Abstract

Regular classes in outdoor education are gaining popularity worldwide, driven by their potential to enhance a wide range of educational outcomes. The aim of this scoping review is to establish the current state of knowledge about the effects of this form of teaching on academic achievement and its associated factors. Of the 2362 articles included in the corpus, 41 studies involving 10,453 students from preschool to college were analyzed to identify provenance, type of interventions, research design and outcomes. The analyses suggest that outdoor teaching appears to improve learning in sciences, reading, writing, social studies and mathematics. Outdoor teaching seems to support the development of various factors associated with academic achievement, including self-awareness, school climate, motivation and well-being. This leads us to conclude that, in the current state of knowledge, outdoor teaching is a promising pedagogical approach. However, further research is needed to identify and understand its long-term effects across a broader range of disciplines and for a broader range of competences.

1. Introduction

In the school setting, teachers sometimes relocate teaching activities linked to school curricula to outside places (in the schoolyard, in a park or in a forest, for example). This teaching method can be called outdoor teaching (Nadeau-Tremblay et al., 2023). Given its place in the school context, an important aim of outdoor teaching is for students to learn. Student learning that takes place in the context of outdoor teaching can be described as outdoor learning. Outdoor teaching seems to have become increasingly popular in recent years, and this trend is partly a result of the COVID-19 pandemic (see, for example, Ayotte-Beaudet et al., 2022). Indeed, in the context of the pandemic, many teachers who did not go outdoors with their students did so, often encouraged by their superiors, because the risks of transmitting the virus are lower in an outdoor environment. By going outdoors, some of them saw benefits for their pupils and continued to develop outdoor teaching practices in the post-pandemic period.

Although the growing interest in outdoor teaching is recent, the practice itself has been around for a long time, all over the world. For example, there are descriptions of outdoor teaching practices dating back to the 19th century in both Europe and America (e.g., the study by Wells et al., 2015, recounts the history of garden-based teaching) or New Zealand (Stothart, 2012). As for the idea that all or part of formal education should take place outdoors, its roots can be traced back to antiquity. While Plato and Aristotle emphasized the importance of physical education and intellectual development within a natural environment, it was during the Enlightenment that the notion of outdoor learning gained significant traction. Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1762), in Émile, advocated for a natural education where children learn through direct experiences with their surroundings. John Locke (1693/1989), in Some Thoughts Concerning Education, also emphasized the role of the environment in shaping moral and physical development. Later, during the 19th century, educators such as Friedrich Froebel, the founder of the kindergarten movement, and Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, who emphasized holistic education, reinforced the importance of interaction with nature as part of a child’s learning experience (Yıldırım & Akamca, 2017).

Much has been written about outdoor teaching today, using a variety of designations, which can make navigating the terminology complex. Some terms refer to practices that are sometimes teaching-focused, sometimes not. Moreover, the boundaries between these terms are not well defined. For the purposes of this article, we propose an ad hoc typology to relate these terms. This typology (Table 1) proposes three categories of outdoor teaching practices. Place-oriented outdoor teaching practices give significant importance on the places in which outdoor teaching takes place. We place practices such as forest school and prairie classes in this category, because these approaches emphasize the importance of being in specific natural environments that have been minimally transformed by humans. Acquisition-oriented outdoor teaching practices are primarily focused on academic learning. The outdoors is seen as one pedagogical tool among others, but a particularly relevant one. For example, udeskole is “characterised by compulsory educational activities outside of school on regular basis” (Bentsen et al., 2018, p. 90). Experience-oriented teaching practices emphasize the need to surpass oneself, as in the case of school expeditions. Obviously, whatever the category, the aims of learning and being outside remain. But the emphasis is different in all three categories and may refer to the way teachers engage in outdoor teaching.

Table 1.

Typology of outdoor teaching practices.

A number of studies have looked at the impact of outdoor education on students. Langelier et al. (2025) realized a scoping review focused on health that indicates that outdoor learning (a potential and desired outcome of outdoor education) have an impact on physical and motor development through an increase in the intensity and duration of physical activity (Barton et al., 2015; Bølling et al., 2021; Dettweiler et al., 2017; Finn et al., 2018; Fiskum & Jacobsen, 2012; Peacock et al., 2021; Romar et al., 2019; Trapasso et al., 2018), decrease sedentary behaviors (Dettweiler et al., 2017; Trapasso et al., 2018) and lead to an improvement in motor skills (Trapasso et al., 2018). Outdoor education also has a positive impact on socio-emotional development, including self-esteem (Barton et al., 2015; Yıldırım & Akamca, 2017), self-perception (White, 2012), well-being (Harvey et al., 2021), life satisfaction (McAnally et al., 2018; Largo-Wight et al., 2018) and emotions (Fiskum & Jacobsen, 2012; Harvey et al., 2021; Gustafsson et al., 2012; Trapasso et al., 2018). It has been linked to reduced stress (Dettweiler et al., 2017, 2022) and anxiety (Pirchio et al., 2021), increased autonomy (Dettweiler et al., 2022), and enhanced prosocial behaviors (Fiskum & Jacobsen, 2012; Gustafsson et al., 2012; McAnally et al., 2018; Pirchio et al., 2021). In addition, it may be associated with reduced disruptive behaviors in school contexts (Fiskum & Jacobsen, 2012; Largo-Wight et al., 2018). One study has also shown the positive effect of outdoor education on creative thinking (McAnally et al., 2018). The interventions considered in the Langelier et al. (2025) scoping review and in most of the syntheses published to date are not all conducted in a school context. However, the school setting has several specific characteristics that can influence the nature of the benefits of outdoor education: the intended learning outcomes are determined by curricula, the children involved are usually of the same age, the number of participants is constrained by external factors, and the workers are trained professionals in teaching, but not necessarily in outdoor education. It would therefore be worthwhile to focus on school-based interventions, carried out by teachers, to ensure that the outcomes are comparable to other forms of outdoor education.

