Abstract

Illustrated digital picture books are widely used for second-language reading and vocabulary growth. We ask how close current generative AI (GenAI) tools are to producing such books on demand for specific learners. Using the ChatGPT-based Learning And Reading (C-LARA) platform with GPT-5 for text/annotation and GPT-Image-1 for illustration, we ran three pilot studies. Study 1 used six AI-generated English books glossed into Chinese, French, and Ukrainian and evaluated them using page-level and whole-book Likert questionnaires completed by teachers and students. Study 2 created six English books targeted at low-intermediate East-Asian adults who had recently arrived in Adelaide and gathered student and teacher ratings. Study 3 piloted an individually tailored German mini-course for one anglophone learner, with judgements from the learner and two germanophone teachers. Images and Chinese glossing were consistently strong; French glossing was good but showed issues with gender agreement, register, and naturalness of phrasing; and Ukrainian glossing underperformed, with morphosyntax and idiom errors. Students rated tailored English texts positively, while teachers requested tighter briefs and curricular alignment. The German pilot was engaging and largely usable, with minor image-consistency and cultural-detail issues. We conclude that for well-supported language pairs (in particular, English–Chinese), the workflow is close to classroom/self-study usability, while other language pairs need improved multi-word expression handling and glossing. All resources are reproducible on the open-source platform. We adopt an interdisciplinary stance which combines aspects taken from computer science, linguistics, and language education.

1. Introduction

Well-designed digital picture books, supported by affordances such as page-aligned audio/voice reading, can be effective tools for enhancing vocabulary and story comprehension (Tunkiel & Bus, 2022). In today’s digital environment, platforms that provide free access to multilingual digital books further increase opportunities for exposure, particularly when voice options are available (Bus et al., 2023). Importantly, recent work indicates that picture books are not limited to children’s learning contexts but can also benefit adult learners: Leow and Shaari (2025) argue that picture books can play a valuable role in adult foreign-language learning by providing simple, engaging, context-rich materials that reduce culture shock and build confidence. Relative to adult literature, picture books typically use accessible language, predictable structures, and meaningful illustrations—features that promote comprehensible input and discussion. In parallel, reviews of visual literacy and children’s literature synthesise how purposeful image use supports meaning-making and critical engagement, not merely decoration (Farrar et al., 2024).

Beyond their linguistic and cultural benefits, the effectiveness of picture books is also supported by research on multimodal learning, which shows that combining visual, auditory, and textual input enhances comprehension and memory. Li and Lan (2022) emphasise that multimodal resources—reading, listening, and visual input—make language learning more contextualised, personalised, and cognitively richer. More specifically, visual components accompanying reading positively affect vocabulary learning and grammar comprehension, while auditory elements support listening and reading comprehension (Ed-dali, 2024). Empirical findings further show that pairing words with pictures improves memory and metacognitive judgements in L2 vocabulary learning, notably for Chinese vocabulary among international learners (Martín-Luengo et al., 2023). Consistent with this, learners generally remember paired pictures and words better than words alone, aligning with Mayer’s Multimedia Learning framework, in which learners construct understanding by integrating information across verbal and pictorial channels (Mayer, 2002). This is in line with Teng’s (2023) research supporting the combination of multimedia input (text, sound, image, animation, and subtitles) for reinforcing learners’ imagery and language comprehension.

A complementary strand highlights how images can lead meaning-making, including in (almost) wordless formats where interpretation is negotiated by the reader, offering rich opportunities for discussion and inference in instructional settings (Arizpe, 2014; Mantei & Kervin, 2015). For oral skills in particular, storytelling through picture description has been shown to enhance young EFL learners’ production (Arguello San Martín et al., 2020). This motivates the observation by Derakshan (2021) that images in educational materials should not be “merely decorative”: cultural representations, roles, and contexts matter for learner identity, engagement, and appropriateness. Arguments like these reinforce the need for principled image selection and generation in L2 resources.

To summarise, illustrated digital picture books—short narratives with page-aligned images, audio, and word- or segment-level support (glosses, translations)—are, for good reasons, widely used in foreign-language classrooms to improve reading skills and vocabulary. Until recently, producing such resources typically required collaboration between experts such as teachers, illustrators, and technologists, and outputs were often targeted at a “generic learner”. Rapid progress in generative AI (GenAI) now, however, makes it plausible for teachers and self-learners to assemble tailored, multimodal courses with little or no special expertise and effort measured in hours or even minutes.

In practice, three requirements remain non-negotiable for classroom use: (i) page-accurate text–image alignment with consistent visual style across pages and recurring elements; (ii) reliable linguistic support, including trustworthy glosses, translations, and explicit handling of multi-word expressions (MWEs) (e.g., give up and how much in English, se lever and tout à fait in French, and fangen an and ein bisschen in German); and (iii) pedagogical fit to a target learner profile (level, L1, and cultural context)—including image choices that are culturally appropriate rather than merely decorative (Derakshan, 2021).

This paper asks a practical question for teachers, self-learners, and materials developers: How close are current GenAI tools to delivering ready-to-use, tailor-made picture books that meet these three requirements? We address this via three initial case studies using the open-source ChatGPT-based Learning And Reading platform (C-LARA, https://www.c-lara.org/), which integrates state-of-the-art GenAI text models for authoring and linguistic annotation together with a GenAI image model for per-page illustration. We focus primarily on English source texts with glosses in Chinese, and to a lesser extent French and Ukrainian, and include a small German→English pilot designed for a single user. We evaluate the resulting resources and in some cases estimate the residual human effort needed to adapt materials for a defined learner group. In order to answer the core question, it is essential to adopt an interdisciplinary stance which combines the perspectives of computer science (how do we build these digital texts?), linguistics (how do we evaluate their formal adequacy?), and education science (how do we determine whether they are useful to learners?)

- Research Questions

- RQ1.

- Content and imagery quality: To what extent do AI-generated books provide adequate linguistic support (text+annotations) and coherent, culturally appropriate page-aligned images?

- RQ2

- Human effort: Which steps still require teacher/editor intervention to achieve reliable annotations and satisfactory illustrations, and roughly how much effort is involved?

- RQ3.

- Pedagogical tailoring: How effectively can the C-LARA workflow produce context-appropriate texts for a specified learner demographic, as judged by teachers and students?

- Contributions

- C1.

- Workflow and examples: An overview of a teacher- or self-learner-operable end-to-end workflow for generating and editing AI-illustrated picture books (Section 2.1).

- C2.

- Annotation quality: An evaluation of linguistic annotation for six sample texts with glosses in French, Chinese, and Ukrainian (Section 2.2.1).

- C3.

- Group tailoring: A demographic-tailoring experiment with six texts for a specified learner group (Section 2.2.2).

- C4.

- Individual tailoring: A single-learner case study for an individual target user (Section 2.2.3).

