Abstract

Reading and writing in the 21st century have evolved from traditional text-based formats to multimodal literacy, integrating linguistic, visual, auditory, and spatial modes to enhance communication and comprehension. While multimodal reading has been widely studied, multimodal writing remains underexplored, despite its growing importance in K–12 education across disciplines. Multimodal composing demands advanced self-regulation as students navigate multiple digital tools and platforms. Self-regulated learning strategies, particularly the self-regulated strategy development model, offer a promising approach to support students in planning, monitoring, and revising multimodal compositions. However, a comprehensive framework linking self-regulation and multimodal composition is lacking. This article addresses this gap by synthesizing findings from two studies—one in preservice teacher education and another in a first-grade classroom—along with existing research to propose a self-regulated multimodal composing framework. This framework aims to guide educators in fostering students’ autonomy and competence in multimodal composing. By integrating self-regulation strategies with multimodal composition processes, the SRMC framework provides actionable insights for instructional practices, helping teachers support diverse learners in today’s digitally mediated classrooms. The article discusses implications for pedagogy and future research, advocating for greater emphasis on self-regulated multimodal composing in literacy education.

1. Introduction

Reading and writing are essential components of life today. At an early age, children are expected to read and write in multiple formats for various purposes, utilizing many intersecting skills. Through the increased use of technology in everyday and classroom settings, the rise in digital and audiobooks, and the continued impact of the global pandemic and the prevalence of generative artificial intelligence, the modes of reading and writing have shifted (Brueck & Lenhart, 2015; Hutchison et al., 2025). Literacy in the 21st century has transitioned from solely linguistic-based, monomodal format to a multimodal concept, which combines various meaning-making modes to accommodate linguistic and cultural diversity worldwide (The New London Group, 1996).

In recent years, multimodal literacy, particularly multimodal reading and composing, has become widely practiced in various educational settings, including K–12 and post-secondary education (Si et al., 2022). Multimodal literacy encompasses several major modes, including linguistic, visual, auditory, spatial, and gestural, to facilitate communication and comprehension (Kress, 2000). Accordingly, multimodal literacy integrates multiple meaning-making modes into a single composition and understanding the meanings as a whole, rather than in separate formats. The development of technologies enables multimodal literacy development primarily relying on digital modes, such as audio, video, static and animated visuals, and spatial visuals (Harrison & McTavish, 2018). To develop multimodal literacy, learners need to practice their abilities to comprehend information and create meanings digitally using multiple modes.

Traditionally, writing focuses on linguistics articulation, such as words written by hand or typing on a screen-based platform; however, composing can incorporate more than linguistic mode in one composition, which is largely enabled by digital multimodal tools. Multimodal composing become increasingly Important in K–12 education as multimodal tools and representations can effectively support students’ learning and practices by integrating literacy into various subjects, such as science, mathematics, and social studies. For example, a study found that fourth and fifth-grade science teachers guide students to integrate visual representations and drawings into journal and report writings on scientific content to improve science learning efficiency (Si et al., 2024). In another study, elementary students used multimodal tools on iPads to generate compositions that combined words with pictures, sounds, and audio in relation to social studies content (Dalton, 2014). Studies also explored the idea that elementary students use digital tools and platforms to gain knowledge in mathematics (e.g., Freeman et al., 2016).

Multimodal composition requires heightened self-regulation, as students must coordinate content creation across tools and platforms (Cho & Lim, 2017; Smith, 2020). Self-regulated learning (SRL) refers to a process in which learners actively manage their own learning by employing various strategies, such as metacognition, motivation, and self-monitoring, to enhance learning effectiveness and self-efficacy. Developed from this perspective, Harris and Graham (1996) proposed an instructional approach, self-regulated strategy development (SRSD), that focuses on improving students’ writing skills through explicit strategies and self-regulation skills. Harris et al. (2009) noted that SRSD can be adapted to support multimodal composing when strategy instruction is aligned with genre-specific and multimodal elements (e.g., planning for audience engagement through images, using transitions between scenes in digital stories).

From prior research and current practices, it is clear that multimodal composing are relevant and critical skills for students today. Yet, research and practice still favor multimodal reading. One potential reason for this under-exploration of multimodal composing is that clear frameworks to define and discuss this phenomenon do not exist. Limited studies have been conducted to investigate scaffolded multimodal composing processes and how learners can benefit from a heuristic framework of self-regulated multimodal composing. To fill this gap, the present article examines two studies, grounded in preservice teacher education and first-grade classrooms, along with prior research and theory, to create a Self-Regulated Multimodal Composing (SRMC) Framework. This framework integrates self-regulation strategies into the multimodal composing process to cultivate autonomous learners. This necessary conceptual framework, rooted in empirical research, helps explain the depth of multimodal composing and the ways teachers can better support students in their classrooms. The present study aims to propose a self-regulated multimodal composing framework and explore its implementations for various learning needs and implications for instructional practices. The present study is guided by the following research questions:

- How can a self-regulated multimodal composing framework be developed to facilitate multimodal composition for all learners?

- How can the framework be implemented in teacher preparation to support multimodal composing?

- How can the framework be adapted to support young children in multimodal composing?

2. Theoretical Perspectives and Literature Review

2.1. Self-Regulated Learning

Zimmerman’s (2000) cyclical model of SRL offers a useful lens through which to examine the iterative nature of multimodal composing. The model outlines three interrelated phases: (1) forethought, (2) performance, and (3) self-reflection. In multimodal contexts, this model explains how students navigate the demands of planning across various visual and textual features, implementing and adjusting strategies mid-composition, and evaluating whether their finished product meets their own and assessment goals (Zimmerman & Schunk, 2011).

Recent studies suggest that when students are taught to approach multimodal tasks through SRL-informed scaffolds, such as digital planning templates or reflective prompts, their ability to make intentional multimodal choices improves (McVee et al., 2018; Pasternak et al., 2022). Thus, SRL not only frames multimodal composing as a cognitive and metacognitive endeavor but also highlights pedagogical opportunities for explicitly supporting students’ regulation of the composing process.

2.2. Metacognition

Metacognition is central to effective multimodal composition. Writers must understand not only their own learning processes but also how to flexibly apply strategies that suit the rhetorical demands of each mode (Flavell, 1979; Paris & Winograd, 2013). In multimodal contexts, metacognition encompasses decisions about which modes to use, how to integrate them cohesively, and how to assess whether they effectively communicate a message (Dalton & Grisham, 2011).

