Abstract

This pilot practitioner inquiry examines the use of AI-generated podcasts within a higher education research module. The study investigated two questions: (1) How do students experience, perceive, and make use of AI-generated podcasts as part of their learning? (2) What opportunities, challenges, and pedagogical considerations emerge for the educator when designing and integrating AI-generated podcasts into teaching practice? Google’s NotebookLM was used to create short recordings that summarised lecture topics, addressed student queries, and offered assignment guidance. Data were gathered from both the educator’s reflective journal and a student focus group. Findings suggest that students valued the novelty, accessibility, and supportive tone of the podcasts. They described the recordings as helpful in revisiting key ideas, clarifying uncertainties, and managing study along with other responsibilities. The educator found the podcasts practical to produce and noted that they contributed to more focused classroom discussions. At the same time, both students and the educator identified limitations, including the constraints of an audio-only format, the need for transparency when using AI, and the additional time required. As a pilot study, the findings provide indicative insights rather than generalisable conclusions. The work points to the potential of AI-generated podcasts as a supplementary resource that may reinforce understanding and support independent study, while also highlighting considerations around inclusivity, educator workload, and responsible AI use in higher education.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Emergence of Podcasts

As digital learning expands, podcasts are increasingly recognised as a valuable tool for higher education (HE) within a wide range of fields (Acevedo de la Peña & Cassany, 2024; Bletscher & Council, 2022; Do et al., 2024). Podcasts are a special modality of electronic learning (E-learning) and can be defined as online or downloadable media recordings accessed from a portable multimedia device (Alam et al., 2016; Lonn & Teasley, 2009). The term ‘podcasts’ originated in the early 2000s, showing a steady increase in listenership since 2013. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, their popularity increased, as individuals sought entertainment, connection, and information during lockdowns (Furtado et al., 2023; Khoury et al., 2025). While podcasts have historically been associated primarily with entertainment and general information, their growing versatility has opened up opportunities for educational uses. This broader landscape warrants clearer differentiation between non-educational and educational applications (Bletscher & Council, 2022; Panagiotidis, 2021).

To establish the educational function of podcasts, it is important to distinguish structured pedagogical uses from general listening practices. Educational podcasts are intentionally designed to meet specific learning outcomes, incorporate instructional scaffolding, and complement formal teaching, whereas non-educational podcasts typically aim to inform or entertain without explicit pedagogical design (Acevedo de la Peña & Cassany, 2024; Moore, 2024). This distinction is central to framing podcasts as a purposeful teaching tool rather than a repurposed media format.

1.2. Educational Applications of Podcasts

In HE, podcasts have increasingly been adopted as pedagogical tools because of their capacity to support learning through auditory engagement, allowing students to process and retain complex information more effectively (Gachago et al., 2016; Siah et al., 2024). For instance, Khoury et al. (2025) report that podcasts are particularly appealing to younger cohorts, who often value mobile and flexible forms of content delivery. Their study shows that exposure to podcasts enhanced comprehension of abstract and conceptually dense material. Gachago et al. (2016) further illustrate that podcasts were used extensively as inclusive resources, particularly in content-heavy modules where students benefited from repeated listening to consolidate memory and deepen concentration. Students reported that they regularly engaged with these recordings throughout the course, finding them both useful and stimulating. Similarly, Siah et al. (2024) emphasise the accessibility of podcasts when distributed via free mobile applications that do not require subscriptions. This model of delivery lowered barriers to participation and allowed students to access episodes directly, thereby encouraging independent and flexible learning. Beyond convenience, podcasts have also been highlighted as a strategy aligned with the principles of Universal Design for Learning. Gunderson and Cumming (2023) argue that podcasts represent a valuable inclusive tool, particularly for students with disabilities, as they diversify available resources and enable engagement with content in non-traditional formats. Their review also suggests that students respond positively to podcasting not only as a means of instruction but also as an innovative assessment format, pointing to its dual potential for both teaching and evaluation.

1.3. Inclusivity, Accessibility, and Pedagogical Limitations

While podcasts have been described as inclusive, it is important to distinguish between inclusivity as a pedagogical aim and accessibility as a practical condition for learner participation. Podcasts can contribute to a more inclusive learning environment by diversifying the formats through which students engage with course content, thereby supporting those who benefit from auditory input or who require flexible modes of study (Gachago et al., 2016). However, podcasts are not universally accessible in their original form, and students with hearing impairments or those who do not favour auditory learning may find them less effective (Yuniarti et al., 2024).

