Abstract

Higher education can promote environmental awareness and action through hidden curricula. This study at the Witten/Herdecke University examined the impact of the Human–Animal Studies course on students’ environmental awareness and behavior, comparing participants with the general student population. A cross-sectional and longitudinal survey was conducted using a 12-question Likert-scale questionnaire. Course participants were surveyed three times, while the general student body was surveyed once. In addition, reflective writing was qualitatively analyzed to assess changes in attitudes and behaviors. The results showed that both groups exhibited high levels of environmental awareness and behavior, exceeding the German population average. Female students showed greater commitment than male students. While no significant differences were found between course participants and other students, reflections indicated that the course promoted personal awareness and behavioral change and that the course encouraged participants to think about changes in their attitudes and behaviors toward the environment. These findings suggest that courses such as Human–Animal Studies can promote environmental awareness and self-reflection among students.

1. Introduction

The beginning of the 21st century is marked by the intensification of climate change, with implications for many areas of life (Jones, 2022). Along with many other challenges, recent environmental disasters (including floods and forest fires) draw attention to the need for changes in (environmental) behavior. The key to this is a change in society in the form of a confrontation with development and a resulting environmental awareness and behavior that strives for change.

One place that can contribute to this is the university. According to Frey et al. (2021), all students, regardless of their professional background, are citizens of society and can shape it. Furthermore, universities educate individuals who will later make groundbreaking decisions in politics, business, and science (Frey et al., 2021). In this context, Rossa-Roccor et al. (2021) see academics as having a responsibility to take an active role in knowledge and action around the climate crisis, and thus to drive policy change. The authors therefore argue that knowledge and action skills, as well as values and attitudes that guide action, should be taught in universities as part of the curriculum (Rossa-Roccor et al., 2021).

Universities across Germany are showing increasing interest in providing students with opportunities to engage with environmental issues. At the University of Kassel, for example, the project study “Teaching for a Sustainable University” was already offered in the summer semester of 2012 to teach environmental awareness, as well as awareness of resources and sustainability (Chrubasik & Fink, 2018). In 2018, the University of Hamburg offered the seminar “Experiencing Sustainability Naturally”, in which students could explore the relationship between humans and nature through a self-awareness exercise. In addition, the seminar was primarily intended to address the fact that knowledge about sustainability does not necessarily lead to sustainable behavior (Ghaffari, 2018).

This focused discrepancy between personal environmental awareness, intentions formed from this awareness, and demonstrated environmental behavior, which was also addressed in a seminar at the University of Hamburg, is intensively studied in research. While environmental awareness is formed from environmental knowledge, subjective concern, and behavioral intentions toward the environment, there are other causalities for environmental behavior. Behavioral intentions play a crucial role in the final environmental behavior, which is influenced by environmental knowledge, emotional concern, and social embeddedness and behavioral control (e.g., money or time) (Altenbuchner & Tunst-Kamleitner, 2019). This makes it clear that teaching and knowledge transfer alone will not lead to behavioral change, but that emotional involvement and an environment in which sustainable behavior becomes attractive and desirable must also be created.

1.1. Hidden Curricula

One way to facilitate this combination in the context of higher education teaching is through hidden curricula. In addition to official curricula, there are also informal or hidden curricula in higher education (Lawrence et al., 2018). This form of curriculum dates back to the 1960s (Meyer, 1988). Even in the past, this model has been held responsible for the internalization of role and behavioral norms, especially regarding socially desirable behavior (Zinnecker, 1975). In a review, Lawrence et al. (2018) were able to divide the hidden curricula described in medical education studies into four groups in terms of their mediated content and goals: (1) institutional–organizational, (2) interpersonal–social, (3) contextual–cultural, and/or (4) motivational–psychological curricula. Hidden curricula are thought to be highly influential, but unfortunately their current use is limited (Lawrence et al., 2018). It seems advantageous to take advantage of the connections between knowledge transfer and concern in the context of environmental awareness and behavior and to pursue a form of hidden curricula with an increased interpersonal–social and motivational–psychological orientation as a university, if this value transfer is part of one’s understanding. The peculiarity of the hidden curriculum is that content is implicitly conveyed through structural and human factors. Learning therefore takes place on a meta-level, and the goals are only partially plannable because attitudes, skills, aspirations, and behavioral and social expectations are conveyed (Andarvazh et al., 2017).

1.2. “Human–Animal Studies” at Witten/Herdecke University

Witten/Herdecke University (UW/H) in Germany, as a model university, pursues the goal of being a free, socially acceptable, sustainable and open institution. To achieve this, the university wants to “focus on sustainability in teaching, research and campus life” and contribute to a climate-friendly and livable future (Witten/Herdecke University, 2025b). The extension, which will open in 2021, has been named one of the most sustainable university buildings in Germany (Witten/Herdecke University, 2025c). The cafeteria offers an increasingly vegan and vegetarian menu, partly organic, with seasonal and regional character, partly harvested by students and staff (Witten/Herdecke University, 2024b, 2024c). Students are encouraged to use public transportation and electric cars through a car-sharing service. Extensive bicycle parking in the new building and showers facilitate bicycle commuting, and bicycles can be provided as company vehicles to employees. In addition, UW/H purchases only green electricity (Witten/Herdecke University, 2024b).

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals are also pursued by UW/H (United Nations, 2025; Witten/Herdecke University, 2024b). Most of the 17 declared goals are fundamentally dependent on adequate environmental awareness and behavior, which further reinforces the need for focus in UW/H’s teaching and community. The General Studies program, called Studium Fundamentale (StuFu), can be seen as an approach to achieving Sustainable Development Goal 4 (quality education). This teaching concept across courses and semesters includes various courses under assignment to the three focal points, (1) communicative StuFu, (2) artistic StuFu, and (3) reflexive StuFu, and four focus areas: (a) reflection about science, (b) self and personality development, (d) resource art, and (d) critical contemporaneity (Witten/Herdecke University, 2025a). Topics range from discussions of short stories, the orchestra, and introductory courses in civil and criminal law to offerings on the food supply of the future, and include teaching opportunities such as project work, working with texts, or lectures. Students need to study ten percent of the curriculum to experience new ways of thinking and content in heterogeneous StuFu courses that span programs and semesters (Butzlaff et al., 2014; Ehlers et al., 2019). Interprofessional courses, as well as the orientation of psychology and medicine towards problem-oriented learning and the examination procedure of the Objective Structured Clinical Examination, should additionally encourage students to think in a networked way (Bahmann et al., 2014; Frost et al., 2019; Heinke et al., 2013; Zupanic et al., 2020a). In the context of the medical curriculum, there is also an increased focus on the development of personality (Kiessling et al., 2021; Zupanic et al., 2020b).

