Abstract

This review analyses the evolution of digital creativity from 2000 to 2022, defining it as a dynamic process where digital technologies foster collaboration, inclusion, self-expression, and automation. Based on 29 studies from databases such as Dialnet, UOC, Scopus, the Web of Science, and PsyINFO, and utilising the PRISMA and SPIDER methodologies, the research provides a comprehensive overview of the field. Digital creativity is described as the generation of new and valuable ideas, products, or solutions through digital tools that combine cognitive and socio-emotional skills in collaborative environments. Intuition, understood as the ability to make quick and effective decisions based on pattern recognition and prior experiences, plays a crucial role in the creative process. The study highlights its impact on education, enabling students to explore self-expression and solve problems creatively, merging analogue and digital creativity. In the professional realm, it optimises innovative processes, promoting efficiency and collaboration. The integration of emerging technologies, such as programming and 3D animation, in educational curricula is emphasised to prepare students for future challenges. Additionally, interdisciplinary research is advocated to ensure that digital tools amplify creativity, addressing ethical issues such as intellectual property and the social implications of automated creativity. Finally, the current trends such as game-based learning, innovation driven by social networks, and artificial intelligence are examined, proposing directions for future research.

1. Introduction

In the contemporary times, creativity has become a fundamental driver of human civilisation’s advancements and is closely linked to people’s social, educational, professional, and everyday lives. Over the past two centuries, there have been 150 years of debates and research to distinguish creativity from concepts such as imagination, originality, genius, and talent (Sternberg, 1999). For many years, creativity has been a subject of investigation; however, as digital technologies have become normative in communication, work, and entertainment, conventional definitions of creativity must be redefined and interpreted from the perspective of digital technology. According to K. C. Lee (2015), the era of digital creativity has arrived, where dreams have become real, accessible, and achievable for any individual, team, or organisation willing to pursue them.

Digital creativity refers to all forms of creativity driven by digital technologies, and its study is crucial to understanding how these technologies are changing the way people create and communicate. Furthermore, digital creativity has the potential to stimulate creativity in students and workers, which can lead to innovation and progress in a variety of fields (M. R. Lee & Chen, 2015).

Before diving into the realm of digital creativity, it is essential to start from a broader perspective: the concept of creativity itself. According to the definition by the Real Academia Española (RAE, 2023), creativity is defined as the “faculty of creating” or the “capacity for creation”. However, from a psychological perspective, creativity can be approached from multiple angles, as suggested by Esquivias (2004). It is important to note that as a scientific field, psychology has not yet reached a definitive definition of creativity. In this context, Fernández-Díaz et al. (2019) conducted an exhaustive review of the concept of creativity from various perspectives, considering its foundations in educational, artistic, and psychological domains, as well as its nature, which can manifest itself brilliantly and uniquely. This author concludes that creativity is “a relatively intangible term that, despite its multiple manifestations, remains difficult to define conclusively, with its definition remaining susceptible to broad acceptance” (p. 480).

Despite the diversity of approaches and definitions, the importance of digital creativity in contemporary culture and its transformative potential in a wide range of study and practice fields is undeniable. However, the concept of digital creativity continues to be a fertile ground for debate and controversy. Fundamental questions emerge, such as: what are the different conceptions of digital creativity? What are the distinctive characteristics that define them? These questions led us to adopt a research approach that involved a scoping review of various studies to obtain a comprehensive and updated definition of digital creativity. In this context, we explore the different considerations and definitions proposed by prominent authors over the past decades and dive into the most current fields of study and trends in digital creativity research.

1.1. Definitions and Theoretical Approaches to Creativity

Creativity encompasses the human ability to generate original and valuable ideas, think innovatively, and find ingenious solutions to problems. Over time, the research on creativity has evolved, adopting a variety of approaches to understand this complex phenomenon (Amabile, 1983; Csikszentmihalyi, 1996; De Bono, 1992; Feist, 1998; Gilhooly, 2016; Guilford, 1950; Ivcevic & Mayer, 2009; Ritter & Dijksterhuis, 2014; Runco & Jaeger, 2012; Sawyer, 2012; Simonton, 2003; Sternberg et al., 2005; Torrance, 1988). Hahn et al. (2013) highlight that this diversity of theories and approaches has made conceptualising creativity particularly challenging.

In the past 30 years, creativity research has explored three key themes, each reflecting the trends of its time (Williams et al., 2016). During the 1990s, studies often took a descriptive approach, focusing on innovation in the workplace. From 1995 to 2000, researchers shifted towards an applied focus, examining the creative process and how ideas are generated. More recently, research has taken a predictive turn, delving into the mechanisms behind creativity, particularly the roles of personality and intelligence in divergent thinking. In particular, Fernández-Díaz et al. (2019) found that intelligence was a dominant focus in studies conducted between 2007 and 2017.

Creativity has been examined through both implicit and explicit theoretical perspectives. Implicit theories suggest that people’s definitions of creativity influence their self-assessment and perception of their own creative potential. Sternberg and Lubart (1996) argue that the concept of creativity can vary not only between individuals but also between fields of knowledge, such as art, science, literature, and business. Similarly, Rudowicz (2003) emphasises that cultural factors shape the way that creativity is defined.

Explicit theories of creativity offer more structured explanations of its origins. Personalist theories focus on the individual, drawing their foundations from disciplines such as behaviorism, Gestalt psychology, constructivism, cognitive science, psychoanalysis, and humanism. For example, Weisberg’s incremental theory of creativity aligns with this individual-centric approach. In contrast, interactionist theories view creativity as the result of an individual’s interaction with their environment, as seen in Amabile’s componential model, Sternberg and Lubart’s investment theory, and Csikszentmihalyi’s systems model (Esquivias, 2004; Garaigordobil, 2003), currently among the most accepted by the community.

To better understand creativity, researchers have analysed it through four main parameters (Garaigordobil & Pérez-Fernández, 2004; Pérez-Fernández, 1997; Runco & Richards, 1997). The first focuses on the creative individual, examining cognitive traits, personality, motivation, and life events. Regarding the creative personality, Feist (1998) identified key traits such as openness and tolerance for ambiguity, while Ivcevic and Mayer (2009) highlighted adaptability and resilience.

The second explores the creative process, investigating its origins, duration, stages, and conscious or unconscious elements. Wallas (1926) proposed a four-stage model of the creative process: preparation, incubation, illumination, and verification. Recent research has expanded this to five stages by adding the “suggestions” phase to capture insights from neuroscience and intuition studies on decision making and problem solving (Sadler-Smith, 2015).

Runco and Jaeger (2012) underscore preparation as crucial to acquiring the knowledge and skills necessary for innovation. Incubation, according to Ritter and Dijksterhuis (2014), is an unconscious phase where initial ideas mature into innovative solutions. The illumination, described by Gilhooly (2016), represents the creative peak where new ideas emerge. Sawyer (2012) stresses that evaluation and verification are essential for refining and implementing ideas effectively. Divergence and convergence, as noted by Guilford (1950), play a fundamental role in generating and refining ideas. De Bono (2015) advocates for lateral thinking exercises to foster divergent thinking.

