on small-scale AES experimentally. Moreover, we utilize this distinguisher to do a key recovery attack on 6-round AES-128 that outperforms previous work in the same fashion. We also for the first time utilize a 6-round AES secret-key distinguisher to set up a key recovery attack on 7-round AES-192. This work is a new yet simple cryptanalysis on AES by exploiting mixture differential properties.

MSC:

94A60

1. Introduction

Block ciphers, as a category of private key cryptographic algorithms, are the workhorse of cryptography for ensuring confidentiality due to their high efficiency compared with public key cryptographic algorithms. The security of cryptographic algorithms is analyzed from both theoretical and practical points of view. Analysis from the theoretical point of view is referred to as cryptanalysis, where an attacker can only access plaintexts and ciphertexts of the target algorithm. Cryptanalysis aims to find out flaws in the cipher design, which can give a more accurate security evaluation of the target cipher. In this paper, we focus on cryptanalysis of the most widely used standard block cipher, AES [1], to try to find out special statistic properties reflected only in plaintexts and ciphertexts to recover the secret key from a theoretical point of view. In addition to theoretical cryptanalysis, analysis from a practical point of view (e.g., differential power analysis [2] or differential fault analysis [3]) analyzes the security of the implementation of the target cipher, which is beyond the scope of this paper.

A key recovery attack on AES comes in two steps: (1) finding out the property that can make a distinguisher and (2) designing the key recovery attack algorithm based on the found distinguisher to recover the secret key. Distinguishing a block cipher under a secret key from a random permutation is a devastating violation of security. Technically, the distinguishers are properties that hold on (even reduced round) block ciphers with a probability significantly different from that for random permutations. After a distinguisher is found, the divide-and-conquer framework can be used to setup a key recovery attack. However, the key recovery procedure is not always so obvious because the data/time/memory complexities of the whole process will probably exceed the complexities of brute-force methods that are standard measures to compare against. The state-of-the-art key recovery attacks on AES exploit a variety of statistical properties that can be used as a distinguisher, including the mixture differential properties revealed in [4] by an automatic searching method. Whether this kind of distinguisher can be used to setup key recovery attacks on AES remains unclear. In this paper, we answer this question by providing effective key recovery attacks based on the mixture differential distinguishers.

1.1. Related Work

A variety of properties of AES have been investigated to do key recovery attacks. The collision attack [5] revealed that there exist collisions between some partial byte-oriented functions induced by the AES structure, and thus a 4-round distinguisher can be constructed that in turn enables attacks on 7-round AES with any key length. Differential cryptanalysis [6] provides the basic concepts of many cryptanalysis methods, including the impossible differential cryptanalysis [7]. As for key recovery attacks on AES, the impossible differential cryptanalysis [8] put a 4-round impossible differential distinguisher in the middle to launch a 6-round key recovery attack. Meet-in-the-Middle (MITM) attack [9] utilized the 4-round property that, for a special plaintext set called -set, the number of possible values for one byte in the ciphertext set after four-round encryption is very limited. With additional techniques such as data/time/memory trade-off and differential enumeration, key recovery attack complexities for 6-round AES-128 and up to 8-round AES-192 and AES-256 are modified from that in a previous MITM attack [10]. The Square attack was presented in the design of AES [11], and shows that for a -set of plaintexts, the XOR sum of the intermediate states after three rounds of encryption is equal to zero. A “partial sum” technique has been introduced [12], which substantially reduces the work factor of the dedicated Square attack. The “partial sum” method in the Square attack can be improved by analyzing more information per -set [13], and thus the time complexity can be significantly reduced.

In Eurocrypt 2017, Grassi et al. [14] discovered the first secret-key distinguisher for 5-round AES. In FSE/ToSC 2019, this property is further refined as “mixture-differential cryptanalysis” [15]. The main idea is, given that the 4-round ciphertexts from a chosen plaintext pair lie in a particular subspace, the probability is 1 that a specially constructed pair has the same property, while this is not the case for the random permutation. This 4-round property is modified to 5-round and a 6-round key recovery attack is launched by prepending one round before the distinguisher [16]. Note that this is the first time that a 5-round distinguisher can be used to set up key recovery attacks. The mixture differential property was used by Bar-On et al. [17,18] to launch key-recovery attacks on up to 7-round AES-192 and -256 with practical data and memory complexities. Meanwhile, the record for a 5-round key recovery attack, which cost encryption/decryption [19], is also highly related to such mixture differential structures.

The mixture differential property has been investigated from diverse perspectives to extend to more block ciphers [20] and to setup distinguishers with more rounds [16]. However, all these properties are deduced by scrutinizing structures of AES-like constructions manually. Not until recently has a Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP)-based method been proposed to search for mixture differential properties automatically [4]. With this method, given a description of an aligned block cipher, whether in SPN or Feistel structure, finding the mixture differential distinguishers is converted to an MILP problem that can be solved by off-the-shelf constraint programming problem solvers (e.g., Gurobi [21]), which is the paradigm for the automatic symmetric-key cryptanalysis that has been gaining popularity in recent years [22,23,24,25,26,27]. The automatically deduced mixture differential distinguishers for AES cover up to 6 rounds and have been used to perform distinguishing attacks. However, no key recovery attacks have been provided based on distinguishers on AES. Furthermore, no previous work has ever directly applied a 6-round distinguisher to perform key recovery attacks.

1.2. Our Contribution

In this paper, we answer the question of whether the automatically deduced mixture differential distinguishers can be used to do key recovery attacks. The contributions are summarized below.

- We verify the 5-round mixture differential distinguisher deduced from the MILP method experimentally on small-scale AES practically. With lookup-table-based implementation, the verification efficiency is improved about 20 times. Compared with the textbook implementation, the verification time with 5-round encryption is decreased from more than 20 min to about 1 min when running on 32 parallel threads with an AMD Ryzen Threadripper 3970X Processor. We also refined the MILP-based automatic tool for searching for mixture differential distinguishers to illustrate all trails to form the distinguisher.

- In the key recovery aspect, we give a 6-round key recovery attack on AES-128 by directly exploiting the automatically deduced 5-round secret key distinguisher with data/time complexity reduced to . The previous best attack in the same fashion was by Grassi [16], with data/time/memory complexity being . Our methods present a dramatic decrease in data and time complexity with the same memory complexity.

- Further, a novel 7-round key recovery attack on AES-192 that directly exploits a 6-round secret-key distinguisher is also presented. Though this attack has higher complexity than some previous ones, this is the first direct utilization of a 6-round secret-key distinguisher to do key recovery attacks on 7-round AES with complexity lower than a brute-force attack.

All our source codes are provided in the repository https://github.com/qiaokexin/mixture-differential-for-AES.git (accessed on 10 October 2022).

This paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, after a short description of AES, we introduce metrics for evaluating cryptanalysis methods and mixture differential distinguishers. In Section 3, we rewrite the automatic mixture differential searching model and verify the 5-round distinguisher on small-scale AES practically and also illustrate the 6-round mixture characteristics concretely for verification. In Section 4, key recovery attacks on 6-round AES-128 and 7-round AES-192 are given. The paper is summarized in Section 5.

2. Preliminary

We inherit some notations from [4,18].

