Abstract

This article studies practical argumentation in the context of designing application problems and transforming them into modelling problems. To this end, the practical arguments developed by prospective primary education teachers were analysed, using a scheme for structuring and representing these arguments and a modelling cycle for representing the solution plans proposed to these problems. This is a case study with three groups of prospective teachers who were taking a course on mathematical reasoning and activity in primary education, where problem solving and mathematical modelling were the two most relevant topics. For data collection, a questionnaire was applied to and an interview was conducted with the study subjects, thus identifying nine episodes of practical argumentation based on the justification of their pedagogical decisions made on the design and transformation of problems. Also, the written reports prepared by the study subjects were reviewed to analyse their solution plans proposed to the problems. The results showed that the study subjects developed practical arguments to justify the design of motivating learning situations and problems for students in realistic contexts close to their environment and the transformation of application problems into modelling problems by eliminating data from their statements and formulating an open-ended question.

1. Introduction

Current research trends in initial and continuing teacher education highlight the importance of deepening their professional competences for (whether pedagogical or curricular) decision making in the mathematics classroom (see Jacobs & Spangler, 2017; Stahnke et al., 2016 among others). This has led researchers in mathematics education to focus on the study of noticing (e.g., Mason, 1984), lesson study (e.g., R. Huang et al., 2019), and teaching reflection on practice (e.g., Breda, 2020), among other relevant topics. This study focuses on exploring two competencies that prospective primary education teachers must develop for use in different educational settings: mathematical modelling (for implementing in the classroom) and practical argumentation (for improving their teaching practice).

The current educational setting encourages the development of competencies that enable the use of mathematical knowledge and skills to solve real-world problems, where mathematical modelling plays an important role (Kaiser, 2020). Considerable research has been conducted on modelling from different approaches, and the resulting findings have demonstrated the benefits of incorporating this mathematical process and competency into the teaching of this subject for improving student learning (Blum, 2011) and for the development of creativity (Wang et al., 2023), among other aspects. For this reason, modelling has been incorporated into various educational curricula internationally (cf., J. Huang et al., 2021; Schoenfeld, 2013), into initial and continuing teacher education (Dalto et al., 2024; Ledezma et al., 2024), and into PISA as a part of the section on mathematical reasoning and problem-solving processes (Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, 2023). At a more general level, modelling has been considered as an indispensable element for the education of individuals capable of relating their knowledge to contemporary needs and demands (Maass et al., 2022), as in the case of education for sustainable development (see Bulut & Borromeo Ferri, 2025) or STEM education (see Hallström et al., 2023). (See further details in Section 2.1).

The current educational setting also encourages the development of competencies that allow teachers to reflect on their professional practice with the aim of improving teaching and learning processes (Praetorius & Charalambous, 2018; Prediger et al., 2022). In this context, practical argumentation has sparked growing interest among researchers in various fields (e.g., political science, critical discourse analysis, and argumentative theory) and plays a fundamental role in teaching reflection on practice. In the analysis of instances of teacher discussion and reflection on practice, the study of practical argumentation is important, among others, due to the following reasons: (a) It allows for a deeper understanding of teachers’ practical reasoning, that is, “the process of thought that ends in an action or an intention to act” (Fenstermacher & Richardson, 1993, p. 102), and (b) this type of argumentation provides tools for analysing how consensus is reached in these instances of discussion and reflection (Kinach, 2002). While different definitions of practical argumentation have been proposed in the specialised literature, this study addresses argumentation in which two types of arguments are produced: those which conclusions are actions to be performed and those based on actions considered in a discussion but which are not performed (Gómez, 2017). (See further details in Section 2.2).

1.1. Literature Review

In the literature on mathematics education, there is a wide range of studies that address argumentation and modelling independently; however, very few studies connect these two mathematical processes and competencies (Solar et al., 2025), specifically in teacher education.

Aydın Güç and Kuleyin (2021) reported a case study with 19 primary education students, who were organised into groups to develop a model eliciting activity. To this end, the authors analysed, on the one hand, the level of the groups’ modelling competencies (using the rubric designed by Tekin-Dede & Bukova-Güzel, 2018) and, on the other hand, the quality of the students’ argumentation (using the rubric designed by Cho & Jonassen, 2002). The results of the study made evident the impact of the quality of argumentation on the outcome of the students’ modelling processes, concluding that both competencies are directly proportional to their development.

Solar et al. (2022) reported a case study with two practising mathematics teachers (at the primary and secondary education levels, respectively), whose lessons were video-recorded as a part of a professional development programme. To this end, the authors analysed 10 classroom episodes from the perspective of the teachers’ argumentative orchestration (Solar et al., 2021) while they developed modelling tasks with their students. The results of the study made evident the different types of the presence and recurrence of argumentative orchestration throughout the modelling cycle, concluding that teaching strategies for promoting argumentation in the classroom have a positive impact on students’ modelling processes.

A common characteristic of the two studies described above is that both considered argumentation in terms of the different phases and transitions of a modelling cycle. In other words, they consider mathematical argumentation and its promotion during the students’ modelling process. For the development of this study, two works focused on the study of argumentation within the modelling process in the context of the initial teacher education were considered as references, which are described below.

Tekin (2019) studied the arguments constructed by four prospective primary education teachers while solving a modelling problem from the perspective of collective argumentation (Krummheuer, 1995). To this end, the author used Toulmin’s (1958/2003) model to structure and represent the arguments and the modelling cycle proposed by Blum and Leiß (2007). The results of this study made evident the emergence of the elements that make up an argument, in terms of Toulmin’s model, in the different transitions of the modelling cycle. The importance of the research conducted by Tekin (2019) for the study reported herein lies in the fact that while the author focused on the mathematical argumentation of the prospective teachers in solving a modelling problem, the use of Toulmin’s model for the study of this type of arguments and the consideration of prospective primary education teachers are highlighted.

Ledezma et al. (2022) studied the argumentation of a prospective secondary education teacher during the preparation of his master’s degree final project, where he justified the inclusion of modelling during his educational internship experience. To this end, the authors analysed, on the one hand, the reflection sessions with the prospective teacher from a pragma-dialectical perspective (van Eemeren & Grootendorst, 2004) and, on the other hand, the written reflection in the master’s degree final project using the diagramming technique (Guevara, 2011). The results of this study made evident the different types of knowledge inferred from the prospective teacher’s argumentation, forming a conglomerate of values, beliefs, and guidelines for action. The importance of the research conducted by Ledezma et al. (2022) for the study reported herein lies in the fact that although the authors do not explicitly speak of practical argumentation and their focus is on the knowledge of a prospective teacher, the structuring and representation of arguments and the inquiry into pedagogical decisions (guidelines for action) for the design and implementation of modelling in the classroom are highlighted.

The relevance of this study lies in its approach to mathematical modelling and practical argumentation in the context of primary school teacher education. While there is a tendency to consider modelling as a topic to be taught primarily in secondary and university education (Brady & Lesh, 2021), research in mathematics education has shown the benefits of addressing modelling not only from primary education (see English, 2003; Wei et al., 2022) but also from early childhood education (see Alsina & Salgado, 2022a, 2022b). Furthermore, it is important to note that in order to educate students in the development of a particular mathematical competency or process, teachers must have attained a certain level of competency and knowledge in that subject (cf., Climent, 2019; Fernández, 2019), and the teaching and learning of modelling in the classroom and in the initial and continuing teacher education are no exceptions (Blum & Borromeo Ferri, 2009). In addition to the above, the literature review has shown that there are very few studies that connect the study of argumentation to modelling. Therefore, this study aims to address the need to analyse practical argumentation in mathematical modelling, more specifically, in the context of designing application problems and their transformation into modelling problems in primary school teacher education.

