Eye Tracking Characterization of Algebraic Fraction Simplifications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ET | Eye tracker |

| AOI | Area of interest |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| D | Duration time |

| FC | Fixation count |

| SC | Saccades count |

| RC | Revisit count |

| TTFF | Time to first fixation |

| C | Correct answer |

| IC | Incorrect answer |

References

- Ascencio, R., & Eccius-Wellmann, C. (2019). Desarrollo del sentido estructural en alumnos universitarios mediante el uso de la Teoría de la Variación en el manejo de expresiones algebraicas racionales. Educación Matemática, 31(2), 161–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidoo, J., Adane, M., & Luneta, K. (2020). Solving algebraic fractions in high schools: An error analysis. Journal of Educational Studies, 19(2), 96–118. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, J. L., & Newton, K. J. (2012). Fractions: Could they really be the gatekeeper’s doorman? Contemporary Educational Psychology, 37(4), 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brizuela, B. M. (2006). Young children’s notations for fractions. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 62(3), 281–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G., & Quinn, R. J. (2007). Investigating the relationship between fraction proficiency and success in algebra. The Australian Mathematics Teacher, 63(4), 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, B. T., & Luke, S. G. (2020). Best practices in eye tracking research. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 155, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinno, A. (2015). Nonparametric Pairwise Multiple Comparisons in Independent Groups using Dunn’s Test. Stata Journal, 15, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccius-Wellmann, C. (2008). Schülerwissen und Lehrerwissen zur Schulalgebra—Fachdidaktische Fehleranalysen—Eine Untersuchung an der Universidad Panamericana in Guadalajara (Mexiko) [Ph.D. Thesis, Universität Hamburg]. Available online: https://ediss.sub.uni-hamburg.de/bitstream/ediss/2139/1/dissertation.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Figueras, H., Males, L., & Otten, S. (2008). Algebra students’ simplification of rational expressions. Michigan State University Press. Available online: http://www.msu.edu/ottensam/RationalExpressionSimplification.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Ghosh, S., Wronski, P., Koetsenruijter, J., Müller, W., & Wensing, M. (2021). Article: Watching people decide: Decision prediction using heatmaps of reading a decision-support document. Journal of Vision, 21(9), 2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, S. A., & Vagi, K. J. (2010). Sources of Group and Individual Differences in Emerging Fraction Skills. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(4), 843–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessels, R. S., Kemner, C., van den Boomen, C., & Hooge, I. T. C. (2016). The area-of-interest problem in eyetracking research: A noise-robust solution for face and sparse stimuli. Behavior Research Methods, 48(4), 1694–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, S., Moeller, K., & Nuerk, H. C. (2014). Adaptive processing of fractions—Evidence from eye-tracking. Acta Psychologica, 148, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ischebeck, A., Weilharter, M., & Körner, C. (2016). Eye movements reflect and shape strategies in fraction comparison. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 69(4), 713–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamil, M. A., & Khanam, S. (2024). Influence of one-way ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis based feature ranking on the performance of ML classifiers for bearing fault diagnosis. Journal of Vibration Engineering & Technologies, 12(3), 3101–3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. J., & Boyadzhiev, I. (2020). Underprepared College Students’ Understanding of and Misconceptions with Fractions. International Electronic Journal of Mathematics Education, 15(3), em0583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, K., Dreher, A., Holzäpfel, L., & Wittmann, G. (2020). Are conceptual knowledge and procedural knowledge empirically separable? The case of fractions. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(3), 809–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X., & Cui, Y. (2025). Eye tracking technology for examining cognitive processes in education: A systematic review. Computers and Education, 229, 105263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makonye, J., & Stepwell, N. (2016). Eliciting errors and misconceptions in simplifying rational algebraic expressions to improve teaching and learning. International Journal of Educational Sciences, 12(1), 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malle, G. (1993). Didaktische probleme der elementaren algebra. Vieweg. [Google Scholar]

