Abstract

STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) is essential for the development of 21st-century skills, particularly in a world driven by technological innovation. However, in vulnerable school contexts, access to meaningful STEM experiences remains limited. This study addresses this issue through the design and implementation of a didactic strategy in a public high school in Bogotá, Colombia, based on two educational resources: the BioSen electronic board, which is compatible with Arduino technology and designed to acquire physiological signals such as electrocardiography (ECG), electromyography (EMG), electrooculography (EOG), and body temperature; and the Space Exploration instructional guide, which is organized around contextualized learning missions. This study employed a quasi-experimental mixed-methods design that combined pre–post perception questionnaires, unstructured classroom observations, and a contextualized knowledge test administered to three student groups. Findings demonstrate that after eight weeks of implementation with upper secondary students, the strategy had a positive impact on the development of 21st-century skills, such as creativity, computational thinking, and critical thinking. These skills were assessed through a mixed quasi-experimental design combining perception questionnaires, qualitative observations, and knowledge evaluations. Unlike the control groups, students who participated in the intervention adjusted their self-perceptions when facing real-world challenges and showed progress in the application of key competencies. Overall, the results support the effectiveness of integrating low-cost biomedical tools with gamified STEM instruction to enhance higher-order thinking skills and student engagement in vulnerable educational contexts.

1. Introduction

The Fourth Industrial Revolution has radically transformed the global economic, social, and educational landscape. Emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence, bioengineering, the Internet of Things, and automation are redefining the world of work and requiring new competencies from future generations (Rojas & Gras, 2023; Schwab, 2020). In this context, STEM education (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) has become a key strategy to prepare students for these challenges by promoting interdisciplinary, hands-on learning aimed at solving real-world problems and developing essential skills such as creativity, communication, collaboration, and computational thinking (Bybee, 2013; Honey et al., 2014; Zhaobing et al., 2018; Rodriguez et al., 2025).

Despite its global relevance, effective STEM implementation continues to face major barriers in low-resource contexts, particularly in Latin America, where limited access to educational technologies and contextually relevant pedagogies persists (Bustamante et al., 2025; Nuñez et al., 2023). Although the number of secondary school graduates has increased, interest in scientific and technological careers remains low, and classroom practices often fail to connect with students’ everyday experiences (López et al., 2025). Several initiatives have sought to address these challenges through innovative pedagogical approaches. For instance, gamification has been shown to enhance student motivation and engagement (Kalogiannakis et al., 2021), while gamified narratives strengthen STEM competencies when adapted to local realities (Seliro & Nizarudin, 2025). Likewise, project-based learning in biomedical engineering education foster engineering thinking (Anisimova et al., 2020) and strengthen collaboration, autonomy, and computational skills (Stehle & Peters-Burton, 2019).

Nevertheless, many of the STEM proposals developed in recent years have been designed for educational contexts with advanced technological infrastructure, limiting their applicability in vulnerable school settings. Within this framework, the present study proposes a differentiated approach through the use of low-cost educational resources—such as the BioSen electronic board—and a gamified instructional guide entitled Exploración Espacial (Space Exploration), both contextualized to the realities of public schools in Bogotá, Colombia. These tools seek to bridge the gap between STEM education and students’ living conditions by facilitating access to biomedical engineering content while simultaneously promoting the development of 21st-century skills. Strategies of this kind are essential to reduce educational inequalities and to foster inclusive, relevant, and equitable learning experiences aligned with the demands of contemporary society (Bautista & Hernández, 2020; Qureshi & Qureshi, 2021).

In this context, the research aims to answer the following question: What types of STEM strategies can be implemented with upper secondary students at Colegio Distrital Diana Turbay to strengthen 21st-century skills and increase academic interest in STEM disciplines?

Based on this, the study hypothesizes that the implementation of a STEM strategy grounded in hands-on experimentation with the BioSen board and the gamified learning approach will significantly contribute to the development of 21st-century skills and to the enhancement of students’ interest in scientific and technological disciplines.

To address this question, the article is structured as follows: the Methodology section describes the construction process of the BioSen electronic board, the design of the gamified instructional material Space Exploration, the study context, participants, experimental design, and data collection instruments. The Results section presents the findings related to the development of the didactic resources and the observed effects on 21st-century skills and student motivation. Subsequently, the Discussion section analyzes and interprets the results in light of previous research, limitations, and future projections. Finally, the Conclusions section summarizes the main contributions of the implemented strategy.

The theoretical foundation of this study integrates three core components that articulate the research question, methodological design, and interpretation of results: STEM education, 21st-century skills, and gamification as a learning methodology. STEM education provides a multidisciplinary framework that emphasizes hands-on inquiry, problem-solving, and the application of scientific and technological knowledge to real-world contexts. These principles align with pedagogical proposals that seek to reduce educational gaps and democratize access to meaningful technological experiences in vulnerable populations. The concept of 21st-century skills constitutes the central analytical lens of this study. Competencies such as creativity, critical thinking, computational thinking, collaboration, communication, and problem-solving serve both as targeted learning outcomes and as dimensions guiding the design of instructional missions and assessment instruments. Gamification operates as the methodological bridge connecting STEM content with the development of these competencies. By incorporating narrative elements, role-based tasks, progressive challenges, and reward systems, gamification increases engagement and promotes higher-order cognitive processing. Within this framework, the Space Exploration guide functions as a multimodal learning environment where students engage in experiential, situated, and collaborative tasks. Together, these elements create a coherent conceptual model that links the study’s purpose, its data collection methods, and the interpretation of findings, ensuring alignment between theoretical foundations and pedagogical design. Based on the literature reviewed and the pedagogical needs identified, the study is grounded in a conceptual framework that articulates STEM education, 21st-century skills, and gamification-based learning. This framework is presented below.

2. Materials and Methods

This research was conducted in three phases: (1) Design and validation of the BioSen board, (2) instructional design of the Space Exploration booklet, and (3) implementation of the board and teaching strategy.

2.1. Phase 1: Design and Validation of the BioSen Board

During this phase, the BioSen electronic board was designed and constructed. Its name derives from the words biological and sensing, alluding to its capacity to acquire physiological signals in real time. It is a low-cost, Arduino-compatible device designed for school environments with limited resources, particularly public institutions in basic and secondary education. Its development was guided by principles of accessibility, ease of use, electrical safety, and pedagogical applicability, aiming to provide students with authentic scientific and technological learning experiences.