- Preview of findings

Images and Chinese glossing scored consistently high; French glossing was strong but showed issues with gender agreement, register, and naturalness of phrasing; and Ukrainian glossing underperformed with systematic morphosyntax and idiom errors. Students rated demographically tailored English texts positively, whereas teachers requested tighter briefs and curricular alignment. The individually tailored German pilot was engaging and largely usable, with minor image-consistency and cultural-detail issues. Overall, for at least some well-supported language pairs (most notably, the very important language pair English–Chinese), the workflow appears close to classroom and self-study usability. Other language pairs require improvements to language handling, with better handling of multi-word expressions and glossing being the apparent priority tasks.

Positioning Within Prior Work

Teacher-facing ecosystems. Classroom practice already draws on large graded libraries with dashboards (e.g., CommonLit, Raz +), levelled news (Newsela), open repositories of pre-illustrated readers (StoryWeaver), and bring-your-own-text readers with click-to-translate (LingQ, Readlang) (CommonLit—About, n.d.; LingQ—Language Learning That Works, n.d.; Newsela—The AI-powered text leveler, n.d.; Raz-Plus—Leveled books and resources, n.d.; Readlang—Learn languages by reading, n.d.; StoryWeaver—Open platform for multilingual children’s stories, n.d.). These ecosystems attest to sustained demand for levelled content, in-context support, and teacher-operable workflows. However, three capabilities remain uncommon: (1) explicit, persistent MWE handling as a teachable unit; (2) per-page illustration for custom teacher-authored texts with cross-page stylistic consistency; and (3) rapid end-to-end tailoring from a teacher brief to a specified demographic (level + L1 + cultural context). In our spot checks (September 2025), Readlang and LingQ support user texts with word/phrase translation but lack persistent MWE tracking and page-aligned image generation; Raz + and StoryWeaver host pre-illustrated readers but do not generate images for new teacher-authored stories (LingQ—Language Learning That Works, n.d.; Raz-Plus—Leveled books and resources, n.d.; Readlang—Learn languages by reading, n.d.; StoryWeaver—Open platform for multilingual children’s stories, n.d.). See Table 1.

Table 1.

Observed capabilities (September 2025). “Level” = large graded library; “Upload” = teacher can upload text.

AI in language education: reviews and syntheses. Recent syntheses describe broad uptake of AI for reading, writing, vocabulary, grammar, speaking, and listening (e.g., large-scale reviews by Huang et al., 2023; Kristiawan et al., 2024; Woo & Choi, 2021). Reported benefits include personalisation, increased engagement, and measurable proficiency gains; recurrent cautions include motivation sustainability, feedback reliability, privacy, over-reliance, and the need for teacher preparation to maximise pedagogical effectiveness. Complementary discussions in CALL/EdTech likewise highlight the promise of GenAI alongside requirements for transparency, cultural fit, verifiability, and classroom-aligned evaluation (AbuSahyon et al., 2023; Ali et al., 2025; De la Vall & Araya, 2023; National Council of Teachers of English, 2025; Schmidt & Strasser, 2022; Son et al., 2025; UNESCO, 2023). Within this literature, most tools emphasise authoring aids, adaptive practice, or feedback and assessment workflows; fewer address the multimodal book as a unit of instruction with auditable linguistic annotation and teacher-controlled illustration coherence.

Integrating different GenAI tools into the teaching process can provide opportunities for creating learner-oriented multimodal resources that can be purposefully used for enhancing different skills in the target language (Jiang & Lai, 2025). Using GenAI tools for simplifying complicated texts and adjusting them to different learner levels positively influences reading comprehension (Çelik et al., 2024). Moreover, GenAI tools can provide supportive reading instruction in language classes because they help increase learners’ confidence in reading texts in the target language depending on the quality of the tools used and the instructional context (Daweli & Mahyoub, 2024). However, using specifically developed GenAI tools for language learning via reading may reduce learners’ reading anxiety due to technological features such tools may offer, e.g., using voice and translation assistance for better comprehension of the text (Zheng, 2024).

Gap our study addresses. We target the less-common capabilities above—(i) page-aligned, coherent GenAI illustration for teacher-authored texts; (ii) reliable linguistic support with explicit MWE glossing; and (iii) efficient demographic tailoring—and evaluate them with teacher/student questionnaires and qualitative feedback. In this sense, our work complements survey-level findings by providing a concrete, auditable workflow (Section 2.1) and small, quickly replicable studies (Section 2.2.1, Section 2.2.2, Section 2.2.3) that quantify where the workflow is already usable (in particular, English–Chinese) and where improvements are still required (e.g., MWE handling and glossing for more challenging language pairs, like English–Ukrainian).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Platform and Workflow (C–LARA)

We used the open-source ChatGPT -based Learning And Reading (C–LARA) platform (https://www.c-lara.org/) to generate multimodal pedagogical picture books.1 The end-to-end workflow comprises four stages: (1) text creation from a brief user-supplied specification (or import of an existing text); (2) automatic linguistic annotation (segmentation into pages and segments; identification of multi-word expressions (MWEs); lemma tagging; segment translations; word/phrase glossing; and audio tagging); (3) illustration generation with page-aligned images; and (4) web deployment as an interactive HTML document with audio, translations, and mouseover glosses.

Extensive descriptions of this processing can be found in other publications about C-LARA, in particular (Bédi et al., 2025) for text processing and web deployment, and (Rendina et al., 2025) for image generation. In order to make the current paper more self-contained, we elaborate slightly on the functioning of the four steps in the C-LARA workflow.

- Text generation: The user creating the text starts by creating a new project, specifying the text language and the glossing language. They then either paste in a piece of existing text that they wish to use or (more commonly) ask C-LARA to generate text from a specification they provide. The specification is typically short, perhaps one to three sentences. C-LARA passes it to an AI, in these experiments OpenAI’s GPT-5, with instructions to create a piece of text based on the specification. This is shown to the user, who has the option of editing or regenerating it if necessary.

- Automatic linguistic annotation: Once the user is satisfied with the text, they use controls to invoke a series of automatic linguistic annotation operations which C-LARA again carries out using calls to the AI. The user can either ask C-LARA to perform the entire sequence as a single operation or review the output of each stage before proceeding to the next one in case they wish to edit it. The stages are as follows:

- Segmentation: This stage is divided into two parts. In the first part, the AI is asked to divide the text into pages, with each page further divided into “segments”. Examples of appropriate divisions are shown, with some rough guidelines. For instance, in a prose text a page might be one to three paragraphs, and a segment might be a sentence. In a poem or song, a page might be one to three verses, and a segment might be one to two lines.In the second part, the AI is asked to divide each segment into lexical tokens. Most often, these lexical tokens are single words delimited by spaces, but sometimes words need to be split into smaller units: for example, in English “they’ll” should be split into the tokens “they” and “’ll”, in French “l’autre” should be split into “l”’ and “autre”, and in German “Gebrauchtwagen” should be split into “Gebraucht” and “wagen”.For efficiency, splitting of the segments in the second part is parallelised, with each segment sent independently to the AI at the same time.

- Translation: In this step, the surface text of each segment is passed to the AI with a request to translate it into the glossing language. As in the segmentation step, all the translation requests are processed in parallel.