- Mhakure, D., Jacobs, M., & Julie, C. (2014). Grade 10 students’ facility with rational algebraic fractions in high stakes examination: Observations and interpretations. Journal of the Association for Mathematics Education in South Africa, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Miller Singley, A. T., & Bunge, S. A. (2018). Eye gaze patterns reveal how we reason about fractions. Thinking and Reasoning, 24(4), 445–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller Singley, A. T., Crawford, J. L., & Bunge, S. A. (2020). Eye gaze patterns reflect how young fraction learners approach numerical comparisons. Journal of Numerical Cognition, 6(1), 83–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y., & Zhou, Y. D. (2005). Teaching and learning fraction and rational numbers: The origins and implications of whole number bias. Educational Psychologist, 40(1), 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novianggraeni, T. D., Masriyah, & Lukito, A. (2019). Students’ procedural and conceptual fraction knowledge based on cognitive style. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1417(1), 012043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obersteiner, A., Moll, G., Beitlich, J. T., Cui, C., Schmidt, M., Khmelivska, T., & Reiss, K. (2024, January 10). Expert mathematicians’ strategies for comparing the numerical values of fractions—Evidence from eye movements. Joint Meeting of PME 38 and PME-NA (Vol. 4, pp. 337–344), Vancouver, BC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Obersteiner, A., & Staudinger, I. (2018). How the eyes add fractions: Adult eye movement patterns during fraction addition problems. Journal of Numerical Cognition, 4(2), 317–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obersteiner, A., & Tumpek, C. (2016). Measuring fraction comparison strategies with eye-tracking. ZDM-Mathematics Education, 48(3), 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, C. (2023). Kruskal-Wallis test: What it is, advantages and how it is performed. QuestionPro. Available online: https://www.questionpro.com/blog/es/prueba-de-kruskal-wallis/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Purves, D., Augustine, G. J., Fitzpatrick, D., Katz, L. C., LaMantia, A. S., McNamara, J. O., & Williams, S. M. (2001). Neuroscience (2nd ed.). Sinauer Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Rahal, R. M., & Fiedler, S. (2019). Understanding cognitive and affective mechanisms in social psychology through eye-tracking. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 85, 103842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramat, S., Leigh, R. J., Zee, D. S., Shaikh, A. G., & Optican, L. M. (2008). Applying saccade models to account for oscillations. In C. Kennard, & R. J. Leigh (Eds.), Using eye movements as an experimental probe of brain function. Progress in brain research (Vol. 171, pp. 123–130). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RealEye. (2025, July 8). AOI metrics. Available online: https://support.realeye.io/areas-of-interest-aois (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Skemp, R. R. (1978). Relational Understanding and Instrumental Understanding. The Arithmetic Teacher, 26(3), 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solstad, T., Kaspersen, E., & Eggen, M. (2024). Eye movements in conceptual and non-conceptual thinking. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 118(3), 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susac, A., & Braeutigam, S. (2014). A case for neuroscience in mathematics education. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taban, J. G., & Cadorna, E. A. (2018). Structure sense in algebraic expressions and equations of groups of students. Journal of Educational and Human Resource Development, 6, 140–154. [Google Scholar]

- Yakubu, B., & Jungudo, B. (2023). Misconception as a Factor Affecting Performance of Diploma Students in Solving Fractions. International Journal of Assessment and Evaluation in Education, 2(1). Available online: https://mediterraneanpublications.com/mejaee/article/view/201 (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Ying Tsang, H., Tory, M., & Swindells, C. (2010). eSeeTrack-Visualizing Sequential Fixation Patterns. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 16(6), 953–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| AOI | An AOI is a portion of stimuli that is utilized to analyze eye gaze metrics and associate eye movement indicators with the specific area of the stimuli examined (e.g., the duration spent observing a particular element within the stimulus) (Hessels et al., 2016). |

| Heatmaps | Heatmaps are visual tools that display the distribution of gaze points using a colour gradient over the stimulus, where red, yellow, and green indicate decreasing levels of visual attention. They provide both qualitative and quantitative insights into reading and viewing patterns. (Ghosh et al., 2021). |

| Fixation sequences TTFF | Fixation sequences show the path and order in which participants direct their gaze across AOIs, often starting at the centre due to fixation bias and then moving toward the most engaging elements. This order offers insights into attention patterns and underlying cognitive strategies. (Ying Tsang et al., 2010). |

| Fixation counts FC | Indicates the total number of gaze fixations performed to explore or interpret specific components within Areas of Interest (AOIs). (Rahal & Fiedler, 2019). |

| Revisits counts RC | Refers to the average number of times participants redirected their gaze back to a specific AOI. This metric captures how often attention returns to a particular area, which may occur due to visual appeal, cognitive dissonance, or emotional responses such as confusion or frustration. (RealEye, 2025). |

| Saccades count SC | Rapid, ballistic eye movements that swiftly redirect the point of fixation, typically aligning the line of sight with a desired target through a single, fluid motion. (Purves et al., 2001; Ramat et al., 2008). |

| Rational Algebraic Expression | Correct Answer | Important Facts Simplifying Each Expression |

|---|---|---|

| The first exercise was designed to analyze whether students know the concept of simplification or cancellation of identical factors in the numerator and denominator. | ||

