Abstract

This study diagnoses how the plurilingual repertoires of mature students (MS) in higher education (HE) are constructed throughout their lives. It addresses the main characteristics of MS; the contexts in which they move throughout their lives, and the situations they contact with languages. Data were collected by means of a questionnaire, mostly comprising open-ended questions. The questionnaire was emailed to 485 MS and was filled in by 195 (40.2%). The results highlight the intrinsic relationship between the MS’ life histories and the construction of their plurilingual repertoires. The findings reinforce the relevance of considering the MS’ plurilingual repertoires and life histories in the development of educational linguistic policies in HE.

1. Introduction

The purpose of this study is to diagnose the plurilingual repertoires of mature students (MS) in higher education (HE). This diagnosis is developed by analyzing the way the plurilingual repertoires are constructed throughout the students’ lives.

Plurilingual repertoires can be understood as a set of verbal and nonverbal resources that the subject, as a social actor, has at his/her disposal to communicate, to interact, to address communicative needs and desires, and/or to find local solutions to practical problems [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Considering that language learning is not a cumulative or segmented process, but a growing one, that follows the subject’s life path [1], plurilingual repertoires are strongly grounded on a biographical dimension, presenting themselves as a reflection of the lived experiences of languages [6] that the subject experiences throughout his/her life.

A careful comparative analysis of studies on non-traditional students, namely mature students (MS) [9,10], and on the development of plurilingual repertoires [1,2] reveals important common features between both research areas, largely based on the fact that a biographical perspective is followed in each case [11,12]. In fact, understanding MS by means of the analysis of the development of their plurilingual repertoires contributes to a better awareness of their life journeys, namely the contexts in which they move until the moment they reach higher education (HE). At the same time, it also enhances a better understanding of their career as HE students. Similarly, to analyze the construction of plurilingual repertoires throughout the life path of MS is to reinforce its biographical character, inseparable from the contexts in which the subjects move, the people with whom they live, and the choices they make throughout their life path.

The study intends to identify (i) the contexts and the situations in which MS move throughout their lives and (ii) which languages they contact with. In order to achieve these goals, the data were collected by means of a questionnaire, which allowed access to the MS’ language biographies.

In this paper, we will begin by addressing the concept of a plurilingual repertoire, focusing on its biographical dimension and on the multiple contexts in which it develops (Section 2.1). Then, we will focus on the main characteristics of MS (Section 2.2). In the second part of the paper, we will present the study’s methodological design, namely the data collection instrument used (Section 3). Subsequently, we will present and discuss the main research results (Section 4). Lastly, following a summary of the study’s main results, we will discuss the relevance of considering the MS’ voices within the framework of educational language policy development in higher education (Section 5).

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Plurilingual Repertoire and Its Contexts of Development

The plurilingual repertoire can be understood as a set of resources, verbal and nonverbal, that the subject, as a social actor, has at his/her disposal to communicate, to interact, to address communicative needs and desires and/or to find local solutions to practical problems [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Presented as a patchwork [1,3] or a bricolage [13] of resources, the plurilingual repertoire is perceived as a kind of “tool-boxes for tinkerers” [2] (p. 9) and it is never completed, since “there are always resources that we do not possess” [14] (p. 105). Considering that language learning is not a cumulative or segmented process but a growing one that follows the subject’s life path [3], the plurilingual repertoire appears to be fundamentally open [6], meaning that resources are not stable sets of language variants and varieties, and, therefore, subjects have different levels of proficiency in different languages [3].

Each of the life trajectories, unique in each subject, contributes to the plurilingual repertoire with linguistic resources, but also contributes with ‘material’ to form social roles, to create identities, to be seen in a certain perspective by the Other, making the plurilingual repertoire “a unique reflex of a unique biography” [1] (p. 29), by reflecting in great detail the life path of the subject [1,3,4].

Consequently, the biographical dimension of the plurilingual repertoire emerges as something unavoidable to its definition. In other words, the plurilingual repertoire, also understood as an “indexical biography” [1], depends on the subjects’ biography [4]. This biographical dimension illustrates which languages are learned/contacted at different ages and in multiple situations and contexts throughout the subject’s life [15].

Regarding these multiples contexts, it seems clear that the plurilingual repertoire is the result of polycentric learning contexts [3,16,17], in which one “developed explosively in some phases of life and gradually in some others” [1] (p. 15). Four main contexts can emerge in the analysis of the plurilingual repertoires’ development: personal, academic, professional, and mobility.

Regarding the personal context, it is clear that family is, undoubtedly, an important sociolinguistic environment in which the development of plurilingual repertoire is concerned [18,19]. Moreover, several studies highlight the role of family and of the group of friends in informal language learning as well as the role of activities of leisure, such as travel/tourism [4,7,20,21,22].

Regarding the educational path, the academic context, divided into pre-HE and HE, can be highlighted. Considering pre-HE and despite that the increased visibility of linguistic (super)diversity may not be reflected deeply in classroom practices [23], several studies suggest that it is possible and required to mobilize all languages in students’ plurilingual repertoires in order to create inclusive classroom spaces and to foster learners’ plurilingual identities [4,7,17,24,25,26,27]. Concerning HE, the development of plurilingual repertoires seems to be intrinsically linked to the construction of knowledge, since the subject has access to more contacts with foreign languages, namely through new readings, new lectures, new social interactions, new findings, and, therefore, more new knowledge [28,29,30,31,32,33].

In this super diverse society [1], namely, in a professional context, people with different languages are required to work together, which leads to various forms of communication between colleagues who are more or less plurilingual [34]. Therefore, a plurilingual repertoire appears to be a resource for the construction, transmission, and application of knowledge within professional contexts [35]. Studies suggest that professional context is one of the most dynamic regarding the development of plurilingual repertoire [36], highlighting how subjects mobilize and develop it in multiple professional settings, such as multinational companies [25,37], multilingual educational institutions [38,39], diplomatic institutions, such as the United Nations [40] or the European Union institutions, [41] or within physician-patient interaction [2,42].

Regarding the mobility context, which is a transversal one, many studies suggest that the plurilingual repertoire is expanding with situations of mobility, particularly migration [27,36,43]. These studies highlight, in particular, new language practices linked to new situations of interaction and contact of subjects’ languages, whether in relation to their heritage languages, the languages of the host country, or others. Those situations of contact with new languages influence the linguistic dynamics of families [18,19] and the formal educational contexts [4,44], as well as the everyday communicative practices [45] of communities and of social networks [42]. Also, the professional dynamics and career paths appear to be profusely influenced by mobility trajectories [27,37,43]. The plurilingual repertoires also expand, in particular, mobility situations, as is the specific case of international students [46,47] or refugees [48,49].