1.2. Research Question and Objectives

Taking into consideration the importance of argumentation and modelling as relevant processes in mathematical activity, the relationship between the two for competency-based work within mathematical teaching and learning processes, and the limited literature that interrelates them, this study shares Tekin’s (2019) interest in delving deeper into the development of argumentation and modelling in the initial primary school teacher education and Ledezma et al.’s (2022) interest in inquiring the pedagogical decisions (guidelines for action) of prospective teachers in the design of modelling tasks for the classroom. However, this study addresses argumentation from the perspective of practical argumentation in the context of designing application problems and transforming them into modelling problems in primary school teacher education.

Therefore, this study seeks to answer the following research question: What practical arguments did prospective primary education teachers develop regarding the design of application problems and their transformation into modelling problems? To this end, the practical argumentation of prospective primary education teachers was analysed, who were taking a course on mathematical reasoning and activity in primary education, where problem solving and mathematical modelling were the two most relevant topics. The analysis of practical argumentation was focused on the design of application problems and their transformation into modelling problems. For this analysis, the scheme for structuring and representing practical arguments (see Figure 2) was used with those developed by the prospective teachers, and the modelling cycle from a semiotic–cognitive perspective (see Figure 1) was used to represent the solution plans to the modelling problems proposed by the prospective teachers.

2. Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework of this study is based on two references: mathematical modelling and practical argumentation. Thus, in order to provide a coherent answer to the research question posed, the practical argumentation of the prospective teachers studied is analysed, focusing on the design of application problems and their transformation into modelling problems. This section describes both theoretical references considered.

2.1. Mathematical Modelling

Within the literature on mathematics education, an important distinction is between the terms mathematical modelling and applications. While both are mathematical processes that denote all types of relationships between the “real world” and the “mathematical world” (Blum, 2002), modelling focuses on the transition from the “real world” to the “mathematical world”, centred on the mathematisation of reality, while applications focus on the transition in the opposite direction, centred on the mathematical object involved (Niss et al., 2007). This distinction serves as a terminological clarification taught to the prospective teachers in the context in which this research was conducted. Having said that, in terms of Pollak (2007), modelling is understood as the process beginning with an extra-mathematical situation posed as a problem. Then, this problem–situation is attempted (or expected) to be understood mathematically, until an image is formed, which will allow the solver to obtain some answers.

In the specialised literature, different representations have been designed to explain this process, known as modelling cycles (Borromeo Ferri, 2006), and different perspectives have emerged for its approach and characterisation (Abassian et al., 2020; Kaiser & Sriraman, 2006). While these differences are mainly due to the diversity of theoretical positions on modelling (Borromeo Ferri, 2013), in the case of modelling cycles, they tend to converge in similar phases (Geiger et al., 2018):

- Identification of the essential characteristics of a real-world situation;

- Simplification of the situation to develop a manageable model;

- Development of justifiable assumptions to accommodate missing information;

- Translation of the situation into a mathematical model (mathematisation);

- Generation of an initial solution from the mathematical model;

- Interpretation of the generated solutions in the initial context of the situation;

- Validation of a potential solution;

- Review of the process until an acceptable solution is established.

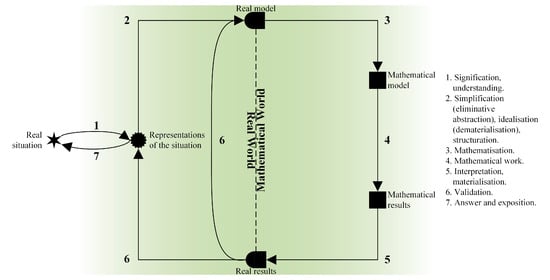

This study considers the modelling cycle from a semiotic–cognitive perspective, proposed by Ledezma (2024) (see Figure 1), since it is the cycle taught to the prospective teachers in the context in which this research was conducted.

Figure 1.

Mathematical modelling cycle from a semiotic–cognitive perspective. Source: Ledezma (2024, p. 282).

The cycle presented in Figure 1 can be framed within the educational perspective of modelling (in terms of Abassian et al., 2020; Kaiser & Sriraman, 2006), which is characterised by having a dual objective: on the one hand, to educate individuals who are competent in modelling (i.e., who know how to model) and, on the other hand, to educate individuals who are capable of developing a mathematical activity rich in processes during the modelling process (i.e., who do mathematics through modelling). Previous studies have analysed the mathematical activity underlying the modelling process, concluding that modelling cannot be worked on in isolation as a mathematical competency and process (see Ledezma et al., 2023) due to a “process–product” duality (see a more in-depth discussion in Font et al., 2013). Therefore, the modelling process as a whole allows for the development of the mathematical modelling competency (see Niss & Højgaard, 2019).

In structural terms, the cycle in Figure 1 provides a structure of phases (named throughout the cycle) that allows for the explanation of the modelling process, as well as the description of the mathematical activity underlying this process (Ledezma, 2024). The transition between the phases of this cycle is carried out through transitions (numbered to the right of the cycle), which correspond to the modelling of sub-competencies necessary to solve this type of problem (see Greefrath & Vorhölter, 2016; Kaiser, 2007; Maaß, 2006). Furthermore, this cycle differs from other proposals in that it does not represent the modelling process in a set-theoretic manner (cf., Blum & Leiß, 2007; Borromeo Ferri, 2018; Zbiek & Conner, 2006 among others) but rather proposes a nuanced transition between the “real world” and the “mathematical world”. A more detailed example of how this cycle explains the modelling process in a problem–situation can be found in Ledezma (2024, pp. 284–286).

Working with modelling in the classroom is typically developed in small groups of students who are presented with a real-world problem situation that they must mathematise (Doerr & English, 2003; Shahbari & Tabach, 2019). Given the cyclical nature of the modelling process, where both the context of the problem–situation and the mathematical aspects involved impact the generated mathematical model (Blomhøj, 2004; Borromeo Ferri, 2007), modelling tasks allow for different paths to obtain a plausible solution that is consistent with the context of the problem–situation initially posed (English, 2003; Lesh & Doerr, 2003). This problem–situation, known as a modelling problem, must meet certain characteristics to be considered as such (Borromeo Ferri, 2018; Maaß, 2007, 2010):

- It must be open and complex so that the situation is not limited to a specific answer and/or procedure, and the problem solver attempts to understand the context of the situation in order to select relevant data (or seek additional information);

- It must be realistic and authentic so that the situation includes real-world elements and its formulation is consistent with a plausible situation that may have occurred in the past, is occurring in the present, or could occur in the near future (Palm, 2007), even when this situation has not been created with educational purposes (Vos, 2011);

- It must be a problem so that it cannot be solved by applying known algorithms or routine procedures (Schoenfeld, 1994) and that can be solvable through a modelling process, which implies using all the phases of a cycle for its solution.

These six characteristics are a part of the content taught to the prospective teachers in the context in which this research was conducted.

It is important to stress that application problems and modelling problems differ in scope and affordances. In terms of Smith and Stein (1998), both types of problems are considered to be cognitively demanding tasks but with different levels of complexity. On the one hand, application problems seek to establish procedures with connections that “require some degree of cognitive effort (…) general procedures may be followed, (but) they cannot be followed mindlessly” (Smith & Stein, 1998, p. 348). On the other hand, modelling problems seek to do mathematics, which “require(s) considerable cognitive effort and may involve some level of anxiety for the student because of the unpredictable nature of the solution process required” (Smith & Stein, 1998, p. 348). Therefore, in the context of this study, the transformation of application problems into modelling problems encourages the transition between two levels of high cognitive demand, both in their design and solution, by the prospective teachers studied.