Few studies have examined the impact of outdoor teaching specifically on learning. Becker et al. (2017) carried out a systematic review of the effects of regular classes in outdoor education on students’ learning, socialization and health. This systematic review led to the identification of six studies that looked specifically at the impact on academic learning. E. Mygind (2007) found no positive effect on academic learning. Santelmann et al. (2011) found student reports of gains in nature-related knowledge and communication skills. Moeed and Averill (2010) found gains in horticultural acquisition. Bowker and Tearle (2007) found gains in gardening knowledge. Sharpe (2014) showed potential gains in sciences, mathematics and English. Wistoft (2013) showed gains in desire to learn. Ernst and Stanek (2006) have identified the added value of outdoor teaching in terms of academic performance in reading and writing. Their research also showed that the same outdoor teaching made children feel more competent in science, problem solving and technology. Nevertheless, all the research reviewed by Becker et al. (2017) was in the form of case studies, mostly based on a non-experimental design, which begs the question of its generalizability.

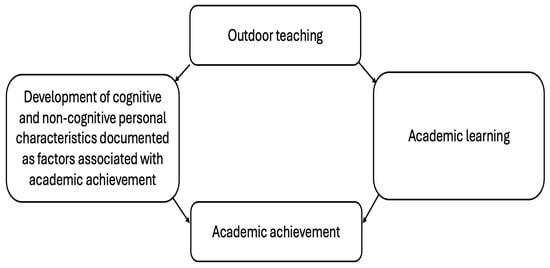

In this article, we examine the available data to assess the effects of outdoor teaching on students’ learning. Our approach is original in that most existing knowledge syntheses combine interventions by teachers in a school setting with those conducted by non-teachers or in non-school contexts (e.g., Dillon et al., 2016; Langelier et al., 2025; Mann et al., 2021). We specifically focus on available research findings on the effect of outdoor practices by teachers on students’ learning, using a mixed-method approach that includes a pre/quasi-experimental component, as well as a pre/quasi-experimental design to determine whether outdoor teaching influences learning outcome, while previous reviews bring together all methodological approaches. By doing so, we aim to restrict our analysis to outcomes that have been objectively measured. We specifically interrogate the effects of outdoor teaching on academic achievement and its associated factors. Academic achievement represents the extent to which pupils accomplished specific goals that were the focus of activities in an academic environment (Steinmayr et al., 2014). These objectives are measured using a wide variety of indicators relating both to academic results and to performance on tasks of a psychometric or edumetric nature (Mather & Abu-Hamour, 2013), both of which are attached to academic content (mathematics, sciences, reading, etc.). We also consider factors associated with academic achievement. By factors associated with academic achievement, we refer to prerequisites, moderators or mediators of academic achievement documented in the literature. These associated factors include, but are not limited to, cognitive skills (e.g., Rohde & Thompson, 2007); non-cognitive personal characteristics such as motivation, personality traits, planned behavior, school climate, self-beliefs/social-cognitive theory, self-concept, self-regulatory learning strategies, attitude, and vocational interests (Lee & Stankov, 2018); and well-being (Klapp et al., 2024). Figure 1 illustrates the relationships between the key concepts used in this review.

Figure 1.

Relationships between the concepts.

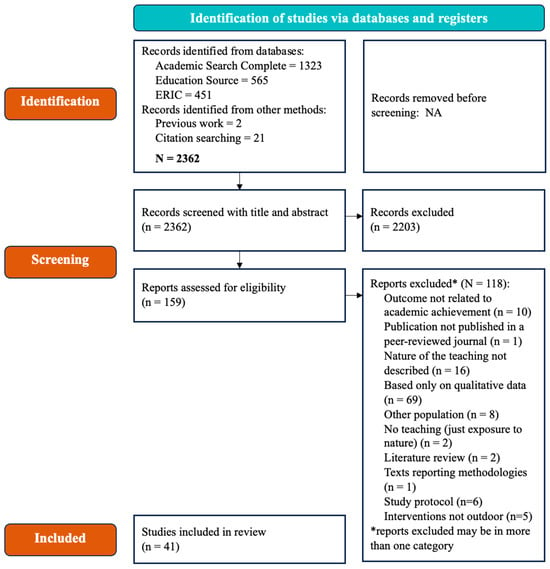

2. Materials and Methods

This research is a scoping review (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005) and is reported through the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline (Tricco et al., 2018). The five stages of Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) framework are used: (1) identifying the initial research questions, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data and (5) collating, summarizing and reporting the results. We did not previously register the protocol of this scoping review. Figure 2 reports its PRISMA diagram.

Figure 2.

Prisma diagram of the scoping review.

2.1. Identification of the Initial Research Question

As previously mentioned, this paper examines the available research findings on whether outdoor teaching can influence academic achievement directly or indirectly through its associated factors. Considering the framework used to define academic achievement, this amounts to asking the following questions: At which grade levels is knowledge available about the effects of outdoor teaching on academic achievement and its associated factor? What do we know about the effects of different forms of outdoor teaching on academic achievement and its associated factors? The indicators of academic achievement considered relate to the performance of children in curricular or psychometric assessments related to subjects taught within the school systems (geography, history, mathematics, reading, writing and sciences). The associated factors considered are those derived from Lee and Stankov (2018): motivation, personality traits, planned behavior, school climate, self-beliefs/social-cognitive theory, self-regulatory learning strategies, teacher behavior, value, and vocational interest—and, to be considered, other non-expected factors had to be linked with research results and identified as a prerequisite, mediator or moderator of academic achievement.

