Abstract

English-Medium Instruction (EMI) has become a central component of globalized education, allowing institutions to deliver courses in English to improve international competitiveness and accessibility for teachers and students. This paper reports the perspectives of five faculty members from a northern Taiwan private university who participated in an overseas short-term teacher training program at a Southern California State University, the United States, in 2025, aimed at enhancing their professional knowledge and teaching strategies in EMI. A qualitative research approach was adopted, including using the five semi-structured written open-ended questions and a focus group interview. This study captures insights of teachers into the professional development, instructional challenges, subject knowledge, language awareness, pedagogical shifts experienced, and self-reflection by these faculty members. Findings highlight the perceived impact of the professional development training on teachers’ language proficiency, pedagogical teaching skills in EMI, language awareness, intercultural communication competence, and the broader implications for EMI in Taiwanese higher education.

1. Introduction

In the face of globalization, English has become the most important language for international communication. From a policy perspective, building a bilingual environment is a key factor in enhancing national talent, industrial competitiveness, and international student mobility (Galloway & Rose, 2021), and it is essential for Taiwan’s integration into the global community. At the university level, institutions are not only responsible for cultivating talent capable of competing in the global job market but also for equipping the younger generation in Taiwan with a broader global perspective. This includes fostering an understanding of diverse international cultures and developing the ability to communicate and interact with people from different cultural backgrounds (National Development Council, 2022). In order to achieve this goal, English-Medium Instruction (EMI) serves as an effective tool to improve English competence for both teachers and students. As EMI becomes an increasingly prominent trend in global higher education, providing effective support for non-native English-speaking faculty has become essential. Accordingly, Taiwan’s Ministry of Education (MOE) announced that schools should provide an EMI Teaching Support System and enhance teachers’ EMI training (MOE, 2022). With the increasing proportion of EMI courses being offered, the teaching competence of faculty members without a background in Teaching English as Other Languages (TESOL) education is being put to the test. According to a recent survey, approximately 6900 full-time faculty members in local universities are capable of teaching courses entirely in English, accounting for about 18.62% of the total full-time teaching staff (MOE, 2022). Faculty members without a background in TESOL require support and professional training in order to provide a sufficient number of EMI courses in the future, while also enhancing teaching quality and fostering cross-disciplinary collaboration. Questions have been raised across multiple stakeholders concerning the existing frameworks for assessing and certifying teachers’ EMI teaching capabilities, as well as the mechanisms in place for their long-term professional development. This uncertainty underscores the need for systematic approaches to ensure both teaching quality and sustainable faculty growth in EMI contexts (Uehara & Kojima, 2021; Smit, 2023).

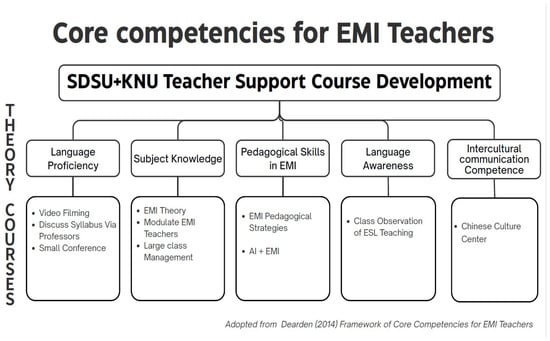

To address this need, Kainan University (KNU) in northern Taoyuan, Taiwan, has partnered with San Diego State University (SDSU) in southern California to implement a comprehensive EMI teacher training program. Teacher-support programs such as this have become crucial to equip non-native English-speaking faculty with the knowledge of KNU, which includes collaborating with SDSU to offer a comprehensive, short-term intensive EMI teacher professional development training program starting from the year 2024 to 2026. This study aimed to report the perspectives of faculty members who attended this program in 2025. During the discussion of this intensive course development, Dearden’s Core Competencies Framework for EMI Teachers of teacher professional development were adopted as the basic elements for designing this EMI teacher development program. There are many publications on EMI (e.g., Collins, 2010; Dafouz & Smit, 2020; Milne, 2014), but few have discussed EMI teachers’ support training and teachers’ needs. These are therefore the main foci of this paper.

2. Literature Review

2.1. EMI in Higher Education

The demand for EMI in non-native English-speaking countries has grown significantly in recent years (Macaro et al., 2018a). Research highlights that EMI programs can increase university prestige, enhance student language skills, and attract international students. However, EMI poses challenges, such as increased cognitive load for both students and teachers, and the need for teachers to adapt to new pedagogical approaches while teaching in English (Fenton-Smith et al., 2017; Walkinshaw et al., 2017). Additionally, studies suggest that teacher training is essential for effective EMI. Programs focusing on linguistic skills, pedagogical strategies, and cultural awareness can help faculty members overcome the complexities of EMI (Airey, 2016).

With the increasing proportion of English-medium courses in higher education, the teaching competence of faculty members without formal training in English language education has come under scrutiny. Research has highlighted that EMI instructors’ professional development (PD) is crucial for promoting high-quality student learning outcomes, leading to a growing number of EMI professional development programs worldwide across various academic fields (Huang et al., 2024). The expansion of EMI in higher education is not only cognitively taxing but also affectively contentious (Dang et al., 2023; De Costa et al., 2022; Hillman et al., 2023), as faculty are frequently compelled to adopt EMI under top-down pressures, often without sufficient training, resources, or social support, thereby raising questions about both its sustainability and its educational legitimacy.