In the present study, students at UW/H taking part in the StuFu course “Human–Animal Studies” (HAS) in the winter semester of 2021/2022 were asked about their environmental awareness and behavior, as well as performing related assessments and impressions.

1.3. Study Aim and Research Questions

The objective of this study was to evaluate the specific impact of the HAS StuFu course on students’ environmental awareness and behavior. To this end, a comparison was made between students who had participated in the course and the broader student body of an already environmentally conscious university. The goal of this comparison was to determine whether the course made a measurable difference over and above the university’s general efforts to promote sustainability and raise environmental awareness. In both groups of students, the sample included individuals from different majors, faculties, and semesters in order to focus on the hidden curriculum.

In order to investigate how environmental awareness and behavior can be expressed in a particular setting such as UW/H, and how a one-semester course can influence some of the students, the following research questions will be explored in this study:

- How strong is the expression of environmental awareness and environmental behavior among students at UW/H?

- Does this differ from people who have been offered a place on the HAS course?

- What changes are evident regarding environmental awareness and environmental behavior over a semester in the participants of the StuFu-course HAS?

- How do students from the StuFu-course HAS reflect on the expression of and/or possible changes in their environmental awareness and environmental behavior?

2. Materials and Methods

The course cohort met weekly as an online group (via Zoom), and was offered for a second time (Busse et al., 2022). Five lecturers from the fields of psychology, veterinary medicine, health sciences, and cognitive and media sciences offered the course. A small group of students (n = 23) discussed and worked on various topics related to the relationship between humans and animals. Students were free to register for the course according to their interests. Only 25 places were available. Admission was based on registration and a waiting list. In the first session, topic choices were recorded. The students were allowed to choose the topics themselves. These were topics that concerned them in their daily lives or that they had heard about before and wanted to explore in more depth. The whole group had their topics collected, which were written on cards and collected on a metaplan wall. Small groups were then formed, each working on one topic and preparing it for one of the following days of the course. The requirements were to work scientifically and to present the topic in a varied didactic way. Each session should include a round table discussion with all participants (students and faculty). One person from the teaching team supervised each group of students per topic. The individual meetings during the semester proceeded in much the same way. First, the group presented its topic and a rough overview, and then individual facts were presented and discussed repeatedly with the whole group. The presenting group also prepared discussion questions. At the end of the session, there was always a discussion with the whole group. This was also used to discuss what the topic had meant to them and whether there were any lessons to be learned for their own actions.

In the final session of the course, the reflective writing methodology was used and explained to all participants. To ensure that everyone understood the reflective writing method in the same way, there was a 10 min introduction to the method, including an example video with detailed explanations. They were then given 15 min to write about the course and what it had done for them. Emphasis was placed on the participants’ personal perceptions and the subsequent impact on their actions. These reflections were collected anonymously in an online document https://edupad.ch (accessed on 17 May 2025). The collected reflections were subjected to qualitative content analysis by two independent researchers to develop a category system. The first, second, and last sessions were organized by the lecturers. An overview of the topics can be found in the Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Topics of the course “Human–Animal-Studies” in winter 21/22 (chosen by the students).

In order to compare the effects of the StuFu course on the students in the course with the students of the university, a survey was conducted. First, people who had participated in the StuFu course were included in the survey, and then the rest of the university’s student body was also asked to complete the slightly adapted survey.

In the winter semester of 2021/22, two different online surveys were conducted at UW/H via Lime Survey https://limesurvey.uni-wh.de/ (accessed on 17 May 2025) using the same “Short Survey on Environmental Awareness and Behavior” questionnaire. The questionnaire was developed and compiled specifically for this study and consists of twelve questions to be answered on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The subscale “environmental awareness” consists of six questions (questions 1–6), three conative and three cognitive. The environmental behavior subscale consists of five questions (questions 7–11). The last open question (question 12) concerns both areas (see Table 2), which were analyzed using a summary qualitative content analysis (Mayring, 2019).

Table 2.

Short survey on environmental awareness and behavior (12 Items).

The questionnaire was administered at three different times during the StuFu course (at the beginning of the course, in the middle of the course, and at the end of the course). To ensure that everyone had enough time to complete the survey, the students were given time to complete the survey during each session of the StuFu course (at the beginning or end of the session). In order to be able to compare the data from the longitudinal surveys, participants were asked to enter a “mother code” in each questionnaire (mother’s month of birth + first two letters of mother’s maiden name, e.g., 04BE). All students were surveyed only once (in parallel with the course completion survey). The original questionnaire was written in German. One researcher (J.N.) translated it into English for this publication, and another independent member of the team (P.T.), who was not familiar with the questionnaire, translated it back into German. This German translation was then compared with the original, and the English translation of the original was again revised in discussion between J.N. and P.T.

3. Results

Due to the anonymized collection, an ethics vote was not necessary, and data protection compliance was maintained and clarified with the data protection officer. The data are held by the authors and can be made available in anonymized form upon reasonable request. Both the qualitative and quantitative surveys are based on self-assessments and self-reported information provided by the participants.

3.1. Longitudinal Survey in the StuFu

The “Short Survey on Environmental Awareness and Behavior—StuFu” was conducted online via Lime Survey as part of the HAS course in the winter semester of 2021/22 (released 21 October 2021–27 January 2022). In total, 80 questionnaires were administered, 74 of which were completed. The longitudinal analysis was conducted over at least three participations, so that for the analyses at T1 on 21 October 2021, 32 persons (24 female, 8 male) with a mean age of 24.5 ± 3.75 years were available. At T2 (period 25 November–2 December 2021) there were 11 completed questionnaires, and at T3 (period 20 January 2021–27 January 2022) there were 14 completed questionnaires. At the end of the course, 22 participants received certificates of participation; at the beginning of the course, there were 32 participants. The results of the descriptive analyses are shown in Table 3. The examination of possible longitudinal changes with non-parametric Wilcoxon tests did not reveal any significant differences at the three time points (T1–T3) (Döring et al., 2016).

Correlation analyses showed significant correlations between age and individual items of the Short-Form Questionnaire with positive proportionality at T1, for environmental awareness with item 1 (r = 0.571, p < 0.001), and the sum of the subscale (r = 0.495, p = 0.004), and for environmental behavior with items 9 (r = 0.377, p = 0.033) and 10 (r = 0.516, p = 0.002), and the sum of the subscale (r = 0.499, p = 0.004). The total sum of the short questionnaire also correlates significantly with age (r = 0.570, p < 0.001).