Research indicates that strong metacognitive skills are associated with the production of higher-quality multimodal products (Godwin-Jones, 2018; Zheng et al., 2020). For example, students who engaged in guided reflection throughout the creation of digital stories demonstrated greater awareness of how their choices affected meaning-making across visual and textual modes (Lamb & Johnson, 2019). Instruction that fosters metacognitive growth, through processes such as think-alouds, can enhance students’ control over multimodal design and foster transfer to future composing tasks (Lajoie & Azevedo, 2006; Yancey, 2004).

2.3. Cognitive Process Theory of Writing

The cognitive process model developed by Flower and Hayes (1981) posits that writing is a recursive, goal-driven activity composed of planning, translating, and reviewing. Central to this model is the idea of the writer as a problem-solver who moves fluidly among these subprocesses depending on the evolving needs of the task. This framework has been widely applied in composition studies and remains influential in both theoretical and empirical research (Hayes, 2012; Kellogg, 2008).

In multimodal composing, Flower and Hayes’s model can be extended to account for the integration of multiple semiotic systems. Planning may involve not only organizing ideas but also determining how to distribute information across visual, aural, and spatial modes (Prior & Shipka, 2003). Translation includes both linguistic expression and modal transformation, such as converting an idea into an infographic or video narration. Reviewing entails evaluating cohesion across modes and revising to enhance clarity and rhetorical impact. Scholars have advocated for revised models of writing that explicitly incorporate multimodal design and the affordances of digital composition (DeVoss et al., 2005; Shipka, 2005); yet Flower and Hayes’s model remains a foundational reference point for understanding the cognitive processes involved in composing.

2.4. Self-Regulated Strategy Development

Self-Regulated Strategy Development integrates cognitive strategy instruction with explicit self-regulation training (Harris & Graham, 1996; Harris et al., 2009). The model includes six recursive stages: (1) develop background knowledge, (2) discuss it, (3) model it, (4) memorize it, (5) support it, and (6) independent performance. It supports students in mastering both the procedural and metacognitive components of writing. SRSD has been shown to improve writing quality, motivation, and self-efficacy across diverse populations (Graham et al., 2015).

Recent empirical studies have extended SRSD into multimodal and digital composing contexts. For example, Coker and Ritchey (2015) adapted SRSD to support early writers composing digital picture books, finding improvements in both written and visual storytelling quality. Troia et al. (2020) demonstrated that SRSD could be successfully integrated into project-based learning units that involved video production and infographic design, particularly when paired with structured reflection prompts and peer feedback. The growing body of SRSD research in multimodal contexts highlights its flexibility and power as an instructional framework. SRSD’s focus on explicit teaching, goal setting, self-monitoring, and reflection aligns well with the complex demands of multimodal composition, particularly for developing writers. As educators increasingly incorporate digital and multimodal tasks in the classroom, SRSD provides a research-based approach to help students compose with intention, strategy, and confidence (Brindle et al., 2022; Graham & Perin, 2007).

2.5. Multimodal Composing in Education

Multimodal composing has become an essential component of education across the curriculum and various contexts. By integrating multiple sensory elements (e.g., visual, auditory, physical), multimodal composing enhances meaning-making, expression, communication, and comprehension in diverse educational environments (Kress, 2000). For young children, multimodal composing supports literacy development and other critical skills in various learning settings (van Leeuwen, 2011). In elementary education, multimodal composing often involves traditional methods, such as handwriting and drawing, as well as digital tools like Google Slides, Microsoft PowerPoint, Canva, and other multimedia programs (e.g., Cappello & Walker, 2021). As students develop digital literacy, more advanced formats of multimodal composing, such as digital coding and computational thinking, further enrich learning, particularly in interdisciplinary curricula that combine literacy with other areas, for example, computer science (Hutchison et al., 2025). Multimodal composing also benefits students with diverse backgrounds and abilities. For instance, Brown and Allmond (2021) observed a second-grade bilingual student using digital drawing tools to integrate oral language, written language, and visual modes, effectively expressing complex ideas. Similarly, Bruce and colleagues (2013) found, in their literature review, that students with disabilities improved their writing skills and composition quality through the use of assistive technology tools, demonstrating how multimodality can scaffold learning for diverse students.

At the same time, multimodal composing has been shown to help students explore ideas, learn new content, and engage meaningfully with the writing process. For example, Hutchison and colleagues (2025) created a Compose and Code digital platform to help elementary school students practice coding literacy through multimodal composing within a self-regulated setting. Also, technology-based tools demonstrated a positive impact on students’ composing scaffolds, quality, and skills (Bruce et al., 2013). Moreover, hand drawings serve as visual and thinking aids, facilitating students’ practice of literacy skills in content areas. Cappello and Walker (2021) conducted a study with fourth grade students, exploring how they use hand drawing to learn new vocabulary and science content knowledge. They found that students who drew scientific concepts demonstrated growth in their understanding, which integrated literacy skills into science content knowledge. To better support K–12 students in multimodal composing, in-service and preservice teachers are crucial in gaining knowledge of multimodal composing instruction and utilizing practical approaches to enhance the effectiveness of multimodal composing for their students.

3. Developing a Self-Regulated Multimodal Composing Framework

The development of the self-regulated multimodal composing (SRMC) framework is guided by perspectives on multimodal composing and self-regulated learning (e.g., Harris et al., 2002; Kress, 2000; Zimmerman, 2000). Using SRSD as a learning approach, students can practice their writing and composing skills by setting goals, planning in steps, interacting with peers, and monitoring their own progress (Sanders et al., 2019). Studies have demonstrated that SRSD in various contexts can enhance students’ writing skills, highlighting the positive effects of SRSD as an explicit strategy instruction (e.g., Kistner et al., 2010). In elementary education, multimodal composing features a self-regulation approach that substantially improves student skills in self-direction, coding literacy, and problem solving (Hutchison et al., 2025).