In Taiwan, several national universities have established EMI teacher training and certification initiatives to strengthen faculty competence. Since 2024, the Resource Center for EMI at National Taiwan Normal University (RCEMI, NTNU) has partnered with the American Institute in Taiwan (AIT) to redesign its “English as a Medium of Instruction” courses, integrating AI technologies and expert guidance to support comprehensive development in speaking, reading, and writing. National Sun Yat-sen University (NSYSU) provides diverse workshops focused on effective oral communication and the use of generative AI to enhance students’ reading comprehension, while National Chung Hsing University (NCHU) promotes inter-university collaboration through course module development, peer observations, and quality assurance mechanisms.

International collaborations further support professional development. NTNU, in partnership with Columbia University Teachers College, offered a two-week intensive EMI program for 21 teachers from 12 universities across Taiwan, providing in-depth training in EMI teaching strategies and practices. Additionally, the University of Texas at Austin provides customized EMI training programs in collaboration with NTNU. Despite the increasing demand for EMI teacher certification, no unified standards currently exist in Taiwan, highlighting the need for standardized frameworks based on professional competence requirements to guide teacher training and certification.

However, while these initiatives demonstrate a growing awareness of EMI teacher development, there remains a lack of systematic research examining how faculty perceive and engage with these training programs, the effectiveness of existing professional development efforts, and the long-term impact on teaching quality. This gap underscores the need for empirical studies to evaluate EMI instructors’ experiences and to inform the design of more targeted and sustainable professional development frameworks in Taiwanese higher education.

Two pertinent areas of literature were deemed appropriate for this paper: (1) short-term professional development for EMI; and (2) challenges confronting EMI teachers in tertiary educational settings. Short-term professional training programs are of paramount importance for keeping teachers up-to-date on many of the newest trends in higher education. While EMI is not necessarily a new methodology, many teachers in non-English speaking countries (for whom English is not their primary language) are now being asked to teach curricular courses in EMI, creating a need for them to become well versed in the art and science of effective EMI teaching. To accomplish this, short-term professional development programs are being offered to improve the quality of instruction and learning in EMI.

2.2. Short-Term Professional Development Programs

Mena-Guacas et al. (2023) offered a comprehensive overview of various aspects of offering short-term courses for EMI teachers including learning methods, educational modality, content presentation, teaching methodology for teamwork and individual work, technological resources, and assessment methods (Al Zumor, 2019). Lockyer et al. (2005) offered 12 tips for short-term course design and implementation, including conducting a thorough needs assessment, clearly defining measurable learning outcomes, basing content on evidence and clinical guidelines, identifying and organizing necessary resources, selecting teaching strategies that promote active learning, structuring time and content appropriately, preparing effective learning materials and evaluation tools, assessing individual learner needs, orienting and supporting instructors, encouraging participants to commit to change, following up on those commitments, and using evaluation data to continuously improve the course.

Lauer et al. (2013) conducted a narrative literature review to identify the design features of effective short-term (30 h or less), face-to-face professional development events. The reviewed studies involved participants in education or human service-related professions. Design features associated with positive impacts of short-term professional development programs include sufficient time based on topic complexity, the use of learning objectives, alignment with participants’ training needs, demonstrations of desired behaviors, opportunities for participant practice, group discussions, pre-work and homework, active learning tasks that require cognitive processing, a participant-centered setting, and follow-up support to promote transfer of learning.

Karakaş and Kirkgoz (2025), editors of the book titled, Teacher Professional Development Programs in EMI Settings: International Perspectives, offer an international perspective on professional development in EMI along with practical guidance and innovative approaches for EMI teachers and trainers to enhance their practices. Yagiz and Aydin (2025), in their chapter titled “Understanding EMI Research and EMI Teachers’ Professional Development,” highlight the need for comprehensive training programs that go beyond language proficiency. They suggest incorporating pedagogical strategies, cultural awareness, and subject-specific challenges into professional development training programs.

Kamal et al. (2024) and Beaumont (2020) offered strategies for improving teacher training that include enhancing curriculum design and providing additional support for students struggling with EMI. They mentioned challenges such as language barriers among instructors, students’ insufficient English proficiency, difficulties in participating in class discussions, limited time for lecture preparation, and inadequate instructional materials. They also recommended a commitment to maintaining high-quality teaching and learning experiences by ensuring that instructors are well-versed in EMI.

Huang et al. (2024) stated that researchers have acknowledged that EMI instructors’ professional development (PD) is crucial for promoting high-quality student learning outcomes, resulting in an increasing number of EMI professional development programs worldwide across a variety of academic fields. Lastly, Fenton-Smith et al. (2017) focused on Taiwanese lecturers and their perceived needs in relation to short-term training in an overseas Anglophone locale.

2.3. Dearden’s Core Competencies Framework

The report of British Council, English as a Medium Instruction-A Growing Phenomenon, suggested that Dearden (2014) proposed a ‘core competencies framework for EMI teachers’ which provides a systematic analysis of the multifaceted skills required for instructors engaged in EMI in higher education. This framework emphasizes that EMI teachers not only possess a high level of English language proficiency, but also demonstrate effective pedagogical strategies, cultural adaptability, and emotional as well as psychological resilience to cope with multilingual and multicultural teaching contexts. Her study further identified several key challenges faced by EMI instructors, including language proficiency, subject knowledge, pedagogical skills in EMI, language awareness, and intercultural communication competence. Consequently, professional development for EMI teachers should address multiple dimensions, such as language enhancement, pedagogy, cultural adjustment, and emotional support (Wang et al., 2025). In addition, Dearden stressed that although EMI has rapidly expanded worldwide, there remains no unified standard regarding the competencies required of EMI instructors. This lack of consensus poses challenges for teacher professional development and certification. Therefore, the establishment of a clear competency framework and certification system is deemed essential for improving the quality of EMI instruction.