To sum up, plurilingual repertoires reflect the subjects’ life experiences with languages [6], which occur within a great variety of contexts/situations. Our study’s results, as we will show, reflect the great diversity of contexts/situations by which the mature students’ (MS) plurilingual repertoires are constructed. In fact, these repertoires in a large manner embody their lived experiences of languages since their birth until they enroll in HE.

2.2. Mature Students: Who Are They?

It is possible to find, in the specialized literature on this matter, a number of different terms to describe the MS in HE, ranging from “non-traditional students” [9] and “working students” [14,50] to “new publics in HE” [51,52]. The diversity of terms, often apprehended, quite simplistically, as synonyms, is indicative of the diversity of theoretical references associated with adult education in HE [10].

As stated by Fragoso [9], the concept of non-traditional students can be defined in accordance to two major criteria: (i) diversity of all the different groups of students who constitute a minority in HE [53], or (ii) students whose participation and academic success is constrained by structural factors [54,55].

However, the existence of a designation under which adult students seeking access to HE are grouped can hide the fact that this is not a homogeneous group, since each subject has his/ her own life history, motivations, and expectations, which influence his/her process of transition to this level of education [9,10,56]. Furthermore, the term non-traditional students is so wide-ranging that it could refer to diversified groups, for instance, those with special educational needs, women, the first of their families to come to HE, working-class students, immigrants or members of cultural minorities, and others [9,57].

Despite this natural heterogeneity of an increasingly diverse student population, there are some characteristics that are pointed out in the literature as being largely shared among these non-traditional students. Some of these characteristics are related, for instance, with age, gender, learning career, and/or professional status. In relation to age, it is perceived that non-traditional students are 25 years or older HE students [9,58] whereas the traditional ungraduated students are aged between 18 and 21. It should be noted that in some countries, like Portugal, the designation non-traditional is used to students who are over 23 years old [59]. Regarding the students’ gender, several studies [60,61,62] highlight that the majority of non-traditional students are male, stressing the persistence of some degree of inequality in this context, in which female students are still a minority. As far as a learning career is concerned, studies indicate that non-traditional students are likely to have had more varied and fragmented learning careers and have taken time off before returning to school [9,63,64,65]. The multiple and complex character of these students’ learning careers is due to the influence of several factors, namely external factors (regional, state, and European policies; local and community environment; family environment) and internal factors (institutional cultures of universities, teaching, and learning processes; everyday educational practices) but also to the dynamics of the self, both psychological and social [66]. Concerning non-traditional students’ professional status, according to the literature, the majority of these students come from the working class or from more disadvantaged social classes and work at least a part-time if not a full-time job in addition to attending HE [9,67].

As said, in comparison to traditional-aged students, non-traditional have a higher probability of belonging to more disadvantaged social classes, and they are more likely to have had diverse and fragmented learning careers before their admission to HE. Meanwhile, in that period, they lived other experiences in multiple contexts, having many roles associated with familiar, professional, and economic responsibilities [68,69,70,71]. Due to these multiple responsibilities, and as stated by Kasworm [72], these students show a higher maturity level and developmental complexity acquired through life. However, those different roles are not always easy to conciliate with academic life [57,73], and non-traditional students do not have the possibility to devote themselves full time to university and to studies. In this sense, it is clear that HE (academic context) is not the central feature of their lives, but just one of the multiple activities in which they are daily engaged [74]. Consequently, the majority of the non-traditional students show a great sense of responsibility with which they face their academic tasks. For this reason, some authors advocate the term ‘Mature Students’ (MS), enhancing their specific relation towards HE [70,72,75,76]. MacCune et al. [69] go further and argue that MS could also be organized into two sub-groups: younger MS, those between the ages of 21 and 30, and older MS, those aged 31 and over, since even these two groups have differences in terms of caring responsibilities, lifestyle, and reasons for study, such as career progression, future professional projects, or personal enrichment.

The multiple responsibilities that MS take on have repercussions in the learning process in HE. Balancing all the full-time commitments appears not to be easy; otherwise, there would not be such a high level of setbacks along their HE pathway [77]. According to Swain and Hammond [78], the most significant learning constraints are related to young children, high-pressure jobs, unsupportive partners, personal and family health problems, and difficulties with languages.

Regarding this last constraint, MS may (or may not) have plurilingual experiences in different contexts and, consequently, have different degrees of interaction with languages. These plurilingual experiences are embodied in their plurilingual repertoires [1], mirroring the various ways individuals interact with languages in multiples contexts, namely, in HE, as we will explain below.

3. Method

In this article, we intend to understand how the plurilingual repertoires of MS are constructed throughout life. More specifically, we intend to identify and discuss (i) the contexts in which MS attending the University of Aveiro, Portugal, move throughout their lives, and (ii) the situations within these contexts they contact with languages and which languages MS contact with.

As mentioned previously, the plurilingual repertoire can be understood as a set of biographically organized resources [1], reflecting the subject’s life history and biographical trajectories [12] that are constructed in plural social interactions. Therefore, we use a biographical approach [11,12] as the research method to access the plurilingual repertoire. The language biography appears as a privileged tool since it allows us “to understand how and why the relationship to languages is developed and modified during the course of life on a subject related to mobility and migration, while reworking its linguistic, cultural and identity repertoire” [35] (p. 147). On the one hand, this approach allows the learning subject to value his/ her plurilingual repertoire and the multiple contexts in which it is developed; on the other hand, the biographical approach also underlines the linguistic and cultural learning carried out in the interaction with the Other [12].

Data Collection Instrument

In order to access MS’ language biography, the data was collected by means of a questionnaire, with mostly open-ended questions. The questionnaire had, besides the socio-economic characterization section, four other sections: (i) MS’ mother tongue(s), (ii) foreign languages learned in formal and non-formal contexts, (iii) contacts with foreign languages, and (iv) foreign languages learned or meant to be learned in the future and why.

After a pre-test conducted with a group of similar students in order to validate the questionnaire, its final version was emailed to the 485 MS that were attending the University of Aveiro and was filled in by 195 MS (40.2%).

The data collected were analysed through the use of the software NVivo (open-ended questions) and the software SPSS, version 25 (closed questions).

4. Results Presentation and Discussion

Firstly, we will address the study’s findings regarding the MS’ general features (Section 4.1) and then, in accordance to our research questions (see Section 3—Method), we will describe the contexts and situations in which MS contact with foreign languages, identifying these same languages (Section 4.2).

4.1. Mature Students: Who Are They?

The analysis of the results shows that the sample consisted of 105 men (53.8%) and 90 women (46.2%), aged between 23 and 79 years old, most of them in between 26 and 40 years old (n = 136, 69.7%), as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mature students’ gender and age.

The average age of the MS is 34.5 years old. Using the MacCune et al. [69] definition of MS, the results show that most of the subjects are older MS, as they are aged between 31 and 66 (n = 119, 61%). This conclusion is reinforced by the analysis of the average age per year of the degree MS are currently attending, since it is always above 33 years old (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Mature students’ average age by year of degree.

