Abstract

The home context can complement formal schooling in writing. However, the family’s potential for promoting how children learn to write is still relatively underexplored, particularly in primary education. The present study used a qualitative approach based on parent focus groups to analyse the practices and support given at home to Spanish primary school students. It also examined the challenges families face and the strategies they suggested for improving their involvement in writing. Focus groups were interviewed involving 32 parents of children in the first (6–8 years old), second (8–10), and third (10–12) cycles of primary education. The results indicate that informal writing practices are carried out at home, related to communication, leisure, and reflection, along with formal writing practices based on supporting schoolwork and stimulating specific writing skills. The formal practices are based on school requirements and children’s needs, while the informal practices are a constant presence throughout primary schooling. The study also identified parental writing support that was instructional (modelling, guiding, explaining, correction), motivational (reinforcement, play, emphasising writing’s importance), and organisational (resources and organisation), which varied as children developed. The families identified challenges to enriching the writing environment at home linked to factors related to the children (lack of motivation, frustration with mistakes, and negative views of writing), to their own availability or lack of knowledge, and to the influence of school and the digital context. Their main suggestions for improvements included improved coordination between school and family and promoting writing experiences based on enjoyment and functionality. Despite the difficulties, the families offered varied writing practices and support that can complement how writing is taught at school.

1. Introduction

The acquisition and mastery of writing is an essential component of people’s cultural and cognitive development in literate societies. The ability to write provides multiple benefits and the skills people need for work, civic participation, personal success, and enjoyment. Knowing how to write effectively is a powerful means of expression and learning, and is a primary objective of education systems all over the world (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO], 2019). However, international research warns that a considerable proportion of the population, including 200 million children, lack appropriate literacy skills, including those related to writing (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO], 2013). In this context, it is essential to have a more thorough understanding of the factors that influence the effective acquisition and development of writing.

Unlike speaking, writing requires specific understanding of a language and structured teaching. The act of writing is a psychological and linguistic process that begins in the family setting, when a child starts to put words into writing, a process that develops and improves throughout schooling. The process of acquiring writing skills is strongly determined by the environment the child grows up in and by the various contextual elements making up that environment, which influence both learning and individual development. Current theoretical socio-cultural models about writing, such as the Writer(s)-within-Community Model of Writing (Graham, 2018), consider learning to write as a complex process that involves cognitive, social, and emotional components.

From a cognitive perspective, writing involves the activation of executive functions and mastery of specific writing skills, such as planning and textual revision (Hayes, 2012; Kellogg, 2008). In parallel with this, the motivational dimension is key. Various studies have shown a positive relation between motivation and writing achievement (Camacho et al., 2021; Ekholm et al., 2018; Graham et al., 2017). Motivation for writing is closely linked to the emotional climate and the perceived importance of tasks, and in this regard, social interactions play a decisive role. A negative emotional environment or a perception of writing activities being meaningless can reduce students’ interest and engagement (Graham, 2018). In this way, motivation and writing development are strongly influenced by contextual variables, especially the writer’s social environment and the support from collaborators or mentors (Graham, 2018), a role often played by the family (Álvarez & Robledo, 2025; Yang & Chen, 2023). Writing therefore not only depends on the learner’s cognitive and intrapersonal abilities, but also on the social context surrounding the act of writing.

From this point of view, writing is conceived of as a social activity, shaped by environmental factors and the interaction between novice and expert writers. Children develop skills and motivation, and undertake writing practices through interacting with adults and other more experienced writers who provide them with scaffolding, modelling, and feedback, allowing them to do tasks that they would not be able to do on their own (Graham, 2018). Because of that, although learning to write needs formal, explicit instruction, generally given at school, it also requires rich, emotionally significant learning contexts (Skibbe et al., 2013). Informal settings, such as the home, can play a fundamental role in promoting motivation and learning writing (Graham, 2018; Hofslundsengen et al., 2019; Nutbrown, 2020; Zurcher, 2016). This means that the formal teaching of writing at school can be enriched by integrating practices from more informal, communicative settings such as the family, where writing is approached in a manner that is more functional, meaningful, and social (Hofslundsengen et al., 2019).

1.1. Family Home Context and Writing

A family’s influence on the process of learning to write is closely associated with the literacy-related environment in the home, understood as the set of practices, interactions, and resources families provide to stimulate reading and writing skills (Morales & Pulido-Cortés, 2023). In this framework, parental involvement in children’s writing is defined as the parents’ behaviours that contribute to the development of children’s writing skills (Yang & Chen, 2023), including writing support activities that have not necessarily been imposed or required by the school (Fox & Olsen, 2014; Ringenberg et al., 2005).

The family environment plays a crucial role in children’s literacy through three main dimensions: interaction, which covers experiences shared between the child and other family members; the physical environment, which includes availability of reading and writing materials in the home; and the emotional and motivational climate, which reflects the parents’ attitudes towards literacy and the family’s educational aspirations (Guevara et al., 2010). Families, together with teachers, form writing communities that support children’s capacity to use writing for various communicative ends (Graham, 2018). As first educators, parents provide the tools, models, and opportunities that children need to translate their ideas into written language (Aram et al., 2020). This means that the literacy-related environment can be considered a key space for the development of writing competency. Nonetheless, and despite its importance, research into writing in the family context is still limited compared to research about reading (Alston-Abel & Berninger, 2018; Camacho & Alves, 2017), although studies have been published in recent years focusing specifically on family involvement in promoting children’s writing. Some work has looked at the preschool or infant education stage, analysing the relationship between the writing environment in the home and the first phases of learning to write. The results show that teaching practices specifically focused on writing skills are positively associated with the development of graphomotor skills (Bindman et al., 2014), handwriting (Gerde et al., 2012; Puranik et al., 2018), and spelling (Guo et al., 2021; Hofslundsengen et al., 2019; Levin et al., 2013; Lin et al., 2012; Puranik et al., 2018). Activities based on everyday, functional use of writing, along with communicative and motivational support, promote children’s initiative, self-confidence, and interest in writing (Leyve et al., 2012; Sparks & Reese, 2013).

In primary education, studies into the role of the family are much less common, despite being the stage when children have to tackle formally learning to write. The few studies looking at this stage include the work by Alston-Abel and Berninger (2018), who interviewed U.S. parents of 1st to 7th grade children, asking about the time they spent on writing activities at home and the nature of those activities (schoolwork or non-schoolwork). The results suggest positive correlations between students’ writing performance and home writing practices. In 1st grade children, home writing practices that were not related to schoolwork were positively related to spelling skills, whereas in the 5th and 6th grades, it was the schoolwork-related practices that were positively related to children’s spelling, punctuation, grammar, and vocabulary. In a similar way, Kelso-Marsh et al. (2025) analysed parental involvement and motivation for supporting writing in children aged 6 to 8 years old. Their results show that when parents were involved in writing activities through their own motivation, based on enjoyment or because they prized learning, their children demonstrated more positive attitudes towards writing as well as producing better quality output.

Looking at the child’s perspective, studies such as Gardner (2013) and Malpique et al. (2023) examined the informal writing practices and support that children in the first few years of primary education received at home. They reported that most of the children took part in at least one informal home writing activity (such as making lists, notes, cards, or stories) and had support from an adult, usually their mothers, which they responded very positively to. More recently Robledo et al. (2025) examined the home writing practices of Spanish children in all primary school years (ages 6 to 12), the perception of the family support received, and the affective responses to it, along with general attitudes towards writing. Their results show that the most commonly undertaken writing practices at home were linked to functional or academic tasks, with significant variation by school year. They also found a perceived reduction in family support for writing in later school years. Nonetheless, the students’ affective responses to this support were positive and stable. They identified positive correlations between the frequency of home writing practices, perceived family support, and favourable student attitudes towards writing.