In sum, Dearden (2014) laid an important theoretical foundation for the professional development of EMI teachers by underscoring the integration of language proficiency, pedagogical strategies, cultural adaptability, and emotional support. Her work also called for the development of standardized competency benchmarks and certification mechanisms to ensure the enhancement of EMI education quality.

2.4. Challenges of EMI

As for challenges in implementing EMI, a growing number of language specialists, teacher educators, and institutions have actively designed and implemented EMI teacher development programs with the aim of strengthening teachers’ linguistic, pedagogical, and intercultural competencies (Bradford et al., 2024). One of the most frequently reported difficulties among EMI teachers is insufficient language proficiency. Although many instructors possess expertise in their academic disciplines, they often lack confidence in using English for extended academic discourse, managing classroom interactions, or explaining complex concepts with clarity (Hu & Lei, 2014; Werther et al., 2014). This language barrier can negatively impact both teaching effectiveness and student learning, especially in classes where students also have limited English proficiency. Beyond language issues, EMI teachers face pedagogical challenges, as traditional lecture-oriented approaches may not be sufficient to engage linguistically diverse learners. Research indicates that many instructors struggle to adapt teaching strategies to foster interaction, scaffold comprehension, and accommodate students’ varying linguistic needs (Macaro et al., 2018b; Dang et al., 2023).

Cultural and affective factors further complicate EMI teaching. Instructors frequently encounter intercultural communication challenges and experience identity conflicts, as teaching in English often disrupts their established teaching persona (Dearden, 2014; Galloway et al., 2020). Many also report feelings of stress and isolation, as institutional expectations to deliver EMI are seldom matched with adequate training or social support (Hillman et al., 2023). These challenges highlight the need for holistic approaches that go beyond language training, encompassing broader professional development and institutional reform.

To address these difficulties, scholars emphasize the necessity of comprehensive EMI teacher development programs. Language enhancement remains a foundational element, with discipline-specific training in academic English and classroom discourse strategies proving particularly effective (Werther et al., 2014). In addition, pedagogical workshops focusing on interactive, task-based, and student-centered methodologies help instructors move beyond traditional lecturing and better facilitate comprehension in EMI classrooms (Hu & Lei, 2014). Professional development opportunities such as microteaching, peer observation, and feedback cycles are especially useful in supporting practical teaching improvements.

Equally important is support for teachers’ cultural adaptability and emotional resilience. Building professional learning communities and inter-university teacher networks provides spaces for sharing resources and fostering collegial support (Dearden, 2014). Training programs that address affective dimensions, such as classroom anxiety and identity negotiation, have also been recommended to strengthen instructors’ psychological preparedness for EMI (Galloway et al., 2020). Furthermore, institutional policies must align with these developmental initiatives. Shifting from top-down mandates to inclusive, supportive structures—through workload adjustments, recognition, and incentives—can enhance teacher motivation and ensure the long-term sustainability of EMI programs (Dang et al., 2023).

In summary, EMI teachers face complex and interrelated challenges that span linguistic, pedagogical, cultural, and institutional domains. Addressing these issues requires not only targeted professional development but also systemic reforms that acknowledge teachers’ diverse needs. By investing in comprehensive frameworks that combine language support, pedagogical innovation, cultural training, and institutional recognition, universities can equip EMI instructors with the competencies required to deliver high-quality instruction and strengthen the legitimacy of EMI in higher education.

While examining teachers’ conversion from English for General Purposes (EGP) to English for Specific/Academic Purposes (ESP or EAP), Zhao and Li (2025) identified several challenges that are shared with EMI including emotional challenges, content knowledge challenges, course materials difficulty (such as developing students’ higher order thinking skills including critical thinking skills), syllabus design with related teaching materials, using various teaching methods, arranging learning activities, combining academic language and study skills, integrating language and subject knowledge, guiding students’ self-evaluation, and fostering student autonomy. Additional challenges were identified pertaining to students such as needs assessment, mixed disciplines background, low language proficiency and heterogenous backgrounds. Zhao and Li mentioned visiting scholar programs or overseas study programs as effective methods to transition from EGP to ESP/EAP that may also apply to EMI teachers.

Macaro and Aizawa (2024) reviewed research on EMI and ESP/EAP to investigate the overlap and divergences between these fields. They concluded that there is a distinction between these two types of English programs, with each having many of the same challenges, but further research needs to be done to elaborate on the differences and relevant pedagogical approaches.

In summary, faculty face numerous challenges in implementing EMI in their content-oriented courses and have a substantial need for professional development training in EMI along with pedagogical strategies to effectively teach using the EMI approach.