The third examines the creative product, assessing problem-solving outcomes and the results of creativity tests. Simonton (2003) adds that variability in creative output is due to personal and cognitive differences. The fourth parameter considers the environment, including family, educational, and professional settings. A fifth transversal parameter addresses creative behaviour by analysing the influence of motivation, environmental factors, and everyday applicability. On the topic of creative behaviour, Amabile (1983) explored how intrinsic motivation and environmental factors influence creative expression.

1.2. Definition and Fields of Study in Digital Creativity

In the contemporary era, we are witnessing an increase in digital creativity (K. C. Lee, 2015). Digital creativity plays a fundamental role in how people create and communicate (M. R. Lee & Chen, 2015; Paulus & Nijstad, 2003; Shneiderman, 2002). Its potential to stimulate innovation in both educational and professional settings is significant (M. R. Lee & Chen, 2015). In educational and professional settings, institutions and organisations increasingly rely on collaborative teams to solve problems creatively or design new products and services. These group dynamics foster the development of critical skills in both students and professionals, such as innovative thinking, the ability to work in teams, and the adaptation to changing environments. This approach prepares individuals for complex challenges and contributes to the advancement in their respective fields of study and work. In this regard, Shneiderman (2002) highlights how digital technologies open new creative avenues, while Paulus and Nijstad (2003) underscore the role of digital collaboration in improving creativity through enriched interactions facilitated by technological tools.

The research on digital creativity is constantly evolving, and several areas of interest have been delineated. One of these areas focuses on creativity in social networks, addressing how people use social media platforms as a means to express their creativity through the creation and sharing of digital content. In this context, social networks have transformed into genuine platforms for creative expression and communication. Ali et al. (2019) propose a mechanism to examine the effects of three key dimensions of social networks, namely social, cognitive, and hedonic use, on team creative performance. Choi and Behm-Morawitz (2020) have delved into motivation and creativity in the production of social media content. The accelerated advancement of technology, such as social networks, artificial intelligence, and virtual reality, has motivated many educators to explore and implement a variety of digital tools in the educational field, investigating the intersection between creativity and technology in the classroom (Al Hashimi et al., 2019). Hu et al. (2017) argue that cultural intelligence exerts a significant influence on individual creativity, leading to the suggestion that social networks can standardise cultural intelligence and consequently promote a sense of community creativity. McKay et al. (2017) conducted in-depth research on the relationship between social networks and creativity, proposing two fundamental hypotheses. The first hypothesis yielded mixed results, as high-school students tend to relate to friends with similar levels of creativity. The second hypothesis, however, revealed a positive correlation between friendship and originality, as people nominated individuals with high levels of creativity without necessarily having an established friendship.

Another area of great interest in the context of digital creativity is focused on creative online learning and how online platforms and distance education can catalyse the development of creative skills and problem solving. A study by Tang et al. (2022) identified six categories of digital technology products that contribute to this process, encompassing information storage and sharing, digital games, digital design, digital writing, robotics, and virtual learning environments. Additionally, four key methods for evaluating student creativity were established, considering students’ creative characteristics, results achieved, the learning process, and the teaching environment. Tang and his colleagues’ analysis also broke down five ways in which digital technology products influence students’ creativity. These include increasing motivation, promoting professional activities, stimulating higher-order thinking, facilitating creative collaboration, and effectively managing the cognitive load. In a similar context, Li et al. (2022) highlight that, in line with the growth of digital tools, educators have begun to pay attention to the need to incorporate emerging technologies to effectively support the development of creativity, indicating that existing studies point to these emerging technologies having a positive impact on fostering students’ creativity, especially in interactive learning environments.

Another aspect of interest lies in exploring the role of artificial intelligence (AI) in enhancing human creativity and, in some cases, autonomously generating creative works. AI is distinguished by its ability to automate creative tasks, allowing professionals to focus on the more strategic and conceptual aspects of creativity. Boden (1998) delves into the concept of “artificial creativity” and analyses how artificial intelligence can mimic and stimulate human creativity. Elgammal and Mazzone (2020) note that artists using artificial intelligence have managed to create interesting and novel works through machine training and generative processes. These authors aim to achieve a deeper understanding of creativity, whether it emanates from a machine or from a human. To this end, they have developed an art-generating system called “Playform”. This pioneering approach highlights the growing influence of artificial intelligence on creative expression.

On the other hand, significant ethical issues arise in the realm of digital creativity, addressing aspects such as intellectual property, plagiarism, and online privacy. Intellectual property encompasses the legal rights that protect individuals’ intellectual creations, such as literary, artistic, and musical works. Lessig (2004) has made significant contributions to this field, arguing that intellectual property laws must strike a balance between creators’ interests and society’s well-being as a whole. Plagiarism, for its part, has emerged as a major ethical concern in the realm of digital creativity. Buckwalter et al. (2012) have conducted a comprehensive exploration of this topic, analysing in depth the implications of plagiarism in research and online creativity.

As we have seen, various perspectives and areas of interest are presented in the field of digital creativity, resulting in the proliferation of multiple definitions dispersed across a variety of articles and publications. This multiplicity of approaches underscores the urgent need to perform a comprehensive review of the concept. This review seeks not only to clarify but also to synthesise the various dimensions of digital creativity comprehensively.

1.3. The Present Study

Building on these premises and the theoretical and empirical findings from the previous scientific literature, this research aims to analyse the definitions, characteristics, and approaches to digital creativity in various application contexts. To address this overall objective, the review employs the SPIDER protocol (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research Type) (Cooke et al., 2012), and we propose the following specific objectives together with their corresponding research questions and initial hypotheses.

The first specific objective is to identify and analyse the general and unique characteristics of digital creativity. The key research questions include the following. What theoretical approaches do recent studies on digital creativity adopt? Are there similarities and differences in the way digital creativity is defined? What virtual tools are used for creative purposes? According to existing theories, there are various theoretical frameworks and definitions of digital creativity, along with a variety of digital tools used to support creative processes.

The second specific objective is to assess and interpret the current research trends and fields of study related to digital creativity. Central research questions include the following: Which fields of study have shown the most scientific interest? What are the emerging applications and trends in digital creativity? In an increasingly digital world where virtual tools are introduced from an early age, it is expected that different forms of digital creativity coexist, particularly in education, where its role is becoming ever more prominent.

