Abstract

Linear control systems are studied by means of a state-space approach. Feedback morphisms are presented as natural generalization of feedback equivalences. The set of feedback morphisms between two linear systems is a vector space. Kernels, cokernels, as well as monomorphisms, epimorphisms, sections, and retracts of feedback morphisms are studied in the category of linear systems over finite dimensional vector spaces. Finally, a classical Kalman’s decomposition of linear systems over vector spaces is presented as a split short exact sequence in the category.

MSC:

15A03; 93C05; 18E99

1. Introduction

Morphisms of linear (control) systems have been recently introduced [1] in order to study the structure of linear systems up to feedback actions. New feedback invariants were found [2] and thus classical results [3] were extended to a complete classification of regular linear systems over commutative rings R.

The purpose of this paper is to continue developing the theory of the feedback morphisms of linear systems. The kernels and cokernels of feedback morphisms are computed when they exist. The category of linear systems over a commutative ring R, together with feedback morphisms, is not abelian (note that contains R-Mod as a subcategory). The use of categories in the study of linear systems goes back at least to [4], where the authors proved the wildness of the feedback classification problem over arbitrary commutative rings.

In this paper, we focus on linear systems over finite dimensional vector spaces, that is to say, on the category , where denotes the field of scalars. Monomorphisms and epimorphisms are identified in the category of linear systems, as well as sections and retracts. The classical Kalman’s decomposition Theorem [5] is stated in terms of a kernel–cokernel split exact sequence of linear systems.

2. Some Preliminaries

Let be a field and V a finite dimensional -vector space. A linear system over is a triple , where is an endomorphism, and is a subspace (the subspace of controls).

Let and be linear systems over . A morphism of linear systems, or feedback morphism, between and is a linear map , such that [6]

Denote by the -vector space [1] of morphisms of linear systems between and . Note that is a subspace of .

The composition of feedback morphisms is defined as the composition of linear maps. It is routine to check that the composition of feedback morphisms is a feedback morphism. It is also straightforward to check that identities are morphisms of systems, as well as zero maps. Associative laws follow from the associative laws of composition of linear maps. Thus, denotes the category whose objects are linear systems over and whose morphisms are feedback morphisms.

Since all arrows in category are obtained from linear maps, and since identities in are obtained from identity linear maps, it follows that is an enriched category over the category -Vect of finite dimensional -vector spaces.

Note 1.

Functor -Vect sending on objects and on morphisms is obviously injective on morphisms. Hence, F is a faithful functor. Functor F is also dense because every vector space V is of the form .

Isomorphisms in the category are exactly the classical feedback equivalences (see [6] for details).

Some other categories of linear systems might be considered. Here are some examples.

Example 1

(Zero-controlled linear systems). Let be the full subcategory of gathering all linear systems on the form . Then, feedback morphisms a are linear maps commuting with f.

Example 2

(Full-controlled linear systems). Let be the subcategory of gathering all linear systems of the form . In this subcategory of , every linear map arises as a feedback morphism, that is to say . Functor sends and is faithful and dense. F is also full because the map is surjective, and in fact bijective. Therefore, F is, in this case, an equivalence of categories and -Vect.

Example 3

(Reachable linear systems). Let be a linear system. Consider the chain of vector subspaces of V given by , , , and in general . It is clear that , and, on the other side, if , then and the chain stabilizes forever. Since , there exists an s such that . Define the degree of system Σ, and write as the least integer s such that .

Linear system is called reachable if . Consider the full subcategory of , whose objects are the reachable linear systems. Brunovsky’s theorem [3] implies in particular that every reachable system is feedback isomorphic to a Brunovsky canonical form. Hence, the skeleton of is the full subcategory of gathering all Brunovsky’s canonical forms.

3. Kernels and Cokernels of Feedback Morphisms

Let be linear systems. Then, the set is a vector subspace of and hence an abelian group. Moreover, compositions are bilinear. That is to say, for objects and and the composition maps

are group homomorphisms.

On the other hand, system is the zero object in the category . Finite direct products of linear systems do exist in : just take . Hence, category (and also are additive categories.

In an additive category, it makes sense to search for kernels and cokernels of morphisms as well as natural (canonical) decompositions of morphisms.