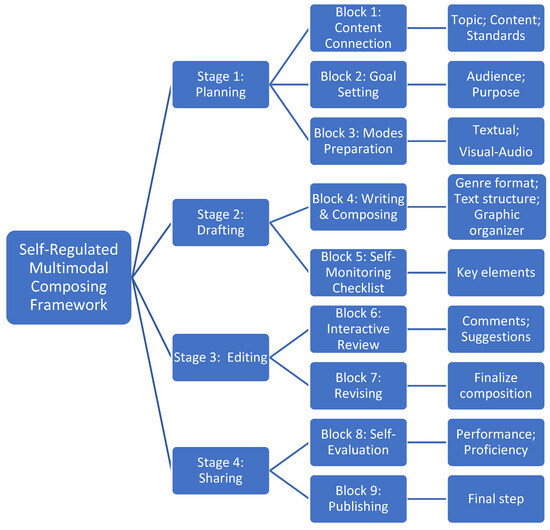

Grounded in SRSD, we integrated self-regulated learning stages into the SRMC framework, including planning, drafting, editing, and sharing. We further embedded nine blocks into the four stages to guide multimodal composing in procedures with detailed descriptions. Each block contains several key components to guide multimodal composing processes, such as content connection, audience awareness, mode affordances, and reflective activities.

Figure 1 shows the structure and details of the SRMC framework. Specifically, Block 1 focuses on content connection, meaning that learners choose the topic and content area for the composing based on the recommendations in academic standards. Block 2 focuses on goal setting, which learners should be aware of, so that the content closely reflects the goal and fits the audience’s understanding level. Additionally, the purpose of composition can be educational, informative, entertaining, or instructional modeling. Having a goal-setting block in the planning stage would help learners create multimodal compositions that convey central information more explicitly, thereby improving composing efficiency.

Figure 1.

Self-regulated multimodal composing (SRMC) framework.

Furthermore, Block 3 prepares learners to consider the most effective modes to integrate into their composition. By exploring different digital platforms and features, learners can choose the modes that they think the most appropriate for their compositions. In Block 4, learners begin to write and compose their work, ensuring it has a clear text structure based on the genre format they have chosen. A graphic organizer can support the composing process by creating an outline and filling in the details. Next, Block 5 guides learners to monitor their own progress using a checklist that includes all the key elements from previous blocks, which helps them check if they have included everything they intended to include in the composition. In Block 6, learners conduct interactive reviews with peers or other audiences and give feedback after reviewing others’ work. Then, learners can revise their composition based on the comments and suggestions in Block 7. Last, in Block 8, learners self-evaluate their composing process and experiences, performance quality, and multimodal composing proficiency. Finally, learners publish their work internally or publicly as the final step in Block 9.

In summary, the SRMC framework aims to provide universal guidance for learners at all levels to engage in multimodal composing. It can be implemented across various digital platforms or paper-based mediums, and its modular components are adaptable to diverse learner needs, depending on their comprehension and skill levels. As a result, the SRMC framework offers a flexible and adaptive approach to multimodal composition, supporting a wide range of multimodal tools and formats.

4. Methods

After developing the SRMC framework, we wanted to determine its effectiveness with a group of elementary preservice teachers and first grade students. In the following sections, we describe the pilot testing procedure and present our findings.

4.1. Participants

Our piloting of the SRMC framework was focused on 22 preservice teachers enrolled in the Teaching Language Arts course at a western state university in the Spring 2025 semester. The primary objectives of the course include genre-based writing instruction, teaching strategies of English Language Arts in K–6 schools, multimodal literacy practices, and writing instruction approaches in content areas. The participants were senior undergraduate students in the elementary teacher education program, and they were in their final semester of coursework, preparing to participate in a student teaching internship in the following semester. Before enrolling in this course, participants had completed coursework in reading literacy instruction and had varied experiences working with K–6 students in schools, literacy clinics, or out-of-school programs. Additionally, all the participants have experience in utilizing common instructional digital platforms, such as Google Slides, Microsoft PowerPoint, Canva, and other multimedia platforms. Eighteen of the total 22 preservice teachers have signed informed consent, indicating their agreement to participate in the present study. Therefore, we collected data only from these 18 preservice teachers, although all preservice teachers participated in the multimodal composing module as a regular class activity.

Additionally, in the Spring 2025 semester, we recruited a single classroom of first graders at a charter school in a western state for the present study. The first-grade classroom teacher is a female, White, with over 20 years of teaching experience in elementary schools and more than 6 years of experience teaching first grade. There are 24 students in this classroom, and they all completed the writing task using the self-regulated graphic organizer during their regular class session, which lasted approximately 45 min. The task asked students to write a sequential story that included procedures for making or doing something. On the graphic organizer, students reviewed the blocks and filled out the content. The multimodal composing included text writing and drawing pictures that reflected the written story. A total of 19 students whose parents/guardians have signed the informed consent form indicating their agreement for their child to participate in this study.

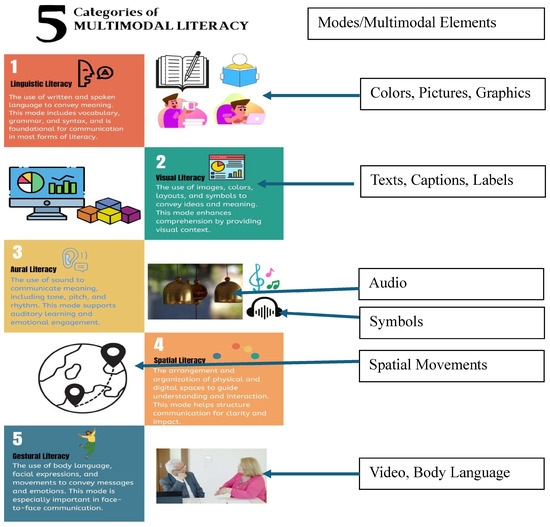

4.2. Context of Preservice Teachers

We used an example of a digital module on Canvas platform, which we created for elementary preservice teachers to conduct multimodal composing in class, to explain how preservice teachers use each stage and block of the SRMC to complete a genre-based multimodal composition task. The task asked preservice teachers to create a multimodal composition of informative text as a model or mentor text for use in elementary instruction. Using their own devices (e.g., laptops, tablets), the preservice teachers conducted multimodal composition at their own pace by accessing the Canvas module (see Figure 2) and reading through the descriptions on each block page.

Figure 2.

Canvas module front page.

The preservice teachers were given 50 min at one of their regular class sessions to complete the entire module. Although the task was individual work, communication and collaboration with peers were encouraged throughout the process. The blocks guide the preservice teachers in choosing a topic, content area, grade level, and composition format. The composition was intended to align with the grade level’s content and topic suggested by state standards, and the texts should support the elementary students’ comprehension and learning needs. On the front page of the Canvas module, we provided a brief introduction to the multimodal composing task, along with a list of the nine blocks.

