Abstract

A theoretical model of learning is proposed which is grounded in the constitutive role of interpersonal relationships, integrating contributions from early developmental psychology and relational philosophy. Using a Theoretical Educational Inquiry approach, the study critically examines dominant competency-based and cognitivist models, identifying their inability to account for learning as a deep personal transformation. Drawing on authors such as Stern, Trevarthen, Hobson, Winnicott, and Kohut, it presents empirical evidence that the self and cognitive-affective capacities emerge within primary relational bonds. However, interpersonal relationships are not the environment where development occurs, but the end towards which it is oriented: if the relational bond is the point of departure, the interpersonal encounter is the telos shaping the whole process. The child’s engagement with inner and outer worlds is driven by the search for such encounter, irreducible to mere relational pleasantness, although this may indicate its realization. Philosophical perspectives from Polo, Levinas, Buber, Whitehead, Spaemann, and Marcel support the understanding of learning as a relational event of co-constitution. Learning implies cycles of crisis and reintegration. This approach shifts the focus from skill acquisition as an end to using it as a means for fostering meaningful interpersonal relationships, thereby reorienting education towards a dignity-centered paradigm.

1. Introduction

The history of pedagogy reflects an oscillation between different approaches that have sought a basis for educational praxis. Originally, education, based on philosophical anthropology, was conceived as an essential mediation for human beings to reach their fullness (Comenius, 1997; Rousseau, 2005; Pestalozzi, 1998). A holistic and ethical understanding of education was thus sought which would articulate an integral formation of the human being encompassing character, reason, sensitivity and freedom (Wulf, 2024). During the nineteenth century, figures such as Herbart, Nohl, Litt or Spranger avoided a purely psychological approach to education in order to maintain its formative and anthropological ethical reference (Dewey, 1909; Herbart, 1935; Nohl, 1949; Friesen, 2017).

However, the rise of experimental psychology, with behaviourist and cognitivist paradigms (Thorndike, 1898; Skinner, 1974; Piaget, 1975; J. S. Bruner, 1960; Ausubel, 1963), led to a functional view of education, which reduced it to an effective technology of knowledge acquisition (Wulf et al., 2002; Dewey, 1938; Friesen, 2017). In response to this, Freire (1996) advocated a relational, dialogical and transformative pedagogy, a perspective reaffirmed by contemporary educational anthropology (Wulf, 2024; García Hoz, 1975; Meirieu, 2001) and by approaches that incorporate complexity and meaning from a dialogue with philosophy (Mandavilli, 2018; Morín, 2001). This reflects the struggle to avoid the technification of learning and to preserve its character of personal growth, in accordance with anthropological and ethical referents.

Today, however, a technical vision of learning seems to dominate. The predominant models, based on competences or cognitive processes, omit the original relational dimension of learning by failing to consider its anthropological and ethical weight. In these models, the relationship is viewed as instrumental, sometimes in a circumstantial way and other times as essential. In all cases, interpersonal relationships are put at the service of learning and not the other way around. Moreover, these models deal separately with knowledge of the world, of oneself and of others as if they were independent of each other.

The model proposed in the present article, based on the development of the child in the first five years of life, recovers the anthropological and ethical framework of learning which informs the works of psychologists such as Stern (1998, 2004, 2010), Trevarthen (1998, 2001, 2009), Hobson (2002), Winnicott (1990, 2005) or Kohut (2009). Their proposals call for an anthropological framework in which interpersonal relationships are constitutive of who we are, rather than an accidental or conjunctural element. We are born in intrinsic relation and oriented towards interpersonal encounter. Furthermore, knowledge of the world, the other and oneself are intrinsically and necessarily interrelated (Polo, 1999, 2003, 2005; Buber, 1998, 2001, 2006; Levinas, 2000, 2002).

The aim of this paper is to formulate a theoretical model of learning which integrates the psychological and philosophical dimensions in order to rethink learning as a constitutive experience of the subject through the bond, rather than as the acquisition of individual competences. The Theoretical Educational Inquiry approach (Biesta, 2006; Matusov et al., 2019), which combines integrative, critical and argumentative reviews (Grant & Booth, 2009), is used to define a model of learning that goes beyond the predominant individualistic view.

The proposed model redefines learning as a personalising and co-constitutive event, driven by the desire for encounter and sustained by trust, recognition and the presence of the educator; these being ontological conditions for development. This perspective broadens the horizons of educational theory towards a pedagogy centred on dignity, meaning and the constitutive relationality of the human being.

The paper has the following structure: after this introduction (Section 1), Section 2 describes the methodology adopted, explaining the framework of the Theoretical Educational Inquiry and the criteria for the selection of the theoretical corpus. Section 3 presents the delimitation of the theoretical problem, critically analysing the dominant learning models and their limitations when they come to explain the relational dimension of human learning. On this basis, Section 4 develops the rationale for the new model, integrating contributions from early developmental psychology and relational philosophy. Section 5 systematically sets out the structure of the proposed model, its guiding principles and the dynamics of cycles of crisis and reintegration that characterise it. Section 6 presents the discussion and contrast with other approaches, as well as the epistemological and pedagogical implications. Finally, Section 7 offers the general conclusions, synthesising the findings in a proposal on how to understand the learning objectives, together with a work methodology and an evaluation congruent with the model, concluding with possible future lines of research and theoretical development.

It might be objected that a model of learning based on child development from 0–5 years of age is not valid for later stages. However, we argue that the study of children’s learning in this age range offers a more direct access to human nature, before cultural structures lead to the rigidity characteristic of adult life. This premise is shared by researchers from several disciplines: Tomasello’s (1999, 2008) evolutionary anthropology uses the observation of the young child to explain the cooperative roots of cognition; psychoanalysists have also prioritised this period to explore the psychic constitution.

We argue that the proposed model of learning, being anchored in human nature, pervades the whole of life. The Learning based on Constitutive Relationality model integrates classical and current models into a broader framework—the person and their relationships—and is open to further enrichment from other approaches. Thus, for example, Piaget’s findings on the increasing complexity of thinking with age are regarded here as being integral to the whole natural development of the human being. This enables the proposed model to welcome criticisms of Piaget on the part of the theorists of complex dynamical systems, who accuse him of reducing the variables of complexity and disregarding the dynamic nature of the interaction between them (Smith, 2005; Thelen & Smith, 1994). This model also welcomes criticism of Piaget on the part of Donaldson (1987), who questions the supposed egocentrism of children by demonstrating that, in relational and naturalistic contexts, the competences attributed by Piaget to certain ages emerge several years earlier. Donaldson showed that Piaget’s error lies in conceiving cognitive abilities as separate from relational conditions, by disregarding factors such as intentionality, agency, expectations derived from previous experiences, meaning of the task for the relationship or the tone of voice in which the task is given.

This search for making the new model compatible with the existing ones is in line with Stern (1998), who stresses that the child’s development does not involve a succession of learning modes that replace the previous ones, but rather the integration of the new learning modes with the previous ones (p. 30). Pointing to the weight of quality interpersonal relationships in all aspects of life as a powerful, fundamental and extremely omnipresent motivation (Baumeister & Leary, 1995), we propose a learning model which should always be present, i.e., a model which can coexist in a coherent way with other learning models. This endeavour to give learning its most global framework is not a new concern. In fact, some of the classical learning models are not reduced to the focus of the research in question, but often have a much broader framework. For example, Piaget’s proposal cannot be reduced to a purely cognitivist paradigm. Sroufe (2002, pp. 40–41, 117) points out that, for Piaget, emotion and cognition are ‘nondissociable’. Moreover, this work is in line with Piaget himself who expressed the wish that child logic could one day explain adult logic and prevent adult prefabricated paradigms from being imposed on what happens in the child (Piaget, 1951, p. 91).