2.5. SDSU-Kainan University Collaboration

Kainan University (KNU) is one of the private universities in Taiwan that has received funding from The Program on Bilingual Education for Students in College (BEST) from the Ministry of Education (MOE) from 2024 to 2026, as part of its EMI policy. A teacher support training program aimed at providing teachers with knowledge of EMI and pedagogical skills was conducted to help them prepare future EMI courses. After implementing BEST project for the first year, we realized that teacher training was necessary to support instructors in offering EMI courses and to address the challenges they encountered in their teaching. We sought assistance from our sister university, SDSU, and organized an intensive teacher training program. The primary four objectives of the EMI teacher training program are enhancing language proficiency: improving instructors’ academic English skills to facilitate effective teaching; pedagogical development: introducing EMI-specific teaching strategies and methodologies to engage students effectively; cultural competence: fostering an understanding of cultural nuances to navigate diverse classroom environments and professional networking: building connections between Taiwanese and American educators to promote collaborative learning. SDSU has developed a tailored EMI professional development training program for KNU faculty, addressing the specific linguistic and pedagogical needs of Taiwanese teachers. This program combined workshops and Seminars, classroom instructions, classroom observations, peer observation, and reflective practice.

3. The Procedure of EMI Training Program at San Diego State University (SDSU)

3.1. Pre-Arrival Activities

The pre-arrival activities were to motivate teachers in their EMI teaching preparation and to prepare them for a western-style immerse learning environment. Prior to traveling from Taiwan to SDSU, KNU faculty recorded video introductions of themselves for viewing by the SDSU faculty team so that they would better know the KNU faculty who would be part of the EMI professional development training program. Additionally, a Google Meets online session was held including presentations by the SDSU L. Robert Payne School of HTM faculty and staff discussing the 10-day intensive program and fielding questions related to the proposed training program.

3.2. Follow-Up Activities

After returning to Taiwan, in order to support teachers with the challenges they may face in teaching, the researchers continued to invite the professors to hold monthly online meetings. These sessions not only help address teachers’ instructional issues but also offer a variety of topics from different perspectives. This allows teachers to engage in ongoing professional development while discussing with the professors, helping to reduce the stress and burden of teaching.

3.3. Onsite Program

The short-term professional training program for EMI at SDSU was basically designed as a holistic approach to EMI teaching. The training program immersed the KNU faculty in English-speaking settings during their entire time at SDSU. Other aspects of the training program entailed lectures and participatory course sessions on EMI, classroom pedagogy, the use of artificial intelligence in teaching EMI, and large class methodology; class observations of English as Second Language (ESL) teaching at SDSU’s American Language Institute; a visit to SDSU’s Chinese Cultural Center and interaction with their staff; presentations by the KNU faculty (in English) of their most favorite learning concepts; and introduction to various social settings aimed at usage of the English language. Daily learning sessions and experiences were provided during the intensive program.

3.4. Research Questions

To understand the impact and effectiveness of the program, this study aimed to address the following research questions:

- How do the teachers perceive the effectiveness of the PD program in enhancing their EMI professional competencies based on Dearden’s Core Competencies?

- What challenges and advantages do they encounter in applying these competencies in EMI contexts?

- How do teachers describe the influence of EMI training on their development and enactment of these competencies in classroom practice?

4. Methodology

A qualitative research approach was adopted to understand the experiences of the five (4 female, 1 male) KNU faculty members who participated in the SDSU EMI professional development training in 2025. Participants’ mean age was 46, with four in the 40-to-50-year-old age group, and one in the 30-to-40-year-old age group. In terms of their positions, three were assistant professors, while two were lecturers with master’s degrees. Informed consent letters were obtained from all the participants whose responses were used in this study. Table 1 shows the background information of the five KNU teachers who attended the program.

Table 1.

Background Information of the KNU Teachers.

KNU selects faculty members from various departments to participate in the program. The participating teachers were from four colleges including the School of Business, School of Informatics, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, and School of Healthcare Management and General Education. The university provides financial support to cover program fees, travel expenses, and accommodations, ensuring accessibility for a diverse group of instructors: two teachers with a Ph.D.; one with an Ed.D.; and two master’s degrees. Three teachers had taught at KNU for at least 15–20 years, and three had previous experience of teaching EMI courses. Three teachers did receive EMI certificates during 2024–2025, such as Cambridge EMI Skills or Oxford EMI Training certificates. More interestingly. most of them used 50–60% in their EMI classes instruction. None of teachers used 100% English in EMI classes (See Table 2).

Table 2.

Information about EMI teaching experience.

4.1. Ten-Day Intensive Training Course Development

This Ten-Day Intensive Training Course Development adopted Dearden’s (2014) Core Competencies Framework for EMI Teachers for teacher professional development as the basic elements. It focused on language proficiency, subject knowledge, EMI pedagogical skills, language awareness, and intercultural communication competence (see Figure 1). This program was designed to support KNU teachers of preparing in implementing EMI in their future teaching.

Figure 1.

Core Competencies Framework for EMI Teachers from Dearden (2014).

4.2. Instruments

Data collection was conducting using a semi-structured written open-ended question, as well as focus group interviews. The questionnaire and written open-ended questions were in English, and the interviews were conducted in English. In order to avoid any bias, the questionnaires were edited by three native English speakers and two non-native speakers who checked the meaning of each item.

The semi-structured written open-ended questions covered topics such as the participants’ motivations for attending the program, challenges encountered, instructional shifts, and the perceived impact on students. Additionally, the focus group interview took 30 min per time, and three times the total. The Interview used both Chinese and English to avoid the misunderstanding the meaning of questions. Interviews asking five open-ended questions provided another opportunity for the five teachers to express their perceptions of the professional development training. In designing and planning the interview questions, the researchers also paid attention to the teachers’ mindsets during the teacher training process. For example, within the ‘Professional Development’ section, teachers were asked what they considered the most valuable aspect of the training. The interviewer assisted the teachers in reflecting on their thoughts from the initial preparation and application stage through to the completion of the program. During this process, we called ‘prepared’ status. Also, there are two questions focusing on ‘After Training’ status (See Appendix A).