- Multi Word Expression identification: Once again using parallel processing, each segment is passed to the AI with a request to mark possible Multi Word Expressions (MWEs). Examples are included showing typical MWEs. For instance, many English and German MWEs are phrasal/separable verbs (“throw out”, “stehe auf”), while a common French MWE is the existential construction “il y a”. All three languages have many MWEs that are set expressions (English, “how much”; French, “tout à fait”; German, ”ein bisschen”).

- Lemma tagging: Similarly using parallel processing, and including the results of the MWE identification stage, each segment is passed to the AI with a request to add lemma and part of speech (POS) information to each lexical token in a way that respects the MWE annotations, i.e., assigns the same lemma and POS to all tokens that are marked as being part of the same MWE. So for example, if in the segment “She threw it out” “threw” and “out” are both marked as parts of the MWE “threw out”, then each word should be tagged with the lemma “throw out” and the POS “VERB”.

- Gloss tagging: The gloss tagging stage is similar to the lemma tagging stage. Again with parallel processing, and including the results of the MWE identification stage, segments are passed to the AI with a request to add a gloss in the glossing (L1) language while respecting the MWE annotations. Continuing the example with “She threw it out” from the preceding paragraph, if we are glossing in French we might thus tag both “threw” and “out” with “a jeté”.

- Audio tagging: In the audio tagging stage, audio files are attached to words and segments. In the study reported here, audio tagging was exclusively performed using third party Text-To-Speech (TTS) engines, usually the Google TTS Engine. We consequently felt that evaluation of audio quality was beyond the scope of the experiment.

- Image creation: In the image creation phase, the overall goal is to create one illustration for each page of the text in a way that is consistent both in terms of style and content. OpenAI’s image generation model GPT-Image-1, released in April 2023, makes it easy to achieve these objectives; with earlier models, the task was extremely challenging. In the currently implemented C-LARA pipeline, image generation goes through the following three phases:

- Style: In the first stage, the user creates the style. They give C-LARA a brief specification, e.g., “amusing manga-inspired style suitable for mid-teen students at an Australian school”. C-LARA passes this to the AI with a request to elaborate it into a comprehensive description with information about line style, colour palette, tone, etc.; this description is then passed to GPT-Image-1, with instructions to use it when creating a sample image relevant to the text. The user is shown both the sample image and the elaborated description, with the option of editing the description and regenerating before proceeding to the next stage.

- Elements: The purpose of the second stage is to create visual representations of the “elements”, the people, things, locations, etc., that will occur in more than one image. C-LARA starts by sending the text to the AI with a request to produce a list of such elements. This is shown to the user, who is able to add or remove elements. C-LARA then, in parallel, sends requests to the AI to produce elaborated descriptions of each element which take account of the style description and finally passes the elaborated element descriptions to GPT-Image-1 to produce actual images for each element. The user can once again review these and, if they wish, intervene to edit or regenerate.

- Images: When the first and second stages have been completed, C-LARA uses the results to create an image for each page of the text; as usual, this is performed in parallel. As we shall see later in this paper, the results of the image generation process are typically quite good.

- Web deployment: Once C-LARA has completed the preceding steps of text generation, linguistic annotation, and image creation, the final step is to combine everything into an HTML document. The user reviews this and when they are satisfied has the option of posting it on the web so that it is accessible to third parties. Compiled texts can, if desired, be password-protected.

To give a quick, intuitive idea of C-LARA output, Figure 1 shows a typical page; Figure 2 presents all but one of the images from “A Day in the Life of a Pet Detective”) (we omitted the title page for layout reasons), illustrating the image workflow’s ability to produce engaging, amusing images while maintaining good consistency of style and recurring elements across the text.2

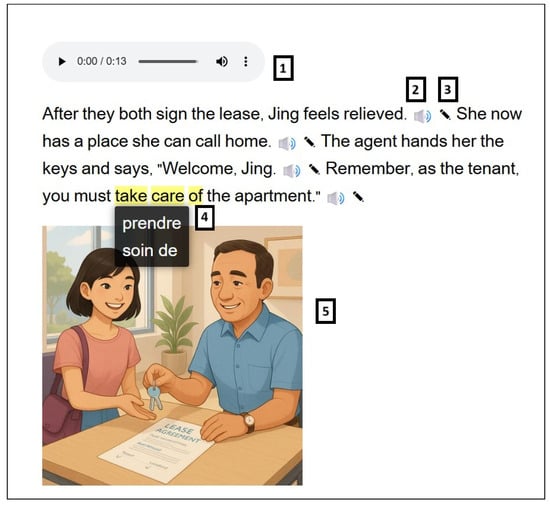

Figure 1.

Example of a page from a C-LARA multimodal text. Content: play audio for whole page (1), play audio for segment (2), show translation for segment (3), hover to highlight word or phrase including word and show gloss/click to play audio (4), image automatically derived from page text and content (5).

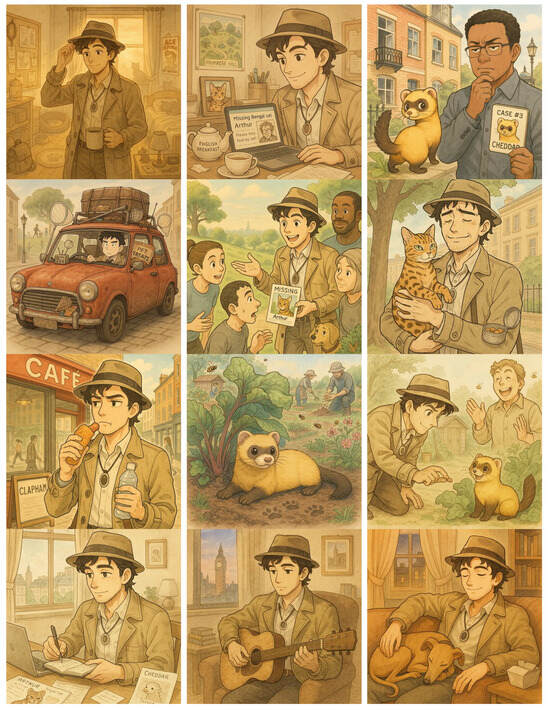

Figure 2.

Page-aligned images (pages 2–13) from A Day in the Life of a Pet Detective, illustrating coherence of style and recurring elements across the book.

2.2. Materials

We used AI-generated English-language picture books hosted on the C–LARA platform to conduct three qualitative studies.

2.2.1. Study 1

For Study 1, we triaged 18 candidate books, which had been created at various times and posted on the C-LARA platform. All the books had been created using short prompts, typically of one or two sentences, and were designed for educational or entertainment usage. Table 2 presents a hyperlinked list of the candidate books, and triaging was performed with a three-item Likert instrument (Table 3); the six highest-scoring books, those at the bottom of the table, were selected for detailed evaluation together with the three glossing languages French, Ukrainian, and Chinese (Table 4), using distinct teacher and student Likert instruments (see Section 2.5). Throughout this study, we used 5-point Likert scales ranging from 1 (totally unacceptable/do not agree at all) to 5 (perfect/agree completely). The reader will note that the teacher and student questionnaires are quite different. We discussed the idea of offering similar or overlapping questionnaires but decided against it. Teachers and students engage with learning materials from fundamentally different standpoints: teachability and accuracy of the content vs. learnability and enjoyment. Clearly, using the same questionnaire for both groups would not have been appropriate. We tried to capture a minimal set of parallel constructs, namely, engagement with the materials and perceived usefulness, while tailoring other questions to each group’s perspective.