2.1. A Brief Description of AES

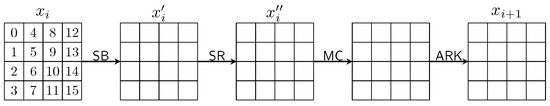

AES [1] block cipher takes in a 128-bit block organized as a matrix on and a 128-, 192- or 256-bit master key. Denote the three versions by AES-128, AES-192 and AES-256 respectively. The number of rounds for AES-128, AES-192 and AES-256 are 10, 12 and 14, respectively. The key schedules for generating subkeys in each round for the three versions are different in detail but follow the same framework. The encryption operations in each round for all versions are identical. The input state is denoted by . After XORing a whiten key , the state iterates on round functions 10, 12 and 14 times, respectively. The whitening key is the first 128 bits of the master key. The state before the i-th round is denoted by . In the i-th round, the state goes through the following four steps (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

AES round function.

- SubBytes (): each byte of is substituted by another byte according to an invertible 8-bit to get state . The substitution is determined by a table called Sbox, which is a permutation of 8-bit elements. The Sbox and inverse Sbox are given in Appendix A. An inverse Sbox is used in decryption, and this step is denoted by InvSubBytes.

- ShiftRows (): the j-th () row of state is cyclicly shifted by j bytes to the left to get state . Cyclic shifting to the right with the same offsets is applied in decryption, and this step is denoted by InvShiftRows.

- MixColumn (): multiply each column of by a MDS (maximum distance separable) matrix over . The MDS matrix and its inverse arewhere each element in the matrix is an element in defined by the irreducible polynomial , and multiplication and addition are also performed in this field. Multiplication of on each column is performed in decryption, and this step is denoted by InvMixColumn. The MDS property ensures that the number of non-zero bytes among the input column and output column is no less than 5, except for the all-zero case, i.e., the branch number being 5.

- AddRoundKey (): XORing a 128-bit subkey to the state to get .

Note that in the last round, operation is omitted, and this is also the case for reduced versions in this paper. The key schedule algorithm processes the master key to generate the whiten key and all subkeys. As our attack does not utilize relations among subkeys, we do not show the key schedule here.

The indexes of each byte in a state are in column first order. Use to denote the bytes of state indicated by I, where I can be a single index or a set of indexes. Use to denote the j-th column of the state and for multi-columns. We are interested in diagonals of states, denoted by , and also inversive diagonals, denoted by , where J is a column index or consists of several column indexes. Use to denote the difference on specific state x. We use to denote four states in a quadruple.

A straightforward decryption of AES is done by using the inverses of the steps InvSubBytes, InvShiftRows, InvMixColumns and AddRoundKey and reversing their order. However, an equivalent algorithm for decryption that performs InvSubBytes–InvShiftRows–InvMixColumns–AddRoundKey in each round and omits InvMixColumns in the last round has been anticipated in the AES design. So we can have a decryption algorithm that has the same structure as the encryption, with a change in the key schedule in that we need to apply the InvMixColumns operation to the round keys in the middle rounds. Considering that the distinguishers used in our key recovery attacks are independent of the details of the Sbox and the MixColumn matrix, we can get an equivalent distinguisher on the decryption direction by shifting the patterns on diagonal positions to the anti-diagonal positions due to the shift row differentiations. Therefore, our key recovery attack can be applicable to both encryption and decryption with the same complexities.

AES block cipher by itself is only suitable for encryption or decryption of one block, say a 128-bit string. When processing messages longer than a block, a mode of operation is needed to repeatedly apply AES. Common modes of operation include ECB, CBC, CFB, OFB, CTR, etc. As cryptanalyses on modes of operation are beyond the scope of this work, we do not present them in detail.

2.2. Metrics of Evaluation of Cryptanalysis Methods

Cryptanalysis tries to find non-randomness in the cipher design that can be reflected from plaintexts and ciphertexts without any side-channel information from the execution. Key recovery attacks are the most threatening cryptanalysis method. Technically, the key recovery procedure is a divide-and-conquer process. By appending or prepending extra rounds to the distinguisher, partial key bits involved in the added rounds can be recovered by utilizing the distinguisher property. Then, the non-involved key bits are exhaustively searched. The cost of a key recovery attack is estimated with respect to the following aspects: data complexity, time complexity and memory complexity. Data complexity is measured by the number of queries of encryption oracle by the attacker. Time complexity is measured by the computational cost executed by the attacker offline. The unit is usually the cost of one execution of the encryption algorithm. Memory complexity is the memory required to launch the attack. An effective key recovery attack should have complexities lower than those of a brute-force attack, which is the standard measure to compare against. A brute-force attack has data/time/memory complexity of (by enumerating all keys) or (by lookup from a precomputed table), where n is the number of key bits. More basics of cryptanalysis on block ciphers can be found in ([28], Chap. 4). The goal of cryptanalysts is to reduce the complexities of the attack, and one cryptanalysis method outperforms another if its complexity is lower.

2.3. Mixture Differentials

Mixture differential property reflects the byte-wise equality relation among a quadruple of states. There are a total of 15 sorted combinations of four bytes up to pair-wise equality:

where different letters indicate different values. We call them quadruple patterns. If the four bytes consist of two same pairs, we call this quadruple a mixture ([18], Def. 1). Quadruple patterns of mixtures include the following cases:

- copy pattern , which means the second pair is a copy of the first pair. This pattern is denoted by “c” and shown graphically as

.

. - exchange pattern , which means the second pair is acquired by exchange of the two values in the first pair. This pattern is denoted by “e” and shown graphically as

.

. - shift pattern , which means the second pair is acquired by shifting an inactive pair, denoted by “s” and shown graphically as

.

. - inactive pattern , which consists of four equal bytes. This pattern is denoted by “-” and shown graphically as

.

.

Other quadruple patterns are denoted by “∗” and shown graphically as  . Throughout this paper, mixture patterns or mixture differential patterns include these five quadruple patterns. Probability for a random quadruple to have a “c”, “e” or “s” pattern is , and probability to have an inactive pattern is , where w is width of the word.

. Throughout this paper, mixture patterns or mixture differential patterns include these five quadruple patterns. Probability for a random quadruple to have a “c”, “e” or “s” pattern is , and probability to have an inactive pattern is , where w is width of the word.

. Throughout this paper, mixture patterns or mixture differential patterns include these five quadruple patterns. Probability for a random quadruple to have a “c”, “e” or “s” pattern is , and probability to have an inactive pattern is , where w is width of the word.

. Throughout this paper, mixture patterns or mixture differential patterns include these five quadruple patterns. Probability for a random quadruple to have a “c”, “e” or “s” pattern is , and probability to have an inactive pattern is , where w is width of the word.For aligned block ciphers, the quadruple/mixture patterns on each byte (or nibble for nibble-wise block ciphers) constitute the quadruple/mixture pattern of the full state. In the iterative cryptographic primitives, certain mixture patterns can be deduced with some probability through the iteration. The mixture patterns for states in each round constitute a pattern trail. With fixed input and output mixture patterns, probability on all trails with significantly high probability can be summed up to make a mixture differential distinguisher with higher probability, which resembles the differential hull for classical differential cryptanalysis. If the probability is higher than that of a random permutation, this property can potentially be used for distinguishing attacks or key recovery attacks. We refine the formal definition and proposition for mixture differentials from [4].

Definition 1

((Refined) Mixture Differential). A mixture differential is a pair of quadruple patterns such that given plaintext quadruples conforming , the ciphertext quadruples conform with probability p.