4.3. Data Analysis

The interview transcripts were analyzed using thematic analysis. Through careful reading of the transcripts, important excerpts or keywords were initially coded, and then similar meanings or content were categorized into themes. If any issues arose during the process, clarification was sought from the instructors via Line or other messaging applications.

5. Findings and Discussion

5.1. Research Question 1

Five teachers showed strong support for the training program experience at SDSU. Teacher responses regarding Teachers Perceive the EMI Training at SDSU. Overall, participating teachers perceived the program as being a highly valuable and professional development experience. Several key themes based on Dearden’s core competence emerged from analysis of their responses, as follows.

- Language Proficiency

Most participants, when facing English-Medium Instruction (EMI), tend to approach their own language proficiency with caution and self-reflection. Two participants mentioned that although they possess adequate English communication and reading skills, they still feel pressure when it comes to spontaneous expression, classroom guidance, or responding to students’ questions in class. They believe that EMI challenges not only language proficiency but also the ability to manage teaching pace and classroom interaction. One teacher noted, “When teaching a professional subject in English, I have to think about the content, the language, and the students’ comprehension all at once—it’s more challenging than I expected.” All teachers also pointed out that improving English proficiency is an ongoing process that can be strengthened through reading international literature, observing foreign instructors’ teaching, and participating in language training. Overall, teachers generally agree that EMI has prompted them to reexamine their own language use and teaching strategies, motivating them to continuously enhance their English fluency and intercultural communication competence. While three participants found the training helpful, several expressed a desire for more targeted support for English language skills, particularly speaking, writing, and presentation. Enhancing these competencies was viewed as essential for improving their confidence and effectiveness in EMI settings.

“At first, I was actually worried that my English wouldn’t be fluent enough. But since these 10 days intensive training gave me observe the ESL classes, practice in simplifying instructions, and sharing the small conference, when I tried it in my Informatics Management class, students were able to understand my directions more quickly. This boosted my confidence and encouraged me to think about designing more activities conducted in English.”(Three interviewees)

- 2.

- Subject Knowledge

In implementing EMI in higher education, teachers face not only challenges in language proficiency but also difficulties in accurately conveying subject knowledge. four teachers have pointed out that, although they possess solid expertise in their fields, their ability to express subject-specific terminology or complex concepts in English is often insufficient. This can result in explanations that are not precise, potentially affecting students’ comprehension. Furthermore, teachers need to spend additional time searching for appropriate English resources and materials during lesson preparation, which increases their workload. This situation not only affects teaching fluency but may also undermine teachers’ confidence in the classroom, thereby impacting the overall effectiveness of EMI.

“Through the EMI practice, I started paying more attention to how to explain professional knowledge in English in a simpler way. After doing that in my Tourism and Hospitality Management course, students gave feedback that it was easier to follow the course, which made me feel a real sense of achievement.”(Two Interviewee)

- 3.

- Pedagogical Skills in EMI

All Participants consistently noted the usefulness of Bloom’s Taxonomy for improving lesson design and promoting higher-order thinking skills during the training session. Three teachers mentioned being inspired to transition from teacher-centered to learner-centered teaching approaches. They also valued the exposure to syllabus design examples and scaffolding techniques shared by the instructors.

Three teachers appreciated the program’s strong emphasis on hands-on learning, classroom observation, and real-world teaching practices. Observing classes at the American Language Institute, especially those involving community engagement or language instruction, allowed participants to gain authentic insights into student-centered pedagogy and interactive teaching methods. The opportunity to apply theoretical knowledge in practical contexts was highlighted as being particularly beneficial.

“In the past, I often felt that most of students were reluctant to speak in my class. But this semester, after I added small group discussions, they were much more willing to communicate in English. Their word usages and grammar were not always accurate, but I think the key point is that they were willing to speak up. This made me realize that EMI methods are quite effective.”(One Interviewee)

- 4.

- Language Awareness

The participants generally reported that the training significantly enhanced their understanding and awareness of Language Awareness. Through a combination of theoretical instruction and practical exercises, they became more conscious that language is not only a medium of teaching but also a vehicle for thought and culture. They learned to identify and analyze variations in language use in the classroom, enabling students in understanding meaning, pragmatics, and cultural context in a more inclusive and strategic manner. Many teachers expressed that the program prompted them to reflect on their own linguistic roles and to place greater emphasis on developing students’ language awareness when designing lesson plans—ultimately contributing to a more effective English learning environment.

“I learned that it’s important to help students notice how language is used, rather than just teaching grammar or vocabulary. This has made me place greater emphasis on context and communicative intent when designing my lessons.”(Three interviewees)

- 5.

- Intercultural Communication Competence

Teachers face not only challenges in language proficiency and subject knowledge but also significant demands in intercultural communication competence. All teachers have reported that during classroom interactions, cultural differences can lead to misunderstandings or communication difficulties due to insufficient understanding of students’ communication styles, learning habits, and ways of thinking. For example, attitudes toward discussion, questioning, or critical thinking may vary across cultures. If teachers do not appropriately adjust their teaching strategies, it may affect students’ engagement and learning outcomes. Furthermore, in intercultural contexts, teachers should balance language clarity with cultural sensitivity, which undoubtedly increases the complexity of classroom management and instructional design. Two teachers praised the supportive atmosphere created by the SDSU faculty, especially Professor Gene and other instructors. Personal interactions, encouragement, and even letters of support were described as deeply motivating and memorable. The combination of academic rigor and human connection contributed to a strong sense of professional and personal growth (Two interviewees).