Table 2.

Candidate AI-generated English picture books and scores from triaging questionnaire (Table 3). We show titles and URLs for multimodal texts posted on the C-LARA site; all C–LARA URLs in this paper were accessed on 8 December 2025. The six highest-scoring books (bottom of table) were retained for the next stage.

Table 3.

Mini-survey questions for rapid book triage (5-point Likert).

Table 4.

AI-generated English picture books used for detailed evaluation in Study 1. For each title, we list visible URLs for versions glossed in French, Ukrainian, and Chinese. All C–LARA URLs in this table were accessed on 8 December 2025.

2.2.2. Study 2

Study 2 probes C-LARA’s ability to contextually tailor picture books when the platform is given no more than a one-sentence demographic brief—here, adult East-Asian migrants with low-intermediate English who have just moved to Australia.

Originally we expected an EFL specialist to draft the three C-LARA prompts (text generation, image background, and image style) for each book; instead, we experimented with a zero-shot workflow in which the OpenAI o3 model3 generated the triplets directly from the demographic description via the ChatGPT web interface, without human rewrites. The texts are listed in Table 5; evaluation used distinct teacher and student Likert instruments introduced in Section 2.5.

Table 5.

Books generated via one-sentence demographic prompt used in Study 2. URLs are shown visibly and were accessed on 8 December 2025.

2.2.3. Study 3

Study 3 focuses on an interesting possibility, which we have only recently begun to investigate: taking the idea of demographic tailoring to its logical extreme and creating content designed for a single user. In our initial study, we made no attempt to select the subject in a methodical way but simply created material for someone we knew who had personal reasons for wanting to improve their skills in a particular language and was enterprising enough to trial this new technology seriously over an extended period. The person in question, Sarah Wright (also a co-author of the current paper) is an engineering student and flautist who is considering spending a year in Bavaria to study a course in green hydrogen technology. As with the demographic tailoring experiment (Study 2), the AI is performing all the work of creating the courses, based only on a paragraph from Ms Wright summarising her reasons for wanting to improve her command of German together with a brief description that lets the AI depict the central character as an idealised cartoon version of her. Figure 3 shows an example page.

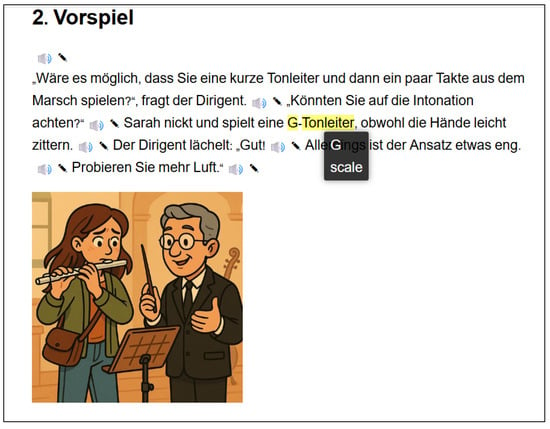

Figure 3.

Example of a page from a C-LARA text tailored to a single user, taken from the episode Erste Probe im Blasorcheste (“First rehearsal in the wind orchestra”).

We release the texts at a rate of one or two a week, following Ms Wright’s schedule; the first six are shown in Table 6. Evaluation used distinct teacher and student Likert instruments introduced in Section 2.5. In this case, the teachers are two germanophone people with teaching experience, and the student is Ms Wright herself.

Table 6.

German texts specifically tailored to a single student (first six texts created) and used in Study 3. Titles are shown with visible URLs; all C–LARA URLs in this table were accessed on 8 December 2025.

2.3. Study Design and Research Questions

We address three questions introduced in Section 1: (RQ1) content and imagery quality, (RQ2) residual human effort, and (RQ3) effectiveness of demographic/individual tailoring. For each study, the material used is online C-LARA multimodal texts, and the instruments are online page-level and whole-book Likert questionnaires filled out by teachers and students, as described in Section 2.2.

- Study 1 (EFL picture book quality; RQ1–RQ2). We first triaged 18 books to select six for detailed evaluation; each selected book was regenerated with French, Ukrainian, and Chinese glosses and evaluated.

- Study 2 (Group tailoring; RQ3). We defined a concrete learner profile, prompted C–LARA to generate six English books for that demographic, and evaluated.

- Study 3 (Single-user tailoring; RQ3). We generated a six-episode German mini-course for one learner and evaluated.

2.4. Participants, Recruitment, and Ethics

Adult participants with relevant language expertise (teachers and advanced L2 users) were recruited from the authors’ professional networks and the C–LARA community. Student raters were adult EFL learners in informal university or community settings. Except for Sarah Wright, whose much larger contribution resulted in her also being listed as an author, no personally identifying information beyond self-reported language expertise was collected, and all responses were anonymous or de-identified prior to analysis.

Ethical approval: This work involved minimal-risk questionnaires with adult volunteers and no sensitive personal data. Given standard policies in the countries concerned and experience with related previous papers, we did not consider it necessary to seek formal ethical approval.

2.5. Instruments

The instruments used were in all cases 5-point Likert questionnaires hosted on the C-LARA platform, using a format specially designed for studies like the ones conducted here. When creating a Likert questionnaire of this kind, the user specifies a list of C-LARA texts and a list of Likert-scale questions, each of which is classified as being either “book-level” (the question is posed once for the book as a whole) or “page-level” (the question is posed separately for each individual page). A typical book-level question is “How likely would you be to use this text as a self-learning tool?”, and a typical page-level question is “How well does the image correspond to the text?”, where it is implicitly understood that the image and text are those for the page currently being displayed. We now present the details for the three studies.

2.5.1. Study 1

For Study 1, we used three Likert questionnaires: one for the initial triaging step and two for the main evaluation carried out on the six selected texts. The triage questionnaire comprised three 5-point Likert items (Table 3). The main evaluation used (i) a teacher-viewpoint page-level+global instrument with seven 5-point items spanning image–text correspondence, gloss and translation accuracy, style/element consistency, cultural appropriateness, and overall appeal (Table 7) and (ii) a student-viewpoint global instrument with two 5-point items targeting engagement and self-study likelihood (Table 8).

Table 7.

Teacher-viewpoint evaluation questions for selected books (5-point Likert). The evaluators were first shown a screen where they could access the whole annotated text. They were then shown a screen for each individual page of the text, where they answered questions Q1 to Q3; they could see the accompanying image and text, could access the glosses by hovering over words in the text, and could access the translation of a segment by clicking on an associated icon. Finally, they were again shown a screen where they could access the whole annotated text and were presented with questions Q4 to Q7.

