Abstract

This study explores how teachers’ assessment literacy manifests within assessment practices in higher professional education. While assessment literacy is a multifaceted and dynamic construct, little is known about how it unfolds in practice. Showing how assessment literacy emerges and how its meaning is shaped within assessment-related situations provides nuanced insights for context-sensitive professional development. To gain these insights, teachers’ enactment of assessment literacy was examined in nine diverse assessment-related situations using a conceptual framework comprising eight interconnected aspects. Observations were used beforehand to contextualise the assessment-related situations. Data were then collected through follow-up interviews, each of which began with a LEGO® Serious Play® activity designed to elicit participants’ interpretations. The eight aspects served as the analytical framework to code the data and examine which aspects were present, how they were interpreted, and how they interacted within each situation. The findings demonstrate that different aspects of assessment literacy become more or less prominent, take on different meanings, and interrelate differently within each situation. The study refines the conceptual understanding of teachers’ assessment literacy by illustrating how its manifestations vary within professional assessment practices, showing it as a dynamic, socially situated construct of interrelated aspects.

1. Introduction

Teachers’ assessment literacy (AL) is increasingly recognised as a key element of teaching competence. It is a multifaceted, contextual, and social process that emerges through teachers’ actions and interactions and is continuously interpreted and shaped in practice (Pastore & Andrade, 2019; Willis et al., 2013; Xu & Brown, 2016). Existing conceptualisations, presented in models and frameworks, have advanced the understanding of AL by mapping its different aspects and supporting teacher development (Looney et al., 2018; Meijer et al., 2023; Pastore & Andrade, 2019; Xu & Brown, 2016). However, these conceptualisations emphasise what AL should entail in general, while offering limited insight into its situated manifestations. For instance, a teacher assessing students’ professional performance during internships applies practice-based judgement, whereas a colleague serving on an examination board applies regulatory judgement to ensure compliance with institutional and legal standards. Despite being conceptually well established, for understanding AL’s complexity and for supporting teachers in navigating their assessment practice, empirical insight into how it actually takes shape within teachers’ situated assessment practices is still missing.

Strengthening theoretical understanding and achieving conceptual clarity requires empirical research on how constructs such as AL manifest in practice (De Groot & Spiekerman, 2020). This study focuses on assessment-related situations in higher professional education (HPE), using “teachers” as an umbrella term for lecturers, academics, instructors, and educators. They act in a wide range of assessment-related situations both within and beyond the classroom (Carless & Chan, 2016; Charteris & Smardon, 2022). For instance, they can engage in designing and grading assessments, conduct test evaluations, participate in calibration sessions, implement institutional assessment policies, or attend examination board meetings. Each situation calls for different roles and responsibilities, challenging the understanding of what AL entails. However, the broader range of assessment-related situations that characterise HPE has remained largely unexplored. Understanding how AL manifests in specific situations is important for informing professional development, since it is not a uniform construct but one that must be responsive to the demands embedded in teachers’ practices. Therefore, the aim of this study is to gain insight into how AL is enacted within diverse assessment-related situations in HPE. This study empirically illustrates which aspects of AL emerge in these situations and how teachers interpret them.

1.1. Theoretical Framework

AL is an umbrella term for concepts that are often used interchangeably, such as assessment competence, assessment capacity, or assessment identity (Coombs & DeLuca, 2022). While early definitions focused mainly on technical knowledge and skills for designing and interpreting tests (Stiggins, 1991), more recent perspectives view AL as dynamic and situated in teachers’ everyday work (Xu & Brown, 2016). AL involves understanding assessment principles as well as applying, negotiating, and developing assessment practices in collaboration with colleagues, students, and other stakeholders (Pastore & Andrade, 2019; Willis et al., 2013). Teachers’ interpretations, experiences, and interactions within their professional environment continuously shape AL. It is therefore seen as an ongoing part of teachers’ professional development (Deneen & Brown, 2016; Herppich et al., 2018; Looney et al., 2018; Xu & Brown, 2016). In line with a sociocultural approach, AL is thus viewed as a human activity that emerges from and contributes to practices (Leont’ev, 1978).

Despite these conceptualisations of AL, empirical research has focused on a relatively narrow range of assessment activities, primarily classroom- and test-related assessment (Coombs & DeLuca, 2022). As a result, the broader range of practices that characterise HPE, such as examination boards, calibration sessions, institutional policy work, and accreditation, has remained largely unexplored. These diverse assessment practices make HPE a rich context for exploring how AL manifests in these practices. Pastore and Andrade (2019) also addressed the need to broaden our view of AL in the context of higher education. Their three-dimensional model integrates technical, pedagogical, and sociocultural dimensions, but remains a theoretical contribution, underscoring the need for empirical research on how AL is enacted in practice.

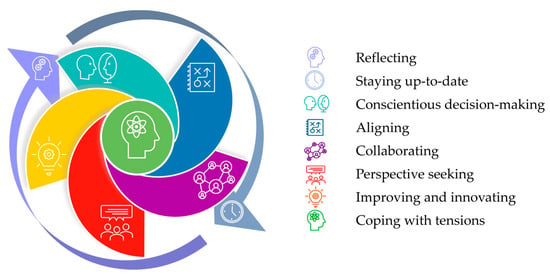

Previous studies have conceptualised AL in HPE through focus groups and survey-based validation (Meijer et al., 2023, 2025). Informed by these studies and related theoretical literature (Flynn et al., 2004; Brookhart, 2011; Fulmer et al., 2015; Xu & Brown, 2016; Herppich et al., 2018; Looney et al., 2018; Pastore & Andrade, 2019), eight interconnected aspects of AL were identified and presented in a windmill model (Figure 1). The aspects can be distinguished but should not be understood in isolation, as they constantly influence and reinforce one another in teachers’ daily practice. This windmill model informed the study, as its aspects capture both classroom-related and broader assessment activities. The model and its aspects are explained in more detail in the following section.