Recent empirical reviews in the field (Álvarez & Robledo, 2025; Yang & Chen, 2023) have confirmed the positive effect of family involvement in writing on children’s writing competence and motivation towards writing. However, they have also shown notable gaps in our knowledge that limit understanding of the phenomenon. Firstly, most studies have focused on pre-primary or early primary children and have analysed parental involvement only in relation to informal writing activities or basic transcription skills. Consequently, little is known about the types of writing practices—formal or informal—and parental support available in the homes of primary school children, a stage in which children have to make fundamental writing skills automatic and engage in more complex, self-regulated processes of composition (Kellogg, 2008; Limpo & Alves, 2013; Limpo et al., 2014). Furthermore, this stage of schooling coincides with a general fall in motivation towards writing (Camacho et al., 2021; Ekholm et al., 2018; Graham et al., 2017), which increases the risk of children not developing adequate writing skills. Because of that, it is essential to understand what contextual variables, and particularly what forms of family involvement influence learning and motivation to write in primary school children in order to guide educational practice.

Another notable limitation of the existing research is a lack of precision in both conception and field methodology. Studies have often not clearly defined the types of practices, behaviours, or family support they assessed, making it difficult to define a construct of family involvement in writing. While the wider field of family literacy can count on more consolidated theoretical frameworks, such as the Home Literacy Model (Sénéchal, 2006; Sénéchal & LeFevre, 2014), these have almost exclusively been developed for reading, without any systematic translation to writing mastery. This means that progress needs to be made in the conceptualisation of the home writing environment and in the identification of the specific mechanisms through which families encourage children to learn writing in the home.

At the methodological level, the predominance of questionnaires as the sole source of data has limited exploration of the qualitative dimensions of the home writing environment. This tendency has restricted understanding of the phenomenon to a superficial quantitative level, making it harder to capture the wide range of family behaviours that define family involvement in writing, the context in which it is done, and the support strategies put in place. In addition, there has been little exploration of the difficulties families face when they get involved in their children learning to write, or in the strategies that they use to deal with those difficulties or improve their involvement. Taken together, the gaps in our knowledge in this area of study demonstrate the need for qualitative research that will help provide a deeper understanding of how families promote and support writing during primary education, a time when the formal teaching of writing becomes fundamentally important and when family support can play a decisive role.

1.2. Present Study

These considerations suggest the need for a deeper qualitative understanding of primary students’ home writing environments. The objective of the present study is to explore this environment in response to the research question: What is the home writing environment like for primary school students? To do this, we used parent focus groups as the methodological tool, in order to obtain qualitative information that would allow a thorough understanding of what families naturally do in relation to writing and promoting learning to write. The focus groups, based on semi-structured interviews on a defined topic, encouraged the expression of attitudes, beliefs, and experiences, prompting interaction between participants, allowing the participants’ observations and comments to lead to diverse responses and enrich the information collected (Escobar & Bonilla-Jimenez, 2017).

The general objective of this study is to describe the home writing environment in Spanish primary school students, from 1st to 6th grades (ages 6 to 12), through parent focus groups. This approach will help to address the following specific objectives:

- Identify, describe, and classify writing practices in the homes of primary school students. The expectation is to create a classification of home writing practice types, similar to the one produced in the empirical theoretical reading field by the Home Literacy Model (Sénéchal, 2006; Sénéchal & LeFevre, 2014). That model splits the home literacy environment into two dimensions, the formal and the informal. The informal dimension includes experiences and activities in which children are passively or incidentally exposed to written language, where the communicative function—the message—is the focus of attention. In the formal dimension, the focus is on the written material itself and how it is configured or structured. In this case, the children are more active, and the parents take on a more formal teaching role.

- Identify, describe, and classify the type of writing support families provide when they participate in children’s home writing activities. The expectation is to systematise and organise the types of writing activities families do, identifying both instructional support—that is specific and linked to writing skills—and motivational or contextual support, in line with the more general work in the field of literacy (Aram et al., 2020; Sénéchal et al., 2017; Krijnen et al., 2020). We expect to find variation in both writing practices and family support related to the children’s school year and their associated level of writing development (Alston-Abel & Berninger, 2018; Robledo et al., 2025).

- Understand the challenges and difficulties families face when involving themselves in their children learning to write, along with strategies and processes for improving their involvement and dealing with challenges. In this case, we expect that those difficulties and the strategies they suggest will be linked to parental characteristics (Aram & Levin, 2011; Herrera & Guayana, 2022; Orellana et al., 2025), emotional and ability-related aspects in the children (Santangelo, 2014), and aspects linked to the family’s socio-school context (Luna et al., 2019; Penderi et al., 2023).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

Participants (parents) were selected for the focus groups based on non-probabilistic, systematic sampling, commonly used in qualitative research (Prieto & March, 2002). This type of sampling allows a structural sample to be selected that includes specific groups of people whose profiles are typical of the reference population they represent. More specifically, in this study, the structural sample was made up of parents of children in primary school (from 1st to 6th grades) who were involved or responsible for their education. The characteristic defining the typical profile of the subjects of interest for this study was that they were parents (mother or father) of students in primary education in a Spanish school who were responsible for the students’ education and therefore actively involved in it. In addition, the variable used to segment the study population, for research purposes, was the cycle of primary education these students were in during the 2023/24 school year.

The sample was divided into three segments, resulting in three focus groups: Group 1 consisted of parents of students in the first cycle of primary education (1st or 2nd grade, 6–8 years; n = 8), Group 2 was parents of students in the second cycle of primary education (3rd or 4th grade, 8–10 years; n = 8), and Group 3 was parents of students in the third cycle of primary education (5th or 6th grade,10–12 years; n = 16). This variable (phase or cycle of primary education) was chosen because the academic or formal writing tasks required in the Spanish curriculum by law differ between cycles, and the development or acquisition of writing skills varies with age. In earlier years, the tasks are associated with the acquisition of transcription skills, while more complex self-regulation processes are gradually acquired. Moreover, students’ motivation towards writing tends to be higher in earlier grades. All these factors are assumed to affect parental involvement in writing and the support and writing practices in the home.

The sample of parents was selected via a mixed, three-stage process. Firstly, potential participants were identified for the samples through key informants (form tutors, school management team members, or parent-teacher association members) who, by experience or contact with the study population, had the information necessary to select participants who would fit the previously defined profile. Secondly, the focus groups were set up considering their internal composition. The aim was to have focus groups that were internally homogeneous so that the participants’ interactions and opinions could be discussed and expanded on based on other participants’ views and perspectives (Krueger & Casey, 2015; Litosseliti, 2003). The criteria considered for this were: (i) that the parents in each focus group had children in the same cycle of primary education (first, second, or third); (ii) that the parents used Spanish as their primary language for communication; (iii) that the students attended schools in Spain, regulated by common educational standards; and (iv) that the schools used Spanish as their target language.

Following initial identification and contact with 45 families, a total of 32 parents (based on availability) were able to participate in the focus groups. Most of the participating parents were mothers, which is commonly the case in studies about literacy and the family (Álvarez & Robledo, 2025; Aram, 2010). Their characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of the sample of parent participants in focus groups.