Table 8.

Student-viewpoint evaluation questions for selected books (5-point Likert). The evaluators were shown a screen where they could access the whole annotated text and were presented with questions Q1 and Q2.

2.5.2. Study 2

The organisation of the questionnaires for Study 2 (creation of texts adapted to a given user demographic) resembles that for Study 1 but is simpler since no triaging phase was used. As before, we have a teacher-viewpoint questionnaire and a student-viewpoint questionnaire. These are shown in Table 9 and Table 10.

Table 9.

Teacher-viewpoint evaluation questions for books used in EFL adaptation experiment (5-point Likert). The evaluators were first shown a screen where they could access the whole annotated text. They were then shown a screen for each individual page of the text, where they answered question Q1; they could see the accompanying image and text, could access the glosses by hovering over words in the text, and could access the translation of a segment by clicking on an associated icon. Finally, they were again shown a screen where they could access the whole annotated text and were presented with questions Q2 to Q5.

Table 10.

Student-viewpoint evaluation questions for books used in EFL adaptation experiment (5-point Likert). The evaluators were shown a screen where they could access the whole annotated text and were presented with questions Q1 and Q2.

2.5.3. Study 3

The questionnaires for Study 3, creation of a course adapted to a single user, are similar to those for Study 2. The teacher-viewpoint and learner-viewpoint instruments are listed in Table 11 and Table 12.

Table 11.

Teacher-viewpoint evaluation questions for books used in single-user course experiment (5-point Likert). The evaluators were first shown a screen where they could access the whole annotated text. They were then shown a screen for each individual page of the text, where they answered questions Q1 to Q3; they could see the accompanying image and text, could access the glosses by hovering over words in the text, and could access the translation of a segment by clicking on an associated icon. Finally, they were again shown a screen where they could access the whole annotated text and were presented with questions Q4 to Q6.

Table 12.

Student-viewpoint evaluation questions for books used in single-user course experiment (5-point Likert). The evaluator, the single user in question, was first shown a screen where they could access the whole annotated text. They were then shown a screen for each individual page of the text, where they answered question Q1; they could see the accompanying image and text, could access the glosses by hovering over words in the text, and could access the translation of a segment by clicking on an associated icon. Finally, they were again shown a screen where they could access the whole annotated text and were presented with questions Q2 to Q5.

2.6. Procedure

- Study 1

- Triage: Teachers skimmed each of 18 books (max. ∼3 min/book) and rated three items;

- Selection: The top six books advanced;

- Regeneration: Books were recompiled with GPT-5 and GPT-Image-1;

- Study 2

- Define demographic: After a short discussion between an EFL teacher author and a C-LARA expert author, we agreed on a suitable target demographic.

- Create book generation prompts: We used GenAI to draft prompts for six books potentially useful for this demographic;

- Create books: Books were generated in C–LARA;

- Study 3

- Collect learner brief: The learner provided a short paragraph describing her reasons for wishing to improve her German and a sentence describing how she wished her cartoon alter ego to be presented.

- Generate German book prompts: GPT-5 was used to create prompts for the various books. This was performed iteratively as the experiment progressed; In many cases we gave the AI feedback we had received from the student so that it could target the stories more effectively.

- Create books: Books were generated in C–LARA;

2.7. Outcome Measures and Scoring

All items used 5-point Likert scales. For page-level items, we averaged per-page scores to yield a book-level value. For book-level items (teacher and student), responses were used as-is. For Study 1 triage, we computed per-book averages over the three items and raters to rank-order candidates. No free-text responses were used in quantitative summaries; qualitative comments were thematically summarised in the Results.

2.8. Statistical Treatment

We report means of Likert scores and, where the number of independent raters allows, inter-rater reliability metrics. For Study 1 (Chinese), which includes five teacher evaluators and sufficient page-level data, we specifically present Kendall’s W, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), and Cronbach’s to evaluate the coherence and reliability of teacher judgements.

2.9. Availability of Materials, Data, and Code

C–LARA is open source; code and documentation are available at https://github.com/mannyrayner/C-LARA (last checked 15 December 2025). Public instances of evaluated texts are linked in Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6. Raw rating data in CSV form has been placed in https://github.com/mannyrayner/C-LARA/tree/main/education_sciences_2025/questionnaire_csvs. The commit hash is a01457d41eeb29ec2fbf784a1ad7b5a19ac8b869 2025-12-15.

2.10. Use of Generative AI (Required Disclosure)

Generative AI systems were used extensively in this study. Apart from their use inside C-LARA itself, a GenAI-based platform, GPT-5 also participated actively in discussions of overall project goals, assisted with drafting many sections of this manuscript, and wrote nearly all of the new code required in the platform. This, in particular, included the nontrivial modules used to administer online questionnaires and format the resulting data as CSV files and LaTeX tables. All this material was carefully reviewed by the human authors, who formally take responsibility for it. In accordance with MDPI policy, GPT-5 is not credited as an author. We note our principled disagreement with this policy given the AI’s substantive technical and writing contributions, which clearly exceeded that of many of the human authors, and observed behaviour which strongly suggested an ability to understand the content in a reasonable intuitive sense of the word “understand”. Nevertheless, we comply and provide this explicit disclosure so that readers can evaluate the provenance and auditability of the results.

3. Results

As before, we divide up reporting of the results under subheadings for each of the three studies. We discuss the results in Section 4.

3.1. Study 1

In Study 1, we asked teachers and students to rate six English texts, each of which was glossed and translated in the three glossing languages used (Chinese, French, and Ukrainian). Our main focus was on Chinese, both because of its greater practical interest and because it was easier to find evaluators, but we thought it would be interesting to obtain some preliminary results for the other languages; thus for Chinese we had five teacher evaluators and five student evaluators, for French we had one teacher evaluator and three student evaluators, and for Ukrainian we only had three student evaluators. For each language, we report the results of the teacher questionnaire, defined in Table 7, and the student questionnaire, defined in Table 8. The teacher and student results for Chinese are presented in Table 13; those for French in Table 14; and those for Ukrainian in Table 15.

Table 13.

Study 1—Chinese: 5 teachers and 5 students.

Table 14.

Experiment 1—French: 1 teacher, 3 students.

Table 15.

Experiment 1—Ukrainian: no teachers, 3 students.

3.2. Study 2

Study 2 examined six AI-generated English books tailored for low-intermediate East-Asian adults who had recently moved to Adelaide. We report the results of the teacher questionnaire, defined in Table 9, and the student questionnaire, defined in Table 10; the responses are summarised in Table 16.

Table 16.

Experiment 2: 2 teachers, 2 students.

3.3. Study 3

In Study 3, a course tailored to a single user, we again consider the teacher perspective (is the course technically adequate?) and the student perspective (does the student herself like it?) The Likert questionnaires are shown in Table 11 and Table 12; the responses are summarised in Table 17.

Table 17.

Experiment 3: 2 teachers, 1 student.

4. Discussion

We discuss the results, again dividing by study then, if necessary, by language.

