Online Picture Book Teaching as an Intervention to Improve Typically Developing Children’s Attitudes Toward Peers with Disabilities in General Schools

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Influence of Peers’ Attitudes Toward Children with Disabilities

1.2. Theory of Attitudes and Its Developmental Principles

1.3. Interventions to Promote Acceptance of Students with Disabilities for Peers

1.4. Online Picture Book Teaching as Intervention

1.5. The Current Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurements

Try to imagine this: One day you and your mom go to a party. Just then, one of Mom’s friends comes along with a boy/girl in a wheelchair and sits next to you. Mom says hello to the friend and introduces you and the boy/girl to each other. Then mom and the friend go to another table for a while, and it’s just you and the boy/girl in the wheelchair. If you met the above scenario, what would you do? Check the box below.

2.3. Teaching Materials and Teaching Design

2.4. Intervention

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Social Validity

“I once took her to meet a child with a disability. My child did not show fear or escape reactions. She said this is a friend from the picture book and was willing to contact the child with a disability.”(Parent 2)

“Usually, he has not really come into contact with children with disabilities, but now when he sees the blind road on the road and knows to avoid it, leaving it for those in need, which is very gratifying.”(Parent 4)

“We really neglected the education on the disability attitude in our daily life. The picture book teaching is really good, which help him know more about it. When he meets people with disabilities in street, he is not afraid and wants to help them.”(Parent 5)

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Attitudes Before the Online Picture Book Courses