Hence, podcasts primarily serve auditory learners, offering them opportunities to process, retain, and revisit information in ways that complement traditional lecture-based delivery. Their inclusive potential depends on the extent to which educators provide appropriate alternatives or supplementary materials such as transcripts, captions, or multimodal resources (Kurdekar & Sushma, 2020). Without such measures, podcasts risk excluding students whose dominant learning preference or accessibility needs do not align with audio-based formats, illustrating the forms of education segregation described by De Beco (2022). By viewing podcasts as one component of a broader multimodal strategy, their relationship to inclusivity becomes more coherent. Podcasts can enhance inclusion for some learners, provided they are embedded within a learning design that actively mitigates their accessibility limitations (Yuniarti et al., 2024). Integrating podcasts with other delivery modes alongside traditional lectures can foster multimodal engagement in a blended learning environment and support higher-order learning processes consistent with Bloom’s taxonomy (Griffin et al., 2009). In addition to these accessibility concerns, podcasts also present pedagogical limitations, such as students engaging with podcasts superficially or passively (Moore, 2024). Such risks underscore the educator’s responsibility to orchestrate how podcasts are integrated into teaching, ensuring they are embedded within a structured learning design rather than functioning as stand-alone content, as suggested by Kidd (2012).

1.4. Policy and Strategic Framework for AI in Education

Policy discussions increasingly frame AI adoption in education as an issue of pedagogy, ethics, and transparency. UNESCO highlight that generative tools should reinforce student-centred learning, promote self-regulation, and remain embedded within clear human oversight (UNESCO, 2024). The recent UNESCO-UNEVOC research brief by Sturgeon Delia (2025), drawing on insights from European TVET institutions, further stresses that educators require structured support, transparent communication strategies, and opportunities to develop AI literacy alongside their students. These principles align with wider regulatory developments such as the EU AI Act, which places transparency obligations on generative AI (GenAI) content and emphasises accountability in how automated tools are deployed (European Parliament & Council of the European Union, 2024). Such frameworks establish a foundation for interpreting GenAI podcasts not simply as technical artefacts, but as pedagogically mediated tools shaped by ethical and regulatory expectations.

1.5. The Potential of Generative AI in Podcast-Based Learning

Situated within these broader policy and strategic developments, emerging research suggests that GenAI may help address some of the pedagogical challenges of accommodating diverse learning preferences. The application of GenAI in education has gained considerable attention in recent years, reflecting both technological progress and growing adoption. A recent study indicates that students can benefit from AI-generated educational content to a similar extent as from human-generated resources (Denny et al., 2023). Such findings highlight the potential of large language models (LLMs) to improve the accessibility and scalability of high-quality content while reducing the workload placed on educators. In the context of podcasting, AI-generated episodes can be adapted to learners’ needs by providing personalised explanations, simplified summaries, or multimodal supplements such as auto-generated transcripts and interactive quizzes. Khoury et al. (2025) further note that AI-generated podcasts have the capacity to tailor and optimise the learning experience for both educators and students, supporting information digestion and retention through targeted and adaptive delivery.

Despite this emerging evidence, limited research examines how AI-generated podcasts are integrated into HE modules from both educator and student perspectives. Addressing this gap provides a stronger justification for investigating AI-driven podcasting within authentic teaching contexts.

1.6. Study’s Purpose

This pilot practitioner inquiry examines the integration of AI-generated podcasts within an HE research module by attending to two interrelated perspectives: the students’ experience of using the podcasts as a learning resource and the educator’s reflective engagement with designing and implementing the tool. The study aims to understand how AI-driven podcasts contribute to learning from students’ perspectives, and to examine the pedagogical challenges and opportunities that emerge when designing and integrating such podcasts into teaching practice, as interpreted by the educators’ experience. Guided by a qualitative practitioner enquiry approach, the research is structured around the following research questions (RQ):

RQ1. How do students experience, perceive, and make use of AI-generated podcasts as part of their learning?

RQ2. What opportunities, challenges and pedagogical considerations emerge for the educator when designing and integrating AI-generated podcasts into teaching practice?

This pilot practitioner inquiry investigates the integration of AI-generated podcasts within a degree-level module by drawing on the educator’s insider perspective. Practitioner inquiry, as a form of action qualitative research, is situated in studies in which the educator seeks to interrogate and improve their own teaching practices while generating situated insights (Fleet et al., 2016). This approach differs from other qualitative traditions in its explicit integration of practitioner reflection, its focus on pedagogical change, and its conformity to examine emerging educational technologies in contextual classroom settings (Marsh & Deacon, 2025). By highlighting the educator/researcher role, practitioner inquiry enabled systematic attention to the design, implementation, and pedagogical consequences of the podcasts while also supporting a structured examination of students’ experiences of the innovation. Given that AI-generated podcasts are a relatively new pedagogical innovation, this approach enables close examination of how the podcasts function within authentic teaching and learning contexts, and how both students and the educator interpret their usefulness and limitations.

2. Methodology

2.1. Practitioner Inquiry Approach

Practitioner inquiry was adopted as the overarching methodological framework to examine a teaching innovation, the design and implementation of AI-generated podcasts, within the educator’s own instructional context. Marsh and Deacon (2025) emphasise that practitioner enquiry strengthens the connection between inquiry and professional judgement, positioning educators as active knowledge producers whose interpretations of practice shape the direction and value of the research. Such small, context-bound samples are typical of practitioner inquiry, where the aim is to build rich, practice-based understanding rather than to produce statically generalisable findings (Dahlberg et al., 2010; Higgins, 2018). The insight generated here therefore serves as exploratory evidence that can inform future research involving larger cohorts or multiple teaching contexts.