2.2. Practical Argumentation

Within the literature on mathematics education, several authors have considered the development of argumentation as a crucial aspect for the learning of this discipline (see Nussbaum, 2008; Singletary & Conner, 2015; Yackel, 2002 among others). Similarly, various curriculum documents consider it relevant to work on argumentation in the classroom as a part of the mathematical subject (for example, the Department of Education of Catalonia (2022), the Head of State (2020), and the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (2000, 2014) among others), which has led, as with modelling, to its consideration as a competency (Rapanta et al., 2013). In the Theory of Communicative Action, Habermas (1981/1984) defines argumentation as “that type of speech in which participants thematise contested validity claims and attempt to vindicate or criticise them through arguments” (p. 18). This author adds than an argumentation contains reasons that are systematically linked to a claim to validate a particular statement of a problematic nature.

Among the types of argumentations studied, one that has sparked growing interest among researchers is practical argumentation, as it has been addressed in political science (see Elster, 1998), critical discourse analysis and argumentative theory (see Fairclough & Fairclough, 2012), and various educational contexts (see Rapanta & Macagno, 2016). While different definitions of practical argumentation have been proposed in the specialised literature, depending on the perspective from which this process is approached (Macagano & Walton, 2018), this study considers two complementary definitions of practical argumentation: one proposed by Lewiński (2018), who defines it as “argumentation aimed at deciding on a course of action” (p. 219), and the second proposed by Gómez (2017), who defines it as “argumentation aimed at carrying out the speech act of deciding and, in a derived sense, proposing” (p. 228, the authors’ translation). Both definitions consider the existence of an action in the arguments to be a central element.

An important distinction to consider in this study is between mathematical argumentation and practical argumentation: The former emerges from mathematical practices, where arguments of inductive, abductive, analogical, and deductive natures are generated, while the latter emerges from didactic practices, where actions planned or performed in the classroom are generated (Sol et al., 2025). Another important distinction to consider in this study is between theoretical argumentation and practical argumentation: The former allows us to answer questions like ‘is p true?’ (where p is a description of the world), while the latter allows us to answer questions like ‘what should A do in a situation x?’ (where A is the name or description of an agent, and x is the description of a problem–situation) (Gómez, 2017).

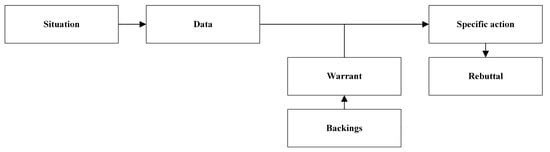

As in the case of modelling, in the specialised literature, different representations have been designed to structure practical arguments, known as argumentative schemes (cf., Atkinson & Bench-Capon, 2007; Fairclough & Fairclough, 2012; Walton et al., 2012 among others). However, this study considers the scheme for structuring and representing practical arguments proposed by Sol et al. (2025) (see Figure 2), as it is the analytical tool utilised in this research.

Figure 2.

Scheme for structuring and representing practical arguments. Source: Adapted from Sol et al. (2025, p. 3719).

The scheme presented in Figure 2 is derived from an adaptation of Toulmin’s (1958/2003) model to structure and represent practical arguments. To this end, Sol et al. (2025) take as a basis the structure of a practical argument described by Fenstermacher and Richardson (1993), which consists of four premises (value, stipulative, empirical, and situational) and an action or intention to act. Then, the authors related this characterisation to Toulmin’s model for structuring practical arguments and representing the relationship between their elements (Sol et al., 2025). According to this model, an argument is made up of claims (statements that are sought to be validated), data (information on which the claim or conclusion is based), warrants (propositions that allow inferences to be made and connect the data to the claim), rebuttals (situations in which the warrant is invalid), modal qualifiers (statements that indicate the strength of the warrant in the data–claim relationship), and backings (justifications that support the warrants) (Toulmin, 1958/2003). Thus, this adaptation entailed the following two modifications to the original Toulmin model:

- The claim became a specific action;

- The backings were considered as two types of knowledge (scientific and generated by practice).

A more detailed example of how this scheme structures and represents practical arguments in the context of teaching reflection on practice can be found in Sol et al. (2025, pp. 14–17).

3. Methodological Aspects

This study followed a qualitative research methodology from an interpretative paradigm (Cohen et al., 2018), which consists of an intrinsic case study (Stake, 2005). Thus, in order to provide a coherent answer to the research question posed, a case study was conducted with prospective teachers who were taking a course on mathematical reasoning and activity in primary education, where problem solving and mathematical modelling were the two most relevant topics. This section presents the research context, describes the study subjects, and explains the data collection and analysis techniques.

3.1. Research Context

This research was conducted within the Bachelor’s Degree Programme in Primary Education Teaching, taught by a Spanish university during the 2024–2025 academic year. This degree programme offers basic and specific didactic training in the areas of knowledge and disciplines established at the stage of primary education, in the organisational and management principles of schools, and in the physical, emotional, and intellectual development processes specific to this educational stage. Furthermore, this degree programme allows for its completion with specialisations in attention to diversity, school libraries, and music education, among others. The Bachelor’s Degree Programme in Primary Education Teaching lasts for four academic years and is worth a total of 240 credits (according to the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System, ECTS). Of these credits, 60 correspond to basic training, 102 to compulsory training, and 27 to optional training; forty-five correspond to educational internship experiences and six credits to the bachelor’s degree’s final project.

Among the compulsory training courses, the “Mathematical Reasoning and Activity in Primary Education (MRAP)” course is taught during the second semester (spring) of the second academic year. MRAP is the first mathematics course that the prospective primary education teachers must take in this degree programme, followed by “Didactics of Mathematics I” in the third academic year and “Didactics of Mathematics II” in the fourth academic year. The MRAP course lasts for one semester and earns a total of 6 ECTS credits; lessons are held twice a week, lasting for two hours each, and class sizes consist of between 30 and 45 students each. The learning objectives of the MRAP course include the following:

- To understand mathematics as a tool for interpreting and modelling the world around us;

- To identify, understand, and use the different languages of elementary mathematics;

- To understand the mathematics that will allow prospective teachers to make sense of the content of primary education in order to teach it;

- To recognise problem solving as the core of the mathematical activity in school;

- To realise that commonly used forms of reasoning are often applicable to elementary mathematics.

In addition to theoretical lectures, the methodology of the MRAP course includes problem solving, classroom activities, the use of various didactic materials, and reflection on classroom episodes. A fundamental aspect of this course is the institutionalisation of discussions with the class group, which allows for a clearer relationship between the findings of research in mathematics education and teaching practice. The students are also required to organise themselves into work groups of three to six members each, both to develop classroom activities and to produce the written reports with an oral presentation of the course—this division is justified by the number of students in each class group.

Regarding the teaching plan of the MRAP course, its structure consists of the following four thematic blocks:

- Thinking about mathematics;

- Problem solving;

- Numbers and operations;

- Information processing and probability.

The first two thematic blocks are developed during the first part of the course (February–March) and the following two blocks during the second part (April–May). The assessment system of the MRAP course includes ten classroom activities (five throughout each part of the course), two written reports with oral presentations (one at the end of each part of the course), and two exams (one at the end of each part of the course).

While the four thematic blocks listed above are fundamental to the development of the MRAP course, there is also some leeway for the professors in charge of the student groups to make any modifications they deem appropriate based on their pedagogical criteria. These considerations can be justified, for example, by the students’ skill/knowledge level, assessment results, professors’ experience in teaching the thematic blocks, and their research interests, among other reasons. During the 2024–2025 academic year, the professor in charge of two of the groups of the MRAP course (the first author of this article) made some modifications to the thematic block “2. Problem solving”, with the aim of addressing the teaching of mathematical modelling, as described in the following section.