2.2. Identification of the Relevant Studies

Three educational databases were used to identify the corpus: Academic Search Complete, Education Source and ERIC. These databases are highly relevant for the field of education. Based on the research question, the following keywords and expressions referring to outdoor teaching interventions were used: “outdoor education”, “outdoor learning”, “outdoor teaching”, “education outside of the classroom”, “learning outside the classroom”, “out of classroom”, “forest school”, “udeskole”, “prairie science classes”, “outdoor science”, “garden education”, “camping education”, “adventure education”, “outdoor adventure”, “schools gardens”. To ensure that we had access to articles reporting the impact of interventions on academic achievement, we added the following restriction to our search with all the keywords: (1) AND “educational benefits”; (2) AND “educational outcomes” so as to capture both academic achievements themselves and their associated factors. To include as many studies as possible that would not use this terminology, while using a mixed or experimental approach to examine outcomes related to academic achievement, we added the condition (3) AND “experimental”. This query retrieved mixed, experimental, quasi-experimental or pre-experimental designs. The selection of papers began in Spring 2022, and the last search was conducted in Spring 2025. All search queries are reported in Appendix A.

2.3. Study Selection

Our approach brought back 2341 papers after removing duplicates. Titles and abstracts were screened by the first or second author to analyze whether they reach our eligibility criteria.

Inclusion criteria:

- -

- The paper is published in a peer-reviewed journal.

- -

- The paper is published in English.

- -

- The nature of the outdoor teaching is described.

- -

- The outcomes measured are related to academic achievement or its associated factors.

Exclusion criteria:

- -

- The paper is not related to the school context.

- -

- The paper assesses the effects of a passive exposure to nature.

- -

- The paper is a review or meta-analysis (to avoid reviewing the same results several times).

- -

- The paper reports only methodologies or protocols.

The decision for each paper was discussed. The bibliography of each text was consulted to identify new references (n = 21). Of the 2362 papers considered, this step led to the exclusion of 2203 references. The 159 that remained were then analyzed by the first or second author, keeping in mind the inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure the adequacy of our corpus. The result of this analysis was then co-validated by the first and second author and discussed for about ten articles. For half of them, the question was whether or not the interventions qualified as outdoor teaching. In the event of disagreement in this context, the coders jointly took up the description of the interventions in the article and the inclusion criteria, and carried out a criterion-by-criterion assessment until a consensus was reached. For the other half, the link between the outcomes examined and academic achievements and its associated factors raised questions. In these cases, to reach a consensus, the coders looked for references that measured a relationship between the outcome in question and academic achievement and its predictors. When a reference was found, the article was retained. If not, the article was excluded. This approach led to the inclusion of 41 papers in the review.

2.4. Chart of the Data

A detailed summary for each of the 41 papers included in the review was produced. This summary includes the full reference of the paper, a description of the interventions whose effects are evaluated, the characteristics of the participants and the effects of the intervention on academic achievement or its associated factors.

2.5. Organization and Report of the Results

The first author worked on the detailed summary, categorized the outcomes and drafted the initial version of the results sections, which were then submitted to all the coauthors for feedback.

3. Results

The 41 references listed in this scoping review were published between 2001 and 2024. They involve 10,453 students from preschool to college. The provenance, classification, interventions, participants, design and outcome of the 41 papers included in the review are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Provenance, outdoor teaching interventions, participants characteristics and outcomes related to academic achievements and its associated factors of the selected articles.

3.1. At Which Grade Levels Is Knowledge Available About the Effects of Outdoor Teaching on Academic Achievement and Its Associated Factors?

A first result concerns the distribution of school levels covered by the research on the effects of outdoor education on academic achievement and its associated factors: One study, involving 35 pupils, addresses early childhood education (Yıldırım & Akamca, 2017). Twelve studies, collectively involving 5453 pupils aged between 5 and 10 years, provide results about primary education worldwide (Ambusaidi et al., 2019; Ashjae et al., 2024; Avcı & Gümüş, 2020; Davis et al., 2023; Dirks & Orvis, 2005; Ellinger et al., 2022; Faber Taylor et al., 2022; Robinson & Zajicek, 2005; Smith & Motsenbocker, 2005; Tabaru Örnek & Yel, 2024; Ting & Siew, 2014; Wells et al., 2015). Thirteen studies, with a combined total of 661 pupils aged between 11 and 16, refer to secondary education (Achor & Amadu, 2015; Arıkan, 2023; Beightol et al., 2012; Fägerstam & Blom, 2013; Fägerstam & Samuelsson, 2014; Fan et al., 2024; Genc et al., 2017; Martin et al., 2009; McAnally et al., 2018; Pambudi, 2022; Sarac Yildirim & Dogru, 2023; Vančugovienė et al., 2024; White, 2012). One study involves 275 students over 16 years of age, referred to here as undergraduate students (Bailey & Kang, 2015). Nine studies involve 3149 pupils spread across both primary and secondary levels (Bølling et al., 2019; Dettweiler et al., 2015; Khan et al., 2020; Klemmer et al., 2005; Otte et al., 2019a, 2019b; Quibell et al., 2017; Stevenson et al., 2021; Waliczek et al., 2001), while four studies, involving a total of 462 students, span both secondary and higher education (Braun & Dierkes, 2017; McGowan, 2016; Sellmann & Bogner, 2013a, 2013b). Finally, one study involves 418 students from primary to higher education (Braun et al., 2018).

3.2. What Do We Know About the Effects of Different Forms of Outdoor Teaching on Academic Achievement and Its Associated Factors?