2.2. Context of the Study and Technology Integration

The study took place at a vocational HEinstitution in Malta, within an undergraduate-level module on research and digital skills delivered during the second semester of 2025. The module ran for 14 weeks (February–May), comprising weekly two-hour sessions, supported by asynchronous activities on Moodle, including discussion blogs and online exercises. The cohort consisted of six undergraduate students. AI-generated podcasts were introduced in week 5, coinciding with the release of the minor assignment (due in week 9), to provide structured support during the initial stages of student research. Between weeks five and thirteen, seven podcasts were created and posted in alignment with the teaching sequence: three summarised weekly content, two addressed recurring queries raised in Moodle forums, and two provided targeted guidance for assignment preparation. The podcasts were embedded into weekly teaching from their release onwards and made available on-demand access through Moodle. Their implementation was planned prior to the start of the unit to ensure alignment with the curriculum structure and assessment deadlines. Google’s NotebookLM (https://notebooklm.google.com, accessed on 6 February 2025) was selected to generate personalised AI-powered podcasts. NotebookLM is an AI-driven tool that allows users to upload source materials, such as assignment briefs or readings, and generate summaries, explanations, or podcast-style audio based solely on those uploaded documents. This closed-source workflow ensures that no personal or institutional data is incorporated into the training model. In this study, the educator uploaded selected course materials to NotebookLM, used prompt-based instructions to generate tailored podcast episodes, and reviewed each output to ensure accuracy and alignment with the modules learning outcome.

Using NotebookLM, the educator uploaded selected research articles, book chapters and the assignment brief as source documents, then applied prompt-based instructions to generate podcast episodes tailored to the cohort’s needs. Prompts included the audience (degree students), specifying the tone (casual and supportive), and defining the conceptual focus of the episode. For example, when creating a podcast introducing autoethnography, the educator used the following prompt: ‘Using only the uploaded chapter ‘Introduction to Autoethnography’ by (Adams et al., 2014) as your source, generate a podcast, around 6 to 7 min in duration, for undergraduate conservation students. Explain what autoethnography is, its key features, and why it is considered both a methodological and narrative approach. Use a clear and supportive tone suitable for students encountering the method for the first time, and include one practical example that relates to their area of study (conservation in stone/paper/textiles). To enhance personalisation, some prompts also incorporated reference to queries raised during lessons and research projects students were currently developing. The application then followed the instructional prompts, producing a draft podcast within minutes. All episodes were created solely for the module by the educator, and each output was reviewed, edited, and vetted to ensure accuracy and alignment with the intended learning outcomes. Once finalised, the podcasts were integrated into subsequent lessons as discussion points and later uploaded to Moodle for on-demand access. In total, seven podcasts were created and made available for students throughout the module (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of AI-generated podcasts.

2.3. Data Collection

Data were gathered through two complementary sources:

- (a)

- Student focus group

A focus group was conducted on campus in July 2025, after the unit had concluded and final marks had been released. This timing was intentional to ensure that students did not feel obliged to participate or perceive that their involvement could influence assessment outcomes. Hence, it reduces the potential for power dynamic pressures and reinforces the voluntary nature of participation. Although this delay may have reduced the immediacy of recall, such reflective distance can also support more considered evaluations of learning processes (Krueger & Casey, 2015). The potential influence of this time gap on recall was acknowledged during analysis, and interpretive caution was applied where appropriate.

All six students chose to participate voluntarily. The educator-researcher facilitated the discussion using a semi-structured guide designed to prompt reflections on engagement, perceived benefits, challenges, and experiences of podcast use, an approach consistent with qualitative inquiry into learning processes (Lewis, 2015). The focus group was audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. A survey was considered but not employed, as the study followed a practitioner inquiry approach prioritising depth, reflections, and contextual understanding over breadth (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 2009). Given the small cohort, survey data would have offered limited statistical value and risked duplicating rather than enriching the qualitative accounts. The focus group allowed for exploratory dialogues, clarification, and co-construction of meaning, which are central to understanding learners’ experiences with new pedagogical tools (Krueger & Casey, 2015). The qualitative focus was therefore judged to be the most methodologically appropriate for the aims of this pilot study.

- (b)

- Reflective practitioner notes

Throughout the unit, the educator maintained a reflective journal documenting the workflow for podcast creation, pedagogical decision-making, and observations of student engagement. Reflective notes are widely recognised as valid sources of practitioner-generated data within inquiry-oriented research, enabling examination of instructional decisions and their consequences in situ (Schön, 2017). These notes also captured reflections on the feasibility and sustainability of podcasting as a teaching innovation. To enhance trustworthiness, triangulation was undertaken by comparing focus group data with the educator’s reflective accounts (Heale & Forbes, 2013). Member checking was also conducted with two participating students, who reviewed the interpretations of their contributions to ensure accuracy of representation (Creswell & Miller, 2000).