Lack of social relationships and interpersonal encounters is known to be a major predictor of death, as revealed by a meta-analysis which included over 300,000 people with results independent of age, sex, initial health status, cause of death or length of study period (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010). Along the same lines, a still open study, which began in 1938 and conducts a follow-up assessment of generations, shows that the quality of interpersonal relationships is the most important determinant of a happy and healthy life, regardless of initial health status, economic resources, employment status, etc. (Waldinger & Schulz, 2010). If the presence of quality interpersonal relationships is the greatest predictor of a successful life, and their absence is the greatest predictor of death, does it not seem logical that learning should also be placed at the service of making such quality interpersonal relationships a reality? All this is also consistent with the UNESCO international report on what is expected of education today, which explicitly states that learning to be, learning to learn and learning to do acquire sense by (and are oriented towards) learning to live together (Delors et al., 1996).

We propose the term Learning based on Constitutive Relationality (LBCR) to designate this new model, which understands education as a personalizing and co-constitutive event in which learning arises not from the dialectical overcoming of differences but from the interpersonal encounter—conceived as a dialogical space in which the self is constituted through relationship. The term Learning based on Constitutive Relationality designates a model that, drawing on empirical findings from developmental psychology (Stern, Trevarthen, Hobson, Winnicott, Kohut), shows that the self and the cognitive-affective capacities emerge within primary interpersonal bonds rather than in isolation. Relationality is therefore not an accessory but the very condition of possibility for learning. This model differs both from relational learning, which in educational literature usually refers to pragmatic strategies for cooperation or classroom climate, and from dialectic learning, in the Hegelian–Vygotskian tradition, which conceives differences as contradictions to be overcome in a higher synthesis. By contrast, Learning based on Constitutive Relationality affirms difference as constitutive of meaning and growth, and situates education within a dialogical space where the self is formed through encounter with the other. Philosophical perspectives from Polo, Buber, Levinas, Marcel, Spaemann, and Whitehead provide the ontological and ethical framework that grounds these psychological insights, reconfiguring learning as a personalizing and co-constitutive event, irreducible to cognitive or instrumental frameworks.

2. Methodology

The introduction of a new comprehension of learning requires ensuring its scientific legitimacy, theoretical coherence, and positioning it within the corpus of knowledge. The resource which guarantees this is a solid and rigorous theorising. This research adopts the theoretical educational inquiry paradigm (Biesta, 2006; Matusov et al., 2019) as its methodological approach. As such, this theoretical educational research is not limited to applying or testing previous constructs, but seeks to generate a new understanding of the learning process through rigorous conceptual elaboration. This methodology falls within the scope of conceptual theoretical elaboration grounded in a psychological-philosophical corpus of early human development.

In order to construct our learning model based on early psychological development and the constitutive nature of the interpersonal relationships, our theoretical educational inquiry paradigm is developed by combining three clearly identifiable types of review: integrative, critical, and argumentative. The integrative review enables us to interweave contributions from various philosophical and psychological traditions; the critical review provides an analysis of the ontological and epistemological assumptions of current models; and the argumentative review structures the theoretical selection on the basis of a thesis which seeks to overcome the dominant individualistic approach to understanding human learning (Grant & Booth, 2009).

This methodological option—Theoretical Educational Inquiry—has been used by various authors who have developed influential proposals for understanding learning on the basis of a consolidated theoretical framework (philosophical, psychological or anthropological). J. S. Bruner (1960), for instance, developed his proposal for discovery learning on the basis of an epistemological reflection on the construction of knowledge rather than on direct empirical inference. Freire (1996) structured his pedagogy of the oppressed on the grounds of an ontological, anthropological and political framework rather than on experimental results. Vygotsky (1978) based his sociohistorical theory of learning on a theoretical reworking of psychological development which is based on philosophical concepts such as mediation and the sign.

More recently, authors such as Biesta (2006, 2020) have insisted that any relevant educational proposal requires a philosophical clarification of the meaning of learning, without which any methodological innovation loses its foundation. Biesta argues that learning can only be understood from a prior conception of the subject, the relationship and the world, which requires the development of conceptual frameworks that are theoretically sound rather than operational. This perspective is also shared by Wenger (1998), whose model of communities of practice arises from a profound sociocultural reflection on identity and learning as participation.

This methodological approach is particularly relevant when the object of study, human learning, is not conceived as a mere cognitive function, but as an integral and relational process, inseparable from the ontological constitution of the subject.

In order to describe the Theoretical Educational Inquiry and structure the presentation of this new understanding of learning, a sequential procedure consisting of five argumentative steps is adopted, following the recommendations of previous works on theoretical construction in education (Jaccard & Jacoby, 2020; Suri, 2011):

- Delimitation of the theoretical problem: we explain why current learning models are insufficient to describe what happens in human learning.

- Theoretical basis of the new model: selected psychological and philosophical contributions are reconstructed and integrated.

- Systematic presentation of the model: the new model is presented in a structured manner, explaining its founding principles, internal phases, relational dynamics, and explanatory value.

- Discussion and comparison with other approaches: a rigorous dialogue is established with historical and current theories to show the points of convergence, divergence and how these can be overcome.

- Epistemological and educational implications: the consequences of the model for the understanding of knowledge, the role of the educator, the link between learning and development, and the criteria for pedagogical evaluation are discussed.

This sequence responds to a criterion of progressive rationality (Lakatos, 1978) that not only allows the model to be developed, but also to be justified, contrasted, and positioned within the contemporary debate on learning. This sequence is found in numerous theoretical publications on education and psychology that seek to present new frameworks for understanding, beyond immediate empirical validation (Biesta, 2021; Matusov et al., 2019; Schön, 1992).

In Section 3, an initial comparison with other learning models is made in order to precisely delimit the uniqueness of the contribution. A critical argumentative review has been carried out, in accordance with the typology proposed by Grant and Booth (2009). This type of review does not aim to exhaust the available bibliographic universe on learning, but rather to establish a critical dialogue with the most influential and representative formulations in the field, taking into account both their academic relevance and their explanatory capacity. The selection of models is based on two criteria: (1) the inclusion of those models that have structured educational practice and theory in recent decades; and (2) the identification of those models whose assumptions or theoretical consequences allow for a fruitful contrast with the conception of learning proposed here, based on the relational development of children from 0 to 5 years of age.

2.1. Justification of the Intentional Selection of Authors for the Construction of the Model

Given that contemporary learning theories focus predominantly on the individual subject as the starting point of the learning process, the selection of the authors intentionally responds to the need to formulate a learning model that transcends these individualistic assumptions of traditional cognitive and behavioural frameworks which, in spite of recognising that interpersonal relationships can either facilitate or hinder learning, are based on the assumption of an already constituted self which subsequently enters into relationships. As such, the following authors have been selected: Stern, Trevarthen, Hobson, Winnicott and Kohut, in the psychological field and Polo, Buber, Levinas, Marcel, Spaemann, and Whitehead, in the philosophical one.

Following Suri (2011), the purpose of the article per se is not enough to justify the selection of authors. In the case of the present learning model, the theoretical corpus has been intentionally selected, seeking the conceptual coherence and explanatory potential of the sources, rather than exhaustiveness or balance between conflicting perspectives.

2.2. Interpretative Process

Suri’s (2011) proposal also recommends explaining the interpretative process that has been followed. In this paper, this process is based on the progressive integration of empirical findings and conceptual reflections. The first steps of our research focused on identifying the limitations of dominant learning theories, especially their omission of the relational foundation of human development. These findings led to an exploration of early developmental psychology, in which authors such as Trevarthen, Hobson, and Winnicott, among others, provide evidence of the fundamental role of intersubjective exchanges in the emergence of affectivity and cognition.

At that point, the LBCR model began to take shape around the idea that learning is not a process initiated by a previously constituted subject, but rather a dynamic unfolding that takes place within interpersonal relationships. In order to place this intuition within a broader anthropological framework, philosophical voices which consider the constitutive nature of the relationship were then incorporated: Buber, Levinas, Polo, and Spaemann, among others.

The model was designed through a dialogical exercise between these sources, paying special attention to those authors who not only describe the role of the relationship, but also position this as ontologically prior to the self. The result is not a synthesis, but a model which stems from the resonance between diverse disciplines and traditions in order to explain learning as a personalising and relational phenomenon.