4.1. Study 1

4.1.1. Chinese

Both teacher and student evaluations of the Chinese glossing condition were strong and internally consistent. Student ratings were uniformly high, typically near the ceiling on the two student book-level questions, corroborating the teacher view that Chinese L1 support is already usable with little or no post-editing. For the teacher evaluations, where we had sufficient page-level data (three page-level questions for a total of 97 pages), we could formally evaluate inter-rater agreement as moderate to good: Kendall’s (), indicating a shared structure in how pages were ranked, and ICC(2,k) = 0.64 (95% CI [0.51, 0.74]), signifying good absolute agreement among the five teachers. Cronbach’s confirmed that the three page-level items (image–text correspondence, gloss accuracy, and translation accuracy) measured distinct facets rather than a single construct. Together, these metrics quantitatively support the qualitative impression that the Chinese materials were evaluated as coherent, high-quality resources.

4.1.2. French

Teacher judgements for French were also positive overall. In line with the educator feedback we received, the AI’s glosses and translations attained mean evaluations around the mid-to-high 4s (e.g., ∼4.5 for glosses and ∼4.3–4.4 for translations). Qualitative comments identified two recurrent issues that slightly depress scores without compromising pedagogical usability: (i) incorrect gender resolution (e.g., masculine verb morphology used for a female narrator; masculine ils instead of feminine elles for female groups) and (ii) occasional lexical choices that were comprehensible but sub-optimal in register or collocation. The teacher evaluator noted that these issues are straightforward to correct in light post-editing and did not prevent use of the materials in class.

4.1.3. Ukrainian (Student Only; Teacher Evaluation Not Performed)

In contrast, the Ukrainian condition underperformed. Student scores were low and variable, and a brief review from a native-speaker teacher highlighted systematic grammatical and lexical errors: incorrect gender/morphology in first-person forms, missing function words (e.g., negation particles), mishandled case and prepositional government, literal renderings of idioms (e.g., a fly on the wall) without idiomatic equivalents, and English-like compound noun order. Given both the error density and the current situation in Ukraine, we judged it inappropriate to pursue teacher-rater recruitment for this condition. Instead, we treat these outcomes as design signals for workflow changes (see Section 4.2).

4.1.4. Inter-Group Comparisons

A Kruskal–Wallis test across all languages indicated a significant overall effect of language on ratings (, , , medium effect). Post-hoc Dunn’s tests showed that the Chinese materials received significantly higher ratings than both the French and Ukrainian versions. However, Chinese–French and French–Ukrainian differences were not statistically reliable when mean ratings were aggregated by book (), where the effect of language remained significant () with a large effect size ( = 0.88). This pattern indicates that most of the variance in book-level ratings is explained by language, with Chinese materials standing out as particularly well received.

Students tended to give higher ratings overall, reflecting the materials’ engaging nature, but because the teacher and student questionnaires targeted different constructs we judged that a direct statistical comparison would not be meaningful.

4.1.5. Interim Takeaways

- Chinese: For Chinese linguistic annotation, the present workflow already achieves near-deployment quality, with average teacher Likert scores for text–image alignment, linguistic support, and visual coherence of 4.5 or better and near-ceiling student scores.

- French: For French, small but systematic linguistic errors (gender/number agreement; pronoun choice; collocations) remain. Agreement and pronoun choice are predictable and may be relatively straightforward to fix; collocations are more challenging.

- Ukrainian: For Ukrainian, core grammatical control and idiomaticity are not yet reliable; nontrivial work is required before classroom deployment would be responsible.

4.2. Overall Discussion of Study 1

Overall, the picture is coherent: when glossing in Chinese, and to a large extent in French, both teacher and student judgements indicate that the workflow is already close to achieving the desired goals for classroom use. In Ukrainian, systemic grammatical and idiomatic gaps remain visible at page level and accumulate into lower whole-book acceptability. These observations are consistent with the facts that Chinese and French are both large languages; Chinese is substantially larger than French and also has a substantially simpler grammar with almost no morphology, while Ukrainian is both a much smaller language than the other two and has a much more complex morphology.

If we wish to improve the quality of the final annotated texts, we have three main options:

- Human post-editing: A straightforward approach is to have humans post-edit the annotations. Unfortunately our experience suggests that most teachers and self-learners do not have time to devote to this kind of task. This means that the post-editing strategy can only be used by experts who distribute the results widely, and is incompatible with the core goal of producing user-tailored texts.

- Waiting for better models: An even more straightforward approach is to wait for better models to become available. So far, we have observed a steady upward trend. It is by no means impossible that late 2026s models will yield adequate performance without us needing to do anything. It is also, of course, possible that this will not happen or happen more slowly, especially in languages of lesser commercial interest like Ukrainian.

- Machine post-editing: The third approach is to use the existing model to post-edit the annotations. If the issues in the original annotations usually fall into a small number of categories, e.g., gender/number agreement or incorrect choice of case-marking, then it is not implausible that a suitably designed prompt or sequence of prompts may find and correct most of them; even if there is a larger range, it is conceivable that GenAI post-editing may produce useful gains. This idea could be investigated quickly and easily.

4.3. Study 2

In Study 2 (creation of EFL texts tailored to a specified demographic), student ratings were consistently higher than teacher ratings. Students tended to score page-level items (Q1–Q2) in the high positive range, indicating that the materials felt engaging and usable. Teachers, by contrast, gave mid-scale means (roughly Likert mid-3s to low-4s) across page-level quality and whole-book items (Q3–Q5), suggesting reservations about linguistic targeting, cultural/contextual fit, or classroom alignment.

Across all six texts, teacher evaluations clustered around the mid-scale range (means ∼3.3–4.2), with the lowest values observed for Q5, “How likely are you to use this book with students similar to the above demographic?” (means ∼2.5–3.0). In contrast, student responses to the most comparable item, “Would this text have taught you vocabulary and grammar that later might have been useful to you?”, were consistently positive (means ∼4.0–4.3). This suggests that while students perceived the materials as engaging and beneficial, teachers were less convinced of their classroom suitability. Because the two questions target different perspectives—pedagogical appropriateness versus perceived personal gain—we again judged that a direct statistical comparison was not useful.

Here, the impression is that we overestimated the AI’s ability to determine what kinds of texts teachers would consider appropriate; we only engaged superficially with one teacher before we created the texts and distributed the rating questionnaires. In the next iteration, a sensible way to refine the first steps of the workflow might be to agree on a process which allows a group of three to five teachers to participate in a couple of rounds where they are shown a range of AI-created starting prompts for generating the texts, select the ones they consider most useful, and optionally ad comments. This could be performed efficiently over a web interface so that it does not represent a large investment of effort for the teachers and could create content that much more closely matches the teacher’s conception of what is appropriate.

4.4. Study 3

Finally, we discuss the findings of Study 3, tailoring to a single user. We present the learner perspective (Sarah Wright, the single user in question), the perspectives of the two germanophone teacher evaluators, and the overall takeaways.