Figure 1.

Windmill model of the aspects of AL by Meijer et al. (2023, 2025).

The first aspect of AL, reflecting on assessment practice, underlines the importance of teachers critically examining their own experiences and actions to identify areas in need of improvement. This is consistent with the literature on teachers’ continuous professional development (Clarke & Hollingsworth, 2002; Evers et al., 2016). For example, after conducting a practical assessment, a teacher might reconsider whether their questions truly allowed students to demonstrate the intended competences, or whether the phrasing unintentionally restricted how students could respond. Over time, such reconsideration might strengthen the teacher’s ability to pose more purposeful questions. This shows how reflection, as a continuous process, constitutes teachers’ AL over time (Desimone, 2009; Webster-Wright, 2009).

The second aspect of AL, staying up-to-date, highlights how teachers engage with new research, developments, or societal changes that affect assessment practice (Clarke & Hollingsworth, 2002; Webster-Wright, 2009). For instance, an HPE teacher attends a seminar on generative AI to learn how emerging tools might affect assessment design, integrity, and student work. Actively keeping up with new developments is increasingly seen as a crucial aspect of AL (Antera, 2021).

The third aspect, conscientious decision-making, refers to teachers’ ability to make careful, well-justified choices within the assessment practice (Brookhart, 2011; DeLuca & Johnson, 2017; Herppich et al., 2018). Bearman et al. (2016) emphasise that assessment should be understood as involving multiple complex decisions that go beyond individual assessment tasks. This aspect thus applies not only when designing and conducting individual assessments but also when shaping assessment policies, coordinating program-level assessment strategies, and ensuring coherence across modules and programmes.

The fourth aspect, aligning educational components, highlights the need for coherence among curriculum aims, professional standards, institutional policies, and constructive alignment between assessments and learning activities or course content (Biggs, 1996; La Marca, 2001; Näsström & Henriksson, 2008; Sluijsmans & Struyven, 2014). Ensuring alignment strengthens the relevance, fairness, and transparency of assessment practice (Webb, 2002).

The fifth aspect, collaborating within the assessment practice, recognises that HPE teachers work together with various stakeholders, including students, colleagues, programme managers, workplace supervisors, and employers. This aspect emphasises building shared understandings and expectations within the assessment practice. AL is shaped through these interactions. Collaboration enables clarifying shared standards, interpreting criteria consistently, and aligning judgments (Bråten et al., 2017; Desimone, 2009; Pastore & Andrade, 2019). A common example is calibration, where student work is discussed to reach agreement on the level of student performance in authentic, holistic tasks (Malau-Aduli et al., 2021; McTighe & Emberger, 2006).

The sixth aspect, seeking perspectives, highlights the importance of actively exploring alternative views and ideas to question habitual ways of working (Obsuth et al., 2022). While collaboration often reinforces shared practices, perspective taking involves deliberately exposing oneself to different viewpoints on assessments that may challenge existing assumptions (Xu & He, 2019). For instance, programmatic assessment typically emerged as a new educational concept in countries such as Australia and the Netherlands because researchers and HPE teachers sought an alternative perspective on assessment: rather than viewing reliability as consistency within a single assessment, they reframed it as trustworthiness built across multiple low-stakes assessments and professional judgments over time (Baartman & Quinlan, 2024).

The seventh aspect, improving and innovating the assessment practice, refers to teachers’ commitment to enhancing the quality of assessment through ongoing cyclical processes such as the assessment cycle or plan–do–check–act models (Gulikers et al., 2021; Reinholz, 2016). This means regularly planning, implementing, evaluating, and refining the assessment practice to ensure it remains valid, reliable, and fit for purpose (Forsyth et al., 2015). It also reflects teachers’ willingness to experiment with new approaches, for example, piloting alternative forms of assessment or adopting digital systems to monitor student progress more effectively.

The eighth aspect, coping with tensions, acknowledges that the aspects of AL can sometimes pull in different directions. Teachers often need to balance competing priorities. For example, efforts to innovate may come into conflict with established institutional regulations, requiring them to negotiate workable compromises (Lock et al., 2018; Xu & Brown, 2016). As Xu and Brown (2016) describe, managing such tensions is central to AL in practice. Such tensions have the potential to either hinder or drive professional development (Charteris & Dargusch, 2018; Schaap et al., 2019).

The eight aspects of AL are visualised in a windmill model (Meijer et al., 2023), which illustrates their interconnectedness. Each blade of the windmill represents one of five core aspects: conscientious decision-making, aligning educational components, collaborating within the assessment practice, seeking different perspectives, and innovating and improving. The aspects of staying up-to-date and reflecting are conceptualised as the wind that keeps the blades turning, since they are often described as essential elements of teachers’ continuous professional development. The aspect of coping with tensions is depicted as the pin of the windmill: when it becomes too tight, the windmill may stall. Nevertheless, the literature often highlights tensions in practice as potential triggers for professional learning (Charteris & Dargusch, 2018; Lock et al., 2018; Schaap et al., 2019), which also justifies their central placement in the model.

Identifying the core aspects of AL risks reducing variation to broad categories and making situated differences less visible. This limitation became particularly evident in a validation study. In that study, large-scale analyses tended to mask variation, as skewed distributions were obscured by the emphasis on model fit (Meijer et al., under review). Such a reduction may inadvertently suggest that teachers need to master all aspects of AL equally and at all times. In reality, not all aspects might be relevant in every situation or might hold a different meaning depending on the situation.

To address this limitation, the aim is to illustrate how AL manifests in practice. Each manifestation represents a situated expression of AL as a whole, composed of the aspects at play, their interpretations, and interrelations within a specific situation. The situation provides the context in which AL takes shape. A manifestation thus captures how AL is interpreted and expressed, both in its individual aspects and in their situated interconnections within a particular context. Accordingly, based on the windmill model (Figure 1), the following research questions were formulated:

- What aspects of AL emerge in assessment-related situations in HPE?