Although families met the previously defined homogeneity criteria, there was heterogeneity in certain variables that enriched the focus groups, providing a more diverse range of perspectives, experiences and motivations. These variables included parental gender, age and educational background (see Table 1), as well as the children’s gender and the type of school they attended (public or independent, rural or urban). These factors are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Description of the children in the sample.

2.2. Instrument

Data were collected via semi-structured interviews with the parent focus groups. The aim of the interview was to gather information on primary school students’ home writing environments.

The interview script was developed by experts in writing and family engagement (authors) following a three-phase process. The first phase involved creating an initial interview script, structured around a matrix of 5 content blocks and 15 potential thematic questions, based on the study objectives and grounded in theoretical and empirical knowledge in the scientific field of family literacy and writing. In the second phase, the interview script was reviewed by experts, allowing a pilot validation (Krueger & Casey, 2015). Three experts in the field of writing and family literacy and four families participated in this phase. They provided feedback on the initial script as well as suggestions for improvement. Based on their recommendations, in the third phase, the initial script was rewritten, keeping the five content blocks but reducing the 15 potential questions to 7 specific thematic questions. These questions were complemented by 9 additional support or follow-up questions aimed at clarifying, redirecting, or fostering discussion if needed (Cameron, 2005)—given that this was a semi-structured interview designed for use in focus groups. The questions were evaluated by 9 experts in the field of writing and families in terms of several criteria: coherence (alignment between the questions and the intended measures), relevance (how the questions related to the interview objectives), and clarity (whether the questions were clear, easily understood, and appropriately phrased in terms of syntax and terminology). This produced a content validity coefficient (CVCtc) = 0.920, which indicates excellent content validity (Hernández-Nieto, 2002).

The interview questions (see Table 3) were organised following Cohen et al. (2018), beginning with general topics on parental attitudes toward writing and gradually introducing the specific issues of primary interest in the study, concluding with final reflections on the challenges families face supporting writing at home and proposing strategies to overcome them. The five thematic blocks were: (1) general perception of writing, (2) informal writing practices at home, (3) formal writing practices at home, (4) support families give children during writing activities at home, and (5) general reflections. Blocks 2 and 3 aimed to identify what types of formal practices (related to direct teaching of writing skills) and informal practices (associated with routine or everyday activities involving writing) occurred in the children’s homes. Block 4 focused on understanding the types of support families give students when they write at home. Blocks 1 and 5 were intended to open and close the interview, identifying the challenges families face in promoting writing practices at home and offering support, as well as strategies for overcoming these challenges.

Table 3.

Semi-structured interview script.

In addition, the participating parents completed a sociodemographic questionnaire to provide information about their child, including date of birth, gender, school year, and any potential learning difficulties (no writing difficulties in the children were reported). The questionnaire also gathered data about the people who regularly lived with the child, such as gender, age, educational attainment, and professions.

2.3. Design and Procedure

A qualitative study was conducted using content analysis based on focus groups with families. The focus groups were conducted after contacting key informants from various schools, selecting potential families, and obtaining informed consent from the 32 parents participating in the study. The three focus group meetings were all held in May 2024. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of León (Spain, code ETICA-ULE-026-2024), within the framework of Project PID2021-1244011-NB-I00, funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation.

The meetings were held online via Google Meet in four separate sessions, one each for FG 1 and FG 2, and two for FG 3 (due to the number of participants, the interview for FG3 was held in two sessions). Each session lasted under two hours, on average around 70 min (Kuhn, 2018; Krueger & Casey, 2015). Two expert researchers (the authors) participated in the focus group interviews, which were audio-recorded. They had been trained beforehand in focus group techniques with families through pilot interview applications. One researcher acted as the moderator for the interviews, following the interview script (which they were very familiar with), guiding family members in turn-taking, and encouraging equal participation from all participants. The other researcher was a non-participant observer, taking notes on the interview and ensuring the script was followed. This approach ensured the validity and reliability of the interviews, following the criteria outlined by Cohen et al. (2018): (a) joint training of researchers in the initial interviews, (b) consistent adherence to the interview process and sequence, and (c) audio recording and note-taking for subsequent transcription.

After the focus group meetings were completed, the data were processed, coded, and analysed.

2.4. Data Analysis

To begin processing and coding the data, interview transcripts were created using the Deepgram platform, followed by a thorough review of the resulting text against the original audio to ensure transcription accuracy. Each speaker was identified by assigning the code “E” to the interviewer and each family member’s first name at the start of their statements.

Content analysis of the interviews was carried out using MAXQDA 24 to create categories and codes. A horizontal coding strategy was used, with the authors analysing each question across all interviews to maximise consistency in results for each item. First, parents’ statements were segmented and their responses were assigned to general categories, based on content blocks of the interviews, guided by the study objectives and theoretical-empirical knowledge in the field. As responses arose requiring new subcategories or specific codes, they were defined as needed. This resulted in a total of 8 general analytical categories and 33 specific subcategories or codes (summarised in Table 4), the identification and description of which make up the qualitative results of the study.

Table 4.

General analytical categories and subcategories.

This mutually exclusive categorisation system was reapplied to all interviews in a total of 2088 segments by the lead author. In addition, 75% of the segments were analysed by the second author to ensure faithful application of the categorisation. Inter-rater agreement was calculated using the Kappa coefficient [(Po − Pc)/(1 − Pc)] at 0.95 (for more detail see Appendix A).

Following the content analysis, the frequency of appearance of the different codes was calculated overall and for each focus group. This makes up the quantitative results of the study.

3. Results

3.1. Types of Home Writing Practices

A qualitative analysis of the focus group interviews identified two general categories of home writing practices, informal and formal, in line with the Home Literacy Model (Sénéchal, 2006; Sénéchal & LeFevre, 2014). Informal practices are where writing is linked to day-to-day, routine activities and experiences in which children are passively or incidentally exposed to written language. These are activities related to everyday socio-communicative, enjoyable, or thinking tasks that involve writing.

Formal writing practices include activities that focus on writing itself, the content, production, or structure. These are practices that are directly related to writing skills or processes in which families usually adopt a formal teaching role because they are mostly related to academic writing activities, taught in the school context. These formal practices are related to the different skills and cognitive processes demanded by writing: transcription (handwriting, spelling), grammatical processes, and processes related to written composition (including textual production, planning and revision). For each of the two general categories of home writing practices, the system of subcategories shown in Table 5 was applied.

Table 5.

Categories and subcategories describing home writing practices.

The results of the quantitative analysis of the frequency at which each subcategory appeared in informal and formal home writing practices are shown in Table 6. In informal practices, the parents most frequently mentioned activities that had a communicative goal, followed by leisure. The least-mentioned practices were those related to thinking or managing thoughts. This pattern was the same when we analysed each focus group independently.

Table 6.

Percentage frequencies of formal and informal practices used by families in the different focus groups.

Looking at the formal home writing practices, the families most commonly mentioned those related to homework and learning, followed by handwriting, composing texts, and spelling, with grammar being the least noted. This pattern was the same when examining focus groups independently for groups 1 and 2, although in both of those groups, composition was mentioned more often than handwriting. In contrast, group 3 made most mention of handwriting practices, followed by homework and then spelling, and in this case text composition and grammar were the least-mentioned subcategories.