4.3. Contexts of First Graders

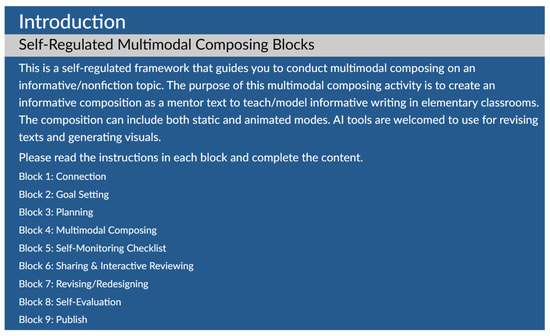

The SRMC framework can help young students with multimodal composing. To analyze the SRMC’s usefulness with early elementary children’s multimodal composing on paper and print-based format, we created a self-regulated graphic organizer that incorporates the stages of the SRMC framework to guide young students in developing genre-based compositions. We slightly modified the blocks and key elements in this graphic organizer to better align with the level and modal affordances of first-grade students. Due to their young age, elementary students may encounter challenges in composing multimodally on digital platforms. Also, elementary school teachers may have concerns about the efficiency and security issues that arise when students use technology or digital platforms in the classroom. Some elementary teachers, especially those teaching in lower grades, prefer to use print-based materials and graphic organizers to help students develop handwriting skills. The graphic organizer enables students to plan their story, write key sentences of their story, draw pictures to illustrate their story, interact with a peer during review, and conduct self-monitoring and self-evaluation independently.

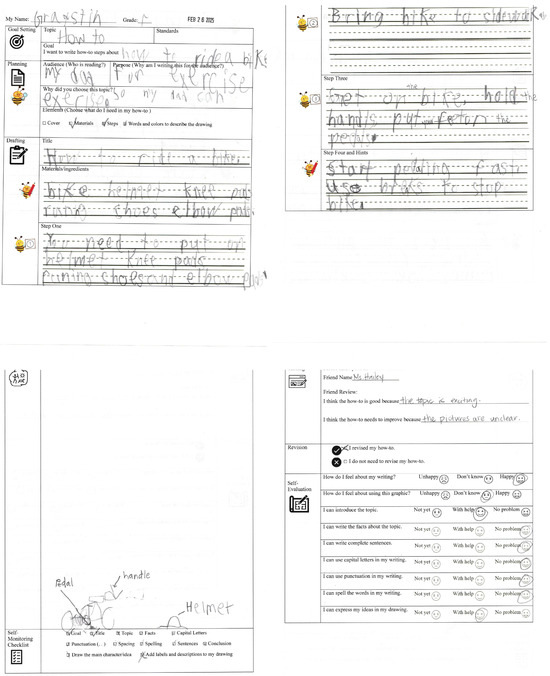

The task asked students to write a sequence informational story on the topic of “how to …”, for example, “how to make a lemonade”, “how to take care of pets”, or other procedure-based stories. The sequential writing text should include a title and at least four steps or procedures related to the topic. The print-based self-regulated graphic organizer (see Figure 3) includes the self-regulation stages and adapted blocks from the SRMC framework, including goal setting, planning, drafting, drawing, self-monitoring checklist, sharing, revision, and self-evaluation. It incorporates both handwriting and hand drawing as multimodal composing practices. Under the teacher’s guidance and instruction, students worked on the graphic organizer step-by-step.

Figure 3.

Self-regulated graphic organizer for sequential writing.

5. Findings

5.1. Stage of SRMC for Preservice Teachers

Overall, the preservice teachers’ compositions integrate multiple modes to present the content knowledge, including linguistics (e.g., words, captions, titles, fonts, labels), static visuals (e.g., pictures, images), and animations (e.g., video, audio). The results showed a comprehensive integration of multimodal elements under the use of the SRMC framework. We use one preservice teacher’s work as an example to explain how preservice teachers engage in multimodal composing using this SRMC featured Canvas module.

- Stage 1: Planning

The Planning stage includes three blocks: Block 1, Content Connection; Block 2, Goal Setting; and Block 3, Modes Preparation. These blocks guide learners to focus on central information communication and plan out the composition based on the goal or the central information. Additionally, these blocks offer scaffolded guidance for learners to craft a composition with thoughtful consideration of the audience’s knowledge and comprehension level, aligning with the purpose of the composition. One preservice teacher says in the reflection: “I think the self-regulated blocks were very helpful when doing the multimodal composing. Having step-by-step guides allow me to fully understand the expectations as well as be able to focus on my timing.”

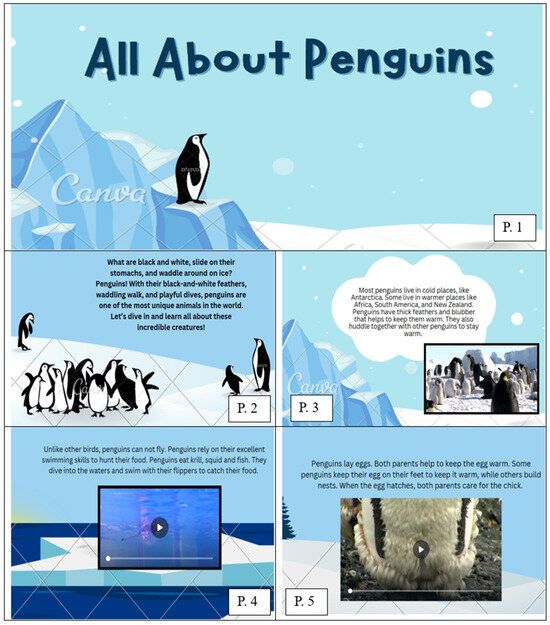

Block 1, Content Connection, provides guidance on connecting multimodal composing to specific topics and genres (e.g., narrative, informative, argumentative texts), which is based on learning needs in content areas (e.g., ELA, science, social studies) or abilities development, such as social-emotional learning. In the Canvas module, we provide suggestions on common areas in elementary classrooms, including science-related topics such as earth, nature, plants, animals, and geography, as well as social studies topics like people, history, society, events, sports, and cultures. Additionally, the chosen subject or content should align with the state or national curriculum standards. Through content connection, preservice teachers can demonstrate their thinking and comprehension of the selected area in their multimodal compositions. For example, one preservice teacher chose penguins as the topic of science content that aligns with first or second-grade standards.