- What are HPE teachers’ interpretations of these aspects within each assessment-related situation?

- How does the interplay between these aspects manifest in teachers’ activities within each assessment-related situation?

1.2. Context of This Study

The research is conducted within the context of Dutch Universities of Applied Sciences (UASs), which offer higher professional education (HPE) at ISCED levels 5–7. A distinctive feature of this context is its strong connection with the professional field: assessment practices are deeply rooted in vocational practice and closely aligned with the demands of the labour market (Antera, 2021; de Bruijn et al., 2017). Teachers and professionals collaborate to ensure that assessments qualify graduates for professional practice within their chosen vocation (van Houten, 2018). HPE teachers usually enter teaching from their original profession and, in some cases, continue to practice their vocation alongside their teaching (Grollmann, 2008). This dual identity shapes their approach to assessment, as they also draw on workplace perspectives and practices (van Renselaar et al., 2025). Furthermore, HPE teachers have significant autonomy to design and implement their curricula, including assessments (de Bruijn et al., 2017). Consequently, their assessment practice extends well beyond the classroom and encompasses a wide variety of assessment-related situations (Carless & Chan, 2016; Charteris & Smardon, 2022).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The methodological design is guided by a sociocultural perspective that views AL as an embedded human activity shaped by situations and interaction. Teachers’ AL is thus shaped not only by situational demands but also by teachers’ backgrounds, experiences, and interactions (Looney et al., 2018). Phenomenographic approaches, which seek to describe the qualitatively different ways AL is enacted in practice, informed the methodological design. They were drawn upon to capture this situated variation (Akerlind, 2024; Marton, 1981; Svensson & Doumas, 2013). Accordingly, diverse assessment activities were observed, and participants’ narratives were elicited to explore how HPE teachers enact and interpret AL within those situations. The data were coded in Atlas.ti 25 (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany) using the eight aspects to explore how these were manifested and interpreted within the various situations.

While in many qualitative studies researchers seek saturation and theme development through inductive analysis, the purpose of this study was to seek variation to illustrate the diverse manifestations of AL, prioritising diversity and richness over completeness. Based on the principle of information power by Malterud et al. (2016), which emphasises that the value of qualitative data lies in the relevance and insight each case contributes rather than in the sheer number of cases, eight to ten assessment-related situations were estimated to provide sufficient breadth to capture a wide range of variation in teachers’ AL. In the end, nine situations were included.

2.2. Selection of Situations and Participants

Situations and participants were recruited through network sampling and personal contact. The researchers approached teachers within their professional network in the Dutch National Assessment Literacy Network. When relevant, were referred to additional teachers through these contacts. The participants were purposefully selected to represent a wide variety of assessment-related situations and to ensure maximum variation in situations and contexts (Hays & Singh, 2023). When teachers expressed interest in participating, they received an information letter and were invited to discuss potential assessment-related situations. To ensure the possibility of new or complementary insights, consistent with the principle of information power (Malterud et al., 2016), the proposed situation was explored prior to participation to determine how it differed from those already included. For example, once an examination board meeting was observed, this type of situation was not included again. In two potential cases, participation did not proceed for this reason. The assessment-related situations were selected from four different Universities of Applied Sciences in the Netherlands and across different study programmes to maximise potential variation. Before the observation, participants signed the informed consent form. Participation did not have any consequences, and participants were free to withdraw at any point. Table 1 provides short descriptions of the assessment-related situations and participants’ characteristics.

Table 1.

Descriptions of the assessment-related situations and participants’ characteristics.

2.3. Data Collection

The data collection process consisted of three steps: a preparatory step and two subsequent steps. As a preparatory step, observations were conducted. These observations served not as data for analysis but as a contextual tool to prepare for the follow-up interviews. Their purpose was to develop a clear and shared understanding between the participant and the researcher of the situation discussed in the follow-up interviews. Each situation was observed by at least one of the researchers (first and second authors) and video-recorded. This allowed the interviewer to refer to specific examples and explore relevant aspects in depth. In addition, the observations supported the interviewer and the participant in staying focused on what was part of the situation. During the observations, the researchers used an observation form with a timeline to note key moments. This procedure made it possible to later refer to specific video segments to support participants’ recall during the interviews. Because the observations served only to contextualise the interviews and were not transcribed, they are included indirectly in the data. Steps one and two followed immediately after observing the assessment-related situation, or in one case on the same day, to ensure that the situation was still fresh and vividly remembered by the teacher.

Step one involved using LEGO® Serious Play® to support the participants in transitioning from the situation to the interview and to elicit teachers’ conceptual understandings of AL (Kriszan & Nienaber, 2024; Rose & Furness, 2024). This was piloted before actual use in the interviews. To address the research question, participants needed to shift perspective, moving from focusing on their participation in the assessment-related situation to reflecting on the underlying construct of AL. LEGO Serious Play provided a way for teachers to shift from what had just happened to reflecting on the construct of AL. Diverse LEGO blocks in various colours, shapes, and functions were provided to support metaphorical associations and creative expression. This is consistent with Rose and Furness’s (2024) observations on the value of LEGO Serious Play in helping participants find words for abstract concepts through the associative function of the blocks. Participants were asked to create a LEGO model representing their AL in the preceding situation. A ten-minute timeframe for the LEGO activity proved sufficient for participants to build and explain their models. The builds were explained in response to an open invitation, without further direction being given. Participants often explicitly referred to the aspects by name in their builds. These were then further discussed and elaborated during the interviews in step two. Their explanations were audio-recorded and included as data for the analysis, enabling the reconstruction of how AL manifested in each situation.