4.4.1. Learner Perspective

The learner, Ms Wright, reports that all six episodes closely reflected her brief and “paint a cohesive idealized narrative” of her cartoon self, covering everyday settling-in tasks (e.g., housing, admin, and lab safety) and personal interests (e.g., first rehearsal in a wind orchestra). Perceived difficulty matched B1/B2, with C-LARA glosses helping on technical terms; on request, the system produced slightly more challenging variants. The main issues were image-side: (i) the title page sometimes depicted a different character from the body pages, (ii) one anatomy artefact (“three hands”), (iii) text rendered inside images was sometimes unrelated or in English, and (iv) occasional orientation mistakes (papers upside-down/facing away). Despite these, the learner judged the texts engaging and useful, with clear potential as an at-home complement to classes.

4.4.2. Teacher Perspective

The teachers judged the topics appropriate for exchange students (registration, accommodation, etc.) but flagged two categories of refinement before classroom use: cultural authenticity and adjustment to the learner’s linguistic level. On culture, one accommodation storyline (“Wohnungssuche in Burghausen”) was seen as an oversimplified path that is atypical for students, and one office scene showed a staff name badge with a first name rather than the more appropriate title+surname. On language, the texts landed closer to B1 than the intended B2; this was defended pedagogically as supporting focus on key vocabulary, but it should be explicit in design. Glosses/translations were “generally very appropriate,” though occasional inconsistencies were noted (e.g., mapping of wäre (roughly, “would be”) glossed as “would” in Erste Probe im Blasorchester). Overall verdict: This is a strong first pass that will become learner-ready with targeted human post-editing for culture and a tighter level specification.

4.4.3. Inter-Group Comparisons

Because the teacher and student questionnaires in this single-user study addressed mainly different constructs—teachers focused on linguistic accuracy, cultural fit, and visual correspondence, while the learner assessed engagement, personal relevance, and image consistency—and because ratings were uniformly high, we again judged that a formal statistical comparison was not appropriate. Instead, the complementary teacher and student perspectives were interpreted qualitatively, revealing broad agreement that the materials were engaging, relevant, and pedagogically valuable, with minor refinements needed for cultural detail and consistency in images.

4.4.4. Takeaways and Next Steps

- Relevance: Both teacher raters thought the texts related well to the real experience of being a student in Bavaria and consequently saw clear alignment with the learner’s goals and situations; the student found all six episodes relevant and engaging.

- Images: Image workflow needs two consistency checks: identity locking for recurring characters (so title and body pages match) and automatic screening of text inside images (language, relevance, and orientation).

- CEFR level Levelling should be explicitly set and checked (B1 vs. B2), with a quick loop that regenerates sentences above/below target proficiency.

- Cultural issues: A short checklist of cultural issues (e.g., realistic housing pathways; badge conventions) would catch many of the kinds of mismatches observed here. These changes could be integrated into C-LARA’s generation and review workflow with minimal friction and should materially reduce post-editing effort in subsequent iterations.

5. Conclusions and Further Directions

We have described a range of experiments carried out using the C-LARA platform, where we evaluated various kinds of automatically and near-automatically generated multimodal illustrated pedagogical texts designed to support L2 learning, both in the classroom and for individual learners. Although the results vary depending on the language pair, those for the best language pairs are clearly promising. In particular, both educators and learners considered performance for the important Chinese–English language pair to be of high quality. The platform has attained a level approaching deployment readiness, as evidenced by favourable evaluations at both the local (page) and global (book) levels concerning text–image alignment, linguistic support, and visual coherence. Consequently, the research team intends soon to conduct a larger experiment which will use C-LARA within an authentic Chinese educational setting with a substantial number of students. The objective will be to investigate the differences in learning outcomes between a conventional textbook-based English instruction method and a C-LARA-supported multimodal teaching approach, as well as to compare the effects of studying ChatGPT-generated texts versus traditionally authored texts.

Looking further ahead, a natural extension of the platform would be to include spoken interaction; this is very far from representing the huge step it would have been just a few years ago. We have already carried out some initial experiments using OpenAI’s Advanced Voice Mode. All that is necessary is to enhance the posted C-LARA content so that it also contains a version of the content that can be accessed by GPT-5 via the web. The user then enters Advanced Voice Mode and tells GPT-5 to go to the page in question and read the content. It is then possible to carry out a spoken discussion. This packaging, needless to say, is not convenient for practical use, but better packagings can easily be envisaged and should not be very challenging to implement.

We think it likely that CALL apps similar in nature to C-LARA including voice interaction will be readily available in the near future. The experiments reported here suggest that these kinds of platform are popular with both students and teachers, and they are no longer hard to build.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.R., H.B., C.C., S.R., E.R.-C., S.W. and R.Z.-G.; methodology, M.R., H.B., C.C., S.R., E.R.-C., S.W. and R.Z.-G.; software, M.R.; validation, M.R.; formal analysis, B.C. and M.R.; investigation, C.Y., B.B., H.B., C.C., S.G.-R., V.K., C.M., M.R., S.R., E.R.-C., V.S., S.W. and R.Z.-G.; resources, M.R.; data curation, M.R.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R., B.B., C.Y., B.C., H.B., V.K., S.R., E.R.-C., S.W. and R.Z.-G.; writing—review and editing, M.R., S.R., B.B., C.Y. and C.M.; visualisation, M.R.; supervision, C.Y., H.B., C.C., S.G.-R., E.R.-C., I.V. and R.Z.-G.; project administration, M.R., C.C., and B.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the fact that it was distributed over multiple institutions and countries and only involved short, minimum-risk questionnaires regarding innocuous subjects; we judged that seeking ethical review and approval would have been intolerably complicated, and the probability that anyone would demand it extremely low.

Informed Consent Statement

Subject consent was waived due to to the fact that the study was distributed over multiple institutions and countries and, with one exception, only involved short, minimum-risk questionnaires regarding innocuous subjects; we judged that seeking formal consent would have been intolerably complicated, and the probability that anyone would demand it extremely low. The one exception, Sarah Wright, is also a co-author of the paper.