3.2. Types of Family Support for Writing

The writing support, assistance, and scaffolding families gave their children at home was classified based on the literature as instructional, motivational, and resource management (Aram et al., 2020; Sénéchal et al., 2017; Krijnen et al., 2020). After analysing the focus group interviews, instructional support can be defined as parental behaviour that is similar to teacher behaviour, focused on giving children instructional or procedural support aimed at written content, and therefore linked to writing skills and processes. This support could be in various formats: grapho-phonemic assistance and help with handwriting, explanations, guidance, correction, and modelling. Motivational support refers to trying to improve children’s interest and motivation towards writing. These may be reinforcement, highlighting how important writing is, and support through play. Lastly, resource management is about the help families give providing physical, technological, or material resources that facilitate or motivate acquisition of writing skills or which serve to organise time and place. Table 7 gives a more detailed description, including examples for each type of support.

Table 7.

Categories and subcategories describing family writing support.

Applying the support categorisation to the data from the focus group interviews showed that overall, the most common family support with writing was instructional and motivational, followed by organisational support. This pattern was repeated in focus groups 2 and 3, while in group 1, motivational support was the most used, followed by instructional support (for more detail see Table 8).

Table 8.

General quantitative results related to type of support.

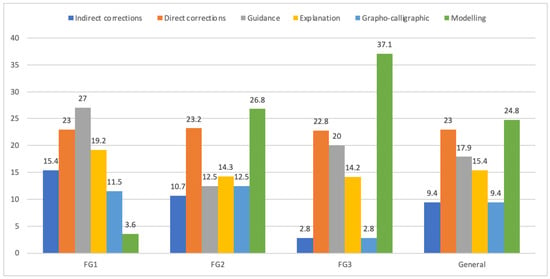

Looking specifically at instructional support, in general (see Figure 1), modelling and direct correction were the most often mentioned, followed by guidance and explanation. Indirect correction and handwriting support were mentioned at a similar, lower frequency. Looking at each focus group independently, only group 3 followed the same pattern. In group 2, modelling and direct correction were the most commonly mentioned support, followed by explanations and then, at a similar frequency, guidance and handwriting help. This group made least reference to indirect correction. Group 1 exhibited a different pattern, mainly referring to guidance, followed by direct correction, explanations and indirect correction, with handwriting help being the support they mentioned least.

Figure 1.

Frequency of appearance of different types of instructional support overall and in each focus group.

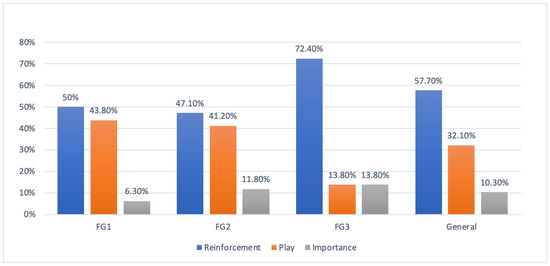

The most commonly mentioned motivational support (see Figure 2) overall was reinforcement, followed by play and then emphasising the importance of writing. This pattern was relatively stable in each focus group. However, in group 1 and 2 play and reinforcement were mentioned a similar amount, whereas emphasising how important writing is was only mentioned very infrequently. In contrast, in group 3, reinforcement was significantly more commonly mentioned (72%) than play or the importance of writing, both of which appeared similarly often (13%).

Figure 2.

Frequency of appearance of different types of motivational support overall and in each focus group.

Finally, looking specifically at the organisational support subcategories, resources were most commonly mentioned overall (88.5%) compared to help with time or space (11.5%). The same pattern was repeated in each focus group (GF1: Resources = 81.8% vs. Time and space = 18.2%; GF2: Resources = 66.7% vs. Time and space = 33.3%; GF3: Resources = 100% vs. Time and space = 0%).

3.3. Difficulties Families Face Involving Themselves in Writing and Strategies for Improvement

Families faced various challenges, difficulties, and obstacles when implementing writing support and practices. Analysing the responses in the focus groups led to these challenges being classified in terms of the dimensions they arose in: the child, social-school variables, and parental variables. Table 9 provides an explanation.

Table 9.

Classification of challenges families face when getting involved in writing at home.

Looking at the quantitative results, as Table 10 shows, the main challenges the families noted in relation to home writing practices and support were related to the children themselves, such as a lack of motivation to write and being frustrated by their own writing difficulties, followed by children’s perceptions about writing, and digitalisation. The parents made much less reference to difficulties related to the school environment, parental supervision and assistance, parents’ availability and time, or their lack of knowledge. The least frequently mentioned challenges were related to a lack of parental interest.

Table 10.

Frequencies of categories of difficulties arising through family involvement in home writing practices.

Looking at each group separately, children’s lack of motivation was the most common category in all of the focus groups, particularly in group 3. In this group, parents also frequently mentioned challenges related to socio-school variables and a lack of parental knowledge about helping children’s writing. The remaining categories came up less frequently, and no one in this group mentioned a lack of parental interest. In group 2, 40% of the comments in this category were related to children not being motivated or being frustrated, followed by comments related to the children’s views about writing. Challenges related to the socio-school and family contexts made up around 10%, with lack of parental knowledge or interest being mentioned least (less than 5%). Finally, in group 1 the parents most commonly noted challenges related to children not being motivated to write, followed by their frustration, their feelings about writing, and digitalisation. The other challenges were mentioned less often (7.1%).

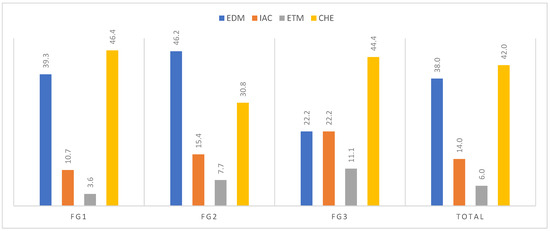

Lastly, the families suggested various strategies to improve writing in the home and dealing with the challenges arising from their involvement in it. These were: (1) Strategies focused on enjoying writing and motivating children to do it (EDM), prompting children to think of writing as an enjoyable, gratifying activity, encouraging their interest, enjoyment, and perseverance with it; (2) Strategies aimed at incorporating writing into everyday activities (IAC), including writing in routine tasks in the home so that children see it as a useful, practical everyday tool; (3) Strategies aimed at finding a balance between technology and writing by hand (ETM), taking advantage of digital resources to facilitate handwritten activities; (4) Strategies related to collaboration between the school and the family (CHE), aimed at promoting open communication between parents and teachers to properly align educational strategies, ensuring consistent support between the two and encouraging family involvement. Table 11 shows some examples given by the families.

Table 11.

Suggested strategies for improving the promotion of writing at home and dealing with challenges.

In terms of quantitative results, as Figure 3 shows, the majority of the strategies parents suggested for improving home writing or dealing with challenges were related to collaboration with the school and focusing on enjoying writing, followed by including writing in everyday activities. The least mentioned were related to the balance between technology and writing by hand. The pattern was the same in focus groups 1 and 3 individually, whereas in group 2, enjoyment of writing was mentioned more than the other categories.

Figure 3.

Frequencies of strategies suggested by the families for improving writing at home.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The main objective of this study was to describe the home writing environment of Spanish primary school students (1st to 6th grades, ages 6–12 years old) through parent focus groups. The study examined the types of home writing practices carried out and the support families offered, as well as the challenges they faced when they involved themselves with their children’s writing, and the strategies they suggested to improve that. Based on the results, our conclusions are as follows.