3.2. Participants’ Attitudes After the Online Picture Book Courses

3.3. Comparison of Participants’ Attitudes Pre- and Post-Intervention

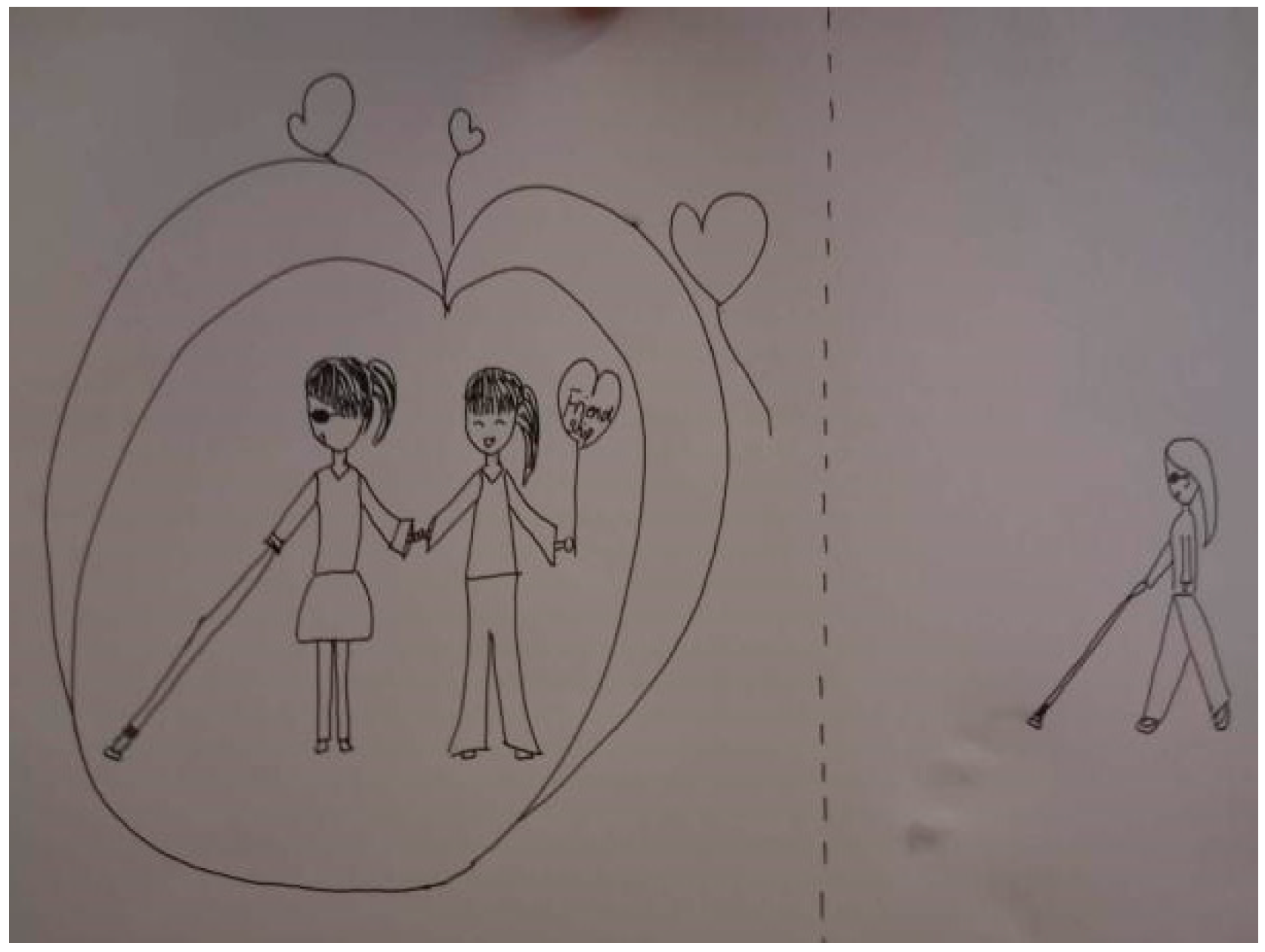

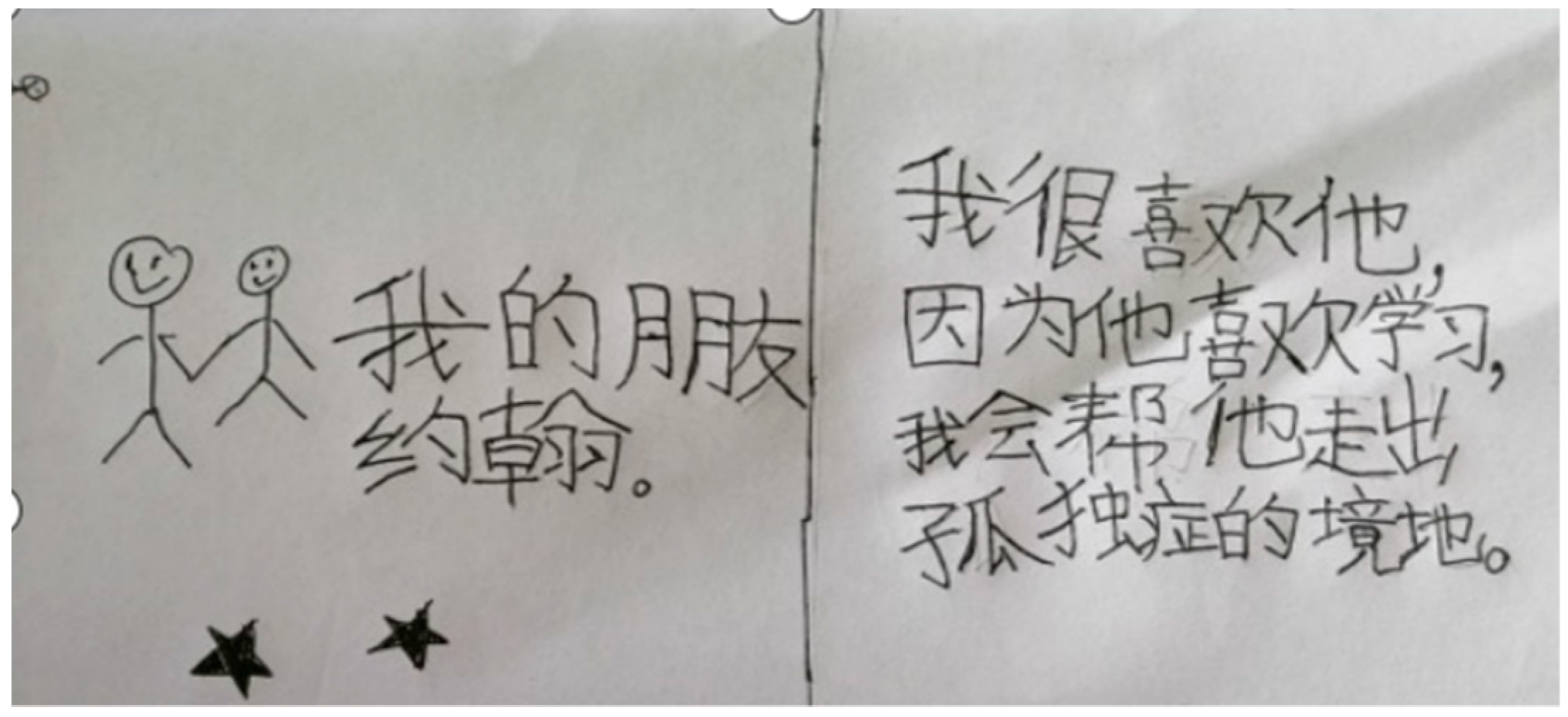

3.4. Participants’ Qualitative Responses on Their Attitudes Toward Children with Disabilities

4. Discussion

5. Practical Implications

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. An Example of One Picture Book’s Teaching Design (No Inconvenience)

| The First Class Hour (40 min) | ||

| Teaching goal | 1. Understanding the content of the story and getting to know the leading role who has a physical disability (Amin). 2. Combining practical experience to understand the similarities and differences between children with physical disability and selves. 3. Learning how to actively interact with children with physical disabilities. | |

| Teaching materials | PowerPoint of the picture book. Pictures and videos of the related topic. | |

| Teaching process | Leading-in 5 min | Showing the pictures on the PowerPoint and asking the questions: What can you discover by looking at the pictures? Have you ever seen someone in life using a crutch like this boy? (Inspiring students to think and leading into the topic) |

| Main content 30 min |

| |

| Summary/extension Activities/task assignment 5 min | How would you get along with a new classmate like Amin in your class? Encouraging the participants to try to experience the feeling of being on crutches with the help of their parents. Text, audio (voice/recording), video, and other forms about your feelings are encouraged to be shared online. | |

| Online feedback processing | Collecting online feedback from students and encouraging them in a timely manner. | |