Regarding gender, the majority of MS are men (n= 105, 53, 8%), as in the studies considered in the literature review. However, in this case, contrary to what was presented by Merrill [61] and Quinn [62], women are also a minority, but they represent 46.2% (n = 90) of all MS in the study. In fact, the results show that in the first year, there are six more women than men attending HE degrees, and in the third year, the number of females is very similar to the number of males.

Concerning MS’ learning career, the results indicate that before their current HE attendance (Academic Context Pre-HE), the vast majority have secondary education attendance from 10th to 12th grade: the majority of MS (n = 107, 54.9%) have the 12th grade, 45 MS have the 9th grade (23.1%), and 21 respondents have the 11th grade (10.6%). The option of 12th grade incomplete was indicated by 12 MS (6.2%. The Vocational Education and Training courses (VET) was marked by ten subjects (5.2%)). For instance, focusing only on the 82 MS attending the first year of their degree, the majority (n = 70, 85.3%) have secondary education attendance.

In order to estimate how long these 70 MS have been away from formal education, the average age of secondary school students, 17 years old, will be taken as the starting point. The results indicate that the average number of years that these MS were away from formal education is 21 years. The lowest number is seven years away from formal education, and the highest value is 36 (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Mature students’ average number of years away from formal education.

These results also unveil the fragmentation of these students’ educational paths, as stated, for instance, by Fragoso [9], Kasworm [64], and Williams and Seary [65].

As far as the HE attendance is concerned, most of the MS (n = 92, 47.2%) are attending the first year, 34 of the respondents attending the second year (17.4%), while 62 are in the third year (31.8%). The current frequency of the second cycle—integrated master’s degree—was marked by seven of the MS (3.6%). As indicated in Table 2, 18 MS that are in the first year have two or more enrolments in that year. Regarding the second year, 13 MS are attending the second year for the second time or more. Twenty MS are repeating the third year for the second time or more. Regarding the master, three MS are in their second enrolment or more (see Table 4). It should be noted that these are full-time and not part-time enrolments.

Table 4.

Number of Enrolments.

Analyzing the data in Table 5, it could be concluded that around 30% of these MS (n = 63, 32.3%) have, at least, one more enrolment than was supposed, considering the year they are attending.

Table 5.

Attended language courses.

Still concerning HE attendance and according to the results, most MS attend degrees in the scientific area of the Social Sciences and Humanities (n = 131, 66.8%). In this scientific area, the degrees with ten or more MS attendance are Public Administration (n = 27), Languages and Business Relations (n = 16), Basic Education (n = 13), Design (n = 12), and Office Administration Studies (n = 10). The second most chosen scientific area is Exact Sciences and Engineering (n = 47, 24.7%), from which two degrees with more than ten students stand out: Information Technologies (n = 14, 7.2%) and New Communication Technologies (n = 12, 6.7%). The scientific area of Life and Health Sciences, chosen by 16 MS (8.2%), does not have any degree with ten or more students enrolled. However, we can highlight Biology and Nursing degrees with seven MS each. The Natural and Environmental Sciences area, namely a Meteorology, Oceanography, and Geophysics degree, was the choice of one MS.

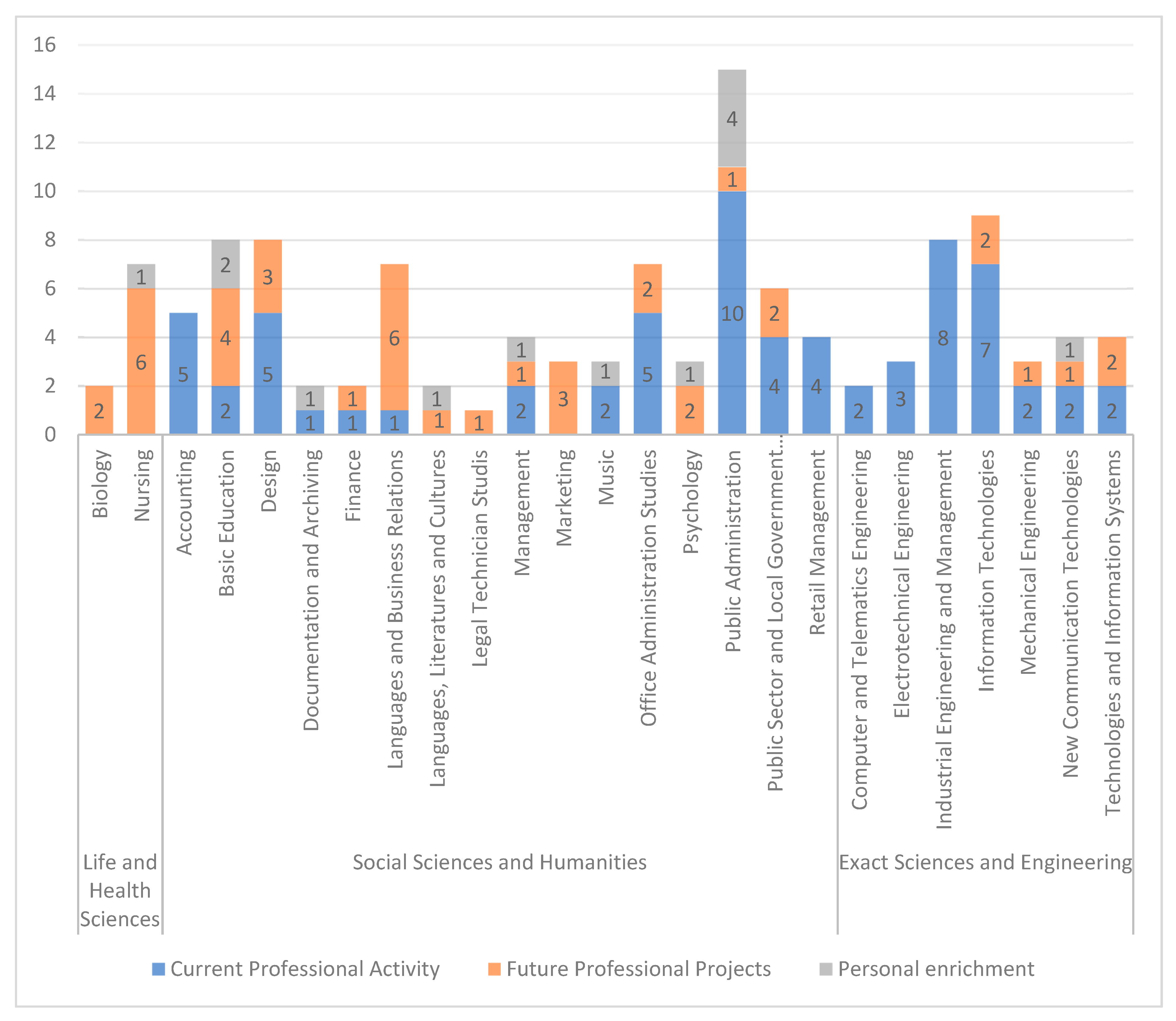

Regarding the main reasons to choose a HE degree, 122 MS (62.5%) stated that their degree is related to their current professional activity (n = 68), future professional projects (n = 41), and personal enrichment (n = 13). In the area of Life and Health Sciences, the degree choice is mostly related to future professional projects, while in the areas of Social Sciences and Humanities and Exact Sciences and Engineering, there seems to be a strong connection with the MS’ current professional activity.