Kernels and Cokernels

The next result is a classical characterization of kernels and cokernels.

Lemma 1.

Let be a feedback morphism.

kernels.Morphism defines the kernel of if and only if, for every , the following sequence of abelian groups is exact.

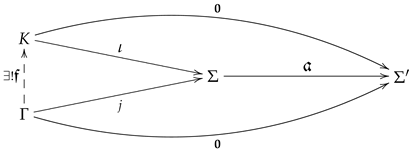

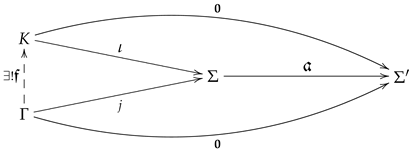

kernel diagram.Equivalently, morphism defines the kernel of if there exists a system K and a feedback morphism ι making the top triangle commutative, and for each linear system Γ and each morphism j making the bottom triangle commutative, there exists a unique feedback morphism making the left triangle commutative.

cokernels.Morphism defines the cokernel of if and only if, for every , the following sequence of abelian groups is exact.

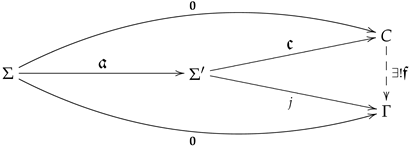

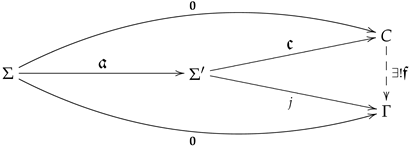

cokernel diagram.Equivalently, morphism defines the cokernel of if there exists a system C and a feedback morphism 𝔠 making the top triangle commutative, and for each linear system Γ and each morphism j making the bottom triangle commutative, there exists a unique feedback morphism making the right triangle commutative

In the following, the kernel (respectively, cokernel) of a feedback map in is denoted by (respectively, ) while (respectively, ) are often used, by abuse of notation, for the kernel (respectively, cokernel) of linear map in -Vect, where is the functor defined in the above Note 1.

Lemma 2.

Let be a feedback morphism. Assume that its kernel does exist in . Then, injects into (we often write ).

On the other hand, maps onto (we often write maps onto ).

Proof.

It is immediate because is the kernel of in -Vect and . The dual argument works for cokernels. □

Corollary 1.

Let be a feedback morphism.

(i) If is an injective map, then .

(ii) If is a surjective map, then .

Theorem 1.

Category has all cokernels.

Proof.

Let be a feedback morphism. Assume and . Set bases in V and so that the matrix of (as a linear map between vector spaces) is of the Hermite form. Obtain the block matrices associated with f and , as well as the basis of subspaces B and . Then, the above systems and morphism are transformed into:

where .

It is important to note here that, since is a feedback morphism, it follows that . Hence, one has that the image of block is contained in the image of block .

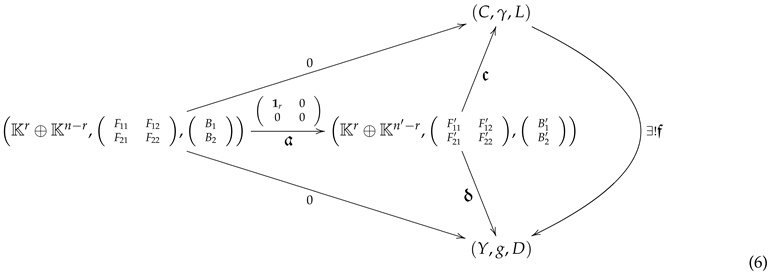

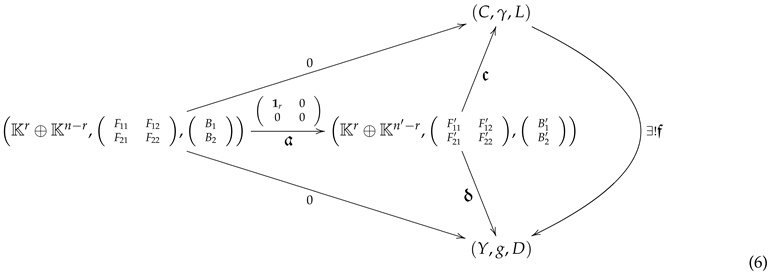

Consider the cokernel diagram:

A cokernel makes the upper triangle commutative and for all systems and morphism making the lower triangle commutative, there exists a unique feedback morphism making the right triangle commutative.