The technical design was based on several fundamental criteria: low production cost, local availability of components, open-source platform compatibility, capability to record multiple physiological signals (electrocardiography (ECG), electromyography (EMG), electrooculography (EOG), and body temperature), ease of assembly and data acquisition, and compliance with basic user safety standards. These signals were selected for their didactic relevance, as they allow the connection of biological, electronic, and physical concepts with real-life situations that foster meaningful understanding and student engagement.

The selection of sensors and signal amplifiers aimed to balance performance, affordability, and Arduino compatibility. The circuit design was developed in Proteus version 8 Professional software (Labcenter Electronics, UK), incorporating amplification and filtering stages adapted to each type of physiological signal. Initially, a functional prototype was built on a breadboard to validate electrical performance and system stability. After confirming its proper performance, a handcrafted version was produced on a double-layer Bakelite board, followed by a final series of ten printed circuit boards (PCBs) manually assembled with definitive components.

Each BioSen board underwent functional testing using an oscilloscope and the Arduino serial interface, confirming stable and continuous signal acquisition. Additionally, a power indicator LED was included as a safety feature and visual verification of power supply prior to use, ensuring its operability within the intended educational environment.

From an economic perspective, the BioSen board represents a substantially more affordable alternative compared to other commercial physiological signal acquisition platforms used for education and research. Table 1 summarizes this cost comparison for 2025.

Table 1.

Cost comparison of the BioSen board with other technologies.

The total cost of BioSen (USD 90) plus an Arduino Uno (USD 20) achieves a reduction of over 35% compared to BITalino and nearly 80% compared to OpenBCI, while maintaining the ability to record multiple physiological variables through an open, modular, and customizable architecture. This economic advantage, combined with its educational design, makes BioSen an ideal tool for STEM teaching, rapid prototyping, and bioinstrumentation training, contributing to the democratization of scientific and technological experimentation in low-resource educational contexts.

2.2. Phase 2: Instructional Design of the Space Exploration Booklet

Twenty-first-century skills are defined as the set of competencies required for individuals to effectively face the challenges of the contemporary and future world (Fundación Omar Dengo, 2014). These include creativity (the ability to generate original ideas and solve problems innovatively), critical thinking (analyzing and evaluating information reflectively to make informed decisions), computational thinking (solving problems through logical and structured strategies derived from computer science), collaboration (working effectively in teams and integrating diverse perspectives), problem-solving (addressing challenges efficiently and practically), and communication (expressing ideas clearly and fostering mutual understanding in academic and social contexts).

To strengthen these skills, the Space Exploration instructional guide was designed to accompany the BioSen board. Its pedagogical structure was grounded in gamification principles, understood as the integration of video game elements into educational settings to enhance motivation, engagement, and meaningful learning (Deterding, 2012). The guide incorporated an immersive narrative centered on space exploration missions, in which students assumed collaborative roles (programmer, mechanic, or administrator). A progressive badge system (bronze, silver, and gold) was implemented to recognize performance and encourage self-regulation and reflective learning. In this way, students were able to self-assess their progress and recognize the development of competencies such as creativity, critical thinking, collaboration, problem-solving, communication, and computational thinking.

The instructional design of the guide was grounded in the review and analysis of well-recognized STEM materials, such as Brazo Robótico: Ingenieros por un Día (Parque de las Ciencias, 2020), Búsqueda Galáctica (Clemson University, 2021), Realidad Virtual y STEM (Silva et al., 2019), and Ideas de Proyectos STEM para Inspirar Jóvenes (Elhuyar STEM, 2020). These resources provided pedagogical frameworks that guided the integration of active learning, collaboration, and problem-solving strategies adapted to the local context. The final product integrated a coherent narrative, progressive activities, and formative assessment mechanisms articulating gamification with the exploration of biomedical engineering and computational thinking principles.

Space exploration was selected as the central theme due to its educational appeal and integrative potential. The narrative linked scientific, technological, and physiological concepts while fostering curiosity and teamwork. By taking on the role of space cadets in biomedical missions, students engaged in creative problem-solving and critical reflection, connecting classroom learning with real-world challenges.

The booklet included four thematic units, each focused on a specific physiological signal: ECG, EMG, EOG, and body temperature. Each unit includes two types of missions: introductory missions, aimed at conceptual understanding without using the BioSen board, and applied missions, focused on the acquisition and analysis of real data through the board as a technological tool.

Each mission was designed with clear learning objectives, defined roles, required materials, estimated duration, precise instructions, and closing questions intended to foster analytical reflection. A gamified feedback system using badges was incorporated to provide tangible and motivating recognition of student performance. Additionally, the booklet followed a progressive and coherent structure that connects scientific content with experiential learning, maintaining a balance between conceptual rigor and pedagogical creativity.

Overall, the design of Space Exploration was explicitly oriented toward the strengthening of 21st-century skills, integrating dimensions such as creativity, critical thinking, computational thinking, collaboration, problem-solving, and communication. These competencies were promoted transversally throughout the missions and incorporated into the assessment instruments, ensuring a formative approach aligned with the contemporary demands of STEM education.

2.3. Phase 3: Implementation of the Board and Teaching Strategy

The teaching–learning strategy was implemented over eight weeks (10 May–28 June 2023) at Colegio Distrital Diana Turbay, a public high school in Bogotá, Colombia. The study was approved by the school administration on 17 April 2023, and all participants were informed about its voluntary nature. The research involved no risk and collected no personal or sensitive data.

A total of 93 eleventh-grade students participated (50 males, 43 females; mean age 16). Through group randomization, Group 1101 (32 students) was assigned as the experimental group, while Groups 1102 and 1103 (31 and 30 students) served as controls. The implementation was led by the Technology and Informatics teacher, who designed both the BioSen board and the Space Exploration guide.

The institution is located on the outskirts of Bogotá, in the Rafael Uribe Uribe district, an area characterized by socioeconomic vulnerability. Most families belong to strata 1 and 2, categories in Colombia that identify low-income households eligible for public subsidies. In this context, many students come from single-parent families, with household incomes generally below the minimum monthly wage (COP $1,160,000, equivalent to USD $252 in 2023). Informal employment is common among parents or guardians, and a significant proportion of students live in rented homes or informal settlements with limited access to basic services. Additionally, issues related to security and the presence of local gangs contribute to social vulnerability and restricted access to technology outside the school environment.

In response to this reality, Colegio Distrital Diana Turbay has implemented initiatives to strengthen its Technology and Informatics curriculum, traditionally focused on basic digital literacy. In recent years, the institution has expanded its curriculum by incorporating content related to programming, robotics, and electronics, using tools such as Arduino boards, electronic components, and simulation software. These initiatives have enabled students to develop essential competencies, including understanding and editing basic Arduino instructions, managing sequential and conditional structures, identifying electrical symbols, and interpreting simple schematic circuits. This educational environment provided the appropriate conditions for implementing a technology-based STEM strategy.