We have the following proposition

Proposition 1.

To distinguish an aligned cryptographic permutation from a random one by mixture differentials defined in Definition 1, it is required that for cryptographic permutation, significantly, where w is the width of the word for the cryptographic permutation, and are the number of word-wise “-”, “”, “” and “” mixture patterns in the output pattern.

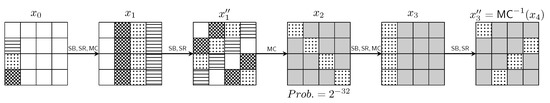

Figure 2 shows a mixture trail on 4-round AES with probability that is utilized in Bar-On et al.’s work [17,18] (they actually consider a cluster of similar distinguishers). Note that for a random permutation, the probability of having the output mixture pattern given the input mixture pattern is .

Figure 2.

A 4-round AES mixture differential trail with probability . ( layer omitted as it does not influence pattern propagation).

3. Mixture Differential Distinguishers

Though mixture differential cryptanalysis has attracted a lot of attention since its proposed, it was not until recently that it was investigated by using an automatic tool to search for such distinguishers. In [4], an MILP-based automatic tool is developed to search for mixture distinguishers.

3.1. Search for Mixture Differential Distinguishers with MILP Model

The framework of the MILP model firstly uses binary variables to represent the equality between any two states among a quadruple; thus, the mixture pattern is encoded to a 6-bit string for each byte. Then, the mixture patterns propagate through each layer with probabilities that are also encoded as binary strings. The mixture pattern variables and probability variables affect each other by satisfying some linear inequalities. Noting that second-order property—whether the first pair difference equals the second pair difference on a byte—influences the probability of getting a certain mixture pattern; second-order equalities on each byte are also encoded to binary variables, and with some auxiliary variables, the effect on probability is expressed by linear inequalities as well. All 0-1 variables used in the model are summarized as follows.

- , mixture pattern encoding variables for the s-th byte in the input state to the r-th round, i.e., . We have iff .

- , column-wise mixture pattern encoding variables for the t-th input column for operation in the r-th round. Note that an input column to layer is a diagonal of the input state, i.e., . We have iff .

- , probability encoding variables. By considering the first-order differential property, the probability to have some mixture pattern on is . For example, for a random input quadruple, the probability of an output byte conforming a “”, “” or “” pattern is , and it is for a “-” pattern.

- together with . The former indicates whether the second-order differential is 0 for , i.e., iff . The latter describes that the assignment of holds with probability . If the s-th is active for both the first pair and the second pair in the quadruple, with probability () we have , or we have with probability 1 (). If the s-th is inactive for both pairs, with probability 1 (). If the s-th is inactive for only one pair, we have with probability 1 ().

- , indicates whether second-order differential is 0 on . We have .

- , a dummy variable used as a label. We have .

- , number of activity variables reduced considering second-order differential properties. The probability of the mixture pattern trail covering R rounds is estimated as .

Now we are ready to impose constraints on these variables. The pseudo-code of how the MILP model is built is shown in Algorithm 1, and we refer the readers to [4] for the detailed mechanism of how the inequality templates are generated. For completeness and to enable the readers to reproduce the distinguishers (once produced, deduced distinguishers are easy to be verified experimentally or theoretically, as will be shown later), details of how linear inequalities concerning certain variables are generated by templates are provided in Appendix B. Note that the input pattern and output pattern can be left null and additional variables and constraints need to be added to describe how many activity variables are consumed to have an output pattern for random permutations, which is used as a threshold. By imposing that the objective function is smaller than the threshold, we get an optimization model to deduce input and output patterns to form a distinguisher.

With this model, by solving an optimization problem, the largest probability together with input and output mixture patterns are deduced. Furthermore, given the input and output mixture patterns, by solving an enumeration problem, one can enumerate all mixture pattern trails with the same high probability and sum up the probabilities to estimate the true probability of making a distinguisher.

Two distinguishers are impressive, which we will use in key recovery attacks. Table 1 shows the input and output pattern of the distinguishers, the probability for one trail, the number of trails with the same probability and the total probabilities on AES and on a random permutation. The input mixture patterns of the two distinguishers are the same, which are “inactive” patterns on , “copy” patterns on and “exchange” patterns on . Define this pattern to be . The 5-round distinguisher has “shift” patterns on . Denote it by . The probability to have after 5 full rounds and of AES is , while it is for random permutations. The 6-round distinguisher has “shift”-type mixture patterns on . Denote it by . The probability to have after 6 full round and of AES is , while it is for random permutations. Source codes for generating these two distinguishers are provided in the repository.

Table 1.

Mixture distinguishers covering 5- and 6-round AES.

| Algorithm 1 MILP model to get the probability of given mixture patterns |

|

3.2. Verification of 5-Round Distinguishers

It is worth noting that the single 5-round mixture trail does not make a distinguisher, as it has the same probability as that of random permutations. Thus, to show the validity of the mixture differential distinguisher as a hull of mixture trails, we tested the validity of the 5-round distinguisher on the small-scale AES [29], which has the same structure as standard AES but with a 4-bit . As the probability of the distinguisher is not relevant to the size of and details of matrix but reflects how the structure allows for trails with a certain number of active Sboxes to hold, the verification on small scale AES is strong evidence for the distinguisher to hold on standard AES. The small scale AES is implemented in a lookup-table-based implementation [11] that resembles the AES implementation in many cryptographic libraries such as OpenSSL [30]. Four precomputed tables are generated by applying for all possible input nibbles such that each table consists of sixteen 16-bit values. The cost of each round is 16 table lookups and XORing of the table elements and round keys.

The Sbox used in the small-scale AES is in Table 2.

Table 2.

The Sbox for the small-scale AES.

The operations in the i-th round can be expressed as

where the matrix elements are elements in defined by the primitive polynomial . The lookup-table-based implementation calculates one column by looking up four tables and adding the results as well as the corresponding subkey column. For the first column,

The four precomputed tables are the compositions of the dot multiplication by the column elements and the Sbox operation, i.e.,

The input to the tables is 4-bit string and the output is 16-bit. So each table is a list with sixteen 16-bit elements. The four tables are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Lookup tables for the small-scale AES.

Then, can be calculated by

with 16 table lookup operations.

This implementation is faster than the textbook implementation where each operation is implemented by its definition, as used in [16]. We verified the 5-round distinguisher on both this lookup-table-based implementation and the implementation provided in [16]. The expected probability for the 5-round distinguisher to hold on small scale AES is . We test on 200 randomly generated master keys and use a 20-round version to simulate a random permutation. For each randomly generated master key, quadruples conforming input patterns are randomly generated. On average, the number of quadruples whose ciphertexts confirm the output pattern are 3.885 and 0.215 for 5-round small-scale AES and 20-round small-scale AES, respectively; thus, the probability of right quadruples is for 5-round small scale AES and for the 20-round version. This result verifies that the accumulated truncated mixture differential trails can make a distinguisher. The verification codes are included in our repository. The average running time with the textbook implementation is about 20 min, while it is about 1 min with a lookup-table-based implementation when run on an AMD Ryzen Threadripper 3970X Processor.