2. Methods

For this purpose, a scoping review or exploratory systematic review (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Letelier et al., 2005; Munn et al., 2018; Peters et al., 2015; Tricco et al., 2018) was conducted through the analysis and synthesis of the available information on digital creativity, following the Guidelines for recommendations on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA), with the aim of facilitating the reproducibility and comprehension of the results by other researchers (Page et al., 2021; Sánchez-Meca, 2022). Scoping reviews, a type of knowledge synthesis, follow a systematic approach to map evidence on a topic and identify the main concepts, theories, sources, and knowledge gaps, offering a broad overview of a wide field; these reviews are intended for a preliminary exploration of a topic, identifying essential elements and highlighting the aspects that require further investigation (Tricco et al., 2018). These reviews serve as the starting point for subsequent systematic reviews. This scoping review aims to summarise the existing evidence on creativity in the digital domain. In doing so, it not only provides a clear and organised overview of what has been researched so far, but also highlights areas where there are gaps in the knowledge. With this information, future research can be guided, directing efforts towards aspects that need more attention and study. To minimise the bias risk, the Cochrane Collaboration Tool was used, as outlined in the following sections.

2.1. Information Sources

To search for publications, five academic databases were explored: Dialnet and UOC (Universitat Oberta de Catalunya), featuring contributions from the authors of various nationalities, with a significant number of publications originating from Spain and other Spanish-speaking countries, the Web of Science (WOS) and Scopus, with publications in English and Spanish in multidisciplinary fields, providing a comprehensive and diverse perspective on the investigated topic (Börner et al., 2010), and lastly, PsyInfo, to ensure the inclusion of publications on digital creativity from the psychological field.

2.2. Search Strategy

The search process for publications in various academic search engines was conducted in October 2022. The term used was “digital creativity”, both in English (WOS, Scopus, and PsycINFO) and in English and Spanish (UOC and Dialnet), according to the specific characteristics of each database, using the following search formula: (digital AND creativity) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Databases and number of references.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were established throughout the study selection process. Regarding the inclusion criteria, this scoping review included studies in which the authors addressed the topic of digital creativity, proposed virtual tools for creation in diverse contexts, analysed the impact of digital creativity between disciplines, or jointly examined creativity and digital creativity. The review included peer-reviewed journal articles, books, doctoral theses, and conference proceedings, published predominantly in English (the primary language of scientific literature), since a high percentage of scientific and academic publications on digital creativity are in this language, thus ensuring a broad and relevant coverage in most knowledge areas (Montgomery, 2009). Spanish was also selected, as it is one of the languages spoken most widely worldwide and is important in scientific production, especially in disciplines such as social sciences, humanities, and certain areas of science and technology (Salager-Meyer, 2008). The search was temporally limited to studies published between 2000 and 2022, inclusive. Regarding the exclusion criteria, studies that did not provide their own definitions or those of other authors of the concept of digital creativity or focused on other domains of creativity, such as artistic, literary, musical, or product design creativity, without the use of digital tools, were excluded from the initial selection after reviewing the titles, abstracts, and content.

2.4. Data Extraction Process

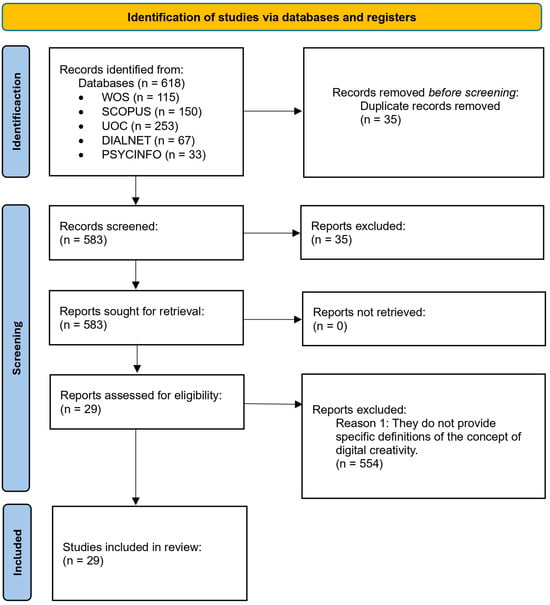

The initial literature search in the databases provided a total of 618 research studies (Figure 1). Subsequently, 35 duplicate references were removed, and 583 publications were selected according to their titles and abstracts. The same set of publications was further analysed and studied by reading and examining the full text, selecting those that met the eligibility criteria. A final total of 29 publications were included in the review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection process.

From the selected publications, the following data were extracted: citation (author/year), country of origin, study objective, methodology, and scientific impact (Table 2). Studies were carried out on various continents: 5 in Asia (Korea, Taiwan and China), 4 in the Americas (North America), 1 in Oceania (Australia), and 19 in Europe (Denmark, UK, Italy, Greece, Romania, Switzerland, Spain, Germany, and Portugal).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the studies analysed.

The study objectives varied, focusing on the following areas: exploring digital creativity in various contexts (Copplestone & Dunne, 2017; Hisrich & Soltanifar, 2021; Prasch et al., 2022; Seo & Lee, 2011; Zagalo & Branco, 2015), analysing educational and pedagogical aspects related to digital creativity (Biskjaer et al., 2021; Brooks & Brooks, 2015; Di Fuccio et al., 2020; Frich et al., 2018; Harwood, 2013; Kemp, 2020; Kikis-Papadakis & Chaimala, 2019; Oropesa et al., 2018; Samoila et al., 2015; Shin, 2010; Sica et al., 2020; Valero-Matas, 2020), evaluating and developing tools that support digital creativity (Carroll, 2013; Cybulski et al., 2015; Frich et al., 2019; Maiden et al., 2019; McGrath et al., 2016), investigating theoretical approaches and conceptualising digital creativity (Hahn et al., 2013; K. C. Lee, 2015; M. R. Lee & Chen, 2015; Pizzo & Valle, 2014), and examining the relationships between digital creativity and social or psychological factors (Pérez-Fuentes et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2022).

Regarding the research methodology, the studies included 15 reviews of the literature, 8 quantitative studies, 3 qualitative studies, 2 bibliometric reviews, and 1 case study.

3. Results

The following results are presented, addressing, on the one hand, the definitions of the concept of digital creativity provided by different authors, as well as the theoretical approaches analysed in the research, and, on the other hand, the fields of knowledge, keywords, and conclusions of the analysis of the research are discussed.

3.1. Comparative Analysis of Definitions and Theoretical Approaches to Digital Creativity

To address the objectives and research questions, the following is an integrated analysis based on the most relevant findings and conclusions. To identify and analyse the general and distinctive characteristics of digital creativity, the research questions were as follows: What theoretical approaches have recent studies on digital creativity adopted? Are there similarities and differences in how digital creativity is defined by different authors? What virtual tools are used for creation? In Table 3, the various definitions and their theoretical foundations are compared, highlighting the main similarities and differences between them. Regarding the first research question, recent studies highlight a wide range of theoretical approaches, spanning psychological and pedagogical paradigms as well as technological and cultural frameworks (Bardzell, 2007; Biskjaer et al., 2021; Brooks & Brooks, 2015; Carroll, 2013; Di Fuccio et al., 2020; Frich et al., 2018; Frich et al., 2019; Hahn et al., 2013; Harwood, 2013; Kemp, 2020; M. R. Lee & Chen, 2015; Maiden et al., 2019; Oropesa et al., 2018; Pérez-Fuentes et al., 2019; Samoila et al., 2015; Shin, 2010; Seo & Lee, 2011; Sica et al., 2020; Zagalo & Branco, 2015; Zhang et al., 2022).