The strategy was applied exclusively to Group 1101, using the BioSen board and Space Exploration guide under a STEM framework. Activities were structured as biomedical exploration missions, focusing on acquiring and analyzing real physiological signals (ECG, EMG, EOG). Control groups covered similar topics (body signals, sensors, digital and analog data) through traditional instruction.

Meanwhile, the control groups (1102 and 1103) covered the same general content—human body signals, natural and artificial sensors, and concepts of digital and analog data—but through traditional theoretical classes and practical activities using generic sensors (ultrasonic and infrared).

To evaluate the intervention, a Likert-scale questionnaire was administered at the beginning (first week of May) and at the end (last week of June) of the process. The instrument was reviewed and validated by an expert holding a master’s degree in educational quality assessment and assurance. It consisted of 18 items distributed across six dimensions corresponding to 21st-century skills: creativity, critical thinking, computational thinking, collaboration, problem-solving, and communication. Each skill was accompanied by a brief description and three statements rated on a four-point scale, where 1 = “strongly disagree” and 4 = “strongly agree.” Additionally, five extra items were included to measure interest in STEM areas, using a scale from 1 (“not interested”) to 5 (“very interested”). For analysis purposes, four performance levels were established based on the sum of responses, reflecting the degree of perceived development in each skill. The instrument’s structure and scoring categories were later adapted to enable statistical comparisons by merging low-frequency levels, ensuring compliance with Chi-square test assumptions.

During implementation, unstructured classroom observations were conducted to document behavior, participation, and skill development. To organize this information, a systematic field record format was created, including group identification data, session objectives, relevant observations, a qualitative assessment of the promoted skills, reflective notes, and a section for photographic evidence of the process. This procedure followed a systematic qualitative coding process aligned with the analytical categories defined in the conceptual framework.

The observations were carried out during the eight intervention sessions, following a descriptive-interpretative approach that allowed for continuous and contextualized documentation of the teaching–learning process. Data collection focused on six analytical categories corresponding to the 21st-century skills: creativity, critical thinking, computational thinking, collaboration, problem-solving, and communication. During each session, detailed notes were taken on the strategies employed by students to solve challenges, peer interaction, role distribution, and the degree of autonomy demonstrated during task execution.

Subsequently, the records were reviewed and organized according to the recurrence and relevance of behaviors observed in relation to the targeted skills, which allowed for the construction of a systematic and coherent description of the pedagogical experience.

Finally, at the end of the intervention, a knowledge assessment was administered to the three participating groups to complement the data obtained through the pre- and post-intervention tests and the unstructured observations conducted during the sessions. This evaluation sought to provide an additional perspective on the conceptual and procedural learning achieved and to contrast students’ self-perceptions with their actual understanding of the covered content.

The instrument was designed and administered directly by the researcher-teacher and was structured around a contextualized problem situation common to all three groups, inspired by real scenarios related to the use of sensors and the interpretation of physiological signals. Based on this context, five multiple-choice questions (with a single correct answer) were formulated to assess students’ ability to: recognize the characteristics and types of physiological signals; identify electronic materials and components used during the practice; analyze and interpret electrical signal graphs obtained through the BioSen board; and apply bioengineering and computational thinking concepts in real or simulated contexts.

Each question integrated conceptual and practical elements, aiming to evaluate students’ ability to transfer knowledge to new situations. The assessment was administered individually, lasted approximately 20 min per group, and was completed without teacher assistance to ensure participants’ autonomy. Scores from this assessment were analyzed descriptively to compare conceptual mastery among the three groups and to triangulate the findings obtained from perception and observational data.

2.4. Data Analysis Procedures

The data analysis in this study followed a mixed-methods approach aligned with the research objectives and the conceptual framework described above.

Quantitative data from the pre- and post-intervention Likert-scale questionnaire were analyzed using the Chi-square (χ2) test to determine significant differences between performance levels across the experimental and control groups. Given the low frequency of responses in Levels I and II, these categories were merged into a single “Low performance” category to meet the assumptions of the statistical test, following standard practices in educational measurement.

Qualitative data from unstructured classroom observations were examined through a descriptive–interpretative process. Observational records were coded around six analytical categories corresponding to the 21st-century skills targeted by the intervention. Recurring patterns were identified and organized to provide a comprehensive account of student behaviors, collaborative dynamics, and evidence of skill development throughout the sessions.

The knowledge test results were analyzed descriptively to compare conceptual understanding across the three groups. This triangulation of quantitative and qualitative data ensured consistency and methodological alignment with the study’s purpose of evaluating the impact of the teaching strategy on both perceived and observed development of 21st-century skills.

3. Results

Contemporary education demands dynamic pedagogical responses that adapt to ongoing social, technological, and scientific changes. Within this context, the development of instructional and technological resources offers a strategic pathway for designing relevant and innovative educational proposals (Pliushch & Sorokun, 2022). This study generated three primary outcomes aligned with methodological phases: (1) the BioSen electronic board for physiological signal acquisition, (2) the Space Exploration gamified instructional booklet as a complementary learning resource, and (3) evidence from classroom implementation assessing impacts on 21st-century skills and meaningful appropriation of biomedical engineering content.

3.1. Phase 1 Results: Design and Construction of the Electronic Board

The BioSen electronic board was developed as a double-layer printed circuit board (PCB) measuring 110 mm × 95 mm, designed for acquiring physiological signals such as electrocardiography (ECG), electromyography (EMG), electrooculography (EOG), and body temperature. Its design meets criteria of low cost, Arduino compatibility, and applicability in educational environments.

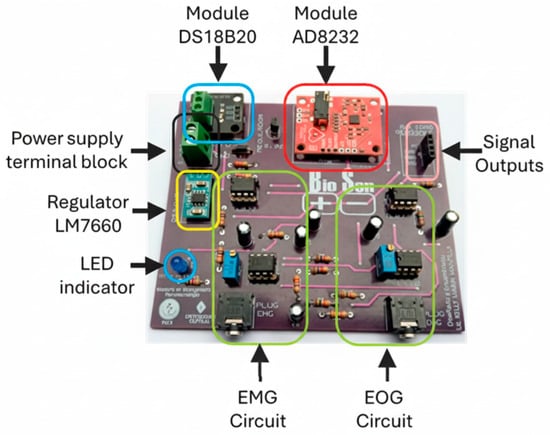

As shown in Figure 1, the board architecture comprises functional modules distributed across the PCB. At the upper center, an AD8232 module acquires, amplifies, and filters ECG. At the upper left, a DS18B20 digital sensor measures body temperature. Adjacent to this sensor, a terminal block connects a 9 V supply for the full system. Below the terminal, an LM7660 charge-pump regulator generates the negative rail required by the operational amplifiers in the EMG and EOG stages. A blue LED provides a visual power indicator confirming proper energization.