| The Second Class Hour (40 min) | ||

| Teaching goal | 1. Review the story content and explain the reasons for the change in attitude of the little monkey. 2. Further deepen understanding of children with physical disabilities and learn coping strategies. 3. Combining practical thinking and understanding of accessible facilities. | |

| Teaching materials | PPT of the picture book. Pictures and videos of the related topic. | |

| Teaching process | Leading-in 5 min | We met Amin last class. The small task assigned by the teacher was also completed very well by everyone! Does anyone want to share their feelings in class? |

| Main content 30 min |

| |

| Summary/extension Activities/task assignment 5 min | Summary of these two classes: Task: You are asked to design an accessible facility. What aspects would you consider in designing it? How do you think designing it can better help these friends? Text, drawing, audio (voice/recording), video, and other forms about your design are encouraged to be shared online. | |

| Online feedback processing | Collecting online feedback from students and encouraging them promptly. | |

References

- Ahemaitijiang, D. (2022). Intervention on the peer relationship of children with special needs by picture books [Master’s thesis, Xinjiang Normal University]. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebetsos, E., Zafeiriadis, S., Derri, V., & Kyrgiridis, P. (2013). Relationship among student’ attitudes, intentions and behaviors toward the inclusion of peers with disabilities, in mainstream physical education classes. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 5(3), 233–248. [Google Scholar]