2.4. Data Analysis

Data were analysed thematically using Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-step approach. The analysis began with familiarisation, during which the transcripts were reviewed to note initial observations about student engagement and the educators’ experience. Deductive coding was then applied, guided by the two RQs, with reflective engagement allowing for the emergence of additional inductive codes. Focus group transcripts (student data) and reflective notes (educator data) were coded separately to maintain the integrity of each dataset. Codes were grouped into broader themes and reviewed across both datasets to identify areas of convergence and divergence. Themes were then refined and defined to clarify how they related to student experiences and educator reflections and subsequently interpreted in relation to the literature and practitioner inquiry framework. NVivo 15 (Lumivero) supported organisation, coding, and retrieval of data, ensuring transparency and consistency throughout the analytic process.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the Malta College of Arts, Science and Technology (MCAST) ethics committee (proposal number I011A_2024). Students were informed that the podcasts were AI-generated, and consent was obtained for their classroom queries and projects to inform podcast prompts. No external individuals had access to the podcasts, and all files were destroyed following their use for the module and research reflection purposes. Participation in the study was voluntary, with informed consent secured from each student. To protect anonymity, no further demographic details are provided throughout the study. Given the small cohort size, and the specificity of the module context, there was a heightened risk of identifiability. To mitigate this, institutional and module names have been generalised, direct quotes have been anonymised, and findings are reported in aggregated form where possible. Moreover, the dual role of educator-researcher was acknowledged, and steps were taken to minimise power dynamics. Data collection occurred only after the module had concluded and marks were published, ensuring that participation had no impact on assessment outcomes. The audio recording of the focus group was securely stored, transcribed, and destroyed thereafter.

3. Discussion of Findings

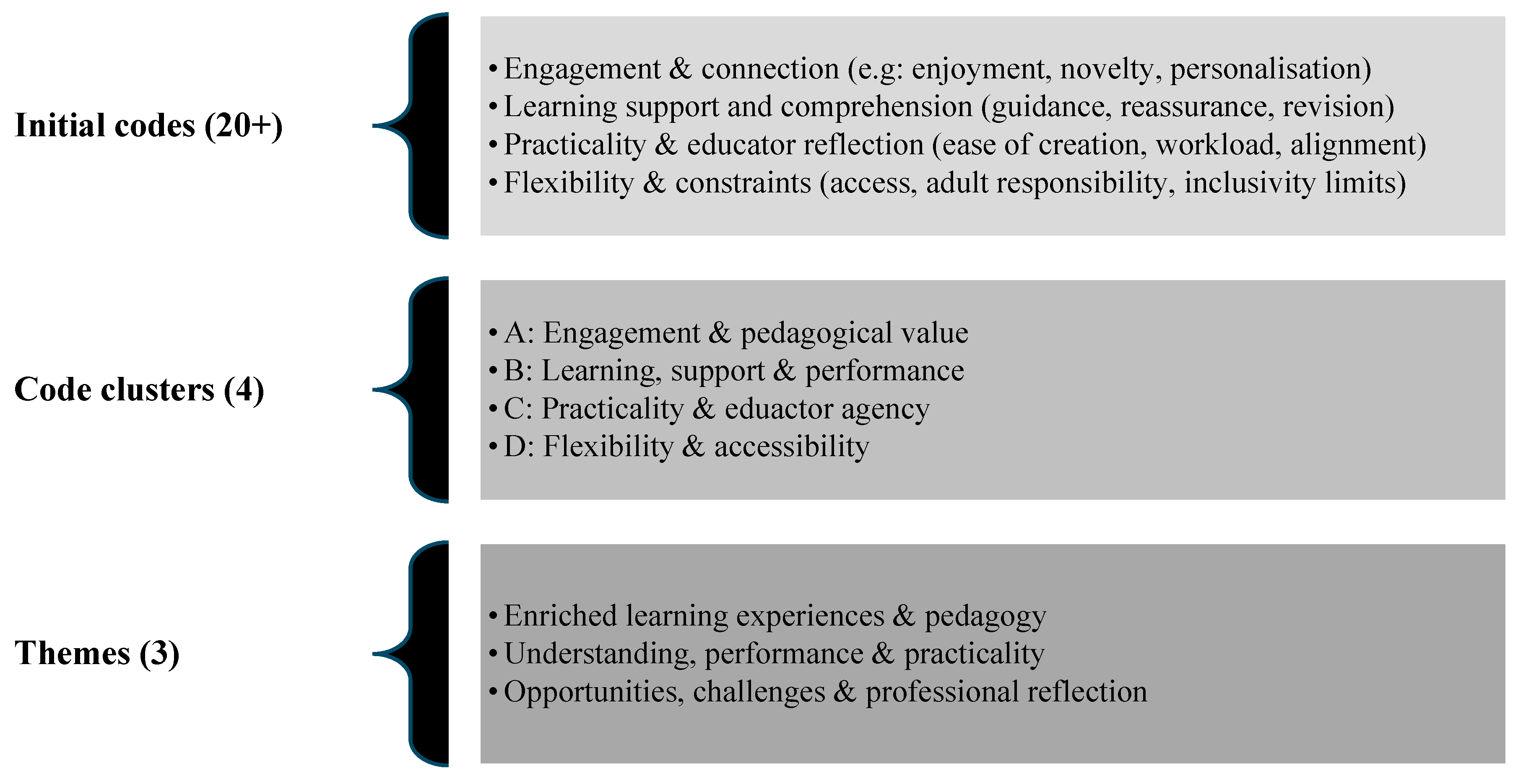

The discussion interprets three themes generated through the coding process, which reflects recurring patterns across student reflections and the educators’ practitioner journal. To move beyond description, the themes were examined in light of the existing literature, the study’s theoretical framing, and the educator’s professional context. This approach recognises that students’ positive reactions and the wider systemic conditions operate together to shape the role of AI-generated podcasts in HE. To illustrate the analytic progression from initial coding to theme development, Figure 1 provides an overview of the coding structure and the relationship between the stages of analysis.