Step two involved interviewing, which was chosen because teachers’ AL is often not fully reflected in observable behaviour (Xu & Brown, 2016). At the start of the interview, the eight aspects were briefly introduced to provide a shared frame of reference. Conversation cards, each representing one aspect, were used as prompts. Because the LEGO activity in step one enabled participants to articulate their own interpretations first, the interviewer could probe more purposefully in step two without steering the discussion. Participants were asked to select the aspects they recognised within the situation and to assign meaning to them by explaining how each manifested. The aspects they did not choose were discussed afterwards to consider whether and how these might still have been relevant to the situation. In almost all interviews, participants spontaneously arranged the cards on the table, comparing and connecting the aspects of AL. In that way, the cards were used to explore patterns and relationships between aspects. These interviews were also audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and included in the dataset for analysis. The option to review specific parts of the recording was not applied, as both the participant and the researcher appeared to recall the situations sufficiently. At the end of the interviews, participants were asked if they felt any aspect was missing; none of them indicated that this was the case.

2.4. Analysis

The entire conversation, comprising both the narrative of the LEGO® build and the subsequent interview, was audio-recorded and transcribed as one dataset, with the LEGO® building serving as an initial open question rather than a separate data source. The transcript was analysed as a whole, with codes applied across the complete interview to explore how AL manifested and was interpreted within the situation. The eight aspects of AL were used as codes to organise the text fragments corresponding to each aspect, supplemented by a “relation between aspects” code when participants articulated links between two aspects.

The first transcript was double-coded independently by two researchers (the first two authors) to ensure consistency in coding relevant text fragments under the respective aspects of AL. The unit of analysis was each text fragment in which participants described an aspect of AL or articulated a relation between aspects. Such fragments could occur in either the LEGO® narrative or the subsequent discussion. When a fragment referred to more than one aspect, it was coded under multiple aspects, in line with the conceptual model, which acknowledges that the aspects may overlap. Whenever participants indicated relations or overlaps between aspects, these were coded as ‘relation between aspect X and aspect Y’. These relations were examined within each situation to contextualise how the aspects interacted in practice. After agreement was reached, each of the two researchers individually coded four of the remaining transcripts.

Each situation was subsequently analysed separately to provide a contextualised description of how AL was enacted in that specific assessment-related situation. After coding the text fragments, the two researchers discussed how the fragments described the manifestations of the aspects of AL within each situation. Comparisons across situations were avoided; instead, the descriptions of AL remained close to the source data, describing how participants articulated AL within their specific situations. Finally, the fragments derived from participants’ explanations while constructing the pattern with the cards, together with the codes indicating relations mentioned during the interview, informed the creation of the individual windmill presentations. These presentations visualise how the aspects manifested within each assessment-related situation.

2.5. Use of Writing Support Tools

To support the drafting and refinement of several discussion paragraphs, ChatGPT was used (OpenAI, 2025; Model GPT-5.1). Prompts were written by the authors, and all AI-generated text was critically reviewed and edited to ensure accuracy and alignment with the empirical findings and theoretical framework. Grammarly (Grammarly Inc., 2025; Version 1.2.215.1793) was used to check grammar, spelling, and style; the authors reviewed all suggestions before acceptance.

3. Results

Descriptions of the situations and participants are provided in Table 1, offering context for the findings that follow. The results are presented in three parts, following the research questions that guided this study. First, the aspects of AL that emerged within each situation are presented. Second, teachers’ interpretations of these aspects within their specific situations are described. Finally, the interplay between these aspects is illustrated as they became visible in each assessment-related situation.

3.1. Aspects of AL Emerging in Acting in Assessment-Related Situations in HPE

Not all aspects of AL were present in every observed situation (Table 2). In some situations, multiple aspects are in play simultaneously, whereas in others, only a few aspects manifest clearly. When the interviewer asked specifically about aspects that had not been mentioned, participants generally confirmed that they recognised these aspects but did not see them as manifest in the situation at hand. For example, participant two said: “There was no tension this time, because it was just a small group on the resit. … But when I analyse larger groups, that’s when people start asking, ‘Why did you decide this?’ or ‘This is very inconvenient for my students. Then there’s more at stake, and I might have to cope with possible tensions”.

Table 2.

Emerging aspects of AL within each situation.

The aspects reflecting and staying up-to-date often did not manifest within the situation itself or were only very modestly present. However, in situation seven, where the participant was engaged in a formal professionalisation trajectory, these two aspects became particularly explicit (Table 3). In this situation, reflection even encompassed additional aspects that did not manifest within the situation but emerged through deliberate reflection. This illustrates that aspects of AL that were not considered meaningful in a specific situation might remain latent rather than absent.

Table 3.

Examples illustrating the variety in interpretations of AL.

3.2. HPE Teachers’ Interpretations of the Aspects of AL Within the Situations

Given the extensive nature of the results, Table 3 presents an abbreviated version of the manifestations as described in the Supplementary Materials. In this table, two examples of HPE teachers’ interpretations of AL per aspect were randomly selected from different situations in which they were enacted. These examples serve to illustrate the diverse ways in which teachers interpreted aspects of AL in practice. They are thus illustrative rather than exhaustive. For instance, conscientious decision-making in one situation involved deliberately withholding judgement and giving the student space to speak first, whereas in another situation it meant deciding on how to communicate advice to the management team and other relevant stakeholders.

The interpretation of one aspect coloured the meaning of the other aspects in play. This was expected: aspects overlap and are inherently relational, so they inevitably shaped each other’s meaning (Meijer et al., 2023). This was particularly apparent in situations where one aspect was considered central. For example, in situation five, assessing a student’s live performance in a clinical setting foregrounded conscientious decision-making. In this situation, this aspect shaped how the teacher interpreted aligning: decisions were explicitly tied to the intended learning outcomes. It also shaped the interpretation of perspective seeking, as the teacher actively invited the student and colleagues to share their viewpoints before forming a judgement.