| The same concept should be applied in the second exercise, with the modification that the resulting factor appears in the denominator. Students have to remember the neutral elements “1”, when dividing the common factor (x + 3). A “1” prevails in the numerator. | ||

| or | Students should observe that although the expression (x + 3) appears in both the numerator and the denominator, the presence of an addition operation sign (an addition of 1) indicates that these terms are not factors and therefore cannot be simplified, and addition in the numerator should be performed. On the other hand, the fraction can be split into two separate fractions; one could be simplified, and the other not. | |

| The fourth and final exercise also includes an addition, so it can only be simplified if the term (x + 3) in the numerator is factored and then simplified. Alternatively, the expression can be split into two separate fractions and simplified individually, ultimately yielding the same result of x + 1. In this case, the brackets around (x + 3) may suggest a factorization of this expression in the numerator. |

| Rational Algebraic Expression | Incorrect Answer | Important Facts Simplifying Each Expression |

|---|---|---|

| Expanding by multiplying the factors in the numerator may generate other mistakes and no simplification (EX) (1A) Only the first terms and last terms were multiplied (1B) The first terms were multiplied, and the second terms were added. (1C) Concatenation (CON), can be performed in several ways: 3x − −5x divided by 3x | ||

| (2A) De-fractionalization error (DF), the “1” in the numerator is ignored, and the denominator is written as the numerator. Other errors align with the patterns observed in the first simplification exercise. | ||

| (3A) Partial Cancellation Error (PCE) is the most common error | ||

| Partial Cancellation Errors (PCE) occur in two ways: (4A) The first expression (x + 3) in the numerator is cancelled (4B) The second expression (x + 3) is cancelled. These two error options yield different expressions. |

| C Correct Answer | Metrics with Significant Differences (p Values in Brackets) | IC Incorrect Answer |

|---|---|---|

| Exercise 1 Duration M = 13,399.29 ms, SD = 7328.63 CD M = 6980.28 ms, SD = 4693.66 Normal distributed different distributions p < 0.001 |  |

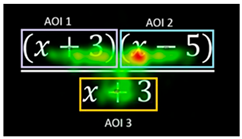

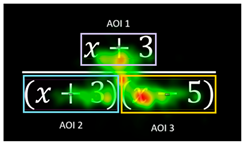

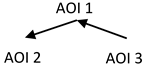

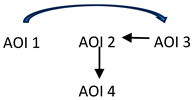

| Percentage of C: 64% The heatmap shows a greater level of visual attention on AOI2. Correct respondents show less attention to AOI1 and AOI3. | For all AOI’s, C-FC < IC-FC; p < 0.001 C-RC AOI2 < IC-RC AOI2; p < 0.001 C-RC AOI3 < IC-RC AOI3; p < 0.001 C-RC AOI1 < IC-RC AOI1; p < 0.001 Both C and IC have significantly less SC on AOI2 than on AOI1, p < 0.001 | Percentage of IC: 36% The heatmap shows a greater level of attention on AOI1, followed by attention on AOI2 |

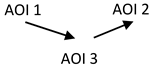

| Order of TTFF time to first fixation: For C; AOI1→AOI3→AOI2 For IC; AOI1→AOI2→AOI3 |  |

| Analysis and interpretation Exercise 1: | ||

| D: The C respondents require less time to give their answer. This indicates that IC may have some difficulty processing information. TTFF sequence: The order in which they focus on the distinct AOIs is different; C respondents direct their attention first to the factor of the numerator (AOI1), then to the denominator factor (AOI3), and finally to the second factor of the numerator (AOI2). They stay longer on AOI2, which may be because AOI2 will prevail after the simplification. IC focuses sequentially from left to right, and then on the denominator. This may be due to the convention of reading from left to right, which might not facilitate the simplification of AOI1 and AOI3, because they will try to multiply the factors in the numerator. FC: The total number of gaze fixations on all AOIs (fixation count) was significantly less for C than for IC. C respondents need fewer fixations to explore or interpret specific components within the AOIs. This may suggest that IC respondents have difficulty recognizing the components. RC: Revisit counts on AOI2 and AOI3 were significantly less for C than for IC; IC may struggle with what to do with the second factor in the numerator. SC: Saccade counts on AOI2 for C and IC respondents are greater than SC on AOI1. For C, it might have a different interpretation than for IC respondents. For the first group (C), this may indicate that the AOI2 factor remains important even after simplification. Respondents in the IC group may believe they need to expand both factor AOI1 and factor AOI2 through multiplication, a process that is often carried out incorrectly. | ||

| C Correct Answer | Metrics with Significant Differences (p Values in Brackets) | IC Incorrect Answer |

|---|---|---|

| Exercise 2 Duration M = 28,297.77 ms, SD = 33,109.69 CD M = 11,727.77 ms, SD = 9988.79 different distributions p < 0.001 |  |