3. Delimitation of the Theoretical Problem

In this section, we seek to highlight the limitations of existing learning models. Later, in Section 6, we will see how the new model aligns with and/or differs from each of them.

Firstly, in order to clearly identify what a learning model is, the books of R. Keith Sawyer (The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences, 2nd ed., Sawyer, 2014) and Knud Illeris (Contemporary Theories of Learning: Learning theorists … in their own words, Illeris, 2018) provide an overview of the contemporary landscape. These works seek to understand what the science of learning is, while also indicating the most significant theoretical contributions to explaining this phenomenon. Although it is not possible to find a uniform definition of learning which integrates the various perspectives analysed, it can be said that learning is a vital, permanent and multidimensional process through which individuals transform experience into meaningful understanding, modify their participation in social practices and build lasting capacities that integrate the cognitive, emotional and social dimensions (Illeris, 2018, pp. 7–11; Jarvis, 2018, p. 25; Kolb, 1984, p. 38; Dewey, 1980, p. 147; Sawyer, 2014, pp. 1–6, 128).

In all these works, it is found that learning far exceeds mere information retention or procedural efficiency. The literature reviewed insists that transformation is constitutive: transformation of what has been learned into comprehensive and transferable knowledge (deep learning involves the development of understanding that is connected and coherent, rather than knowledge that is fragmented and inert, Sawyer, 2014, p. 5); transformation of the learner, whose biography is modified by the integration of new meanings (Jarvis, 2018, p. 25); and transformation of society, insofar as learning involves participation in culturally organised practices (learning is … the transformation of participation in culturally organised activity, Greeno & Engeström, 2014, p. 128). The significance of what has been learned, the possibility of transfer to new contexts (Duschl et al., 2007), the new organisation of complexity through connected and coherent understandings (Sawyer, 2014, p. 5), as well as personal and social growth as a result of transformed experience (Dewey, 1980, p. 147; Kolb, 1984, p. 38), are an essential part of what learning means today.

In this paper, a learning model is understood as a theoretical construct that offers a systematic and integrated response to the various requirements for learning described above. As such, a learning model can be distinguished from: methodological proposals, which refer to practical guidelines for teaching in specific contexts; instructional pedagogies, focused on the design and sequencing of content to maximise efficiency in transmission; teaching strategies, understood as specific resources applied in the classroom; and curricular models, which structure the set of educational experiences of an institution. In addition, the research on learning models differs from focal research, which addresses partial or limited aspects of the phenomenon, such as working memory, motivation, or collaborative learning.

In order to analyse the limitations of the learning models in question, these have been grouped in ‘families’ in Table 1.

Table 1.

The learning models considered, grouped in families.

3.1. Models Based on Competences: Technification Without Ontological Depth

Since the 1990s, the competency-based learning framework has dominated the educational reforms, especially after its adoption by organisations such as the OECD and the European Union. This model, which defines learning as the acquisition, integration and mobilisation of knowledge, skills and attitudes to solve problems in specific contexts, has proven effective for employability and functional performance (Mulder, 2014). Most of the families considered in Table 1 (Behaviourism and Associationism, Classical and Constructive Cognitivism, Sociocultural and Dialogic, Experiential and Transformative, Self-regulation and Motivation, and Collaborative-Instrumental) have a marked competency focus.

This paper stems from a documented theoretical dissatisfaction with explaining the educational phenomenon through a competency framework (Biesta, 2010; Illeris, 2018; Dall’Alba, 2009). Despite their usefulness in standardised curricular contexts, these approaches show a structural limitation in accounting for the experiential, transformative and relational nature of human learning (Bendixen & Rule, 2004; De Bruyckere et al., 2015; R. Alexander, 2020). As various authors have pointed out, focusing the explanation of learning solely on adaptive efficiency, skill acquisition or information management omits constitutive dimensions of the person such as connection, affective significance, openness to otherness and the structuring of meaning (Biesta, 2021; Vandenbroeck et al., 2010).

Various authors warn that the technification of education underlying the competency approach reduces the complexity of learning to functional indicators and its instrumental usefulness (Biesta, 2009; Wheelahan, 2007; Lawn, 2011). Learning is treated as an operator of competences, without addressing issues of meaning, identity or comprehensive personal development.

Furthermore, as Deakin Crick (2007) points out, competency frameworks often omit key dimensions such as the affectivity, will or identity of the learner, reducing learning to quantifiable and observable aspects. This reduction hinders the understanding of deeply transformative processes, such as those that affect the way in which the subject positions themselves in the world.

Focusing on competencies makes it difficult to capture experiences in which the subject is transformed in their way of being in the world, as occurs in processes of ethical conversion, life crises, or existential discoveries. The reduced anthropological vision implicit in the competency model limits its ability to explain human learning in all its complexity.

3.2. Cognitivist Models: Fragmentation of Functions and Neglect of the Person

Models inspired by psychology, especially in their versions of information processing (IPT), Piagetian constructivism, or schema theories, have contributed significantly to the understanding of issues such as attention, working memory, cognitive load, or metacognition (Sweller, 2011; Mayer, 2011). However, their explanatory success is limited to structured tasks with defined objectives, while they are much less effective in describing how meaning is configured, how the desire to learn emerges, or how the emotional and relational dimensions of the subject are involved in learning. Despite its widespread acceptance in instructional design, cognitive load theory (CLT) has significant conceptual and empirical limitations that compromise its explanatory scope. As Schnotz and Kürschner (2007) have pointed out, the central assumption that learning improves through the systematic reduction of extrinsic cognitive load does not always hold true in real learning contexts. Far from a linear relationship between load and performance, the authors argue that certain forms of load, especially those associated with cognitive conflict or deep processing, can be useful and even necessary to promote meaningful learning.

Furthermore, CLT tends to operate under an additive model of load, without sufficiently considering the dynamic interaction between intrinsic load (related to the complexity of the content), extrinsic load (derived from the mode of presentation), and germane load (associated with the learner’s effort to construct mental schemas). This simplification hinders the applicability of CLT to complex situations which involve not only cognitive variables, but also affective, motivational, and contextual ones. Focused on efficiency, they do not give sufficient importance to the desirability of cognitive load in the learning process (Schnotz & Kürschner, 2007; Schmidt et al., 2007; Pyke et al., 2024). Consequently, reducing learning to the efficient management of available mental resources can obscure broader transformative processes linked to the subject’s meaning, identity, and agency.

Several authors have pointed out that the cognitivist model tends to conceive of the mind as an autonomous functional system, separate from the body, the environment, and relationships with others (Sfard, 1998; Illeris, 2003). This Cartesian view fragments the subject and fails to address the vital experience of learning with its affective load, its narrative character, and its inscription in history. As Immordino-Yang and Damasio (2007) have pointed out, even neuroscience questions this division, emphasising that all cognitive activity is modulated by emotional and social contexts.

3.3. Criticism of the Social Constructivism and Practice Communities

Vygotsky’s social constructivism, as well as Lave and Wenger’s proposal of situated learning and communities of practice, constitute a decisive advance by placing the origin of higher processes in social mediation (Vygotsky, 1978) and understanding learning as participation in shared cultural practices which shape the identity of the individual as an expert member of the group (Lave & Wenger, 1991). However, it is paradoxical that, having shown that learning and development are impossible outside of interpersonal interaction, both Vygotsky and Lave and Wenger stop just short of recognising personal relationships themselves as the final goal of learning. In Vygotsky (1978), the social is reduced to a matrix and mediation of cognitive functions; in Lave and Wenger (1991), to a mechanism of insertion into a community practice. In both cases, the relationship is instrumentalised: it is a springboard to another goal, but never an end in itself. The price of this reduction is high: it fails to recognise that what really sustains human growth is not knowledge or practice alone, but the living relationship and dialogue that make them possible.