Figure 1.

BioSen Board. Double-layer electronic board (110 mm × 95 mm), compatible with Arduino, designed for the acquisition of physiological signals (temperature, ECG, EMG, and EOG) through integrated modules such as the AD8232 and circuits based on the AD620 and TL072. It includes an LM7660 voltage regulator, power terminal block, status LED, and connection header for educational integration.

The EMG (central section) and EOG (lower section) modules employ AD620 instrumentation amplifiers to capture low-amplitude biopotentials. Signals are conditioned by TL072-based active filters tuned to each modality: a 160–480 Hz band-pass for EMG and a 1 Hz low-pass for EOG to reduce interference from respiration or cardiac activity, thus improving eye-movement detection. Conditioned outputs are routed to a four-pin female header (upper right) for straightforward connection to Arduino analog inputs; reliable acquisition requires a shared ground (GND) between boards. The circuit design followed an iterative development approach consistent with biomedical engineering pedagogy (Moscoso-Barrera & Wang, 2024).

Ten fully functional units were assembled and tested on an oscilloscope to verify signal integrity across modules. Arduino compatibility was confirmed via accurate serial transmission. Technical documentation is provided in Supplementary Material S1.

3.2. Phase 2 Results: Design of Instructional Material

The Space Exploration booklet was developed as a gamified companion to the BioSen board to promote active STEM learning and foster 21st-century skills in upper-secondary students. The booklet comprises four thematic units, each focused on the study and analysis of a specific physiological signal: body temperature, ECG, EMG, and EOG. Each unit contains two complementary missions corresponding to different stages of learning: an introductory mission and an application mission. The introductory mission does not require the use of electronic devices and is aimed at developing a conceptual understanding of the physiological phenomenon. In this phase, students work with basic materials, conduct qualitative observations, reflect on everyday experiences related to the signal, and formulate hypotheses, for instance, determining training zones by collecting and analyzing heart rate data, which helps activate prior knowledge and establish accessible conceptual frameworks. In contrast, the application mission introduces the use of the BioSen board for acquiring and analyzing real data, requiring the interpretation of biomedical signals, sensor measurements, and the resolution of practical challenges in simulated contexts. This progressive structure facilitates a transition from conceptual learning to experimental practice, enabling the gradual assimilation of content, the development of technical skills, and the consolidation of cognitive competencies related to data analysis, decision-making, and problem-solving (Ubaidillah et al., 2023).

As illustrated in Figure 2A, each unit opens with a narrative context linked to space exploration, explicit learning objectives, targeted STEM skills, and a glossary of key terms. This structure allows students to situate themselves thematically, understand the purpose of the activities, and become familiar with the technical vocabulary before engaging in the mission.

Figure 2.

Didactic Components of the Space Exploration Booklet. (A) illustrates the basic structure of each unit. The blue highlighted box on the left shows the narrative context of the guide. On the right, also highlighted in blue, are the learning objectives, the specific skills, and the key vocabulary for this mission in the guide. (B) Booklet on the left shows, in yellow, the mission that the student must complete. The mission objective, student roles, and required resources are emphasized with red-outlined boxes. On the right, the skills to be developed in the mission are presented along with their evaluation criteria, and the step-by-step instructions that each student group must follow to complete the mission are highlighted in red. (C) Booklet includes instructions supplemented with images, highlighted in the green box on the left. Students are also offered additional materials accessible through QR codes (as shown in the green-highlighted circle in the image on the right), as well as interesting information at the end of the mission under the section “Did You Know?”, which is indicated by the green box in the image on the right. These elements enrich the overall learning experience.

The narrative framework of the booklet is based on a space exploration context in which students take on the role of scientific cadets tasked with completing biomedical missions across the universe. This storyline aims to increase motivation, foster collaboration, and connect learning with real-world challenges.

As shown in Figure 2B, each mission is structured into functional components including the specific objective of the activity, a list of required materials, the assignment of roles among participants, step-by-step instructions, and assessment rubrics that classify performance levels as bronze, silver, or gold. Roles such as programmers, field mechanics, signal observer, or mission leader are designed to simulate real-world functions within a scientific exploration setting, encouraging individual responsibility and group interdependence. This role distribution not only strengthens teamwork but also allows students to explore and enhance specific skill sets associated with their role, such as computational logic, spatial reasoning, decision-making, or technical communication. The tiered rubric offers differentiated feedback according to the level of achievement: bronze indicates basic performance, silver represents functional competence, and gold denotes excellence in mission execution. This system encourages continuous improvement, facilitates self-assessment, and allows teachers to monitor student progress more objectively and pedagogically.

Additionally, the booklet includes gamified elements such as badges, thematic visuals, and technical appendices. As seen in Figure 2C, QR codes link to digital resources, explanatory videos, and complementary scientific content. This multimedia integration enriches the educational experience and reinforces learning through multiple channels.

The instructional design of the booklet is explicitly oriented toward strengthening six 21st-century skills: creativity, critical thinking, computational thinking, collaboration, problem-solving, and communication. These competencies are embedded transversally across the missions through activities that require generating innovative solutions, critically analyzing situations, programming systems, coordinating team efforts, overcoming technical challenges, and clearly expressing ideas and results. For example, creativity is stimulated when redesigning prototypes; computational thinking is activated while debugging code; collaboration emerges in role distribution; and communication is practiced in the presentation of findings. To assess the development of these skills, a Likert-scale perception questionnaire with items associated with each competency was administered before and after the implementation. Furthermore, these skills were monitored qualitatively through unstructured observations during the sessions, enabling the collection of relevant data and a comprehensive evaluation of the strategy’s impact on key competencies.

As a complement to the acquisition and analysis of physiological signals, some booklet units included the assembly of simple mechanical designs, such as an articulated gripper or an electromechanical crane. These activities enabled students to integrate knowledge of electronics, programming, and mechanics in the development of functional prototypes, thereby reinforcing their understanding of applied biomedical engineering principles. Working with physical devices also enhanced 21st-century skills by stimulating creativity in design, collaboration during assembly, problem-solving in response to technical issues, and computational thinking while programming specific functions. These practical experiences underscore the value of project-based STEM education, as they allow students to confront real engineering challenges, bridge theory and practice, and develop transferable skills for future academic and professional settings.