5.2. Research Question 2

The second research question aimed to understand the challenges and advantages the teachers encounter in applying these competencies in EMI contexts. To summarize the teachers’ perceptions of EMI teaching, the study first collected their open-ended responses regarding both the challenges and advantages they experienced. Each response was categorized into thematic groups and then ranked according to the frequency of mention and perceived importance reported by the teachers. Since EMI has caused stress, anxiety, and tension, several teachers mentioned that they did not receive the appropriate teacher training before they were assigned to teach EMI classes. Moreover, for the challenges, the most frequently mentioned issue was teachers’ language abilities, followed by students’ language abilities, EMI teaching strategies, low teaching evaluations, and students’ low motivation. In contrast, the advantages were ranked by perceived benefits, with extra payment for EMI teaching being the most recognized, followed by improvement in English teaching competence, attracting more students, adding value to teaching evaluations, and contributing to long-term career development. This ranking method allowed the study to systematically identify the areas that require institutional support as well as those that motivate teachers to continue engaging in EMI instruction (See Table 3).

Table 3.

A summary of the challenges and advantages teachers perceived in EMI teaching.

One of the most prominent challenges reported by participants was their own language proficiency. Five teachers emphasized that using English to explain complex academic concepts often generated stress, anxiety, and additional preparation workload. Sometimes, even when teachers tell jokes or share stories in class, it is still difficult to resonate with students. In many cases, teachers needed to spend double or even triple the usual amount of time preparing EMI course materials to ensure clarity and accuracy.

“Honestly, speaking English for the entire class makes me nervous, especially when students ask spontaneous questions. Sometimes I can’t think of the right words immediately, and that makes me feel anxious. I also notice that my jokes or small talk don’t get much reaction—students smile politely, but I can tell they don’t really connect. That creates a bit of distance between us.”

“When I tell stories or use humor in English, students don’t respond the way they do in Chinese. I think part of it is cultural, but part of it is my language delivery. It makes me feel less confident. To overcome that, I’ve started to practice storytelling in English before class, but it still feels a bit forced. EMI teaching definitely pushes me to go beyond my comfort zone.”(Five interviewees)

Apart from teachers ‘language abilities, students limited English proficiency was also noted as a barrier, as it sometimes hindered comprehension and reduced classroom interaction. Teachers further mentioned difficulties in adopting effective teaching strategies for EMI classes. The reason is most of teachers were not TESOL background, it was hard for them to use the teaching pedagogy or activities to motivate students. In addition, teachers expressed concerns about receiving lower teaching evaluations when students struggled to adapt. A lack of student motivation in EMI classes was also viewed as a recurrent obstacle (Three interviewees).

“I don’t have a TESOL background, so when I first taught EMI, I wasn’t sure what kinds of activities could engage students effectively. I tried some group discussions, but students didn’t talk much because they lacked confidence in English. I later realized I needed to simplify tasks and give more language support, but that also took a lot of preparation time. Honestly, it’s a trial-and-error process for me.”

Despite these challenges, teachers recognized several meaningful advantages. Financially, some appreciated the extra payment associated with EMI courses. Professionally, EMI was seen as a valuable opportunity to improve their own English teaching competence, enrich their portfolios, and enhance long-term career development. Teachers also observed that EMI could attract more students to their courses, thereby raising their visibility within the institution. (Three interviewees)

“For me, EMI is a great way to improve my own English teaching ability. I’ve become more aware of my language use and how to explain complex ideas clearly in English. Over time, I’ve also gained confidence and built up more international-style materials for my teaching portfolio. I feel this experience will be beneficial for my long-term career development.”

Finally, many acknowledged that successful EMI teaching contributed positively to their teaching evaluations. Overall, while EMI presented undeniable challenges in terms of language demands and instructional adjustments, participants agreed that it also offered significant professional and institutional benefits. (Three interviewees)

“After I started teaching EMI, I actually noticed an improvement in my teaching evaluations. I think students appreciate the effort I put into designing bilingual-friendly materials and making lessons more international. It’s very rewarding to see that my hard work is being recognized both by students and by the school administration.”

“At first, I was worried EMI might lower my evaluations because of students’ language difficulties. But surprisingly, the feedback turned out quite positive. Many students mentioned that they enjoyed the new learning experience, and that it helped them feel more confident using English. That really encouraged me to keep refining my EMI teaching methods.”

“Even though EMI teaching requires more preparation and energy, I can see how it benefits me professionally. It not only improved my own English and teaching strategies, but also enhanced my reputation in the department. The university seems to value teachers who can successfully handle EMI, so it feels like an investment in my long-term academic career.”