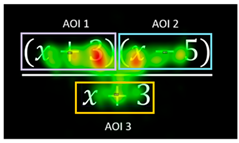

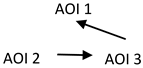

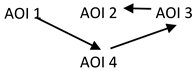

| Percentage of C: 47% The heatmap shows more relative fixation time on AOI3; this factor is important because it is in the denominator. | C-FC-AOI 2 < C-FC-AOI 3 p = 0.031 C-FC-AOI2 < IC-FC-AOI2 p < 0.001 C-RC-AOI 2 < IC-RC-AOI 2 p = 0.029 C-SC-AOI 2 < C-SC-AOI 3 p = 0.004 C-SC-AOI 2 < IC-SC-AOI 2 p < 0.001 | Percentage of IC: 53% More relative fixation on AOI2, little time fixation on AOI3, that is the important factor. |

| Order of TTFF time to first fixation: For C; AOI3→AOI1→AOI2 For IC; AOI2→AOI3→AOI1 |  |

| Analysis and interpretation Exercise 2 | ||

| D: C respondents take less time to simplify the expression. TTFF sequence: C respondents look first at AOI3, the different factor (x − −5) from the others, and then at AOI1 and AOI2. The factor (x − 5) appears to be significant because of its placement in the denominator. IC respondents look from left to right in the denominator and afterwards on the numerator. This might be interpreted for IC that the larger expression in the denominator should be analyzed or operated on first. FC: For C, the intra fixation count on AOI3 is significantly greater than on the other AOIs. This may indicate increased attention and conscious recognition of the importance of AOI3. For IC, there is no significant difference between AOIs. RC: C has a significantly lower revisit count on AOI2 than IC. This probably means that C understands that AOI2 is important for simplification because it is a factor, but IC may have difficulties in understanding this part of the image (factor). SC: Intra-saccade count reveals that for C, AOI3 has a greater count; AOI3 may be important for C. But IC has a higher saccade count on AOI2 than C. This suggests that IC may place greater attentional conflict on AOI2. | ||

| C Correct Answer | Metrics with Significant Differences (p Values in Brackets) | IC Incorrect Answer |

|---|---|---|

| Exercise 3 Duration M = 16,904.00 ms, SD = 13,987.2 CD M = 18,641.88 ms, SD = 9354.43 Normal distributed same distribution p = 0.196 |  |

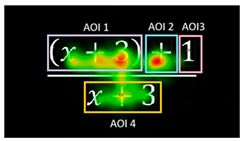

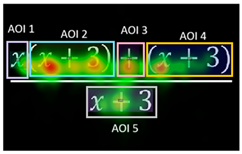

| Percentage of C: 23% The heatmap shows an attention movement between AOI1 and AOI4, and a focus on the plus sign. Visual attention on the expression (x + 3) and the identification of the addition sign may indicate that the students know they cannot proceed with a cancellation shortcut. | C-FC-AOI1 > C-FC-AOI2, C-FC-AOI3, and C-FC-AOI4 p < 0.001 IC-FC-AOI1 > IC-FC-AOI2, IC-FC-AOI3, and IC-FC-AOI4 p < 0.001 IC-RC-AOI1 > IC-RC-AOI2, IC-RC-AOI3, and IC-RC-AOI4 p < 0.001 IC-SC-AOI1 > IC-SC-AOI2 p < 0.001 IC-SC-AOI1 > IC-SC-AOI4 p = 0.017 | Percentage of IC: 77% The heatmap shows relatively higher attention on AOI1 and AOI2. The ‘1’ receives virtually no attention or is only perceived peripherally. The plus sign is probably the sign of their most common result, 1. |