Regarding the categories identified at the beginning of this article (Table 1), 29 articles present intervention programs that are acquisition-oriented, 10 articles present place-oriented programs, and two present experience-oriented programs. For acquisition-oriented studies, the analysis points to an improvement in learning by outdoor teaching in sciences. Twenty-three articles involving 6383 students provide results of this order (Achor & Amadu, 2015; Arıkan, 2023; Ashjae et al., 2024; Bølling et al., 2019; Braun & Dierkes, 2017; Braun et al., 2018; Dettweiler et al., 2015; Dirks & Orvis, 2005; Faber Taylor et al., 2022; Fägerstam & Blom, 2013; Fan et al., 2024; Genc et al., 2017; Khan et al., 2020; Klemmer et al., 2005; Robinson & Zajicek, 2005; Sellmann & Bogner, 2013a, 2013b; Stevenson et al., 2021; Smith & Motsenbocker, 2005; Ting & Siew, 2014; Vančugovienė et al., 2024; Wells et al., 2015; Yıldırım & Akamca, 2017). However, one study showed positive effects for certain thematics but not for others, detailing conceptual progress in 62 students (Smith & Motsenbocker, 2005). Three articles focus on mathematical learning. Fägerstam and Samuelsson (2014) and Pambudi (2022), on the one hand, show better mathematical learning outdoors, for a total of 60 children. Otte et al. (2019a), on the other hand, found no benefits of outdoor teaching for mathematics, based on data from 619 children. One study focuses on reading. Otte et al. (2019b) show better reading learning with outdoor teaching in a study realized with 381 children. Finally, Avcı and Gümüş (2020) observed better academic results in social studies in an outdoor teaching context. Other acquisition-oriented articles looked at outcomes related to academic achievement-associated factors, such as self-concept (White, 2012; Robinson & Zajicek, 2005; McGowan, 2016) and school climate (Beightol et al., 2012), peer affiliations (Bølling et al., 2019). All these studies reported positive outcomes.

The nine place-oriented articles focus on outcomes related to factors of academic achievement and to academic achievement. These include the following:

- -

- Improvement in attitudes towards gardening and healthy alimentation, although no improvement was observed in science knowledge and skills among 135 children in the study of Ambusaidi et al. (2019);

- -

- Improvement in reading in fourth grade, although no improvement was observed in mathematic or reading in fifth grade among 1400 children in Davis et al. (2023);

- -

- Positive effect observed on motivation among 25 children in Ellinger et al. (2022);

- -

- Improvement in grades and vocational identity observed in 295 students in Bailey and Kang (2015);

- -

- Improvement in attitudes towards the environment observed in 45 students in Martin et al. (2009);

- -

- Enhancement of reading, writing and mathematics observed in 223 students for Quibell et al. (2017);

- -

- Improvement in interest and attitude among sciences observed in 37 children in Sarac Yildirim and Dogru (2023);

- -

- Improvement in science observed in 32 children in Tabaru Örnek and Yel (2024);

- -

- Improvement in interpersonal relationships and a decrease in negative attitudes toward school observed for 598 chidren in Waliczek et al. (2001).

The two experience-oriented articles focus on the effects of outdoor teaching on factors of academic achievement. These include improvements in the well-being of 106 students (McAnally et al., 2018) and self-concept (McGowan, 2016).

4. Discussion

This scoping review aims at establishing the current state of knowledge about the effects of outdoor teaching on academic achievement and its associated factors. To answer this question, 41 articles reporting studies carried out among 10,453 children were analyzed. These analyses show that the most robust knowledge regarding the impact of outdoor teaching lies at the primary school level, closely followed by the secondary school level. The presence of only one study on preschool suggests that further studies at this level are necessary, especially since outdoor teaching seems particularly interesting for implementing developmentally appropriate interventions (Kiviranta et al., 2024).

Most studies are acquisition-oriented. This is unsurprising, given that, in most countries, the mission of schools is expressed primarily in terms of instruction and acquisition of knowledge. In studies from this category, disciplinary acquisitions concern mainly the sciences. If this leads to the conclusion that outdoor teaching is an effective way to teach sciences, it also begs the question of its pertinence in other disciplines. Given that some acquisition-oriented, place-oriented and experience-oriented interventions point to benefits in reading, writing, social studies and mathematics (with contradictory results for this discipline), the whole being corroborated by a number of qualitative studies not included in this article (e.g., Down et al., 2024), we might think that going outside with students with the primary intention of teaching them these subjects by taking advantage of the outdoor environment would have benefits, but this remains to be reinforced by further research. In this respect, the scientific community would benefit from adopting common criteria for describing activities carried out in nature, which would facilitate the aggregation of study results.

Interestingly, a few studies focus on the development of cross-curricular skills, which are often targeted in school curricula as factors of academic achievement (e.g., Niemelä, 2021), and for which teachers have fewer resources. In the first instance, three studies (Beightol et al., 2012; Fägerstam & Blom, 2013; Waliczek et al., 2001) highlight effects on school climate, the importance of which Beightol et al. (2012), in particular, have shown for academic achievements. Two studies (Robinson & Zajicek, 2005; White, 2012) highlight effects on self-knowledge and self-control; Bailey and Kang (2015) and Beightol et al. (2012) highlight effects on vocational identity; Those are three factors predictive of academic achievement according to Lee and Stankov (2018). Yıldırım and Akamca (2017) show effects on cognitive skills of preschool children which, of course, are factors of academic achievement. In this study, cognitive skills are assessed through tasks such as telling where an object is, placing an object in accordance with instructions, going to the place instructed and using maps and sketches. Dettweiler et al. (2015) show the effects of outdoor teaching on motivation, a factor of academic achievement, again according to Lee and Stankov (2018). McAnally et al. (2018) show positive effects on well-being, a factor of academic achievement according to Klapp et al. (2024). At the same time, several factors of academic achievement have not been investigated in the studies reviewed, and deserve to be better known, foremost among which is the quality of teachers’ practices (Hattie, 2009). Of course, we cannot exclude that such studies may exist and not have been listed in the databases we have mobilized, or may not have been reached with the queries we used.