Figure 1.

Representation of the thematic analysis process.

3.1. Theme 1: Enriched Learning Experience and Pedagogy

This theme captures how the AI-generated podcast was experienced as enriching the learning environment and supporting pedagogical intent. Across the data, three interrelated aspects were evident: affective engagement, perceived relevance and connection, and the use of podcasts as scaffolding rather than as standalone content. First, students’ accounts highlighted strong affective responses. The podcasts were repeatedly described as fun, immersive, and a unique way of learning. This affective dimension was closely tied to novelty, as all students were encountering this format for the first time. As one student explained:

‘I think it is a very immersive experience. Being a student usually means focusing on written tasks only, however, when listening to them [podcasts] patiently, I found them very helpful and fun too’(Student 5)

Such responses resonate with existing work which positions podcasts as engaging and relevant tools in HE, capable of sustaining interest in conceptually demanding material (Khoury et al., 2025; Gachago et al., 2016). At the same time, the heavy emphasis on novelty suggests that part of the enthusiasm may be transient, an issue that future work should examine longitudinally. Second, the findings indicate that perceived relevance and connection were strengthened through personalisation. The educator’s decision to embed specific names and queries into the recordings fostered a sense of being addressed directly. One student commented:

‘I liked the fact that the podcast had two voices, like a conversation, and mentioned our names and the difficulties we were having, and how to tackle them. I was always curious about what the podcasts would say’(Students 1)

These patterns align with studies demonstrating that personalised AI-generated podcasts enhance learning outcomes by tailoring explanations to learners’ context (Altinay et al., 2024; Do et al., 2024; Mykhaylenko et al., 2024). In the present study, the practitioner inquiry lens foregrounds the educator’s deliberate design work. She experimented with conversational structure, selected examples that reflected current student concerns, and iteratively adjusted the episodes in response to classroom observations. Third, podcasts were used as scaffolding rather than as a replacement for more traditional materials. The educator consistently framed the recordings to guide students back to slides, notes, and readings, rather than as a shortcut to answers. She reflected:

‘I provide students with a wide range of resources on the VLE- articles, book chapters, YouTube videos, lecture notes and presentation slides. When creating the podcast, I would prompt the AI to refer back to specific notes or presentations, so the recordings reminded students to use those resources. In this way, the podcasts offered scaffolding while also remaining accessible and inclusive’(Educator)

This sits closely with Gachago et al.’s (2016) and Acevedo de la Peña and Cassany (2024) arguments that podcasts can promote active rather than passive learning when integrated with as part of a wider learning design. In this study, students reported using the podcasts for preparation and revision, and classroom discussions became more focused and interactive, suggesting that scaffolding did occur in practice. The educator’s journal notes also recorded immediate behavioural changes. Students listened attentively in class, appeared amused and curious, and temporarily abandoned their phones during the first seven-minute recording. While these observations suggest that podcasts enriched the classroom atmosphere, causality cannot be assumed. The novelty of AI, the timing of the intervention, and the researcher/educator relationship may all have contributed to the observed behaviour. Within the practitioner-inquiry framework, these reflections are treated as situated interpretations rather than generalisable claims.

3.2. Theme 2: Understanding, Performance & Practicality

Theme 2 focuses on how podcasts supported students’ understanding, confidence and performance, alongside the educator’s assessment of the practicality of creating and sustaining the resource. Two main strands were evident: podcasts as cognitive and emotional support for learning, and podcasts as a manageable but additional layer of educator work. Students emphasised that the podcasts helped them to initiate and complete assessed tasks. For those unsure how to begin the first assignment, the recordings provided clarity and structure:

‘The podcast gave me motivation to start the first assignment. Everyone felt a little lost on how to start the assignment, but it gave me motivation to start and gave me guidelines on how to start the assignment’(Student 4)

Others described the podcast as an ‘emotional band aid’, returning to it repeatedly when they felt overwhelmed:

‘For me, it was a revision of the class lesson or a … replacement .... sometimes when I was sick and couldn’t go to lectures, and when I was stuck with an assignment or task, it was my solution, I used to go back to listen to them again and again’(Student 1)

These accounts indicate that podcasts functioned both cognitively and affectively. They consolidated content through repetition and helped manage anxiety associated with assessment. Students also noted that the podcasts offered ‘a different way of understanding’ previous lectures (Student 2), suggesting that the shift to an auditory modality opened alternative routes to understanding. This aligns with previous work showing how podcasts support learners enhance retention and performance (Kidd, 2012; Bletscher & Council, 2022), and with wider work on audio resources as flexible tools for revisiting complex ideas (Panagiotidis, 2021; Yuniarti et al., 2024).