Identity appears to be derived from participation in a collective practice, without recognising that knowledge of oneself and others are not epiphenomena of the group, but rather ontologically fundamental dimensions of learning. In other words, the community is legitimised in these models by its functionality in the transmission of knowledge, but not by its intrinsic value as a space for the constitution of the self.

Various analyses have pointed out this instrumental bias. Wegerif (2008) shows that the Vygotskian perspective is dialectical rather than dialogical, so that interpersonal relationships are understood as a means for the internalisation of cognitive functions. In line with communities of practice, Contu and Willmott (2003), J. Roberts (2006) and Amin and Roberts (2008) denounce the instrumentalist drift that subordinates community to functional or organisational ends. In contrast, Biesta (2009) and Radford and Roth (2011) argue that education must recognise the dialogical relationship and ethical commitment as the final goal of learning.

3.4. Limits of Anthropology of Education

The classical approaches of Mead, Greenfield, Rogoff and LeVine extend Vygotsky’s notion of the “zone of proximal development” in which children advance their understanding by participating in culturally structure activity with the guidance, support and challenge of companions who vary in skill and status. The perspective of guided participation adopts the assumption that humans are biologically social creatures with a self-regulating strategy for getting knowledge by human negotiation and cooperative action (Rogoff et al., 1993).

Although this perspective articulates individual, interpersonal and cultural processes as inseparable aspects of whole events in which children and communities simultaneously develop (Rogoff, 1995), it seems to focus on the aspects of children’s development more oriented towards the models of human activity provided by previous generations. While recognising the child’s creativity in these cultural activities, there is a risk that the child’s singularity may not be sufficiently recognised. Moreover, while guided participation regards interpersonal relationships as a necessary condition for learning, it does not seems to elevate them to the status of the telos of learning. What validates a culture is not its mere existence, but its capacity to facilitate interpersonal encounters. This subordination to encounter constitutes the reference point for cultural change: to welcome a culture is to welcome previous generations and, for that very reason, culture must remain subordinate to previous and future encounters.

3.5. Limits of Enactivism

Enactivism and the notion of participatory sense-making understand that knowledge arises from the dynamic coupling between organism and environment. Their emphasis on corporeality, situated action, and intersubjective co-regulation breaks with classical representationalism. However, the perspective is marked by a biologicist background: although it recognises specifically human dimensions such as language, symbolism and culture, these are interpreted above all as new normative domains that emerge within the horizon of autopoiesis, whose ultimate criterion is the viability of the organism. Consequently, interpersonal relationships are not understood as the goal of learning, or even as an intrinsic value, but as a functional condition for the stability of the system.

This consideration has several implications: the other is conceptualised as a co-agent in the interactive dynamic, but not as a personal otherness who is valuable in him or herself; the continuity between the biological and the socio-cultural is affirmed, but without categories that allow for the personal constitution of the self as a being-in-relation; by attributing autonomy to the interactive process, the theory of participatory sense-making describes interaction and culture as if they were agents in themselves, i.e., the relational is understood as a ‘third agent’. Since the term “agent” is applied to both biological organisms and social or cultural dynamics, the specificity of personal agency is diluted.

Villalobos and Palacios (2019) warn that enactivism, by identifying the cognitive with autopoiesis, incurs a biologistic bias that makes it difficult to explain personal phenomena. Schlicht (2018) and M. Roberts (2018) point out that this model fails to explain how higher capacities such as language and conceptual thinking arise. Herschbach (2012) highlight the ambiguity of attributing autonomy to social interaction, which ends up being a ‘third agent’.

3.6. Limits of the Care Proposal and Theories of Agency

Although Noddings (1984) breaks with the instrumental view of relationships by placing care as a constitutive end of the person, and Edwards (2005) redefines agency as co-agency generated by recognising and mobilising the resources of others, both proposals share a decisive limitation: the lack of integration between the relational and the cognitive. In Noddings (1984), care includes activities such as modelling, dialogue, practice and confirmation, but knowledge of the other and the world remain in the background, without clearly revealing how and why cognitive exercise contributes to the care of the relationship, which makes it difficult to arrive at a consistent theory of learning (Hickey & Riddle, 2024). In Edwards (2005), relational agency goes beyond a mere strategy, but remains on a sociocultural-functional level due to it not being linked to an ontology of the person or to a comprehensive conception of learning as personal transformation. Thus, although both perspectives share the centrality of the bond with the LBCR model, they lack constructs to show how it shapes self-understanding, meaning, and openness to the world.

3.7. Inability to Describe Learning as Profound Personal Transformation

The competency paradigm shares with cognitivism, social constructivism, and enactivism an implicit anthropology focused on operability and adaptive efficacy, which is insufficient to explain learning as is understood by approaches such as narrative pedagogies, relational models, and experiential education. The latter approaches reconceptualise learning as a transformative event which involves the constitution of meaning, the emergence of the self, and openness to otherness (Mezirow, 1991; Kegan, 1982; Biesta, 2013).

The prevailing paradigms in the literature are limited in their ability to address this conceptualisation of learning on several fronts. The relationship is instrumentalised: meta-analyses confirm that teaching presence is associated with satisfaction and performance by disregarding its ontological status (Caskurlu et al., 2020). Other studies show that care can operate as a transformative experience that constitutes professional identity (Clouder, 2005). There is also a teleological void: neither activity theory nor connected learning formulate personalised goals, which has led to talk of “education without a subject” (Biesta, 2007, 2010). In the didactics of science, too, critical vigilance is called for in order to detect the implicit teleologies of thought (González-Galli, 2020).

A theory of the self-in-relation is clearly needed: learning is not just about organising information or socialising in a practice, but about personal becoming in society (Jarvis, 2018). This is confirmed by developmental psychology, which shows that identity and social understanding emerge in early interaction (Carpendale & Lewis, 2004; Meltzoff, 2007).

Trust and care are often treated as mere factors of the motivational climate, when in fact they are epistemic-ontological conditions of openness to knowledge and to others, as Davids (2024) has shown. Emotion and corporeality are reduced to modulating factors, even though neuroscience has shown that they are constitutive of cognition and learning (Immordino-Yang & Damasio, 2007; Pekrun, 2006; Pessoa, 2008).

In spite of their valuable and promising appearance, all these approaches still face the challenge of articulating an integrative and philosophically consistent theory that explains how deep learning is configured from the early stages of human development. As van Manen (1997) has pointed out, educating is not only about transmitting content, but also about exercising a form of care and presence that shapes a certain way of being in the world. This conception requires a thorough review of the prevailing theoretical frameworks (A more detailed analysis of the various learning models mentioned can be found in the Supplementary Materials).

4. Theoretical Basis of the New Model

The learning model based on constitutive relationality is supported by a critical and rigorous integration of the psychological corpus of early development and a relational philosophical anthropology, and is aimed at explaining learning as a process of personal and relational constitution from the earliest bonds.

4.1. Contributions from Early Developmental Psychology

In Stern’s words, relationship is not a ‘complement’ to psychic development, but rather its essential constituent (Stern, 1998, pp. 10, 137, 144). Therefore, any educational proposal that seeks to be faithful to the reality of the human subject must start from the bond as the origin and foundation of learning. This statement is not an ideological gesture or an abstract formulation: it is empirically based on clinical and experimental observation of child development. This is precisely what Stern contributes in The Interpersonal World of the Infant: a detailed demonstration that the very structure of the self emerges in the relationship with the other.

From the first weeks of life, babies do not live in a purely sensory or egocentric world, but in an interpersonal world. This is not a matter of progressive external socialisation, but of an original interpersonal nature. The human environment is not regarded as decorative, but as a structural component of the lived world (p. 10). The relational experience is not episodic or accidental, but continuous and constitutive: the infant interprets and organises its experience through active participation in shared meaning-making frameworks.

Stern identifies different domains of the self—emergent, nuclear, subjective, and verbal—which do not occur linearly but coexist as simultaneous modes of organising experience (p. 14). This statement allows the LBCR model to view learning not as a uniform process but as a progressive integration of levels of the self that are in constant interaction with each other. In the first phase of the model, which activates the desire for relationship, the emergent self finds its reflection in the attentive presence of the educator; in the second, which integrates experiences, the subjective self comes into play; and in the third, of transformative expression, the verbal and reflective self is placed at the service of relational growth.