4.1. Primary School Students’ Writing Practices at Home

The home writing practices of primary school students include both informal and formal activities, as initially hypothesised (Sénéchal, 2006; Sénéchal & LeFevre, 2014). The informal practices the families noted were about writing activities associated with everyday communicative, play, or reflective contexts. The parents frequently spoke about communicative practices, aimed at transmitting or remembering information by writing. They also spoke, albeit less frequently, about using writing as a resource for entertainment or enjoyment. They made less mention of informal practices related to managing thoughts or emotions through writing. These practices occurred similarly between the different focus groups, and there were no significant differences based on children’s school year. We can conclude that families recognise the diverse potential of writing as a means of communication and socio-emotional expression, and that they encourage writing for a range of purposes, regardless of their child’s educational level. This is a particularly important aspect from a motivational point of view, as these kinds of practices encourage children to understand the different uses of writing and help them to develop a positive attitude towards learning to write (Gardner, 2013; Leyve et al., 2012; Malpique et al., 2023; Sparks & Reese, 2013).

Formal writing practices are associated with explicit teaching of writing skills and processes (handwriting, spelling, grammar, and composition) and may be associated with school writing tasks or not. In this case, the results indicate that in the homes the study looked at, formal practices were mainly related to homework and reinforcing writing learned in school. This reflects families’ interest in following their children’s formal learning of writing in the school. However, they also carried out specific writing practices that were not linked to schoolwork, focused on handwriting, text composition, and spelling, with grammar being mentioned least often. This indicates that various types of formal home writing practices are carried out, associated with different writing processes and skills, resulting from schoolwork or otherwise. In this case, there was some variability in the types of formal home writing tasks based on the children’s school year. Surprisingly, parents of children in later school years (5th and 6th grades) often talked about handwriting practice, when handwriting should really be something children have already assimilated by this time (Limpo et al., 2014). This suggests that the families see a need to continue improving this ability (Alston-Abel & Berninger, 2018). It was also notable that practices related to composing texts were more commonly mentioned in earlier school years than later. It is likely that in the homes of children in the first few years of primary school, there are practices linked to story texts, a structure that parents would be very familiar with from children’s books (Read et al., 2021).

As a whole, the results indicate that Spanish families engage in a variety of formal writing practices in the home and tailor them to both demands of the children’s schooling and their development and needs as writers. Informal home writing practice is also diverse, and continues throughout primary education.

4.2. Family Support for Children’s Writing

The results indicate that families give their children various types of support with writing at home: instructional, motivational, and organisational, as suggested in our starting hypothesis (Aram et al., 2020; Sénéchal et al., 2017; Krijnen et al., 2020). The instructional support families mentioned included parental behaviours aimed at giving children support linked to writing skills and processes. Support could be classified as grapho-phonemic, handwriting, explanation, guidance (family members guiding children during writing tasks, providing information, instruction, or direction to the student about writing-related content or procedures), modelling (family members modelling writing procedures or giving examples of correct writing procedures so the children learn by imitation), direct correction of errors (family members correct writing mistakes directly without requiring the child to think about it), and indirect correction (family members guide the child in identifying and correcting their own mistakes). The quantitative results of the study indicate that, although there was some variability by school year, modelling and direct correction of errors were the types of support that the families mentioned most often, followed by guidance and explanation. These types of support are key in formal writing teaching programs (Robledo & García, 2017), which is why families doing them in the home naturally is a positive finding. It is also worth noting that the use of indirect correction was the type of support that families mentioned least. Perhaps this kind of support is the least effective in the families’ eyes, as it needs children to have the cognitive abilities for revising their writing that develop relatively late (Cuenat, 2023; López et al., 2019; Limpo et al., 2014). This would explain it not being mentioned much. It is also worth noting that focus group 1 had a different pattern to the other two groups in terms of the instructional support given to the children. In group 1, the least mentioned support type was modelling. Modelling’s effectiveness in teaching writing skills and processes has been widely confirmed in primary education (Fidalgo et al., 2011; Fidalgo et al., 2025), including in the context of teaching programmes aimed at promoting mechanical skills learning in early years (Jiménez et al., 2023). Despite this, it seems as though the parents of younger primary school children do not use this type of support. This indicates that they may need some specific training that would give them knowledge and procedural tools about using modelling, as the potential of parents applying modelling in teaching writing—after getting systematic guidance and training—has been empirically demonstrated (Arrimada et al., 2022; Robledo & García, 2013).

Motivational support is aimed at improving students’ interest and motivation about writing, generally in the form of reinforcement, highlighting how important writing is, and writing support in the form of play. The quantitative results indicate that the parents most often mentioned reinforcement in the focus groups, although they also spoke about using play as a motivating element and emphasising the importance of writing. There were slight differences related to children’s school years in the latter two types of support. The use of play diminished as the children got older, and the emphasis on how important writing is increased. Motivational support is aimed at improving student interest and motivation, which is key in primary education, when there is a notable drop in children’s motivation to write (Camacho et al., 2021; Ekholm et al., 2018; Graham et al., 2017). Because of that, family strategies should be promoted that continue the different types of motivational support throughout schooling, and that may require training. Systematic instructional studies have shown that families with proper training can be key motivational agents for primary school children’s writing development (Camacho & Alves, 2017).

Lastly, organisational support refers to families giving children the material resources, and organising time and space to help them acquire writing skills. The resources that families provided included physical materials such as lined paper, pens, notebooks and graphic organizers; as well as digital resources such as writing software or learning applications and interactive digital tools (voice dictation, spell checker, etc.). They were relatively constant, particularly the material support, in the homes examined in the study.

4.3. Challenges in Family Involvement in Writing and Strategies for Improvement

The results of the study confirmed that the challenges families face when getting involved in their children’s writing development, and the strategies they suggested for overcoming those challenges and improving their involvement, were associated with three dimensions: (a) child-related variables (lack of motivation, frustration with difficulties, and negative views of writing); (b) family-related variables (supervision, availability of time, parental knowledge and interest); and (c) social-school factors (digitalisation and school practices). The main challenges that families mentioned in relation to home writing tasks were children’s resistance or lack of motivation for writing and their frustration when they carry out writing tasks, linked to negative views of writing, along with digitalisation. The challenges that families mentioned least were related to lack of parental interest. Although the pattern was relatively consistent across the three focus groups, group 3 highlighted challenges related to social-school variables, such as the influence the school environment’s practices and attitudes towards writing on the one hand, and a lack of parental knowledge and skill to help their children in complex writing tasks on the other hand (Orellana et al., 2025). Despite that, the families were aware of strategies that could improve their involvement with their children’s writing and overcome the challenges they face. They indicated a need to improve collaboration with the school, promoting open communication that would allow the alignment of educational strategies between the two contexts (Luna et al., 2019; Penderi et al., 2023). Nonetheless, we must bear in mind that writing is influenced by social and family culture (Graham, 2018). Families’ cultural differences may be evident in differences in family writing involvement. Positive parental beliefs about childhood writing, as well as higher socio-cultural levels may contribute to richer, more stimulating family writing environments (Álvarez & Robledo, 2025). This means that it would be interesting for future studies to also examine the modulating effect of family socio-cultural level on the writing practices undertaken at home.

Families also highlighted the importance of children seeing writing as an enjoyable activity that was part of everyday life, as well as the importance of balancing the use of digital tools with writing by hand. Digital writing contexts are becoming increasingly common, and may influence children’s writing development, although this seems to be mediated by the families’ socio-cultural characteristics (Moreno-Morilla et al., 2018; Yuan et al., 2024). Because of this, there needs to be a deeper examination in the future about how technology can change the dynamics of family writing support.