3.3. Illustration of 6-Round Distinguishers

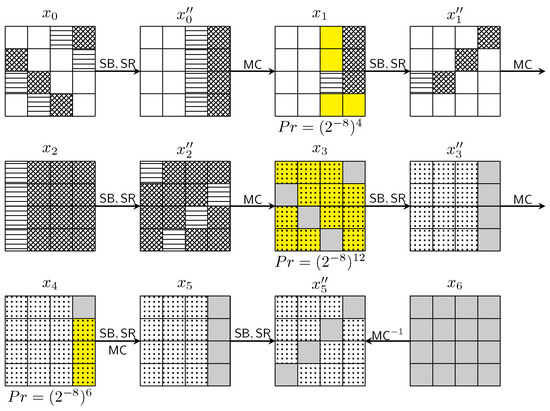

Regarding 6-round distinguishers, the probability is too low to be verified experimentally even on a small variant of AES. Therefore, we demonstrate the mixture pattern trails of the 6-round distinguishers. Figure 3 shows one trail with probability . The probability lies on the layer to make specific mixture patterns in states and , marked in yellow. The deduced patterns reflect equality among quadruples. It is worth noting that for state and state , the differences of the first pair and the second pair are the same, so after the layer conditioned on that one pair has zero difference on specific bytes, the other pair has the same difference with probability 1. This is where the mixture differential distinguisher gains an advantage. However, after one more round of confusion, this property does not hold anymore, and probability is calculated independently on two pairs, as is the case for to .

Figure 3.

A 6-round AES mixture differential trail with probability .

There are a total of 56 trails with probability with the same input and output pattern as in Figure 3. All trails are shown in abbreviated form in Table A4 in Appendix C.

4. Key Recovery Attacks

We utilize the 6-round mixture differential distinguisher with probability to do a key recovery attack on 7-round AES-192 and use a 5-round distinguisher with probability to do cryptanalysis on 6-round AES-128, all by appending one round after the distinguisher. As we do not prepend rounds before the distinguisher, we can acquire N quadruples conforming trivially and concentrate on the guess-and-determine procedure on the ciphertext side.

4.1. Key Recovery on 6-Round AES-128

Suppose the plaintext quadruples in conform , with probability that the mixture pattern is in position , i.e., the differences of both the first pair and second pair are zero on the first inversed diagonal. These conditions are used as filters to filter out wrong guesses of . To use the MITM technique to reduce complexity, express the filter conditions by combinations of through operation. Specifically, the filter conditions and corresponding key byte that needs to be guessed to deduce the target difference are

The four filter bytes together with four involved bytes for each are called four groups. In the key recovery procedure, initialize four counters of size for each group. To get right quadruple, we prepare quadruples conforming the input pattern. Then,

- For each quadruple, do the MITM procedure on four groups:

- (a)

- For the first group, guess , compute the value on both the first pair and the second pair, and store the current guess in a hash table T indexed by this 16-bit value. After this step, each item of T contains on average one element.

- (b)

- Guess and compute the value on both the first pair and the second pair. Look up the table T by this 16-bit value and get the candidate for the combination . Increase the counter for the first group. After this step, on average, candidates are suggested.

- (c)

- Repeat Step 1(a)–(b) for the other three groups.

- To have h-bit advantage of key exhaustive search on each group, combine the top candidates suggested by each counter to get candidates of the full 128-bit key . Check with plaintext–ciphertext pairs.

Time and memory complexity. The memory complexity of the attack is counters, and the hash table is sized , which are negligible. For each quadruple, the first MITM step takes times lookups and hash table lookups. The second step has about the same cost. If each round of AES is estimated as 20 times lookups and each hash table lookup is estimated as one AES round, the time complexity for each group in Step 1 is 5-round AES encryptions. The total time complexity of the attack is .

Success probability and data complexity. Step 1 of the attack goes on each group independently, so we only need to know whether the 32-bit right key will appear in the top positions for each group with high probability. Each quadruple recommends candidates on average. Each right quadruple hits the right key once and hits the wrong keys times. Each wrong quadruple hits the right key and wrong keys indiscriminately a total of times. The right key is hit about times, and each wrong key is, on average, hit times. Thus, the signal/noise ratio, i.e., the ratio of the counter of the right key and the average counter of a wrong key, is . We estimate the success probability by the formula [31], where is the cumulative distribution function of the standard normal distribution. By setting and , the success probability is above 99% and the time complexity is .

To have right quadruples, we need to build up quadruples conforming input pattern . We fix 90 bits of plaintexts and enumerate the remaining 38 bits. Among the 90 fixed bits, 64 are located in . Choose six bytes from and fix 3-bit in each of these six bytes, and fix 4-bit in each of the remaining 2bytes. We could build quadruples, which is enough for the attack. The data complexity is no larger than .

4.2. Key Recovery on 7-Round AES-192

The key recovery attack on 7-round AES-192 is quite similar to the previous one on 6-round AES-128, considering that they both append one round after a distinguisher and the distinguishers have the same input pattern. But there are more filter conditions on the output of the 6-round distinguisher. The filters can be divided into four groups, each involving four bytes in . We show the guess-and-filter procedure in the first group, and the other three groups proceed in the same fashion.

In the first group, the filters are and , holding on to both the first pair and the second pair. Equivalently, can be expressed by through the layer. In the key recovery procedure, to apply the MITM technique, write the filter conditions in the first group as

Initialize four counters of size for each group. Suppose we have prepared plaintext quadruples conforming to expect right quadruples. Then:

- For each quadruple, do the MITM procedure on four groups:

- (a)

- For the first group, guess , compute the value on both the first pair and the second pair, and store the current guess in a hash table T indexed by this 16-bit value. After this step, each item of T contains, on average, one element.

- (b)

- Guess and compute the value on both the first pair and the second pair. Look up the table T by this 16-bit value and get the candidate for the combination . Test if the last two equations in Equation (6) are satisfied under this candidate on both the first pair and the second pair. This test is a filter with probability . If so, increase the counter; otherwise, discard the key candidate.

- (c)

- Repeat Step 1(a–b) for the other three groups.

- To have h-bit advantage of key exhaustive search on each group, combine the top candidates indicated by each counter to form full 128-bit key and combine with the other 64-bit keys that are independent of . Check the candidate keys with plaintext–ciphertext pairs.

Time and memory complexity. The memory complexity of the attack is counters, and it has a hash table of size , which are negligible. For each quadruple, the first MITM step takes times lookups and hash table lookups. Step 1(b) takes an additional 16 lookups in each guess of . The complexity of Step 1 is estimated as 6-round AES encryptions. The total time complexity of the attack is .

Success probability and data complexity. Each quadruple only suggests 32-bit keys for each group on average. Each right quadruple will hit the right 32-bit key once. The wrong quadruples will hit all keys indiscriminately. Thus, the right key will be hit about times. The wrong key will be hit times on average. The signal/noise ratio is no smaller than . By setting , the success probability is about 69.95% with time complexity .

To build up plaintext quadruples conforming the input pattern, we build structures such that in each structure, 64-bits of are fixed and the other bits are enumerated. Each structure can provide quadruples conforming the input pattern; therefore, structures are needed. The data complexity of the attack is .

The comparison of our work and previous ones is shown in Table 4. Key recovery attacks are estimated from the data/time/memory complexities. From Table 4, it is obvious that for the 6-round key recovery attack on AES-128, our method outperforms the impossible differential attack [8], MITM attack [9] and the original mixture differential attack [17]. Especially considering the number of rounds of distinguishers used, denoted by in the table, our result is the best one by utilizing a 5-round distinguisher to launch key recovery attacks. For 7-round AES-192, our result is the first one to setup a key recovery attack with a 6-round distinguisher.