Altogether, the Space Exploration booklet (Supplementary Material S2 shows missions 5 and 6) represents an innovative and contextualized instructional proposal that integrates biomedical engineering content with active, gamified methodologies, adapted to students’ educational level and the realities of public secondary schools.

3.3. Phase 3 Results: Implementation of the Didactic Strategy

The third phase of the research focused on the implementation and evaluation of the didactic strategy that integrated the BioSen electronic board and the gamified guide Space Exploration. For this purpose, three data collection instruments were applied: a Likert-type perception questionnaire administered before and after the intervention (pre- and post-test), a record of unstructured observations conducted throughout the eight work sessions, and a knowledge test designed to identify the level of conceptual appropriation achieved.

The evaluation process made it possible to gather information on the development of six 21st-century skills—creativity, critical thinking, computational thinking, collaboration, problem-solving, and communication—as well as on students’ interest in STEM areas and their understanding of basic biomedical engineering concepts.

3.4. Results of the Pre- and Post-Test

The questionnaire included contextualized scenarios for each skill, accompanied by three statements designed to estimate students’ self-perception on a four-level scale (I = low performance; IV = high performance). To ensure the statistical validity of the analysis, and because the frequencies for Levels I and II were very low (in some cases, even zero), both levels were merged into a single category (“Low performance”). This adjustment allowed the analysis to meet the assumptions of the chi-square test, which requires that most expected frequencies be equal to or greater than 5. From an educational standpoint, Levels I and II represent similar degrees of initial or basic skill development. In many level-based assessment instruments, the first two levels correspond to Level I (incipient performance or no evidence of the skill) and Level II (limited or emerging performance). The difference between these two levels is usually smaller compared to the gap between them and Levels III or IV. Therefore, merging them into a single “Low” category (I–II) is pedagogically coherent, as both reflect students who have not yet achieved a functional mastery of the skill.

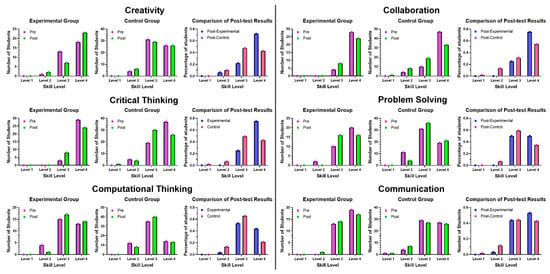

Figure 3 and Table 2 present the distribution of results for the six evaluated skills, comparing pre- and post-intervention performance in the experimental group (1101) and the control groups (1102 and 1103). Likewise, the percentage of students at each performance level after implementation was analyzed to contrast the trends between both groups.

Figure 3.

Percentage of students by performance level in six 21st-century skills, before and after the intervention, in groups 1101 (experimental), 1102 and 1103 (control).

Table 2.

Results of the Chi-square (χ2) test comparing pre- and post-test performance for the experimental and control groups, and post-test differences between both groups for each 21st-century skill.

The results revealed distinct patterns depending on the type of skill. For complex cognitive skills—creativity, critical thinking, and computational thinking—the most noticeable progress was observed in the experimental group.

In creativity, the proportion of students at the high level increased from 56% to 72%, showing a statistically significant difference compared to the control group (χ2 = 7.29, p = 0.026). In critical thinking, the increase in higher levels was also significant (χ2 = 8.61, p = 0.013), indicating a direct effect of the didactic strategy on students’ reflective and analytical reasoning. Similarly, in computational thinking, a moderate but significant improvement was observed in the experimental group (χ2 = 6.34, p = 0.042), reflecting progress in understanding and applying logical and coding principles during the missions.

In contrast, the skills of collaboration, problem-solving, and communication did not show statistically significant differences, although some qualitative changes were evident. In collaboration, the experimental group maintained a high proportion of students at the upper level, while the control group showed a slight but significant internal improvement (χ2 = 7.17, p = 0.028), possibly linked to sustained teamwork throughout the semester. In problem-solving, both cohorts maintained stable distributions (χ2 = 2.65, p = 0.266), while in communication, although no quantitative differences were recorded (χ2 = 2.67, p = 0.264), improvements were noted in argumentative clarity and expressive resource use during group missions.

Overall, the results suggest that the intervention had a more visible impact on higher-order skills, particularly critical thinking, creativity, and computational thinking, where the largest increases were recorded at the upper performance levels.

Social and communication skills remained relatively stable, which could be explained by the short duration of the implementation or by the gradual nature of interpersonal skill development, which typically requires longer processes to produce sustainable transformations.

Finally, the redistribution of performance levels within the experimental group indicates an adjustment in students’ self-perception of their own competencies. For cognitive skills, the trend toward intermediate and higher levels suggests a more realistic self-reflection following the practical experience, while in collaboration and problem-solving, the slight reduction at the highest levels coincided with the increased complexity of collective tasks, which demanded greater coordination, leadership, and negotiation. The control groups, in contrast, maintained stable profiles between the initial and final measurements, with no significant changes attributable to the type of activities performed.

3.5. Results from Unstructured Observations

During the eight implementation sessions with the pilot group, unstructured observations made it possible to identify clear evidence of the progressive strengthening of 21st-century skills, despite the decrease observed in students’ self-perception levels reported in the post-intervention evaluation.

Collaboration improved in role organization, task distribution, and coordination. Although some groups initially struggled to assume and maintain assigned roles, as the missions progressed, an increase in autonomy and team cohesion became evident—particularly during the construction of prototypes such as the temperature-sensing glove, the robotic hand, and the mechanical gripper.

Communication (verbal and nonverbal) advanced notably. Activities involving sensory restrictions, such as Missions 1 and 7, promoted the creation of gestural and visual strategies to transmit information effectively. In Mission 7, students used eye movements, gestures, and blinking patterns to exchange instructions, which strengthened communication accuracy, empathy, and active listening within the teams.

Creativity was reflected in students’ ability to generate alternative solutions to technical setbacks. A representative example was the replacement of silicone with needle-and-thread stitching during the glove assembly process, demonstrating flexibility, ingenuity, and practical sense in response to the limitations of available materials.

Problem-solving was constant throughout the sessions. Students faced and overcame difficulties related to prototype assembly, sensor programming, and circuit configuration. These situations encouraged collaborative decision-making and active problem-seeking, showing sustained progress in strategic thinking and technical autonomy.