The desire for intersubjectivity is neither learned nor induced: it is original. Infants do not simply seek to satisfy physiological needs, but to establish shared states of attention and affection (p. 100). This confirms one of the fundamental premises of the LBCR model: the driving force behind learning is not content, but the desire for encounter. This structural drive towards relationship precedes any instrumental or adaptive logic. One learns because one desires to be recognised by an other with whom one shares the world, not because one aspires to abstract knowledge.

Affective interaction is at the very core of psychological development. Stern emphasises that moments of authentic “encounter”, where adults and infants achieve emotional synchrony, do not transmit information but rather generate subjective structures (p. 142). In these moments, infants experience that their inner world has meaning because it is welcomed and shared. The LBCR model takes up this key point: there is no real transmission if there is no affective resonance, if the learner does not experience that their inner world is being heard, understood and expanded by the educational relationship.

Knowledge, therefore, does not arise from isolation or logical inference, but from intersubjective experience. Children do not construct meaning from the object, but from the perception that their experience is understood by an other (p. 144). This observation is decisive in establishing the relational epistemology of the model. The classroom is not a space for the transmission of objective truths, but for the shared construction of meaning. Meaning is not a property of the content, but of the link that sustains it.

Stern also shows that children are capable of abstracting patterns of interaction and anticipating responses based on the implicit relational history they are constructing (p. 152). This implicit learning of relational rules validates the need for the educational environment to go beyond simply organising content and instead take exquisite care in the types of relationships it enables. Every educational act communicates not only the explicit content, but also the way in which it is offered, the attitude of the educator, the configuration of the space between educator and learner, and the possibility of response. It is at this implicit level that the truth of the bond is played out, and with it, the power of learning.

This knowledge, which is structurally relational, is not predominantly verbal. Affective, procedural, bodily, non-narrative memory is deeper and more lasting than explicit memory (p. 150). This underpins the insistence of the LBCR model that assessment cannot be reduced to verbal or conceptual performance. What the learner retains and transforms is not what they can say, but what they have experienced with meaning. Therefore, assessment indicators must reflect processes of personal integration and relational growth, not just formal cognitive acquisitions.

Finally, Stern argues that knowledge of the other is not based on rational inferences, but on direct, lived experience of the other’s mind (p. 142). This deeply phenomenological insight reaffirms the thesis that meaningful learning emerges from mutual openness, not from unilateral explanation. When interpersonal relationships are authentic, they generate a space for the co-emergence of meaning where both subjects—educator and learner—are transformed. It is not a matter of one transferring knowledge and the other receiving it, but rather of both becoming involved in a relational process where knowledge arises as the fruit of an encounter.

In short, from the structuring of the self to the genesis of meaning, from the original desire for relationship to the affective configuration of memory, each dimension of learning is revealed as intrinsically relational. There is no subject without a bond, no knowledge without recognition, no learning without encounter.

The LBCR model is rigorously based on the work of Colwyn Trevarthen, who demonstrates that relationships are not an addition to psychological development, but rather its original condition. From birth, human beings are endowed with a disposition towards intersubjectivity that shapes their way of knowing, learning and constructing themselves as subjects (Trevarthen & Aitken, 2001, p. 3; Trevarthen, 2009, p. 476).

In contrast to models centred on an isolated subject, Trevarthen shows that the baby’s mind is oriented towards the other. This orientation is expressed in early capacities for motor coordination, shared attention, affective expression and emotional synchrony (Trevarthen, 1998, p. 22; Trevarthen, 2001, p. 95). Thus, knowledge is not generated from autonomous internal processing, but rather from the encounter between minds that affect each other (Trevarthen, 2009, p. 475; Trevarthen, 2011, p. 175).

This relational basis redefines the motivation to learn. The impulse is not to satisfy individual needs, but to share intentions and affections. This intersubjective motivation guides the baby’s actions from the outset (Trevarthen, 2001, p. 96; Trevarthen, 2011, p. 174), which strongly suggests that education should prolong this relational dynamism, rather than replacing it with rewards or controls.

Trevarthen also emphasises the active role of the baby in the relationship: they are not a passive recipient, but an expressive subject, capable of initiating and adjusting interactions (Trevarthen, 2001, p. 99; Trevarthen & Aitken, 2001, p. 6). The co-construction of the bond is the origin of development, not its effect.

The self is shaped by these intersubjective experiences: subjectivity is not formed in isolation, but in shared emotions that shape identity and intentionality (Trevarthen, 1998, pp. 23–24; Trevarthen, 2009, p. 478). There is no personal mind without a bond.

Trevarthen’s approach calls for an intersubjective pedagogy: learning requires contexts that reproduce the primary matrix of knowledge—affective resonance, shared rhythm, attunement of intentions—(Trevarthen, 2011, pp. 174–175). Unilateral teaching ignores the very basis of the desire to learn.

Communication also precedes language. Before speaking, children already have a complex system of gestures, vocalisations and movements with full communicative functions (Trevarthen, 1998, pp. 27–28; Trevarthen & Aitken, 2001, p. 4), which makes non-verbal expressiveness a fundamental way of accessing their inner world.

From this perspective, the educator does not “teach from the outside”, but responds from the bond, adjusting to the child’s emerging subjectivity (Trevarthen & Aitken, 2001, p. 9; Trevarthen, 2001, p. 102). Educating is about making something resonate, not imposing it.

Cultural transmission does not occur through formal instruction, but through affective participation in shared meanings. Children acquire language, values and symbols in emotionally meaningful contexts (Trevarthen, 2011, p. 175).

When the bond deteriorates—through abandonment, neglect, or insensitive teaching methods—the child’s mental health is affected. The breakdown of intersubjectivity is at the root of numerous emotional and social disorders (Trevarthen, 2001, p. 117; Trevarthen, 2009, p. 485).

Furthermore, the mind does not operate from an abstract logic, but from shared emotional rhythms. Temporal coordination—in voice, movement, attention, affection—supports cognitive functions such as memory and planning (Trevarthen, 2001, pp. 102–104; Trevarthen & Aitken, 2001, p. 13). To think is to enter into a rhythm with another.

Imitation, for its part, is not mechanical: it is an active form of communion with the other. The child imitates in order to participate in the world of the other, and this participation has cognitive and moral value (Trevarthen & Aitken, 2001, p. 7; Trevarthen, 2001, p. 105).

Peter Hobson’s thinking provides a solid foundation for the educational model focused on interpersonal relationships. From the earliest stages of development, knowledge of others is not acquired by inference, but rather experienced from within the affective relationship (Hobson, 2002, p. 70). Intersubjectivity is not secondary: it is constitutive of experience. Rather than observing, children become emotionally involved, and this involvement shapes their subjectivity and their access to the world (p. 72).

The self does not arise in isolation, but needs to be reflected and emotionally accompanied (p. 74). The face of the other not only reflects, but also structures the child’s consciousness. The world is not presented in its ‘crude’ form, but is emotionally shaped by those who share it with the child (pp. 76, 82). Language is not a formal system that is learned, but a relational practice that requires the expectation of shared meaning (p. 79). The child’s mind is shaped by the meaningful gestures of adults (p. 80).

Accordingly, a pedagogy faithful to the truth of the human being should be intersubjective, not directive. It is not a question of leading the child. Learning does not consist of receiving information, but rather of participating in a shared experience (p. 84). Objects acquire meaning when they are shared from the perspective of another (pp. 82, 85). It is the shared perspective that gives value to the object, not its mere existence. Guided attention is not something technical, but rather a form of emotional and intentional involvement. Symbolic thinking arises from sustained emotional relationships (p. 90). Imitation requires affective identification (pp. 92, 94). Children perform acts of symbolic representation because they are recognised, not because of isolated introspection (p. 100). This logic supports the thesis that interpersonal recognition is the basis of educational power.