In more detail, in the area of Social Sciences and Humanities current professional activity, for instance in Public Administration, Accounting, Design, and Office Administration Studies degrees, several MS indicate the connection between their current job and the area of the degree as the reason to attend the HE degree. Concerning the Exact Sciences and Engineering area, the current professional activity is the strongest reason for MS to choose the HE degree, as for example, in the degree of Industrial Engineering and Management and Information Technologies. It is also important to note that in the area of Social Sciences and Humanities, there is some considerable relation with future professional projects, mainly in Languages and Business Relations, Basic Education, Marketing, and Design (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mature students’ reasons to choose a higher education (HE).

In sum, back to the initial question, ‘Mature Students: Who Are They?’, and taking into account the results, in this study, MS are slightly more men than women with 34.5 years old as the average age. Most of these students have the 12th grade or secondary school attendance, and the average number of years away from formal education, before applying to HE, is 21. Regarding the HE attendance, most of the MS are attending the 1st year, and around 30% of them have, at least, one more enrolment than it was supposed, considering the year they are attending. In relation to the reasons for the choice of the degrees attended, the professional context (current and future) emerged as the main reason. More specifically, in the area of Life and Health Sciences, the degree choice is mostly related to future professional projects, while in the areas of Social Sciences and Humanities and Exact Sciences and Engineering, there seems to be a strong connection with the MS’ current professional activity.

4.2. Mature Students: In Which Contexts Do They Have Contact with Languages?

Recalling the two previous research questions (see Method Section), it could be stated that in this study, there are three main contexts that contribute significantly to the development of plurilingual repertoires: personal, academic, and professional contexts.

4.2.1. Personal Context

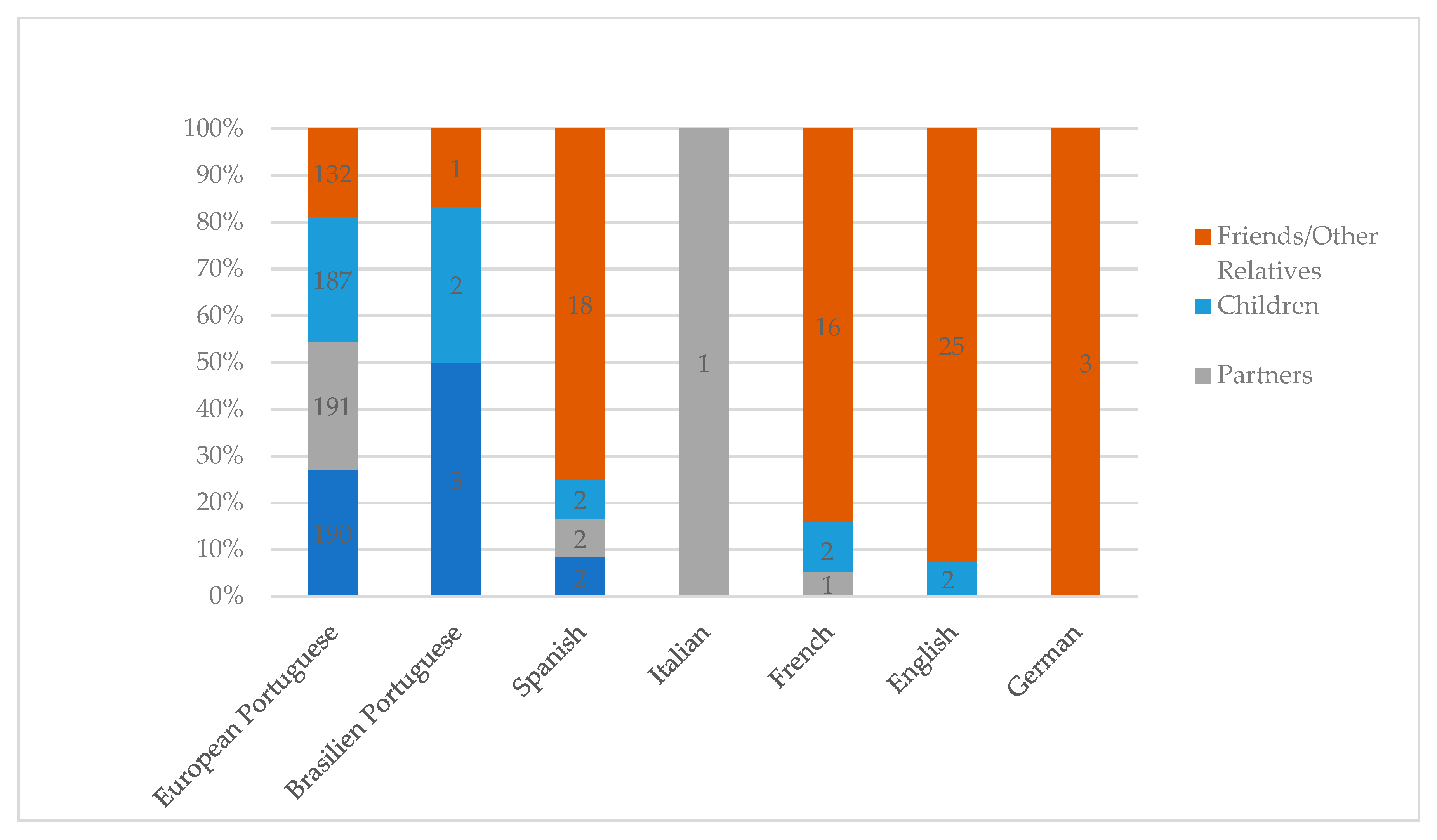

Regarding the personal context, which refers to languages mobilized in the interaction with parents, partners, children and friends, or other relatives, most of the MS refer European Portuguese as the mother tongue and as the most widely spoken language, namely with their parents, partners, and children. However, as shown in Figure 2, it is with friends and with extended family that there is more linguistic diversity: besides European Portuguese, MS indicate English, Spanish, French, and German as the languages mobilized into the informal context of interaction with friends and other relatives.

Figure 2.

Languages and personal context.

As seen in Figure 2, the results indicate the personal context, namely family, as an important setting in the development of plurilingual repertoires [18,19]. However, our results also underline the development of MS repertoires as a result of interactions in personal context with different social actors, specifically close friends and extended family. These findings highlight the biographical dimension of the plurilingual repertoires since subjects have different friends throughout life, with different characteristics and important influences.