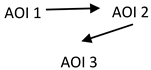

| Order of TTFF time to first fixation: For C; AOI1→AOI3→AOI2 →AOI4 For IC; AOI1→AOI4→AOI2→ AOI3 |  |

| Analysis and interpretation Exercise 3 | ||

| D: No statistically significant difference was found in the time taken by the groups to respond to the task. TTFF sequence: C respondents follow a sequence in which they analyze the components of the numerator, first skipping the addition sign, then returning to it immediately, and afterward moving on to the denominator. This sequence may suggest that C is conscious of the implications of the addition sign and the “1” before they look at the denominator to understand that the expressions (x + 3) in the numerator and denominator cannot be simplified or cancelled. IC respondents identify first the expressions (x + 3) in the numerator and denominator for a possible cancellation method and then analyze the addition sign and the “1”. FC: The fixation counts on AOI1 are the greatest for C and IC. RC: The revisit counts on all AOIs of C respondents have no statistical differences, but the revisit count on AOI1 of IC respondents is the greatest of all the AOIs. SC: There is no statistically significant difference in saccade count across all AOIs of the C group. The saccade count on AOI1 of IC is the greatest. This means that IC may be struggling with what to do with the first (x + 3) in the numerator. However, the TTFF sequence suggests that they want to cancel out this expression with the denominator, without considering the fact that the addition sign causes the numerator to consist of two distinct terms. SC: Intra-saccade count reveals that for C, AOI3 has a greater count; AOI3 may be important for C. But IC has a higher saccade count on AOI2 than C. This suggests that IC may place greater attentional conflict on AOI2. | ||

| C Correct Answer | Metrics with Significant Differences (p Values in Brackets) | IC Incorrect Answer |

|---|---|---|

| Exercise 4 Duration M = 28,588.89 ms, SD = 20,007.48 CD M = 16,531.10 ms, SD = 6061.91 different distributions p < 0.001 |  |

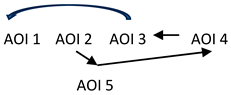

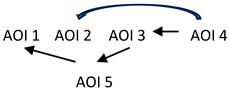

| Percentage of C: 19% The heatmap shows greater visual attention on AOI3 (the addition sign is important in this exercise because simplification first involves factorization or fragmentation into two fractions with the same denominator. Therefore, paying attention to AOI3 may indicate awareness that cancellation cannot be applied without an algebraic transformation. | C-FC-AOI2 < C-FC-AOI1 p = 0.001 IC-FC-AOI2 > IC-FC-AOI1, IC-FC-AOI3, IC-FC-AOI4, IC-FC-AOI5 p < 0.001 IC-RC-AOI2 > IC-RC-AOI1, IC-RC-AOI3, IC-RC-AOI5 p = 0.004 IC-SC-AOI2 > IC-SC-AOI1, IC-SC-AOI3, IC-SC-AOI4, IC-SC-AOI5 p < 0.001 | Percentage of IC: 81% The heatmap shows little attention to AOI3 (the addition sign that causes the numerator to have two terms). There is also relatively little attention to AOI5 compared with other similar expressions (AOI2 and AOI4). Most attention is focused on AOI2. |

| Order of TTFF time to first fixation: For C; AOI2→AOI5→AOI4→AOI3 →AOI1 For IC; AOI2→AOI4→AOI3→AOI5 →AOI1 |  |

| Analysis and interpretation Exercise 4 | ||

| D: C respondents take statistically less time to simplify the expression. TTFF sequence: C respondents show a sequence where they identify all the expressions (x + 3) (AOI2, AOI15, and AOI4 in sequence), then focus on the addition sign (AOI3, with the greatest visual attention), which is important to recognize that the numerator has two terms. The sequence ends with AOI1. IC respondents focus their attention first on the two expressions (x + 3) in the numerator (AOI2 and AOI4, both with the greatest visual attention), then on the addition sign (AOI3), followed by the “x” (AOI1). This may indicate that the plus sign is less important to them. Another possibility is that IC is choosing which of the (x + 3) elements in the numerator can be cancelled out. FC, RC, and SC: IC-AOI2 has the highest intra-statistical values of SC, RC, and FC compared to AOI1, AOI3, AOI4, and AOI5. This indicates that IC focuses most on AOI2, the factor (x + 3) in the numerator. Students may need to pay more attention to process it. For C, there are no statistical differences between AOI’s. | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eccius-Wellmann, C.; Brofman-Epelbaum, J.J.; Corona, V. Eye Tracking Characterization of Algebraic Fraction Simplifications. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1710. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121710

Eccius-Wellmann C, Brofman-Epelbaum JJ, Corona V. Eye Tracking Characterization of Algebraic Fraction Simplifications. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1710. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121710

Chicago/Turabian StyleEccius-Wellmann, Cristina, Jacobo José Brofman-Epelbaum, and Violeta Corona. 2025. "Eye Tracking Characterization of Algebraic Fraction Simplifications" Education Sciences 15, no. 12: 1710. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121710

APA StyleEccius-Wellmann, C., Brofman-Epelbaum, J. J., & Corona, V. (2025). Eye Tracking Characterization of Algebraic Fraction Simplifications. Education Sciences, 15(12), 1710. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121710