4.4. General Conclusions, Limitations, and Implications

Overall, the results of the study suggest that the family environment is a key context in the development of writing during primary education, as families produce various opportunities for children to tackle both formal and informal writing practices, tailored to their progress and school requirements. The informal practices, which occur throughout primary schooling, promote functional, communicative, and enjoyable use of writing, and encourage positive attitudes towards it. The formal practices reflect the families’ commitment to reinforcing school learning and consolidating writing skills. The support that families offer combine instructional, motivational, and organisational strategies, with instructional strategies being essential to guide learning processes and motivational strategies being key to sustaining children’s interest at a time when motivation towards writing tends to drop. Nonetheless, the families recognised challenges when improving the home writing environment, associated with factors related to the children, to their own availability or lack of knowledge, and to the influence of the school and digital environment. Their main suggestions for improvement were to enhance coordination between school and the home and to promote meaningful experiences that combine enjoyment and functionality of writing, bearing in mind the wide range of physical and digital media available nowadays. In short, the findings show the active and potentially stimulating role families play in primary school students learning to write, and the need to strengthen their participation through policies and programs that promote sustained collaboration between school and family contexts. Spanish government policies about literacy support the family’s role in education and encourage their active involvement in their children’s teaching–learning processes (Robledo & García, 2021). More specifically, in relation to writing, the legal regulations explicitly state that public education authorities must develop educational literacy plans that include direct collaboration with families (LOMLOE, 2020).

Nevertheless, the results and conclusions of this study should be interpreted with caution, given its limitations, mainly related to the sample. This comprised 32 Spanish parents, allowing for a thorough, contextualised analysis of the home writing environment, suitable for a qualitative focus-group based approach, but something that limits the possible generalisation of results. In addition, most of the focus group participants were mothers, which is very common in studies related to analysing the family context and child literacy (Álvarez & Robledo, 2025; Aram, 2010). It also indicates that mothers seem to take on more responsibility in this area of child rearing. However, this may also have produced a certain gender bias in the study’s results. It would be advisable for future studies to try and achieve greater participation from fathers in order to gain their perspectives on children’s learning to write and encouraging it in the home.

Despite that, this is the first study we have identified internationally that offers qualitative data on the family or home writing environment in primary school students. This means that it is a starting point for future research. From this study’s findings and the system for categorising families’ home writing practices, support, challenges, and improvement strategies, it will be possible to design larger data collection questionnaires that will provide a much broader knowledge of family involvement in writing and allow for a more generalisable characterisation of primary school student’s home writing contexts. It would also be interesting to replicate this study including families of students with specific learning difficulties, as well as focus groups with children to include their perspectives and determine whether there is a different pattern of family involvement or home writing dynamic. Another potential line of study would be to link data from the family writing context to student indicators of performance and writing motivation, applying mixed methodologies and considering the sociocultural diversity of homes and students.

In any case, from a theoretical-empirical perspective, this study increases our knowledge of family literacy in the specific area of writing, an area that has been historically less explored than reading, and contributes to the development of sociocultural models of writing and family involvement in education. In addition, on a practical level, the results allow us to identify families’ training needs in terms of writing support, and to recognise their strengths, offering a basis for designing parental guidance and training programs to enrich the home literacy environment, in the specific case of writing.

In this regard, although the writing practice and support that families naturally give their children every day in the home may contribute to their motivation and learning to write (Álvarez & Robledo, 2025), parents do seem to need some training or education that could help them overcome the challenges that hinder their involvement. Studies about systematic family interventions for writing suggest some recommendations for the design of family programmes. Such programmes should include sessions in which specialists provide tools for assessing, modelling, and supporting children’s writing. In other words, parents need explicit education in how to support the development of children’s writing habits through scaffolding, structured tasks, and practical activities (Aram & Levin, 2014). These training programmes should also include structured parent–child interaction sequences, along with strategies for parents to use to encourage and motivate children’s written production (Camacho & Alves, 2017; Roberts & Rochester, 2021; Robledo & García, 2013).

Families also need specific support materials, such as structured activity books, that give them practical resources and examples of day-to-day use of writing in the home. In any case, families need clear instruction in order to apply the material at home, with support and ongoing follow-up from specialists. The programmes should also help families to recognise their role and importance as facilitators of their children learning to write (Aram & Shachar, 2024; Camacho & Alves, 2017). Similarly, it would be useful for parents to be able to share their experiences with other families and professionals, consider the effects of parent feedback and explore additional strategies that will promote their involvement in writing.

In summary, family programmes must include training that will give them the skills to be actively involved in their children’s writing, along with continued professional support and assistance that will help address issues and keep them motivated (Aram & Levin, 2014; Robledo & García, 2013). Interventions based on these recommendations will improve the quality and frequency of home writing practices, promote sustained change in family interactions, and produce positive effects on children’s writing performance and motivation (Camacho & Alves, 2017; Robledo & García, 2013; Ruan et al., 2023).

In conclusion, this study is an essential starting point for advancing our understanding of the role of the family environment in the development of primary school children’s writing competence. Its findings indicate the importance of considering the home as a complementary space to school in promoting writing, and the need to promote programmes for school-family collaboration that facilitate the teaching–learning process for writing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation P.R., C.R.; methodology, P.R., C.R., and L.A.-D.; validation, P.R. and L.A.-D.; formal analysis, P.R. and L.A.-D.; investigation, P.R. and L.A.-D.; resources, P.R.; data curation, P.R. and L.A.-D.; writing—original draft preparation, P.R., C.R. and L.A.-D.; writing—review and editing, P.R. and C.R.; visualisation, P.R. and L.A.-D.; supervision, P.R.; project administration, P.R.; funding acquisition, P.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by MINISTERIO DE CIENCIA E INNOVACIÓN (SPAIN) and FEDER (EUROPE), grant number PID2021-124011NB-I00, MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/FEDER, UE.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of León (Spain) (code ETICA-ULE-026-2024) on 9 April 2024, within the framework of Project PID2021-1244011-NB-I00, funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, under request to the corresponding author, without undue reservation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

The authors, blinded and independently, coded 75% of the segments according to mutually agreed coding definitions. Subsequently, the level of inter-rater agreement was calculated, giving a Kappa coefficient = 0.95; see Table A1 for more detail.

Table A1.

Percentage agreement for each code and the codes overall.

Table A1.