Significant gender differences were found at T1 in item 3 (U = 49, p = 0.034) and item 5 (U = 40, p = 0.013) on environmental awareness. Women expressed lower agreement with item 3 and higher agreement with item 5 than men.

3.2. Open-Ended Question in the StuFu

The summary qualitative content analysis (Mayring, 2019) of the responses to the open-ended question (item 12) was conducted with the statements at time points T1–T3 (total N = 47) (Mayring, 2019). The participants expressed up to eight mentions, on average 2.56 ± 1.72. Two independent coders (M.Z., J.E.) successively performed the content analysis with subsequent discussion and reflection of the categories to ensure intersubjective comprehensibility (Kuckartz & Rädiker, 2022). The resulting seven categories are listed in the Appendix A as a complete category system with the frequency of mention, the definition, and an anchor example (see Appendix A Table A1). In order to ensure the anonymity of the participants, no information on gender, course of study, etc., is provided with the quotations. Only the code for the authors’ traceability is given.

The most mentions are found in the category Everyday actions reflecting individual behavior (#16 mentions), followed by environmental concerns like Climate crisis (#15), nutrition (#12) and political actions (#12). The remaining three categories are Sustainable action (#7), Education (#4), and Other (#2). The categories illustrate that humanity’s social and political actions are being addressed, as well as individual contributions.

The following example is a typical citation for the Everyday actions category:

“The question about the moral responsibility of bringing children into the world in the current state of the earth and what can be done to leave them a healthy earth.”(Student 06BA)

And for the political actions category, the following was said:

“We are rich in science, resources and technology so that we could all be taken care of and our environmental behavior could change. How do we succeed in a COMMON and fair use of these resources?”(Student 09BE)

3.3. Reflective Writing in the StuFu

At the last event in the HAS course on 27 January 2022, a final survey was conducted using the reflective writing method (Koole et al., 2011). “My important experiences in the Human–Animal Studies course” were described by 19 participants (Edupad) and analyzed using summary qualitative content analysis. In the first pass (M.Z.), 88 codings identified eight categories (Changes, Reflections and thoughts, Topics, Impression, Perspective, Everyday life, Favorite topics, Other). In the second pass (J.E.), with 77 codings, the same eight categories were identified with satisfactory intersubjectivity. Differences were found only in the two categories Changes and Everyday Life, which could be identified in the following discussion as a temporal effect of the change in onset during the course. The complete category system with the frequency of mentions, the definition, and an anchor example can be found in Appendix A (see Table A2).

The largest number of mentions was in the category Changes, concerning new attitudes and behaviors (#26 mentions), followed by Reflections and Thoughts (#21), Topics (12), and Impressions (#10). The remaining four categories are Perspective (#7), Everyday Life, Favorite Topics, and Other (#2 mentions each). The categories illustrate that students experienced many thoughts about needed and possible changes in attitude and behavior throughout the course, as well as reflections on current behavior.

A typical example for the Changes category is the following quote:

“Because we talked about the topics at regular intervals, I regularly started thinking about my own relationship to animals and also about the general treatment of animals, which actually led me (I would have rather not thought) to a change in diet.”(Student 12RE)

For the category Topics and Information, the following was said:

“I think it’s incredibly important to keep confronting facts, as unpleasant as they are.”(Student 02GR)

And for the Impression category, the following was said:

“I was very impressed and moved by the fact that one can be so reflective, engaged, and enthusiastic about such important issues, and most importantly, that one can share this passion with others to create a more informed, environmentally conscious, and overall better future.”(Student 02ST)

3.4. Cross-Sectional Survey at the UW/H

The “Short survey on Environmental Awareness and Behavior—UW/H” was also conducted via Lime Survey, released online from 20 January to 1 March 2022. In total, 365 questionnaires were filled out, of which 327 were completed. The participants (195 female, 112 male, 3 ambiguous, 17 without gender) with a mean age of 25.32 ± 5.12 years (minimum 17, maximum 61 years) studied in the 4.73 ± 3.28 semester at the Faculty of Health (N = 264, 80.7%) or the Faculty of Economics and Society (N = 54, 16.5%).

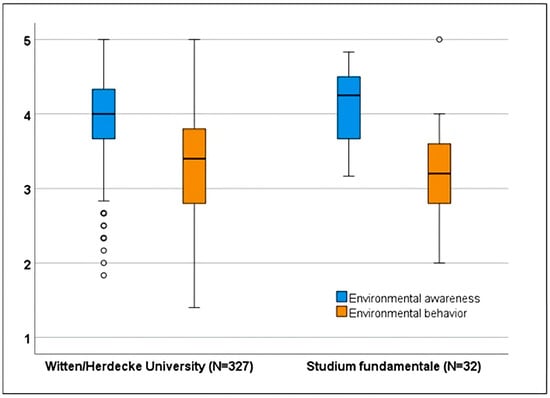

The analysis of variance test for possible differences between faculties showed only two significant results. Students from the Faculty of Health agreed significantly more with item 1 (4.23 ± 0.815 vs. 3.78 ± 0.925; F = 13.216, p = <0.001) and item 5 (3.58 ± 1.065 vs. 3.11 ± 1.192; F = 8.458, p = 0.004) than students from the Faculty of Business and Society. Analysis of variance with the grouping factor gender (female vs. male) showed significant differences in almost all items and scales (see Table 4). The largest difference is seen in item 5, “Animals should have similar life rights as humans”, with significantly greater agreement from females compared to males. The Kruskall-Wallis test confirmed gender differences in central tendency, with significantly higher environmental awareness (H = 20.95, p < 0.001) and environmental activity (H = 11.47, p < 0.003) among those gender divers (see Figure 1).

Table 3.

Results of the short survey at the three data collection periods (mean values, standard deviations).

Table 3.