3.1.1. The Teaching of Mathematical Modelling

The thematic block “2. Problem solving” took place during March of the 2024–2025 academic year and lasted for three weeks (six class sessions). The block began with the work groups of prospective teachers solving some primary education-level mathematical exercises and problems. Once this first stage was completed, the professor in charge of the MRAP course continued with a discussion with the class group about the similarities and differences between the mathematical exercises and problems, and some mathematical problem productions solved by primary education students were commented. Finally, the discussion and comments from the prospective teachers were institutionalised using the definitions proposed by Schoenfeld (1985). The choice of this author’s definitions is justified both by their wide acceptance in mathematics education and by the structuring of the MRAP course syllabus; however, the prospective teachers were told that they may find definitions from other authors (for example, Liljedahl & Santos-Trigo, 2019) but which point in similar directions.

In terms of Schoenfeld (1985), a mathematical exercise is a routine task involving familiar procedures, where the solver has a well-defined pathway to the solution, requires little strategic thinking, and its function is to reinforce procedural fluency rather than fostering exploration and creativity. On the other hand, a mathematical problem is a situation where the pathway to the solution is not known a priori, where the solver requires the exploration and assessment of strategic choices rather than familiar procedures, and this type of mathematical activity is considered as central to develop authentic mathematical thinking.

Once this second stage was completed, the professor in charge of the MRAP course presented the characteristics of mathematical problems and two heuristics to the prospective teachers: Pólya’s (1945) method for solving problems and Schoenfeld’s (1985) method for analysing this solution. Problem solving was also addressed from a curricular perspective, explaining to the prospective teachers how this mathematical process is presented in the current educational curriculum. More specifically, the Basic Education Curriculum of Catalonia presents problem solving as one of the specific competencies in the area of mathematics as follows:

Specific Competency 2: To solve problems by applying different techniques, strategies, and forms of reasoning to explore and share different ways of proceeding, obtaining solutions, and ensuring their validity from a formal point of view and in relation to the context presented and generating new questions and challenges.(The Department of Education of Catalonia, 2022, p. 181, authors’ translation.)

Although the Basic Education Curriculum of Catalonia does not explicitly address modelling in primary education, another specific competency in the area of mathematics states that problem solving should not only be addressed in intra-mathematical contexts but also in extra-mathematical contexts as follows:

Specific Competency 5: To use connections between different mathematical ideas, as well as identify the mathematics involved in other areas or with everyday life, interrelating concepts and procedures to interpret diverse situations and contexts.(The Department of Education of Catalonia, 2022, p. 184, authors’ translation.)

Once this third stage was completed, the professor in charge of the MRAP course institutionalised the curricular aspects of problem solving according to the classification made by Blum and Niss (1991) as follows:

- Applied mathematical problems: Those where the situation and the question(s) belong to some segment of the real world, that is, everything outside mathematics, such as other fields of knowledge or everyday life;

- Purely mathematical problems: Those where the situation and the question(s) are totally immersed in the mathematical world, and although they may emerge from applied mathematical problems, once they leave the real world, they also cease to be applied.

To illustrate this classification, the professor in charge of the MRAP course presented the following two problems to the prospective teachers (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Presentation of two mathematical problems to the prospective teachers.

After presenting the two problems in Table 1, the prospective teachers were asked to solve them in their work groups and present their solution plans to the class group. Although the solutions from the different work groups were similar, the consensus reached within the class group was that the first problem (A clear day at the sea) was easier and quicker to solve than the second problem (Boston Light).

Once this fourth stage was completed, the professor in charge of the MRAP course continued with a discussion with the class group about the similarities and differences in the formulation of the two problems in Table 1. Finally, the discussion and comments from the prospective teachers were institutionalised, presenting the definition of mathematical modelling, its differentiation from mathematical applications, the characteristics of this type of problem (see Section 2.1), and the modelling cycle in Figure 1. To illustrate how the modelling cycle works, a solution to the Boston Light problem was presented.

Once this fifth stage was completed, the professor in charge of the MRAP course addressed the transformation of application problems into modelling problems for the primary education classroom, using two problems situated in a similar context (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Presentation of an application problem and a modelling problem to the prospective teachers.

As in the previous stage, after presenting the two problems in Table 2, the prospective teachers were again asked to solve them in their work groups and present their solution plans to the class group. Although the solutions from the different work groups were similar, the prospective teachers now expressed greater clarity about how to approach solving a modelling problem and what elements to consider when doing so. Finally, the professor in charge of the MRAP course institutionalised the way of presenting both statements using strategies for transforming application problems into modelling problems (see Borromeo Ferri, 2018, p. 58), in this case, adapted to the primary education classroom:

- Reduce the number of data provided by the statement of the problem–situation or omit specific exercises that lead to a specific mathematical procedure;

- Modify the context of the problem–situation, if necessary, to make it more authentic and/or closer to the student’s environment;

- Formulate an open-ended question;

- Define the tools the students can use to solve the problem–situation (internet, software, teaching materials, etc.).

The experience described in this section occupied five of the six class sessions devoted to the thematic block “2. Problem solving”. Thus, in the sixth class-session, work was devoted to adapting a learning situation (previously designed by the prospective teachers) to incorporate problem solving and mathematical modelling into primary education, as described in the following section.

3.1.2. Classroom Activity and Written Report with Oral Presentation

As explained in Section 3.1, the assessment system of the MRAP course includes, in addition to the two exams, the development of ten classroom activities (five throughout each part of the course) and the preparation of two written reports with oral presentations (one at the end of each part of the course). This section explains both assessment instruments.

Due to its competency-based approach, the Spanish curriculum uses the term learning situation (LS) to refer to “situations and activities that involve the student deployment of actions associated with key and specific competencies and that contribute to their acquisition and development” (The Ministry of Education and Professional Training, 2022, p. 24388, authors’ translation). In other words, LSs are sets of activities designed by the teacher to work on the key and specific competencies of each area (subject) of the curriculum. These activities are sequenced around a meaningful context for students and consider aspects, such as, for example, student diversity, the use of active–participatory methodologies, and continuous and formative assessment (The Department of Education of Catalonia, 2022).

During the development of the thematic block “1. Thinking about mathematics”, the professor in charge of the MRAP course presented the Basic Education Curriculum of Catalonia (The Department of Education of Catalonia, 2022) to the prospective teachers, specifically, in the area of mathematics. One of the classroom activities required of the prospective teachers was the design of an LS in their respective work groups. To this end, they had to select a curricular knowledge (mathematical content) to work on at a specific educational level, define the learning objectives, and describe the specific competencies they intended to develop with the proposed activities. Since this was the prospective teachers’ first experience with the mathematics curriculum, the purpose of the classroom activity was to familiarise them with the key curricular aspects of the subject, without providing in-depth information. Similarly, while both the LS and the proposed activities were required to be created by the work groups themselves, the prospective teachers were also allowed to modify the LS and activities available at the Department of Education of Catalonia’s website (among other internet sources). The classroom activity concluded with a brief oral presentation of the work groups’ LS to the class group.

Once the experience described in the previous section was completed, the professor in charge of the MRAP course devoted the sixth class-session of the thematic block “2. Problem solving” to resume work with the LS developed at the end of the thematic block “1. Thinking about mathematics”. The objective was not to adapt these LSs to incorporate problem solving and mathematical modelling in primary education. To this end, the professor established the following criteria for the preparation of a written report:

- Indicate the educational level for which the proposal of the LS was intended;

- Indicate and justify the learning objectives, curricular knowledge, and specific competencies considered in the LS;

- Describe the classroom management during the LS (the number of class sessions, roles of the teacher and students, and timing of classroom activities);

- Design two application problems related to the LS context, justify their design (based on the curricular aspects of the LS), and describe their hypothetical solution plan;

- Transform both application problems into modelling problems, justify their design (based on the curricular aspects of the LS), and describe one hypothetical solution plan for each one;

- Have a maximum length of 20 pages (including the cover, index, contents, references, and appendices).