Table 3.

Comparative analysis of definitions and theoretical approaches to digital creativity.

Regarding the second research question, there is a general consensus that digital creativity involves processes driven by digital technologies to generate original and valuable ideas across various contexts (Cybulski et al., 2015; Seo & Lee, 2011). However, the focus varies: some authors regard digital creativity as an individual capacity (aligned with personalist theories), while others emphasise the importance of social interaction and collaboration (interactionist approaches) (Cybulski et al., 2015; Harwood, 2013; K. C. Lee, 2015; McGrath et al., 2016).

In relation to the third research question, regarding the tools used for digital creation, the literature mentions creativity support tools (CST), multimedia authoring platforms, interactive visual analytics (IVA), 3D design applications, and educational gamification tools (Bardzell, 2007; Cybulski et al., 2015; Di Fuccio et al., 2020; Frich et al., 2018, 2019; Maiden et al., 2019; Sica et al., 2020; Zagalo & Branco, 2015). These resources support both individual expression and collaborative co-creation within digital environments (Frich et al., 2018; Harwood, 2013; Oropesa et al., 2018; Paulus & Nijstad, 2003; Pérez-Fuentes et al., 2019; Samoila et al., 2015).

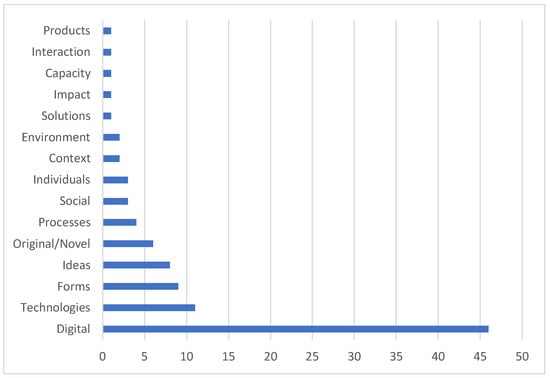

Regarding the frequency of various terms used in the definitions, the term “digital” is the most frequent (46 occurrences), reflecting the central role of digital technology in these definitions. “Ideas” (eight occurrences), “technologies” (eleven occurrences), and “original” or “new” (six occurrences) are also key terms that appear repeatedly, indicating a focus on innovation and the use of technology in creativity. Terms such as “individuals” (three occurrences) “context” (two occurrences), and “processes” (four occurrences) highlight the importance of social and contextual dimensions in the definitions of digital creativity (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Frequency of terms used in definitions of digital creativity.

3.2. Evaluative and Interpretative Analysis of the Current Study Fields and Trends in Digital Creativity Research

To assess and interpret the fields of study and current research trends in digital creativity, the research questions comprised the following: What are the fields of study of greatest scientific interest? What are the emerging applications and trends in digital creativity? Regarding the fields of study of the greatest scientific interest, studies on digital creativity span multiple disciplines, with education, professional contexts, and cultural sectors being particularly prominent (for example, Hahn et al., 2013; Harwood, 2013; Hoffmann et al., 2016) (Table 4). The educational domain receives significant attention, with research focused on the use of digital technologies to foster divergent thinking, self-expression, and problem solving (Brooks & Brooks, 2015; Di Fuccio et al., 2020; Pérez-Fuentes et al., 2019; Sica et al., 2020; Shin, 2010, among others).

Table 4.

Evaluative analysis of current study fields and trends in digital creativity research.

In terms of the current emerging applications and trends, game-based learning and simulations represent the key emerging trends, as demonstrated by tools such as the Do-CENT project, which promotes creativity through student-centred methodologies (Kikis-Papadakis & Chaimala, 2019). In professional contexts, research highlights the role of digital collaboration tools in enhancing innovation and co-creation within workplace processes (Harwood, 2013; Samoila et al., 2015). Furthermore, studies in the cultural sector emphasise the growing use of digital narratives, where immersive technologies provide new ways of engaging with cultural heritage and history (Copplestone & Dunne, 2017).

Therefore, definitions and approaches to digital creativity vary between authors and disciplines, but share common elements, such as innovation, technological interaction, and the promotion of self-expression and problem solving. The review underscores an expanding field that increasingly integrates emerging technologies into education and cultural participation. There is also a consistent focus on ensuring that digital tools enhance, rather than limit, the creative potential.

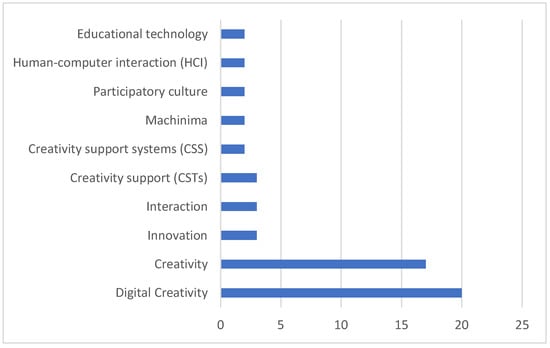

The results of the analysis of the keywords most frequently used by the authors in the reviewed studies are presented (Table 4). As shown in Figure 3, the two most frequent keywords are “Digital Creativity” (20 occurrences) and “Creativity” (17 occurrences). Less commonly used keywords include “Creativity Support” (CSTs) (three occurrences), “Interaction” (three occurrences), and “Innovation” (three occurrences). Following these, with the same frequency, are “Human–computer interaction (HCI)” (two occurrences), “Machinima” (two occurrences), “Participatory culture” (two occurrences), “Educational technology” (two occurrences), and “Creativity support systems” (CSS) (two occurrences).

Figure 3.

Frequency of keyword usage in the analysed studies.

Additionally, the fields of study of significant scientific interest were analysed for their contribution to understanding and developing digital creativity in various areas, from technology to education and organisational psychology, with an interdisciplinary perspective. Of the twenty-nine studies analysed, twelve focused on the educational context, seven on the business sector, five on information sciences, three on social sciences, one on both information and social sciences, and one on both business and social sciences.

4. Discussion

The discussion that we outline below addresses the main topics of this work in the order in which the previously presented results have been reviewed.