5.3. Research Question 3

Five teachers expressed that this training program refreshed their pedagogical strategies and also reflected some different aspects of their teaching, such as increased language awareness, use of scaffolding, shift to a student-centered approach, provision of language support, and reflective teaching. The 10 days intensive program not only refreshed pedagogical strategies but also prompted teachers to reflect on multiple aspects of their classroom practices. First, several participants reported increased language awareness, as they became more conscious of simplifying vocabulary and clearly explaining key terminology. This content adjustment helped ensure greater in students’ comprehension. Second, teachers described adopting more scaffolding techniques, such as using AI plus visuals and dividing lectures into smaller, manageable chunks, which supported students’ understanding of complex content. Another significant outcome was a stronger shift emphasis on teacher-centered approach to a student-centered approach. Inspired by their observation of classes at the American Language Institute (ALI), teachers began allocating more time for group discussions and interactive activities, shifting away from the traditional lecture-dominated model common in Taiwan. Moreover, all participants emphasized the importance of offering language support, such as classroom language, including sentence starters and keywords to guide student participation in English discussions. Finally, EMI training encouraged reflective teaching practices, with teachers reporting that they now paused more frequently to check students ‘understanding and adjusted their instruction accordingly. Collectively, these insights suggest that EMI training had a transformative influence, equipping teachers with both practical tools and reflective habits to enhance student engagement and learning outcomes (See Table 4).

Table 4.

Thematic Analysis of Impacts on Teaching Methods.

5.4. Limitations of the Study

This study is subject to several limitations that should be acknowledged when interpreting the findings. First, the sample size was small, involving only five faculty members from a single private university in northern Taiwan. The limited number of participants restricts the generalizability of the results and may not fully represent the diverse EMI teaching experiences across different higher education institutions in Taiwan. Second, the data were collected through semi-structured written responses and a focus group interview, which rely heavily on participants’ self-reported perceptions. Such data may be influenced by personal bias, selective memory, or participants’ willingness to share certain experiences. Third, the professional development program took place over a short period at a university in Southern California, meaning that the insights captured reflect impressions from a specific training context rather than long-term changes in teaching practices. Finally, as this study adopted a purely qualitative approach, it does not incorporate quantitative measures of teaching performance or language proficiency improvement, which could have offered a more comprehensive evaluation of the program’s impact. Future studies involving larger participant groups, multiple institutions, longitudinal designs, and mixed-methods approaches would strengthen the understanding of EMI professional development outcomes in Taiwanese higher education.

6. Conclusions

The perceptions of the five KNU faculty members underscore the significant and positive impacts of the EMI training program at SDSU. Teachers consistently mentioned that this teacher training program enhanced their confidence in preparing the EMI professional content and equipped them with practical EMI pedagogical strategies. The Ministry of Education (MOE, 2022) stated that moving forward, it continues to steadily promote the bilingual education program under the principles of “teachers being well-prepared,” “schools providing support,” and “consensus among participating teachers and students,” in order to create an internationalized teaching environment for colleges and universities.

Specifically, they highlighted gains in language awareness, the use of scaffolding techniques, a shift from a teacher-centered approach to a student-centered approach, provision of language support, and the adoption of reflective teaching practices. These shifts not only refreshed their instructional methods but also encouraged them to rethink how they could foster greater engagement and comprehension in EMI classrooms.

Despite these advances, challenges remain. Teachers acknowledged ongoing struggles with their own language proficiency, the additional time needed to prepare EMI materials, and the difficulty of maintaining student motivation. Nevertheless, they also emphasized the substantial advantages of EMI teaching, such as opportunities for professional growth, improvements in teaching portfolios, and greater career development potential. Moreover, exposure to the student-centered practices observed at the ALI broadened their perspectives, motivating them to integrate more interactive methods into their courses.

Teachers also valued the comprehensive approach of the SDSU program, which balanced pedagogical training with opportunities to enhance their English skills in authentic contexts. The introduction of digital tools such as Gemini, Canva, and Deep Paper further expanded their repertoire of classroom strategies. In sum, participants felt that the EMI training was not only beneficial but also transformative, paving the way for greater internationalization at KNU. Future studies could include a larger pool of participants and examine the long-term effects on teaching efficacy and student learning outcomes, thereby contributing to the ongoing development of EMI in Taiwan.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.-Y.Y. and G.L.; methodology, J.-Y.Y.; software, G.L.; validation, J.-Y.Y. and G.L.; formal analysis, J.-Y.Y.; investigation, J.-Y.Y.; resources, G.L.; data curation, J.-Y.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, J.-Y.Y.; writing—review and editing, J.-Y.Y.; visualization, J.-Y.Y.; supervision, G.L.; project administration, G.L.; funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, the participants are school teachers, and the research methods include questionnaires and interviews. During the interview process, all participating teachers signed a consent form. The study does not involve any human experiments or potentially hazardous procedures such as drug treatments.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Interview Questions for Teachers.

Table A1.

Interview Questions for Teachers.

| Core Competence | Questions | Status |

|---|---|---|

| Professional Development | 1. What was the most valuable aspect of the training for you? | Prepared |

| Pedagogical Skills in EMI | 2. What is the first strategy or technique from the training that you plan to implement in your teaching? | Training Improvement Teaching Strategy |

| Subject Knowledge | 3. Were there any topics or areas that you feel needed more focus or improvement? | Training Improvement Content |

| Language Awareness | 4. If you could change or add anything to the training program, what would it be? | After Training |

| Self-Reflection | 5. Do you have any additional comments or suggestions? | After Training |

References

- Airey, J. (2016). EMI and the challenges of teaching in English: A review of recent literature. Language Teaching, 49(3), 377–389. [Google Scholar]