Regarding the criteria for the oral presentation, the work groups were to summarise the aspects listed above, placing a special emphasis on the design of the application problem, its transformation into a modelling problem, and the solution plans for both. The maximum length of the oral presentation was 20 min per work group.

During this sixth class-session of the thematic block “2. Problem solving”, in addition to the professor in charge of the MRAP course, a professor (the second author of this article) in charge of the educational internship experiences of the prospective primary education teachers was also present in the classroom. Thus, both professors interacted with the work groups, providing feedback on the proposed problems and their appropriateness within the respective LSs. During this sixth class-session, the day and order of the presentation of the work groups were also randomly drawn; however, regardless of the resulting distribution, the written reports and oral presentations (documents in .pdf format) had to be uploaded to a space on the virtual campus designated for assessment on a date prior to the two days of presentations.

3.2. Study Subjects

During the two class sessions devoted to the oral presentations of the work groups of prospective teachers, both the professor in charge of the MRAP course and the professor in charge of the educational internship experiences (the first and second authors of this article) were present. Both professors had access to the written reports and oral presentations (documents in .pdf format) of the ten work groups. Five work groups presented in each class session, after which the professors provided feedback to each work group according to the previous reading of their written reports and the assessment of their presentations.

In a meeting among the four authors of this article, the written reports and the evaluative comments on the oral presentations were reviewed, leading to a consensus being reached to select three of the ten work groups of prospective teachers as study subjects. This selection was justified by the following criteria of clarity and detail:

- The explanation of the LS proposal in the written reports (articulation among learning objectives, specific competencies, and curricular knowledge);

- The explanation of the application and modelling problems designed (the statement of the problems, justification of their design, and description of hypothetical solution plans);

- The fluency of the prospective teachers during their oral presentations (the clear handling of objectives, design, and content of their LSs).

The three selected work groups were contacted jointly to explain the purpose of this study and invite them to participate as study subjects, to which they enthusiastically agreed. The request for their informed consent included, in addition to a description of the study’s purposes, a request to apply a questionnaire and an interview (both described in Section 3.3).

It should be noted that the members of the three work groups only have teaching experience from their first course of educational internships (Educational Internships I), in which they participated as active observers at primary education schools. The proposals of the three selected work groups of prospective teachers are described in the following paragraphs.

3.2.1. Group 1

The first group is made up of five prospective teachers (all females), who designed an LS titled “A cake with a lot of history” for fourth-grade primary education students (aged 9–10). This LS is contextualised in a party for the school’s 50th anniversary, for which the students must prepare a cake with the help of the school’s cooks. The extra-mathematical considerations of the LS include the number of guests, their possible food intolerances, the adaptation of a basic recipe, the quantity of the ingredients needed for its preparation, and the preparation of a budget for the purchase of these ingredients. The curricular knowledge addressed include number sense (counting, quantity, operations, relationships, and financial education) and measurement sense (magnitude, estimation, and relationship). The LS was designed to be implemented in five class sessions.

3.2.2. Group 2

The second group is made up of six prospective teachers (all males), who designed an LS titled “End-of-year trip” for sixth-grade primary education students (aged 11–12). This LS is contextualised in the planning and organisation of the end-of-year trip, for which the students must prepare a budget. The extra-mathematical considerations of the LS include the distance to the travel destination, duration of the trip, transport costs, accommodation, and activities. The curricular knowledge addressed include number sense (operations, relationships, and financial education), measurement sense (magnitude), and spatial sense (location and interpretation). The LS was designed to be implemented once a week over the course of a month.

3.2.3. Group 3

The third group is made up of four prospective teachers (one female and three males), who designed an LS titled “The market of numbers” for sixth-grade primary education students (aged 11–12). This LS is contextualised in the simulation of a market, for which the students must assume different roles (coordinators, calculators, and accountants) within their work groups to calculate purchase costs and estimate budgets. The extra-mathematical considerations of the LS are based on the supply and demand of the products at the market. The LS was designed to be implemented over the course of one week of mathematics lessons.

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis Techniques

For data collection, in addition to the written reports and oral presentations described above, a questionnaire was applied, and a semi-structured interview was conducted with the study subjects. This section begins with a description of these two data collection instruments and concludes with the explanation of the data analysis procedure.

3.3.1. Questionnaire

Once informed consent was obtained from the study subjects, a questionnaire was designed to explore the pedagogical decisions made by the three work groups. Thus, the questionnaire consisted of five questions, which addressed the design of the LS, the two application problems, and their transformation into modelling problems. The questions in this questionnaire were as follows:

- Why did you choose this context for your learning situation?

- What were the most important elements you considered when transforming an application problem into a modelling problem?

- What were the easiest and most difficult characteristics to meet when transforming an application problem into a modelling problem?

- What prior knowledge (as undergraduate students) did you consider when designing these problems?

- What changes did you make to your initial learning situation to incorporate the application and modelling problems?

The questionnaire was e-mailed to a representative of each work group and was to be completed by the study subjects in their respective groups and returned completed within a maximum of three days.

3.3.2. Semi-Structured Interview

Once the questionnaires were received from the study subjects, a semi-structured interview was designed to explore the practical arguments of the three work groups. Although the questions in this interview were, in principle, the same as those in the questionnaire, they were posed differently to the study subjects interviewed to delve deeper into their answers to the questionnaire that were unclear or that caught the researchers’ attention. For example, if the range of responses to question 3 of the questionnaire applied to Group 1 was very narrow, the same question was posed to the study subjects interviewed, but in a different way, to explore the issue in greater detail. Similarly, if the responses to question 1 of the questionnaire applied to Group 3 were very detailed, the procedure for asking the same question was repeated. In methodological terms, first applying a questionnaire and then an interview is an instance that favours the emergence and identification of practical arguments (cf., Ledezma et al., 2022).

One of the researchers (the second author of this article) conducted the interview with two study subjects from each work group, depending on their time availability. These interviews lasted approximately 20–25 min each and were audio recorded and transcribed using the Microsoft Word® feature, which was available through an institutional subscription. The resulting transcripts were reviewed by two other researchers (the first and third authors of this article).

3.3.3. Data Analysis Procedure

For data analysis, a methodology similar to that used by Sol et al. (2025) for the analysis of episodes of practical argumentation was followed. First, each author reviewed the answers of the questionnaires and the transcriptions of the audio-recorded interviews to identify what constituted an episode of practical argumentation. To this end, the following criterion was considered: text segments where the study subjects “attempt to give reasons for or against the decision (the work) group should make regarding a proposal” (Gómez, 2017, p. 241, authors’ translation).

Second, the four authors reviewed the episodes selected by themselves and reached a consensus on which ones to focus their analysis on. To this end, the following more specific criterion was considered: an episode that includes an agreement among the study subjects on one or more actions that influenced the design of application problems and their transformation into modelling problems. Thus, the analysis focused on nine of the seventeen episodes of practical argumentation initially selected, as they provided the most information for its structuring.

Third, the elements that made up a practical argument were identified in the selected episodes (according to the description in Section 2.2). To structure these practical arguments, according to the answers of the study subjects to the questionnaires applied and complementing them with the dialogues during the interviews conducted, the procedure was as follows:

- Identification of specific actions;

- Identification of data;

- Formulation of a warrant (often implicit in the discourse) with its modal qualifiers (words that give strength to the warrant);

- Search for backings for this warrant (from the study subjects’ knowledge or experiences);

- Search for rebuttals (cases where the warrant cannot connect the data to the specific actions).

Once the practical arguments were structured, they were represented using the scheme presented in Figure 2.