Narratives emerge from shared emotional experiences (pp. 104, 106). Subjectivity does not develop outside of the bond (p. 110) and the mind is unified in emotional attunement with others (p. 114). Reflective consciousness arises from having been the object of emotional attention (p. 119). The thinking self is born of the you that recognises. This justifies an educational assessment focused on the ability to respond to the recognition received.

Language, imagination and thought do not emerge from the isolated brain, but from the original “us” (p. 224). Thought prolongs lived dialogue (p. 130); the desire to know arises from the desire to share (p. 220). To educate is not to transmit, but to welcome, to welcome the thoughts of others as a manifestation of the welcome offered to them (p. 260). To teach is to share an affective horizon (p. 162); to know is to open oneself to the other who transforms (p. 229). The teacher allows the other to discover themselves as a capable subject (p. 240). Intersubjectivity is not peripheral: it is the structure of knowledge, ethics and identity (pp. 140, 232). The human mind is relational from its origin (p. 213) and only unfolds in a meaningful community (p. 272). These ideas not only support but also underpin the proposed educational model: learning is always a transformative intersubjective experience.

One of Hobson’s most decisive contributions is to show that psychic life does not originate in individual emotional experience, but in the constitutive link with another subject who already possesses a mind (p. 4). The child is not born as an isolated being who later enters into relationships, but as a being destined to form its consciousness in the midst of encounter. The relationship is not accessory, but intrinsic and generative: the self emerges in the experience of being looked at, sustained and understood, not merely in an affective way, but in a deeply intersubjective way.

In contrast to this view, Bowlby’s (1982) attachment theory, although pioneering in its assessment of early bonding, suffers from a functionalist reduction of the other to an affective regulator. In Bowlby, the other appears as a source of comfort, as a refuge from distress, and not as a you by virtue of which the self can become (p. 100). The child seeks out their attachment figure because it makes them feel good, because it regulates their emotions, especially fear and anxiety (p. 95). This approach, although clinically useful, overlooks the fact that the child seeks to be recognised, not simply reassured (p. 105). Emotional security thus becomes, for Bowlby, an end in itself, displacing the true centre of development: the desire for relationship as such, for sharing experience and meaning with an other (p. 103).

Hobson (2002) insists that there is a primary motivation for the encounter, prior to the search for pleasure or relief. The child turns to the other not because of the positive emotions it generates, but because it offers the possibility of establishing a relationship. This orientation towards the other cannot be reduced to a biological need for comfort, but is charged with intersubjective meaning (p. 97). Proof of this is that the child responds enthusiastically to the attentive presence of the adult, even when there is no physical contact or immediate gratification (p. 34): the interaction is desired for its own sake.

The infant distinguishes between relational qualities. Not all smiles, caresses or looks have the same formative weight. They perceive when they are welcomed as a subject and not simply stimulated or calmed. They may reject emotionally intense interactions if they do not involve reciprocity or mutual understanding (p. 132). This sensitivity shows that the centre of their desire is not the pleasant affective experience, but recognition in the encounter.

Even without immediate gratification, the baby maintains interaction (p. 118). He or she seeks the presence of the other with whom to construct shared meaning. The most formative bond is not the most pleasant one, but the one that involves the greatest mutual participation. From the earliest months, the child experiences the relationship as a place of co-creation of meanings, where the self is configured in response to the other (p. 141).

This perspective allows us to overcome readings that reduce development to internal maturation and also those that see the relationship as a source of pleasant experiences. In the model proposed here, and with Hobson’s support, the child appears as an ontologically relational being, whose access to the world and to him or herself depends on the intersubjective quality of the bond. It is interaction with another person that activates and structures his or her capacities, not only emotional, but also cognitive and volitional.

Donald Winnicott contributes a theory that serves as the foundation for the learning model based on constitutive relationality. Far from understanding the self as a given entity, he presents it as the result of a process of progressive integration sustained by a trustworthy human environment. This emergence of the self is inscribed in a matrix of primary intersubjective relationships, in which the infant experiences being to the extent that he or she is received, sustained, and reflected. The initial maternal relationship, characterised by the ability to actively adapt to the child’s needs, is central to the child’s development of their psyche as a shared space and, subsequently, their personal autonomy (Winnicott, 1990, p. 28; Winnicott, 2005, p. 146).

From this perspective, learning cannot be conceived as merely acquiring content or as a functionally adaptive process. Rather, it involves a subjective transformation rooted in a meaningful relational experience. Winnicott insists that personal growth occurs when the subject feels real, i.e., when there is a continuous sense of being that is sustained in the relationship with a sufficiently receptive other (Winnicott, 2005, p. 158). The condition for learning is that the subject can experience their existence as valid in a space that recognises their uniqueness without invading it. Hence, the emergence of the self is inseparable from relational trust and, therefore, learning involves going through a series of destructurations and reorganisations sustained in the bond.

Winnicott introduces the concept of transitional space to designate the intermediate realm between subjective and objective reality in which play, creativity and symbolisation unfold (Winnicott, 2005, p. 2). This space is not spontaneous, but rather the result of a relational process in which the child is accompanied in the progressive disillusionment of their omnipotence. If the environment supports this process without prematurely shattering the illusion, the child will be able to construct objects as shared external realities (Winnicott, 2005, pp. 17, 122). It is precisely in this space co-created by interaction that the passage from being to knowing takes place: learning is possible only when the subject has experienced that the world is not an extension of themselves, but a reality that can be shared and creatively transformed.

This approach converges with the LBCR model, in that learning is understood as an act of personal emergence in relation to others. Creativity, which Winnicott links directly to mental health, is the sign of an integrated subjectivity that has gone through the process of separation-individuation without severing the relationship with the other (Winnicott, 1990, p. 39; Winnicott, 2005, p. 87). The ability to co-create, both in play and in life, is the original mode of personal authorship. Learning involves symbolically appropriating experience and projecting it into meaningful actions. This authorship is only possible when one has gone through the game of presences and absences, and when the subject has been able to use objects without identifying with them, recognising their otherness (Winnicott, 2005, pp. 120–125).

Thus, the educational function cannot be limited to the transmission of information, but must create transitional spaces where the subject can symbolise, play and transform. The role of the educator is similar to that of the therapist, not as a content manager, but as an available presence that facilitates creative use of the relationship (Winnicott, 1990, pp. 96–97). Learning occurs when the learner can use the educator—the image they have formed of the educator—as an object in the process of constructing meaning, not when they passively internalise it. Therefore, the learning environment should resemble the family in its structuring function as a space of unconditional acceptance (Winnicott, 1990, p. 119).