4.1. Definitions and Theoretical Approaches to Digital Creativity

This review study has allowed us to identify and analyse the general and differential characteristics of digital creativity, thus meeting our first research objective. In this regard, the results of this scoping review reveal that the definitions of creativity in the digital domain share certain commonalities but also exhibit significant differences in approaches and emphasis. Most definitions agree that creativity, in its digital or general form, involves a process of producing original and useful ideas or products (Cybulski et al., 2015; Frich et al., 2018; Hisrich & Soltanifar, 2021; Kikis-Papadakis & Chaimala, 2019; McGrath et al., 2016; Seo & Lee, 2011; Zhang et al., 2022). A considerable number of definitions suggest that creativity should be considered within a social or cultural context, acknowledging that the environment influences how creativity is generated and valued (Bardzell, 2007; Biskjaer et al., 2021; Carroll, 2013; Cybulski et al., 2015; Frich et al., 2018; Loveless, 2002; Plucker et al., 2004; Samoila et al., 2015; Shin, 2010; Zagalo & Branco, 2015). This point is clearly refuted in the approach of Loveless (2002), which explicitly mentions the sociocultural context, as well as in the definition of Plucker et al. (2004), which emphasises the im-portance of an individual’s interaction with his environment. The relationship between personal, technological, and social factors is also a recurring theme in the definitions (Carroll, 2013; Hahn et al., 2013; Kemp, 2020; Loveless, 2002; Oropesa et al., 2018; Pérez-Fuentes et al., 2019; Seo & Lee, 2011; Samoila et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2022). Furthermore, some studies emphasized that both digital and general creativity produce innovative and useful results in a particular context (Carroll, 2013; Cybulski et al., 2015; Frich et al., 2019; Maiden et al., 2019; McGrath et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2022).

Some definitions of digital creativity are more abstract and general, for example, those that define digital creativity as “all forms of creativity driven by digital technolo-gies” (K. C. Lee, 2015), while others are more specific and operational, linking digital creativity to concrete problem solving or the development of useful products (Cybulski et al., 2015; Seo & Lee, 2011). In this sense, Harwood (2013) argued that digital creativity transforms passive consumers into active participants. Along this line, some definitions, such as that of Cybulski et al. (2015), emphasises the role of interactive data visualisation as a facilitator of creativity, suggesting that it can offer nonexperts the opportunity to engage creatively in data analysis.

However, other definitions consider technology to be simply a tool within a larger creative process (Frich et al., 2018, 2019; Biskjaer et al., 2021). Therefore, many definitions highlight that digital creativity is the result of the interaction between technology and human capacity (Frich et al., 2018; Harwood, 2013; Oropesa et al., 2018; Pérez-Fuentes et al., 2019; Plucker et al., 2004; Seo & Lee, 2011; Zagalo & Branco, 2015). This concept is evident in the definitions that refer to digital technologies as tools to solve problems, generate products, or facilitate collaboration, as supported by Seo and Lee (2011).

The notion that digital creativity is inherently participative and collaborative also appears in several definitions (Harwood, 2013; Zagalo & Branco, 2015). However, some definitions focus on collaboration within creative teams or groups (Harwood, 2013), while others place greater emphasis on individual self-expression enabled by digital technologies (Oropesa et al., 2018; Pérez-Fuentes et al., 2019). In this sense, some definitions describe creativity as a distributed activity, not confined to a single mind, but enriched by collaboration and digital tools. This approach is in agreement with distributed cognition (Frich et al., 2018; Plucker et al., 2004).

Although several definitions consider digital creativity as a manifestation of tech-nology-facilitated creativity, some focus more on daily life and digital self-expression (Hoffmann et al., 2016; Oropesa et al., 2018; Pérez-Fuentes et al., 2019), while others measure productivity or technological innovation (Prasch et al., 2022).

Furthermore, while some definitions approach digital creativity in broad terms, encompassing various forms of creative expression enabled by technology (Oropesa et al., 2018; Zagalo & Branco, 2015), others, particularly those related to specific creative support tools, narrow the concept to certain environments or specific technical processes (Carroll, 2013; Frich et al., 2018). In this direction, some definitions highlight the use of digital creativity in scientific, humanistic, and artistic settings (Carroll, 2013; Prasch et al., 2022), while others focus on educational applications or creativity as part of daily life (Hoffmann et al., 2016; Oropesa et al., 2018; Pérez-Fuentes et al., 2019).

In summary, digital creativity involves problem solving, creating new products, collaborating, and using technology to support creative thinking. The diversity of definitions reflects the richness and complexity of this concept in the context of the digital age. For our part, based on the research conducted, the following definition of digital creativity is proposed: Digital creativity is a multifaceted process in which new and valuable ideas, products, or solutions are generated through the use of digital technologies. This process involves the interaction between cognitive and socio-emotional skills, technological tools, and a collaborative environment, facilitating both self-expression and creative problem solving in various contexts (educational, professional, cultural, and social). In this process, intuition plays a crucial role, relying on previous experiences, accumulated knowledge, and patterns recognised by the brain. Additionally, digital creativity is characterised by its capacity to enhance co-creation, democratise the access to creative resources, and foster new dynamics of participation and autonomous learning. This definition is based on the integration of multiple theoretical perspectives, including the interaction between individuals and technology, the influence of the socio-educational context, the collaborative work dynamics enhanced by digital tools, and cognitive neuroscience. The various approaches reviewed have been considered, such as the importance of divergent thinking, the use of creativity support tools (CSTs) and the inclusion of emerging elements such as artificial intelligence and multimedia storytelling.

To understand the various aspects of digital creativity and how they interrelate in different contexts and approaches, the researchers grouped the parameters into the following categories: tools and technologies, individual and group creativity, creative processes, and educational contexts. Studies that focused on the relationship between tools and technologies analysed the mediating role of multimedia authoring tools in digital art (Bardzell, 2007), the creation of digital content through web technologies (Shin, 2010), the use of creativity support tools in collaborative and real-world settings (Frich et al., 2018), and the relationship between creativity support tools or digital technologies and creative processes (Frich et al., 2018, 2019; Kikis-Papadakis & Chaimala, 2019). Other studies explored digital creativity and the use of interactive visual analysis tools (Cybulski et al., 2015).

Other research explored individual and social creativity, examining how social and emotional intelligence influence knowledge exploration and exploitation (Hahn et al., 2013), as well as real-time personal creative experience (ITMC) (Carroll, 2013), digital creative behaviour (Oropesa et al., 2018; Pérez-Fuentes et al., 2019), internal expression through various creative possibilities (Zagalo & Branco, 2015), and creative solutions from the perspective of social creativity (Samoila et al., 2015), among other topics.

Studies on creative processes analysed problem solving and the creation of new useful products in digital environments (Samoila et al., 2015), topics related to exploration and exploitation within different contexts of digital creativity, including individual and team creativity (K. C. Lee, 2015), the relationship between the creative process and the environment, particularly within a social context (Biskjaer et al., 2021), creative processes in educational settings through digital technologies (Di Fuccio et al., 2020), dimensions of digital creativity in educational contexts (Hoffmann et al., 2016), and the creation of products using 3D animation (Di Fuccio et al., 2020).