Define the linear system and linear map .

- (i)

- (ii)

Moreover, is a feedback morphism. On the other hand, it is clear that

- (iii)

Now, set any linear system and note that:

- (iv)

- A morphism must be on the block form in order to assure

- (v)

- and because is a feedback morphism

We claim that is the unique feedback morphism making the right triangle commutative.

- (vi)

- (by iv) yields

- (vii)

- by (v).

Hence, is a feedback morphism. It is quite clear that is the unique solution to equation , which is, in matrix form, □

Next, some sufficient conditions for the existence of kernels in the category of linear systems are given.

Theorem 2

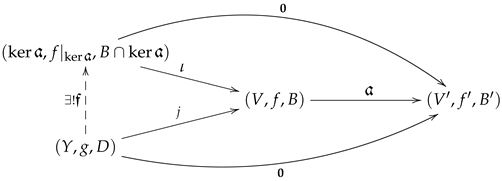

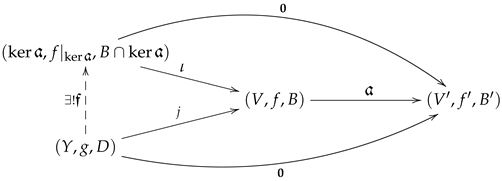

(Sufficient condition of kernels). Let be a feedback morphism. If the kernel of as linear map is f-invariant (i.e., ), then the natural inclusion defines a feedback morphism and

Proof.

Consider the kernel diagram

Then, is a well defined feedback morphism and it is unique, making the left triangle commutative □

Then, is a well defined feedback morphism and it is unique, making the left triangle commutative □

Then, is a well defined feedback morphism and it is unique, making the left triangle commutative □

Then, is a well defined feedback morphism and it is unique, making the left triangle commutative □Next, we give an example of the above condition of existence of kernels in :

Example 4.

Consider the linear systems over and given by

The linear map verifies the following properties:

is a feedback morphism because:

- (i)

- (ii)

Thus, is a feedback morphism. and . Then, the kernel is

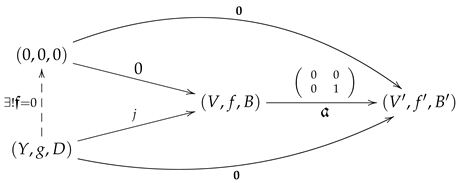

Note 2.

The above sufficient condition to the existence of kernels in is, in general, not necessary. The feedback map given by

verifies:

- (i)

- (trivial).

- (ii)

- is not f-invariant because

- (iii)

- However, the morphism has a kernel in . In fact, in because of any feedback morphism j in the below diagram

needs to be .

needs to be .

Note also that , while . That is to say, is in general not isomorphic to .

4. Feedback Morphisms, Monomorphisms, and Epimorphisms

A morphism is a monomorphism if for each object in and each , one has:

A morphism is an epimorphism if for each object in and each , one has:

Since is a faithful functor, then F reflects monomorphisms and epimorphisms ([7] 7.44, 7.46). That is to say:

- (i)

- If is a monomorphism in -Vect (i.e., injective), then is a monomorphism in .

- (ii)

- If is an epimorphism in -Vect (i.e., surjective), then is an epimorphism in .

Moreover, a stronger result holds in the case of epimorphisms.

Theorem 3.

Feedback morphism is an epimorphism in if and only if is surjective.

Proof.

We claim that for every pair of linear maps such that , it follows that .

However, this is clear from the fact that every arrow is in fact for the feedback morphism , because functor is dense. Therefore,

□

Note 3.

Not every monomorphism in is injective: the above Note 2 gives an example of a feedback monomorphism

that is not injective as linear map , but for every feedback morphism

the condition implies . Thence, condition implies and . Therefore, a is a feedback monomorphism, while is not monic.

Note 4.