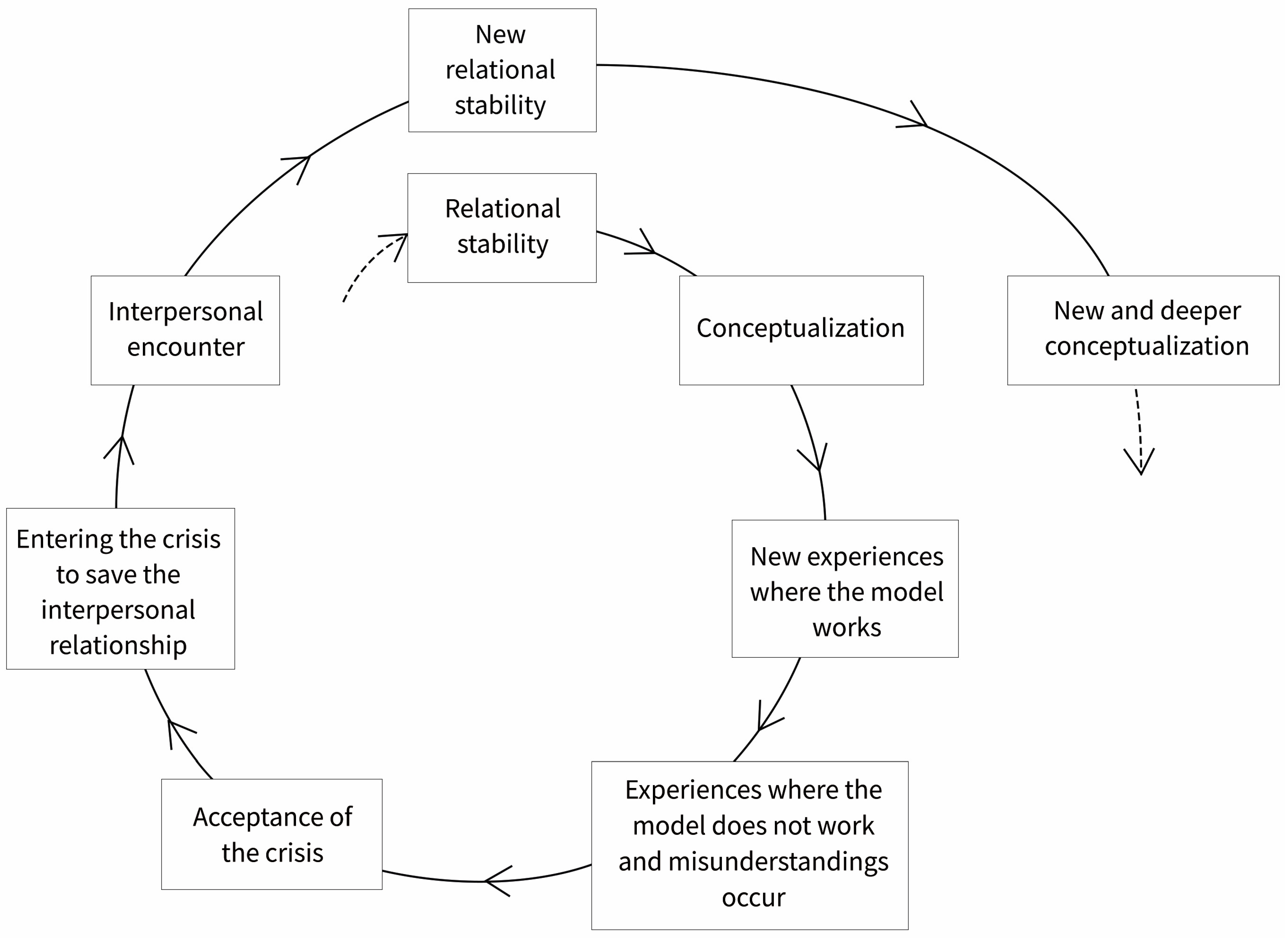

The LBCR model we propose is thus reinforced by the notion that learning is a way of reorganising experience in terms of a relationship. Emotional integration, the emergence of the self, the constitution of the object, and creativity are not isolated phases, but moments in the same relational movement that makes meaningful knowledge acquisition possible. In this sense, the proposed learning cycle (Section 5.2), described as a spiral of crisis and reconciliation, is directly rooted in Winnicott’s logic of disintegration and sustained reorganisation. Only in a sufficiently positive environment can one fail without collapsing, become disorganised without fragmenting, and reintegrate in a broader way. Learning is thus a way of growing: a way of becoming oneself in relation to others and to the world.

Kohut’s ideas are highly relevant in revealing that the child is not merely a ‘bag of impulses’, but rather an individual oriented towards encounter. From that encounter, the child comes to know him or herself as an I. All learning is embedded in this horizon of meaning. In contrast to drive theory, which conceives of the psychic apparatus as the result of conflicting forces, Kohut (2009, p. XV) points to the organisation of the self as the core of the psychological universe. This theoretical reorganisation makes it possible to move beyond models focused on the regulation of tensions to understand human development as the emergence of a psychic structure capable of generating meanings, integrating experiences and establishing creative goals (p. 17).

In this context, learning cannot be reduced to the functional acquisition of skills. Rather, it involves the restoration and consolidation of a self that, when structured in relation to empathic self-objects, transforms suffering into meaningful symbolic configurations (pp. 22, 54). Meaningful learning is not simply the resolution of internal conflicts, but the possibility of offering a stable and creative expression of the self after having gone through, with support, a regression to archaic levels of psychic disintegration (pp. 19–20, 64).

This perspective coincides with the understanding of learning as a cycle of destructuring and reintegration. For Kohut, psychopathology is not explained by the intensity of impulses but by failures in the configuration of the self due to a lack of empathic encounter with self-objects (pp. 116, 122). What is innate is not aggression, but trust (p. 119). Anger is not seen as an expression of a primal force, but as the result of the disintegration of that empathic configuration (pp. 91, 114). Therefore, educational support cannot be limited to correcting behaviour. Instead, it must offer an environment of affective resonance capable of sustaining the continuity of the self in formation (pp. 179–180).

The self is not constituted in opposition to the other, but rather through recognition of oneself in the other. From the first encounters with the mother, a process of constitution of the nuclear self begins which depends on the responsive capacity of the maternal self-object (p. 100). This primitive constitution, which precedes even the maturity of the nervous system, is mediated by relationally experienced tensions, not by isolated internal forces (p. 101). Therefore, real learning requires similar conditions: a sustained empathic relationship that allows tensions to be metabolised without leading to fragmentation of the self.

Kohut rejects the idea that the completion of a therapeutic process should be measured by external functionality. True restoration of the self occurs when the subject can joyfully experience their life as meaningful and creative (pp. 63, 139, 174). Similarly, a learning process can only be considered successful when it has strengthened the subject’s ability to act meaningfully from their own internal configuration, and not when he or she has adopted compensatory mechanisms to respond to external demands (pp. 3, 134).

There are no forces to regulate. Therefore, neither overprotection nor deprivation respond to the subjective reality of the subject; both are based on a mechanistic view that ignores the unity of the developing self (pp. 78–81). In contrast, empathic accompaniment allows the child to integrate their experiences, even traumatic ones, into a meaningful personal narrative. The self-object is thus an incorporated relational instance that actively contributes to the child’s psychological organisation (pp. 85–87).

Learning, in this sense, is not about resolving a conflict, but about restoring a wholeness. The intervention is not oriented towards tensions, but towards the suffering of the self (p. 130). The goal is not to repress impulses, but to generate internal structures that creatively express identity in relation to others. The theory of the self replaces the metaphor of force with that of empathic resonance, shifting the focus from the instinctual to the relational (pp. 69–75, 228).

On this basis, the LBCR model is consolidated as a practice of self-restoration. Only when the learner is accepted in their entirety can an experience of personal continuity occur, allowing them to integrate their experiences and orient themselves towards meaningful goals. In this process, parents, educators, or therapists, by creatively displaying ideals and ambitions, offer the learner internalisable models of integration (pp. 234–235). Learning is, therefore, becoming a self capable of articulating one’s life around a sense of self, sustained and confirmed in relationships with others.

Taken together, these approaches converge on the idea that human learning is structured from a primary affective and relational basis, prior to language, where the self, symbolisation and the possibility of meaning are constituted. Learning is, first and foremost, participating in a relational field endowed with vitality, affection and the co-construction of meaning.

Other authors’ research has followed similar lines. However, authors such as Piaget, Freud, Izard, Bennett, Wolff, Spitz, Werner, Mahler, Pine, and Bergman view children from a different and distant perspective: as self-centred beings who need stimulation and guidance, driven by the central desire for self-satisfaction (Orón Semper, 2024, pp. 174, 263).

4.2. Contributions from the Relational Philosophical Thought

While early developmental psychology provides empirical evidence on the relational constitution of the self, relational philosophy enables the explanation of the ontological and ethical assumptions underlying this understanding. This section presents the main philosophical contributions which allow us to understand learning as an originally intersubjective act.