Block 2, Goal Setting, provides guidance on audience awareness and the purpose of multimodal composition. Multimodal compositions can serve different goals in educational practices. Preservice teachers can use compositions to demonstrate their comprehension of a topic or content. Additionally, they can interact with peers through multimodal composing and develop various skills, such as critical thinking, problem-solving, digital coding, and sequential reasoning. Additionally, they can use compositions as a mentor text or model for instructional purposes and connect them to the state or national standards. In our class, the task asked preservice teachers to create a multimodal composition as a mentor text to teach or model informational writing in elementary classrooms. Furthermore, audience awareness ensures that preservice teachers tailor the composition content to the comprehension and knowledge level of the students’ group they have chosen. For example, one preservice teacher chose penguins as the topic to teach science content that aligns with young students’ knowledge and comprehension level. The preservice teachers believe that the beginning blocks of the planning stage are helpful for them to obtain a headstart in relation to multimodal composing; for example, one reflects the following:

“These blocks helped me select a topic connected to common content areas in elementary classrooms, directly addressing at least one of the State Standards. I was able to do important “pre-work” that helped me commit to a direction for my composition and prevented me from needing major edits later.”

Block 3, Modes Preparation, guides the choice of appropriate modes that can effectively facilitate multimodal composing. In this block, preservice teachers may choose from various textual and visual-audio modes or features using different digital platforms, such as Google Slides, Canva, Microsoft PowerPoint, and other multimedia platforms. Print-based or handwritten elements can also be appropriately integrated into multimodal compositions. Common modes include static visual representations and animated modalities such as audio, sounds, music/songs, and videos. The combination of multiple modes will create meaningful information and facilitate communication or comprehension. For example, the preservice teacher who chose penguins as the content has integrated pictures, texts, and videos into the composition to better serve as a mentor text for young students. The preservice teachers appreciate the scaffolding procedures for multimodal composing, one says in the reflection that “When multimodal composing, there are so many different options you can use to create your story. Self-regulated blocks can be helpful because it gives you a list of steps you need to do.”

- Stage 2: Drafting

Based on the audiences and purposes in the planning stage, multimodal composing may incorporate various information through different modes and elements integrated into the composition. The Drafting stage includes two blocks: Block 4, Writing and Composing; and Block 5, Self-Monitoring Checklist. In these blocks, learners begin to create multimodal writing and composition, then use a self-monitoring checklist to track progress.

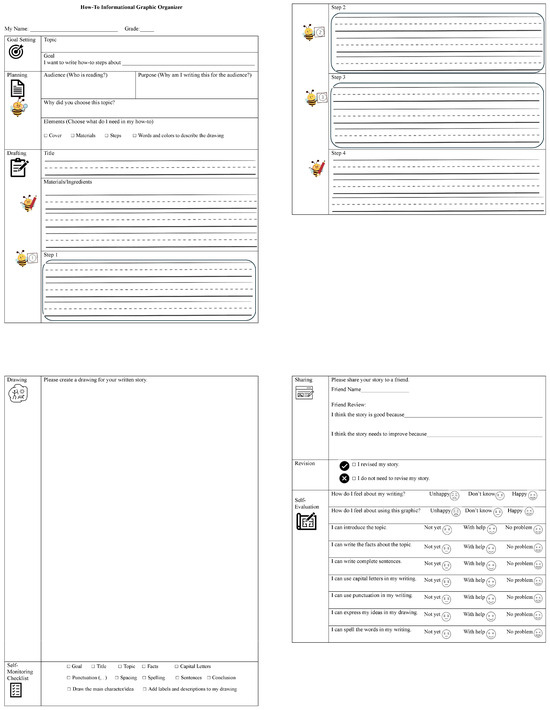

Block 4, Writing and Composing, has three sections to guide the composition creation process, including genre formats (e.g., narrative, informational, opinion/argumentative texts), key components of the text (e.g., topic sentence, characters, plots, details, facts, claims, ending), and modes integration (e.g., textual, visual, audio). First, text writing should follow a genre-based structure to organize the texts logically and reasonably. Common structures for informative/nonfiction texts include description, sequence, comparison and contrast, cause and effect, and problem and solution. Having a clear structure would make the text easier for readers to follow. Then, adding key components to the text also needs to follow the genre and text structure, for example, an informative text needs to include clear descriptions, facts, and details. Preservice teachers may consider using a graphic organizer or thinking map to support a smooth writing and composing process. Moreover, modes integration requires learners to include multiple visual or animated modes beyond texts. Depending on the platform they choose and the content of the composition, preservice teachers may opt to use hand-drawn images, static pictures, or integrate more advanced meaning-making modes, such as audio, sounds, video, animations, visual-spatial movements, and other interactive elements (e.g., hyperlinks, text-to-speech). We provide a digital infographic example for preservice teachers to understand how multiple modes can be integrated into a single composition (see Figure 4). This infographic incorporates various elements, including text, captions, labels, colors, symbols, images, graphics, spatial elements, audio, and video. Using this infographic as an example, preservice teachers begin to design and compose their multimodal project using different modes.

Figure 4.

Infographic example.

Block 5, Self-Monitoring Checklist, aims to improve the efficiency of multimodal composing. The checklist contains all the key elements that should be double-checked or included in the multimodal composition, such as goal, title, topic, topic, facts, conclusion, grammar, spelling, sentences, text structure, text features, and multimodal elements. This process helps preservice teachers to ensure the final composition aligns with the goal, purpose, structure, and all the key elements as they planned prior to composing. In this stage, preservice teachers finish their first draft or version of multimodal composition and prepare for peer interactions in the next stage. The preservice teachers believe that the checklist was helpful for them to organize their composition, one says “I do think the blocks were super helpful for the multimodal composing because it helped me to have an outline of what to do in what order, which helped keep me on track.”

- Stage 3: Editing

The “Editing” stage includes an interactive peer review and a revising step based on the peer’s comments. Block 6, Interactive Review, requires preservice teachers to share their own work with peers and post it on an interactive platform, before reviewing others’ work and making comments or suggestions. Several guiding questions can be used for the process: (1) Is the writing or text clear and detailed on the topic? (2) Do the multimodal elements in the work have meanings and help support content comprehension? And (3) What are the most effective modes and distracting elements in the composition? These guiding questions are designed to help learners make meaningful comments and suggestions to their peers. In class practice, we asked the preservice teachers to share their work on the Canvas Discussion board and give comments on their peers’ work. They enjoyed the peer review process, one says “I think that the most effective block for me was the interactive peer review. It was helpful for me to see other ways my peers used multimodal composing to inform their audience.” Another preservice teacher says “I thought the most helpful blocks were 6–8. These steps made the revising process simple.”