Two other situations (six and eight) illustrated how the presence of tensions constrained the meaning of aspects or even gave them negative connotations. In situation six, the calibration session, unclear or conflicting interests made collaboration feel more procedural than genuinely interactive, and perspective seeking more defensive. In situation eight, where teachers developed curricular options for implementing an interprofessional course, coping with tensions was linked to the top-down pressure of implementing an externally organised course. This tension was, for instance, reflected in the manifestation of aligning, as the participant felt limited in how openly they could weigh different options and stakeholder interests. By contrast, in situation three, where teachers discussed the implications of the university-wide assessment policy, collaborating was manifested as open and constructive, contributing to an atmosphere where tensions did not arise at all. These examples illustrate that interpreting one aspect shaped how others manifested in practice, sometimes constraining them and at other times supporting them.

A specific example that illustrates the variety in how AL manifested in practice is situation seven. In contrast to the other assessment-related situations, where AL emerged within an assessment-related situation, this was a professionalisation activity explicitly designed to develop AL. Reflecting and staying up-to-date were found to be the two aspects of AL in play, constituted through other aspects. For example, the teacher reflected on their conscientious decision-making, collaborating, and updating their knowledge and skills related to enhancing and innovating the assessment practice. This situation showed that other aspects implicitly shaped how reflecting and staying up-to-date were interpreted.

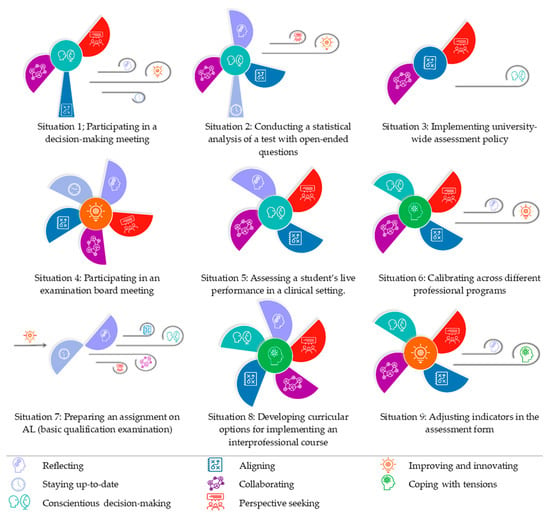

3.3. The Interplay Between Aspects of AL in Teachers’ Activities Within Assessment-Related Situations

To explore the interplay of the aspects of AL, both the participants’ arrangements of the cards on the table and their explanations of these arrangements, as well as other relations they mentioned during the interviews, were examined. For example, participant five connected conscientious decision-making and collaborating: “I was very deliberate about having a careful conversation and making thoughtful decisions together about which learning goal to focus on now, as this would allow me to tailor my feedback more closely and pay closer attention to that in the judgment process. I also discuss this with the fourth-year coach, so that we can align our feedback and observations accordingly”. The windmill model of the theoretical framework was used to visualise the variations in the manifested interrelations between the aspects of AL (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Visualisations of manifestations of AL, based on the windmill model of Meijer et al. (2025).

In many assessment-related situations, a specific goal was experienced as central. For instance, in situation one, where the participant was involved in a decision-making meeting, the central goal was to determine the students’ level of performance. These central goals placed one aspect of AL in the foreground. This illustrates how the aspects continuously influence each other, depending on the specific demands, interactions, and conditions of the assessment-related situation in which they unfold.

In two situations, an aspect of AL was understood as a prerequisite for participation, represented as a central pillar of the windmill that holds the blades in place and enables them to turn (Figure 2). In situation one, a high-stakes decision meeting, the participant needed to be very familiar with the expected performance level, the design of the assessment programme, and the standards for evaluation to make a fair judgement. Without this alignment, the other aspects of AL could not come into play meaningfully. In situation two, staying up-to-date was perceived as a fundamental prerequisite for participating in the test analysis: the participant needed to have current knowledge of statistical procedures, the subject matter, the lessons taught, and the specific test questions beforehand to accurately interpret the data and adjust grades accordingly. In both situations, the required aspect formed the foundation for the enactment of AL in practice.

Furthermore, each situation represented just one moment within the ongoing assessment process. One aspect emerged as a starting point in situation seven. The aspect of improving and innovating was an explicit assignment: the participant’s task was to develop an innovation plan for assessment, making this aspect the input that set the windmill in motion. Other aspects often emerged as outcomes. In situation six, for instance, reflecting was not manifested during the calibration session. Still, the participant recognised it as manifesting afterwards, when revisiting how the meeting went and how they might adjust the procedure. Similarly, the aspects reflecting in situations one and nine, and staying up-to-date in situations one, two, and six were recognised as manifesting afterwards. Participants looked back on the assessment-related situation and drew lessons for future practice. This input–output dynamic is visualised in Figure 2, where the arrow sets the windmill in motion and the ‘wind curls’ represent the outcomes.

4. Discussion

From a sociocultural perspective, it matters how AL manifests in practice, within specific situations, because its meaning is constructed in context. Building on this perspective, the discussion begins by addressing the three research questions in sequence. First, it addresses which aspects of AL emerged within the situations. Second, the understanding of how teachers interpreted these aspects in practice is considered. Third, the interplay between different aspects of AL manifested in practice, an area that has been theorised but not yet empirically demonstrated, is elaborated.

First, the findings indicate that while AL as a construct is constituted by all aspects, its salience in practice varies depending on the assessment-related situation. This resonates with research on teacher professional development showing that different dimensions of teachers’ expertise become salient in particular situations rather than being uniformly enacted across contexts (e.g., Clarke & Hollingsworth, 2002; Webster-Wright, 2009). Similarly, the results show that not all aspects of AL were recognised within the nine situations. The findings align with a sociocultural understanding of AL as emerging dynamically within specific situations as well (e.g., Looney et al., 2018; Pastore & Andrade, 2019; Xu & Brown, 2016), contrasting with more generalised conceptualisations that treat AL as a static or universal set of aspects (DeLuca & Johnson, 2017; Fulmer et al., 2015). However, these studies do not empirically detail how specific aspects become more or less salient in practice. The present study adds to this by empirically showing which aspects of AL emerged across the nine assessment-related situations.