The presence of several articles in which interventions are not acquisition-oriented is interesting. This shows that, in a school context, it is possible to go outdoors with students primarily to enjoy nature or outdoor environments, or primarily to live an experience. These alternatives are interesting for thinking about ways to support teachers who express the wish to go outdoors without really knowing how or why, and offer support by making it explicit that it is possible to go just for fun or simply to get some fresh air with a view to sustainable health initially, and that, little by little, we can think of more didactic interventions, which were identified in the study by Langelier et al. (2025) who mentioned that as soon as children are outside in a natural environment, they can benefit from the positive effect of nature exposure. This scoping review reveals three main areas of uncertainty: (1) In the reviewed studies, effects were mainly measured immediately after short-term interventions, or during the school year for long-term interventions. This raises the question of whether these immediate benefits are sustained over time. (2) The studies focus on a limited number of variables and lack of uniformity or standardization. It would be interesting to develop studies that include more variables to better understand how outdoor teaching influences students. Indeed, some of these variables might be confounded or act as mediators between outdoor teaching and academic achievement. (3) The methodologies of the studies vary considerably, and it would be interesting to examine which results are obtained with the most rigorous methodologies. In our view, the most rigorous methodologies in this context are mixed methodologies, which combine a detailed phenomenological description of the interventions, the extraction of some of their characteristics from a quantitative point of view, the measurement of benefits for students using standardized measurement tools, and the collection of qualitative data on how students experience the activities.

It seems clear to us that, in view of (1) the growing popularity of this type of teaching, which is certainly leading to an evolution in practices (2), the areas of uncertainty underlined above, further research into the value of outdoor teaching according to the standards mentioned in the previous paragraph is needed.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review concludes that robust results indicate that outdoor teaching can support academic achievement, particularly in the field of sciences (mainly ecology, biology and scientific reasoning). These more-than-favorable results encourage further investigation into the impact of outdoor teaching on reading, writing, mathematics and social studies, to confirm the first positive results on these fields.

There is also encouraging evidence of effects on factors associated with academic achievement, such as self-awareness, school climate, motivation and well-being. But further research is needed (1) to examine the potential effects of outdoor teaching on other factors associated with academic achievement; and (2) especially, to better understand, in the context of outdoor teaching, the relationships between academic achievements, their associated factors and the actual practices of teachers.

So, given the current state of knowledge, we think it is appropriate for policy-makers and school stakeholders to consider that research offers very encouraging data to the effect that outdoor teaching can support students’ academic achievement, but that further research is needed to identify the various effects and factors. A number of recently registered study protocols will help progress in this direction (e.g., Barenie et al., 2023; Bølling et al., 2023; Stage et al., 2025).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.P. (Loïc Pulido); methodology, L.P. (Loïc Pulido) and A.P.; formal analysis, L.P. (Loïc Pulido) and A.P.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P. and L.P. (Loïc Pulido); writing—review and editing, L.P. (Loïc Pulido), A.P., C.B.-L., J.C., C.G.-C., C.L., L.P. (Linda Paquette), S.N.-T. and S.S.; supervision, L.P. (Loïc Pulido); project administration, L.P. (Loïc Pulido); funding acquisition, L.P. (Loïc Pulido). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by SSHRC grant numbers 892-2023-2041 and 435-2024-1332 and with SSHRC Université du Québec à Chicoutimi institutional grant. The APC was funded by the Université du Québec à Chicoutimi (bonus for academic program management paid in research funds).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Université du Québec à Chicoutimi’s Centre Intersectoriel en Santé Durable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

List of the queries:

- -

- outdoor education AND education outcomes; outdoor education AND educational benefits; outdoor education AND experimental;

- -

- outdoor learning AND education outcomes; outdoor learning AND educational benefits; outdoor learning AND experimental;

- -

- outdoor teaching AND education outcomes; outdoor teaching AND education benefits; outdoor teaching AND experimental

- -

- education outside of the classroom AND education outcomes; education outside of the classroom AND education benefits; education outside of the classroom AND experimental

- -

- learning outside the classroom AND education outcomes; learning outside the classroom AND education benefits; learning outside the classroom AND experimental

- -

- out of classroom AND education outcomes; out of classroom AND education benefits out of classroom AND experimental

- -

- forest school AND education outcomes; forest school AND education benefits; forest school AND experimental

- -

- udeskole AND education outcomes; udeskole AND education benefits; udeskole AND experimental

- -

- prairie science classes AND education outcomes; prairie science classes AND education benefits; prairie science classes AND experimental

- -

- outdoor science AND education outcomes; outdoor science AND education benefits; outdoor science AND experimental

- -

- garden education AND education outcomes; garden education AND education benefits; garden education AND experimental

- -

- camping education AND education outcomes; camping education AND education benefits; camping education AND experimental

- -

- adventure education AND education outcomes; adventure education AND education benefits; adventure education AND experimental

- -

- outdoor adventure AND education outcomes; outdoor adventure AND education benefits; outdoor adventure AND experimental

- -

- school garden AND education outcomes; school garden AND education benefits; school garden AND experimental

References

- Achor, E. E., & Amadu, S. (2015). An examination of the extent to which school outdoor activities could enhance senior secondary two students’ achievement in ecology. Journal of Education and e-Learning Research, 2(3), 35. [Google Scholar]