Some researchers investigated digital creativity in educational settings, for example, the relationship between digital creativity, academic performance, and parenting styles (Pérez-Fuentes et al., 2019) or the analysis of digital tools within an inclusive framework to promote divergent thinking (Sica et al., 2020).

4.2. Current Study Fields and the Trends in Digital Creativity Research

Another prominent goal of this study was to evaluate and interpret the current studies and trends in research on digital creativity, achieving our second research objective. The studies analysed highlighted that the educational field exhibits a wide range of emerging trends. In this regard, several studies have argued that the use of technology in compulsory education, particularly through playful interactions, is emerging as a key approach to stimulate creative expression among children and adolescents (Hoffmann et al., 2016; Sica et al., 2020; Oropesa et al., 2018; Pérez-Fuentes et al., 2019). Along this line, video games, such as the DoCENT tool, have shown promise in improving digital creativity and teaching, with the potential for expanded use in various educational contexts (Sica et al., 2020).

Furthermore, another significant line of research revealed the inclusion of digital tools in arts education to foster student creativity and cultural relevance, suggesting a shift toward teaching digital competencies in visual arts, enriching pedagogical approaches (Bardzell, 2007; Harwood, 2013; Kemp, 2020; M. R. Lee & Chen, 2015; Shin, 2010). In the educational context, Samoila et al. (2015) highlighted the potential of remote experiments to enhance the digital creativity in education, underlining the importance of digital platforms as tools for creative teaching and innovation. In this context, the production of amateur multimedia content was culturally significant (Bardzell, 2007), opening opportunities for platforms and tools that foster creative expression among non-professionals, democratising the access to digital creativity.

In the professional arena, various studies have shown that task diversity and communication effectiveness play a crucial role in the promotion of digital creativity (Frich et al., 2018; Harwood, 2013; Seo & Lee, 2011; Zagalo & Branco, 2015), suggesting that digital collaboration tools that facilitate expert interaction can improve the creativity in both professional and educational settings. Furthermore, various methodologies are advancing in the evaluation of creativity support tools (CSTs) (Carroll, 2013; Cybulski et al., 2015; Frich et al., 2019; Maiden et al., 2019; McGrath et al., 2016), which can guide the development of better systems to foster creativity in digital environments.

Another area of interest revealed that digital tools are essential to drive creativity in business settings (Carroll, 2013; Frich et al., 2018), facilitating innovation and long-term success in the digital age. Collaboration between teams through digital platforms is emerging as an essential trend to promote creativity in organisational contexts (Harwood, 2013), especially during the action phases of complex projects. The use of visualisation and interaction tools (IVA) for creative problem solving in big data contexts is also a growing trend (Cybulski et al., 2015), with potential applications in data science and data-driven decision making.

Finally, in this context, the transformative role of digital narratives and their ability to reshape how we relate to the past (Copplestone & Dunne, 2017) opens up new applications in heritage studies, museums, and education, where immersive narratives and multimedia technology play a crucial role.

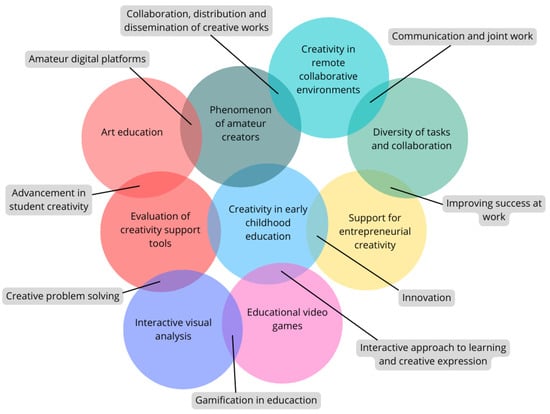

These trends show a complex and dynamic landscape where different factors enhance the creativity in collaborative settings (Figure 4). Future studies could contrast these findings and expand the research in this direction.

Figure 4.

Venn diagram of intersections among emerging trends in digital creativity.

This study is not without its limitations. The data collection was limited to a specific time range, and, therefore, certain academic search engines, so the generalisation of the results is confined to these circumstances. In addition, most of the selected studies were written in English and Spanish, covering multiple countries, but not all spoken languages. This could bias the results towards the perspectives and contexts predominant in countries where English and Spanish are spoken. However, a significant number of researchers from different countries publish their research in English. Similarly, the search strategy focused on the Dialnet, UOC, WOS, and Scopus databases, both globally recognised and used due to their easy accessibility, optimal metrics, and wide coverage, and PsycINFO databases, which may have unintentionally excluded research published on other resources. This underscores the importance of considering a more inclusive and comprehensive approach in future research and study replications to ensure a broader representation of the studied topic.

5. Conclusions

The scientific literature on digital creativity has revealed a wide spectrum of definitions and approaches. In recent studies, digital creativity has been defined as the application of digital technologies to promote the generation of novel and useful ideas, products, and solutions that can vary across academic and professional contexts. Digital creativity has emerged as a multifaceted phenomenon, where digital tools enable creation and experimentation in a collaborative, inclusive, and often automated environment.

The digital environment is presented as a facilitator of creativity, with collaborative digital environments and creativity support tools playing an essential role. In educational contexts, digital creativity could be nurtured through technological tools in the classroom, allowing students to explore new forms of self-expression and solve problems creatively. This educational approach to digital creativity underscores the need to integrate emerging technologies, such as programming and 3D animation, into school curricula to prepare young people for future challenges. In professional settings, digital creativity has also been linked to optimising creative processes. Despite these clear benefits, it is important to mention some cognitive risks such as information overload, technological dependency, distraction, and procrastination, and social risks such as social isolation. To avoid these risks, it is recommended that digital creativity be combined with analogue creativity in educational and professional contexts, which can contribute to increasing motivation, achieving a state of flow, and enhancing social skills.