- Bogart, K. R., Bonnett, A. K., Logan, S. W., & Kallem, C. (2022). Intervening on disability attitudes through disability models and contact in psychology education. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, 8(1), 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottema-Beutel, K., & Li, Z. (2015). Adolescent judgments and reasoning about the failure to include peers with social disabilities. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(6), 1873–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottema-Beutel, K., Turiel, E., DeWitt, M. N., & Wolfberg, P. J. (2017). To include or not to include: Evaluations and reasoning about the failure to include peers with autism spectrum disorder in elementary students. Autism, 21(1), 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breckler, S. (1984). Empirical validation of affect, behaviour, and cognition as distinct components of attitude. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47(6), 1191–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, L., & Rutland, A. (2006). Extended contact through story reading in school: Reducing children’s prejudice toward the disabled. Journal of Social Issues, 62(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J. M., Ferguson, J. E., Herzinger, C. V., Jackson, J. N., & Marino, C. A. (2004). Combined descriptive and explanatory information improves peers’ perceptions of autism. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 25(4), 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, S., Park, E., & Shin, M. (2019). School-based interventions for improving disability awareness and attitudes towards disability of students without disabilities: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 66(4), 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M. Y., & McConkey, R. (2008). The perceptions and experiences of Taiwanese parents who have children with an intellectual disability. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 55(1), 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G., & Zhang, Z. (2013). A review on the measurement methods of attitude toward people with disabilities. Chinese Rehabilitation Theory and Practice, 19(2), 141–143. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L., Chen, X., Fu, W., Ma, X., & Zhao, M. (2021). Perceptions of inclusive school quality and well-being among parents of children with disabilities in China: The mediation role of resilience. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 68(6), 806–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinese Ministry of Education. (2021). Statistical bulletin on the development of national education in 2020. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_sjzl/sjzl_fztjgb/202108/t20210827_555004.html (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Dachez, J., Ndobo, A., & Ameline, A. (2015). French validation of the multidimensional attitude scale toward persons with disabilities (MAS): The case of attitudes toward autism and their moderating factors. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45, 2508–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, A., Pijl, S. J., & Minnaert, A. (2012). Student‘ attitudes towards peers with disabilities: A review of the literature. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 59(4), 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degenhardt, S., & Zhang, Y. X. (2015). Die VR China auf dem Weg zur inklusiven Schule [P. R. China is on the way to inclusive school]. In L. Annette, K. Müller, & T. Truckenbrodt (Eds.), Die UN-behindertenrechtskonvention und ihre umsetzung: Beiträge zur interkulturellen international vergleichenden heil- und sonderpädagogik (pp. 197–205). Verlag Julius Klinkhardt. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, K., & Tu, H. (2009). Relations between classroom context, physical disability and preschool children’s inclusion decisions. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 30(2), 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, R. (2019). The value of children’s emotional expression and its language promotion path. Early Childhood Education Research, 33(6), 85–88. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, J., Brown, J., & Beardsall, L. (1991). Family talk about feeling states and children’s later understanding of others’ emotions. Developmental Psychology, 27(3), 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X. (2012). A study on the intervention of ordinary children’s acceptance attitude toward peers with physical and mental disabilities [Master’s dissertation, Chongqing Normal University]. [Google Scholar]

- Findler, L., Vilchinsky, N., & Werner, S. (2007). The multidimensional attitudes scale toward persons with disabilities (MAS): Construction and validation. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 50(3), 166–176. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/multidimensional-attitudes-scale-toward-persons/docview/213913523/se-2 (accessed on 20 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Freer, J. R. R. (2021). The effects of the tripartite intervention on student‘ attitudes towards disability. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 22(1), 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, E., & Iarocci, G. (2014). Students with autism spectrum disorder in the university context: Peer acceptance predicts intention to volunteer. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(5), 1008–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiadi, M., Kalyva, E., Kourkoutas, E., & Tsakiris, V. (2012). Young children’s attitudes toward peers with intellectual disabilities: Effect of the type of school. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 25(6), 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, C. C., & Zambo, D. (2007). Loving and learning with Wemberly and David: Fostering emotional development in early childhood education. Early Childhood Education Journal, 34, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodkinson, A. (2007). Inclusive education and the cultural representation of disability and disabled people: Recipe for disaster or catalyst for change? An examination of nondisabled primary school children’s attitudes to children with disabilities. Research in Education, (77), 56–76. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/inclusive-education-cultural-representation/docview/213139096/se-2 (accessed on 20 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hoel, T., & Jernes, M. (2024). Quality in children’s digital picture books: Seven key strands for educational reflections for shared dialogue-based reading in early childhood settings. Early Years: An International Journal of Research and Development, 44(3–4), 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janja, B., & Dragica, H. (2013). Picture books featuring literary characters with special needs. Revija Za Elementarno Izobraževanje, 6(4), 37–51. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/literarni-lik-s-posebnimi-potrebami-v-slikanicah/docview/1466124242/se-2 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Ju, S. (2017). Intervention of primary school student’ attitude to people with disabilities [Doctoral dissertation, East China Normal University]. [Google Scholar]