Table 4.

Comparison of attacks on 6- and 7-round AES. ( is the number of rounds of the distinguisher exploited to set up the attack. Our results are highlighted in bold).

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we exploited the secret-key mixture differential properties on round-reduced AES deduced from MILP models to present key recovery attacks on 6-round AES-128 and 7-round AES-192 by appending one round after the distinguishers. The complexity of our 6-round AES-128 key recovery attack with a 5-round distinguisher outperforms the previous one of the same fashion, as the data/time/memory complexities are significantly reduced from to . Further, this is the first time that a 7-round key recovery attack has been possible by utilizing a 6-round distinguisher directly. Moreover, in the distinguisher verification part, the implementation of the small-scale AES used in our experiments is about 20 times more efficient than the previous one.

Future work can include finding out more properties to make a distinguisher on block ciphers as well as designing key recovery attacks with reduced data/time/memory complexity. For the AES block cipher, the current mixture differential property is byte-oriented. That is to say, the details of the Sbox and the mix column matrix are not taken into account when searching for the mixture differential properties. Methods to search for properties with higher probability on AES or that that can cover more rounds remain to be investigated. In the key recovery aspects, the current method is independent of the key schedule. There may exist useful relations among subkeys to further reduce the complexity of the key recovery attack. The key schedule effect will be taken into consideration in future work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.Q.; methodology, K.Q.; software, J.C.; validation, J.C.; formal analysis, K.Q.; investigation, K.Q.; resources, J.C.; data curation, K.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, C.O.; writing—review and editing, J.C.; supervision, C.O.; project administration, C.O.; funding acquisition, K.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Beijing Institute of Technology Research Fund Program for Young Scholars grant number XSQD-202024003, National Natural Science Foundation of China grant number 62102025, Beijing Natural Science Foundation grant number 4222035, and the Open Research Fund of Key Laboratory of Cryptography of Zhejiang Province grant number ZCL21018.

Data Availability Statement

Codes repository (accessed on 10 October 2022): https://github.com/qiaokexin/mixture-differential-for-AES.git.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MILP | Mixed Integer Linear Programming |

| MITM | Meet-in-the-Middle |

| SubBytes | |

| ShiftRows | |

| MixColumn |

Appendix A. AES Encryption Parameters

The Sbox and the inverse Sbox used in the AES block cipher are shown in Table A1 and Table A2, respectively. The i-th element in the table (count in row-first order) is the output for input i. All elements are in hex form.

Table A1.

Sbox in the AES block cipher.

Table A1.

Sbox in the AES block cipher.

| 00 | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07 | 08 | 09 | 0a | 0b | 0c | 0d | 0e | 0f | |

| 00 | 63 | 7c | 77 | 7b | f2 | 6b | 6f | c5 | 30 | 01 | 67 | 2b | fe | d7 | ab | 76 |

| 10 | ca | 82 | c9 | 7d | fa | 59 | 47 | f0 | ad | d4 | a2 | af | 9c | a4 | 72 | c0 |

| 20 | b7 | fd | 93 | 26 | 36 | 3f | f7 | cc | 34 | a5 | e5 | f1 | 71 | d8 | 31 | 15 |

| 30 | 04 | c7 | 23 | c3 | 18 | 96 | 05 | 9a | 07 | 12 | 80 | e2 | eb | 27 | b2 | 75 |

| 40 | 09 | 83 | 2c | 1a | 1b | 6e | 5a | a0 | 52 | 3b | d6 | b3 | 29 | e3 | 2f | 84 |

| 50 | 53 | d1 | 00 | ed | 20 | fc | b1 | 5b | 6a | cb | be | 39 | 4a | 4c | 58 | cf |

| 60 | d0 | ef | aa | fb | 43 | 4d | 33 | 85 | 45 | f9 | 02 | 7f | 50 | 3c | 9f | a8 |

| 70 | 51 | a3 | 40 | 8f | 92 | 9d | 38 | f5 | bc | b6 | da | 21 | 10 | ff | f3 | d2 |

| 80 | cd | 0c | 13 | ec | 5f | 97 | 44 | 17 | c4 | a7 | 7e | 3d | 64 | 5d | 19 | 73 |

| 90 | 60 | 81 | 4f | dc | 22 | 2a | 90 | 88 | 46 | ee | b8 | 14 | de | 5e | 0b | db |

| a0 | e0 | 32 | 3a | 0a | 49 | 06 | 24 | 5c | c2 | d3 | ac | 62 | 91 | 95 | e4 | 79 |

| b0 | e7 | c8 | 37 | 6d | 8d | d5 | 4e | a9 | 6c | 56 | f4 | ea | 65 | 7a | ae | 08 |

| c0 | ba | 78 | 25 | 2e | 1c | a6 | b4 | c6 | e8 | dd | 74 | 1f | 4b | bd | 8b | 8a |

| d0 | 70 | 3e | b5 | 66 | 48 | 03 | f6 | 0e | 61 | 35 | 57 | b9 | 86 | c1 | 1d | 9e |

| e0 | e1 | f8 | 98 | 11 | 69 | d9 | 8e | 94 | 9b | 1e | 87 | e9 | ce | 55 | 28 | df |

| f0 | 8c | a1 | 89 | 0d | bf | e6 | 42 | 68 | 41 | 99 | 2d | 0f | b0 | 54 | bb | 16 |

Table A2.

Inverse Sbox in the AES block cipher.

Table A2.

Inverse Sbox in the AES block cipher.

| 00 | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07 | 08 | 09 | 0a | 0b | 0c | 0d | 0e | 0f | |

| 00 | 52 | 09 | 6a | d5 | 30 | 36 | a5 | 38 | bf | 40 | a3 | 9e | 81 | f3 | d7 | fb |

| 10 | 7c | e3 | 39 | 82 | 9b | 2f | ff | 87 | 34 | 8e | 43 | 44 | c4 | de | e9 | cb |

| 20 | 54 | 7b | 94 | 32 | a6 | c2 | 23 | 3d | ee | 4c | 95 | 0b | 42 | fa | c3 | 4e |

| 30 | 08 | 2e | a1 | 66 | 28 | d9 | 24 | b2 | 76 | 5b | a2 | 49 | 6d | 8b | d1 | 25 |

| 40 | 72 | f8 | f6 | 64 | 86 | 68 | 98 | 16 | d4 | a4 | 5c | cc | 5d | 65 | b6 | 92 |

| 50 | 6c | 70 | 48 | 50 | fd | ed | b9 | da | 5e | 15 | 46 | 57 | a7 | 8d | 9d | 84 |

| 60 | 90 | d8 | ab | 00 | 8c | bc | d3 | 0a | f7 | e4 | 58 | 05 | b8 | b3 | 45 | 06 |

| 70 | d0 | 2c | 1e | 8f | ca | 3f | 0f | 02 | c1 | af | bd | 03 | 01 | 13 | 8a | 6b |

| 80 | 3a | 91 | 11 | 41 | 4f | 67 | dc | ea | 97 | f2 | cf | ce | f0 | b4 | e6 | 73 |

| 90 | 96 | ac | 74 | 22 | e7 | ad | 35 | 85 | e2 | f9 | 37 | e8 | 1c | 75 | df | 6e |

| a0 | 47 | f1 | 1a | 71 | 1d | 29 | c5 | 89 | 6f | b7 | 62 | 0e | aa | 18 | be | 1b |

| b0 | fc | 56 | 3e | 4b | c6 | d2 | 79 | 20 | 9a | db | c0 | fe | 78 | cd | 5a | f4 |

| c0 | 1f | dd | a8 | 33 | 88 | 07 | c7 | 31 | b1 | 12 | 10 | 59 | 27 | 80 | ec | 5f |

| d0 | 60 | 51 | 7f | a9 | 19 | b5 | 4a | 0d | 2d | e5 | 7a | 9f | 93 | c9 | 9c | ef |

| e0 | a0 | e0 | 3b | 4d | ae | 2a | f5 | b0 | c8 | eb | bb | 3c | 83 | 53 | 99 | 61 |

| f0 | 17 | 2b | 04 | 7e | ba | 77 | d6 | 26 | e1 | 69 | 14 | 63 | 55 | 21 | 0c | 7d |