From the educator’s perspective, the podcasts were closely aligned with the module learning outcomes and contributed to the transferability of research skills. One recurrent reflection was the relative ease and speed of production once familiarity with the AI tool had developed. She wrote:

‘I could put together a podcast in less than twenty minutes, often linking it to lecture notes or slides. Each one felt like a way of being present for students beyond the classroom’(Educator)

This echoes with Alam et al.’s (2016) suggestion that simple, intentional design can be integrated efficiently into podcasts without overcomplicating their use. It also aligns with policy discourses that encourage AI tools that reduce technological barriers for educators while complementing existing pedagogies, rather than replacing them. In practice, the educator’s experience in this study suggests that AI-generated podcasts can be incorporated into teaching without extensive technical training, provided there is a willingness to experiment and reflect. However, the practitioner-inquiry stance also foregrounds the constrains involved. The educator acknowledged that preparing, prompting, and editing the AI-generated episodes required time outside scheduled teaching. Continued use was sustained largely because students’ strong uptake and positive feedback made the additional workload feel worthwhile. This raises questions about scalability, in contexts with heavier teaching loads or less autonomy, similar innovations may be harder to maintain.

3.3. Theme 3: Opportunities, Challenges and Professional Reflection

Building on the previous themes, theme 3 extends the focus from immediate classroom benefits to long-term opportunities and challenges. Here, students and the educator move from describing what they did to considering how such tools might fit within broader study practices, AI literacy, and professional norms. Students’ enthusiasm for podcasts not only as a resource but as a potential learning strategy was notable. Some expressed interest in creating their own AI-generated podcasts to aid notetaking and revision. This suggests that the intervention may have opened a space for developing AI literacy, as students began to see AI not only as a background process but as a tool they could deploy creatively. The educator engaged by explaining NotebookLM’s capabilities and limitations, prompting facilitating discussion about trusted AI tools. She reflected:

‘Their interest [students] made me recognise the importance of AI transparency and how we [educators] have the ability to shape the students’ knowledge on trusted AI tools’(Educator)

Within the practitioner-inquiry framework, this reflexive stance is central. The educator’s learning about AI transparency and tool selection is treated as an outcome of the inquiry, not just a result of it. While detailed policy analysis is located in the literature review, it is worth noting that these practices are consistent with current expectations around disclosing AI use and fostering critical engagement with AI-generated content.

The theme also highlights the value of podcasts for flexibility and accessibility. Students described listening at home, on the bus, or before tasks, noting that this allowed them to keep up with the module despite work and family responsibilities. One student observed:

‘I listened to the podcast at home or while on the bus, and it allowed me to catch up with what I might have missed. My home life is hectic, and I do not always find time to revise, but the podcast I could listen to anytime and anywhere.’(Student 3)

Such accounts support prior findings that podcasts and blended approaches can widen participation and accommodate diverse learner schedules (Griffin et al., 2009; Siah et al., 2024). At the same time, students were clear that podcasts could not replace in-person explanations, particularly for complex or technical content. Instead, they positioned podcasts as a supplement ‘alongside other learning material’ (Student 6), echoing literature that treats podcasts as an adjunct rather than a standalone pedagogy (Alam et al., 2016; Do et al., 2024; Gachago et al., 2016).

Students’ recommendations for improvement further underline both opportunities and limits. Requests for captions, visual elements, and longer episodes point to a desire for richer, more inclusive resources. These suggestions align with research indicating that transcripts and multimodal combinations can strengthen accessibility and learning design (Griffin et al., 2009; Siah et al., 2024). The present study deliberately used an audio-only format, which met many students’ needs but did not fully realise this multimodal potential. For the educator, the inquiry exposed professional tensions. She expressed uncertainty about how colleagues might view AI-generated podcasts and noted the absence of local technical support, despite seeking training abroad. Creating and editing episodes represented additional labour not formally recognised in workload models. These reflections resonate with Celik et al.’s (2022) and Luckin et al.’s (2022) observations that many teachers feel underprepared for AI integration and face structural barriers such as limited infrastructure, guidance and time. The practitioner-inquiry approach surfaces these tensions explicitly, showing that positive student reception does not automatically resolve the doubts and practical challenges experienced by educators.

Overall, Theme 3 demonstrates that AI-generated podcasts created new pedagogical opportunities while simultaneously raising questions of legitimacy, sustainability and professional identity. It is in this interplay that the practitioner inquiry generates its most critical insights.