Results of the short survey at the three data collection periods (mean values, standard deviations).

| T1 (N = 32) Mean | T1 (N = 32) Sd | T2 (N = 11) Mean | T2 (N = 11) Sd | T3 (N = 14) Mean | T3 (N = 14) Sd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. For the sake of the environment, we should all be willing to limit our current standard of living. | 4.31 | 0.738 | 40.45 | 0.688 | 40.50 | 0.941 |

| 2. Science and technology will solve many environmental problems without requiring us to change our lifestyles. | 2.25 | 0.762 | 20.09 | 0.701 | 20.00 | 0.679 |

| 3. Environmental protection measures should be enforced even if jobs are lost as a result. | 3.56 | 10.05 | 30.45 | 10.214 | 30.71 | 0.994 |

| 4. The impact of the climate crisis is overestimated by multimedia reporting. | 1.63 | 0.907 | 10.36 | 0.924 | 10.43 | 0.646 |

| 5. Animals should have similar life rights as humans. | 3.84 | 10.14 | 40.00 | 0.894 | 30.71 | 10.326 |

| 6. I am concerned about ecological conditions on Earth. | 4.62 | 0.554 | 40.64 | 0.674 | 40.64 | 0.842 |

| 7. I discuss issues with friends and acquaintances that are also covered in the StuFu Human–Animal Relations course. | 3.94 | 0.878 | 30.91 | 0.944 | 40.00 | 10.301 |

| 8. I eat in a climate-conscious way. | 3.31 | 0.780 | 30.64 | 0.809 | 30.29 | 0.825 |

| 9. I consciously travel by bicycle or public transport instead of by car. | 3.22 | 10.289 | 30.73 | 10.191 | 30.57 | 10.453 |

| 10. I use energy from renewable sources, e.g., by choosing my electricity supplier. | 3.53 | 10.191 | 30.55 | 10.293 | 30.71 | 10.267 |

| 11. I am actively involved in climate protection, e.g., in a Campus for Future activist group. | 2.09 | 10.279 | 20.55 | 10.440 | 20.50 | 10.557 |

| Environmental awareness (Items 1–6) | 3.37 | 00.45 | 30.33 | 0.40139 | 30.333 | 0.453 |

| Environmental behavior (Items 7–11) | 3.22 | 0.639 | 30.47 | 0.73904 | 30.41 | 0.839 |

| Total | 3.29 | 0.476 | 30.40 | 0.47626 | 30.37 | 0.549 |

Table 4.

Results of the short cross-sectional survey (means, standard deviations, ANOVA: F-values, p-values).

Table 4.

Results of the short cross-sectional survey (means, standard deviations, ANOVA: F-values, p-values).

| Female (N = 195) Mean | Female (N = 195) Sd | Male (N = 112) Mean | Male (N = 112) Sd | F-Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. For the sake of the environment, we should all be willing to limit our current standard of living. | 4.25 | 0.781 | 3.94 | 0.971 | 9.280 | 0.003 |

| 2. Science and technology will solve many environmental problems without requiring us to change our lifestyles. | 2.36 | 0.803 | 2.71 | 1.061 | 10.643 | 0.001 |

| 3. Environmental protection measures should be enforced even if jobs are lost as a result. | 3.77 | 0.788 | 3.71 | 1.043 | 0.271 | 0.603 |

| 4. The impact of the climate crisis is overestimated by multimedia reporting. | 1.55 | 1.056 | 1.86 | 1.073 | 6.000 | 0.015 |

| 5. Animals should have similar life rights as humans. | 3.77 | 0.991 | 3.01 | 1.119 | 38.053 | <0.001 |

| 6. I am concerned about ecological conditions on Earth. | 4.61 | 0.690 | 4.43 | 0.791 | 4.426 | 0.036 |

| 7. I discuss issues with friends and acquaintances that are also covered in the StuFu Human–Animal Relations course. | 3.65 | 1.061 | 3.21 | 1.116 | 12.100 | <0.001 |

| 8. I eat in a climate-conscious way. | 3.73 | 0.845 | 3.46 | 0.939 | 6.392 | 0.012 |

| 9. I consciously travel by bicycle or public transport instead of by car. | 3.71 | 1.231 | 3.46 | 1.368 | 2.867 | 0.091 |

| 10. I use energy from renewable sources, e.g., by choosing my electricity supplier. | 3.74 | 1.225 | 3.62 | 1.441 | 0.676 | 0.411 |

| 11. I am actively involved in climate protection, e.g., in a Campus for Future activist group. | 2.10 | 1.158 | 1.83 | 0.985 | 4.372 | 0.037 |

| Environmental awareness (Items 1–6) | 3.3846 | 0.37641 | 3.2768 | 0.38526 | 5.739 | 0.017 |

| Environmental behavior (Items 7–11) | 3.3877 | 0.71151 | 3.1143 | 0.76534 | 9.937 | 0.002 |

| Total | 3.3862 | 0.44123 | 3.1955 | 0.48709 | 12.299 | <0.001 |

Figure 1.

Boxplots of total values in the subscales environmental awareness (blue) and environmental behavior (orange) for the gender divers (N = 3), male (N = 112) and female participants (N = 195).

3.5. Open-Ended Question at the UW/H

In total, 321 students (87.94%) answered the last open-ended question (item 12) of the questionnaire. Two independent coders (T.B., J.N.) successively performed the content analysis with subsequent discussion and reflection of the categories to ensure intersubjective comprehensibility (Kuckartz & Rädiker, 2022).

The total of 513 codings were divided with regard to their content orientation into (a) mentions with a problem focus and (b) mentions with a solution approach into the main categories problem focus (#317 mentions) and Solution approach (#181 mentions), as well as three other not-assignable categories (#7 Dealing with effects of climate catastrophe, #7 No personal relevance of the topic, #1 Wrong information).

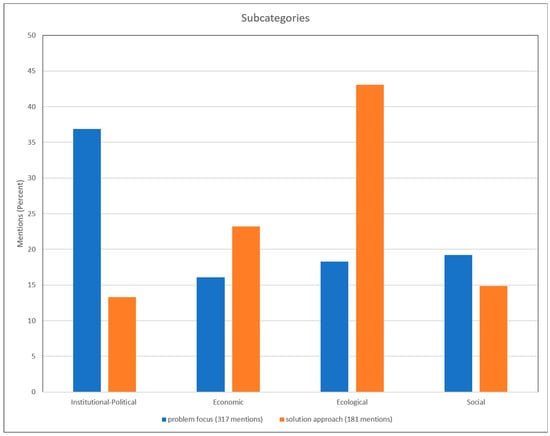

The categories problem focus and solution approach were subdivided into the following dimensions (see Figure 2):

Figure 2.

Mentions in the four subscales of the main, categories problem focus (blue) and solution approach (orange), in percentages based on the respective main category.

The institutional–political dimension, with 117 mentions in 7 subcategories, respectively, and 24 mentions in 3 subcategories;

The economic dimension, with 51 mentions in 7 subcategories, respectively, and 42 mentions in 6 subcategories;

The ecological dimension, with 58 mentions in 8 subcategories, respectively, and 78 mentions in 5 subcategories;

The social dimension, with 61 mentions in 4 subcategories, respectively, and 27 mentions in 5 subcategories.

The main category problem focus also includes the category overall situation (#30), which includes all statements that name a global difficult situation and evaluate it as problematic. The solution approach additionally includes a general category (#10).

Again, only the students’ numerical codes are shown to protect their anonymity.