4.2.2. Academic Context

When asked about their contact with foreign languages in an academic context (pre-HE), most of the MS (n = 188) indicated that they have come into contact with French and English. Only seven MS report not having learned foreign languages in formal settings pre-HE.

As far as HE is concerned, 105 MS (53.9%) attend HE degrees with foreign language courses in their curricula (see Table 5).

As it could be seen, most MS have English as the only foreign language in the attended degree. Only 33 (16.9%) subjects have formal contact with other languages, such as Arabic, Chinese, French, German, and Spanish. The findings, similarly to other studies [30,31,32], emphasize the role of a single language, English, as a tool of economic and professional empowerment for students. Even though European language diversity and the growing academic and professional mobility (physic and virtual) are a reality, it seems that HE Institutions tend to value only the instrumental role of English [58]. In spite of the fact that European language education policies have been underlining the need for Higher Education Instituitions (HEI) to develop plurilingual policies, namely by providing the possibility of language learning, the truth is that HEI throughout Europe have been tending towards monolingual education policies [31].

Accordingly, in our previous study [79], findings indicate that the inclusion of formal language learning in HE, through language courses, is more valued by MS than by institutional actors even if most students also value only English and consider it important to be included in the curricula.

The results also indicate that the HE attendance is seen by the majority of MS (n = 140, 71.8%) as a positive influence in the development of their plurilingual repertoires. Accordingly, MS underline the fact that the academic life, in multiple ways and levels, allows students to have contact with different languages and peoples (the translation of MS’ voices is the responsibility of the authors of this paper):

No matter the degree, with or without languages, either in terms of programmatic content or even in the level of research carried out by students in any other language, this [the HE attendance] will contribute to their [MS] development in the knowledge of other languages (MS26/195).

Contact with students and Professors from other countries leads to an opening to and development of languages (MS129/195).

Thus, MS emphasize the role of languages in social interactions in academia, arguing that:

As the student universe is filled with the most diverse nationalities, we have contact with several languages (MS16/195).

During the day, we meet and communicate with people from other countries and we do it in different languages (MS37/195).

When we meet people from Erasmus programs, if we want to communicate, we must strive to understand each other (MS187/195).

In addition to social interactions, MS consider that academic tasks are an opportunity to promote the development of their plurilingual repertoire. Particularly, MS referrer to bibliographic reading:

We always have to read books that are in other languages and that forces us to learn (MS9/195).

And along with that task, they also mention the importance of attending conferences:

We have to attend several conferences with foreign speakers and we have a lot of bibliographies also in foreign languages (MS2/195).

We can attend lectures presented in other languages, work with programs and manuals in other languages (MS41/195).

The development of plurilingual repertoire within the research was also underline by a mature student that states that:

At the research level, is all [tasks] in foreign languages (MS85/195).

MS also stress the importance of the development of their plurilingual repertoire during HE attendance in order to access new knowledge:

By accessing foreign language manuals and resources, it enables access to new knowledge (MS36/195).

It [the foreign language knowledge] prepares us to obtain and understand, more efficiently, information that does not exist in Portuguese (MS101/195).

In the learning path, it is necessary to understand some subjects [in foreign language] that are not available in my mother tongue (MS63/195).

However, it is stressed that English is the predominant language in the academic context as it is argued that

Much of the necessary bibliography is in English (MS40/195).

Most of the information search is done on English sites (MS53/195).

Even if this predominance seems to be felt as an imposition (MS189):

We find ourselves “obligated” to read a lot in English (MS189/195).

Nevertheless, the use of another language enhances new connections with knowledge by requiring other ways of saying things, as mentioned by this MS:

The daily contact with diverse literature, as well as the need to write in English, force me to rethink the way I express myself and make myself understood in a language other than Portuguese (MS3/195).

In a nutshell, these last findings reinforce the role of the social interactions with foreign actors in academic contexts, namely Erasmus students, in the expansion of the plurilingual repertoire [46]. These contacts embody one of the main goals of HE: to develop transversal skills in students that enhance their mobility and their ability to live in culturally diverse societies [32]. The findings also underline the relation between the accomplishment of academic tasks of diverse nature and the development of plurilingual repertoires [28,29] since most students (n = 140, 71.8%) consider that the HE attendance and its inherent tasks promote the development of their plurilingual repertoire, namely the construction of knowledge. In addition to the highlighted English predominance, it is also clear to these MS that being able to work in several languages could be important, and it is considered as an advantage, but it is simultaneously very demanding [38].

4.2.3. Professional Context

A total of 138 MS (70.8%, n = 195) state that they have contact with foreign languages in a professional context. Most of the subject have contacts with English (n = 58) or English with other languages (n = 65), such as Spanish (n = 16) or French (n = 15) or both (n = 20). French was indicated by two subjects and Spanish by six. Table 6 specifies the languages mobilized in this context as well as the situations that specify the languages mobilized in various situations in this context.

Table 6.

Contact with languages in the professional context.

As stated by several authors [35,36,37], this study also suggests that the professional context is one of the most dynamic regarding the development of a plurilingual repertoire. Similarly to the academic context, there is a dominance of the English language in the professional settings (n = 58), but most subjects (n = 65) contact simultaneously with other languages, such as French, Spanish, or German.

Considering the situations of contact with languages mentioned above, oral interactions (face-to-face or at a distance) in assistance tasks are those with more linguistic diversity (English, Spanish, French, German, and Italian in different combinations). Accordingly, 34 MS have contact with suppliers and/or customers in multiple languages, mainly English, Spanish, and French. The plurilingual repertoires of these subjects are also mobilized when they need to read documents (n = 20), mainly in English but also in French, Spanish, German, or Italian. Working in a global labor market means to have meetings with different actors, which have different plurilingual repertoires. In this sense, subjects (n = 14) refer that they have meetings in English, Spanish, French, and Italian (with different combinations). These findings indicate that plurilingual repertoire and its mobilization during social/professional interactions are central to the individual’s employability and careers.

We conclude this section with the voice of one mature student who highlights this close relationship between the academic context (HE) and the professional one regarding the dynamics of plurilingual repertoire, stating,

Much of our literature review is in foreign language, so we always increase our [languages] knowledge, and also, in the work context, we have to deal with people who speak other languages, which will also increase our [languages] knowledge (MS53/195).

5. Final Considerations

The analysis of the MS’ lifepaths unveils the “fragmentation” of these students’ learning careers [9,64]. The diverse and disjointed character of their learning careers provided them experiences in multiple contexts, promoting the development and enlargement of their plurilingual repertoires.

Our study points out three main contexts that significantly contribute to the development of plurilingual repertoires: personal, academic, and professional contexts.