3.4. Implications, Recommendations for Practice, and Limitations

Across the three themes, the analysis suggests that AI-generated podcasts enriched the learning experience by combining affective engagement, scaffolding for understanding, and pragmatic advantages for both students and the educator. Importantly, these benefits emerged through an iterative, reflective process rather than from the technology alone. The practitioner-inquiry framework was instrumental in revealing how the educator experimented, observed, and adjusted her approach in response to students’ feedback and her own professional concerns. Several practical implications arise from these findings. AI-generated podcasts appear most effective when presented in a conversational tone that addresses current student concerns and when they function as scaffolds directing learners back to notes, slides, and other resources. Keeping podcast episodes concise helps minimise cognitive overload, with shorter, more frequent recordings offering an effective alternative to longer formats. Attention to accessibility remains essential, including the use of captions and, where appropriate, complementary visual materials. Finally, transparent communication about the role of AI and routine review of AI-generated content for accuracy are necessary to maintain trust and ensure the pedagogical integrity of the recordings.

As a pilot practitioner inquiry situated within a single module, the study offers contextually rich but non-generalisable insights. The sample was relatively small and composed of adult learners in one disciplinary HE setting, which may limit transferability to other cohorts or programmes. The exclusive focus on audio podcasts means that the study did not examine the impact of combining audio with visual or interactive elements, despite students’ suggestions that such features would be valuable. Moreover, the educator’s reflections represent one practitioner’s perspective and may not capture the range of attitudes or institutional conditions that shape AI adoption in higher education. Future research could extend this work by exploring AI-generated podcasts across multiple modules or disciplines, examining how engagement changes over time once novelty has diminished, and comparing audio-only formats with multimodal or student-generated podcasts. Comparative studies involving several educators could further illuminate how professional identity, institutional culture and support structures influence the uptake of AI-enhanced pedagogies.

Despite these limitations, the present study contributes to the emerging evidence that AI-generated podcasts, when thoughtfully designed and critically reflected upon, can function as complementary, student-centred and ethically transparent resources within higher education.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that AI-generated podcasts can enrich the learning experience, enhance understanding, and support student performance while also generating valuable professional reflection for the educator. Students valued the novelty, accessibility, and flexibility of the recordings, describing them as engaging resources that eased anxiety, motivated learning, and supported revision. From the educator’s perspective, the podcasts aligned well with learning outcomes, encouraged more focused classroom interaction, and were feasible to create, although concerns regarding workload, authenticity, and the absence of institutional support remained. Together, these findings show how AI-generated podcasts can function as scaffolding tools that complement traditional teaching rather than replace it. By examining their use within an authentic HE setting, this study adds empirical insight to the emerging evidence based on AI-generated podcasts and their contribution to students’ learning. Positioning these findings within the wider scholarly context highlights how the bodies of literature connect through this work. Research on podcasting in HE has emphasised its value for processing complex information, supporting reinforcement, and enhancing comprehension, particularly for learners who benefit from mobile and flexible formats (Gachago et al., 2016; Khoury et al., 2025; Siah et al., 2024). Studies on accessibility and inclusive practice underline the importance of diversifying learning resources and offering multiple modes of engagement, noting that podcasts can contribute to more inclusive environments when supported by transcripts or supplementary materials (Gunderson & Cumming, 2023; Kurdekar & Sushma, 2020). In parallel, emerging work on GenAI supports that AI-produced content can offer learning benefits comparable to human-generated materials while enabling personalisation and reducing educators’ burden (Denny et al., 2023; Khoury et al., 2025). The present study extends this developing line of research by offering practice-based evidence on how AI-generated podcasts are understood, experienced, and enacted within an authentic HE setting.