The percentages in Figure 2 illustrate that, from the students’ point of view, the problems are mainly in the institutional-political and social domains, while the solutions are to be found in the economic and ecological domains.

The following is a typical example for the industrial–political domain with problem focus states:

“At the climate conference in Paris, all countries agreed that there should never be 5 degrees of warming because of the catastrophic effects. However, there were some countries that would be interested in a warming around 3 degrees, because on the one hand the Northern Passage would become free for shipping (extremely much faster than the Southern Passage) and on the other hand the melting of the permafrost would turn gigantic parts of the world’s land mass (of which a lot lies very north) into usable arable land in Alaska, Canada and Russia. I believe it can never be kept to 1.5 degrees or even 2 degrees as long as such geopolitical interests stand against it in real terms.”(Student 316)

For the social domain with problem focus, the following was said:

“The ignorance of the masses that environmental protection is currently an elite issue. The fact that social and educational justice must first be created in order to expect sustainable behavior from all people. That we have no more time, but scientists continue to be ignored. The emptying of the oceans.”(Student 219)

A typical example for the ecological domain with solution approach is the following quote:

“How we manage to become climate neutral within the next 8 years, when there is so much headwind and many complain about the high costs, but do not see that no climate protection is so much more expensive. We need new narratives, from renunciation to gain for the environment and for our quality of life and our health.”(Student 154)

And for the economical domain, the following quote is a typical example:

“How can we build a circular economy and make, use, plan things in a way that can be reused.”(Student 195)

3.6. Mixed Methods Results Comparison

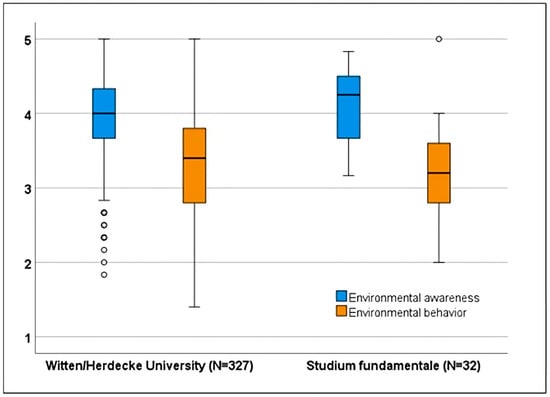

Comparing the quantitative results of the online questionnaire between the students at HAS (N = 32 at T1; see Table 2) and the survey at UW/H (N = 327; see Table 3), there are no significant differences. Both groups show similar environmental awareness and environmental behavior. The total values in the environmental awareness and environmental behavior subscales are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Boxplots of total values in the subscales environmental awareness (blue) and environmental behavior (orange) for the groups HAS (N = 32) and Witten/Herdecke University (N = 327).

Within each group and between the two groups, the quantitative results are compared with the results of the qualitative content analysis of the last open-ended question. In the HAS group (N = 32), there is not only a high level of environmental awareness, but also equally pronounced environmental behavior (see Table 2). This is reflected in the categories of the qualitative results, which show a broad approach ranging from individual behavior to industrial–political action (see Appendix A Table A1). The category system of the reflective writing format clearly shows the impact of the prompt “My important experiences in the Human–Animal Studies course” (see Appendix A Table A2). Thoughts and reflections related to changes in attitudes and behaviors are reported with priority. Therefore, for this group, the quantitative and qualitative results can be considered consistent.

The UW/H group (N = 327) also shows a high level of environmental awareness and behavior (see Table 2). The category system reveals the differentiated approach, resulting in equally relevant dimensions with a problem focus and solution approaches (see Figure 2). The four dimensions are also found in the category system of the HAS group (see Table 1 in the attachment): political actions can be assigned to the industrial–political dimension, nutrition to the economic dimension, climate crisis and sustainable actions to the ecological dimension, and everyday actions and education to the social dimension. Therefore, the quantitative and qualitative results of this group can be considered consistent as well as the results of the two groups HAS and UW/H.

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to examine the expression of environmental consciousness and behavior among students at UW/H. Furthermore, it was also investigated how students reflect on the expression and possible changes in these aspects. To achieve this, students participating in the thematic course of StuFu on HAS were surveyed at three different measurement times (T1–T3). The longitudinal survey primarily aimed to capture possible changes in the expression of environmental awareness and behavior over the course of the semester. Additionally, a second survey aimed at all students at UW/H was conducted once; parallel to the last measurement point of the StuFu course.

In the present study, the following results were observed: In both groups, a similarly high level of environmental awareness was observed, exceeding that of the general population in Germany. While in the StuFu course and at UW/H more than one in two people stated that they have a high level of interest in environmental awareness and environmental behavior, a look at the population as a whole reveals that only less than one in five Germans are particularly interested in environmental protection and nature conservation (IfD Allensbach, 2024). The results obtained at the three measurement points in the StuFu course, as well as the one-time survey of the UW/H students, consistently demonstrated statistically moderate to high levels of environmental consciousness. Despite the similarities, there were no significant differences in the results between the HAS group and the control group of UW/H students. Similarly, environmental behavior is about the same in both groups and at a moderate level. In this regard, no significant differences were observed between the participants of HAS and the students of UW/H.

A previous study has shown that university attendance is positively associated with commitment to environmental sustainability compared to other forms of full-time education (Cotton & Alcock, 2013). This explains the lack of differences between the two groups studied. In addition, another study found medium to high levels of environmental awareness. In a study of pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors in higher education, high levels of environmental concern were observed in more than half of the participants (Pizmony-Levy & Ostrow Michel, 2018). Again, hearing about environmentalism and sustainability in the classroom and being involved in campus environmental groups were found to have positive and significant effects on levels of environmental awareness and behavior. These findings are of particular importance with regard to the StuFu course and the hidden curriculum at UW/H. The present findings underscore the importance of placing greater emphasis on affective and behavioral learning goals, in addition to cognitive ones, in higher education pedagogy. Of particular interest here is the form of the hidden curriculum, where teachers are aware of the invisible learning content, but learners are not. In particular, higher education should aim to develop students’ moral agency—a goal that is becoming increasingly urgent in the context of the climate crisis and planetary boundaries (Bernhardt, 2022).

Although there are no significant differences between the participants in the HAS and the UW/H students, observable gender distinctions can be found among the group of all UW/H students. It is noticeable that female participants in the UW/H generally showed a higher level of environmental awareness and environmental behavior than male participants. Regarding the gender differences in the UW/H group, previous animal welfare studies support the results of the present study. On average, women are generally more empathetic to their fellow humans and animals than men, and show higher levels of overall environmental sensitivity (Duman-Yuksel & Ozkazanc, 2015; Graça et al., 2018). Yapici et al. (2017) further state that women, compared to men, not only have a more open attitude towards environmental aspects, but also a higher level of risk perception, which they justify by a generally higher level of concern for health and safety among women (Yapici et al., 2017).