Critical thinking was evident in activities focused on the analysis and interpretation of physiological signals. In Mission 1, for example, when comparing perceived thermal sensations with the actual water temperatures, students created tables and graphs that led them to identify factors such as sensory adaptation and thermal contrast. These experiences encouraged the formulation of evidence-based conclusions and the use of empirical reasoning to support their observations.

Computational thinking showed progressive improvement throughout the process. In the final sessions, students demonstrated greater understanding of the code structure and made modifications to personalize their projects, integrating new functions and adaptations based on their own ideas.

Regarding the control groups, a similar participatory process was observed, although with notable differences compared to the pilot group. The absence of defined roles and structured collaborative instructions occasionally led to dispersion in task assignments and difficulties in decision-making, which slowed the development of certain activities requiring simultaneous coordination.

Furthermore, due to the lack of a contextual narrative and missions connected to real-world situations, learning focused mainly on the exposition of biological concepts, sensor functionality, and code structure. Although these contents were understood, it was more difficult for students to establish autonomous connections with potential practical applications. Consequently, proposals for code or prototype adaptation and modification were less frequent and less elaborate compared to those observed in the experimental group.

Nevertheless, the control group students demonstrated interest, willingness to participate, and appropriated the fundamental concepts addressed, successfully completing the proposed activities. However, their level of knowledge transfer to new or creative contexts was lower compared to the pilot group, reflecting a more linear and less exploratory learning process.

3.6. Knowledge Assessment Results

To determine the level of conceptual appropriation achieved, a knowledge test was administered to the three participating groups. The instrument included a common contextual scenario and five multiple-choice questions designed to evaluate the identification of physiological signals, the analysis of data graphs, the characterization of materials and electronic components, and the application of physiological signals in practical contexts.

As shown in Figure 4, the pilot group (1101) achieved a higher performance, with 61.3% correct answers, compared to 53.6% and 43.2% obtained by the control groups (1102 and 1103, respectively).

Figure 4.

Percentage of correct and incorrect answers in the contextual evaluation applied to the three groups (1101 experimental, 1102 and 1103 control).

The results indicate that the implemented pedagogical intervention had a positive effect on stimulating creativity and critical thinking, confirming the relevance of the teaching strategies presented in this study and their application of concepts to real-world situations. The use of gamification-based methodologies, teamwork, and technological tools promoted deeper learning, enabling students to integrate technical knowledge with divergent thinking.

Furthermore, the upward trend in computational thinking suggests that the activities successfully linked algorithmic logic with creative and decision-making processes, thereby strengthening students’ analytical and innovative abilities in the projects developed within the Space Exploration booklet.

4. Discussion

The comparative analysis between the pre- and post-intervention questionnaire results, the unstructured observations, and the knowledge assessment revealed significant discrepancies that required a deeper reflection on the factors that may have influenced the outcomes.

First, the results of the pre- and post-implementation questionnaire—designed to measure students’ self-perception regarding their 21st-century skills—showed an overall decrease in the final scores, particularly in the experimental group. This finding appears paradoxical, as it contrasts with the improvements observed during the sessions. A possible explanation lies in the Dunning–Kruger effect (Dunning, 2011), which suggests that in the absence of practical experience, individuals tend to overestimate their abilities, but when faced with real situations, they adjust their self-perception in a more critical and realistic manner. In this context, students in the experimental group, when interacting with authentic challenges—such as the design of biomedical prototypes and the interpretation of physiological signals—developed a more accurate awareness of their limitations, resulting in a more cautious self-assessment. Therefore, the decrease in self-perception does not necessarily indicate a loss of skill but rather a metacognitive recalibration derived from experiential learning.

Second, the unstructured observations provided qualitative evidence that both complemented and, in some cases, contrasted with the quantitative data. Throughout the eight sessions, the teacher observed notable progress in collaboration, communication, creativity, and problem-solving. Students in the experimental group demonstrated greater autonomy in role organization, decision-making, and coordination during mission execution, whereas the control groups tended to show more dispersed dynamics and less integration of knowledge. These observations suggest that the “Space Exploration” strategy and the BioSen board effectively fostered teamwork and the practical application of technical concepts, even though these advances were not proportionally reflected in the self-perception measurements.

Meanwhile, the knowledge assessment, administered at the end of the intervention, provided a more objective perspective of the conceptual and procedural learning achieved. The results showed that the experimental group outperformed the control groups, demonstrating a stronger understanding of physiological signal principles, appropriate material selection, and the interpretation of biomedical graphs. Since this test was designed and applied by the same teacher-researcher for all groups under a shared problem-based context, the findings confirm that the pedagogical strategy had a positive and differential impact on the experimental group, promoting deeper learning and the application of knowledge to real-world situations.

Taken together, the integration of these three components suggests that the experimental group not only acquired greater technical knowledge but also developed cognitive and social skills in a more conscious and critical manner. Although the quantitative self-perception measures showed a decline, the qualitative and performance-based evidence indicates effective progress in 21st-century competencies. In contrast, the control groups maintained stable levels in both self-perception and observable performance, confirming that the implementation of the gamified guide and the BioSen board led to a specific improvement attributable to the pedagogical intervention.

Our findings are consistent with a growing body of evidence demonstrating that gamified learning environments can effectively promote the development of soft skills such as creativity, critical thinking, and computational thinking. For instance, McGowan et al. (2023) reported that a serious game designed for higher education significantly enhanced creative thinking, teamwork, and communication. Similarly, Carcelén-Fraile (2025) found that active gamification improved self-confidence and social abilities among primary school students, while Denoni-Buján (2025) observed that classroom escape room activities strengthened problem-solving, communication, and critical thinking. Buenadicha-Mateos (2025) showed that gamification increased motivation, academic performance, and collaborative skills, and Christopoulos & Mystakidis (2023) highlighted that well-designed gamified environments fostered autonomy, competence, and social connectedness. In addition, Jaramillo-Mediavilla et al. (2024) found in a systematic review that one-third of the analyzed studies reported improvements in academic performance and more than half in motivation and social competencies. McKevitt et al. (2025) demonstrated that gamification in mathematics education enhanced students’ resilience and intrapersonal skills, while Bartolomé (2025) emphasized that video game–based environments improved interpersonal and organizational abilities, though assessment frameworks remain underdeveloped. In line with these studies, our results show that although students’ self-perceptions declined—likely due to metacognitive recalibration—the observational and performance-based data evidenced clear improvements in higher-order skills, particularly critical thinking and creativity. This reinforces the notion that the most substantial effects of gamified learning on soft-skill development tend to emerge in behavioral and performance indicators rather than in self-reported perceptions.