In the personal context, it is highlighted, for instance, the contribution to the development of the plurilingual repertoire of the subjects’ interactions with extended family and friends, namely, in English, Spanish, and French.

Regarding the academic context, our data show that in pre-HE, most of the mature students had language courses in their school curricula, namely English and French. In HE, only 39% of MS have language courses in their curricula. However, all the study’s subjects indicate that they research bibliographies in one or more foreign languages, namely English and Spanish. In our perspective, this result highlights the strong interconnectedness between the development of plurilingual repertoires and the construction of knowledge [28,29]. The interactions with foreign colleagues—which is indicated by 34 subjects—also stand out as an important factor in the development of the MS’ plurilingual repertoire [46].

Our study also shows that, as stated by several authors, such Hewitt [36] or Lüdi, Höchle Meier and Yanaprasart [37], the professional context is one of the most dynamic when it comes to the development of plurilingual repertoires. According to our results, 64% of the study’s subjects have contact with foreign languages in their working contexts, such as English, Spanish, French, Italian, and German.

The findings show that the majority of MS already work in a globalized labor market, some have experience in mobility, and all of them have been acquiring and developing their plurilingual repertoire by coming into contact with different languages throughout their lives. The results also indicate that, on the one hand, MS mobilize their prior language knowledge to accomplish multiple academic tasks in HE. On the other hand, although asserting that learning and using several languages in their professional activities can be considered as an advantage to their careers, they simultaneously have language difficulties in the use of foreign languages, considering their learning and usage very demanding.

These pieces of evidence lead us to underscore the importance of studying the MS’ lifepaths in order to better understand the development of plurilingual repertoires. This is particularly relevant in the HE setting, where institutions should be led to “hear” the MS’ “voices”, in order to be able to meet their specific educational and training needs, as well as help them to better integrate and develop they studies in the HE context. Additionally, by considering these MS’ voices, HE Institutions will have access to privileged information regarding the labor market dynamics and the skills needed to succeed in this dimension, namely, in terms of language skills levels. HE Institutions have an important role in developing a kind of transversal skills that are capable of enhancing the students’ mobility, their ability to live in linguistic and culturally diverse societies, and their integration into a globalized labor market [30,31,32,33]. This necessarily implies taking into account the students’ life histories as well as their practical needs and aspirations. In our perspective, the MS’ particular training needs have been largely disregarded in the development of educational language policies in higher education. Recent research in the context of HE has shown that language education policies cannot be carried out independently of social actors and that students’ voices and life and educational paths should not be undervalued in institutional language policy and educational planning [80]. However, although we can find some studies that give voice to students in matters related to educational language policies [81], the same cannot be said to studies focusing on MS and their pathways. Hence, by aiming at giving voice to those students by addressing the contexts in which they move throughout their lives and the situations of language contact, this study also intends to open up a line of research that has been largely overlooked.

In conclusion, this study allowed us to diagnose the plurilingual repertoire that MS develop throughout their lives and that they mobilize or can mobilize in the context of HE. In a second moment, it also allowed us to identify the training needs felt by these students, with regard to language education in general and to educational language pol53icies in particular.

As long as prevailing educational language policies do not consider all voices, namely those of MS, it is always up to the subject to develop his/her plurilingual repertoire by embracing incidental and/or contingent personal or professional language needs and desires and never forget that a rolling stone gathers no moss.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A., M.H.A.e.S. and A.R.S.; Methodology, S.A.; Formal Analysis, S.A.; Investigation, S.A., M.H.A.e.S. and A.R.S.; Writing—S.A.; Writing—Review & Editing, S.A., M.H.A.e.S. and A.R.S.

Funding

This article was made possible by the national funding through the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT), project SFRH/BD/47533/2008 Funding: This article was made possible by the national funding through the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT), project SFRH/BD/47533/2008 and project UID/CED/00194/2019.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Blommaert, J.; Backus, A. Superdiverse Repertoires and the Individual. In Multilingualism and Multimodality: Current Challenges for Educational Studies; Saint-Jacques, I., de Weber, J.J., Eds.; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lüdi, G. Plurilingual speech as legitimate and efficient communication strategy. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blommaert, J. The Sociolinguistics of Globalization; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Beacco, J.-C.; Byram, M.; Cavalli, M.; Coste, D.; Cuenat, M.E. Guide for the Development and Implementation of Curricula for Plurilingual and Intercultural Education; Language Policy Division, Directorate of Education and Languages, DGIV Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Berthoud, A.-C. Introduction. In Plurilinguismes et Construction des Savoirs. Cahiers de l’ILSL; Berthoud, A.-C., Gradoux, X., Steffen, G., Eds.; Centre de Linguistique et des Sciences du Langage de l’Université de Lausanne: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2011; Volume 30, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Busch, B. Expanding the notion of the linguistic repertoire: On the concept of spracherleben—The lived experience of language. Appl. Linguist. 2017, 38, 340–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coste, D. Plurilingualism and the challenges of education. In Plurilingual Education: Policies—Practices—Language Development; Grommes, P., Hu, A., Eds.; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Piccardo, E.; North, B.; Goodier, T. Broadening the scope of language education: Mediation, plurilingualism, and collaborative learning: The cefr companion volume. J. E Learn. Knowl. Soc. 2019, 15, 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Fragoso, A. A investigação no campo dos Estudantes Não-Tradicionais no Ensino Superior: O 1° ano em debate. In Ser Estudante no Ensino Superior: O caso dos estudantes do 1° ano; Almeida, L.S., de Castro, R.V., Eds.; Centro de Investigação em Educação (CIEd) da Universidade do Minho: Braga, Portugal, 2016; pp. 39–63. [Google Scholar]

- Fragoso, A.; Valadas, S.T. Dos Novos Públicos do Ensino Superior aos estudantes ‘não- tradicionais’ no Ensino Superior: Contribuições para a construção de um breve mapa do campo. In Estudantes Não-Tradicionais no Ensino Superio; Fragoso, A., Valadas, S.T., Eds.; CINEP: Coimbra, Portugal, 2018; pp. 19–38. [Google Scholar]

- Merrill, B.; West, L. Using Biographical Methods in Social Research; Sage: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, D.-L.; Thamin, N. Réflexion Epistémologique sur la Notion de Biographies Langagières. Carnets d’Ateliers Socioling. 2009, 4, 15–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lüdi, G. Mesures de gestion des langues et leur impact auprès d’entreprises opérant dans un contexte de diversité linguistique. Synerg. Ital. 2013, 9, 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Fenech, C.S.; Raykov, M. Studying and Working-Hurdle or Springboard? Widening Access to Higher Education for Working Students in Malta. In European Higher Education Area: The Impact of Past and Future Policies; Curaj, A., Deca, L., Pricopie, R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 237–258. [Google Scholar]