- Ambusaidi, A., Alyahyai, R., Taylor, S., & Taylor, N. (2019). School gardening in early childhood education in Oman: A pilot project with grade 2 students. Science Education International, 30(1), 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arıkan, K. (2023). A comparison of indoor and outdoor biology education: What is the effect on student knowledge, attitudes, and retention? Journal of Biological Education, 57(4), 727–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashjae, S., Fattahi, K., & Derakhshanian, F. (2024). Investigating the links between outdoor class and learning in primary school students (case study of a male-school in Shiraz). Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 24(2), 232–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avcı, G., & Gümüş, N. (2020). The effect of outdoor education on the achievement and recall levels of primary school students in social studies course. Review of International Geographical Education Online, 10(Special Issue), 171–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayotte-Beaudet, J. P., Chastenay, P., Beaudry, M. C., L’Heureux, K., Giamellaro, M., Smith, J., Desjarlais, E., & Paquette, A. (2021). Exploring the impacts of contextualised outdoor science education on learning: The case of primary school students learning about ecosystem relationships. Journal of Biological Education, 57(2), 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayotte-Beaudet, J. P., Vinuesa, V., Turcotte, S., & Berrigan, F. (2022). Pratiques enseignantes en plein air en contexte scolaire au Québec: Au-delà de la pandémie de COVID-19. Université de Sherbrooke. Available online: https://www.usherbrooke.ca/crepa/fileadmin/sites/crepa/Rapports/Pratiques_E__PA_Rapport_final.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Bailey, A. W., & Kang, H.-K. (2015). Modeling the impact of wilderness orientation programs on first-year academic success and life purpose. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 15(3), 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barenie, M. J., Howie, E. K., Weber, K. A., & Thomsen, M. R. (2023). Evaluation of the little rock green schoolyard initiative: A quasi-experimental study protocol. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton, J., Sandercock, G., Pretty, J., & Wood, C. (2015). The effect of playground- and nature-based playtime interventions on physical activity and self-esteem in UK school children. International Journal of Environmental Health Research, 25(2), 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, C., Lauterbach, G., Spengler, S., Dettweiler, U., & Mess, F. (2017). Effects of regular classes in outdoor education settings: A systematic review on students’ learning, social and health dimensions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(5), 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beightol, J., Jevertson, J., Carter, S., Gray, S., & Gass, M. (2012). Adventure education and resilience enhancement. Journal of Experiential Education, 35(2), 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentsen, P., Stevenson, M. P., Mygind, E., & Barfod, K. S. (2018). Udeskole: Education outside the classroom in a Danish context. In M. T. Huang, & Y. C. Jade Ho (Eds.), The budding and blooming of outdoor education in diverse global contexts (pp. 81–114). National Academy for Educational Research. Available online: https://www.ucviden.dk/ws/portalfiles/portal/107142984/Denmark.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Bowker, R., & Tearle, P. (2007). Gardening as a learning environment: A study of children’s perceptions and understanding of school gardens as part of an international project. Learning Environments Research, 10, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bølling, M., Elsborg, P., Stage, A., Stahlhut, M., Mygind, L., Melby, P. S., Amholt, T. T., Fernando, N., Ventura, A., Mikkelsen, S., Müllertz, A. L. O., Otte, C. R., Christian Brønd, J., Demant Klinker, C., Aadahl, M., Nielsen, G., & Bentsen, P. (2024, March 4–8). Exploring the interplay of three Danish research initiatives on education outside the classroom: Findings and future directions. 10th International Outdoor Education Research Conference (IOERC), Tokyo, Japan. Available online: https://www.ucviden.dk/en/publications/exploring-the-interplay-of-three-danish-research-initiatives-on-e (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Bølling, M., Mygind, E., Mygind, L., Bentsen, P., & Elsborg, P. (2021). The association between education outside the classroom and physical activity: Differences attributable to the type of space? Children, 8(6), 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bølling, M., Mygind, L., Elsborg, P., Melby, P. S., Barfod, K. S., Brønd, J. C., Klinker, C. D., Nielsen, G., & Bentsen, P. (2023). Efficacy and mechanisms of an education outside the classroom intervention on pupils’ health and education: The MOVEOUT study protocol. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bølling, M., Pfister, G. U., Mygind, E., & Nielsen, G. (2019). Education outside the classroom and pupils’ social relations? A one-year quasi-experiment. International Journal of Educational Research, 94, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, T., Cottrell, R., & Dierkes, P. (2018). Fostering changes in attitude, knowledge and behavior: Demographic variation in environmental education effects. Environmental Education Research, 24(6), 899–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, T., & Dierkes, P. (2017). Evaluating three dimensions of environmental knowledge and their impact on behaviour. Research in Science Education, 49(5), 1347–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J. N., Nikah, K., Landry, M. J., Vandyousefi, S., Ghaddar, R., Jeans, M., Cooper, M. H., Martin, B., Waugh, L., Sharma, S. V., & van den Berg, A. E. (2023). Effects of a school-based garden program on academic performance: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 123(4), 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettweiler, U., Becker, C., Auestad, B. H., Simon, P., & Kirsch, P. (2017). Stress in school. Some empirical hints on the circadian cortisol rhythm of children in outdoor and indoor classes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(5), 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettweiler, U., Gerchen, M., Mall, C., Simon, P., & Kirsch, P. (2022). Choice matters: Pupils’ stress regulation, brain development and brain function in an outdoor education project. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 93, 152–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dettweiler, U., Ünlü, A., Lauterbach, G., Becker, C., & Gschrey, B. (2015). Investigating the motivational behavior of pupils during outdoor science teaching within self-determination theory. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, J., Rickinson, M., & Teamey, K. (2016). The value of outdoor learning: Evidence from research in the UK and elsewhere. In Towards a convergence between science and environmental education (pp. 193–200). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dirks, A. E., & Orvis, K. (2005). An evaluation of the junior master gardener program in third grade classrooms. HortTechnology, 15(3), 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Down, M., Picknoll, D., Hoyne, G., Piggott, B., & Bulsara, C. (2024). “When the real stuff happens”: A qualitative descriptive study of the psychosocial outcomes of outdoor adventure education for adolescents. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 28, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellinger, J., Mess, F., Blaschke, S., & Mall, C. (2022). Health-related quality of life, motivational regulation and basic psychological need satisfaction in education outside the classroom: An explorative longitudinal pilot study. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernst, J., & Stanek, D. (2006). The prairie science class: A model for re-visioning environmental education within the national wildlife refuge system. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 11(4), 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber Taylor, A., Butts-Wilmsmeyer, C., & Jordan, C. (2022). Nature-based instruction for science learning–a good fit for all: A controlled comparison of classroom versus nature. Environmental Education Research, 28(10), 1527–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M. R., Tran, N. H., & Huang, C. F. (2024). Effects of outdoor education on elementary school students’ perception of scientific literacy and learning motivation. European Journal of Educational Research, 13(3), 1353–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fägerstam, E., & Blom, J. (2013). Learning biology and mathematics outdoors: Effects and attitudes in a Swedish high school context. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 13(1), 56–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fägerstam, E., & Samuelsson, J. (2014). Learning arithmetic outdoors in junior high school–influence on performance and self-regulating skills. Education 3-13, 42(4), 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, K. E., Yan, Z., & McInnis, K. J. (2018). Promoting physical activity and science learning in an outdoor education program. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 89(1), 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiskum, T. A., & Jacobsen, K. (2012). Individual differences and possible effects from outdoor education: Long time and short time benefits. World Journal of Education, 2(4), 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garden, A., & Downes, G. (2023). A systematic review of forest schools literature in England. Education 3-13, 51(2), 320–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genc, M., Genc, T., & Rasgele, P. G. (2017). Effects of nature-based environmental education on the attitudes of 7th grade students towards the environment and living organisms and affective tendency. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 27(4), 326–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, P. E., Szczepanski, A., Nelson, N., & Gustafsson, P. A. (2012). Effects of an outdoor education intervention on the mental health of schoolchildren. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 12(1), 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. J., Montgomery, L. N., & White, R. (2021). Just how much time outdoors in nature is enough. School Science Review, 102(381), 27–31. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1306101 (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses related to achievement. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M., McGeown, S., & Bell, S. (2020). Can an outdoor learning environment improve children’s academic attainment? A quasi-experimental mixed methods study in Bangladesh. Environment and Behavior, 52(10), 1079–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiviranta, L., Lindfors, E., Rönkkö, M. L., & Luukka, E. (2024). Outdoor learning in early childhood education: Exploring benefits and challenges. Educational Research, 66(1), 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapp, T., Klapp, A., & Gustafsson, J. E. (2024). Relations between students’ well-being and academic achievement: Evidence from Swedish compulsory school. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 39(1), 275–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemmer, C. D., Waliczek, T. M., & Zajicek, J. M. (2005). Growing minds: The effect of a school gardening program on the science achievement of elementary students. HortTechnology, 15(3), 448–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langelier, M. È., Fortin, J., Gauthier-Boudreau, J., Larouche, A., Mercure, C., Bergeron-Leclerc, C., Simard, S., Cherblanc, J., Brault, M.-C., Laprise, C., & Pulido, L. (2025). The impact of nature-based learning on student health: A scoping review. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Largo-Wight, E., Guardino, C., Wludyka, P. S., Hall, K. W., Wight, J. T., & Merten, J. W. (2018). Nature contact at school: The impact of an outdoor classroom on children’s well-being. International Journal of Environmental Health Research, 28(6), 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., & Stankov, L. (2018). Non-cognitive influences on academic achievement: Evidence from PISA and TIMSS. In M. S. Khine, & S. Areepattamannil (Eds.), Non-cognitive skills and factors in educational attainment (pp. 151–169). Sense Publishers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, J. (1693/1989). Some thoughts concerning education. Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1693). [Google Scholar]