Percentage agreement for each code and the codes overall.

| Code | Agreement | Disagreement | Coded Segments | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organisational support (MG) | 54 | 0 | 54 | 100.00 |

| MG-O | 6 | 0 | 6 | 100.00 |

| MG-R | 44 | 2 | 46 | 95.65 |

| Motivational support (MS) | 140 | 8 | 148 | 94.59 |

| MS-P | 44 | 3 | 47 | 93.62 |

| MS-I | 14 | 1 | 15 | 93.33 |

| MS-R | 84 | 3 | 87 | 96.55 |

| Instructional support (IS) | 158 | 4 | 162 | 97.53 |

| IS-IC | 20 | 1 | 21 | 95.24 |

| IS-DC | 50 | 6 | 56 | 89.29 |

| IS-G | 38 | 3 | 41 | 92.68 |

| IS-E | 28 | 4 | 32 | 87.50 |

| IS-M | 50 | 5 | 55 | 90.91 |

| IS-GC | 18 | 2 | 20 | 90.00 |

| Formal practices (FP) | 184 | 12 | 196 | 93.88 |

| FP-LH | 80 | 6 | 86 | 93.02 |

| FP-TC | 34 | 3 | 37 | 91.89 |

| FP-G | 6 | 0 | 6 | 100.00 |

| FP-S | 30 | 1 | 31 | 96.77 |

| FP-H | 46 | 1 | 47 | 97.87 |

| Informal practices (IP) | 194 | 6 | 200 | 97.00 |

| IP-R | 44 | 4 | 48 | 91.67 |

| IP L | 46 | 2 | 48 | 95.83 |

| IP-C | 104 | 5 | 109 | 95.41 |

| Total | 1516 | 82 | 1598 | 94.87 |

| Kappa index Calculation | Rater 1 | |||

| 1 | 0 | |||

| Rater 2 | 1 | a = 1516 | b = 28 | 1544 |

| 0 | c = 54 | 0 | 54 | |

| 1570 | 28 | 1598 | ||

Note. Kappa = (Po − Pc)/(1 − Pc). P(observed) = simple agreement percentage = Po = a/(a + b + c) = 0.95. P(chance) = probability of agreement = Pc = 1/Number of codes = 1/24 = 0.04. a = number of codes in agreement. b and c = not in agreement.

References

- Alston-Abel, N. L., & Berninger, V. (2018). Relationships between home literacy practices and school–achievement: Implications for consultation and home–school collaboration. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 28(2), 164–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aram, D. (2010). Writing with young children: A comparison of paternal and maternal guidance. Journal of Research in Reading, 33(1), 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aram, D., & Levin, I. (2011). Home support of children in the writing process: Contributions to early literacy. In S. Neuman, & D. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook of early literacy (Vol. 3, pp. 189–199). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aram, D., & Levin, I. (2014). Promoting early literacy: The differential effects of parent-child joint writing and joint storybook reading interventions. In R. Chen (Ed.), Cognitive development: Theories, stages and processes and challenges (pp. 189–212). Nova Science Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Aram, D., & Shachar, C. A. (2024). “Let’s write each other messages”: Association between involvement in writing in a preschool online forum and early literacy progress. Early Education and Development, 35(3), 511–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aram, D., Skibbe, L., Hindman, A., Bindman, S., Atlas, Y. H., & Morrison, F. (2020). Parents’ early writing support and its associations with parenting practices in the United States and Israel. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 66(4), 392–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrimada, M., Torrance, M., & Fidalgo, R. (2022). Response to intervention in first-grade writing instruction: A large-scale feasibility study. Reading and Writing, 35, 943–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, C., & Robledo, P. (2025). A systematic review of family involvement in school-aged children’s writing [Manuscript submitted for publication]. Department of Mechanical, Computer and Aerospace Engineering, University of Leon; Department of Psychology, Sociology and Philosophy, University of Leon. [Google Scholar]

- Bindman, S. W., Skibbe, L. E., Hindman, A. H., Aram, D., & Morrison, F. J. (2014). Parental writing support and preschoolers’ early literacy, language, and fine motor skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29(4), 614–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, A., & Alves, R. A. (2017). Fostering parental involvement in writing: Development and testing of the program cultivating writing. Reading and Writing, 30(2), 253–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, A., Alves, R. A., & Boscolo, P. (2021). Writing motivation in school: A systematic review of empirical research in the early twenty-first century. Educational Psychology Review, 33(1), 213–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, J. (2005). Focussing on the focus group. In H. Iain (Ed.), Qualitative research methods in human geography (pp. 156–174). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, L., Lawrence, M., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cuenat, M. (2023). Development of writing abilities across languages and school-levels: Room descriptions produced in three languages at primary and secondary school. European Journal of Applied Linguistics, 11(1), 132–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekholm, E., Zumbrunn, S., & DeBusk-Lane, M. (2018). Clarifying an elusive construct: A systematic review of writing attitudes. Educational Psychology Review, 30(3), 827–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, J., & Bonilla-Jimenez, F. (2017). Grupos focales: Una guía conceptual y metodológica. Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos de Psicología, 9(1), 51–67. [Google Scholar]

- Fidalgo, R., López, P., Torrance, M., & Robledo, P. (2025). Strategy-focused writing instruction in upper-primary school: What are the effective contents and components [Manuscript submitted for publication]. Department of Psychology, Sociology and Philosophy, Faculty of Education, University of León; Department of Psychology, School of Social Sciences, Nottingham Trent University; Departmento de Psicología, Sociología y Filosofía, Facultad de Educación, Universidad de León. [Google Scholar]