Moreover, this experience allowed the identification of methodological effects that may have influenced the results. The Hawthorne effect (Best & Neuhauser, 2006) may have affected the experimental group, as students were aware that they were participating in a differentiated activity, which could have influenced their motivation and engagement. Additionally, the observer bias is acknowledged, as one of the researchers served simultaneously as teacher and evaluator, potentially affecting the interpretation of some behaviors, albeit unintentionally.

Beyond these factors, the findings substantiate the pedagogical value of integrating locally developed technologies with active, gamified learning. The combination of the BioSen board and the Space Exploration guide successfully linked science with students’ realities, fostering meaningful, contextualized, and emotionally engaging learning. By incorporating space and biomedical narratives, this proposal facilitated the appropriation of complex STEM concepts, while promoting participation, self-regulation, and collaboration.

Finally, although socio-emotional skills did not show statistically significant changes, the qualitative improvements observed in teamwork, autonomy, and collaborative problem-solving suggest that the strategy represents a promising pedagogical model. Future research could strengthen these results through longer interventions, the inclusion of complementary assessment tools, and teacher training in programming and Arduino platform use, thereby ensuring greater consistency and sustainability in replicating this educational model.

4.1. Limitations

This study presents several methodological limitations that should be considered when interpreting its findings and when designing future replications. First, the intervention spanned only eight weeks, which may be insufficient to observe deeper or long-term transformations in socio-emotional and collaborative competencies. Longer implementations could provide more stable insights into the sustained development of 21st-century skills. Second, as acknowledged in the Discussion section, one of the researchers acted simultaneously as teacher and evaluator. Although this was managed through systematic observation protocols, future studies should incorporate independent observers or external coders to minimize potential bias. Third, the use of self-perception instruments—while valuable for capturing students’ metacognitive reflections—remains sensitive to recalibration effects that may arise during experiential learning, as previously discussed. Complementary performance-based assessments could help strengthen the accuracy of skill measurement. Fourth, the study was conducted in a single public school in Bogotá, within a context of socioeconomic vulnerability. Although this strengthens ecological validity, it also limits the generalizability of the findings. Replications across diverse schools and regions would help determine the adaptability of the proposed strategy. Finally, although the BioSen board and Space Exploration guide were designed for low-resource environments, their successful implementation still required minimal technological infrastructure and teacher familiarity with Arduino-based tools. Future applications may benefit from targeted teacher training programs to ensure consistent adoption of the methodology across different educational settings.

4.2. Implications and Future Research Directions

The findings of this study offer meaningful implications for STEM education in socioeconomically vulnerable contexts and open several avenues for future research. From an educational perspective, the integration of the BioSen electronic board and the Space Exploration booklet demonstrates that low-cost biomedical technologies can be successfully implemented in secondary classrooms, providing authentic scientific experiences in settings where technological access is limited. This highlights the potential of similar locally developed tools to democratize STEM learning and enhance student engagement.

The combination of gamification and hands-on experimentation proved effective in promoting higher-order skills such as creativity, computational thinking, and critical thinking. Teachers and curriculum designers may adopt mission-based, role-driven instructional formats to foster collaboration, communication, and problem-solving, even with minimal infrastructure. Additionally, the successful implementation of the strategy underscores the importance of adequate teacher preparation. Training programs focused on Arduino-based platforms, biomedical technologies, and gamified pedagogical design may enhance the reliability and scalability of similar instructional initiatives.

Future research should explore the long-term impact of these strategies through extended interventions and multi-site implementations across diverse school environments. Such studies would strengthen the evidence for generalizability and shed light on contextual factors that influence the effectiveness of STEM initiatives grounded in gamification and biomedical experimentation. Further studies may also incorporate mixed assessment models—including performance-based rubrics, behavioral indicators, and automatic analytics—to complement self-perception measures and deepen the evaluation of cognitive and technical competencies.

Finally, future work could investigate the integration of artificial intelligence tools for personalized feedback and adaptive learning, as well as the potential influence of early biomedical engineering exposure on students’ long-term interest in STEM careers.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that integrating low-cost biomedical technologies with a gamified instructional approach can transform traditional learning environments, offering students authentic scientific experiences that promote deeper engagement with STEM content. The development and implementation of the BioSen electronic board and the Space Exploration booklet enabled students to explore physiological signals while strengthening analytical, creative, and computational skills.

The outcomes of this intervention are consistent with widely reported patterns in the STEM education literature, which highlights that hands-on experimentation and contextualized missions tend to reinforce higher-order cognitive abilities and increase student motivation. Likewise, the positive gains observed in creativity, computational thinking, and critical thinking confirm that immersive, challenge-based strategies are effective in developing these competencies, particularly when they integrate real-world technological tools adapted to the school context. At the same time, the results nuance some assumptions commonly found in previous reports, especially regarding the development of socio-emotional skills such as collaboration and communication. While students demonstrated progress during classroom activities, these skills showed limited measurable change in self-perception instruments, suggesting that they may require longer or more sustained interventions to manifest significant shifts.

Beyond these findings, the didactic strategy proposed in this study offers a replicable and scalable model for schools seeking to reduce educational inequities and bring relevant technological experiences into the classroom. The approach connects science with everyday life, promotes autonomy and problem-solving, and supports the formation of students who are more critical, reflective, and capable of tackling contemporary challenges with creativity and confidence. Overall, this work confirms the potential of integrating low-cost engineering tools and gamified methodologies to enrich STEM learning in vulnerable contexts, while also pointing toward avenues for improvement and expansion in future implementations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/educsci15121624/s1: Supplementary Material S1: Technical information for the BioSen board and Supplementary Material S2: Space Exploration booklet.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.J.M.-M. and W.D.M.-B.; Methodology, K.J.M.-M. and W.D.M.-B.; Software, K.J.M.-M.; Validation, K.J.M.-M.; Formal Analysis, K.J.M.-M. and W.D.M.-B.; Investigation, K.J.M.-M.; Resources, K.J.M.-M.; Data Curation, K.J.M.-M. and W.D.M.-B.; Writing–Original Draft Preparation, K.J.M.-M. and W.D.M.-B.; Writing–Review & Editing, K.J.M.-M. and W.D.M.-B.; Visualization, K.J.M.-M. and W.D.M.-B.; Supervision, W.D.M.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not require approval from an ethics committee, as it involved an educational intervention approved by the educational institution Diana Turbay IED School, located in Bogotá (Colombia).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was waived for participants, as this educational intervention was conducted within the scope of class activities with the approval of the educational institution Diana Turbay IED School.