The need for greater interdisciplinarity in digital creativity is also highlighted. It also highlights the need for greater interdisciplinarity in digital creativity research, taking into account the insights provided by cognitive neuroscience on the underlying mechanisms of creativity in digital contexts: brain plasticity during the enhancement of creative skills in teaching–learning contexts, the design of digital tools that improve the relationship between divergent and convergent thinking in the creative process, and the optimisation of the interaction between individuals and technologies. Future research should explore how to integrate these advances in fields to ensure that digital tools enhance creativity rather than limit it.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.F.O.-R. and J.J.S.-M.; methodology, J.J.S.-M. and N.F.O.-R.; investigation, J.J.S.-M. and N.F.O.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, N.F.O.-R. and J.J.S.-M.; writing—review and editing N.F.O.-R. and J.J.S.-M.; supervision, N.F.O.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been partially funded by the call for the creation of teaching innovation groups for the 2022 and 2023 biennium at the University of Almería (Code: 22_23_1_24C). The project administration was overseen by Nieves Fátima Oropesa Ruiz.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Al Hashimi, S. A., Al Muwali, A. A., Zaki, Y. E., & Mahdi, N. A. (2019). The effectiveness of social media and multimedia-based pedagogy in enhancing creativity among students in art, design, and digital media. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET), 14(21), 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A., Wang, H., & Khan, A. N. (2019). Mechanism to enhance team creative performance through social media: A transactive memory system approach. Computers in Human Behaviour, 91, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T. M. (1983). The social psychology of creativity: A componential conceptualization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(2), 357–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardzell, J. (2007). Creativity in amateur multimedia: Popular culture, critical theory, and HCI. Human Technology: An Interdisciplinary Journal on Humans in ICT Environments, 3(1), 12–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biskjaer, M. M., Iversen, O. S., & Dindler, C. (2021). Cultivating creativity in computing education: A missed opportunity? In S. Lemmetty, K. Collin, V. P. Glăveanu, & P. Forsman (Eds.), Creativity and learning (pp. 89–113). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, M. A. (1998). Creativity and artificial intelligence. Artificial Intelligence, 103(1–2), 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börner, K., Chen, C., & Boyack, K. W. (2010). Visualizing knowledge domains. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 37(1), 179–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, E. P., & Brooks, A. L. (2015). Digital creativity: Children’s playful mastery of technology. In A. L. Brooks, E. Ayiter, & O. Yazicigil (Eds.), Arts and technology (Vol. 145, pp. 116–127). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckwalter, J. A., Wright, T., Mogoanta, L., & Alman, B. (2012). Plagiarism: An assault on the integrity of scientific research. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 30(12), 1867–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, E. (2013). Quantifying the personal creative experience: Evaluation of digital creativity support tools using self-report and physiological responses [Ph.D. dissertation, UNC Charlotte]. Available online: https://repository.charlotte.edu/islandora/object/etd%3A1208 (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Choi, G. Y., & Behm-Morawitz, E. (2020). Discovering hidden digital producers: Understanding motivation and creativity in social media production. Psychology of Popular Media, 9(3), 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, A., Smith, D., & Booth, A. (2012). Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qualitative Health Research, 22(10), 1435–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copplestone, T., & Dunne, D. (2017). Digital media, creativity, narrative structure and heritage. Internet Archaeology, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. Harper/Collins. [Google Scholar]

- Cybulski, J. L., Keller, S., Nguyen, L., & Saundage, D. (2015). Creative problem solving in digital space using visual analytics. Computers in Human Behavior, 42, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bono, E. (1992). Serious creativity: Using the power of lateral thinking to create new ideas. Harper Collins. [Google Scholar]

- De Bono, E. (2015). Creatividad. 62 ejercicios para desarrollar la mente. Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- Di Fuccio, R., Ferrara, F., & Di Ferdinando, A. (2020). The docent game: An immersive role-playing game for the enhancement of digital creativity. In E. Popescu, A. Belén Gil, L. Lancia, L. S. Sica, & A. Mavroudi (Eds.), Methodologies and intelligent systems for technology enhanced learning, 9th international conference, workshops (Vol. 1008, pp. 96–102). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgammal, A., & Mazzone, M. (2020). Artists, artificial intelligence, and machine-based creativity in playform. Artnodes, 26, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivias, M. T. (2004). Creatividad: Definiciones, antecedentes y aportaciones. Revista Digital Universitaria, 5(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Feist, G. J. (1998). A meta-analysis of personality in scientific and artistic creativity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 2(4), 290–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Díaz, J. R., Llamas-Salguero, F., & Gutiérrez-Ortega, M. (2019). Creatividad: Revisión del concepto. ReiDoCrea: Revista Electrónica de Investigación y Docencia Creativa, 8, 467–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frich, J., Biskjaer, M. M., & Dalsgaard, P. (2018, April 5–7). Why HCI and creativity research must collaborate to develop new creativity support tools. Technology, Mind, and Society Conference (pp. 1–6), Washington, DC, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frich, J., MacDonald Vermeulen, L., Remy, C., Biskjaer, M. M., & Dalsgaard, P. (2019, May 4–9). Mapping the landscape of creativity support tools in HCI. 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–18), Glasgow, UK. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaigordobil, M. (2003). Intervención psicológica para desarrollar la personalidad infantil: Juegos, conducta prosocial y creatividad. Ediciones Pirámides. [Google Scholar]