After reading their peers’ comments, learners can revise and finalize their work in Block 7. With the finalized version of the composition, preservice teachers prepare to publish and reflect on their work in the next stage. For example, the preservice teacher who created the composition on penguins received a suggestion to add some interactive modes or videos to the project. Then the preservice made that revision on the final version of the composition (See Figure 5). In the final version of the composition, the preservice teacher created a presentation project on Canva, integrating texts, pictures, and videos to facilitate comprehension of the topic.

Figure 5.

A working sample from a preservice teacher.

- Stage 4: Sharing

The “Sharing” stage includes self-reflection and peer-sharing/publishing steps. Block 8, Self-Evaluation, comprises 10 items with multiple-choice options to indicate the self-reflected or self-evaluated levels of the item statements (see Table 1). The self-evaluation items related to the performance of multimodal composing, the proficiency of utilizing platforms to create multimodal compositions, and the self-efficacy of multimodal composing. These items can help preservice teachers reflect on their progress and abilities. As shown in Table 1, the numbers indicate the responses of preservice teachers on each category. From the results, the majority of the preservice teachers indicated the highest level of self-efficacy (i.e., very much, proficient, and often) in their ability to conduct multimodal composition. Specifically, 14 out of total 18 preservice teachers indicated they have effectively planned their composition, and 13 of them believed that they have effectively integrated multimodal elements into their composition. Additionally, 15 preservice teachers believed the blocks were helpful for them to monitor their own progress, and 16 preservice teachers effectively engaged with peers on collaborations and interactions.

Table 1.

Self-evaluation form and responses (N = 18).

Finally, in Block 9, preservice teachers publish the final version of their work on the platform they used to create the composition and share the link or file with the Canvas discussion board as the final step.

Based on our pilot testing, we concluded that the SRMC framework effectively combines both autonomous learning and collaboration in multimodal composing. Specifically, the “Planning” and “Drafting” stages featured autonomy and self-regulated learning, while the “Editing” and “Sharing” stages facilitated collaboration and communication. The blocks allow the preservice teachers to learn from peers and be inspired to improve their work by reviewing their peers’ work and sharing ideas with them. These blocks help preservice teachers to scaffold knowledge and guide the composing processes under autonomous learning, then share their work with peers and conduct interactive peer review, so they may notice flaws or errors in their work and learn how to improve it based on suggestions from peers. Therefore, the nine blocks within the four self-regulated learning stages in the SRMC framework are cohesive and purposeful, guiding learners to conduct multimodal composing effectively.

5.2. Stage of the Graphic Organizer for First Graders

Overall, the first-grade students demonstrated efficiency of using this graphic organizer on multimodal composing. Table 2 shows the details of the 19 students’ work and the levels of multimodal interpretation, meaning to what extent the drawings reflect or represent the written story. From the results, we can see that the majority (N= 14) of the first graders were able to create clear (e.g., very well, and somewhat) drawings to match the written story using this graphic organizer. We use one student’s work as an example (see Figure 6) to illustrate how first graders engage in multimodal composing using this self-regulated graphic organizer.

Table 2.

Multimodal compositions of first graders (N = 19).

Figure 6.

Example of student’s completed work.

- Stage 1: Planning

On the first page of the graphic organizer, students begin planning their multimodal composition by setting a goal. They select a topic for their sequential story and complete the sentence starter “I want to write how-to steps about…” to define their objective. Next, they consider their intended audience and briefly explain their topic choice. A short checklist is provided to guide students in outlining key elements for their work. In the student’s working example, the student chose “how to ride a bike for exercise” as the topic and identified his dad as the audience.

- Stage 2: Drafting

During this stage, students use the keywords and hints provided in the graphic organizer boxes to draft their procedure-based sequential writing. The template guides students in structuring their sequential steps, with clear sections for title, required materials/ingredients, and numbered steps 1–4. Additional blank spaces allow students to extend their writing if more steps or details are needed. To enhance the composition, students then create accompanying drawings as illustrations that either complement or further clarify their written story with more elements. In the student’s sample, his story was titled “How to Ride a Bike” and listed necessary equipment, including a bike, helmet, knee pads, running shoes, and elbow pads. After drafting the step-by-step details, he completed the composition by drawing a picture of a bike in the designated space.

- Stage 3: Editing

In this stage, students review their compositions using a self-monitoring checklist to verify they have included all essential elements. After making any necessary revisions identified through this self-monitoring step, students engage in peer review and conferencing with their teacher. The reviewer provides brief written feedback, including their name and specific suggestions. Students then consider these recommendations and document in the revision box whether they have incorporated the changes. As shown in the student’s example, he first completed the self-monitoring checklist to track the included elements. After sharing the work with the teacher, he received specific feedback suggesting visual enhancements to the drawing. Acting on this advice, the student added labels to the drawing for better clarity and jotted the revision in the designated box.

- Stage 4: Sharing

In this final stage, students complete their entire work and engage in self-evaluation using the last section on the graphic organizer. To support comprehension and decision-making, each evaluation item includes smiley face icons representing different achievement levels, and students color or circle the icon that best matches their performance. Following this reflection, the teacher displays the finished compositions on the classroom wall, serving as a formal “publishing” stage for students to share and appreciate the work with peers. The student’s example demonstrates this process effectively, in which the student carefully circled the icons that best describe themselves for each item. Therefore, the smiley face icons enabled effective self-evaluation, while the classroom display celebrated the completion of the multimodal composing task.

Our practice with the adapted SRMC framework revealed that first-grade students actively engaged with the graphic organizer and the structured stages. The organizer effectively supported self-regulation strategies, including independent work, self-monitoring, peer interaction, and self-evaluation, throughout the multimodal composition process. Unlike the digital Canvas module designed for preservice teachers, this print-based graphic organizer is more appropriate for the development of young students. The format accommodates emerging handwriting and literacy skills, providing tangible scaffolding for multimodal practices. Additionally, we simplified the original SRMC framework’s blocks into clearer and more manageable boxes, tailored to the cognitive and learning needs of first graders.