Appendix B. Inequality Templates Used in MILP Model

There are six inequality templates in the MILP model to search for the mixture differential distinguishers, as is shown in Table A3. The template for generating inequalities concerning i variables consists of vectors of length . Each vector represents one inequality. Formally, vector represents inequality .

Table A3.

Inequality templates used in the MILP model to search for mixture differential distinguishers.

Table A3.

Inequality templates used in the MILP model to search for mixture differential distinguishers.

| No. | Inequalities |

|---|---|

| Template 1 | (0, 0, 0, 1, −1, 1, 0), (1, 1, 0, −1, 0, 0, 0), (0, 0, 0, 1, 1, −1, 0), (−1, −1, 1, −1, 1, 1, 1), (1, −1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0), (−1, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0), (1, 1, 1, −1, −1, −1, 1), (1, 0, −1, 0, 1, 0, 0), (0, 1, −1, 0, 0, 1, 0), (0, −1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0), (−1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0) |

| Template 2 | (1, 1, 1, 1, 1, −4, 1, 1, 0), (1, 1, 1, 1, −4, 1, 1, 1, 0), (1, −4, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0), (1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, −4, 0), (1, 1, 1, −4, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0), (−4, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0), (1, 1, −4, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0), (1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, −4, 1, 0) |

| Template 3 | (1, 2, 3, 3, 1, 2, −2, −1, −3, −1, −2, −1, −5, −3, 0), (8, −14, −14, 4, 4, −10, −6, 6, 6, −1, −1, 7, 16, 6, 14), (−4, 0, 4, −2, 2, −2, 4, −1, −3, 2, −2, 3, 6, 4, 0), (−10, −14, 4, −14, 4, 8, 7, 6, −1, 6, −1, −6, 16, 6, 14), (−14, 8, −14, 4, −10, 4, 6, −6, 6, −1, 7, −1, 16, 6, 14), (4, −6, 4, 8, 4, −8, −2, 4, −6, −5, −1, 5, 0, 4, 2), (−2, −4, 2, 0, −2, 4, 2, 4, −2, −1, 3, −3, 6, 4, 0), (2, 4, −2, −2, 4, 6, −1, −1, 0, 0, −1, −3, −6, −4, 0), (4, 2, −2, −4, 0, −2, −3, −2, 3, 4, −1, 2, 6, 4, 0), (4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, −1, −1, −2, −3, −4, −4, −14, −10, 0), (−2, 4, 4, 2, 4, −2, −2, −3, 1, −2, 0, 1, −6, −2, 0), (4, −2, 4, 4, −2, 2, 1, −2, −3, 0, 1, −2, −6, −2, 0), (0, 0, 0, −2, −2, −2, 1, 1, −2, 1, 2, 2, 4, 2, 2), (−4, −3, −2, −4, −3, −2, −1, 3, 3, 2, 3, −1, 6, 2, 10), (−2, −2, −2, −2, −2, −2, 2, 0, 2, 1, −1, 1, 3, 2, 7) |

| Template 4 | (1, −1, 1, 1, −1, 1, −1, −2, 0), (−1, 1, 1, 1, 1, −1, −1, −2, 0), (1, 1, −1, −1, 1, 1, −1, −2, 0), (1, 1, 1, −1, −1, −1, 1, 0, 0), (1, −1, −1, 1, 1, −1, 1, 0, 0), (−1, 1, −1, 1, −1, 1, 1, 0, 0), (−1, −1, 1, −1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0), (0, 0, −1, 0, −1, −1, 1, 1, 2) |

| Template 5 | (1, 1, −1, −1, 1, −1, 1, 1, 0), (0, 0, 1, 1, 0, −1, 0, 0, 0), (0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, −1, 0), (0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, −1, 1, 0), (0, 0, 0, 1, −1, 0, 0, 1, 0), (0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, −1, 0, 0), (1, 1, 1, −1, −1, 1, 1, −1, 0), (0, 0, −1, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0), (0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, −1, 0), (0, 0, −1, −1, 1, −1, 1, 1, 1), (0, 0, 1, −1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0), (0, 0, 1, 0, −1, 0, 1, 0, 0), (1, 1, 1, 1, 1, −1, −1, −1, 0) |

| Template 6 | (0, −1, 0, 0, −1, 1), (0, 0, 1, 0, −1, 0), (1, 1, −1, 0, 1, 0), (−1, 0, 0, 0, −1, 1) |

Appendix C. Mixture Differential Trails of 6-Round AES

There are 56 mixture differential trails for 6-round AES, each with probability . All the trails are shown in Table A4. In each trail, each state pattern consists of sixteen byte patterns in column-first order. State patterns for and to are the same as those in Figure 3, so we omit them.

Table A4.

Mixture differential trails with probability for 6-round AES ( and to patterns are the same as those in Figure 3. The signs “−", “c", “x", “s" and “*" represent the inactive, copy, exchange, shift and other quadruple patterns respectively).

Table A4.

Mixture differential trails with probability for 6-round AES ( and to patterns are the same as those in Figure 3. The signs “−", “c", “x", “s" and “*" represent the inactive, copy, exchange, shift and other quadruple patterns respectively).

| No. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | ---- ---- --c- xxx- | cccc xxxx xxxx xxxx | s*ss ss*s sss* *sss | ssss ssss ssss *sss |

| 1 | ---- ---- c-c- x-x- | cccc xxxx cccc xxxx | s*ss ss*s sss* *sss | ssss ssss ssss *sss |

| 2 | ---- ---- -c-c -x-x | xxxx cccc xxxx cccc | sss* *sss s*ss ss*s | ssss ss*s ssss ssss |

| 3 | ---- ---- ---c -xxx | xxxx xxxx xxxx cccc | s*ss ss*s sss* *sss | ssss ssss ssss *sss |

| 4 | ---- ---- c--- x-xx | xxxx xxxx cccc xxxx | s*ss ss*s sss* *sss | ssss ssss ssss *sss |

| 5 | ---- ---- --cc -xx- | cccc xxxx xxxx cccc | s*ss ss*s sss* *sss | ssss ssss ssss *sss |

| 6 | ---- ---- -c-c -x-x | xxxx cccc xxxx cccc | s*ss ss*s sss* *sss | ssss ssss ssss *sss |

| 7 | ---- ---- -c-- xx-x | xxxx cccc xxxx xxxx | s*ss ss*s sss* *sss | ssss ssss ssss *sss |