- Kelman, H. C. (1974). Social influence and linkages between the individual and the social system: Further thoughts on the processes of compliance, identification, and internalization. In J. Tedeschi (Ed.), Perspectives on social power (pp. 125–171). Aldine. [Google Scholar]

- Killen, M., & Rutland, A. (2011). Children and social exclusion: Morality, prejudice, and group identity. Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J., Park, E., & Snell, M. E. (2005). Impact of information and weekly contact on attitudes of Korean general educators and nondisabled students regarding peers with disabilities. Mental Retardation, (6), 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. (2015). The value and Implementation strategy of picture book teaching in kindergarten. Preschool Education Research, 29(7), 70–72. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J., & Huo, B. (2023). Children’s picture book design based on emotional needs. Transactions on Social Science (Education and Humanities Research), 28(1), 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z. (2017). Research on Children’s peer communication in picture books [Master’s dissertation, Chongqing Normal University]. [Google Scholar]

- Livneh, H., Chan, F., Kaya, C., & Corrigan, P. W. (Eds.). (2014). The stigma of disease and disability: Understanding causes and overcoming injustices. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, A., Smith, M., Dempsey, I., Fischetti, J., & Amos, K. (2017). Short- and medium-term of Just Like You disability awareness program: A quasi-experimental comparison of alternative forms of program delivery in New South Wale‘ primary schools. Australian Journal of Education, 61(3), 288–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M., Pan, F., & Luo, J. (2020). Chinese validation of the multidimensional attitude scale toward persons with disabilities (MAS): Attitudes toward autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(10), 3777–3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L. (2021). A study on the status and relationship between peer relationship and school bullying among children in primary school [Master’s dissertation, Chongqing Normal University]. [Google Scholar]

- Mamas, C. (2020). Social participation and friendship quality of students with disabilities in inclusive schools. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(7), 2229–2240. [Google Scholar]

- Manola, M., Vouglanis, T., Maniou, F., & Driga, A. M. (2023). Children’s literature as a means of disability awareness and ICT’s role. Eximia, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Mantei, J., & Kervin, L. (2014). Interpreting the images in a picture book: Students make connections to themselves, their lives and experiences. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 13(2), 58–77. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/interpreting-images-picture-book-students-make/docview/1641166728/se-2 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Matias, S. G. (2003). Peer acceptance of children with disabilities in inclusive preschool programs: Predictors and implications (ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global A&I: The Humanities and Social Sciences Collection). Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/peer-acceptance-children-with-disabilities/docview/305249958/se-2 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- McDougall, J., DeWit, D. J., King, G., Miller, L. T., & Killip, S. (2004). High school-aged youths’ attitudes toward their peers with disabilities: The role of school and student interpersonal factors. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 51(3), 287–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, S., & Forlin, C. (2005). Attitude of students toward peers with disabilities: Relocating students from and Education Support Centre to an inclusive middle school setting. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 1(2), 18–30. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ854548.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Melloy, K. J. (1990). Attitudes and behavior of nondisabled elementary-aged children toward their peers with disabilities in integrated settings: An examination of the effects of treatment on quality of attitude, social status and critical social skills (ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global A&I: The Humanities and Social Sciences Collection). Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/attitudes-behavior-nondisabled-elementary-aged/docview/303869844/se-2 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Montag, J. L. (2019). Differences in sentence complexity in the text of children’s picture books and child-directed speech. First Language, 39(5), 527–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montag, J. L., Jones, M. N., & Smith, L. B. (2015). The words children hear: Picture books and the statistics for language learning. Psychological Science, 26(9), 1489–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaraizi, M., & de Reybekiel, N. (2001). A comparative study of children’s attitudes towards deaf children, children in wheelchairs and blind children in Greece and in the UK. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 16(2), 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Y. (2018). A study on the acceptance attitude and intervention of children aged 5–6 to children with special needs [Master’s Dissertation, East China Normal University]. [Google Scholar]