Data Availability Statement

Access to the Space Exploration booklet containing the complete missions is available upon request by email to the authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Diana Turbay IED School, located in Bogotá (Colombia), for their support in the execution of this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| STEM | Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics |

| ECG | Electrocardiography |

| EOG | Electrooculography |

| EMG | Electromyography |

| PCB | Printed Circuit Board |

References

- Anisimova, T., Sabirova, F., & Shatunova, O. (2020). Formation of design and research competencies in future teachers in the framework of STEAM education. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET), 15(2), 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolomé, J. (2025). Game on: Exploring the potential for soft-skill enhancement through video games. Information, 16(10), 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, J., & Hernández, R. (2020). Aprendizaje basado en el modelo STEM y la clave de la metacognición. Innoeduca. International Journal of Technology and Educational Innovation, 6(1), 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, M., & Neuhauser, D. (2006). Walter a shewhart, 1924, and the hawthorne factory. Quality & Safety in Health Care, 15(2), 142–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buenadicha-Mateos, M. (2025). From engagement to achievement: How gamification transforms skills and outcomes in education. Education Sciences, 15(8), 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, M. S. G., Triviño, E. E. A., Barre, C. R. C., Franco, E. L., & Bohórquez, R. W. M. (2025). Analysis of access to STEM education in rural areas of Latin America: Implications for sustainable social and economic development. LATAM Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades, 6(1), 2012–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, R. W. (2013). The case for STEM education: Challenges and opportunities. National Science Teachers Association. [Google Scholar]

- Carcelén-Fraile, M. (2025). Active gamification in the emotional well-being and social skills of primary education students. Education Sciences, 15(2), 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopoulos, A., & Mystakidis, S. (2023). Gamification in education. Encyclopedia, 3, 1223–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemson University, 4-H youth development program. (2021). Busqueda galacica. 4-H org. 4-H.org/STEMChallenge. [Google Scholar]

- Denoni-Buján, M. (2025). Challenges of innovation through gamification in the classroom: A study on soft-skill development. Education Sciences, 15(10), 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deterding, S. (2012). Gamification: Designing for motivation. ResearchGate, 19, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, D. (2011). The dunning–Kruger effect: On being ignorant of one’s own ignorance. In J. M. Olson, & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 44, pp. 247–296). Academic Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhuyar STEM. (2020). Ideas de proyectos STEM para inspirar a jovenes. Elhuyar. [Google Scholar]

- Fundación Omar Dengo. (2014). Competencias para el siglo XXI: Guía práctica para promover su aprendizaje y evaluación. Fundación Omar Dengo. [Google Scholar]

- Honey, M., Pearson, G., & Schweingruber. (2014). «STEM integration in K-12 education: Status, prospects, and an agenda for research». NAP.edu. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo-Mediavilla, L., Basantes-Andrade, A., Cabezas-González, M., & Casillas-Martín, S. (2024). Impact of gamification on motivation and academic performance: A systematic review. Education Sciences, 14(6), 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogiannakis, M., Papadakis, S., & Zourmpakis, A.-I. (2021). Gamification in science education. A systematic review of the literature. Education Sciences, 11(1), 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, S., Quadrado, J. C., Chiluiza, K., Jaya-Montalvo, M., Rodríguez-Zurita, D., & Carrión-Mero, P. (2025). Faculty development in stem education: Challenges and opportunities in Latin America and the Caribbean in the post-pandemic period. In EDULEARN25 proceedings, 7335–7344. 17th international conference on education and new learning technologies. Iated Digital Library. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, N., López-Serrano, A., & Burgos, D. (2023). Serious games and soft skills in higher education: A case study of the design of compete! Electronics, 12(6), 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKevitt, C., Porcenaluk, S., & Connolly, C. (2025). Effective professional development and gamification in the mathematics classroom: Effects on mathematical resilience. Education Sciences, 15(7), 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscoso-Barrera, W., & Wang, H. (2024, June 23–26). An iterative design approach in biomedical engineering student group projects. The 2024 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition Proceedings, ASEE Conferences, Portland, OR, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Nuñez, D., Vargas, V., Vásquez, F., Andrade, W., & Espiniza, F. (2023). Educación STEM: Una revisión de enfoques interdisciplinarios y mejores prácticas para fomentar habilidades en ciencia, tecnología, ingeniería y matemáticas. ResearchGate, 7(2), 2023–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parque de las Ciencias. (2020). Brazo robótico. ESERO Spain. Available online: https://mooncampchallenge.org/es/robotic-arm-become-a-space-engineer-for-a-day/?fbclid=IwAR0dAGjU60UvreckMHTKMDLLv8FzaUNKxm8YTHoTzo6jgMx_8_ojJP_jXgM (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Pliushch, V., & Sorokun, S. (2022). Innovative pedagogical technologies in education system. Revista Tempos e Espaços Em Educação, 15(34), e16960. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/journal/5702/570272314022/html/ (accessed on 1 February 2023). [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, A., & Qureshi, N. (2021). Challenges and issues of STEM education. ResearchGate, 1(2), 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, K., Chiliquinga, R., Luje, david, & Pucha, O. (2025). Desarrollo de habilidades del siglo XXI a través de la educación STEM developing 21st Century skills through STEM education. ResearchGate, 7(2), 316–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, G. d. C., & Gras, M. (2023, July). Educación STEM y su aplicación: Una estrategia inclusiva, sostenible y universal para preescolar y primaria. Movimiento STEM. ISBN 978-607-24-4980-0. Available online: https://educacion.stem.siemens-stiftung.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Educacion-STEM-y-su-aplicacion.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Schwab, K. (2020). La cuarta revolución industrial. Futuro Hoy, 1, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seliro, N., & Nizarudin, M. (2025). Gamification: An effective strategy for developing soft skills and STEM in students. QALAMUNA: Jurnal Pendidikan, Sosial, Dan Agama, 14(1), 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F., Fernández, J., & Carrillo, J. (2019). Propuesta didáctica. Realidad Virtual y STEM (REVI-STEM). [Google Scholar]

- Stehle, S. M., & Peters-Burton, E. E. (2019). Developing student 21st Century skills in selected exemplary inclusive STEM high schools. International Journal of STEM Education, 6(1), 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubaidillah, M., Marwoto, P., Wiyanto, W., & Subali, B. (2023). Problem solving and decision-making skills for ESD: A bibliometric analysis. ResearchGate, 11, 401–4015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhaobing, Z., Yao, J., Gu, H., & Przybylski, R. (2018). A meta-analysis on the effects of STEM education on students’ abilities. Science Insights Education Frontiers, 1(1), 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).