Beyond these differences, the results of the reflective writing process show that students have given thought to necessary changes in their own awareness and behavior towards the environment because of the StuFu course. The participants stated that they had reconsidered their own attitudes towards the environment and their relationship with animals, which could ultimately lead to a change in their own way of living and thinking. Therefore, it can be observed that the course has brought about a change in the environmental awareness and behavior of many participating students. The correlation identified here is further substantiated by findings from a preceding investigation on the environmental attitudes and pro-environmental behaviors of university students (Janmaimool & Khajohnmanee, 2019). This study revealed a noteworthy elevation in environmental awareness among students who enrolled in an elective course titled ‘Environment and Development’ as compared to those who did not participate in the course. Despite the lack of significant differences between the two groups in the quantitative results, the qualitative data from the reflective writing processes provide a meaningful complement and depth to the analysis. The participants’ statements show that the course provided an impetus for intensive personal engagement with environmental and animal ethics. They often reflected on their own consumer behavior, their use of resources, and their emotional relationship to animals. This individual reflection cannot necessarily be captured in standardized scales, but it is an essential part of the learning process. The qualitative depth of these reflections points to the processes of examining and changing attitudes that may lead to an inner attitude that makes more environmentally conscious behavior more likely in the long run.

A possible explanation for the high level of environmental awareness and behavior in both groups compared to the rest of the German population is provided by a look at the hidden curricula in higher education contexts and especially at UW/H. The admission procedure for students at UW/H generally involves a formal written application, which may be followed by a personal selection interview regarding the applicant’s personality and associated values and attitudes (Witten/Herdecke University, 2024a). The aim of the process is to assess whether the applicant has the basic prerequisites to act responsibly, sustainably, socially, and reflectively in future professional fields. It can therefore be assumed that students have already reflected on and dealt with this topic to a high degree in advance (Goos & Salomons, 2017; Wolbring & Treischl, 2016). The participants of the previous StuFu course on the same topic also showed a high level of interest over the duration of the course and dealt intensively with sources, studies, and data on the specific topics in preparation for the individual sessions (Busse et al., 2022). This cannot be taken for granted, especially in view of the purely digital implementation of the course.

These aspects also indicate that there were no changes in environmental awareness and behavior across the three measurement points. It can be assumed that students who enrolled in the HAS out of their own interest already had a high level of awareness of environmental issues, which did not change significantly over the course of the course.

There are several limitations to this study that have implications for future research. The selective process at UW/H emerges as a limiting factor affecting the generalizability of the results. As a result, it is not tenable to assert that such heightened environmental awareness and behavior are present at other German universities. Despite the absence of current comparative studies examining environmentally related behaviors among students across different universities, it is significant for future research to explore whether hidden curricula are also established elsewhere. It would therefore be of particular interest to investigate whether a StuFu course would have produced the same results at other universities whose institutional philosophy is not based on such a socially oriented and sustainable profile. This research is critical for a more nuanced understanding of the issue and to determine the broader applicability of the findings beyond the specific context of UW/H.

For comparison, a qualitative extension of the control group survey by means of reflective writing would be of particular importance to determine whether the HAS has had a significant impact on students’ environmental awareness.

In order to validate the effectiveness of course formats such as HAS beyond UW/H, pilot projects could be initiated at universities with a less pronounced sustainability profile. In particular, the transferability of reflective writing, interdisciplinary discourse formats, and the focused discussion of HAS should be explored. Such a transfer approach could contribute to the establishment of similar didactic formats at technically or economically oriented universities.

Compared to the hidden curricula, there is currently no official consideration of environmental awareness and behavior in the official curricula. In order to establish the philosophy of UW/H and to promote environmentally conscious thinking and acting in university and professional contexts, a future integration of this content into the study regulations would be of great importance (Hafferty & Franks, 1994; Straßer et al., 2023). This suggests that educational content needs to be modified in the context of future-oriented and progressive thinking and action, not only at the UW/H, but also at other universities.

Student interest in the courses remains very high. Overall, it can be stated for UW/H that the StuFu course HAS integrates seamlessly into an existing series of courses on sustainability and environmental awareness. This includes courses like “Digital Medicine goes Planetary Health” or “Gaming against the Climate Crisis” as well as a planned digital and open lecture HAS series for the winter semester of 2024/2025. At this point, reference can also be made to the book ‘Human–animal relationship—results and positions from a student course’ (‘Mensch-Tier-Verhältnis—Ergebnisse und Positionen aus einem studentischen Kurs’) by Busse et al. (2022), which was produced on the basis of a StuFu course that thematized the human–animal relationship and took place in the summer semester of 2021. Thus, at UW/H, a hidden curriculum can be discussed not only in a structural sense with measures already established on campus, but also in terms of an expanding discontinuous curriculum in teaching, which is urgently needed for the development of students’ personalities with regard to ethical behavior in general and environmentally friendly behavior in particular.

The methods used in the StuFu course—especially reflective writing and emotional engagement with environmental and animal ethics—could also be effective in upper secondary or vocational schools. The introduction of low-threshold formats such as project weeks or elective courses with a focus on environmental ethics would be a first step towards promoting early ecological reflection skills.

5. Conclusions

The integration of the HAS course into UW/H’s sustainability-focused curriculum highlights the university’s commitment to fostering environmental awareness and ethical reflection among students. This growing curriculum, both structured and evolving, plays a crucial role in shaping students’ ethical perspectives and promoting sustainable behavior.

Author Contributions

J.N., T.S.B., P.-D.T. and J.P.E. conceived the ideas and designed methodology; J.N., T.S.B., M.S. and J.P.E. carried out the intervention J.N. and T.S.B. collected the data; J.N., T.S.B., M.S. and J.P.E. analyzed the data; J.N. and M.S. led the writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed critically to the drafts and gave final approval for publication. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the anonymized collection and data protection compliance was maintained and clarified with the data protection officer.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting this study as supplementary information are archived by and can be requested from the corresponding author (julia.nitsche@uni-wh.de).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UW/H | Witten/Herdecke University |

| HAS | Human–Animal Studies |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Results of the qualitative content analysis of answers to the open question (N = 47 with a total of 66 mentions).

Table A1.