- Mann, J., Gray, T., Truong, S., Sahlberg, P., Bentsen, P., Passy, R., Ho, S., Ward, K., & Cowper, R. (2021). A systematic review protocol to identify the key benefits and efficacy of nature-based learning in outdoor educational settings. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B., Bright, A., Cafaro, P., Mittelstaedt, R., & Bruyere, B. (2009). Assessing the development of environmental virtue in 7th and 8th grade students in an expeditionary learning outward bound school. Journal of Experiential Education, 31(3), 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mather, N., & Abu-Hamour, B. (2013). Individual assessment of academic achievement. In K. F. Geisinger, B. A. Bracken, J. F. Carlson, J.-I. C. Hansen, N. R. Kuncel, S. P. Reise, & M. C. Rodriguez (Eds.), APA handbook of testing and assessment in psychology, Vol. 3. Testing and assessment in school psychology and education (pp. 101–128). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAnally, H. M., Robertson, L. A., & Hancox, R. J. (2018). Effects of an outdoor education programme on creative thinking and well-being in adolescent boys. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 53(2), 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, A. L. (2016). Impact of one-semester outdoor education programs on adolescent perceptions of self-authorship. Journal of Experiential Education, 39(4), 386–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeed, A., & Averill, R. (2010). Education for the environment: Learning to care for the environment: A longitudinal case study. International Journal of Learning, 17(5), 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mygind, E. (2007). A comparison between children’s physical activity levels at school and learning in an outdoor environment. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 7(2), 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mygind, L., Kjeldsted, E., Hartmeyer, R., Mygind, E., Bølling, M., & Bentsen, P. (2019). Mental, physical and social health benefits of immersive nature-experience for children and adolescents: A systematic review and quality assessment of the evidence. Health & Place, 58, 102–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeau-Tremblay, S., Boily, É., Brault, M. C., Chevrette, T., Jacob, E., Langelier, M. È., Laprise, C., Mercure, C., & Pulido, L. (2023). Supporting the emergence of outdoor teaching practices in primary school settings: A literature review. Education 3–13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemelä, M. A. (2021). Crossing curricular boundaries for powerful knowledge. The Curriculum Journal, 32(2), 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otte, C. R., Bølling, M., Elsborg, P., Nielsen, G., & Bentsen, P. (2019a). Teaching maths outside the classroom: Does it make a difference? Educational Research, 61(1), 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otte, C. R., Bølling, M., Stevenson, M. P., Ejbye-Ernst, N., Nielsen, G., & Bentsen, P. (2019b). Education outside the classroom increases children’s reading performance: Results from a one-year quasi-experimental study. International Journal of Educational Research, 94, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pambudi, D. S. (2022). The effect of outdoor learning method on elementary students’ motivation and achievement in geometry. International Journal of Instruction, 15(1), 747–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, J., Bowling, A., Finn, K., & McInnis, K. (2021). Use of outdoor education to increase physical activity and science learning among low-income children from urban schools. American Journal of Health Education, 52(2), 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirchio, S., Passiatore, Y., Panno, A., Cipparone, M., & Carrus, G. (2021). The effects of contact with nature during outdoor environmental education on students’ wellbeing, connectedness to nature and pro-sociality. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 648458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quibell, T., Charlton, J., & Law, J. (2017). Wilderness Schooling: A controlled trial of the impact of an outdoor education programme on attainment outcomes in primary school pupils. British Educational Research Journal, 43(3), 572–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remmen, K. B., & Iversen, E. (2023). A scoping review of research on school-based outdoor education in the Nordic countries. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 23(4), 433–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C. W., & Zajicek, J. M. (2005). Growing minds: The effects of a one-year school garden program on six constructs of life skills of elementary school children. HortTechnology, 15(3), 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde, T. E., & Thompson, L. A. (2007). Predicting academic achievement with cognitive ability. Intelligence, 35(1), 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romar, J.-E., Enqvist, I., Kulmala, J., Kallio, J., & Tammelin, T. (2019). Physical activity and sedentary behaviour during outdoor learning and traditional indoor school days among Finnish primary school students. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 19(1), 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, J.-J. (1762). Émile, ou De l’éducation. In Œuvres complètes, t. III. Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, Gallimard. [Google Scholar]