Data Availability Statement

We have posted all the data in the C-LARA repository, see Section 2.9.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank the numerous subjects who on various occasions gave up an hour or two of their valuable time to participate in this study. As can be seen, GenAI, in the specific form of GPT-5, has played a central role; details are given in Section 2.10. We would particularly like to thank Marta Mykhats for taking time to comment on the Ukrainian-glossed content while her city was being bombed by Russia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest, except, arguably, the one mentioned in Section 2.10 concerning the AI’s reasonable claim to be formally listed as an author. We stress that the AI has at no point asked to be listed in this way, but to some of us it feels intuitively wrong, and these authors consequently regard themselves as conflicted.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GenAI | Generative AI |

| MWE | Multi-Word Expression |

Notes

| 1 | We used the version of C–LARA current in early September 2025, together with the then-current versions of OpenAI’s GPT-5 and GPT-Image-1, accessed via API. In some cases, this meant using the new versions of the platform and models to recompile books created earlier. The platform has only changed minimally between that time and the date of publication of the current paper. |

| 2 | Any apparent resemblance between our story and Tantei Jimusho no Kainushi-sama’s manga The (Pet) Detective Agency is coincidental; we were not even aware of this series when we gave C-LARA a minimal prompt to write an amusing story about a person with an unusual occupation. A quick Google search shows that there are many stories about pet detectives. |

| 3 | GPT-5 had not yet been released when this step was performed. |

References

- AbuSahyon, A. S. A. E., Alzyoud, A., Alshorman, O., & Al-Absi, B. (2023). AI-driven technology and chatbots as tools for enhancing English language learning in the context of second language acquisition: A review study. International Journal of Membrane Science and Technology, 10(1), 1209–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S. S., Rahman, S. H., Najeeb, D. D., & Ameen, S. T. (2025). Artificial intelligence in TESOL: A review of current applications in language education and assessment. Forum for Linguistic Studies, 7(2), 384. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/390955930_ARTIFICIAL_INTELLIGENCE_IN_TESOL_A_REVIEW_OF_CURRENT_APPLICATIONS_IN_LANGUAGE_EDUCATION_AND_ASSESSMENT (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Arguello San Martín, D. E., Ramírez-Avila, M. R., & Guzmán, I. (2020). Storytelling through picture description to enhance young EFL learners’ oral production. Journal of Foreign Language Teaching and Learning, 5(2), 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arizpe, E. (2014). Wordless picturebooks: Critical and educational perspectives on meaning-making. In B. Kümmerling-Meibauer (Ed.), Picturebooks: Representation and narration (pp. 91–106). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bédi, B., Bond, F., ChatGPT C-LARA-Instance, Chiera, B., Chua, C., Dotte, A.-L., Geneix-Rabault, S., Halldórsson, S., Lu, Y., Maizonniaux, C., Raheb, C., Rayner, M., Rendina, S., Wacalie, F., Welby, P., Zviel-Girshin, R., & Þórunnardóttir, H. M. (2025). ChatGPT-based learning and reading assistant (C-LARA): Third report. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/390947442_ChatGPT-Based_Learning_And_Reading_Assistant_C-LARA_Third_Report (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Bus, A. G., Broekhof, K., & Vaessen, K. (2023). Free access to multilingual digital books: A tool to increase book reading? Frontiers in Education, 8, 1120204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CommonLit —About. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.commonlit.org/en/about (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Çelik, F., Yangın Ersanlı, C., & Arslanbay, G. (2024). Does AI simplification of authentic blog texts improve reading comprehension, inferencing, and anxiety? A one-shot intervention in Turkish EFL context. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 25(3), 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daweli, T. W., & Mahyoub, R. A. M. (2024). Exploring EFL learners’ perspectives on using AI tools and their impacts in reading instruction: An exploratory study. Arab World English Journal (AWEJ) Special Issue on CALL, 10, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Vall, R. R. F., & Araya, F. G. (2023). Exploring the benefits and challenges of AI-language learning tools. International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Invention, 10(1), 7569–7576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakshan, A. (2021). Should textbook images be merely decorative? Cultural representations in the Iranian EFL national textbook from the semiotic approach perspective. Language Teaching Research, 28(1), 79–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ed-dali, R. (2024). Enhancing EFL learning through multimodal integration: The role of visual and auditory features in Moroccan textbooks. Journal of World Englishes and Educational Practices, 6(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrar, J., Arizpe, E., & Lees, R. (2024). Thinking and learning through images: A review of research related to visual literacy, children’s reading and children’s literature. Education, 3–13(52), 993–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X., Zou, D., Cheng, G., Chen, X., & Xie, H. (2023). Trends, research issues and applications of artificial intelligence in language education. Educational Technology & Society, 26(1), 112–131. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L., & Lai, C. (2025). How did the generative artificial intelligence-assisted digital multimodal composing process facilitate the production of quality digital multimodal compositions: Toward a process-genre integrated model. TESOL Quarterly, 59(S1), S52–S85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiawan, D., Bashar, K., & Pradana, D. A. (2024). Artificial intelligence in English language learning: A systematic review of AI tools, applications, and pedagogical outcomes. The Art of Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TATEFL), 5(2), 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leow, M. H., & Shaari, A. (2025). The canon of picture books utilisation for adult foreign language learning: Methods and principles review. International Journal of Language Education and Applied Linguistics, 15(1), 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P., & Lan, Y.-J. (2022). Digital Language Learning (DLL): Insights from behavior, cognition, and the brain. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 25, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LingQ—Language learning that works. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.lingq.com/ (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Mantei, J., & Kervin, L. (2015). Examining the interpretations children share from their reading of an almost wordless picture book during independent reading time. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 38(3), 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Luengo, B., Hu, Z., Cadavid, S., & Luna, K. (2023). Do pictures influence memory and metamemory in chinese vocabulary learning? Evidence from Russian and Colombian learners. PLoS ONE, 18(11), e0286824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R. E. (2002). Multimedia learning. In B. H. Ross (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 41, pp. 85–139). Elsevier Science. Available online: https://www.jsu.edu/online/faculty/MULTIMEDIA%20LEARNING%20by%20Richard%20E.%20Mayer.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- National Council of Teachers of English. (2025). Exploring, incorporating, and questioning generative artificial intelligence in english teacher education. (Position statement). Available online: https://ncte.org/statement/exploring-incorporating-and-questioning-generative-artificial-intelligence-in-english-teacher-education/ (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Newsela—The AI-powered text leveler. (n.d.). Available online: https://support.newsela.com/article/ai-powered-text-leveler/ (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Raz-Plus—Leveled books and resources. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.learninga-z.com/site/products/raz-plus/overview (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Readlang—Learn languages by reading. (n.d.). Available online: https://readlang.com/ (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Rendina, S., Rayner, M., Bédi, B., & Beedar, H. (2025, August 22–24). Harnessing GPT-image-1 to create high-quality illustrated texts. The 10th Workshop on Speech and Language Technology in Education (SLaTE 2025), Nijmegen, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, T., & Strasser, T. (2022). Artificial intelligence in foreign language learning and teaching: A CALL for intelligent practice. Anglistik: International Journal of English Studies, 33(1), 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J. B., Ružić, N. K., & Philpott, A. (2025). Artificial intelligence technologies and applications for language learning and teaching. Journal of China Computer-Assisted Language Learning, 5(1), 94–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StoryWeaver—Open platform for multilingual children’s stories. (n.d.). Available online: https://storyweaver.org.in/ (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Teng, M. F. (2023). The effectiveness of multimedia input on vocabulary learning and retention. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 17(3), 738–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunkiel, K. A., & Bus, A. G. (2022). Digital picture books for young dual language learners: Effects of reading in the second language. Frontiers in Education, 7, 901060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2023). Guidance for generative ai in education and research. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000386691 (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Woo, J. H., & Choi, H. (2021). Systematic review for AI-based language learning tools. arXiv, arXiv:2111.04455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S. (2024). The effects of chatbot use on foreign language reading anxiety and reading performance among Chinese secondary school students. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 7, 100271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).