- Nowicki, E., & Sandieson, R. (2002). A Meta-analysis of school-age children’s attitudes towards persons with physical or intellectual disabilities. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, (3), 243–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petry, K. (2018). The relationship between class attitudes towards peers with a disability and peer acceptance, friendships and peer interactions of students with a disability in regular secondary schools. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 33(2), 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2008). How does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Meta-analytic tests of three mediators. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38(6), 922–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon-McBrayer, K. F., & McBrayer, P. A. (2014). Plotting Confucian and disability rights paradigms on the advocacy–activism continuum: Experiences of Chinese parents of children with dyslexia in Hong Kong. Cambridge Journal of Education, 44(1), 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiser, R. (1990). Don’t disable teachers with disabilities. British Journal of Special Education, 17(3), 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M., & Hovland, C. (1960). Cognitive, affective, and behavioural components of attitudes. In M. Rosenberg, C. Hovland, W. McGuire, R. Abelson, & J. Brehm (Eds.), Attitude organization and change (pp. 1–14). Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosinski, J. M. (1997). Typical children’s attitudes towards children with disabilities when exposed to general education classrooms utilizing inclusion versus general education classrooms without inclusion (ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global A&I: The Humanities and Social Sciences Collection). Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/typical-childrens-attitudes-towards-children-with/docview/304447607/se-2 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Rutland, A. (2004). The development and self-regulation of intergroup attitudes in children. In M. Bennett, & F. Sani (Eds.), The development of the social self (pp. 247–265). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiyad, S., Virk, A., Mahajan, R., & Singh, T. (2020). Online teaching in medical training: Establishing good online teaching practices from cumulative experience. International Journal of Applied and Basic Medical Research, 10(3), 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoppmann, J., Severin, F., Schneider, S., & Seehagen, S. (2023). The effect of picture book reading on young children’s use of an emotion regulation strategy. PLoS ONE, 18(8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwab, S. (2018). Peer Attitudes and the Development of Prejudice in Inclusive Schools. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 33(2), 175–185. [Google Scholar]

- Siperstein, G. N., Bak, J. J., & O’Keefe, P. (1988). Relationship between children’s attitudes toward and their social acceptance of mentally retarded peers. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 93(1), 24–27. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/relationship-between-childrens-attitudes-toward/docview/617540955/se-2 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Tabernero, R., & Calvo, V. (2020). Children with autism and picture books: Extending the reading experiences of autistic learners of primary age. Literacy, 54(1), 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, W. (2011). An evaluation of the Kids Are Kids Disability Awareness Program: Increasing social inclusion among children with physical disabilities. Journal of Social Work in Disability and Rehabilitation, 10(1), 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. (2024, May 15). Law of the people’s Republic of China on the protection of persons with disabilities [EB/OL]. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/guoqing/2021-10/29/content_5647618.htm (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Tufan, M. (2008). Kindergarten age typically developing children’s attitudes towards their peers with special needs in Turkey (ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global). Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/kindergarten-age-typically-developing-childrens/docview/304686352/se-2 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Varcoe, L., & Boyle, C. (2014). Pre-service primary teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education. Educational Psychology, 34(3), 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. (2015). Characteristics and intervention of primary school student’ attitude to people with disabilities [Master’s thesis, Shenyang Normal University]. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H. X., Peng, X., & Wang, Y. J. (2011). Investigation report on the present integrated education in primary schools in Haidian district Beijing. Chinese Journal of Special Education, 18(4), 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L., Han, W., & Deng, M. (2019). Disability in the eyes of ordinary children: A qualitative study of integrated kindergarten. Chinese Journal of Special Education, 26(7), 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M., & Li, H. (2020). Research on the attitude of integrated education of typically developing students in Xinjiang. Chinese Journal of Special Education, 27(3), 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, M. C., & Scior, K. (2013). Attitudes toward individuals with disabilities as measured by the implicit association test: A literature review. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 35(2), 294–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. (2001). International classification of functioning, disability and health. WHO. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y. (2018). Investigation on peer relationship of hearing-impaired students in integrated education environment. Chinese Journal of Special Education, 25(9), 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W., Lei, Y., Chen, K., & Hong, X. (2014). An experimental study on promoting prosocial behavior development of children by thematic picture book teaching. Journal of Education, 10(6), 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y. (2017). Innovation and thinking of picture book teaching in contemporary primary schools in China. Curriculum, Teaching Materials and Teaching Method, 37(10), 94–99. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y. (2019). Review and prospect of picture book teaching in primary schools. Chinese Journal of Education, 11(5), 63–67. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, S. K. (2008). A study on the methodology of the development of child’s creativity—Taking the creation of pictures for example [Master’s thesis, National Taitung University]. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. X., & Rosen, S. (2018). Confucian philosophy and contemporary Chinese societal attitudes toward people with disabilities and inclusive education. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 50(12), 1113–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J., & Liu, J. (2020). The effect of picture book reading on self-concept of 3-6 years old children: Based on literature analysis. Journal of Education and Academic Research, 15(7), 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Zucker, C. S. (1988). Changing attitudes of nonhandicapped elementary students toward their handicapped peers (ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global). Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/changing-attitudes-nonhandicapped-elementary/docview/303679870/se-2 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