Finally, the solution plans to the modelling problems were represented according to the cycle presented in Figure 1. To this end, the solution plans proposed by the study subjects in their written reports were reviewed and then reinterpreted in terms of the phases of the cycle considered as a theoretical reference. Although the study subjects did not explicitly use the cycle in Figure 1 to represent their solution plans, the structure of the cycle itself allows for this reinterpretation due to the clear distinction between its phases and transitions (Ledezma, 2024). Furthermore, this type of representation has been used in various studies focused on analysing the phases an individual goes through to solve a modelling problem (cf., Borromeo Ferri, 2007, p. 2087; Greefrath & Vorhölter, 2016, p. 11; Ledezma et al., 2022, p. 30 among others) or to propose ideal solution plans for this type of problem (see Ledezma, 2024, pp. 284–286).

4. Presentation and Analysis of Results

This section presents and analyses the results of this study in two sections. The first section structures and represents the practical arguments developed by the study subjects within the episodes of practical argumentation identified (using the scheme in Figure 2). The second section describes and represents the solution plans to the modelling problems proposed by the study subjects (using the cycle in Figure 1).

4.1. Structure and Representation of Practical Arguments

This section presents some practical arguments developed by the study subjects, which were structured based on the answers collected from the questionnaires applied and complemented by the dialogues from the interviews conducted.

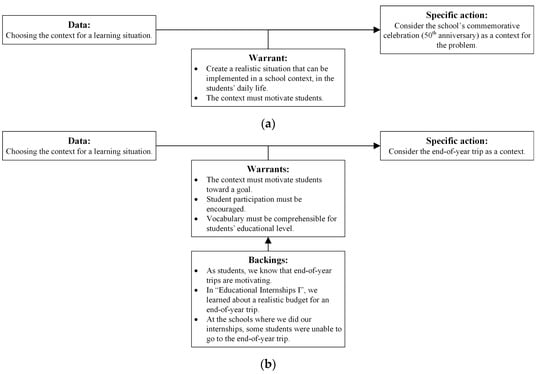

The first question in the questionnaire and interview was: Why did you choose this context for your learning situation? The answers to the questionnaire applied to the study subjects addressing this first question were as follows:

- Group 1: We decided that context because we thought that a commemorative party for the school’s 50th anniversary was a motivating factor for primary school students. In this way, we created a real situation that could be implemented in a school setting of the students’ everyday life. Furthermore, it encompasses all the members of the school community, thus fostering a cohesive and meaningful environment for everyone;

- Group 2: We believed it was an ideal context where students would feel involved in the process and, at the same time, motivated by a goal, like the end-of-year trip;

- Group 3: We considered that the context in which these contexts are applied is suitable (sic) for an educational setting and a context in which students can apply it to real life. It is not a strange or a different context; it is a supermarket, a setting in which each of these students knows what it is or has gone to at least once. This facilitates the interpretation of the statement of the problem.

As observed in the answers to the first question of the questionnaire, those of Groups 1 and 2 highlight the importance of student motivation, while those of Group 3 emphasise the importance of using a context close to the students that facilitates them to interpret the statement of the problem.

Regarding the interview conducted with the study subjects, some excerpts of dialogue addressing this first question were as follows:

- (Group 1): (this question was not explored in depth during the interview).

- Line 003—Speaker H (Group 2): (…) it was something we had experienced… the trip… and we thought, “what do we think our students might like in the future?” We tried to relate it in some other way and to make it motivating; it is something that also involves them. That is, this work was based on the fact that at the end of the course, they had to do, for example, with the best salary (budget), considering the accommodation and the percentage. In the end, we also decided on a lot of that because we thought it was appropriate in the context because we are also teachers.

- Line 002—Speaker À (Group 3): We posed a mathematical problem (application problem), and in the future, we thought about posing it in an elementary school classroom. The mathematical problem (application problem) was, more than anything, about numbers… data, and we realised that removing that data and putting them into the same context would result in the modelling problem. But that is what it is; above all, as future teachers, we wanted to focus on an area where students could bring out mathematics, as such, in a more everyday way.

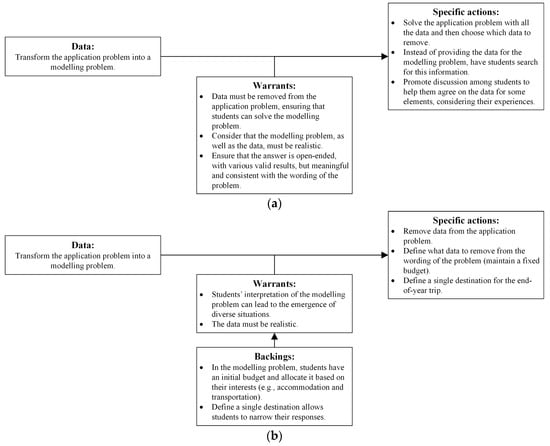

The answers to the questionnaire were complemented with those from the interview conducted, from which the practical arguments represented in Figure 3 were structured.

Figure 3.

Structuring and representation of the practical arguments developed by the study subjects in (a) Group 1; (b) Group 2; (c) Group 3. Source: Authors’ creation.

A practical argument worth highlighting is that developed by the study subjects in Group 2 (Figure 3b), which shows the reasons for choosing the end-of-year trip as the context for their LS. In the argument’s warrants, it is observed that these prospective teachers considered three aspects related to students, namely, motivation, participation, and understanding. Furthermore, the three warrant’s backings relate to their experiences as primary education students (first backing) and as internship students in schools at this educational level (second backing).

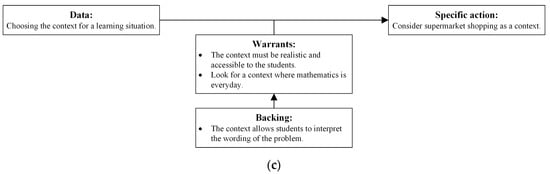

The second question in the questionnaire and interview was: What were the most important elements you considered when transforming an application problem into a modelling problem? The answers to the questionnaire applied to the study subjects addressing this second question were as follows:

- Group 1: The elements we took into account when creating the modelling problem were the following: eliminating some of the data from the application problem, contextualising the statement (of the problem) so that it is applicable in the real world, and ensuring that the answer is open (there are different valid results but with meaning and coherence with the problem);

- Group 2: The most important element we detected was that we had to remove the data we were offering to them (the students), so they could interpret the statement (of the problem) to obtain different responses among the students;

- Group 3: First of all would be the possibility of choosing different solutions, which, although there is only one in which it is optimised to the maximum, (the students) may have some margin to be able to consider going to and choosing different stores in the market. Afterwards, they (the students) should justify their decision to ensure the learning process continues, thus reasoning their choice and allowing it to serve as a learning experience. We also sought to simulate the activity with a real-life situation, so they (the students) could relate it and apply it to their daily lives as meaningful learning. Finally, look for different ways to represent the offerings of the market’s stores, along with a group discussion about the whys for each choice.

As observed in the answers to the second question of the questionnaire, those of Groups 1 and 2 highlight the importance of removing certain data from the application problem to formulate the modelling problem. However, the answers from all three groups agreed on two aspects: first, that the proposed modelling problems should allow for different results (or solutions/responses) and, second, that the statements of these problems should be understandable to students.

Regarding the interview conducted with the study subjects, some excerpts of dialogue addressing this second question were as follows:

- Line 003—Speaker S (Group 1): Yes, in the end, what we decided was, okay, with this data plus some data that would be more realistic for students, such as the shopping list. It is true that supermarkets have different prices, so setting a fixed price for the problem did not seem to be realistic enough. So, we decided to let them (the students) find the information themselves, so it could be more realistic.