Category is additive but not balanced, that is to say, monomorphism plus epimorphism does not yield isomorphism. The following minimal example applies on every field :

The linear map is the identity, thus a monomorphism and an epimorphism in -Vect. Hence,

is a monomorphism and an epimorphism in . However,

has no inverse in because . Therefore, is not an isomorphism.

Note 5.

A pointed category (a category with a zero object) is normal if every monomorphism is the kernel of some morphism. The category is said to be conormal if every epic is the cokernel of some morphism.

The example in Note 4 proves that is neither normal nor conormal because

is both monic and epic but neither a kernel nor a cokernel. To see this, just note that neither the identity morphism nor the identity factors through .

5. Sections, Retracts, and Feedback Decompositions

A morphism is a retract (denoted by if it has a right inverse, that is to say, if there exists a morphism such that

A morphism is a section (denoted by ) if it has a left inverse, that is to say, if there exists a morphism such that

Since every functor preserves sections and retracts ([7] 7.22, 7.28) the result follows.

Theorem 4.

If a feedback morphism

is a section (respectively, retract) in , then

is a section (respectively, retract) in -Vect.

Because one-side inverses of feedback morphisms need not be feedback morphisms, we have that the converse result of the above does not hold. That is to say, neither sections nor retracts are reflected by F.

Example 5.

A section in -Vect that is a feedback morphism but not a section in is the following one

Example 6.

An example of a retract in -Vect that is a feedback morphism but fails to be a retract in is the following: consider the linear systems over and given by

The linear map verifies the following properties:

is a feedback morphism because:

- (i)

- (ii)

Moreover, is an epimorphism in because it is a feedback morphism and an epimorphism in -Vect, and in fact a retract in -Vect because

- (iii)

However, since

- (iv)

- (see [1])

there is no right inverse of

and hence is not a retract in the category of systems .

6. Split Exact Sequences of Linear Systems

Definition 1

(cf. [8]). A kernel–cokernel pair in is a pair of feedback morphisms

where is the kernel of

and

is the cokernel of .

A kernel–cokernel pair where

is a section and

is a retract is called a split short exact sequence and denoted by

Theorem 5

(Kalman’s Decomposition). Let be a linear system in . Consider the sequence of vector subspaces of V given by and . Then, there exists an index such that:

- (i)

- (ii)

- The following is a split short exact sequence of linear systemswhere ι is the standard inclusion, and π is quotient modulo subspace .

Proof.

Statement is given in Example 3.

In order to prove , note that is f-invariant, i.e., . Set a basis of and complete it to a basis of V. In this basis, system is of the form

Then,

is a split short exact sequence of linear systems □

7. Conclusions

Some categorical properties of feedback morphisms of linear systems were introduced in order to study the additive category of linear systems. In particular, the classical Kalman’s decomposition theorem for linear systems over finite dimensional vector spaces was stated in these terms.

Some further developments of this approach should include the study of the subcategory of reachable systems, where there exists a classification theorem and hence the objects of category are in bijective correspondence with the integer partitions of [2]. The objective would be setting up an exact structure on the additive category such that Kalman’s decomposition is in fact an exact sequence. That exact structure should also reflect Brunovsky’s Theorem [3] as a factorization of reachable systems in the category .

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Carriegos, M.V. Morphisms of linear control systems. Open Math. 2022. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Carriegos, M.V. Enumeration of classes of linear systems via equations and via partitions in a ordered abelian monoid. Linear Algebra Its Appl. 2013, 438, 1132–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunovsky, P.A. A classification of linear controllable systems. Kibernetika 1970, 3, 173–188. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, J.W.; Klingler, L. On feedback invariants for linear dynamical systems. Linear Algebra Its Appl. 2001, 325, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kalman, R.E. Kronecker invariants and Feedback. In Ordinary Differential Equations; Academic: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1972; pp. 459–471. [Google Scholar]

- Carriegos, M.V.; Muñoz Castañeda, A.L. On the K-theory of feedback actions on linear systems. Linear Algebra Its Appl. 2014, 440, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adámek, J.; Herrlich, H.; Strecker, G.E. Abstract and Concrete Categories. The Joy of Cats, TAC Reprints No. 17. 2006. Available online: http://www.tac.mta.ca/tac/reprints/articles/17/tr17.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Bühler, T. Exact categories. Expo. Math. 2010, 28, 1–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).