| Boys | Girls | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 | 4 (11.1%) | 7 (19.4%) | 11 (30.6%) |

| Grade 2 | 3 (8.3%) | 6 (16.7%) | 9 (25%) |

| Grade 3 | 7 (19.4%) | 9 (25%) | 16 (44.4%) |

| Have contact with CWD | 4 (11.1%) | 5 (13.89%) | 9 (25%) |

| No experience with CWD | 10 (27.7%) | 17 (47.2%) | 27 (75%) |

| Total | 14 (38.9%) | 22 (61.1%) | 36 (100%) |

| Theme of Disabilities | Name of the Picture Book | Publication information of the Book |

|---|---|---|

| Physical disability | No inconvenience | Shi, Z. T. (2012). No Inconvenience. Nanjing: Nanjing Normal University Press. |

| Deaf and hard-of-hearing | I have a sister—My sister is deaf | Peterson, J. W., & Ray, D. K. (1977). I Have A Sister, My Sister Is Deaf. New York: Clinical Pediatrics. |

| Visual impairment | A beautiful mind sees the world | Haniger. (2012). A Beautiful Mind Sees the World. Wuhan: Hubei Children’s Publishing House. |

| Intellectual disability | Be good to Eddie Lee | Fleming, V. (1997). Be Good to Eddie Lee. Lundon: Penguin. |

| Learning disability | Madeline Finn and the library dog | Papp, L. (2019). Madeline Finn and The Library Dog. New York: Holiday House. |

| Autistic spectrum disorder | John from the Stars | Slovenia, Karajek, & Helena. (2016). John from the Stars. Beijing: Beijing Children’s Publishing House. |

| Dimension | Grade | F | LSD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 (n = 11) | G2 (n = 9) | G3 (n = 16) | |||

| negative behavior | 3.48 ± 0.96 | 4.04 ± 0.98 | 4.46 ± 0.97 | 3.31 * | G3 > G1 |

| Dimension | Grade | F | LSD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 (n = 11) | G2 (n = 9) | G3 (n = 16) | |||

| emotional | 3.21 ± 0.91 | 3.93 ± 0.88 | 4.15 ± 0.73 | 4.31 * | G3 > G1 |

| Dimension | Pre | Post | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cognitive | 2.64 ± 0.49 | 2.84 ± 0.36 | −2.73 | 0.010 * |

| emotional | 3.32 ± 1.09 | 3.81 ± 0.90 | −3.05 | 0.004 ** |

| positive behavior | 4.13 ± 0.68 | 4.52 ± 0.52 | −4.05 | 0.000 *** |

| negative behavior | 4.06 ± 1.03 | 4.57 ± 0.59 | −3.13 | 0.004 ** |

| attitude total | 3.48 ± 0.51 | 3.81 ± 0.43 | −4.41 | 0.000 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Fu, W.; Xiao, S. Online Picture Book Teaching as an Intervention to Improve Typically Developing Children’s Attitudes Toward Peers with Disabilities in General Schools. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 626. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050626

Zhang Y, Fu W, Xiao S. Online Picture Book Teaching as an Intervention to Improve Typically Developing Children’s Attitudes Toward Peers with Disabilities in General Schools. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(5):626. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050626

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yuexin, Wangqian Fu, and Shuheng Xiao. 2025. "Online Picture Book Teaching as an Intervention to Improve Typically Developing Children’s Attitudes Toward Peers with Disabilities in General Schools" Education Sciences 15, no. 5: 626. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050626

APA StyleZhang, Y., Fu, W., & Xiao, S. (2025). Online Picture Book Teaching as an Intervention to Improve Typically Developing Children’s Attitudes Toward Peers with Disabilities in General Schools. Education Sciences, 15(5), 626. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050626