| 8 | ---- ---- cc-c ---x | xxxx cccc cccc cccc | s*ss ss*s sss* *sss | ssss ssss ssss *sss |

| 9 | ---- ---- cc-- x--x | xxxx cccc cccc xxxx | s*ss ss*s sss* *sss | ssss ssss ssss *sss |

| 10 | ---- ---- c-cc --x- | cccc xxxx cccc cccc | s*ss ss*s sss* *sss | ssss ssss ssss *sss |

| 11 | ---- ---- -ccc -x-- | cccc cccc xxxx cccc | s*ss ss*s sss* *sss | ssss ssss ssss *sss |

| 12 | ---- ---- -cc- xx-- | cccc cccc xxxx xxxx | s*ss ss*s sss* *sss | ssss ssss ssss *sss |

| 13 | ---- ---- ccc- x--- | cccc cccc cccc xxxx | s*ss ss*s sss* *sss | ssss ssss ssss *sss |

| 14 | ---- ---- c-cc --x- | cccc xxxx cccc cccc | *sss s*ss ss*s sss* | s*ss ssss ssss ssss |

| 15 | ---- ---- ---c -xxx | xxxx xxxx xxxx cccc | *sss s*ss ss*s sss* | s*ss ssss ssss ssss |

| 16 | ---- ---- cc-c ---x | xxxx cccc cccc cccc | *sss s*ss ss*s sss* | s*ss ssss ssss ssss |

| 17 | ---- ---- --cc -xx- | cccc xxxx xxxx cccc | *sss s*ss ss*s sss* | s*ss ssss ssss ssss |

| 18 | ---- ---- -c-c -x-x | xxxx cccc xxxx cccc | *sss s*ss ss*s sss* | s*ss ssss ssss ssss |

| 19 | ---- ---- -ccc -x-- | cccc cccc xxxx cccc | *sss s*ss ss*s sss* | s*ss ssss ssss ssss |

| 20 | ---- ---- c--c --xx | xxxx xxxx cccc cccc | s*ss ss*s sss* *sss | ssss ssss ssss *sss |

| 21 | ---- ---- c--c --xx | xxxx xxxx cccc cccc | sss* *sss s*ss ss*s | ssss ss*s ssss ssss |

| 22 | ---- ---- c--- x-xx | xxxx xxxx cccc xxxx | sss* *sss s*ss ss*s | ssss ss*s ssss ssss |

| 23 | ---- ---- cc-c ---x | xxxx cccc cccc cccc | sss* *sss s*ss ss*s | ssss ss*s ssss ssss |

| 24 | ---- ---- ccc- x--- | cccc cccc cccc xxxx | sss* *sss s*ss ss*s | ssss ss*s ssss ssss |

| 25 | ---- ---- ---c -xxx | xxxx xxxx xxxx cccc | sss* *sss s*ss ss*s | ssss ss*s ssss ssss |

| 26 | ---- ---- c-cc --x- | cccc xxxx cccc cccc | sss* *sss s*ss ss*s | ssss ss*s ssss ssss |

| 27 | ---- ---- -ccc -x-- | cccc cccc xxxx cccc | sss* *sss s*ss ss*s | ssss ss*s ssss ssss |

| 28 | ---- ---- c--c --xx | xxxx xxxx cccc cccc | *sss s*ss ss*s sss* | s*ss ssss ssss ssss |

| 29 | ---- ---- c--c --xx | xxxx xxxx cccc cccc | ss*s sss* *sss s*ss | ssss ssss sss* ssss |

| 30 | ---- ---- c-c- x-x- | cccc xxxx cccc xxxx | sss* *sss s*ss ss*s | ssss ss*s ssss ssss |

| 31 | ---- ---- --cc -xx- | cccc xxxx xxxx cccc | sss* *sss s*ss ss*s | ssss ss*s ssss ssss |

| 32 | ---- ---- -c-- xx-x | xxxx cccc xxxx xxxx | sss* *sss s*ss ss*s | ssss ss*s ssss ssss |

| 33 | ---- ---- c--- x-xx | xxxx xxxx cccc xxxx | *sss s*ss ss*s sss* | s*ss ssss ssss ssss |

| 34 | ---- ---- c-c- x-x- | cccc xxxx cccc xxxx | *sss s*ss ss*s sss* | s*ss ssss ssss ssss |

| 35 | ---- ---- cc-- x--x | xxxx cccc cccc xxxx | *sss s*ss ss*s sss* | s*ss ssss ssss ssss |

| 36 | ---- ---- --c- xxx- | cccc xxxx xxxx xxxx | sss* *sss s*ss ss*s | ssss ss*s ssss ssss |

| 37 | ---- ---- cc-- x--x | xxxx cccc cccc xxxx | sss* *sss s*ss ss*s | ssss ss*s ssss ssss |

| 38 | ---- ---- -cc- xx-- | cccc cccc xxxx xxxx | sss* *sss s*ss ss*s | ssss ss*s ssss ssss |

| 39 | ---- ---- --c- xxx- | cccc xxxx xxxx xxxx | *sss s*ss ss*s sss* | s*ss ssss ssss ssss |

| 40 | ---- ---- -c-- xx-x | xxxx cccc xxxx xxxx | *sss s*ss ss*s sss* | s*ss ssss ssss ssss |

| 41 | ---- ---- ccc- x--- | cccc cccc cccc xxxx | *sss s*ss ss*s sss* | s*ss ssss ssss ssss |

| 42 | ---- ---- -cc- xx-- | cccc cccc xxxx xxxx | *sss s*ss ss*s sss* | s*ss ssss ssss ssss |

| 43 | ---- ---- cc-c ---x | xxxx cccc cccc cccc | ss*s sss* *sss s*ss | ssss ssss sss* ssss |

| 44 | ---- ---- cc-- x--x | xxxx cccc cccc xxxx | ss*s sss* *sss s*ss | ssss ssss sss* ssss |

| 45 | ---- ---- c-cc --x- | cccc xxxx cccc cccc | ss*s sss* *sss s*ss | ssss ssss sss* ssss |

| 46 | ---- ---- c-c- x-x- | cccc xxxx cccc xxxx | ss*s sss* *sss s*ss | ssss ssss sss* ssss |

| 47 | ---- ---- ccc- x--- | cccc cccc cccc xxxx | ss*s sss* *sss s*ss | ssss ssss sss* ssss |

| 48 | ---- ---- ---c -xxx | xxxx xxxx xxxx cccc | ss*s sss* *sss s*ss | ssss ssss sss* ssss |

| 49 | ---- ---- --cc -xx- | cccc xxxx xxxx cccc | ss*s sss* *sss s*ss | ssss ssss sss* ssss |

| 50 | ---- ---- c--- x-xx | xxxx xxxx cccc xxxx | ss*s sss* *sss s*ss | ssss ssss sss* ssss |

| 51 | ---- ---- -ccc -x-- | cccc cccc xxxx cccc | ss*s sss* *sss s*ss | ssss ssss sss* ssss |

| 52 | ---- ---- -cc- xx-- | cccc cccc xxxx xxxx | ss*s sss* *sss s*ss | ssss ssss sss* ssss |

| 53 | ---- ---- -c-c -x-x | xxxx cccc xxxx cccc | ss*s sss* *sss s*ss | ssss ssss sss* ssss |

| 54 | ---- ---- -c-- xx-x | xxxx cccc xxxx xxxx | ss*s sss* *sss s*ss | ssss ssss sss* ssss |

| 55 | ---- ---- --c- xxx- | cccc xxxx xxxx xxxx | ss*s sss* *sss s*ss | ssss ssss sss* ssss |