Results of the qualitative content analysis of answers to the open question (N = 47 with a total of 66 mentions).

| Codes | Definition | Anchor Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|

| K3 | Everyday actions (N = 16) | Individual behavior | I am mainly concerned with the conflict between “wanting to do something” and “not restricting yourself too much”. How much restriction is the minimum and how much is enough? (06BA) |

| K1 | Climate crisis (N = 15) | Environmental concerns | My concern is that humanity has virtually no time to stop the climate crisis. The opportunities are there, but there is a lack of time. (02LU) |

| K2 | Nutrition (N = 12) | Food production | Consumer behavior, especially the food industry … (03DR) |

| K4 | Political actions (N = 12) | Decisions | Political decisions and their impacts. Global interaction of countries on climate issues. (07EB) |

| K5 | Sustainable action (N = 7) | Conservation | Sustainability. Can our planet “survive”. Future and no planet B. (01ST) |

| K6 | Education (N = 4) | Campaigns | I am concerned that so many people do NOT believe the numbers and data of science and think they know better themselves. That they rest on it, that currently “nothing bad happens”. But what it does. (01MI) |

| K7 | Other (N = 2) | Displeasure | The unreasonableness of people. (09HE) |

Table A2.

Results of the qualitative content analysis of essays in the reflective writing format (N = 19).

Table A2.

Results of the qualitative content analysis of essays in the reflective writing format (N = 19).

| Codes | Definition | Anchor Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|

| K1 | Reflections (N = 21) | Thought and reflection | Because we talked about the topics at regular intervals, I also regularly got to thinking about my own relationship with animals and also about the general treatment of animals, … (12RE) |

| K2 | Topics (N = 15) | Themes and information | I think it’s incredibly important to keep confronting facts, as unpleasant as they are. (02GR) |

| K3 | Everyday life (N = 2) | Infiltration as an everyday presence | However, the fact that they often fare badly in the process and are kept “effectively” for economic reasons will have a lasting effect on my view of my personal meat consumption. (10HU) |

| K4 | Changes (N = 26) | New attitudes and behaviors | It was made clear to me once again that one should distance oneself from these power relationships and rather put the aspect of living together in the foreground, be it in the keeping of farm animals or also pets. (11KR) |

| K5 | Perspectives (N= 7) | Academic discourse | The most important insight here was the extreme diversity of dealing with different animals. (11SC) |

| K6 | Favorite topics (N = 2) | Salient themes | However, I noticed perspectives/attitudes that were not illuminated. For example, I wondered if the only distinction between humans and animals is not that humans make a distinction at all. (06KA) |

| K7 | Impression (N = 10) | What remains? | I was very impressed and moved by the fact that one can be so reflective, engaged, and enthusiastic about such important issues, and most importantly, that one can share this passion with others to create a more informed, environmentally conscious, and overall better future. (02ST) |

| K8 | Other (N = 2) | No assignment yet | I would say that I have been involved with animals for a very long time because I grew up with them and they are just part of the family in our house. (02RO) |

References

- Altenbuchner, C., & Tunst-Kamleitner, U. (2019). Soziologie des umweltverhaltens. In E. Schmid, & T. Pröll (Eds.), Umwelt- und Bioressourcenmanagement für eine nachhaltige Zukunftsgestaltung (pp. 73–80). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Andarvazh, M. R., Afshar, L., & Yazdani, S. (2017). Hidden curriculum: An analytical definition. Journal of Medical Education, 16(4), 198–207. [Google Scholar]

- Bahmann, L. F., Mennen, C., Ridder, L., & Zupanic, M. (2014). POL—Mit praxisnahen problemen psychologie lernen. PsychOpen GOLD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhardt, P. E. (2022). Hidden curriculum: Definitions and examples. In Hidden curriculum: Definitions and examples. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, T. S., Ehlers, J. P., Kochanek, T., Nitsche, J., Zupanic, M., Brétéché, M., Drückler, Z. A., Akar, Z., Shwa, S., Ohm, H., Johanni, S., Bunkus, J. N., Güth, L., Göcking, F., Stoll, F., Breuer, S., Scott, L.-C., & Röhlig, A. (2022). Mensch-Tier-Verhältnis—Ergebnisse und positionen aus einem studentischen Kurs. Zenodo. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butzlaff, M., Hofmann, M., Edelhäuser, F., Scheffer, C., Tauschel, D., Lutz, G., Wirth, D., Reißenweber, J., Brunk, C., Thiele, S., & Zupanic, M. (2014). Der modellstudiengang medizin an der universität witten/herdecke—Auf dem weg zur lebenslang lernfähigen arztpersönlichkeit. In W. Benz, J. Kohler, & K. Landfried (Eds.), Handbuch qualität in studium und lehre (1st ed., pp. 65–103). Raabe—Fachverlag für Wissenschaftsinformation. [Google Scholar]

- Chrubasik, N., & Fink, J. (2018). Das Projektstudium “Lehre für eine nachhaltige universität” an der Universität Kassel—Eine interdisziplinäre lehr- und lernmethode zum themenkomplex nachhaltigkeit an der hochschule. In W. Leal Filho (Ed.), Theorie und praxis der nachhaltigkeit. nachhaltigkeit in der lehre: Eine herausforderung für hochschulen (1st ed., pp. 441–448). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, D. R., & Alcock, I. (2013). Commitment to environmental sustainability in the UK student population. Studies in Higher Education, 38(10), 1457–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döring, N., Bortz, J., Pöschl-Günther, S., Werner, C. S., Schermelleh-Engel, K., Gerhard, C., & Gäde, J. C. (2016). Forschungsmethoden und evaluation in den sozial- und humanwissenschaften (5. Aufl. 2016). In Springer-lehrbuch. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman-Yuksel, U., & Ozkazanc, S. (2015). Investigation of the environmental attitudes and approaches of university students’. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 197, 2191–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ehlers, J. P., Herrmann, M., Mondritzki, T., Truebel, H., & Boehme, P. (2019). Digital transformation of medicine—Experiences with a course to prepare students to seize opportunities and minimize risks. German Medical Science: GMS e-Journal, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, D., Bürgle, N., & Uemminghaus, M. (2021). Eine vision exzellenter lehre: 11 anforderungen an dozierende. In D. Frey, & M. Uemminghaus (Eds.), Innovative lehre an der hochschule: Konzepte, praxisbeispiele und lernerfahrungen aus COVID-19 (pp. 17–30). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, K., Edelhäuser, F., Hofmann, M., Tauschel, D., & Lutz, G. (2019). History and development of medical studies at the University of Witten/Herdecke—An example of “continuous reform”. GMS Journal for Medical Education, 36(5), Doc61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, B. (2018). Seminarkonzept: “Nachhaltigkeit natürlich erleben” (Universität Hamburg). In W. Leal Filho (Ed.), Theorie und praxis der nachhaltigkeit. Nachhaltigkeit in der lehre: Eine herausforderung für hochschulen (1st ed., pp. 313–325). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. [Google Scholar]