- Garaigordobil, M., & Pérez-Fernández, J. I. (2004). Un estudio de las relaciones entre distintos ámbitos creativos. Educación y Ciencia, 8(15), 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Gilhooly, K. J. (2016). Incubation and intuition in creative problem solving. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilford, J. P. (1950). Creativity. American Psychologist, 5(9), 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, M. H., Choi, D. Y., & Lee, K. C. (2013). An empirical analysis of the effect of social and emotional intelligence on individual creativity through exploitation and exploration. In K. C. Lee (Ed.), Digital creativity (Vol. 32, pp. 79–98). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwood, T. (2013). Machinima as a learning tool. Digital Creativity, 24(3), 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisrich, R. D., & Soltanifar, M. (2021). Unleashing the creativity of entrepreneurs with digital technologies. In M. Soltanifar, M. Hughes, & L. Göcke (Eds.), Digital entrepreneurship: Impact on business and society (pp. 23–49). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, J., Ivcevic, Z., & Brackett, M. (2016). Creativity in the age of technology: Measuring the digital creativity of millennials. Creativity Research Journal, 28(2), 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S., Gu, J., Liu, H., & Huang, Q. (2017). The moderating role of social media usage in the relationship among multicultural experiences, cultural intelligence, and individual creativity. Information Technology & People, 30(2), 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivcevic, Z., & Mayer, J. D. (2009). Mapping dimensions of creativity in the life-space. Creativity Research Journal, 21(2–3), 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, P. E. J. (2020). Learning pathways for digitally creative youth: A study of 3D animation [Ph.D. dissertation, University of Roehampton]. Available online: https://pure.roehampton.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/3217463/Learning_pathways_for_digitally_creative_youth.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Kikis-Papadakis, K., & Chaimala, F. (2019). Assessing competences for digital creativity. In O. Miglino, & M. Ponticorvo (Eds.), Proceedings of the First Symposium on Psychology-Based Technologies (PSYCHOBIT 2019) (pp. 1–10). CEUR Workshop Proceedings, 2524. Available online: https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2524/paper5.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Lee, K. C. (2015). Digital creativity: New frontier for research and practice. Computers in Human Behavior, 42, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M. R., & Chen, T. T. (2015). Digital creativity: Research themes and framework. Computers in Human Behavior, 42, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessig, L. (2004). Free culture: How big media uses technology and the law to lock down culture and control creativity. Penguin Press, HC. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letelier, S. S., Manríquez M., J. J., & Rada G., G. (2005). Systematic reviews and meta-analysis: Are the best evidence? Revista Médica de Chile, 133(2), 246–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Kim, M., & Palkar, J. (2022). Using emerging technologies to promote creativity in education: A systematic review. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 3, 100177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveless, A. M. (2002). A literature review in creativity, new technologies, and learning: A report for NESTA Futurelab. NESTA Futurelab. Available online: https://telearn.hal.science/hal-00190439v1/document (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Maiden, N., Zachos, K., Brown, A., Nyre, L., Holm, B., Tonheim, A. N., Hesseling, C., Wagemans, A., & Apostolou, D. (2019, June 23–26). Evaluating the use of digital creativity support by journalists in newsrooms. 2019 Creativity and Cognition Conference (pp. 222–232), San Diego, CA, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, L., Bresciani, S., & Eppler, M. J. (2016). We walk the line: Icons’ provisional appearances on virtual whiteboards trigger elaborative dialogue and creativity. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, A. S., Grygiel, P., & Karwowski, M. (2017). Connected to create: A social network analysis of friendship ties and creativity. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity and the Arts, 11(3), 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, S. L. (2009). Does science need a global language?: English and the future of research. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oropesa, F. N., Pérez, M. C., Molero, M. M., Simón, M. M., Barragán, A. B., Martos, A., Sisto, M., Soriano, J. G., & Gázquez, J. J. (2018). Creatividad digital en educación secundaria: Análisis descriptivo y relacional en función de variables sociodemográficas. In La convivencia escolar, un acercamiento multidisciplinar (Vol. III, pp. 213–220). Asunivep. Available online: http://www.sej473.com/documents/capitulos/capitulo_150.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., & Chou, R. (2021). Declaración PRISMA 2020: Una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Revista Española de Cardiología, 74(9), 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulus, P. B., & Nijstad, B. A. (Eds.). (2003). Group creativity: Innovation through collaboration. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M. D., Godfrey, C. M., McInerney, P., Baldini Soares, C., Khalil, H., & Parker, D. (2015). Methodology for JBI scoping reviews. In E. Aromataris, & Z. Munn (Eds.), Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual (pp. 1–24). The Joanna Briggs Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Fernández, J. I. (1997). Continuación de la investigación de la creatividad. Revista Música Arte Proceso, 4, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Fuentes, M. D. C., Molero Jurado, M. D. M., Oropesa Ruiz, N. F., Simón Márquez, M. D. M., & Gázquez Linares, J. J. (2019). Relationship between digital creativity, parenting style, and adolescent performance. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizzo, A., & Valle, A. (2014). Digital creativity: A survey for the project Invisibilia. Mimesis Journal, 3(2), 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plucker, J. A., Beghetto, R. A., & Dow, G. T. (2004). Why isn’t creativity more important to educational psychologists? Potentials, pitfalls, and future directions in creativity research. Educational Psychologist, 39(2), 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasch, L., Bruch, L. A. D., & Bengler, K. (2022). User needs for digital creativity support systems in an occupational context. In N. L. Black, W. P. Neumann, & I. Noy (Eds.), Proceedings of the 21st Congress of the International Ergonomics Association (IEA 2021) (Vol. 223, pp. 667–674). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RAE. (2023). ROYAL SPANISH ACADEMY: Dictionary of the Spanish language. 23rd ed. [online version 23.8]. Available online: https://dle.rae.es (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Ritter, S. M., & Dijksterhuis, A. (2014). Creativity—the unconscious foundations of the incubation period. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 73722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudowicz, E. (2003). Creativity and culture: A two-way interaction. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 47(3), 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runco, M. A., & Jaeger, G. J. (2012). The standard definition of creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 24(1), 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runco, M. A., & Richards, R. (1997). Eminent creativity, everyday creativity, and health. Greenwood Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Sadler-Smith, E. (2015). Wallas’ four-stage model of the creative process: More than meets the eye? Creativity Research Journal, 27(4), 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salager-Meyer, F. (2008). Scientific publishing in developing countries: Challenges for the future. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 7(2), 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoila, C., Ursutiu, D., Jinga, V., & Kane, P. (2015, September 20–24). Digital creativity peculiarities in the case of remote experiment. 2015 International Conference on Interactive Collaborative Learning (ICL) (pp. 1231–1234), Firenze, Italy. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, R. K. (2012). Explaining creativity: The science of human innovation. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Meca, J. (2022). Revisiones sistemáticas y meta-análisis en educación: Un tutorial. Revista Interuniversitaria de Investigación en Tecnología Educativa, 5, 5–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y. W., & Lee, K. C. (2011, August 12–14). Multi-agent simulation approach for investigating the evolution pattern analysis of digital creativity considering task diversity. 2011 International Conference on Management and Service Science (pp. 1–4), Wuhan, China. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, R. (2010). Taking digital creativity to the art classroom: Mystery box swap. Art Education, 63(2), 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shneiderman, B. (2002). Creativity support tools. Communications of the ACM, 45(10), 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sica, L. S., Ponticorvo, M., & Miglino, O. (2020). Enhancing digital creativity in education: The Docent Project approach. In E. Popescu, A. Belén Gil, L. Lancia, L. S. Sica, & A. Mavroudi (Eds.), Methodologies and intelligent systems for technology enhanced learning, 9th international conference, workshops (Vol. 1008, pp. 103–110). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonton, D. K. (2003). Scientific creativity as constrained stochastic behavior: The integration of product, person, and process perspectives. Psychological Bulletin, 129(4), 475–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sternberg, R. J., & Lubart, T. I. (1996). Investing in creativity. American Psychologist, 51(7), 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, R. J. (Ed.). (1999). Handbook of creativity. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, R. J., Lubart, T. I., Kaufman, J. C., & Pretz, J. E. (2005). Creativity. In K. J. Holyoak, & R. G. Morrison (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of thinking and reasoning (pp. 351–369). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, C., Mao, S., Naumann, S. E., & Xing, Z. (2022). Improving student creativity through digital technology products: A literature review. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 44, 101032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrance, E. (1988). The nature of creativity as manifest in its testing. In R. Sternberg (Ed.), The nature of creativity (pp. 43–73). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., & Hempel, S. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero-Matas, J. A. (2020). La educación en la technoaldea: ¿Privación de la creatividad? Foro de Educación, 18(2), 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallas, G. (1926). The art of thought. Franklin Watts. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, R., Runco, M. A., & Berlow, E. (2016). Mapping the themes, impact, and cohesion of creativity research over the last 25 years. Creativity Research Journal, 28(4), 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagalo, N., & Branco, P. (2015). The creative revolution that is changing the world. In N. Zagalo, & P. Branco (Eds.), Creativity in the digital age (pp. 3–15). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Chen, W., Xiao, Y., & Wang, B. (2022). Exploration of digital creativity: Construction of the multiteam digital creativity influencing factor model in the action phase. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 822649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).