- Line 009—Speaker H (Group 2): Yes, in the application (problem), we gave them (the students) almost all the data. I mean, there are EUR 3000, or a little more, I think, and 50% is divided into vehicles, that is, transportation, 10% into “serveis” (services), because we did it in Catalan, and “quin percentatge falta” (what percentage is missing?) So, they were simple operations. And what did we do? For the modelling (problem), we took that same base salary (budget), or varied it a little, and asked them, “how would you do it so that it is distributed fairly and makes sense?” That is, I am not going to spend EUR 2900 on transportation and then have to live in a room with 25 other students. What we wanted was for them (the students) to also search for and think about ways….

- Line 005—Speaker T (Group 3): When it came to transferring it, the day we did it (the problems) in class at the beginning of the course, the issue was about not giving all the unknowns, so students could solve the problem without the statement itself telling them what to do. It is true that everyday problems have two or three unknowns, which already give you the result. However, in the modelling problem, you are missing at least one of them, and based on the information you have already acquired in the statement, you solve to obtain the remaining unknown.

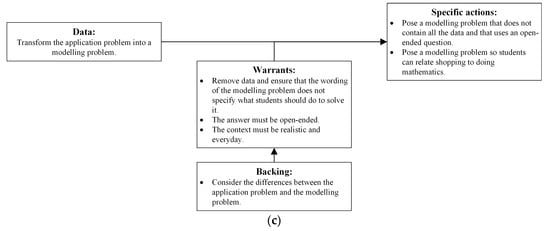

The answers to the questionnaire were complemented with those from the interview conducted, from which the practical arguments represented in Figure 4 were structured.

Figure 4.

Structuring and representation of the practical arguments developed by the study subjects in (a) Group 1; (b) Group 2; (c) Group 3. Source: Authors’ creation.

A practical argument worth highlighting is that developed by the study subjects in Group 3 (Figure 4c), which shows the aspects considered for transforming an application problem into a modelling problem. In the argument’s warrants, it is observed that these prospective teachers considered four aspects, namely, the removal of data, the formulation of the statement, the openness of the response, and the choice of the context. Furthermore, the warrant’s backing allows for distinguishing between an application problem and a modelling problem. Finally, the second specific action expresses the intention for students to relate the activity of shopping in the supermarket with mathematics.

The third question in the questionnaire and interview was: What were the easiest and most difficult characteristics to meet when transforming an application problem into a modelling problem? The answers to the questionnaire applied to the study subjects addressing this third question were as follows:

- Group 1: The hardest part was getting the answer to be open-ended. We tried different ways of approaching this response until we came up with a statement (of the problem) that matched the result we wanted from the students. The easiest part, so to speak, was applying our idea to the real world, since it was already related to it;

- Group 2: The easiest (characteristic) was to remove data, since it was easy to know which ones we could remove so that the exercise (sic) continued to make sense, but the most difficult (characteristic) was rewriting the statements (of the problems); it was a little more complicated for us, since, having fewer data, it was difficult to make a statement (of the problem) with a question and make it understandable without the data;

- Group 3: The simplest part of the problem would be relating the activity to a market, since most of the children will have gone shopping with their parents and will have the memory with which we will work in order to be able to use the offers, prices, …. The most complex part would be creating the different possible solutions, which, although not very difficult, just because of the issue of checking operation by operation to know the price of each food, can be the most delicate part for the student.

As observed in the answers to the third question of the questionnaire, those of Groups 1 and 3 agreed on two relevant aspects: on the one hand, the difficulty of posing an open-ended question, and on the other, the relative ease of elaborating a problem of a realistic context. Regarding the latter, only Group 3’s answer referred to the authenticity of the problem. For its part, Group 2’s answer indicated that the greatest challenge was writing a statement of the problem that was understandable to students, despite not having to rely on data to solve it.

Regarding the interview conducted with the study subjects, some excerpts of dialogue addressing this third question were as follows:

- Line 026—Speaker P (Group 1): (…) it had to be easy to understand because, after all, they are elementary school students. For example, when we finish it (the statement of the problem), we read it and do it (solve it) quickly. But it is not the same if we do it (solve it) as if elementary school students do it (solve it). So, it (the problem) has to be well explained and contain keywords, so it is easy to understand.

- Line 020—Speaker H (Group 2): (…) the easiest one (characteristic) was removing elements, and the most difficult one (characteristic) was, with the elements we removed, trying to create a statement (of the problem) that we also thought they (the students) would understand. Of course, because, perhaps, what I, at a certain age, might think, a fourth grader is not going to understand.

- Line 021—Speaker A (Group 2): By removing the data, we also knew that when there were data in a statement, it might be easier to follow a flow and finish the problem (sic). But without data, they (the students) might become lost.

- Line 018—Speaker À (Group 3): Of course, because not only that, then you say, okay, that is what (speaker T) says, EUR 15, and one has spent EUR 16. It is about making the child understand that the solution is not wrong, but as future teachers, how do we explain this reasoning on a mathematical level, so they (the students) understand it? So, that is one of the difficulties we also pose. But if that is what (speaker T) has explained a little, to make them (the students) understand that the one who has spent EUR 15 at market (store) X and EUR 16 at market (store) Y is not bad.

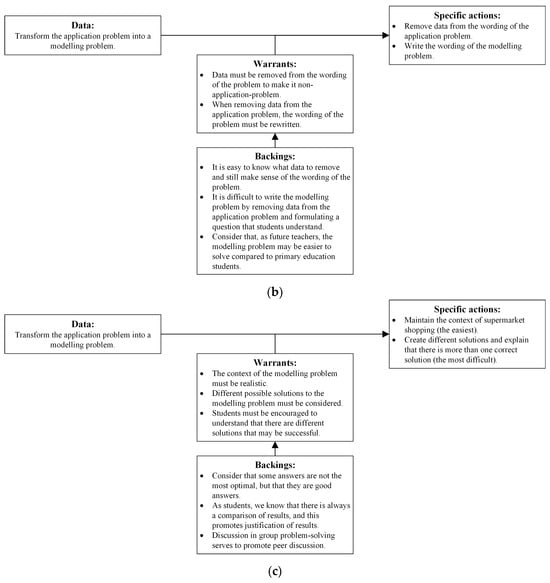

The answers to the questionnaire were complemented with those from the interview conducted, from which the practical arguments represented in Figure 5 were structured.

Figure 5.

Structuring and representation of the practical arguments developed by the study subjects in (a) Group 1; (b) Group 2; (c) Group 3. Source: Authors’ creation.

A practical argument worth highlighting is that developed by the study subjects in Group 1 (Figure 5a), which also shows the aspects considered for transforming an application problem into a modelling problem. First, these prospective teachers emphasised the importance of wording the problem, which should be brief but understandable, considering the students’ educational level. This led them to consider that as future teachers, a problem they propose may be easier for them to solve than for their future students, which would require significant effort for adaptation. Finally, they emphasised the importance of considering the characteristics of a modelling problem when formulating it.

The fourth question in the questionnaire and interview was: What prior knowledge (as undergraduate students) did you consider when designing the application and modelling problems? The answers to the questionnaire applied to the study subjects addressing this fourth question were as follows:

- Group 1: We took into account the usual solving process (data, operations, and the solution) because it was something we had previously worked on in our primary education.

- Group 2: We took into account our experience as primary school students and the educational internships of this course to develop problems that were not very difficult or easy to solve and, at the same time, understandable statements, using non-technical words and situations from everyday life or that they could understand since they are close to them (the students).

- Group 3: How children learn at these stages of learning. What resources to use and how mathematics is taught in elementary school. How to solve different problems in the classroom. How to assess the students’ learning process. A thorough understanding of the mathematics we are applying in the activity.

As observed in the answers to the fourth question of the questionnaire, those of Groups 1 and 2 mention the study subjects’ experience as primary education students; that of Group 2 also alludes to the linguistic and contextual aspects of problem posing, and that of Group 3 alludes to the cognitive aspects of mathematical teaching and learning processes. However, due to the declarative nature of this question—that is, not leading to action—it was not addressed during the interview conducted with the study subjects, and, consequently, the emergence of episodes of practical argumentation was not identified.