- Al Zumor, A. (2019). Challenges of using English medium instruction (EMI) in teaching and learning of university scientific disciplines: Student voice. International Journal of Language Education, 1, 74. Available online: https://ojs.unm.ac.id/ijole/article/view/7510 (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Beaumont, B. (2020). Identifying in-service support for lecturers working in English medium instruction contexts. In M. Carrió-Pastor (Ed.), Internationalising learning in higher education. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, A., Park, S., & Brown, H. (2024). Professional development in English-medium instruction: Faculty attitudes in South Korea and Japan. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 45(8), 3143–3157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A. B. (2010). English-medium higher education: Dilemma and problems. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 10, 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Dafouz, E., & Smit, U. (2020). ROAD-MAPPING English medium education in the internationalised university. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, T. K. A., Bonar, G., & Yao, J. (2023). Professional learning for educators teaching in English-medium-instruction in higher education: A systematic review. Teaching in Higher Education, 28(4), 840–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearden, J. (2014). English as a medium of instruction—A growing global phenomenon. British Council. [Google Scholar]

- De Costa, P. I., Green-Eneix, C. A., & Li, W. (2022). Problematizing EMI language policy in a transnational world: China’s entry into the global higher education market. English Today, 38(2), 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton-Smith, B., Stillwell, C., & Dupuy, R. (2017). Professional development for EMI: Exploring Taiwanese lecturers’ needs. In I. Walkinshaw, B. Fenton-Smith, & P. Humphreys (Eds.), English-medium instruction in higher education in Asia-Pacific (pp. 195–217). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, N., Numajiri, T., & Rees, N. (2020). The ‘internationalisation’ or ‘Englishisation’ of higher education in East Asia. Higher Education, 80(3), 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, N., & Rose, H. (2021). English medium instruction and the English language practitioner. ELT Journal, 75(1), 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, S., Li, W., Green-Eneix, C., & De Costa, P. I. (2023). The emotional landscape of English medium instruction (EMI) in higher education. Linguistics and Education, 75(3), 101178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, G., & Lei, J. (2014). English-medium instruction in Chinese higher education: A case study. Higher Education, 67(5), 551–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., Lin, L.-C., & Tsou, W. (2024). Leveraging ESP teachers’ roles: EMI university teachers’ professional development in medical and healthcare fields. English for Specific Purposes, 74, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, S., Bhuiyan, M. M. R., & Khatun, M. (2024). Striking a balance: Challenges and strategies in implementing English medium instruction (EMI) in a non-anglophone higher education context. ICRRD Journal, 5(3), 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakaş, A., & Kirkgoz, Y. (2025). Teacher professional development programs in EMI settings: International perspectives. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lauer, P., Christopher, D., Firpo-Triplett, R., & Buchting, F. (2013). The impact of short-term professional development on participant outcomes: A review of the literature. Professional Development in Education, 40, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockyer, J., Ward, R., & Toews, J. (2005). Twelve tips for effective short course design. Medical Teacher, 27(5), 392–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macaro, E., & Aizawa, I. (2024). English medium instruction, EAP/ESP: Exploring overlap and divergences in research aims. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 34(4), 1352–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaro, E., Curle, S., Pun, J., An, J., & Dearden, J. (2018a). A systematic review of English medium instruction in higher education. Language Teaching, 51(1), 36–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaro, E., Tian, L., & Chu, L. (2018b). First and second language use in English medium instruction contexts. Language Teacher Research, 24(3), 382–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena-Guacas, A. F., Chacón, M. F., Munar, A. P., Ospina, M., & Agudelo, M. (2023). Evolution of teaching in short-term courses: A systematic review. Heliyon, 9(6), e16933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, E. D. (2014). Towards a dynamic conceptual framework for English-Medium Education in multilingual university settings. Applied Linguistics, 37, 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education, Republic of China (Taiwan). (2022). The program on bilingual education for students in college: Focused development and generalized enhancement for English-Medium Instruction. Ministry of Education, Republic of China.

- National Development Council. (2022). Bilingual 2030: Blueprint for developing Taiwan into a bilingual nation by 2030. National Development Council, R.O.C. (Taiwan). Available online: https://www.ndc.gov.tw/en/Content_List.aspx?n=BF21AB4041BB5255 (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Smit, U. (2023). English-medium instruction (EMI). ELT Journal, 77, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uehara, T., & Kojima, N. (2021). Prioritizing English-medium instruction teachers’ needs for faculty development and institutional support: A best–worst scaling approach. Education Sciences, 11(8), 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkinshaw, I., Fenton-Smith, B., & Humphreys, P. (2017). EMI issues and challenges in Asia-Pacific higher education: An introduction. In I. Walkinshaw, B. Fenton-Smith, & P. Humphreys (Eds.), English-medium instruction in higher education in Asia-Pacific (pp. 1–18). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K., Yuan, R., & De Costa, P. I. (2025). A critical review of English medium instruction (EMI) teacher development in higher education: From 2018 to 2022. Language Teaching, 58(2), 141–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werther, C., Denver, L., Jensen, C., & Mees, I. M. (2014). Using English as a medium of instruction at university level in Denmark: The lecturer’s perspective. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 35(5), 443–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagiz, O., & Aydin, B. (2025). Understanding EMI research and EMI teachers’ professional development. In A. Karakaş, & Y. Kirkgoz (Eds.), Teacher professional development programs in EMI settings: International perspectives. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L., & Li, Y. (2025). English language teachers transitioning from English for general purposes to English for specific/academic purposes: Challenges and professional development. ESP Today, 13(2), 268–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.