6. Discussion

Based on the findings of the two pilot studies, the structured blocks and components of the SRMC framework offer a practical and universally adaptable approach to multimodal composing that engages all learners. The significance of the present study includes confirming the theoretical foundations of self-regulation and multimodal literacy for the development of the SRMC framework, demonstrating the implementation of the SRMC framework to both teacher education and elementary teaching practices on effective multimodal composing, and exploring the flexibility and adaptation of the SRMC framework to print-based materials for young children.

Our implementations demonstrate that both preservice teachers and young students successfully utilized this framework to guide their multimodal composition processes with self-regulation skills. The findings confirm the flexibility of SRMC instructional methods across different age groups and modalities. Specifically, the SRMC framework demonstrates how learners engage in goal-oriented, reflective, and collaborative composing activities, which are essential elements of self-regulated learning. It aligns with Zimmerman’s (2002) cyclical model, where learners plan, monitor, and assess their progress. It also supports Flower and Hayes’s (1981) cognitive process theory of writing by enabling recursive and adaptable composition processes. Built upon the SRSD approach (Harris et al., 2009), the SRMC framework effectively helps both preservice teachers and first-grade students further demonstrate its flexibility, strengthening its position as a scalable and developmentally suitable tool that effectively links theory to classroom practice.

The results of the Canvas module and the graphic organizer reveal how each tool aligns with the SRMC stages and supports learners on effective multimodal composing. Specifically, the Canvas module and blocks helped preservice teachers to conduct multimodal composing for elementary instructional purposes by aligning the composition with the content and goals described in the state academic standards. Using the composing blocks and checklist, preservice teachers can monitor their progress and keep themselves on track. The peer interview and sharing engaged preservice teachers to interact with peers and learn from each other. Additionally, the graphic organizer demonstrated how educators can integrate self-regulation strategies to multimodal writing instruction to young students. The print-based format enables young students to practice handwriting and drawing skills, which are essential for early ages multimodal composing. The revision and self-evaluation blocks on the graphic organizer helped first-graders to revise their work based on peers’ comments and to evaluate their own experience of using the graphic organizer.

The implementation of the SRMC framework through these two tools highlighted key differences based on the learners’ cognitive readiness and instructional needs. The Canvas module, developed for preservice teachers, encouraged autonomous learning engagement by offering flexible navigation, embedded guidance, and opportunities for reflection. These features aligned well with the advanced self-regulation skills of adult learners, who are typically capable of independently setting goals, monitoring their progress, and revising their work based on internal feedback (Zimmerman, 2002). On the other hand, the printed graphic organizer provided a more structured and visual approach tailored to younger students. By presenting composing steps in a clear and sequential format, it reduced cognitive load and provided explicit scaffolding to support planning, organizing, and reflecting during composition. This approach aligns with prior research, which shows that graphic organizers with embedded self-regulated learning strategies can significantly enhance students’ ability to manage and monitor their writing tasks (Hughes et al., 2019). Together, these findings highlight the importance of scaffolding and the flexibility of the SRMC framework in addressing the diverse needs of all learners.

6.1. Implications for Teaching and Teacher Education

The SRMC framework and our pilot studies offer valuable insights for teachers and instructional practices. Integrating this self-regulated framework into writing tasks supports all learners in developing and practicing their multimodal literacy. By employing differentiated design in instruction, educators can tailor the SRMC framework to fit students’ comprehension levels and learning needs. For instance, younger students might engage with simpler multimodal composing modes, while older students can explore more advanced features to craft digital multimodal compositions. Scaffolding self-regulation through explicit prompts, which guide students in planning, monitoring, and reflecting on their progress, could enhance engagement and foster independent learning. Furthermore, teachers and preservice teachers should be trained in modeling self-regulation in multimodal composing and demonstrating how to apply it in real-time classroom instruction.

Despite the benefits of the SRMC framework, implementing this framework presents challenges, including varying student readiness levels and the cost barriers of multimodal creations. However, strategic adaptations can help overcome these obstacles. For example, providing tiered scaffolding, ranging from high support to gradual release of responsibility, ensures all students can access learning at their own pace and level. Professional development should also include strategies to address common challenges, such as resistance to self-regulation or technology barriers. By addressing these challenges, teachers can create a flexible and responsive learning environment that empowers all students to conduct multimodal composing.

6.2. Implications for Future Research

To further validate and expand the SRMC framework, future research should examine its long-term effects on students’ multimodal literacy growth by systematically analyzing learners’ multimodal compositions. Although this study showed promising practical results in instructional settings, more studies need to be conducted to evaluate how ongoing engagement with the SRMC framework supports the development of self-regulation, multimodal composing skills, and overall literacy achievement over time. Monitoring learners across academic years could shed light on how early exposure to structured composing frameworks contributes to long-term academic success and metacognitive development.

Furthermore, the effectiveness of the SRMC framework should be tested in various educational contexts, including different grade levels, subject areas, genres, and student populations. Implementing and assessing the framework in diverse classrooms and schools can provide a deeper understanding of its adaptability in supporting literacy development across contexts. Such research would help refine the framework for wider implementation and guide the development of differentiated instructional strategies to meet the diverse needs of 21st century learners.

7. Conclusions

The SRMC framework scaffolds multimodal composing through self-regulated strategies from goal setting to peer collaboration and self-evaluation. It empowers learners across various developmental stages to systematically plan and create multimodal compositions, exercising independent learning through the use of metacognitive strategies. Notably, the flexibility and adaptability of the SRMC framework allow educators to tailor implementations to learners’ needs across educational contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.S.; methodology, Q.S. and T.S.H.; formal analysis, Q.S.; writing original draft, Q.S., T.S.H. and V.M.; writing-review and editing, T.S.H. and V.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Utah State University (#14764, 25 November 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is not available to public due to privacy and ethical considerations required by IRB.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Brindle, M., Harris, K. R., Graham, S., & Sandmel, K. (2022). Adapting SRSD for new literacies: Supporting multimodal composing in the elementary classroom. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 38(2), 130–152. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S., & Allmond, A. (2021). Constructing my world: A case study examining emergent bilingual multimodal composing practices. Early Childhood Education Journal, 49(2), 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, D., Di Cesare, D. M., Kaczorowski, T., Hashey, A., Boyd, E. H., Mixon, T., & Sullivan, M. (2013). Multimodal composing in special education: A review of the literature. Journal of Special Education Technology, 28(2), 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brueck, J. S., & Lenhart, L. A. (2015). E-books and TPACK: What teachers need to know. The Reading Teacher, 68(5), 373–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappello, M., & Walker, N. T. (2021). Talking drawings: A multimodal pathway for demonstrating learning. The Reading Teacher, 74(4), 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.-H., & Lim, S. (2017). Using self-regulated learning strategies to enhance online learners’ meta-cognitive awareness. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 13(1), 11–27. [Google Scholar]