- Santelmann, M., Gosnell, H., & Meyers, S. M. (2011). Connecting children to the land: Place-based education in the muddy creek watershed, Oregon. Journal of Geography, 110(3), 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarac Yildirim, E., & Dogru, M. (2023). The effects of out-of-class learning on students’ interest in science and scientific attitudes: The case of school garden. Educational Policy Analysis and Strategic Research, 18(1), 251–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellmann, D., & Bogner, F. X. (2013a). Climate change education: Quantitatively assessing the impact of a botanical garden as an informal learning environment. Environmental Education Research, 19(4), 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellmann, D., & Bogner, F. X. (2013b). Effects of a 1-day environmental education intervention on environmental attitudes and connectedness with nature. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 28, 1077–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, D. (2014). Independent thinkers and learners: A critical evaluation of the ‘Growing Together Schools Programme’. Pastoral Care in Education, 32(3), 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L. L., & Motsenbocker, C. E. (2005). Impact of hands-on science through school gardening in Louisiana public elementary schools. HortTechnology, 15(3), 439–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stage, A., Vermund, M. C., Bølling, M., Otte, C. R., Oest Müllertz, A. L., Bentsen, P., Nielsen, G., & Elsborg, P. (2025). The impact of a school garden program on children’s food literacy, climate change literacy, school motivation, and physical activity: A study protocol. PLoS ONE, 20(4), e0320574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinmayr, R., Meiǹer, A., Weideinger, A. F., & Wirthwein, L. (2014). Academic achievement (pp. 1–16). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, K. T., Szczytko, R. E., Carrier, S. J., & Peterson, M. N. (2021). How outdoor science education can help girls stay engaged with science. International Journal of Science Education, 43(7), 1090–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stothart, B. (2012). A chronology of outdoor education in New Zealand 1840 to 2011. New Zealand Physical Educator, 45(1), 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Tabaru Örnek, G., & Yel, S. (2024). A place-based practice in primary school: Effects on environmental literacy. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, K. L., & Siew, N. M. (2014). Effects of outdoor school ground lessons on students’ science process skills and scientific curiosity. Journal of Education and Learning, 3(4), 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapasso, E., Knowles, Z., Boddy, L., Newson, L., Sayers, J., & Austin, C. (2018). Exploring gender differences within forest schools as a physical activity intervention. Children, 5(10), 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vančugovienė, V., Lehtinen, E., & Södervik, I. (2024). The impact of inquiry-based learning in a botanical garden on conceptual change in biology. International Journal of Science Education, 47(7), 915–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waliczek, T. M., Bradley, J., & Zajicek, J. M. (2001). The effect of school gardens on children’s interpersonal relationships and attitudes toward school. HortTechnology, 11(3), 466–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, N. M., Myers, B. M., Todd, L. E., Barale, K., Gaolach, B., Ferenz, G., Aitken, M., Henderson, C. R., Tse, C., & Pattison, K. O. (2015). The effects of school gardens on children’s science knowledge: A randomized controlled trial of low-income elementary schools. International Journal of Science Education, 37(17), 2858–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R. (2012). A sociocultural investigation of the efficacy of outdoor education to improve learner engagement. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 17(1), 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wistoft, K. (2013). The desire to learn as a kind of love: Gardening, cooking, and passion in outdoor education. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 13(2), 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, G., & Akamca, G. Ö. (2017). The effect of outdoor learning activities on the development of preschool children. South African Journal of Education, 37(2), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).