- Berthoud, A.-C.; Grin, F.; Lüdi, G. Conclusion. In Exploring the Dynamics of Multilingualism. The DYLAN Project; Berthoud, A.-C., Grin, F., Lüdi, G., Eds.; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 429–436. [Google Scholar]

- Lüdi, G. Communicative and cognitive dimensions of pluricentric practices in French. In Pluricentricity: Language Variation and Sociocognitive Dimensions; Silva, A.S., Ed.; Gruyter Mouton: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 49–82. [Google Scholar]

- Stratilaki, S. Plurilingualism, linguistic representations and multiple identities: Crossing the frontiers. Int. J. Multiling. 2012, 9, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curdt-Christiansen, X.L.; Lanza, E. Language management in multilingual families: Efforts, measures and challenges. Multiling. J. Cross Cult. Interlang. Commun. 2018, 37, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Houwer, A. Harmonious Bilingualism: Well-being for families in bilingual settings. In Handbook of Social and Affective Factors in Home Language Maintenance and Development; Eisenchlas, S., Schalley, A., Eds.; Mouton de Gruyer: Berlin, Germany, in press.

- Phipps, A. Learning the Arts of Linguistic Survival (Tourism and Cultural Change); Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Auer, P.; Wei, L. Introduction: Multilingualism as a problem? Monolingualism as a problem. In Handbook of Multilingualism and Multilingual Comunication; Auer, P., Wei, L., Eds.; Mouton de Gruyer: Berlin, Germany, 2007; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lüdi, G. De la compétence linguistique au répertoire plurilingue. Bull. VALS-ASLA 2006, 84, 173–189. [Google Scholar]

- Hélot, C. Linguistic diversity and education. In The Routledge Handbook of Multilingualism; Martin-Jones, M., Blackledge, A., Creese, A., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 214–231. [Google Scholar]

- Araújo e Sá, M.H. A intercompreensão nas disciplinas de línguas do ensino secundário: Um estudo com duas turmas de espanhol em Portugal. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación 2019, 81, 135–165. Available online: https://rieoei.org/RIE/article/view/3605/4056 (accessed on 18 September 2019).

- Lüdi, G. Dynamics and management of linguistic diversity in companies and in instituitions of higher education. Results from the DYLAN-project. In Plurilingual Education. Policies—Practices—Language Development; Grommes, P., Hu, A., Eds.; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amesterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 113–138. [Google Scholar]

- Simões, A.R.; Senos, S. Desenvolvimento curricular e didática students’ representations of languages in a ten-year time gap: Are there any differences? Indag. Didact. 2019, 11, 1647–3582. [Google Scholar]

- Billiez, J. Plurilinguismes des descendants de migrants et école: Évolution des recherches et des actions didactiques. Cah. du GEPE 2012, 4. Available online: http://cahiersdugepe.fr/index.php?id=2167 (accessed on 25 March 2019).

- Gajo, L.; Berthoud, A.-C. Multilingual interaction and construction of knowledge in higher education. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2018, 21, 853–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, L.; Moore, E.; Borràs, E. Accomplishing multilingualism through plurilingual activities. In Exploring the Dynamics of Multilingualism. The DYLAN Project; Berthoud, A.-C., Grin, F., Lüdi, G., Eds.; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 229–252. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, S.; Araújo e Sá, M.H. Language education at the University of Aveiro before and after Bologna: Practices and discourses. Lang. Learn. High. Educ. 2013, 2, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pinto, S.; Araújo e Sá, M.H. Language learning in higher education: Portuguese students’ voices. International. J. Multiling. 2016, 13, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, S.; Araújo e Sá, M.H. Políticas linguísticas de formação e de investigação em universidades públicas portuguesas: Das tensões a eixos de reflexão-ação. Rev. Lusófona Educ. in press.

- Araújo e Sá, M.H.; Hu, A.; Pinto, S.; Wang, L. The role of language and languages in doctoral education. In The Doctorate as Experience in Europe and Beyond. Supervision, Languages, Identities; Byram, M., Stoicheva, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, Chapter 8; in press.

- Yanaprasart, P. Managing language diversity in the workplace: Between one language fits all and multilingual model in action. Univ. J. Manag. 2016, 4, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthoud, A.-C. Le projet DYLAN—Un aperçu des résultats. Bull. l’Académie Suisse Sci. Hum. Soc. 2012, 2, 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt, R. Multilingualism in the workplace. In The Routledge Handbook of Multilingualism; Martin-Jones, M., Blackledge, A., Creese, A., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 267–280. [Google Scholar]

- Lüdi, G.; Höchle Meier, K.; Yanaprasart, P. Managing Plurilingual and Intercultural Practices in the Workplace: The Case of Multilingual Switzerland; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Heidenfeldt, W. Conflict in the Second Language Classroom: A Teacher of Spanish Facing the Complex Dimensions of Multilingualism. In The Multilingual Challenge: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives; Jessner, U., Kramsch, C., Eds.; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin/Boston, Germany, 2015; pp. 63–86. [Google Scholar]

- Veronesi, D.; Spreafico, L.; Varcasia, C.; Vietti, A.; Franceschini, R. Multilingual higher education between policies and practices. A case study. In Exploring the Dynamics of Multilingualism. The DYLAN Project; Berthoud, A.-C., Grin, F., Lüdi, G., Eds.; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 253–279. [Google Scholar]

- McEntee-Atalianis, L. Language policy and planning in international organisations. In The Multilingual Challenge: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives; Jessner-Schmid, U., Kramsch, C.J., Eds.; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 295–322. [Google Scholar]

- Kruse, J.; Ammon, U. Language competence and language choice within EU institutions and their effects on national legislative authorities. In Exploring the Dynamics of Multilingualism. The DYLAN Project; Berthoud, A.-C., Grin, F., Lüdi, G., Eds.; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 157–177. [Google Scholar]

- Billiez, J.; Lucci, V.; Millet, A.; Degache, C.; Masperi, M.; Moussouri, V.; Varga, R.; Galligani, S.; Brissaud, C.; Tea, E.; et al. Une Semaine dans la vie Plurilingue à Grenoble, Rapport Ronéoté pour la DGLF; Délégation Générale a la Langue Française: Grenoble, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrósio, S.; Araújo e Sá, M.H.; Simões, A.R. Répertoire Plurilingue et contextes de mobilité: Relations et dynamiques. Cah. Int. Socioling. 2015, 1, 9–37. [Google Scholar]