The fifth question in the questionnaire and interview was: What changes did you make to your initial learning situation to incorporate the application and modelling problems? The answers to the questionnaire applied to the study subjects addressing this fifth question were as follows:

- Group 1: We did not have to adapt our initial learning situation to be able to incorporate application and modelling problems;

- Group 2: The change we made to our learning situation was the destination (of the end-of-year trip). At first, we decided that the destination would be chosen by them (the students) in groups, but we found it difficult to create problems without a fixed destination and a budget. So, we decided to set these parameters, both the destination and the budget, and this way, it would be easier for us to create the problems;

- Group 3: To incorporate application and modelling problems, we made several adjustments to the learning situation. First, we adapted the original context to directly connect it to the students’ everyday lives. Then, we reformulated the statements of the problems to allow for multiple possible solutions, promoting decision making and argumentation. Finally, we included visual aids and realistic data (such as price lists) to enrich the activity and make it more realistic.

As observed in the answers to the fifth question of the questionnaire, those of Groups 2 and 3 were based on modifications justified primarily by compliance with the evaluation criteria for the written report with the oral presentation rather than by aspects voluntarily changed by the study subjects in their LS. Furthermore, the answers of these two groups focused on changes made to the statements of the problems rather than to the approach to the LS. However, because the adaptations made by the study subjects were already reflected in the answers to the second and third questions of the questionnaire applied and the interview conducted, and when this fifth question was asked again during the interview, no additional relevant information was obtained, the emergence of episodes of practical argumentation was identified that could not be represented with a complete structure, such as those presented in Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5. For this reason, the episodes identified in the answers to this fifth question were not considered for analysis in this study.

4.2. Description and Representation of the Solution Plans to the Modelling Problems

This section describes and represents the solution plans to the modelling problems proposed by the study subjects in their written reports. To this end, first, the statement of one of the two application problems designed by each work group is presented and its solution plan is briefly described; second, the statement of the modelling problem into which the work groups transformed the application problem is presented, and, third, the solution plan that the study subjects proposed for this modelling problem in their written reports is briefly described and then represented using the cycle in Figure 1.

4.2.1. Group 1’s Application and Modelling Problems

As described in Section 3.2.1, this work group designed an LS contextualised as a party for the school’s 50th anniversary, for which the students must prepare a cake with the help of the school’s cooks. The statement of one of the application problems designed by these study subjects was the following:

Now it is time to go to the market! To make the cake for 12 people, you have a budget of EUR 20. The ingredients are as follows: 300 g of dark chocolate—EUR 7.77, 180 g of butter—EUR 3.85, half a dozen eggs—EUR 1.99, 120 g of sugar—EUR 1.25, 90 g of flour—EUR 1.35, and 3 teaspoons of baking powder—EUR 2.25. Did you have any money left over? If so, how much money did you save?

To solve this application problem, the study subjects explained that students should add the prices of all the ingredients and subtract this total from the initial budget of EUR 20. Having solved this problem, the answer is that money was left over and that EUR 1.54 were saved.

Using the statement of the application problem presented above, the study subjects designed the following modelling problem:

Discuss in your groups how much you think each ingredient might cost and come up with an approximate budget for making a cake for 12 people. Then, we will discuss the group’s conclusions with the entire class and work together to create a final budget.

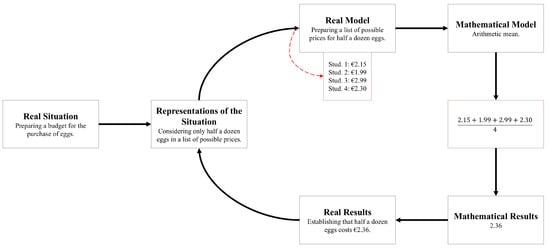

To solve this modelling problem, the study subjects explained that students would only have the list of ingredients to make a cake for six people. Then, students should estimate the costs of each ingredient, primarily based on their shopping experiences. Finally, students should double these estimates to come up with a budget for making a cake for 12 people. While the study subjects did not describe a possible complete solution plan to this modelling problem (due to the page limit of the written report), they did describe a possible partial solution for the cost of purchasing the eggs needed to make the cake. This possible partial solution plan is represented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Representation of the solution plan proposed for a modelling problem designed by Group 1. Source: Authors’ creation based on the written report of Group 1.

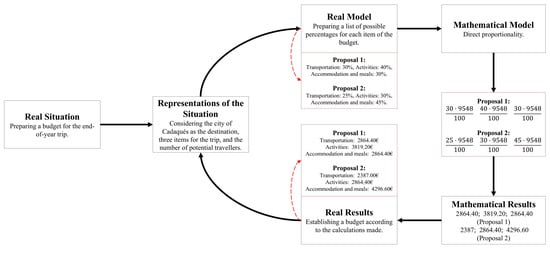

4.2.2. Group 2’s Application and Modelling Problems

As described in Section 3.2.2, this work group designed an LS contextualised as the planning and organisation of the end-of-year trip, for which the students must prepare a budget. The statement of one of the application problems designed by these study subjects was the following:

After a meeting, the school faculty has determined the final budget for the end-of-year trip. The total available for the entire sixth-grade class will be 9548 EUR. It has been decided to distribute the funds as follows: 33% of the budget for transportation, 45% for activities during the summer camp, and the remaining portion for lodging and subsistence allowances. What percentage of the budget will be allocated to accommodation and subsistence allowances? How much does each percentage of the budget represent?

To solve this application problem, the study subjects explained that students should add the two known percentages and subtract this total from 100%. Having solved this problem, the answer to the first question is that 22% of the budget was allocated to accommodation and subsistence allowances. Then, students should calculate how much of the total budget the, now, three known percentages corresponded to, which was possible using direct proportionality. Thus, the answer to the second question is that EUR 3159.84 was allocated to transportation, EUR 4296.60 to activities, and EUR 2100.56 to accommodation and subsistence allowances.

Using the statement of the application problem presented above, the study subjects designed the following modelling problem:

The school has raised 9548 EUR for the sixth-grade students’ end-of-year trip. It is a unique opportunity to share experiences with our classmates before closing this educational stage! But before we start packing, we need to decide how we will spend our money. There are several important expenses we cannot forget: transportation to get to the summer camp, activities (because we want to have fun and learn new things), and accommodation and meals (because a place to sleep and eat during our stay is necessary). But the budget is limited, so we must make smart decisions to make the most of the money. How would you divide the budget? Decide how much money you would allocate to each part and explain why.

To solve this modelling problem, the study subjects explained that students would consider the city of Cadaqués (Spain) as their trip destination. Having defined this destination, students should first decide what percentage of the budget they would allocate to each item, primarily based on their travel experiences and considering the number of potential travellers. Then, students should calculate how much of the total budget the three allocated percentages corresponded to, which was possible using direct proportionality. The study subjects described two possible solution plans to this modelling problem. These possible solution plans are represented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Representation of the solution plans proposed for a modelling problem designed by Group 2. Source: Authors’ creation based on the written report of Group 2.

4.2.3. Group 3’s Application and Modelling Problems

As described in Section 3.2.3, this work group designed an LS contextualised as the simulation of a market, for which the students must calculate purchase costs and estimate budgets. The statement of one of the application problems designed by these study subjects was the following:

At one of the market stores, the price of apples is 1.5 EUR per kilo (EUR/kilo). Axel wants to buy 3 kilos of apples, and his friend Nerea wants to buy 5 kilos. How much should each of them pay, and what is the total they spent together? What is the price of the second kilo of apples if it is 50% off at another store?