- Goos, M., & Salomons, A. (2017). Measuring teaching quality in higher education: Assessing selection bias in course evaluations. Research in Higher Education, 58(4), 341–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, J., Calheiros, M. M., Oliveira, A., & Milfont, T. L. (2018). Why are women less likely to support animal exploitation than men? The mediating roles of social dominance orientation and empathy. Personality and Individual Differences, 129, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafferty, F. W., & Franks, R. (1994). The hidden curriculum, ethics teaching, and the structure of medical education. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 69(11), 861–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinke, W., Rotzoll, D., Hempel, G., Zupanic, M., Stumpp, P., Kaisers, U. X., & Fischer, M. R. (2013). Students benefit from developing their own emergency medicine OSCE stations: A comparative study using the matched-pair method. BMC Medical Education, 13, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IfD Allensbach. (2024). Interesse der bevölkerung in deutschland an natur- und umweltschutz von 2019 bis 2024. Personen in Millionen [Graph]. Available online: https://de-statista-com.uni-wh.idm.oclc.org/statistik/daten/studie/170945/umfrage/interesse-an-naturschutz-und-umweltschutz/ (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Janmaimool, P., & Khajohnmanee, S. (2019). Roles of environmental system knowledge in promoting university students’ environmental attitudes and pro-environmental behaviors. Sustainability, 11(16), 4270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A. (2022). The health impacts of climate change: Why climate action is essential to protect health. Orthopaedics and Trauma, 36(5), 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiessling, C., Mennigen, F., Schulte, H., Schwarz, L., & Lutz, G. (2021). Communicative competencies anchored longitudinally—The curriculum “personal and professional development” in the model study programme in undergraduate medical education at the University of Witten/Herdecke. GMS Journal for Medical Education, 38(3), Doc57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koole, S., Dornan, T., Aper, L., Scherpbier, A., Valcke, M., Cohen-Schotanus, J., & Derese, A. (2011). Factors confounding the assessment of reflection: A critical review. BMC Medical Education, 11, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuckartz, U., & Rädiker, S. (2022). Qualitative inhaltsanalyse: Methoden, praxis, computerunterstützung: Grundlagentexte methoden (5. Auflage). In Grundlagentexte methoden. Beltz Juventa. Available online: https://www.beltz.de/fileadmin/beltz/leseproben/978-3-7799-6231-1.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Lawrence, C., Mhlaba, T., Stewart, K. A., Moletsane, R., Gaede, B., & Moshabela, M. (2018). The hidden curricula of medical education: A scoping review. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 93(4), 648–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, P. (2019). Qualitative inhaltsanalyse—Abgrenzungen, spielarten, weiterentwicklungen. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 20, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, H. (1988). Unterrichtsmethoden. Cornelsen. [Google Scholar]

- Pizmony-Levy, O., & Ostrow Michel, J. (2018). Pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors in higher education: Investigating the role of formal and informal factors. International and Comparative Education, 1–39. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:52082970 (accessed on 17 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Preisendörfer, P. (1998). Themenfelder von befragungsstudien zu umwelteinstellungen und zum umweltverhalten in der bevölkerung. In J. Schupp, & G. Wagner (Eds.), Umwelt und empirische sozial- und wirtschaftsforschung (pp. 27–44). Duncker und Humblot. [Google Scholar]

- Rossa-Roccor, V., Giang, A., & Kershaw, P. (2021). Framing climate change as a human health issue: Enough to tip the scale in climate policy? The Lancet. Planetary Health, 5(8), e553–e559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straßer, P., Kühl, M., & Kühl, S. J. (2023). A hidden curriculum for environmental topics in medical education: Impact on environmental knowledge and awareness of the students. GMS Journal for Medical Education, 40(3), Doc27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. (2025). Sustainable development goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Wingerter, C. (2001). Allgemeines Umweltbewusstsein. In Zusammenstellung sozialwissenschaftlicher Items und Skalen (ZIS) GESIS 2001. GESIS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witten/Herdecke University. (2024a). Bewerbung. Available online: www.uni-wh.de/studium/bewerbung (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Witten/Herdecke University. (2024b). Nachhaltigkeit an der Universität Witten/Herdecke. Available online: www.uni-wh.de/universitaet/mission-ziele-werte/nachhaltigkeit (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Witten/Herdecke University. (2024c). Projekt feldversuch. Available online: www.uni-wh.de/universitaet/leitbild-und-claim/nachhaltigkeit/projekt-feldversuch (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Witten/Herdecke University. (2025a, May 14). Seminare—Meine UW/H. Available online: https://meine-uwh.de/seminare/ (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Witten/Herdecke University. (2025b). Universität. Available online: https://www.uni-wh.de/unser-vibe/here-we-grow (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Witten/Herdecke University. (2025c, May 14). Unser holzgebäude. Available online: https://www.uni-wh.de/euer-campus/campus-entdecken/standorte/holzgebaeude (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Wolbring, T., & Treischl, E. (2016). Selection bias in students’ evaluation of teaching: Causes of student absenteeism and its consequences for course ratings and rankings. Research in Higher Education, 57(1), 51–71. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/43920030 (accessed on 17 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Yapici, G., Ögenler, O., Kurt, A. Ö., Koçaş, F., & Şaşmaz, T. (2017). Assessment of environmental attitudes and risk perceptions among university students in Mersin, Turkey. Journal of Environmental and Public Health, 2017, 5650926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinnecker, J. (Ed.). (1975). Beltz-studienbuch: Vol. 94. Der heimliche lehrplan: Untersuchungen zum schulunterricht. Beltz Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Zupanic, M., Schlicker, A., Taetz-Harrer, A., Schulz, P., & Ehlers, J. P. (2020a). Evaluation interprofessioneller lehrveranstaltungen im modellstudiengang 2018+ der UW/H: Ein fall für zwei! In 2. Bochumer IPE gespräche: Tagung zur interprofessionellen bildung im gesundheitswesen. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339696671_Evaluation_interprofessioneller_Lehrveranstaltungen_im_Modellstudiengang_2018_der_UWH_Ein_Fall_fur_Zwei (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Zupanic, M., Schulte, H., Ehlers, J. P., Haller, J., & Kiessling, C. (2020b). Konzept zur interprofessionellen persönlichkeitsentwicklung im modellstudiengang 2018+: Auf dem Weg zu meiner beruflichen identität! In M. Krämer, J. Zumbach, & I. Deibl (Eds.), Psychologiedidaktik und evaluation XIII (Vol. 16, pp. 235–243). Shaker Verlag. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).