- Faneca, R.M.; Araújo e Sá, M.H.; Melo-Pfeifer, S. Langues-Cultures d’Origine comme ressource pédagogique. Quels défis pour les enseignants? In Pour une Education Langagière Plurilingue, Inclusive et Ethique; Lörincz, I., Ed.; Universitas-Győr Nonprofit Kft: Győr, Hungry, 2019; pp. 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Billiez, J.; Lambert, P. Mobilités spatiales: Dynamique des repertoires linguistiques et des fonctions dévolues aux langues. In Mobilités et Contacts de Langues; Van Den Avenne, C., Ed.; L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2005; pp. 15–33. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy-Lejeune, E. Student Mobility and Narrative in Europe: The New Strangers; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kinginger, C. Langauge socialization in study abroad. In The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics; Chapelle, C.A., Ed.; Blackwell Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, S.; Irwin, E.; Freeman, H.; Nance, S.; Coleman, J. Building cultural and linguistic bridges: Reflections on a program designed to support adult students from refugee backgrounds’ transitions into university. J. Acad. Lang. Learn. 2018, 12, A64–A80. [Google Scholar]

- Beacco, J.-C.; Krumm, H.-J.; Little, D.; Thalgott, P. The Linguistic Integration of Adult Migrants. L’intégration Linguistique des Migrants Adultes; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, C. Professional work load and work-to-school conflict in working-students: The mediating role of psychological detachment from work. Psychol. Soc. Educ. 2018, 10, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, J.P. Da Abertura das Instituições de Ensino Superior a Novos Públicos: O Caso Português. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Lisbon, Portugal, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Correia, A.M.R.; Mesquita, A. Novos Públicos no Ensino Superior—Desafios da Sociedade do Conhecimento; Sílabo: Lisboa, Portugal, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bamber, J. Foregrounding curriculum: Ditching deficit models of nontraditional students. In Proceedings of the ESREA Annual Conference Access, Learning Careers and Identities Network, Seville, Spain, 10–12 December 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Finnegan, F.; Merrill, B.; Thunborg, C. Student Voices on Inequalities in European Higher Education. Challenges for Theory, Policy and Practice in a Time of Change; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- RANLHE Literature Review of the Project Access and Retention: Experiences of Non-traditional Learners in HE: Final Extended Version (August 2011). Available online: http://www.dsw.edu.pl/fileadmin/www-ranlhe/files/Literature_Review_upd.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2019).

- Vilhena, C. As transições para o ensino superior: Problemas e desafios atuais. In Estudantes não-Tradicionais no Ensino Superio; Fragoso, A., Valadas, S.T., Eds.; CINEP: Coimbra, Portugal, 2018; pp. 39–58. [Google Scholar]

- Valadas, S.T.; Fragoso, A.; Vilhena, C.; Conceição, M.C. Non-Traditional students transitions to higher Education. A case study in the University of Algarve. In Univers(al)idade. Estudantes «não Tradicionais» no Ensino Superior: Transições, Obstáculos e Conquistas; Marques, J.F., Martins, M.H., Doutor, C., Gonçalves, T., Eds.; Centro de Investigação sobre o Espaço e as Organizações (CIEO) e Universidade do Algarve: Faro, Portugal, 2016; pp. 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Markle, G. Factors influencing persistence among nontraditional university students. Adult Educ. Q. 2015, 65, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law-Decree, N. 64/2006, 21 March. Available online: http://www.mctes.pt/docs/ficheiros/M_23.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2012).

- Bamber, J.; Tett, L. Opening the doors of higher education to working class adults: A case study. Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 1999, 18, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrill, B. Gender and age: Negotiating and experiencing higher education in England. In Student Voices on Inequalities in European Higher Education: Challenges for Theory, Policy, and Practice in a Time of Change; Finnegan, F., Merrill, B., Thunborg, C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 74–85. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, J. Understanding working-class drop-out from higher education through a sociocultural lens: Cultural narratives and local contexts. Int. Stud. Sociol. Educ. 2004, 14, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallacher, J.; Crossan, B.; Field, J.; Merrill, B. Learning careers and the social space: Exploring the fragile identities of adult returners in the new further education. Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 2002, 21, 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasworm, C.E. Emotional challenges of adult learners in higher education. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 2008, 120, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.; Seary, K. I feel like I’m being hit from all directions: Enduring the bombardment as a mature-age learner returning to formal university. Aust. J. Adult Learn. 2011, 51, 119–142. [Google Scholar]

- González-Monteagudo, J.; Herrera-Pastor, D.; Padilla-Carmona, M.T. Abordagens biográfico-narrativas com estudantes universitários não-tradicionais. In Estudantes não-Tradicionais no Ensino Superior; Fragoso, A., Valadas, S.T., Eds.; CINEP: Coimbra, Portugal, 2018; pp. 51–77. [Google Scholar]

- Reay, D. We never get a fair chance: Working class experiences of education in the twenty-first century. In Class Inequality in Austerity Britain; Atkinson, W., Roberts, S., Savage, M., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Meehan, D.-C.-M.; Negy, C. Undergraduate students adaptation to college: Does being married make a difference? J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2003, 44, 670–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCune, V.; Hounsell, J.; Christie, H.; Cree, V.E.; Tett, L. Mature and younger students reasons for making the transition from further education into higher education. Teach. High. Educ. 2010, 15, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bowl, M. Experiencing the barriers: Non-traditional students entering higher education. Res. Pap. Educ. 2001, 16, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancola, J.K.; Grawitch, M.J.; Borchert, D. Dealing with the stress of college a model for adult students. Adult Educ. Q. 2009, 59, 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasworm, C.E. Setting the stage: Adults in higher education. New Dir. Stud. Serv. 2003, 102, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P.; Williams, J. For me or not for me? Fragility and risk in mature students decision-making. High. Educ. Q. 2001, 55, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannaday, F. Age and GPA of College Students. EDU 2030—Research Inquiry in Education; Salt Lake Community College: Salt Lake, UT, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fragoso, A.; Quintas, H.; Gonçalves, T. Estudantes não-tradicionais no ensino superior: Barreiras à aprendizagem e na inserção profissional. Lapl. Rev. 2016, 2, 97–111. [Google Scholar]

- Kasworm, C.E. Adult learners in a research university: Negotiating undergraduate student identity. Adult Educ. Q. 2010, 60, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.; Bago, J.; Baptista, A.V.; Ambrósio, S.; Fonseca, H.M.A.C.; Quintas, H. Academic success of mature students in higher education: A portuguese case study. Eur. J. Res. Educ. Learn. Adults 2016, 7, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, J.; Hammond, C. The motivations and outcomes of studying for part-time mature students in higher education. Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 2011, 30, 591–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrósio, S.; Araújo e Sá, M.H.; Pinto, S.; Simões, A.R. Perspectives on educational language policy: Institutional and students’ voices in higher education. Eur. J. Lang. Policy 2014, 6, 175–194. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, P.; Gallego Balsà, L. International universities and implications of internationalisation for minority languages: Views from university students in Catalonia and Wales. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2014, 35, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Soler, J.; Vihman, V.-A. Language ideology and language planning in Estonian higher education: Nationalising and globalising discourses. Curr. Issues Lang. Plan. 2017, 19, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).