Leonardo Polo distinguishes between essence and act of being to indicate that the essence of the person (rational, affective, bodily nature) does not exhaust their being, which consists of an act of coexistence with others. This idea, developed systematically in Antropología Trascendental I: La persona humana (Polo, 2003), implies that the person is a being in relation, a co-being, not by extrinsic addition, but by their radical mode of being. From this perspective, learning cannot be regarded as an internal operation or an individual adaptive strategy: learning is a form of the unfolding of personal being in its openness to others, an exercise in coexistence. Thus, interpersonal relationship is not a simple means to knowledge, but its ontological condition.

In the same work, Polo argues that a person is also personal knowledge. Knowing is not limited to handling objects or representations. The fullest knowledge is knowledge of the other as a person, and this is neither inferential nor abstract, but intuitive, convivial and direct. Such knowledge requires mutual recognition between people: mutual openness in an unrestricted, endless process. This conception aligns precisely with the structure of the proposed model: learning only becomes meaningful when it is anchored in an interpersonal relationship of empathic recognition. The figure of the educator, therefore, is not defined solely by what they know or transmit, but by their ability to confirm the other as a person and to sustain the space where they can grow.

The growth of the person is not a simple accumulation of abilities, but an expansion of their coexistence, that is, a greater openness to reality in its multiple dimensions: other human beings, the world, God. This idea, formulated in El acceso al ser (Polo, 1999), implies that all growth involves an increase in the capacity to welcome others. In the field of education, this idea transforms the very meaning of learning: one does not learn in order to possess more, but in order to live together better, to expand one’s personal willingness to enter into relationship with realities that previously remained closed. In this way, learning becomes a form in which the self broadens, beyond a mental operation.

This broadening, however, requires a specific condition that Polo formulates in his theory of abandoning mental limits, developed in La esencia del hombre (Polo, 2011). For this author, human knowledge progresses when the subject recognises the limits of their thinking and abandons them, not by discarding them, but by overcoming them through expansion. This abandonment cannot be done by mere will or technical calculation: it requires trust, both in reality and in the other who represents it: the educator. In this sense, the cognitive crisis is not a failure, but a structural opportunity for the subject’s growth, provided that they can trust the relationship that sustains them. Here, the connection with the relational learning model presented is direct and fundamental: the overcoming of previous clarities (operational mental structures) can only occur when the subject experiences a trustworthy relationship that allows them to surrender to the process of cognitive detachment and existential openness. Interpersonal trust is therefore not an added affective condition, but a requirement for the expansion of knowledge.

Emmanuel Levinas offers a radical ethical-ontological basis which reinforces the underlying structure of the learning model we propose. He criticises the self-centred subjectivity and reconfigures the very idea of the subject as configurated from the relationship with the other. In this sense, his thinking converges directly with a relational pedagogy that places learning in a sphere of ethical and ontological openness to otherness, without reducing it to the cognitive activity of the individual.

The category of “the face of the other”, as explained in Totalidad e infinito (Levinas, 2002), is not an image, nor a perception, nor an object for thought; on the contrary, it is a presence that deconstructs or breaks down any attempt at appropriation while challenging the self from an irreducible height. This irruption brings into play the very possibility of the subject as such: one is not a subject by oneself, but because one has been interpellated by the other, which requires an openness of trust to accept the rupture of one’s own consciousness. Within the framework of the LBCR model, this thesis translates into a key affirmation: learning does not begin when the subject decides to know, but when an other calls them to come out of themselves, to open themselves, to respond.

Another idea of Levinas, first formulated in Totalidad e infinito (Levinas, 2002) and, in greater depth, in De otro modo que ser o más allá de la esencia (Levinas, 2000), is that subjectivity does not precede the relationship, but is constituted in and by it. Contrary to learning theories which assume the idea of a preformed self that later forms relationships, Levinas argues that the self is the effect of otherness, not its starting point. This connects directly with the assertion that deep learning is not the activity of an autonomous subject, but a process of personal constitution in relationship.

Another key assertion by Levinas is that responsibility for the other precedes freedom. As he explains in Levinas (2000), responsibility is not a choice, nor a rational decision, nor a reaction: it precedes all spontaneity of the self, and therefore constitutes its deepest structure. The subject does not choose to respond. He or she is already responsible even before knowing so. This idea is decisive for the LBCR model, which insists that openness to learning cannot be thought of as a voluntary or strategic disposition, but rather as an original dynamism that is activated in the recognition of the other as a significant presence. Learning is, in this sense, a way of “exercising ontological responsibility towards the other that constitutes me”.

In Ética e infinito (Levinas, 2008), the author asserts that language is not, in its origin, an instrument of transmission, but rather an act of hospitality. To speak is to welcome the other in their otherness without reducing them; it is to open a space where the other can dwell without being assimilated. In the field of education, this conception radically transforms the function of words: teaching is not explaining, but hosting the other’s thoughts; sustaining a space where they can express themselves, resist, and signify. The educational relationship is thus a space of linguistic hospitality, where meaning is constructed not by imposition, but by welcome. This fits into the LBCR model, where the intersubjective bond is a condition of possibility for the emergence of new clarities, and where the figure of the educator is defined more by their receptive presence than by their transmissive role.

The encounter with the other does not add something to subjectivity, but is rather that which produces it. The self does not precede the other: the self becomes self to the extent that it welcomes the other, opens itself and, in this openness, transforms itself. This transformation is what the learning model based on constitutive relationality describes as the spiral of crisis and reconciliation, where the deconstruction of previous certainties is not a loss, but an opportunity for a deeper, more human, more open understanding. Levinas provides an essential key here: learning is not accumulation, but decentring; it is not functional stability, but existential openness to the other who “decentres me and, in doing so, constitutes me”.

Martin Buber bases his anthropological proposal on the vision of the human being as a being-in-relation. Buber (2006) does not limit himself to pointing out the ethical or social importance of encounter: he affirms that relationship is the original structure of the self. From this premise, his work offers essential conceptual elements for understanding that meaningful learning does not occur in isolation, but in the living reciprocity of an authentic interpersonal bond.

The cornerstone of his relational philosophy is the distinction between I-You and I-It relationships, as developed in Yo y tú (Buber, 2006). The I-You relationship is not established between a subject and an object, nor is it defined by utility, analysis or manipulation; on the contrary, it is a relationship of mutual presence, in which both terms are constituted simultaneously. According to Buber, the I only fully exists insofar as it addresses a You: “the I becomes I in the You”. This idea aligns directly with the central thesis of the learning model based on constitutive relationality: the relationship is not a means of learning, but its ontological condition. Only when the other is welcomed as You, rather than being reduced to an object, can a truly formative process of transformation begin. The fundamental relationship is between the learner and the educator (I-You) and not between the learner and the curriculum (I-It).

This fundamental principle has direct consequences for the conception of the educator and the act of education. In his pedagogical essays, collected in El problema del hombre (Buber, 1998) and Entre el hombre y el hombre (Buber, 2001), the author argues that education does not consist of transmitting knowledge or adapting the learner to a functional environment. Authentic education is, above all, an event of presence: the teacher does not teach from a distance, but is present as a person, and it is this presence that enables the learner to emerge as a subject. This conception is fully in line with the LBCR model, which does not conceive of the educator as a technical facilitator, but as the guarantor of the relational space where the person can be shaped and transformed.

In this sense, the educational word does not occur in instruction (I-It). In Yo y tú (Buber, 2006), the author insists that every true word arises from encounter, not from monologue or transmission of technique (It). The word that transforms is not the one that informs, but the one that welcomes the other into its being, generating a common space of meaning. This understanding of educational language as a relational act reinforces the hospitable dimension of the LMCR model: there is no learning without openness, and there is no openness without words that invite, welcome and listen.

Furthermore, Buber formulates a decisive thesis for understanding the constitutive dimension of the relationship: only the Thou allows the I to access him or herself. There is no I without You; there is no identity without encounter. This approach, developed both in Yo y tú (Buber, 2006) and in his later writings, converges with the findings of early developmental psychology that underlie the proposed model, giving these findings additional anthropological depth. To learn is to respond to another who calls me to be. Learning (the It) is structurally intersubjective (I-Thou). The I-Thou interaction is reflected in the relationship with the It.