The absence of a particular aspect within a given situation reflects how teachers framed what was relevant in that context, rather than indicating a lack of competence. As illustrated in the findings, participants often acknowledged other aspects of AL but described them as not being manifest in the specific situation at hand. This interpretation is consistent with the phenomenographic aim of capturing variation in experience (Åkerlind, 2008, 2025; Marton, 1981). Illustrating these variations and showing which aspects of AL are at play in the nine assessment-related situations, provides a basis for more context-sensitive discussions among researchers, teachers, and other stakeholders. In addition, it can inform professional development that acknowledges the situated diversity of AL by enabling teachers to identify which aspects of AL matter in particular assessment-related situations and to reflect on how these aspects can be strengthened or supported within the situations they encounter.

Second, the findings provide empirical evidence that teachers’ interpretations of aspects of AL are highly situational. This also resonates with research on teacher professional development, showing that teachers’ meaning-making is shaped by the situations they encounter (e.g., Clarke & Hollingsworth, 2002; Webster-Wright, 2009). The interpretations varied depending on the specific characteristics of each assessment-related situation. This contextual variation substantiates research conceptualising AL as a dynamic and situated construct emerging through teachers’ interactions and practices (Deneen & Brown, 2016; Looney et al., 2018; Pastore & Andrade, 2019; Willis et al., 2013; Xu & Brown, 2016). It illustrates how such situated interpretations of the aspects of AL take shape in practice. Such variation in meaning has implications for AL development: it suggests that strengthening AL is not only a matter of deepening assessment knowledge, but also of supporting teachers in recognising, negotiating, and expanding the situated meanings these aspects take on in their practice. This highlights the importance of professional dialogue that allows teachers to articulate, share, and reflect on how they understand and enact AL in different situations.

Third, the visualisations of the windmill constellations address a gap in the AL literature. Existing studies suggest that AL aspects are interrelated and collectively shape teachers’ assessment practices, yet this remains largely a conceptual claim. The visualisations make these relations between aspects visible at the level of specific situations. The interplay between aspects revealed AL as a dynamic construct. It was manifested through varying constellations of aspects that related to one another differently within each assessment-related situation. In two situations, one aspect was described as conditional, forming the foundation upon which others were enacted. In others, a single aspect was placed at the centre and shaped those around it; whereas in one case, no aspect was given such a central status. These constellations indicate that AL manifests not only through the presence of individual aspects but also through the ways in which they interrelate. While previous studies have primarily conceptualised AL as a collection of dimensions or components (e.g., Looney et al., 2018; Meijer et al., 2023; Pastore & Andrade, 2019), the present study adds that the coherence and relative positioning of aspects within situated practice are equally important. Visualising these constellations (Figure 2) provides a richer understanding of AL as a dynamic construct that reflects the contextual nature of teachers’ assessment practices.

In ordering the aspects, it became clear that some aspects were not recognised within the situation itself but rather as processes that continued afterwards. This is illustrated by the windcurls in Figure 2. Although the situations were bounded activities, the presence of such windcurls indicates that teachers’ enactment of AL extends beyond the temporal boundaries of a single assessment-related situation and continues through subsequent processes of meaning-making. For example, reflection may stretch over time beyond the observed activity. This suggests that while manifestations of AL are situated in specific assessment-related contexts, they are also part of a longer process of professional development in which teachers continually reinterpret and reorder their assessment experiences. This finding resonates with research that conceptualises professional competence as both contextually embedded and continuously developing (Looney et al., 2018; Webster-Wright, 2009).

Among the methodological choices that shaped these findings, the LEGO build activity at the start of the interviews proved particularly valuable. As noted in recent research, the constructive ‘build, share, listen’ process of LEGO Serious Play holds considerable potential for qualitative interviews. It can foster flow, support metaphorical expression, and access tacit knowledge (Kriszan & Nienaber, 2024; Rose & Furness, 2024). In this study, it facilitated a shift from being immersed in the assessment-related situation to conceptualising AL. The use of LEGO enabled participants to visualise and externalise their thinking. This process proved helpful in preparing participants for the interview that followed, allowing them to enter the conversation with a focused mindset. It also elicited rich insights that may not have surfaced through conventional verbal methods alone. Rose and Furness (2024) and Kriszan and Nienaber (2024) emphasise the need for careful facilitation to ensure meaningful participation. Participants’ ready engagement suggested effective facilitation. The wide range of LEGO bricks encouraged them to begin building. This LEGO build activity illustrates the potential of creative methods to support teachers in giving meaning to theoretical constructs that are situated in professional practice.

Another methodological consideration concerned the deliberate focus on variation rather than representativeness. This approach is consistent with qualitative methodological traditions that seek to capture the range of possible ways in which a phenomenon is experienced, rather than aiming for saturation or statistical generalisability (Åkerlind, 2008; Marton, 1981). It also aligns with the principle of information power, which emphasises that relevance and diversity determine the strength of qualitative data (Malterud et al., 2016). The included situations provide a comprehensive and contextually rich picture of how AL can manifest within diverse assessment-related situations, yet the findings are not intended to be generalisable to other situations or beyond the HPE context. Future research on teachers’ AL in practice could examine how common or distinctive the included assessment-related situations are, as well as how AL manifests within other educational contexts.