- Fidalgo, R., Torrance, M., & Robledo, P. (2011). Comparación de dos programas de instrucción estratégica y autorregulada para la mejora de la competencia escrita. Psicothema, 23, 672–680. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, S., & Olsen, D. (2014). Education capital: Our evidence base defining parental engagement. Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth. Available online: https://researchportalplus.anu.edu.au/en/publications/education-capital-our-evidence-base-defining-parental-engagement/ (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Gardner, P. (2013). Writing in context: Reluctant writers and their writing at home and at school. English in Australia, 48(1), 71–81. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/290304924_Writing_in_Context_Reluctant_Writers_and_Their_Writing_at_Home_and_at_School (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Gerde, H., Skibbe, L., Bowles, R., & Martoccio, T. (2012). Child and home predictors of children’s name writing. Child Development Research, 2012, 748532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S. (2018). A revised writer(s)-within-community model of writing. Educational Psychologist, 53(4), 258–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S., Collins, A. A., & Rigby-Wills, H. (2017). Writing characteristics of students with learning disabilities and typically achieving peers: A meta-analysis. Exceptional Children, 83(2), 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara, Y., Rugerio, J., Delgado, U., Hermosillo, A., & López, A. (2010). Alfabetización emergente en niños preescolares de bajo nivel sociocultural: Una evaluación conductual. Revista Mexicana de Psicología Educativa, 1(1), 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y., Puranik, C., Kelcey, B., Sun, J., Dinnesen, M. S., & Breit-Smith, A. (2021). The role of home literacy practices in kindergarten children’s early writing development: A one-year longitudinal study. Early Education and Development, 32(2), 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J. R. (2012). Modeling and remodeling writing. Written Communication, 29(3), 369–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Nieto, R. A. (2002). Contributions to statistical analysis. Universidad de Los Andes. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, D., & Guayana, T. (2022). Las prácticas lúdicas familiares en el aprendizaje de la lectura y escritura en estudiantes del grado primero. Acta Scientiarum. Education, 44(1), e61343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofslundsengen, H., Gustafsson, J. E., & Hagtvet, B. E. (2019). Contributions of the home literacy environment and underlying language skills to preschool invented writing. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 63(5), 653–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, J. E., De León, S. C., García, E., & Seoane, R. C. (2023). Assesing the efficacy of a Tier 2 early intervention for transcription skills in Spanish elementary school students. Reading and Writing, 36(5), 1227–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellogg, R. T. (2008). Training writing skills: A cognitive developmental perspective. Journal of Writing Research, 1(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelso-Marsh, B., Malpique, A., Davis, H., & Similieana Valcan, D. (2025). Motivation matters: The positive influence of parental involvement on children’s writing outcome. Journal of Writing Research, 17(2), 309–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krijnen, E., Van Steensel, R., Meeuwisse, M., Jongerling, J., & Severiens, S. (2020). Exploring a refined model of home literacy activities and associations with children’s emergent literacy skills. Reading and Writing, 33(1), 207–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R., & Casey, M. (2015). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research (5th ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, G. (2018, May 8). What is the best length for a focus group? Driveresearch. Available online: https://www.driveresearch.com/market-research-company-blog/what-is-the-best-length-for-a-focus-group-qualitative-research-firm/ (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Levin, I., Aram, D., Tolchinsky, L., & McBride, C. (2013). Maternal mediation of writing and children’s early spelling and reading: The semitic abjad versus the European alphabet. Writing Systems Research, 5(2), 134–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyve, D., Reese, E., & Wiser, M. (2012). Early understanding of the functions of print: Parent-child interaction and preschoolers’ notating skills. First Language, 32(2), 301–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limpo, T., & Alves, R. A. (2013). Modeling writing development: The contribution of transcription and self-regulation to Portuguese students’ text generation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(2), 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limpo, T., Alves, R. A., & Fidalgo, R. (2014). Childrens’ high level writing skills: Development of planning and revising and their contribution to writing quality. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(2), 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D., McBride-Chang, C., Aram, D., Shu, H., Levin, I., & Cho, J. (2012). Maternal mediation of Word writing in Chinese across Hong Kong and Beijing. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(1), 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litosseliti, L. (2003). Using focus groups in research. Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- LOMLOE. (2020). Ley Orgánica 3/2020, de 29 de diciembre, por la que se modifica la Ley Orgánica 2/2006, de 3 de mayo, de Educación. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/lo/2020/12/29/3 (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- López, P., Torrance, M., & Fidalgo, R. (2019). The online management of writing processes and their contribution to text quality in upper-primary students. Psicothema, 31(3), 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, H. E., Ramírez, C. Y., & Arteaga, M. A. (2019). Familia y maestros en el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje de la lectoescritura. Una responsabilidad compartida. Revista Conrado, 15(70), 203–208. Available online: https://conrado.ucf.edu.cu/index.php/conrado (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Malpique, A. A., Valcan, D., Pino-Pasternak, D., Ledger, S., & Kelso-Marsh, B. (2023). Shaping young children’s handwriting and keyboarding performance: Individual and contextual-level factors. Issues in Educational Research, 33(4), 1441–1460. Available online: http://www.iier.org.au/iier33/malpique.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Morales, L., & Pulido-Cortés, O. (2023). Alfabetización inicial: Travesías al mundo de la lectura y la escritura. Praxis & Saber, 14(37), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Morilla, C., Guzmán-Simón, F., & García-Jiménez, E. (2018). Literacy practices of primary education children in Andalusia (Spain): A family-based perspective. British Educational Research Journal, 45(1), 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbrown, C. (2020). Writing before school: The role of families in supporting child development. In H. Lewes, D. Myhill, & H. Chen (Eds.), Developing writers across the primary and secondary years: Growing into writing (pp. 40–59). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Orellana, P., Cockerill, M., Valenzuela, M. F., Villalón, M., De la Maza, C., & Inostroza, P. (2025). The influence of home language and literacy environment and parental self-efficacy on chilean preschoolers’ early literacy outcomes. Education Sciences, 15(6), 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penderi, E., Karousou, A., & Papanastasatou, I. (2023). A multidimensional–multilevel approach to literacy-related parental involvement and its effects on preschool children’s literacy competences: A sociopedagogical perspective. Education Sciences, 13, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, M. A., & March, J. C. (2002). Paso a paso en el diseño de un estudio mediante grupos focales. Atención Primaria, 29(6), 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puranik, C., Phillips, B., Lonigan, C., & Gibson, E. (2018). Home literacy practices and preschool children’s emergent writing skills: An initial investigation. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 42, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, K., Mackey, G., & Kucirkova, N. (2021). Shared reading in the digital age: Narrative practices of parents and young children with print and digital books. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 21(4), 798–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringenberg, M. C., Funk, V., Mullen, K., Wilford, A., & Kramer, J. (2005). The test-retest reliability of the parent and school survey (PASS). School Community Journal, 15(2), 121–134. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ794812.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Roberts, K. L., & Rochester, S. E. (2021). Learning through everyday activities: Improving preschool language and literacy outcomes via family workshops. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 23(4), 495–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robledo, P., & García, J. (2013). Strategy instruction for writing composition at school and at home. Estudios de Psicología, 34(2), 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robledo, P., & García, J. N. (2017). Description and analysis of strategy-focused instructional models for writing. In R. Fidalgo (Series Ed. & Vol. Ed.), T. Olive (Series Ed.), K. R. Harris (Vol. Ed.), & M. Braaksma (Vol. Ed.), Studies in writing series: Vol. 34. Design principles for teaching effective writing (pp. 38–65). Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Robledo, P., & García, V. (2021). El papel parental en la LOMLOE tras el incremento de su implicación educativa durante la pandemia. In M. Molero, A. Martos, A. Barragán, & M. Simón (Comps.), Investigación en el ámbito escolar: Un acercamiento multidisciplinar a las variables psicológicas y educativas (Vols. 403–410). Dykinson. [Google Scholar]

- Robledo, P., Real, S., & Álvarez, M. L. (2025). A primary students’ writing attitudes and perceived family support: A socioemotional perspective [Manuscript submitted for publication]. Department of Psychology, Sociology and Philosophy, Universidad de León. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, Y., Ye, Y., & McBride, C. (2023). Effectiveness of parent coaching on the literacy skills of Hong Kong Chinese children with and without dyslexia. Reading and Writing, 37, 1805–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santangelo, T. (2014). Why is writing so difficult for students with learning disabilities? A narrative review to inform the design of effective instruction. Learning Disabilities: A Contemporary Journal, 12(1), 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Sénéchal, M. (2006). Testing the home literacy model: Parent involvement in kindergarten is differentially related to grade 4 reading comprehension, fluency, spelling, and reading for pleasure. Scientific Study of Reading, 10(1), 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sénéchal, M., & LeFevre, J. (2014). Continuity and change in the home literacy environment as predictors of growth in vocabulary and reading. Child Development, 85(4), 1552–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sénéchal, M., Whissell, J., & Bildfell, A. (2017). Starting from home: Home literacy practices that make a difference. In K. Cain, D. Compton, & R. Parrila (Eds.), Theories of reading development (pp. 383–408). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Skibbe, L., Bindman, S., Hindman, A., Aram, D., & Morrison, F. (2013). Longitudinal relations between parental writing support and preschoolers’ language and literacy skills. Reading Research Quarterly, 48(4), 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, A., & Reese, E. (2013). From reminiscing to reading: Home contributions to children’s developing language and literacy in low-income families. First Language, 33(1), 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO]. (2013). The global learning crisis: Why every child deserves a quality education. UNESCO. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000223826 (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO]. (2019). Global education monitoring report 2019: Migration, displacement and education—Building bridges, not walls. UNESCO. Available online: https://www.right-to-education.org/resource/global-education-monitoring-report-2019-migration-displacement-and-education-building (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Yang, H., & Chen, Y. (2023). The impact of parental involvement on student writing ability: A meta-analysis. Education Sciences, 13(7), 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H., Kleemans, T., & Segers, E. (2024). The role of the traditional and digital home literacy environment in Chinese kindergartners’ language and early literacy. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 67(2), 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurcher, M. A. (2016). Partnering with parents in the writing classroom. The Reading Teacher, 69(4), 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]