References

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. FIPS PUB 197: Advanced Encryption Standard (AES). pub-NIST; 2001. Available online: http://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/FIPS/NIST.FIPS.197.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Kocher, P.; Jaffe, J.; Jun, B. Differential Power Analysis. In Advances in Cryptology — CRYPTO’ 99. CRYPTO 1999; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; pp. 388–397. [Google Scholar]

- Biham, E.; Shamir, A. Differential Fault Analysis of Secret Key Cryptosystems. In Advances in Cryptology — CRYPTO ’97. CRYPTO 1997; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997; pp. 513–525. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, K.; Sun, S.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, A.; Zhu, L. Quadruple Differential Distinguishers and an Automatic Searching Tool. TechRxiv Preprint. 2022. Available online: https://www.techrxiv.org/articles/preprint/Quadruple_Differential_Distinguishers_and_an_Automatic_Searching_Tool/21186376 (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Gilbert, H.; Minier, M. A Collision Attack on 7 Rounds of Rijndael. In Proceedings of the AES Candidate Conference, New York, NY, USA, 13–14 April 2000; Volume 2000, pp. 230–241. [Google Scholar]

- Biham, E.; Shamir, A. Differential Cryptanalysis of DES-like Cryptosystems. J. Cryptol. 1991, 4, 3–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biham, E.; Biryukov, A.; Shamir, A. Cryptanalysis of Skipjack Reduced to 31 Rounds Using Impossible Differentials. In Advances in Cryptology–EUROCRYPT 1999; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; pp. 12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Cheon, J.H.; Kim, M.; Kim, K.; Jung-Yeun, L.; Kang, S. Improved Impossible Differential Cryptanalysis of Rijndael and Crypton. In Information Security and Cryptology — ICISC 2001. ICISC 2001; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; pp. 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Derbez, P.; Fouque, P.A. Exhausting Demirci-Selçuk Meet-in-the-Middle Attacks against Reduced-round AES. In Fast Software Encryption. FSE 2013; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 541–560. [Google Scholar]

- Derbez, P.; Fouque, P.A.; Jean, J. Improved Key Recovery Attacks on Reduced-round AES in the Single-key Setting. In Advances in Cryptology – EUROCRYPT 2013. EUROCRYPT 2013; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 371–387. [Google Scholar]

- Daemen, J.; Rijmen, V. The Design of Rijndael: AES-the Advanced Encryption Standard; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, N.; Kelsey, J.; Lucks, S.; Schneier, B.; Stay, M.; Wagner, D.; Whiting, D. Improved Cryptanalysis of Rijndael. In Fast Software Encryption. FSE 2000; Goos, G., Hartmanis, J., van Leeuwen, J., Schneier, B., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; pp. 213–230. [Google Scholar]

- Tunstall, M. Improved “Partial Sums”-based Square Attack on AES. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Security and Cryptography-SECRYPT 2012, Rome, Italy, 24–27 July 2012; SciTePress: Setúbal, Portugal, 2012; pp. 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Grassi, L.; Rechberger, C.; Rønjom, S. A New Structural-Differential Property of 5-Round AES. In Advances in Cryptology – EUROCRYPT 2017. EUROCRYPT 2017; Coron, J.S., Nielsen, J.B., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 289–317. [Google Scholar]

- Grassi, L. Mixture Differential Cryptanalysis: A New Approach to Distinguishers and Attacks on round-reduced AES. IACR Trans. Symmetric Cryptol. 2018, 2018, 133–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, L. Probabilistic Mixture Differential Cryptanalysis on Round-reduced AES. In Selected Areas in Cryptography – SAC 2019. SAC 2019; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 53–84. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-On, A.; Dunkelman, O.; Keller, N.; Ronen, E.; Shamir, A. Improved Key Recovery Attacks on Reduced-Round AES with Practical Data and Memory Complexities. In Advances in Cryptology–CRYPTO 2018; Shacham, H., Boldyreva, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 185–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-On, A.; Dunkelman, O.; Keller, N.; Ronen, E.; Shamir, A. Improved Key Recovery Attacks on Reduced-round AES with Practical Data and Memory Complexities. J. Cryptol. 2020, 33, 1003–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkelman, O.; Keller, N.; Ronen, E.; Shamir, A. The Retracing Boomerang Attack. In Advances in Cryptology—EUROCRYPT 2020; Canteaut, A., Ishai, Y., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 280–309. [Google Scholar]

- Boura, C.; Canteaut, A.; Coggia, D. A General Proof Framework for Recent AES Distinguishers. IACR Trans. Symmetric Cryptol. 2019, 2019, 170–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurobi Optimization, LLC. Gurobi Optimizer Reference Manual. 2022. Available online: https://www.gurobi.com (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Sun, S.; Hu, L.; Wang, P.; Qiao, K.; Ma, X.; Song, L. Automatic Security Evaluation and (Related-key) Differential Characteristic Search: Application to SIMON, PRESENT, LBlock, DES (L) and Other Bit-oriented Block Ciphers. In Advances in Cryptology–ASIACRYPT 2014; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 158–178. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; Gerault, D.; Lafourcade, P.; Yang, Q.; Todo, Y.; Qiao, K.; Hu, L. Analysis of AES, SKINNY, and Others with Constraint Programming. IACR Trans. Symmetric Cryptol. 2017, 2017, 281–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Bao, Z.; Lin, D. Applying MILP Method to Searching Integral Distinguishers Based on Division Property for 6 Lightweight Block Ciphers. In Advances in Cryptology—ASIACRYPT 2016; Cheon, J.H., Takagi, T., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 648–678. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, D.; Sun, S.; Derbez, P.; Todo, Y.; Sun, B.; Hu, L. Programming the Demirci-Selçuk Meet-in-the-Middle Attack with Constraints. In Advances in Cryptology—ASIACRYPT 2018; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, X.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, S.; Wei, C.; Wang, X.; Hu, L. Automatic Classical and Quantum Rebound Attacks on AES-Like Hashing by Exploiting Related-Key Differentials. In Advances in Cryptology—ASIACRYPT 2021; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 241–271. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, Z.; Dong, X.; Guo, J.; Li, Z.; Shi, D.; Sun, S.; Wang, X. Automatic Search of Meet-in-the-Middle Preimage Attacks on AES-like Hashing. In Advances in Cryptology – EUROCRYPT 2021; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 771–804. [Google Scholar]

- Sakiyama, K.; Sasaki, Y.; Li, Y. Security of Block Ciphers: From Algorithm Design to Hardware Implementation; John Wiley & Sons: Singapore Pte. Ltd, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cid, C.; Murphy, S.; Robshaw, M.J.B. Small Scale Variants of the AES. In Fast Software Encryption. FSE 2005; Gilbert, H., Handschuh, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 145–162. [Google Scholar]

- The OpenSSL Project. OpenSSL: The Open Source toolkit for SSL/TLS. Available online: https://www.openssl.org/ (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Selçuk, A.A. On Probability of Success in Linear and Differential Cryptanalysis. J. Cryptol. 2008, 21, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).