The findings have implications for both practice and research. Practically, engaging teachers in analysing which aspects of AL emerge within a given situation, and how these aspects interrelate, may enable them to reflect on their assessment practice and identify what supports or challenges their enactment of AL. Such analysis can help teachers articulate how specific aspects of AL take shape in their context and discuss how these can be strengthened, whether through collegial dialogue, updating their knowledge, or addressing tensions in their assessment practice (Charteris & Dargusch, 2018; Lock et al., 2018; Xu & Brown, 2016). Being able to articulate aspects of AL is important because it enables teachers to make their professional reasoning explicit and to identify what supports or constrains their assessment practice. For instance, recognising that conscientious decision-making or coping with tensions play a central role in a given context can guide the type of professional support, collaboration, or institutional resources that are required. These insights suggest that efforts to foster AL in HPE should go beyond formal training to include opportunities for teachers to collaboratively explore and reflect on the contextual and relational complexities they encounter in authentic assessment practice.

Scientifically, by “grasping” the aspects at play, the enactment of AL within specific assessment-related situations could be captured. This contributes to the conceptual refinement of AL by illustrating possible manifestations, providing a more nuanced and situated understanding of the construct. Future research could build on this in several ways. For instance, studies might examine how manifestations of AL develop over time, exploring whether and how teachers’ interpretations and constellations of aspects of AL evolve through formal training, organisational change, or repeated engagement in particular assessment practices. Another interesting direction could be comparative research across programmes, institutions, and national contexts. Such studies could help establish which manifestations are situation specific and which patterns may recur across settings, foregrounding conceptual saturation in identifying recurrent forms of enactment. Futhermore, methodological work could explore how visualisation techniques, such as the windmill constellations used in this study, can be applied beyond analysis. For example, future research might examine how such visualisations support collaborative inquiry among teachers, enhance reflective dialogue, or be integrated into professional development interventions aimed at helping teachers articulate and explore the dynamics of AL in their own practice. Taken together, such studies would help to further contextualise AL as a situated construct.

5. Conclusions

Guided by a sociocultural perspective that views AL as a human activity situated in practice and shaped by interaction, this study refines the understanding of AL. It demonstrates that teachers’ AL is a dynamic construct of interrelated aspects, with manifestations varying within situations. The findings show that not all aspects of AL are equally relevant in every assessment-related situation and that their interpretations and interrelations differ accordingly. This addresses a limitation in studies that focus on identifying core aspects, which risks reducing variation and masking the situated meanings of AL. This study provides a more nuanced understanding of AL, which can inform theory development and support context-sensitive approaches to teacher professional development. Given the limited empirical insight into situated manifestations of teachers’ AL, continued research is essential to enhance our understanding and the meaningful use of this concept within contexts.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/educsci15121644/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, all authors; software, K.M. and C.G.; validation, all authors; formal analysis and investigation, K.M. and C.G.; resources, all authors; data curation, K.M.; writing—original draft preparation, K.M.; writing. Review, and editing, C.G., L.B., M.V. and E.d.B.; visualization, K.M.; supervision, L.B., M.V. and E.d.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee (cETO) of the Open University of the Netherlands (RP900/U202407968, 21 October 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The descriptions supporting the findings in Table 2 are presented in Supplementary Materials of the article. The original qualitative data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions, as they contain information that could lead to the identification of participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AL | Assessment Literacy |