Viewed through the lens of practitioner inquiry, the study also reveals the professional tensions that accompany innovation: while the podcasts offered clear pedagogical value, their sustainability depends on institutional recognition, appropriate safeguards, and educator support. Taken together, the contributions position this study as an early empirical examination of AI-generated podcasting in HE, illustrating its potential to enrich learning in practice-based disciplines when integrated thoughtfully and reflexively.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by The Malta College of Arts, Science & Technology, funding number [DO-RFS_25_18].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Malta College of Arts, Science and Technology (protocol code: I011A_2024; date of approval: 9 July 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study are not publicly available due to privacy and confidentiality requirements. The sample size is small, and the nature of the data means that individuals could be identifiable even after standard anonymisation procedures. As participants did not consent to public data sharing, the dataset cannot be made accessible.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Acevedo de la Peña, I., & Cassany, D. (2024). Student podcasting for teaching-learning at university. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10230/59534 (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Adams, T., Holman Jones, S., & Ellis, C. (2014). Autoethnography (Understanding qualitative research). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, F., Boet, S., Piquette, D., Lai, A., Perkes, C. P., & LeBlanc, V. R. (2016). E-learning optimization: The relative and combined effects of mental practice and modeling on enhanced podcast-based learning—A randomized controlled trial. Advances in Health Sciences Education: Theory and Practice, 21(4), 789–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altinay, Z., Altinay, F., Dagli, G., Shadiev, R., & Othman, A. (2024). Factors influencing AI learning motivation and personalisation among pre-service teachers in higher education. MIER Journal of Educational Studies: Trends and Practices, 14(2), 462–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bletscher, C., & Council, A. (2022). THE POWER OF THE MICROPHONE: Podcasting as an effective instructional tool for leadership education. Journal of Leadership Education, 21(4), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, I., Dindar, M., Muukkonen, H., & Järvelä, S. (2022). The promises and challenges of artificial intelligence for teachers: A systematic review of research. TechTrends, 66(4), 616–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. L. (2009). Teacher research as stance. In The sage handbook of educational action research (pp. 39–49). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W., & Miller, D. L. (2000). Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory into Practice, 39(3), 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlberg, L., McCaig, C., Smith, M., & Bowers-Brown, T. (2010). Different kinds of qualitative data collection methods. In Different kinds of qualitative data collection methods (pp. 111–125). SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Beco, G. (2022). The right to ‘inclusive’ education. The Modern Law Review, 85(6), 1329–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denny, P., Khosravi, H., Hellas, A., Leinonen, J., & Sarsa, S. (2023). Can we trust AI-generated educational content? Comparative analysis of human and AI-generated learning resources. arXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, T. D., Shafqat, U. B., Ling, E., & Sarda, N. (2024). PAIGE: Examining learning outcomes and experiences with personalized AI-generated educational podcasts. arXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament & Council of the European Union. (2024). Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the council of 13 June 2024 on laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence (AI Act). Official Journal of the European Union, 202, 1–131. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1689/oj (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Fleet, A., De Gioia, K., & Patterson, C. (2016). Engaging with educational change: Voices of practitioner inquiry. Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtado, M., Arthungal, J., & Reynolds, A. (2023). Podcast implementation in an entry-level doctor of physical therapy first-semester course: Student perceptions and impact on academic performance. Journal of Educational Research and Practice, 13(1), 270–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gachago, D., Livingston, C., & Ivala, E. (2016). Podcasts: A technology for all? British Journal of Educational Technology, 47(5), 859–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, D. K., Mitchell, D., & Thompson, S. J. (2009). Podcasting by synchronising PowerPoint and voice: What are the pedagogical benefits? Computers & Education, 53(2), 532–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunderson, J. L., & Cumming, T. M. (2023). Podcasting in higher education as a component of Universal Design for Learning: A systematic review of the literature. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 60(4), 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heale, R., & Forbes, D. (2013). Understanding triangulation in research. Evidence-Based Nursing, 16(4), 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempel, S. (2020). Conducting your literature review. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, M. (2018). Engaging in practitioner inquiry in a professional development school internship. School-University Partnerships, 11(2), 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Khoury, Z. H., Sultan, M. S., Tavares, T., Jessri, M., & Sultan, A. S. (2025). AI-generated podcasts for health education. Medical Teacher, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, W. (2012). Utilising podcasts for learning and teaching: A review and ways forward for e-Learning cultures. Management in Education, 26(2), 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R. A., & Casey, M. A. (2015). Focus group interviewing. In Handbook of practical program evaluation (pp. 506–534). Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdekar, S., & Sushma, S. (2020). Visual or auditory: The effective learning modality in multimodal learners. International Journal of Physiology, 8(2), 167–170. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, S. (2015). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Health Promotion Practice, 16(4), 473–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonn, S., & Teasley, S. D. (2009). Podcasting in higher education: What are the implications for teaching and learning? The Internet and Higher Education, 12(2), 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luckin, R., Cukurova, M., Kent, C., & Du Boulay, B. (2022). Empowering educators to be AI-ready. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 3, 100076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, B., & Deacon, M. (2025). Teacher practitioner enquiry: A process for developing teacher learning and practice? Educational Action Research, 33(3), 508–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, T. (2024). Pedagogy, podcasts, and politics: What role does podcasting have in planning education? Journal of Planning Education and Research, 44(3), 1134–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mykhaylenko, V., Safonova, N., Ilchenko, R., Ivashchuk, A., & Babik, I. (2024). Using artificial intelligence to personalise curricula and increase motivation to learn, taking into account psychological aspects. Data and Metadata, 3(1), 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newing, H. (2011). Developing the methodology. In Conducting research in conservation: Social science methods and practice (pp. 43–65). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Panagiotidis, P. (2021, July 5–6). Podcasts in language learning. Research review and future perspectives. EDULEARN21 Proceedings (pp. 10708–10717), Online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R. E. (2020). Qualitative interview questions: Guidance for novice researchers. Qualitative Report, 25(9), 3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, D. A. (2017). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siah, C. J. R., Ang, W. H. D., Ma, W. L. L., Tan, G. R., Yap, A., & Chen, Z. M. (2024). Integration of podcasts in blended learning to expand nursing undergraduates’ learning perspectives on age-related topics. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 72(8), 2627–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturgeon Delia, C. (2025). European insights: Adoption of AI in TVET institutions—Challenges, opportunities and recommendations. UNESCO-UNEVOC. Available online: https://atlas.unevoc.unesco.org/research-briefs/european-insights-adoption-of-ai-in-tvet-institutions-challenges-opportunities-and-recommendations (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- UNESCO. (2024). AI competency framework for teachers. UNESCO. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuniarti, F., Pratiwi, D., & Novianto, R. (2024). Developing podcast-based learning media for english education among deaf students. Voices of English Language Education Society, 8(1), 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).