- Coker, D. L., & Ritchey, K. D. (2015). Teaching beginning writers. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton, B. (2014). Level up with multimodal composition in social studies. The Reading Teacher, 68(4), 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, B., & Grisham, D. L. (2011). eVoc strategies: 10 ways to use technology to build vocabulary. The Reading Teacher, 64(5), 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVoss, D., Cushman, E., & Grabill, J. T. (2005). Infrastructure and composing: The when of new-media writing. College Composition and Communication, 57(1), 14–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive–developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34(10), 906–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flower, L., & Hayes, J. R. (1981). A cognitive process theory of writing. College Composition and Communication, 32(4), 365–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, B., Higgins, K. N., & Horney, M. (2016). How students communicate mathematical ideas: An examination of multimodal writing using digital technologies. Contemporary Educational Technology, 7(4), 281–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godwin-Jones, R. (2018). Using mobile technology to develop language skills and cultural understanding. Language Learning & Technology, 22(3), 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, S., Harris, K. R., & Santangelo, T. (2015). Research-based writing practices and the Common Core: Meta-analysis and meta-synthesis. The Elementary School Journal, 115(4), 498–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S., & Perin, D. (2007). Writing next: Effective strategies to improve writing of adolescents in middle and high schools. Carnegie Corporation of New York. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, K. R., & Graham, S. (1996). Making the writing process work: Strategies for composition and self-regulation. Brookline Books. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, K. R., Graham, S., Brindle, M., & Sandmel, K. (2009). Metacognition and children’s writing. In D. J. Hacker, J. Dunlosky, & A. C. Graesser (Eds.), Handbook of metacognition in education (pp. 131–153). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, K. R., Graham, S., Mason, L. H., & Saddler, B. (2002). Developing self-regulated writers. Theory into Practice, 41(2), 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, E., & McTavish, M. (2018). ‘I’babies: Infants’ and toddlers’ emergent language and literacy in a digital culture of iDevices. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 18(2), 163–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J. R. (2012). Modeling and remodeling writing. Written Communication, 29(3), 369–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M. D., Regan, K. S., & Evmenova, A. S. (2019). A computer-based graphic organizer with embedded self-regulated learning strategies to support student writing. Intervention in School and Clinic, 55(1), 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, A., Si, Q., Colwell, J., Kaya, E., Jakeway, E., Miller, B., Gutierrez, K., Regan, K., & Evmenova, A. (2025). Scaffolding coding instruction through literacy via the Compose and Code digital platform and curriculum. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 41(1), e13115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellogg, R. T. (2008). Training writing skills: A cognitive developmental perspective. Journal of Writing Research, 1(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kistner, S., Rakoczy, K., Otto, B., Dignath-van Ewijk, C., Büttner, G., & Klieme, E. (2010). Promotion of self-regulated learning in classrooms: Investigating frequency, quality, and consequences for student performance. Metacognition and Learning, 5(2), 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress, G. (2000). Multimodality. In B. Cope, & M. Kalentzis (Eds.), Multiliteracies: Literacy learning and the design of social futures (pp. 182–202). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lajoie, S. P., & Azevedo, R. (2006). Teaching and learning in technology-rich environments. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 67–69. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, A., & Johnson, L. (2019). Digital storytelling in literacy and learning. In Teacher librarian, learning and teaching for the digital world. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- McVee, M. B., Bailey, N. M., & Shanahan, L. E. (2018). Multimodal composing in classrooms: Achievement: Theoretical perspectives (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Paris, S. G., & Winograd, P. (2013). How metacognition can promote academic learning and instruction. In B. F. Jones, & L. Idol (Eds.), Dimensions of thinking and cognitive instruction (pp. 15–51). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak, D. L., Varga, K., & Young, M. (2022). Designing digital learning environments to foster self-regulated learning in adolescents. Educational Technology Research and Development, 70(1), 145–162. [Google Scholar]

- Prior, P. A., & Shipka, J. (2003). Chronotopic lamination: Tracing the contours of literate activity. In C. Bazerman, & D. Russell (Eds.), Writing selves, writing societies: Research from activity perspectives (pp. 180–238). (Perspectives on writing). The WAC Clearinghouse and Mind, Culture, and Activity. Available online: https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/books/selves_societies/prior/prior.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Sanders, S., Losinski, M., Parks Ennis, R., White, W., Teagarden, J., & Lane, J. (2019). A meta-analysis of self-regulated strategy development reading interventions to improve the reading comprehension of students with disabilities. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 35(4), 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipka, J. (2005). A multimodal task-based framework for composing. College Composition and Communication, 57(2), 277–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Q., Hodges, T. S., & Coleman, J. M. (2022). Multimodal literacies instructions for K–12 English speakers and English language learners: A review of research. Journal of Literacy Research and Instruction, 61(3), 276–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Q., Suh, J. K., Ercan-Dursun, J., Hand, B., & Fulmer, G. W. (2024). Elementary teachers’ knowledge of using language as an epistemic tool in science classrooms: A case study. International Journal of Science Education, 47(2), 232–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. R. (2020). Multimodal literacies and self-regulation in secondary writing classrooms. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 63(4), 421–429. [Google Scholar]

- The New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 60–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troia, G. A., Olinghouse, N. G., & Kopke, R. A. (2020). Developing writing performance and motivation through SRSD in project-based learning. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101857. [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen, T. (2011). Multimodality. In The Routledge handbook of applied linguistics (pp. 668–682). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Yancey, K. B. (2004). Made not only in words: Composition in a new key. College Composition and Communication, 56(2), 297–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B., Warschauer, M., Lin, C.-H., & Chang, C. (2020). Learning in one-to-one laptop environments: A meta-analysis and research synthesis. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 1052–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Attaining self-regulation: A social cognitive perspective. In M. Boekaerts, P. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 13–39). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2002). Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory Into Practice, 41(2), 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B. J., & Schunk, D. H. (Eds.). (2011). Self-regulated learning and academic achievement: Theoretical perspectives (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).