| HPE | Higher professional education |

References

- Akerlind, G. S. (2024). Phenomenography in the 21st century: A methodology for investigating human experience of the world. Open Book Publishers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antera, S. (2021). Professional competence of vocational teachers: A conceptual review. Vocations and Learning, 14(3), 459–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åkerlind, G. S. (2008). A phenomenographic approach to developing academics’ understanding of the nature of teaching and learning. Teaching in Higher Education, 13(6), 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åkerlind, G. S. (2025). Why should I be interested in phenomenographic research? Variation in views of phenomenography amongst higher education scholars. Higher Education, 89(5), 1235–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baartman, L. K. J., & Quinlan, K. M. (2024). Assessment and feedback in higher education reimagined: Using programmatic assessment to transform higher education. Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education, 28(2), 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearman, M., Dawson, P., Dawson, P., Bennett, S., Hall, M., & Molloy, E. (2016). Support for assessment practice: Developing the assessment design decisions framework. Teaching in Higher Education, 21(5), 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, J. (1996). Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. Higher Education, 32(3), 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bråten, I., Muis, K. R., & Reznitskaya, A. (2017). Teachers’ epistemic cognition in the context of dialogic practice: A question of calibration? Educational Psychologist, 52(4), 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookhart, S. M. (2011). Educational assessment knowledge and skills for teachers. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 30(1), 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carless, D., & Chan, K. (2016). A good idea is not enough: Academics need assessment change literacy. In Assessment literacies in higher education: From micro to macro. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Charteris, J., & Dargusch, J. (2018). The tensions of preparing pre-service teachers to be assessment capable and profession-ready. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 46(4), 354–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charteris, J., & Smardon, D. (2022). Leadership for assessment capability: Dimensions of situated leadership practice for enhanced sociocultural assessment in schools. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 21(4), 1005–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, D., & Hollingsworth, H. (2002). Elaborating a model of teacher professional growth. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18, 947–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, A., & DeLuca, C. (2022). Mapping the constellation of assessment discourses: A scoping review study on assessment competence, literacy, capability, and identity. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 34(3), 279–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bruijn, E., Billett, S., & Onstenk, J. (2017). Enhancing teaching and learning in the Dutch vocational education system (18th ed., Vol. 18). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- De Groot, A. D., & Spiekerman, J. A. A. (2020). Methodology: Foundations of inference and research in the behavioral sciences (4th, e-book ed., Vol. 6). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca, C., & Johnson, S. (2017). Developing assessment capable teachers in this age of accountability. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice, 24(2), 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deneen, C. C., & Brown, G. T. L. (2016). The impact of conceptions of assessment on assessment literacy in a teacher education program. Cogent Education, 3, 1225380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desimone, L. M. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: Toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educational Researcher, 38(3), 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, A. T., Kreijns, K., & Van der Heijden, B. I. J. M. (2016). The design and validation of an instrument to measure teachers’ professional development at work. Studies in Continuing Education, 38(2), 162–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, C., Gilchrist, D., & Olson, L. (2004). Using the assessment cycle as a tool for collaboration. Resource Sharing & Information Networks, 17(1–2), 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, R., Cullen, R., Ringan, N., & Stubbs, M. (2015). Supporting the development of assessment literacy of staff through institutional process change. London Review of Education, 13(3), 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulmer, G. W., Lee, I. C. H., & Tan, K. H. K. (2015). Multi-level model of contextual factors and teachers’ assessment practices: An integrative review of research. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice, 22(4), 475–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grollmann, P. (2008). The quality of vocational teachers: Teacher education, institutional roles and professional reality. European Educational Research Journal, 7(4), 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulikers, J., Veugen, M., & Baartman, L. (2021). What are we really aiming for? Identifying concrete student behavior in co-regulatory formative assessment processes in the classroom. Frontiers in Education, 6, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, D. G., & Singh, A. A. (2023). Qualitative research in education and social sciences (2nd ed.). Cognella Academic Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Herppich, S., Praetorius, A. K., Förster, N., Glogger-Frey, I., Karst, K., Leutner, D., Behrmann, L., Böhmer, M., Ufer, S., Klug, J., Hetmanek, A., Ohle, A., Böhmer, I., Karing, C., Kaiser, J., & Südkamp, A. (2018). Teachers’ assessment competence: Integrating knowledge-, process-, and product-oriented approaches into a competence-oriented conceptual model. In Teaching and teacher education (Vol. 76, pp. 181–193). Elsevier Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriszan, A., & Nienaber, B. (2024). Researching playfully? Assessing the applicability of LEGO® serious Play® for researching vulnerable groups. Societies, 14(2), 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Marca, P. M. (2001). Alignment of standards and assessments as an accountability criterion. Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation, 7(21), 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Leont’ev, A. N. (1978). Activity, consciousness, and personality. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Lock, J., Kim, B., Koh, K., & Wilcox, G. (2018). Navigating the tensions of innovative assessment and pedagogy in higher education lock. The Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 9(1), n1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looney, A., Cumming, J., van Der Kleij, F., & Harris, K. (2018). Reconceptualising the role of teachers as assessors: Teacher assessment identity. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 25(5), 442–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malau-Aduli, B. S., Hays, R. B., D’Souza, K., Smith, A. M., Jones, K., Turner, R., Shires, L., Smith, J., Saad, S., Richmond, C., Celenza, A., & Sen Gupta, T. (2021). Examiners’ decision-making processes in observation-based clinical examinations. Medical Education, 55(3), 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malterud, K., Siersma, V. D., & Guassora, A. D. (2016). Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marton, F. (1981). Phenomenography—Describing conceptions of the world around us. Instructional Science, 10, 177–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McTighe, J., & Emberger, M. (2006). Teamwork on assessments creates powerful professional development. Journal of Staff Development, 27(1), 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Meijer, K., Baartman, L., Vermeulen, M., & de Bruijn, E. (2023). Teachers’ conceptions of assessment literacy. Teachers and Teaching, 29, 695–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, K., Baartman, L., Vermeulen, M., & de Bruijn, E. (2025). Mapping teachers’ perceived importance of assessment competence: A quantitative exploration in the context of Dutch Higher Vocational Education. Empirical Research in Vocational Education and Training, 17(1), 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Näsström, G., & Henriksson, W. (2008). Alignment of standards and assessment: A theoretical and empirical study of methods for alignment. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 6(3), 667–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obsuth, I., Brown, R. H., & Armstrong, R. (2022). Validation of a new scale evaluating the personal, interpersonal and contextual dimensions of growth through learning—The EPIC scale. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 74, 101154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, S., & Andrade, H. L. (2019). Teacher assessment literacy: A three-dimensional model. Teaching and Teacher Education, 84, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinholz, D. (2016). The assessment cycle: A model for learning through peer assessment. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 41(2), 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, S., & Furness, P. (2024). Lego serious play in psychology: Exploring its use in qualitative interviews. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 21(4), 578–609. Available online: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html (accessed on 1 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Schaap, H., Louws, M., Meirink, J., Oolbekkink-Marchand, H., Van Der Want, A., Zuiker, I., Zwart, R., & Meijer, P. (2019). Tensions experienced by teachers when participating in a professional learning community. Professional Development in Education, 45(5), 814–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluijsmans, D. M. A., & Struyven, K. (2014). Quality assurance in assessment: An introduction to this special issue. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 43, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiggins, R. J. (1991). Assessment literacy. Phi Delta Kappan, 72(7), 534–539. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, L., & Doumas, K. (2013). Contextual and analytic qualities of research methods exemplified in research on teaching. Qualitative Inquiry, 19(6), 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Houten, M. M. (2018). Vocational education and the binary higher education system in the Netherlands: Higher education symbiosis or vocational education dichotomy? Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 70(1), 130–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Renselaar, E., Brouwer, P., Koeslag-Kreunen, M., & de Bruijn, E. (2025). How do second career teachers in vocational education experience their induction period? An interview study. Vocations and Learning, 18(1), 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, N. L. (2002, April 1–5). Assessment literacy in a standards-based education setting [Conference session]. American Education Research Association Annual Meeting, New Orleans, LA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Wright, A. (2009). Reframing professional development through understanding authentic professional learning. Review of Educational Research, 79(2), 702–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, J., Adie, L., & Klenowski, V. (2013). Conceptualising teachers’ assessment literacies in an era of curriculum and assessment reform. Australian Educational Researcher, 40(2), 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y., & Brown, G. T. L. (2016). Teacher assessment literacy in practice: A reconceptualization. Teaching and Teacher Education, 58, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y., & He, L. (2019). How pre-service teachers’ conceptions of assessment change over practicum: Implications for teacher assessment literacy. Frontiers in Education, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).